Volume 14 Supplement 11

Current situation and challenges for mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines - highlights of the training program by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine

- Meeting report

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2020

- Crystal Amiel Estrada 1 ,

- Masahide Usami 2 ,

- Naoko Satake 3 ,

- Ernesto Gregorio Jr 4 ,

- Cynthia Leynes 5 ,

- Norieta Balderrama 5 ,

- Japhet Fernandez de Leon 6 ,

- Rhodora Andrea Concepcion 7 ,

- Cecile Tuazon Timbalopez 8 ,

- Noa Tsujii 9 ,

- Ikuhiro Harada 10 ,

- Jiro Masuya 11 ,

- Hiroaki Kihara 12 ,

- Kazuhiro Kawahara 13 ,

- Yuta Yoshimura 2 ,

- Yuuki Hakoshima 2 &

- Jun Kobayashi 14

BMC Proceedings volume 14 , Article number: 11 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

194k Accesses

7 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Background and purpose

Mental health has emerged as an important public health concern in recent years. With a high proportion of children and adolescents affected by mental disorders, it is important to ensure that they are provided with proper care and treatment. With the goal of sharing the activities and good practices on child and adolescent mental health promotion, care, and treatment in Japan and the Philippines, the National Center for Global Health and Medicine conducted a training program on the promotion of mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines in September and November 2019.

Key highlights

The training program comprised of a series of lectures, site visits, and round table discussions in Japan and the Philippines. The lectures and site visits focused on the current situation of child and adolescent psychiatry, diagnosis of childhood mental disorders, abuse, health financing for mental disorders, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and disaster child psychiatry in both countries. Round table discussions provided an opportunity to explore the similarities and differences between the two countries in terms of the themes discussed during the lectures.

The training program identified the need to collaborate with other professionals to improve the diagnosis of mental disorders in children and adolescents and to increase the workforce capable of addressing mental health issues among children and adolescents. It also emphasized the importance of cooperation between government efforts during and after disasters to ensure that affected children and their families are provided with the care and support that they need.

Introduction

Current situation of mental health in the western pacific region.

Globally, an estimated 10 to 20% of children and adolescents are affected by mental health problems [ 1 ], with more than half occurring before the age of 14 [ 2 ]. In the Western Pacific Region, mental disorders rank third in the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) among children [ 3 ] and the prevalence of suicide attempts is high [ 4 ]. Nevertheless, despite these alarming statistics, the figures may still be underreported due to stigma and taboo which affect help seeking and reporting of mental health problems.

The Mental Health Action Plan of the World Health Organization highlighted the importance of mental health promotion especially in the early stages of life [ 5 ]. Association of South East Asian Countries (ASEAN) countries have reported that mental health education towards students was focused on coping skills whereas teacher training focused on mental illness knowledge and how to provide support to students. Despite these mental health education thrusts, there is limited medical and psychological care available in schools, thus leading to an increased interest in creating an environment that can provide mental health support to students [ 6 ].

Background and aim of the training program

Mental health has emerged as an important public health concern in recent years. In the Philippines, the Philippine Mental Health Act came into force in 2019, and it is expected that the general public will be more concerned about mental health services and rights of patients and their families. However, there are only five government hospitals with psychiatric facilities for children, 84 general hospitals with psychiatric units, 46 outpatient facilities, and only 2.0 mental health professionals per 100,000 people [ 7 ].

The population of the Philippines is estimated to be at 100,981,437 [ 8 ]. Over the past 20 years, infant mortality has decreased [ 9 ] and about a third of the entire population are under 14 years old [ 10 ]. About 27% of children under 5 years are malnourished.

Children with mental health problems are also a cause of concern in the Philippines [ 11 ]. An assessment of the Philippine mental health system reported a 16% prevalence of mental disorders among children [ 12 ]. In addition, the latest Global School-based Student Health Survey found that 16.8% of students aged 13 to 17 attempted suicide one or more times during the 12 months before the survey [ 13 ]. More recent initiatives on establishing the landscape of mental health problems include a nationwide mental health survey being conducted by the Department of Health. This is the first nationwide baseline study that will establish the prevalence of mental disorders in the Philippines. The study is ongoing and the results will be made available by the end of the year.

Despite mental health problems being a cause of concern among children and adolescents in the Philippines, health facilities and human resources for mental health remain limited. Currently, there are only 60 child psychiatrists in the Philippines, with the majority practicing in urban areas such as the National Capital Region. In addition, there are only 11 inpatient and 11 outpatient facilities for children and adolescents, while only 0.28 beds in the mental hospitals are allocated for children and adolescents [ 7 ]. With the focus on mental health increasing in the Philippines, it is expected that the medical treatment and mental health promotion needs of children and adolescents in the Philippines will increase in the future.

In Japan, the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) shares the Japanese experience in promoting public health practices and medical technology advancement to developing countries. In conjunction with this, the Department of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of Kohnodai Hospital conducts training programs focusing on child and adolescent health. In 2017, Kohnodai Hospital co-created a training program for children’s mental health in disaster-affected areas in the Philippines [ 14 ]. Continuing its thrust on improving child and adolescent mental health, Kohnodai Hospital conducted another training program in partnership with the Philippine Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. This training focused on identifying the current situation and challenges for the promotion of mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines.

The objective of this training was to share the activities and good practices on child and adolescent mental health promotion, care, and treatment in Japan and the Philippines through a series of field visits and discussions. In addition, the training aimed to create a multi-institutional network for childcare such as medical care, health, education, as well as a network of medical staff of various types of occupations between the two countries.

Outline of the training program

Training content.

The current program was composed of a training in the Philippines and in Japan. The first training was conducted in Manila, Philippines from September 11 to 13, 2019 (Table 1 ). Seven Japanese mental health professionals, one social worker, and one public health researcher were dispatched to the Philippines as part of the program. The Japanese experts, engaged in providing mental health promotion, care, and management to children and adolescents, discussed with Philippine experts common mental health issues, diagnostic techniques, and practices and protocols. In addition, site visits to mental health facilities in the Philippines were conducted as part of the program.

The second training was held in Ichikawa, Japan from November 5 to 7, 2019 (Table 2 ). The participants from the Philippines - composed of four child psychiatrists and a researcher - visited government institutions providing mental health services to children and adolescents. The activities of government institutions that provide assistance related to mental health care to children and their families, including its relationship to the community, were also presented during the training.

Participants

Nine health experts from Kohnodai Hospital, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, and University of the Ryukyus and 31 participants coming from different Philippine health, academic, government, and non-government institutions attended the first training in the Philippines. The second training was attended by five Philippine health experts from the University of the Philippines Manila College of Medicine, College of Public Health, National Center for Mental Health, and the Lung Center of the Philippines. Table 3 summarizes the profile of the participants in both training programs.

Training outcome: field observations and round table discussion

Diagnosis and prevalence of mental health problems.

In Japan, increasing cases of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), futoukou (school refusal), and child abuse are issues of major concern. In the Philippines, child abuse, ADHD, and adjustment disorder were the top primary mental health diagnoses.

Similarities were identified in both countries in terms of trend, screening, and diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders. In Japan, a significant increase in cases of ADHD and ASD has been noted in recent years. In 1975, the rate of autism was recorded at 1 in 5000 but it was found to be at 1 in 100 in a more recent survey [ 15 ]. Likewise, the Philippines has reported an increase in cases of ASD, from 500,000 cases in 2008 to 1,000,000 in 2018 [ 16 ]. In both countries, initial identification of neurodevelopmental disorders is conducted in schools. When cases are identified, the schools refer the children to hospitals for diagnosis. However, the limited number of available CAPs poses a constraint.

Japan and the Philippines also identified suicide and gaming disorders as major social issues. In the Philippines, common circumstances which are correlated with mental health issues among youth are: too much academic pressure with great difficulty balancing time and excessive use of digital devices engaging in network gaming and social media. Excessive digital device and social media use can lead to depression, breakdown of personal connectedness, and cyberbullying. The Philippines, being one of the most active users of social media sites [ 17 ], is at risk of adolescent addiction and depression. In Japan, First Person Shooting (FPS) games are popular and may pose a dangerous threat to young children.

