Gender and politics research in Europe: towards a consolidation of a flourishing political science subfield?

- Special Issue

- Published: 21 January 2021

- Volume 20 , pages 105–122, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Petra Ahrens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1867-4519 1 ,

- Silvia Erzeel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3931-6953 2 ,

- Elizabeth Evans ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3237-8951 3 ,

- Johanna Kantola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6214-1640 1 ,

- Roman Kuhar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4294-7529 4 &

- Emanuela Lombardo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7644-6891 5

4788 Accesses

8 Citations

27 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Over the past twenty years, the field of “gender and politics” has flourished in European political science. An example of this is the growing number of “gender and politics” scholars and the increased attention paid to gender perspectives in the study of the political. Against this backdrop, we take stock of how the “gender and politics” field has developed over the years. We argue that the field has now entered a stage of “consolidation”, which is reflected in the growth, diversification and professionalization of the subfield, as well as in the increased disciplinary recognition from major gatekeepers in political science. But while consolidation comes with specific opportunities, it also presents some key challenges. We identify five such challenges: (1) the potential fragmentation of the field; (2) persisting hierarchies in knowledge production; (3) the continued marginalization of feminist political analysis in “mainstream” political science; (4) the changing link between academia and society; and (5) growing opposition to gender studies in parts of Europe and beyond. We argue that both the “gender and politics” field and political science in general should address these challenges in order to become a truly inclusive discipline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Gender and sexuality research in the age of populism: lessons for political science

Isabelle Engeli

political science as a gendered discipline in finland

johanna kantola

Gender Studies in the Czech Republic: Institutionalisation Meets Neo-liberalism Contingent on Geopolitics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gender structures our understanding of all political phenomena and shapes such diverse issues as Brexit, COVID-19 or democratic backsliding (to name but a few). Indeed, the subfield of “gender and politics” has flourished in European political science over the last twenty years: There has been the establishment of a conference and a new journal; gender, sexuality and intersectionality in the study of the political (and indeed what counts as the political) is increasingly recognized by the broader political science community (Mügge et al. 2016 ); and a growing number of scholars have revealed and contested biases against gender and politics research in the discipline and its institutions.

We take stock of how the “gender and politics” field has developed over the past twenty years, taking 2001 as a starting point because it serves the purpose of this anniversary issue of European Political Science . The development of the “gender and politics”-subfield, however, has a longer history, and can be traced back to the late 1970s and 1980s (Costa and Sawer 2018 ; Lovenduski 2015 ). Given that “Gender and Politics” can no longer be considered a “new” or “emerging” field of study (see Dahlerup 2010 for a comparison), we ask in this article whether the subfield has now entered a new stage of “consolidation” and what this means for both the field itself and the discipline of political science. In order to answer these questions, we scrutinize different indicators of consolidation. For analytical purposes, we consider consolidation as a twofold process, characterized by both internal and external developments. Internal consolidation relates to the growth and integration of gender and politics research into a specialist (sub)field and autonomous knowledge community in political science. External consolidation relates to the external recognition that gender and politics research has received from other (sub)fields and major gatekeepers in political science (such as major political science associations and journals).

For the purpose of this article, we define “gender and politics” as a subfield of political science that is primarily concerned with the study of gender, sexuality and/or intersectionality perspectives in the study of the political. We, the authors, are committed to promoting a broad understanding of gender and politics research; we recognise the matrices of oppression that shape our politics and our societies (Hill Collins 2002 ) and the importance of intersectionality (Crenshaw 1991 ; Yuval-Davis 2012 ) as a lens with which to analyse “complex gender equality” (Verloo and Walby 2012 ), comprising gender, class, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression and other categories of social inequalities. We are aware that our knowledge is situated within a political science context mostly informed by the canons of the discipline in Europe and the USA, which shapes the way we approach gender and politics research. This reminds us of the need to keep decolonizing the discipline (Medie and Kang 2018 ; Mendoza 2012 ). Footnote 1

In the following sections, we reflect upon the internal and external consolidation of European gender and politics research over the last two decades. We consider the growth and increased professionalization of the subfield, as well as the increased recognition it receives from the broader discipline of political science. Next, we discuss five key challenges that hinder the further consolidation of the field: (1) the potential fragmentation and disintegration of the field, (2) persisting hierarchies in knowledge production, (3) the continued marginalization of feminist political analysis in “mainstream” political science, (4) the changing link between academia and “society”, and (5) growing opposition to gender studies in several parts of Europe. We argue that both the “gender and politics”-field and political sciences more in general will have to take up these challenges in the future in order to “become a truly inclusive discipline”—a question the EPS editors rightfully posed in the call for papers for this anniversary issue.

The consolidation of “gender and politics”—a twofold process

Although the focus of this article is on how the “gender and politics” subfield developed over the past twenty years, what we find today builds on actions that started well before 2000 and are (slowly) materialising (Celis et al. 2013 ; Costa and Sawer 2018 ; Dahlerup 2010 ; Lovenduski 2015 for overviews). We understand the development of “gender and politics” as a twofold consolidation process resulting internally in a specialist subfield and externally in recognition by political science as a discipline.

Internal consolidation: growth, diversification and professionalization

Over the years, the gender and politics subfield evolved from a primary concern with the study of “women in politics” to the study of “gender and politics” more broadly (Lovenduski 2015 ).

This evolution marks an expansion in research foci and strategies. Earlier studies were primarily concerned with making women’s political roles and activities more visible. Research questions developed out of a concern to explore the diversity of perspectives present in political life, to highlight women’s previously overlooked contributions to it, and to give a voice to their subjective experiences as marginalized groups. Recent studies pay relatively more attention to the study of gendered political processes, institutions and interactions. The research focus has shifted towards exposing and questioning gender hierarchies and inequalities in a variety of political phenomena. As part of this shift, increasing attention is also devoted to the study of men as “gendered beings” in politics (Connell 2002 ) and the interactions between gender and other social markers such as social class, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, age and disability (Crenshaw 1991 ; Hancock 2007 ; McCall 2005 ); although these perspectives and voices are still at risk of being marginalized in the field (see below).

A defining feature of politics and gender research is its rooting in, and dialogue with, two distinct academic disciplines: political sciences and gender studies. Thus, its research is often characterized by a multi- and interdisciplinary engagement to a degree that is often usual for gender studies, but less so for “mainstream” political science (see also Costa and Sawer 2018 ). Scholars within the politics and gender field often draw from a wide range of disciplinary backgrounds such as anthropology, economics, philosophy, sociology and others. A multi- or interdisciplinary lens allows gender and politics scholars to address political phenomena from a multiplicity of angles that enhance a comprehensive understanding of political problems. It also keeps scholars alert to the risk of becoming self-referential, which could narrow analytical capacities. Moreover, gender and politics research has also been shaped by different strands of political activism such as feminist, LGBTQI+ and anti-racist movements. Thus, politics and gender research can draw upon political sciences, gender studies, and activist involvement as related but distinct sources.

In European political science, since the late 1970s, a number of national political science associations (PSAs) created women’s caucuses and/or committees on the status of women (Costa and Sawer 2018 : 246). The transnational ECPR Gender and Politics Standing Group established in 1986 (originally “Women and Politics”) brings together scholars around the world working on gender, sexuality and intersectionality in politics. The creation of this network proved to be foundational to the development, and eventual consolidation, of gender and politics as a subfield in Europe, not least because it “helped inspire activism and institutional transfer across European PSAs” (Costa and Sawer 2018 : 245). Not only did such a network provide an intellectual network for those interested in similar research agendas but it also provided an important source of solidarity amongst scholars who very often found themselves to be marginalised within their own departments, universities and national political science associations. Not surprisingly, such politics and gender groups appear often to be among the biggest and most frequented PSA sub-entities and moreover extended their scope over time to include sexuality politics and intersectionality (Costa and Sawer 2018 ). Similarly, the role of the ECPR standing group has expanded over time and it performs a number of important functions which have helped the field of gender and politics to flourish, including organising gender panels at “mainstream” political science conferences and, perhaps most importantly, the establishment of its own biennial conference, the European Conference on Politics and Gender (ECPG).

