Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Quality Matters

Barriers to high-quality ece, steps to improve quality ece, recommendations for pediatricians, recommendations for community-level actions, recommendations for national- and state-level actions, lead author, council on early childhood executive committee, 2015–2016, quality early education and child care from birth to kindergarten.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Elaine A. Donoghue , COUNCIL ON EARLY CHILDHOOD , Dina Lieser , Beth DelConte , Elaine Donoghue , Marian Earls , Danette Glassy , Alan Mendelsohn , Terri McFadden , Seth Scholer , Jennifer Takagishi , Douglas Vanderbilt , P. Gail Williams; Quality Early Education and Child Care From Birth to Kindergarten. Pediatrics August 2017; 140 (2): e20171488. 10.1542/peds.2017-1488

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

High-quality early education and child care for young children improves physical and cognitive outcomes for the children and can result in enhanced school readiness. Preschool education can be viewed as an investment (especially for at-risk children), and studies show a positive return on that investment. Barriers to high-quality early childhood education include inadequate funding and staff education as well as variable regulation and enforcement. Steps that have been taken to improve the quality of early education and child care include creating multidisciplinary, evidence-based child care practice standards; establishing state quality rating and improvement systems; improving federal and state regulations; providing child care health consultation; as well as initiating other innovative partnerships. Pediatricians have a role in promoting quality early education and child care for all children not only in the medical home but also at the community, state, and national levels.

Children’s early experiences are all educational, whether they are at home, with extended family and friends, or in early education and child care settings. Those educational experiences can be positive or negative. At present, more than half of children less than 5 years old regularly attend some type of out-of-home child care or early childhood program, 1 and their experiences in these settings will affect their future lives. 1 The arrangements families make for their children can vary dramatically, including care by parents and relatives, center-based child care, family child care provided in a caregiver’s home, care provided in a child’s own home by nannies or baby-sitters, or a combination of these types of care. 1 , – 3 How a family chooses this care is influenced by family values, affordability, and availability. 2 , 4 For many families, high-quality child care is not available or affordable. 2 , 4 This policy statement outlines the importance of quality child care and what pediatricians can do to help children get care in high-quality early childhood education (ECE) settings.

When care is consistent, developmentally appropriate, and emotionally supportive, and the environment is healthy and safe, there is a positive effect on children and their families. 5 , – 14 Children who are exposed to poor-quality environments (whether at home or outside the home) are more likely to have unmet socioemotional needs and be less prepared for school demands. 5 , – 14 Behavioral problems in ECE can lead to preschool expulsion with cascading negative consequences. Each year, 5000 children are expelled from ECE settings, which is a rate 3 times higher than that of their school-aged counterparts. 15 When behavioral health consultation is available to preschool teachers, the rate of reported expulsions is half that of the control population. 15 , 16

Early education does not exist in a silo; learning begins at birth and occurs in all environments. Early brain and child development research unequivocally demonstrates that human development is powerfully affected by contextual surroundings and experiences. 17 , – 19 A child’s day-to-day experiences affect the structural and functional development of his or her brain, including his or her intelligence and personality. 17 , – 19 Children begin to learn to regulate their emotions, solve problems, express their feelings, and organize their experiences at an early age and then use those skills when they arrive at school. 19 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recognized the importance of early brain and child development by making it a strategic priority.

Research of high-quality, intensive ECE programs for low-income children confirm lasting positive effects such as improved cognitive and social abilities (including better math and language skills than control groups). 5 , – 14 The indicators of high-quality ECE have been studied and are summarized in Table 1 .

Domains of Health and Safety Quality in ECE

Adapted from Stepping Stones 20

There are different staff-to-child ratios for small-family homes, large-family homes, and centers. Ratios are also based on the ages of the children. Specific staff-to-child ratios are described in standard (1.1.1.2). 21

Many families have no quality child care options in their immediate communities. 2 The positive effects from high-quality programs and the negative effects from poor-quality programs are magnified in children from disadvantaged situations or with special needs, and yet, these children are least likely to have access to quality early education and child care. 2 , 4 , 22 , 23 Barriers to high-quality ECE include inadequate funding and staff education as well as inconsistent regulation and enforcement. 15 Funding on the federal, state, and local levels (even when combined with parental fees) often does not provide adequate financial support to ensure proper training, reasonable compensation, or career advancement opportunities for the early education workforce. 2 , – 4 , 22 , – 25 Adequate compensation of early education providers promotes quality by recruiting and retaining trained staff and their directors. Young children, especially infants and toddlers, need stable, positive relationships with their caregivers to thrive, and staff retention helps maintain those strong relationships. 19 Budget restrictions also limit the number of children who can be served. 22 As of 2012, 23 states had wait lists for their child care subsidy programs, and many areas have wait lists for Head Start programs. 4 Finally, budget restrictions may limit a program’s ability to hire child care health consultants. ECE settings rarely have health professionals like school nurses despite the fact that the children served are younger, less able to express their symptoms, and are prone to more frequent infectious illnesses. 26 Some states require child care health consultants to visit infant and toddler programs regularly.

State regulations of ECE programs vary dramatically because of an absence of national regulation, and this contributes to variation in ECE quality. Family child care settings have different regulations than center-based care, and some forms of child care are exempt from regulation. 23 , 25 , 27 The variability in regulation, staff screening, staff training, and the availability of supports such as child care health consultation contribute to a wide variation in quality. Even when regulations are present, enforcement varies, and only 44 states conduct annual health and safety inspections. 23 , 25

The definition of quality in ECE is becoming more evidence based as newer, validated measures become available. State licensing standards have been the traditional benchmarks, but they set a minimum standard that is typically considerably less than the recommendations of health and safety experts. 20 , 21 , 23 , 25 , 27 , 28 National organizations including the AAP, the American Public Health Association, and the National Association for the Education of Young Children have developed standards and voluntary systems of accreditation that are often more robust than state licensing regulations. The publication Caring for Our Children, Third Edition 21 includes evidence-based practice standards for nutrition, safety, hygiene, staff-to-child ratios, and numerous other subjects that have been shown to improve the quality of child care. 29 , 30

The quality rating and improvement system (QRIS) is a method of quality improvement that is being implemented in >75% of states. 25 QRISs use research-based, measurable standards to define quality levels, which are often denoted by a star rating system. QRISs often use incentives (such as staff scholarships, tiered reimbursement for child care subsidies, and technical assistance and/or professional development) as strategies to improve ECE quality. Unfortunately, the QRIS does not always include key health and safety standards. Those who are responsible for implementing QRISs would benefit from input from pediatricians, who are familiar with health issues and with the challenges of translating research into practice. Child care resource and referral agencies are available nationwide, and they serve as regional resources for information about quality child care. They often also serve as a resource for QRIS implementation; however, most child care resource and referral agencies do not have adequate funding to hire early childhood health consultants as part of that technical assistance.

Improving access to child care health consultation is another way to positively affect the health and safety of children in ECE. Child care health consultants are health professionals who are trained to provide technical assistance and develop policies about health issues, such as medication administration, infection control, immunization, and injury prevention. 31 Child care health consultants also can provide developmental, hearing, oral health, and vision screenings and provide assistance with integrating children with special health care needs into ECE settings. 29 , 32 , 33

The opportunities to use ECE programs to teach healthy habits (including healthy food choices, increased physical activity, and oral health practices) should not be overlooked. These messages can then be shared with families. Health screening services (such as vision and dental testing) also can be provided.

