- Event Website Publish a modern and mobile friendly event website.

- Registration & Payments Collect registrations & online payments for your event.

- Abstract Management Collect and manage all your abstract submissions.

- Peer Reviews Easily distribute and manage your peer reviews.

- Conference Program Effortlessly build & publish your event program.

- Virtual Poster Sessions Host engaging virtual poster sessions.

- Customer Success Stories

- Wall of Love ❤️

How to Write an Abstract For a Poster Presentation Application

Published on 15 Aug 2023

Attending a conference is a great achievement for a young researcher. Besides presenting your research to your peers, networking with researchers of other institutions and building future collaborations are other benefits.

Above all, it allows you to question your research and improve it based on the feedback you receive. As Sönke Ahrens wrote in How To Take Smart Notes "an idea kept private is as good as one you never had".

The poster presentation is one way to present your research at a conference. Contrary to some beliefs, poster presenters aren't the ones relegated to oral presentation and poster sessions are far from second zone presentations; Poster presentations favor natural interactions with peers and can lead to very valuable talks.

The application process

The abstract submitted during the application process is not the same as the poster abstract. The abstract submission is usually longer and you have to respect several points when writing it:

- Use the template provided by the conference organization (if applicable);

- Specify the abstract title, list author names, co-authors and the institutions in the banner;

- Use sub-headings to show out the structure of your abstract (if authorized);

- Respect the maximum word count (usually about a 300 word limit) and do not exceed one page;

- Exclude figures or graphs, keep them for your poster;

- Minimize the number of citations/references.

- Respect the submission deadline.

The 3 components of an abstract for a conference application

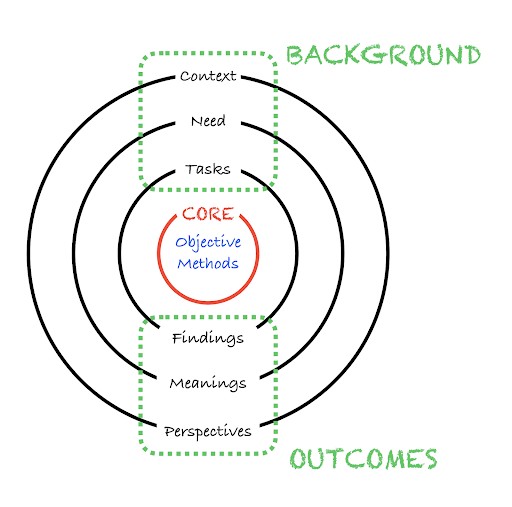

Most poster abstract submissions follow the classical IMRaD structure, also called the hourglass structure.

To make your abstract more memorable and impactful, you can try the Russian doll structure. Contrary to IMRaD, which has a more linear progression of ideas, the Russian doll structure emphasizes the WHY and WHAT. It unravels the research narrative layer by layer, capturing the reader’s attention more effectively.

Your abstract should be something the reviewer wants to open in order to discover the different layers of your research down to its core (like opening a Russian doll or peeling an onion). Then, it should be wrapped up elegantly with the outcomes (see figure below) like dressing the same Russian doll.

Hence, to design the best Russian doll, I recommend Jean-Luc Doumont's structure as detailed in his book Trees, Maps and Theorems that I adapted in 3 main components:

1. Background. The first component answers to the WHY and details the motivations of your research at different levels:

- Context : Why now? Describe the big picture, the current situation.

- Need : Why is it relevant to the reader? Describe the research question.

- Tasks : Why do we have to do this way? Review the studies related to your research question and emphasize the gap between the need and what was done.

2. Core . The center component answer to the HOW and consists in describing the objective of your research and its method:

- Objective : How did I focus on the need? Detail the purpose of your study.

- Methods : How did I proceed? Describe briefly the workflow (study population, softwares, tools, process, models, etc.)

3. Outcomes . The final component answers to the WHAT and details the take-aways of your research at different levels:

- Findings : What resulted from my method? Describe the main results (only).

- Meanings : What do the research findings mean to the reader? Discuss your results by linking them to your objective and research question.

- Perspectives : What should be the next steps? Propose further studies that could improve, complement or challenge yours.

It's worth noting that this structure emphasizes the WHY and the WHAT more than the HOW. It is the secret of great scientific storytelling .

The illustration below provides a clearer understanding of the logical flow among the three components and their respective layers. Note that, if authorized, sub-headings can be used for each section mentioned above.

4 tips to help get your abstract qualified

Here are some tips to give yourself the best chance of success for having your poster abstract accepted:

- Start by answering questions . It is very hard for the human brain to create something totally from scratch. Hence, allow the questions detailed above to guide you in creating the first path to explore.

- Write first, then edit . Do not try to do both at the same time. You won't get the final version of your abstract after your first try. Be patient, and "let your text die" before editing it with a fresh new point of view.

- "Kill your darlings'' . Not everything is necessary in the abstract. In Stephen Sondheim's words , West Side Story composer, "you have to throw out good stuff to get the best stuff". You will be amazed at just how surprising and efficient this tip is.

- Steal like an artist . As suggested by Austin Kleon's book title , get inspiration from others by reading other abstracts. It can be very helpful if you struggle finding punchy phrasing or transitions. I'm not referring to plagiarism, only getting good ideas about form (and not content) that can be adapted and used in your abstract.

When you get accepted, it's time to design your poster board and prepare your pitch. Pick your favorite graphics software and bring your abstract to life with figures, tables, and colors. We have written an article on how to make a scientific poster , do not hesitate to take a look.

5 Best Event Registration Platforms for Your Next Conference

By having one software to organize registrations and submissions, a pediatric health center runs aro...

5 Essential Conference Apps for Your Event

In today’s digital age, the success of any conference hinges not just on the content and speakers bu...

How to Create an Effective Poster Presentation (A Nurse Student?s Guide)

When preparing to present a thesis, capstone project , or dissertation , it is best to create an abstract poster. The poster will help you to give potential attendees the information they need to decide if they will attend your presentation.

Nurses, clinicians, and researchers share information on programs they develop or their studies through abstract posters. It aids in sharing clinical wisdom and advancing the knowledge of nursing and other healthcare professionals. Presenting poster abstracts is a common practice in conferences and seminars.

In this post, we will reveal everything you need to know about creating an abstract poster. You should be able to create a brilliant abstract poster when you read this article.

What Is a Poster Abstract?

An abstract poster, aka poster abstract, is essentially an advertisement for a research presentation, and it is prepared by the research author to give potential presentation attendees a glimpse of the research.

A poster abstract is typically 300 words long, and it takes between 30 minutes to 60 minutes. Writing takes longer because it involves summarizing an entire research project into a one-page summary.

A good poster abstract uses a few sentences to capture the essence of a research project perfectly, and it is not and should never be just a basic summary of a research project.

When asked to write a poster abstract for a conference, you will most likely be given some requirements to follow. The requirements will undoubtedly include the format to follow, the word limit, and the deadline to adhere to.

A well-written abstract describes the research questions, PICOT questions, or clinical problems. It also entails the methods used to address the clinical issues and the significance and implications of the results.

Parts of A Poster Abstract

When tasked to write a poster abstract, or if you are doing one for an upcoming nursing or interprofessional conference relevant to your field, you must make sure it includes the following parts:

- Title and Author (s). This comes in the top section of the poster, and it includes the title and names of the contributing authors. The poster's title should be the same as the abstract, and it should be clear, concise, and in an easy-to-read font. You should include the credentials and institutional affiliations of the authors and add organizational logos if possible.

- Background: Your poster abstract should begin by providing the background of your research project, and it should do this by introducing the problem you investigated in your research.

- Methods: Your abstract poster should have a methods section that explains the ?how? of your project. In this part of your poster, you are supposed to summarize how you did your project. One or two sentences are enough for this part; unnecessary words are unnecessary.

- Results: The results part of your abstract is perhaps the most important since it is where you highlight your most important findings. Highlight your key findings here without offering any interpretations or explanations. Let those interested in the interpretation and discussion part of your research attend your presentation.

- Conclusion: This should be the last part of your poster abstract. It should present the reader with a brief overview of the conclusions you made in your research, and it should also mention the implications of your study.

- Future Plans: This section can include a few sentences of recommendations for some research or plans to follow up on the initiative or program.

- References: List all your references in alphabetical order.

- Acknowledgments: Acknowledge any contributors, funding agencies, and institutions.

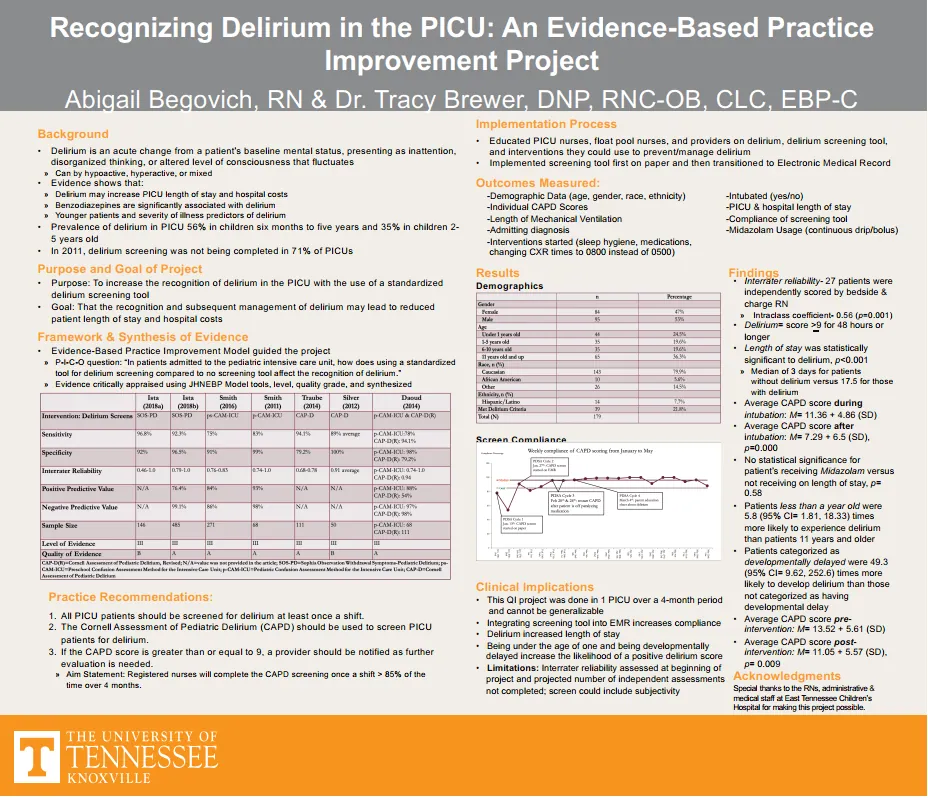

An abstract for a nursing capstone project will slightly differ. It will have the following sections:

