- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

22 Learning Organization and Organizational Performance

School of Business, Sungkyunkwan University

College of Education, University of Georgia

- Published: 08 January 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

One of the strategic ways of continuing sustainable success is becoming a learning organization, an ideal environment for securing organizational performance. This chapter begins by reviewing the literature on a learning organization and organizational performance focusing on their research context, instruments, analytic methods, and empirical findings. Then, it discusses the importance of a learning organization in promoting organizational performance, especially an organization’s capacity of connecting it to its external environment and the existence of leadership that supports learning. This chapter further addresses the stronger relationship between a learning organization and non-financial performance together with the necessity of dimensionalizing organizational performance and developing corresponding measures. Lastly, this chapter suggests methodological recommendations for future studies.

Introduction

Becoming a learning organization assists an organization to overcome the challenges in a contemporary organizational environment because of the nature of a learning organization—a learning organization can be tailored with efforts, which enables an organization to reach a hoped-for state (Örtenblad 2001 ). Abundant studies have addressed areas where an organization should make efforts, and common recommendations are as follows: a learning organization has systems that encourage and share learning across an organization (Garvin 1993 ; Goh 1998 ; McGill, Slocum, and Lei 1992 ; Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell 1991 ; Senge 1990 ; Ulrich, Jick, and Von Glinow 1993 ; Watkins and Marsick 1993 ); in addition, a learning organization has a strong sense of its external environment as well as the ability to connect to its external environment (Garvin 1993 ; Goh 1998 ; McGill et al. 1992 ; Pedler et al. 1991 ; Watkins and Marsick 1993 ). Moreover, a learning organization has leaders who support learning (Goh 1998 ; McGill et al. 1992 ; Ulrich et al. 1993 ). Lastly, a learning organization emphasizes individual- and group-level learning in addition to system-level learning (Pedler et al. 1991 ; Senge 1990 ; Ulrich et al. 1993 ; Watkins and Marsick 1993 ) and a supportive atmosphere towards learning (Gephart, Marsick, Buren, and Spiro 1996 ). By taking these approaches, an organization is able to adapt to changes and transform itself in a timely manner (Watkins and Marsick 1993 ).

One advantage of becoming a learning organization can be securing sustainable success (Kim, Watkins, and Lu 2017 ). Indeed, abundant studies have identified the impact of a learning organization on diverse facets in organizations, such as interpersonal trust, organizational commitment, or work engagement (Watkins and Kim 2018 ). As these outcomes form a favorable condition for facilitating performance at the organizational level, such findings can be understood in line with what March ( 1991 ) argued—learning provides a stable environment for producing performance. Although it is fairly reasonable to assume the positive consequences of a learning organization in terms of expecting improved organizational performance, yet, there is little knowledge of the dynamics between a learning organization and organizational performance (Pedler and Burgoyne 2017 ; Watkins and Kim 2018 ).

This chapter reviews studies focusing on the learning organization and organizational performance and seeks to identify relationships that underlie them. An internet-based search was used to identify academic articles for inclusion in this review. “Learning organization” and “organizational performance” were used as major keywords in the search process.

Literature Review

This section reviews the literature on the learning organization and organizational performance by focusing on research contexts, instruments, analytic methods, and empirical findings.

Research Contexts and Instruments

Studies on the learning organization and organizational performance have been conducted under different cultural settings. They started from understanding organizations in the Americas (e.g., Davis and Daley 2008 ; Hernandez 2000 ; Watkins, Milton, and Kurz 2009 ; Yang, Watkins, and Marsick 2004 ), in Asia (e.g., Laeeque and Babar 2015 ; Noubar, Rose, Kumar, and Salleh 2011 ; Shieh 2011 ; Zhou, Hu, and Shi 2015 ), and in the Middle East (e.g., Bhaskar and Mishra 2017 ; Ngah, Tai, and Bontis 2016 ). These studies have focused on diverse organizational contexts from public sectors (e.g., Bhaskar and Mishra 2017 ; Ngah et al. 2016 ; Pokharel and Choi 2015 ) to private companies (e.g., Hernandez 2000 ; Shieh 2011 ) and even multinational organizations (Shieh, Wang, and Wang 2009 ).

Regarding instruments for measuring a learning organization, studies have operationalized the concept of a learning organization by using items based on Senge ( 1990 ) (Shieh 2011 ), adopting items from Garvin, Edmondson, and Gino ( 2008 ) and Watkins and Marsick’s (1997) Dimensions of a Learning Organization Questionnaire (DLOQ) (Zhou et al. 2015 ), or applying the DLOQ to measure a learning organization (e.g., Lien, Hung, Yang, and Li 2006 ; Ngah et al. 2016 ; Pokharel and Choi 2015 ; Yang et al. 2004 ; Yu and Chen 2015 ). The items based on Senge ( 1990 ) represent the following five fundamental components: personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, team learning, and system thinking. The items of Garvin et al. (2008) measure the degree to which the learning environment, the learning process, and leadership reinforce learning. Watkins and Marsick’s DLOQ is a questionnaire that includes items capturing the following seven dimensions: continuous learning opportunities, dialogue and inquiry, team learning, systems to capture and share learning, empowerment, connectivity to the environment, and strategic leadership for learning. Also, the DLOQ consists of perceptual organizational performance items.

Most studies examined organizational performance as an outcome variable. These studies have focused on organizational financial performance as well as non-financial performance, such as innovation or satisfaction. In order to measure organizational performance, these studies have adopted objective measures, such as sales turnover or return on assets (Ngah et al. 2016 ; Zhou et al. 2015 ), subjective measures, such as perceptual financial performance and innovation capability (Shipton, Zhou, and Mooi 2013 ; Zhou et al. 2015 ), and used a combination of several indicators to measure organizational performance (Kontoghiorghes, Awbre, and Feurig 2005 ; Shieh 2011 ), or the DLOQ (e.g., Jain and Moreno 2015 ; Watkins et al. 2009 ; Yang et al. 2004 ) depending on their research purpose and context.

Analytic Methods and Empirical Findings

Studies have hypothesized that a learning organization influences the organizational performance. In order to test such a hypothesized relationship, many studies applied correlation or regression analysis, and a few studies performed structural equation modeling (Kim et al. 2017 ; Ngah et al. 2016 ; Pokharel and Choi 2015 ).

