- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.2: Concepts, Constructs, and Variables

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 26212

- Anol Bhattacherjee

- University of South Florida via Global Text Project

We discussed in Chapter 1 that although research can be exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory, most scientific research tend to be of the explanatory type in that they search for potential explanations of observed natural or social phenomena. Explanations require development of concepts or generalizable properties or characteristics associated with objects, events, or people. While objects such as a person, a firm, or a car are not concepts, their specific characteristics or behavior such as a person’s attitude toward immigrants, a firm’s capacity for innovation, and a car’s weight can be viewed as concepts.

Knowingly or unknowingly, we use different kinds of concepts in our everyday conversations. Some of these concepts have been developed over time through our shared language. Sometimes, we borrow concepts from other disciplines or languages to explain a phenomenon of interest. For instance, the idea of gravitation borrowed from physics can be used in business to describe why people tend to “gravitate” to their preferred shopping destinations. Likewise, the concept of distance can be used to explain the degree of social separation between two otherwise collocated individuals. Sometimes, we create our own concepts to describe a unique characteristic not described in prior research. For instance, technostress is a new concept referring to the mental stress one may face when asked to learn a new technology.

Concepts may also have progressive levels of abstraction. Some concepts such as a person’s weight are precise and objective, while other concepts such as a person’s personality may be more abstract and difficult to visualize. A construct is an abstract concept that is specifically chosen (or “created”) to explain a given phenomenon. A construct may be a simple concept, such as a person’s weight , or a combination of a set of related concepts such as a person’s communication skill , which may consist of several underlying concepts such as the person’s vocabulary , syntax , and spelling . The former instance (weight) is a unidimensional construct , while the latter (communication skill) is a multi-dimensional construct (i.e., it consists of multiple underlying concepts). The distinction between constructs and concepts are clearer in multi-dimensional constructs, where the higher order abstraction is called a construct and the lower order abstractions are called concepts. However, this distinction tends to blur in the case of unidimensional constructs.

Constructs used for scientific research must have precise and clear definitions that others can use to understand exactly what it means and what it does not mean. For instance, a seemingly simple construct such as income may refer to monthly or annual income, before-tax or after-tax income, and personal or family income, and is therefore neither precise nor clear. There are two types of definitions: dictionary definitions and operational definitions. In the more familiar dictionary definition, a construct is often defined in terms of a synonym. For instance, attitude may be defined as a disposition, a feeling, or an affect, and affect in turn is defined as an attitude. Such definitions of a circular nature are not particularly useful in scientific research for elaborating the meaning and content of that construct. Scientific research requires operational definitions that define constructs in terms of how they will be empirically measured. For instance, the operational definition of a construct such as temperature must specify whether we plan to measure temperature in Celsius, Fahrenheit, or Kelvin scale. A construct such as income should be defined in terms of whether we are interested in monthly or annual income, before-tax or after-tax income, and personal or family income. One can imagine that constructs such as learning , personality , and intelligence can be quite hard to define operationally.

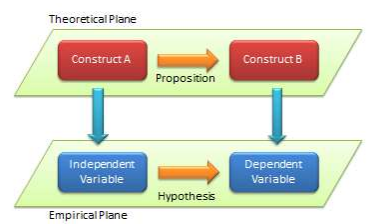

A term frequently associated with, and sometimes used interchangeably with, a construct is a variable. Etymologically speaking, a variable is a quantity that can vary (e.g., from low to high, negative to positive, etc.), in contrast to constants that do not vary (i.e., remain constant). However, in scientific research, a variable is a measurable representation of an abstract construct. As abstract entities, constructs are not directly measurable, and hence, we look for proxy measures called variables. For instance, a person’s intelligence is often measured as his or her IQ ( intelligence quotient ) score , which is an index generated from an analytical and pattern-matching test administered to people. In this case, intelligence is a construct, and IQ score is a variable that measures the intelligence construct. Whether IQ scores truly measures one’s intelligence is anyone’s guess (though many believe that they do), and depending on whether how well it measures intelligence, the IQ score may be a good or a poor measure of the intelligence construct. As shown in Figure 2.1, scientific research proceeds along two planes: a theoretical plane and an empirical plane. Constructs are conceptualized at the theoretical (abstract) plane, while variables are operationalized and measured at the empirical (observational) plane. Thinking like a researcher implies the ability to move back and forth between these two planes.

