Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Published on June 12, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalized to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

Note that quantitative research is at risk for certain research biases , including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Be sure that you’re aware of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data to prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analyzed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualize your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalizations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

First, you use descriptive statistics to get a summary of the data. You find the mean (average) and the mode (most frequent rating) of procrastination of the two groups, and plot the data to see if there are any outliers.

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

Quantitative research is often used to standardize data collection and generalize findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardized data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analyzed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalized and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardized procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved March 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Please log in to save materials. Log in

- Resource Library

- Research Methods

- Vgr-social-work-research

Lesson 10: Sampling in Qualitative Research

Lesson 11: qualitative measurement & rigor, lesson 12: qualitative design & data gathering, lesson 1: introduction to research, lesson 2: getting started with your research project, lesson 3: critical information literacy, lesson 4: paradigm, theory, and causality, lesson 5: research questions, lesson 6: ethics, lesson 7: measurement in quantitative research, lesson 8: sampling in quantitative research, lesson 9: quantitative research designs, powerpoint slides: sowk 621.01: research i: basic research methodology.

The twelve lessons for SOWK 621.01: Research I: Basic Research Methodology as previously taught by Dr. Matthew DeCarlo at Radford University. Dr. DeCarlo and his team developed a complete package of materials that includes a textbook, ancillary materials, and a student workbook as part of a VIVA Open Course Grant.

The PowerPoint slides associated with the twelve lessons of the course, SOWK 621.01: Research I: Basic Research Methodology, as previously taught by Dr. Matthew DeCarlo at Radford University.

Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

Apr 19, 2012

370 likes | 1.73k Views

Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods. Gillian Livesey LTSN-ICS University of Ulster. TEACHING RESEARCH METHODS LTSN-BEST/ICS Workshop 3 rd October 2003. Overview. Qualitative and Quantitative Research Purpose of Research Qualitative and Quantitative Methods Teaching

Share Presentation

- deep learning strategies

- william gossett

- ulster teaching research methods

- qualitative -v-

- systems planning

- encourage students

Presentation Transcript

Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods Gillian Livesey LTSN-ICS University of Ulster TEACHING RESEARCH METHODS LTSN-BEST/ICS Workshop 3rd October 2003

Overview • Qualitative and Quantitative Research • Purpose of Research • Qualitative and Quantitative Methods • Teaching • Resources • Assessment

Research Methods • Research methods are generally categorised as being either quantitative or qualitative. • What matters is that the methods used fit the intended purposes of the research!

Qualitative and Quantitative Paradigms • The qualitative paradigm concentrates on investigating subjective data, in particular, the perceptions of the people involved. The intention is to illuminate these perceptions and, thus, gain greater insight and knowledge. • The quantitative paradigm concentrates on what can be measured. It involves collecting and analysing objective (often numerical) data that can be organised into statistics.

Qualitative and Quantitative Research

Research The purposes of research can be categorised as: • Description (fact finding) • Exploration (looking for patterns) • Analysis (explaining why or how) • Prediction (forecasting the likelihood of particular events) • Problem Solving (improvement of current practice)

Descriptive Research • Seeks to accurately describe current or past phenomena - to answer such questions as: • What is the absentee rate for particular lectures? • What is the pass rate for particular courses? • What is the dropout rate on particular degree programmes? • What effect does a particularly quality audit process have on teacher morale?

Analytical Research • Seeking to explain the reasons behind a particular occurrence by discovering causal relationships. Once causal relationships have been discovered, the search then shifts to factors that can be changed (variables) in order to influence the chain of causality. Typical questions are: • Why is there a preponderance of female students on 1st level teacher training programmes? • What factors might account for the high drop-our rate on a particular degree programme?

Predictive Research • Seeks to forecast the likelihood of particular phenomena occurring in given circumstances. It seeks to answer such questions as: • Will changing the start time achieve a higher attendance rate at our lectures? • Will introducing anonymous marking reduce the gender imbalance in the achievement of 1st class degrees? • Will increasing the weighting for course work encourage students to adopt deep learning strategies?

Problem Solving Research / Action Research • Action-research is a form of problem solving based on increasing knowledge through observation and reflection, then following this with a deliberate intervention intended to improve practice. • Educational action-research describes a family of activities in curriculum development, professional development, school improvement programmes, and systems planning and policy development. • Participants in the action being considered are intricately involved with all of these activities.

Typical Methods

Research Methods Categorised by Activity

Teaching: Elementary Concepts • What is a Variable? • Scales of Measurement • Qualitative -v- Quantitative • Continuous -v- Categorical / Dichotomous • Independence -v- Dependence

Teaching: Selecting Statistics

William Gossett - nicknamed ‘Student’ was a chemist at the Guinness brewery in Dublin and developed the student t-test in 1908 to ensure that each batch of Guinness was as similar as possible to every other batch! The t-test is used to compare two groups and comes in at least 3 flavours.

Teaching: Software • Spreadsheets • EXCEL • Statistical Software • SPSS (http://www.spss.com/) • MINITAB (http://www.minitab.com/) • SAS (http://www.sas.com/)

Resources http://trochim.human.cornell.edu/

Resources http://www.socsciresearch.com/

Assessment • Written – a report, research proposal or evaluation • Group Work – interdisciplinary groups • VLE – internet • Peer Tuition • Peer Assessment • Multiple Choice – maybe online • Exam – written or using computer • CAA, QTI

Conclusion What matters is that the methods used fit the intended purposes of the research!

- More by User

The complementarity of qualitative and quantitative research methods

The complementarity of qualitative and quantitative research methods. IN5000, April 25, 2019 Asbjørn Følstad, SINTEF. Quick quiz: What will be the format of this lecture ? Lecturing . Group discussions and presentations . None of the above. Content. Research process

482 views • 13 slides

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods. Ryan Cannon Adriana Cantu. Focus Groups. A focus group is a form of qualitative research in which a group of people are asked about their attitude towards a product, service, concept, advertisement, idea, or packaging.

609 views • 20 slides

Ergonomics: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

Ergonomics: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. Every Method Has Both Qualitative and Quantitative Aspects There is No Clear Distinction Between Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches Professional Judgment is Required With Any Methodology. Methods. Walk-Through and Observation Checklists

337 views • 6 slides

QUALITATIVE VS. QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

QUALITATIVE VS. QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH. QUAntiTATIVE RESEARCH. The goal is scientific objectivity, the focus is on data that can be measured numerically. QUALITATIVE RESEARCH.