Studies which applied correlation analysis have found a significant correlation between the two (e.g., Davis and Daley 2008 ; Shieh 2011 ; Watkins et al. 2009 ; Yang et al. 2004 ). Correlation analysis produces an association coefficient called correlation that describes the degree to which two variables are related. For different types of data, there are different types of correlation, among which the Pearson’s correlation for two continuous variables is the most popular one. A correlation ranges from −1.0 (perfect negative relationship) to 1.0 (perfect positive relationship). Studies that adopted the DLOQ showed correlations ranging from 0.10 to 0.63 for financial performance and 0.22 to 0.73 for knowledge performance (e.g., Davis and Daley 2008 ; Hernandez 2000 ; Watkins et al. 2009 ; Yang et al. 2004 ; Zhang, Zhang, and Yang 2004 ). More specifically, these studies have shown that an organization’s ability to connect to its external environment and the presence of leaders who support learning tend to produce a higher correlation. Shieh ( 2011 ) used items based on Senge ( 1990 ) and Chien ( 2004 ) to measure a learning organization and organizational performance, respectively. This study also reported that a learning organization is highly correlated to organizational performance by exhibiting correlations higher than 0.80.

As correlation does not imply causation, studies using regression analysis have provided evidence that a learning organization is able to predict organizational performance. Regression analysis is a powerful statistical method to examine the causal effects between two or more variables of interest. In other words, it examines the influence of one or more independent variables (or causes, here, learning organization) on a dependent variable (or an effect, here, organizational performance). More specifically, it helps to explain the variation in organizational performance given the change in learning organizations, or to predict the organizational performance in the future by changing learning organizations. Applying this regression analysis, studies have investigated how much of the variability observed in organizational performance can be explained by the seven learning organization dimensions of the DLOQ (Bhaskar and Mishra 2017 ; Laeeque and Babar 2015 ; Noubar et al. 2011 ; Rose, Salleh, and Kumar 2006 ). Empirical findings of these studies include the following: Rose et al. (2006) showed that the team learning, system connection, and leadership dimensions explain 53 percent of the variance in financial performance; the dialogue and inquiry, embedded systems, and leadership dimensions explain 59 percent of variance in knowledge performance in the MSC in Malaysia ( N = 208). Kumar and Idris ( 2006 ) demonstrated that 41 percent of the variance in knowledge performance is accounted for by team learning, system connection, and leadership dimensions in educational institutions in Malaysia ( N = 235). Yu and Chen ( 2015 ) reported that the continuous learning, system connection, and leadership dimensions explain 41 percent of the variance in universities and college libraries in Taiwan, China ( N = 478). Noubar et al. (2011) revealed that the seven learning organization dimensions jointly explain 27 and 34 percent of the variance in financial and knowledge performance, respectively, when analyzing organizations in Malaysia ( N = 218). Bhaskar and Mishra ( 2017 ) found that the continuous learning, dialogue and inquiry, system connection, and leadership dimensions explain 27 percent of the variance in financial performance; the system connection and leadership dimensions explain 59 percent of the variance in knowledge performance in public sector organizations in India ( N = 204).

Recently, structural equation models are becoming more and more important in the research of learning organizations. For example, studies suggested the mediating role of a learning organization in enhancing organizational performance and also the paths among the seven dimensions of the DLOQ and performance outcomes (Ngah et al. 2016 ; Pokharel and Choi 2015 ). By examining organizations in public sectors in UAE ( N = 255), Ngah et al. (2016) not only proved that a knowledge management capability on infrastructure (i.e., structure, culture, and information and communication technology) and process (i.e., from knowledge acquisition to dissemination and protection) of an organization has an effect in differentiating organizational performance, but also found that a learning organization fully mediates the relationship between the two. Pokharel and Choi ( 2015 ) stressed the importance of an organization’s ability in connecting to its external environment: this allows the organization to mediate the effect of individuals’ continuous learning and empowerment on organizational performance based on the analysis of public sector organizations in the US ( N = 331).

Thus far, this section has reviewed the literature on the learning organization and organizational performance. Researchers have conducted studies on the relationship between these two under diverse cultural and organizational settings and with different measures. By providing empirical evidence derived from correlation, regression, and structural equation modeling, these studies have supported the view that a learning organization not only correlates to but also predicts organizational performance.

Discussion and Suggestions

This section discusses the empirical findings of these studies and suggests future research directions. First, it stresses the importance of organizational capacity in connecting the organization to the environment and the role of leadership. Then, it demonstrates the implications of the findings focusing on non-financial performance followed by ideas on quantitative analytic methods for future studies.

Connectivity to the Environment and Leadership

The learning organization literature suggests that enhanced organizational performance is closely related both to an organization’s ability to connect to its external environment and to leadership (Bhaskar and Mishra 2017 ; Laeeque and Babar 2015 ; Noubar et al. 2011 ; Rose et al. 2006 ), which are the common themes that have emerged across different approaches to understanding the learning organization.

For an organization, having the capacity to align structures or strategies with its environment allows the organization to respond to changes in its environment proactively (Brown and Duguid 2001 ). A capacity that manages tensions within structures, processes, and cultures brings innovations (Tushman and O’Reilly III 1996). In this vein, a learning organization, especially its role in connecting the organization to its external environment, creates an ideal environment for the organization to enjoy improved organizational performance.

A leader also serves a critical role in creating a learning organization and expecting enhanced organizational performance (Bhaskar and Mishra 2017 ; Laeeque and Babar 2015 ; Noubar et al. 2011 ; Rose et al. 2006 ). In fact, the presence of a strategic leader for learning achieved the highest rank among the seven dimensions when analyzing published DLOQ studies (Watkins and Kim 2018 ). A recent study sought to understand the linkage between a learning organization and traditional leadership theories. Milić, Grubić-Nešić, Kuzmanović, and Delić ( 2017 ) demonstrated that the aspects of self-awareness, balanced processing, and internalized moral perspective of authentic leadership influence perceived learning organization at the organizational level either directly or indirectly through affective commitment in the manufacturing and service companies in the Republic of Serbia ( N = 502). According to them, a feeling of attachment to an organization encourages employees to be proactive in performing their tasks; the increased willingness to perform tasks beyond the assigned ones facilitates a learning organization.