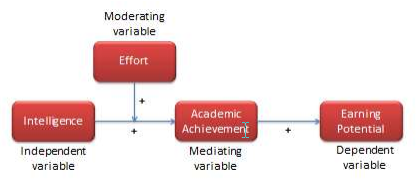

Depending on their intended use, variables may be classified as independent, dependent, moderating, mediating, or control variables. Variables that explain other variables are called independent variables , those that are explained by other variables are dependent variables , those that are explained by independent variables while also explaining dependent variables are mediating variables (or intermediate variables), and those that influence the relationship between independent and dependent variables are called moderating variables . As an example, if we state that higher intelligence causes improved learning among students, then intelligence is an independent variable and learning is a dependent variable. There may be other extraneous variables that are not pertinent to explaining a given dependent variable, but may have some impact on the dependent variable. These variables must be controlled for in a scientific study, and are therefore called control variables .

To understand the differences between these different variable types, consider the example shown in Figure 2.2. If we believe that intelligence influences (or explains) students’ academic achievement, then a measure of intelligence such as an IQ score is an independent variable, while a measure of academic success such as grade point average is a dependent variable. If we believe that the effect of intelligence on academic achievement also depends on the effort invested by the student in the learning process (i.e., between two equally intelligent students, the student who puts is more effort achieves higher academic achievement than one who puts in less effort), then effort becomes a moderating variable. Incidentally, one may also view effort as an independent variable and intelligence as a moderating variable. If academic achievement is viewed as an intermediate step to higher earning potential, then earning potential becomes the dependent variable for the independent variable academic achievement , and academic achievement becomes the mediating variable in the relationship between intelligence and earning potential. Hence, variable are defined as an independent, dependent, moderating, or mediating variable based on their nature of association with each other. The overall network of relationships between a set of related constructs is called a nomological network (see Figure 2.2). Thinking like a researcher requires not only being able to abstract constructs from observations, but also being able to mentally visualize a nomological network linking these abstract constructs.

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Causal Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Causal research: definition, examples and how to use it.

16 min read Causal research enables market researchers to predict hypothetical occurrences & outcomes while improving existing strategies. Discover how this research can decrease employee retention & increase customer success for your business.

What is causal research?

Causal research, also known as explanatory research or causal-comparative research, identifies the extent and nature of cause-and-effect relationships between two or more variables.

It’s often used by companies to determine the impact of changes in products, features, or services process on critical company metrics. Some examples:

- How does rebranding of a product influence intent to purchase?

- How would expansion to a new market segment affect projected sales?

- What would be the impact of a price increase or decrease on customer loyalty?

To maintain the accuracy of causal research, ‘confounding variables’ or influences — e.g. those that could distort the results — are controlled. This is done either by keeping them constant in the creation of data, or by using statistical methods. These variables are identified before the start of the research experiment.

As well as the above, research teams will outline several other variables and principles in causal research:

- Independent variables

The variables that may cause direct changes in another variable. For example, the effect of truancy on a student’s grade point average. The independent variable is therefore class attendance.

- Control variables

These are the components that remain unchanged during the experiment so researchers can better understand what conditions create a cause-and-effect relationship.

This describes the cause-and-effect relationship. When researchers find causation (or the cause), they’ve conducted all the processes necessary to prove it exists.

- Correlation

Any relationship between two variables in the experiment. It’s important to note that correlation doesn’t automatically mean causation. Researchers will typically establish correlation before proving cause-and-effect.