Psychological abuse in younger children is the most common type of abuse in Japan. Younger children experience higher rates of abuse, with most deaths due to abuse perpetrated by mothers. Neighbors were found to be the most frequent to report cases of child abuse to child counseling centers. Child abuse cases in Japan can be reported to a hotline which is available 24 h a day, 7 days a week and cases are mainly handled by the child counseling center. Currently, child counseling centers are facing difficulties in coping with rapidly increasing cases of child abuse. The number of staff in child counseling centers has increased, but the addition of child counseling centers is an urgent issue since there are few specialized hospitals that can treat children’s mental health problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to child abuse.

There are more cases of online child sexual exploitation and substance abuse in the Philippines when compared to Japan. The Philippines has been identified as one of the top sources of child pornography material [ 18 ]. While cases of antisocial behavior have been decreasing recently in Japan, the Philippines has reported that it is an emerging social issue in the country. In the Philippines, an increasing trend in sexual abuse has been observed [ 18 ]. Physical abuse is likely to be underreported because corporal punishment is a commonly accepted method of disciplining Filipino children. Psychological abuse is the least recognized and reported, even though a national baseline study found that 3 of 5 children experience it [ 19 ].

The Women and Child Protection Unit (WCPUs) provide medical and psychosocial care to abused women and children in the Philippines. Trauma-informed psychosocial processing which is based on the principle of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and other therapies are utilized to treat the children brought to the CPU. There are 106 WCPUs distributed in 55 provinces across the country providing 24 h a day, 7 days a week consultation, but there is a lack of mental health professionals in all these WCPUs. Not all WCPUs have a psychiatrist, but it has been proposed to have at least one psychiatrist or psychologist for each CPU. In the meantime, social workers are being trained to process cases being handled by the CPU to address the effects of trauma. More severe cases are referred to the psychologist or psychiatrist of the unit or other government hospitals. For example, the WCPU of the National Center for Mental Health (NCMH), established in 2010, is currently headed by a general psychiatrist with two to three psychiatry residents rotating every 3 months. Most of the cases the WCPU of the NCMH cater to are victims of sexual and physical abuse.

Both countries have identified key strategies in addressing child abuse. In Japan, the national policy focused on service-oriented strategies with three key points: 1) preventing child abuse by conducting home visits; 2) early detection through a regional council for child abuse and child consultation center; and 3) by protection and independent support for abused children. Meanwhile, the Philippine Plan of Action to End Violence Against Children (PPAEVAC) focused on strengthening the administrative aspect of child abuse prevention through the following strategies: development of a national database on child abuse; conduct and utilization of relevant researches on violence against children in all settings; advocacy for laws and policies relevant to violence against children; and strengthening the capacity of Local Councils for the Protection of Children (LPCs).

Schools also play a role in preventing child abuse. The Department of Education of the Philippines has issued DepEd Order no. 40 s. 2012, also known as the Child Protection Policy. This department order describes the policy and guidelines on protecting children in school from bullying, violence, exploitation, discrimination, and abuse [ 20 ]. In Japan, when cases of abuse are discovered, the school principal handles the case.

Human resources for mental health

The lack of child psychiatrists is common in both countries. In Japan, there are 361 accredited doctors by the Japan Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Association as of June 2019. The number of child and adolescent psychiatrists in Japan are fewer when compared with the US and Europe. As of this writing, there are only 60 child psychiatrists and eight fellows in training in the Philippines, with most of the child psychiatrists practicing in Manila. Compounding the severe lack of child psychiatrists in the Philippines is the decision of some child psychiatrists to practice their profession overseas. As a response to the inadequate number of child psychiatrists in both countries, pediatricians are being trained on how to deal with patients with depression or suicidal ideation or behaviors.

Child and adolescent psychiatrists in both countries also need to go through general psychiatry for three to 4 years before they can proceed to child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP). In Japan, there is no curriculum for CAP but the certification to practice as a CAP is being administered by the Japanese Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Society (JSCAP). The curriculum for the subspecialization of CAP in the Philippines is developed and administered by the Philippine Psychiatric Association (PAP) through the Philippine Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (PSCAP). In order to be a recognized fellow, psychiatrists must pass a written and oral examination. However, the two countries differ in terms of training programs for child and adolescent psychiatry. In Japan, there is no national training program for CAPs, while there are three training programs for CAPs in the Philippines.

There is also a lack of psychologists in both countries. There are no child psychologists in Japan but there are many adult psychologists working in the field of child psychology. The Philippines also faces the challenge of having very few child psychologists in the country.

In addition to the lack of child psychiatrists and psychologists in both countries, Japan and the Philippines also lack teachers who can teach children with special needs (SPED teachers). Japan also faces increasing cases of futoukou , or children who refuse to go to school. School refusal is a complex problem and is possibly caused by several factors such as school bullying, trauma, and relationship issues. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, teachers who encounter children with behavioral problems conduct home visits to determine what kind of support, e.g. referral, the children and their family need. Some children drop out of school due to conduct problems.

Some differences in terms of the availability of mental health workers in the school setting were also noted. In Japan, all schools have a school nurse, majority have a school counselor, and some schools even have a social worker. The guidance counselors and teachers play a major role in detecting mental health problems among students and are trained to deal with mental health issues. In contrast, most of the public schools in the Philippines have nurses assigned at the division level (i.e. one nurse provides school health services for several schools). In addition, due to a lack of guidance counselors in public schools, some schools assign a school guidance teacher. However, private schools have their own school nurse and guidance counselor.

Health financing

In Japan, the national health insurance provides 100% subsidy for inpatient and outpatient medical expenses of children below junior high school age (i.e. below 15 years old) care. After junior high school, medical expenses are partially subsidized by the government (70%) and the remaining costs will be out-of-pocket (30%). However, children sometimes need to wait for 3 months to a year to see a specialist due to the overcrowding of hospital CAP units. Financial resources from the welfare section of local governments are also available to provide support to families.

In the Philippines, majority of individuals with mental health disorders pay mostly or entirely out-of-pocket for services and medicines. However, inpatient care at government hospitals is free since the care and treatment of individuals with major mental disorders such as bipolar disorder, depression, and psychosis are covered by the national health insurance [ 7 ]. Nevertheless, the Philippine Health Insurance only reimburses the first week of confinement and it is selective about the diseases it covers. Moreover, it does not cover child mental health. Upon discharge from an inpatient facility, patients can avail of free medicines from the Department of Health’s Medicine Access Program. Patients can also apply to the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) which can cover at least 3 months’ worth of free medication provided that the medical doctor will give the medical abstract. Discounts can also be applied for persons with disability (PWDs) when they purchase medicines. Outpatient cases are not subsidized by the government and patients need to pay 100% of the cost from their own pocket.

Pharmacotherapy

The same medications for ADHD, depression, and childhood depression are available in both Japan and the Philippines. Drugs for ADHD such as methylphenidate (MPH) and atomoxetine (ATX) and drugs for ASD such as risperidone (RSP) and aripiprazole (APZ) are being used in both countries. However, more medicines are available in Japan. For example, drugs such as amphetamine, guanfacine (GXR) and lisdexamfetamine (LDX) for the treatment of ADHD and pimozide for ASD are available in Japan but not in the Philippines. Unlike Japan, the Philippines does not use psychostimulants as first line drugs for ADHD treatment.

The Philippines follows the UK National Institute for Health and Care Guidelines (NICE) Clinical Guideline for Autism management for pharmacological treatment. It also emphasizes that treatment requires multidisciplinary action. The environment may play a role why children are exhibiting challenging behaviors hence it is recommended to address environmental factors prior to recommending medication.

In contrast with the Philippines, where off-label use of medicines is not commonly practiced, the off-label use of psychotropic drugs among children in Japan is common. Almost all Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA)-approved drugs are authorized for use among children in Japan. The off-label use of antipsychotics is not associated with patient refusal of the prescription; rather, the most common factor for patient refusal of medications was the belief that antidepressant use causes more harm than good. Glucose and prolactin monitoring are infrequent in children initiated with antipsychotic therapy [ 21 ]. Concern in the use of antipsychotics in pediatric patients in Japan is also limited but there is a need for psychiatrists to routinely monitor the metabolic condition of patients. Additionally, standard educational programs and practice guidelines that provide evidence-based support to psychiatrists for prescription of psychotropic drugs are needed in Japan.

Both countries reported that a special license is needed by psychiatrists to prescribe certain stimulants such as methylphenidate. However, the prescription rate of MPH in Japan is lower than that in other countries, which may be associated with the restriction policy for prescribing stimulants in Japan.

Psychosocial intervention

Both countries employed multidisciplinary teams to manage cases. The team is composed of child psychiatrists, social workers, nurses, and occupational therapists. For child abuse cases in both Japan and the Philippines, social workers serve as case managers.

