Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Research articles

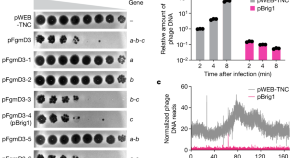

DNA glycosylases provide antiviral defence in prokaryotes

A screen utilizing an environmental DNA library in Escherichia coli is used to identify Brig1, a previously unknown anti-phage defence system with homologues across distinct clades of bacteria.

- Amer A. Hossain

- Ying Z. Pigli

- Luciano A. Marraffini

Hybrid speciation driven by multilocus introgression of ecological traits

Genomic studies of Heliconius butterflies provide evidence that Heliconius elevatus is a hybrid species, and that its speciation was driven by introgression of traits from Heliconius melpomene into the other parent, an ancestor of Heliconius pardalinus .

- Neil Rosser

- Fernando Seixas

- Kanchon K. Dasmahapatra

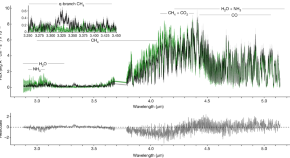

Methane emission from a cool brown dwarf

Methane emission from a very cool brown dwarf, perhaps arising from an aurora, has been detected in James Webb Space Telescope observations.

- Jacqueline K. Faherty

- Ben Burningham

- Niall Whiteford

Stepwise activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor

We propose a model for a sequential, multistep activation mechanism of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5, including a series of structures in lipid nanodiscs, from inactive to fully active, with agonist-bound intermediate states.

- Kaavya Krishna Kumar

- Haoqing Wang

- Brian K. Kobilka

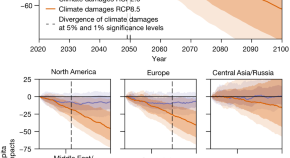

The economic commitment of climate change

Analysis of projected sub-national damages from temperature and precipitation show an income reduction of 19% of the world economy within the next 26 years independent of future emission choices.

- Maximilian Kotz

- Anders Levermann

- Leonie Wenz

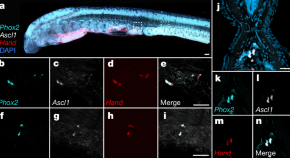

Neural crest origin of sympathetic neurons at the dawn of vertebrates

Challenging the belief that sympathetic ganglia are an innovation of jawed vertebrates, a study reports the presence of sympathetic neurons in an extant jawless vertebrate, the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus .

- Brittany M. Edens

- Marianne E. Bronner

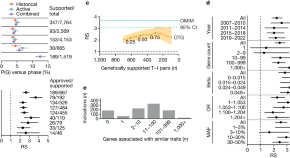

Refining the impact of genetic evidence on clinical success

Human genetic evidence increases the success rate of drugs from clinical development to approval but we are still far from reaching peak genetic insights to aid the discovery of targets for more effective drugs.

- Eric Vallabh Minikel

- Jeffery L. Painter

- Matthew R. Nelson

Seismological evidence for a multifault network at the subduction interface

Using observations of double-difference relocated earthquakes in a local three-dimensional velocity model for Ecuador, a detailed image of seismicity is created, forming the base for more realistic models of earthquake rupture, slip and hazard in subduction zones.

- Caroline Chalumeau

- Hans Agurto-Detzel

- Audrey Galve

Biogeographic response of marine plankton to Cenozoic environmental changes

Analysis of a global dataset reveals spatiotemporal patterns of marine plankton and their biogeographical responses during climatic and environmental changes across the Cenozoic era.

- Anshuman Swain

- Adam Woodhouse

- Christopher M. Lowery

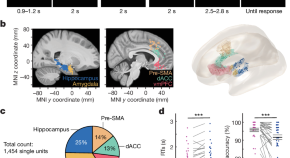

Control of working memory by phase–amplitude coupling of human hippocampal neurons

Hippocampal theta–gamma phase–amplitude coupling integrates cognitive control and working memory storage across brain areas in humans.

- Jonathan Daume

- Jan Kamiński

- Ueli Rutishauser

Network-level encoding of local neurotransmitters in cortical astrocytes

A study investigates subcellular, single-cell and network-level comunication within the astrocyte network in response to the two major neurotransmitter inputs.

- Michelle K. Cahill

- Max Collard

- Kira E. Poskanzer

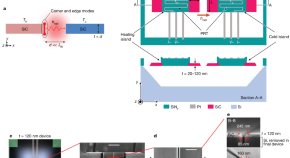

Corner- and edge-mode enhancement of near-field radiative heat transfer

Near-field radiative heat transfer between two coplanar silicon carbide membranes in close proximity is enhanced by the electromagnetic corner and edge modes.

- Lívia M. Corrêa

- Chris Dames

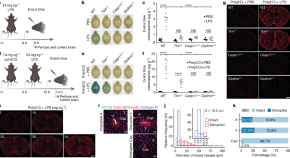

Brain endothelial GSDMD activation mediates inflammatory BBB breakdown

Lipopolysaccharide-induced breakdown of the blood–brain barrier requires activation of GSDMD-mediated plasma membrane permeabilization and pyroptosis in brain endothelial cells.

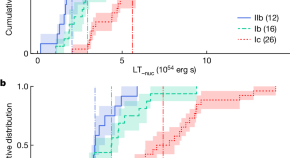

Stripped-envelope supernova light curves argue for central engine activity

Analysis of the energy budget of a sample of 54 well-observed stripped-envelope supernovae of all sub-types shows statistically significant, largely model-independent, observational evidence for a non-radioactive power source in most of them.

