Point of View

Definition of point of view.

Point of view is utilized as a literary device to indicate the angle or perspective from which a story is told. Essentially, point of view refers to the “eyes” of the narrative voice that determine the position or angle of vision from which the story is being relayed. Point of view is one of the most crucial choices made by fiction writers since it governs the reader’s access to the story and determines how much the reader is able to know at any given moment with regard to what is taking place in the narrative.

For example, Gregory Maguire is well-known for his novels that re-tell famous stories using a different point of view. In his work Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister , the story of Cinderella is told by one of the “ugly stepsisters” herself, rather than a removed fairy tale narrator .

In the lives of children, pumpkins turn into coaches, mice and rats turn into men. When we grow up, we realize it is far more common for men to turn into rats.

By shifting the viewpoint of the narrative voice, the reader is given an entirely different perspective and version of the famous story. This not only makes for an engaging and innovative experience for the reader, but the change in point of view also changes the story itself by presenting otherwise “unseen” information and opinions.

Examples of Commonly Used Points of View

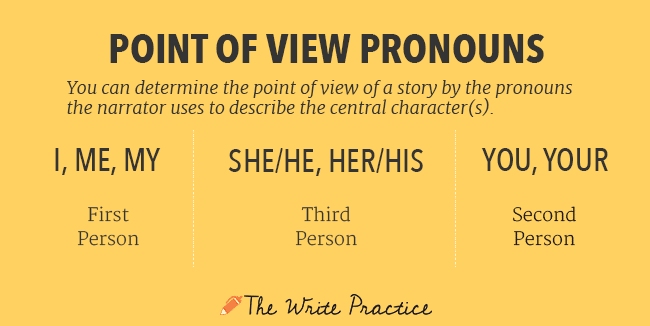

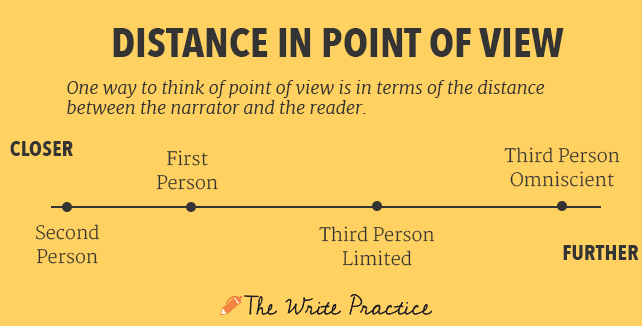

As a literary device, point of view is generally expressed through the use of pronouns. Each has its advantages and limitations. First and third person points of view are far more common than second person point of view in literature. First person narrative allows the writer to establish intimacy with the reader by allowing access to the narrator’s inner thoughts. Third person narrative is flexible in that the writer can focus on more than one character ’s actions and thoughts.

Here are some examples of commonly used points of view:

First Person

In first person point of view, one of the story’s characters is narrating the literary work. This viewpoint is indicated by the use of first person pronouns, including “I,” and the reader assumes that the character is close to the story’s action. First person narrative voice provides the reader an intimate and close look into a character’s thoughts, but the perspective of the story is limited by what the character is able to see and know.

Here are some well-known examples of literary works with first person point of view:

- The Great Gatsby

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- The Yellow Wallpaper

Third Person

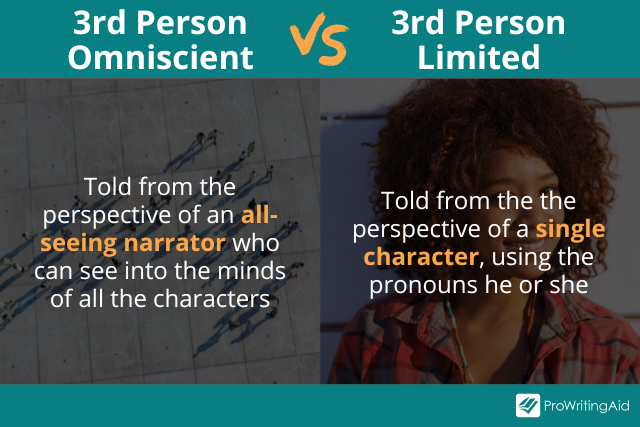

With third person point of view, there is a narrative presence telling the story and referring to the characters in the third person, as “he” or “she.” Third person point of view can be omniscient , meaning the narrator can see and know everything within the story, or limited, meaning the narrator is restricted in what they see and know of the story.

Here are some well-known examples of literary works with third person point of view:

- Lord of the Flies

- Little Women

- Fahrenheit 451

- The Lowland

Second Person

Second person point of view utilizes the pronoun “you” to address the reader and bring them into the action of the story. However, second person point of view is problematic in a couple of ways. First, it is a stylistic choice that is uncommon, especially in novel -length works. In addition, second person point of view can overwhelm the writer and confuse and/or alienate the reader. Most writers avoid constructing a narrative voice through second person point of view.

Difference Between Omniscient and Third Person Limited Point of View

Third person point of view is flexible as a literary device in that a writer can choose between omniscient or limited perspectives for the narrator. An omniscient narrator is aware of and knows everything about the story and its characters. There are no limitations for this narrator in terms of expressing any character’s thoughts, and this includes their own opinions and observations. An omniscient point of view features a narrator who knows more than the characters of a story.

A third person limited narrator utilizes third person storytelling, but is closely “assigned” to one character. Therefore, this limited narrator shares access with the reader to a character’s thoughts, feelings, experiences, etc., but is limited in doing so with other characters in the story. Writers choose third person limited point of view to create a deeper bond between a specific character and the reader.

Writing with Point of View

Writers decide who tells a story and the intended audience for it. When determining point of view as a literary device, the story can be told from the viewpoint of a character who is part of the story or from a narrative perspective that “sees” and knows the characters but is not one of them. It’s important for writers to consider benefits and limitations when deciding point of view, as it is essential for character development and the relationship between the narrative voice and the reader.

In addition, it’s important for writers to establish point of view as soon as possible for the reader so they are aware of whose perspective they are following. Though some writers choose to change point of view, done most often within a novel, the narrative voice should be consistent throughout a particular scene. Otherwise, disrupting the narrative perspective in the middle of a story’s action can be confusing and jarring for the reader. Changing the point of view for a subplot , alternate section, or different chapter of a literary work can be valuable; however, there should be continuity of narrative throughout the course of a story’s scene in consideration of the reader.

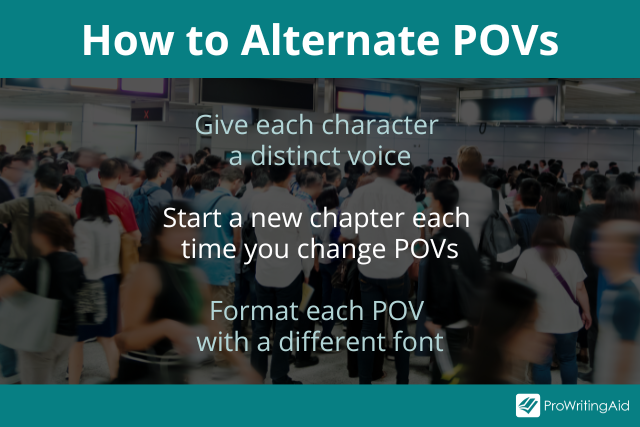

Alternating Point of View

Alternating point of view is a complex type of observation or narration. While narrating, he/she can change their position from the first person to the third person or even second person. It depends on the setting , situation, and voice of the characters and their different perspectives. This technique was used very successfully by Kurt Vonnegut or Italo Calvino in their novels with authorial assertion and intervention, such as Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut. Also, the alternating point of view is used for long narration or a chapter-wise, to develop characters and story. It is not used for one sentence or a paragraph.