Although contextual factors must be considered, the literature suggests some directions to identify how an organization can develop ideal leadership or promote adequate leader behaviors that will be a key to the success of an organization. For example, a leader is able to use learning strategically for business by exercising transformational leadership (Sahaya 2012 ). More specifically, Sahaya ( 2012 ) suggested that the individualized consideration perspective of transformational leadership, which focuses on individual talents and needs, positively influences a learning organization, and played a role in differentiating organizational performance when measuring return on assets in firms in Thailand ( N = 400).

These findings suggest that an ideal type of leadership or leader behaviors can be closer to that of a mentor or coach, especially when expecting improved organizational performance. A leader is able to exhibit individualized consideration “by listening attentively and paying close attention to their followers’ needs for achievement and growth by acting as mentors or coaches while encouraging them to take on increasingly more responsibilities in order to develop their full potential” (Avolio, Zhu, Koh, and Bhatia 2004 : 954). Recently, Kim and Watkins ( 2018 ) analyzed the six items measuring the leadership dimension of the DLOQ and found that each item produces a different coefficient and significance in terms of financial and non-financial performance. In other words, different leader behaviors are required depending on organizational contexts and their desired outcomes (e.g., whether an organization is in need of creation and enhancement of products or service, concerned about changes in its environment, or expects financial health). In spite of the differences, there is one item that is able to predict both financial and non-financial performance: “Leaders mentor and coach those they lead.”

Coaching and mentoring “leads to fostering of shared values, teamwork and an increase in morale and motivation across [an] organization resulting in greater productivity, achievement of excellent service” (Adeyemi 2011 : 370). As perceived organizational support possibly moderates the positive relationship between a learning organization and organizational performance (Siddique 2018 ), putting in place organizational support emphasizing the development of coaching and mentoring skills for a leader is, thus, suggested (Kim and Watkins 2018 ).

Non-Financial Performance

Table 22.1 shows the results of a meta-analysis of the seven dimensions of the DLOQ and organizational performance (Viechtbauer 2010 ). When analyzing the studies using the DLOQ that report Pearson’s correlation coefficients (Davis and Daley 2008 ; Hernandez 2000 ; Kim 2016 ; Watkins et al. 2009 ; Weldy and Gillis 2010 ; Wetherington and Daniels 2013 ; Yang et al. 2004 ; Zhang et al. 2004 ), ZCOR, a figure that better reflects its position in the collection of all coefficients, showed that the dimensions of empowerment, connectivity to the environment, and strategic leadership for learning show a higher correlation for both financial and knowledge performance. These results are consistent with the findings of the studies reviewed earlier.

Note : CL = Continuous Learning; DI = Dialogue and Inquiry; TL = Team Learning; ES = Embedded Systems; EP = Empowered People; SC = System Connection; SL = Strategic Leadership; k (number of studies) = 8; N = 4,320; ZCOR = Fisher’s z transformation of correlation; The analysis was conducted by using the statistical software R, the Metafor package (Viechtbauer 2010 ).

The table shows that the correlations between the seven dimensions and knowledge performance are slightly higher than financial performance. These results further support the findings of the regression studies—a learning organization explains more variance in knowledge performance than financial performance (Laeeque and Babar 2015 ; Noubar et al. 2011 ; Rose et al. 2006 ). These results indicate that a learning organization can be more closely associated with non-financial performance.

Thus, there is a need for identifying dimensions of non-financial performance derived from intangible assets and facilitated by learning (Watkins and Kim 2018 ). These assets fall into one of the following four components: external relationship, people, internal structure, and property (Bontis 2001 ; Marr and Adams 2004 ). Although the knowledge performance items of the DLOQ capture the intangible assets considerably, a potential dimension can be related to adaptive performance that includes factors like responding to changes, seizing new opportunities, and handling unexpected situations, which assists an organization in positioning itself better in its environment (Kontoghiorghes et al. 2005 ; Kim 2016 ). Dimensionalizing and measuring organizational performance is a complex task. Nonetheless, identifying performance dimensions, developing solid corresponding measures, and validating them broaden the intellectual horizon of a learning organization (Watkins and Kim 2018 ).

Unveiling mechanisms between financial and non-financial intangible performance in tandem with a learning organization can be another avenue for future research. Studies have shown that a learning organization impacts both intangible and tangible organizational performance. Intangible performance leads to tangible performance from a long-term perspective (Kaplan and Norton 1992 ; March 1991 ). Recently, studies consistently showed a learning organization invisibly promotes intangible performance, which is eventually realized as increased tangible performance, a critical outcome for the continuous survival of an organization (Kim 2016 ; Kim et al. 2017 ). More empirical studies are recommended to verify such findings (Watkins and Kim 2018 ).

Quantitative Analytic Methods

Applying diverse quantitative methods allows researchers to address research questions in a more robust and precise manner, but it can be seen that the literature on organizational performance has mostly used a correlation and regression analysis with a few exceptions. Thus, future research is encouraged to use diverse analytic methods. Some methodological suggestions and recommendations in conducting learning organization studies are as follows.

To identify dimensions and develop measures, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) can be helpful to uncover the underlying latent structure of non-financial performance. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) can be followed to confirm the hypothesized factor structure identified by EFA and to test whether the data fit a hypothesized measurement model, which is based on theory or previous empirical research. Thus, EFA and CFA are strongly suggested for the development of new measures and evaluation of the psychometric properties of new and existing measures (Harrington 2009 ).

As a special type of CFA, item response theory (IRT) can be used for test items with categorical outcomes or responses, such as binary or polychromous, by applying transformations (mainly logistic or probit) (Baker and Kim 2004 ; Embretson and Reise 2013 ). Similar to CFA, IRT can be used to model responses to test items along with the latent traits that determine how individuals or organizations react to these items (Foster, Min, and Zickar 2017 ). IRT would help to address many specific research questions, for example, to locate individuals’ or organizations’ latent levels of learning ability on an overall measure, to measure the true levels of non-financial performance in a learning organization, or to find any observed or latent factors which can explain the improvement or decrease of learning abilities or non-financial performance.