- Ósmar Rodríguez

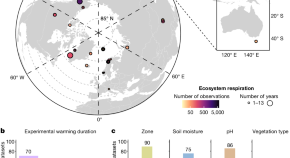

Environmental drivers of increased ecosystem respiration in a warming tundra

Datasets from in situ warming experiments across 28 arctic and alpine tundra sites covering a span of less than 1 year up to 25 years show the importance of local soil conditions and warming-induced changes therein for future climatic impacts on ecosystem respiration.

- J. Dietrich

- E. Dorrepaal

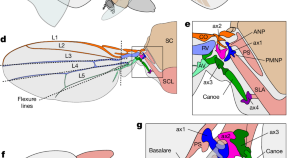

Machine learning reveals the control mechanics of an insect wing hinge

Measurements of fly muscle activity using a genetically encoded calcium indicator and high-speed imaging of wing movement were used to construct a model of the insect wing hinge and the role of steering muscles in flight control.

- Johan M. Melis

- Igor Siwanowicz

- Michael H. Dickinson

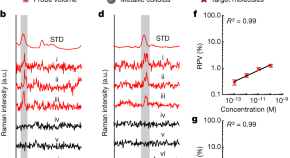

Digital colloid-enhanced Raman spectroscopy by single-molecule counting

Research published in Nature shows that surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy carried out with colloids can quantify a range of molecules down to concentrations at the femtomolar level.

- Daniel M. Czajkowsky

Streptomyces umbrella toxin particles block hyphal growth of competing species

Streptomyces are discovered to produce antibacterial protein complexes that selectively inhibit the hyphal growth of related species, a function distinct from that of the small-molecule antibiotics they are known for.

- Qinqin Zhao

- Savannah Bertolli

- Joseph D. Mougous

Laser spectroscopy of triply charged 229 Th isomer for a nuclear clock

The trapping of triply charged 229m Th 3+ is described and its nuclear decay half-life determined, showing useful properties for the development of a nuclear clock and applications in the search for new physics.

- Atsushi Yamaguchi

- Yudai Shigekawa

- Hidetoshi Katori

Promiscuous G-protein activation by the calcium-sensing receptor

Structures of the human calcium-sensing receptor can be bound into complex with G proteins from three different Gα subtypes while maintaining G-protein-binding specificity.

- Jinseo Park

- Qing R. Fan

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Understanding the Publishing Process

What’s happening with my paper? The publication process explained

The path to publication can be unsettling when you’re unsure what’s happening with your paper. Learn about staple journal workflows to see the detailed steps required for ensuring a rigorous and ethical publication.

Your team has prepared the paper, written a cover letter and completed the submission form. From here, it can sometimes feel like a waiting game while the journal has your paper. It can be unclear exactly who is currently handling your paper as most individuals are only involved in a few steps of the overall process. Journals are responsible for overseeing the peer review, publication and archival process: editors, reviewers, technical editors, production staff and other internal staff all have their roles in ensuring submissions meet rigorous scientific and ethical reporting standards.

Read on for an inside look at how a conventional peer-reviewed journal helps authors transform their initial submission to a certified publication.

Note that the description below is based on the process at PLOS journals. It is likely that at other journals, various roles (e.g. technical editor) may in fact also be played by the editor, and some journals may not have journal staff at all, with all roles played by volunteer academics. As such, please consider the processes and waypoints, rather than who performs them, as the key information.

Internal Checks on New Submissions

Estimated time: 10 days.

When a journal first receives your submission, there are typically two separate checks to confirm that the paper is appropriate and ready for peer review:

- Technical check. Performed by a technical editor to ensure that the submission has been properly completed and is ready for further assessment. Blurry figures, missing ethical statements, and incomplete author affiliations are common issues that are addressed at this initial stage. Typically, there are three technical checks: upon initial submission, alongside the first decision letter, and upon acceptance.

- Editorial screening . Once a paper passes the first check, an editor with subject expertise assesses the paper and determines whether it is within the journal’s scope and if it could potentially meet the required publication criteria. While there may be requests for further information and minor edits from the author as needed, the paper will either be desk rejected by the editor or allowed to proceed to peer review.

Both editors at this point will additionally make notes for items to be followed-up on at later stages. The publication process involves finding a careful balance for when each check occurs. Early checks need to be thorough so that editors with relevant expertise can focus on the scientific content and more advanced reporting standards, but no one wants to be asked to reformat references only to have their paper desk rejected a few days later.

Peer Review

Estimated time: 1 month.

Depending on the journal’s editorial structure, the editor who performed the initial assessment may also oversee peer review or another editor with more specific expertise may be assigned. Regardless of the journal’s specific process, the various roles and responsibilities during peer review include:

When you have questions or are unsure who your manuscripts is currently with, reach out to the journal staff for help (eg. [email protected]). They will be your lifeline, connecting you to all the other contributors working to assess the manuscript.

Whether an editor needs a reminder that all reviews are complete or a reviewer has asked for an extension, the journal acts as a central hub of communication for those involved with the publication process. As editors and reviewers are used to hearing from journal staff about their duties, any messages you send to the journal can be forwarded to them with proper context and instructions on how to proceed appropriately. Additionally, journal staff will be able to inform you of any delays, such as reviewer availability during summer and holiday periods.