1.22k views • 5 slides

Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Methods. Roger Pulwarty, NOAA and Mary Hayden, University of Colorado WAS*IS/Climate and Health July 20, 2006. Points to ponder: What’s quantitative? What’s qualitative? Who uses these approaches, why and what do they think of each other? .

460 views • 23 slides

Options for Blending Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods

Options for Blending Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods. Ian McDowell (Based on a seminar presentation in 1997). Overview. Epidemiologic research methods are gradually evolving in recognition of inadequacies in current methods

596 views • 15 slides

Qualitative vs. Quantitative research methods

Qualitative vs. Quantitative research methods. PART I – THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS PART II – EVALUATION OF QUALITATIVE METHODS INCLUDING CONCEPTS LIKE CREDIBILITY, RESEARCHER BIAS, GERNERALIZATION, TRIANGULATION AND REFLEXIVITY.

1.22k views • 30 slides

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research. Qualitative Research is an umbrella covering several forms of inquiry that help us understand and explain the meaning of social phenomena with as little disruption to the natural setting as possible.

1.25k views • 76 slides

Narrative methods in qualitative and quantitative research

Narrative methods in qualitative and quantitative research. 22 nd February 2006 Combining social research methods, data and analyses Jane Elliott Centre for Longitudinal Studies Institute of Education. Main themes of workshop session.

524 views • 19 slides

Quantitative and Qualitative methods in Library Research

Quantitative and Qualitative methods in Library Research. Amy Catalano, Ed.D ., MLS, MALS Associate Professor of Library Services, Hofstra University. Library Research. Library research tends to be rather poor.

628 views • 31 slides

Quantitative and Qualitative research

Quantitative and Qualitative research. Quantitative Research. Qualitative Research?. A type of educational research in which the researcher decides what to study. A type of educational research in which the researcher relies on the views of the participants.

1.39k views • 25 slides

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research. AMA Collegiate Marketing Research Certificate Program. Module Objectives. Qualitative and quantitative data offer different problem solving opportunities

741 views • 26 slides

Qualitative vs Quantitative research & Multilevel methods

Qualitative vs Quantitative research & Multilevel methods. How to include context in your research April 2005 Marjolein Deunk. Content. What is qualitative analysis and how does it differ from quantitative analysis? How to combine qualitative and quantitative research?

806 views • 38 slides

Qualitative and Quantitative Research Designs

Qualitative and Quantitative Research Designs. Social Research Methods 2117 & 6501 Fall, 2006 October 25-30, 2006. Overview of Research Design. Research Purposes Exploration ( 探索 ), Description ( 描述 ), Explanation ( 解釋 ) Units of Analysis ( 研究單位 ): possibly individuals ( 個人 )

674 views • 18 slides

Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Learning Objectives Explore the differences between quantitative and qualitative data. Outcomes C and below (Knowledge only) Explain the differences between quantitative and qualitative data Explain what an observational study is

1.7k views • 9 slides

Qualitative Research Methods. Mary H. Hayden, PhD NCAR Summer WAS*IS July 20, 2006. Presentation Outline. Distinguishing qualitative and quantitative approaches Qualitative methods – Types of qualitative methods Advantages vs. Disadvantages Real World Examples.

818 views • 39 slides

Sampling Methods in Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Sampling Methods in Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Sampling. Sampling in Quantitative Research. Sampling in Quantitative Research. Population The entire aggregation of cases that meets a specified set of criteria Eligibility criteria determines the attributes of the target population

353 views • 30 slides

RESEARCH DESIGN: Qualitative and quantITATIVE

RESEARCH DESIGN: Qualitative and quantITATIVE. BUSN 364 – Week 6 Özge Can. Research Activities:. Read article: “Bilim Ortamı Olmadan Bilim Olmaz” by Dogan Kuban Available at Course webpage – Reading Materials Read article: “Science in America: Decline and Fall”

470 views • 39 slides

Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

Quantitative and Qualitative Methods. Sebastian M. Rasinger Research Methods in Linguistics. An Introduction. Second Edition London: Bloomsbury. Agenda. Pros and cons of questionnaire use Design Coding. Questionnaires - Basics.

362 views • 22 slides

Quantitative Deductive: transforms general theory into hypothesis suitable for testing Objective Sample represents the whole population so that results can be generalized. Qualitative Inductive: inductive thought which transforms specific observations into general theory Subjective

665 views • 5 slides

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Qualitative And Quantitative Research Methods | Simplilearn

This presentation will help you learn the significant differences between qualitative and quantitative research. You will understand what they are and when to use qualitative and quantitative research methods. You will get an idea about their research approach and the scientific methods used. Finally, we'll look at how to analyze data using these methods and see the final report. 1. What is it? 2. When to Use? 3. Data Collection 4. Research Approach 5. Research Samples 6. Role of Researcher 7. Scientific Method 8. Analyzing Data 9. Final Report What are the learning objectives? Simplilearnu2019s Data Analyst Master's Program developed in collaboration with IBM will provide you with extensive expertise in the booming data analytics field. This data analytics certification training course will teach you how to master descriptive and inferential statistics, hypothesis testing, regression analysis, data blending, data extracts, and forecasting. Through this course, you will also gain expertise in data visualization techniques using Tableau and Power BI, learning how to organize data and design dashboards. In this data analyst certification online course, a special emphasis is placed on those currently employed in the non-technical workforce. Through this Data Analytics course, those with a basic understanding of mathematical concepts will be able to complete the course and become an expert in data analytics. This learning experience melds the knowledge of Data Analytics with hands-on demos and projects via CloudLab. Upon completing this course, you will have all the skills required to become a successful data analyst. Why become Data Analyst? By 2020, the World Economic Forum forecasts that data analysts will be in demand due to increasing data collection and usage. Organizations view data analysis as one of the most crucial future specialties due to the value that can be derived from data. Data is more abundant and accessible than ever in todayu2019s business environment. In fact, 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created each day. With an ever-increasing skill gap in data analytics, the value of data analysts is continuing to grow, creating a new job and career advancement opportunities. The facts are that professionals who enter the Data Science field will have their pick of jobs and enjoy lucrative salaries. According to an IBM report, data and analytics jobs are predicted to increase by 15 percent to 2.72 million jobs by 2020, with the most significant demand for data analysts in finance, insurance, and information technology. Data analysts earn an average pay of $67,377 in 2019 according to Glassdoor. Who should take up this course? Aspiring professionals of any educational background with an analytical frame of mind are best suited to pursue the Data Analyst Masteru2019s Program, including: 1. IT professionals 2. Banking and finance professionals 3. Marketing managers 4. Sales professionals 5. Supply chain network managers 6. Beginners in the data analytics domain 7. Students in UG/ PG programs ud83dudc49Learn more at: https://bit.ly/2SECA5r