Regarding the dynamics between a learning organization and organizational performance or between financial and non-financial performance, structural equation modeling (SEM) would be appropriate. SEM can help researchers to uncover complex relationships among variables of interest. For example, SEM enables researchers to examine regression, mediating, and moderating effects simultaneously (Bowen and Guo 2012 ).

When considering the importance of interactions between individuals in enhancing organizational performance in a learning organization, social network analysis (SNA) would produce useful information to coaching or mentoring individuals as it is able to identify individuals and their expertise in a network and connections within/between groups/leaders by analyzing centrality or density within a personal network (Parise 2007 ).

When data are collected from more than one level or collected repeatedly through multiple time points/waves from the same participants, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) is recommended (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002 ). HLM, also called multi-level modeling or mixed-effect modeling, decomposes the variation of outcome variables into different levels, such as within organization and between organizations. For nested organizations/units, for example, when individuals are nested within organizations, variations come from not only observations/measures but also hierarchical structures (e.g., individual, team, organization). HLM can help to understand how certain variables/constructs are observed/measured and interpreted at the different level of organizations (Hox 2002 ). For longitudinal data, HLM can help not only to understand the intra-individual or intra-organization trend of the change of performance but also to investigate the inter-individual or inter-organization differences (Fitzmaurice, Davidian, Verbeke, and Molenberghs 2008 ; Hedeker and Gibbons 2006 ; Singer and Willett 2003 ). In this regard, HLM allows researchers to infer their findings in organizational performance in a more precise manner.

Although more empirical evidence is needed, the literature reviewed in this chapter suggests that an organization that is flexible and copes with constant changes secures the success of the organization. Under different organizational contexts, studies have shown that a learning organization can play a significant role in enhancing organizational performance. The findings of these studies claim that a learning organization not only is positively associated with but also significantly predicts such performance.

For future studies on the learning organization and organizational performance, this chapter suggests ways of measuring them as follows. One way is adopting existing measures (see Moilanen 2001 for diagnostic instruments of a learning organization). For example, the DLOQ has items measuring a learning organization and perceptual organizational performance. Together with the analytic methods addressed earlier, this approach will provide a helpful source for understanding how a learning organization is connected to organizational performance. Another way is linking a learning organization with actual indicators, especially when interested in tangible performance. Such measures can be return on investment, return on equity, return on assets, earnings per share, and percentage of sales from new products (Davis and Daley 2008 ; Ellinger, Ellinger, Yang, and Howton 2002 ). Choosing a measure of a learning organization, identifying adequate and quantifiable performance indices according to the context where an organization is situated, and examining the correlation, causal, or other relationship between these two will generate useful information. Of course, a combination of perceptual and objective measures will bring more information in interpreting the linkage between a learning organization and organizational performance from a diverse perspective.

Last but not least, an organization should take a look at its ability to connect to its external environment and the leadership that supports learning as they have a greater potential in altering organizational outcomes. Identifying dimensions of and relationships between organizational performance, developing concrete measures, and applying sophisticated analytic methods will contribute to the advancement in knowledge about learning organizations.

Adeyemi, S. 2011 . “ Enhancing Organizational Performance through Effective Mentoring: Chapter 28. ” IFE PsychologiA: An International Journal 1: pp. 366–78.

Google Scholar

Avolio, B. , W. Zhu , W. Koh , and P. Bhatia . 2004 . “ Transformational Leadership and Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Moderating Role of Structural Distance. ” Journal of Organizational Behavior 25 (8): pp. 951–68.

Baker, F. B. , and S.-H. Kim . 2004 . Item Response Theory: Parameter Estimation Techniques . New York: CRC Press.

Google Preview

Bhaskar, A. U. , and B. Mishra . 2017 . “ Exploring Relationship between Learning Organizations Dimensions and Organizational Performance. ” International Journal of Emerging Markets 12 (3): pp. 593–609.

Bontis, N. 2001 . “ Managing Organizational Knowledge by Diagnosing Intellectual Capital: Framing and Advancing the State of the Field. ” International Journal of Technology Management 18 (5–8): pp. 433–62.

Bowen, N. , and S. Guo . 2012 . Structural Equation Modeling: Pocket Guides to Social Research Methods . New York: Oxford University Press.

Brown, J. S. , and P. Duguid . 2001 . “ Knowledge and Organization: A Social-Practice Perspective. ” Organization Science 12 (2): pp. 198–213.

Chien, M. H. 2004 . “ A Study to Improve Organizational Performance: A View from SHRM. ” Journal of American Academy of Business 4 (1/2): pp. 289–91.

Davis, D. , and B. J. Daley . 2008 . “ The Learning Organization and Its Dimensions as Key Factors in Firms’ Performance. ” Human Resource Development International 11 (1): pp. 51–66.

Ellinger, A. D. , A. E. Ellinger , B. Yang , and S. W. Howton . 2002 . “ The Relationship between the Learning Organization Concept and Firms’ Financial Performance: An Empirical Assessment. ” Human Resource Development Quarterly 13 (1): pp. 5–22.

Embretson, S. E. , and S. P. Reise . 2013 . Item Response Theory . Mahwah, NJ: Psychology Press.

Fitzmaurice, G. , M. Davidian , G. Verbeke , and G. Molenberghs (eds.). 2008 . Longitudinal Data Analysis . Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Foster, G. C. , H. Min , and M. J. Zickar . 2017 . “ Review of Item Response Theory Practices in Organizational Research: Lessons Learned and Paths Forward. ” Organizational Research Methods 20 (3): pp. 465–86.

Garvin, D. A. 1993 . “ Building a Learning Organization. ” Harvard Business Review 71 (4): pp. 78–91.

Garvin, D. A. , A. C. Edmondson , and F. Gino . 2008 . “ Is Yours a Learning Organization? ” Harvard Business Review 86 (3): pp. 109–16.

Gephart, M. A. , V. J. Marsick , M. E. Buren , and M. S. Spiro . 1996 . “ Learning Organizations Come Alive. ” Training & Development 50 (12): pp. 34–46.

Goh, S. C. 1998 . “ Toward a Learning Organization: The Strategic Building Blocks. ” SAM Advanced Management Journal 63 (2): pp. 15–22.

Harrington, D. 2009 . Confirmatory Factor Analysis . New York: Oxford University Press.