Japanese CAPs are trained on different forms of psychotherapy during their training. Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), adapted from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), is widely used for abused children in Japan. In the Philippines, some social workers are trained to conduct CBT-based therapy for child abuse cases.

Charging fees for psychotherapy are unclear for both countries. Psychotherapy provided by public Japanese facilities are free. In the Philippines, government hospitals with psychiatric facilities do not charge consultation fee. In some of these hospitals, there is an initial expense for the payment of a hospital ID. Expenses for laboratory examinations are paid for by the patient.

Disaster child psychiatry

In times of disasters, children experience a wide range of mental and behavioral disturbances such as sleeplessness, fear, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder [ 22 ]. In Japan, children who were affected by the GEJE experienced long-term sleep disruption [ 23 ], with children from the affected Fukushima area exhibiting increasing numbers of suicide, child abuse, bullying, and absenteeism. Suicide risk and psychological symptoms were also observed among junior high school students 5 years after the GEJE. Children with evacuation experience and living in temporary housing had externalization symptoms. Economic disparities, the parents’ mental state and less social support may affect the children. In the Japanese experts’ experience, care for disabled children after disasters is also a challenge; children with ASD have difficulty adjusting to the crowded evacuation centers.

Evacuation centers in the Philippines are usually crowded after a disaster and this in turn, affect the mental health of the children and their family. Adding to this problem is the lack of mental health services for children in the Philippines after disasters. Due to the small number of practicing child psychiatrists in the country, adult psychiatrists have also been trained on how to deal with trauma of children after disasters and they examine child patients in some cases. Psychologists also help out during disasters. The Philippine Psychiatric Association also train people to process the trauma that children have experienced.

In the Philippines, where more than 90% of the total population identify as Christians, religion plays a major role in the social fabric and has become an important pathway for psychosocial support. Faith-based organizations have established mental health and psychosocial support services (MHPSS) especially during times of disasters, such as when Typhoon Haiyan struck in 2013 [ 24 ].

Mental health problems can impact children long after the disaster [ 25 ], hence providing mental health support is vital [ 26 ]. Following traumatic experiences such as disasters, schools, especially teachers, can play a key role in maintaining the well-being of children and adolescents [ 27 , 28 ]. Psychological first aid is described as a “ humane, supportive response to a fellow human being who is suffering and who may need support ” [ 29 ]. In Japan and the Philippines, teachers undergo training on psychological first aid (PFA) and are being trained to identify children who are traumatized. Teachers are also trained on some play sessions and storytelling they can use with the children to help them deal with their trauma. In terms of psychological preparedness, Japan does not have psychological preparedness in schools. In the Philippines, while psychological preparedness is not integrated in the curriculum, some schools conduct trainings on psychological preparedness for teachers and students alike.

Differences were also observed in terms of government response to disasters. Concerted efforts by the Japanese government facilitated an efficient response to the needs of the population affected by the disaster. The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, which occurred in 1995, was the first disaster that focused on the need for mental health care for affected individuals. Interest in volunteer activities spiked in the aftermath of this disaster. In 2011, Kokoronokea (mental healthcare in Japanese) team provided medical support specializing psychiatry during the Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) and in 2013 the Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team (DPAT) was established from this experience. The importance of providing support for carers or supporters and collaborating with educational institutions and school counselors were also vital lessons that Japan learned from the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. In contrast, the Philippine experience during the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 highlighted the need for better coordination among non- government organizations as well as between these organizations and the government.

The activities of the training program held in Japan and the Philippines successfully provided an opportunity to share the current situation on the care, diagnosis, and management of mental disorders in children and adolescents in the Philippines and Japan. In addition, the training program enabled Japanese and Philippine experts to identify similarities and differences and sharing of best practices between the two countries. The importance of creating partnerships with the religious sector was also highlighted. The training program is expected to create more opportunities for exchanging best practices on child and adolescent mental health promotion and care among countries in the future.

Clinical implication and recommendation

Based on the outcome of the roundtable discussions, it is recommended to collaborate with the societies of other practitioners such as pediatricians, psychologists, teachers, and social workers to improve the identification and diagnosis of mental disorders. In addition, training other practitioners in identifying cases of mental disorders among children and adolescents can help ease the lack of child and adolescent psychiatrists in both countries.

Further studies on pharmacotherapy dosages specific to Asian setting needs to be done. In addition, developing clinical guidelines and protocols at the country or regional levels for treating children with mental disorders is also recommended. A standard system for availing of psychotherapy including its payment schemes will also be beneficial to children and families who avail of these services.

Cooperation between government efforts pre, during and post disasters is necessary to ensure that affected children and their families are provided with the needed and appropriate care and support. It is also important to provide long-term support to ensure the well-being of children and adolescents. Likewise, psychosocial preparedness needs to be integrated into school and community activities to equip the population with the knowledge and skills that are needed before, during, and after a disaster.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Aripiprazole

Autism spectrum disorder

Association of South East Asian Nations

Atomoxetine

Child and adolescent psychiatry

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Disability-adjusted life years

Disaster Psychiatric Assistance Team

First Person Shooting

Great East Japan Earthquake

Japanese Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Society

Lisdexamfetamine

Local Councils for the Protection of Children

Mental Health Gap

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services

Methylphenidate

National Center for Global Health and Medicine

Philippine Psychiatric Association

Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office

Psychological first aid

Philippine Plan of Action to End Violence Against Children

Philippine Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Persons with disability

Risperidone

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

Women and Child Protection Unit

Child and adolescent mental health [Internet]. World Health Organization. [cited 2020 Mar 06.]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/child_adolescent/en/ .

Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s world mental health survey initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:168–76.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Baranne ML, Falissard B. Global burden of mental disorders among children aged 5–14 years. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12(1):19.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Uddin R, Burton NW, Maple M, Khan SR, Khan A. Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(4):223–33.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2013 [cited 2020 Mar 10]. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/89966/9789241506021_eng.pdf;jsessionid=3E09FA457C31F4CAF837E14AD6FD2B18?sequence=1 .

Nishio A, Kakimoto M, Bernardo TM, Kobayashi J. Current situation and comparison of school mental health in ASEAN countries. Pediatr Int. 2020;62(4):438–43.

Mental Health Atlas 2017 Member State Profile Philippines [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles-2017/PHL.pdf?ua=1 .

Philippine Statistics Authority. Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population [Internet]. Philippine Statistics Authority. 2016 [cited 2020 Mar 10]. Available from: https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-philippine-population-2015-census-population .

2017 National Demographic and Health Survey Key Findings [Internet]. Philippine Statistics Authority; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/2017%20PHILIPPINES%20NDHS%20KEY%20FINDINGS_092518.pdf .

The World Factbook: Philippines [Internet]. Central Intelligence Agency. Central Intelligence Agency; 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html#field-anchor-people-and-society-population-distribution .

Cagande C. Child Mental Health in the Philippines. Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;3(1). https://doi.org/10.2174/2210676611303010003 .

WHO-AIMS Report on Mental Health System in the Philippines [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2007 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/philippines_who_aims_report.pdf .

NCDs | Global school-based student health survey (GSHS) [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/PIH2015_fact_sheet.pdf .

Usami M, Lomboy MF, Satake N, Estrada CA, Kodama M, Gregorio ER Jr, Suzuki Y, Uytico RB, Molon MP, Harada I, Yamamoto K. Addressing challenges in children’s mental health in disaster-affected areas in Japan and the Philippines–highlights of the training program by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine. In: BMC proceedings; 2018. (Vol. 12, No. 14, pp. 1-8). BioMed Central.

Google Scholar

Weintraub K. Autism counts. Nature. 2011;479(7371):22.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lambatin LO. DOH6: Persons with autism rising [Internet]. PIA News. Philippine Information Agency; 2018 [cited 2020 Mar 09]. Available from: https://pia.gov.ph/news/articles/1006481 .

Pond R, Leeding G, Ryan Dubras W-DD. Digital 2020: 3.8 billion people use social media [Internet]. We Are Social. 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 10]. Available from: https://wearesocial.com/blog/2020/01/digital-2020-3-8-billion-people-use-social-media .

UNICEF Philippines. A Systematic Literature Review of the Drivers of Violence Affecting Children in the Philippines [Internet]. UNICEF Philippines; 2016 [cited 23 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/philippines/media/506/file/National%20Baseline%20Study%20on%20Violence%20Against%20Children%20in%20the%20Philippines:%20Systematic%20literature%20review%20of%20drivers%20of%20violence%20affecting%20children%20(executive%20summary).pdf .

