- Utility Menu

- Writing Center

- Writing Program

- Designing Essay Assignments

by Gordon Harvey

Students often do their best and hardest thinking, and feel the greatest sense of mastery and growth, in their writing. Courses and assignments should be planned with this in mind. Three principles are paramount:

1. Name what you want and imagine students doing it

However free students are to range and explore in a paper, the general kind of paper you’re inviting has common components, operations, and criteria of success, and you should make these explicit. Having satisfied yourself, as you should, that what you’re asking is doable, with dignity, by writers just learning the material, try to anticipate in your prompt or discussions of the assignment the following queries:

- What is the purpose of this? How am I going beyond what we have done, or applying it in a new area, or practicing a key academic skill or kind of work?

- To what audience should I imagine myself writing?

- What is the main task or tasks, in a nutshell? What does that key word (e.g., analyze, significance of, critique, explore, interesting, support) really mean in this context or this field?

- What will be most challenging in this and what qualities will most distinguish a good paper? Where should I put my energy? (Lists of possible questions for students to answer in a paper are often not sufficiently prioritized to be helpful.)

- What misconceptions might I have about what I’m to do? (How is this like or unlike other papers I may have written?) Are there too-easy approaches I might take or likely pitfalls? An ambitious goal or standard that I might think I’m expected to meet but am not?

- What form will evidence take in my paper (e.g., block quotations? paraphrase? graphs or charts?) How should I cite it? Should I use/cite material from lecture or section?

- Are there some broad options for structure, emphasis, or approach that I’ll likely be choosing among?

- How should I get started on this? What would be a helpful (or unhelpful) way to take notes, gather data, discover a question or idea? Should I do research?

2. Take time in class to prepare students to succeed at the paper

Resist the impulse to think of class meetings as time for “content” and of writing as work done outside class. Your students won’t have mastered the art of paper writing (if such a mastery is possible) and won’t know the particular disciplinary expectations or moves relevant to the material at hand. Take time in class to show them:

- discuss the assignment in class when you give it, so students can see that you take it seriously, so they can ask questions about it, so they can have it in mind during subsequent class discussions;

- introduce the analytic vocabulary of your assignment into class discussions, and take opportunities to note relevant moves made in discussion or good paper topics that arise;

- have students practice key tasks in class discussions, or in informal writing they do in before or after discussions;

- show examples of writing that illustrates components and criteria of the assignment and that inspires (class readings can sometimes serve as illustrations of a writing principle; so can short excerpts of writing—e.g., a sampling of introductions; and so can bad writing—e.g., a list of problematic thesis statements);

- the topics of originality and plagiarism (what the temptations might be, how to avoid risks) should at some point be addressed directly.

3. Build in process

Ideas develop over time, in a process of posing and revising and getting feedback and revising some more. Assignments should allow for this process in the following ways:

- smaller assignments should prepare for larger ones later;

- students should do some thinking and writing before they write a draft and get a response to it (even if only a response to a proposal or thesis statement sent by email, or described in class);

- for larger papers, students should write and get response (using the skills vocabulary of the assignment) to a draft—at least an “oral draft” (condensed for delivery to the class);

- if possible, meet with students individually about their writing: nothing inspires them more than feeling that you care about their work and development;

- let students reflect on their own writing, in brief cover letters attached to drafts and revisions (these may also ask students to perform certain checks on what they have written, before submitting);

- have clear and firm policies about late work that nonetheless allow for exception if students talk to you in advance.

- Pedagogy Workshops

- Responding to Student Writing

- Commenting Efficiently

- Vocabulary for Discussing Student Writing

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- HarvardWrites Instructor Toolkit

- Additional Resources for Teaching Fellows

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that he or she will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove her point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, he or she still has to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and she already knows everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality she or he expects.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Write a Perfect Assignment: Step-By-Step Guide

Table of contents

- 1 How to Structure an Assignment?

- 2.1 The research part

- 2.2 Planning your text

- 2.3 Writing major parts

- 3 Expert Tips for your Writing Assignment

- 4 Will I succeed with my assignments?

- 5 Conclusion

How to Structure an Assignment?

To cope with assignments, you should familiarize yourself with the tips on formatting and presenting assignments or any written paper, which are given below. It is worth paying attention to the content of the paper, making it structured and understandable so that ideas are not lost and thoughts do not refute each other.

If the topic is free or you can choose from the given list — be sure to choose the one you understand best. Especially if that could affect your semester score or scholarship. It is important to select an engaging title that is contextualized within your topic. A topic that should captivate you or at least give you a general sense of what is needed there. It’s easier to dwell upon what interests you, so the process goes faster.

To construct an assignment structure, use outlines. These are pieces of text that relate to your topic. It can be ideas, quotes, all your thoughts, or disparate arguments. Type in everything that you think about. Separate thoughts scattered across the sheets of Word will help in the next step.

Then it is time to form the text. At this stage, you have to form a coherent story from separate pieces, where each new thought reinforces the previous one, and one idea smoothly flows into another.

Main Steps of Assignment Writing

These are steps to take to get a worthy paper. If you complete these step-by-step, your text will be among the most exemplary ones.

The research part

If the topic is unique and no one has written about it yet, look at materials close to this topic to gain thoughts about it. You should feel that you are ready to express your thoughts. Also, while reading, get acquainted with the format of the articles, study the details, collect material for your thoughts, and accumulate different points of view for your article. Be careful at this stage, as the process can help you develop your ideas. If you are already struggling here, pay for assignment to be done , and it will be processed in a split second via special services. These services are especially helpful when the deadline is near as they guarantee fast delivery of high-quality papers on any subject.

If you use Google to search for material for your assignment, you will, of course, find a lot of information very quickly. Still, the databases available on your library’s website will give you the clearest and most reliable facts that satisfy your teacher or professor. Be sure you copy the addresses of all the web pages you will use when composing your paper, so you don’t lose them. You can use them later in your bibliography if you add a bit of description! Select resources and extract quotes from them that you can use while working. At this stage, you may also create a request for late assignment if you realize the paper requires a lot of effort and is time-consuming. This way, you’ll have a backup plan if something goes wrong.

Planning your text

Assemble a layout. It may be appropriate to use the structure of the paper of some outstanding scientists in your field and argue it in one of the parts. As the planning progresses, you can add suggestions that come to mind. If you use citations that require footnotes, and if you use single spacing throughout the paper and double spacing at the end, it will take you a very long time to make sure that all the citations are on the exact pages you specified! Add a reference list or bibliography. If you haven’t already done so, don’t put off writing an essay until the last day. It will be more difficult to do later as you will be stressed out because of time pressure.

Writing major parts

It happens that there is simply no mood or strength to get started and zero thoughts. In that case, postpone this process for 2-3 hours, and, perhaps, soon, you will be able to start with renewed vigor. Writing essays is a great (albeit controversial) way to improve your skills. This experience will not be forgotten. It will certainly come in handy and bring many benefits in the future. Do your best here because asking for an extension is not always possible, so you probably won’t have time to redo it later. And the quality of this part defines the success of the whole paper.

Writing the major part does not mean the matter is finished. To review the text, make sure that the ideas of the introduction and conclusion coincide because such a discrepancy is the first thing that will catch the reader’s eye and can spoil the impression. Add or remove anything from your intro to edit it to fit the entire paper. Also, check your spelling and grammar to ensure there are no typos or draft comments. Check the sources of your quotes so that your it is honest and does not violate any rules. And do not forget the formatting rules.

with the right tips and guidance, it can be easier than it looks. To make the process even more straightforward, students can also use an assignment service to get the job done. This way they can get professional assistance and make sure that their assignments are up to the mark. At PapersOwl, we provide a professional writing service where students can order custom-made assignments that meet their exact requirements.

Expert Tips for your Writing Assignment

Want to write like a pro? Here’s what you should consider:

- Save the document! Send the finished document by email to yourself so you have a backup copy in case your computer crashes.

- Don’t wait until the last minute to complete a list of citations or a bibliography after the paper is finished. It will be much longer and more difficult, so add to them as you go.

- If you find a lot of information on the topic of your search, then arrange it in a separate paragraph.

- If possible, choose a topic that you know and are interested in.

- Believe in yourself! If you set yourself up well and use your limited time wisely, you will be able to deliver the paper on time.

- Do not copy information directly from the Internet without citing them.

Writing assignments is a tedious and time-consuming process. It requires a lot of research and hard work to produce a quality paper. However, if you are feeling overwhelmed or having difficulty understanding the concept, you may want to consider getting accounting homework help online . Professional experts can assist you in understanding how to complete your assignment effectively. PapersOwl.com offers expert help from highly qualified and experienced writers who can provide you with the homework help you need.

Will I succeed with my assignments?

Anyone can learn how to be good at writing: follow simple rules of creating the structure and be creative where it is appropriate. At one moment, you will need some additional study tools, study support, or solid study tips. And you can easily get help in writing assignments or any other work. This is especially useful since the strategy of learning how to write an assignment can take more time than a student has.

Therefore all students are happy that there is an option to order your paper at a professional service to pass all the courses perfectly and sleep still at night. You can also find the sample of the assignment there to check if you are on the same page and if not — focus on your papers more diligently.

So, in the times of studies online, the desire and skill to research and write may be lost. Planning your assignment carefully and presenting arguments step-by-step is necessary to succeed with your homework. When going through your references, note the questions that appear and answer them, building your text. Create a cover page, proofread the whole text, and take care of formatting. Feel free to use these rules for passing your next assignments.

