Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Literatures review: Analysis of Safety Management System Standards

Related Papers

Proceedings of the XXII Edition Summer School “Francesco Turco” Industrial Systems Engineering

Antonio Latora

An appropriate approach to manage Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) is to develop management systems, which can integrate safety into the ordinary and overall management of the company. The Safety Management Systems (SMS) represents now the main instrument adopted in medium to large-sized companies, in order to minimize the occurrence of accidents and occupational diseases. The auditing phase allows the feedback necessary to reinforce, maintain and develop the ability to reduce risks and to ensure efficiency and effectiveness of the SMS. In addition, the correct operation of the SMS requires an information flow across the development, implementation and maintenance stages and the auditing/reviewing stage, in order to manage and control safety performances and to highlight any deviation from the safety improvement program. The aim of the research is to assess the capability of the OHS management system adopted in a medium enterprise operating in the industrial sector of soft drinks bottling. The current SMS complies with OHSAS 18001 standard requirements, but its structure is so singular that external auditors repeatedly challenged its effectiveness. The critical aspect is the assignment of priorities to safety interventions that is currently based on corrective factors applied to the medium risk level of each risk category. A multi-criteria decision process based on Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) was proposed to the company by using both the traditional AHP method and a hybrid model based on Value-AHP, which is easier to understand and to apply in the company safety management routine. A three levels hierarchy was identified by considering the priority of interventions as the general objective of the assessment, four criteria for the accounting policies and eight macro-alternatives of risk categories. The result is an integrated management system able to track all risk categories, efficiently addressing the safety improvement program.

Journal of Safety, Health, and Environmental Research

Health and safety management system (HSMS) document reviews show occupational health and safety policies as a primary system element. One way that companies operationalize tasks and communicate expectations to their employees is through their health and safety policies. As a result, policies should be visible and clearly promote desired practices. However, limited research exists on the quantity and scope of health and safety practices within company policies. In response, this study analyzed the publicly available health and safety policies of 26 mining companies to determine the quantity of health and safety practices that mining companies encourage in relation to the plan-do-check-act cycle. A thematic content analysis of the policies identified elements and practices within the text. On average, companies communicated information on about seven elements (range 1 to 14, SD = 3.49) and discussed 15 practices (range 2–34, SD = 9.13). The elements in which companies highlighted the most practices were risk management, emergency management, leadership development, and occupational health. A discussion of the policy trends shows areas that mine sites can improve upon within their plan-do-check-act cycle, in addition to encouraging the use of both leading and lagging indicators when checking and acting to manage health and safety performance.

Journal of Chemical Health and Safety

Charles Geraci

Rakesh Maharaj

In today’s environment, where financial pressures are constraining businesses worldwide, it is vital to challenge the corresponding increase in occupational risk. The focused role of the safety professional in the face of this ubiquitous economic downturn is now more important and challenging than ever. Business Managers will be scathing of business cases for safety programmes where their basis is anecdotal and corresponding investment merely for worker protection may be considered unnecessary. To overcome such perceptions, the safety professional’s ability to demonstrate a tangible relationship between improved safety and business performance is critical. Conventional arguments that present safety as a function of loss control must be challenged. Many researchers have been grappling with this since the mid 1990s according to Veltri et al (2007). Contributing to this body of knowledge, by evaluating the principles of applied systems thinking, this paper contends that the art and science involved in creating a contributory relationship between safety performance and business performance is no longer elusive.

Ikhwan Muhammad

Complex arguments continue to be articulated regarding the theoretical foundation of health and safety management system (HSMS) performance measurement. The culmination of these efforts has begun to enhance a collective understanding. Despite this enhanced theoretical understanding, however, there are still continuing debates and little consensus. The goal of the current research effort was to empirically explore common methods to HSMS performance measurement in mining organizations. The purpose was to determine if value and insight could be added into the ongoing approaches of the best ways to engage in health and safety performance measurement. Nine site-level health and safety management professionals were provided with 133 practices corresponding to 20 HSMS elements, each fitting into the plan, do, check, act phases common to most HSMS. Participants were asked to supply detailed information as to how they (1) assess the performance of each practice in their organization, or (2) would assess each practice if it were an identified strategic imperative. Qualitative content analysis indicated that the approximately 1200 responses provided could be described and categorized into interventions, organizational performance, and worker performance. A discussion of how these categories relate to existing indicator frameworks is provided. The analysis also revealed divergence in two important measurement issues; (1) quantitative vs qualitative measurement and reporting; and (2) the primary use of objective or subjective metrics. In lieu of these findings we ultimately recommend a balanced measurement and reporting approach within the three metric categories and conclude with suggestions for future research. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Syea Ghazaly

Safety Science

Peter Hasle

Emily Haas , cassandra hoebbel

Research continues to investigate barriers to managing occupational health and safety behaviors among the workforce. Recent literature argues that (1) there is a lack of consistent, multilevel communication and application of health and safety practices, and (2) social scientific methods are absent when determining how to manage injury prevention in the workplace. In response, the current study developed and tested a multilevel intervention case study at two industrial mineral mines to help managers and workers communicate about and reduce respirable silica dust exposures at their mine sites. A dust assessment technology, the Helmet-CAM, was used to identify and encourage communication about potential problem areas and tasks on site that contributed to elevated exposures. The intervention involved pre-and post-assessment field visits, four weeks apart that included multiple forms of data collection from workers and managers. Results revealed that mine management can utilize dust assessment technology as a risk communication tool to prompt and communicate about healthier behaviors with their workforce. Additionally, when workers were debriefed with the Helmet-CAM data through the device software, the dust exposure data can help improve the knowledge and awareness of workers, empowering them to change subtle behaviors that could reduce future elevated exposures to respirable silica dust. This case study demonstrates that incorporating social scientific methods into the application of health and safety management strategies, such as behavioral modification and technology integration, can leverage managers' communication practices with workers, subsequently improving health and safety behaviors.

Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries

The process industry has made major advancements and is a leader in near-miss safety management, with several validated models and databases to track close call reports. However, organizational efforts to develop safe work procedures and rules do not guarantee that employees will behaviorally comply with them. Assuming that at some point, every safety management system will need to be examined and realigned to help prevent incidents on the job, it is important to understand how personality traits can impact workers' risk-based decisions. Such work has been done in the mining industry due to its characteristically high risks and the results can be gleaned to help the process industry realign goals and values with their workforce. In the current study, researchers cross-sectionally surveyed 1,334 miners from 20 mine sites across the United States, varying in size and commodity. The survey sought to understand how mineworkers' risk avoidance could impact their near miss incidents on the job-a common precursor to lost-time incidents. Multiple regressions showed that as a miner's level of risk avoidance increased by 1 unit in the 6-point response scale, the probability of experiencing a near miss significantly decreased by 30% when adjusting for relevant control variables. Additionally, a significant interaction between risk avoidance and locus of control suggested that the effect of risk avoidance on near misses is enhanced as a miner's locus of control increases. A one-unit increase in locus of control appends the base effect of risk avoidance on near misses with an additional 8% decrease in the probability. Findings are discussed from a near-miss safety management system perspective in terms of methods to foster both risk avoidance and locus of control in an effort to reduce the probability of near misses and lost time at the organizational level within the process industry and other high-hazard industries.