ECPG conferences have grown exponentially and mirrors the growth of the subfield, with the “sections” resembling often other political science subfields. Footnote 2 Despite the growth in numbers, and the accompanying professionalization, the importance of solidarity, empowerment and community remain core values of the conferences, particularly the desire to create non-hierarchical supportive and welcoming spaces, especially for first-time attendees. In addition to the many friendships that have been made over the years, important and valuable special issues and edited collections have been published, which grew out of conferences, workshops and panels of the standing group. As the subfield grew, so too did the number of research papers produced, and it became clear that despite the existence of a number of excellent gender and politics journals, there was a demand for more: accordingly, the European Journal of Politics and Gender was launched in 2017 (Ahrens et al. 2018 ). The journal, like the conference, is committed to intellectual plurality—in terms of theoretical, methodological and empirical approaches. Its recent inclusion in SCOPUS rankings is testament to the quality of work published.

External consolidation: disciplinary recognition

Internal consolidation proved essential to develop breadth, depth and impact, not least within our own discipline, political science. As for external consolidation, the gender and politics research received growing recognition and has—according to Kantola and Lombardo ( 2016 )—contributed to the study of politics in four crucial ways. First, it has encouraged scholars to raise new research questions and to rethink old ones. Rather than accepting the relative under-representation of women and gender issues in political life as an “empirical reality” (and therefore unworthy of scrutiny), gender and politics scholars have made them the centre point of attention, by asking what the causes and consequences of this under-representation are, and how we can assess the normative implications thereof.

Second, gender and politics scholarship has introduced a variety of analytical approaches to the study of the political. There is a strong belief that the analysis of gender cannot simply be added to existing frameworks, concepts, theories and methods, but that the latter also need to be refined and rethought. The concepts of “gender” and “intersectionality” have helped scholars to rethink the analysis of power hierarchies (Connell 2002 ; Hancock 2007 ; Hill Collins 2002 ). Standpoint epistemologies have questioned too strong claims on “strong objectivity” made in some domains of political science and have instead emphasized the role of “situated knowledge” (Harding 2004 : 81, 127).

Third, the subfield of gender and politics has also contributed to a new understanding of “the political”. Although many introductory textbooks on political science would show that “the political” has been defined in many ways by political scientists—ranging from the study of government and public life to the distribution of power—gender and politics scholars have specifically contributed to this discussion by drawing attention to the fact that “the personal is also political”. Hence, they have broadened the study of “the political” to include the study of the politics of everyday life (Phillips 1998 ).

Fourth, gender and politics scholars have, perhaps more than other subfields, paid attention to the connection between theory and praxis. For many gender and politics scholars, their academic work is connected to, even rooted in, a form of feminist commitment, either inside or outside academia. Inside academia, they question processes of knowledge production and engage in “critical scholarship with an explicitly normative dimension” (Celis et al. 2013 : 9), also opening doors for other marginalized issues, such as LGBTIQ+ studies. Outside academia, feminist scholars regularly connect with women’s movements and women’s policy agencies to ensure the societal relevance and embeddedness of their academic work.

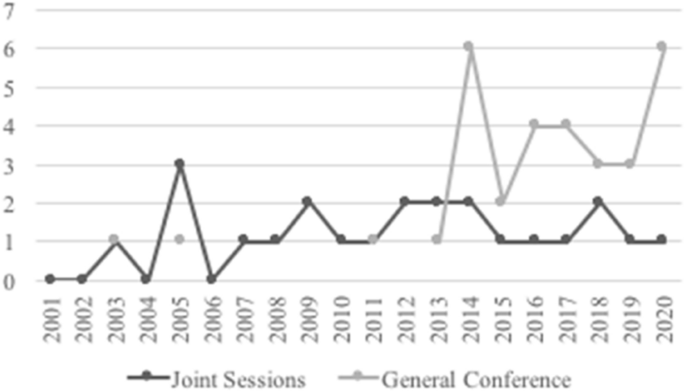

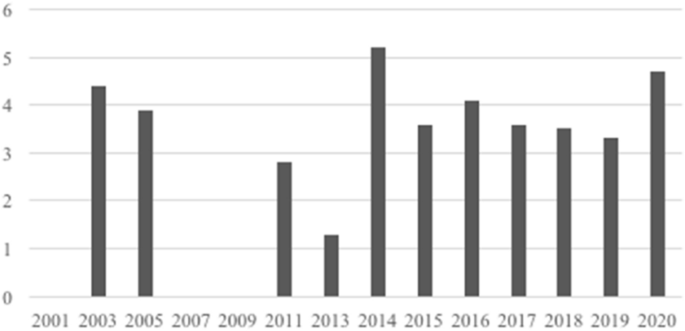

Gender and politics is also increasingly mainstreamed in Europe’s major political science conferences, associations and top-ranked journals. Since the turn of the Century, gender and politics sections and workshops have become a fixture at the ECPR’s Joint Sessions of Workshops and General Conference (see Fig. 1 ). The Joint Sessions, which are organized annually and accommodate usually between 25 and 30 workshops, have continuously hosted one or two “gender and politics” workshops since 2007. At the General Conference, Europe’s largest gathering of political scientists, sections devoted to gender and politics are also a regular feature. Since the General Conference became an annual event in 2014, the yearly academic programmes have included between two and six sections with a topical focus on gender, sexuality or intersectionality perspectives, each accommodating between three to eight panels. A quick calculation based on the information available on the ECPR website indicates that on average 4% of the total number of panels organized at the General Conference include gender, sexuality or intersectionality as a primary focus (Fig. 2 ). In recent years, gender and politics scholarship also features among the conference highlights, with several roundtables devoted to the topic in the period 2016–2020.

Note: The ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops take place annually. The ECPR General Conference takes place annually since 2014, and bi-annually in 2001–2013. Coding was based on information available on ECPR website. Coding for Joint Sessions based on workshop title and abstract for 2010–2020 and title only for 2001–2009. Coding for General Conference based on section title and keywords for 2014–2020 and title only for 2001–2013. No data available for General Conference 2001, 2007 and 2009.

Absolute number of workshops and sections with focus on gender, sexuality and intersectionality perspectives at major ECPR conferences (2001–2020) .

Note: The ECPR General Conference takes place annually since 2014, and bi-annually in 2001–2013. Coding was based on information available on ECPR website: section titles and keywords for 2014–2020 and titles only for 2001–2013. No data available for General Conference 2001, 2007 and 2009.

Percentage of panels with focus on gender, sexuality and intersectionality at ECPR General Conference (2001–2020).

By contrast, it is interesting to note that the field has not become more mainstreamed in European political science conferences over the years. Figures 1 and 2 do not reveal a significant increase in the percentage of workshops, sections and panels over time, but rather a steady presence. Moreover, most workshops, sections and panels organized at the ECPR conferences adopt a focus on “gender” and “women”. “Sexuality” and “intersectionality” perspectives remain less evident.