442 views • 14 slides

![quantitative research methods slideshare [PDF DOWNLOAD] Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods](https://cdn5.slideserve.com/10147803/welcome-to-my-slide-now-you-read-research-design-dt.jpg)

[PDF DOWNLOAD] Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods

"Free P.D.F e_Book D.ownload and Rea.d Online Author : John W. Creswell Format : ===>Ebook magazine downloads<==== Click This Link To Download : https://wemblee1234.blogspot.com/?book=1506386709 (Works on PC, iPad, Android, iOS, Tablet, MAC) Synopsis: This bestselling text pioneered the comparison of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods research design. For all three approaches, John W. Creswell and new co-author J. David Creswell include a preliminary consideration of philosophical assumptions; key elements of the research process; a review of the literature; an assessment of the use of theory in research applications, and reflections about the importance of writing and ethics in scholarly inquiry. New to this EditionUpdated discussion on designing a proposal for a research project and on the steps in designing a research study. Additional content on epistemological and ontological positioning in relation to the research question and chosen methodology and method. Additional updates on the transformative worldview. Expanded coverage on specific approaches such as case studies, participatory action research, and visual methods. Additional information about social media, online qualitative methods, and mentoring and "

235 views • 19 slides

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods

Published by Logan Singleton Modified over 8 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods"— Presentation transcript:

Chapter 22 Evaluating a Research Report Gay, Mills, and Airasian

The Robert Gordon University School of Engineering Dr. Mohamed Amish

Research Methods in Crime and Justice

Brief Overview of Qualitative & Quantitative Research.

Modes of Enquiry A Comparison of the Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches.

Methodology A preview. What is Methodology Choosing a method of data collection Structure of the research Builds on and draws from problem statement.

Observing Behavior A nonexperimental approach. QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE APPROACHES Quantitative Focuses on specific behaviors that can be easily quantified.

Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Reporting

Introduction to Qualitative Research

Chapter 3 Preparing and Evaluating a Research Plan Gay and Airasian

Copyright c 2001 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.1 Chapter 4 Introduction to Qualitative Research Effective in capturing complexity of communication phenomena.

Lecture 2 Research Questions: Defining and Justifying Problems; Defining Hypotheses.

Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches

Outline: Research Methodology: Case Study - what is case study

Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches Dr. William M. Bauer

Qualitative vs. Quantitative QUANTITATIVE Hypothesis: All beans are alike. NULL: No beans are different. Method: Count the beans. QUALITATIVE Question:

QUANTITATIVE & QUALITATIVE RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCE NGUYEN THU QUYNH – I34035 Introduction to International Relations.

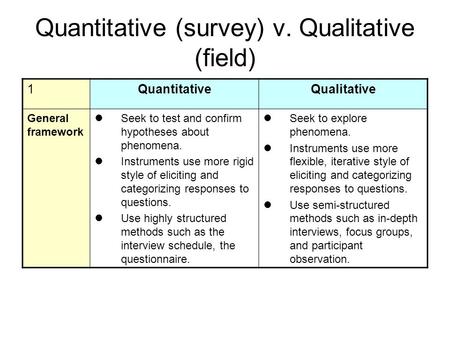

Quantitative (survey) v. Qualitative (field) 1QuantitativeQualitative General framework Seek to test and confirm hypotheses about phenomena. Instruments.

Introduction to Theory & Research Design

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Chapter 20. Presentations

Introduction.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? If a qualitative study is conducted, but it is not presented (in words or text), did it really happen? Perhaps not. Findings from qualitative research are inextricably tied up with the way those findings are presented. These presentations do not always need to be in writing, but they need to happen. Think of ethnographies, for example, and their thick descriptions of a particular culture. Witnessing a culture, taking fieldnotes, talking to people—none of those things in and of themselves convey the culture. Or think about an interview-based phenomenological study. Boxes of interview transcripts might be interesting to read through, but they are not a completed study without the intervention of hours of analysis and careful selection of exemplary quotes to illustrate key themes and final arguments and theories. And unlike much quantitative research in the social sciences, where the final write-up neatly reports the results of analyses, the way the “write-up” happens is an integral part of the analysis in qualitative research. Once again, we come back to the messiness and stubborn unlinearity of qualitative research. From the very beginning, when designing the study, imagining the form of its ultimate presentation is helpful.

Because qualitative researchers are motivated by understanding and conveying meaning, effective communication is not only an essential skill but a fundamental facet of the entire research project. Ethnographers must be able to convey a certain sense of verisimilitude, the appearance of true reality. Those employing interviews must faithfully depict the key meanings of the people they interviewed in a way that rings true to those people, even if the end result surprises them. And all researchers must strive for clarity in their publications so that various audiences can understand what was found and why it is important. This chapter will address how to organize various kinds of presentations for different audiences so that your results can be appreciated and understood.

In the world of academic science, social or otherwise, the primary audience for a study’s results is usually the academic community, and the primary venue for communicating to this audience is the academic journal. Journal articles are typically fifteen to thirty pages in length (8,000 to 12,000 words). Although qualitative researchers often write and publish journal articles—indeed, there are several journals dedicated entirely to qualitative research [1] —the best writing by qualitative researchers often shows up in books. This is because books, running from 80,000 to 150,000 words in length, allow the researcher to develop the material fully. You have probably read some of these in various courses you have taken, not realizing what they are. I have used examples of such books throughout this text, beginning with the three profiles in the introductory chapter. In some instances, the chapters in these books began as articles in academic journals (another indication that the journal article format somewhat limits what can be said about the study overall).

While the article and the book are “final” products of qualitative research, there are actually a few other presentation formats that are used along the way. At the very beginning of a research study, it is often important to have a written research proposal not just to clarify to yourself what you will be doing and when but also to justify your research to an outside agency, such as an institutional review board (IRB; see chapter 12), or to a potential funder, which might be your home institution, a government funder (such as the National Science Foundation, or NSF), or a private foundation (such as the Gates Foundation). As you get your research underway, opportunities will arise to present preliminary findings to audiences, usually through presentations at academic conferences. These presentations can provide important feedback as you complete your analyses. Finally, if you are completing a degree and looking to find an academic job, you will be asked to provide a “job talk,” usually about your research. These job talks are similar to conference presentations but can run significantly longer.