RELATED PAPERS

Robson Carneiro Rocha

Jelena Vekovic Delic

elias jazayeri

International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management

Pedro Domingues

Nicholas Petrovski

Gerard I.j.m. Zwetsloot

Journal of Operations Management

Mark Pagell

International Journal of Mining Science and Technology

Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies

Malcolm Ballantyne

Raphael Onuoha

Alexandros Sfakianakis , Elisaveta Stikova

Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health

Proceed Sibanda

Abdul Mohammed

Kazem Oraee , Arash Goodarzi

Syed Minhal

Nurul Fadly Habidin

Harun Karakavuz

ahmed mukhtar

Parvin Nassiri

Juliano Endrigo Sordan

Dr Ciarán McAleenan , Philip McAleenan

kassu sileyew

Industrial Health

Emilio Passetti

Kassu Sileyew

Report of Investigations, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Marcia Nathai-Balkissoon

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Mohd Arif Marhani

Justus Harding

Celeste Jacinto

Abdul Aziz Sudin, PhD

Valeria Andrade

Eric Danso-Boateng , Osei-Wusu Achaw

Adhia Prenata

Margherita Pasini

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Safety Management Systems (2003)

Chapter: chapter two - literature review.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

5 CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW NATIONAL STUDIES Four national studies are addressed in this section. They are Safety Management System: A National Status (3), Safety Management System Update Survey (4), Transporta- tion Infrastructure: Statesâ Implementation of Transportation Management Systems (5), and a survey conducted as part of NCHRP Project 17-18(05), Integrated Management Process to Reduce Highway Injuries and Fatalities Statewide (6). A Look at the National Status The Safety Management System: A National Status (3) was conducted in cooperation with TRB Committee A3B01, Transportation Safety Management. The purpose of the survey was to gain a national perspective on progress to- ward the development and implementation of each stateâs SMS. Fifty-one surveys, including one from the District of Columbia, were returned between June and August 1995. The following conclusions were drawn from the survey: ⢠All states plus the District of Columbia had identified a focal point for the SMS, with 85% found in a DOT or equivalent department. ⢠Most states were using an administrative structure com- posed of a coordinating or executive committee and subcommittees representing a broad-based group of in- dividuals from a variety of agencies and organizations. ⢠More than 80% of the states had developed a mission statement, goals, or major objectives to guide the SMS implementation process. ⢠Sustained commitment to the SMS was seen as struggling in some states, whereas others were using memorandums of agreement or understanding to help sustain support from the various safety partners. ⢠States were using a variety of methods to share informa- tion about the SMS initiative, including computer-based electronic mail, the Internet, workshops, safety program resource books, brochures, and newsletters. ⢠To help deal with the staffing shortage created by the extra work involved in the SMS, 32 states elected to hire consultants. These consultants were asked pri- marily to help with the development of the work plan, resource book, surveys, and workshops. ⢠The primary funding source for the SMS develop- ment was a combination of federal and state money. ⢠Positive outcomes from the SMS process were re- ported by 49 (96%) of the state officials who devel- oped and implemented their systems. ⢠Major barriers to the development and implementa- tion of the SMS were funding, adequate staff, juris- dictional battles, data issues (availability, accuracy, timeliness, jurisdiction, and technical problems be- tween agencies that control data collection and analy- sis), and sustained commitment to the initiative. Appendix A features a summary of the state reports on SMS program elements. A Look at Implementation In 1997, the U.S. General Accounting Office released a Report to Congressional Committees entitled the Transpor- tation Infrastructure: Statesâ Implementation of Transpor- tation Management Systems (5). The report identified ⢠The status of the statesâ development and imple- mentation of the six systems for managing highway pavement, bridges, highway safety, traffic conges- tion, public transportation facilities and equipment, and intermodal transportation facilities and sys- tems; ⢠How the states expect to use the systems; and ⢠The factors that have facilitated or hindered the de- velopment and implementation of the systems. General information about the development and imple- mentation of the systems was collected in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. More detailed in- formation was collected from seven states (Maryland, Michigan, Montana, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, and Texas) selected for case studies because of their ex- periences in developing, implementing, and using the sys- tems. Additional but less comprehensive information was collected from Colorado, Florida, and Missouri. General findings are as follows: ⢠As of September 1996, approximately one-half of the states were moving forward with all six transporta- tion management systems, even though they were no longer mandatory. The remaining states were devel- oping or implementing at least three of the systems. ⢠All states were implementing the pavement manage- ment system, and nearly all states were implementing the bridge, safety, and congestion management systems. ⢠Nationwide, more than half of the states plan to inte- grate the management systems. States recognize that

6 to obtain the optimum use from the systems, they need to be integrated. ⢠Mandating of the systems had several outcomes, in- cluding providing a catalyst to develop and imple- ment the new systems and to obtain high-level sup- port and top-priority status. ⢠Removal of the mandate has had various results. Several states are continuing their efforts because they view the systems as beneficial to the decision- making process, whereas others have lessened sup- port for further developing certain systems. ⢠Some states reported that the failure to issue a clear and timely rule on management systems following the 1991 mandate had caused difficulties in imple- menting the public transportation, congestion, and in- termodal management systems. The following points summarize the General Account- ing Office report conclusions specific to the status of SMS development and implementation: ⢠As of September 1996, 48 states, the District of Co- lumbia, and Puerto Rico were developing SMSs. ⢠South Carolina and Ohio reported that they were not currently implementing their systems. ⢠At least 30 states included all public roads or all state-maintained roads in their systems. Two states were including only National Highway System roads. ⢠The composition of an SMS takes many formsâ from an administrative structure composed of a coor- dinating or executive committee and subcommittees representing many agencies to a large database that merges safety information from a number of sources. A Look at Updates In 2000, a second national study, Safety Management Sys- tem Update Survey (4), was undertaken in conjunction with the TRB A3B01 Transportation Safety Management Com- mittee. The purpose of this study was to collect informa- tion to update the status of each stateâs highway SMS. Be- cause Section 205 of the National Highway System Designation Act of 1995 made SMSs optional, implemen- tation status was of interest. Survey data were collected in late 2000, with follow-up contacts made in November 2001 to confirm the status of responses. Forty-nine states and the District of Columbia submitted surveys. The study was not published, but the results are worthy of review. The following points summa- rize these results: ⢠Twenty-six states indicated having both an interdisci- plinary committee and an SMS. States indicating that they had only an SMS or an interdisciplinary com- mittee numbered six and eight, respectively. Ten states reported having no SMS or interdisciplinary committee. ⢠SMSs were found to be active at both the state and local levels in 15 states. ⢠Of the 34 states having coordinating committees, 25 were established as a result of the ISTEA mandate, and 30 meet at least three times each year. ⢠Seventy-four percent of the coordinating committees had mission statements, 70% had major goals, and 68% had strategies or objectives. Eighteen states used a subcommittee structure. ⢠Law enforcement, engineers, state highway safety of- fice representatives, health professionals, and state agencies were represented on 75% of the coordinat- ing committees. Community volunteers and construc- tion industry representatives were least likely to par- ticipate on these committees. ⢠Major activities undertaken by the coordinating committees included development of a strategic plan, review of state safety data, formulation of safety leg- islation, and planning of state safety conferences. ⢠Improved communication and coordination between safety agencies and organizations, as well as joint legislative efforts, were the most frequent positive outcomes noted by the respondents. ⢠Resources, jurisdictional issues, coordination, politi- cal factors, time, and leadership barriers have im- peded the effectiveness of the statesâ SMS and coor- dinating committees. ⢠Key elements identified as maintaining the momen- tum of a coordinating committee and/or SMS were commitment and buy-in from key agency leadership, regular meetings, development of a strategic action plan, a mission statement, and activities that commit- tees would cite as victories. ⢠Of those states not having an SMS or coordinating committee, 80% reported that the regulationâs change from required to optional was the major reason that these efforts were abandoned. Appendix B features a summary of selected responses from this survey. A Look at Integrated Management A third national study, NCHRP Project 17-18(05), Inte- grated Management Process to Reduce Highway Injuries and Fatalities Statewide, was undertaken by iTRANS in 2001 (6). The study questionnaire collected information in the categories that make up an integrated management sys- tem, including the mission statement, safety management, safety champions, funding, safety initiatives, resource allo- cation decision making, legislation, analysis, and data- bases. With 40 responses, a picture was developed that

