Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Gathering and Analyzing Qualitative Data

Gathering and analyzing qualitative data.

As the role of clinician researchers expands beyond the bedside, it is important to consider the possibilities of inquiry beyond the quantitative approach. In contrast to the quantitative approach, qualitative methodology is highly inductive and relies on the background and interpretation of the researcher to derive meaning from the gathering and analytic processes central to qualitative inquiry.

Chapter 4: Learning Objectives

As you explore the research opportunities central to your interests to consider whether qualitative component would enrich your work, you’ll be able to:

- Define what qualitative research is

- Compare qualitative and quantitative approaches

- Describe the process of creating themes from recurring ideas gleaned from narrative interviews

What Is Qualitative Research?

Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of numerical data from a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this method is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in fields such as respiratory care and other clinical fields, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques, such as grounded theory, thematic analysis, critical discourse analysis, or interpretative phenomenological analysis. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008). They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To address this question, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This method is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, and that female undergraduate students are not substantially more talkative than male undergraduate students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And quantitative research is not very good at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this depth is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973) .

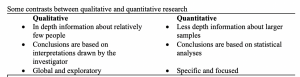

Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this detail. The table below lists some contrasts between qualitative and quantitative research

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

Data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, participant observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews. Interviews in qualitative research can be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them—or structured, where there is a strict script that the interviewer does not deviate from. Most interviews are in between the two and are called semi-structured interviews, where the researcher has a few consistent questions and can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. The unstructured interview was the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide victims because the researchers were aware that how much was disclosed about such a sensitive topic should be led by the families, not by the researchers.

Another approach used in qualitative research involves small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue, known as focus groups. The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one- on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses. However, we know from social psychology that group dynamics are often at play in any group, including focus groups, and it is useful to be aware of those possibilities. For example, the desire to be liked by others can lead participants to provide inaccurate answers that they believe will be perceived favorably by the other participants. The same may be said for personality characteristics. For example, highly extraverted participants can sometimes dominate discussions within focus groups.

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with people recovering from alcohol use disorder to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this project sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) . This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this analysis in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative—an interpretation of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

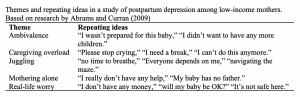

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009) . Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. The table below hows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

“Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk….Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)”

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms, not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances. The table below illustrates the process of creating themes from repeating ideas in the qualitative research gathering and analysis process.

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004). In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches. One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables in a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation. The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Using qualitative research can often help clarify quantitative results via triangulation. Trenor, Yu, Waight, Zerda, and Sha (2008) investigated the experience of female engineering students at a university. In the first phase, female engineering students were asked to complete a survey, where they rated a number of their perceptions, including their sense of belonging. Their results were compared across the student ethnicities, and statistically, the various ethnic groups showed no differences in their ratings of their sense of belonging.

One might look at that result and conclude that ethnicity does not have anything to do with one’s sense of belonging. However, in the second phase, the authors also conducted interviews with the students, and in those interviews, many minority students reported how the diversity of cultures at the university enhanced their sense of belonging. Without the qualitative component, we might have drawn the wrong conclusion about the quantitative results.

This example shows how qualitative and quantitative research work together to help us understand human behavior. Some researchers have characterized qualitative research as best for identifying behaviors or the phenomenon whereas quantitative research is best for understanding meaning or identifying the mechanism. However, Bryman (2012) argues for breaking down the divide between these arbitrarily different ways of investigating the same questions.

Key Takeaways

- The qualitative approach is centered on an inductive method of reasoning

- The qualitative approach focuses on understanding phenomenon through the perspective of those experiencing it

- Researchers search for recurring topics and group themes to build upon theory to explain findings

- A mixed methods approach uses both quantitative and qualitative methods to explain different aspects of a phenomenon, processes, or practice

- This chapter can be attributed to Research Methods in Psychology by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. This adaptation constitutes the fourth edition of this textbook, and builds upon the second Canadian edition by Rajiv S. Jhangiani (Kwantlen Polytechnic University) and I-Chant A. Chiang (Quest University Canada), the second American edition by Dana C. Leighton (Texas A&M University-Texarkana), and the third American edition by Carrie Cuttler (Washington State University) and feedback from several peer reviewers coordinated by the Rebus Community. This edition is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. ↵

Gathering and Analyzing Qualitative Data Copyright © by megankoster is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Lesson 38: Qualitative Data Analysis

In a qualitative research, you analyze or study data that reflect the respondents’ thoughts, feelings, attitudes, or views about something. These are subjective data that are expressed in words, and these words serve as the unit of analysis in a qualitative type of research. You examine these subjective data to understand how related or relevant they are to your research problem or specific research questions.

You collect qualitative data through interviews, observations, or content analysis and then subject them to data analysis. In your data collecting activities, you indispensably experience a lot of things vis-a-vis the sources of data, such as their sizes, shapes, ideas, feelings, attitudes, and so on. If you record these data through verbal language or graphic means, you get to immerse yourself in a qualitative data analysis, not quantitative data analysis, for the latter deals with data expressed in numerical forms. (Layder 2013)

Qualitative data analysis is a time-consuming process. It makes you deal with data coming from wide sources of information. It is good if all the data you collected from varied sources of knowledge work favorably for your research study, but, ironically, some of these may not have strong relation to your research questions. Data analysis in a qualitative research is a rigorous act of a thematic or theoretical organization of ideas or information into a certain format that is capable of presenting groups of responses. Analyzing the data and synthesizing them based on one principal idea, theory, or pattern demand a lot of time and effort, let alone, the methodical ways you have to adhere to in presenting the results as long written discussions containing verbal or graphical explanations of your findings. (Letherby 2012; Silverman 2013; Litchman 2013)

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

Related Resources

- —Understanding Data and Ways to Systematically Collect Data

Self-Learning Modules- Quarter 2 Practical Research 2: SHS, Modules 1-3 View Download

Self Learning Module | ZIP

Curriculum Information

Copyright information, technical information.

Have an account?

Suggestions for you See more

Active and Passive Voice

3rd - 4th , punctuation marks, 1st - 2nd , adjectives and adverbs, 9th - 10th .

Practical Research 1

11th - 12th grade.

50 questions

Introducing new Paper mode

No student devices needed. Know more

Whic of the following best describes the purpose of conducting a qualitative research?