Revision Decision

Estimated time: 1 day.

Editors evaluate peer reviewer feedback and their own expert assessment of the manuscript to reach a decision. After your editor submits a decision on your manuscript, the journal may review it before formally processing the decision and sending it on to you.

A technical editor may scan the manuscript and the review comments to ensure that journal standards have been followed. At this stage, the technical editor will also add requests to ensure the paper, if published, will adhere to journal requirements for data sharing, copyright, ethical reporting and the like.

Performing the second technical check at this stage and adding the journal requirements to the decision letter ultimately saves time by allowing authors to resolve the journal’s queries while making revisions based on comments from the reviewers.

Revised Submission Received

Estimated time: 3 days.

Upon receiving your revised submission, a technical editor will assess the revisions to confirm that the requests from the journal have been properly addressed. Before the paper is returned to the editor for their consideration, the journal needs to be confident that the paper won’t have any issues related to the metadata and reporting standards that could prevent publication. The editor may contact you to resolve any serious issues, though minor items can wait until the paper is accepted.

Subsequent Peer Review

Estimated time: 2 weeks, highly variable.

When your resubmitted paper has passed the required checks, it’ll be assigned back to the same editor who handled it during the first round of peer review. At this point, your paper has gone through two sets of journal checks and one round of peer review. If all has gone well so far, the paper should feel quite solid both in terms of scientific content and proper reporting standards.

When the editor receives your revised paper, they are asked to check if all reviewer comments have been adequately addressed and if the paper now adheres to the journal’s publication criteria. Depending on the situation, some editors may feel confident making this decision based on their own expertise while others may re-invite the previous reviewers for their opinions.

Individual responsibilities are the same as the initial round of peer review, but it is generally expected that later stages of peer review proceed quicker unless new concerns have been introduced as part of the revision.

Preliminary Acceptance

Estimated time: 1 week.

Your editor is satisfied with the scientific quality of your work and has chosen to accept it in principle. Before it can proceed to production and typesetting, the journal office will perform it’s third and final technical check, requesting any formatting changes or additional details that may be required.

When fulfilling these final journal requests, double check the final files to confirm all information is correct. If you need to make changes beyond those specifically required in the decision letter, inform the journal and explain why you made the unrequested changes. Any change that could affect the scientific meaning of the work will need to be approved by the handling editor. While including your rationale for the changes will help avoid delays, if there are extensive changes made at this point the paper may need to go through another round of formal review.

Formal Acceptance and Publication

Estimated time: 2 weeks.

After a technical editor has confirmed that all requests from the provisional acceptance letter have been addressed, you will receive your formal acceptance letter. This letter indicates that your paper is being passed from the Editorial department to the production department—that all information has been editorially approved. The scientific content has been approved through peer review, and the journal’s publication requirements have been met.

Congratulations to you and your co-authors! Your article will be available as soon as the journal transforms the submission into a typeset, consistently structured scientific manuscript, ready to be read and cited by your peers.

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

A Step-To-Step Guide to Write a Quality Research Article

- Conference paper

- First Online: 01 June 2023

- Cite this conference paper

- Amit Kumar Tyagi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2657-8700 14 ,

- Rohit Bansal 15 ,

- Anshu 16 &

- Sathian Dananjayan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6103-7267 17

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems ((LNNS,volume 717))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications

230 Accesses

19 Citations

Today publishing articles is a trend around the world almost in each university. Millions of research articles are published in thousands of journals annually throughout many streams/sectors such as medical, engineering, science, etc. But few researchers follow the proper and fundamental criteria to write a quality research article. Many published articles over the web become just irrelevant information with duplicate information, which is a waste of available resources. This is because many authors/researchers do not know/do not follow the correct approach for writing a valid/influential paper. So, keeping such issues for new researchers or exiting researchers in many sectors, we feel motivated to write an article and present some systematic work/approach that can help researchers produce a quality research article. Also, the authors can publish their work in international conferences like CVPR, ICML, NeurIPS, etc., or international journals with high factors or a white paper. Publishing good articles improve the profile of researchers around the world, and further future researchers can refer their work in their work as references to proceed with the respective research to a certain level. Hence, this article will provide sufficient information for researchers to write a simple, effective/impressive and qualitative research article on their area of interest.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Nair, M.M., Tyagi, A.K., Sreenath, N.: The future with industry 4.0 at the core of society 5.0: open issues, future opportunities and challenges. In: 2021 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), pp. 1–7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCI50826.2021.9402498

Tyagi, A.K., Fernandez, T.F., Mishra, S., Kumari, S.: Intelligent Automation Systems at the Core of Industry 4.0. In: Abraham, A., Piuri, V., Gandhi, N., Siarry, P., Kaklauskas, A., Madureira, A. (eds.) ISDA 2020. AISC, vol. 1351, pp. 1–18. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71187-0_1

Chapter Google Scholar

Goyal, D., Tyagi, A.: A Look at Top 35 Problems in the Computer Science Field for the Next Decade. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2020) https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003052098-40

Tyagi, A.K., Meenu, G., Aswathy, S.U., Chetanya, V.: Healthcare Solutions for Smart Era: An Useful Explanation from User’s Perspective. In the Book “Recent Trends in Blockchain for Information Systems Security and Privacy”. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2021)