7 shows the importance of these elements in the various state management processes. The existence of a safety champion (an individual and not a group) was recognized as âvery important.â Follow- ing the implementation of the process, states cited improve- ments observed, which included attaining greater cooperation between agencies; serving as a focal point for safety advo- cates; enhancing communication among enforcement, en- gineering, education, and emergency services; stimulating safety concerns across multiple agencies; and serving as a catalyst for devising new safety initiatives. When asked about the importance of factors that trigger new safety initiatives, states identified federal and state funding and legislation as the main factors. A high-profile event, collision, or crash (e.g., high fatality school bus crash), a program being promoted by a high-profile indi- vidual, and successful implementation of the initiative in other states, were also considered of importance. Quantitative analysis received the highest rating in de- ciding which safety countermeasures to apply. Internal ex- pert opinion was rated more important than the opinion of external experts. Internal safety management processes fell slightly below âimportantâ in the rating. The iTRANS questionnaire asked the additional ques- tion, âOnce issues have been identified, could you describe briefly the decision making process as to how funding is allocated to engineering, enforcement, education, or emer- gency medical services with regard to safety initiatives?â Iowa and Louisiana had an SMS component in their re- sponses, whereas Maine, Indiana, Michigan, Nebraska, New York, and Washington mentioned a coalition, partner- ship, team, or collaboration among various groups in their decision-making process. The responses are presented in Appendix C. On average, the benefit of a software package that ac- cepts standardized input for safety analysis was not per- ceived to be much different than documentation of analyti- cal methods for safety analysis, in regard to the question about the benefit of various resources to safety analysis. Overall, the respondents rated the completeness of their da- tabases as âgood.â The main components of the Integrated Safety Man- agement System (ISMSystem) developed in conjunction with NCHRP 17-18(05) are leadership, mission and vision, organizational structure, integrated safety management process, resources, and tools and related documentation. Figure 1 depicts the relationship between the different components and conveys the order of development in- volved in building an ISMSystem. The ISMSystem works within and depends on an external environment that in- Exter Mission & Vision Integrated Safety Management Process Leadership Tools Organizational Structure nal Environment Legislation & Funding Resources FIGURE 1 Components of the Integrated Safety Management System (ISMSystem). [Source: iTRANS, NCHRP Report 501: Integrating Management Process to Reduce Highway Injuries and Fatalities Statewide (6).] cludes legislation and funding. Fundamental to the ISMSystem is an interdisciplinary organizational structure, formed through a coalition of highway safety agencies, that allocates different responsibilities to specific groups of people who must work together to maximize safety. Other personnel resources include an operations man- ager (for day-to-day management), task teams that develop strategies and action plans for implementation, and the risk analysis and evaluation group to undertake analyses of highway data to support the decision-making process. The tools necessary to implement the system include the methodologies for identifying crash concerns and evaluating strategies, impact and process performance evaluation meth- ods, optimization approaches, best practice suggestions for maintaining databases, and recommendations for improv- ing interagency coordination and communication (6). NATIONAL REPORTS Several national reports addressing SMSs are available. They include workshop proceedings, good practice re- views, and study tour summaries. This section summarizes several of these key reports. Management Approach to Highway Safety: A Compilation of Good Practices The FHWA developed the initial guidance document in January 1991, with a subsequent revision in April 1991,

8 and a final document completed in December 1991 (7). The purpose was to provide general guidance for develop- ing and implementing a management approach to high- way safety. It outlined eight key elements in the man- agement approach to highway safety to ensure that processes and programs are effectively coordinated and carried out. ⢠GoalsâLong- and short-term highway safety goals establish a means for resource allocation. ⢠AccountabilityâThis is an essential management tool for tracking implementation of highway plans and comparing progress with established goals. ⢠TrainingâPersonnel with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to carry out identified responsibilities are es- sential. ⢠Monitoring and evaluationâThe design, operation, maintenance, and process reviews determine whether or not the safety processes and improvements are having the desired effects. ⢠Integrated databaseâAn analysis of timely and accu- rate data is necessary to identify safety problems and to select and implement effective accident counter- measures. ⢠Safety analysisâThese analyses include accident and operational investigations. ⢠CoordinationâIntraagency and interagency coordi- nation will enhance the implementation and man- agement of a comprehensive highway plan. ⢠Technology and information exchangeâProactive research and technology and information exchange provide many opportunities for addressing changes and improving safety. Safety Management System Workshop Proceedings: Managing Mobility Safely From September 17 to 19, 1991, a Safety Management System Workshop was held in Williamsburg, Virginia. The purpose of the workshop was to enable participants to pro- vide guidance for the development and implementation re- quirements of an SMS. The workshop also focused on the experiences of Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington in working with the draft Management Approach to Highway Safety in the development of their respective SMSs. The resulting report, Safety Management System Workshop Proceedings: Managing Mobility Safely (8), outlined sev- eral key points resulting from this effort. ⢠The Management Approach to Highway Safetyâ Good Practices Guide (with minor changes) is a good foundation on which to build an SMS. ⢠Safety management is a workable and useful concept, but it should be implemented not as a new stand- alone system, but as one that integrates safety deci- sions into a stateâs overall highway management process. ⢠SMS requirements must be flexible enough to con- form to various organizational structures of the states; they must also be prescriptive and specific enough to ensure safety objectives are achieved. ⢠Coordination must be strongly advocated and prac- ticed within the highway agency and with other agencies and groups having the common goal to im- prove highway safety. Highway agencies need to en- sure this coordination is carried out. Safety Management System: Implementation Workshop Proceedings The FHWA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Ad- ministration hosted a national Safety Management System Workshop on January 20 and 21, 1994. The workshop ad- dressed the issue of what can be done within the limits of the law and the regulations to effectively implement an SMS. Those persons designated as the stateâs SMS focal points were invited to attend the workshop. Representa- tives from select metropolitan planning organizations, counties, cities, other federal agencies, highway-user advo- cacy groups, police, emergency medical groups, and motor vehicle administrators also participated. A total of 258 in- dividuals attended the workshop. The goal of the workshop was to have all jurisdictions start in the same direction. Therefore, it addressed what can be done within the limits of the law and the regulations to effectively implement an SMS. There seemed to be a general consensus on the follow- ing items (9): ⢠The SMS was a process for managing highway safety activities, not a plan itself. ⢠The SMS process would not be easy, but it would be worthwhile. ⢠Limited resources are a big problem. ⢠Each SMS would be state-specific, responding to the resources available and the needs in each state. ⢠Proposed guidelines should remain just that and not become mandates. ⢠A uniform system of data records and electronic for- matting was seen as necessary and was proposed. ⢠Data within a state and between states should be han- dled uniformly. ⢠The SMS is a safety effort and not a data collectionâ only a program. A copy of the draft of Safety Management Systems: Good Practices for Development and Implementation (10) was distributed and reviewed.