- Purpose and goal statement

- Framework and synthesis of evidence

- Practice recommendations

- Implementation process

- Outcomes measures

- Clinical implications

Check the example below from The University of Tennessee Knoxville

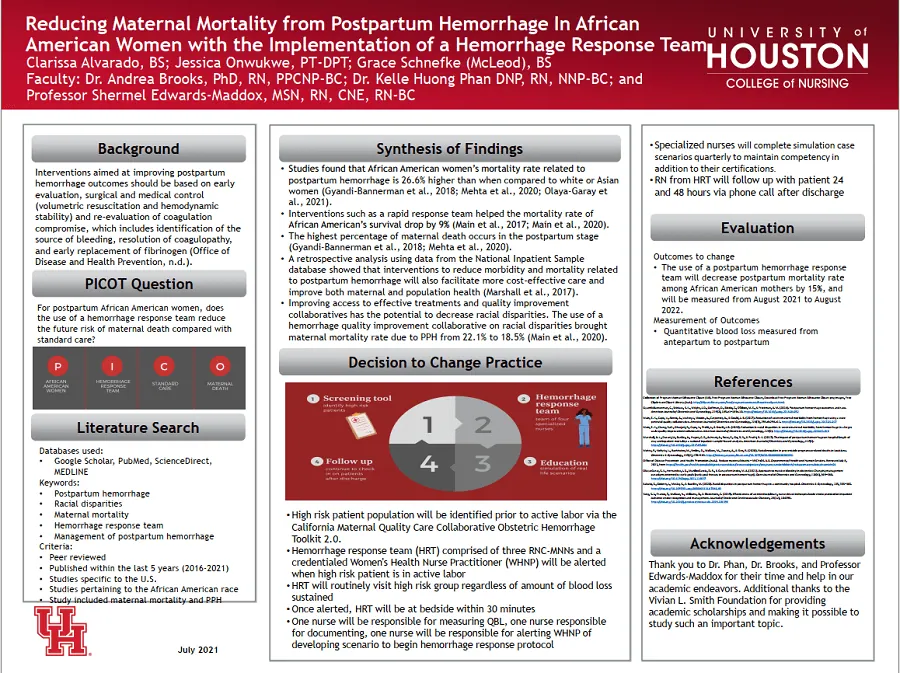

If you are focusing on a change project or a Quality improvement project , it will include the background; PICOT question ; literature search, synthesis of findings; recommended changes to practice; evaluation; references; and acknowledgments. See the attached example from the University of Houston (College of Nursing)

Steps for Preparing a Poster Presentation

Your journey to making an excellent abstract and a poster begins by searching for upcoming nursing conferences or other related interprofessional seminars. You can also ask your colleagues about their experiences and the conferences they have attended. Your mentor can also come in handy but make sure you read the call for abstract posters to know what is expected, such as the scope of the conference and how to design the posters.

1. Do Some Planning

Planning is the first thing you need to do regarding your poster presentation. During your presentation, brainstorm and think about what you want people to know about your research, and Note down everything you want them to know.

These notes will help you ensure your abstract is comprehensive and genuinely insightful. You should also create enough time to work on your abstract and poster before the deadline.

When planning, reviewing abstracts from past conferences or classes is best. Study them for style, content, and scope so that yours succeeds. Preparing your information dissemination process should commence early so that you cover all the mandatory aspects.

2. Write Your Abstract

This is the most important part of your poster abstract preparation process. A good poster abstract is short and clear. Be sure to include all the important details of your work in the abstract poster. It is, however, best to avoid having your work?s fine details in the poster abstract. And similar to all other academic writing styles, any statement requiring a reference within the abstract should be referenced (cited). You are, nonetheless, advised to limit the specific need for references in your abstract; only the important referable statements should be included.

When drafting the abstract, ensure you meet the correct length, use relevant headings and sections, and include citations. It would be good to let your thoughts flow at first when drafting so that you shorten the draft as you edit and proofread it.

Below is an excellent example of abstract criteria that you can use when writing your abstract:

- Concisely and written abstract

- A title that well describes the poster abstract

- Statement of a clear objective

- Significance to the theme of the conference

- The approach used appropriately to objectives

- Analysis and outcomes well applied and construed

- The work?s weaknesses and strengths are highlighted

- Suggestions for future work stated

- Appeals to a globally diverse crowd

3. Review the Abstract

When you finish the initial draft, setting aside a day or two to refresh your mind and be as objective as possible is important. After the break, read the draft with a ?fresh? pair of eyes so that you can notice and eliminate redundancies and errors, and reword the entire abstract.

If you spot any unclear statements or jargon, make the necessary corrections. As you review, assess the flow and logic of your abstract and correct it as necessary. Ensure that all clinical jargon and abbreviation is illustrated in a way that makes sense to the target audience.

It would help if you also welcomed your peers to review the abstract. The rationale of a peer review is to ensure that the errors, omissions, and mistakes that escaped your eyes are arrested and corrected. You can consult your supervisor or mentor for a critical peer review.

Suppose you can get someone outside of your discipline, the better because they will breathe a fresh perspective on the clarity and logic of the content. As intimidating and rigorous as it might be, a peer review often helps you submit an abstract that makes sense. Besides, you can make a poster that comprehensively addresses the readers' needs.

4. Design Your Poster

Designing the poster is the most fun part of the entire process. There are, however, certain rules that you might have to follow before you begin. First and foremost, confirm the required poster size and poster orientation; landscape or portrait. If uncertain, the safest guess is a portrait, which will most likely fit on the conference?s typically sized-poster boards.

It is also important to choose the software within which you?ll design your poster. The most often used options are Adobe Illustrator, Microsoft Office PowerPoint, and CorelDraw . Whichever software you choose; you should always begin by setting up the page size. Let?s say somebody is a meter away from the conference board; the smallest font size they?ll be able to read quickly is around 20 points, assuming your page is appropriately sized.

With regard to readability, light writing on dark backgrounds and vice versa works well, and the restricted usage of varying font types and sizes also works great. Simply put, it is a delicate balance between utilizing these particular aspects to offer structure to your presentation and excessively complicating your structure, making it hard to navigate.

Use diagrams instead of words to describe key principles, methods, and outcomes if possible. Apart from being visually appealing, diagrams are quicker and easier for individuals to process. Remember that people typically spend a few seconds or minutes reading each poster, so the simpler the information is to absorb, the better.

Consider using software features like guides and snap-to-grid when presenting your details on the poster. This is vital as small disparities in alignment on the computer monitor can be emphasized on a poster printout. That said, attention to detail is vital. Proofreading a poster when restricted to a small size monitor is usually challenging. For that reason, you should consider requesting a colleague or friend to take another look for any typing errors.

All authors of the work and their institutional affiliations should be included in the poster?s upper title section. The presenter and the poster?s designer typically sit as the first author and the work?s principal investigator or most senior author as the last author. For the order of the middle authors, the team is left to discuss and agree. Any acknowledgments to organizations and individuals that are not authors are featured at the bottom of your poster.

5. Print and Prepare for Poster Presentation

Printing out your poster is the last step. As you think about designing your poster, you should also think of this particular step, as it is crucial to have knowledge of the printing timescales. The chosen printer could provide same-day service or might take a couple of days to turn around if busy. You may also need to send your poster off-site for other purposes, like lamination.

The paper?s weight not only determines the cost of the print but also how robust the poster will travel (the thicker the poster, the more robust).

Laminating the poster adds an extra protective layer to it, consequently increasing its lifespan, making it much more resistant to water but also making it costlier and weightier to transport.

It is advisable to print out a mock-up version (A3 or A4) to look for any design issues, typing errors, and alignment concerns before investing in the final version of your poster.

Now that your poster is ready, you can prepare to discuss it with others. Come up with a brief oral presentation you can recite on the day, increasing your confidence in the conference presentation.

Once you get there, just be calm and enjoy the experience. And if you are interested in networking or sharing your results with the conference audience, you should consider preparing A4 flyers for your poster.

Tips to Make the Best Poster Presentation

There are various poster pitfalls that you should avoid when making a poster. Some, like avoiding including too much detail or too many images, are a no-brainer. Let?s look at some of the best practices you should consider when making a poster to present your project, capstone, or dissertation.

- Avoid unnecessary clutter. Restrict your presentation to a few important ideas. Note that presenting a few of your findings well is better than presenting all your findings badly. Arrange the contents of your poster to read from top to bottom and left to right. Frames, lines, and boxes should emphasize the most important points.

- Use simple lettering. Do not make us of more than three different font sizes; the smallest for text, the medium for section titles, and the largest for the title of the poster. Your smallest font size should be big enough to be read from a distance (24-point font). And for all your lettering, utilize bother lower- and uppercase letters, as words made up of uppercase letters only are hard to read.

- Use simple colors. Using many colors can be somewhat distracting, while using too little tends to be boring. Make use of color only when emphasizing the most vital elements.

- Avoid overly long titles. A good title is brief, snappy, and straight to the point. Some great titles ask questions, while others answer them. The title should highlight the subject matter and be big enough to be easily read from a distance, say 30 feet away. Also, the title should not surpass the width of the poster area and should not be entirely in capital letters.

- Include your names. The names of the authors involved, together with their institutional affiliations, should be included below the title. When doing so, do not use a similar font size as that used for the title; instead, use a smaller font.

- Never use a small font size for your poster. Avoid using 10-point or 12-point font sizes. Instead, use a font size that can be easily read from a distance of around 4 feet. You want your poster to be easily readable from a distance, don?t you? What?s more, avoid those fonts that are difficult to read, such as Linotext or Helvetica.

- Lay out the segments of your poster in a logical manner. This will allow reading to proceed linearly. You do not want your readers to have difficulty following your presentation. The best layout to use is the columnar format. This way, the readers proceed vertically from top to bottom and then from left to right.

- Divide your poster into sections to avoid one long, unending thread. All sections should be well-labeled with relevant titles. Aim to convey your message in a few words and diagrams, as your readers will not spend more than 3 minutes on your poster.

- Remember that a poster is not a scientific paper, and d o not waste a lot of precious space on irrelevant experimental details. The main areas to emphasize in your poster are the key results, experimental strategies, and the drawn conclusions.

- Do not forget to include the acknowledgments. You should give credit where it is due. Include a brief acknowledgment section thanking everyone who assisted you in completing the work. Also, include academic references where necessary. Note that your references should be as thorough as those in academic papers. You can also include footnotes, but avoid them if possible.

Final Thoughts on Abstract Posters

An abstract poster is a complex thing but the easiest of all to design when you have a structured approach. It may not be part of your research, but it is vital to communicate what you did to the world at the end of your research. As a re-cap, an effective poster should at least meet the following criteria:

- Have listicles as needed;

- Have brief text;

- Include headings and subheadings;

- Sparring use of images (only include 3-4 images);

- Include whitespace for ease of reading;

- Have a brief title;

- Clear and logical layout; and

- Interpretable text and images.

An effective poster presentation will help your readers understand your main points. Less is more when making a poster. Therefore, ensure you have adequate white space to improve its readability. At the same time, use colors and images sparingly.

If you are given a poster template from class, ensure that you use it because it has a predefined format that can help you actualize your professor's expectations. With the structure and the steps for preparing a poster abstract, we are confident you can make an outstanding one. Feel free to apply the tips to compose a brilliant presentation poster.

If you feel like you need any assistance to prepare an abstract poster, hit us up. Go to our home page and make an order for your poster. Our nurse writing expert will take up your order and deliver an abstract poster ASAP. It will be original, compact, and with zero errors.

Our per-page prices are affordable, and we do not charge extra for revisions.

Related Readings:

- Capstone project Ideas and Topics.