When it comes to writing an assignment, it can be overwhelming and stressful, but Papersowl is here to make it easier for you. With a range of helpful resources available, Papersowl can assist you in creating high-quality written work, regardless of whether you’re starting from scratch or refining an existing draft. From conducting research to creating an outline, and from proofreading to formatting, the team at Papersowl has the expertise to guide you through the entire writing process and ensure that your assignment meets all the necessary requirements.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

How to Write a One Page Paper in APA Style

Writing a one-page paper in APA format is not an especially easy task, but it is indeed possible if you don't count the title page and references. If you must, then the paper has to contain all four major elements on one page. An APA-style paper consists of a title page with a running head, an abstract, the body of the paper with its various sections and/or in-text citations and/or footers and finally, the reference page. Type it in 12-point Times New Roman font, double-spaced, with one-inch margins on all sides.

Add the title at the top of the page in the header section with the words "Running head:". The title, in all caps with no bold font or typeface, is simply the topic or subject of the paper with the name of the writer and the university/entity for whom the paper is written. Single space this section at the top of the page and center it.

Type or write out the abstract. Center and bold the word "abstract." If all of the main elements of the APA-style paper are going to fit on one page, the abstract (summary) of the paper should be no more than two to three sentences long. If the mandatory "one-page" paper is not literal, then the abstract and the body are the only parts that will go on the single page. The title page with a "running" head and the reference page noted below can be separate for a total of three pages.

Type or write the body of the APA paper. The title should be repeated here, centered and in bold. It should consist of no more than two paragraphs, including in-text citations to be referenced in the footnote of the paper. There will be no room for sections in a one-page paper. Also, the resources should be narrowed down to only one of two references.

Reference the in-text citation or citations in the footnote section of the page or paper. You can single space the references with a double space between them and reverse indented. If the one-page mandate is not literal, then you can exchange the footnotes for a reference page, but you must still reverse indent them. Center the word "References" and bold it if you choose.

Things You'll Need

- Purdue's OWL Resources: Sample APA Format Paper

Renee Greene has been writing professionally since 1984 when she began as a news clerk for "The Columbus (Ga.) Ledger-Enquirer." She has written nonfiction books and a book of Haikus. She holds an associate degree from Phillips Junior College and is an English major at Mesa (Ariz.) Community College.

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.

- It encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives.

- If you have only one large paper due near the end of the course, you might create a sequence of smaller assignments leading up to and providing a foundation for that larger paper (e.g., proposal of the topic, an annotated bibliography, a progress report, a summary of the paper’s key argument, a first draft of the paper itself). This approach allows you to give students guidance and also discourages plagiarism.

- It mirrors the approach to written work in many professions.

The concept of sequencing writing assignments also allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. It is often beneficial to have students submit the components suggested below to your course’s STELLAR web site.

Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, “sequencing an assignment” can mean establishing some sort of “official” check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments.

Have students submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft.

Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other’s drafts. The students do not need to be writing on the same topic.

Require consultations. Have students consult with someone in the Writing and Communication Center about their prewriting and/or drafts. The Center has yellow forms that we can give to students to inform you that such a visit was made.

Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view.

Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students’ assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article).

Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge.

Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course.

Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. For humanities and social science courses, students might write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic, then hand in an annotated bibliography, and then a draft, and then the final version of the paper.

Have students submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section).

In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions:

Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students’ understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. STELLAR forums work well for out-of-class entries.

Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. They can write a letter to a friend explaining their concerns about an upcoming paper assignment or explaining their ideas for an upcoming paper assignment. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., “pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” or “pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church”).

Editorials . Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial for the campus or local newspaper or for a national journal.

Cases . Students might create a case study particular to the course’s subject matter.

Position Papers . Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay.

Imitation of a Text . Students can create a new document “in the style of” a particular writer (e.g., “Create a government document the way Woody Allen might write it” or “Write your own ‘Modest Proposal’ about a modern issue”).

Instruction Manuals . Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process.

Dialogues . Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal those people’s theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., “Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art”).

Collaborative projects . Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques.

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

The research process, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

The Research Assignment Introduction

When tasked with writing a research paper, you are able to “dig in” to a topic, idea, theme, or question in greater detail. In your academic career, you will be assigned several assignments that require you to “research” something and then write about it. Sometimes you can choose a topic and sometimes a topic is assigned to you.

Either way, look at this assignment as an opportunity to learn more about something and to add your voice to the discourse community about said topic. Your professor is assigning you the task to give you a chance to learn more about something and then share that newfound knowledge with the professor and your academic peers. In this way, you contribute meaningfully to the existing scholarship in that subject area. You are then creating a research space for yourself and for other researchers who may follow you.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

ENGL 101: Academic Writing: How to write a research paper

- Research Tools

- How to evaluate resources

- How to write a research paper

- Occupational Resources

How to write a research paer

Understand the topic, what is the instructor asking for, who is the intended audience, choosing a topic.

- General Research

Books on the subject

Journal articles, other sources, write the paper.

You've just been assigned by your instructor to write a paper on a topic. Relax, this isn't going to be as bad as it seems. You just need to get started. Here are some suggestions to make the process as painless as possible. Remember, if you have any questions ASK .

Is the assignment a formal research paper where you have to do research and cite other sources of information, or is the assignment asking you for your reaction to a particular topic where all you will need to do is collect your thoughts and organize them coherently. If you do need to research your topic, make sure you know what style manual your instructor prefers (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc).

Make sure you keep track of any restrictions that your instructor places on you. If your instructor wants a 4 page paper, they won't be happy with a 2 page paper, or a 10 page paper. Keep in mind that the instructor knows roughly how long it should take to cover the topic. If your paper is too short, you probably aren't looking at enough materials. If you paper is too long, you need to narrow your topic. Also, many times the instructor may restrict you to certain types of resources (books written after 1946, scholarly journals, no web sites). You don't want to automatically lessen your grade by not following the rules. Remember the key rule, if you have any questions ask your instructor!

You will also need to know which audience that you are writing for. Are you writing to an audience that knows nothing about your topic? If so you will need to write in such a way that you paper makes sense, and can be understood by these people. If your paper is geared to peers who have a similar background of information you won't need to include that type of information. If your paper is for experts in the field, you won't need to include background information.

If you're lucky, you were given a narrow topic by your instructor. You may not be interested in your topic, but you can be reasonably sure that the topic isn't too broad. Most of you aren't going to be that lucky. Your instructor gave you a broad topic, or no topic at all and you are going to have to choose the specific topic for your paper.

There are some general rules that you can use to help choose and narrow a topic. Does a particular topic interest you? If you are excited by a particular field, choose a topic from that field. While doing research you will learn more about the field, and learn which journals are written for your topic. Are you answering a relevant question? You and your instructor are going to be bored if you are writing a paper on the hazards of drunken driving. However, it might be more interesting to write about what causes people to drink and drive. The more interesting your topic the more you will enjoy and learn from writing your paper. You may also want to focus on a specific point of view about the topic, such as what teenagers think the causes of drunken driving are.

Do General Research

Now that you have a topic, it is time to start doing research. Don't jump to the card catalog and the indexes yet. The first research that you want to do is some general research on your topic. Find out what some of the terms used in the field are. You will also find that this research can help you further define you topic.

One source of general research is a general encyclopedia. Depending on the encyclopedia, at the end of each entry there may be a bibliography of suggested works. Good encyclopedias to consult are Encyclopedia Britannica , Encyclopedia Americana, and World Book.

You will also want to check to see if your topic is in a field that has a subject Encyclopedia, a Subject Handbook, or a Subject Dictionary. These guides contain information about a wide variety of topics inside a specific field. Generally the information in more detailed that what is contained in a general encyclopedia. Also the bibliographies are more extensive.

Find further information

Now that we have some background information on our topic; we need to find information about our specific topic. Before searching, ask yourself what type of information you are looking for. If you want to find statistical information, you will need to look in certain types of sources. If you are looking for news accounts of an event, you will need to look in other types of sources. Remember, if you have a question about what type of source to use, ask a librarian.

Have you asked your instructor for suggestions on where to look? Why not? This person is experienced in the field, and they have been doing research in it longer than you have. They can recommend authors who write on your topic, and they can recommend a short list of journals that may contain information on your topic.

Books are one type of resource that you can use for your research. To find a book on your topic, you will need to use the online catalog, the CamelCat . Taking the list of keywords that you created while doing general research, do keyword searches in the catalog. Look at the titles that are being returned, do any look promising? If none do, revise your search using other keywords. If one does, look at the full record for that book. Check the subject headings that it is cataloged by. If one of those headings looks pertinent to your research, do a subject search using that particular heading.

Once you've got the books that you want to use start evaluating whether the book will be useful. Is it written by an author who is knowledgeable about that particular topic? Is the author qualified to write about the topic? What biases does the author have about the topic? Is the book current enough to contain useful information?

Once you've answered these questions, use the books that you deem useful for your research. Remember while taking notes to get the information that you need to do a proper citation. Also, pay attention to any bibliographies that are included in the book. These can help you locate other books and articles that may be useful for your research.

The Campbell University Libraries subscribe to a wide variety of Indexes and Journals for the use of students and faculty. Increasingly these materials are provided as Electronic Databases. These databases contain citations of articles and in some cases the full text of articles on a variety of topics. If you don't know which database will be useful for you, ask a librarian and they will be happy to assist you. You can also use the Find Articles link to search multiple databases at one time for information on your topic.

Once you've selected a database to use, use the keywords that you developed from your general research to find articles that will be useful for you. Once you've found one, see which terms the database used to catalog the article and use those terms to find more articles. Don't forget to set limits on the database so that only scholarly articles are returned if your instructor has made that a requirement for your paper.