To explore the meaning of people's experiences, culture, etc.

To examine relationships of variables.

To test hypotheses of the study.

To prove a particular theory

What is the first step in conducting research?

Analyze Data

Review the literature

Design research

Define research problem

What is the final step in doing research?

Formulate hypothesis

Interpret and Report

It is the quality of research which tells that sonething is based on direct experience or observation by the researcher.

Research is _________ if it exhibits careful and precise judgment.

Replicability

Identify if it is ethical or unethical.

Acknowledgment of research collaboration and assistance

Invading the respondent's privacy

What represents a population?

Sample size

Sample Mean

Confidence level

_____ is the heart of the study

Significant of the study

Related Literature

- 13. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt There is a set of fixed, predetermined questions which are presented to every participant in the same order and in the same way. Structured interview Semi-structured interview Unstructured interview

- 14. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt Asking participants to recommend others to take part in the research. Systematic sampling Snowball sampling Stratified sampling Random sampling

What is the correct way to cite in text the following source in APA style?

However, Selke et al. (2015) did not find any significant difference in biodegradeability.

However, Selke et al. did not find any significant difference in biodegradeability 1.

However, Selke et al. did not find any significant difference in biodegradeability (Selke,S., Auras,R., (2015) Evaluation of biodegradation. Environmental Science & Technology 49(6)).

However, Selke et al. did not find any significant difference in biodegradeability (Evaluation of biodegradation. Environmental Science & Technology).

This refers to a particular procedure or set of procedures applied in conducting a research or study.

Introduction

Review of Related Literature

Methodology

Findings, Results and Recommendations

A remark, statement or comment based on something one has seen, heard or noticed.

Observation

Noticed Actions

This refers to the information or content from different sources related to the topic.

The sources you used on your research.

It establishes the scope, context and significance of the research to be conducted. This also states the purpose why the study will be conducted.

Results and Recommendations

- 21. Multiple Choice Edit 1 minute 1 pt What research strategy is used by a linguist studies the content of different Web sites and rates their level of English. observation experiment content analysis survey

- 22. Multiple Choice Edit 1 minute 1 pt Which of the following describes the purpose of qualitative research? It describes and answers questions about participants and contexts. It explore a phenomenon to better understand it. It answers question and illuminates issues that cannot be answered by a quantitative research. All of them.

- 23. Multiple Choice Edit 1 minute 1 pt A qualitative research design seeking to describe and analyze all or part of the culture of a community is known as a(n) historical study action research ethnographic study grounded theory

- 24. Multiple Choice Edit 1 minute 1 pt A qualitative research design in which data related to past events is systematically collected and evaluated to describe potential causes, effects, or trends related to those events is known as Ethnographic historical action theory grounded theory

- 25. Multiple Choice Edit 1 minute 1 pt Which of the following must be accomplished first when conducting a research study? Analyze narrative data for underlying themes Negotiate entry into the research site Collect data Interpret the data analysis

- 26. Multiple Choice Edit 2 minutes 1 pt An individual with an exceptional memory is identified.She is capable of recalling major events, the weather, and what she did on any given date. What research method is being used if a psychologist conducts an in-depth investigation of this individual including questionnaires,brain scans, and memory tests? Survey Interview Case Study Naturalistic Observation

What is one disadvantage of a survey ?

People don't tell the truth.

Yields a lot of information

Provides a good way to generate hypotheses

Can provide information about many people since it’s cheap and easy to do

What is Research Misconduct?

Fabrication

Falsification

All of The Above

Which is the name of the genre of books we use for information and facts?

- 31. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt The first step of the research process is searching for sources deciding on a topic and a research question choosing the correct font writing a works cited entry for sources

Data is defined as

the collection of hypothesis

the collection of people

the study of people

the collection of information

- 37. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt Research aimed at gathering an in-depth understanding of an issue by way of open ended questioning, non-statisitical research techniques, or value-based observations. This describes which of the following? Quantitative Research Qualitative Research

Francesca wants to know if her classmates prefer pineapple on their pizza. What research method should Francesca use?

Longitudinal study

An intensive investigation of one or more participants is a

Naturalistic observation

- 40. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt A college counselor met a student who was experiencing stress due to family problems. During lunch, the counselor shared with her friend of the session she had with the student and the family issue the student was facing. This shows that the counselor had breached which ethical code? Informed consent Confidentiality Voluntary participant Withdrawal rights

- 41. Multiple Choice Edit 20 seconds 1 pt ___________ refers to t he protection of people’s identify through not disclosing their name or not knowing it. Confidentiality Privacy Voluntary participation Anonymity

When you would like to explore a phenomenon indepth, you employ

semi-structured interview

structured interview

When you study the group culture, you would employ an approach called

grounded theory

ethnography

In a study, what is a relatively small group out of the total population called?

control group

- 45. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt Selecting participants who just happen to be available is called: Opportunity sampling Volunteer sampling Random sampling Quota sampling

The most significant decision during the process of designing a research study is:

The sampling plan.

The choice of research approach.

The quality of the research design.

The details of tactical research problems.

- 47. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt A word that refers to the process of selecting respondents to answer questions to yield data for a research study. Sampling Selecting

- 48. Multiple Choice Edit 30 seconds 1 pt What does RRL means? Reviewing of relatively literature Review of related literature

What is the thing that you use in gathering data?

The Online Games Addiction of Grade 10 Students of Lanton High School. The underlined word is an example of?

Research Method

Respondents

Explore all questions with a free account

Continue with email

Continue with phone

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2024

Technology, data, people, and partnerships in addressing unmet social needs within Medicaid Managed Care

- Rachel Hogg-Graham 1 ,

- Allison M. Scott 2 ,

- Emily R. Clear 1 ,

- Elizabeth N. Riley 1 &

- Teresa M. Waters 3

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 368 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

29 Accesses

Metrics details

Individuals with unmet social needs experience adverse health outcomes and are subject to greater inequities in health and social outcomes. Given the high prevalence of unmet needs among Medicaid enrollees, many Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) are now screening enrollees for unmet social needs and connecting them to community-based organizations (CBOs) with knowledge and resources to address identified needs. The use of screening and referral technology and data sharing are often considered key components in programs integrating health and social services. Despite this emphasis on technology and data collection, research suggests substantial barriers exist in operationalizing effective systems.