- Experimental design

Researchers use experimental design to define the parameters of the experiment — e.g. categorizing participants into different groups.

- Dependent variables

These are measurable variables that may change or are influenced by the independent variable. For example, in an experiment about whether or not terrain influences running speed, your dependent variable is the terrain.

Why is causal research useful?

It’s useful because it enables market researchers to predict hypothetical occurrences and outcomes while improving existing strategies. This allows businesses to create plans that benefit the company. It’s also a great research method because researchers can immediately see how variables affect each other and under what circumstances.

Also, once the first experiment has been completed, researchers can use the learnings from the analysis to repeat the experiment or apply the findings to other scenarios. Because of this, it’s widely used to help understand the impact of changes in internal or commercial strategy to the business bottom line.

Some examples include:

- Understanding how overall training levels are improved by introducing new courses

- Examining which variations in wording make potential customers more interested in buying a product

- Testing a market’s response to a brand-new line of products and/or services

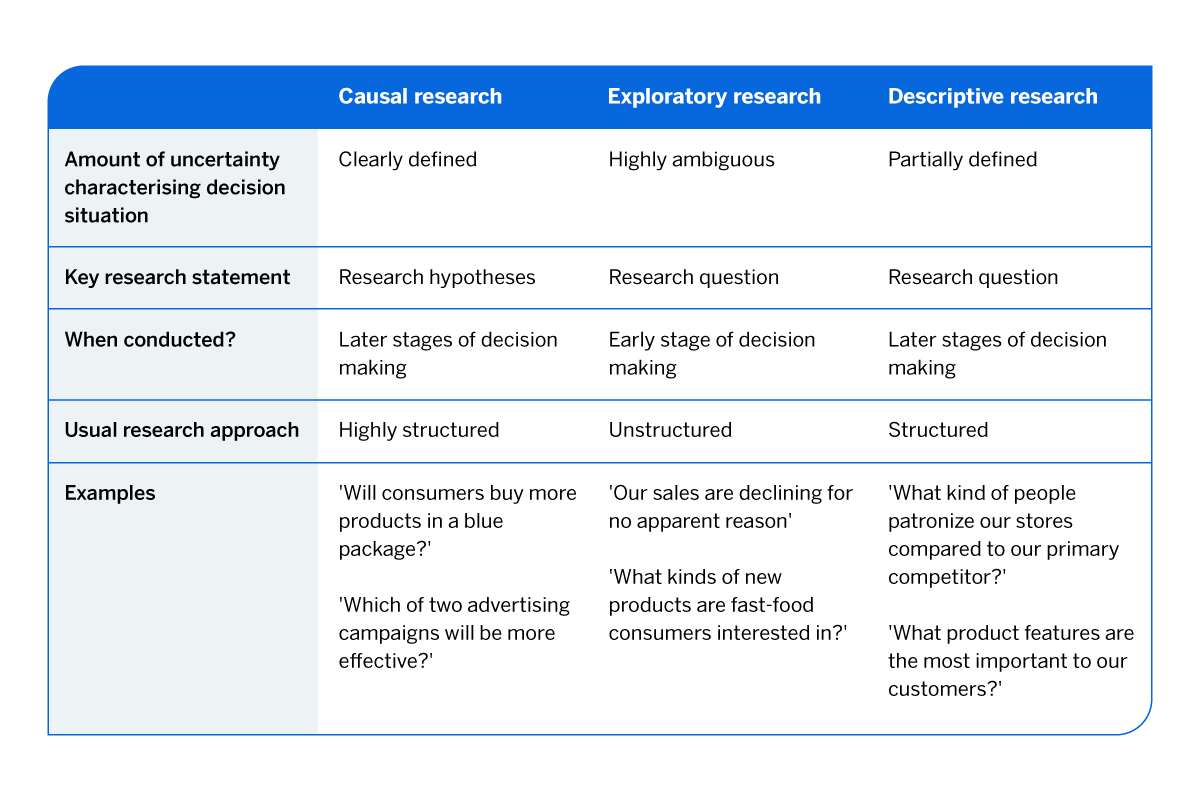

So, how does causal research compare and differ from other research types?