First Person Point of View as a Protagonist and Common Character

The first person point of view uses first-person pronouns. I, me, mine, etc. The first-person point of view is mostly used in fiction, autobiographies , or semi-autobiographies. The person speaking becomes the center point of the narrative, thus becoming a protagonist of the story most of the time. However, sometimes this person is also a typical narrator when it comes to the big events or significant happenings in history. Such a first-person narrator takes part only as a commoner but describes all the major events and characters through him/her. Usually, they paint the picture of a person, presenting him/her as a protagonist and himself as an ordinary character. Fiction usually adapts this form of narration when they use great heroes from history as protagonists.

Use of Point of View in Sentences

- He loves to people from the window of his castle. But, such is his life; he is not allowed to step outside. (Third-person point of view)

- I heard a shrill cry followed by speeding footsteps. I wondered if someone was in trouble. Sadly when I reached the alley, there was no one. (First-person point of view)

- This is how you prepare a tasty lemonade. You juice the lemons, and you can get more juice by rolling the lemons on the counter using force. (Second-person point of view)

- Although Jay viewed the group with suspicion when he decided to meet them and said, “I do not suspect you in any way, but we still need to talk.” (Third-person objective point of view)

- As the children settled into their rooms, Lisa hoped they would sleep peacefully without fear. She silently wished them goodnight before closing the door.”

Examples of Point of View in Literature

Example 1: invisible man (ralph ellison).

I was never more hated than when I tried to be honest. Or when, even as just now I’ve tried to articulate exactly what I felt to be the truth. No one was satisfied.

In Ellison’s novel, the protagonist tells his own story from a first-person point of view. This passage reflects both the power of this narrative perspective and its limitations. By telling his own story, the protagonist is able to have a close connection with the reader and directly express his true thoughts, feelings, and ideas. However, due to this restricted form of narration, the reader must rely solely on the viewpoint of the protagonist. This puts a level of responsibility on the reader to determine whether the protagonist is reliable in his narration and to fill in any gaps in the story that are ambiguous or unaddressed in a full manner by the narrator.

Example 2: The Story of an Hour (Kate Chopin)

She said it over and over under her breath: “free, free, free!” The vacant stare and the look of terror that had followed it went from her eyes. They stayed keen and bright. Her pulses beat fast, and the coursing blood warmed and relaxed every inch of her body.

Chopin’s short story is told through a third-person limited point of view. The narrative perspective is that of Louise Mallard, the protagonist of the story, though she does not relay the narrative herself in the first person. Instead, the narrator relays to the reader Louise’s actions, thoughts, and feelings as she learns of her husband’s supposed death. This is a clever literary choice due to the fact that Louise spends much of her time in the story in a room alone , away from the other characters.

Chopin establishes a relationship between the third-person narrator and the reader in terms of access to Louise’s mind. This is reflected in the passage as the narrator conveys to the reader that Louise feels “free” at the news of her husband’s death. This “freedom” is something that Louise would not have expressed to any character in the story, yet the narrative perspective allows the reader to know and understand her thoughts.

Example 3: The Death of Ivan Ilych (Leo Tolstoy)

In reality it was just what is usually seen in the houses of people of moderate means who want to appear rich, and therefore succeed only in resembling others like themselves: there are damasks, dark wood, plants, rugs, and dull and polished bronzes — all the things people of a certain class have in order to resemble other people of that class. His house was so like the others that it would never have been noticed, but to him it all seemed to be quite exceptional.

Tolstoy’s well-known story of Ivan Ilych is told through an omniscient point of view. This passage reflects that the omniscient narrator governs the telling of the story through the information that is presented to the reader and the manner in which that information is relayed. For example, the omniscient narrator describes for the reader the setting of the character’s home by describing the objects inside. This creates an image that allows the reader to picture the scene.

However, the omniscient narrator is also characterizing the setting of the home by inserting opinions about it with phrases such as “who want to appear rich.” This is important because the omniscient narrator’s description and the inserted characterization influences both the reader’s literal image of the scene and their perception of its meaning in terms of an emotional response. As a result, the omniscient narrator holds the power to influence all aspects of a story for a reader–not just the way things look or what events take place, but how the reader should feel about it, Therefore, in response to an omniscient narrator, the reader should be aware of this effect so as to approach this point of view with critical thinking.

Synonyms of Point of View

Some of the words close to the point of view in meanings are opinion, view, attitude , feeling, sentiment, thoughts, ideas, position, perspective, viewpoint, standpoint, outlook, stand, stance, side, or position.

Post navigation

- Literary Terms

- Point of View

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Use Point of View

I. What is Point of View?

Point of view (POV) is what the character or narrator telling the story can see (his or her perspective). The author chooses “who” is to tell the story by determining the point of view. Depending on who the narrator is, he/she will be standing at one point and seeing the action. This viewpoint will give the narrator a partial or whole view of events as they happen. Many stories have the protagonist telling the story, while in others, the narrator may be another character or an outside viewer, a narrator who is not in the story at all. The narrator should not be confused with the author, who is the writer of the story and whose opinions may not be those written into the narrative.

II. Examples of Point of View

Sandra Cisneros wrote a story called “Eleven.” The point of view is the perspective of 11-year-old Rachel. The story takes place at school during her birthday and is about her humiliation of receiving an old sweater. Throughout the story, she speaks in the first-person point of view, sharing her thoughts as events unfold.

“Only today I wish I didn’t have only eleven years rattling inside me like pennies in a tin Band-Aid box. Today I wish I was one hundred and two instead of eleven because if I was one hundred and two I’d have known what to say when Mrs. Price put the red sweater on my desk” (Cisneros).

A fun activity is to rewrite the story from each character’s point of view. What is the teacher thinking as she tries to get rid of this ugly red sweater in her classroom? Maybe it reminds her of her demanding mother! How does the sweater feel being tossed and pushed around, unwanted and unloved? Maybe some sweet old lady had knitted it with love for a granddaughter who now has rejected it. Why does Sylvia say it belongs to Rachel? Is she jealous of Rachel for some reason? Each character will have a slightly different story from his or her perspective.

III. Types of Point of View

First person: The example above with little Rachel is told in the first-person point of view, meaning that we are seeing events through the eyes of the character telling the story.

Second person: In second person, the narrator is speaking to YOU. This isn’t very common in fiction, unless the narrator is trying to talk to the reader personally. We see second-person point of view mostly in poems, speeches, instructional writing, and persuasive articles.

Third person: With third-person point of view, the narrator is describing what’s seen, but as a spectator. If the narrator is a character in the story, then we are reading what he or she observes as the story unfolds. This narrator has three possible perspectives.

- Limited – In limited third-person, the narrator sees only what’s in front of him/her, a spectator of events as they unfold and unable to read any other character’s mind.

- Omniscient – An omniscient narrator sees all, much as an all knowing god of some kind. He or she sees what each character is doing and can see into each character’s mind. This is common with an external character, who is standing above, watching the action below (think of a person with a crystal ball, peering in).