We used qualitative methods to examine cross-sector perspectives on the use of data and technology to facilitate MCO and CBO partnerships in Kentucky, a state with high Medicaid enrollment, to address enrollee social needs. We recruited participants through targeted sampling, and conducted 46 in-depth interviews with 26 representatives from all six Kentucky MCOs and 20 CBO leaders. Qualitative descriptive analysis, an inductive approach, was used to identify salient themes.

We found that MCOs and CBOs have differing levels of need for data, varying incentives for collecting and sharing data, and differing valuations of what data can or should do. Four themes emerged from interviewees’ descriptions of how they use data, including 1) to screen for patient needs, 2) to case manage, 3) to evaluate the effectiveness of programs, and 4) to partner with each other. Underlying these data use themes were areas of alignment between MCOs/CBOs, areas of incongruence, and areas of tension (both practical and ideological). The inability to interface with community partners for data privacy and ownership concerns contributes to division. Our findings suggest a disconnect between MCOs and CBOs regarding terms of their technology interfacing despite their shared mission of meeting the unmet social needs of enrollees.

Conclusions

While data and technology can be used to identify enrollee needs and determine the most critical need, it is not sufficient in resolving challenges. People and relationships across sectors are vital in connecting enrollees with the community resources to resolve unmet needs.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Individuals with unmet social needs, like food and housing insecurity and transportation challenges, experience higher rates of adverse health outcomes [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ] and are subject to greater inequities in health and social outcomes [ 8 ]. Unmet social needs are especially prevalent among Medicaid enrollees [ 9 ]. For this reason, state Medicaid programs are particularly interested in testing strategies that encourage and incentivize Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) to identify and address the complex social needs of enrollees [ 10 , 11 ]. Many Medicaid MCOs are now screening enrollees for their unmet social needs and connecting them to community-based organizations (CBOs) better equipped with knowledge and resources to address these needs [ 12 , 13 ].

The use of screening and referral technology and data sharing are often considered key components in programs integrating health and social services to address social needs [ 12 , 14 ]. Data sharing infrastructure has been highlighted as a way to streamline coordination and social need resolution [ 12 , 14 ]. In some instances, successful integration has facilitated strong connections between health and social services organizations, ensuring that patients move efficiently between sectors [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Despite this emphasis on technology and data collection and some positive integration, research suggests substantial barriers exist in operationalizing effective systems [ 12 , 17 ]. CBOs often have limited resources, financial and personnel, to put toward the use of advanced social need screening and referral systems [ 12 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. The reliance on grant funding and other time-limited resource streams likely presents another barrier in the adoption of tools [ 17 ]. CBOs can also be hesitant to adopt technology and data systems owned by MCOs, hospitals, and other clinically oriented organizations because of data privacy and HIPAA-related issues [ 16 , 20 ].

Research examining health and community partnerships has identified technology adoption by CBOs and other social services organizations as an important barrier to collaboration [ 14 , 15 , 17 ]. Most prior studies examining data and technology include clinical organization perspectives on the use of tools but do not include robust information from community partners [ 12 , 14 , 16 ]. Further, those studies that do include perspectives from multiple organization types on the integration of health and social services are not focused on adopting screening and referral systems. Technology typically emerges in subthemes, and the evidence included does not provide in-depth information on benefits and challenges from both community and clinical partners [ 17 ].

This study examines CBO and MCO perspectives on the use of technology in social need screening and referral. The qualitative analysis presented here is part of a larger mixed methods study examining how Kentucky (KY) MCOs address unmet social needs in partnership with community organizations [ 21 ]. KY offers a unique opportunity to examine strategies addressing Medicaid enrollee needs. Just under 29% of all KY residents are enrolled in Medicaid, making it the third highest enrollment among US states [ 22 ]. KY is also geographically diverse, with distinct urban, rural, and Appalachian regions.

Setting and study population

A project Stakeholder Advisory Board (SAB), including representatives from all Medicaid MCOs, academia, a community-based organization, the State Department for Medicaid Services, and enrollees, met quarterly to provide expertise, guide research, and assist with the dissemination of study results. MCO representatives serving on our SAB were asked to 1) identify individuals in their organization leading efforts to address unmet social needs and population health outcomes among their enrollees and 2) identify CBOs they work closely with in their social need referral process. As part of a targeted sampling strategy, identified contacts were invited via email by the research team to participate in key informant interviews to discuss how MCOs and CBOs address social needs. Inclusion criteria were that participants were at least 18 years old, were employed at an MCO/CBO in Kentucky, and were willing to engage in an interview in English. A total of 32 MCO contacts were invited and 33 CBOs, giving us response rates of 81% and 58% respectively.

Participants

Our sample of 46 participants comprised 26 representatives from 6 MCOs (ranging from 3 to 6 participants per MCO) and 20 representatives from 19 unique CBOs. MCO participants represented various organizational roles, including vice presidents, directors, population health, case management, and community engagement. CBO participants represented roles including directors, Chief Executive Officers, Chief Operating Officers, Medical Coordinators, Presidents, Chief Engagement officers, program managers, and outreach coordinators. The services provided by community-based organizations included food security, health, housing, employment, and work readiness, refugee and immigrant services, and community support; many CBOs addressed multiple social needs. CBO interviewees represented organizations operating in both urban and rural areas of the state.

Data collection

In-depth one-on-one interviews with 46 stakeholders from identified CBOs ( n = 20) and MCOs ( n = 26) were conducted between May 24, 2021, and November 8, 2021. Interviews were conducted via Zoom, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The qualitative researcher and facilitator conducting these interviews have extensive training and experience with structural interviewing using a semi-structured interview guide. The guide used was developed for this study [ 23 ].