Innovative strategies to promote access to quality care and education also include state initiatives to promote cross-disciplinary teams (such as Early Childhood Advisory Councils), public-private funding partnerships, and universal preschool programs.

Ask families what child care arrangements they have made for their children, and educate them about the importance of high-quality child care. Resources include brochures (listed in Resources); checklists of quality, which can be accessed at www.aap.org/healthychildcare ; and referrals to local child care resources and referral agencies, which can be found at www.childcareaware.org .

Become educated about high-quality child care through the resources on the Healthy Child Care America Web site ( www.healthychildcare.org ), in Caring for Our Children , 21 and others (see Resources).

Be a medical home by participating in the 3-way collaboration with families and ECE professionals. The medical home concept of comprehensive, coordinated care is particularly critical for children with special health care needs. Three-way communication among the pediatricians, families, and ECEs can facilitate shared knowledge of the unique child care needs of children with special needs and foster implementation of child care policies and practices to meet those needs. 32 , 33 These activities are likely to improve access to ECE for these patients. Detailed care plans written in lay language assist in this collaboration. Medical team-based or time-based coding and billing may provide support for these efforts.

Advise families and early educators when children are having behavioral problems in ECE and are at risk for expulsion. Explain the triggers for behavior problems and recommend behavioral health resources as needed. 16 Some states have behavioral health resources available for young children through an Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation program. Read the AAP policy statement and technical report on toxic stress 19 and learn about the resources that are available through each state’s early care and education system.

Discuss the importance of guidelines on safe sleep, immunization, safe medication administration, infection control, healthy diet and physical activity, oral health, medical home access, and other health topics with local child care centers. Share resources such as Caring for Our Children , 21 Bright Futures , and the Healthy Child Care Web site ( www.healthychildcare.org ).

Become a child care health consultant or support your local child care health consultant nurses. Consider conducting a health and safety assessment in a local child care program by using a national health and safety checklist ( www.ucsfchildcarehealth.org ).

Educate policy makers about the science that supports the benefits of quality early child care and education and, conversely, the lost opportunities and setbacks that result from poor-quality care. 15 , 24

Close the gaps between state regulations and the quality standards outlined in Caring for Our Children by encouraging strong state regulation and enforcement. Each AAP chapter has a legislative group that can help target these public policy makers with visits and letters. Nearly every AAP chapter also has an Early Childhood Champion, a pediatrician who is familiar with the early education and child care needs in that chapter and has knowledge about local resources to assist your efforts. Find your Early Childhood Champion at www.aap.org/coec .

Support a QRIS in your state if one is being implemented, and encourage robust child health and safety standards based on Caring for Our Children .

Advocate for improved funding for child care health consultation.

Encourage training of ECE professionals on health and safety topics, such as medication administration and safe sleep practices for infants. Consider providing training that uses the Healthy Futures curriculum provided on the Healthy Child Care Web site ( www.healthychildcare.org ).

Advocate and encourage expanded access to high-quality ECE through funding, such as expanded Child Care Developmental Block grants or Head Start funding. Reach out to legislators on the national and state levels to make the case for investing in quality early education as a good business, education, and social investment that has shown a strong return on investment. Encourage pediatric representation on state Early Childhood Advisory Councils or similar state groups to make the case to state officials personally.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Choosing Child Care: What’s Best for Your Family [Pamphlet]. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002. Available through the AAP publications department: 800/433-9016 or at www.aap.org

American Academy of Pediatrics. The Pediatrician’s Role in Promoting Health and Safety in Child Care. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2001. Available at: www.healthychildcare.org

Child Care Aware, National Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies (NACCRRA). Is this the right place for my child? 38 research-based indicators of quality child care. Available at: http://childcareaware.org/resources/printable-materials/

Child Care Aware, National Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies (NACCRRA). Quality child care matters for infants and toddlers. Available at: http://childcareaware.org/families/choosing-quality-child-care

Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies, local referral agencies that can assist families in finding quality, affordable programs. Available at: http://childcareaware.org/families/choosing-quality-child-care/selecting-a-child-care-program/

Head Start. Early childhood learning and knowledge center. Available at: http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/tta-system/health

Healthy Child Care America. Federally funded and housed at the AAP, this Web site has many resources for health and ECE professionals. Available at: www.healthychildcare.org

National Association for the Education of Young Children. Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC); 2009. Available at: www.naeyc.org/files/naeyc/file/positions/PSDAP.pdf

National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. Available at: www.nrckids.org

Zero to Three. Early Experiences Matter Policy Guide. Washington, DC: Zero to Three; 2009. Available at: https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/119-early-experiences-matter-policy-guide

Zero to Three. Matching Your Infant’s and Toddler’s Style to the Right Child Care Setting. Washington, DC: Zero to Three; 2001. Available at: https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/86-matching-your-infant-s-or-toddler-s-style-to-the-right-child-care-setting

American Academy of Pediatrics

early childhood education

quality rating and improvement system

Dr Donoghue updated the previous policy statement and revised that original document by adding references, updating the wording, and adding new sections based on updates from the field. The document went through several layers of review, and Dr Donoghue was responsible for responding to those comments.

This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication.

Policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the organizations or government agencies that they represent.

The guidance in this statement does not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

All policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics automatically expire 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed, revised, or retired at or before that time.

FUNDING: No external funding.

Elaine A. Donoghue, MD, FAAP

Jill Sells, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Beth DelConte, MD, FAAP

Elaine Donoghue, MD, FAAP

Marian Earls, MD, FAAP

Danette Glassy, MD, FAAP

Alan Mendelsohn, MD, FAAP

Terri McFadden, MD, FAAP

Seth Scholer, MD, FAAP

Jennifer Takagishi, MD, FAAP

Douglas Vanderbilt, MD, FAAP

P. Gail Williams, MD, FAAP

Claire Lerner, LCSW, Zero to Three

Barbara U. Hamilton, MA, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

David Willis, MD, FAAP, Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Lynette Fraga, PhD, Child Care Aware

Abbey Alkon, RN, PNP, PhD, National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners

Laurel Hoffmann, MD, AAP Section on Medical Students, Residents, and Fellows in Training

Charlotte O. Zia, MPH, CHES

Competing Interests

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Open access

- Published: 22 May 2021

Fostering socio-emotional learning through early childhood intervention

- Christina F. Mondi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1619-6389 1 ,

- Alison Giovanelli 2 &

- Arthur J. Reynolds 3

International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy volume 15 , Article number: 6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

32k Accesses

18 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Educators and researchers are increasingly interested in evaluating and promoting socio-emotional learning (SEL) beginning in early childhood (Newman & Dusunbury in 2015; Zigler & Trickett in American Psychologist 33(9):789–798 https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.33.9.789 , 1978). Decades of research have linked participation in high-quality early childhood education (ECE) programs (e.g., public prekindergarten, Head Start) to multidimensional wellbeing. ECE programs also have demonstrated potential to be implemented at large scales with strong financial returns on investment. However, relatively few studies have investigated the effects of ECE programs on SEL, particularly compared to smaller-scale, skills-based SEL interventions. Furthermore, among studies that have examined SEL, there is a general lack of consensus about how to define and measure SEL in applied settings. The present paper begins to address these gaps in several ways. First, it discusses conceptual and methodological issues related to developmentally and culturally sensitive assessment of young children’s socio-emotional functioning. Second, it reviews the empirical research literature on the impacts of three types of early childhood programs (general prekindergarten programs; multi-component prekindergarten programs; and universal skills-based interventions) on SEL. Finally, it highlights future directions for research and practice.