9 FHWA Study Tour for Highway Safety Management Practices in Japan, Australia, and New Zealand A U.S. study team examined safety management practices in Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. The visit, conducted from June 10 to June 26, 1994, had as its purpose â . . . to assess Safety Management Systems (SMS) in the three countries, their programs or components and technolo- gies of SMS activities including people, vehicles, and roads; compile the information; and identify effective strategies for implementation in the United States of Americaâ (2). Japan was investing in information technology to achieve quantum gains in highway safety, whereas Austra- lia and New Zealand used a networking method to include relevant safety stakeholders in the process of decision making to develop and implement highway safety pro- grams, as well as a safety audit process. The report concluded that the major transferable safety management finding of the tour was the management phi- losophy observed in all three countries, namely that of networking and building consensus among stakeholders in the search for solutions to traffic safety problems (2). Safety Management Systems: Good Practices for Development and Implementation This document evolved from a draft document entitled Safety Management Systems: Good Practices for Devel- opment and Implementation (10) produced by the FHWA in November 1993. A subsequent revision was done in Au- gust of 1994, with this expanded document released in May 1996. The purpose of the document was to provide general guidance to managers and safety specialists on the formu- lation of an SMS. The guidance is flexible, recognizing that the development and implementation of an SMS is an evolving process. The document emphasized that because each state is unique, there is no one correct way to develop and imple- ment an SMS. However, the following five major areas should be considered: 1. Coordinating and integrating broad-based high- way safety programs; 2. Developing processes and procedures to ensure that the major safety problems are identified and addressed; 3. Ensuring early consideration of safety in all highway transportation programs and projects; 4. Identifying safety needs of special user groups; and 5. Routinely maintaining and upgrading safety hardware, highway elements, and operational fea- tures. It was further suggested that within each of these five major areas, eight elements should be incorporated, as ap- propriate. 1. Establishment of short- and long-term highway safety goals to address both existing and antici- pated safety problems. 2. Establishment of accountability by identifying and defining the safety responsibilities of units and positions. 3. Recognition of institutional and organizational initiatives through identification of disciplines in- volved in highway safety at the state and local levels; assessment of multiagency responsibilities and accountability; and establishment of coordi- nation, cooperation, and communication mecha- nisms. 4. Collection, maintenance, and dissemination of data necessary for identifying problems and de- termining improvement needs. 5. Analysis of available data, multidisciplinary and operational investigations, and evaluations of ex- isting conditions and current standards to assess highway safety needs, select countermeasures, and set priorities. 6. Evaluation of the effectiveness of activities that relate to highway safety performance, to guide fu- ture decisions. 7. Development and implementation of public in- formation and education activities to educate and inform the public about safety needs, programs, and countermeasures that affect safety on the na- tionâs highways. 8. Identification of skills, resources, and current and future training needs to implement the stateâs ac- tivities and programs affecting highway safety; development of a program to carry out necessary training; and development of methods for moni- toring and disseminating new technology and in- corporating effective results (10). Continuous improvement in reducing the number and severity of crashes, as well as the medical and financial consequences is the primary goal of the SMS. The agencies should have an internal quality control system, or a self- assessment process, that ensures continuous improvement and compliance with the goals of the SMS. The self- assessment should not only measure the level of effort, but what is actually being accomplished as a result of that ef- fort (10).

10 ⢠Builds on two basic partsâa collaborative process represented by a standing local agency SMS committee and an eight-element decision-making process. STATE AND LOCAL GUIDES Two publications are discussed in this section: Local Agency Safety Management System (11), developed for lo- cal agencies by the Washington State DOT and Toolbox of Highway Safety Strategies (12), sponsored by the Iowa High- way Safety Management System Coordinating Committee. The eight elements of a local agency SMS are outlined in Table 1. TABLE 1 SUMMARY OF EIGHT ELEMENTS OF SAFETY Local Agency Safety Management System M ANAGEMENT SYSTEMS Element Description Local policy Establishes policy and responsibilities. Data collection Provides information to support decisions and monitors their results. Data analysis Converts field data into usable information to assist decision makers. System output Presents the analyzed and processed data in a format that is usable to decision makers. Project prioritizing and program development Includes final prioritizing of transportation safety needs, selecting cost-effective solutions, and adopting safety policies, standards, procedures, and programs. Program implementation Carries out funded projects resulting in safety enhancements and educational, enforcement, and emergency services programs. Performance monitoring Measures and analyzes results of transportation decisions, countermeasures, and programs for future work program development. Annual safety reporting Annual report of safety system work efforts, expenditures, and system performance. The purpose of this document is to provide Washingtonâs local agencies with a resource for implementing the Wash- ington State SMS (11). The document is divided into three sections: OverviewâYour Safety Management System; The SMS Process: How an SMS Works; and Tools to Get Your SMS Started. The primary goal of the local agency SMS is to prevent and reduce the number and severity of roadway collisions, transportation-related injuries, and property damage (11) (Figure 2). The local agency SMS does the following: ⢠Provides a process for obtaining objective informa- tion that helps agencies identify and prioritize safety needs and choose cost-effective strategies to improve the safety of their transportation systems; ⢠Involves the roadway, human, and vehicle elements; ⢠Identifies methods for addressing safety issues in the engineering, education, enforcement, and emergency service areas; and Toolbox of Highway Safety Strategies The Iowa initiative is not a âhow-toâ manual for develop- ing an SMS, but a highway safety resource product of the Iowa SMS Coordinating Committee members and friends. Adopting most of the content areas modeled in the AASHTO Strategic Highway Safety Plan, the Toolbox of Highway Safety Strategies was developed as Iowaâs own compilation of problem definitions, data, and potential so- lutions. The purpose of the toolbox is to assist and inspire Iowaâs highway safety professionals, policymakers, and citizens in implementing ways to improve highway safety, thereby reducing death, injury, and economic loss on Iowaâs roadway system (12) (Figure 3). The toolbox contains the following materials: ⢠Toolbox notebook contentsâThe Iowa SMS Toolbox of Highway Safety Strategies (300+ pages in a 3- hole-punched format); FIGURE 2 Local Agency Safety Management System (11). (Source: Washington State DOT, 1998.)

11 ⢠Law, policy, and enforcement changes; ⢠Education and public awareness to influence driver behavior; ⢠Roadway design changes systemwide or in high- crash-incident locations/segments; ⢠Technology applied to assist drivers or enhance roadways; ⢠Availability and delivery of emergency and medical services; ⢠Data collection and analysis; and ⢠Planning and management. The document is organized into three parts: ⢠Potential strategies for highway safety improvement, organized into chapters on drivers, other users, high- ways, emergency response, and planning and man- agement; ⢠Resources, including primary contributors and key organizations; and ⢠Appendixes providing graphs and trends of Iowa crash data and summary findings of the Iowa SMS Public Opinion Survey. FIGURE 3 Toolbox of Highway Safety Strategies (12). (Source: Iowa Highway Safety Management System, Iowa DOT 2002.) In addition to the printed and CD-ROM versions, the Iowa SMS Toolbox of Highway Safety Strategies and âHighway Safety Strategies for IowaâExecutive Sum- mary of the Iowa SMS Toolboxâ are located on the SMS website at www.IowaSMS.org. ⢠Summary bookletââHighway Safety Strategies for IowaâExecutive Summary of the Iowa SMS Tool- boxâ (20 pages); ⢠EndorsementâStatement of Iowaâs Commitment to Highway Safety; ⢠CD-ROMâElectronic versions of the Iowa SMS Toolbox of Highway Safety Strategies and âHighway Safety Strategies for IowaâExecutive Summary of the Iowa SMS Toolboxâ; and SUMMARY OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW As was discussed, the principles of an SMS process have their foundation in both guides and guidelines focusing on the enhancement and management of highway safety, as well as federal legislation. National studies revealed that the SMS process has brought about many positive out- comes, particularly the enhancement of coordination, co- operation, and communication among key highway safety stakeholders. Successful SMS state initiatives continue to thrive in the absence of a legislative mandate. ⢠SMS âtoolâ with interchangeable screwdriver heads. The Iowa SMS toolbox reinforces the safety goals, poli- cies, and actions of highway safety agencies and practitio- ners by identifying many alternative actions that could be considered for implementation over the next 10 to 20 years. It also identifies some specific implementation steps that could be completed sooner (12). The document offers a range of potential solutions, including the following:

TRB’s National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Synthesis Report 322: Safety Management Systems (SMS) provides an overview of current transportation agency practices, recent literature findings, and reviews of two model state SMS initiatives. According to the report, benefits derived from the SMS process are increased coordination, cooperation, and communication among state agencies and improvements to data analysis and collection procedures, as well as collaborative strategic plans.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Systematic Literature Review on Indicators Use in Safety Management Practices among Utility Industries

Affiliations.

- 1 Centre for Research in Development, Social and Environment (SEEDS), Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Bangi 43650, Malaysia.