Data analysis

We conducted an iterative content analysis of the transcribed interview data using qualitative descriptive analysis [ 24 ], an inductive, low-inference method designed to gain an accurate understanding of a phenomenon in the everyday terms of stakeholders. Our data analysis unfolded in two stages. The first stage involved open coding [ 25 ], in which the transcripts were independently coded by two authors and one study team member (AM, ER, and HS), who then met to discuss and reach consensus on the central themes in the data related to technology and data sharing. In this meeting, the authors identified the themes of to screen for patient needs, to case manage, to evaluate the effectiveness of programs, and to partner with each other. The second stage of analysis involved focused coding, with the three individuals again independently coding transcripts for subthemes within each identified central theme. The coders met again to compare findings and finalize themes (and subthemes for Theme 4). At this time, we recognized that there were areas of alignment, incongruence, and tension between the responses of participants from MCOs and CBOs, and we reached agreement in this meeting about which themes demonstrated each dynamic. Finally, all authors met a third time to review the subthemes and select illustrative quotations for each. All analytic decisions were made through discussion until consensus was reached. We used the team-based approach to reaching consensus, which considered dependability and trustworthiness of the data [ 26 ]. This paper focuses on responses addressing technology platforms and data sharing to support MCO and CBO partnerships.

We identified several themes related to the use of technology and data in MCO-CBO partnerships to address enrollee social needs. MCOs and CBOs noted differing levels of need for data, differing incentives for collecting and sharing data, and differing valuations of what data can or should do. MCO and CBO interviewees described how they collect and use data in their work, which fell into four major themes: to screen for patient needs, to case manage, to evaluate the effectiveness of programs, and to partner with each other. Within these themes, the interview responses illuminated areas of alignment between MCOs/CBOs, incongruence, and tension (both practical and ideological; see Table 1 ).

Theme 1. Alignment on collecting data to identify and prioritize patient needs

Using data to identify and prioritize patient needs was largely an area of alignment for MCOs and CBOs. All MCOs and nearly all CBOs recognized the value of data in this area. As one CBO noted,

“By completing the needs assessment with our families, it helps the case managers understand your immediate needs.”

Similarly, MCOs often used the data for targeted programming and social needs referrals,

“ When our members are enrolled, we attempt to engage them in our health risk assessment. And so that health risk assessment is going to not only ask them questions about their specific health, but also about some additional needs that would help us be able to identify them at enrollment and also to be able to target them for programs and other [benefits].”

Several MCO and CBO interviewees also discussed using the data to understand individual enrollee/client needs and to track overall trends among their clients. As one MCO shared,

“The end of 2021, we had a tremendous amount of referrals for food. And so maybe we need to look at doing some of our community investment work and partnering with additional providers and community partners that are in that space for next year.”

There were some differences between MCOs and CBOs in the formality and degree to which social need data was collected. MCO interviewees, particularly those on the front lines of this work, could describe detailed and comprehensive data screening metrics for patient needs and how needs were tracked in their data systems. Using data on patient needs to identify areas for intervention was described as an essential part of patient care:

“We use the screening data, not just to meet the individual member need, but to also inform health equity and types of programs that we bring to play...”

CBO interviewees, on the other hand, had greater variability in their responses about the importance of using data on social needs at an organizational-level. Most described data as having potential value but stopped short of calling it essential for their operations. One CBO stated,

“I don't know what I would do with the information if we had it.”

Conversely, one food-oriented CBO reported that they collect demographic data and use that to help with distribution,

“So think about the local pantry that I talked about earlier. Because we know, we drive a truck into [KY County]. We know that the last five times that we've been in [KY County], we saw, on average, 150 households at each of those five visits. That tells us how much product to put on the truck so that we don't run out.”

Theme 2. Differences in organizational capacity, mission, and resources influenced variability in data use to support case management

Using data to support case management activities was an area of both alignment and incongruence between MCOs and CBOs. All MCOs and many CBOs saw value in using data systems to identify resources available, track referrals and follow-ups, keep notes, and stay in contact with patients. However, there was considerable variability in the sophistication of the data systems. Most MCOs reported elaborate data tracking systems designed specifically for screening, referral, and tracking (e.g., combining medical records applications with Unite Us [ 27 ] or Find Help (formerly Aunt Bertha [ 28 ]). Some CBOs have systems designed specifically for tracking data (e.g., Electronic Health Systems or Vesta [ 29 ]), whereas others employ systems not designed specifically for tracking (e.g., Microsoft Excel spreadsheets). Most CBOs used informal data collection to screen for needs (e.g., Post-it notes, memory, a hand-written planner), and several CBOs reported that they did not use formal data systems to screen and track patient needs at all,

“Are you kidding me? No books. What I usually tell anybody who's working with me is to either email me or text me, and that's my filing system.”

MCO interviewees were more likely to report using data analytics to support and enhance case management. Frontline MCO workers spoke about this aspect of data use more often than executives, and many saw data systems as the answer to case management problems. As one MCO stated,

“We do have a case management system that keeps track. So, we are able to schedule calls. They're able to pop back up on a calling queue, so that we're able to check in with members and attempt to continuously reach out to them. So, that's kind of how we try to make sure that those members don't fall through the cracks by continuously following up.”

Most CBOs indicated that case management occurred but was more personalized and less attached to data and technology use,

“We have a database that we use for client notes. We just record case notes in there. Some of our caseworkers keep basic Excel spreadsheets on their specific clients and what they're working on. Most of that would be informal.”

Only one MCO specifically mentioned the limits of data systems for tracking and the need for a personal touch in case management, a perspective more in line with most CBO interviewees. The MCO shared this when discussing platform capabilities, stating,

“We have a case management platform, of course, where we document everything, because just like everywhere else, if you don't write it down, it didn't happen, but a lot of it is just that manual follow-up and that human touch.”

The variability in tracking system sophistication and capabilities between MCOs and CBOs was also frequently highlighted as one of the critical challenges in collaboration and a notable source of frustration for both sides. When discussing their partnerships with MCOs and data sharing, one CBO stated,

“They really wanted to know about it. And so had to spend considerable time with them about, ‘This is what we do, this is how stuff works.’ And including it's like, ‘No, we can't track. We have no way of tracking [MCO] clientele through the [KY food security] program’."

While MCO interviewees often noted this tension in collaboration, they were aware that capacity and resources typically made it harder for CBOs to track and collect data. One MCO interviewee noted,

“I think the challenge is just the data piece and the complexity of the regulations that we have to navigate, all for good reason. When you're talking about how to best leverage those community resources, if we can't kind of have those data exchanges, it makes it so much more difficult. And so when you're trying to get at outcomes or have simplified referral processes, it just makes it harder because you may not be able to get through, they may not have the HIPAA, the high-tech clearance or whatever it is. It's expensive for them to have to do that.”