Council for the Welfare of Children, UNICEF Philippines. National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children: Philippines Executive Summary [Internet]. 2016 [cited 23 March 2020]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/philippines/media/491/file/National%20Baseline%20Study%20on%20Violence%20Against%20Children%20in%20the%20Philippines:%20Results%20(executive%20summary).pdf .

Department of Education. DepEd Order No. 40 s. 2012 Child Protection Policy [Internet]. Department of Education [cited 10 Mar 2020]. Available from https://www.deped.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/DO_s2012_40.pdf .

Okumura Y, Usami M, Okada T, Saito T, Negoro H, Tsujii N, Fujita J, Iida J. Glucose and prolactin monitoring in children and adolescents initiating antipsychotic therapy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacology. 2018;28(7):454–62.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kar N. Psychological impact of disasters on children: review of assessment and interventions. World J Pediatr. 2009;5(1):5–11.

Usami M, Iwadare Y, Ushijima H, Inazaki K, Tanaka T, Kodaira M, Watanabe K, Kawahara K, Morikawa M, Kontani K, Murakami K. Did kindergarteners who experienced the great East Japan earthquake as infants develop traumatic symptoms? Series of questionnaire-based cross-sectional surveys: a concise and informative title: traumatic symptoms of kindergarteners who experienced disasters as infants. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;44:38–44.

Psychosocial Support and Children’s Rights Resource Center (PSTCRRC) and Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Network (MHPSSN). Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Philippines: Minimal Response Matrix and Mapping: Final Report [Internet]. July 2014 [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/mhpss-philippines-mapping-final-version.pdf .

Kar N. Psychosocial issues following a natural disaster in a developing country: a qualitative longitudinal observational study. Int J Disaster Med. 2006;4(4):169–76.

Article Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children's Mental Health & Disasters [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020 [cited 2020 Mar 09]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/childrenindisasters/features/disasters-mental-health.html .

Pfefferbaum B, Shaw JA. Practice parameter on disaster preparedness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(11):1224–38.

Mutch C. The role of schools in disaster preparedness, response and recovery: what can we learn from the literature? Pastoral Care Educ. 2014;32(1):5–22.

Psychological first aid: Guide for field workers [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2011 [cited 2020 Mar 09]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44615/9789241548205_eng.pdf?sequence=1 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deepest appreciation to the Philippine Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, National Center for Mental Health, Philippine General Hospital, Department of Education in the Philippines, Ichikawa City Education Center, Ichikawa City Child Care Support Section, and Ichikawa Child Consultation Center in Japan.

This program was funded by the International Promotion of Japan’s Healthcare Technologies and Services in 2019 conducted by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine under the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. Publication of this article was sponsored by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine grant (30–3).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, College of Public Health University of the Philippines Manila SEAMEO TROPMED Philippines Regional Centre for Public Health, Hospital Administration, Environmental and Occupational Health, Manila, Philippines

Crystal Amiel Estrada

Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Kohnodai Hospital, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Ichikawa, Japan

Masahide Usami, Yuta Yoshimura & Yuuki Hakoshima

Department of Psychiatry, National Center Hospital of Neurology and Psychiatry, Kodaira, Japan

Naoko Satake

Department of Health Promotion and Education, College of Public Health University of the Philippines Manila, SEAMEO TROPMED Philippines Regional Centre for Public Health, Hospital Administration, Environmental and Occupational Health, Manila, Philippines

Ernesto Gregorio Jr

College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

Cynthia Leynes & Norieta Balderrama

West Visayas State University Medical Center, Iloilo, Philippines

Japhet Fernandez de Leon

Lung Center of the Philippines, Quezon City, Philippines

Rhodora Andrea Concepcion

National Center for Mental Health, Mandaluyong City, Philippines

Cecile Tuazon Timbalopez

Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kindai University Faculty of Medicine, Osakasayama, Osaka, Japan

Office of Social Work Service, Kohnodai Hospital, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Ichikawa, Japan

Ikuhiro Harada

Department of Psychiatry, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

Jiro Masuya

Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kanazawa Medical, Ishikawa, Japan

Hiroaki Kihara

Department of Neuropsychiatry, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan

Kazuhiro Kawahara

Department of Global Health, Graduate School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan

Jun Kobayashi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MU, NS, YH, JK, ERG, and CL planned the training program. MU, NS, YH, IH, NT, HK, KK, NB, RAC, JFDL, and CL delivered presentations as part of the training program. All authors (CAE, MU, NS, ERG, CL, NB, JFDL, RAC, CT, NT, IH, JM, HK, KK, YY, YH, JK) participated in the field visits and roundtable discussions. CAE, UM, NS, NB, ERG, NT, RAC, CT, JFDL, NB, and CL contributed to the manuscript. All the authors had read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Masahide Usami .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Estrada, C.A., Usami, M., Satake, N. et al. Current situation and challenges for mental health focused on treatment and care in Japan and the Philippines - highlights of the training program by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine. BMC Proc 14 (Suppl 11), 11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-020-00194-0

Download citation

Published : 03 August 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-020-00194-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Training programs

- Health promotion

- Philippines

Filipinos face the mental toll of the Covid-19 pandemic — a photo essay

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

BY ORANGE OMENGAN

Depression, anxiety, and other mental health-related illnesses are on the rise among millennials as they face the pressure to be functional amidst pandemic fatigue. Omengan's photo essay shows three of the many stories of mental health battles, of struggling to stay afloat despite the inaccessibility of proper mental health services, which worsened due to the series of lockdowns in the Philippines.

“I was just starting with my new job, but the pandemic triggered much anxiety causing me to abandon my apartment in Pasig and move back to our family home in Mabalacat, Pampanga.”

This was Mano Dela Cruz's quick response to the initial round of lockdowns that swept the nation in March 2020.

Anxiety crept up on Mano, who was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder traits. The 30-year-old writer is just one of many Filipinos experiencing the mental health fallout of the pandemic.

Covid-19 infections in the Philippines have reached 1,149,925 cases as of May 17. The pandemic is unfolding simultaneously with the growing number of Filipinos suffering from mental health issues. At least 3.6 million Filipinos suffer from mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, according to Frances Prescila Cuevas, head of the National Mental Health Program under the Department of Health.

As the situation overwhelmed him, Mano had to let go of his full-time job. “At the start of the year, I thought I had my life all together, but this pandemic caused great mental stress on me, disrupting my routine and cutting my source of income,” he said.

Mano has also found it difficult to stay on track with his medications. “I don’t have insurance, and I do not save much due to my medical expenses and psychiatric consultations. On a monthly average, my meds cost about P2,800. With my PWD (person with disability) card, I get to avail myself of the 20% discount, but it's still expensive. On top of this, I pay for psychiatric consultations costing P1,500 per session. During the pandemic, the rate increased to P2,500 per session lasting only 30 minutes due to health and safety protocols.”

The pandemic has resulted in substantial job losses as some businesses shut down, while the rest of the workforce adjusted to the new norm of working from home.

Ryan Baldonado, 30, works as an assistant human resource manager in a business process outsourcing company. The pressure from work, coupled with stress and anxiety amid the community quarantine, took a toll on his mental health.

Before the pandemic, Ryan said he usually slept for 30 hours straight, often felt under the weather, and at times subjected himself to self-harm. “Although the symptoms of depression have been manifesting in me through the years, due to financial concerns, I haven't been clinically diagnosed. I've been trying my best to be functional since I'm the eldest, and a lot is expected from me,” he said.

As extended lockdowns put further strain on his mental health, Ryan mustered the courage to try his company's online employee counseling service. “The free online therapy with a psychologist lasted for six months, and it helped me address those issues interfering with my productivity at work,” he said.

He was often told by family or friends: “Ano ka ba? Dapat mas alam mo na ‘yan. Psych graduate ka pa man din!” (As a psych graduate, you should know better!)

Ryan said such comments pressured him to act normally. But having a degree in psychology did not make one mentally bulletproof, and he was reminded of this every time he engaged in self-harming behavior and suicidal thoughts, he said.

“Having a degree in psychology doesn't save you from depression,” he said.

Depression and anxiety are on the rise among millennials as they face the pressure to perform and be functional amid pandemic fatigue.