Turning to the integration in political science journals, we consider the percentage of articles with a primary focus on gender, sexuality and intersectionality views in ECPR’s five major journals in Table 1 . Each of these journals has a broad issue focus and welcomes contributions from a variety of subfields. Overall, the percentage of articles on gender and politics is not high—10% at best, but more often (much) lower; yet, some journals (e.g. EPS in 2001–2005 and 2016–2020) have increased the number of gender-related articles by publishing special issues or thematic sections on the topic. In the absence of a comparative yardstick, it is difficult to assess the level of gender mainstreaming in absolute terms. More important, therefore, is an assessment of over-time evolutions. In line with the findings for the conferences, there is also no clear upward trend in the number of publications on gender-related topics over time across the different journals (with the exception of EJPR). Rather, the overall picture that emerges is one of over-time fluctuations and stagnation. A combination of factors might account for these patterns, including author considerations regarding journal “fit” and success rates (Closa et al. 2020 ), the composition of editorial boards and the gendered consequences thereof (Deschouwer 2020 ), the gendered nature of the review and publication processes (Teele and Thelen 2017 ; Stockemer et al. 2020 ; Grossman 2020 ), and the growing number and impact of more domain-specific journals.

Gender and politics has also became more institutionalised within political science curricula, through both elective courses and integration within existing programs (see European Political Science Special Issue 2016 for an overview). More prizes and awards have been named after women alongside the recognition of the contribution of gender and politics scholars to political sciences, while the number of women recipients increased (to some extent), despite a persistent “Matilda effect” (Costa and Sawer 2018 ). Several PSAs have formally committed to monitoring gender equality in their organization, for instance, IPSA’s 2009 Gender and Diversity Monitoring Report or ECPR with its annual Gender Study (since 2017) and its first Gender Equality Plan (2018). Finally, mainstreaming gender and promoting gender equality and diversity has become an unavoidable (although not preclusive) criterion for grant applications to several funding agencies, not least the European Union research frameworks. Yet, despite these promising points, the picture across Europe is much more ambivalent as the future key challenges in the next section show.

Future key challenges

While consolidation is a critical moment in the development of any field, it comes with specific opportunities and also presents some key challenges. As the previous sections discussed, the consolidation story is more nuanced—there is no “increasing” mainstreaming of gender. It is rather a story of fluctuation and perhaps even stagnation, at a rather low level, if one looks at the number of sections, panels and articles on gender in mainstream conferences and journals.

We have identified five key challenges that correspond to the processes of internal and external consolidation. Internal consolidation can be challenged by (1) potential fragmentation and disintegration and (2) persisting hierarchies in knowledge production. External consolidation, in turn, can be contested by (3) continued marginalization of feminist political analysis in “mainstream” political science, (4) the changing link between academia and “society”, and (5) growing opposition to gender studies in several parts of Europe and beyond.

Potential fragmentation and disintegration

Growth—both in terms of depth and breadth—also introduces the challenge of “keeping the crowd together” while forging strong networks beyond subfields and often also other disciplines. Similar to the experience of political science as a discipline more broadly, a growing field often goes hand in hand with the development of more specialist niches, self-contained “knowledge communities”, and separate “reward systems” (Costa and Sawer 2018 : 267; Jenkins 2018 ; Vickers 2015 : 20). While such increased levels of specialisation have important benefits, including the development of particular knowledge and increased diversification, it also has some drawbacks. Specialization might result in disintegration and fragmentation. When different subfields (“gender and political representation”, “gender and European Union politics”, “gender and social movements”, …) become separate “knowledge communities” operating as “self-contained silos made up of self-referential networks” (Vickers 2015 : 20), the focus might shift from exchange between communities to exchange within communities. Not only might such a development limit the transfer of knowledge and innovation from one silo to another, it might also lead to the creation of “echo-chambers of disconnected knowledge” (Christensen and Ball 2019 : 19). This is obviously at odds with the initial multi- or interdisciplinary foundations of gender and politics—a field that has prided itself in the fact that it values cross-boundary exchange.

Confronting hierarchies in knowledge production

For gender and politics scholars, the social locatedness of the researcher and the conditions under which research is produced are crucial for thinking through how to confront persistent hierarchies in the knowledge production process (Hill Collins 2002 ; Harding 2004 ). Feminist and LGBTIQ+ scholars have challenged the exclusion of women and sexual minorities and the marginalisation of gender and sexuality as legitimate frames of analysis within political science, thereby emphasising the importance of representation and diversity within the discipline. As such, it is vital that we acknowledge, confront and create strategies to resist the hegemony of voices from the global north, especially the voices from white scholars occupying positions of privilege (Medie and Kang 2018 ).

Reflecting upon the aspects of academia which give (and facilitate the giving of) lifeblood to its multiple intellectual projects—such as conferences, publishing, secure and permanent posts—quickly reveals the epistemic privileges and regimes that are sustained: conferences which are too expensive to attend and sometimes require visas; Anglo-American normative assumptions regarding what constitutes a research paper—both stylistically and substantively; and networks which reinforce patterns of exclusion within the job market. Thinking honestly about the power implicit within the gender and politics field necessitates that we act differently and devise new ways of working that offer not only greater accessibility but also offer a radically different vision of what academia could be. In this instance then we call for a greater reflection on praxis, and specifically recalling the role that social movements play as a key source of gender and politics research.

How we conceptualise the field of gender and politics necessarily shapes who we seek to include, and what flows from that in terms of what we consider legitimate and important knowledge. Interdisciplinarity and its importance for gender scholars is a critical aspect of this; avoiding the temptation to police the boundaries of politics and political science in order to create intellectual synergies across a variety of fields (Ashworth 2009 ). Refusing to shut down or close off what we consider political science to constitute is important, and mirrors concerns within feminist and LGBTIQ+ social movements (Braidotti 1991 ), especially when we, as gender and politics scholars, recognise that politics is about power and that power is gendered (Ahrens et al. 2018 ). Creating opportunities and spaces in which we pay attention to the politics of privilege but also to the politics of experiential knowledge, of standpoint theory, and of the politics of language, provides us with the opportunity to reimagine a more open and engaged political science. Bringing together the core strands within our field with theoretical frameworks which have not traditionally served as dominant frames or paradigms—notably postcolonial and decolonial theory—will raise fresh questions and challenges for us as a discipline forcing us to revisit received wisdoms, established concepts and traditional methods; for example, by making better use of decolonial research methods and better integrating participatory action research (PAR) into our methodology.

The reproduction of hegemonies and continued marginalization of feminist political analysis in “mainstream” political science

The ongoing questioning of hegemonies and marginalizations in political science is another key challenge for politics and gender subfield. Despite the evidence of its expansion and increasing consolidation in European political science, dominant approaches within the discipline, that according to a political science textbook open to pluralism such as Colin Hay’s ( 2002 ) are rational choice theory, behaviouralism and new institutionalism, still tend to treat gender and sexuality issues as a marginal area (Kantola and Lombardo 2017 ; Smith and Lee 2015 : 50). Gender and sexuality teaching and research in European political science and other departments tends to be marginalized (Mügge et al. 2016 ), demonstrating a resistance to mainstreaming gender by actors that seek to maintain their privileged status quo (Verge et al. 2018 ). Men are overrepresented in the discipline and political science still perpetuates androcentric biases (Celis et al. 2013 ). While, at the initiative of the ECPR, European political science journals are beginning to analyse their gender publication gap (Grossman 2020 ; Closa et al. 2020 ), identifying a gender submission gap of 22% of at least one woman author in European Political Science Review and 27% woman leading author in the European Journal of Political Research, studies show that women are still underrepresented in political science publications despite their number in the discipline (Teele and Thelen 2017 ). Gender citation gaps, produced by implicit biases, lack of senior women scholars, and men’s tendency to cite men, are problematic for women’s career advancement and create the perception that men’s research is more important than women’s (Brown and Samuels 2018 ). Maliniak et al.’s ( 2013 ) analysis of IR top journals shows that articles authored by men obtain 4.8 more citations than women-authored articles in the period 1980–2006, after controlling for many variables. It was thanks to academic-activist platforms such as Women and People of Color Also Know Stuff! Footnote 3 that the lack of gender and diversity in conference panels, as well as the devaluing of women and people of colour’s expertise in public institutions and the media was exposed (Wallace and Pepinsky 2019 ).