All the presentations mentioned so far are (mostly) for academic audiences. But qualitative research is also unique in that many of its practitioners don’t want to confine their presentation only to other academics. Qualitative researchers who study particular contexts or cultures might want to report back to the people and places they observed. Those working in the critical tradition might want to raise awareness of a particular issue to as large an audience as possible. Many others simply want everyday, nonacademic people to read their work, because they think it is interesting and important. To reach a wide audience, the final product can look like almost anything—it can be a poem, a blog, a podcast, even a science fiction short story. And if you are very lucky, it can even be a national or international bestseller.

In this chapter, we are going to stick with the more basic quotidian presentations—the academic paper / research proposal, the conference slideshow presentation / job talk, and the conference poster. We’ll also spend a bit of time on incorporating universal design into your presentations and how to create some especially attractive and impactful visual displays.

Researcher Note

What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given about conducting qualitative research?

The best advice I’ve received came from my adviser, Alford Young Jr. He told me to find the “Jessi Streib” answer to my research question, not the “Pierre Bourdieu” answer to my research question. In other words, don’t just say how a famous theorist would answer your question; say something original, something coming from you.

—Jessi Streib, author of The Power of the Past and Privilege Lost

Writing about Your Research

The journal article and the research proposal.

Although the research proposal is written before you have actually done your research and the article is written after all data collection and analysis is complete, there are actually many similarities between the two in terms of organization and purpose. The final article will (probably—depends on how much the research question and focus have shifted during the research itself) incorporate a great deal of what was included in a preliminary research proposal. The average lengths of both a proposal and an article are quite similar, with the “front sections” of the article abbreviated to make space for the findings, discussion of findings, and conclusion.

Figure 20.1 shows one model for what to include in an article or research proposal, comparing the elements of each with a default word count for each section. Please note that you will want to follow whatever specific guidelines you have been provided by the venue you are submitting the article/proposal to: the IRB, the NSF, the Journal of Qualitative Research . In fact, I encourage you to adapt the default model as needed by swapping out expected word counts for each section and adding or varying the sections to match expectations for your particular publication venue. [2]

You will notice a few things about the default model guidelines. First, while half of the proposal is spent discussing the research design, this section is shortened (but still included) for the article. There are a few elements that only show up in the proposal (e.g., the limitations section is in the introductory section here—it will be more fully developed in the conclusory section in the article). Obviously, you don’t have findings in the proposal, so this is an entirely new section for the article. Note that the article does not include a data management plan or a timeline—two aspects that most proposals require.

It might be helpful to find and maintain examples of successfully written sections that you can use as models for your own writing. I have included a few of these throughout the textbook and have included a few more at the end of this chapter.

Make an Argument

Some qualitative researchers, particularly those engaged in deep ethnographic research, focus their attention primarily if not exclusively on describing the data. They might even eschew the notion that they should make an “argument” about the data, preferring instead to use thick descriptions to convey interpretations. Bracketing the contrast between interpretation and argument for the moment, most readers will expect you to provide an argument about your data, and this argument will be in answer to whatever research question you eventually articulate (remember, research questions are allowed to shift as you get further into data collection and analysis). It can be frustrating to read a well-developed study with clear and elegant descriptions and no argument. The argument is the point of the research, and if you do not have one, 99 percent of the time, you are not finished with your analysis. Calarco ( 2020 ) suggests you imagine a pyramid, with all of your data forming the basis and all of your findings forming the middle section; the top/point of the pyramid is your argument, “what the patterns in your data tell us about how the world works or ought to work” ( 181 ).

The academic community to which you belong will be looking for an argument that relates to or develops theory. This is the theoretical generalizability promise of qualitative research. An academic audience will want to know how your findings relate to previous findings, theories, and concepts (the literature review; see chapter 9). It is thus vitally important that you go back to your literature review (or develop a new one) and draw those connections in your discussion and/or conclusion. When writing to other audiences, you will still want an argument, although it may not be written as a theoretical one. What do I mean by that? Even if you are not referring to previous literature or developing new theories or adapting older ones, a simple description of your findings is like dumping a lot of leaves in the lap of your audience. They still deserve to know about the shape of the forest. Maybe provide them a road map through it. Do this by telling a clear and cogent story about the data. What is the primary theme, and why is it important? What is the point of your research? [3]

A beautifully written piece of research based on participant observation [and/or] interviews brings people to life, and helps the reader understand the challenges people face. You are trying to use vivid, detailed and compelling words to help the reader really understand the lives of the people you studied. And you are trying to connect the lived experiences of these people to a broader conceptual point—so that the reader can understand why it matters. ( Lareau 2021:259 )

Do not hide your argument. Make it the focal point of your introductory section, and repeat it as often as needed to ensure the reader remembers it. I am always impressed when I see researchers do this well (see, e.g., Zelizer 1996 ).

Here are a few other suggestions for writing your article: Be brief. Do not overwhelm the reader with too many words; make every word count. Academics are particularly prone to “overwriting” as a way of demonstrating proficiency. Don’t. When writing your methods section, think about it as a “recipe for your work” that allows other researchers to replicate if they so wish ( Calarco 2020:186 ). Convey all the necessary information clearly, succinctly, and accurately. No more, no less. [4] Do not try to write from “beginning to end” in that order. Certain sections, like the introductory section, may be the last ones you write. I find the methods section the easiest, so I often begin there. Calarco ( 2020 ) begins with an outline of the analysis and results section and then works backward from there to outline the contribution she is making, then the full introduction that serves as a road map for the writing of all sections. She leaves the abstract for the very end. Find what order best works for you.

Presenting at Conferences and Job Talks

Students and faculty are primarily called upon to publicly present their research in two distinct contexts—the academic conference and the “job talk.” By convention, conference presentations usually run about fifteen minutes and, at least in sociology and other social sciences, rely primarily on the use of a slideshow (PowerPoint Presentation or PPT) presentation. You are usually one of three or four presenters scheduled on the same “panel,” so it is an important point of etiquette to ensure that your presentation falls within the allotted time and does not crowd into that of the other presenters. Job talks, on the other hand, conventionally require a forty- to forty-five-minute presentation with a fifteen- to twenty-minute question and answer (Q&A) session following it. You are the only person presenting, so if you run over your allotted time, it means less time for the Q&A, which can disturb some audience members who have been waiting for a chance to ask you something. It is sometimes possible to incorporate questions during your presentation, which allows you to take the entire hour, but you might end up shorting your presentation this way if the questions are numerous. It’s best for beginners to stick to the “ask me at the end” format (unless there is a simple clarifying question that can easily be addressed and makes the presentation run more smoothly, as in the case where you simply forgot to include information on the number of interviews you conducted).

