Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

Published on March 10, 2023 by Tegan George .

Participant observation is a research method where the researcher immerses themself in a particular social setting or group, observing the behaviors, interactions, and practices of the participants. This can be a valuable method for any research project that seeks to understand the experiences of individuals or groups in a particular social context.

In participant observation, the researcher is called a participant-observer , meaning that they participate in the group’s activities while also observing the group’s behavior and interactions. There is flexibility in the level of participation, ranging from non-participatory (the weakest) to complete participation (the strongest but most intensive.) The goal here is to gain a deep understanding of the group’s culture, beliefs, and practices from an “insider” perspective.

You immerse yourself in this subculture by spending time at skateparks, attending skateboarding events, and engaging with skateboarders. Perhaps you may even learn to skateboard yourself, in order to better understand the experiences of your study participants.

As you observe, you take notes on the behavior, language, norms, and values you witness and also conduct informal unstructured interviews with individual skateboarders to gain further insight into their thoughts and lived experiences.

Typically used in fields like anthropology, sociology, and other social sciences, this method is often used to gather rich and detailed data about social groups or phenomena through ethnographies or other qualitative research .

Table of contents

When to use participant observation, examples of participant observation, how to analyze data from participant observation, advantages and disadvantages of participant observations, other types of research bias, frequently asked questions.

Participant observation is a type of observational study . Like most observational studies, these are primarily qualitative in nature, used to conduct both explanatory research and exploratory research . Participant observation is also often used in conjunction with other types of research, like interviews and surveys .

This type of study is especially well suited for studying social phenomena that are difficult to observe or measure through other methods. As the researcher observes, they typically take detailed notes about their observations and interactions with the group. These are then analyzed to identify patterns and themes using thematic analysis or a similar method.

A participant observation could be a good fit for your research if:

- You are studying subcultures or groups with unique practices or beliefs. Participant observation fosters a deep and intimate understanding of the beliefs, values, and practices of your group or subculture of interest from an insider’s perspective. This can be especially useful when studying marginalized groups or groups that are resistant to observation.

- You are studying complex social interactions . Participant observation can be a powerful tool for studying the complex social interactions that occur within a particular group or community. By immersing yourself in the group and observing these interactions firsthand, you can gain a much more nuanced understanding of how these interactions flow.

- You are studying behaviors or practices that may be difficult to self-report . In some cases, participants may be unwilling or unable to accurately report their own behaviors or practices. Participant observation allows researchers to observe these behaviors directly, allowing for more accuracy in the data collection phase.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Participant observation is a common research method in social sciences, with findings often published in research reports used to inform policymakers or other stakeholders.

Over the course of several months, you observe and take notes on the social interactions, customs, and beliefs of the community members, conducting informal interviews with individual residents to gain further insight into their experiences and perspectives. Through your observations, you gain a deep understanding of the community’s culture, including its values, traditions, and social hierarchy.

Participant observations are often also used in sociology to study social groups and related phenomena, like group formation, stratification, or conflict resolution.

Through this participant observation, you soon see that the group is highly stratified, with certain individuals occupying positions of social power and others being marginalized or even largely excluded. You also observe patterns of conformity within the group, alongside complex interpersonal dynamics.

Data analysis in participant observation typically involves a step-by-step process of immersion, categorization, and interpretation.

- After finishing up your observations, you read through your field notes or transcripts multiple times in the immersion phase. This helps you reflect on what you studied, and is well paired with conducting data cleansing to ensure everything is clear and correct prior to proceeding.

- You then create categories or themes to organize the data. This helps with identifying patterns, behaviors, and interactions relevant to your research question or study aims. In turn, these categories help you to form a coding system that labels or “tags” the aspects of the data that you want to focus on. These can be specific behaviors, emotions, or social interactions—whatever helps you to identify connections between different elements of your data.

- Next, your data can be analyzed using a variety of qualitative research methods, such as thematic analysis , grounded theory, or discourse analysis using the coded categories you created. This helps you interpret the data and develop further theories. You may also want to use triangulation , comparing data from multiple sources or methods, to bolster the reliability and validity of your findings.

- Lastly, it’s always a good research practice to seek feedback on your findings from other researchers in your field of study, as well as members of the group you studied. This helps to ensure the accuracy and reliability of your analysis and can mitigate some potential research biases .

Participant observations are a strong fit for some research projects, but with their advantages come their share of disadvantages as well.

Advantages of participant observations

- Participant observations allow you to generate rich and nuanced qualitative data —particularly useful when seeking to develop a deep understanding of a particular social context or experience. By immersing yourself in the group, you can gain an unrivaled insider perspective on the group’s beliefs, values, and practices.

- Participant observation is a flexible research method that can be adapted to fit a variety of research questions and contexts. Metrics like level of participation in the group, the length of the observation period, and the types of data collected all can be adjusted based on research goals and timeline.

- Participant observation is often used in combination with other research methods, such as interviews or surveys , to provide a more complete picture of the phenomenon being studied. This triangulation can help to improve the reliability and validity of the research findings, as participant observations are not particularly strong as a standalone method.

Disadvantages of participant observations

- Like many observational studies, participant observations are at high risk for many research biases , particularly on the side of the researcher. Because participant observation involves the researcher immersing themselves in the group being studied, there is a risk that their own biases could influence the data they collect, leading to observer bias . Likewise, the presence of a researcher in the group being studied can potentially influence the behavior of the participants. This can lead to inaccurate or biased data if participants alter their behavior in response to the researcher’s presence, leading to a Hawthorne effect or social desirability bias .

- Participant observations can be very expensive, time-consuming, and challenging to carry out. They often require a long period of time to build trust and gather sufficient data, with the data usually collected in an intensive, in-person manner. Some participant observations take generations to complete, which can make it difficult to conduct studies with limited time or resources.

- Participant observation can raise ethical concerns , requiring measured ethical consideration on the part of the researcher with regard to informed consent, privacy, and confidentiality. The researcher must take care to protect the privacy and autonomy of the participants and ensure that they are not placed at undue risk by the research.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

- Confirmation bias

- Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Ingroup bias

- Outgroup bias

- Perception bias

- Framing effect

- Self-serving bias

- Affect heuristic

- Representativeness heuristic

- Anchoring heuristic

- Primacy bias

- Optimism bias

- Sampling bias

- Ascertainment bias

- Attrition bias

- Self-selection bias

- Survivorship bias

- Nonresponse bias

- Undercoverage bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Observer bias

- Omitted variable bias

- Publication bias

- Conformity bias

- Pygmalion effect

- Recall bias

- Social desirability bias

- Placebo effect

- Actor-observer bias

- Ceiling effect

- Ecological fallacy

- Affinity bias

Ethical considerations in participant observation involve:

- Obtaining informed consent from all participants

- Protecting their privacy and confidentiality

- Ensuring that they are not placed at undue risk by the research, and

- Respecting their autonomy and agency as participants

Researchers should also consider the potential impact of their research on the community being studied and take steps to minimize any negative after-effects.

Participant observation is a type of qualitative research method . It involves active participation on the part of the researcher in the group being studied, usually over a longer period of time.

Other qualitative research methods, such as interviews or focus groups , do not involve the same level of immersion in the research and can be conducted in a less intense manner.

In participant observation , the researcher plays an active role in the social phenomenon, group, or social context being studied. They may move into the community, attend events or activities, or even take on specific roles within the group— fully joining the community over the course of the study. However, the researcher also maintains an observer role here, taking notes on the behavior and interactions of the participants to draw conclusions and guide further research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, March 10). What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/participant-observation/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, what is an observational study | guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Chapter 13. Participant Observation

Introduction.