Look at the journal articles that you have selected, and examine the bibliographies. Are there any authors that are mentioned in more than one article? Are there any articles that are mentioned more than once? You should find those authors and articles and include them in your research.

There are other useful sources that you can use in your research. If your report tends to be on a business topic or if you need company information for your research there are many companies that provide company reports. The contents of these reports differ, depending on which service that you are using. Generally speaking you will find company officers, financial statements, lists of competitors, and stock price.

The Internet is another source for information on a variety of topics. The major problem with the using Internet resources is authority. Anybody who knows HTML can produce a web site that looks pretty decent. However, a website produced by a sophomore in high school on a topic is not going to be useful to you in your research. Before using a website for information, you need to evaluate the site. Here are some questions you will want to ask: Who created the site? (If you can't tell, don't use it.) Has the site been recently updated? Is the site promoting a specific agenda/ does it have a bias? (Bias isn't necessarily bad, but you need to keep it in mind when interpreting the information presented?) Are there any misspellings on the site? (If there is one misspelling careless error more than three, don't use the page) Do the links on the page work? (If a few don't work, not a big problem, if most of the links don't work, the site isn't being maintained, and should not be used.)

You have all of your research, now it is time to write the paper. Don't forget to cite all of the research that you have collected using the preferred citation style of your instructor. If possible try to give yourself a couple of days to let the paper sit before you edit it. Look at a hard copy of the paper and check for mechanical errors (spelling, punctuation). Also try to imagine that you are the intended audience for the paper. Does your paper make sense? Are the arguments logical? Does the evidence presented support the arguments made? If you answered no to any of these questions, make the necessary changes to your paper.

Purdue's Online Writing Lab https://owl.english.purdue.edu/

- << Previous: How to evaluate resources

- Next: MLA Style >>

- Last Updated: Aug 31, 2023 9:45 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.campbell.edu/engl101

- About Waterloo

- Faculties & academics

- Offices & services

- Support Waterloo

Research Essay

The main goal of a research paper is to investigate a particular issue and provide new perspectives or solutions. The writer uses their own original research and/or evaluation of others' research to present a unique, sound, and convincing argument.

Although the final version of a research paper should be well-organized, logical, and clear, the path to writing one is not a straight line. It involves research, critical thinking, source evaluation, organization, and writing. These stages are not linear; instead, the writer weaves back and forth, and the paper's focus and argument grows and changes throughout the process.

Click on the Timeline for a visual representation of the timeline. Click on the Checklist for a document containing the checklist items for a research essay.

Step 1: Getting Started

A: understand your assignment 1%.

Determine exactly what the assignment is asking you to do. Read the assignment carefully to determine the topic, purpose, audience, format, and length. For more information, see the Writing and Communication Centre's resource Understanding your assignment .

B: Conduct preliminary research 3%

Do some general reading about your topic to figure out:

- what are the current issues in your subject area?

- is there enough information for you to proceed?

See the Library's resource Conduct preliminary research (PDF) .

C: Narrow your topic 3%

Use traditional journalistic questions (who, what, where, when, why) to focus on a specific aspect of your topic. It will make your paper more manageable, and you will be more likely to succeed in writing something with depth. Read more about Developing and narrowing a research topic (PDF) .

D: Develop a research question 3%

A research question guides your research. It provides boundaries, so that when you gather resources you focus only on information that helps to answer your question. See the Writing and Communication Centre's resource Develop a research question (PDF) .

Step 2: Research

A: design your research strategy 5%.

List the types of literature that may contain useful information for your topic, and isolate the main concepts. Use these concepts to build a list of relevant/useful search terms. For more information, see the Library's resource on Effective research strategies (PDF) .

This Search statement worksheet (PDF) can help you organize your research strategy.

B: Find and evaluate sources 10%

Not all sources are equally useful. The content of sources you choose must be relevant and current, and you need to make sure you're using academically valid sources such as peer-reviewed journal articles and books. See the Library's resource on Evaluating your search results critically and the RADAR Evaluation Method (PDF) .

C: Conduct research 20%

Gather your information and keep careful track of your sources as you go along. See the Library's resource Conducting research and note taking (PDF) .

Step3: Organizing your essay

A: move from research to writing: how to think 8% .

This critical step involves using the information you've gathered to form your own ideas. This resource can help you get the most out of what you're reading: Reading and listening critically . You've read a good deal of information and now you have to analyze and synthesize it into something new and worth writing about. See How to think: move from research to writing (PDF) for the kind of questions that can guide you through this process.

B: Develop a thesis statement 3%

A strong thesis statement is the cornerstone of a good research essay. Your thesis needs to be clean, concise, focused, and supportable. In most cases, it should also be debatable.

C: Outline the structure of your paper 4%

Organize your ideas and information into topics and subtopics. Outline the order in which you will write about the topics. For more information on how create a good outline, see Two ways to create an outline: graphic and linear .

Step 4: Writing the first draft

Time to get writing! A first draft is a preliminary attempt to get ideas down on paper. It's okay if your ideas aren't completely formed yet. Let go of perfection and write quickly. You can revise later.

For additional help, check out the Writing and Communication Centre's resource on Writing a first draft .

Step 5: Revising and proofreading

A: evaluate your first draft and conduct additional research as needed 10%.

Determine if there are any gaps in your draft. Do you have enough evidence to support your arguments? If you don't, you should conduct further research.

B: Revise your draft 5%

Print out your paper and work from a hard copy. Read it carefully and look for higher order problems first, such as organization, structure, and argument development. For more help with these higher order issues, check out the tips for revision .

C: Evaluate your second draft and rewrite as needed 5%

Narrow your focus to paragraph-level issues such as evidence, analysis, flow, and transitions. To improve your flow and transitions, see the Writing and Communication Centre's resource on Transition words .

D: Proofread and put your paper into its final format 5%

Last step! Read carefully to catch all those small errors. Here are some tips on Proofreading strategies . Also take time to make sure your paper adheres to the conventions of the style guide you're using. Think about titles, margins, page numbers, reference lists, and citations.

The University of Waterloo's Writing and Communication Centre has a number of resources that can help you in revising and proofreading.

Tips for writing:

- Active and passive voice (PDF)

- Writing concisely (PDF)

- Writing checklist (PDF)

Style Guides:

- APA style guide (PDF)

- Chicago author-date style guide (PDF)

- IEEE style guide (PDF)