- 2 Department of Occupational Safety and Health Malaysia, Ministry of Human Resources, Government Administrative Centre, Putrajaya 62530, Malaysia.

- 3 Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Tadulako, Palu 94118, Indonesia.

- 4 Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Tadulako, Palu 94118, Indonesia.

- PMID: 35627731

- PMCID: PMC9140665

- DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19106198

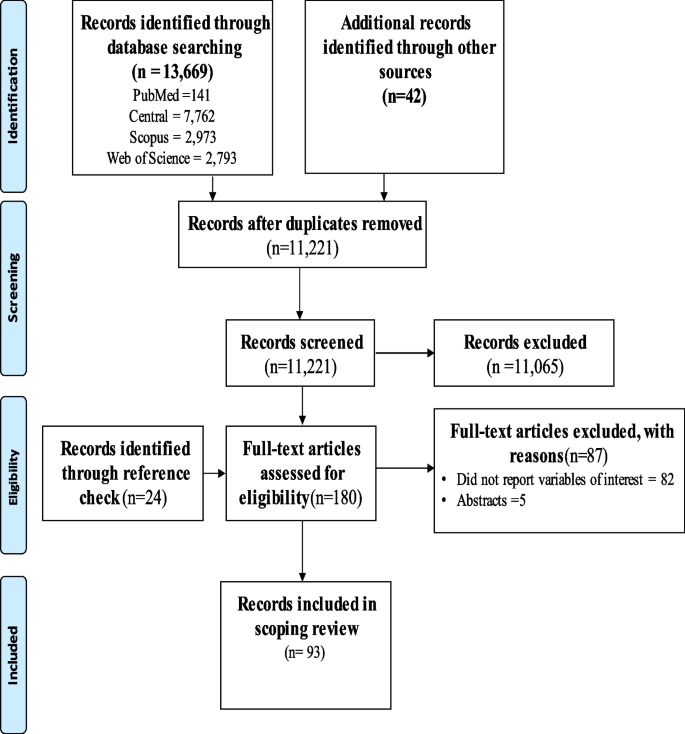

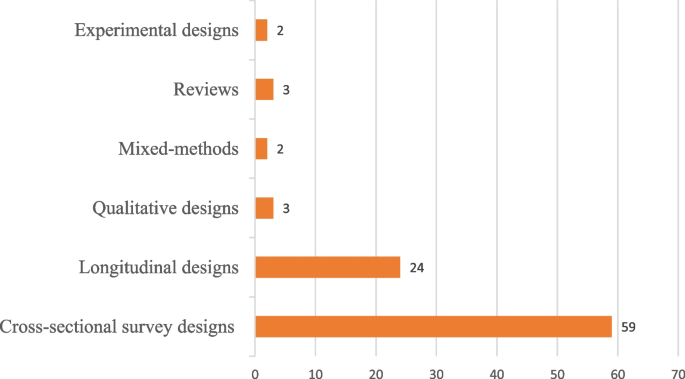

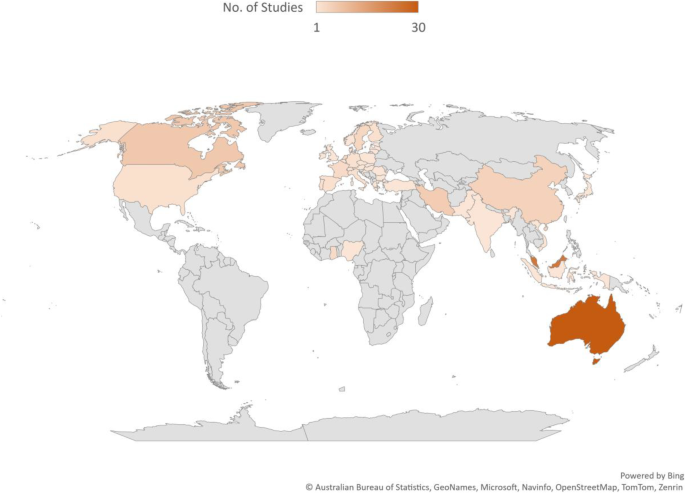

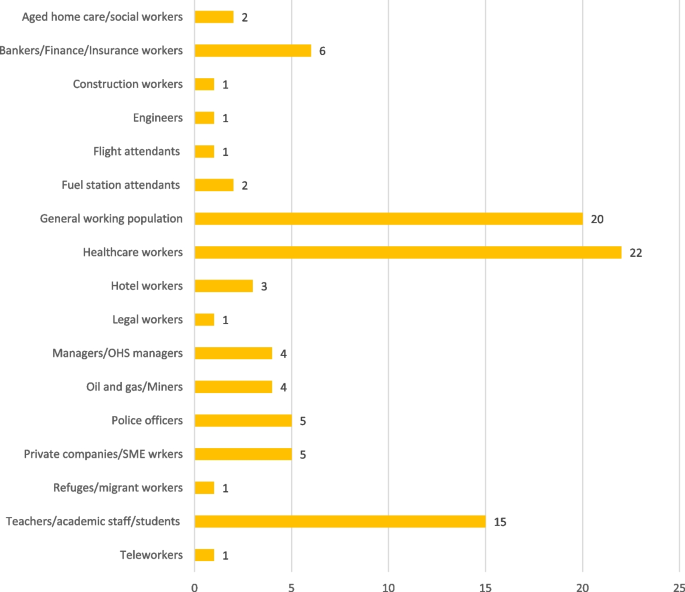

Background: Workers in utility industries are exposed to occupational accidents due to inadequate safety management systems. Accordingly, it is necessary to characterize and compare the available literature on indicators used in safety management practices in the utility industries.

Methods: The systematic literature review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis statement. This study considered 25 related studies from Web of Science and Scopus databases.

Results: Further review of these articles resulted in three mains performance indicators; namely, driven leading indicators, observant leading indicators, and lagging indicators consisting of 15 sub-indicators.

Conclusions: Future studies should consider researching a more comprehensive range of utility industries, measuring subjective and objective indicators, integrating risk management into safety management practices, and validating the influence of leading indicators on safety outcomes. Further, researchers recommend including accidents, fatalities, lost time injuries, and near misses in safety outcomes.

Keywords: lagging indicators; leading indicators; occupational safety and health; safety management practices; safety performance.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Accidents, Occupational / prevention & control

- Organizations

- Risk Management

- Safety Management*

Grants and funding

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Safety Management and Safety Performance Nexus: Role of Safety Consciousness, Safety Climate, and Responsible Leadership

Farida saleem.

1 Department of Management, College of Business Administration, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh 11586, Saudi Arabia

Muhammad Imran Malik

2 Department of Management Sciences, COMSATS University Islamabad, Attock Campus, Attock 43600, Pakistan

Associated Data

The data will be available on request from the corresponding author.

Drawing from social system theory, social identity theory, and social exchange theory, this study examines how safety management practices are linked with employee safety performance through safety consciousness and safety climate. Furthermore, responsible leadership is introduced as a boundary condition in the safety consciousness—safety performance and safety climate—safety performance relationships. Data were collected from employees belonging to pharmaceutical firms located in different industrial zones of Lahore, Pakistan. The support is found for full mediation of safety consciousness and safety climate for the safety management and safety performance relationships. Responsible leadership moderates the safety consciousness—safety performance and safety climate—safety performance relationships so that when the safety climate is weak or the safety consciousness is low, a high level of responsible leadership enhances safety performance.

1. Introduction

Occupational safety and safety performance can provide competitive advantage to the firms [ 1 ] and have has become a prominent area of research in the last three decades [ 2 , 3 ]. The focus of this research is to identify safety-related outcomes and to provide guidance for improving health and safety in organizations. An inadequate safety management system is the root cause of the majority of industrial disasters [ 4 ]. Hence, organizations’ adoption of safety management systems is linked with their attempt to achieve performance excellence. Safety performance is one of the key factors for gaining a competitive advantage in today’s rapidly globalizing world. Effective preventive measures like safety management systems or behavior-based system approaches can help in the reduction in occupational accidents.