Although there are many possible forms of data collection in the qualitative researcher’s toolkit, the two predominant forms are interviewing and observing. This chapter and the following chapter explore observational data collection. While most observers also include interviewing, many interviewers do not also include observation. It takes some special skills and a certain confidence to be a successful observer. There is also a rich tradition of what I am going to call “deep ethnography” that will be covered in chapter 14. In this chapter, we tackle the basics of observational data collection.

What is Participant Observation?

While interviewing helps us understand how people make sense of their worlds, observing them helps us understand how they act and behave. Sometimes, these actions and behaviors belie what people think or say about their beliefs and values and practices. For example, a person can tell you they would never racially discriminate, but observing how they actually interact with racialized others might undercut those statements. This is not always about dishonesty. Most of us tend to act differently than we think we do or think we should. That is part of being human. If you are interested in what people say and believe , interviewing is a useful technique for data collection. If you are interested in how people act and behave , observing them is essential. And if you want to know both, particularly how thinking/believing and acting/behaving complement or contradict each other, then a combination of interviewing and observing is ideal.

There are a variety of terms we use for observational data collection, from ethnography to fieldwork to participant observation . Many researchers use these terms fairly interchangeably, but here I will separately define them. The subject of this chapter is observation in general, or participant observation, to highlight the fact that observers can also be participants. The subject of chapter 14 will be deep ethnography , a particularly immersive form of study that is attractive for a certain subset of qualitative researchers. Both participant observation and deep ethnography are forms of fieldwork in which the researcher leaves their office and goes into a natural setting to record observations that take place in that setting. [1]

Participant observation (PO) is a field approach to gathering data in which the researcher enters a specific site for purposes of engagement or observation. Participation and observation can be conceptualized as a continuum, and any given study can fall somewhere on that line between full participation (researcher is a member of the community or organization being studied) and observation (researcher pretends to be a fly on the wall surreptitiously but mostly by permission, recording what happens). Participant observation forms the heart of ethnographic research, an approach, if you remember, that seeks to understand and write about a particular culture or subculture. We’ll discuss what I am calling deep ethnography in the next chapter, where researchers often embed themselves for months if not years or even decades with a particular group to be able to fully capture “what it’s like.” But there are lighter versions of PO that can form the basis of a research study or that can supplement or work with other forms of data collection, such as interviews or archival research. This chapter will focus on these lighter versions, although note that much of what is said here can also apply to deep ethnography (chapter 14).

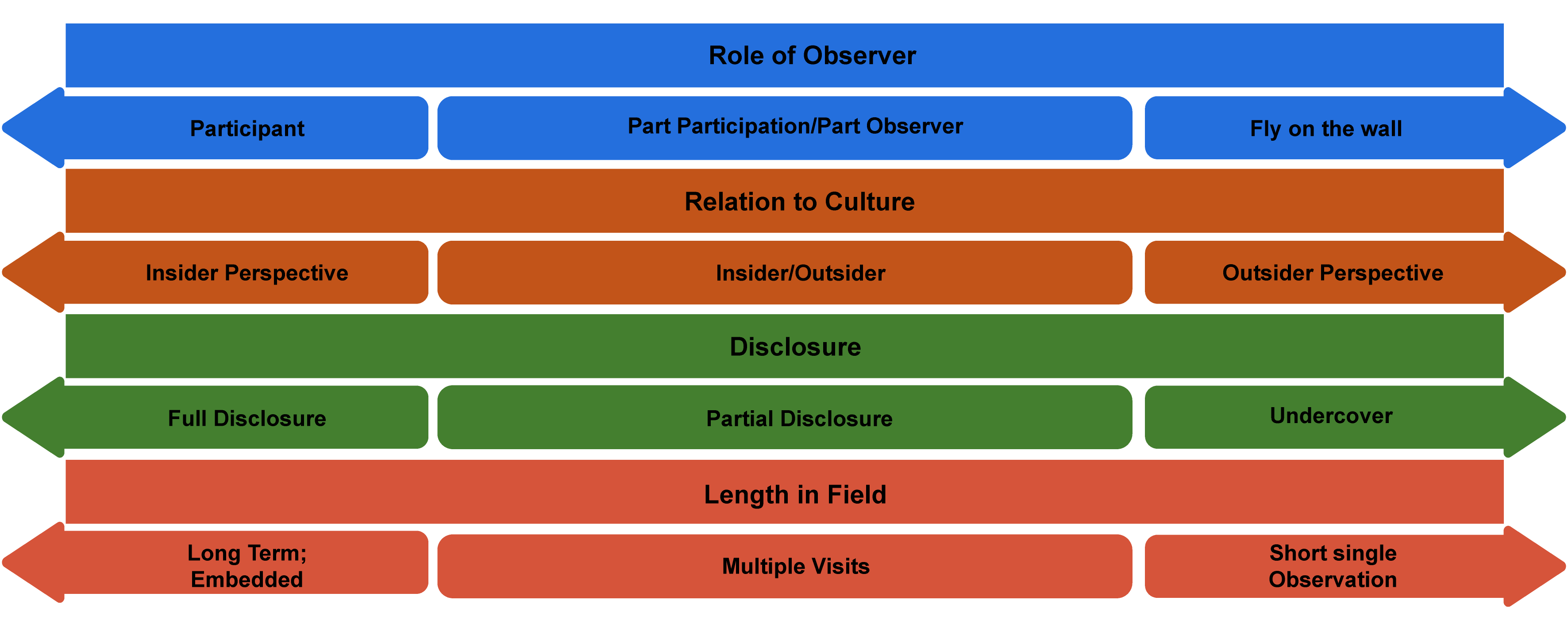

PO methods of gathering data present some special considerations—How involved is the researcher? How close is she to the subjects or site being studied? And how might her own social location—identity, position—affect the study? These are actually great questions for any kind of qualitative data collection but particularly apt when the researcher “enters the field,” so to speak. It is helpful to visualize where one falls on a continuum or series of continua (figure 13.1).

Let’s take a few examples and see how these continua work. Think about each of the following scenarios, and map them onto the possibilities of figure 13.1:

- a nursing student during COVID doing research on patient/doctor interactions in the ICU

- a graduate student accompanying a police officer during her rounds one day in a part of the city the graduate student has never visited

- a professor raised Amish who goes back to her hometown to conduct research on Amish marriage practices for one month

- (What if the sociologist was also a member of the OCF board and camping crew?)

Depending on how the researcher answers those questions and where they stand on the P.O. continuum, various techniques will be more or less effective. For example, in cases where the researcher is a participant, writing reflective fieldnotes at the end of the day may be the primary form of data collected. After all, if the researcher is fully participating, they probably don’t have the time or ability to pull out a notepad and ask people questions. On the other side, when a researcher is more of an observer, this is exactly what they might do, so long as the people they are interrogating are able to answer while they are going about their business. The more an observer, the more likely the researcher will engage in relatively structured interviews (using techniques discussed in chapters 11 and 12); the more a participant, the more likely casual conversations or “unstructured interviews” will form the core of the data collected. [2]

Observation and Qualitative Traditions

Observational techniques are used whenever the researcher wants to document actual behaviors and practices as they happen (not as they are explained or recorded historically). Many traditions of inquiry employ observational data collection, but not all traditions employ them in the same way. Chapter 14 will cover one very specific tradition: ethnography. Because the word ethnography is sometimes used for all fieldwork, I am calling the subject of chapter 14 deep ethnography, those studies that take as their focus the documentation through the description of a culture or subculture. Deeply immersive, this tradition of ethnography typically entails several months or even years in the field. But there are plenty of other uses of observation that are less burdensome to the researcher.