- MLA style guide

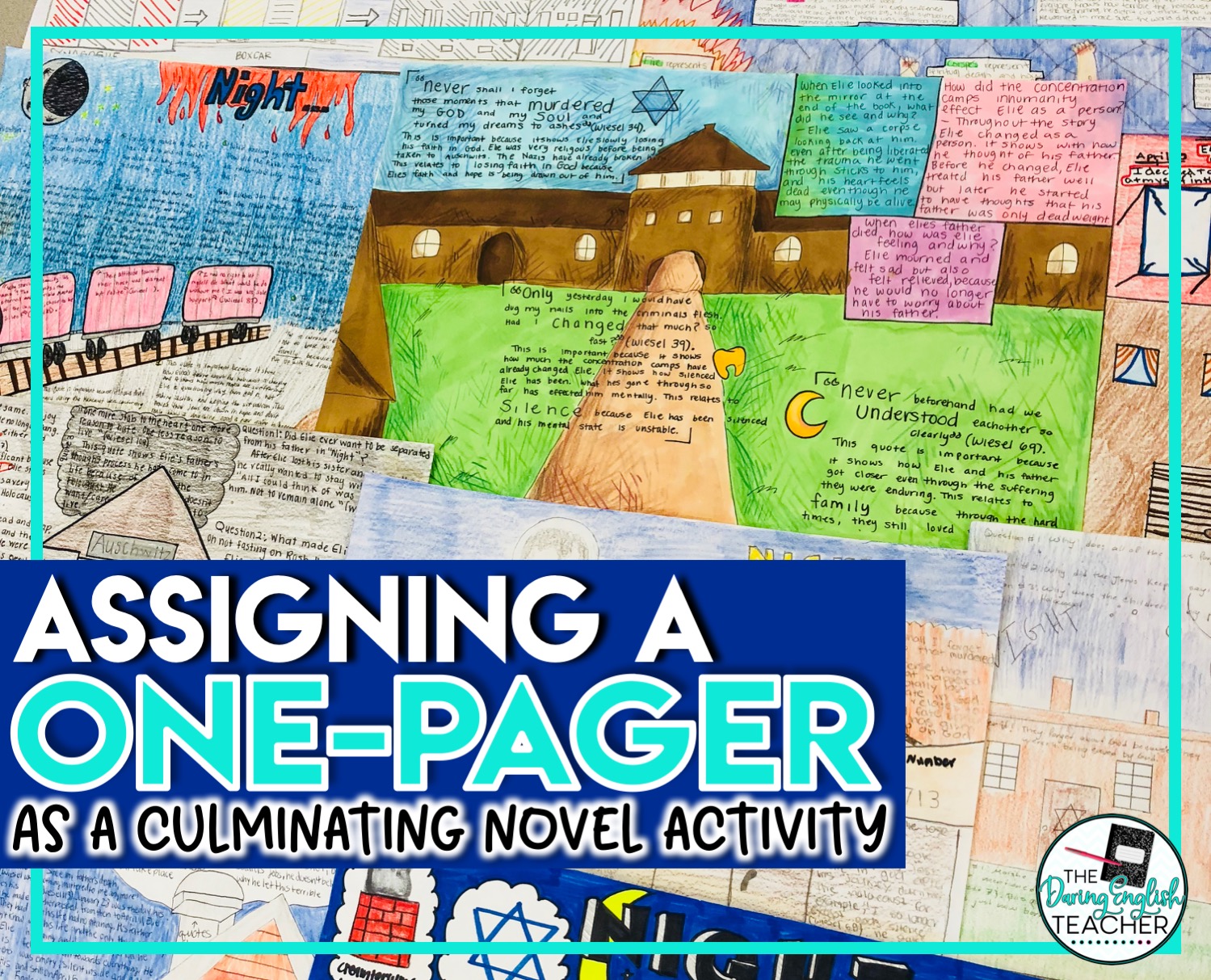

A Simple Trick for Success with One-Pagers

May 26, 2019

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

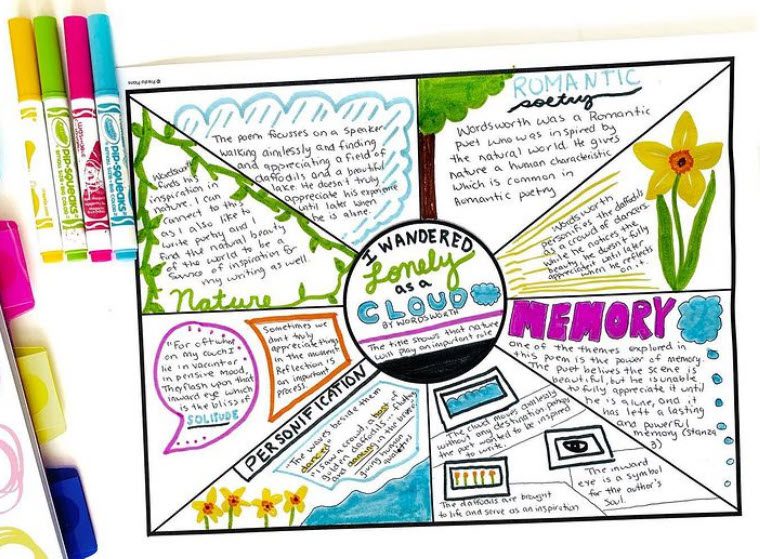

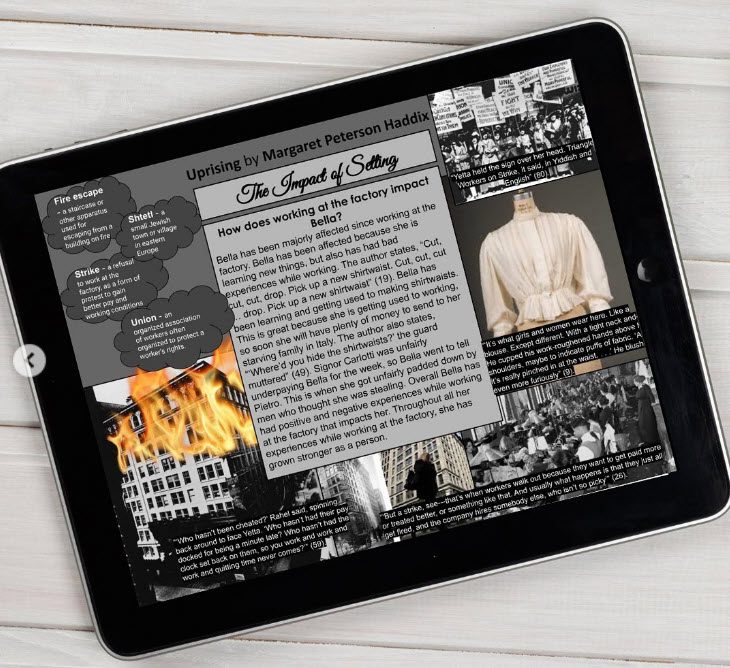

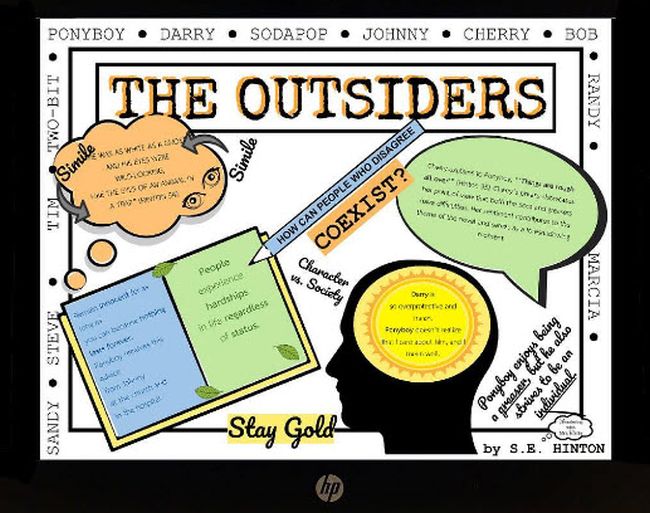

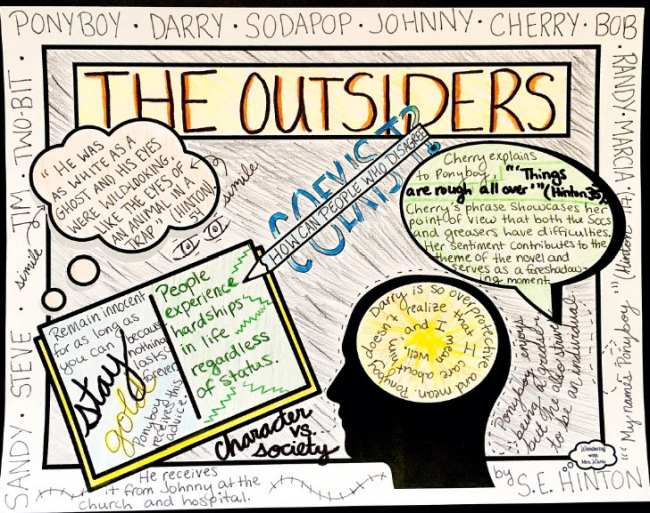

Listen to my interview with Betsy Potash ( transcript ):