Struggling with

Related Articles

Evidence-Based Practice Nursing Research Paper Guide

Writing a Nursing Research Paper that Meets Professor's Requirements

Nursing Research Methodology Guide

NurseMyGrades is being relied upon by thousands of students worldwide to ace their nursing studies. We offer high quality sample papers that help students in their revision as well as helping them remain abreast of what is expected of them.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

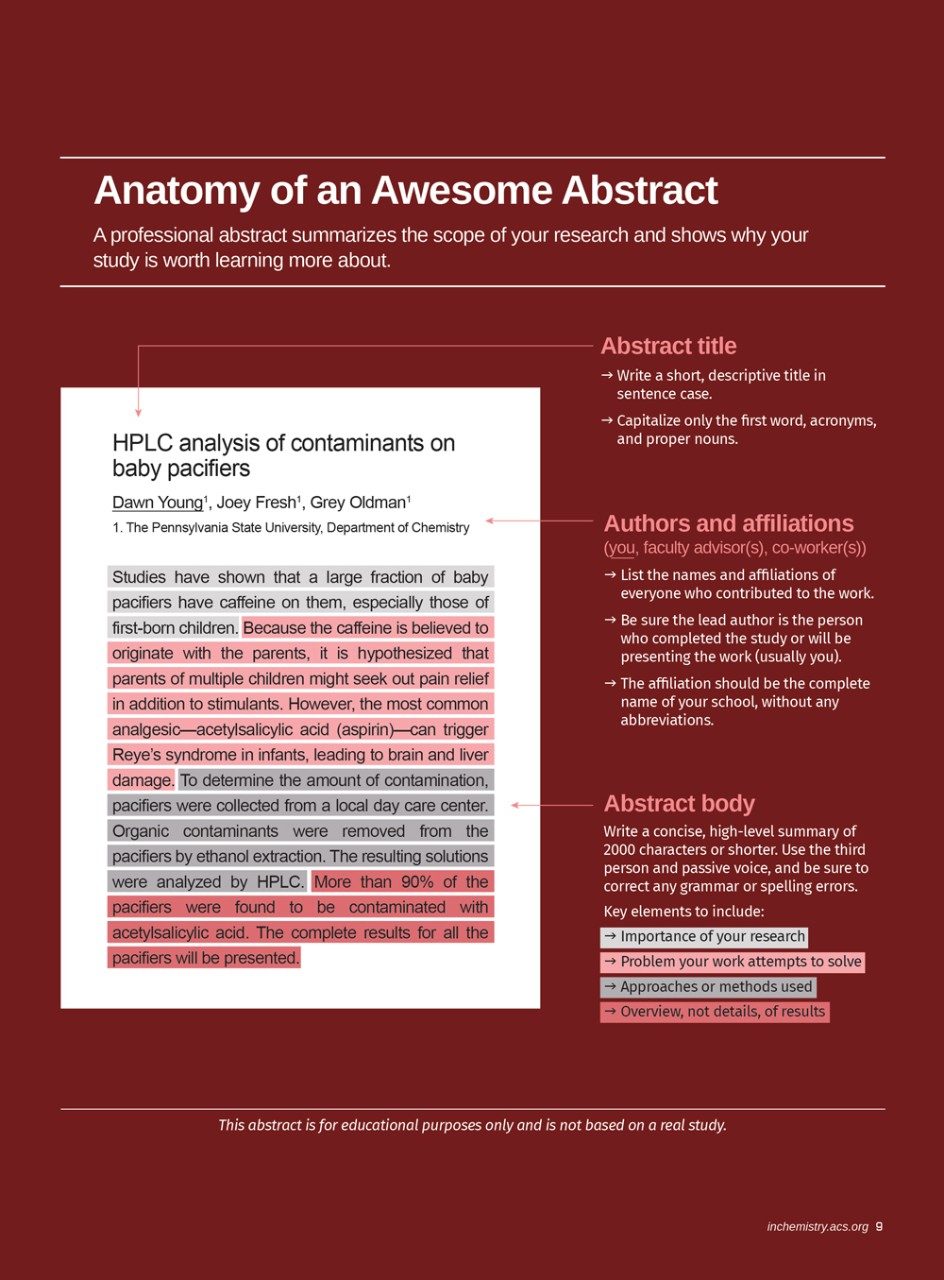

Characteristics of An Abstract

- One paragraph of text, typically 200-300 words long.

- A summary of the entire poster.

- Organized into four distinct sections that appear in order: Introduction, Materials & Methods, Results, Discussion.

- Each section typically consists of 2-4 sentences.

- No tables and no figures.

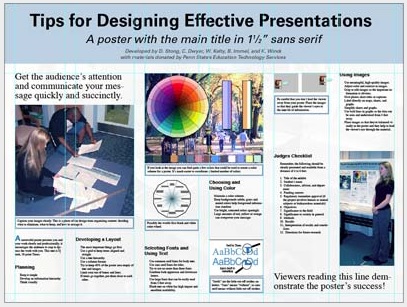

The abstract is a paragraph of text that appears at the top-left side of the poster ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). It is a summary of the entire poster. It should stand alone such that a person can read the abstract and understand all the research described in the poster. An abstract ( Fig. 3 ) contains four parts that should be written in the following order: Introduction, Materials & Methods, Results and Discussion. Each part typically consists of 2-4 sentences and the entire abstract will contain 200-300 words. An abstract consists strictly of text, it contains no figures, no tables, and typically it does not contain citations.

Figure 3. Abstract

Scientific Posters: A Learner's Guide Copyright © 2020 by Ella Weaver; Kylienne A. Shaul; Henry Griffy; and Brian H. Lower is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Home Blog Design How to Design a Winning Poster Presentation: Quick Guide with Examples & Templates

How to Design a Winning Poster Presentation: Quick Guide with Examples & Templates

How are research posters like High School science fair projects? Quite similar, in fact.

Both are visual representations of a research project shared with peers, colleagues and academic faculty. But there’s a big difference: it’s all in professionalism and attention to detail. You can be sure that the students that thrived in science fairs are now creating fantastic research posters, but what is that extra element most people miss when designing a poster presentation?

This guide will teach tips and tricks for creating poster presentations for conferences, symposia, and more. Learn in-depth poster structure and design techniques to help create academic posters that have a lasting impact.

Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

- What is a Research Poster?

Why are Poster Presentations important?

Overall dimensions and orientation, separation into columns and sections, scientific, academic, or something else, a handout with supplemental and contact information, cohesiveness, design and readability, storytelling.