Grounded Theory, in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction, is amenable to both interviewing and observing forms of data collection, and some of the best Grounded Theory works employ a deft combination of both. Often closely aligned with Grounded Theory in sociology is the tradition of symbolic interactionism (SI). Interviews and observations in combination are necessary to properly address the SI question, What common understandings give meaning to people’s interactions ? Gary Alan Fine’s body of work fruitfully combines interviews and observations to build theory in response to this SI question. His Authors of the Storm: Meteorologists and the Culture of Prediction is based on field observation and interviews at the Storm Prediction Center in Oklahoma; the National Weather Service in Washington, DC; and a few regional weather forecasting outlets in the Midwest. Using what he heard and what he observed, he builds a theory of weather forecasting based on social and cultural factors that take place inside local offices. In Morel Tales: The Culture of Mushrooming , Fine investigates the world of mushroom hunters through participant observation and interviews, eventually building a theory of “naturework” to describe how the meanings people hold about the world are constructed and are socially organized—our understanding of “nature” is based on human nature, if you will.

Phenomenology typically foregrounds interviewing, as the purpose of this tradition is to gather people’s understandings and meanings about a phenomenon. However, it is quite common for phenomenological interviewing to be supplemented with some observational data, especially as a check on the “reality” of the situations being described by those interviewed. In my own work, for example, I supplemented primary interviews with working-class college students with some participant observational work on the campus in which they were studying. This helped me gather information on the general silence about class on campus, which made the salience of class in the interviews even more striking ( Hurst 2010a ).

Critical theories such as standpoint approaches, feminist theory, and Critical Race Theory are often multimethod in design. Interviews, observations (possibly participation), and archival/historical data are all employed to gather an understanding of how a group of persons experiences a particular setting or institution or phenomenon and how things can be made more just . In Making Elite Lawyers , Robert Granfield ( 1992 ) drew on both classroom observations and in-depth interviews with students to document the conservatizing effects of the Harvard legal education on working-class students, female students, and students of color. In this case, stories recounted by students were amplified by searing examples of discrimination and bias observed by Granfield and reported in full detail through his fieldnotes.

Entry Access and Issues

Managing your entry into a field site is one of the most important and nerve-wracking aspects of doing ethnographic research. Unlike interviews, which can be conducted in neutral settings, the field is an actual place with its own rules and customs that you are seeking to explore. How you “gain access” will depend on what kind of field you are entering. If your field site is a physical location with walls and a front desk (such as an office building or an elementary school), you will need permission from someone in the organization to enter and to conduct your study. Negotiating this might take weeks or even months. If your field site is a public site (such as a public dog park or city sidewalks), there is no “official” gatekeeper, but you will still probably need to find a person present at the site who can vouch for you (e.g., other dog owners or people hanging out on their stoops). [3] And if your field site is semipublic, as in a shopping mall, you might have to weigh the pros and cons of gaining “official” permission, as this might impede your progress or be difficult to ascertain whose permission to request. If you recall, many of the ethical dilemmas discussed in chapter 7 were about just such issues.

Even with official (or unofficial) permission to enter the site, however, your quest to gain access is not done. You will still need to gain the trust and permission of the people you encounter at that site. If you are a mere observer in a public setting, you probably do not need each person you observe to sign a consent form, but if you are a participant in an event or enterprise who is also taking notes and asking people questions, you probably do. Each study is unique here, so I recommend talking through the ethics of permission and consent seeking with a faculty mentor.

A separate but related issue from permission is how you will introduce yourself and your presence. How you introduce yourself to people in the field will depend very much on what level of participation you have chosen as well as whether you are an insider or outsider. Sometimes your presence will go unremarked, whereas other times you may stick out like a very sore thumb. Lareau ( 2021 ) advises that you be “vague but accurate” when explaining your presence. You don’t want to use academic jargon (unless your field is the academy!) that would be off-putting to the people you meet. Nor do you want to deceive anyone. “Hi, I’m Allison, and I am here to observe how students use career services” is accurate and simple and more effective than “I am here to study how race, class, and gender affect college students’ interactions with career services personnel.”

Researcher Note

Something that surprised me and that I still think about a lot is how to explain to respondents what I’m doing and why and how to help them feel comfortable with field work. When I was planning fieldwork for my dissertation, I was thinking of it from a researcher’s perspective and not from a respondent’s perspective. It wasn’t until I got into the field that I started to realize what a strange thing I was planning to spend my time on and asking others to allow me to do. Like, can I follow you around and write notes? This varied a bit by site—it was easier to ask to sit in on meetings, for example—but asking people to let me spend a lot of time with them was awkward for me and for them. I ended up asking if I could shadow them, a verb that seemed to make clear what I hoped to be able to do. But even this didn’t get around issues like respondents’ self-consciousness or my own. For example, respondents sometimes told me that their lives were “boring” and that they felt embarrassed to have someone else shadow them when they weren’t “doing anything.” Similarly, I would feel uncomfortable in social settings where I knew only one person. Taking field notes is not something to do at a party, and when introduced as a researcher, people would sometimes ask, “So are you researching me right now?” The answer to that is always yes. I figured out ways of taking notes that worked (I often sent myself text messages with jotted notes) and how to get more comfortable explaining what I wanted to be able to do (wanting to see the campus from the respondent’s perspective, for example), but it is still something I work to improve.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life and coauthor of Geographies of Campus Inequality

Reflexivity in Fieldwork

As always, being aware of who you are, how you are likely to be read by others in the field, and how your own experiences and understandings of the world are likely to affect your reading of others in the field are all very important to conducting successful research. When Annette Lareau ( 2021 ) was managing a team of graduate student researchers in her study of parents and children, she noticed that her middle-class graduate students took in stride the fact that children called adults by their first names, while her working-class-origin graduate students “were shocked by what they considered the rudeness and disrespect middle-class children showed toward their parents and other adults” ( 151 ). This “finding” emerged from particular fieldnotes taken by particular research assistants. Having graduate students with different class backgrounds turned out to be useful. Being reflexive in this case meant interrogating one’s own expectations about how children should act toward adults. Creating thick descriptions in the fieldnotes (e.g., describing how children name adults) is important, but thinking about one’s response to those descriptions is equally so. Without reflection, it is possible that important aspects never even make it into the fieldnotes because they seem “unremarkable.”

The Data of Observational Work: Fieldnotes

In interview data collection, recordings of interviews are transcribed into the data of the study. This is not possible for much PO work because (1) aural recordings of observations aren’t possible and (2) conversations that take place on-site are not easily recorded. Instead, the participant observer takes notes, either during the fieldwork or at the day’s end. These notes, called “fieldnotes,” are then the primary form of data for PO work.

Writing fieldnotes takes a lot of time. Because fieldnotes are your primary form of data, you cannot be stingy with the time it takes. Most practitioners suggest it takes at least the same amount of time to write up notes as it takes to be in the field, and many suggest it takes double the time. If you spend three hours at a meeting of the organization you are observing, it is a good idea to set aside five to six hours to write out your fieldnotes. Different researchers use different strategies about how and when to do this. Somewhat obviously, the earlier you can write down your notes, the more likely they are to be accurate. Writing them down at the end of the day is thus the default practice. However, if you are plainly exhausted, spending several hours trying to recall important details may be counterproductive. Writing fieldnotes the next morning, when you are refreshed and alert, may work better.

Reseaarcher Note

How do you take fieldnotes ? Any advice for those wanting to conduct an ethnographic study?