Fostering socio-emotional learning through early childhood programming

What are the best ways to assess the effectiveness of early childhood intervention programs? This question has been debated for decades, and the answer has tremendous implications for public policy. During the mid-twentieth century, many research studies primarily examined whether intervention participation led to improvements in children’s IQ scores. Some researchers, however, argued for a more multidimensional approach to assessing intervention outcomes. Edward Zigler, one of the architects of Head Start, notably proposed that the primary outcome of interest in early childhood interventions should be children’s “social competence” (Raver & Zigler, 1997 ; Zigler & Trickett, 1978 ). Interest in social competence grew in the second half of the twentieth century, with numerous studies indicating that socio-emotional and motivational variables exert significant impacts on wellbeing in childhood and beyond (Greenberg et al., 2003 ; Jones et al., 2015 ). By the turn of the twenty-first century, a national sample of teachers reported that they believed that the ability to regulate emotions and behaviors is the most important component of school readiness (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2000 ).

Today, educators and researchers continue to be interested in evaluating and promoting socio-emotional learning (SEL) starting in early childhood. Early childhood SEL skills develop rapidly, are uniquely malleable, and are strongly associated with later social, academic, cognitive, and health outcomes (Zins et al., 2007 ). Skills-based interventions that specifically target children’s SEL have been a major area of investigation (McClelland et al., 2017 ). However, relatively less is known about the impacts of large-scale early childhood education (ECE) programs on SEL, despite the potential of such programs to effect broad impacts. Furthermore, despite the growing enthusiasm surrounding the concept of SEL, many of the same methodological issues that Zigler and colleagues described in the 1970s still persist. Review of the literature reveals a lack of consensus among researchers and practitioners regarding how to define, evaluate, and promote SEL.

McCabe and Altamura ( 2011 ) previously reviewed the impact of a variety of preschool interventions on SEL, including both skills-based interventions and comprehensive classroom- and home-based programs. The authors reported that many programs were associated with short-term SEL benefits, but that there was a need for additional longitudinal research in this area. Notably, the authors did not explicate their review methodology or inclusion criteria, making it difficult to ascertain the representativeness and comprehensiveness of their findings. This limitation, combined with the publication of a number of studies since 2011, signal the need for an updated review of different intervention strategies for preschool-aged children.

The present paper reviews the most methodologically rigorous research that is available on the relationship between preschool intervention and SEL. We begin by discussing what the construct of SEL is (and is not)—a topic that that has been the subject of some debate and confusion in the literature. Having outlined a conceptual and methodological framework for SEL, we will then describe specific study aims and methods.

Socio-emotional competencies in early childhood

During the early 1990s, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) attempted to organize decades of empirical research on socio-emotional development into a socio-emotional learning (SEL) framework (Newman & Dusunbury, 2015 ). Since then, the CASEL framework has been widely used by researchers, practitioners, and policymakers alike, informing the development of federal and state state legislation and learning standards.

According to CASEL researchers, SEL is the process of learning to “integrate thinking, feeling, and behaving to achieve important life tasks” (Zins et al., 2007 , p. 194). SEL encompasses children’s emerging abilities to “form close and secure…relationships; experience, regulate, and express emotions in socially and culturally appropriate ways; and explore the environment and learn—all in the context of family, community, and culture” (Yates et al., 2008 , p. 2). CASEL’s SEL framework is grounded in research on typical and atypical socio-emotional development and highlights five core competency areas: (a) self-awareness; (b) self-management; (c) social awareness; (d) relationship skills; and (e) responsible decision-making (Collaborative for Social & Emotional Learning [CASEL], 2012 ; “Core SEL Competencies”, 2019 ; Weissberg et al., 2016 ). These competences are outlined in Table 1 .

Importantly, while CASEL’s five core competency areas are common across most cultures, specific aspects of adaptive SEL functioning may vary based on race/ethnicity, language, socioeconomic status, and other cultural factors. Cognitive, linguistic, and behavioral traits that are considered to be adaptive and desirable in non-majority culture communities may be perceived as problematic or even pathological by majority culture educators (Phillips, 1993 ; West-Olatunji et al., 2008 ). These perceptions may be partially attributed to educators’ own biases, and to disparities between the culture and structure of children’s home and school environments (Boykin, 1983 ; Han & Thomas, 2010 ; Ladson-Billings, 1995 ; McCarthy et al., 2006 ; Webb-Johnson, 2002 ). Thus, when assessing children’s SEL, researchers and educators should carefully consider the role that culture plays in shaping children’s behavior, and avoid conflating cultural behavioral differences with disorder.

Conceptual and measurement issues

Distinguishing sel from executive function.

SEL skills have often been referred to as “non-cognitive” skills in research and practice. Yet many researchers have argued that this designation is a misnomer, given that SEL skills are often grounded in skills related to cognition, learning, and memory. Among the most significant contributors to SEL are executive functioning (EF) skills, which include the cognitive processes necessary for planning, organizing, and problem-solving. Several studies have linked EF deficits to concurrent SEL deficits, and longitudinal work has indicated that EF skills in early childhood predict SEL competence later in life (e.g., Riggs et al., 2006 ). Thus, EF and SEL competencies, (including self-management, as identified by CASEL’s framework) can be conceptualized as distinct but related, and at times overlapping, constructs.

Distinguishing SEL from psychopathology

Psychologists increasingly agree that mental health is most accurately conceptualized on a continuum, ranging from clinically significant psychopathology to psychological wellbeing or flourishing (Keyes, 2002 ). Within this model, mental health or wellbeing is conceptualized not only as the absence of psychopathology symptoms, but as the presence of competencies that enable individuals to withstand adversity and to work towards positive outcomes. As Darling-Churchill and Lippman ( 2016 , p. 3) stated: “Problems and strengths do not fall neatly on a single continuum, and the absence of problems does not guarantee the presence of competencies; thus, it is important to measure both.” From this perspective, it is imperative that researchers and practitioners avoid conflating emergent SEL deficits with psychopathology (Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016 ).

Children exhibiting emergent SEL deficits may or may not have comorbid psychiatric disorders. Children with diagnosable psychopathology must exhibit symptoms that coalesce into specific patterns and that are associated with significant functional impairment. The latter group would likely benefit from clinical treatment. Meanwhile, many children do not currently meet diagnostic criteria for a disorder, but exhibit emergent deficits in SEL skills relative to same-age peers (Jones et al., 2002 ; Wille et al., 2008 ). A multitude of factors may contribute to lagged SEL, including early deprivation or trauma, inconsistent caregiving, and cultural differences in socio-emotional expression. Children with emergent SEL deficits would likely benefit from broader-based interventions that provide opportunities for them to interact with high-quality caregivers, establish peer relationships, and practice SEL skills in the environments that they are already in (e.g., early care and education settings).