The relatively marginal status of gender and politics within political science not only underestimates the scope of this subfield but also influences the type of feminist political science approaches that are more accepted in the mainstream. Out of the five feminist approaches to political analysis that Kantola and Lombardo discuss in “Gender and Political Analysis” ( 2017 ), two have become more dominant in gender and politics debates: a women approach, that focuses on the role and position of women, and a gender approach, that focuses on the wider social structures that reproduce domination and inequalities. Approaches that focus on the intersection of gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, disability, age and other inequalities are recognised as important within the field, but are not consistently applied in research. Two approaches remain more marginal: discursive approaches, that focus on how gender is contested and constructed in political debates, and post-deconstruction approaches, that focus on the role of affects, emotions and bodily material in gender and politics.

The hegemonies and marginalizations reproduced within gender and politics are as problematic as those occurring in mainstream political science with gender studies. As crucial political phenomena such as democratization, democratic backsliding, economic crises, Europeanization or Covid-19 crisis need the whole plurality of political science perspectives to maximize the explanatory capacity of science, different feminist approaches to political analysis are needed to offer a comprehensive understanding of the political in all its angles (Guerrina et al. 2018 ; Kantola and Lombardo 2017 ). Consequently, implementing practices that make space for a diversity of voices, subfields, and approaches is crucial in the road to construct a truly inclusive and intellectually heterogeneous discipline.

The changing link between academia and “society”

Linking “theory” and “practice” (i.e. praxis) is central to most feminist scholarship, and to gender and politics debates too as indicated above. Rather than simply describing and explaining “the political”, feminist political analyses seek to promote gender equality and diversity in social relations and politics (Kantola and Lombardo 2017 ). As Brown ( 2002 ) argues, connecting theory and political praxis is, indeed, needed to prevent debates within increasingly professionalized disciplines such as political science, from becoming self-referential and thus narrow in their analytical and imaginative capacities. Brown criticizes US political science as a professionalized discipline becoming accountable only to itself, where political scientists are their own audience and judges, and its existence justified by peer-reviewed journals, conferences and prizes (Brown 2002 : 565).

The intimate and necessary link between academia and societal practices potentially constitute vulnerabilities within gender and politics scholarship, too. The rise of (radical) right populism has fuelled distrust in “elitist” or “leftist” science and constrains the relationship between academia, academic knowledge and the society. Gender and politics scholars have demonstrated the multiple ways in which feminist academic knowledge and societal critique can become co-opted and compromised, thus losing its critical political edge when trying to fit with the prevailing logics of neoliberal governance (Caglar et al. 2013 ; Griffin 2015 ; Prügl 2016 ). New concepts such as market feminism (Kantola and Squires 2012 ), governance feminism (Prügl 2016 ), or crisis governance feminism (Griffin 2015 ) describe the transformations that engaging with neoliberal polities and policy-making brings for feminist knowledge. Consequently, some scholars argue that governance feminism has been markedly silent about the gendered underpinnings of global governance and financial governance, focusing instead on supporting institutional measures to enhance women’s participation (Griffin 2015 : 66).

Academic feminist actors face particular challenges of not being heard when they engage in political debates about the economy, especially in the context of neoliberalism and the dominance of austerity politics. Simultaneously, academic feminist actors who are willing and able to negotiate the terrain of such a political context have adopted specific strategies to do this. Such strategies require both “discursive virtuosity” (speaking the right language without compromising one’s agenda) but also “affective virtuosity”, a term that Elomäki et al. ( 2019 ) have coined to move forward from the pessimistic governance feminism interpretations of these engagements to instead point to the ambivalences in the engagement with the neoliberal governance. Whereas discursive virtuosity is about manifesting command of contradictory aims and discourses in equality work (Brunila 2009 ), affective virtuosity entails not only the competence to analyse and negotiate the conflicting emotions in the room but also within oneself. Affective virtuosity then requires controlling one’s feelings and emotions in gender equality work that is done with practitioners, yet it also makes openings for moving forward the gender equality agendas in hostile environments (Elomäki et al. 2019 ).

Growing opposition to gender studies programs and research

Finally, growing opposition, known as “anti-gender movement” (Kuhar and Paternotte 2017 ), challenges gender studies programs and research in both Western and Eastern Europe. Gender studies departments and courses at universities have been attacked and denounced as nests of “gender ideology”. Several governments and research agencies restricted funding, abolished accredited study programs, defamed “gender” as conspiracy theory, denounced certain gender and sexuality research topics as ideological and unscientific, or publicly discredited respective scientists as a privileged elite spending taxpayers’ money on irrelevant issues.

The anti-gender movement grew over the last fifteen years, emerging from groups of so-called concerned citizens, who were closely linked to the new evangelisation processes of the Roman Catholic Church. Eventually they have grown into a broad network of not only religious, but also nationalist, radical right-wing and other actors, united in their struggle against a seemingly unstoppable and irreversible process of ensuring gender equality and sexual rights.

The anti-gender movement ideology has penetrated and became part of some official state politics as well. Best-known is certainly the decision of the Hungarian government in October 2018 to revoke the accreditation of gender study programs in Hungary. Orban’s successful attack on university autonomy and academic freedom led to Central European University (CEU) moving to Vienna, while the Hungarian Academy of Sciences lost its institutional and financial autonomy (Pető 2018 ). Similar anti-gender attacks increasingly appear also in other European countries, such as Poland, Italy, France, Romania and Bulgaria (Engeli 2020 ; Kuhar and Zobec 2017 ; Paternotte and Verloo 2020 ).

The denunciations, particularly when unchallenged by (political) science associations, threaten the gender and sexuality subfield: public funding calls exclude gender topics, scholars avoid gender-related topics for fear of political consequences or simply by political interventions into research processes (Paternotte and Verloo 2020 ). Over the years, we have witnessed several attempts of the anti-gender actors to establish an “alternative” field of knowledge production by negating “gender” as a concept and dismantling post-structural research in social sciences and humanities. Scientific journals run by anti-choice organizations, research institutes run by politicians, or methodologically problematic studies pushed through a peer review process and published in scientific journals, remain a key challenge for science and particularly gender and sexuality research Footnote 4 (Kuhar 2015 ; Paternotte and Verloo 2020 ). However, these attacks are also an opportunity for additional internal consolidation of the scientific field, as they create an increasing solidarity among politics and gender scholars.

Over the past twenty years, the field of “gender and politics” has flourished in European political science, which is exemplified by its internal growth, diversification and professionalization, and increased disciplinary recognition. This consolidation creates specific opportunities, but also brings several key challenges which will require new, innovative and feminist thinking to safeguard gender and politics research in the twenty years to come.

Regarding internal consolidation, we ought to address internal hegemonies and marginalizations within gender and politics by practicing academic reflexivity (Bacchi 2009) or developing awareness regarding biases that shape political analyses. This includes among others practicing openness to theoretical and methodological pluralism, interdisciplinary work, the combination of different feminist approaches to political analysis, and the continuous contestation of unequal norms and practices in the subfield. One way to respond to this demand is by organizing conference sections more along research topics or problems, and less along political science subfields, thereby potentially breaking up “knowledge communities” and promoting interdisciplinarity as an advantage.

Important steps still need to be taken to support the participation and career (in terms of conference fees, awards, networks) of minority scholars, early career scholars, scholars from the Global South and scholars at risk. Next to earmarking support funds and fee waivers, one additional practical step could be to further explore online participation as a possibility to make conferences more accessible for those with limited travel opportunities.