Well, there are a few research types that are used to find answers to some of the examples above:

1. Exploratory research

As its name suggests, exploratory research involves assessing a situation (or situations) where the problem isn’t clear. Through this approach, researchers can test different avenues and ideas to establish facts and gain a better understanding.

Researchers can also use it to first navigate a topic and identify which variables are important. Because no area is off-limits, the research is flexible and adapts to the investigations as it progresses.

Finally, this approach is unstructured and often involves gathering qualitative data, giving the researcher freedom to progress the research according to their thoughts and assessment. However, this may make results susceptible to researcher bias and may limit the extent to which a topic is explored.

2. Descriptive research

Descriptive research is all about describing the characteristics of the population, phenomenon or scenario studied. It focuses more on the “what” of the research subject than the “why”.

For example, a clothing brand wants to understand the fashion purchasing trends amongst buyers in California — so they conduct a demographic survey of the region, gather population data and then run descriptive research. The study will help them to uncover purchasing patterns amongst fashion buyers in California, but not necessarily why those patterns exist.

As the research happens in a natural setting, variables can cross-contaminate other variables, making it harder to isolate cause and effect relationships. Therefore, further research will be required if more causal information is needed.

Get started on your market research journey with CoreXM

How is causal research different from the other two methods above?

Well, causal research looks at what variables are involved in a problem and ‘why’ they act a certain way. As the experiment takes place in a controlled setting (thanks to controlled variables) it’s easier to identify cause-and-effect amongst variables.

Furthermore, researchers can carry out causal research at any stage in the process, though it’s usually carried out in the later stages once more is known about a particular topic or situation.

Finally, compared to the other two methods, causal research is more structured, and researchers can combine it with exploratory and descriptive research to assist with research goals.

Summary of three research types

What are the advantages of causal research?

- Improve experiences

By understanding which variables have positive impacts on target variables (like sales revenue or customer loyalty), businesses can improve their processes, return on investment, and the experiences they offer customers and employees.

- Help companies improve internally

By conducting causal research, management can make informed decisions about improving their employee experience and internal operations. For example, understanding which variables led to an increase in staff turnover.

- Repeat experiments to enhance reliability and accuracy of results

When variables are identified, researchers can replicate cause-and-effect with ease, providing them with reliable data and results to draw insights from.

- Test out new theories or ideas

If causal research is able to pinpoint the exact outcome of mixing together different variables, research teams have the ability to test out ideas in the same way to create viable proof of concepts.

- Fix issues quickly

Once an undesirable effect’s cause is identified, researchers and management can take action to reduce the impact of it or remove it entirely, resulting in better outcomes.

What are the disadvantages of causal research?

- Provides information to competitors

If you plan to publish your research, it provides information about your plans to your competitors. For example, they might use your research outcomes to identify what you are up to and enter the market before you.

- Difficult to administer

Causal research is often difficult to administer because it’s not possible to control the effects of extraneous variables.

- Time and money constraints

Budgetary and time constraints can make this type of research expensive to conduct and repeat. Also, if an initial attempt doesn’t provide a cause and effect relationship, the ROI is wasted and could impact the appetite for future repeat experiments.

- Requires additional research to ensure validity

You can’t rely on just the outcomes of causal research as it’s inaccurate. It’s best to conduct other types of research alongside it to confirm its output.

- Trouble establishing cause and effect

Researchers might identify that two variables are connected, but struggle to determine which is the cause and which variable is the effect.

- Risk of contamination

There’s always the risk that people outside your market or area of study could affect the results of your research. For example, if you’re conducting a retail store study, shoppers outside your ‘test parameters’ shop at your store and skew the results.