Karla Longjas, 27, is a freelance artist who was initially diagnosed with major depression in 2017. She could go a long time without eating, but not without smoking or drinking. At times, she would cut herself as a way to release suppressed emotions. Karla's mental health condition caused her to get hospitalized twice, and she was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder in 2019.

“One of the essentials I had to secure during the onset of the lockdown was my medication, for fear of running out,” Karla shared.

With her family's support, Karla can afford mental health care.

She has been spending an average of P10,000 a month on medication and professional fees for a psychologist and a psychiatrist. “The frequency of therapy depends on one's needs, and, at times, it involves two to three sessions a month,” she added.

Amid the restrictions of the pandemic, Karla said her mental health was getting out of hand. “I feel like things are getting even crazier, and I still resort to online therapy with my psychiatrist,” she said.

“I've been under medication for almost four years now with various psychologists and psychiatrists. I'm already tired of constantly searching and learning about my condition. Knowing that this mental health illness doesn't get cured but only gets manageable is wearing me out,” she added. In the face of renewed lockdowns, rising cases of anxiety, depression, and suicide, among others, are only bound to spark increased demand for mental health services.

MANO DELA CRUZ

Writer Mano Dela Cruz, 30, is shown sharing stories of his manic episodes, describing the experience as being on ‘top of the world.’ Individuals diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II suffer more often from episodes of depression than hypomania. Depressive periods, ‘the lows,’ translate to feelings of guilt, loss of pleasure, low energy, and thoughts of suicide.

Mano says the mess in his room indicates his disposition, whether he's in a manic or depressive state. “I know that I'm not stable when I look at my room and it's too cluttered. There are days when I don't have the energy to clean up and even take a bath,” he says.

Mano was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type II in 2016, when he was in his mid-20s. His condition comes with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder traits, requiring lifelong treatment with antipsychotics and mood stabilizers such as antidepressants.

Mano resorts to biking as a form of exercise and to release feel-good endorphins, which helps combat depression, according to his psychiatrist.

Mano waits for his psychiatric consultation at a hospital in Angeles, Pampanga.

Mano shares a laugh with his sister inside their home. “It took a while for my family to understand my mental health illness,” he says. It took the same time for him to accept his condition.

RYAN BALDONADO

Ryan Baldonado, 30, shares his mental health condition in an online interview. Ryan is in quarantine after experiencing symptoms of Covid-19.

KARLA LONGJAS

Karla Longjas, 27, does a headstand during meditative yoga inside her room, which is filled with bottles of alcohol. Apart from her medications, she practices yoga to have mental clarity, calmness, and stress relief.

Karla shares that in some days, she has hallucinations and tries to sketch them.

In April 2019, Karla was inflicting harm on herself, leading to her two-week hospitalization as advised by her psychiatrist. In the same year, she was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. The stigma around her mental illness made her feel so uncomfortable that she had to use a fake name to hide her identity.

Karla buys her prescriptive medications in a drug store. Individuals clinically diagnosed with a psychosocial disability can avail themselves of the 20% discount for persons with disabilities.

Karla Longjas is photographed at her apartment in Makati. Individuals diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) exhibit symptoms such as self-harm, unstable relationships, intense anger, and impulsive or self-destructive behavior. BPD is a dissociative disorder that is not commonly diagnosed in the Philippines.

This story is one of the twelve photo essays produced under the Capturing Human Rights fellowship program, a seminar and mentoring project

organized by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism and the Photojournalists' Center of the Philippines.

Check the other photo essays here.

Larry Monserate Piojo – “Terminal: The constant agony of commuting amid the pandemic”

Orange Omengan – “Filipinos face the mental toll of the Covid-19 pandemic”

Lauren Alimondo – “In loving memory”

Gerimara Manuel – “Pinagtatagpi-tagpi: Mother, daughter struggle between making a living and modular learning”

Pau Villanueva – “Hinubog ng panata: The vanishing spiritual traditions of Aetas of Capas, Tarlac”

Bernice Beltran – “Women's 'invisible work'”

Dada Grifon – “From the cause”

Bernadette Uy – “Enduring the current”

Mark Saludes – “Mission in peril”

EC Toledo – “From sea to shelf: The story before a can is sealed”

Ria Torrente – “HIV positive mother struggles through the Covid-19 pandemic”

Sharlene Festin – “Paradise lost”

PCIJ's investigative reports

THE SHRINKING GODS OF PADRE FAURA | READ .

7 MILLION HECTARES OF PHILIPPINE LAND IS FORESTED – AND THAT'S BAD NEWS | READ

FOLLOWING THE MONEY: PH MEDIA LESSONS FOR THE 2022 POLL | READ

DIGGING FOR PROFITS: WHO OWNS PH MINES? | READ

THE BULACAN TOWN WHERE CHICKENS ARE SLAUGHTERED AND THE RIVER IS DEAD | READ

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Mental health in a time of pandemic: The invisible suffering

MANILA, Philippines—The observation this year of National Mental Health Week could not have come at a more relevant time.

National Mental Health Week—observed annually in the Philippines every second week of October—used to be held every January and September.

Mental health, as defined by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is a person’s emotional, psychological and social wellbeing.

World Health Organization (WHO) said it is an “integral and essential component of health” which helps a person realize his or her own abilities to handle or cope with stress, relate to others, and make healthy choices.

In 1954, then-President Ramon Magsaysay signed Proclamation No. 37 and declared the third week of September of every year as National Mental Health Week.

“[A] sound mental health is necessary to the attainment of individual happiness and efficiency, to the establishment of peace and order, and to the promotion of economic and cultural progress,” the proclamation read.

However, the Magsaysay proclamation was revoked when former President Carlos P. Garcia signed Proclamation No. 432 in 1957 and moved the annual observation of mental health awareness to every third week of January of every year.

Proclamation No. 452, signed by then-President Fidel V. Ramos, superseded the 1957 proclamation in 1994.

Ramos’ proclamation stated that National Mental Health Week should be observed every second week of October of every year. This was the version that remained until now.

This coincided with the annual observation of World Mental Health Day held every October 10—designated by the World Federation for Mental Health (WFMH) nearly 30 years ago and recognized by WHO.

“First World Mental Health Day’s celebration has triggered more active international communications, which lead to a stronger cooperation worldwide among the participating organizations,” Proclamation No. 452 stated.

“[A] synchronized worldwide celebration will get more public attention and support for mental health work and it has become expedient to be more in accord with the celebration of the World Mental Health Day to change the date of celebration of the National Mental Health Week,” it added.

In observation of what used to be mental health week in the country, INQUIRER.net will try to discuss the mental health condition of many individuals in the Philippines—especially amid the ongoing COVID pandemic.

Battling mental health amid pandemic

As SARS-COV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—spread across the world, people reported feeling afraid, worried, and stressed—all of which WHO explained were normal responses to perceived or real threats, especially at times of uncertainty.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

The University of the Philippines Diliman Psychosocial Services (UPD PsycServ) explained that the mix of emotions felt and experienced by many during the pandemic are normal.

According to UPD PsycServ, factors like quarantine, physical distancing, bad or negative news, lack of certainty, health risks, and the lack of supplies or basic needs amid the pandemic can make people go through so many emotions.

The pandemic does not only trigger normal responses to threats, it has also triggered mental health conditions and exacerbated existing ones among many people.

“Many people may be facing increased levels of alcohol and drug use, insomnia, and anxiety,” said WHO.

COVID-19, WHO said, has increased the demand for mental health services worldwide.

The Philippines’ Department of Health (DOH), citing data from the WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health, said at least 3.6 million Filipinos suffer from one kind of mental, neurological, and substance abuse disorder in the early part of 2020.

Data presented by the National Mental Health Program (NMHP) showed at least 1,145,871 individuals in the country have depressive disorder, 520,614 with bipolar disorder, and 213, 422 said they have schizophrenia.

“This is an understatement,” said DOH NMHP head Frances Prescilla Cuevas.

“This is just a figure [that is] underreported because it only tackles a few of the conditions,” she added.

Figures from several other studies further highlighted the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of many individuals.

The DOH reported last year that the number of calls received by the hotlines of the National Center for Mental Health (NCMH) regarding mental health concerns—including suicide—has spiked during the pandemic.