External resistances to gender and politics research come in the form of continued marginalization of feminist political analysis and growing anti-gender attacks in several parts of Europe. Making political sciences more inclusive thus requires not only a strong commitment, but also targeted actions by all actors involved. PSAs can recommend to and support journals in a) recruiting gender-race-sexuality diverse editorial boards, b) including gender experts among reviewers by default, and c) regularly inviting special issues on gender and politics research. They can also promote positive action policies (quotas, awards, and recognition of support) for gender, sexuality and intersectionality research(ers). Further core actions can include making data on inequality visible and accessible, monitoring resistance, and encouraging and rewarding collaborations across political science subfields in conferences or journals with some of them specifically addressing opposition to gender equality in the discipline.

For the broader societal context, issues of gender, sexuality, race and intersectionality require further consolidation in European political science curricula in order to ensure the continuation of the subfield through new generations of scholars and practitioners. Such a focus needs stronger (supranational) institutional commitments protecting academic freedom and gender equality, such as limiting research funding for institutions without a gender and diversity equality plan. Simultaneously, research into democratic backsliding, particularly in terms of how it endangers (political) scientific research and academic freedom, requires strong support from funding agencies, PSAs and universities.

Considering the fact that (political) science is accused of being detached from “ordinary people” and everyday life experiences, we also need more thought and discussion (and research) into how to make a bridge. Engaging more with stakeholders and making more social impact research available can help to bring theory and praxis closer together. Concomitantly, developing and sharing individual and collective strategies of alliances and empowerment to make gender mainstreaming work and cope with resistances, might help to break through the status quo within academic, political, and economic institutions.

In sum, we need to return to the origins of gender, sexuality and intersectionality research.

We understand decolonizing to refer to those strategies which include and amplify the perspectives of those outside of the west and the global north (understanding that these terms are themselves to some extent a construct of western imperialist epistemology) to disrupt and contest our understanding of subjectivities (Sabaratnam 2011 ).

The first ECPG in Belfast 2009 had some 300 participants to the most recent in Amsterdam, 2019 which attracted over 850 attendees. The growth of the conferences Sections included: European Politics; Governance and Public Policy; International Relations; Political Participation and Public Opinion; Political Theory; Power and Representation; Research Methods; Social Movements and Civil Society; and extended in 2013 with a section on Intersectionality and one on Sexuality.

See https://womenalsoknowstuff.com and https://sites.google.com/view/pocexperts/home , accessed 2 November 2020.

On a positive note, opposition could also become a potential source of internal consolidation as it could create solidarity among politics and gender scholars.

Ahrens, P., K. Celis, S. Childs, I. Engeli, E. Evans, and L. Mügge. 2018. Politics and Gender: Rocking Political Science and Creating New Horizons. European Journal of Politics and Gender 1(1–2): 3–16.

Article Google Scholar

Ashworth, L.M. 2009. Interdisciplinarity and International Relations. European Political Science 8(1): 16–25.

Braidotti, R. 1991. Patterns of Dissonance . Cambridge: Polity.

Brown, W. 2002. What is Political Theory? Political Theory 30(4): 556–576.

Brown, N., and D. Samuels. 2018. Beyond the Gender Citation Gap: Comments on Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell. Political Analysis 26: 328–330.

Brunila, K. 2009. Parasta ennen: Tasa-arvotyön projektitapaistuminen . Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

Google Scholar

Caglar, G., E. Prügl, and S. Zwingel. 2013. Introducing Feminist Strategies in International Governance. In Feminist Strategies in International Governance , ed. G. Caglar, E. Prügl, and S. Zwingel, 1–18. London: Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Celis, K., J. Kantola, G. Waylen, and S.L. Weldon. 2013. Gender and Politics: A Gendered World, a Gendered Discipline. In The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics , ed. G. Waylen, et al., 1–26. Oxford: OUP.

Christensen, B., and L. Ball. 2019. Building a Discipline: Indicators of Expansion, Integration and Consolidation in Design Research Across Four Decades. Design Studies 65: 18–34.

Closa, C., C. Moury, Z. Novakova, M. Qvortrup, and B. Ribeiro. 2020. Mind the (Submission) Gap: EPSR Gender Data and Female Authors Publishing Perceptions. European Political Science 19: 428–442.

Connell, R.W. 2002. Gender . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Costa, M., and M. Sawer. 2018. The Thorny Path to a More Inclusive Discipline. In Gender Innovation in Political Science: New Norms, New Knowledge , ed. M. Sawer and K. Baker, 243–275. Palgrave: Cham.

Crenshaw, K. 1991. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: a Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine. In Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics’ in Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender , ed. K. Bartlett, and R. Kennedy, 57–80. San Francisco: Westview Press.

Dahlerup, D. 2010. The Development of Gender and Politics as a New Research Field Within the Framework of the ECPR. European Political Science 9: 85–98.

Deschouwer, K. 2020. Reducing Gender Inequalities in ECPR Publications. European Political Science 19: 411–415.

Elomäki, A., J. Kantola, A. Koivunen, and H. Ylöstalo. 2019. Affective Virtuosity: Challenges for Governance Feminism in the Context of the Economic Crisis. Gender, Work and Organization 26(6): 822–839.

Engeli, I. 2020. Gender and Sexuality Research in the Age of Populism: Lessons for Political Science. European Political Science 19: 226–235.

European Political Science. 2016. Special Issue: Diversity and Inclusion in Political Science. European Political Science 15(4).

Griffin, P. 2015. Crisis, Austerity and Gendered Governance: A Feminist Perspective. Feminist Review 109: 49–72.

Grossman, E. 2020. A Gender Bias in the European Journal of Political Research? European Political Science 19: 416–427.

Guerrina, R., T. Haastrup, K.A.M. Wright, A. Masselot, H. MacRae, and R. Cavaghan. 2018. Does European Union Studies have a Gender Problem? Experiences from Researching Brexit. International Feminist Journal of Politics 20(2): 252–257.

Hancock, A.M. 2007. When Multiplication Doesn’t Equal Quick Addition: Examining Intersectionality as a Research Paradigm. Perspectives on Politics 5(1): 63–79.

Harding, S.G., ed. 2004. The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader: Intellectual and Political Controversies . New York: Routledge.

Hay, C. 2002. Political Analysis . Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Book Google Scholar

Hill Collins, P. 2002. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment . New York: Routledge.

Jenkins, F. 2018. Gendered Innovation in the Social Sciences. In Gender Innovation in Political Science. New Norms, New Knowledge , ed. M. Sawer and K. Baker, 41–61. Palgrave: Basingstoke.

Kantola, J., and E. Lombardo. 2016. Gender and Politics Studies Within European Political Science: Contributions and Challenges. Italian Political Science 11(2): 1–5.

Kantola, J., and E. Lombardo. 2017. Gender and Political Analysis . London: Red Globe.

Kantola, J., and J. Squires. 2012. From State Feminism to Market Feminism. International Political Science Review 13(4): 382–400.

Kuhar, R. 2015. Playing with science: sexual citizenship and the Roman Catholic Church counter-narratives in Slovenia and Croatia. Women’s Studies International Forum 49: 84–92.

Kuhar, R., and D. Paternotte, eds. 2017. Anti-gender campaigns in Europe: mobilizing against equality . New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kuhar, R., and A. Zobec. 2017. The Anti-Gender Movement in Europe and the Educational Process in Public Schools. CEPS Journal 2(7): 29–46.

Lovenduski, J. 2015. Gendering politics: Feminising political science . Colchester: ECPR Press.

Maliniak, D., R. Powers, and B. Walter. 2013. The Gender Citation Gap in International Relations. International Organization 67: 889–922.

McCall, L. 2005. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs 30(3): 1771–1800.

Medie, P.A., and A.J. Kang. 2018. Power, Knowledge and the Politics of Gender in the Global South. European Journal of Politics and Gender 1(1–2): 37–53.

Mendoza, B. 2012. The Geopolitics of Political Science and Gender Studies in Latin America. In Gender and Politics: The State of the Discipline , ed. J. Bayes, 33–58. Barbara Budrich: Opladen.