Theme 3. Funding and reimbursement structures shaped how MCOs and CBOs used data to evaluate program effectiveness

We found limited alignment between MCO and CBO perspectives on using data to evaluate social need programming and partnerships. Instead, evaluation was an area fraught with incongruencies and tension between the two sectors. The financial incentives and pressures for using data differ substantially between MCOs and CBOs. MCOs reported using data to evaluate the financial impact or effectiveness of programs (particularly claims data/utilization metrics) and partnerships to justify investments or show MCO executives that meeting unmet social needs is good business. As one MCO interviewee explained,

“I think every anything that we’re doing with the community-based partner, we’re studying all that. We’re studying the reduction, so I’m able to say, okay, because we have this member in this [CBO program], in this residential treatment program, not only mama’s healthier, baby is not born exposed to opiates, no NICU, ER utilization down. I think that’s the neat thing, there’s your answer, right?”

One reason MCOs seem to be driving data collection for demonstrated effectiveness/return on investment is that they are heavily regulated in terms of how they can invest funds,

“We are doing payment innovation, we want to take money out of what’s being spent on health care and invest it into social services and that is not easy.”

As another MCO highlighted continued investment often depends on what they can demonstrate,

“Sometimes, there are finance guidelines, right? Like when I’m fighting for my budget, they’ll say, ‘Well, where’s the return on investment numbers?’.”

Conversely, only a few CBOs used data-driven evaluation to support their financial operations. When CBOs did report using data for evaluation, it was typically in relation to using outcomes data in grant writing to gain funding specifically from MCOs, data which may not serve any other useful purpose for the CBO. As one CBO stated,

“Another kind of pain point, and for like one of the managed care companies that we contract with, they give us $8,000 a year. But the requirements to receive that $8,000 is very data heavy. We have to go through and pull all this data, get different releases signed with the participants. It’s great to have extra money, but it’s also a lot of work and nothing really being tied to it, if that makes sense. They just want the data to be able to review and any good outcomes and success stories and stuff like that, which is great. But it’s a lot of work for not a lot of money.”

Theme 4. Tension in using data to partner with other MCOs and CBOs

Both MCO and CBO interviewees described several reasons why they engage in data sharing within MCO-CBO partnerships (e.g., to garner funding, demonstrate effectiveness, or enhance case management), even if the values and importance placed on data sharing differed between agency types. When data sharing existed or was being contemplated, interviewees still described several barriers to sharing, both practical and ideological.

Overwhelmingly, CBO interviewees expressed a perception that they had to report data to the MCOs to prove impact so MCOs would maintain the partnership or provide funding. The first subtheme revealed a notable ideological difference between the MCOs/CBOs regarding whether data was useful to evaluate program effectiveness . While data-driven evaluation is routine and relied upon by most MCOs, many CBO interviewees perceived that data and metrics could harm their operations, diverting time and energy from serving clients and that there is much about program effectiveness that simply cannot be captured using formal data tracking systems. When discussing the course of their partnerships with MCOs, one CBO highlighted,

“So what does that support look like? Well, it is financial support for it. And, initially, it was very much focused on their clientele with [MCO] clientele and trying to track metrics about the impact that having access to better nutrition was going to have on the outcomes for their folks, right? So over the course of two years, I mean, we were able to show, "we," and I mean that collectively, we're able to show that it does have a positive impact. I mean, for [MCO], I think it's safe to say that they realize that it is more cost-effective to invest upfront in increasing access to healthy food better than the back end, to drugs and health care costs and all that kind of stuff. So they have, again, they have maintained that partnership.”

Indeed, most MCOs expressed wanting data from their CBO partners to justify the relationship and a reluctance to build relationships if data capacity is not present. One MCO discussed this directly, stating,

“They come us and they send us their flyer and they're like, "We want [MCO] to partner with us on our heart walk and we want you to give us $20,000." We still get a lot of people that do that because that's their old business model. Most of the time, we don't engage with those types of organizations. I always say, we want to hear from someone and I will take a meeting always if a community-based organization says, "We have an evidence-based solution that is solving for X," or "We have a solution that is solving for X and we want to work with you to help us prove that it's evidence-based," or we have research capabilities...”

Subtheme 2 illustrates how underlying the data sharing tension between CBOs and MCOs are challenges related to the need for more effective and user-friendly interfacing between tracking and referral systems, as well as the limited capacity of CBOs to track and analyze data . As mentioned, the sophistication of CBO data systems is highly variable, and even those organizations with more advanced tracking systems struggle with data sharing. When asked about data sharing, one CBO noted,

“Well that's another pain point. In my history, in my experience, every health plan has their own data system that don't talk to one another, that are very convoluted and messy. Right now we're filling stuff in on an Excel spreadsheet.”

Several MCOs also highlighted this as a challenge. As one MCO stated,

“Our system is designed to deal with hospital systems and health care providers, there's many different levels. I mean we go through a pretty comprehensive system and you have to have all kinds of, meet all kinds of requirements, share data, and different pieces that for a small community-based organization providing housing services, they might not even have the capacity to meet those requirements.”

Although some CBOs reported sharing data with MCOs willingly and saw this sharing as a natural facet of their partnership, other CBOs described significant concerns about data privacy and ownership ( subtheme 3 ). They noted how important data privacy was to the clients they served and how their organization valued serving their clients without the need to collect personal data or share it. Some CBO interviewees indicated that sharing or even collecting private client data might compromise their ability to do their work and serve their clients well,

“We respect their privacy, and we will never do any sharing of their data. In fact, a lot of people who come to us, one of the reasons they're with us is because we do not require them to show an ID.”

Subtheme 4 revealed how CBO and MCO interviewees expressed concerns about relying on data and technology as the solution to social need screening and referral systems building . Interviewees felt that data does not adequately capture utilization or partnership benefits. Primarily, this was attributed to issues related to data quality. One MCO interviewee highlighted this when discussing the challenges of understanding the quality of social need services:

“We also don't have a really long track record of managing quality for this type of provider. We have very distinct report cards and quality cards for every hospital in the state of Kentucky. I can tell you what the outcomes for [Hospital 1] compared to [Hospital 2] and compared to [Hospital 3]. We have very clear metrics on those types of things. We do not have that for the sort of soft services, especially since we don't pay for them.”