How can you use causal research effectively?

To better highlight how you can use causal research across functions or markets, here are a few examples:

Market and advertising research

A company might want to know if their new advertising campaign or marketing campaign is having a positive impact. So, their research team can carry out a causal research project to see which variables cause a positive or negative effect on the campaign.

For example, a cold-weather apparel company in a winter ski-resort town may see an increase in sales generated after a targeted campaign to skiers. To see if one caused the other, the research team could set up a duplicate experiment to see if the same campaign would generate sales from non-skiers. If the results reduce or change, then it’s likely that the campaign had a direct effect on skiers to encourage them to purchase products.

Improving customer experiences and loyalty levels

Customers enjoy shopping with brands that align with their own values, and they’re more likely to buy and present the brand positively to other potential shoppers as a result. So, it’s in your best interest to deliver great experiences and retain your customers.

For example, the Harvard Business Review found that an increase in customer retention rates by 5% increased profits by 25% to 95%. But let’s say you want to increase your own, how can you identify which variables contribute to it?Using causal research, you can test hypotheses about which processes, strategies or changes influence customer retention. For example, is it the streamlined checkout? What about the personalized product suggestions? Or maybe it was a new solution that solved their problem? Causal research will help you find out.

Discover how to use analytics to improve customer retention.

Improving problematic employee turnover rates

If your company has a high attrition rate, causal research can help you narrow down the variables or reasons which have the greatest impact on people leaving. This allows you to prioritize your efforts on tackling the issues in the right order, for the best positive outcomes.

For example, through causal research, you might find that employee dissatisfaction due to a lack of communication and transparency from upper management leads to poor morale, which in turn influences employee retention.

To rectify the problem, you could implement a routine feedback loop or session that enables your people to talk to your company’s C-level executives so that they feel heard and understood.

How to conduct causal research first steps to getting started are:

1. Define the purpose of your research

What questions do you have? What do you expect to come out of your research? Think about which variables you need to test out the theory.

2. Pick a random sampling if participants are needed

Using a technology solution to support your sampling, like a database, can help you define who you want your target audience to be, and how random or representative they should be.

3. Set up the controlled experiment

Once you’ve defined which variables you’d like to measure to see if they interact, think about how best to set up the experiment. This could be in-person or in-house via interviews, or it could be done remotely using online surveys.

4. Carry out the experiment

Make sure to keep all irrelevant variables the same, and only change the causal variable (the one that causes the effect) to gather the correct data. Depending on your method, you could be collecting qualitative or quantitative data, so make sure you note your findings across each regularly.

5. Analyze your findings

Either manually or using technology, analyze your data to see if any trends, patterns or correlations emerge. By looking at the data, you’ll be able to see what changes you might need to do next time, or if there are questions that require further research.

6. Verify your findings

Your first attempt gives you the baseline figures to compare the new results to. You can then run another experiment to verify your findings.

7. Do follow-up or supplemental research

You can supplement your original findings by carrying out research that goes deeper into causes or explores the topic in more detail. One of the best ways to do this is to use a survey. See ‘Use surveys to help your experiment’.

Identifying causal relationships between variables

To verify if a causal relationship exists, you have to satisfy the following criteria:

- Nonspurious association

A clear correlation exists between one cause and the effect. In other words, no ‘third’ that relates to both (cause and effect) should exist.

- Temporal sequence

The cause occurs before the effect. For example, increased ad spend on product marketing would contribute to higher product sales.

- Concomitant variation

The variation between the two variables is systematic. For example, if a company doesn’t change its IT policies and technology stack, then changes in employee productivity were not caused by IT policies or technology.

How surveys help your causal research experiments?

There are some surveys that are perfect for assisting researchers with understanding cause and effect. These include:

- Employee Satisfaction Survey – An introductory employee satisfaction survey that provides you with an overview of your current employee experience.