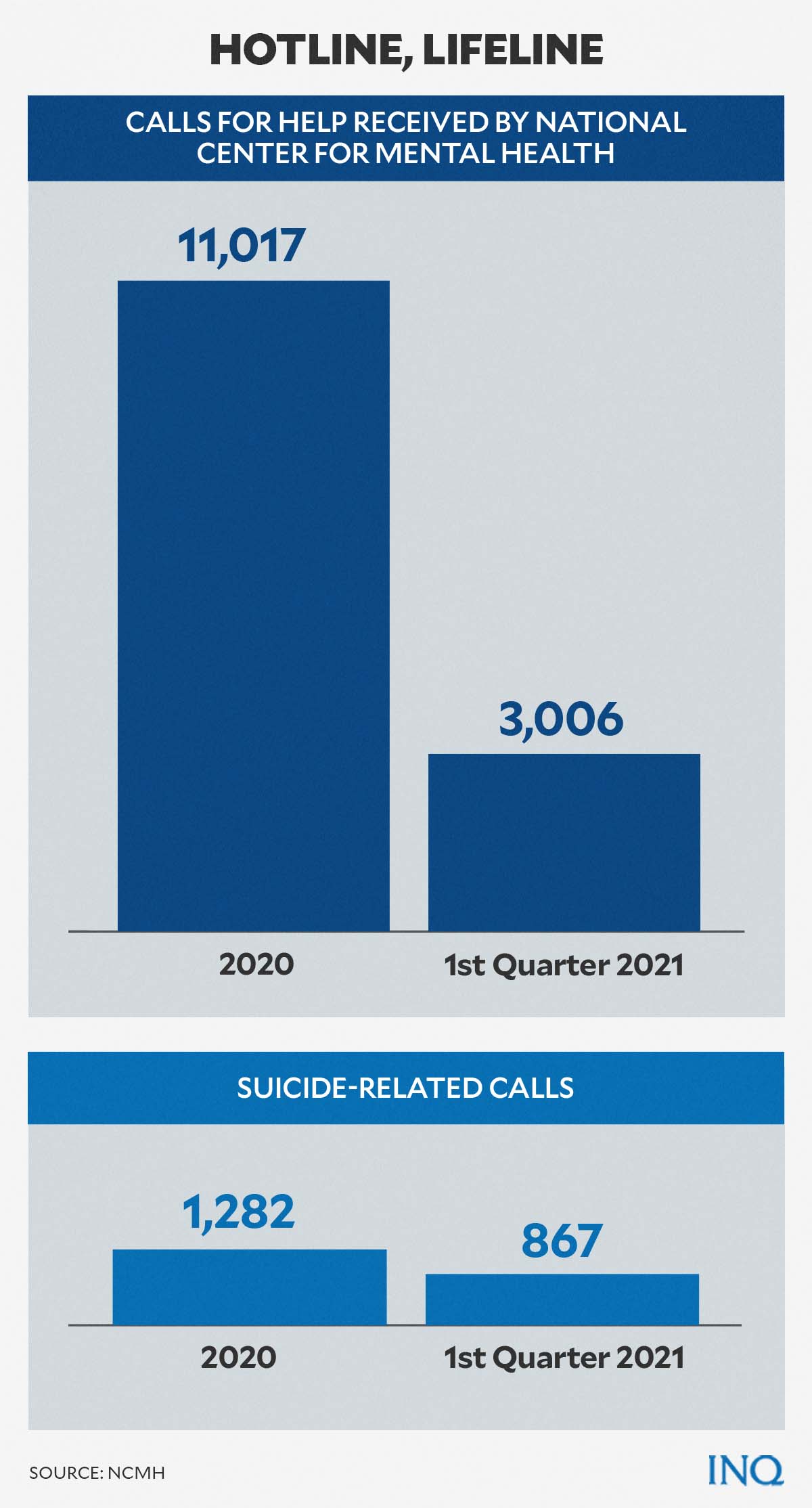

During the first quarter of 2021, the NCMH provided assistance to 3,006 individuals who called its hotlines. Meanwhile, there were 867 suicide-related calls during the same period.

READ: Mental health, suicide hotline calls up in 1Q 2021 — DOH

In 2020, the NCMH received 11,017 calls seeking mental health assistance, while 1,282 were suicide-related calls.

READ: The crisis within: Suicides rise as COVID takes its toll on lives, livelihood

At an online briefing last August, Dr. Agnes Joy Casiño, a psychiatrist and Department of Health (DOH) consultant, said that a study conducted by UP in 2020 showed that a quarter of 1,879 respondents reported having “moderate to severe” anxiety issues due to COVID concerns.

A sixth of respondents said they had “moderate to severe” depression, as the pandemic continued to have a significant psychological impact on their lives.

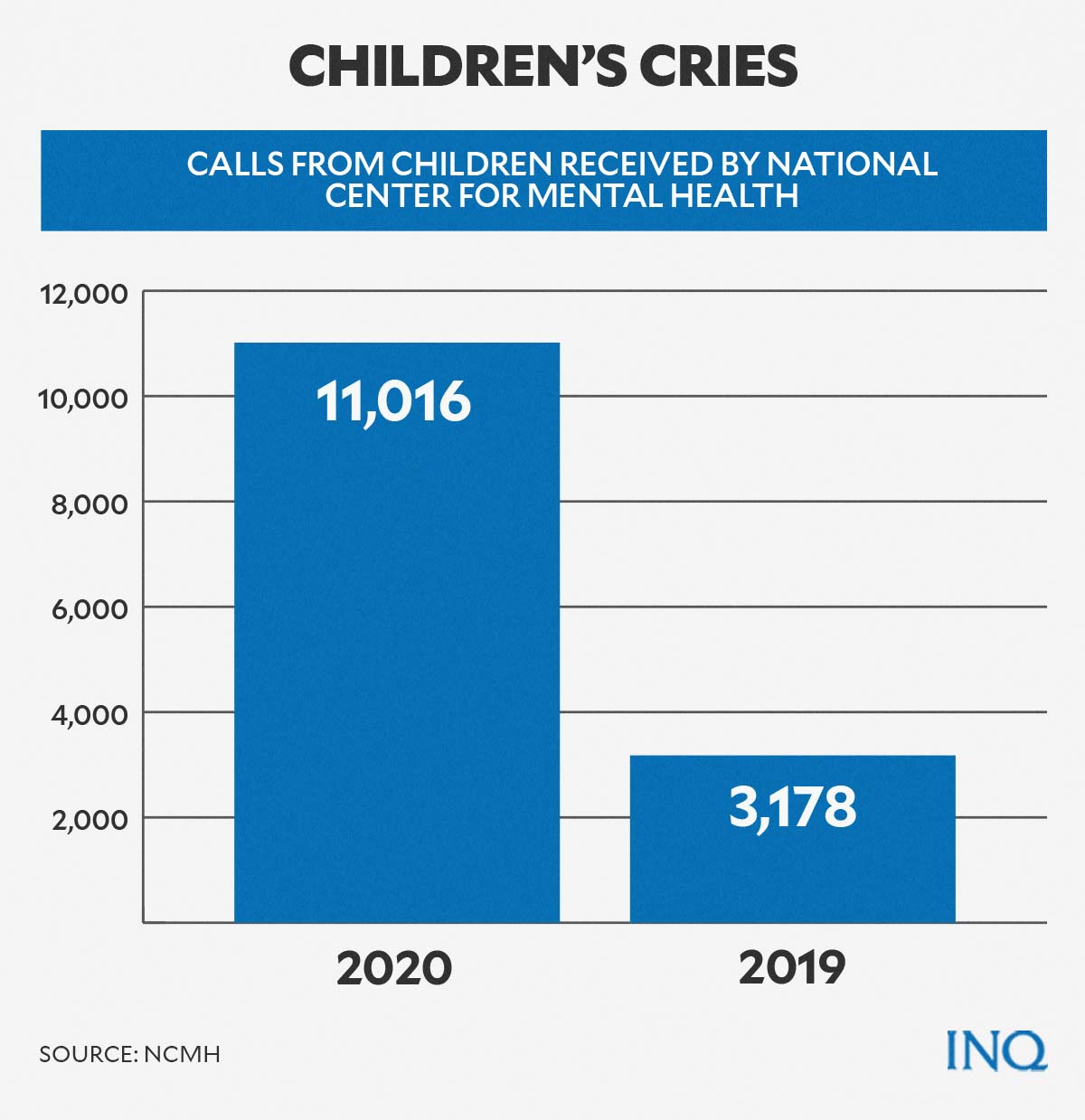

Casiño also noted that it was “alarming” that many calls received by mental health hotlines during the pandemic came from adolescents.

[T]he younger ones are calling and they want to talk to someone about their mental health,” she said.