Fieldnotes are so important, especially for qualitative researchers. A little advice when considering how you approach fieldnotes: Record as much as possible! Sometimes I write down fieldnotes, and I often audio-record them as well to transcribe later. Sometimes the space to speak what I observed is helpful and allows me to be able to go a little more in-depth or to talk out something that I might not quite have the words for just yet. Within my fieldnote, I include feelings and think about the following questions: How do I feel before data collection? How did I feel when I was engaging/watching? How do I feel after data collection? What was going on for me before this particular data collection? What did I notice about how folks were engaging? How were participants feeling, and how do I know this? Is there anything that seems different than other data collections? What might be going on in the world that might be impacting the participants? As a qualitative researcher, it’s also important to remember our own influences on the research—our feelings or current world news may impact how we observe or what we might capture in fieldnotes.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

What should be included in those fieldnotes? The obvious answer is “everything you observed and heard relevant to your research question.” The difficulty is that you often don’t know what is relevant to your research question when you begin, as your research question itself can develop and transform during the course of your observations. For example, let us say you begin a study of second-grade classrooms with the idea that you will observe gender dynamics between both teacher and students and students and students. But after five weeks of observation, you realize you are taking a lot of notes about how teachers validate certain attention-seeking behaviors among some students while ignoring those of others. For example, when Daisy (White female) interrupts a discussion on frogs to tell everyone she has a frog named Ribbit, the teacher smiles and asks her to tell the students what Ribbit is like. In contrast, when Solomon (Black male) interrupts a discussion on the planets to tell everyone his big brother is called Jupiter by their stepfather, the teacher frowns and shushes him. These notes spark interest in how teachers favor and develop some students over others and the role of gender, race, and class in these teacher practices. You then begin to be much more careful in recording these observations, and you are a little less attentive to the gender dynamics among students. But note that had you not been fairly thorough in the first place, these crucial insights about teacher favoritism might never have been made.

Here are some suggestions for things to include in your fieldnotes as you begin: (1) descriptions of the physical setting; (2) people in the site: who they are and how they interact with one another (what roles they are taking on); and (3) things overheard: conversations, exchanges, questions. While you should develop your own personal system for organizing these fieldnotes (computer vs. printed journal, for example), at a minimum, each set of fieldnotes should include the date, time in the field, persons observed, and location specifics. You might also add keywords to each set so that you can search by names of participants, dates, and locations. Lareau ( 2021:167 ) recommends covering the following key issues, which mnemonically spell out WRITE— W : who, what, when, where, how; R: reaction (responses to the action in question and the response to the response); I: inaction (silence or nonverbal response to an action); T: timing (how slowly or quickly someone is speaking); and E: emotions (nonverbal signs of emotion and/or stoicism).

In addition to the observational fieldnotes, if you have time, it is a good practice to write reflective memos in which you ask yourself what you have learned (either about the study or about your abilities in the field). If you don’t have time to do this for every set of fieldnotes, at least get in the practice of memoing at certain key junctures, perhaps after reading through a certain number of fieldnotes (e.g., every third day of fieldnotes, you set aside two hours to read through the notes and memo). These memos can then be appended to relevant fieldnotes. You will be grateful for them when it comes time to analyze your data, as they are a preliminary by-the-seat-of-your-pants analysis. They also help steer you toward the study you want to pursue rather than allow you to wallow in unfocused data.

Ethics of Fieldwork

Because most fieldwork requires multiple and intense interactions (even if merely observational) with real living people as they go about their business, there are potentially more ethical choices to be made. In addition to the ethics of gaining entry and permission discussed above, there are issues of accurate representation, of respecting privacy, of adequate financial compensation, and sometimes of financial and other forms of assistance (when observing/interacting with low-income persons or other marginalized populations). In other words, the ethical decision of fieldwork is never concluded by obtaining a signature on a consent form. Read this brief selection from Pascale’s ( 2021 ) methods description (observation plus interviews) to see how many ethical decisions she made:

Throughout I kept detailed ethnographic field and interview records, which included written notes, recorded notes, and photographs. I asked everyone who was willing to sit for a formal interview to speak only for themselves and offered each of them a prepaid Visa Card worth $25–40. I also offered everyone the opportunity to keep the card and erase the tape completely at any time they were dissatisfied with the interview in any way. No one asked for the tape to be erased; rather, people remarked on the interview being a really good experience because they felt heard. Each interview was professionally transcribed and for the most part the excerpts in this book are literal transcriptions. In a few places, the excerpta have been edited to reduce colloquial features of speech (e.g., you know, like, um) and some recursive elements common to spoken language. A few excerpts were placed into standard English for clarity. I made this choice for the benefit of readers who might otherwise find the insights and ideas harder to parse in the original. However, I have to acknowledge this as an act of class-based violence. I tried to keep the original phrasing whenever possible. ( 235 )

Summary Checklist for Successful Participant Observation

The following are ten suggestions for being successful in the field, slightly paraphrased from Patton ( 2002:331 ). Here, I take those ten suggestions and turn them into an extended “checklist” to use when designing and conducting fieldwork.

- Consider all possible approaches to your field and your position relative to that field (see figure 13.2). Choose wisely and purposely. If you have access to a particular site or are part of a particular culture, consider the advantages (and disadvantages) of pursuing research in that area. Clarify the amount of disclosure you are willing to share with those you are observing, and justify that decision.

- Take thorough and descriptive field notes. Consider how you will record them. Where your research is located will affect what kinds of field notes you can take and when, but do not fail to write them! Commit to a regular recording time. Your field notes will probably be the primary data source you collect, so your study’s success will depend on thick descriptions and analytical memos you write to yourself about what you are observing.

- Permit yourself to be flexible. Consider alternative lines of inquiry as you proceed. You might enter the field expecting to find something only to have your attention grabbed by something else entirely. This is perfectly fine (and, in some traditions, absolutely crucial for excellent results). When you do see your attention shift to an emerging new focus, take a step back, look at your original research design, and make careful decisions about what might need revising to adapt to these new circumstances.

- Include triangulated data as a means of checking your observations. If you are that ICU nurse watching patient/doctor interactions, you might want to add a few interviews with patients to verify your interpretation of the interaction. Or perhaps pull some public data on the number of arrests for jaywalking if you are the student accompanying police on their rounds to find out if the large number of arrests you witnessed was typical.

- Respect the people you are witnessing and recording, and allow them to speak for themselves whenever possible. Using direct quotes (recorded in your field notes or as supplementary recorded interviews) is another way to check the validity of the analyses of your observations. When designing your research, think about how you can ensure the voices of those you are interested in get included.

- Choose your informants wisely. Who are they relative to the field you are exploring? What are the limitations (ethical and strategic) in using those particular informants, guides, and gatekeepers? Limit your reliance on them to the extent possible.

- Consider all the stages of fieldwork, and have appropriate plans for each. Recognize that different talents are required at different stages of the data-collection process. In the beginning, you will probably spend a great deal of time building trust and rapport and will have less time to focus on what is actually occurring. That’s normal. Later, however, you will want to be more focused on and disciplined in collecting data while also still attending to maintaining relationships necessary for your study’s success. Sometimes, especially when you have been invited to the site, those granting access to you will ask for feedback. Be strategic about when giving that feedback is appropriate. Consider how to extricate yourself from the site and the participants when your study is coming to an end. Have an ethical exit plan.

- Allow yourself to be immersed in the scene you are observing. This is true even if you are observing a site as an outsider just one time. Make an effort to see things through the eyes of the participants while at the same time maintaining an analytical stance. This is a tricky balance to do, of course, and is more of an art than a science. Practice it. Read about how others have achieved it.