Mügge, L., E. Evans, and I. Engeli. 2016. Introduction: Gender in European Political Science Education—Taking Stock and Future Directions. European Political Science 15: 281–329.

Paternotte, D., and M. Verloo. 2020. Political Science at Risk in Europe. Frailness and the Study of Power. In Political Science in Europe. Achievements, Challenges, Prospects , ed. T. Boncourt, I. Engeli, and D. Garcia, 287–310. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Petö, A. 2018. Attack on Freedom of Education in Hungary: The Case of Gender Studies. Available at https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/gender/2018/09/24/attack-on-freedom-of-education-in-hungary-the-case-of-gender-studies/ . Accessed 2 Nov 2020.

Phillips, A., ed. 1998. Feminism and Politics . Oxford: OUP.

Prügl, E. 2016. How to Wield Feminist Power? In The Politics of Feminist Knowledge Transfer: Gender Training and Gender Expertise , ed. M. Bustelo, L. Ferguson, and M. Forest, 25–42. Palgrave: Basingstoke.

Sabaratnam, M. 2011. IR in Dialogue… But Can We Change the Subjects? A Typology of Decolonising Strategies for the Study of World Politics. Millennium 39(3): 781–803.

Smith, N., and D. Lee. 2015. What’s Queer About Political Science? British Journal of Politics and International Relations 17 (1): 49–63.

Stockemer, D., A. Blair, and E. Rashkova. 2020. The Distribution of Authors and Reviewers in EPS. European Political Science 19: 401–410.

Teele, D., and K. Thelen. 2017. Gender in the Journals: Publication Patterns in Political Science. PS: Political Science & Politics 50(2): 433–447.

Verge, T., M. Ferrer-Fons, and M. González. 2018. Resistance to Mainstreaming Gender into the Higher Education Curriculum. European Journal of Women’s Studies 25(1): 86–101.

Verloo, M., and S. Walby. 2012. Introduction: The Implications for Theory and Practice of Comparing the Treatment of Intersectionality in the Equality Architecture in Europe. Social Politics 19(4): 433–445.

Vickers, J. 2015. Can we change how political science thinks? “Gender Mainstreaming” in a resistant discipline. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique 48(4): 747–770.

Wallace, S., and T. Pepinsky. 2019. Gender Representation and Strategies for Panel Diversity: Lessons from the APSA Annual Meeting. PS: Political Science and Politics 52(4): 669–676.

Yuval-Davis, N. 2012. Dialogical Epistemology: An Intersectional Resistance to the ‘Oppression Olympics.’ Gender & Society 26(1): 46–54.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Social Sciences, Tampere University, 33014, Tampere, Finland

Petra Ahrens & Johanna Kantola

Department of Political Science, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, 1050, Brussels, Belgium

Silvia Erzeel

Department of Politics and International Relations, University of London, Goldsmiths, UK

Elizabeth Evans

Faculty of Arts, Department of Sociology, University of Ljubljana, Aškerčeva 2, 1000, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Roman Kuhar

Department of Political Science and Administration, Faculty of Political Science and Sociology, Madrid Complutense University, 28223, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid, Spain

Emanuela Lombardo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Silvia Erzeel .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ahrens, P., Erzeel, S., Evans, E. et al. Gender and politics research in Europe: towards a consolidation of a flourishing political science subfield?. Eur Polit Sci 20 , 105–122 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00304-8

Download citation

Accepted : 09 November 2020

Published : 21 January 2021

Issue Date : March 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00304-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Academic knowledge

- Anti-gender movement

- Intersectionality

- Political science

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Welcome Letter

- Affiliated Faculty

- Invest in WAPPP

- Work & Gender Equity (WAGE)

- Gender & Politics

- Gender & Conflict

- Gender Action Portal

- Research Fellowship Program

- Publications

- Past Research Initiatives

- Gender Course Guide

- Training Executives

- From Harvard Square to the Oval Office

- 3-Minute Research Insights

- Student Funding

- Student Awards

- Oval Office Program

- Undergraduate Internship Program

- News & Announcements

- All WAPPP Events

- Join the WLB

- Make Your Contribution

- WLB Meetings

- WLB Members

Gender & Politics

In this section.

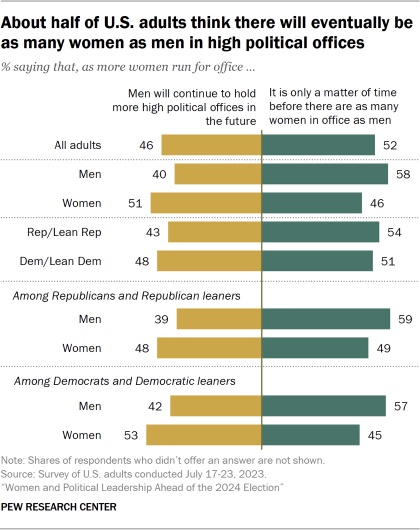

Although women can vote and run for public office in nearly every country, as of September 2022, they accounted for only 26 percent of parliamentarians worldwide and served as head of state or head of government in twenty-eight countries.

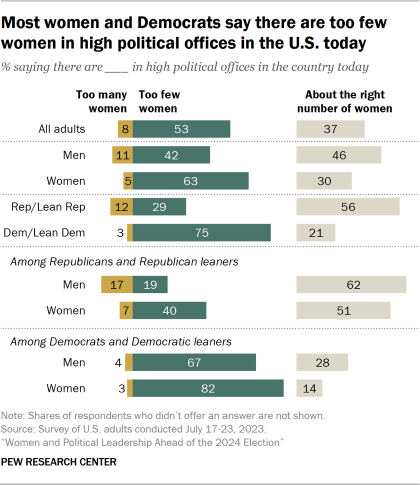

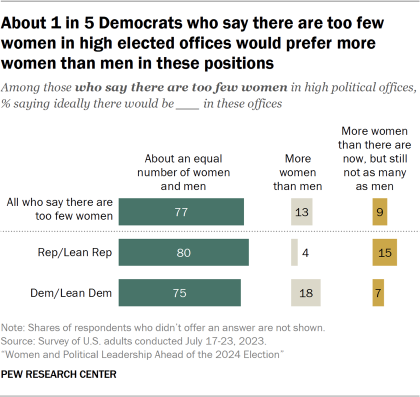

Current research posits numerous explanations for the lack of women in leadership roles, including gender discrimination, lack of female role models, aversion to competitive environments, family responsibilities , and social norms. What are the interventions that address these challenges in how we expect women and leaders to behave and increase women’s political aspirations?

Gender Quotas

Power-seeking behavior , even when unintentional, hurts female political candidates but helps male candidates. Seat reservations for female elected officials make communities more likely to associate women with leadership and vote for women in the future. Reserving political seats for women increases female electoral participation and improves governments' responsiveness to women's policy concerns. Yet, in the corporate sector, quotas have demonstrated mixed outcomes. In Norway, quotas for corporate boards increased gender diversity but imposed costs on firms and shareholders , while another study found that quotas, or affirmative action, increased women's willingness to compete in competitive mixed-gender environments, closing the gender gap and resulting in more qualified candidates, men and women alike, applying for competitive positions .

Modeling Female Leadership

Women in leadership positions have a multiplying effect: Repeated exposure to female elected officials improves perceptions of female leaders and leads to future electoral gains for women . Female role models in leadership positions help adolescent girls to aspire to leadership.

Training Programs

Mentorship, confidence building, media training , and political campaign education are all effective tools to increase adolescent girls’ and women’s political aspirations and efficacy despite structural obstacles. The Female Political Representation & Intervention Impact Map (2021) below displays the percentage of parliamentary seats that are held by women in lower-house chambers around the world. The interactive tool was created and designed using the latest data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). Together with these percentages, which show global female political representation, we can visualize how programs based on evidence-based insights—such as From Harvard Square to the Oval Office and its inspired programs—may help increase the number of female-held seats around the world.