Hedeker, D. , and R. D. Gibbons . 2006 . Longitudinal Data Analysis . Vol. 451. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Hernandez, M. 2000. “The Impact of the Dimensions of the Learning Organization on the Transfer of Tacit Knowledge Process and Performance Improvement within Private Manufacturing Firms in Colombia.” PhD thesesis, The University of Georgia. Retrieved from ProQuest (UMI: 9994101).

Hox, J. J. 2002 . Multilevel Analysis Techniques and Applications . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jain, A. K. , and A. Moreno . 2015 . “ Organizational Learning, Knowledge Management Practices and Firm’s Performance: An Empirical Study of a Heavy Engineering Firm in India. ” The Learning Organization 22 (1): pp. 14–39.

Kaplan, R. S. , and D. P. Norton . 1992 . “ The Balanced Scorecard: Measures that Drive Performance. ” Harvard Business Review 70 (1): pp. 71–9.

Kim, K. 2016. “The Impact of Learning Organizations on Knowledge Performance, Adaptive Performance, and Financial Performance.” PhD thesis, Athens, GA: University of Georgia.

Kim, K. , and K. E. Watkins . 2018. “Leader Behaviors and Intangible Performance.” Paper presented at the University Forum for Human Resource Development Conference 2018. Newcastle.

Kim, K. , K. E. Watkins , and Z. L. Lu . 2017 . “ The Impact of a Learning Organization on Performance: Focusing on Knowledge Performance and Financial Performance. ” European Journal of Training and Development 41 (1): pp. 177–93.

Kontoghiorghes, C. , S. M. Awbre , and P. L. Feurig . 2005 . “ Examining the Relationship between Learning Organization Characteristics and Change Adaptation, Innovation, and Organizational Performance. ” Human Resource Development Quarterly 16 (2): pp. 185–212.

Kumar, N. , and K. Idris . 2006 . “ An Examination of Educational Institutions’ Knowledge Performance: Analysis, Implications and Outlines for Future Research. ” The Learning Organization 13 (1): pp. 96–116.

Laeeque, S. H. , and S. F. Babar . 2015 . “ Learning Organization as a Strategy to Improve Performance of Pakistani Hospitals. ” Journal of Managerial Sciences 9 (2): pp. 256–66.

Lien, B. Y.-H. , R. Y.-Y. Hung , B. Yang , and M. Li . 2006 . “ Is the Learning Organization a Valid Concept in the Taiwanese Context? ” International Journal of Manpower 27 (2): pp. 189–203.

McGill, M. E. , J. W. Slocum , and D. Lei . 1992 . “ Management Practices in Learning Organizations. ” Organizational Dynamics 21 (1): pp. 5–17.

March, J. G. 1991 . “ Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. ” Organization Science 2 (1): pp. 71–87.

Marr, B. , and C. Adams . 2004 . “ The Balanced Scorecard and Intangible Assets: Similar Ideas, Unaligned Concepts. ” Measuring Business Excellence 8 (34): pp. 18–27.

Milić, B. , L. Grubić-Nešić , B. Kuzmanović , and M. Delić . 2017 . “ The Influence of Authentic Leadership on the Learning Organization at the Organizational Level: The Mediating Role of Employees’ Affective Commitment. ” Journal of East European Management Studies 22 (1): pp. 9–38.

Moilanen, R. 2001 . “ Diagnostic Tools for Learning Organizations. ” The Learning Organization 8 (1): pp. 6–20.

Ngah, R. , T. Tai , and N. Bontis . 2016 . “ Knowledge Management Capabilities and Organizational Performance in Roads and Transport Authority of Dubai: The Mediating Role of Learning Organization. ” Knowledge and Process Management 23 (3): pp. 184–193.

Noubar, H. , R. C. Rose , N. Kumar , and L. M. Salleh . 2011 . “ Learning Culture to Organizational Breakthroughs in Malaysian Companies. ” Economics and Management 16: pp. 852–8.

Örtenblad, A. 2001 . “ On Differences between Organizational Learning and Learning Organization. ” The Learning Organization 8 (3): pp. 125–33.

Parise, S. 2007 . “ Knowledge Management and Human Resource Development: An Application in Social Network Analysis Methods. ” Advances in Developing Human Resources 9 (3): pp. 359–83.

Pedler, M. , and J. Burgoyne . 2017 . “ Is the Learning Organization Still Alive? ” The Learning Organization 24 (2): pp. 119–26.

Pedler, M. , J. Burgoyne , and T. Boydell . 1991 . The Learning Company . Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill.

Pokharel, M. P. , and S. O. Choi . 2015 . “ Exploring the Relationships between the Learning Organization and Organizational Performance. ” Management Research Review 38 (2): pp. 126–48.

Raudenbush, S. W. , and A. S. Bryk . 2002 . Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods , vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rose, R. C. , A. Salleh , and N. Kumar . 2006 . “ Learning Culture and Performance Outcomes: Evidence from Malaysian Organizations. ” Management & Change 10 (2): pp. 131–52.

Sahaya, N. 2012 . “ A Learning Organization as a Mediator of Leadership Style and Firms’ Financial Performance. ” International Journal of Business and Management 7 (14): pp. 96–113.

Senge, P. M. 1990 . The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization . New York: Doubleday.

Shieh, C.-J. 2011 . “ Study on the Relations among the Customer Knowledge Management, Learning Organization, and Organizational Performance. ” The Service Industries Journal 31 (5): pp. 791–807.

Shieh, C.-J. , I.-M. Wang , and F.-J. Wang . 2009 . “ The Relationships among Cross-Cultural Management, Learning Organization, and Organizational Performance in Multinationals. ” Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 37 (1): pp. 15–30.

Shipton, H. , Q. Zhou , and E. Mooi . 2013 . “ Is There a Global Model of Learning Organizations? An Empirical, Cross-Nation Study. ” International Journal of Human Resource Management 24 (12): pp. 2278–98.

Siddique, M. C. 2018 . “ Learning Organization and Firm Performance: Making a Business Case for the Learning Organization Concept in the United Arab Emirates. ” International Journal of Emerging Markets 13 (4): pp. 689–708.

Singer, J. D. , and J. B. Willett . 2003 . Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence . New York: Oxford University Press.

Tushman, M. L. , and C. A. O’Reilly III . 1996 . “ Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change. ” California Management Review 38 (4): pp. 8–29.