- Limited Omniscient – The limited omniscient third-person narrator can only see into one character’s mind. He/she might see other events happening, but only knows the reasons of one character’s actions in the story.

IV. The Importance of Point of View

Point of view is important in a story because it helps the reader understand characters’ feelings and actions. Each character will have his or her own perspective, so whoever is telling the story will impact the reader’s opinion of other characters and events.

As in the example above with Rachel and the red sweater, each point of view could be an entirely different story. Perhaps Rachel had embarrassed Sylvia horribly one day, so the sympathy we feel for Rachel in her perspective may change to sympathy for Sylvia if the point of view was switched.

Additionally, reading the story from a character in the story versus an external character changes the amount of information a reader has as the story unfolds. With an omniscient third-person, we can see everything before other characters do, which gives us forewarning about other events. With a limited third-person, we are not allowed to see other events until the narrator does so. This may leave us with more surprises as we read.

V. Examples of Point of View in Pop Culture

A very popular (and very old!) game is Mario Brothers. A gamer took the game and made a video of it in first-person point of view. It’s almost a dizzying experience to see Mario catch coins and jump around from his viewpoint.

Arcades have had games with a first-person POV for years. You sit in the console to drive the car in a race, or use the pistol and fire at targets. Racing games are probably the easiest to play as a first-person. With most games, you control the character in a game, but almost from a second-person POV. You can see your character as you control it within the game space just as another character would.

VI. Examples of Point of View in Literature

“Diary of a Wimpy Kid” by Jeff Kinney has been cracking kids up since 2007, as the protagonist, Greg Heffley, details his experiences in his trusty journal; he claims it’s NOT a diary. He even supplies stick drawings with bubble speech to illustrate special, usually devastating or hilarious, occurrences. Written in the first-person POV, we follow him through his days with his friends and family. Greg’s dry sense of reality as he tells his sad tales leaves us giggling sympathetically – you can’t help but feel sorry for him, and many kids can relate to his frustrations. There are nine books as of 2015, each one focusing on specific conflicts Greg must overcome as he makes his way through middle school and attempts to fit in with his family.

“First of all, let me get something straight: This is a Journal, not a diary. I know what it says on the cover, but when Mom went out to buy this thing I specifically told her to get one that didn’t say “diary” on it. Great. All I need is for some jerk to catch me carrying this book around and get the wrong idea” (Kinney 1). http://www.funbrain.com/journal/Journal.html?ThisJournalDay=1&ThisPage=2

The book is so popular, that it was also made into a movie.

VII. Related Terms

Narrator: The narrator is the person who tells the story. There are different types of narrators, such as internal and external. Each narrator will have his or her own perspective or point of view as the story is told.

Viewpoint: Viewpoint is the perspective at which something is seen. If three people see an accident, each person will have his or her own version of what happened depending on where the person was at the time it happened.

VIII. Conclusion

Point of view is an important part of all writing. It makes stories interesting, gives research its serious tone, poems and persuasive works their personal tone, and allows readers to easily follow all writing. Keeping in mind the different types of POV and when to use them will make your writing stronger.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Literary Analysis Essay

Literary Analysis Essay Writing

Last updated on: May 21, 2023

Literary Analysis Essay - Ultimate Guide By Professionals

By: Cordon J.

Reviewed By: Rylee W.

Published on: Dec 3, 2019

A literary analysis essay specifically examines and evaluates a piece of literature or a literary work. It also understands and explains the links between the small parts to their whole information.

It is important for students to understand the meaning and the true essence of literature to write a literary essay.

One of the most difficult assignments for students is writing a literary analysis essay. It can be hard to come up with an original idea or find enough material to write about. You might think you need years of experience in order to create a good paper, but that's not true.

This blog post will show you how easy it can be when you follow the steps given here.Writing such an essay involves the breakdown of a book into small parts and understanding each part separately. It seems easy, right?

Trust us, it is not as hard as good book reports but it may also not be extremely easy. You will have to take into account different approaches and explain them in relation with the chosen literary work.

It is a common high school and college assignment and you can learn everything in this blog.

Continue reading for some useful tips with an example to write a literary analysis essay that will be on point. You can also explore our detailed article on writing an analytical essay .

On this Page

What is a Literary Analysis Essay?

A literary analysis essay is an important kind of essay that focuses on the detailed analysis of the work of literature.

The purpose of a literary analysis essay is to explain why the author has used a specific theme for his work. Or examine the characters, themes, literary devices , figurative language, and settings in the story.

This type of essay encourages students to think about how the book or the short story has been written. And why the author has created this work.

The method used in the literary analysis essay differs from other types of essays. It primarily focuses on the type of work and literature that is being analyzed.

Mostly, you will be going to break down the work into various parts. In order to develop a better understanding of the idea being discussed, each part will be discussed separately.

The essay should explain the choices of the author and point of view along with your answers and personal analysis.

How To Write A Literary Analysis Essay

So how to start a literary analysis essay? The answer to this question is quite simple.

The following sections are required to write an effective literary analysis essay. By following the guidelines given in the following sections, you will be able to craft a winning literary analysis essay.

Introduction

The aim of the introduction is to establish a context for readers. You have to give a brief on the background of the selected topic.

It should contain the name of the author of the literary work along with its title. The introduction should be effective enough to grab the reader’s attention.

In the body section, you have to retell the story that the writer has narrated. It is a good idea to create a summary as it is one of the important tips of literary analysis.

Other than that, you are required to develop ideas and disclose the observed information related to the issue. The ideal length of the body section is around 1000 words.

To write the body section, your observation should be based on evidence and your own style of writing.

It would be great if the body of your essay is divided into three paragraphs. Make a strong argument with facts related to the thesis statement in all of the paragraphs in the body section.

Start writing each paragraph with a topic sentence and use transition words when moving to the next paragraph.

Summarize the important points of your literary analysis essay in this section. It is important to compose a short and strong conclusion to help you make a final impression of your essay.

Pay attention that this section does not contain any new information. It should provide a sense of completion by restating the main idea with a short description of your arguments. End the conclusion with your supporting details.

You have to explain why the book is important. Also, elaborate on the means that the authors used to convey her/his opinion regarding the issue.

For further understanding, here is a downloadable literary analysis essay outline. This outline will help you structure and format your essay properly and earn an A easily.

DOWNLOADABLE LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY OUTLINE (PDF)

Types of Literary Analysis Essay

- Close reading - This method involves attentive reading and detailed analysis. No need for a lot of knowledge and inspiration to write an essay that shows your creative skills.

- Theoretical - In this type, you will rely on theories related to the selected topic.

- Historical - This type of essay concerns the discipline of history. Sometimes historical analysis is required to explain events in detail.

- Applied - This type involves analysis of a specific issue from a practical perspective.

- Comparative - This type of writing is based on when two or more alternatives are compared

Examples of Literary Analysis Essay

Examples are great to understand any concept, especially if it is related to writing. Below are some great literary analysis essay examples that showcase how this type of essay is written.

A ROSE FOR EMILY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE GREAT GATSBY LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER LITERARY ANALYSIS ESSAY

If you do not have experience in writing essays, this will be a very chaotic process for you. In that case, it is very important for you to conduct good research on the topic before writing.

There are two important points that you should keep in mind when writing a literary analysis essay.

First, remember that it is very important to select a topic in which you are interested. Choose something that really inspires you. This will help you to catch the attention of a reader.