Google Scholar

Varsha, R., Nair, S.M., Tyagi, A.K., Aswathy, S.U., RadhaKrishnan, R.: The future with advanced analytics: a sequential analysis of the disruptive technology’s scope. In: Abraham, A., Hanne, T., Castillo, O., Gandhi, N., Nogueira Rios, T., Hong, T.-P. (eds.) HIS 2020. AISC, vol. 1375, pp. 565–579. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73050-5_56

Tyagi, A.K., Nair, M.M., Niladhuri, S., Abraham, A.: Security, privacy research issues in various computing platforms: a survey and the road ahead. J. Inf. Assur. Secur. 15 (1), 1–16 (2020)

Madhav, A.V.S., Tyagi, A.K.: The world with future technologies (Post-COVID-19): open issues, challenges, and the road ahead. In: Tyagi, A.K., Abraham, A., Kaklauskas, A. (eds.) Intelligent Interactive Multimedia Systems for e-Healthcare Applications, pp. 411–452. Springer, Singapore (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6542-4_22

Mishra, S., Tyagi, A.K.: The role of machine learning techniques in the Internet of Things-based cloud applications. In: Pal, S., De, D., Buyya, R. (eds.) Artificial Intelligence-Based Internet of Things Systems. Internet of Things (Technology, Communications and Computing). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87059-1_4

Pramod, A., Naicker, H.S., Tyagi, A.K.: Machine Learning and Deep Learning: Open Issues and Future Research Directions for Next Ten Years. Computational Analysis and Understanding of Deep Learning for Medical Care: Principles, Methods, and Applications. Wiley Scrivener (2020)

Kumari, S., Tyagi, A.K., Aswathy, S.U.: The Future of Edge Computing with Blockchain Technology: Possibility of Threats, Opportunities and Challenges. In the Book Recent Trends in Blockchain for Information Systems Security and Privacy. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2021)

Dananjayan, S., Tang, Y., Zhuang, J., Hou, C., Luo, S.: Assessment of state-of-the-art deep learning based citrus disease detection techniques using annotated optical leaf images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 193 (7), 106658 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106658

Nair, M.M., Tyagi, A.K.: Privacy: History, Statistics, Policy, Laws, Preservation and Threat analysis. J. Inf. Assur. Secur. 16 (1), 24–34 (2021)

Tyagi, A.K., Sreenath, N.: A comparative study on privacy preserving techniques for location based services. Br. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 10 (4), 1–25 (2015). ISSN: 2231–0851

Rekha, G., Tyagi, A.K., Krishna Reddy, V.: A wide scale classification of class imbalance problem and its solutions: a systematic literature review. J. Comput. Sci. 15 (7), 886–929 (2019). ISSN Print: 1549–3636

Kanuru, L., Tyagi, A.K., A, S.U., Fernandez, T.F., Sreenath, N., Mishra, S.: Prediction of pesticides and fertilisers using machine learning and Internet of Things. In: 2021 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI), pp. 1–6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCI50826.2021.9402536

Ambildhuke, G.M., Rekha, G., Tyagi, A.K.: Performance analysis of undersampling approaches for solving customer churn prediction. In: Goyal, D., Gupta, A.K., Piuri, V., Ganzha, M., Paprzycki, M. (eds.) Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Information Management and Machine Intelligence. LNNS, vol. 166, pp. 341–347. Springer, Singapore (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9689-6_37

Sathian, D.: ABC algorithm-based trustworthy energy-efficient MIMO routing protocol. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 32 , e4166 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/dac.4166

Varsha, R., et al.: Deep learning based blockchain solution for preserving privacy in future vehicles. Int. J. Hybrid Intell. Syst. 16 (4), 223–236 (2020)

Tyagi, A.K., Aswathy, S U.: Autonomous Intelligent Vehicles (AIV): research statements, open issues, challenges and road for future. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2 , 83–102 (2021). ISSN 2666–6030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijin.2021.07.002

Tyagi, A.K., Sreenath, N.: Cyber physical systems: analyses, challenges and possible solutions. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 1 , 22–33 (2021). ISSN 2667–3452, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iotcps.2021.12.002

Tyagi, A.K., Aghila, G.: A wide scale survey on botnet. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 34 (9), 9–22 (2011). (ISSN: 0975–8887)

Tyagi, A.K., Fernandez, T.F., Aswathy, S.U.: Blockchain and aadhaar based electronic voting system. In: 2020 4th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, pp. 498–504 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECA49313.2020.9297655

Kumari, S., Muthulakshmi, P.: Transformative effects of big data on advanced data analytics: open issues and critical challenges. J. Comput. Sci. 18 (6), 463–479 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3844/jcssp.2022.463.479

Article Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgement

We want to think of the anonymous reviewer and our colleagues who helped us to complete this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Fashion Technology, National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi, India

Amit Kumar Tyagi

Department of Management Studies, Vaish College of Engineering, Rohtak, India

Rohit Bansal

Faculty of Management and Commerce (FOMC), Baba Mastnath University, Asthal Bohar, Rohtak, India

School of Computer Science and Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Chennai, Tamilnadu, 600127, India

Sathian Dananjayan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Amit Kumar Tyagi & Sathian Dananjayan have drafted and approved this manuscript for final publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amit Kumar Tyagi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Computing and Data Science, FLAME University, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Ajith Abraham

Center for Smart Computing Continuum, Burgenland, Austria

Sabri Pllana

University of Bari, Bari, Italy

Gabriella Casalino

University of Jinan, Jinan, Shandong, China

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Thapar Institute of Engineering and Technology, Patiala, Punjab, India

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares that no conflict exists regarding the publication of this paper.