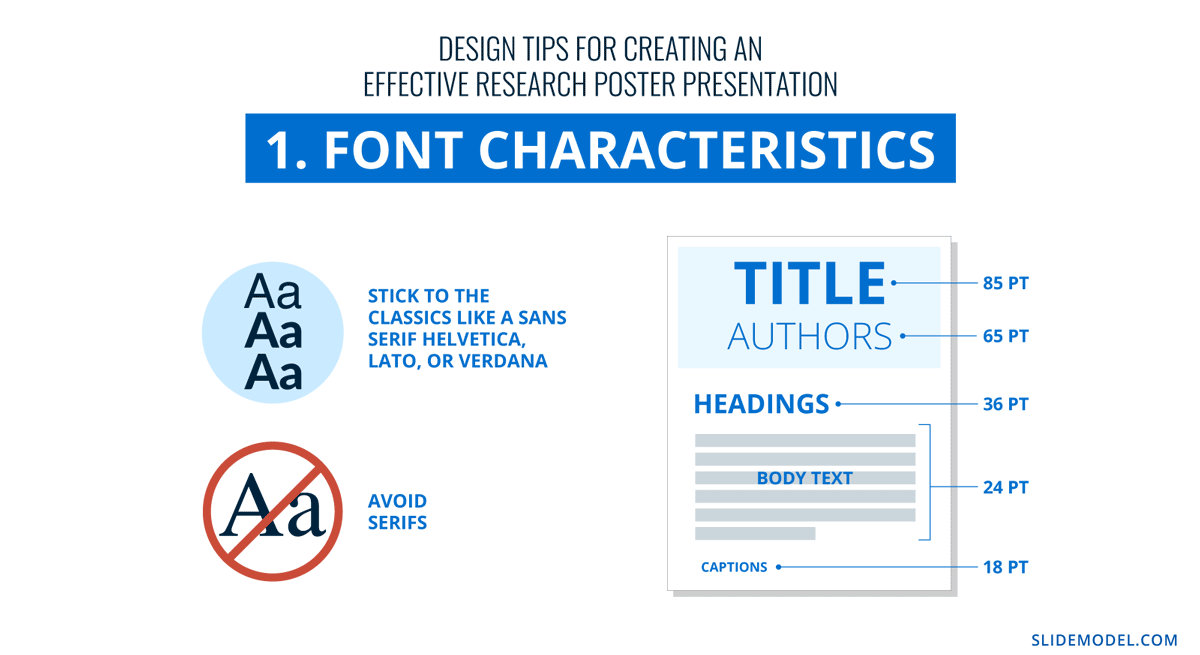

- Font Characteristics

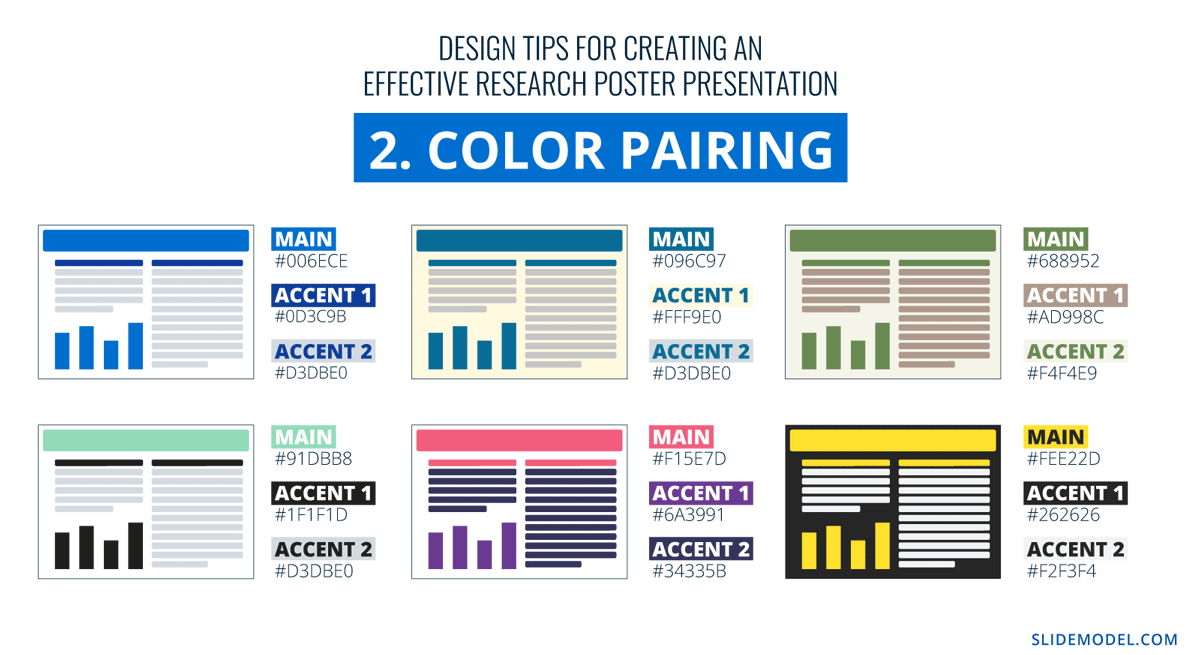

- Color Pairing

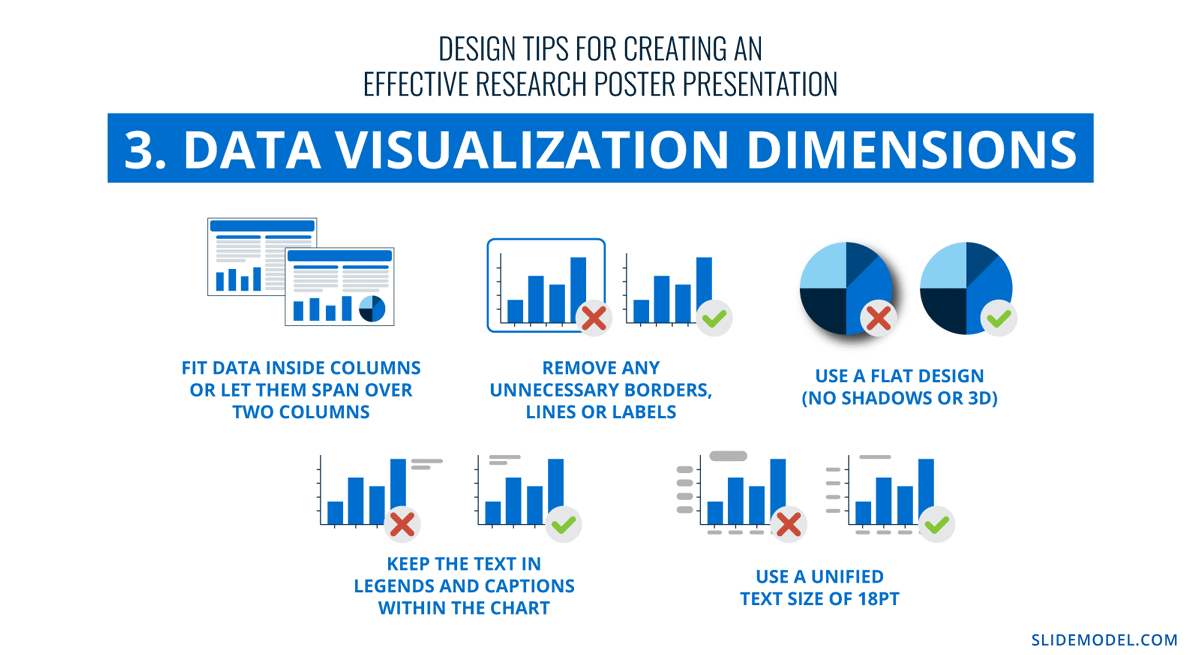

- Data Visualization Dimensions

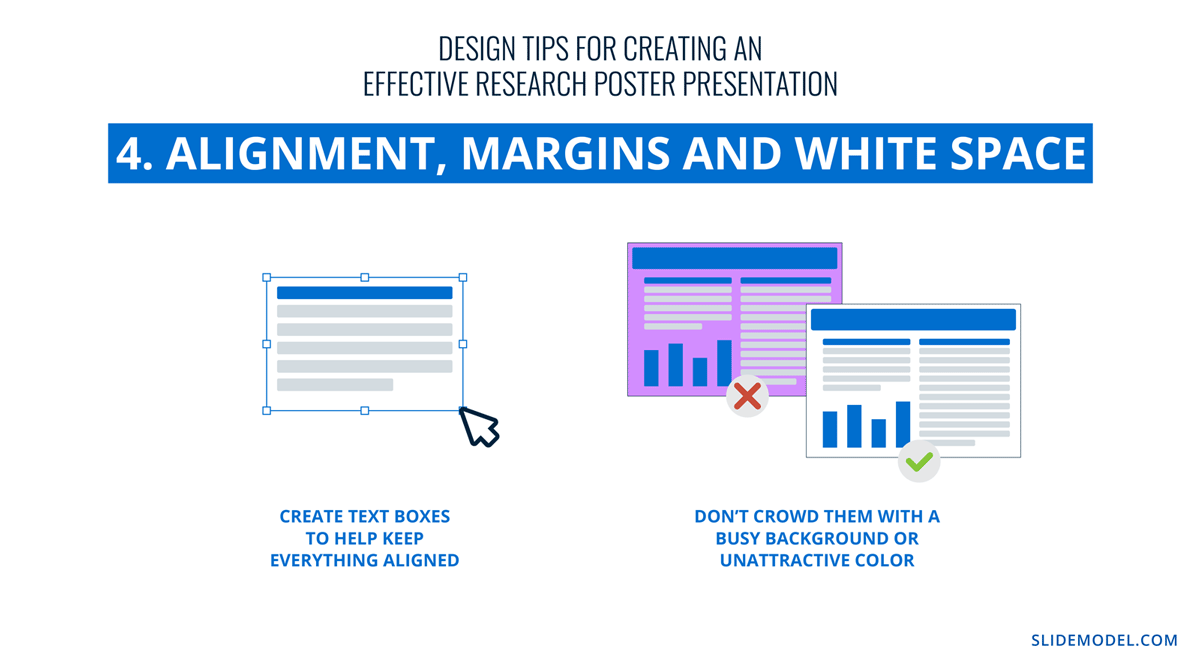

- Alignment, Margins, and White Space

Scientific/Academic Conference Poster Presentation

Digital research poster presentations, slidemodel poster presentation templates, how to make a research poster presentation step-by-step, considerations for printing poster presentations, how to present a research poster presentation, final words, what is a research poster .

Research posters are visual overviews of the most relevant information extracted from a research paper or analysis. They are essential communication formats for sharing findings with peers and interested people in the field. Research posters can also effectively present material for other areas besides the sciences and STEM—for example, business and law.

You’ll be creating research posters regularly as an academic researcher, scientist, or grad student. You’ll have to present them at numerous functions and events. For example:

- Conference presentations

- Informational events

- Community centers

The research poster presentation is a comprehensive way to share data, information, and research results. Before the pandemic, the majority of research events were in person. During lockdown and beyond, virtual conferences and summits became the norm. Many researchers now create poster presentations that work in printed and digital formats.

Let’s look at why it’s crucial to spend time creating poster presentations for your research projects, research, analysis, and study papers.

Research posters represent you and your sponsor’s research

Research papers and accompanying poster presentations are potent tools for representation and communication in your field of study. Well-performing poster presentations help scientists, researchers, and analysts grow their careers through grants and sponsorships.

When presenting a poster presentation for a sponsored research project, you’re representing the company that sponsored you. Your professionalism, demeanor, and capacity for creating impactful poster presentations call attention to other interested sponsors, spreading your impact in the field.

Research posters demonstrate expertise and growth

Presenting research posters at conferences, summits, and graduate grading events shows your expertise and knowledge in your field of study. The way your poster presentation looks and delivers, plus your performance while presenting the work, is judged by your viewers regardless of whether it’s an officially judged panel.

Recurring visitors to research conferences and symposia will see you and your poster presentations evolve. Improve your impact by creating a great poster presentation every time by paying attention to detail in the poster design and in your oral presentation. Practice your public speaking skills alongside the design techniques for even more impact.

Poster presentations create and maintain collaborations

Every time you participate in a research poster conference, you create meaningful connections with people in your field, industry or community. Not only do research posters showcase information about current data in different areas, but they also bring people together with similar interests. Countless collaboration projects between different research teams started after discussing poster details during coffee breaks.

An effective research poster template deepens your peer’s understanding of a topic by highlighting research, data, and conclusions. This information can help other researchers and analysts with their work. As a research poster presenter, you’re given the opportunity for both teaching and learning while sharing ideas with peers and colleagues.

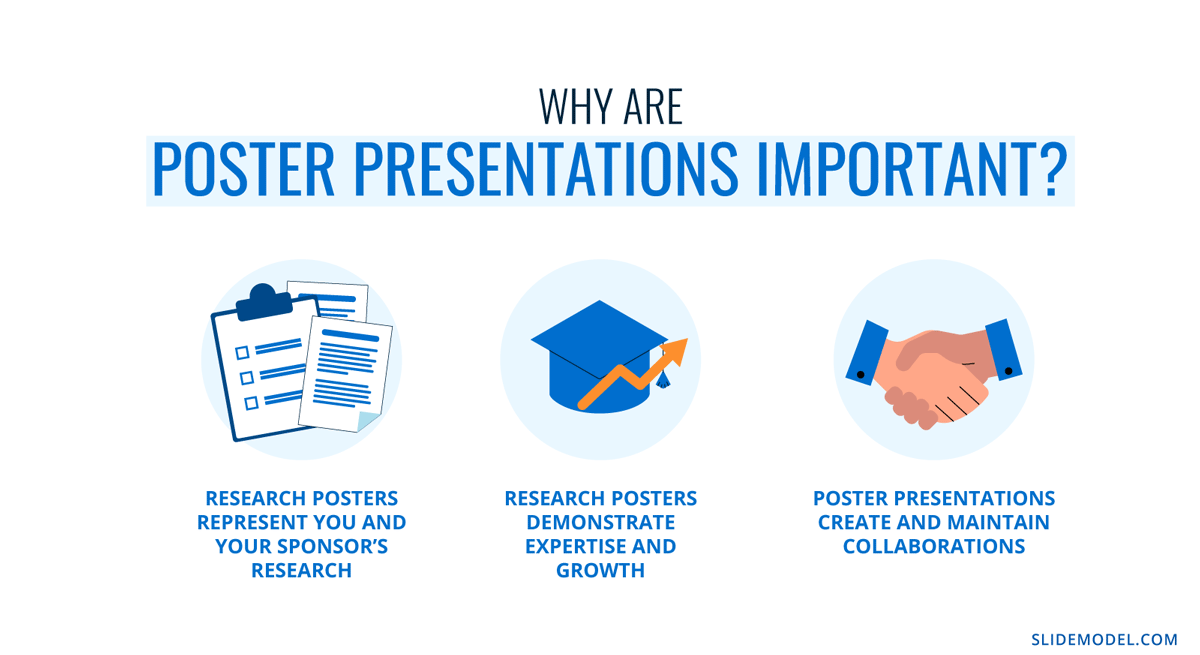

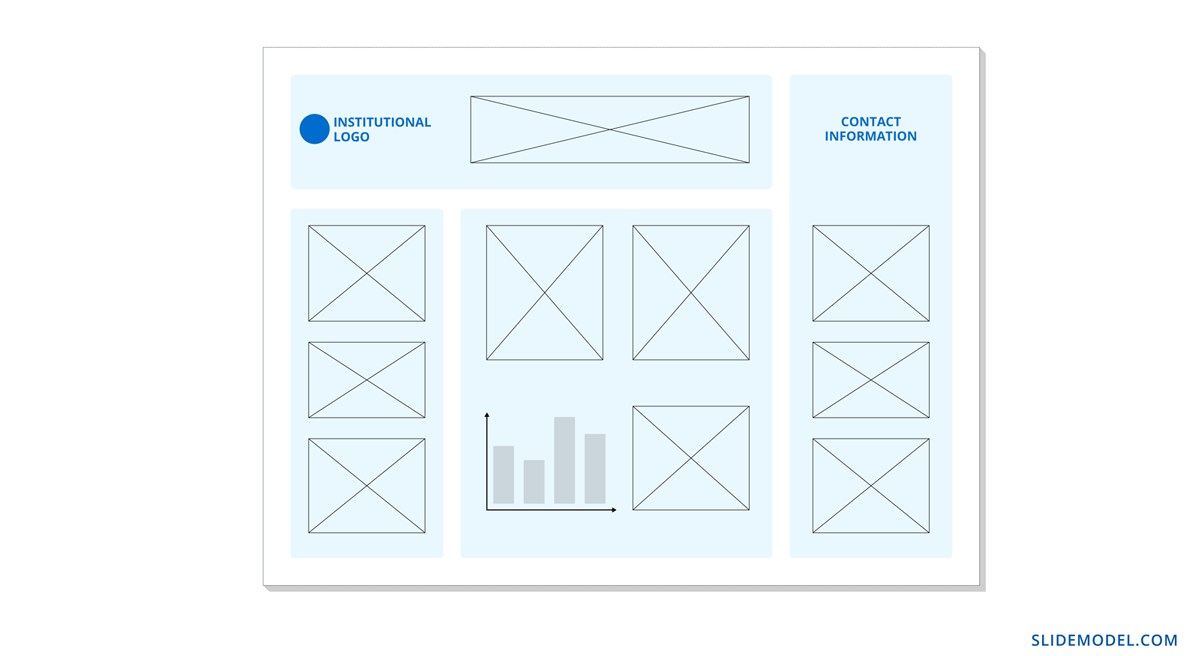

Anatomy of a Winning Poster Presentation

Do you want your research poster to perform well? Following the standard layout and adding a few personal touches will help attendees know how to read your poster and get the most out of your information.