According to the most recent data on workplace health and safety, there are currently 2 million people who believe their illnesses were made worse by their employment, and each employee loses an average of 30 million days (1.3 days) every year because of illness or injury [ 5 , 6 ]. This is a result of potential carelessness on the part of the companies in maintaining safety procedures. Some businesses fail to give health and safety the priority it needs, despite the clear necessity for proactive management. This could be the result of insufficient staff resources or a lack of expertise, skills, and motivation. However, employee safety management and alertness are the keys to reducing the ratio of work-related illnesses and accidents at work. Safety management relates to the real procedures, duties, and responsibilities involved in staying safe [ 7 , 8 ]. Safety consciousness, on the other hand, is the awareness of risks and the vigilance for danger. It has a strong influence on the actions of an individual because of his desire to remain alive and uninjured. There is always a need to develop safety consciousness because most injuries can be traced to someone’s lack of safety consciousness [ 3 , 9 ]. It is a key predictor of safety outcomes that has attracted limited attention.

According to Kirwan [ 8 ], safety management is related to all practices that are associated with remaining safe, which includes actual practices, roles, and functions. Safety management is a sub-system of organizational management systems that are integrated into the organization and has a focus on controlling the hazards that can negatively affect the health and safety of employees [ 4 ]. Safety management systems not only implement policies and procedures, activities that are required to control the hazards, but also comply with the existing legislation applicable to the organization. The safety management system is an important antecedent of a safety climate [ 3 , 4 ] and the development of safety consciousness in employees. A safety climate is the shared perception of employees regarding the state of safety of their organization [ 10 ]. Similarly, safety consciousness is the awareness of an individual regarding the safety issues and concerns of an organization [ 11 ]; this awareness can be at both cognitive and behavioral levels [ 4 ]. Neal et al. [ 12 ], and Vinodkumar and Bhasi [ 4 ], have considered safety climate as a factor that influences the safety performance (including safety compliance and safety participation) of an organization. de Koster et al. [ 13 ] identified safety consciousness as an antecedent of the safety performance of employees in an organization. Based on social system theory (SST), social identity theory (SIT), and social exchange theory (SET), safety consciousness and safety climate are both proposed as mediators for the safety management and safety performance relationship.

A responsible leadership role in safety management and performance relationship is implicit as the majority of organizations’ central goal is to ensure the value of safety is in the minds of employees [ 14 ]. The personality, values, and choices that employees make, the people they trust, the appeals they respond to, and the way they invest their time and energy in an organization are the outcomes of the values of leadership [ 14 , 15 ]. Based on social identity theory (SIT) and social exchange theory (SET), responsible leadership is proposed as moderator for the safety consciousness and safety performance and safety climate and safety performance relationships.

The importance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), especially in developing countries, cannot be denied. SMEs are considered a major contributing sector to the economic development of emerging and developing economies. Similar to other developing and emerging economies, most businesses in Pakistan are SMEs [ 16 , 17 ]. According to one report, about 99% of economic establishments are SMEs and their GDP contribution is 40% with 26% exports from the manufacturing sector [ 18 ]. The majority of firms in the pharmaceutical industry of Pakistan are SMEs [ 19 ]. Even though safety management and its outcomes have been researched and reported from various parts of the world, there is not much evidence available from small and medium-sized pharmaceutical firms in Pakistan, where safety performance is yet to get the priority it deserves.

The aim of the current investigation is to identify the impact of safety management practices on safety performance while taking safety consciousness and safety climate as mediators and responsible leadership as the moderator in pharmaceutical firms in Pakistan. This investigation is attempting to contribute to the literature in three ways: first, by empirically investigating a comprehensive mediated moderation model of safety management and safety performance; second, by generalizing the safety management and safety performance investigations that are majorly focused on developed countries to a developing country; and last, by focusing on the pharmaceutical industry of Pakistan.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical foundations for this study come from three theories, namely social systems theory, social identity theory, and social exchange theory. The social system theory [ 20 ] holds social behavior as the result of the interaction of the institution’s role and expectations and individual personality and needs [ 21 , 22 ]. In an organization, organizational behaviors are products of interaction between the organizational factors and individual factors. The safety management practices adopted by the organizations in terms of safety-policy making, safety training, safety communication, and preventive planning lead to developing a safety climate that further boosts safety performance. Skyttner [ 23 ] stated that the emergence of anything results from the interaction of independent parts when they stop being independent and start to influence each other; therefore, it is posited that when individuals come together (the leader and employees) and develop a common sense of implementing safety in the organization it creates a safety climate in the organization, thus satisfying the social systems approach. It is noted that when individuals adopt safety practices, they try to achieve safety synergy [ 24 ], reflecting the social systems approach. Individual after individual following the safety standards combine together and make it a success.

Similarly, according to social identity theory, positive CSR perceptions (safety management, safety consciousness, safety climate, and safety performance) enhance organizational identification. This leads to the desire to maintain this positive identity and group membership, which later on translates into commitment. In safety-oriented organizations, the people feel safe and tend to retain their jobs for longer times.

The theory of social exchange [ 25 ] postulates that in any social interaction where one party acts in a manner that benefits a second party, a mutual expectation will emerge that obligates the second party to reciprocate, at some later stage, by acting in a way that benefits the first party [ 26 ]. The social exchange theory (SET) is a theory that describes relationships as result-oriented social behavior. It is based on the reciprocity of the behaviors. The social behavior in the interaction of organization and employees is used for a cost–benefit analysis to create a win–win situation [ 27 ]. In this situation of give and take, this study argues that responsible leaders, by virtue of taking care of the stakeholders [ 28 ], will ensure the formulation of effective health and safety policies and procedures, provide the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities, provide support on such policies and procedures, communicate performance standards, and promote a safety climate. As suggested by the social exchange theory [ 25 ], responsible leaders will be fostering a trusting relationship among employees (as stakeholders) through their proactive participation in ensuring the implementation of health and safety procedures, thereby acting as role models of health and safety rules and regulations [ 29 ]. Moreover, it is noted that socially responsible behaviors such as safety behaviors cannot be implemented without the influence of the leaders [ 30 ]. Under such arguments, it is posited that when employees get something of value from their leaders, they try to give it back through their hard work and by following the practices they require from them to ensure performance targets. The employees who take training from their responsible leaders tend to stand with them and try their best to practice safety at the workplace, thus enforcing the social exchange. The proposed research framework is presented in Figure 1 .

Proposed Research Framework.

2. Literature Review

2.1. safety management and safety consciousness.

According to Barling et al. [ 11 ], safety consciousness consists of two components: the cognitive component and the behavioral component. This indicates that the idea goes beyond only being aware of safety risks and that taking necessary action is important too [ 31 , 32 ]. Furthermore, in the organizations, the modeling of behaviors depends upon demands put forth by the top managers. The managers emphasize the importance of health and safety policies and procedures and will inspire subordinates to ponder safety, hence increasing their safety consciousness [ 33 ]. Similarly, safety management requires clear communication of the health and safety policies. This requires the provision of training to the employees to enhance their subordinates’ consciousness. Studies suggest that consciousness is an important predictor of safety behaviors.

The main goal of safety management is to prevent workplace injuries, illnesses, and deaths, as well as the suffering and financial hardships of the organizations [ 34 ]. The recommended practices use a proactive approach to managing workplace safety and health, instead of using the reactive ones, i.e., problems are addressed only after a worker is injured or becomes sick. These recommended practices recognize that finding and fixing hazards before they cause injury or illness is a far more effective approach [ 35 ].

The rate of accidents can be minimized through safety management and consciousness. This relationship forms a pattern that affects the well-being of all workers. The factor of luck may distort the pattern, but over a long period of time the pattern remains unchanged [ 36 ]. The employees are required to perform in a safer way that would not harm themselves and their co-workers [ 37 ]. Common causes of error may include time pressure, mental pressure, fatigue, being new to the task, distractions, and overconfidence.