For slideshows, you should allot two or even three minutes for each slide, never less than one minute. And those slides should be clear, concise, and limited. Most of what you say should not be on those slides at all. The slides are simply the main points or a clear image of what you are speaking about. Include bulleted points (words, short phrases), not full sentences. The exception is illustrative quotations from transcripts or fieldnotes. In those cases, keep to one illustrative quote per slide, and if it is long, bold or otherwise, highlight the words or passages that are most important for the audience to notice. [5]

Figure 20.2 provides a possible model for sections to include in either a conference presentation or a job talk, with approximate times and approximate numbers of slides. Note the importance (in amount of time spent) of both the research design and the findings/results sections, both of which have been helpfully starred for you. Although you don’t want to short any of the sections, these two sections are the heart of your presentation.

Fig 20.2. Suggested Slideshow Times and Number of Slides

Should you write out your script to read along with your presentation? I have seen this work well, as it prevents presenters from straying off topic and keeps them to the time allotted. On the other hand, these presentations can seem stiff and wooden. Personally, although I have a general script in advance, I like to speak a little more informally and engagingly with each slide, sometimes making connections with previous panelists if I am at a conference. This means I have to pay attention to the time, and I sometimes end up breezing through one section more quickly than I would like. Whatever approach you take, practice in advance. Many times. With an audience. Ask for feedback, and pay attention to any presentation issues that arise (e.g., Do you speak too fast? Are you hard to hear? Do you stumble over a particular word or name?).

Even though there are rules and guidelines for what to include, you will still want to make your presentation as engaging as possible in the little amount of time you have. Calarco ( 2020:274 ) recommends trying one of three story structures to frame your presentation: (1) the uncertain explanation , where you introduce a phenomenon that has not yet been fully explained and then describe how your research is tackling this; (2) the uncertain outcome , where you introduce a phenomenon where the consequences have been unclear and then you reveal those consequences with your research; and (3) the evocative example , where you start with some interesting example from your research (a quote from the interview transcripts, for example) or the real world and then explain how that example illustrates the larger patterns you found in your research. Notice that each of these is a framing story. Framing stories are essential regardless of format!

A Word on Universal Design

Please consider accessibility issues during your presentation, and incorporate elements of universal design into your slideshow. The basic idea behind universal design in presentations is that to the greatest extent possible, all people should be able to view, hear, or otherwise take in your presentation without needing special individual adaptations. If you can make your presentation accessible to people with visual impairment or hearing loss, why not do so? For example, one in twelve men is color-blind, unable to differentiate between certain colors, red/green being the most common problem. So if you design a graphic that relies on red and green bars, some of your audience members may not be able to properly identify which bar means what. Simple contrasts of black and white are much more likely to be visible to all members of your audience. There are many other elements of good universal design, but the basic foundation of all of them is that you consider how to make your presentation as accessible as possible at the outset. For example, include captions whenever possible, both as descriptions on slides and as images on slides and for any audio or video clips you are including; keep font sizes large enough to read from the back of the room; and face the audience when you are.

Poster Design

Undergraduate students who present at conferences are often encouraged to present at “poster sessions.” This usually means setting up a poster version of your research in a large hall or convention space at a set period of time—ninety minutes is common. Your poster will be one of dozens, and conference-goers will wander through the space, stopping intermittently at posters that attract them. Those who stop by might ask you questions about your research, and you are expected to be able to talk intelligently for two or three minutes. It’s a fairly easy way to practice presenting at conferences, which is why so many organizations hold these special poster sessions.

A good poster design will be immediately attractive to passersby and clearly and succinctly describe your research methods, findings, and conclusions. Some students have simply shrunk down their research papers to manageable sizes and then pasted them on a poster, all twelve to fifteen pages of them. Don’t do that! Here are some better suggestions: State the main conclusion of your research in large bold print at the top of your poster, on brightly colored (contrasting) paper, and paste in a QR code that links to your full paper online ( Calarco 2020:280 ). Use the rest of the poster board to provide a couple of highlights and details of the study. For an interview-based study, for example, you will want to put in some details about your sample (including number of interviews) and setting and then perhaps one or two key quotes, also distinguished by contrasting color background.

Incorporating Visual Design in Your Presentations

In addition to ensuring that your presentation is accessible to as large an audience as possible, you also want to think about how to display your data in general, particularly how to use charts and graphs and figures. [6] The first piece of advice is, use them! As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words. If you can cut to the chase with a visually stunning display, do so. But there are visual displays that are stunning, and then there are the tired, hard-to-see visual displays that predominate at conferences. You can do better than most presenters by simply paying attention here and committing yourself to a good design. As with model section passages, keep a file of visual displays that work as models for your own presentations. Find a good guidebook to presenting data effectively (Evergreen 2018 , 2019 ; Schwabisch 2021) , and refer to it often.

Let me make a few suggestions here to get you started. First, test every visual display on a friend or colleague to find out how quickly they can understand the point you are trying to convey. As with reading passages aloud to ensure that your writing works, showing someone your display is the quickest way to find out if it works. Second, put the point in the title of the display! When writing for an academic journal, there will be specific conventions of what to include in the title (full description including methods of analysis, sample, dates), but in a public presentation, there are no limiting rules. So you are free to write as your title “Working-Class College Students Are Three Times as Likely as Their Peers to Drop Out of College,” if that is the point of the graphic display. It certainly helps the communicative aspect. Third, use the themes available to you in Excel for creating graphic displays, but alter them to better fit your needs . Consider adding dark borders to bars and columns, for example, so that they appear crisper for your audience. Include data callouts and labels, and enlarge them so they are clearly visible. When duplicative or otherwise unnecessary, drop distracting gridlines and labels on the y-axis (the vertical one). Don’t go crazy adding different fonts, however—keep things simple and clear. Sans serif fonts (those without the little hooks on the ends of letters) read better from a distance. Try to use the same color scheme throughout, even if this means manually changing the colors of bars and columns. For example, when reporting on working-class college students, I use blue bars, while I reserve green bars for wealthy students and yellow bars for students in the middle. I repeat these colors throughout my presentations and incorporate different colors when talking about other items or factors. You can also try using simple grayscale throughout, with pops of color to indicate a bar or column or line that is of the most interest. These are just some suggestions. The point is to take presentation seriously and to pay attention to visual displays you are using to ensure they effectively communicate what you want them to communicate. I’ve included a data visualization checklist from Evergreen ( 2018 ) here.