Understanding the Post-Roe Landscape

On June 24, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade , ending nearly 50 years of constitutional protections for abortion. WAPPP has compiled resources from across Harvard University on what the historic ruling means for reproductive rights and other protected civil liberties.

Political Representation & Intervention Map

The Female Political Representation & Intervention Impact Map (2021) below displays the percentage of parliamentary seats that are held by women in lower-house chambers around the world. The interactive tool uses the latest data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU).

Latest Research Insights

Sensitive questions, spillover effects, and asking about citizenship on the us census, men and women candidates are similarly persistent after losing elections, the state of women’s participation and empowerment: new challenges to gender equality.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Gender and Politics

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Women's movement Follow Following

- Histories of Feminisms Follow Following

- Gender Studies Follow Following

- Feminist Theory Follow Following

- Feminism Follow Following

- Women's Studies Follow Following

- Gender Follow Following

- Women and Politics Follow Following

- Social Movements Follow Following

- Gender History Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The gender gap in political psychology

Associated data.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Introduction

I investigated the authorship gender gap in research on political psychology.

The material comprises 1,166 articles published in the field’s flagship journal Political Psychology between 1997 and 2021. These were rated for author gender, methodology, purpose, and topic.

Women were underrepresented as authors (37.1% women), single authors (33.5% women), and lead authors (35.1% women). There were disproportionately many women lead authors in papers employing interviews or qualitative methodology, and in research with an applied purpose (these were all less cited). In contrast, men were overrepresented as authors of papers employing quantitative methods. Regarding topics, women were overrepresented as authors on Gender, Identity, Culture and Language, and Religion, and men were overrepresented as authors on Neuroscience and Evolutionary Psychology.

The (denigrated) methods, purposes, and topics of women doing research on politics correspond to the (denigrated) “feminine style” of women doing politics grounding knowledge in the concrete, lived reality of others; listening and giving voice to marginalized groups’ subjective experiences; and yielding power to get things done for others.

Women are not equally represented in science in terms of publications and impact. This is especially true in male-dominated fields such as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), in which women are severely underrepresented both in terms of raw numbers and in terms of prestige ( Larivière et al., 2013 ; West et al., 2013 ). Moreover, a large authorship gender gap in publishing can be found not only in fields dominated by men but also in fields that approach or have reached gender parity in participation, such as education or psychology ( West et al., 2013 ).

Psychology is a discipline that is often lauded by researchers who study gender gaps in academia due to the high rate of women participating in the field, from undergraduates to tenure-track professors (e.g., Ceci et al., 2014 ). An increasing number of women with master’s degrees and doctorates have transformed psychology from a men-dominated field to a women-dominated field. Despite this representation in numbers, women in psychology remain underrepresented as authors and in eminence—women in psychology are underrepresented in first-author publications in top journals ( Brown and Goh, 2016 ), in the citations their work receives ( Odic and Wojcik, 2020 ), in award received by divisions ( Eagly and Riger, 2014 ; Brown and Goh, 2016 ), and in eminence ( Eagly and Miller, 2016 ). Although political science is strongly dominated by men ( Tolleson-Rinehart and Carroll, 2006 ; Breuning and Sanders, 2007 ; Teele and Thelen, 2017 ; Thelwall et al., 2019 ), this may be less true in the subfield of political psychology.

This research aimed to assess whether there is an authorship gender gap in articles published in Political Psychology . The journal Political Psychology incorporates contributions with a variety of methodologies and topics, as well as both theoretical research and applied research. Exploring how the authorship gender gap varies between different types of contributions could reveal how women are situated within the field. First off, the size of the authorship gender gap may vary as a function of method—women generally tend to employ more qualitative research methods than men ( Eagly and Riger, 2014 ; Thelwall et al., 2019 ). For instance, in political science, journals that publish qualitative research tend to have more female authors than journals that publish only quantitative research ( Teele and Thelen, 2017 ). Second, the purpose of the paper may be associated with the size of the authorship gender gap. Large-scale bibliometric analyses across all fields of research show that theoretical papers are more typical of men, whereas women are overrepresented as authors in papers intended to have a social impact ( Thelwall et al., 2019 ). Third, authorship gender gaps may vary across topics. For instance, gender studies are one of the few social sciences fields dominated by women ( Kretschmer et al., 2012 ), suggesting that women might not be underrepresented as authors of research on this topic.

The purpose of the present research was to investigate the possible gender gap within the field of political psychology or, more specifically, the field’s flagship journal Political Psychology . I expected women to be generally underrepresented as authors, but the size of the authorship gender gap varies according to the methods, purposes, and topics of the paper. Moreover, I also investigated whether the authorship gender gap has narrowed in the last decades (as suggested by Brown and Goh, 2016 ) and whether papers authored by women are cited less (as suggested by Odic and Wojcik, 2020 ). Pertinent to the last point, I also explored whether the number of citations varies with method, purpose, or topic. Some previous studies, run on articles published in the journal Leadership Quarterly , suggest that quantitative, review, methods, and theory articles may be cited more than qualitative articles ( Antonakis et al., 2014 ). Women could thus be expected to be cited less, and this could at least in part be explained by different citation rates for different types of papers.

Materials and methods

Two doctoral students, both of whom identified as women, were employed as research assistants, and they rated all articles that appeared in the journal Political Psychology from the start of 1997 to the end of 2021. No power calculations were made—we sought to include all articles that were available online at the time the data were collected. Between the beginning of 1997 and the end of 2021, the journal published 1,166 research articles, which constituted the material for the present study.

All articles were rated by both raters for author gender, method, purpose, and topic. Each article was rated dichotomously on all employed variables, i.e., either employing a certain method vs. not doing so, having vs. not having applied relevance, or dealing vs. not dealing with a certain topic. The rating scheme and rating criteria were discussed, developed, and revised together in the initial stages of rating, and the final rating scheme that was employed for all articles was arrived at through joint discussion after both research assistants had rated around a hundred articles. After these initial discussions, the research assistants did not discuss their ratings with each other.

The coding of methods was rather straightforward, either a given method was employed or it was not. For the article to be coded as having applied relevance, a real-world problem had to motivate a research question, or the applied relevance had to be mentioned in the abstract. Regarding the topic, the focus was on the framework within which the research was conducted. For instance, speculating upon an “identity” or “evolutionary psychology” explanation of the results did not suffice for the paper to be coded as being within these fields. In addition to discussions with the two research assistants, I relied on political psychology handbooks and research on the submissions to the journal Political Psychology ( Mintz and Mograbi, 2015 ) in developing the rating scheme.

There were generally more men ( n = 1681) than women ( n = 991) as authors (37.1% women). Looking at the first author or single author, there were again more men ( n = 757) than women ( n = 409; 35.1% women), and the same was true when looking only at single authors (250 men, 126 women; 33.5% women). Women were thus similarly underrepresented both as co-authors and as lead authors.

The gender gap in lead authorship over time is plotted in Figure 1 . There is no indication that the gender gap in authorship would have decreased over time [the linear correlation between the year of publication and the percentage of female lead authors was r (25) = 0.02]. However, the slight dip in the percentage of female lead authors suggested investigating gender representation among the editors of the journal. Between 1997 and 2021, there were two to four (co-)editors each year. The editors were all male from the beginning of 2006 to the end of 2011. All other years, there was one woman among the (co-)editors. Between 2006 and 2011, the all-male years, only 29.7% of lead authors were women. In contrast, the average of those years in which one woman was included as (co-)editor, the percentage of women lead authors was 36.6% [this difference in percentages did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance, F (1, 24) = 3.25, p = 0.084].

The percentage of female first authors over time.

To analyze differences between topics, methods, and purposes, one rater’s rating of the gender of the lead author (first author or single author) was used as the independent variable (rater’s agreement on author gender was 99.5%, and kappa was 0.989).