Scope of the Work

As the author belongs to the computer science stream, so he has tried to cover up this article for all streams, but the maximum example used in situations, languages, datasets etc., are with respect to computer science-related disciplines only. This work can be used as a reference for writing good quality papers for international conferences journals.

Disclaimer. Links and papers provided in the work are only given as examples. To leave any citation or link is not intentional.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Tyagi, A.K., Bansal, R., Anshu, Dananjayan, S. (2023). A Step-To-Step Guide to Write a Quality Research Article. In: Abraham, A., Pllana, S., Casalino, G., Ma, K., Bajaj, A. (eds) Intelligent Systems Design and Applications. ISDA 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 717. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35510-3_36

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35510-3_36

Published : 01 June 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-35509-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-35510-3

eBook Packages : Intelligent Technologies and Robotics Intelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to write a research article to submit for publication

Pharmacists and healthcare professionals who are undertaking research should have an understanding of how to produce a research article for publication, and be aware of the important considerations relating to submission to a peer-reviewed journal.

Viennaslide / Alamy Stock Photo

Undertaking and performing scientific, clinical and practice-based research is only the beginning of the scholarship of discovery [1] . For the full impact of any research to be achieved and to have an effect on the wider research and scientific community, it must be published in an outlet accessible to relevant professionals [2] .

Scientific research is often published in peer-reviewed journals. Peer review is defined as the unbiased, independent, critical assessment of scholarly or research manuscripts submitted to journals by experts or opinion leaders [3] . The process and requirements of reviewers has been covered recently [4] . On account of this rigorous process, peer-reviewed scientific journals are considered the primary source of new information that impacts and advances clinical decision-making and practice [5] , [6] .

The development of a research article can be helpful for the promotion of scientific thinking [7] , [8] and the advancement of effective writing skills, allowing the authors to participate in broader scientific discussions that lie beyond their scope of practice or discipline [2] .

This article aims to provide pharmacists and healthcare professionals who are undertaking research with an understanding of how to produce a research article for publication, as well as points to consider before submission to a peer-reviewed journal.

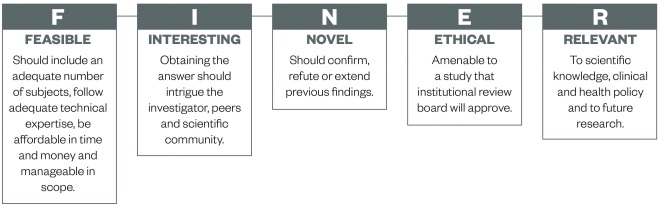

Importance of the research question

This article will not go into detail about forming suitable research questions, however, in principle, a good research question will be specific, novel and of relevance to the scientific community (e.g. pharmacy – pharmacists, pharmaceutical scientists, pharmacy technicians and related healthcare professionals). Hulley et al . suggest using the FINER criteria (see ‘Figure 1: FINER criteria for a good research question’) to aid the development of a good research question [9] .

Figure 1: FINER criteria for a good research question

Source: Hulley S, Cummings S, Browner W et al . [9]

The FINER criteria highlight useful points that may generally increase the chances of developing a successful research project. A good research question should specify the population of interest, be of interest to the scientific community and potentially to the public, have clinical relevance and further current knowledge in the field.

Having a clear research question that is of interest to those working in the same field will help in the preparation of an article because it can be used as the central organising principle – all of the content included and discussed should focus on answering this question.

Preparing a first draft

Before writing the article, it is useful to highlight several journals that you could submit the final article to. It also helps to familiarise yourself with these journals’ styles, article structures and formatting instructions before starting to write. Many journals also have criteria that research articles should be able to satisfy. For example, all research article submissions to Clinical Pharmacist must demonstrate innovative or novel results that are sustainable, reproducible and transferable [10] .

Having researched potential target journals, you should have a clear idea about your target audience, enabling you to pitch the level of the article appropriately [11] (see ‘Box 1: Top tips to prepare for writing’).

Box 1: Top tips to prepare for writing

- Know the focus of the paper – identify two or three important findings and make these the central theme of the article;

- Gather important data, perform any analyses and make rough data plots and tables beforehand. These can then be refined for inclusion or submitted as supplementary information if needed;

- Organise your results to flow in a logical sequence;

- Know the structure and requirements of your target journals (check websites and author guidelines, as well as published articles);

- Think about the style of the piece and look to pitch the article at the level of the intended audience;

- Clarity should be your guiding principle.

Structuring a research article

Most research articles follow a similar structure and format that includes an abstract, introduction, methods, results and discussion, as well as a summary of the key points discussed in the article.

One approach is to start with the methods section, which can be derived from the protocol and any pilot phase. Many of the figures and tables can be constructed in advance, which will help with writing the results section. The questions addressed by the study can be used alongside the results to formulate the introduction, which can guide how the discussion is written [11] .

Clinical Pharmacist , like other peer-reviewed journals, has specific author guidelines and formatting instructions to help authors prepare their articles [10] , [12] , [13] . The following sections will discuss the required sections and important considerations for authors when writing.