Sponsored by Chill Expeditions and Kiddom

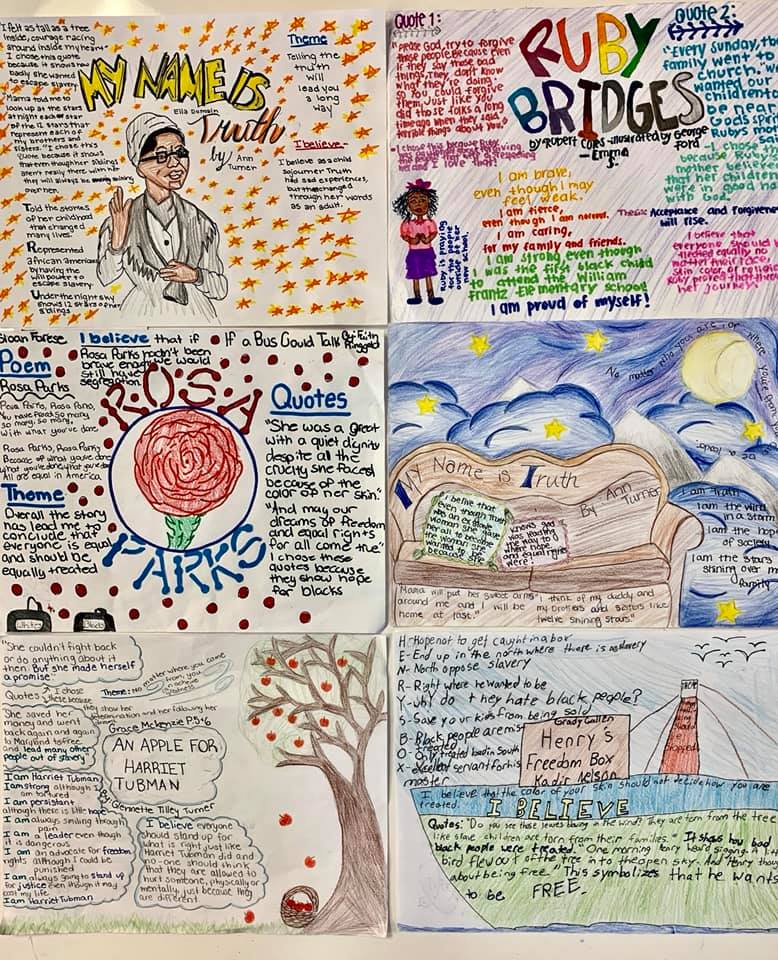

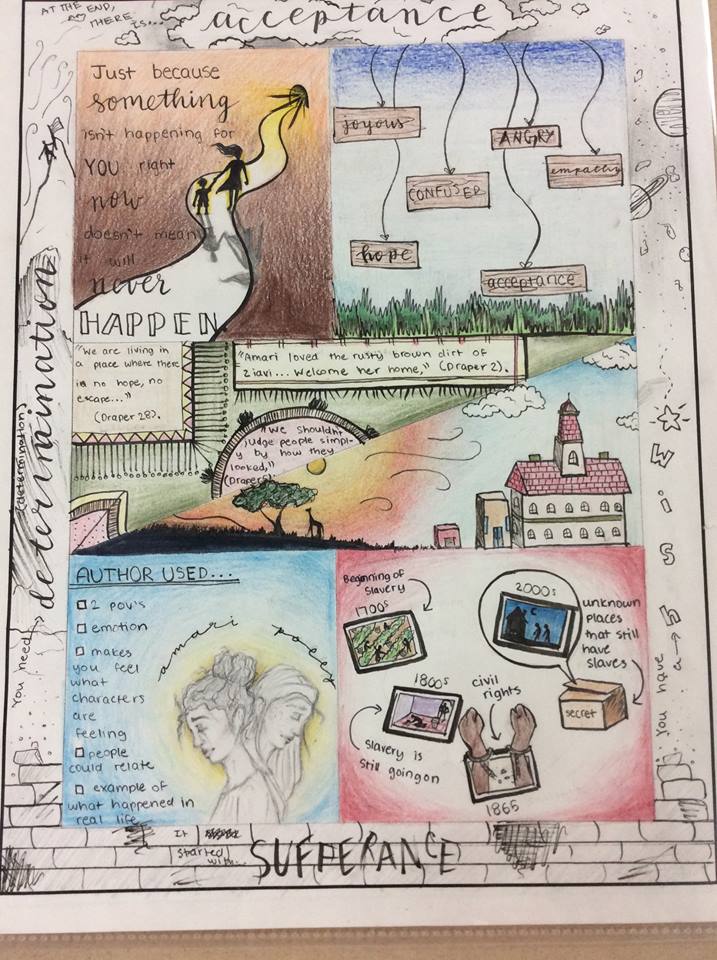

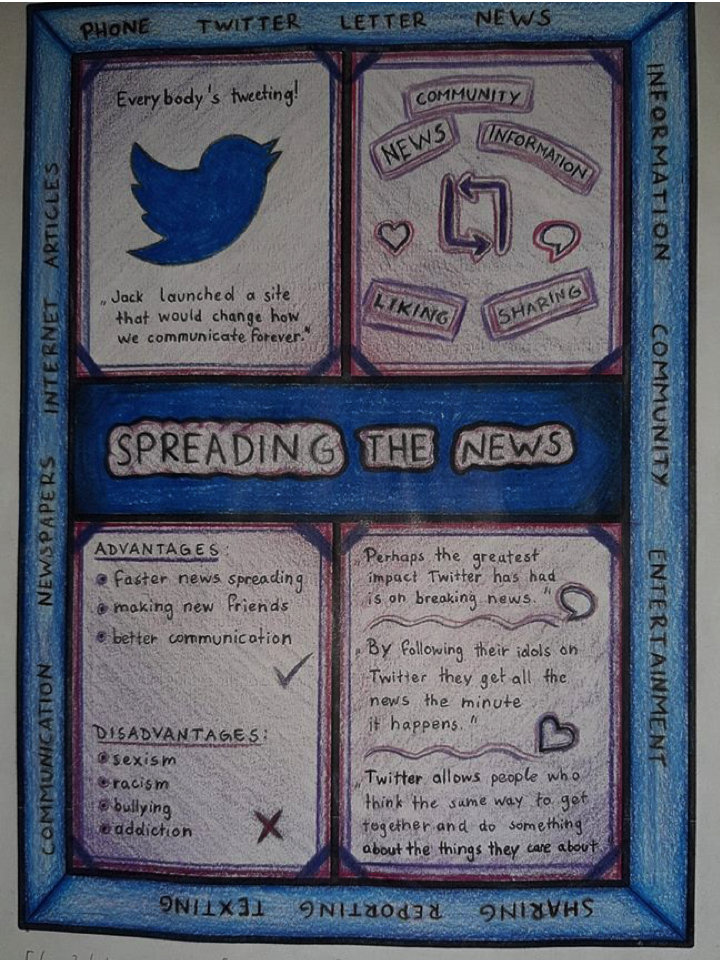

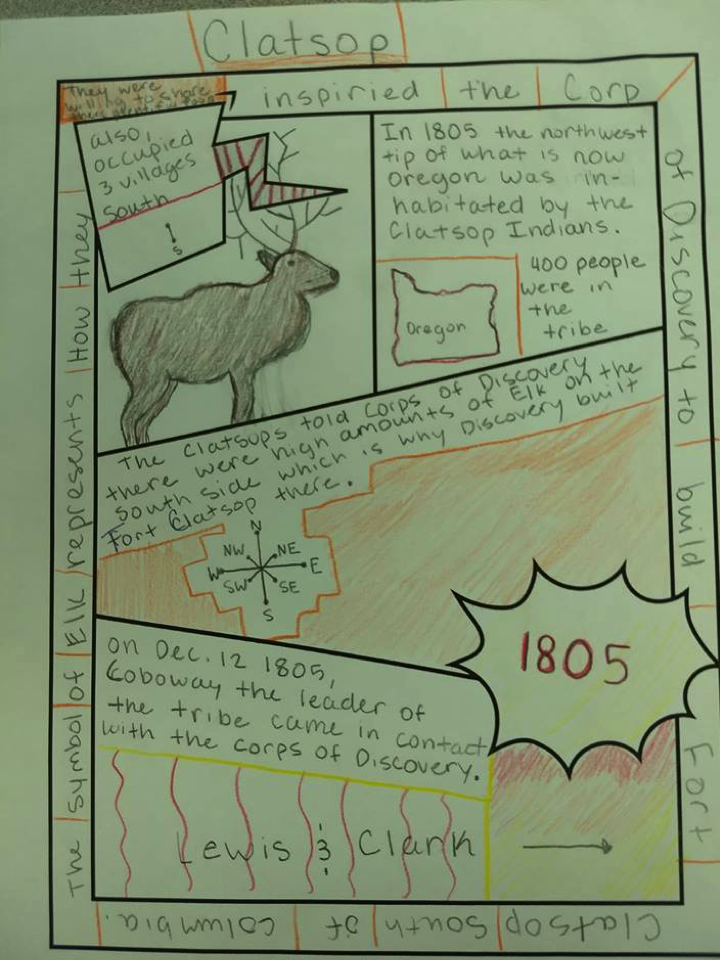

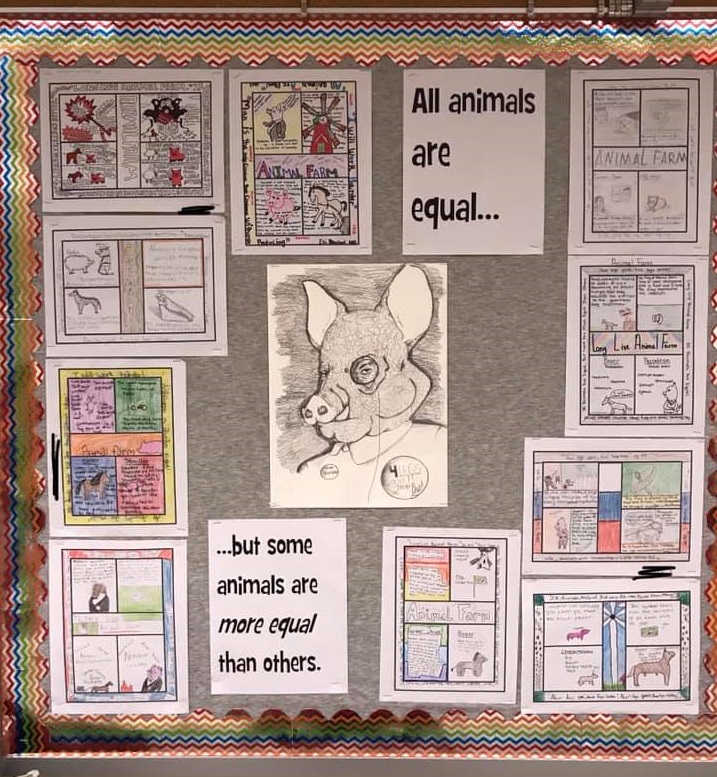

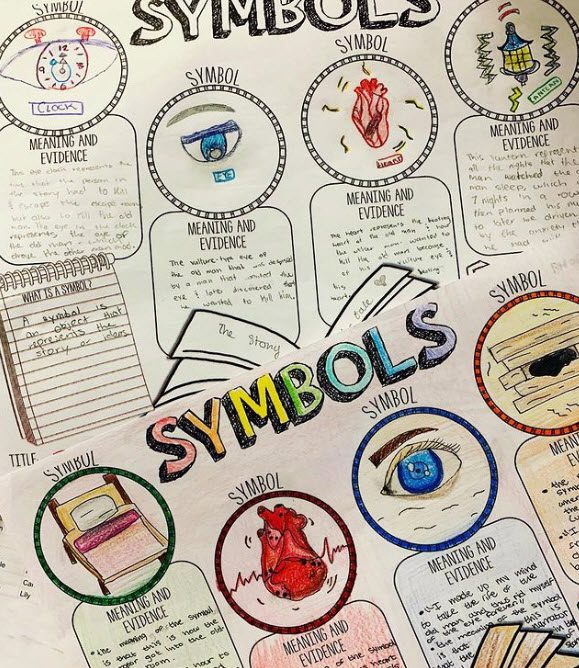

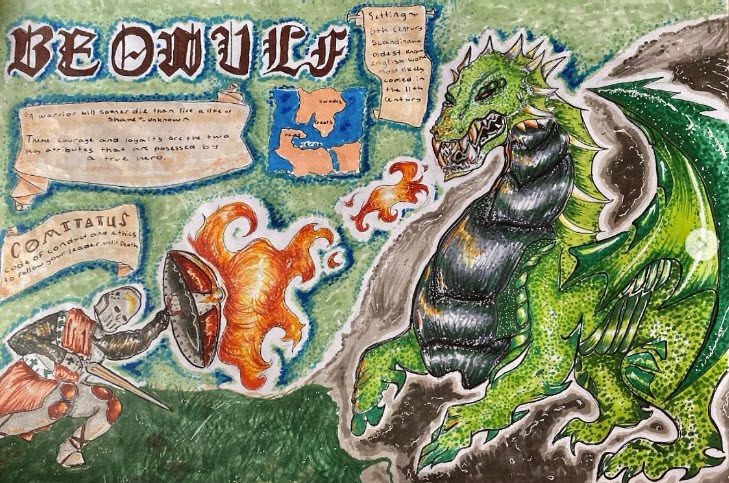

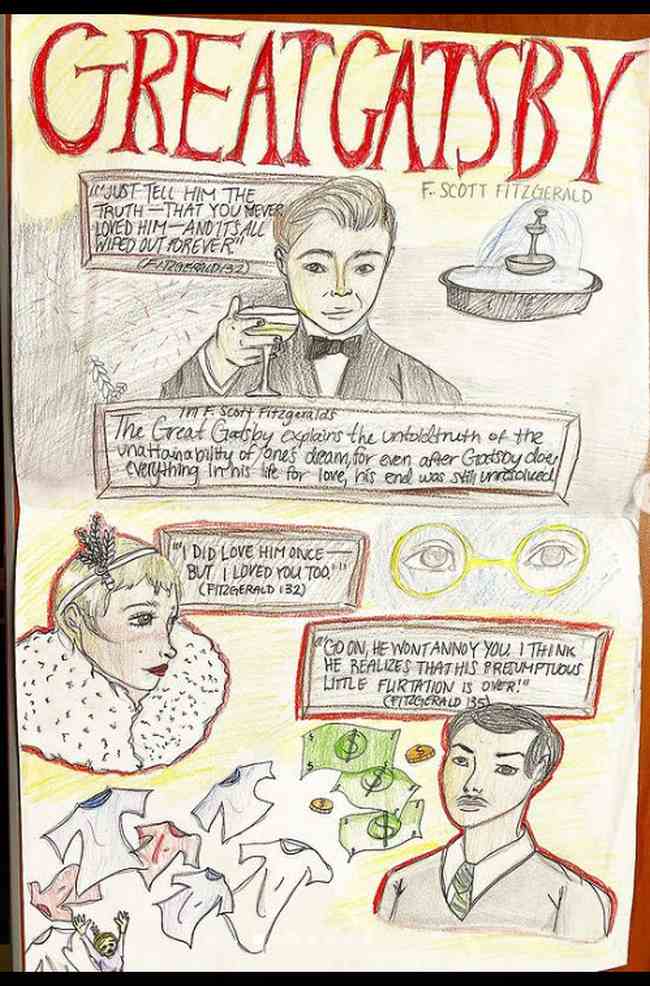

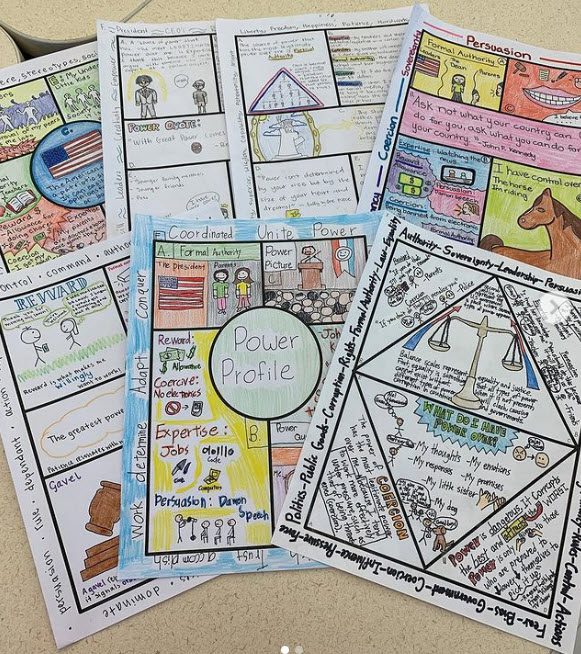

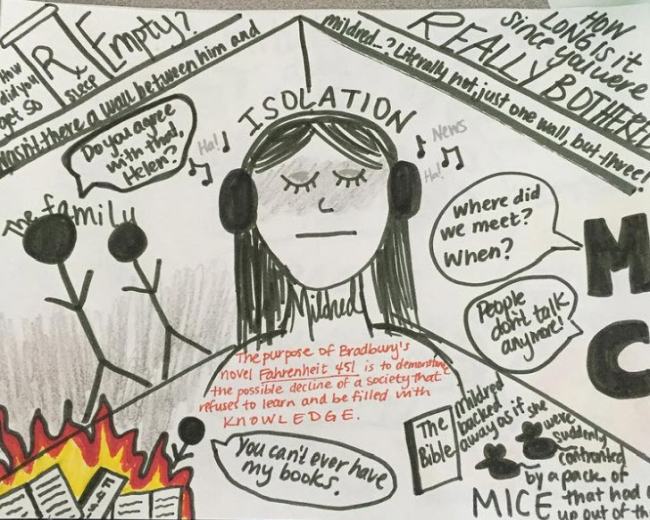

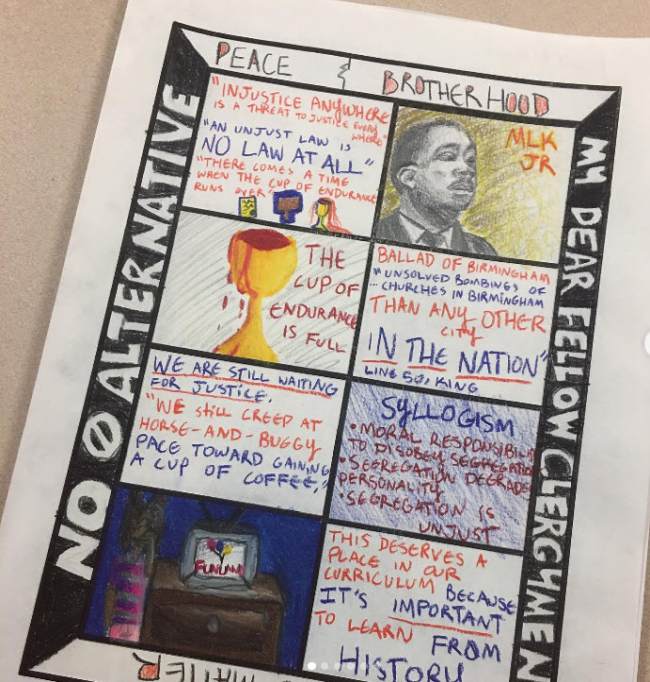

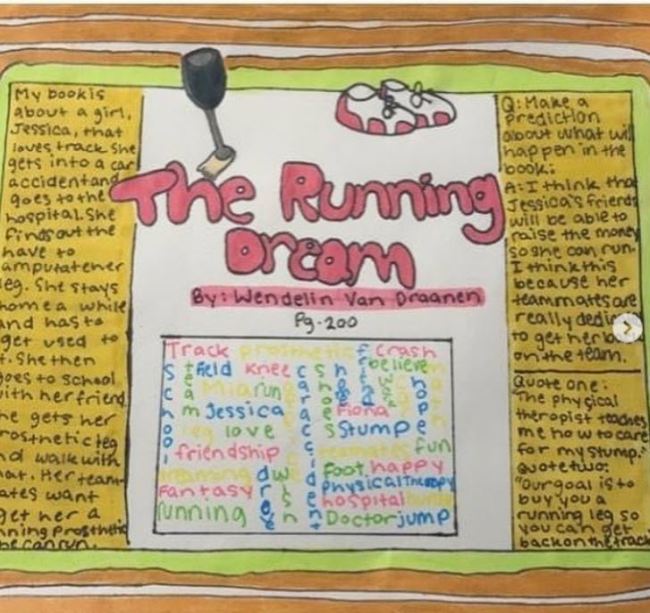

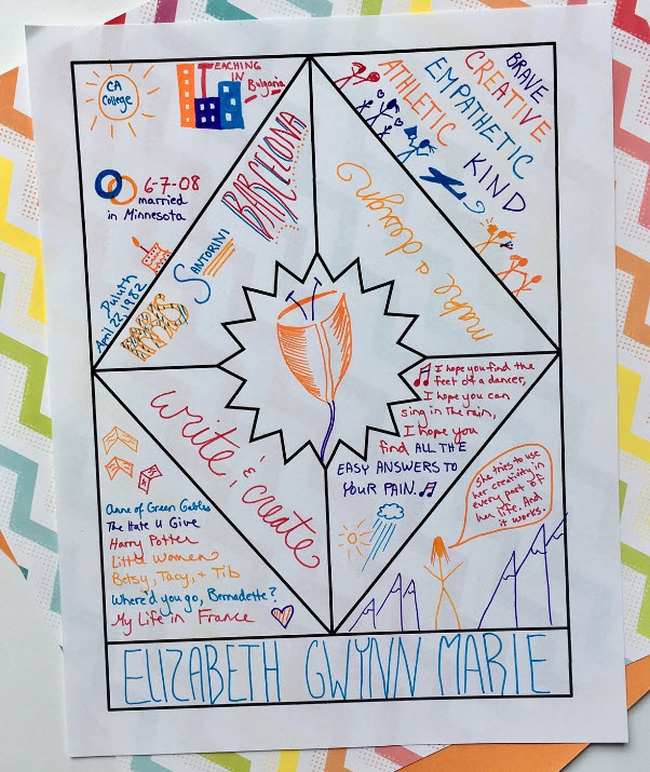

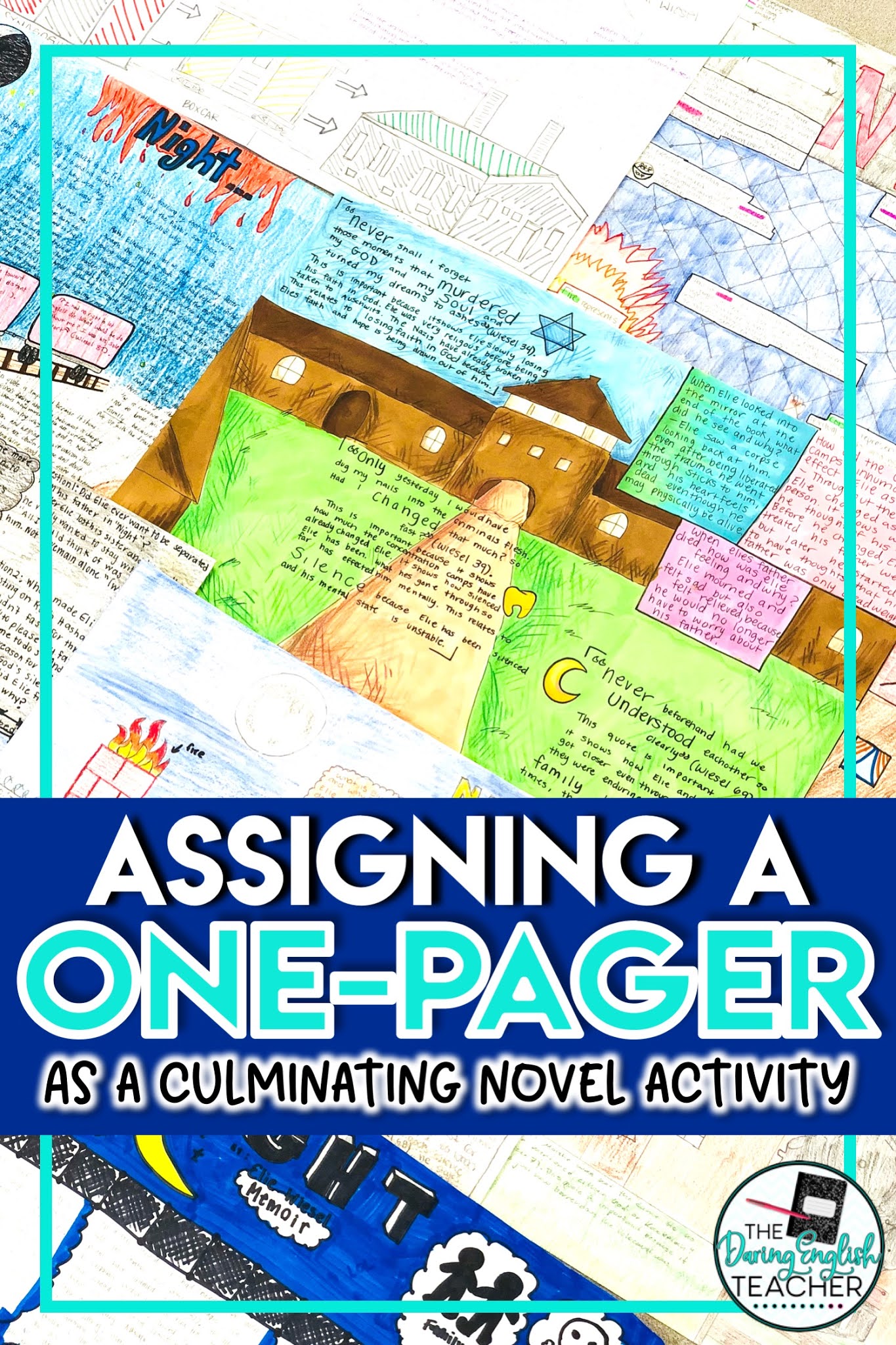