Most CBOs articulated challenges with data quality centered on their perception that data does not tell the whole story about what is happening at their organization and in the community. As one CBO noted,

“ We have a people problem. And I think right now there are a lot of hospitals and other organizations, MCOs, that want to kind of tech their way out of this. [T]hey're looking for technological [solutions] to try to streamline and expand services to folks. And that's just not really the answer. You need people.”

MCO interviewees recognized that databases and their tracking systems may be limited in what they capture. In subtheme 5 , several noted their technological ability to comprehensively track organizations in a community as a significant limitation . Maintaining accurate data has also been challenging because of community organization turnover and closures. As one MCO highlighted,

“These national repositories don't have the local knowledge so they don't know the churches that do the hot meals and they don't know the small organizations that are getting up and off their feet and tied to this one or that one, or it's an offshoot of whatever. There are some smaller organizations that don't always get into those big directories and you don't always know about them unless you have boots on the ground, people who live and work in the community and actually know what those are.”

Similarly, another MCO highlighted CBO data capacity as a major challenge in their partnerships, stating,

“Biggest challenges. I guess, you could say data might be the challenges, to close the loop around the return on investment on some of these organizations that are not ... They just don't have the staffing, or the professional leadership, if you will, to do all the tracking. The ones that do, do it very well. The ones that don't, it's just that they don't have the resources.”

In the final subtheme, all MCO interviewees acknowledged that CBOs are doing good work , even if that cannot be quantified, and the ability to share that data is often related to CBO capacity and resources. One MCO shared,

“[Food Pantry CBO] who's just like [Named Female] and her husband [Named Male], they might be the greatest people and we might know that members like going there versus the other food bank because [Named Female] like bakes brownies and gives them a hug and we want to quantify that but also it's just not realistic because they don't have the infrastructure sometimes that's needed to prove the business case, solidify the partnership and ultimately inform policy.”

Our study found alignment as well as discordance between MCOs and CBOs about how and when to leverage technology and data despite their shared mission to meet the unmet social needs of enrollees. Our findings offer important insights regarding why data and technology may create a barrier to effective MCO-CBO partnerships, potentially hindering efforts to improve health and social outcomes. They also provide guidance and identify key considerations for developing programs and partnerships that may be more effective in coordinating efforts between the two organizations.

As we observed in Themes 1 (Alignment on collecting data to identify and prioritize patient needs) and 2 (Differences in organizational capacity, mission, and resources influenced variability in data use to support case management), results suggest that data and technology can be important tools in screening and referral for social needs, but they are far from a universal panacea. Our data indicate that both logistical and cultural disconnects between MCOs and CBOs significantly limit data collection and sharing for coordination of services. On the logistical side, CBOs have extremely limited capacity (software, workforce) to collect and share data. Several participants reported serious concerns with collecting and sharing confidential client information. To make matters worse, MCOs use a range of proprietary and sophisticated referral and tracking systems that severely tax the resources and capacity of CBOs. On the cultural side, while MCOs view data and technology as essential to partnering with CBOs to meet enrollee social needs, CBOs do not. In fact, as we found in Theme 3 (Funding and reimbursement structures shaped how MCOs and CBOs used data to evaluate program effectiveness), many CBOs see data collection as a necessary evil to garner funding from potential donors. Instead, they emphasize the relationship-honoring aspects of their work as a core value.

Solutions that only focus on providing data collection and tracking technology to CBOs are unlikely to be completely successful because they fail to address the disparate cultures found in MCOs vs. CBOs. This conclusion is robustly supported by Theme 4 from our analysis (Tension in using data to partner with other MCOs and CBOs).In many ways, CBOs may view MCO efforts to grow their technological capacity as imposing profit-seeking values, norms, and structure rather than seeking true understanding and partnership. CBOs’ low enthusiasm for and capacity to use data can create difficulty for MCOs when MCOs rely on CBOs for data to justify their funding streams and partnerships. This fundamental disconnect is likely to severely impede partnership efforts without reevaluating the strengths and values each sector brings to the collaborative [ 30 ].

Successful partnerships are built on shared interest and trust [ 31 ]. Our study suggests a strong alignment between MCOs and CBOs in addressing the social needs of highly vulnerable Medicaid beneficiaries. This values alignment may offer a foundation for partnership. Our work underscores a key finding across studies on cross-sector partnerships integrating health and social services, more work must be done to build trust and understand each other’s organizational values [ 17 , 19 , 32 ]. MCOs and CBOs need each other to address social determinants of health (SDOH) effectively. MCOs have the resources and responsibility for finding more effective ways to support their beneficiaries. CBOs are ‘on the ground’ and have the trust of the clients they serve (many of whom are Medicaid enrollees). Forums that create a level playing field for both types of organizations and facilitate safe conversations to build trust are essential.

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has developed a three-pronged strategy for addressing SDOH: (1) better data, (2) improving health and social services connections, and (3) whole-of-government collaborations [ 8 ]. Our study suggests that their second strategy is essential and could be far more difficult than many imagine. Facilitating honest conversations about identifying and addressing the challenges in building these connections is a critical first step. Because many challenges involve “hearts and minds” and organizational culture, addressing these challenges will need to be a slow and iterative process. Moving forward, organizations like MCOs and other clinical partners must carefully consider how data and social need screening and referral technology can be a value-add to CBOs and not another burden on their already strained capacity.

Limitations

While our sample included at least one representative from all six state MCOs and nineteen different CBOs, the generalizability of study results may not apply to other states. However, many of the MCOs in KY operate in national markets and often use similar strategies in different geographic areas. Insights likely shed light on similar efforts and challenges in other states and markets. Future studies examining the use of data and technology nationally in social need resolutions would provide confirmation of the results we present and any potential geographic variability. Additionally, participant perspectives may not necessarily represent their MCOs or CBOs. Finally, our cross-sectional view of technology and referral platforms provides a snapshot of current processes; a more in-depth longitudinal study would capture changes over time as technology constantly evolves.

Despite a shared mission to meet unmet social needs, MCOs and CBOs do not agree on how and when to leverage technology and data. This discordance is a significant barrier to effective partnerships. Technology offers powerful tools for identifying and prioritizing enrollee needs and connecting them with services. However, trust and a shared understanding of organizational cultures and goals are critically needed to allow technology to realize its potential. Current efforts to build effective MCO-CBO partnerships should focus on creating a level playing field for all organizations and a space for honest conversations that can build strong connections and sustainable relationships across sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Deidentified aggregated data is available from the corresponding author ([email protected]) on reasonable request.