The overall size of your research poster ultimately depends on the dimensions of the provided space at the conference or research poster gallery. The poster orientation can be horizontal or vertical, with horizontal being the most common. In general, research posters measure 48 x 36 inches or are an A0 paper size.

A virtual poster can be the same proportions as the printed research poster, but you have more leeway regarding the dimensions. Virtual research posters should fit on a screen with no need to scroll, with 1080p resolution as a standard these days. A horizontal presentation size is ideal for that.

A research poster presentation has a standard layout of 2–5 columns with 2–3 sections each. Typical structures say to separate the content into four sections; 1. A horizontal header 2. Introduction column, 3. Research/Work/Data column, and 4. Conclusion column. Each unit includes topics that relate to your poster’s objective. Here’s a generalized outline for a poster presentation:

- Condensed Abstract

- Objectives/Purpose

- Methodology

- Recommendations

- Implications

- Acknowledgments

- Contact Information

The overview content you include in the units depends on your poster presentations’ theme, topic, industry, or field of research. A scientific or academic poster will include sections like hypothesis, methodology, and materials. A marketing analysis poster will include performance metrics and competitor analysis results.

There’s no way a poster can hold all the information included in your research paper or analysis report. The poster is an overview that invites the audience to want to find out more. That’s where supplement material comes in. Create a printed PDF handout or card with a QR code (created using a QR code generator ). Send the audience to the best online location for reading or downloading the complete paper.

What Makes a Poster Presentation Good and Effective?

For your poster presentation to be effective and well-received, it needs to cover all the bases and be inviting to find out more. Stick to the standard layout suggestions and give it a unique look and feel. We’ve put together some of the most critical research poster-creation tips in the list below. Your poster presentation will perform as long as you check all the boxes.

The information you choose to include in the sections of your poster presentation needs to be cohesive. Train your editing eye and do a few revisions before presenting. The best way to look at it is to think of The Big Picture. Don’t get stuck on the details; your attendees won’t always know the background behind your research topic or why it’s important.

Be cohesive in how you word the titles, the length of the sections, the highlighting of the most important data, and how your oral presentation complements the printed—or virtual—poster.

The most important characteristic of your poster presentation is its readability and clarity. You need a poster presentation with a balanced design that’s easy to read at a distance of 1.5 meters or 4 feet. The font size and spacing must be clear and neat. All the content must suggest a visual flow for the viewer to follow.

That said, you don’t need to be a designer to add something special to your poster presentation. Once you have the standard—and recognized—columns and sections, add your special touch. These can be anything from colorful boxes for the section titles to an interesting but subtle background, images that catch the eye, and charts that inspire a more extended look.

Storytelling is a presenting technique involving writing techniques to make information flow. Firstly, storytelling helps give your poster presentation a great introduction and an impactful conclusion.

Think of storytelling as the invitation to listen or read more, as the glue that connects sections, making them flow from one to another. Storytelling is using stories in the oral presentation, for example, what your lab partner said when you discovered something interesting. If it makes your audience smile and nod, you’ve hit the mark. Storytelling is like giving a research presentation a dose of your personality, and it can help turning your data into opening stories .

Design Tips For Creating an Effective Research Poster Presentation

The section above briefly mentioned how important design is to your poster presentation’s effectiveness. We’ll look deeper into what you need to know when designing a poster presentation.

1. Font Characteristics

The typeface and size you choose are of great importance. Not only does the text need to be readable from two meters away, but it also needs to look and sit well on the poster. Stay away from calligraphic script typefaces, novelty typefaces, or typefaces with uniquely shaped letters.

Stick to the classics like a sans serif Helvetica, Lato, Open Sans, or Verdana. Avoid serif typefaces as they can be difficult to read from far away. Here are some standard text sizes to have on hand.

- Title: 85 pt

- Authors: 65 pt

- Headings: 36 pt

- Body Text: 24 pt

- Captions: 18 pt

If you feel too prone to use serif typefaces, work with a font pairing tool that helps you find a suitable solution – and intend those serif fonts for heading sections only. As a rule, never use more than 3 different typefaces in your design. To make it more dynamic, you can work with the same font using light, bold, and italic weights to put emphasis on the required areas.

2. Color Pairing

Using colors in your poster presentation design is a great way to grab the viewer’s attention. A color’s purpose is to help the viewer follow the data flow in your presentation, not distract. Don’t let the color take more importance than the information on your poster.

Choose one main color for the title and headlines and a similar color for the data visualizations. If you want to use more than one color, don’t create too much contrast between them. Try different tonalities of the same color and keep things balanced visually. Your color palette should have at most one main color and two accent colors.

Black text over a white background is standard practice for printed poster presentations, but for virtual presentations, try a very light gray instead of white and a very dark gray instead of black. Additionally, use variations of light color backgrounds and dark color text. Make sure it’s easy to read from two meters away or on a screen, depending on the context. We recommend ditching full white or full black tone usage as it hurts eyesight in the long term due to its intense contrast difference with the light ambiance.

3. Data Visualization Dimensions

Just like the text, your charts, graphs, and data visualizations must be easy to read and understand. Generally, if a person is interested in your research and has already read some of the text from two meters away, they’ll come closer to look at the charts and graphs.

Fit data visualizations inside columns or let them span over two columns. Remove any unnecessary borders, lines, or labels to make them easier to read at a glance. Use a flat design without shadows or 3D characteristics. The text in legends and captions should stay within the chart size and not overflow into the margins. Use a unified text size of 18px for all your data visualizations.

4. Alignment, Margins, and White Space

Finally, the last design tip for creating an impressive and memorable poster presentation is to be mindful of the layout’s alignment, margins, and white space. Create text boxes to help keep everything aligned. They allow you to resize, adapt, and align the content along a margin or grid.

Take advantage of the white space created by borders and margins between sections. Don’t crowd them with a busy background or unattractive color.

Calculate margins considering a print format. It is a good practice in case the poster presentation ends up becoming in physical format, as you won’t need to downscale your entire design (affecting text readability in the process) to preserve information.

There are different tools that you can use to make a poster presentation. Presenters who are familiar with Microsoft Office prefer to use PowerPoint. You can learn how to make a poster in PowerPoint here.

Poster Presentation Examples

Before you start creating a poster presentation, look at some examples of real research posters. Get inspired and get creative.

Research poster presentations printed and mounted on a board look like the one in the image below. The presenter stands to the side, ready to share the information with visitors as they walk up to the panels.

With more and more conferences staying virtual or hybrid, the digital poster presentation is here to stay. Take a look at examples from a poster session at the OHSU School of Medicine .

Use SlideModel templates to help you create a winning poster presentation with PowerPoint and Google Slides. These poster PPT templates will get you off on the right foot. Mix and match tables and data visualizations from other poster slide templates to create your ideal layout according to the standard guidelines.

If you need a quick method to create a presentation deck to talk about your research poster at conferences, check out our Slides AI presentation maker. A tool in which you add the topic, curate the outline, select a design, and let AI do the work for you.

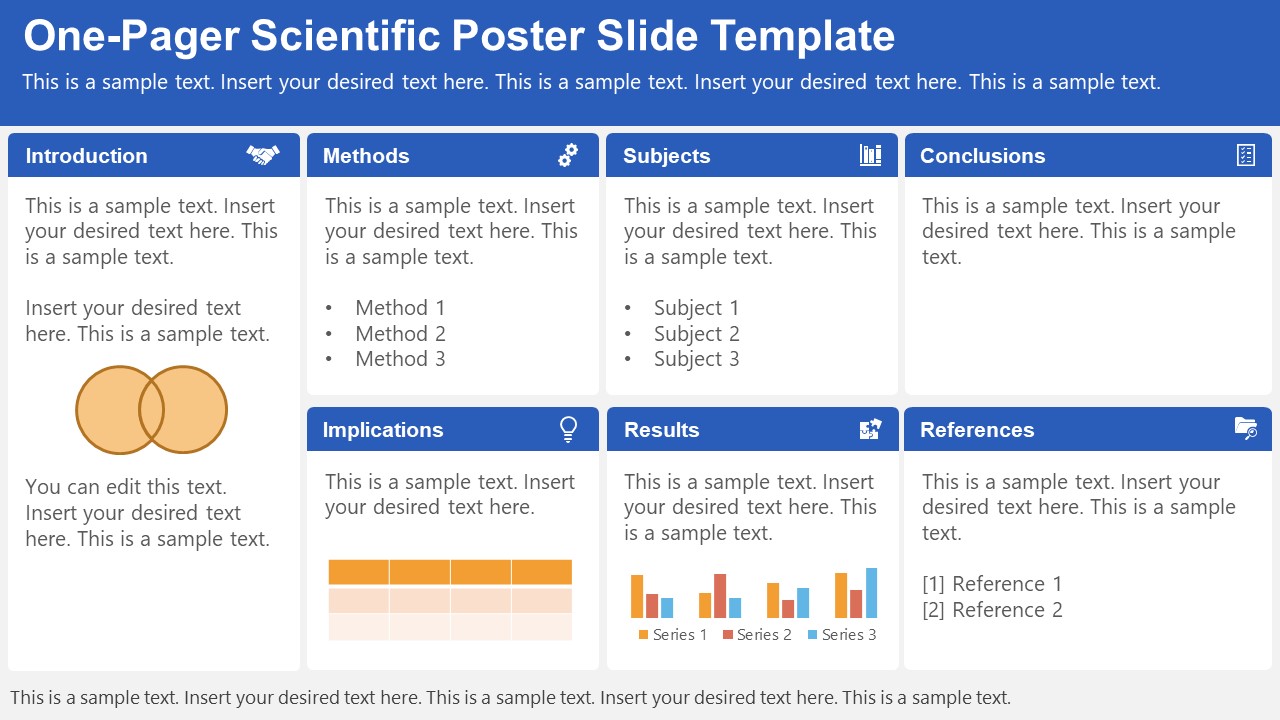

1. One-pager Scientific Poster Template for PowerPoint

A PowerPoint template tailored to make your poster presentations an easy-to-craft process. Meet our One-Pager Scientific Poster Slide Template, entirely editable to your preferences and with ample room to accommodate graphs, data charts, and much more.