The selected topic should reflect the main idea of writing. In addition to that, it should also express your point of view as well.

Another important thing is to draft a good outline for your literary analysis essay. It will help you to define a central point and division of this into parts for further discussion.

Literary Analysis Essay Topics

Literary analysis essays are mostly based on artistic works like books, movies, paintings, and other forms of art. However, generally, students choose novels and books to write their literary essays.

Some cool, fresh, and good topics and ideas are listed below:

- Role of the Three Witches in flaming Macbeth’s ambition.

- Analyze the themes of the Play Antigone,

- Discuss Ajax as a tragic hero.

- The Judgement of Paris: Analyze the Reasons and their Consequences.

- Oedipus Rex: A Doomed Son or a Conqueror?

- Describe the Oedipus complex and Electra complex in relation to their respective myths.

- Betrayal is a common theme of Shakespearean tragedies. Discuss

- Identify and analyze the traits of history in T.S Eliot’s ‘Gerontion’.

- Analyze the theme of identity crisis in The Great Gatsby.

- Analyze the writing style of Emily Dickinson.

If you are still in doubt then there is nothing bad in getting professional writers’ help.

We at 5StarEssays.com can help you get a custom paper as per your specified requirements with our do essay for me service.

Our essay writers will help you write outstanding literary essays or any other type of essay. Such as compare and contrast essays, descriptive essays, rhetorical essays. We cover all of these.

So don’t waste your time browsing the internet and place your order now to get your well-written custom paper.

Frequently Asked Questions

What should a literary analysis essay include.

A good literary analysis essay must include a proper and in-depth explanation of your ideas. They must be backed with examples and evidence from the text. Textual evidence includes summaries, paraphrased text, original work details, and direct quotes.

What are the 4 components of literary analysis?

Here are the 4 essential parts of a literary analysis essay;

No literary work is explained properly without discussing and explaining these 4 things.

How do you start a literary analysis essay?

Start your literary analysis essay with the name of the work and the title. Hook your readers by introducing the main ideas that you will discuss in your essay and engage them from the start.

How do you do a literary analysis?

In a literary analysis essay, you study the text closely, understand and interpret its meanings. And try to find out the reasons behind why the author has used certain symbols, themes, and objects in the work.

Why is literary analysis important?

It encourages the students to think beyond their existing knowledge, experiences, and belief and build empathy. This helps in improving the writing skills also.

What is the fundamental characteristic of a literary analysis essay?

Interpretation is the fundamental and important feature of a literary analysis essay. The essay is based on how well the writer explains and interprets the work.

Law, Finance Essay

Cordon. is a published author and writing specialist. He has worked in the publishing industry for many years, providing writing services and digital content. His own writing career began with a focus on literature and linguistics, which he continues to pursue. Cordon is an engaging and professional individual, always looking to help others achieve their goals.

Was This Blog Helpful?

Keep reading.

- Interesting Literary Analysis Essay Topics for Students

- Write a Perfect Literary Analysis Essay Outline

People Also Read

- cause and effect essay

- expository essay outline

- how to write a poem

- transition words for essays

- cause and effect essay topics

Burdened With Assignments?

Advertisement

- Homework Services: Essay Topics Generator

© 2024 - All rights reserved

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Point of View: What Is It? (With 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th POV Examples)

Hannah Yang

One of the most powerful tools in a writer’s toolkit is point of view.

So, what is point of view in literature, and why is it important?

The short answer is that point of view, also called POV, refers to the angle from which a story is told. It includes the specific character who’s telling the story, as well as the way the author filters the story through that character to the reader.

This article will discuss the different points of view you can use in writing, including their strengths, weaknesses, and examples from literature.

What Is Point of View in Writing and Literature?

The importance of point of view, summary of the different points of view, first person point of view, second person point of view, third person point of view, fourth person point of view, what about alternating point of view, conclusion on point of view.

Point of view refers to the perspective through which a story is told.

To understand point of view, try this quick exercise. Imagine you’re telling a story about a well-traveled stranger who enters a small, rural town.

What are all the different perspectives you could tell this story from?

You might tell it from the perspective of the stranger who has never seen this town before and views all of its buildings and streets through fresh eyes.

You might tell it from the collective perspective of the townspeople, who are curious about who this stranger is and why he’s come to this part of the world.

You might even tell it from the perspective of an all-seeing entity, who can see into the minds of both the stranger and the townspeople, all at the same time.

Each of these options centers a different point of view—a different angle for the reader to approach the same story.

Point of view is one of the most important aspects of your story that you must decide before putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard). It can have an enormous impact on the tone, style, and even plot of the story.

Each point of view has its own strengths and limitations. In order to choose the right POV, you have to know what you want your story to accomplish.

For example, if you choose first person POV, you’ll be able to immerse the reader in a single character’s voice, humor, and worldview. On the other hand, you also have to show the world with that character’s biases and flawed observations.

The right POV can also completely change the way the story feels. POV is a matter of choice, but one that affects every part of your story or novel.

F. Scott Fitzgerald had to rewrite The Great Gatsby because he initially wrote it in Gatsby’s voice. He decided it would be much more powerful coming from Nick’s more naïve point of view. Imagine that masterpiece with a different point of view—it wouldn’t have the same objective, reliable feeling that it has now.

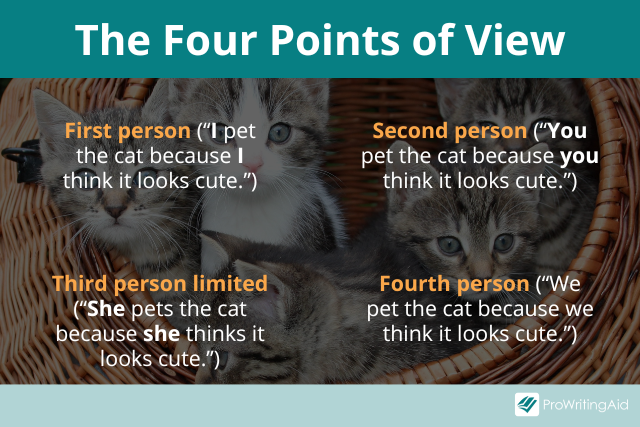

There are four main points of view that we’ll be discussing in this article: first person, second person, third person (with two subtypes: limited and omniscient), and fourth person.

- First person (“ I pet the cat because I think it looks cute.”)

- Second person (“ You pet the cat because you think it looks cute.”)

- Third person limited (“ She pets the cat because she thinks it looks cute.”) and third person omniscient (“ She pets the cat because she thinks it looks cute. Little does she know, this cat is actually an alien in disguise.”)

- Fourth person (“ We pet the cat because we think it looks cute.”)

Read on to learn the strengths and weaknesses of each of these points of view.

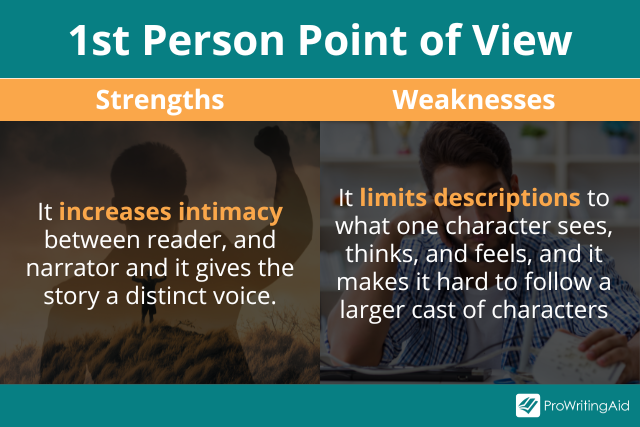

With first person point of view, everything is told intimately from the viewpoint of a character, usually your protagonist. The author uses the first person pronouns I and me to show readers what this character sees and thinks.