Title, abstract and keywords

The title, abstract and keywords are essential to the successful communication of research. Most electronic search engines, databases (e.g. PubMed/MEDLINE) and journal websites extract words from them to determine whether your article will be displayed to interested readers [14] , [15] , [16] , [17] , enabling accurate dissemination and leading to future citations.

In addition, the title and abstract are usually freely available online. If an article is not published in an ‘open access’ format, (i.e. it is free and immediately available online and access is combined with the rights to use these articles fully in the digital environment) [18] , or if the reader does not have a subscription to the journal, they will have to decide on whether to pay to access the full article to continue reading. Therefore, it is imperative that they are informative and accurate.

The title should accurately reflect the research, identify the main issue and begin with the subject matter, while being both simple and enticing enough to attract the audience [19] . Authors should avoid using ‘a study of’, ‘investigations into’ and ‘observations on’ in titles. It is also worth remembering that abstracting and indexing services, such as MEDLINE, require accurate titles, because they extract keywords from them for cross-referencing [19] .

Many journals require the abstract to be structured in the same way as the main headings of the paper (e.g. introduction, methods, results, discussion and conclusion) and to be around 150–300 words in length [10] . In general, references should not be cited in the abstract.

Introduction

The introduction should provide the background and context to the study. Two or three paragraphs can be dedicated to the discussion of any previous work and identification of gaps in current knowledge. The rest of the introduction should then outline what this piece of work aims to address and why this is important, before stating the objectives of the study and the research question [20] .

The methods section should provide the reader with enough detail for them to be able to reproduce the study if desired [3] . The context and setting of the study should be described and the study design specified. The section should further describe the population (including the inclusion and exclusion criteria), sampling strategy and the interventions performed. The main study variables should be identified and the data collection procedures described [3] .

Authors should provide specific, technical and detailed information in this section. Several checklists and guidelines are available for the reporting of specific types of studies:

- CONSORT is used for developing and reporting a randomised controlled trial [21] ;

- The STARD checklist can help with designing a diagnostic accuracy study [22] ;

- The PRISMA checklist can be used when performing a metaâ€analyses or systematic review, but can also help with compiling an introduction [23] .

For the reporting of qualitative research studies, authors should explain which research tradition the study utilises and link the choice of methodological strategies with the research goals [24] .

For studies describing the development of new initiatives or clinical services, authors should describe the situation before the initiative began, the establishment of priorities, formulation of objectives and strategies, mobilisation of resources, and processes used in the methods section [10] .

The final portion of the methods section will include the statistical methods used to analyse the data [25] . The statistical methods employed should be described with enough detail to enable a knowledgeable reader with access to the original data to be able to judge its appropriateness for the study and verify the results [3] . For survey-based studies and information on sampling frame, size and statistical powers, see ‘When to use a survey in pharmacy practice research’ [26] .

Findings should be quantified and presented with appropriate indicators of measurement error or uncertainty (e.g. confidence intervals). Authors should avoid relying solely on statistical hypothesis testing, such as P values, because these fail to convey important information about effect size and precision of estimates [3] . Statistical terms, abbreviations and most symbols should be defined, and the statistical software package and versions used should be specified. Authors should also take care to distinguish prespecified from exploratory analyses, including subgroup analyses [3] .

The results section should be straightforward and factual and all of the results that relate to the research question should be provided, with detail including simple counts and percentages [27] . Data collection and recruitment should be commented on and the participants described. Secondary findings and the results of subgroup analyses can also be presented [27] .

Figures, schemes and tables

To present data and results of the research study, figures, schemes and tables can be used. They should include significant digits, error bars and levels of statistical significance.

Tables should be presented with a summary title, followed by caption, a sentence or two that describes the content and impact of the data included in the table. All captions should provide enough detail so that the table or figure can be interpreted and understood as stand-alone material, separate from the article.

Figures should also be presented with a summary title, a caption that describes the significant result or interpretation that can be made from the figure, the number of repetitions within the experiment, as well as what the data point actually represents. All figures and tables should be cited in the manuscript text [11] .

When compiling tables and figures, important statistics, such as the number of samples (n), the index of dispersion (standard deviation [SD], standard error of the mean [SEM]), and the index of central tendency (mean, median or mode), must be stated. The statistical analysis performed should also be included and specific statistical data should be indicated (e.g. P values) [11] .

Discussion and conclusions

The discussion section should state the main findings of the study. The main results should be compared with reference to previous research and current knowledge, and where this has been extended it should be fully described [2] , [11] , [25] . For clinical studies, relevant discussion of the implications the results may have on policy should be included [10] . It is important to include an analysis of the strengths and limitations of the study and offer perspectives for future work [2] . Excessive presentation of data and results without any discussion should be avoided and it is not necessary to cite a published work for each argument presented. Any conclusions should include the major findings, followed by a brief discussion of future perspectives and the application of this work to other disciplines [10] .

The list of references should be appropriate; important statements presented as facts should be referenced, as well as the methods and instruments used. Reference lists for research articles, however, unlike comprehensive reviews of a topic, do not necessarily have to be exhaustive. References to unpublished work, to documents in the grey literature (technical reports), or to any source that the reader will have difficulty finding or understanding should be avoided [27] . Most journals have reference limits and specific formatting requirements, so it is important to check the journal’s author guidelines [10] , [11] , [12] , [13] , [19] .