Emergent SEL deficits are distinct from clinical disorder; however, it is important to acknowledge the demonstrated link between early SEL deficits and long-term risk for the development of psychopathology. This link reflects the phenomenon of heterotypic continuity , in which an early behavior predicts the subsequent emergence of a different behavior in the same individual (Rutter et al., 2006 ). The concept of developmental cascades has been invoked as a potential mechanism for heterotypic continuity; in this case, an individual’s early SEL competencies interact with other individual and environmental factors (e.g., genetic, family, school) over time, influencing his or her risk of developing psychopathology (Burke et al., 2005 ). For example, a child who is lagging in SEL may have negative interactions with caregivers and peers and fall behind academically. These experiences may, in turn, increase the child’s probability of academic, psychological, and other difficulties over time. Conversely, a child who exhibits developmentally appropriate SEL will likely experience more social and academic success, which can lay foundations for lifelong wellbeing.

Other measurement issues

As noted above, it is critical that researchers utilize measures that assess children’s SEL skills (as distinguished from EF skills or psychopathology symptoms).

Several additional issues merit consideration when assessing SEL in early childhood (Committee on Developmental Outcomes, 2008 ; Darling-Churchill & Lippman, 2016 ; Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016 ). Measurement should ideally occur across multiple time-points, as longitudinal assessment allows for stronger inference of causal relationships. Collecting repeated measurements over time will also allow researchers to observe trajectories of socio-emotional development over time. Finally, collecting data from multiple informants is considered ideal in order to gain more comprehensive, reliable pictures of children’s functioning. Integrating reports from different informants, who may perceive children’s behaviors differently or observe different behaviors in different settings (e.g., home versus school), can be challenging; however, several methodological solutions to this problem have been proposed (e.g., Offord et al., 1996 ).

Present review

The present paper reviews the current state of the literature on SEL interventions for preschool-aged children. This review makes several unique contributions. First, whereas previous reviews have primarily focused on skills-based SEL interventions, this review compares and contrasts the effects of three types of early childhood interventions on SEL: (a) general prekindergarten programs; (b) multi-component prekindergarten programs; and (c) skills-based interventions. This review specifically focuses on universal programs in each of the three categories (e.g., programs that are not specifically targeted to children with emergent SEL deficits or psychopathology). Second, whereas several previous reviews have examined the effects of early intervention on child psychopathology (e.g., internalizing, externalizing symptoms), the current review examines SEL outcomes, defined as children’s acquisition of developmentally appropriate social and emotional skills. Finally, rather than reviewing the entire literature, this review focuses on the most methodologically rigorous (e.g., peer-reviewed, longitudinal) extant research. Given these combined foci, the present review offers a thorough, up-to-date overview of the effects of different types of early childhood interventions on young children’s SEL.

Notably, while we believe that it is imperative to evaluate the strength of programs’ evidence bases using specific uniform criteria, our review reveals variable methodology and construct validity across individual studies, making it challenging to assess program efficacy in a reliable or systematic way. As such, we emphasize that the purpose of this review is not to make statements about the efficacy of individual programs, but rather to describe programs that are most promising and to identify knowledge gaps for future research to investigate.

Having reviewed key conceptual and methodological issues, we will now describe our review of universal interventions for preschool-aged children. We conducted searches in Web of Science, PsycInfo, Google Scholar, and PubMed. Numerous search terms were employed, including ones referencing socio-emotional skills (e.g., “socio-emotional”, “emotion regulation”, “non-cognitive”, “prosocial”), early childhood and ECE programming (e.g., “preschool,” “Head Start”), and commonly used SEL measures (e.g., “ Behavior Assessment System ”, “Conners”). Backwards and forward searches were conducted on landmark and highly cited articles.

Studies had to meet six inclusion criteria to be included in the present review. The purpose of these criteria was to identify the most methodologically rigorous studies on modern universal interventions and SEL. (1) studies had to be published in English in peer-reviewed journals by December 31, 2020. (2) Only studies that investigated prekindergarten interventions implemented in 1990 or later were included. (3) Interventions had to be universal (e.g., not specifically targeted to children with baseline SEL deficits or psychopathology) and delivered by laypeople (e.g., not researchers). (4) Critically, given that the focus of the present paper is the relations between intervention and SEL included, studies had to measure one or more SEL skills as previously defined. Studies were not included if they solely measured psychopathology outcomes (e.g., externalizing or internalizing symptoms, problem behaviors) or EF outcomes. (5) Studies had to assess children’s SEL skills at a minimum of two time-points, as skill development over the course of intervention can only be examined within longitudinal research designs. (6) Studies had to include a comparison or control group.

The first and second authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of identified studies to determine whether they met inclusion criteria. During this review process, both authors also determined which intervention category applied to each study. General public prekindergarten programs were defined as publicly funded programs administered by state and local agencies. Multi-component ECE programs were defined as programs which provide multiple academic, family and social support services (e.g., Head Start, the Child–Parent Center (CPC) Program, The High/Scope Perry Preschool Project), typically in center-based settings. Skills-based SEL interventions were defined as discrete interventions aimed at enhancing children’s SEL via direct skills instruction for children and/or their ECE caregivers (e.g., Al’s Pals, The Incredible Years). In cases of disagreement, both authors reviewed and discussed until consensus was reached. Overall, based on these criteria, the following studies are included in the present review: (a) one empirical study of a general public prekindergarten program; (b) three empirical studies of multi-component ECE interventions; (c) 23 empirical studies of skills-based SEL interventions; (d) three systematic reviews or meta-analyses of multi-component ECE interventions; and (e) five systematic reviews or meta-analyses of SEL skills-based interventions. See Tables 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 and 6 for details on these studies, including sample characteristics.

General public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs (Tables 2 , 3 , 4 )

General public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs (e.g., Head Start, the CPC program) are comprehensive ECE interventions, and stand in contrast to skills-based interventions which primarily target SEL. Nonetheless, there are several important distinctions between general public prekindergarten programs and multi-component ECE programs (e.g., Head Start, the CPC Program). There is often significant variability in general prekindergarten models and populations served, both across and within public school districts in the United States (Phillips et al., 2017 ). Meanwhile, multi-component ECE programs typically incorporate similar program elements and serve comparable populations across sites. Multi-component programs often operate in center-based settings, and typically provide a wider range of support services for children and families than general public prekindergarten programs.

Despite the differences between general public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs, we present our findings for both program types simultaneously below. This is because, based on our review and to our knowledge, only one peer-reviewed study (Weiland & Yoshikawa, 2013 ) has examined the effects of general public prekindergarten participation on SEL. A small number of studies have examined the relations between public prekindergarten participation and emotional and behavioral problems in childhood (e.g., internalizing and externalizing symptoms) (e.g., Gormley et al., 2011 ; Magnuson et al., 2007 ); however, as previously discussed, the focus of this review is on the relationship between intervention and SEL, not psychopathology symptoms. The lack of research on SEL in the context of public prekindergarten is a major gap that we will discuss in more depth later in this paper. In the interim, we present our findings on both types of non-SEL-skills-based interventions (general public prekindergarten and multi-component ECE programs).

Meta-analyses and reviews (Table 3 )

Our review did not uncover any peer-reviewed meta-analyses or systematic reviews of the relations between public prekindergarten programming and SEL. On the contrary, several peer-reviewed meta-analyses and systematic reviews have investigated the effects of multi-component ECE programs on SEL. The authors of these publications have typically constructed outcome variables using a combination of measures assessing SEL skills, mental health symptoms, and outcomes from other domains that are related to socio-emotional functioning (e.g., special education placement, criminal justice system involvement). These publications will be briefly reviewed herein.