- Manager Feedback Survey – An introductory manager feedback survey geared toward improving your skills as a leader with valuable feedback from your team.

- Net Promoter Score (NPS) Survey – Measure customer loyalty and understand how your customers feel about your product or service using one of the world’s best-recognized metrics.

- Employee Engagement Survey – An entry-level employee engagement survey that provides you with an overview of your current employee experience.

- Customer Satisfaction Survey – Evaluate how satisfied your customers are with your company, including the products and services you provide and how they are treated when they buy from you.

- Employee Exit Interview Survey – Understand why your employees are leaving and how they’ll speak about your company once they’re gone.

- Product Research Survey – Evaluate your consumers’ reaction to a new product or product feature across every stage of the product development journey.

- Brand Awareness Survey – Track the level of brand awareness in your target market, including current and potential future customers.

- Online Purchase Feedback Survey – Find out how well your online shopping experience performs against customer needs and expectations.

That covers the fundamentals of causal research and should give you a foundation for ongoing studies to assess opportunities, problems, and risks across your market, product, customer, and employee segments.

If you want to transform your research, empower your teams and get insights on tap to get ahead of the competition, maybe it’s time to leverage Qualtrics CoreXM.

Qualtrics CoreXM provides a single platform for data collection and analysis across every part of your business — from customer feedback to product concept testing. What’s more, you can integrate it with your existing tools and services thanks to a flexible API.

Qualtrics CoreXM offers you as much or as little power and complexity as you need, so whether you’re running simple surveys or more advanced forms of research, it can deliver every time.

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Research paper structure & sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Research Problem – Explanation & Examples

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

A research problem sets the course of investigation in any research process . It can probe practical issues with the aim of suggesting modifications, or scrutinize theoretical quandaries to augment the current understanding in a discipline.

In this article, we delve into the crucial role of a research problem in the research process, as well as offer guidance on how to properly articulate it to steer your research endeavors.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Research Problem – In a Nutshell

- 2 Definition: Research problem

- 3 Why is the research problem important?

- 4 Step 1: Finding a general research problem area

- 5 Step 2: Narrowing down the research problem

- 6 Example of a research problem

Research Problem – In a Nutshell

- A research problem is an issue that raises concern about a particular topic.

- Researchers formulate research problems by examining other literature on the topic and assessing the significance and relevance of the problem.

- Creating a research problem involves an overview of a broad problem area and then narrowing it down to the specifics by creating a framework for the topic.

- General problem areas used in formulating research problems include workplace and theoretical research.

Definition: Research problem

A research problem is a specific challenge or knowledge gap that sets the foundation for research. It is the primary statement about a topic in a field of study, and the findings from a research undertaking provide solutions to the research problem.

The research problem is the defining statement that informs the sources and methodologies to be applied to find and recommend proposals for the area of contention.

Why is the research problem important?

Research should adopt a precise approach for analysis to be relevant and applicable in a real-world context. Researchers can pick any area of study, and in most cases, the topic in question will have a broad scope; a well-formulated problem forms the basis of a strong research paper which illustrates a clear focus.

Writing a research problem is the first step in planning for a research paper, and a well-structured problem prevents a runaway project that lacks a clear direction.

Step 1: Finding a general research problem area

Your primary goal should be to find gaps and meaningful ways your research project offers a solution to a problem or broadens the knowledge bank in the field.

A good approach is to read and hold discussions about the topic , identify areas with insufficient information, highlight areas of contention and form more in-depth conclusions in under-researched areas.

Workplace research

You can carry out workplace research using a practical approach . This aims to identify a problem by analyzing reports, engaging with people in the organization or field of interest, and examining previous research. Some pointers include:

- Efficiency and performance-related issues within an organization.

- Areas or processes that can be improved in the organization.

- Matters of concern among professionals in the field of study.

- Challenges faced by identifiable groups in society.

- Crime in a particular region has been decreasing compared to the rest of the country.