Authorship and acknowledgements

Determining contributors who qualify as authors and those who should be acknowledged can be difficult. Clinical Pharmacist follows guidance from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, which recommends that authorship be based on the following four criteria:

- Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved [3] .

Therefore, only individuals who meet all four criteria should be identified as authors [3] . The contribution of individuals who do not meet all four criteria should instead be included in the acknowledgements.

In addition, a statement that recognises any funding sources for the work should be added to the acknowledgements. This statement should adhere to the guidelines provided by the funding institution [11] .

Supplementary and supporting information

A key principle of research publication is that others should be able to replicate and build upon an author’s published claims. Therefore, submitted manuscripts should contain the necessary detail about the study and analytical design, and the data must be available for editors and peer-reviewers to allow full evaluation to take place. This is now commonplace and is seen as best practice. Author guidelines now include sections related to misconduct and falsification of data [28] . By participating in self-archiving practices and providing full data sets, authors can play their part in transparency.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society website hosts a database to help share data from research studies. The map of evidence collates existing evidence and ongoing initiatives that can ultimately inform policy and practice relating to pharmacy; enables the sharing and showcasing of good pharmacy practice and innovation; and aims to increase the knowledge exchange and learning in pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences [29] .

Revising your article prior to submission

Once a draft research article has been prepared, it should be shared among all of the co-authors for review and comments. A full revision of the draft should then take place to correct grammar and check flow and logic before journal submission. All authors will have to agree on the authenticity of the data and presentation before formal submission can take place [3] (see ‘Box 2: Common mistakes and reasons why research articles are rejected for publication’).

Box 2: Common mistakes and reasons why research articles are rejected for publication

- Lack of novelty and importance of the research question;

- Poor study design;

- Methods not accurately and adequately described;

- Results poorly reported, along with little analysis of data;

- Lack of statistical analysis;

- Not acknowledging the study’s limitations;

- Providing unsupported conclusions or overstating the results of the study;

- Poor writing;

- Not following the journal’s style and formatting guidance;

- Submitting a manuscript that is incomplete or outside of the aims and scope.

Selecting a journal and submitting your manuscript

It is important to select a journal for submission wisely because this choice can determine the impact and dissemination of your work [13] . Impact factor (a measure of the frequency with which the average article in a journal has been cited in a particular year), the scope and readership of a title may also influence your choice.

Furthermore, approval and adequate disclosures must be obtained from all co-authors. A conflict of interests form is also completed as part of the submissions process (normally completed by the lead author on behalf of all authors).

Many journals now request that a cover letter is also submitted to the editor, putting the study in context and explaining why the research is of importance to their audience and why it should be considered for publication in their journal.

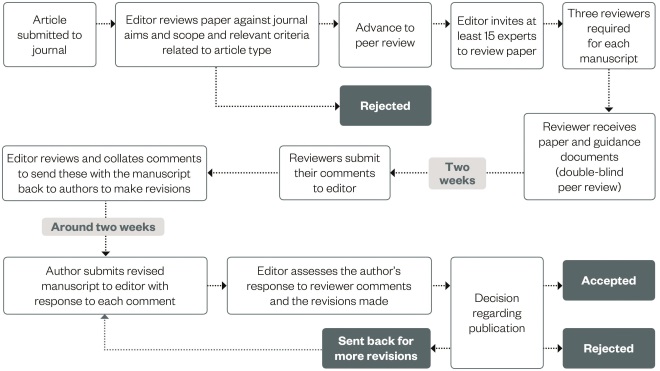

Once this is all completed, the article can be formally submitted (usually via email or an online submission system). Figure 2 provides a sample process for a manuscript once submitted to a journal for consideration for publication.

Figure 2: Sample process for a submitted manuscript

Source: The Pharmaceutical Journal

All journals follow a similar process for article submissions, whether they use a formal online submissions system or simply email. Clinical Pharmacist uses a process similar to this and it is useful for authors to be aware of how their submission may progress once submitted to a journal for publication.

Useful Links

- The EQUATOR Network

- Research4Life – Authorship skills modules

- Pharmacy Research UK

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal . You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

[1] Boyer E. Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities for the professoriate . 1990. Princeton, NJ: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

[2] Hoogenboom BJ & Manske RC. How to write a scientific article. Int J Sports Phys Ther . 2012;7(5):512–517. PMCID: PMC3474301

[3] International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. 2014. Available at: http://www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf (accessed November 2016).

[4] Dowdall M. How to be an effective peer reviewer. Clinical Pharmacist 2015;7(10). doi: 10.1211/CP.2015.20200006

[5] Nahata MC. Tips for writing and publishing an article. Ann Pharmaco . 2008;42:273–277. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K616

[6] Dixon N. Writing for publication: A guide for new authors. Int J Qual Health Care . 2001;13:417–421. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/13.5.417

[7] Keys CW. Revitalizing instruction in scientific genres: Connecting knowledge production with writing to learn in science. Sci Educ . 1999;83:115–130.