- Create a practice of separating your descriptive notes from your analytical observations. This may be as clear as dividing a sheet of paper into two columns, one for description only and the other for questions or interpretation (as we saw in chapter 11 on interviewing), or it may mean separating out the time you dedicate to descriptions from the time you reread and think deeply about those detailed descriptions. However you decide to do it, recognize that these are two separate activities, both of which are essential to your study’s success.

- As always with qualitative research, be reflective and reflexive. Do not forget how your own experience and social location may affect both your interpretation of what you observe and the very things you observe themselves (e.g., where a patient says more forgiving things about an observably rude doctor because they read you, a nursing student, as likely to report any negative comments back to the doctor). Keep a research journal!

Further Readings

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes . 2nd ed. University of Chicago Press. Excellent guide that uses actual unfinished fieldnote to illustrate various options for composing, reviewing, and incorporating fieldnote into publications.

Lareau, Annette. 2021. Listening to People: A Practical Guide to Interviewing, Participant Observation, Data Analysis, and Writing It All Up . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Includes actual fieldnote from various studies with a really helpful accompanying discussion about how to improve them!

Wolfinger, Nicholas H. 2002. “On Writing Fieldnotes: Collection Strategies and Background Expectancies.” Qualitative Research 2(1):85–95. Uses fieldnote from various sources to show how the researcher’s expectations and preexisting knowledge affect what gets written about; offers strategies for taking useful fieldnote.

- Note that leaving one’s office to interview someone in a coffee shop would not be considered fieldwork because the coffee shop is not an element of the study. If one sat down in a coffee shop and recorded observations, then this would be fieldwork. ↵

- This is one reason why I have chosen to discuss deep ethnography in a separate chapter (chapter 14). ↵

- This person is sometimes referred to as the [pb_glossary id="389"]informant [/pb_glossary](and more on these characters in chapter 14). ↵

Methodological tradition of inquiry that holds the view that all social interaction is dependent on shared views of the world and each other, characterized through people’s use of language and non-verbal communication. Through interactions, society comes to be. The goal of the researcher in this tradition is to trace that construction, as in the case of documenting how gender is “done” or performed, demonstrating the fluidity of the concept (and how it is constantly being made and remade through daily interactions).

Used primarily in ethnography , as in the goal of fieldnotes is to produce a thick description of what is both observed directly (actions, actors, setting, etc.) and the meanings and interpretations being made by those actors at the time. In this way, the observed cultural and social relationships are contextualized for future interpretation. The opposite of a thick description is a thin description, in which observations are recorded without any social context or cues to help explain them. The term was coined by anthropologist Clifford Geertz (see chapter 14 ).

Reflective summaries of findings that emerge during analysis of qualitative data; they can include reminders to oneself for future analyses or considerations, reinterpretations or generations of codes, or brainstorms and concept mapping.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Observation Method in Psychology: Naturalistic, Participant and Controlled

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

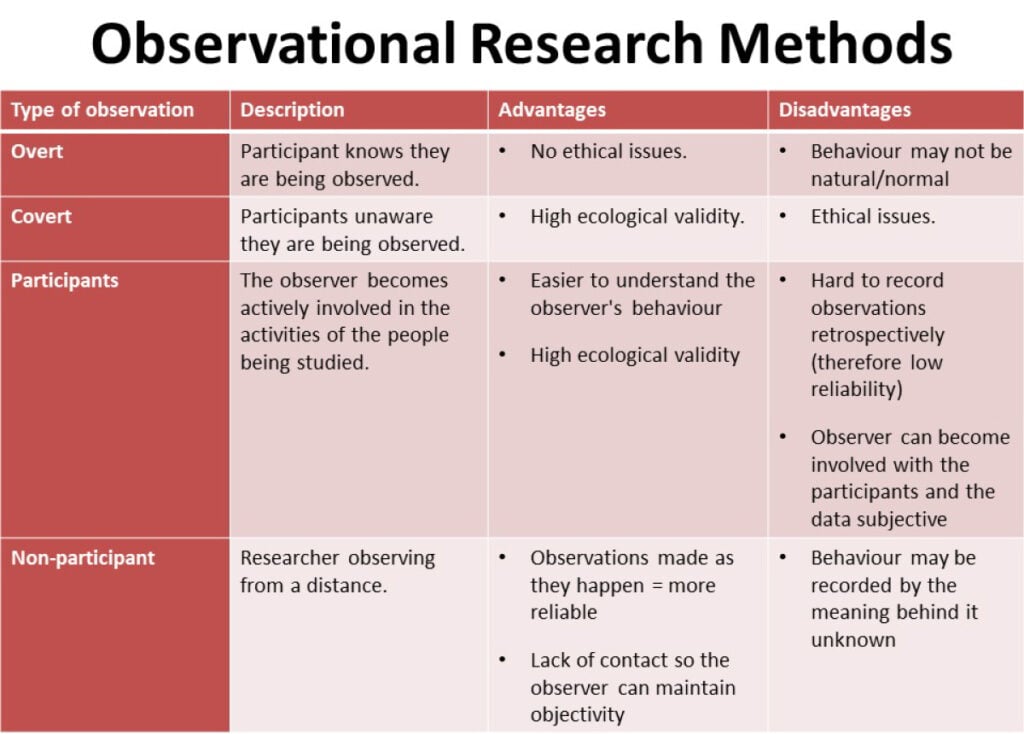

The observation method in psychology involves directly and systematically witnessing and recording measurable behaviors, actions, and responses in natural or contrived settings without attempting to intervene or manipulate what is being observed.

Used to describe phenomena, generate hypotheses, or validate self-reports, psychological observation can be either controlled or naturalistic with varying degrees of structure imposed by the researcher.

There are different types of observational methods, and distinctions need to be made between:

1. Controlled Observations 2. Naturalistic Observations 3. Participant Observations

In addition to the above categories, observations can also be either overt/disclosed (the participants know they are being studied) or covert/undisclosed (the researcher keeps their real identity a secret from the research subjects, acting as a genuine member of the group).

In general, conducting observational research is relatively inexpensive, but it remains highly time-consuming and resource-intensive in data processing and analysis.

The considerable investments needed in terms of coder time commitments for training, maintaining reliability, preventing drift, and coding complex dynamic interactions place practical barriers on observers with limited resources.

Controlled Observation

Controlled observation is a research method for studying behavior in a carefully controlled and structured environment.

The researcher sets specific conditions, variables, and procedures to systematically observe and measure behavior, allowing for greater control and comparison of different conditions or groups.

The researcher decides where the observation will occur, at what time, with which participants, and in what circumstances, and uses a standardized procedure. Participants are randomly allocated to each independent variable group.

Rather than writing a detailed description of all behavior observed, it is often easier to code behavior according to a previously agreed scale using a behavior schedule (i.e., conducting a structured observation).

The researcher systematically classifies the behavior they observe into distinct categories. Coding might involve numbers or letters to describe a characteristic or the use of a scale to measure behavior intensity.

The categories on the schedule are coded so that the data collected can be easily counted and turned into statistics.

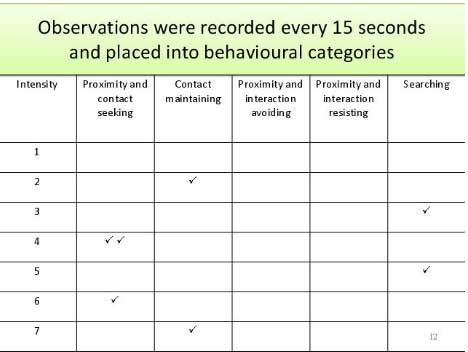

For example, Mary Ainsworth used a behavior schedule to study how infants responded to brief periods of separation from their mothers. During the Strange Situation procedure, the infant’s interaction behaviors directed toward the mother were measured, e.g.,

- Proximity and contact-seeking

- Contact maintaining

- Avoidance of proximity and contact

- Resistance to contact and comforting

The observer noted down the behavior displayed during 15-second intervals and scored the behavior for intensity on a scale of 1 to 7.