Ethics of Presentation and Reliability

Until now, all the data you have collected have been yours alone. Once you present the data, however, you are sharing sometimes very intimate information about people with a broader public. You will find yourself balancing between protecting the privacy of those you’ve interviewed and observed and needing to demonstrate the reliability of the study. The more information you provide to your audience, the more they can understand and appreciate what you have found, but this also may pose risks to your participants. There is no one correct way to go about finding the right balance. As always, you have a duty to consider what you are doing and must make some hard decisions.

The most obvious place we see this paradox emerge is when you mask your data to protect the privacy of your participants. It is standard practice to provide pseudonyms, for example. It is such standard practice that you should always assume you are being given a pseudonym when reading a book or article based on qualitative research. When I was a graduate student, I tried to find information on how best to construct pseudonyms but found little guidance. There are some ethical issues here, I think. [7] Do you create a name that has the same kind of resonance as the original name? If the person goes by a nickname, should you use a nickname as a pseudonym? What about names that are ethnically marked (as in, almost all of them)? Is there something unethical about reracializing a person? (Yes!) In her study of adolescent subcultures, Wilkins ( 2008 ) noted, “Because many of the goths used creative, alternative names rather than their given names, I did my best to reproduce the spirit of their chosen names” ( 24 ).

Your reader or audience will want to know all the details about your participants so that they can gauge both your credibility and the reliability of your findings. But how many details are too many? What if you change the name but otherwise retain all the personal pieces of information about where they grew up, and how old they were when they got married, and how many children they have, and whether they made a splash in the news cycle that time they were stalked by their ex-boyfriend? At some point, those details are going to tip over into the zone of potential unmasking. When you are doing research at one particular field site that may be easily ascertained (as when you interview college students, probably at the institution at which you are a student yourself), it is even more important to be wary of providing too many details. You also need to think that your participants might read what you have written, know things about the site or the population from which you drew your interviews, and figure out whom you are talking about. This can all get very messy if you don’t do more than simply pseudonymize the people you interviewed or observed.

There are some ways to do this. One, you can design a study with all of these risks in mind. That might mean choosing to conduct interviews or observations at multiple sites so that no one person can be easily identified. Another is to alter some basic details about your participants to protect their identity or to refuse to provide all the information when selecting quotes . Let’s say you have an interviewee named “Anna” (a pseudonym), and she is a twenty-four-year-old Latina studying to be an engineer. You want to use a quote from Anna about racial discrimination in her graduate program. Instead of attributing the quote to Anna (whom your reader knows, because you’ve already told them, is a twenty-four-year-old Latina studying engineering), you might simply attribute the quote to “Latina student in STEM.” Taking this a step further, you might leave the quote unattributed, providing a list of quotes about racial discrimination by “various students.”

The problem with masking all the identifiers, of course, is that you lose some of the analytical heft of those attributes. If it mattered that Anna was twenty-four (not thirty-four) and that she was a Latina and that she was studying engineering, taking out any of those aspects of her identity might weaken your analysis. This is one of those “hard choices” you will be called on to make! A rather radical and controversial solution to this dilemma is to create composite characters , characters based on the reality of the interviews but fully masked because they are not identifiable with any one person. My students are often very queasy about this when I explain it to them. The more positivistic your approach and the more you see individuals rather than social relationships/structure as the “object” of your study, the more employing composites will seem like a really bad idea. But composites “allow researchers to present complex, situated accounts from individuals” without disclosing personal identities ( Willis 2019 ), and they can be effective ways of presenting theory narratively ( Hurst 2019 ). Ironically, composites permit you more latitude when including “dirty laundry” or stories that could harm individuals if their identities became known. Rather than squeezing out details that could identify a participant, the identities are permanently removed from the details. Great difficulty remains, however, in clearly explaining the theoretical use of composites to your audience and providing sufficient information on the reliability of the underlying data.

There are a host of other ethical issues that emerge as you write and present your data. This is where being reflective throughout the process will help. How and what you share of what you have learned will depend on the social relationships you have built, the audiences you are writing or speaking to, and the underlying animating goals of your study. Be conscious about all of your decisions, and then be able to explain them fully, both to yourself and to those who ask.

Our research is often close to us. As a Black woman who is a first-generation college student and a professional with a poverty/working-class origin, each of these pieces of my identity creates nuances in how I engage in my research, including how I share it out. Because of this, it’s important for us to have people in our lives who we trust who can help us, particularly, when we are trying to share our findings. As researchers, we have been steeped in our work, so we know all the details and nuances. Sometimes we take this for granted, and we might not have shared those nuances in conversation or writing or taken some of this information for granted. As I share my research with trusted friends and colleagues, I pay attention to the questions they ask me or the feedback they give when we talk or when they read drafts.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

Final Comments: Preparing for Being Challenged

Once you put your work out there, you must be ready to be challenged. Science is a collective enterprise and depends on a healthy give and take among researchers. This can be both novel and difficult as you get started, but the more you understand the importance of these challenges, the easier it will be to develop the kind of thick skin necessary for success in academia. Scientists’ authority rests on both the inherent strength of their findings and their ability to convince other scientists of the reliability and validity and value of those findings. So be prepared to be challenged, and recognize this as simply another important aspect of conducting research!

Considering what challenges might be made as you design and conduct your study will help you when you get to the writing and presentation stage. Address probable challenges in your final article, and have a planned response to probable questions in a conference presentation or job talk. The following is a list of common challenges of qualitative research and how you might best address them:

- Questions about generalizability . Although qualitative research is not statistically generalizable (and be prepared to explain why), qualitative research is theoretically generalizable. Discuss why your findings here might tell us something about related phenomena or contexts.

- Questions about reliability . You probably took steps to ensure the reliability of your findings. Discuss them! This includes explaining the use and value of multiple data sources and defending your sampling and case selections. It also means being transparent about your own position as researcher and explaining steps you took to ensure that what you were seeing was really there.

- Questions about replicability. Although qualitative research cannot strictly be replicated because the circumstances and contexts will necessarily be different (if only because the point in time is different), you should be able to provide as much detail as possible about how the study was conducted so that another researcher could attempt to confirm or disconfirm your findings. Also, be very clear about the limitations of your study, as this allows other researchers insight into what future research might be warranted.

None of this is easy, of course. Writing beautifully and presenting clearly and cogently require skill and practice. If you take anything from this chapter, it is to remember that presentation is an important and essential part of the research process and to allocate time for this as you plan your research.