Use This Template

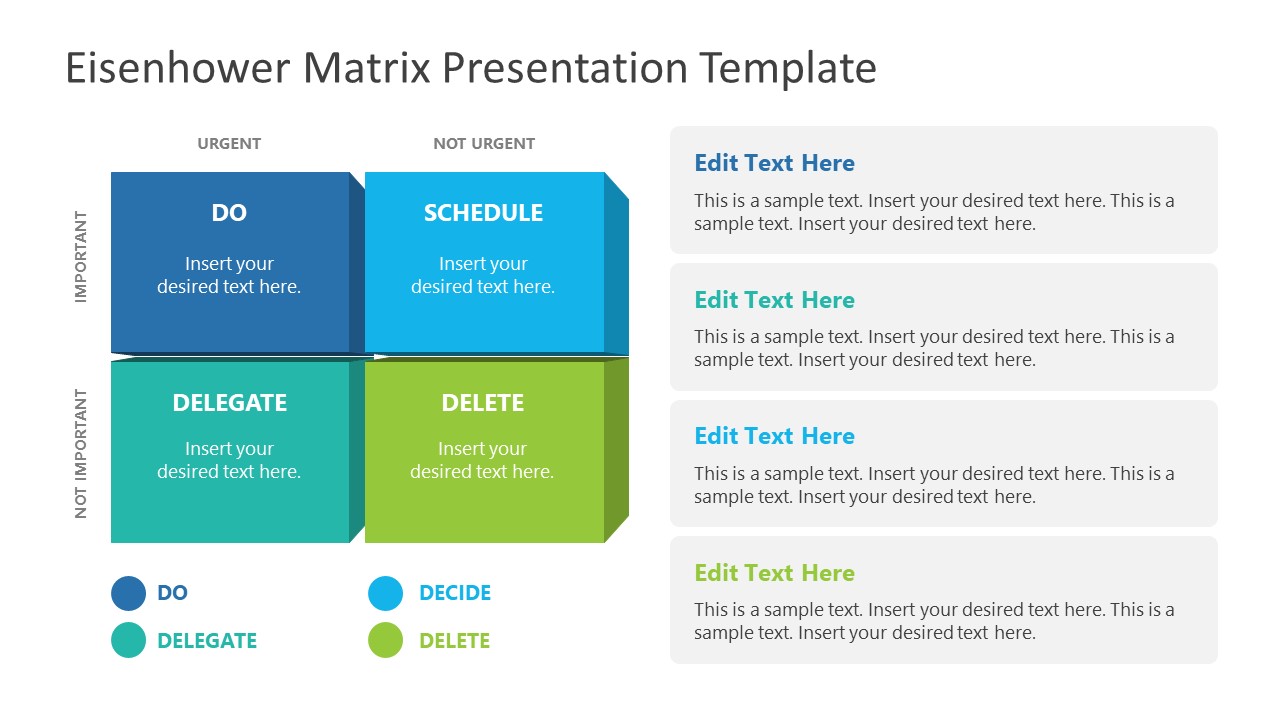

2. Eisenhower Matrix Slides Template for PowerPoint

An Eisenhower Matrix is a powerful tool to represent priorities, classifying work according to urgency and importance. Presenters can use this 2×2 matrix in poster presentations to expose the effort required for the research process, as it also helps to communicate strategy planning.

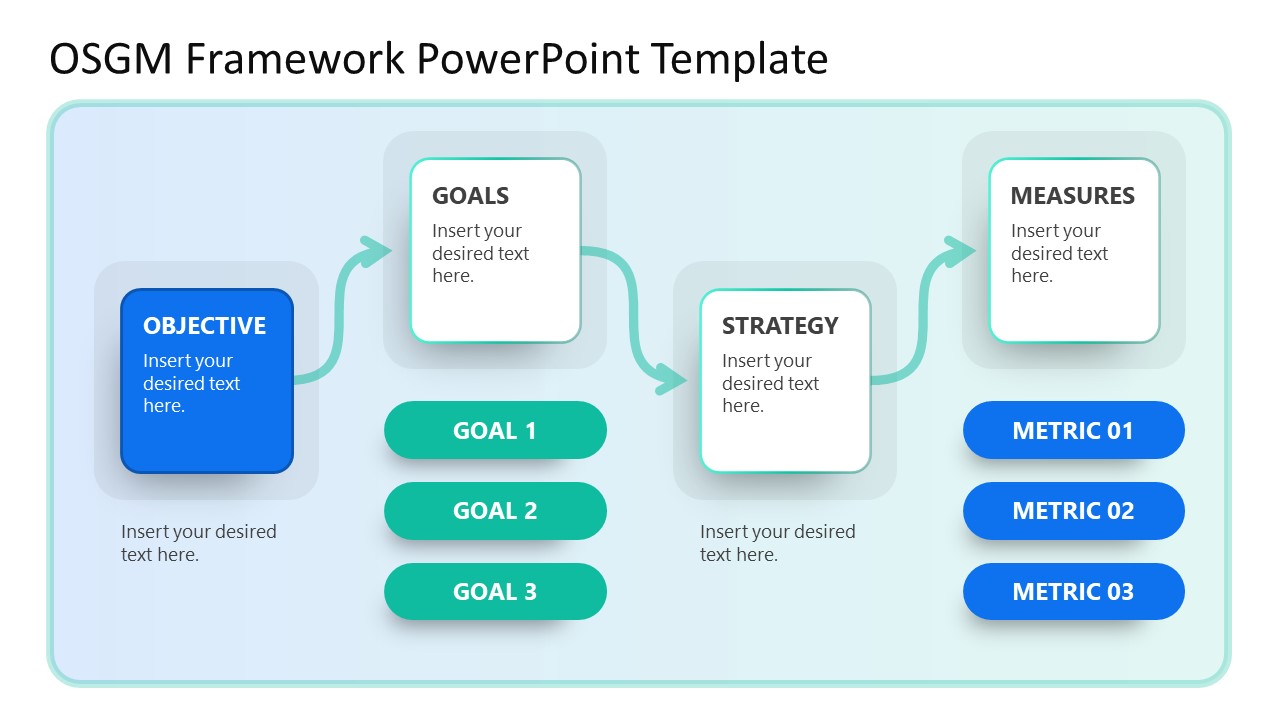

3. OSMG Framework PowerPoint Template

Finally, we recommend presenters check our OSMG Framework PowerPoint template, as it is an ideal tool for representing a business plan: its goals, strategies, and measures for success. Expose complex processes in a simplified manner by adding this template to your poster presentation.

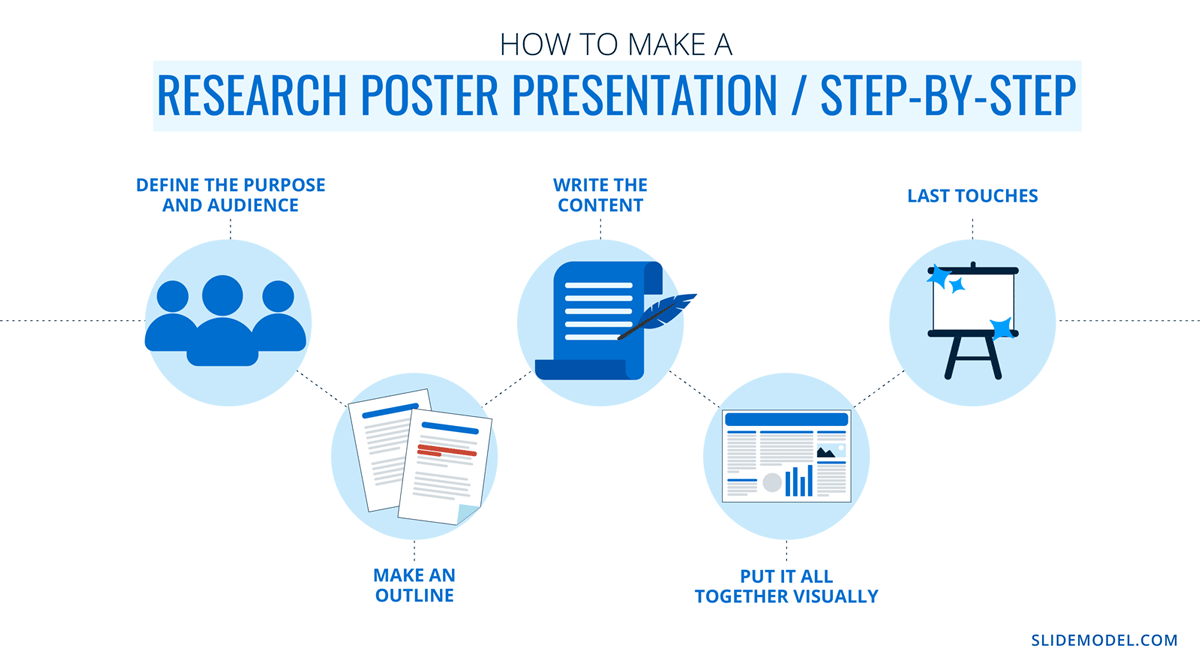

Remember these three words when making your research poster presentation: develop, design, and present. These are the three main actions toward a successful poster presentation.

The section below will take you on a step-by-step journey to create your next poster presentation.

Step 1: Define the purpose and audience of your poster presentation

Before making a poster presentation design, you’ll need to plan first. Here are some questions to answer at this point:

- Are they in your field?

- Do they know about your research topic?

- What can they get from your research?

- Will you print it?

- Is it for a virtual conference?

Step 2: Make an outline

With a clear purpose and strategy, it’s time to collect the most important information from your research paper, analysis, or documentation. Make a content dump and then select the most interesting information. Use the content to draft an outline.

Outlines help formulate the overall structure better than going straight into designing the poster. Mimic the standard poster structure in your outline using section headlines as separators. Go further and separate the content into the columns they’ll be placed in.

Step 3: Write the content

Write or rewrite the content for the sections in your poster presentation. Use the text in your research paper as a base, but summarize it to be more succinct in what you share.

Don’t forget to write a catchy title that presents the problem and your findings in a clear way. Likewise, craft the headlines for the sections in a similar tone as the title, creating consistency in the message. Include subtle transitions between sections to help follow the flow of information in order.

Avoid copying/pasting entire sections of the research paper on which the poster is based. Opt for the storytelling approach, so the delivered message results are interesting for your audience.

Step 4: Put it all together visually

This entire guide on how to design a research poster presentation is the perfect resource to help you with this step. Follow all the tips and guidelines and have an unforgettable poster presentation.

Moving on, here’s how to design a research poster presentation with PowerPoint Templates . Open a new project and size it to the standard 48 x 36 inches. Using the outline, map out the sections on the empty canvas. Add a text box for each title, headline, and body text. Piece by piece, add the content into their corresponding text box.

Transform the text information visually, make bullet points, and place the content in tables and timelines. Make your text visual to avoid chunky text blocks that no one will have time to read. Make sure all text sizes are coherent for all headings, body texts, image captions, etc. Double-check for spacing and text box formatting.

Next, add or create data visualizations, images, or diagrams. Align everything into columns and sections, making sure there’s no overflow. Add captions and legends to the visualizations, and check the color contrast with colleagues and friends. Ask for feedback and progress to the last step.

Step 5: Last touches

Time to check the final touches on your poster presentation design. Here’s a checklist to help finalize your research poster before sending it to printers or the virtual summit rep.

- Check the resolution of all visual elements in your poster design. Zoom to 100 or 200% to see if the images pixelate. Avoid this problem by using vector design elements and high-resolution images.

- Ensure that charts and graphs are easy to read and don’t look crowded.

- Analyze the visual hierarchy. Is there a visual flow through the title, introduction, data, and conclusion?

- Take a step back and check if it’s legible from a distance. Is there enough white space for the content to breathe?

- Does the design look inviting and interesting?

An often neglected topic arises when we need to print our designs for any exhibition purpose. Since A0 is a hard-to-manage format for most printers, these poster presentations result in heftier charges for the user. Instead, you can opt to work your design in two A1 sheets, which also becomes more manageable for transportation. Create seamless borders for the section on which the poster sheets should meet, or work with a white background.

Paper weight options should be over 200 gsm to avoid unwanted damage during the printing process due to heavy ink usage. If possible, laminate your print or stick it to photographic paper – this shall protect your work from spills.

Finally, always run a test print. Gray tints may not be printed as clearly as you see them on screen (this is due to the RGB to CMYK conversion process). Other differences can be appreciated when working with ink jet plotters vs. laser printers. Give yourself enough room to maneuver last-minute design changes.