First person is the best way to show the story from one person’s point of view because you have an individual person telling you her story directly in her own words. It’s also the easiest way to tell a story that uses a distinct, quirky voice.

The limitations of first person point of view, however, restrict you to only describing what this character sees, thinks, and feels, and sometimes that narrator can be unreliable.

First Person POV Examples

One great example of first person POV is The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. The narrator is a flawed character, but we see the world entirely through her eyes, complete with her own faults and sorrows. Here’s a short excerpt:

“I began to think vodka was my drink at last. It didn’t taste like anything, but it went straight down into my stomach like a sword swallowers’ sword and made me feel powerful and godlike.”

Compare that with the intimacy you get when reading Scout’s view of things in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird . She speaks with a childlike innocence, giving the reader that same feeling, even if we understand the racism of her town better than she does herself.

“We lived on the main residential street in town—Atticus, Jem and I, plus Calpurnia our cook. Jem and I found our father satisfactory: he played with us, read to us, and treated us with courteous detachment.”

Second person point of view, which uses the pronoun you , is one of the least used POVs in literature because it places the reader in the hot seat and is hard to manage for a full-length novel. It’s used in experimental literature to try out new styles of writing.

In the wrong hands, it just feels gimmicky. But when done well, second person point of view can accomplish a range of wonderful effects.

Second Person POV Examples

“Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang is a fantastic example of second person POV. It takes the form of a story a mother tells her daughter to explain the circumstances of the daughter’s life. Because the mother is speaking directly to the daughter, the story is imbued with an extra sense of intimacy.

“Right now your dad and I have been married for about two years, living on Ellis Avenue; when we move out you’ll still be too young to remember the house, but we’ll show you pictures of it, tell you stories about it.”

The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin is a Hugo-winning fantasy novel that uses many different POVs, including second person. The second person point of view serves to provide a feeling of disorientation, like the protagonist needs to talk to herself to remind herself what’s going on. Here’s a short excerpt from the very beginning of the story:

“You are she. She is you. You are Essun. Remember? The woman whose son is dead.”

Third person point of view uses pronouns like he , she , and it . This POV allows the reader to follow a character, or multiple characters, from a more distanced perspective than first or second person.

Third Person Limited vs Third Person Omniscient

There are two subtypes of third person point of view: limited and omniscient.

In third person limited, the story follows only one character’s viewpoint throughout the entire piece. This means your reader sees only what the third person narrator sees and learns things at the same time the third person narrator does.

You can show what your main character thinks, feels, and sees, which helps close the emotional distance between your reader and the main character.

This is an excellent POV to use when your story focuses on a single character. In many ways, third person limited is quite similar to first person, even though it involves different pronouns.

The drawback with third person limited POV is that you can only follow one character. Showing other characters’ thoughts and feelings is a no-no.

The other type of third person POV is third person omniscient. In this POV, the story is told from the perspective of an omniscient narrator, who can see inside the heads of all the characters in the story.

This is a great POV to use when you have multiple characters, each with their own plot line to follow, and you want your reader to see everything as it unfolds. It’s also useful for imparting universal messages and philosophies, since the narrator can draw conclusions that no character would be able to on its own.

The downside to third person omniscient is that it can be emotionally distant from the story. Because you’re constantly jumping around to different characters and their story arcs, it’s harder for your reader to get as emotionally involved with your characters.

Third Person POV Examples

Examples of the third person limited POV are the Harry Potter novels. The reader sees everything that’s going on, but is limited to Harry’s point of view. We’re surprised when Harry is surprised, and we find out the resolution at the ending when Harry does. Here’s a short excerpt from the seventh book, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows:

“Harry sat up and examined the jagged piece on which he had cut himself, seeing nothing but his own bright green eye reflected back at him.”

An excellent example of third person omniscient POV is Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables . The reader sees everything that is happening in the story and gets a vivid lesson in politics and society in France’s history.

“He was cunning, rapacious, indolent and shrewd, and by no means indifferent to maidservants, which was why his wife no longer kept any.”

Fourth person is a newer POV that only recently started to be recognized as a distinct POV. It involves a collective perspective, using the plural pronouns we and us .

This POV allows you to tell a story from the perspective of a group, rather than an individual. Since there’s no singular narrative, this option is great for critiquing larger institutions and social norms. Fourth person is even rarer than second person, but when it’s done well, it can be very powerful.

Fourth Person POV Examples

“A Rose for Emily” by William Faulkner is told from the perspective of an entire town.

“We did not say she was crazy then. We believed she had to do that. We remembered all the young men her father had driven away, and we knew that with nothing left, she would have to cling to that which had robbed her, as people will.”

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides is told from the perspective of a group of teenage boys.

“They were short, round-buttocked in denim, with roundish cheeks that recalled that same dorsal softness. Whenever we got a glimpse, their faces looked indecently revealed, as though we were used to seeing women in veils.”

You might choose to write a novel or story with multiple different points of view.

Some books have two main characters and switch back and forth between their perspectives—this is very common in the romance genre, for instance. Others rotate between three or more characters.

Alternating POV is a great option if your story features multiple main characters, all of whom play an equally important role in the story. The biggest drawback is that you risk confusing your reader when you switch back and forth.

Make sure your reader knows when you’re switching POVs. One common solution is to include a chapter break each time the perspective changes. Some books change the font for each POV, or even the color of the typeface.

It’s also important to make sure each character has a distinct voice. For example, maybe one character writes with short, brusque sentences, while another writes with long, flowery sentences. Keeping the different POVs distinct is crucial for success.

There you have it—a complete guide to point of view and how to choose the right POV for your story.

Before you start experimenting with point of view, get comfortable with the basics first. Read works by authors who use these different POVs with great success to understand how each POV changes the narrative arc of the story.

Happy writing!

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, what is point of view first, second, and third person.

General Education

One of the best ways to prepare for the AP Literature exam is to learn about different literary devices and how you can use them to analyze everything from poetry to novels. Not only will this help you on the multiple choice section of the test, it’s critical for earning perfect scores on your essays, too!

Today, we’re going to take a closer look at one specific device: point of view. First, we’ll give you the point of view definition, then we’ll explain how the work’s narrator affects its point of view. Then we’ll explain the four types of point of view and provide examples and analysis for each one.

By the end of this article, you’ll be a point of view expert! So let’s get started.

Point of View: Definition and Meaning

In literature and poetry, point of view is defined as the perspective from which a story is told. Put another way, a story’s point of view is a way to articulate and analyze the position of the narrator in relation to the story they’re telling. Is the narrator a participant in the story they’re telling? Or are they describing events that happened to someone else? Both of these perspectives are different types of point of view (which we’ll talk about in a lot more depth later in this article, so hang tight)!

So how do you figure out the point of view in a text? In order to find the point of view of a story, you first have to identify whose perspective the story is told from. That’s because the perspective of the story determines a piece of literature’s point of view! That means that in order to establish a text’s point of view, you have to figure out the narrator of the text first.