Ulrich, D. , T. Jick , and M. A. Von Glinow . 1993 . “ High-Impact Learning: Building and Diffusing Learning Capability. ” Organizational Dynamics 22 (2): pp. 52–66.

Viechtbauer, W. 2010 . “ Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the Metafor Package. ” Journal of Statistical Software 36 (3): pp. 1–48.

Watkins, K. E. , and K. Kim . 2018 . “ Current Status and Promising Directions for Research on the Learning Organization. ” Human Resource Development Quarterly 29 (1): pp. 15–29.

Watkins, K. E. , and V. J. Marsick . 1993 . Sculpting the Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art and Science of Systemic Change . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Watkins, K. E. , and V. J. Marsick . 1997 . Dimensions of the Learning Organization Questionnaire . Warwick, RI: Partners for the Learning Organization.

Watkins, K. E. , J. Milton , and D. Kurz . 2009 . “ Diagnosing the Learning Culture in Public Health Agencies. ” International Journal of Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning 2 (1): pp. 65–81.

Weldy, T. G. , and W. E. Gillis . 2010 . “ The Learning Organization : Variations at Different Organizational Levels.” The Learning Organization 17 (5): pp. 455–470.

Wetherington, J. M. , and K. M. Daniels . 2013 . “ The Relationship between Learning Organization Dimensions and Performance in the Nonprofit Sector. ” Journal for Nonprofit Management 16 (1): pp. 90–107.

Yang, B. , K. E. Watkins , and V. J. Marsick . 2004 . “ The Construct of the Learning Organization: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. ” Human Resource Development Quarterly 15 (1): pp. 31–55.

Yu, T. , and C.-C. Chen . 2015 . “ The Relationship of Learning Culture, Learning Method, and Organizational Performance in the University and College Libraries in Taiwan. ” Libri 65 (1): pp. 1–14.

Zhang, D. , Z. Zhang , and B. Yang . 2004 . “Learning Organization in Mainland China: Empirical Research on its Application to Chinese State-Owned Enterprises.” International Journal of Training and Development 8 (4): pp. 258–73.

Zhou, W. , H. Hu , and X. Shi . 2015 . “ Does Organizational Learning Lead to Higher Firm Performance? An Investigation of Chinese Listing Companies. ” The Learning Organization 22 (5): pp. 271–88.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, building organizational resilience through organizational learning: a systematic review.

- 1 Department of Technology and Safety, UiT the Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway

- 2 Department of Leadership and Organisation, Kristiania University College, Oslo, Norway

With organizational environments becoming increasingly complex and volatile, the concept of “organizational resilience” has become the “new normal”. Organizational resilience is a complex and multidimensional concept which builds on the myriad of capabilities that an organization develops during its lifecycle. As learning is an inherent and essential part of these developments, it has become a central theme in literature on organizational resilience. Although organizational resilience and organizational learning are inherently interrelated, little is known of the dynamics of effective learning that may enhance organizational resilience. This study explores how to achieve organizational learning that can serve to promote organizational resilience. Our aim is to contribute to a more comprehensive knowledge of the relation between organizational resilience and organizational learning. We present the results of a systematic literature review to assess how organizational learning may make organizations more resilient. As both organizational resilience and organizational learning are topics of practical importance, our study offers a specifically targeted investigation of this relation. We examine the relevant literature on organizational learning and resilience, identifying core themes and the connection between the two concepts. Further, we provide a detailed description of data collection and analysis. Data were analyzed thematically using the qualitative research software NVivo. Our review covered 41 empirical, 12 conceptual and 6 literature review articles, all indicating learning as mainly linked to adaptation capabilities. However, we find that learning is connected to all three stages of resilience that organizations need to develop resilience: anticipation, coping, and adaptation. Effective learning depends upon appropriate management of experiential learning, on a systemic approach to learning, on the organizational ability to unlearn, and on the existence of the context that facilitates organizational learning.

Introduction

With organizational environments becoming more and more complex and volatile, the concept of “organizational resilience” (OR) has become increasingly significant for practice and research. OR is here understood as the organization's “ability to anticipate potential threats, to cope effectively with adverse events, and to adapt to changing conditions” ( Duchek, 2020 , p. 220). Thus, anticipation, coping, and adaptation represent three stages of OR. Further, the literature indicates that OR is an essential organizational meta-capability for the success of modern organizations ( Parsons, 2010 ; Näswall et al., 2013 ; Britt et al., 2016 ; Suryaningtyas et al., 2019 ). OR has indeed become the “new normal” ( Linnenluecke, 2017 ) regarding organizational survival as well as recovery and successful re-emergence after disruptions. Understanding OR is therefore more important than ever ( Ruiz-Martin et al., 2018 ). However, OR is still an emerging field ( Ma et al., 2018 )—and a key question that remains unanswered is how to achieve it ( Boin and Lodge, 2016 ; Chen R. et al., 2021 ).

Research is explicit on the complexity and multidimensional nature of OR: it is associated with an organization's capabilities to learn, adapt, and self-organize ( Linnenluecke and Griffiths, 2010 ), where learning is an inherent and essential element ( Boin and van Eeten, 2013 ). This links OR to learning processes (see, e.g., Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011 ; Rodríguez-Sánchez and Vera Perea, 2015 ), where learning has become a common theme in resilience literature. Khan et al. (2019 , p. 18) argue, “[o]rganizational learning capability is positively related to building and sustaining organizational resilience capability.” While OR is defined at the organizational level, the inherent learning is organizational learning (OL), understood as an “[ongoing] social process of individuals participating in situated practices that reproduce and expand organizational knowledge structures and link multiple levels of OL” ( Popova-Nowak and Cseh, 2015 , p. 318). Furthermore, research has noted the similarities between OR and OL ( Sitkin, 1992 ; Linnenluecke and Griffiths, 2010 ), as both require routines, values, models, and capabilities essential for organizations facing uncertainty. OR has also been defined as an outcome of organizational learning ( Sitkin, 1992 ; Sutcliffe and Vogus, 2003 ), suggesting that organizational learning capability may be enhanced by OR ( Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2021 ). However, OR is also a process ( Boin et al., 2010 ) that facilitates OL and feeds organizational self-development over time ( Lombardi et al., 2021 ). This makes OL both an important precondition for OR which relies on past learning, and an outcome of it that fosters future learning ( Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007 ). OR and OL may therefore reinforce each other.