The safety management practices enforced through safety policies, plans, procedures, training, and frequent safety communication enable people to avoid accidents [ 13 , 38 ]. The push to follow the safety practices from the managers adds to the consciousness. This consciousness as mindfulness brings positive results for individuals and organizations. Safety-conscious workers are more likely to notice potential risks, make unbiased judgments, and control their unsafe or risky behaviors [ 39 , 40 ]. Bahari [ 41 ] conducted a safety-related study and found that the employees’ safety can be improved by employees’ understanding of safety, knowledge about safety, and the skills necessary to ensure safety. Moreover, the management’s attitude and actions toward safety were found to be crucial in improving organizational safety.

Accidents at work generally occur because of deficient knowledge or training, deficient supervision, and deficient procedures to carry out task safety [ 42 ]. The organizations can prevent the dangers via a safety policy implementation across the organization by setting safety objectives. This enables employees to achieve the set safety objectives, which directly means facing low risks and damage [ 43 ]. At the same time, preventive planning is a key to ensuring safety in organizations [ 44 ].

An effective way to promote safety management is safety communication. Pandit et al. [ 45 ] found safety communication to be an effective way of promoting safety management in the organization and poor safety communication can lead to disasters. It is also noted that when not only the managers but also the employees do not communicate frequently about the hazards involved in their work and possible preventive measures to be taken, this leads them to unexpected injuries. Safety training is equally important and enables employees to learn the relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities to tackle possible dangers [ 9 ]. The social systems theory posits that when components of a system combine and work in the same direction, they achieve a synergetic safety working (see Figure 1 ). Therefore, the hypothesis developed is:

There is a positive impact of safety management on safety consciousness .

2.2. Safety Management and Safety Climate

Management concern for safety develops the safety climate. The safety climate is the perceptions and attitudes of the organization’s workforce about surface features of the culture of safety in the organization at a given point in time [ 46 ]. Safety management is the adoption of practices to reduce errors, which fosters a safe climate in the organization. A better safety climate in an organization is associated with committing fewer errors and better outcomes.

Anticipated benefits would stem from the ability of organizations (use of safety practices) with strong safety climates to cultivate behaviors that enhance collective learning by addressing unproductive beliefs and attitudes about errors, their cause and cure [ 47 ].

According to Mearns et al. [ 48 ], the organizations that want safe operations have to ensure a safe climate. Research has focused on supervisors as role models for instilling safety awareness and supporting safe behavior [ 48 ]. Involvement of the workforce in safety-decision-making has also received attention [ 49 ]. These things require a consideration of the safety philosophy of upper management and the safety management system of the organization. Organizations with lower accident rates were characterized by the presence of upper managers who were personally involved in safety activities, the prioritization of safety in meetings and in decisions concerning work practices, and the thorough investigation of incidents [ 48 , 50 ]. The accumulation of the safety practices and compelling employees to follow the safety measures while at work makes a safety climate in the organization.

Guo et al. [ 51 ] noted that the climate can be developed through management emphasizing safety practices. A safety climate consists of social support, management safety commitment, knowledge of safety, and pressure of production. Management’s commitment to safety has a direct relationship with social support [ 52 ]. Hence, management should establish clear policies on safety and safety issues that encourage people to follow safety standards. The present study posits that the managers with safety concerns will ensure the formulation of effective health and safety policies and procedures, provide necessary training on such policies and procedures, communicate performance standards, and promote a safety culture [ 53 ].

The safety climate is the shared perceptions of employees about the importance of safety within the organization. This is developed when the individual parts work together and develop a common sense of safety in the organization to make a system, as per social systems theory (see Figure 1 ). In the light of such arguments the hypothesis developed is:

There is a positive impact of safety management on safety climate .

2.3. Safety Climate and Safety Performance

Griffin and Neal [ 54 ] argued that employees’ perceptions of the policies, procedures, and practices relating to safety comprise the safety climate. The safety climate acts as a frame of reference for the behavior and attitudes of individuals and groups of employees, and it is argued that it will also affect their accident involvement. The employees with more favorable safety perceptions (indicating a positive safety climate) are less likely to engage in unsafe acts [ 55 ]. Safety performance is defined by Neal et al. [ 12 ] as the level of safety compliance and safety participation. Safety compliance means “adhering to safety procedures and carrying out work in a safe manner”, and safety participation means “helping co-workers, promoting the safety program within the workplace, demonstrating initiative and putting effort into improving safety in the workplace” (p. 101).

Humans play an important role in the occurrence of workplace accidents, but the safety climate can achieve excellence in prevention [ 56 ]. At the individual level, the safety climate is concerned with employees’ understanding of safety stimuli such as practices, procedures, and policies in the workplace. The safety climate, in fact, serves as a benchmark for directing and guiding suitable and adaptive safety behavior [ 57 ].

Guo et al. [ 51 ] believe that if individuals have favorable perceptions of safety, they are less likely to act unsafely on site. As a result, accident rates are likely to decline. As such, a safety climate can cause a profound change in employees’ behavior and mentality, leading to true safety implementation, thus enhancing safety performance. Borgheipour et al. [ 52 ] found a positive result for a safety climate influencing safety performance. The safety climate inculcates danger-avoiding practices and improves safety performance. The safety climate encourages employees to learn safety practices, thus fostering safety performance.

Jafari et al. [ 58 ] worked on the development of the safety climate scale and found 10 dimensions, namely management commitment, workers’ empowerment, communication, blame culture, safety training, job satisfaction, an interpersonal relationship, supervision, continuous improvement, and a reward system, to be effective in making the safety climate. Management commitment to safety and safety training make people capable of better safety performance. Eskandari et al. [ 59 ] developed a scale for measuring safety performance. They considered three factors for their examination, such as the organizational factors, the environmental factors, and the individual factors. They found organizational factors had the highest contribution toward safety performance. A safe climate is rightly considered an organizational factor that encompasses a common understanding of safety among employees.

A safety climate, that is, the common perceptions and attitudes of the employees about ensuring safety practices in the organization at a given point in time [ 46 ], leads to minimizing errors at work. This further leads to efficient working and low waste-age of resources, thus ensuring safety performance in the organization. Clarke [ 60 ] stated that the assumption underlying the link between an organizational safety climate and the accident rate is that climate provides guidance on suitable organizational behavior, so that a more positive climate encourages safe behaviors through organizational rewards (e.g., recognition and feedback for making safety suggestions), while a more negative safety climate reinforces unsafe behaviors by removing incentives to improve safety (e.g., prioritizing production over safety), which, in turn, are related to the occurrence of workplace accidents.

The social identity theory posits that positive corporate responsibility perceptions like providing safety training to the stakeholders, i.e., employees, having frequent communication, and so forth, leads to safety performance. The safety ensured in work leads to organizational identification. People tend to work in the organizations characterized by safety [ 61 ]. The hypothesis developed is:

There is a positive impact of a safety climate on safety performance .

2.4. Safety Consciousness and Safety Performance

The employees’ knowledge about safety standards encourages them to ensure safety performance. Worker engagement in safety may systematically act to reduce the probability of human errors from occurring by making workers more involved with and aware of their tasks/surroundings and associated risks, as well as the error traps that could be present. Thus, increased levels of worker engagement in safety activities could possibly be related to increased safety performance as measured by standard safety outcomes, i.e., accident rates [ 38 ].

Knowledge about safety standards and practices leads to enhanced levels of cognitive engagement [ 62 ]. The employees display focus, attention, and concentration on the safety aspects of the job. By displaying safety behavior, the employees working in the organization are known to be safety-minded people. Safety mindedness leads to leading others by example. They are the ones who are fond of continuous learning. They respond to feedback quickly and have strong communication skills. Safety-conscious people try not to harm others and make people learn safety practices by adopting safety organizational citizenship behaviors [ 63 ]. A positive safety climate is developed when the employees have a perception of management safety values and commitment to safety [ 48 ].