Nelson et. al. ( 2003 ) published one of the first meta-analyses examining preschool prevention programs for low-income children and families. Inclusion criteria included (1) presence of a prospective research design, (2) control or comparison group, and (3) at least one follow-up assessment in elementary school or beyond. In all, 34 qualifying interventions were identified. The authors reported that preschool programs exerted small to moderate effects on socio-emotional functioning in both the short-term (Kindergarten through eighth grade; d = 0.27) and long-term (high school and beyond; d = 0.33). Age at program entry was not related to program impacts; however, higher program dosage was linked to stronger effects on socio-emotional functioning. Results also indicated that African American children were more likely to participate in the most intensive interventions, and that programs that predominately served the latter group were associated with the greatest socio-emotional benefits.

Several years later, Camilli et. al. ( 2010 ) conducted another meta-analysis examining the effects of ECE participation on child outcomes. To be included in the meta-analysis, interventions had to: (1) be center-based, (2) provide direct educational services to children, with a strong focus on cognitive and/or language development; (3) take place for at least 10 h per week for two months, and (4) serve the general population. Studies also had to have a comparison group. The authors identified 123 studies spanning five decades that met inclusion criteria; however, only 43 of these examined socio-emotional outcomes. The authors combined “social/emotional and anti-social outcome[s]” for analysis, including children’s self-esteem, school adjustment, educational goals, aggression, and antisocial behaviors (p. 592). Results indicated that participation in ECE programs was associated with modest positive effects on children’s social skills and school progress (unweighted mean ES = 0.16 for treatment versus control group analyses). These treatment effects were maintained over the course of longitudinal follow-up. Two instructional practices were positively correlated with socio-emotional gains among treatment group members: teacher-directed instruction and small-group learning.

D’Onise et. al. ( 2014 ) conducted a systematic literature review examining the effects of center-based preschool programs on health outcomes. They identified 13 studies that examined the effects of program participation on “social competence” between grades one and 11. Several of these studies utilized measures that assessed both positive social behaviors (e.g., cooperation, self-control) and problem behaviors (e.g., externalizing and internalizing problems, hyperactivity). D’Onise and colleagues reported that eight of the 13 studies identified beneficial effects of preschool participation on social competence, broadly construed, whereas six found no significant effects. Program duration and quality were not significantly associated with impacts on socio-emotional functioning.

Studies not included in meta-analyses and reviews (Tables 2 and 4 )

Several additional studies have been published since the aforementioned meta-analyses and reviews on the relationship between early intervention and SEL. This notably includes the only peer-reviewed study on the relations between public prekindergarten participation and SEL that our review uncovered: Weiland and Yoshikawa’s ( 2013 ) investigation of the Boston Public Schools prekindergarten program (Table 1 ). Boston Public School preschoolers were compared to control group members who had a variety of experiences during the prekindergarten year, ranging from familial care to center-based preschool programming. All participants completed performance-based and observational assessments of SEL across the preschool year. Results indicated that public prekindergarten participants exhibited significantly greater growth in emotion regulation and inhibitory control over time than the control group.

Several recent studies have also investigated the relations between multi-component ECE program participation and SEL. For example, Brown and Sax ( 2013 ) reported on the SEL of preschoolers attending an arts-integrated Head Start site, the Settlement Music School’s Kaleidoscope Preschool Arts Enrichment program (“Kaleidoscope”). The Kaleidoscope site combined traditional early learning strategies with comprehensive arts programming (e.g., visual art classes, dance and creative movement, music). This programming drew from varied cultural traditions, and was designed to support children’s creativity and emotional expression. Results indicated that Kaleidoscope participants exhibited significantly greater growth in both positive and negative emotion regulation over the course of the school year, compared to children attending a traditional Head Start site. These results underscore the potential value of multi-component programming (including arts enrichment) in promoting young children’s SEL.

Several years later, Reynolds et. al. ( 2016 ) published an evaluation study examining the effects of the Child–Parent Center (CPC) program on SEL. The CPC program provides comprehensive, center-based educational and family support services to low-income children between Preschool and third grade. Reynolds and colleagues’ study utilized a quasi-experimental, matched-group cohort design which included 1724 children who attended CPC preschool, and a comparison group of 906 children who attended alternative prekindergarten programming. Teachers rated children’s SEL across the preschool year using the observation-based Teaching Strategies Gold Assessment System (TSGOLD). Overall, teachers rated CPC participants as having significantly higher overall SEL (including self-regulation, sustaining positive relationships, and participating constructively in group situations) at the end of preschool than comparison group members (standardized mean difference = 0.44). These results should be interpreted in the context of the non-randomized design and reliance on teacher ratings; however, they suggest that participation in public school-based ECE programs may enhance the SEL of low-income children.

Richardson et. al. ( 2017 ) also examined SEL in the context of the CPC program. Their study’s intervention group included 1289 low-income children who attended CPC preschool in Chicago. The comparison group included 591 children who attended public preschool programs at matched school sites. Teachers rated children’s SEL skills at three time-points throughout the preschool year using TSGOLD. Results indicated that teachers rated CPC participants as having significantly higher SEL school readiness than control group members. Positive impacts were detected for children who attended both the full- and half-day CPC programs, and for children from free-lunch eligible and Spanish-speaking families.

Skills-based SEL interventions

Discrete skills-based interventions to augment SEL are appealing in that they can be delivered by a teacher in the school setting, and generally require a finite investment of time, training, and resources. These types of interventions often target student competencies through a combination of indirect methods such as teacher skills augmented through professional development and strategies to alter classroom quality or parent training, and direct methods like didactic teaching and practice of socio-emotional and self-regulation skills.

It should be noted that many programs that may come to mind when discussing interventions focusing on social skills within preschool programs use measures of psychopathology outcomes (e.g., emotional or behavioral disorders; symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder or clinically significant conduct problems) as proxies for “socio-emotional competencies” and as such, were not included in this review for reasons of construct validity discussed above. Several studies were also excluded from the present review due to lacking a control group, having a cross-sectional design, or taking place before 1990. Few studies collected long-term follow-up data, and therefore in many cases sustained effects of skills-based interventions are unknown. Every effort was made to review a representative body of evidence for the programs described below; however, for several programs, we were only able to identify one empirical study that met our inclusion criteria.

Reviews of skills-based SEL interventions (Table 5 )

While there have been several reviews of programs designed to reduce challenging and increasing prosocial behaviors, only two comprehensive, peer-reviewed systematic reviews focused on skills-based SEL programs for young children had been published by our cutoff (Barton et al., 2014 ; Joseph & Strain, 2003 ). The scope of these reviews is somewhat broader than that of the present paper, as both included studies of interventions across the elementary years in addition to those targeting preschoolers, as well as interventions that focused primary on parents and parenting practices. However, both reviews did evaluate the evidence base for many programs relevant to the current review—namely, universal SEL skills-based programs designed to be implemented by teachers in preschool settings.