Although OR and OL are inherently interrelated, our understanding of the dynamics of effective learning is limited ( Antonacopoulou and Sheaffer, 2014 ), and further study is needed of the relationship between organizational learning and resilience ( Mousa et al., 2017 , 2020 ; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2021 ). Further research on learning connected to OR is needed to understand “the character of this learning and what specific resources give rise to it” ( Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007 , p. 3421). Moreover, investigation is needed of what triggers learning and corresponding processes and exploring of the effective learning strategies that allow resilient organizations to avoid pathological learning cycles ( Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007 ). Our aim with this study is therefore to contribute to more comprehensive knowledge on the relationship between OR and OL and to further explore the relationship between them by asking the research question: How to improve organizational learning to make organizations more resilient?

Theoretical Framework

OL assumes interaction of its multiple levels of analysis, including the individual, group, organizational, and inter-organizational levels ( Lundberg, 1995 ; Örtenblad, 2004 ; Popova-Nowak and Cseh, 2015 ). Being a social process, OL is embedded in everyday organizational practice when individuals acquire, produce, reproduce, and expand organizational knowledge ( Lave and Wenger, 1991 ; Gherardi et al., 1998 ; Gherardi and Nicolini, 2002 ; Gherardi, 2008 ; Chiva et al., 2014 ). This individual knowledge, either explicit or tacit ( Cook and Yanow, 1993 ), must become part of organizational repository that includes tools, routines, social networks and transactive memory systems ( Huber, 1991 , p. 89–90; Walsh and Ungson, 1991 ; Argote and Ingram, 2000 ; Argote, 2011 ). OL directly affects organizations facing turbulence ( Baker and Sinkula, 1999 ) and involves “the extraction of positive lessons from the negativity of life” ( Giustiniano et al., 2018 , p. 133) that are useful to the whole organization. OL will therefore directly affect how resilient organizational performance is ( Giustiniano et al., 2018 ).

Learning is emergent in nature ( Antonacopoulou and Sheaffer, 2014 ). As a continuous process, OL implies accomplishment of specific steps. However, what those steps are varies, though with certain overlaps, across the literature (see, e.g., Huber, 1991 ; Argyris and Schön, 1996 ; Crossan et al., 1999 ; Lawrence et al., 2005 ; Jones and Macpherson, 2006 ; Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ; Argote et al., 2020 ). Further, OL may vary in complexity and outcomes. At the lower (single-loop) level, OL results in detection and correction of errors “without questioning or altering the underlying values of the system” ( Argyris and Schön, 1978 , p. 8). At the higher (double-loop) level of learning, “errors are corrected by changing the governing values and then the actions” ( Argyris, 2002 , p. 206). Triple-loop learning (deutero-learning) enables organizations to learn about their own learning processes ( Argyris and Schön, 1978 , 1996 ). OL may be exploratory—associated with “search, variation, risk taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery and innovation” ( March, 1991 , p. 71), or exploitive—utilizing the “old certainties” ( March, 1991 , p. 71). The trade-off between the two is a key concern of studies of adaptive processes; organizations need to have an appropriate balance between these strategies ( Levinthal and March, 1993 ) to maintain “ambidexterity” ( Lavie et al., 2010 ). Importantly, OL is not necessarily always a conscious or intentional effort, neither does it imply behavioral change ( Hernes and Irgens, 2013 ) or always increase the learner's effectiveness (even potential effectiveness); finally, it does not always lead to true knowledge, as organizations “can incorrectly learn, and they can correctly learn that which is incorrect” ( Huber, 1991 , p. 89).

Organizations struggle to implement OL ( Lipshitz et al., 2002 ; Reich, 2007 ; Garvin et al., 2008 ; Taylor et al., 2010 ; Antonacopoulou and Sheaffer, 2014 ) due to a wide range of barriers (see, e.g., Schilling and Kluge, 2009 ). Productive OL is complex and relies on the interaction of various facets—cultural, psychological, policy, and contextual ( Lipshitz et al., 2002 ; see also Garvin, 1993 ). These interactions may produce differing configurations and will vary across organizations. Experience has a special role as a key prerequisite for OL, but experience is extremely diverse in nature ( Argote and Todorova, 2007 ; Argote, 2011 ; Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ) and its relevance is only partial ( Weick and Sutcliffe, 2015 ). In order for experience to be a “good teacher” ( March, 2010 ) organizations must understand its nature and how different types of experience interplay ( Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ). The relationship between the experience and learning processes and outcomes is moderated by context ( Argote, 2011 , p. 441). Effective OL relies on a suitable context ( Antonacopoulou and Chiva, 2007 , p. 289) that can be complex and multidimensional ( Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 ): inter alia , external organizational environments, organizational culture, strategy and structure, power relationship within the organization and inter-organizational processes and interactions. The contextual components through which learning occurs are active, whereas others that shape the active context are latent (see Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011 for details).

Thus, OR is founded on learning processes (assessment, sense making, distilling lessons learned and integration of new understandings into existing practice) that are embedded in organizational routines ( Powley and Cameron, 2020 ) that penetrate all stages of OR ( Duchek, 2020 ). Achieving OR requires commitment and studying this commitment implies an enquiry into organizational learning, knowledge, and capability development ( Weick and Sutcliffe, 2015 , p. 108). Research has noted that different types of resilience associate with different learning strategies: adaptive resilience has been associated with single-loop learning ( Lombardi et al., 2021 , p. 2). In contrast, reactive resilience refers to the ability to view disruptions as sources of learning and growth at various organizational levels, where organizations must adopt new practices based on their experience, resulting in a double-loop learning. Resilience also entails a process of deutero-learning or “learning to learn” ( Andersen, 2016 ), thus requiring a completely new experimentation approach. OR is enhanced when organizations build routines that can facilitate OL. The major challenge for an organization that aims at enabling resilience is to establish the right learning routines (see, e.g., Kayes, 2015 ): that is to say, those that achieve effective/productive OL.