Sometimes participants’ behavior is observed through a two-way mirror, or they are secretly filmed. Albert Bandura used this method to study aggression in children (the Bobo doll studies ).

A lot of research has been carried out in sleep laboratories as well. Here, electrodes are attached to the scalp of participants. What is observed are the changes in electrical activity in the brain during sleep ( the machine is called an EEG ).

Controlled observations are usually overt as the researcher explains the research aim to the group so the participants know they are being observed.

Controlled observations are also usually non-participant as the researcher avoids direct contact with the group and keeps a distance (e.g., observing behind a two-way mirror).

- Controlled observations can be easily replicated by other researchers by using the same observation schedule. This means it is easy to test for reliability .

- The data obtained from structured observations is easier and quicker to analyze as it is quantitative (i.e., numerical) – making this a less time-consuming method compared to naturalistic observations.

- Controlled observations are fairly quick to conduct which means that many observations can take place within a short amount of time. This means a large sample can be obtained, resulting in the findings being representative and having the ability to be generalized to a large population.

Limitations

- Controlled observations can lack validity due to the Hawthorne effect /demand characteristics. When participants know they are being watched, they may act differently.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is a research method in which the researcher studies behavior in its natural setting without intervention or manipulation.

It involves observing and recording behavior as it naturally occurs, providing insights into real-life behaviors and interactions in their natural context.

Naturalistic observation is a research method commonly used by psychologists and other social scientists.

This technique involves observing and studying the spontaneous behavior of participants in natural surroundings. The researcher simply records what they see in whatever way they can.

In unstructured observations, the researcher records all relevant behavior with a coding system. There may be too much to record, and the behaviors recorded may not necessarily be the most important, so the approach is usually used as a pilot study to see what type of behaviors would be recorded.

Compared with controlled observations, it is like the difference between studying wild animals in a zoo and studying them in their natural habitat.

With regard to human subjects, Margaret Mead used this method to research the way of life of different tribes living on islands in the South Pacific. Kathy Sylva used it to study children at play by observing their behavior in a playgroup in Oxfordshire.

Collecting Naturalistic Behavioral Data

Technological advances are enabling new, unobtrusive ways of collecting naturalistic behavioral data.

The Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR) is a digital recording device participants can wear to periodically sample ambient sounds, allowing representative sampling of daily experiences (Mehl et al., 2012).

Studies program EARs to record 30-50 second sound snippets multiple times per hour. Although coding the recordings requires extensive resources, EARs can capture spontaneous behaviors like arguments or laughter.

EARs minimize participant reactivity since sampling occurs outside of awareness. This reduces the Hawthorne effect, where people change behavior when observed.

The SenseCam is another wearable device that passively captures images documenting daily activities. Though primarily used in memory research currently (Smith et al., 2014), systematic sampling of environments and behaviors via the SenseCam could enable innovative psychological studies in the future.

- By being able to observe the flow of behavior in its own setting, studies have greater ecological validity.

- Like case studies , naturalistic observation is often used to generate new ideas. Because it gives the researcher the opportunity to study the total situation, it often suggests avenues of inquiry not thought of before.

- The ability to capture actual behaviors as they unfold in real-time, analyze sequential patterns of interactions, measure base rates of behaviors, and examine socially undesirable or complex behaviors that people may not self-report accurately.

- These observations are often conducted on a micro (small) scale and may lack a representative sample (biased in relation to age, gender, social class, or ethnicity). This may result in the findings lacking the ability to generalize to wider society.

- Natural observations are less reliable as other variables cannot be controlled. This makes it difficult for another researcher to repeat the study in exactly the same way.

- Highly time-consuming and resource-intensive during the data coding phase (e.g., training coders, maintaining inter-rater reliability, preventing judgment drift).

- With observations, we do not have manipulations of variables (or control over extraneous variables), meaning cause-and-effect relationships cannot be established.

Participant Observation

Participant observation is a variant of the above (natural observations) but here, the researcher joins in and becomes part of the group they are studying to get a deeper insight into their lives.

If it were research on animals , we would now not only be studying them in their natural habitat but be living alongside them as well!

Leon Festinger used this approach in a famous study into a religious cult that believed that the end of the world was about to occur. He joined the cult and studied how they reacted when the prophecy did not come true.

Participant observations can be either covert or overt. Covert is where the study is carried out “undercover.” The researcher’s real identity and purpose are kept concealed from the group being studied.

The researcher takes a false identity and role, usually posing as a genuine member of the group.

On the other hand, overt is where the researcher reveals his or her true identity and purpose to the group and asks permission to observe.

- It can be difficult to get time/privacy for recording. For example, researchers can’t take notes openly with covert observations as this would blow their cover. This means they must wait until they are alone and rely on their memory. This is a problem as they may forget details and are unlikely to remember direct quotations.

- If the researcher becomes too involved, they may lose objectivity and become biased. There is always the danger that we will “see” what we expect (or want) to see. This problem is because they could selectively report information instead of noting everything they observe. Thus reducing the validity of their data.

Recording of Data

With controlled/structured observation studies, an important decision the researcher has to make is how to classify and record the data. Usually, this will involve a method of sampling.

In most coding systems, codes or ratings are made either per behavioral event or per specified time interval (Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

The three main sampling methods are:

Event-based coding involves identifying and segmenting interactions into meaningful events rather than timed units.

For example, parent-child interactions may be segmented into control or teaching events to code. Interval recording involves dividing interactions into fixed time intervals (e.g., 6-15 seconds) and coding behaviors within each interval (Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

Event recording allows counting event frequency and sequencing while also potentially capturing event duration through timed-event recording. This provides information on time spent on behaviors.

Coding Systems

The coding system should focus on behaviors, patterns, individual characteristics, or relationship qualities that are relevant to the theory guiding the study (Wampler & Harper, 2014).

Codes vary in how much inference is required, from concrete observable behaviors like frequency of eye contact to more abstract concepts like degree of rapport between a therapist and client (Hill & Lambert, 2004). More inference may reduce reliability.

Macroanalytic coding systems

Macroanalytic coding systems involve rating or summarizing behaviors using larger coding units and broader categories that reflect patterns across longer periods of interaction rather than coding small or discrete behavioral acts.

For example, a macroanalytic coding system may rate the overall degree of therapist warmth or level of client engagement globally for an entire therapy session, requiring the coders to summarize and infer these constructs across the interaction rather than coding smaller behavioral units.

These systems require observers to make more inferences (more time-consuming) but can better capture contextual factors, stability over time, and the interdependent nature of behaviors (Carlson & Grotevant, 1987).

Microanalytic coding systems

Microanalytic coding systems involve rating behaviors using smaller, more discrete coding units and categories.

For example, a microanalytic system may code each instance of eye contact or head nodding during a therapy session. These systems code specific, molecular behaviors as they occur moment-to-moment rather than summarizing actions over longer periods.

Microanalytic systems require less inference from coders and allow for analysis of behavioral contingencies and sequential interactions between therapist and client. However, they are more time-consuming and expensive to implement than macroanalytic approaches.

Mesoanalytic coding systems

Mesoanalytic coding systems attempt to balance macro- and micro-analytic approaches.

In contrast to macroanalytic systems that summarize behaviors in larger chunks, mesoanalytic systems use medium-sized coding units that target more specific behaviors or interaction sequences (Bakeman & Quera, 2017).