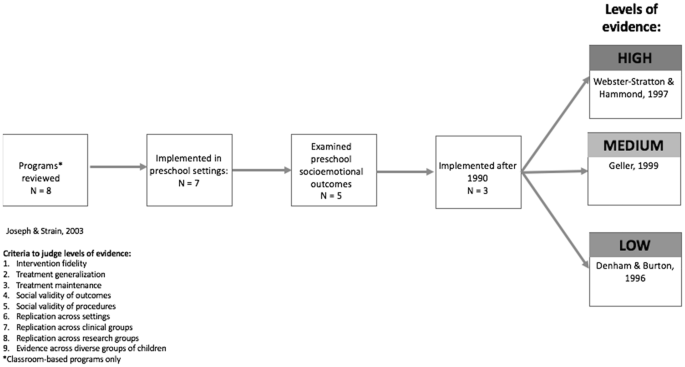

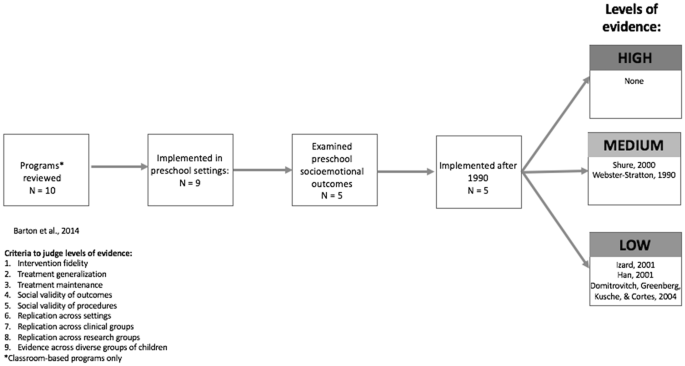

Both Joseph and Strain ( 2003 ; Fig. 1 ) and Barton et. al. ( 2014 ; Fig. 2 ) have published reviews of socio-emotional curricula. In both reviews, studies had to meet the following criteria: (a) intervention targeted socio-emotional and behavioral competencies, (b) intervention targeted children from birth to age five, (c) intervention had a published manual, and (d) findings were published in a peer-reviewed journal article. Figures 1 and 2 summarize the number of studies that the authors identified, and the criteria that they used to judge program efficacy and implementation success. In both studies, programs were rated as having high, medium, or low levels of empirical evidence.

Summary of Joseph and Strain’s ( 2003 ) review of skills-based SEL interventions

Summary of Barton et. al.’s ( 2014 ) review of skills-based SEL interventions

The aforementioned reviews have served as a valuable and informative starting point for the present study’s investigation of the current state of the research on skills-based SEL programs; however, the criteria for choosing studies in the present paper differed considerably. Specifically, several of the interventions evaluated in Joseph and Strain’s ( 2003 ) and Barton et. al. ( 2014 ) reviews were last evaluated prior to 1990; were primarily focused on mental health, psychopathology, or antisocial behavior as opposed to socio-emotional functioning; or were evaluated in kindergartners or older elementary school aged children. Overall, most studies did not evaluate SEL using independent observers or multiple raters, and long-term follow-up was rare.

Meanwhile, two recently published meta-analyses investigated the effects of skills-based SEL interventions on young children’s SEL (Luo et al., 2020 ; Murano et al., 2020 ). Luo et. al. ( 2020 ) meta-analysis investigated the impacts of classroom-wide social-emotional interventions (e.g., universal, skills-based interventions) on preschoolers’ social, emotional, and behavioral functioning. They identified 30 studies which reported sufficient data to calculate effect sizes, and which examined intervention effects on social competence. Meta-analytic results indicated that classroom-wide interventions had moderate positive effects on social competence ( g = 0.42, z = 5.77, p < 0.001, k = 34), though there was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes across studies. Follow-up analyses indicated that interventions that incorporated family-focused programming had greater impacts on social competence than those that did not include family members. Meanwhile, in meta-analysis of 12 studies that examined emotional competence, Luo and colleagues reported that classroom-wide interventions had moderate positive effects on emotional competence ( g = 0.33, z = 2.85, p = 0.004, k = 14). Interestingly, univariate moderator analyses did not identify linkages between most intervention variables (including dosage) and children’s SEL outcomes.

In another recent meta-analysis, Murano et. al. ( 2020 ) examined the effects of both universal and targeted skills-based SEL interventions on preschoolers’ SEL skills and problem behaviors. They identified 48 empirical studies which met their inclusion criteria, and reported that both universal and targeted interventions had moderate effects on children’s social and emotional skills ( g = 0.34 and g = 0.44, respectively). Similar to the findings reported by Luo et. al. ( 2020 ), Murano and colleagues indicated that there was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes across studies, and that 83% of this heterogeneity was attributable to the specific intervention implemented. They also reported that interventions that included family members had stronger impacts on children’s SEL than those that did not include family members—also in keeping with Luo and colleagues’ results.

Taken together, Luo et. al. ( 2020 ) and Murano et. al. ( 2020 ) meta-analyses support the effectiveness of skills-based SEL interventions in promoting young children’s SEL. Their results indicate that both universal and targeted interventions can be beneficial, and that interventions that operate at multiple social-ecological levels tend to be most effective. Building on these findings, we will now summarize the empirical evidence bases for several SEL skills-based interventions in depth. Our intention is to describe several high-quality interventions, as a way of highlighting exemplary research as well as conceptual and methodological issues for future researchers to address.

Child and teacher-focused skills-based interventions

This group of interventions provides a teacher-training component combined with a child curriculum consisting of discrete, manualized lessons on SEL topics. These curricula often take the form of teaching didactic SEL skills instruction to children, typically in group-based settings in the context of Head Start and other publicly funded preschool programs. Due to space constraints, three exemplar programs will be discussed in detail below. Table 6 describes additional skills-based interventions meeting our criteria.

One child and teacher-focused skills-based intervention is the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) curriculum (Domitrovich et al., 2004 ). PATHS is one of the most extensively evaluated SEL programs for young children (Arda & Ocak, 2012 ; Domitrovich et al., 2007 ; Hamre et al., 2012 ; Hughes & Cline, 2015 ; Stefan & Miclea, 2012 ). The developers describe PATHS as based on the Affective–Behavioral–Cognitive–Dynamic (ABCD) model of development (Greenberg & Kusche, 1993 ), which “suggests that emotional development is an important precursor to other cognitive and language skills and that the successful development of emotion knowledge and regulation is foundational to the development of the broad spectrum of social competencies described previously as central to school success (Hamre et al., 2012 , p. 811).” Although implementation appears to vary slightly by site and evaluation team, the curriculum generally consists of several dozen lessons, delivered once per week by Head Start preschool teachers during “circle time,” and focuses on emotion knowledge, regulation, prosocial skills, and problem-solving. The intervention also often includes extension activities that were intended to generalize the weekly lessons and to foster an environment that would encourage children’s use of socio-emotional skills. Teachers are generally provided with support, ranging from access to a website with examples of teachers implementing PATHS to ongoing site visits and consultation from designated PATHS coordinators. Implementation fidelity has also been monitored in a variety of ways, including via the site visits or through submission and coding of videos. Studies utilized a range of tools for assessing outcomes, including direct assessment, observation, and parent and teacher reports of emotion knowledge, prosocial and problem behavior, and attentional skills. Evaluators generally reported medium effect sizes, ranging from 0.20 to 0.50, across socio-emotional and behavioral domains. However, as in many of the studies included here, parents and teachers in all of the evaluations were not blind to the intervention condition, which could have biased ratings.