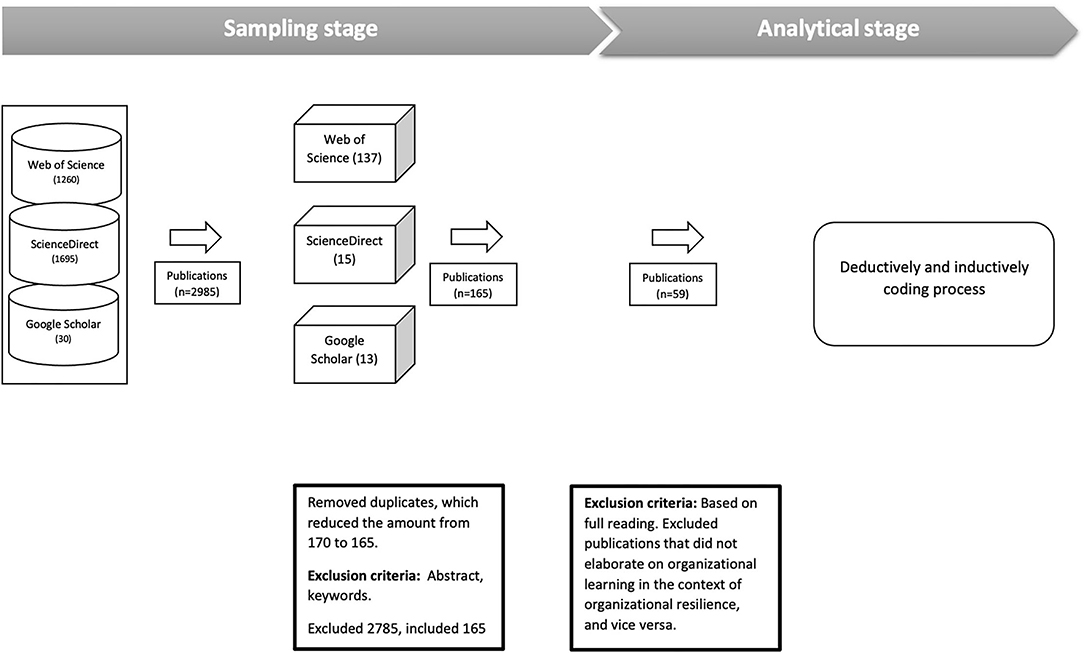

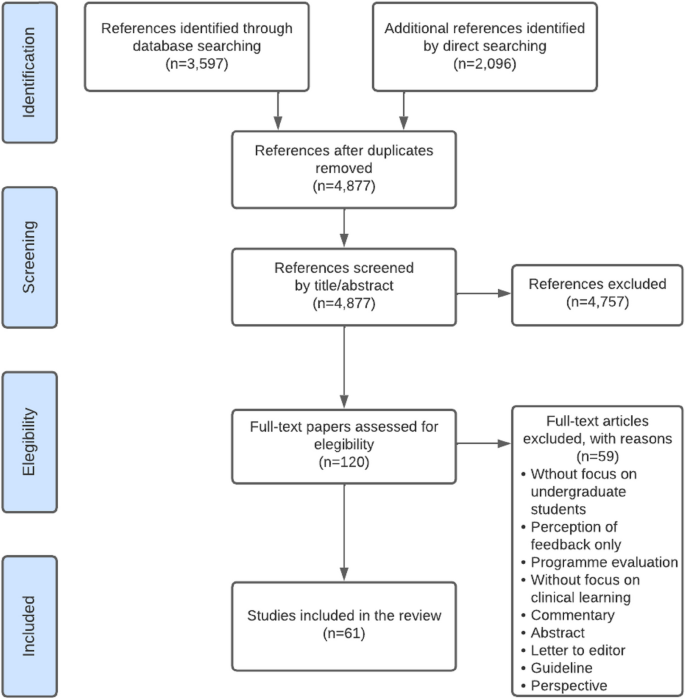

A systematic literature review (SLR) was chosen since it facilitates gathering of a wide range of relevant sources ( Crossan and Apaydin, 2010 ) and ensures clarity of inclusion and exclusion criteria ( Mackay and Zundel, 2017 )—important when, as with OR, intellectual coherence or a standard theoretical framework is lacking ( Liñán and Fayolle, 2015 ). Our review was outcomes-oriented, aiming to identify “central issues” ( Cooper, 1988 , p. 109); relevant literature was retrieved through an exhaustive review with selective citation, to consider all relevant publications for the research question. SLR involves two stages: a sampling and an analytical stage ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Methodological steps for literature review (source: the authors).

Conducting the Review

The sampling stage.

Our initial search criteria were broad to include as many relevant results as possible. To obtain an overview of the available literature, the following databases were used: Science Direct, Web of Knowledge (Search in the core collection) and Google Scholar (for the latest publications and gray literature). 1 As Google Scholar is a compilation of records from other databases ( Kugley et al., 2017 ) several articles had already been identified by Science Direct and Web of knowledge. All databases are frequently used by researchers of various disciplines ( Xiao and Watson, 2019 ). The literature search was performed by the first author, in the period March–May 2021, covering publications between 1900 and 2021. A diary was made to keep record of the results, with search dates, search strings and results.

Search strings were developed by applying the keywords “organizational resilience” and “organizational learning”. In Web of Knowledge, the Boolean operator (AND) was applied together with truncation symbol of the asterisk to include all forms of the words [TS = (resilien * AND organi * AND learning)]. The same keywords were applied in Science Direct; as both UK and US spelling variants are supported, there was no need for truncation symbol. Google Scholar offers limited search terms options, and the selection is not as transparent as Web of Knowledge and Science Direct. However, we performed a search in Google Scholar to broaden the number of publications and ensure the latest articles from all fields and disciplines. Only the three first pages were included. The initial search performed by the first author yielded 2,985 articles. Next, the same author went through the abstracts and keywords. In cases where abstracts were not sufficiently informative, the article was read through quickly. Duplicates were removed, which reduced the number of articles from 170 to 165.

The following criteria were used in the screening process resulting in 2,985 publications:

Inclusion Criteria

1. Empirical, conceptual, and theoretically oriented publications about organizational learning within organizational resilience

2. Publications written in English

3. Article type (applied only in Science Direct): Review articles, research articles, book chapters, conference abstracts and data articles

4. Subject areas (only in Science Direct): Social sciences, environmental science, business, management and accounting, engineering

Exclusion Criteria

1. Non-academic journals

2. Publications not issued in English or Norwegian