For example, a mesoanalytic system may code each instance of a particular type of therapist statement or client emotional expression. However, mesoanalytic systems still use larger units than microanalytic approaches coding every speech onset/offset.

The goal of balancing specificity and feasibility makes mesoanalytic systems well-suited for many research questions (Morris et al., 2014). Mesoanalytic codes can preserve some sequential information while remaining efficient enough for studies with adequate but limited resources.

For instance, a mesoanalytic couple interaction coding system could target key behavior patterns like validation sequences without coding turn-by-turn speech.

In this way, mesoanalytic coding allows reasonable reliability and specificity without requiring extensive training or observation. The mid-level focus offers a pragmatic compromise between depth and breadth in analyzing interactions.

Preventing Coder Drift

Coder drift results in a measurement error caused by gradual shifts in how observations get rated according to operational definitions, especially when behavioral codes are not clearly specified.

This type of error creeps in when coders fail to regularly review what precise observations constitute or do not constitute the behaviors being measured.

Preventing drift refers to taking active steps to maintain consistency and minimize changes or deviations in how coders rate or evaluate behaviors over time. Specifically, some key ways to prevent coder drift include:

- Operationalize codes : It is essential that code definitions unambiguously distinguish what interactions represent instances of each coded behavior.

- Ongoing training : Returning to those operational definitions through ongoing training serves to recalibrate coder interpretations and reinforce accurate recognition. Having regular “check-in” sessions where coders practice coding the same interactions allows monitoring that they continue applying codes reliably without gradual shifts in interpretation.

- Using reference videos : Coders periodically coding the same “gold standard” reference videos anchors their judgments and calibrate against original training. Without periodic anchoring to original specifications, coder decisions tend to drift from initial measurement reliability.

- Assessing inter-rater reliability : Statistical tracking that coders maintain high levels of agreement over the course of a study, not just at the start, flags any declines indicating drift. Sustaining inter-rater agreement requires mitigating this common tendency for observer judgment change during intensive, long-term coding tasks.

- Recalibrating through discussion : Having meetings for coders to discuss disagreements openly explores reasons judgment shifts may be occurring over time. Consensus on the application of codes is restored.

- Adjusting unclear codes : If reliability issues persist, revisiting and refining ambiguous code definitions or anchors can eliminate inconsistencies arising from coder confusion.

Essentially, the goal of preventing coder drift is maintaining standardization and minimizing unintentional biases that may slowly alter how observational data gets rated over periods of extensive coding.

Through the upkeep of skills, continuing calibration to benchmarks, and monitoring consistency, researchers can notice and correct for any creeping changes in coder decision-making over time.

Reducing Observer Bias

Observational research is prone to observer biases resulting from coders’ subjective perspectives shaping the interpretation of complex interactions (Burghardt et al., 2012). When coding, personal expectations may unconsciously influence judgments. However, rigorous methods exist to reduce such bias.

Coding Manual

A detailed coding manual minimizes subjectivity by clearly defining what behaviors and interaction dynamics observers should code (Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

High-quality manuals have strong theoretical and empirical grounding, laying out explicit coding procedures and providing rich behavioral examples to anchor code definitions (Lindahl, 2001).

Clear delineation of the frequency, intensity, duration, and type of behaviors constituting each code facilitates reliable judgments and reduces ambiguity for coders. Application risks inconsistency across raters without clarity on how codes translate to observable interaction.

Coder Training

Competent coders require both interpersonal perceptiveness and scientific rigor (Wampler & Harper, 2014). Training thoroughly reviews the theoretical basis for coded constructs and teaches the coding system itself.

Multiple “gold standard” criterion videos demonstrate code ranges that trainees independently apply. Coders then meet weekly to establish reliability of 80% or higher agreement both among themselves and with master criterion coding (Hill & Lambert, 2004).

Ongoing training manages coder drift over time. Revisions to unclear codes may also improve reliability. Both careful selection and investment in rigorous training increase quality control.

Blind Methods

To prevent bias, coders should remain unaware of specific study predictions or participant details (Burghardt et al., 2012). Separate data gathering versus coding teams helps maintain blinding.

Coders should be unaware of study details or participant identities that could bias coding (Burghardt et al., 2012).

Separate teams collecting data versus coding data can reduce bias.

In addition, scheduling procedures can prevent coders from rating data collected directly from participants with whom they have had personal contact. Maintaining coder independence and blinding enhances objectivity.

Bakeman, R., & Quera, V. (2017). Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Burghardt, G. M., Bartmess-LeVasseur, J. N., Browning, S. A., Morrison, K. E., Stec, C. L., Zachau, C. E., & Freeberg, T. M. (2012). Minimizing observer bias in behavioral studies: A review and recommendations. Ethology, 118 (6), 511-517.

Hill, C. E., & Lambert, M. J. (2004). Methodological issues in studying psychotherapy processes and outcomes. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 84–135). Wiley.

Lindahl, K. M. (2001). Methodological issues in family observational research. In P. K. Kerig & K. M. Lindahl (Eds.), Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research (pp. 23–32). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mehl, M. R., Robbins, M. L., & Deters, F. G. (2012). Naturalistic observation of health-relevant social processes: The electronically activated recorder methodology in psychosomatics. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74 (4), 410–417.

Morris, A. S., Robinson, L. R., & Eisenberg, N. (2014). Applying a multimethod perspective to the study of developmental psychology. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (2nd ed., pp. 103–123). Cambridge University Press.

Smith, J. A., Maxwell, S. D., & Johnson, G. (2014). The microstructure of everyday life: Analyzing the complex choreography of daily routines through the automatic capture and processing of wearable sensor data. In B. K. Wiederhold & G. Riva (Eds.), Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine 2014: Positive Change with Technology (Vol. 199, pp. 62-64). IOS Press.

Traniello, J. F., & Bakker, T. C. (2015). The integrative study of behavioral interactions across the sciences. In T. K. Shackelford & R. D. Hansen (Eds.), The evolution of sexuality (pp. 119-147). Springer.

Wampler, K. S., & Harper, A. (2014). Observational methods in couple and family assessment. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (2nd ed., pp. 490–502). Cambridge University Press.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Participant observation: What it is, types & uses

Participant observation has been widely used in disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, communication studies, political science, social psychology, and even in market research.

To help you get a broad overview of this methodology, in this article we have compiled its most important characteristics, its importance, and some of the types of participant observation that you can put into practice for your next study.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

What is participant observation?

Participant observation is a qualitative research methodology in which the researcher studies a group not only through observation, but also by participating in its activities.

In this qualitative observation methodology, the researcher immerses himself in the daily activities of the participants in order to record the behavior in as many scenarios as possible.

Thanks to the immersion in the study place, the researchers can observe the daily life of the people: their exchanges with each other, their formal and informal conversations, habits, etc.

It offers researchers the opportunity to collect honest and intimate information about people. However, this information is filtered through the perspective of researchers who, by using this method, run the risk of losing their objectivity and altering with their presence the behavior of the groups they study.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

Importance of participant observation

Participant observation is a method that helps you see and understand what people are doing and compare it with what they say. In this way, you help researchers know if the people with whom you are conducting a study act differently from what they are described.

It also allows the researcher to better understand what is happening in a given group and its cultural environment, giving greater credibility to their interpretations of the observation.

In addition, it allows the researcher to collect qualitative data through various types of interviews and quantitative data through surveys and different quantitative observation techniques.

Characteristics of participant observation

Participant observation has historically been associated with a form of field research in which the researcher resides for long periods of time in a small community.

Today, this methodology is used in a wide variety of settings and for widely varying periods of time, from a single interaction to many years. But it is usually characterized by the following points:

- The long-term nature of the interaction between the researcher and the participants as part of the fieldwork process.