Have you heard the whispers about one-pagers in the online teacher hallways? The concept of a one-pager, in which students share their most important takeaways on a single piece of blank paper, has really taken off recently.

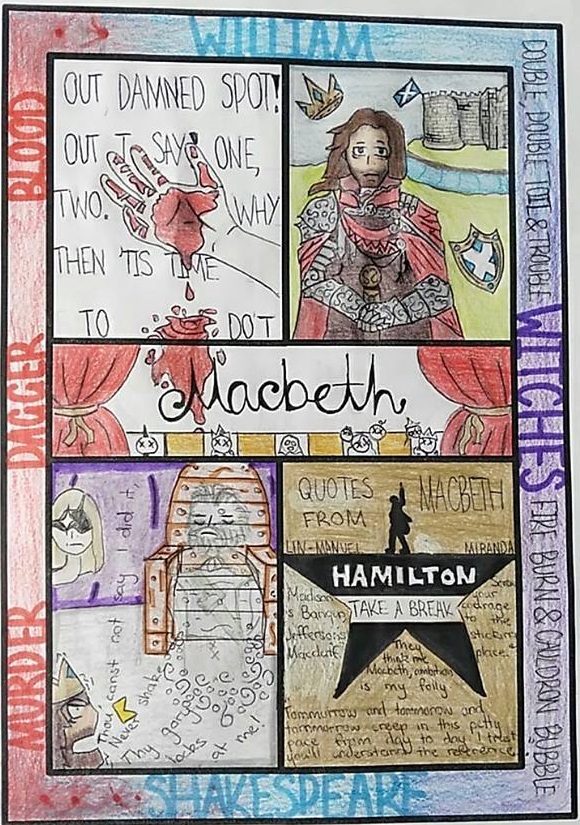

The one-pagers I see on Instagram draw me in like a slice of double chocolate mousse cake. The artistry students bring to representing their texts on a single piece of paper, blending images and ideas in creative color, is almost hypnotizing for me. Perhaps you’ve had the same experience.

But it’s the very beauty of the models that get posted that can drive students and teachers away from the one-pager activity. Sure, it’s great for super artistic students , we tend to think, but what about everyone else?