What Is a Narrator?

Okay...so obviously figuring out the narrator of a piece of literature is important. But what’s a narrator, exactly? No matter what type of text you’re reading—whether it’s a newspaper article, a textbook, a poem, or a best-selling novel—someone is communicating the story to the reader. In literary terms, we call that someone the text’s narrator.

In other words, the narrator of a piece of literature is the person telling the story. And you know what’s even more helpful than that? Almost all written texts—whether they’re fiction, non-fiction, poetry, or otherwise—have a narrator.

And since a narrator and point of view go hand in hand, that means that almost all texts have a point of view, too!

Finding the Narrator

So how do you figure out the narrator of a text? Sometimes the narrator of a text is pretty easy to determine. For example, for a newspaper article, the narrator of the story is obviously the reporter who’s written the piece to report the facts. They’re the person who followed the story’s trail, and now they’re sharing the story with you!

Another good example of an “easy to find” comes from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick . The very first sentence of the book reads, “Call me Ishmael.” Because that’s a line in the text rather than a piece of dialogue that uses quotation marks, you know it’s the narrator speaking to the audience. In other words, the narrator of Moby Dick identifies himself and tells you his name in the very first line of the book!

But figuring out the narrator of the text isn’t always that easy. For example, the Harry Potter books by J.K Rowling don’t have an easily identifiable narrator. Neither do some classic works, like The Giver by Lois Lowry or Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen . What do you do in those situations? Well, just hang tight: we’ll walk you through how point of view can help you figure out the narrator in these tricky situations !

Narrator vs. Point of View: What’s the Difference?

Before we start really digging into point of view, it’s worth pausing a minute to talk about the differences between point of view and narration. Because narration and point of view are closely linked, it’s tempting to think of them as interchangeable terms.

But the narrator of a text and the point of view of a text are two different things. The narrator is who is telling the story. In contrast, a text’s point of view is the perspective the story is being told from. If you think of the narrator as a person, their point of view is the angle they’re taking on the story.

Think of it this way: in literature, point of view and narrators go together like...well, like thunder and lightning. You can’t have one without the other, but they’re definitely not the same thing.

The 4 Types of Point of View

Okay, let’s look more closely at the four different types of point of view found in literature . In the following sections, we’ll explain each type of point of view, give you tips for figuring out if something is written in that perspective, and then walk you through a real-life example of that point of view in literature.

In first person point of view, you see the story through the narrator's eyes

First Person Point of View

In first person point of view, the story is told from the narrator’s perspective. This allows the narrator to give readers their first-hand experience, including what they saw, felt, thought, heard, said, and did. Think of it kind of like The Blair Witch Project : in first person point of view, it’s like the narrator is wearing a GoPro camera strapped to their forehead. The reader sees exactly what the narrator sees and gets their singular perspective on the events that unfold. In other words, a first person point of view makes the narrator the eyewitness to the plot of the story.

Using a first person point of view allows an author to dive much more deeply into the narrator’s character, since the reader gets to hear the narrator’s inner thoughts and experience the narrator’s emotions. Additionally, it makes the narrator the main character, or protagonist, of the story. If something is written in first person, it’s a pretty big indicator that the narrator is going to play a pivotal role in communicating the text’s messages or themes.

But there are also some pretty major limitations to a first person point of view, too. Just like real life, readers won’t be able to get the thoughts and feelings of other characters in the novel. Also, the narrator’s observations might be skewed depending on how they feel about other people. Because of that, first person narrators can be unreliable, meaning that their perspective skews the accuracy of the story they’re telling. That means it's up to the reader to determine whether they believe the narrator is being truthful or not.

Tips for Identifying First Person Point of View

In many ways, a first person point of view is one of the easiest to pick out because it uses first person pronoun s, like I, we, me, my, our, and us. If the book is written using these terms, then you can pretty much guarantee that the author is using first person!

Keep in mind that not all first person narrators are the book’s main character, l ike Moby Dick’s Ishmael or The Hunger Games’ Katniss Everdeen. That’s because first person narrators aren’t always the main characters in the work. Take, for instance, the Sherlock Holmes stories, where Dr. John Watson is the narrator. While he’s an important character in the story, he’s definitely not the main character--Sherlock Holmes is!

Additionally, sometimes first person narrators are anonymous, like third person narrators often are. (Don’t worry: we’ll get into third person narration in just a minute.) That’s why it’s best to look for pronouns when trying to figure out a work’s point of view! If you’re trying to find the narrator’s name, it might not always be there. A good example of this is Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 130,” where the narrator is describing the woman he loves. The narrator of the poem is never named, but because he uses pronouns like “I” and “my,” you know it’s written in first person.

Example of First Person Point of View: Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 29”

Many of Shakespeare’s sonnets are written in first person, and “Sonnet 29” is no different. Let’s look at the full poem and see why it qualifies as being written in first person:

I all alone beweep my outcast state, And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, And look upon myself and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featured like him, like him with friends possessed, Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope, With what I most enjoy contented least; Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, (Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven’s gate; For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

Remember, we can tell that something’s written in first person if it uses first person pronouns outside of dialogue. Since there’s no dialogue in this poem at all, we can look at the entire text to find evidence of the first person point of view.

Notice that the narrator (or speaker, as the narrator is often referred to in poetry) uses words like “I,” “me,” and “myself” throughout the poem. This is a clear indicator that this poem is written in a first person point of view!

Actually, “Sonnet 29” is a good example of something written in first person where the narrator isn’t named. But we can still learn quite a bit about them through the poem itself! For example, we learn that he’s an outcast (line 2) who is unhappy with his current status (line 4). Despite his all-encompassing misery (line 9), when he thinks upon his love, his spirits are lifted (lines 10, 11, and 12). As we start piecing the evidence together, we begin to get a clearer picture of who the narrator of the poem is, and the power love has to lift us out of even the bleakest circumstance.

Other Works Written in First Person Point of View

First person is a really popular writing technique, so it’s no surprise that there are tons of books written in this point of view! Here are a few other poems, books, and book series that you might be familiar with that use first person point of view:

- Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18”

- Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games book series

- Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories

Second person point of view uses pronouns like "you" and "your" to tell the story.

Second Person Point of View

In second person point of view, the story is told from the perspective of another character. Sometimes this character is another person in the book, but it can also be the reader themselves! More importantly, when a writer uses second person, they want readers to connect emotionally with the topic they’re writing about!

Here’s an example of what we mean. Say you’re reading an article about the amount of plastic pollution in the ocean. If the writer wants to pull on your heartstrings and make you take the issue they’re writing about seriously, they might use a second person point of view and write something like this:

“Imagine you’re on the vacation of your dreams sailing across the Caribbean. You can’t wait to get out into the open water, where everything will be calm, peaceful, and gorgeous. You take a nap as the captain sets sail, and when you return to the deck, you’re shocked by what you see. Instead of a vast expanse of sparkling blue water, you see a huge, bobbing mound of trash. Fast food containers, plastic bags, and discarded water bottles bob along the surface as far as you can see. It looks like you’re sailing through a garbage dump, and you feel equal parts disgust and despair.”

Using the second person point of view in a passage puts the reader into the story—in this case, it’s a story about pollution. Second person makes the reader feel like they’re making every move...from the joy of going on vacation, to the shock of seeing so much plastic in the water, to the “disgust and despair” of realizing what pollution is doing to the sea. Suddenly, the reader becomes more invested in what the author has to say about the problem, since the second person point of view makes them feel like they’ve experienced it first-hand!