Data Visualization Checklist for Slideshow (PPT) Presentations

Adapted from Evergreen ( 2018 )

Text checklist

- Short catchy, descriptive titles (e.g., “Working-class students are three times as likely to drop out of college”) summarize the point of the visual display

- Subtitled and annotations provide additional information (e.g., “note: male students also more likely to drop out”)

- Text size is hierarchical and readable (titles are largest; axes labels smallest, which should be at least 20points)

- Text is horizontal. Audience members cannot read vertical text!

- All data labeled directly and clearly: get rid of those “legends” and embed the data in your graphic display

- Labels are used sparingly; avoid redundancy (e.g., do not include both a number axis and a number label)

Arrangement checklist

- Proportions are accurate; bar charts should always start at zero; don’t mislead the audience!

- Data are intentionally ordered (e.g., by frequency counts). Do not leave ragged alphabetized bar graphs!

- Axis intervals are equidistant: spaces between axis intervals should be the same unit

- Graph is two-dimensional. Three-dimensional and “bevelled” displays are confusing

- There is no unwanted decoration (especially the kind that comes automatically through the PPT “theme”). This wastes your space and confuses.

Color checklist

- There is an intentional color scheme (do not use default theme)

- Color is used to identify key patterns (e.g., highlight one bar in red against six others in greyscale if this is the bar you want the audience to notice)

- Color is still legible when printed in black and white

- Color is legible for people with color blindness (do not use red/green or yellow/blue combinations)

- There is sufficient contrast between text and background (black text on white background works best; be careful of white on dark!)

Lines checklist

- Be wary of using gridlines; if you do, mute them (grey, not black)

- Allow graph to bleed into surroundings (don’t use border lines)

- Remove axis lines unless absolutely necessary (better to label directly)

Overall design checklist

- The display highlights a significant finding or conclusion that your audience can ‘”see” relatively quickly

- The type of graph (e.g., bar chart, pie chart, line graph) is appropriate for the data. Avoid pie charts with more than three slices!

- Graph has appropriate level of precision; if you don’t need decimal places

- All the chart elements work together to reinforce the main message

Universal Design Checklist for Slideshow (PPT) Presentations

- Include both verbal and written descriptions (e.g., captions on slides); consider providing a hand-out to accompany the presentation

- Microphone available (ask audience in back if they can clearly hear)

- Face audience; allow people to read your lips

- Turn on captions when presenting audio or video clips

- Adjust light settings for visibility

- Speak slowly and clearly; practice articulation; don’t mutter or speak under your breath (even if you have something humorous to say – say it loud!)

- Use Black/White contrasts for easy visibility; or use color contrasts that are real contrasts (do not rely on people being able to differentiate red from green, for example)

- Use easy to read font styles and avoid too small font sizes: think about what an audience member in the back row will be able to see and read.

- Keep your slides simple: do not overclutter them; if you are including quotes from your interviews, take short evocative snippets only, and bold key words and passages. You should also read aloud each passage, preferably with feeling!

Supplement: Models of Written Sections for Future Reference

Data collection section example.

Interviews were semi structured, lasted between one and three hours, and took place at a location chosen by the interviewee. Discussions centered on four general topics: (1) knowledge of their parent’s immigration experiences; (2) relationship with their parents; (3) understanding of family labor, including language-brokering experiences; and (4) experiences with school and peers, including any future life plans. While conducting interviews, I paid close attention to respondents’ nonverbal cues, as well as their use of metaphors and jokes. I conducted interviews until I reached a point of saturation, as indicated by encountering repeated themes in new interviews (Glaser and Strauss 1967). Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed with each interviewee’s permission, and conducted in accordance with IRB protocols. Minors received permission from their parents before participation in the interview. ( Kwon 2022:1832 )

Justification of Case Selection / Sample Description Section Example

Looking at one profession within one organization and in one geographic area does impose limitations on the generalizability of our findings. However, it also has advantages. We eliminate the problem of interorganizational heterogeneity. If multiple organizations are studied simultaneously, it can make it difficult to discern the mechanisms that contribute to racial inequalities. Even with a single occupation there is considerable heterogeneity, which may make understanding how organizational structure impacts worker outcomes difficult. By using the case of one group of professionals in one religious denomination in one geographic region of the United States, we clarify how individuals’ perceptions and experiences of occupational inequality unfold in relation to a variety of observed and unobserved occupational and contextual factors that might be obscured in a larger-scale study. Focusing on a specific group of professionals allows us to explore and identify ways that formal organizational rules combine with informal processes to contribute to the persistence of racial inequality. ( Eagle and Mueller 2022:1510–1511 )

Ethics Section Example

I asked everyone who was willing to sit for a formal interview to speak only for themselves and offered each of them a prepaid Visa Card worth $25–40. I also offered everyone the opportunity to keep the card and erase the tape completely at any time they were dissatisfied with the interview in any way. No one asked for the tape to be erased; rather, people remarked on the interview being a really good experience because they felt heard. Each interview was professionally transcribed and for the most part the excerpts are literal transcriptions. In a few places, the excerpts have been edited to reduce colloquial features of speech (e.g., you know, like, um) and some recursive elements common to spoken language. A few excerpts were placed into standard English for clarity. I made this choice for the benefit of readers who might otherwise find the insights and ideas harder to parse in the original. However, I have to acknowledge this as an act of class-based violence. I tried to keep the original phrasing whenever possible. ( Pascale 2021:235 )

Further Readings

Calarco, Jessica McCrory. 2020. A Field Guide to Grad School: Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Don’t let the unassuming title mislead you—there is a wealth of helpful information on writing and presenting data included here in a highly accessible manner. Every graduate student should have a copy of this book.

Edwards, Mark. 2012. Writing in Sociology . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. An excellent guide to writing and presenting sociological research by an Oregon State University professor. Geared toward undergraduates and useful for writing about either quantitative or qualitative research or both.

Evergreen, Stephanie D. H. 2018. Presenting Data Effectively: Communicating Your Findings for Maximum Impact . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is one of my very favorite books, and I recommend it highly for everyone who wants their presentations and publications to communicate more effectively than the boring black-and-white, ragged-edge tables and figures academics are used to seeing.

Evergreen, Stephanie D. H. 2019. Effective Data Visualization 2 . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is an advanced primer for presenting clean and clear data using graphs, tables, color, font, and so on. Start with Evergreen (2018), and if you graduate from that text, move on to this one.