- Stores in one location of a chain have been reporting lower sales in contrast with others in other parts of the country.

- One subsidiary of a company is experiencing high staff turnover, affecting the group’s bottom line.

In theoretical research , researchers aim to offer new insights which contribute to the larger knowledge body in the field rather than proposing change. You can formulate a problem by studying recent studies, debates, and theories to identify gaps. Identifying a research problem in theoretical research may examine the following:

- A context or phenomenon that has not been extensively studied.

- A contrast between two or more thought patterns.

- A position that is not clearly understood.

- A bothersome scenario or question that remains unsolved.

Theoretical problems don’t focus on solving a practical problem but have practical implications in their field. Many theoretical frameworks offer a guide to other practical and applied research scenarios.

- The relationship between genetics and mental issues in adulthood is not clearly understood.

- The effects of racial differences in long-term relationships are yet to be investigated in the modern dating scene.

- Social scientists disagree on the impact of neocolonialism on the socio-economic conditions of black people.

Step 2: Narrowing down the research problem

After identifying a general problem area, you need to zero in on the specific aspect you want to analyze further in the context of your research.

The problem can be narrowed down using the following criteria to create a relevant problem whose solutions adequately answer the research questions . Some questions you can ask to understand the contextual framework of the research problem include:

Significance

Evaluating the significance of a research problem is a necessary step for identifying issues that contribute to the solution of an issue. There are several ways of determining the significance of a research problem. The following questions can help you to evaluate the significance and relevance of a proposed research problem:

- Which area, group or time do you plan to situate your study?

- What attributes will you examine?

- What is the repercussion of not solving the problem?

- Who stands to benefit if the problem is resolved?

Example of a research problem

A fashion retail chain is attempting to increase the number of visitors to its stores, but the management is unaware of the measures to achieve this.

To improve its sales and compete with other chains, the chain requires research into ways of increasing traffic in its stores.

By narrowing down the research problem, you can create the problem statement , hypothesis , and relevant research questions .

What is an example of a research problem?

There has been an upward trend in the immigration of professionals from other countries to the UK. Research is needed to determine the likely causes and effects.

How do you formulate a research problem?

Begin by examining available sources and previous research on your topic of interest. You can narrow down the scope from the literature or observable phenomenon and focus on under-researched areas.

How can you determine the significance of a research problem?

Investigate the specific aspects you would like to investigate. Furthermore, you can determine the consequences of the problem remaining unresolved and the biggest beneficiaries if a solution is found.

What is the context in a research problem?

Context refers to the nature of the problem. It entails studying existing work on the issue, who is affected by it, and the proposed solutions.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Topic Guide - Developing Your Research Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

Definitions

Identifying dependent and indepent variables, structure and writing style.

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- APA 7th Edition

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- 10. Proofreading Your Paper

- Writing Concisely

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Study

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Bibliography

Dependent Variable The variable that depends on other factors that are measured. These variables are expected to change as a result of an experimental manipulation of the independent variable or variables. It is the presumed effect.

Independent Variable The variable that is stable and unaffected by the other variables you are trying to measure. It refers to the condition of an experiment that is systematically manipulated by the investigator. It is the presumed cause.

Cramer, Duncan and Dennis Howitt. The SAGE Dictionary of Statistics . London: SAGE, 2004; Penslar, Robin Levin and Joan P. Porter. Institutional Review Board Guidebook: Introduction . Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2010; "What are Dependent and Independent Variables?" Graphic Tutorial .

Don't feel bad if you are confused about what is the dependent variable and what is the independent variable in social and behavioral sciences research . However, it's important that you learn the difference because framing a study using these variables is a common approach to organizing the elements of a social sciences research study in order to discover relevant and meaningful results. Specifically, it is important for these two reasons:

- You need to understand and be able to evaluate their application in other people's research.

- You need to apply them correctly in your own research.