While it’s very rare to find a text that’s written completely in second person, many authors will switch to this perspective when they want readers to feel connected to the topic they’re writing about.

Tips for Identifying Second Person Point of View

Like first person point of view, it’s pretty easy to spot the second person point of view...when you know what you’re looking for, that is. When something is written in second person, the writer uses second person pronouns (like “you,” “yourself,” and “your”) in the text that falls outside of dialogue , too.

Like we just mentioned, it’s pretty rare to find a whole text that’s written this way. More than likely, you’ll find a few paragraphs written in second person, rather than an entire work. The one exception to this rule is the classic Choose Your Own Adventure book ! You probably remember these from when you were a kid: each book had a topic, and at the bottom of each page, you were given decisions to make. Depending on what you chose, you’d flip to a different page in the book, and your decisions would affect the story!

Example of Second Person Point of View: Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerny

Jay McInerny uses second person to open his book, Bright Lights, Big City , which tells the story of life in the fast lane in 1980s New York. Let’s look at the first paragraph to see the second person point of view in action:

Notice that all the pronouns in this section are either “you” or “your,” which is a clear indicator that this is written in second person! It’s also a good example of how using second person can immediately pull someone into a narrative by making the reader and the main character one in the same. In this case, McInerny is creating a whole backstory for your character—from giving you friends like Tad to hinting at your dysfunctional marriage.

Other Works Written in Second Person Point of View

Second person is probably the rarest of the points of view. Usually writers will use second person in sections of their work to emphasize a point, rather than throughout their entire work. Here are some pieces of literature that use a second person point of view (at least in part):

- Langston Hughes’ “Hard Luck”

- Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller

- Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric

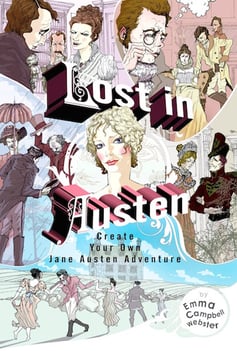

- Emma Campbell Webster’s Lost in Austen: Create Your Own Jane Austen Adventure

In third person omniscient point of view, the narrator is god-like and tells the reader everything!

Third Person Omniscient Point of View

The third type of perspective you can find in literature is a third person omniscient point of view. In third person omniscient, the narrator uses third person pronouns like “he,” “she,” “they,” and “their” to refer to all the characters in the work. As a result, the narrator removes themselves as a critical character in the work (unlike the narrators that use a first or second person point of view).

Additionally, because this is a third person omniscient perspective, the narrator is given god-like qualities over the story. ( Merriam-Webster defines an “omniscient” person as someone who has “universal or complete knowledge”! ) That means the narrator can dive into any character’s head and share their thoughts and emotions with the reader. Additionally, the narrator can move around in time and place to show the reader events that the characters themselves may not be aware of! That includes jumping around from location to location, or even moving backward and forward in time.

Using a third person omniscient narrator lets an author show the reader the whole gameboard, so to speak. There’s no real limit to what a narrator can show the readers! Consequently, it allows the author to build a robust world full of well-developed characters, since the author no longer has to contend with the single-character limits of a first or second person point of view. It’s also a particularly useful technique in works with large casts of characters, since the narrator can introduce the reader to each character more quickly—and with more detail—than other points of view would allow!

Example of Third Person Omniscient Point of View: Middlemarch by George Eliot

The narrator of George Eliot’s Victorian novel, Middlemarch, is an excellent example of how a third person omniscient narrator can give readers a comprehensive view of a text. Let’s take a look at the book’s opening paragraph to see this type of point of view in action:

Remember: omniscient narrators are god-like in that they can give you more information than a single character could provide from their limited perspective. In this case, Eliot’s omniscient narrator gives us tons of information about Miss Brooke. We know that she’s beautiful but not financially well off ( the narrator calls this living in “mixed conditions”), which is reflected in her “plain garments.” Regardless, Miss Brooke is also “remarkably clever.”

Beyond that, the narrator tells us about Miss Brooke’s family by looking into her past—which is easy given that the narrator is omniscient! We learn that she and her sister, Celia, aren’t aristocratic, but they come from a good family that includes admirals, clergymen, and politicians. This helps Eliot develop characters and situations quickly, which is important in a book with a large cast of characters like Middlemarch.

Other Works Written in Third Person Omniscient Point of View

Third person omniscient is a common point of view, especially in longer texts. Here are some examples of other works that feature an omniscient point of view:

- Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women

- Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest

- Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter

- Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

In third person limited point of view, it's as if the narrator is standing behind one character's shoulder.

Third Person Limited Point of View

The last point of view an author can use is the third person limited point of view. Just like the omniscient perspective we talked about earlier, texts written in a third person limited point of view use third person pronouns to discuss characters outside of dialogue. The difference between the two is in how much information the narrator shares with the reader.

With a third person limited perspective, the narrator is limited to giving you the perspective of a single character. The narrator can peek inside the character’s head to share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences, similar to a first person point of view. Unlike first person, however, a narrator using a third person limited point of view can also zoom out to give readers a better understanding of how the character they’re following fits into the text’s plot, setting, or situation!

Here’s an easy way of understanding the difference between a first person, third person omniscient, and a third person limited point of view. Think of the narrator as a person holding a camera. You, as the reader, get to see everything the camera sees. With first person point of view, it’s like the character has had the camera implanted in their brain. You can see whatever the character looks at and nothing more. With a third person limited point of view, on the other hand, it’s like the narrator is standing behind one character and filming over his shoulde r. Not only can you get a sense of what the character is seeing, the narrator can also step back a little bit to show readers what’s going on around the character...as long as the character stays in the frame.

Third person omniscient is the most comprehensive view. It’s as if the narrator is filming from the rafters of the building. They can zoom out to show everyone for a global perspective, or they can zoom in on different events to give you a better idea of what’s happening in specific situations. So why would a writer use a third person limited point of view? Well, it’s great for situations where knowing every single detail of a story would spoil the plot. Mystery novels, for instance, often use third person limited point of view. It allows the narrator to give you the detective’s thoughts and feelings while not spoiling the whodunit! It also allows the writer to focus on developing a single character while giving readers a better view of what’s going on around that character.

Example of Third Person Limited Point of View: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling

Like we mentioned earlier, all texts have a point of view...which means that the Harry Potter stories do, too! Let’s look at a passage from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to get a better idea of how a third person limited point of view works. In this scene, Harry and his friends, Hermione and Ron, are looking through the library to learn more about the sorcerer’s stone :

It’s clear that this passage is written in third person: the narrator uses pronouns like “he,” “she,” and “them,” instead of first person pronouns like “I” or second person pronouns like “you.” But how do we know it’s third person limited? Well, we get Harry’s thoughts and feelings—like his curiosity about Nicholas Flamel—but no one else’s. We don’t know what Hermione and Ron are reading, or if they’re excited, nervous, or scared.

Rowling wrote all seven Harry Potter books using a third person limited point of view that made Harry the focal point. The narrator can tell us what Harry’s thinking, feeling, and seeing—as well as zoom out to tell us more about the precarious situations he finds himself in. But because the narrator is tied to Harry, they can’t give us a glimpse into other characters’ minds, nor can it show readers what’s happening in other parts of Hogwarts (where Harry isn’t) . That helps readers get to know Harry, even as it helps Rowling maintain the mystery around the sorcerer’s stone (or the chamber of secrets, or the half-blood prince, etc.).