Stefan and Miclea ( 2012 ) evaluated the implementation of a program that they called “Fast Track,” in which PATHS was the SEL intervention, in a preschool population in Romania. In addition to teacher training, they utilized a parent component, which was delivered via group and individual training sessions, and focused on positive discipline strategies and increasing parents’ knowledge of how to support their child’s social and emotional development. The authors found medium to large intervention effects for all outcomes. Children in medium and high-risk subgroups appeared to benefit more from the intervention even when controlling for baseline differences on tasks. This study is distinguished by the fact that the authors conducted follow-up assessments three months after the post-intervention data was collected, and found that intervention effects were maintained for both social and emotional competencies. However, there was no direct observation of child classroom behaviors, and as teacher, parent, and child components were delivered concurrently, mechanisms of effects are unknown.

Head Start REDI

Another Head Start-based program, Head Start Research-based, Developmentally Informed (REDI), which uses PATHs to target socio-emotional skills in the context of a broader program intended to enhance both social competence and literacy in preschoolers, has been the subject of several studies with long-term follow-up (Bierman et al., 2014 ; Bierman, Domitrovich, et al., 2008 ; Bierman, Nix, et al., 2008 ; Nix et al., 2016 ). Initial investigations of the REDI program on preschoolers found small to medium effect sizes for social competence and executive functioning outcomes (Bierman, Domitrovich, et al., 2008 ; Bierman, Nix, et al., 2008 ). Results of a 1-year follow-up on children in Head Start REDI as preschoolers compared to those who had attended “usual practice” Head Start indicated sustained direct effects for social problem-solving ( d = 0.40) and parent and teacher-rated aggressive behaviors ( d = − 0.20 and d = − 0.25, respectively) for kindergarten children who were in REDI as preschoolers, with effect sizes at the 1-year follow-up equal to or larger than those at the end of the intervention year. Teacher-rated social competence was also significantly higher for intervention students ( d = 0.26), but only for those in kindergarten at schools where overall student achievement was low (Bierman et al., 2014 ). Several years later, Bierman et. al. ( 2017 ) combined the samples of the two previous randomized trials to investigate the sustained effects of REDI, three years post-intervention. Intervention group participants received either the REDI Classroom Program (REDI-C), or both REDI-C and the REDI-Parent home visiting program (REDI-P). Comparison group members attended standard Head Start programming. Results indicated that REDI-C graduates exhibited significantly higher classroom participation ( d = ~ 0.25), social competence ( d = ~ 0.25), and student–teacher relationships ( d = ~ 0.4) in second grade relative to the comparison group. Children who had received both REDI-C and REDI-P exhibited higher perceived social competence ( d = ~ 0.75) compared to children who had only received REDI-C.

Taken together, these studies provide strong evidence that the PATHS curriculum, when implemented with fidelity, can effectively increase the SEL competencies of preschoolers both within the context of the literacy-promoting REDI intervention and when used independently.

Kindness Curriculum

The Kindness Curriculum, a mindfulness-based intervention designed to increase empathy, prosocial behavior, and self-regulation in preschoolers, has been evaluated in two empirical studies meeting our criteria (Flook et al., 2015 ; Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2016 ). In both evaluations, the 10-h training was delivered to preschoolers over the course of 12 weeks via stories, music, and movement. The program emphasizes kindness, emotion regulation, and attentional capacity. Flook et. al. ( 2015 ), in the initial study, found via teacher ratings and direct assessment that the intervention group showed greater improvements across domains of social competence ( d = 0.26–0.29) compared to the control group, in addition to significant effects for cognitive flexibility ( d = 0.43) and delay of gratification ( d = 0.23–0.37). Children who were initially lower in social competence and executive functioning skills evinced larger gains in social competence.

Poehlmann-Tynan et. al. ( 2016 ) also found promising effects when investigating this curriculum in economically disadvantaged preschoolers and assessed prosocial behavior (e.g., empathy and compassion), self-regulation, and executive functioning via direct assessment and observation. They found that the children in the KC intervention group increased their capacity for self-regulation and attention (partial η 2 = 0.26–0.33) relative to the control group; however, unlike Flook, they found no changes in observer-rated or directly assessed prosocial behaviors. The positive effects, however, persisted at a 3-month follow-up assessment. It is important to note that the curricula were delivered by “experienced mindfulness instructors.” The evidence base for effectiveness and scalability of the KC intervention in a preschool setting would be strengthened by an investigation of the program delivered by classroom teachers.

Skills-based interventions incorporating parent involvement

This group of interventions supplements skills-based interventions for children and/or teachers with parent involvement initiatives. Due to space constraints, three exemplar programs will be discussed in detail below. Table 6 describes additional skills-based interventions.

The RECAP intervention

Han et. al. ( 2005 ) have published the only study to date evaluating the Reaching Educators, Children, and Parents (RECAP) program in preschoolers. The study aimed to enhance preschoolers’ problem solving and social skills and also attempted to incorporate a parenting component. The program included curricular and behavior management components, provided teachers with weekly trainings and ongoing consultations, and offered a bi-weekly parent group. Study participants were primarily low-income 4 to 5-year-old children in public prekindergarten classrooms. The evaluators collected parent- and teacher-report of internalizing and externalizing behaviors and social skills. They found no changes in children’s parent-rated functioning over time. However, they did find significant improvements for intervention group participants on teacher-rated total social skills ( F [1, 144] = 5.73, p < 0.05), cooperation ( F [1, 144] = 3.99, p < 0.05) and assertion ( F [1, 144] = 7.12, p < 0.01). Notably, parent group attendance was extremely low, and as such, the effectiveness of the parent component of this intervention was not able to be evaluated. Other limitations included the self-report nature of the outcome measures, and baseline group differences in teacher-reported levels of problem behaviors and skills, and on family income.

Making choices and strong families (Conner & Fraser, 2011 )

The Making Choices program is one of the few studies of an SEL skills-based curriculum for preschoolers that included a successfully implemented parenting component. The SEL-focused component, Making Choices, is a manualized program with theoretical bases in social information processing, designed for preschool-aged children. The program was delivered twice weekly for 14 weeks with the aim of strengthening social information processing, emotion regulation skills, and prosocial interactions with peers. The parent training component, Strong Families, had distinct but complementary goals, including increasing positive parent–child interaction patterns and decreasing coercion. The study sample was drawn from a group of part-day preschool centers, and the comparison group received typical Head Start services. Investigators directly assessed child-level competencies (e.g., academic competence, achievement motivation, social competence, peer acceptance, depression/anxiety and aggression/hostility) and family and child functioning. Results revealed significant effects for all child competencies ( F [20, 46] = 3.05, p < 0.001; r 2 = 0.35), with higher gain scores among intervention group participants, as well as positive changes in caregiver behaviors ( F [10, 56] = 6.88, p < 0.001; r 2 = 0.36). While these outcomes are promising, the sample sizes are quite small, and about 35% of eligible families moved or otherwise became ineligible before assignment to a treatment group. No follow-up or replication studies in preschoolers have been conducted to date, and as the interventions were delivered together, it is unclear if one or both was driving effects.

Incredible Years (IY)

The Incredible Years program was originally designed as a treatment for children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder diagnoses (Webster-Stratton, 1990 ), with theoretical bases in social learning theory and the effects of adult–child interaction processes in child behavior. The program has been adapted for use with several age groups and populations, including as a classroom-based prevention program aiming to augment socio-emotional skills and decrease problem behaviors in preschoolers. Of particular interest to the present review are the IY Teacher Classroom Management Training (TCM), the IY Child Program: Dinosaur Classroom Curriculum, and the IY Parent Program used in conjunction with the teacher or child programs. The IY programs, implemented as universal prevention programs in preschool-aged children, have been evaluated by Webster-Stratton and colleagues (Webster-Stratton, 1998 ; Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2004 ; Webster-Stratton et al., 2001 , 2008 ). Several independent evaluations of IY programs have also been conducted; however, many specifically evaluated children with high levels of disruptive or oppositional behaviors in the preschool setting (e.g., Baker-Henningham et al., 2012 ), did not utilize a control group (e.g., Shernoff & Kratochwill, 2007 ), or did not measure SEL outcomes (e.g., Williford & Shelton, 2008 ). As such, they did not meet our inclusion criteria.