Gottlieb L, Tobey R, Cantor J, Hessler D, Adler NE. Integrating social and medical data to improve population health: opportunities and barriers. Health Aff. 2016;35(11):2116–23.

Article Google Scholar

Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–10.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Silverman J, Krieger J, Kiefer M, Hebert P, Robinson J, Nelson K. The relationship between food insecurity and depression, diabetes distress and medication adherence among low-income patients with poorly-controlled diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1476–80.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Hong C, Stowell BJ, Tirozzi KJ, Traore CY, Atlas SJ. Addressing basic resource needs to improve primary care quality: a community collaboration programme. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(3):164–72.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cole MB, Nguyen KH. Unmet social needs among low-income adults in the United States: Associations with health care access and quality. Health Serv Res. 2020;55:873–82.

Fiori KP, Heller CG, Rehm CD, Parsons A, Flattau A, Braganza S, Lue K, Lauria M, Racine A. Unmet social needs and no-show visits in primary care in a US northeastern urban health system, 2018–2019. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(S2):S242–50.

Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities—addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8–11.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

De Lew N, Sommers BD. Addressing social determinants of health in federal programs. InJAMA Health Forum 2022;3(3):e221064-e221064). American Medical Association.

Thompson T, McQueen A, Croston M, Luke A, Caito N, Quinn K, Funaro J, Kreuter MW. Social needs and health-related outcomes among Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(3):436–44.

Moreno-Camacho CA, Montoya-Torres JR, Jaegler A, Gondran N. Sustainability metrics for real case applications of the supply chain network design problem: A systematic literature review. J Clean Prod. 2019;10(231):600–18.

Apenteng BA, Kimsey L, Opoku ST, Owens C, Peden AH, Mase WA. Addressing the social needs of Medicaid enrollees through managed care: lessons and promising practices from the field. Popul Health Manag. 2022;25(1):119–25.

Cartier Y, Fichtenberg C, Gottlieb LM. Implementing Community Resource Referral Technology: Facilitators And Barriers Described By Early Adopters: A review of new technology platforms to facilitate referrals from health care organizations to social service organizations. Health Aff. 2020;39(4):662–9.

Center for Health Care Strategies [Internet]. Supporting social service and health care partnerships to address health-related social needs: case study series. [updated 2018; cited 2023 Nov 9] Available from: https://www.chcs.org/project/partnership-healthy-outcomes-bridging-community-based-human-services-health-care/ . Accessed March 2, 2023.

Klein S, Hostetter M. Leveraging Technology to Find Solutions to Patients’ Unmet Social Needs. The Commonwealth Fund; June 21, 2017. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2017/jun/leveraging-technology-find-solutions-patients-unmet-social-needs

Blavin F, Smith LB, Ramos C, Ozanich G, Horn A. Opportunities to Improve Data Interoperability and Integration to Support Value-Based Care. 2022.

Massar RE, Berry CA, Paul MM. Social needs screening and referral in pediatric primary care clinics: a multiple case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1369.

Hogg‐Graham R, Edwards K, L Ely T, Mochizuki M, Varda D. Exploring the capacity of community‐based organisations to absorb health system patient referrals for unmet social needs. Health Soc Care Commun. 2021;29(2):487–95.

Amarashingham R, Xie B, Karam A, Nguyen N, Kapoor B. Using community partnerships to integrate health and social services for high-need, high-cost patients. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2018;2018:1–11.

PubMed Google Scholar

Agonafer EP, Carson SL, Nunez V, Poole K, Hong CS, Morales M, et al. Community-based organizations’ perspectives on improving health and social service integration. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Petchel S, Gelmon S, Goldberg B. The Organizational Risks Of Cross-Sector Partnerships: A Comparison Of Health And Human Services Perspectives: A legal and policy review to identify potential funding streams specifically for Accountable Communities For Health infrastructure activities. Health Aff. 2020;39(4):574–81.

Hogg-Graham R, Scott AM, Stahl H, Riley E, Clear ER, Waters TM. COVID-19 and MCO-community partnerships to address enrollee social needs. Am J Managed Care. 2023;29(3).

KFF. Medicaid State Fact Sheets 2023 [Available from: https://www.kff.org/interactive/medicaid-state-fact-sheets/ .

Hogg-Graham R, Scott AM, Waters TM. Medicaid Managed Care Organizations and Community Based Organizations Social Need Strategies Interview Guide. University of Kentucky. 2021.

Sandelowski M. Using qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(10):1366–86.

Thornberg R, Charmaz K. Grounded theory and theoretical coding. The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. 2014;2014(5):153–69.

Cascio MA, Lee E, Vaudrin N, Freedman DA. A team-based approach to open coding: Considerations for creating intercoder consensus. Field Methods. 2019;31(2):116–30.

Unite Us. Cross-sector collaboration software powered by community. [updated 2023; cited 2023 Nov 9]. Available from: https://uniteus.com/ .

FindHelp.org. Social Care Technology [Internet]. [updated 2023; cited 2023 Nov 9]. Available from: https://company.findhelp.com/ .

The Partnership Center. Vesta [Internet]. [updated 2023; cited 2023 Nov 9]. 2023; Available from: https://thepcl.net/vesta.html .

Varda DM, Retrum JH. Collaborative performance as a function of network members’ perceptions of success. Public Perform Manag Rev. 2015;38(4):632–53.

Varda DM, Chandra A, Stern SA, Lurie N. Core dimensions of connectivity in public health collaboratives. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(5):E1-7.

Byhoff E, Taylor LA. Massachusetts community-based organization perspectives on Medicaid redesign. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):S74–81.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Study Advisory Board for their help in guiding the research.