- A wide range of relationship dynamics that it studies, such as differences in status between the two parties, differences in power and educational differences, as well as degrees of formality. Differences in power can have their origin in gender, social class, health and other aspects.

- The variety of settings, from close interpersonal interactions to observing public gatherings and actual participation in social events.

- In many cases, research takes place in settings unfamiliar to the researcher, which will make her presentation and interaction with others especially sensitive.

- There may be different ethical codes between the groups studied and those of the researcher’s country or institution of origin. They may also differ from the ethical principles followed by the host government, non-governmental organizations in the area, or agencies funding the research .

- The changing nature of the researcher’s roles and relationships with the studied group over time.

- The use of technology to document observations, including mapping, photography, and video and audio recording.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

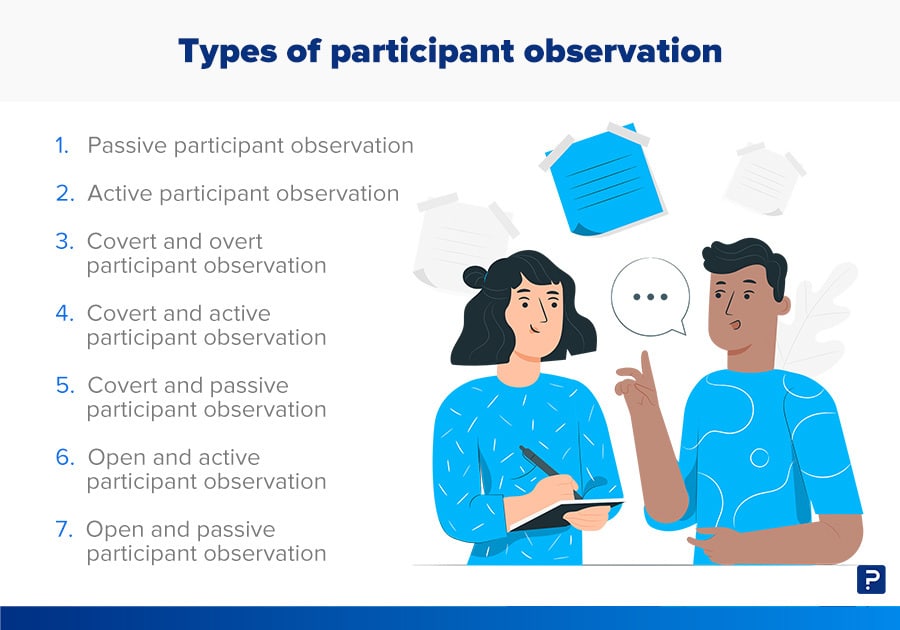

Types of participant observation

Now that you know what this method is and what its most common characteristics are, we will introduce you to the types that exist.

Passive participant observation

Researchers observe and record the behaviors of their subjects in their own environment without conversing or interacting with them in any way.

Many of the studies that use this form of participant observation are studies in which researchers observe people’s behavior and communications in public places, such as restaurants, coffee shops, transportation hubs, and even on the Internet through innovative methods such as netnography .

Active participant observation

In this way, researchers converse with their subjects and participate in the daily life of the groups they study, including their activities, c ustoms, rituals, routines, etc.

The degree of commitment of researchers to these groups varies. Some researchers limit their interactions to interviews, while others engage in all aspects of their subjects’ lives.

Examples of this form of participant observation are studies in which researchers lived for long periods of time among different ethnic, cultural, or religious communities.

Covert and overt

In covert participant observation, researchers do not make their presence known to their subjects and, if they do, they do not identify themselves as investigators, whereas in open participant observation they do.

However, even when the investigation is open, investigators often do not inform the people they meet in the course of their investigation of the specific purpose of the investigation, nor do they inform everyone they meet that they are researchers, as this could unnecessarily interrupt conversations and events being observed.

Covert and active

Covert and active participant observation has several advantages. In this type of participant observation, researchers can have access to a group that they would not otherwise have the opportunity to observe, and they can experience the practices of the group as they are experienced by the members of the group.

Generally, researchers can alter group behavior by their presence, but in this form of participant observation, groups would not consciously change their behavior in response to the researcher’s presence because they are not aware of being observed.

Covert and passive

In the case of covert and passive participant observation, researchers are not likely to alter the behaviors of their subjects, since the researchers do not actively engage with their subjects and because the subjects are also not aware that they are being observed.

However, since observation is passive, researchers do not have the opportunity to experience the lives of their subjects for themselves.

Open and active

If observation is open and active, people can participate in and experience their subjects’ activities as their subjects would, but they run the risk of both changing the behavior of their subjects through their interactions with them, and that their subjects change their behavior by themselves knowing that they are being studied.

Open and passive

As in the case of covert and passive participant observation, researchers do not run the risk that their presence alters the behavior of the groups they study through their interactions with them.

However, the guinea pig effect is a problem for this form of observation, unlike the case of covert and passive participant observation, because the participants are aware that they are being studied. Furthermore, researchers cannot experience the world as it is as subjects would.

As you can see, participant observation is a research method that provides valuable information about the social and cultural relationships of a group or community over time.

Uncover the insights that matter the most. Use QuestionPro’s market research platform to uncover complex insights that can propel your business to the forefront of your industry.

MORE LIKE THIS

Customer Experience Automation: Benefits and Best Tools

Apr 1, 2024

7 Best Market Segmentation Tools in 2024

In-App Feedback Tools: How to Collect, Uses & 14 Best Tools

Mar 29, 2024

11 Best Customer Journey Analytics Software in 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

What Is Participant Observation Research?

Understanding an Important Qualitative Research Method

Zero Creatives / Getty Images

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

The participant observation method, also known as ethnographic research , is when a sociologist actually becomes a part of the group they are studying in order to collect data and understand a social phenomenon or problem. During participant observation, the researcher works to play two separate roles at the same time: subjective participant and objective observer. Sometimes, though not always, the group is aware that the sociologist is studying them.

The goal of participant observation is to gain a deep understanding and familiarity with a certain group of individuals, their values, beliefs, and way of life. Often the group in focus is a subculture of a greater society, like a religious, occupational, or particular community group. To conduct participant observation, the researcher often lives within the group, becomes a part of it, and lives as a group member for an extended period of time, allowing them access to the intimate details and goings-on of the group and their community.

This research method was pioneered by anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski and Franz Boas but was adopted as a primary research method by many sociologists affiliated with the Chicago School of Sociology in the early twentieth century . Today, participant observation, or ethnography, is a primary research method practiced by qualitative sociologists around the world.

Subjective Versus Objective Participation

Participant observation requires the researcher to be a subjective participant in the sense that they use knowledge gained through personal involvement with the research subjects to interact with and gain further access to the group. This component supplies a dimension of information that is lacking in survey data . Participant observation research also requires the researcher to aim to be an objective observer and record everything that he or she has seen, not letting feelings and emotions influence their observations and findings.

Yet, most researchers recognize that true objectivity is an ideal, not an actuality, given that the way in which we see the world and people in it is always shaped by our previous experiences and our positionality in the social structure relative to others. As such, a good participant observer will also maintain a critical self-reflexivity that allows her to recognize the way she herself might influence the field of research and the data she collects.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The strengths of participant observation include the depth of knowledge that it allows the researcher to obtain and the perspective of knowledge of social problems and phenomena generated from the level of the everyday lives of those experiencing them. Many consider this an egalitarian research method because it centers the experiences, perspectives, and knowledge of those studied. This type of research has been the source of some of the most striking and valuable studies in sociology.