Webster-Stratton et. al. ( 2001 ) evaluated IY TCM program in combination with the Parent Training as a universal prevention program in Head Start. The intervention group parents and teachers participated in the IY programs, and the control group received usual practice Head Start services. The teacher training consisted of 36 h of training on classroom management, child development, and promotion of prosocial and reduction of antisocial behaviors. The parent training had similar content, adapted for the home context and focused on reducing coercive discipline and increasing positive parenting practices. Teachers and parents in the intervention group evinced more positive practices, while children engaged in more prosocial behavior and were rated as more socially competent. Specifically, 71% of intervention group children rated as having problems with social competence at baseline fell in the normative range at the end of school, compared to 36.6% of the control group children initially rated as lower in social competence ( χ 2 [1, 26] = 4.12, p < 0.04).

Webster-Stratton and colleagues have also evaluated the IY TCM program in combination with the Dinosaur School curriculum in Head Start settings (Webster-Stratton et al., 2008 ). Children received 30 bi-weekly lessons promoting socio-emotional skills, problem-solving, self-regulation, and school behavior over the course of a year, communicated via vignettes, small-group activities, puppets, and games. Teachers participated in 28 h of workshops focused on classroom management and promotion of socio-emotional competence, spread out over four months. A research staff-member led lessons alongside the classroom teacher to ensure implementation fidelity. Outcomes were measured via classroom observations, as well as direct assessment of competencies such as problem-solving skills and emotion knowledge. The authors reported that teachers in the intervention were more likely to use teaching strategies to promote SEL (e.g., teaching prosocial behavior, problem-solving, shaping peer play, encouraging feelings language, and promoting social competence) in intervention group teachers ( d = 0.96). The intervention was also associated with higher levels of teacher-reported child social competence and self-regulation (effect sizes not reported), particularly for students with low levels at baseline, as well as improvements in problem-solving ( η 2 = 0.41) and feelings knowledge ( η 2 = 0.14).

Overall, the evidence base for the Incredible Years intervention is encouraging; however, evaluation methodology has been inconsistent and further investigation is needed to determine efficacy of the program as a universal prevention strategy for preschool-aged children.

Teacher-focused skills-based interventions

This group of interventions provides training and other forms of professional development to teachers, with the aim of improving teacher–child interactions and children’s socio-emotional functioning.

Pyramid Model

The Pyramid Model for Promoting Young Children’s Socio-Emotional Competence (the “Pyramid Model”; PM) is a professional development intervention that includes research-informed practices for promoting healthy socio-emotional development and high-quality relationships between caregivers and children. PM practices include universal strategies for teachers to promote family engagement and children’s peer social skills, as well as individualized interventions strategies for children exhibiting challenging behaviors. These practices are taught through multi-day workshops and implementation guides. Teachers also receive classroom materials (e.g., puppets, books) for implementing the practices.

Hemmeter et. al. ( 2016 ) conducted a cluster-randomized controlled potential efficacy trial to evaluate the effects of classroom-wide implementation of PM on teacher practices and child outcomes. Teachers in the intervention group participated in the initial PM workshops, and subsequently received weekly individualized coaching, which included in-classroom observation. Results indicated that children whose teachers participated in PM had higher teacher-rated social skills at post-test than children whose teachers did not participate in PM ( d = 0.43). These results are promising, but should be interpreted with caution given the study’s reliance on teacher ratings of children’s social skills.

Foundations of Learning (FOL)

Foundations of Learning is a professional development intervention that combines teacher training and mental health consultation. FOL teachers participate in workshops on proactively supporting positive behavior and managing challenging behaviors in the classroom, and on personal stress management. They also receive weekly classroom-level mental health consultation, and individualized mental health consultation as needed for children exhibiting persistent challenging behaviors. FOL’s teacher training component is adapted from the Incredible Years curriculum; the intervention is also based on the previously discussed, smaller-scale Chicago School Readiness Project (CSPR) intervention.

Morris et. al. ( 2013 ) conducted a cluster-randomized controlled study to evaluate the effects of FOL on preschool teacher practices and child outcomes. Results revealed positive impacts on teachers’ ability to manage challenging behaviors and promote a positive emotional climate in the classroom. At the child outcome level, results indicated that children whose teachers participated in FOL exhibited less problem behaviors (e.g., peer and teacher conflict, as rated by trained observer) than children whose teachers did not participate in FOL. However, no significant effects on either observer- or teacher-rated positive social behavior (e.g., communication, sociability, compliance) were detected between groups. Positive intervention effects on children’s approaches to learning (e.g., self-control, focus, and participation in classroom activities) were detected at the trending level ( p < 0.10).

Jensen et. al. ( 2017 ) evaluated the VIDA (a Danish acronym for Knowledge-based efforts for socially disadvantaged children in daycare) intervention, which aims to augment socio-emotional functioning in preschool children by altering their social context. The primary mode of change is via teacher training to improve the preschool environment. Intervention teachers attended 17 full days of training over the course of 2 years, gaining theoretical knowledge about child development and the bioecological system, encouraging reflection, enhancing communication with students, and requiring teachers to use the training to design their own activities focused on socio-emotional skills (e.g., improving friendships, managing conflict). Jensen et. al. ( 2017 ) explain:

“The initial step of the teachers’ learning process takes place as a top-down process that presents participants with predefined topics [...] Through reflection, everyday experiences are related to the research-based knowledge and the teaches are using this to change their practice. The process transforms what was initially top-down, course-based theoretical knowledge into bottom-up, practice-oriented teacher learning and innovation” (p. 28).

Teacher ratings revealed a trending effect of the intervention on prosocial behavior. Further evaluation of the program is warranted, and results may not be generalizable due to the high dosage of the program. It is also unclear whether students retained the same teacher over the course of the intervention, which could be an important confounding factor. Finally, conclusions would be strengthened by measurement of SEL outcomes via more diverse tools, as the only outcome measure in the present study was teacher-reported.

Comparing program types

General public prekindergarten programs.

Access to public prekindergarten programs has expanded dramatically in the United States over the last several decades, with approximately one-third of 4-year-old children enrolled in state-funded programs in 2017 (National Institute for Early Education Research [NIEER], 2018 ). These programs have historically focused on enhancing children’s pre-academic skills (e.g., language, numeracy), but have also increasingly targeted SEL.

Participation in public prekindergarten may enhance SEL by several mechanisms. For example, high-quality teacher–child relationships have been linked to improvements in children’s SEL (Merritt et al., 2012 ). Prekindergarten participation also provides children with consistent opportunities for socialization with peers and social skill practice. Finally, improvements in children’s academic and cognitive skills at the individual and classroom levels may also contribute to improvements in SEL over time through spillover effects. For most children, this may be sufficient, but it is important to evaluate whether public prekindergarten programs can exert significant and sufficient benefits on children’s SEL, or whether more targeted SEL services are needed.