Data from the NCMH detailed that the number of calls from children seeking help spiked by 347 percent from 3,178 in 2019 to 11,016 in 2020.

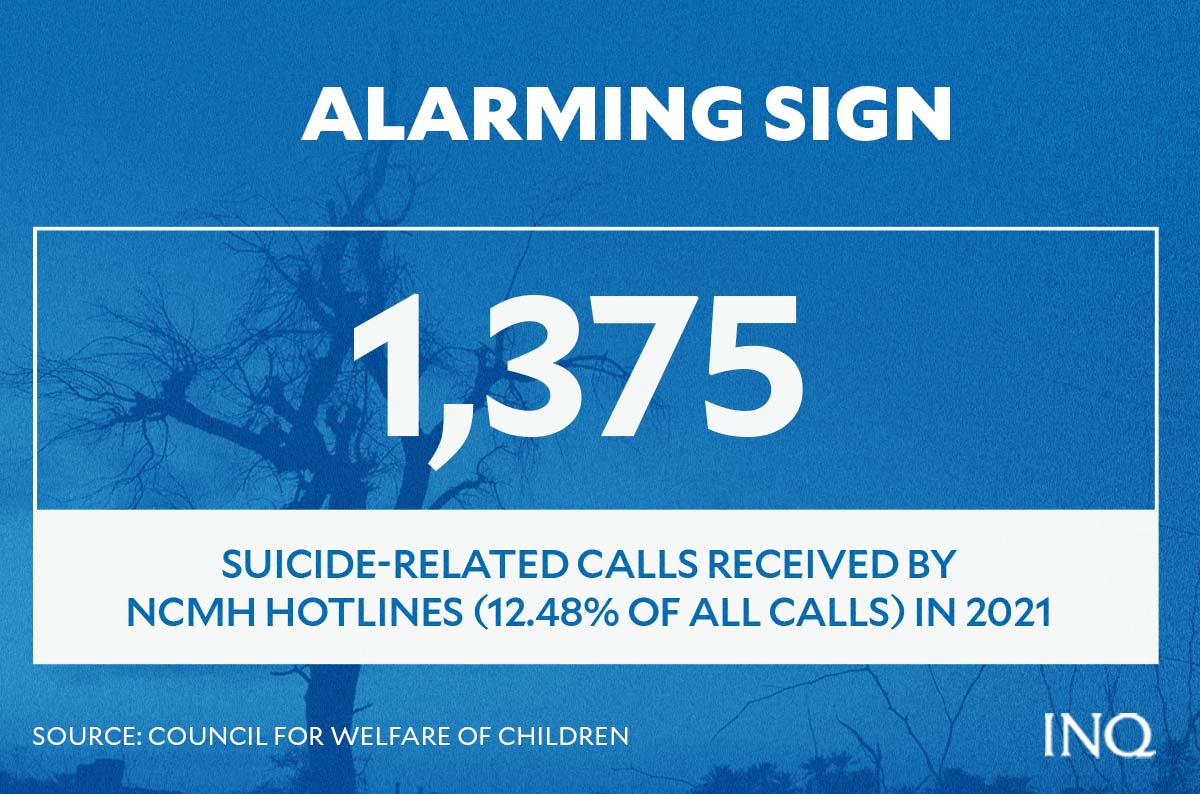

The Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC) said that it was alarming, given that 12.48 percent—or at least 1,375—of the total number of calls received last year were classified as suicide-related calls.

In October last year, the group Samahan ng Progresibong Kabataan reported 17 suicide cases among students last school year.

READ: National Children’s Month: Cause for celebration or worry?

“The COVID-19 pandemic has evoked overwhelming reactions and emotions from people,” said Health Secretary Francisco Duque III in a statement.

“Many have had their livelihoods affected, others are worried about keeping their families safe. There are many reasons why we need to take extra care now when it comes to mental health,” he added.

About death and grief

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken the lives of many individuals since 2020. As of Jan. 23 this year, the DOH has recorded 53,473 COVID deaths.

Mental health issues have also claimed many lives during the ongoing global health pandemic.

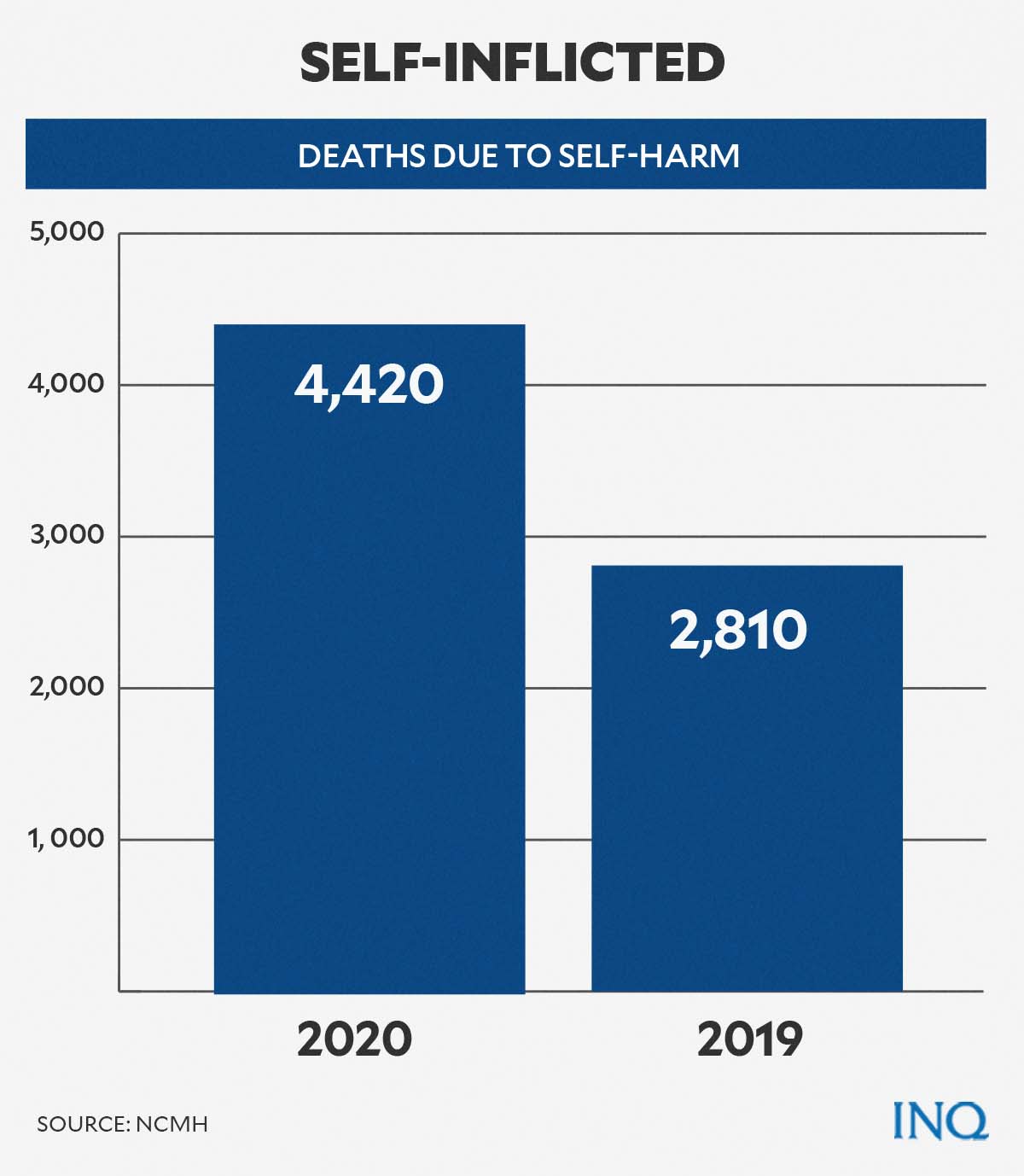

In 2020, at least 4,420 people in the Philippines died due to intentional self-harm, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

The numbers were 57 percent higher than that in 2019 with 2,810 suicide-related deaths.

The uptick has brought suicide as the 25th leading cause of death in 2020, six notches higher than in 2019 when it ranked 31st.

Dr. Natalia Skritskaya—researcher and clinical psychologist—and Katherine Shear—clinical researcher and a professor of psychiatry—both explained that having “survivor guilt” can be very common in the pandemic.

Grief in the time of the pandemic, however, was not only due to the death of a loved one, a friend, a neighbor, and other people who did not survive the dreaded disease.