Presenting a research poster is a big step in the poster presentation cycle. Your poster presentation might or might not be judged by faculty or peers. But knowing what judges look for will help you prepare for the design and oral presentation, regardless of whether you receive a grade for your work or if it’s business related. Likewise, the same principles apply when presenting at an in-person or virtual summit.

The opening statement

Part of presenting a research poster is welcoming the viewer to your small personal area in the sea of poster presentations. You’ll need an opening statement to pitch your research poster and get the viewers’ attention.

Draft a 2 to 3-sentence pitch that covers the most important points:

- What the research is

- Why was it conducted

- What the results say

From that opening statement, you’re ready to continue with the oral presentation for the benefit of your attendees.

The oral presentation

During the oral presentation, share the information on the poster while conversing with the interested public. Practice many times before the event. Structure the oral presentation as conversation points, and use the poster’s visual flow as support. Make eye contact with your audience as you speak, but don’t make them uncomfortable.

Pro Tip: In a conference or summit, if people show up to your poster area after you’ve started presenting it to another group, finish and then address the new visitors.

QA Sessions

When you’ve finished the oral presentation, offer the audience a chance to ask questions. You can tell them before starting the presentation that you’ll be holding a QA session at the end. Doing so will prevent interruptions as you’re speaking.

If presenting to one or two people, be flexible and answer questions as you review all the sections on your poster.

Supplemental Material

If your audience is interested in learning more, you can offer another content type, further imprinting the information in their minds. Some ideas include; printed copies of your research paper, links to a website, a digital experience of your poster, a thesis PDF, or data spreadsheets.

Your audience will want to contact you for further conversations; include contact details in your supplemental material. If you don’t offer anything else, at least have business cards.

Even though conferences have changed, the research poster’s importance hasn’t diminished. Now, instead of simply creating a printed poster presentation, you can also make it for digital platforms. The final output will depend on the conference and its requirements.

This guide covered all the essential information you need to know for creating impactful poster presentations, from design, structure and layout tips to oral presentation techniques to engage your audience better .

Before your next poster session, bookmark and review this guide to help you design a winning poster presentation every time.

Like this article? Please share

Cool Presentation Ideas, Design, Design Inspiration Filed under Design

Related Articles

Filed under Design • January 11th, 2024

How to Use Figma for Presentations

The powerful UI/UX prototyping software can also help us to craft high-end presentation slides. Learn how to use Figma as a presentation software here!

Filed under Design • December 28th, 2023

Multimedia Presentation: Insights & Techniques to Maximize Engagement

Harnessing the power of multimedia presentation is vital for speakers nowadays. Join us to discover how you can utilize these strategies in your work.

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • December 15th, 2023

How to Delete a Text Box in Google Slides

Discover how to delete a text box in Google Slides in just a couple of clicks. Step-by-step guide with images.

Leave a Reply

How to Create an Academic Poster

- Designing Effective Research Posters

- Poster Templates

- Poster Printing Guidelines

How to Write a Poster Abstract or Proposal

- More Research Help

Little Memorial Library Printing Guidelines

How to print a poster:.

- Submit your poster print request here: https://midway.libwizard.com/f/posterprinting

- Submit your poster print request at least one week in advance of when you need it

- Go to the Business Office in LRC and pay for the poster (You may also call them at 859-846-5402 .)

- Wait for an email from The Center@Midway telling you to come pick up your poster

Printing specifications:

- Make your poster 36" x 48".

- Save your poster as a PDF. Only PDF files will be accepted.

- Use at least 300 dpi (but no more than 1200 dpi)

- File size should be no more than 10MB

- Poster must be school/study-related.

- Cost: $20 per poster (you will incur an additional $20 charge every time you want your poster re-printed because of a typo, wanting to change information, etc.).

- Poster Abstracts

What is an abstract/proposal and why should I write one?

If you want to submit your paper/research at a conference, you must first write a proposal. A poster proposal tells the conference committee what your poster is about and, depending on the conference guidelines, might include a poster abstract, your list of contributors, and/or presentation needs.

The poster abstract is the most important part of your proposal. It is a summary of your research poster, and tells the reader what your problem, method, results, and conclusions are. Most abstracts are only 75 -- 250 words long.

- << Previous: Poster Printing Guidelines

- Next: More Research Help >>

- Last Updated: Mar 23, 2021 11:17 AM

- URL: https://midway.libguides.com/AcademicPoster

RESEARCH HELP

- Research Guides

- Databases A-Z

- Journal Search

- Citation Help

LIBRARY SERVICES

- Accessibility

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

INSTRUCTION SUPPORT

- Course Reserves

- Library Instruction

- Little Memorial Library

- 512 East Stephens Street

- 859.846.5316

- [email protected]

- Latest Articles

- Clinical Practice

- ONS Leadership

- Get Involved

- Conferences

Best Practices for Abstract Writing and Presentation

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn

- Email Article

- Print Article

The development of an abstract, poster, or podium presentation is a significant undertaking. Presenting the scope of your work in a concise and effective way can be daunting, but it does not have to be. Erica Fischer-Cartlidge, MSN, CNS, CBCN ® , AOCNS ® , a clinical nurse specialist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, provided advice on abstract writing and presentation.

What Are the First Steps In Writing an Effective Abstract?

First, consider the conference goals and objectives to ensure that your research has a place there. If it’s a good fit, begin writing an abstract that clearly demonstrates the relevance of your presentation. Before starting this work, determine if your employer’s approval is needed for you to submit your research. Once approval is granted, gather all necessary information for a complete abstract.

Clearly identify your purpose, methods, findings, and discussion points for nursing implications. Identify all authors who contributed to your work, and include their names, credentials, and work settings. Determine if you are the project leader or facilitator, and include other coauthors, if applicable. In some cases, the number of coauthors who can be listed is limited by abstract guidelines.

It’s important to adhere to all abstract guidelines. Identify necessary sections, headers, and other formatting requirements, particularly word counts, as outlined by the selection committee. These can help you fill out the content of your abstract by acting as an outline. Work with coauthors to decide which parts of the research belong in each section. Selection committees will use scoring criteria to evaluate each abstract. Review them to guide you in selecting the right content for your abstract.

What Are Some Best Practices for Writing an Abstract?

Beyond including the required content and following formatting guidelines, incorporate other style considerations. Use abbreviations only when necessary and only after writing out the terminology on first reference. Present findings with data and statistics; leave speculations and conclusion for the discussion section. A good rule of thumb to follow is the mnemonic KISS : Keep It Short and Simple. Your reader should be left wanting, not wondering.

Write to express, not to impress. Your abstract will be clearer if participants always appear before verbs and you avoid passive voice (e.g., “we studied,” “patients reported”). And, of course, select an informative and dynamic title.

When finished, it helps to read your abstract aloud to get a sense flow and clarity, and to catch errors. Be sure to do a “human” check for spelling, grammar, and punctuation; don’t rely on spellcheck programs alone. Ask a friend or colleague to read your abstract draft to ensure that your work is clear and understandable. And, finally, score your abstract against the conference scoring criteria. How does it measure up?

Once the Abstract Is Accepted, How Is the Work Generally Presented?

You may present your work in three ways: poster, podium, or lecture. (Abstract submission guidelines may ask you to specify whether you are submitting for a podium or a poster.) Usually, the type of presentation is determined by relevance of the subject to the conference goals and the scoring during the review process. Lectureship is generally a separate process. Posters may be a standard paper poster, a moderated poster, or an electronic poster.

Moderated posters or electronic posters include a short (less than five minutes) verbal presentation of the project, in addition to the visual poster you create. Electronic posters involve the projection of the poster on a computer or television monitor instead of printing it on paper to hang for display.

Podium presentations are grouped by subject, and the sessions generally include three to five presenters who cover related topics. Each presenter typically has about 15 minutes to verbally present the work alongside accompanying slides.

What Are the Key Considerations in Developing and Executing a Presentation?

Review formatting guidelines before starting your work. Use institutional branding when appropriate. Be consistent with fonts, bullets, justification, indentation, and point size. Limit the use of all capitals and italics. The content and organization should mirror the sections of your abstract. When reporting data, find the best visual representation for the information you are sharing.

- Bar graphs show trends, similarity, or differences among groups of information.

- Line graphs demonstrate change over time for a group of data.

- Pie charts represent parts of a whole.

For podium sessions, your research will appear in a slide presentation. Slides should emphasize your verbal content—don’t simply read from them. For this reason, aim for slides to have no more than six lines of text, as more than this can crowd the slide and distract the audience from the content. In some cases, graphics and images can replace text on a slide to better engage the audience.

In formatting your content, simpler is better. Avoid complete sentences, and avoid abbreviations for terms that are not general knowledge to your audience. Finally, pay careful attention to correct presentation of schools, titles, degrees, and more. Make sure these are capitalized, accurate, and complete.

Posters require a slightly different approach. Again, be sure to read the criteria and follow the requirements closely. Before beginning, find out whether your institution has branded templates for conferences; your organization’s information technology, graphics, or public affairs departments may be able to help you with this. When designing the poster, minimize text and use bullets for key points. Avoid excess white space. Enhance your text with graphs, photos, and/or smart art. Variation in column sizes can help enhance the design of your poster.

What Tips Can You Give for Delivering the Presentation?

Dress to impress. Come prepared with business cards and any applicable handouts. Arrive early to assess your environment. Where is the slide show projected? How is the microphone set up?

Test the microphone and volume before the presentation start time.

While presenting, make eye contact with members of the audience. Do not simply read the content from your slides—remember, these are talking points only. When fielding audience questions, allow the question to be asked fully before answering. Rephrase the attendee’s question, and repeat it into the microphone for the other audience members. Avoid over answering, be diplomatic with controversy, and don’t misrepresent any information.

Editor’s Note: This interview was edited from materials presented by Erica Fischer-Cartlidge, MSN, CNS, CBCN ® , AOCNS ® , clinical nurse specialist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, at the 2017 ONS 42nd Annual Congress.

- nursing professional development

- ONS Congress

- Oncology nursing community

- Oncology nurse influence

How to Create a Research Poster

- Poster Basics

- Design Tips

- Logos & Images

What is a Research Poster?

Posters are widely used in the academic community, and most conferences include poster presentations in their program. Research posters summarize information or research concisely and attractively to help publicize it and generate discussion.

The poster is usually a mixture of a brief text mixed with tables, graphs, pictures, and other presentation formats. At a conference, the researcher stands by the poster display while other participants can come and view the presentation and interact with the author.

What Makes a Good Poster?

- Important information should be readable from about 10 feet away

- Title is short and draws interest

- Word count of about 300 to 800 words

- Text is clear and to the point

- Use of bullets, numbering, and headlines make it easy to read

- Effective use of graphics, color and fonts

- Consistent and clean layout

- Includes acknowledgments, your name and institutional affiliation

A Sample of a Well Designed Poster

View this poster example in a web browser .

Image credit: Poster Session Tips by [email protected], via Penn State

Where do I begin?

Answer these three questions:.

- What is the most important/interesting/astounding finding from my research project?

- How can I visually share my research with conference attendees? Should I use charts, graphs, photos, images?

- What kind of information can I convey during my talk that will complement my poster?

What software can I use to make a poster?

A popular, easy-to-use option. It is part of Microsoft Office package and is available on the library computers in rooms LC337 and LC336. ( Advice for creating a poster with PowerPoint ).

Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and InDesign

Feature-rich professional software that is good for posters including lots of high-resolution images, but they are more complex and expensive. NYU Faculty, Staff, and Students can access and download the Adobe Creative Suite .

Open Source Alternatives

- OpenOffice is the free alternative to MS Office (Impress is its PowerPoint alternative).