Turns out it CAN be great for everyone. As long as you know how to structure it.

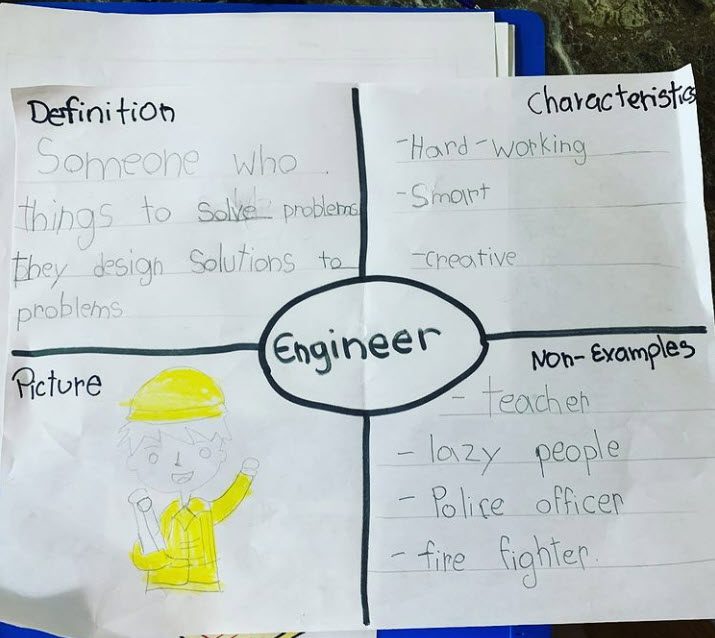

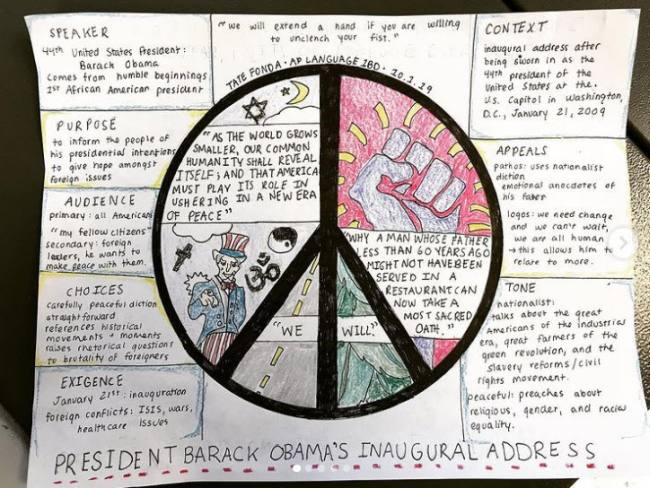

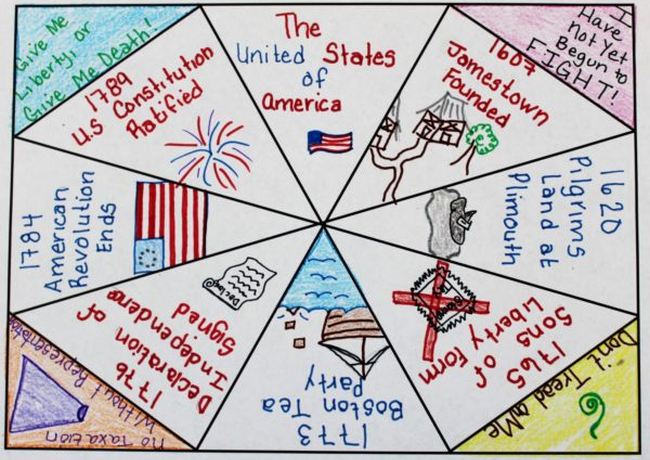

What Is a One-Pager?

Let’s backtrack a bit and talk more about what a one-pager is. It’s pretty simple, really. Students take what they’ve learned—from a history textbook, a novel, a poem, a podcast, a Ted Talk, a guest speaker, a film—and put the highlights onto a single piece of paper. AVID first developed this strategy, but now it’s widely used in and out of AVID classrooms.

But why is this seemingly simple assignment so powerful?