This research was supported by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant as part of the Research in Transforming Health and Health Systems Program (Grant ID 77256). Research reported in this publication was also supported by the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, Department for Medicaid Services under Agreement C2517 titled “Medicaid Managed Care Organizational Strategies to Address Enrollee Unmet Social Needs.” The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Cabinet for Health and Family Services, Department for Medicaid Services.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Management and Policy, College of Public Health, University of Kentucky, 111 Washington Ave, 107B, Lexington, KY, USA

Rachel Hogg-Graham, Emily R. Clear & Elizabeth N. Riley

Department of Communication, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA

Allison M. Scott

Institute for Public and Preventive Health, Augusta University, Augusta, GA, USA

Teresa M. Waters

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Concept and design (RH-G, AMS, TMW); acquisition of data (RH-G, AMS, ERC, TMW); analysis and interpretation of data (RH-G, AMS, ER, TMW); drafting of the manuscript (RH-G, AMS, ER, ERC, TMW); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (RH-G, AMS, ER, TMW); provision of patients or study materials (RH-G, ERC); obtaining funding (RH-G, TMW); administrative, technical, or logistic support (RH-G, ERC, TMW); and supervision (RH-G).

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rachel Hogg-Graham .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

All research activities involving human subjects have been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Kentucky. Informed consent was verbally obtained by all participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hogg-Graham, R., Scott, A.M., Clear, E.R. et al. Technology, data, people, and partnerships in addressing unmet social needs within Medicaid Managed Care. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 368 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10705-w

Download citation

Received : 13 November 2023

Accepted : 11 February 2024

Published : 23 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10705-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social determinants of health

- Managed care organizations

- Health care organizations and systems

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Newsletters

- Publications

- County Offices

- Distance Ed

- Staff Directory

- 4-H Forestry

- Youth Livestock

- Youth Poultry

- 4-H Shooting Sports

- Health and Wellness

- Ambassador Program

- Collegiate 4-H

- Disaster Response-Youth

- Keys to the Community

- SAFETY Ambassador Program

- Join 4-H Robotics Club

- Support 4-H

- Wildlife Youth Education

- Youth Horse

- Youth Projects

- Bost Conference Center

- County Extension Offices

- Centers and Institutes

- Comprehensive Department Heads

- Research and Extension Center Heads

- Regional Extension Coordinators

- Extension Administrative Council

- Extension Leadership Council

- Extension Matters Magazine

- Program and Staff Development

- Research and Extension Centers

- Undergraduate Apprenticeship Program

- Agricultural Economics

- Catfish Marketing

- Catfish Water Quality

- Harvesting, Loading, and Transport

- Nutrition, Feeds, and Feeding

- Freshwater Prawns

- Hybrid Striped Bass

- Production Phases and Systems

- Christmas Trees

- Commercial Fruit and Nuts

- Green Industry

- Greenhouse Tomatoes

- Nursery Safety Videos

- Organic Fruit and Vegetables

- Other Vegetables

- Peas and Beans

- Tomato Pepper and Eggplant

- Watermelon Cantaloupe and Cucumber

- Mississippi Boll Weevil Management Corporation

- Insects-Crop Pests

- Master Irrigator

- Plant Diseases

- Sweet Potatoes

- Watermelons

- Weed Control for Crops

- Agri-business

- Growing Your Brand

- Agricultural Engineering

- Biotechnology

- Farm Safety

- Remote Sensing Technology

- Women for Agriculture

- Spray Drones

- Pre-Planting

- Crop Growth Stages

- End of Growing Season

- Safety and Regulations

- Sciences of Remote Sensing

- Types of UAS

- Fertilizers - Forages

- Insects-Forage Pests

- Management - Forages

- Weed Control for Forages

- Animal Health

- Beef Calendar

- Beef Publications

- Cattle Business in Mississippi Articles

- Apiculture: Honey Bee Health

- Goats and Sheep

- Small Animals

- Culinary Tourism

- Farmers Markets

- Local Food System Economies

- Marketing and Business Planning

- Specialty Crop Production

- Pesticide Applicator Certification

- Mississippi Land Resource Areas

- Soil Acidity

- Soil Fertility

- Soil Health

- Soil Testing

- About TCALP

- Advisory Council

- Contact TCALP

- Current Class

- TCALP Frequently Asked Questions

- 2020 Census

- County Elected Office

- Decision to Run

- Campaign Finance

- Voter and Election Information

- Contacts & Resources

- Oil and Gas

- Disaster Response

- Economic Development

- Extension Center for Economic Education and Financial Literacy

- Junior Master Wellness Volunteer

- MS Volunteer Leaders Association

- Master Clothing Volunteers

- Master Gardener

- Mississippi Homemaker Volunteers

- Public Water System Assistance Program

- Rural Development

- Small Business

- MSU Extension Head Start

- Nurturing Homes Initiative

- Mississippi Child Care Resource and Referral

- Equine Assisted Therapy Programs

- Family Dynamics

- Basic Money Management

- Disaster Relief

- Estate and Financial Planning

- Fraud and Identity Theft

- Housing and Homebuyer

- Volunteer Money Mentors

- Youth Financial Literacy

- Creating Healthy Indoor Childcare Environments

- Produce Safety

- AIM for CHangE

- Colon Cancer Screening

- Dining with Diabetes

- Growing Well

- Nutrition and Wellness

- Prescription Opioid Misuse

- Mental Health First Aid

- Farm Stress

- Rural Health

- Forage Pests

- Household Insects

- Human Pests

- Insect Identification

- Ornamental Plants

- Vegetable Gardens

- Cut Flowers and Houseplants

- Floral Design

- Flower Gardens

- Gardening Through the Seasons Video

- Herb Gardens

- Insects-Home Lawns

- Insects-Ornamental Plants

- Insects-Vegetable Gardens

- Healthy Soils and Water

- Landscape Management

- Landscape and Garden Design

- Plants and Wildlife

- Landscape Resources

- Mississippi Landscape Gallery

- Professionals Corner

- Diversity of Plants

- Energy Savings

- Healthy Soils

- Healthy Water Practices

- Integrated Pest Control

- Places for Wildlife

- Fruit and Nut Disease Calendar

- Fruit and Nut Disease Publications

- Fruit and Nut Disease Updates

- Plant Disease and Nematode Diagnostic Services

- Vegetable Disease Calendar

- Vegetable Disease Publications

- Vegetable Disease Updates

- The Story of Plants and People

- Turfgrass and Lawn Management

- Weed Control for Lawn and Garden

- Youth Gardening

- Construction

- Pond and Lake Water Quality

- Fish Management

- Weed Control

- Carbon Credits

- Disaster Recovery