- Inkscape and Gimp are alternatives to Adobe products.

- For charts and diagrams try Gliffy or Lovely Charts .

- A complete list of free graphics software .

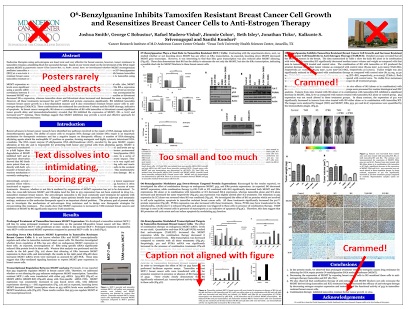

A Sample of a Poorly Designed Poster

View this bad poster example in a browser.

Image Credit: Critique by Better Posters

- Next: Design Tips >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2023 5:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/posters

NCURA.edu | Contact Us |

- Registration Pricing

- Bulk Registration Packages

- Conference and Pre-Conference Workshop Cancellation Policy

- A Personal Welcome

- About the Conference

- Pre-Conference Workshops

- Certificate Program

- CPE/CEU Information

Guide to Writing A Poster Abstract

- Exhibitor Registration

Poster abstracts submitted to NCURA should serve as the initial report of knowledge, experience, or best practices in the field of research Administration. Submissions are evaluated by a review committee.

A well-written abstract is more likely to be considered as a finalist and, ultimately, for a recognition award. To expedite the review process, to assure effective communication, and to elevate the work toward the recognition award following, the following general suggestions will be helpful in submitting your abstract and description.

General suggestions

- Check for proper spelling and grammar.

- Use a standard typeface, such as Times Roman with a font size of 12.

- It is important to keep nonstandard abbreviations/acronyms to a minimum, to allow for readability and understanding.

- Do not include tables, figures, or graphs in the abstract. Such content is appropriate for the poster.

- Abstract should be 250 words or less and should summarize the overall objectives being presented in the poster. This can be included in bullet point format if preferred.

- The application should include a detailed description of poster make up itself and include the outcomes to be presented. Limit to 500 words (use the less=more concept).

- Try to organize the abstract with the following headings where appropriate, as explained below; purpose, methods, results, conclusions.

The abstract title conveys the content/subject of the poster. The title may be written as a question or the title may be written to suggest the conclusions, if appropriate. A short concise title may more easily catch a reader’s attention. Try to not use abbreviations or acronyms in titles.

The introductory sentence(s) may be stated as a hypothesis, a purpose, an objective, or as current evidence for a finding. Hypothesis is a supposition or conjecture used as a basis for further investigations. Purpose is a statement of the reason for conducting a project or reporting on a program, process or activity. Objective is the result that the author is trying to achieve by conducting a project, program, process or activity.

Briefly describe the methods of the project to define the data or population, outcome variables, and analytic techniques, as well as data collection procedures and frequencies. A description of statistical methods used may be included if appropriate.

The results should be stated succinctly to support only the purpose, objectives, hypothesis, or conclusions.

Conclusions

The conclusion(s) should highlight the impact of the project, and follow the methods and results in a logical fashion. This section should not restate results. Rather, the utility of the results and their potential role in the management of the project should be emphasized. New information or conclusions not supported by data in the results section should be avoided.

Important note

Poster program finalists are determined following evaluation of each actual poster by the review committee. Finalists will be notified by email no later than June 25th.

CONFERENCE PROGRAM

Registration information, workshop information, registration options, frequently asked questions, exhibitor information.

- Contact AAPS

- Get the Newsletter

How to Write a Really Great Presentation Abstract

Whether this is your first abstract submission or you just need a refresher on best practices when writing a conference abstract, these tips are for you..

An abstract for a presentation should include most the following sections. Sometimes they will only be a sentence each since abstracts are typically short (250 words):

- What (the focus): Clearly explain your idea or question your work addresses (i.e. how to recruit participants in a retirement community, a new perspective on the concept of “participant” in citizen science, a strategy for taking results to local government agencies).

- Why (the purpose): Explain why your focus is important (i.e. older people in retirement communities are often left out of citizen science; participants in citizen science are often marginalized as “just” data collectors; taking data to local governments is rarely successful in changing policy, etc.)

- How (the methods): Describe how you collected information/data to answer your question. Your methods might be quantitative (producing a number-based result, such as a count of participants before and after your intervention), or qualitative (producing or documenting information that is not metric-based such as surveys or interviews to document opinions, or motivations behind a person’s action) or both.

- Results: Share your results — the information you collected. What does the data say? (e.g. Retirement community members respond best to in-person workshops; participants described their participation in the following ways, 6 out of 10 attempts to influence a local government resulted in policy changes ).

- Conclusion : State your conclusion(s) by relating your data to your original question. Discuss the connections between your results and the problem (retirement communities are a wonderful resource for new participants; when we broaden the definition of “participant” the way participants describe their relationship to science changes; involvement of a credentialed scientist increases the likelihood of success of evidence being taken seriously by local governments.). If your project is still ‘in progress’ and you don’t yet have solid conclusions, use this space to discuss what you know at the moment (i.e. lessons learned so far, emerging trends, etc).

Here is a sample abstract submitted to a previous conference as an example:

Giving participants feedback about the data they help to collect can be a critical (and sometimes ignored) part of a healthy citizen science cycle. One study on participant motivations in citizen science projects noted “When scientists were not cognizant of providing periodic feedback to their volunteers, volunteers felt peripheral, became demotivated, and tended to forgo future work on those projects” (Rotman et al, 2012). In that same study, the authors indicated that scientists tended to overlook the importance of feedback to volunteers, missing their critical interest in the science and the value to participants when their contributions were recognized. Prioritizing feedback for volunteers adds value to a project, but can be daunting for project staff. This speed talk will cover 3 different kinds of visual feedback that can be utilized to keep participants in-the-loop. We’ll cover strengths and weaknesses of each visualization and point people to tools available on the Web to help create powerful visualizations. Rotman, D., Preece, J., Hammock, J., Procita, K., Hansen, D., Parr, C., et al. (2012). Dynamic changes in motivation in collaborative citizen-science projects. the ACM 2012 conference (pp. 217–226). New York, New York, USA: ACM. doi:10.1145/2145204.2145238

📊 Data Ethics – Refers to trustworthy data practices for citizen science.

Get involved » Join the Data Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

📰 Publication Ethics – Refers to the best practice in the ethics of scholarly publishing.

Get involved » Join the Publication Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

⚖️ Social Justice Ethics – Refers to fair and just relations between the individual and society as measured by the distribution of wealth, opportunities for personal activity, and social privileges. Social justice also encompasses inclusiveness and diversity.

Get involved » Join the Social Justice Topic Room on CSA Connect!

👤 Human Subject Ethics – Refers to rules of conduct in any research involving humans including biomedical research, social studies. Note that this goes beyond human subject ethics regulations as much of what goes on isn’t covered.

Get involved » Join the Human Subject Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🍃 Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics – Refers to the improvement of the dynamics between humans and the myriad of species that combine to create the biosphere, which will ultimately benefit both humans and non-humans alike [UNESCO 2011 white paper on Ethics and Biodiversity ]. This is a kind of ethics that is advancing rapidly in light of the current global crisis as many stakeholders know how critical biodiversity is to the human species (e.g., public health, women’s rights, social and environmental justice).

⚠ UNESCO also affirms that respect for biological diversity implies respect for societal and cultural diversity, as both elements are intimately interconnected and fundamental to global well-being and peace. ( Source ).

Get involved » Join the Biodiversity & Environmental Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

🤝 Community Partnership Ethics – Refers to rules of engagement and respect of community members directly or directly involved or affected by any research study/project.

Get involved » Join the Community Partnership Ethics Topic Room on CSA Connect!

Writing the Poster Abstract

Cite this chapter.

- Peter J. Gosling Ph.D. 2

502 Accesses

The poster abstract is the part of the overall presentation that is usually destined for publication in the proceedings or abstract book of the meeting. Specific skills are required to summarize large amounts of scientific text and data into a few sentences that still adequately set the scene and convey the appropriate message. The abstract is not merely a summary of your findings. It must be able to, and indeed will, stand alone. The restriction on the number of words, the format, and the deadline for receipt will be given by the conference organizers. It is common to supply a box outline in which the abstract must be typed or printed in a camera ready format. This is the lasting part of your presentation, and you need to devote a suitable amount of time to ensuring that it maintains the same high quality as the rest of your presentation. For this reason a good quality copy should be sent for publication, avoiding faxing, as the results are often difficult to read. For casual readers this may be the only part of your presentation that is seen. You should therefore avoid the use of phrases such as “evidence will be presented,” and make the abstract as representative of the whole presentation as possible.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Peter Gosling Associates, Staines, UK

Peter J. Gosling Ph.D.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1999 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Gosling, P.J. (1999). Writing the Poster Abstract. In: Scientist’s Guide to Poster Presentations. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4761-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4761-7_4

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4613-7157-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4615-4761-7

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Log In Username Enter your ACP Online username. Password Enter the password that accompanies your username. Remember me Forget your username or password ?

- Privacy Policy

- Career Connection

- Member Forums

© Copyright 2024 American College of Physicians, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 190 North Independence Mall West, Philadelphia, PA 19106-1572 800-ACP-1915 (800-227-1915) or 215-351-2600

If you are unable to login, please try clearing your cookies . We apologize for the inconvenience.

Preparing a Poster Presentation

Posters are a legitimate and popular presentation format for research and clinical vignettes. They efficiently communicate concepts and data to an audience using a combination of visuals and text. Most scientific meeting planners take advantage of the popularity and communication efficiency of poster presentations by scheduling more poster than oral presentations. Poster presentations allow the author to meet and speak informally with interested viewers, facilitating a greater exchange of ideas and networking opportunities than with oral presentations. Poster presentations often are the first opportunities for young investigators to present their work at important scientific meetings and preparatory for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Poster Production Timeline

In order to be successful, certain prerequisites must be met. First, you must have a desire to be scholastically effective and be willing to put the time into the design and production of the poster. Second, you need organizational skills. Like any other endeavor associated with deadlines, you must be able to deliver the product on time. Posters are associated with more deadlines than oral presentations, due to the necessary interaction with graphic artists, graphic production, and the needs of the meeting itself. Organizational skills are also needed to create a concise and logically structured graphic and text presentation of the research or vignette. In order to help you achieve these goals, this article addresses poster planning, production, and presentation. It may be helpful to create a poster production timeline .

- Determine if your poster will be judged at the scientific meeting. If so, ask for the judging criteria , which will be immensely helpful for you to plan and construct the poster.

- Know the rules . It is your responsibility to know the physical requirements for the poster including acceptable size and how it will be displayed. A 4' × 4' display area cannot accommodate a 6' × 6' poster and a 3' × 3' poster will look insignificant in an 8' × 8' display area. All scientific programs that sponsor a poster session will send you information on the display requirements at the time your poster is accepted for presentation. Review and follow the instructions precisely. However, be warned that not all scientific programs will automatically tell you how the poster will be displayed. Some programs provide a cork/tack-board system that allows you to display your poster by fastening it to a solid display board with stickpins. This gives you the option of displaying your poster as many individual parts (components of the poster, such as abstract, methods, graphics, conclusion, are fastened individually to the display board) or as one piece. Other programs "hang" their posters from a frame by large spring clips. This means that the poster must be created as a single unit and cannot be too heavy for the clips or too light such that it will curl upwards like a window shade. A few programs still use easels to display posters, mandating that the poster be constructed of or placed on a firm backing that can be supported in this way. The point is, find out how the poster will be displayed and engineer a poster that best meets the requirements.