As students create one-pagers, the information they put down becomes more memorable to them as they mix images and information. According to Allan Paivio’s dual coding theory, the brain has two ways of processing: the visual and the verbal. The combination of the two leads to the most powerful results. Students will remember more when they’ve mixed language and imagery.

Plus, one-pagers provide variety, a way for them to share what they’ve learned that goes beyond the usual written options. Students tend to surprise themselves with what they come up with, and their work makes for powerful displays of learning. Plus, they’re fun to make. Let’s not pretend that doesn’t matter.

So, assuming you’re sold on trying this out, you’re probably wondering what exactly goes into a one-pager?

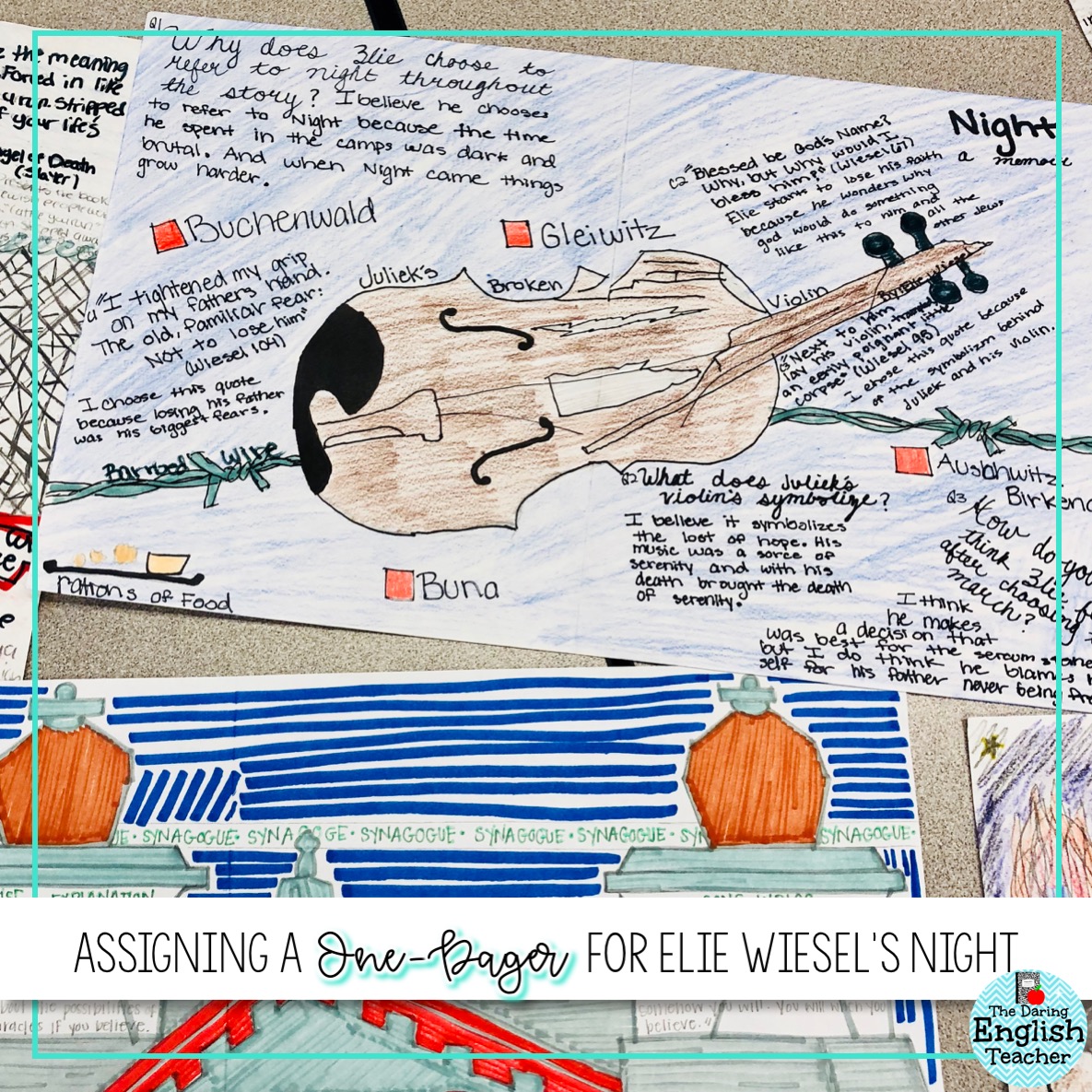

Students might include quotations, ideas, images, analysis, key names and dates, and more. They might use their one-pagers to make connections to their own lives, to art or films, to pop culture, to what they’re learning in their other classes. They might even do it all. You’d be amazed at how much can fit on a single piece of paper.

Many teachers create lists of what students should put inside their one-pagers. Knowing they need two quotations, several symbolic images, one key theme, etc., helps guide students in their work.

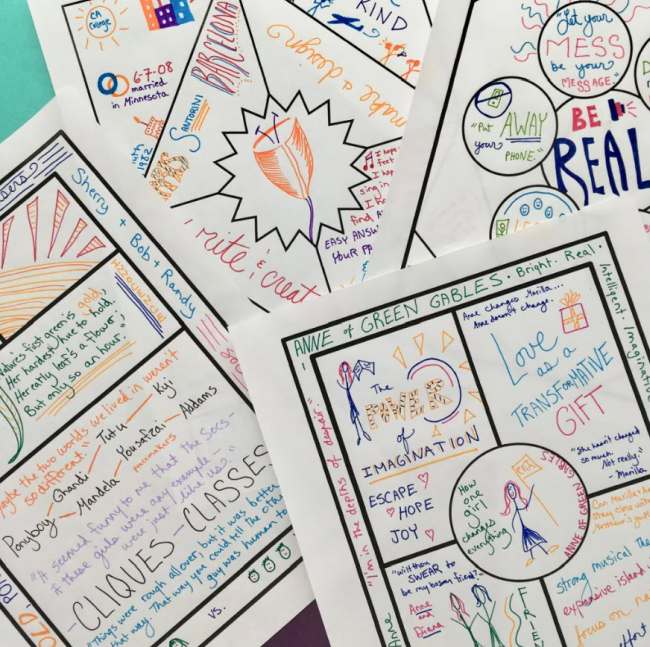

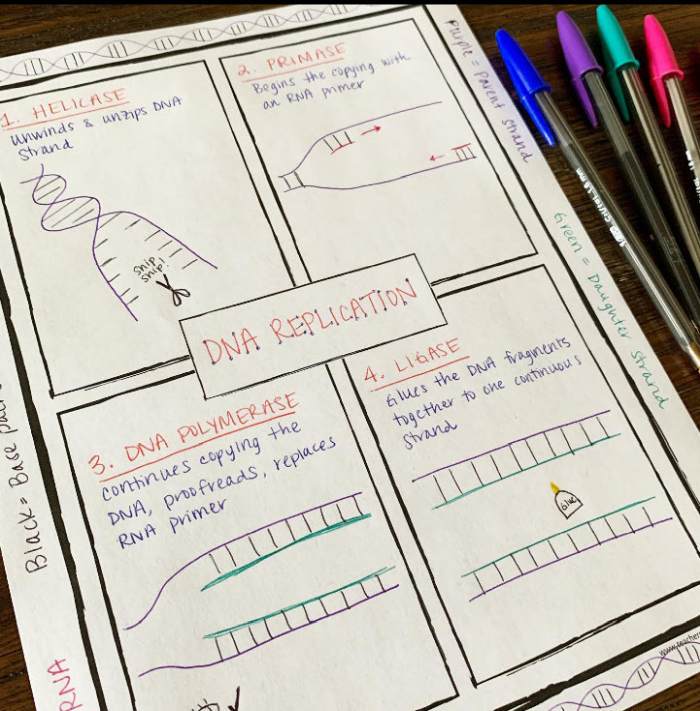

The Art Problem

When creating one-pagers, artistic students tend to feature more sketches, doodles, icons and lettering. Students wary of art tend to feature more text, and can be reluctant to engage with the visual part of the assignment at all.

It was this issue—the issue of the art-haters—that first drew me into one-pagers two years ago. I had seen some stunning one-pagers posted in my Facebook group, Creative High School English . But the comments that followed were always the same. “That’s amazing work! But so many of my students don’t like art….”

Those comments struck a chord with me. For years I had dealt with comments from some of my own students about their distaste for artistic materials when I would introduce creative projects. No matter how much I explained that it was the intention behind their choices that mattered, I always got some pushback if there were any artistic elements involved in a project.

Was there a way to tweak the one-pager assignment so every student would feel confident in their success?

Another problem was one of overall design: Though they knew they needed to hit all the requirements their teachers listed, students still seemed to be overwhelmed by that huge blank page. What should go where? Did colored pencils really have to be involved?

A Simple Solution: Templates

As I thought about the problem, I wondered if students would feel less overwhelmed if they knew what needed to go where. If the quotations had to be in the middle, the themes in the upper left, the images across the bottom, etc. I began to play around with the shapes tool in PowerPoint, creating different one-pager templates.

Then I began shaping my requirements, correlating each element with a space on the paper. Maybe the border could be the key quotations. The center would feature an important symbol. The themes could go in circles around the center. I developed a bunch of different templates for varied ways to respond to novels. Then I tried podcasts. Films. Poetry.

As I shared these templates with other teachers, I kept getting the same feedback: “It’s working!”

That little bit of creative constraint actually frees students to use their imagination to represent what they have learned on the page without fear. They know what they need to put down, and where, but they are also free to expand and add to the template. To choose their own colors. To bring out what is most important to them through their creativity and artistry. And those super artistic students? They can just flip the template over and use the blank page on the back.

Beyond Novels