Schwabisch, Jonathan. 2021. Better Data Visualizations: A Guide for Scholars, Researchers, and Wonks . New York: Columbia University Press. Where Evergreen’s (2018, 2019) focus is on how to make the best visual displays possible for effective communication, this book is specifically geared toward visual displays of academic data, both quantitative and qualitative. If you want to know when it is appropriate to use a pie chart instead of a stacked bar chart, this is the reference to use.

- Some examples: Qualitative Inquiry , Qualitative Research , American Journal of Qualitative Research , Ethnography , Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research , Qualitative Report , Qualitative Sociology , and Qualitative Studies . ↵

- This is something I do with every article I write: using Excel, I write each element of the expected article in a separate row, with one column for “expected word count” and another column for “actual word count.” I fill in the actual word count as I write. I add a third column for “comments to myself”—how things are progressing, what I still need to do, and so on. I then use the “sum” function below each of the first two columns to keep a running count of my progress relative to the final word count. ↵

- And this is true, I would argue, even when your primary goal is to leave space for the voices of those who don’t usually get a chance to be part of the conversation. You will still want to put those voices in some kind of choir, with a clear direction (song) to be sung. The worst thing you can do is overwhelm your audience with random quotes or long passages with no key to understanding them. Yes, a lot of metaphors—qualitative researchers love metaphors! ↵

- To take Calarco’s recipe analogy further, do not write like those food bloggers who spend more time discussing the color of their kitchen or the experiences they had at the market than they do the actual cooking; similarly, do not write recipes that omit crucial details like the amount of flour or the size of the baking pan used or the temperature of the oven. ↵

- The exception is the “compare and contrast” of two or more quotes, but use caution here. None of the quotes should be very long at all (a sentence or two each). ↵

- Although this section is geared toward presentations, many of the suggestions could also be useful when writing about your data. Don’t be afraid to use charts and graphs and figures when writing your proposal, article, thesis, or dissertation. At the very least, you should incorporate a tabular display of the participants, sites, or documents used. ↵

- I was so puzzled by these kinds of questions that I wrote one of my very first articles on it ( Hurst 2008 ). ↵

The visual presentation of data or information through graphics such as charts, graphs, plots, infographics, maps, and animation. Recall the best documentary you ever viewed, and there were probably excellent examples of good data visualization there (for me, this was An Inconvenient Truth , Al Gore’s film about climate change). Good data visualization allows more effective communication of findings of research, particularly in public presentations (e.g., slideshows).

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

In this lecture, delivered at Seacom Skills University, I have discussed qualitative and quantitative research.The lecture will be useful to students of social sciences.

Related Papers

Tshidi M Wyllie

To accumulate a body of knowledge which can inform and improve socio-economic and political human existence requires evidence-based approaches, as such, conducting scientific researches is usually carried out to find solutions to a prevailing phenomenon; therefore, extracting and accumulating such a scientific knowledge and/or information is a crucial process. In this endeavour, researchers usually deploy various scientific approaches and methods; methods which are mostly informed by ontological and epistemological underpinnings. In discussing quantitative and qualitative research approaches and drawing distinction between the two approaches this paper will explain the three major dimensions considered critical in research process

iosrjournals.org

Munyaradzi Moyo

International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM)

Ernest Negou

The objective of this study is to provide a guide to qualitative research methodology in social sciences. It is the result of the observation that research in Management Sciences in most Universities in Cameroon is still dominated by the quantitative approach supported by economists who handle most research methodology courses. In an environment of oral tradition and the difficulties to have access to data, emphasising purely quantitative research may leave aside many aspects of the environment and several areas of human behaviour that make its specificities. Therefore, there is a need to generalise the use of qualitative research to enable researchers to always have a good insight into phenomena not yet clarified before thinking of any generalisation which is the main objective of quantitative research: this gives room to the contextualisation of research which results can easily be applied in its context, thus, enhancing development.

Kirathe Wanjiku

Tracie Seidelman

Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum Qualitative Social Research

Margrit Schreier

M.Lib.I.Sc. Project, Panjab University, under guidance of Dr. Shiv Kumar

SUBHAJIT PANDA

There's no hard and fast rule for qualitative versus quantitative research, and it's often taken for granted. It is claimed here that the divide between qualitative and quantitative research is ambiguous, incoherent, and hence of little value, and that its widespread use could have negative implications. This conclusion is supported by a variety of arguments. Qualitative researchers, for example, have varying perspectives on fundamental problems (such as the use of quantification and causal analysis), which makes the difference as such shaky. In addition, many elements of qualitative and quantitative research overlap significantly, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. Practically in the case of field research, the Qualitative and quantitative approach can't be distinguished clearly as the study pointed. The distinction may limit innovation in the development of new research methodologies, as well as cause complication and wasteful activity. As a general rule, it may be desirable not to conceptualise research approaches at such abstract levels as are done in the context of qualitative or quantitative methodologies. Discussions of the benefits and drawbacks of various research methods, rather than general research questions, are recommended.

IRJET Journal

Research design methods, such as qualitative, quantitative as well as mixed methods were introduced and subsequently each method was discussed in detail with the help of literature review as well as some personal and live examples to substantiate the findings of various literature. From various literature as well as from the own experiences, it is concluded that both qualitative research design method and quantitative research design method are equally important. It is not fair to criticize one method as the researcher is inclined towards the other method. It is practically evidenced that usage of both methods in the research, the researcher can substantiate the case better. However, duration part while using mixed methods to be kept in mind as it will take more time compared to the qualitative and quantitative methods. Hurrying and aborting in the middle due to time constraint ultimately result in poor research. It would be better if the world view towards these methods changes from criticizing mode to effective utilization mode, which will help research community in focusing and bring up better research outcomes rather than wasting time in arguing which method is scientifically acceptable and which method is biased. While I agree that the ontological, epistemological, axiological, and methodological assumptions for qualitative research method and quantitative research method, researchers should know fully about these methods and keep them as effective tools to utilize them in mixed mode, wherever it is appropriate and required to arrive at adequate research findings.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Human Immunology

Aleksandar Petlichkovski

Cancer/Radiothérapie

Aymeri Huchet

IMISCOE Research Series

Karmela Barišić

Irene Checa-Garcia

The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience

Lila Davachi

BioMed Research International

Marta Martínez-júlvez

vongani ntimane

Akuatika Indonesia

Asep Sahidin

maria rosaria lauro

Vusi Mshayisa

Marcelo Hiroshi Hirakuri

Optical Engineering

Jaehyun Jung

Gelson Silva