Tables 1 – 3 show the number of male and female lead authors by method, purpose, and topic, respectively. Not surprisingly, given that the proportion of female lead authors was only 0.351, there were fewer women than men in almost all categories. However, there were some exceptions. Regarding methods, there were as many women as men employing qualitative methods and interviews (the number of women and men lead authors employing these methods did not differ statistically significantly at p < 0.05). Regarding the topic, there were as many women as men lead authors writing about Gender, Religion, Social Control, and Class (the number of women and men lead authors writing on these topics did not differ statistically significantly at p < 0.05).

Number of papers with male and female lead authors across methods.

The Chi-square and the Phi statistics show whether either gender is disproportionately represented as lead author. The inter-rater agreement and Cohen’s kappa statistics estimate inter-rater reliability.

Number of papers with male and female lead authors across theme.

Given the generally large authorship gender gap in favor of men, more informative than analyzing the absolute numbers of men and women as lead authors were to look at the relative number of men and women. Chi-square tests were run to investigate, given the general overrepresentation of men, whether the authorship gender gap varied across methods ( Table 1 ), purposes ( Table 2 ), and topics ( Table 3 ). Regarding methods, there were disproportionately many women lead authors in papers employing qualitative methods or interviews. In contrast, men were overrepresented as authors of papers employing quantitative methods. There were also disproportionately many women lead authors in research with an applied purpose. Regarding the topic, there were disproportionately many women lead authors within the fields of Gender, Identity, Culture and Language, and Religion. There were some indications that this might also be true for Ethnicity and Political Participation, although conventional levels of statistical significance were not reached. On the contrary, there were disproportionately many men as lead authors in papers on Evolutionary Psychology and Neuroscience.

Number of papers with male and female lead authors across purpose.

To alleviate fears that the above results were being driven by only some variables, I analyzed the associations between variables: methods, purposes, and topics. The strongest association was between qualitative methods and the topic of Culture and Language, with an effect size of φ = 0.252 [χ 2 (1, 1066) = 74.784]. Entering these two variables into a binary logistic regression predicting author gender gave very similar coefficient estimates regardless of whether the two variables were entered alone or simultaneously (all coefficient p -values in both types of models were statistically significant at p < 0.01). This suggests that the associations between, on the one hand, methods, purposes, and topic and, on the other hand, gender were generally rather independent of each other.

Regarding the number of citations, there was no gender bias. Male lead authors had an average of 102 ( SD = 192) citations, and female first authors had an average of 93 [ SD = 166; F (1, 1164) = 0.722, ns]. Of the 50 most-cited articles, 18 (36%) had a female lead author, which is almost exactly what one would expect given that 37% of all lead authors were women. Similarly, when looking at the top 10 most-cited articles, three of them had a female lead author.

Although articles authored by women were, contrary to expectations, not cited less frequently, the types of papers for which women were overrepresented as authors were cited less frequently. As expected, papers employing qualitative methods ( Table 4 ) and having an applied focus ( Table 5 ) were cited less often. However, the topics that women authors were overrepresented on were not cited particularly poorly, with the exception of Culture and Language ( Table 6 ).

Mean number of citations across employed methods.

F and η 2 statistics for the difference in mean citations between papers in which the method was or was not present.

Mean number of citations across purposes.

F and η 2 statistics for the difference in mean citations between papers in which the purpose was or was not present.

Mean number of citations across themes.

F and η 2 statistics for the difference in mean citations between papers in which the theme was or was not present.

The first finding was that only 37.1% of the authors who published their articles in Political Psychology in 1997–2021 were women (33.5% single authors, 35.1% first authors). The average for the top 200 psychology journals from 2003 to 2018 was 44.2% ( Odic and Wojcik, 2020 ). The most important finding for a wider audience was that the authorship gender gap was not identical across various methodological approaches, research purposes, and research topics—i.e., women scholars were different in how (methods), why (purpose), and what (theme) they did. This result was especially intriguing given that the journal investigates politics. Politics is of course not gender-neutral—women politicians are expected to be different in how, why, and what they do. One of the questions the results provoke is whether research on politics is gendered similarly to how politics is gendered. That is, gender differences in what political psychologist do may be parallel to gender differences in what politicians do.

Regarding methodology, women were, relative to the general authorship gender gap in favor of men, overrepresented as lead authors in research employing qualitative methods and interviews. Women were also overrepresented in research with an applied purpose. These results are consistent with previous large-scale cross-disciplinary bibliometric results ( Thelwall et al., 2019 ). The similarities between how and why women do research and how and why women do politics are striking. A “feminine style” in women’s political discourse has been argued to consist, among other things, of basing political judgments on concrete, lived experience; valuing inclusivity and the relational nature of being; conceptualizing the power of public office as a capacity to “get things done”; and moving women’s issues to the forefront of the public arena ( Blankenship and Robson, 1995 ). This “feminine style” ascribed to women politicians could just as well describe the results for women scholars. Several approaches within qualitative research, especially when interviews are employed, have been thought of as seeking to capture “lived experience” ( Frechette et al., 2020 ), legitimize the subjectivity of human reality ( Morgan and Drury, 2003 ), or “give voice” to those who are rarely heard ( Larkin et al., 2006 ). Women in politics and women scholars seem to ground their knowledge in the concrete, lived reality of others (their electorate or their research participants), listening and giving voice to marginalized groups’ subjective experiences, and yielding their own power or their voice for the sake of others. This is all very consistent with the broader stereotype of women as highly communal (i.e., kind, warm, empathetic, and caring) and less agentic (i.e., analytical, independent, and competitive) than men ( Fiske et al., 2002 ).

In addition, consistent with these broader stereotypes are the topics, on which women were, given the general authorship gender gap in favor of men, overrepresented: Gender, Identity, Culture and Language, and Religion. Two topics that narrowly missed the cut-off points for statistical significance were Political participation and Ethnicity. It is again rather striking that the topics women scholars work on are the very same type of topics that women politicians are associated with. In electoral politics, even though women’s overall proportions in the governments of developed democracies have increased considerably over the last few decades, women cabinet ministers in charge of the most prestigious (i.e., pivotal, resourceful, and visible) positions remain an exception ( Krook and O’Brien, 2012 ; Kroeber and Hüffelmann, 2021 ). Women members of government typically preside over low-prestige portfolios, such as Women, Equality, Minority Affairs, Culture, Minority Affairs, and Immigration ( Kroeber and Hüffelmann, 2021 ). These portfolios are very similar in content to the above topics on which women authors were overrepresented.

Besides affinities in the methods, purposes, and topics, of women scholars and politicians, there are similarities in the prestige that they are afforded. Regarding research methods, policymakers are infatuated with the number and quantitative methods, particularly at the intersection of science and bureaucracy ( Porter, 1995 ). Also in the present study, qualitative research was poorly cited. This was consistent with previous research on the citation rates of leadership research ( Antonakis et al., 2014 ), as well as with the present result that papers with a more applied focus were poorly cited. That applied papers, like qualitative papers, may lack prestige can be inferred not only from citation rates but also from a recent Association for Psychological Science presidential column, in which it was noted that “Many of us in academia may be walking around with an implicit or explicit ‘basic is better’ attitude” ( Medin, 2012 ). Thus, although women were not per se less likely to be cited than men, the type of research that women did was less likely to be cited.

Regarding the topics of the research, Gender, Identity, Culture and Language, and Religion, also maybe Ethnicity and Political Identity, are all topics that in eyes of both other psychologists and laypeople are perceived as less rigorous, mainstream, and objective than research in areas of psychology, and the researchers engaged with this type of research on identity or “me-search” ( Rios and Roth, 2020 ) are seen as more subjective and less intelligent ( Rios and Roth, 2020 ; Brown et al., 2022 ).