Safety consciousness refers to an “individual’s own awareness of safety issues” [ 11 ]. This awareness works on both a cognitive and a behavioral level. Cognitively, safety consciousness means being mentally aware of safety in your work and knowing what behaviors foster operational safety. Behaviorally, safety consciousness enacts the behaviors that foster operational safety. Safety consciousness can be separated from the safety climate in a manner that safety consciousness is about the safety of oneself, whereas a safety climate is about the safety of the whole workplace in the organization. We argue that the extent to which the individuals are aware of the safety hazards and are aware of possibly avoiding them indicates whether they are in a better position to minimize the accidents, i.e., the safety performance. Safety performance is the extent to which companies are able to prevent accidents and errors.

Kelloway et al. [ 64 ] argued that if anything could reduce the chances of accidents, it would be employees’ awareness of issues that threaten safety, their knowledge of how to prevent them, and their behaviors oriented toward preventing them (i.e., safety consciousness). Safety consciousness comes from the segments of the organization working together. Individuals, when seeing one another following the safety principles, tend to adopt safe work practices, which thus resembles the social systems theory. In light of the above arguments, the hypothesis developed is:

There is a positive impact of safety consciousness on safety performance .

2.5. Responsible Leadership as Moderator for Safety Consciousness and Safety Performance

Clarke [ 60 ] noted that “there is very limited understanding of the impact of leadership styles on safety outcomes” (p. 1175). Except for a transformational leadership style, empowering leadership, and safety leadership, which drew more research attention, leadership styles have not been adequately investigated in this context [ 65 , 66 , 67 ]. Many argue that leaders are the prime drivers of high-reliability organizations (i.e., [ 68 ]). For example, top management is often responsible for the implementation of safety-enhancing systems and the development of a safety-oriented culture. When the responsible leaders weigh different stakeholder claims before deciding, it helps in building trust and people feel free to share their safety problems and seek solutions. This enhances safety consciousness and ensures safety performance. Rare evidence is available in the literature explaining responsible leadership with relation to safety outcomes. However, it is possible that when the leaders act as role models, as per social exchange theory, the people adopt the same behaviors as their role models [ 69 ]; this boosts safety compliance and performance.

Abbas et al. [ 70 ] argued that employees are the critical stakeholders of organizations and are responsible for protecting the organizational environment via their safety mindfulness and interpersonal interaction. The safety of mindfulness and interactions are shaped by the responsible leader’s powerful forces of protection, acquisition, connection, and understanding [ 71 ]. In the presence of reinforcement from the responsible leaders, this mindfulness further leads to better safety performance.

Responsible leadership significantly moderates the relationship between safety consciousness and safety performance .

2.6. Responsible Leadership as Moderator for Safety Climate and Safety Performance

Leaders demonstrate normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships and promote such conduct to subordinates through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making [ 72 ]. Rare evidence is available for responsible leaders influencing the safety outcomes. However, this mechanism can be explained as responsible leadership being characterized as involving stakeholders in decision-making and looking after their demands. Moreover, he has an idea of the consequences of his decisions on the stakeholders. This enables the employees to get involved in the safety procedures and they conduct periodic checks on the execution of the prevention plans. Furthermore, they participate in evaluating the risks. This premise is based on the social exchange theory. The positive exchanges taking place between the leader and the employees lead to compliance as a matter of showing gratitude. The hypothesis developed is:

Responsible leadership significantly moderates the relationship between safety climate and safety performance .

3. Methodology

The population of the current study includes small and medium-sized pharmaceutical firms located in industrial zones of Lahore, Pakistan. A list of 100 small and medium-sized pharmaceutical firms operating in the industrial zone near Lahore, Pakistan was compiled. The criteria of the National SME Policy 2007 of Pakistan, “an enterprise with an employment size up to 250, capital of Rs. 25 million and annual sales up to Rs. 250 million”, was used for defining an SME. Out of 100 firms, 37 agreed to participate in the study; hence, these 37 firms were contacted for data collection. CEO, plant manager, production manager, quality assurance manager, quality control manager, pharmacists, technical staff, and assistant managers were contacted via Google Forms, which was shared either through email or WhatsApp. A total of 209 fully completed self-report surveys were received and used for data analysis.

3.1. Data Collection

Self-administered survey forms were used for data collection. The purpose of the survey was to analyze the behavior of respondents toward the safety management practices, safety climate, level of safety consciousness, and safety performance of their firm and responsible leadership. A non-probability, convenience sampling technique was employed for respondent selection and data collection.

3.2. Instrumentation

For the measurement of safety management, an 18-item scale was adopted from Beatriz Fernández-Muñiz et al. [ 73 ]. The safety management scale has four subcategories, namely safety policy, training in safety, communication in prevention issues, and preventive planning. For the measurement of safety consciousness, a seven-item scale was adopted from Westaby and Lee [ 9 ]. Item samples are “I always take extra time to do things safely” and “People think of me as being an extremely safety-minded”. A safety climate scale was adopted from Beatriz Fernández-Muñiz et al. [ 73 ] with seven items. Sample items are “Periodic checks conducted on execution of prevention plans and compliance level of regulations” and “Accidents and incidents reported, investigated, analyzed, and recorded”. The variable safety performances were measured with the help of an eight-item scale developed and used by Beatriz Fernández-Muñiz et al. [ 74 ]. Similarly, a scale of responsible leadership with five items was adopted from Voegtlin [ 75 ]. Sample items are “My direct supervisor demonstrates awareness of the relevant stakeholder claims” and “My direct supervisor considers the consequences of decisions for the affected stakeholders”. The survey instrument/questionnaire is attached in Appendix A .

4. Data Analysis

4.1. descriptive analysis.

Majority of data collected were from males. Out of 209 responses, 128 were males, while the remaining 81 were females. Similarly, the majority of respondents were of the age group between 30–39 and were from lower- to middle-level management categories; 14% were holding undergraduate degrees, 67% had master’s degrees, and the remaining 18% had higher-level degrees.

4.2. Common Method Variance

Self-reported data raise the issue of the potential effect of common method variance (CMV) [ 76 ]. Prior to hypothesis testing, CMV was tested using Harman’s one-factor test by loading all items into a single factor. The results revealed that 33% of the variance is explained by the single factor that is below the recommended threshold value of 50%. The result revealed that the data are free from CMV.

4.3. Scale Validation

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), also known as the measurement model, was used as an analytical strategy for the validation of the scale. CFA was conducted using AMOS 17. SM 18, and SP 7 was removed at this stage as it was not successfully loaded into its latent construct. The results of CFA provided acceptable model-fit indices and are presented in Table 1 .

Results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

β: standardized coefficient; alpha: Cronbath’s alpha; CR: composite reliability; AVE: average variance extracted.

4.4. Statistical Assumptions

The statistical assumptions including normality, reliability, and validity of the collected data were checked before hypothesis testing.

4.4.1. Normality Analysis

Univariate normality can be accessed through skewness and kurtosis indices, which should lie between the absolute value of 3 and 10, respectively [ 77 ]. The skewness values for the current data lies between −1.888 and 0.210, while kurtosis values were between −0.928 and 3.05, hence showing univariate normality in the dataset.

4.4.2. Reliability Analysis

Internal consistency and reliability of the dataset was checked using both Cronbatch’s alpha values and composite reliability. The alpha values were calculated using SPSS 20, while composite reliability measures were obtained through CFA output. The overall scale provided the alpha of 0.911 while the alpha values were between 0.903 and 0.973 and composite reliability values were between 0.907–0.975 for each latent construct. The Cronbatch’s alpha and composite reliability values for each latent construct presented in the model are given in Table 1 .

4.4.3. Validity Analysis