A variable in research simply refers to a person, place, thing, or phenomenon that you are trying to measure in some way. The best way to understand the difference between a dependent and independent variable is that the meaning of each is implied by what the words tell us about the variable you are using. You can do this with a simple exercise from the website, Graphic Tutorial. Take the sentence, "The [independent variable] causes a change in [dependent variable] and it is not possible that [dependent variable] could cause a change in [independent variable]." Insert the names of variables you are using in the sentence in the way that makes the most sense. This will help you identify each type of variable. If you're still not sure, consult with your professor before you begin to write.

Fan, Shihe. "Independent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design. Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 592-594; "What are Dependent and Independent Variables?" Graphic Tutorial ; Salkind, Neil J. "Dependent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 348-349;

The process of examining a research problem in the social and behavioral sciences is often framed around methods of analysis that compare, contrast, correlate, average, or integrate relationships between or among variables . Techniques include associations, sampling, random selection, and blind selection. Designation of the dependent and independent variable involves unpacking the research problem in a way that identifies a general cause and effect and classifying these variables as either independent or dependent.

The variables should be outlined in the introduction of your paper and explained in more detail in the methods section . There are no rules about the structure and style for writing about independent or dependent variables but, as with any academic writing, clarity and being succinct is most important.

After you have described the research problem and its significance in relation to prior research, explain why you have chosen to examine the problem using a method of analysis that investigates the relationships between or among independent and dependent variables . State what it is about the research problem that lends itself to this type of analysis. For example, if you are investigating the relationship between corporate environmental sustainability efforts [the independent variable] and dependent variables associated with measuring employee satisfaction at work using a survey instrument, you would first identify each variable and then provide background information about the variables. What is meant by "environmental sustainability"? Are you looking at a particular company [e.g., General Motors] or are you investigating an industry [e.g., the meat packing industry]? Why is employee satisfaction in the workplace important? How does a company make their employees aware of sustainability efforts and why would a company even care that its employees know about these efforts?

Identify each variable for the reader and define each . In the introduction, this information can be presented in a paragraph or two when you describe how you are going to study the research problem. In the methods section, you build on the literature review of prior studies about the research problem to describe in detail background about each variable, breaking each down for measurement and analysis. For example, what activities do you examine that reflect a company's commitment to environmental sustainability? Levels of employee satisfaction can be measured by a survey that asks about things like volunteerism or a desire to stay at the company for a long time.

The structure and writing style of describing the variables and their application to analyzing the research problem should be stated and unpacked in such a way that the reader obtains a clear understanding of the relationships between the variables and why they are important. This is also important so that the study can be replicated in the future using the same variables but applied in a different way.

Fan, Shihe. "Independent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design. Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 592-594; "What are Dependent and Independent Variables?" Graphic Tutorial ; “ Case Example for Independent and Dependent Variables .” ORI Curriculum Examples. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Research Integrity; Salkind, Neil J. "Dependent Variable." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2010), pp. 348-349; “ Independent Variables and Dependent Variables .” Karl L. Wuensch, Department of Psychology, East Carolina University [posted email exchange]; “ Variables .” Elements of Research. Dr. Camille Nebeker, San Diego State University.

- << Previous: Flaws to Avoid

- Next: Glossary of Research Terms >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2022 8:49 AM

- URL: https://leeuniversity.libguides.com/research_study_guide

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- The Research Problem/Question

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Research Effectively

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Is it Peer-Reviewed?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism [linked guide]

- Annotated Bibliography

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered its significance and its implications applied to obtaining new knowledge or understanding.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking . The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem. Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Structure and Writing Style

Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society, your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people].Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and help define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state that the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question . The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement . The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements . University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation . Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question . [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009.

- << Previous: Broadening a Topic Idea

- Next: Preparing to Write >>

- Last Updated: Sep 8, 2023 12:19 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.txstate.edu/socialscienceresearch

Different types of research problems and their examples