“Survivor guilt is a very common feeling of discomfort or guilt because you are alive and well when someone else has died,” Skritskaya and Shear wrote in an article published by the Anxiety & Depression Association America (ADAA).

“This can be especially pronounced in situations like Covid where it seems random and unfair that one person dies and other lives,”

Grief, according to the UPD PsycServ, was also felt and experienced by people who have lost their jobs, livelihood, opportunities, freedom, and others.

“During these times, we are all experiencing grief,” the UPD PsycServ said in a Facebook post written in Filipino.

“We are not just grieving over those who died from COVID-19. Some are grieving because we lost our dreams, we lost our ambitions. We have even lost the previous life that we led,” Casiño added.

The UPD PsycServ reminded the public that no matter the root of a person’s grief is, experiencing and feeling it was natural and that there is no such thing as normal length for a person’s grieving period.

According to CDC, grief is “a normal response to a loss during or after a disaster or other traumatic event” and it can happen “in response to a loss of life, as well as drastic changes to daily routines and ways of life that usually bring us comfort and a feeling of stability.”

Some of the signs tied with grief include shock, disbelief, or denial, as well as anxiety, distress, anger, periods of sadness, and loss of sleep and appetite.

Grief that is caused by deaths or unemployment and other factors may happen at the same time. When this happens, a person might suffer prolonged grief—which in turn can further delay a person’s ability to adapt, heal, and recover.

Still, there are many ways a person can cope and overcome grief during a pandemic.

Your mental health matters

When it comes to facing and processing grief, the UPD PsycServ gave the following advice:

- Be kind and remember that people experience grief in different ways.

- Try to balance negative and positive thoughts.

- Reach out to loved ones or those who care or love us.

- Take care of our physical health.

- Focus on things and activities that can make us feel better and relaxed.

- Practice mindfulness.

- Gather strength and comfort through faith.

- Talk and consult with mental health professionals.

“Having and feeling different emotions is part of the grieving process. Let us face our sadness, anger, regret, happiness, and love since all of these can help remind us how important our deceased loved ones are in our lives,” the UPD PsycServ said in a Facebook post written in Filipino.

Paano natin haharapin ang pagdadalamhati sa panahon ng COVID-19?Research and content by: Sheila MartinezContent… Posted by UPD PsycServ on Tuesday, June 2, 2020

The Foundation for Advancing Wellness, Instruction and Talents (AWIT) listed warning signs to watch out for when checking on someone who may commit intentional self-harm.

These warning signs include:

- When one threatens to kill himself, saying that they wish to die.

- When one behaves in ways that are life-threatening or dangerous.

- When one attempts to set possessions in order and make contact with people they have not spoken with after a long time.

“It’s not easy reading about somebody suffering to the point of contemplating suicide,” the UPD PsycServ said.

“When somebody posts about it on social media, it can make us feel anxious and not know how to help. Even more so when the person who posts is somebody unknown to us and doesn’t want to be identified,” it added.

Here are some things to do, according to the organization, when you read or see a suicide post online:

- Show empathy and compassion if you’re planning to send a message.

- Avoid sending messages that might invalidate the person’s problems or feelings.

- Avoid making wholesale promises of rescue.

- Calmly and gently encourage the person to call crisis hotlines.

WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU READ A STRANGER’S SUICIDE POST ONLINEIt’s not easy reading about somebody suffering to the point… Posted by UPD PsycServ on Tuesday, April 20, 2021

There are three things to remember which can help manage mental health during the pandemic.

The UPD PsycServ reminded the public that it is important to take a break every now and then.

Slowing down and taking breaks can help limit worry and agitation, especially when watching or listening to media coverage “becomes too overwhelming.”

It also advised people to make time to connect with friends, family, and loved ones—and be open about feelings and concerns.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Lastly, the UPD PsycServ suggested the release of endorphins “through exercise or physical activities.” Endorphins are hormones released by the brain and are associated with feelings of happiness.

“Don’t forget to take care of your body by sleeping and eating healthy.”

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, it's hard to avoid feeling worried, sad, anxious, and scared. Don't worry, it's normal to… Posted by UPD PsycServ on Monday, March 23, 2020

The NCMH can be reached via its crisis hotlines: 1553 (landline), 0966-3514518 or 0917-8998727 for Globe and TM subscribers; and 0908-639-2672 for Smart, Sun and Talk N Text subscribers.

RELATED STORIES:

‘end the stigma—all feelings are valid’ , let’s talk about mental health .

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here. What you need to know about Coronavirus. For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link .

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Paying attention to mental health

It’s true that mental illness is no longer a taboo topic that can only be discussed in whispers. The COVID-19 pandemic, which has increased anxiety and cases of other mental health issues, has indeed helped bring it to the national conversation and made the public more open-minded and aware that it is a condition that must be treated like any other disease. But it is also true that barriers remain, foremost of which is the steep cost of treatment that makes it still unaffordable to many poor Filipinos.

At least 3.6 million Filipinos, based on 2020 data from the Department of Health, suffer from mental illness and this number is most likely to have increased in the past three years. Yet, per findings of a study by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative recently published in this paper, many Filipinos struggling with mental health issues still refuse or hesitate to seek treatment because they believe it is too expensive. It does not help that despite progress made in raising public awareness, there remains a stigma to mental illness, and it is still generally considered a lesser priority, especially among the marginalized sectors, compared to getting a job or putting food on the table—even if these factors contribute to the general well-being.

It should not be enough that the government raises public awareness about the importance of mental health but it also must put much-needed resources to help those who cannot afford treatment get the necessary medical attention. However, as figures from the national government’s annual budget would show, mental health remains an underserved sector. While there has been a 100-percent increase from the P1 billion budget in 2019, pre-pandemic, to P2.15 billion this year, this amount is a mere drop in the bucket compared to the billions earmarked for confidential and intelligence funds whose purpose is not as transparent.

To determine the importance that the government gives to mental health, one only has to take a look at the dreadful and abysmal conditions at the National Center for Mental Health (NCMH). Aside from NCMH, the Mariveles Mental Hospital in Bataan is the only other tertiary hospital that offers psychiatric care in a country with a 110 million population. Between them, there are only 4,700 beds available for psychiatric patients. It is no surprise that satellite hospitals affiliated with the NCMH across the country are overcrowded and face chronic funding problems that make it difficult to recruit staff or maintain facilities. In addition, based on World Health Organization data, for every 100,000 population, there are only 1.08 mental health beds in general hospitals, 46 out-patient facilities, four community residential facilities, and 0.41 psychiatrists. As a 2019 study published in the National Center for Biotechnology Information put it, mental health care in the Philippines “remains poorly resourced.”

The responsibility does not rest on the national government alone as local government units (LGUs) have been delegated the delivery of mental health services under a decentralized system. Under Section 38 of Republic Act No. 11036 or the Mental Health Act, LGUs are tasked to “establish or upgrade hospitals and facilities with adequate and qualified personnel, equipment and supplies to be able to provide mental health services and to address psychiatric emergencies.” Under this law, LGUs must also ensure that those in geographically isolated areas should have access to such services by providing home visits or mobile health care clinics. But this set-up, as the Philippine Council for Mental Health noted in a publication in 2019, “has yielded very little positive results in the past years i.e., inadequate, inaccessible, ineffective mental health services.” This is especially true for poorer LGUs that can barely fund other basic services and would have to depend on the national government to provide additional funding so they could fulfill their mental health mandate. Still, LGUs must step up and be more proactive in initiating mental health programs in their communities by coordinating with local schools and churches. LGUs, at their level, have more access to crucial information i.e., who needs counseling or treatment and can offer support immediately. By spreading awareness about mental health and making services more accessible at the grassroots, they can also lessen the stigma around it.

The need for a more collaborative and strategic approach to mental health has become even more urgent as the world faces the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, especially among the youth who grew up during this period. The recent increase in cases of bullying, suicide, and other mental disorders is a manifestation that mental health is equally important. If left underfunded, this would cost the country’s economic and health sectors billions more than the government has been prepared to spend or what it could afford.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Fearless views on the news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

Home / Essay Samples / World / Philippines / Mental Illness Stigma In The Philippines

Mental Illness Stigma In The Philippines

- Category: World , Sociology

- Topic: Philippines , Society

Pages: 3 (1483 words)

Views: 8348

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Communication Skills Essays

Nonverbal Communication Essays

First Impression Essays

Rogerian Argument Essays

Public Speaking Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->