Other Works Written in Third Person Limited Point of View The third person limited point of view is a popular perspective for writers to use, so there’s no shortage of examples! Here are a few works you might be familiar with that feature a third person limited point of view:

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Christabel”

- Eudora Welty’s The Golden Apples

- Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

- Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle In Time

What’s Next?

If you’re studying for the AP Literature exam, you’ll need to know about more literary devices than point of view. Why not check out our other comprehensive guides, like this one on personification ? The more familiar you are with literary terms, what they mean, and how to use them, the better your test score will be!

Did you know that there are two English AP tests? One is the literature exam, which focuses on literary analysis and comprehension. The second test is the language exam, which tests your ability to understand argument and write persuasively. Click here to learn more about the AP Language exam, how it differs from the literature exam, and what you need to do to knock it out of the park !

After you learn the fundamentals, the best way to prepare for an AP exam is to take practice tests. Check out this article on how to find the best AP practice exams , and learn how to use them to boost your score!

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

point of view

What is point of view definition, usage, and literary examples, point of view definition.

Point of view (POYnt of VYOO) describes the person from whom the events of the story are told. In any written work—including narratives , poems , and songs—the speaker or narrator provides the point of view.

The term is derived from the Latin punctum visus , meaning “point sight,” or where your sight limits what you can see. In literature, the point of view limits the amount of information the reader has about the events in the story. The reader can only experience events as the narrator sees and describes them. Any information the narrator is not privy to, the reader will also not be privy to.

Types of Point of View

There are three main types of point of view: first person, second person, and third person. Each type offers a different vantage point into a story’s events. Writers use them depending on how they want readers to experience the story.

First Person: I / me / mine

In first person, the story is narrated by a single character within the story. It uses the pronouns I , me , and mine . It can also use we and our if the narrator is part of a group. This offers the most limited view of events because only one character’s perspective is shared. It’s also considered the easiest to write and most likely to ensure the audience empathizes with the speaker. Some stories also have different sections narrated by different characters, such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula or Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl . This is a way for authors to provide multiple interpretations of the story’s events.

Consider this example from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale , narrated by main character Offred:

I want to be held and told my name. I want to be valued, in ways that I am not; I want to be more than valuable. I repeat my former name; remind myself of what I once could do, how others saw me. I want to steal something

Second Person: You / your

Second-person narration is written as if the reader is a character. It uses the pronouns you and your . Atypical of fictional narratives, second person is often used in poetry , songs, nonfiction directional texts like cookbooks, and advertising slogans. Choose-your-own-adventure books also use second person.

Author Junot Diaz uses second person in his collection of short stories This Is How You Lose Her . Here is an example from the story “The Cheater’s Guide to Love”:

You ask everybody you know: How long does it usually take to get over it? There are many formulas. One year for every year you dated. Two years for every year you dated. It’s just a matter of will power: The day you decide it’s over, it’s over. You never get over it.

Third Person: He / she / they / their

Stories in third person are told from an authorial point of view outside the story, not a character within it. Most published books are written in third person, as it offers the most objective view of a story’s characters and events.

There are multiple types of third-person narratives.

Third Person Omniscient

This is where the narrator knows and shares the thoughts, feelings, and actions of all characters. Omniscient narrators can jump in and out of any character’s inner dialogue, depending on how it suits the narrative’s flow. However, not all thoughts, feelings, or actions are revealed chronologically—or even at all.

Lord of the Flies by William Golding is an example of a third-person omniscient narrative. The narrator is not a character, so they can tell the reader what the boys on the island are thinking and feeling at any moment.

The fair boy said this solemnly; but then the delight of a realized ambition overcame him. In the middle of the scar he stood on his head and grinned at the reversed fat boy.

“No grownups!”

Third Person Cinematic

This is technically a subset of third person omniscient. While omniscient narrators describe how characters feel at any given moment, cinematic third-person narrators refrain from revealing characters’ inner thoughts. Instead, the scene and actions are described solely in objective fact.

Some aspects of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring uses third-person cinematic storytelling. In this example, Tolkien provides a wide-lens view of the wizard Gandalf’s arrival without providing any character’s thoughts:

An old man was driving all alone. He wore a tall pointed blue hat, a long grey cloak, and a silver scarf. He had a long white beard and bushy eyebrows that stuck out beyond the brim of his hat. Small hobbit-children ran after the card all through Hobbiton and right up the hill.

Third Person Limited

From this point of view, the narrator only describes the thoughts and feelings of one character at a time. Though, just as in first-person narration, writers may have the limited narrator switch between different characters’ perspectives.

George Orwell’s 1984 is a famous third-person limited book. It follows protagonist Winston Smith, and though there are many characters, the narrator never discloses their thoughts.

What can you do, thought Winston, against the lunatic who is more intelligent than yourself, who gives your arguments a fair hearing and then simply persists in his lunacy?

Why Writers Use Each Point of View

Each point of view type has advantages depending on the story a writer is telling. The primary factor is how close a writer wants the audience to feel to the narrator and the characters.

Uses for First-Person Narration

Writers use first person to create an explicit connection between the reader and narrator. With this point of view, the reader inherently roots for and empathizes with the narrator because the narrator is a character. Because the reader can experience the narrator’s thoughts and emotions, the reader is more likely to invest in the story being told.

This narrative structure also lends itself to clarity because the reader doesn’t need to piece together the narrative. However, there are instances where first-person narratives can confuse or complicate the story being told. This can be found in literary works with multiple narrators, as in As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner, or an unreliable narrator, as in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the Underground .

Unreliable First-Person Narration

When a story has an unreliable narrator, the narrator’s thoughts or opinions cannot be trusted often because of a certain bias or character flaw. Writers typically use this type of character to force readers to question their preconceived notions or assumptions about the story and its characters. They also use this technique to make a distinction between objective truth, which is undeniably factual, and narrative truth, which covers events that may not have actually happened but still have meaning and importance.

While primarily an aspect of first-person narration, unreliable narrators can also be found in second-person and third-person omniscient stories. This technique is used in film, where audiences are shown events that are later revealed to be inaccurate.

Examples of unreliable narrators in literature include J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye , where narrator and protagonist Holden Caulfield is a self-proclaimed liar, and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby , where narrator Nick Carraway is biased both by his reverence for the titular Jay Gatsby as well as his distaste for other characters in the novel.

Movies with unreliable narrators include the 2000 film Memento , where events are muddled by the protagonist’s inability to make new memories, and the 1995 The Usual Suspects , where Roger Kint is masking his true identity from the police.

Uses for Second-Person Narration

Writers use second-person narration to lend a sense of immediacy and urgency to the story and the action. It puts the reader directly into the action, causing them to feel invested because it’s as if the story is happening to them. Second person can also be read as a command or explicit direction, which is why it is the point of view writers use for instructional texts.

Uses for Third-Person Narration

Because there are different types of third-person narration, each one serves a distinct function in stories.

Uses for Third Person Omniscient

Third person omniscient allows writers to convey many perspectives without losing trustworthiness or authority. The reader understands that the story’s events are being fully contextualized because the narrator has access to all the characters’ thoughts and emotions.