[8] Gopen G & Swan J. The science of scientific writing. Am Sci . 1990;78:550–558. Available at: http://www.americanscientist.org/issues/pub/the-science-of-scientific-writing (accessed November 2016)

[9] Hulley S, Cummings S, Browner W et al . Designing clinical research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

[10] The Pharmaceutical Journal and Clinical Pharmacist. Author Guidance (2015). Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/for-authors-and-referees/article-types/#Practice_reports (accessed November 2016)

[11] Fisher JP, Jansen JA, Johnson PC et al . Guidelines for writing a research article for publication. Mary Ann Liebert Inc. Available at: https://www.liebertpub.com/media/pdf/English-Research-Article-Writing-Guide.pdf (accessed November 2016)

[12] Nature. Author Resources: How to write a paper. Available at: http://www.nature.com/authors/author_resources/how_write.html (accessed November 2016)

[13] Wiley Online Library. Resources for authors and reviewers: preparing your article. Available at: http://olabout.wiley.com/WileyCDA/Section/id-828006.html (accessed November 2016)

[14] SAGE Publications. Help readers find your article. Available at: http://www.uk.sagepub.com/journalgateway/findArticle.htm (accessed November 2016)

[15] Bem DJ. Writing the empirical journal article. In: MP Zanna & JM Darley (Eds.), The complete academic: a practical guide for the beginning social scientist (pp. 171–201). New York: Random House; 1987.

[16] Fathalla M & Fathalla M. A practical guide for health researchers. Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa237.pdf (accessed November 2016)

[17] Coghill A & Garson L (Eds.). Scientific Papers. In: A Coghill & L Garson (Eds.), The ACS Style Guide, 3 rd Edition (pp. 20–21). New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

[18] The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Institute. Available at: http://sparcopen.org/open-access/ (accessed November 2016).

[19] Elsevier. Understanding the publishing process: how to publish in scholarly journals. Available at: https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/91173/Brochure_UPP_April2015.pdf (accessed November 2016).

[20] SciDevNet. How do I write a scientific paper? 2008. Available at: http://www.scidev.net/global/publishing/practical-guide/how-do-i-write-a-scientific-paper-.html (accessed November 2016)

[21] Moher D, Schultz KR & Altman DG. CONSORT GROUP (Consolidatied Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallelâ€group randomized controlled trials. Ann Intern Med . 2001;134:657–662. PMID: 11304106

[22] Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE et al . Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD Initiative. Ann Int Med 2003;138:40–44. PMID: 12513043

[23] Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al . The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaâ€analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

[24] Devers KJ & Frankel RM. Getting qualitative research published. Educ Health 2001;14:109–117. doi: 10.1080/13576280010021888

[25] Van Way CW. Writing a scientific paper. Nutr Clin Pract 2007;22:636–640. PMID: 18042951

[26] Kishore V. When to use a survey in pharmacy practice research. The Pharmaceutical Journal 296(7886). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20200700

[27] Perneger PV & Hudelson PM. Writing a research article: advice to beginners . Int J Qual Health Care 2004;16(3):191–192. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh053

[28] World Association of Medical Editors. Professionalism Code of Conduct. 2016. Available at: http://www.wame.org/News/Details/16 (accessed November 2016)

[29] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Map of Evidence. Available at: http://www.rpharms.com/support/map-of-evidence.asp (accessed November 2016)

You might also be interested in…

Working to improve our digital archive

The Pharmaceutical Journal is moving forward into a digital future

The launch of our new digital platform is just the beginning of our plans for the future of PJ

- Discoveries

- Right Journal

- Journal Metrics

- Journal Fit

- Abbreviation

- In-Text Citations

- Bibliographies

- Writing an Article

- Peer Review Types

- Acknowledgements

- Withdrawing a Paper

- Form Letter

- ISO, ANSI, CFR

- Google Scholar

- Journal Manuscript Editing

- Research Manuscript Editing

Book Editing

- Manuscript Editing Services

Medical Editing

- Bioscience Editing

- Physical Science Editing

- PhD Thesis Editing Services

- PhD Editing

- Master’s Proofreading

- Bachelor’s Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading Services

- Best Dissertation Proofreaders

- Masters Dissertation Proofreading

- PhD Proofreaders

- Proofreading PhD Thesis Price

- Journal Article Editing

- Book Editing Service

- Editing and Proofreading Services

- Research Paper Editing

- Medical Manuscript Editing

- Academic Editing

- Social Sciences Editing

- Academic Proofreading

- PhD Theses Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading

- Proofreading Rates UK

- Medical Proofreading

- PhD Proofreading Services UK

- Academic Proofreading Services UK

Medical Editing Services

- Life Science Editing

- Biomedical Editing

- Environmental Science Editing

- Pharmaceutical Science Editing

- Economics Editing

- Psychology Editing

- Sociology Editing

- Archaeology Editing

- History Paper Editing

- Anthropology Editing

- Law Paper Editing

- Engineering Paper Editing

- Technical Paper Editing

- Philosophy Editing

- PhD Dissertation Proofreading

- Lektorat Englisch

- Akademisches Lektorat

- Lektorat Englisch Preise

- Wissenschaftliches Lektorat

- Lektorat Doktorarbeit

PhD Thesis Editing

- Thesis Proofreading Services

- PhD Thesis Proofreading

- Proofreading Thesis Cost

- Proofreading Thesis

- Thesis Editing Services

- Professional Thesis Editing

- Thesis Editing Cost

- Proofreading Dissertation

- Dissertation Proofreading Cost

- Dissertation Proofreader

- Correção de Artigos Científicos

- Correção de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Correção de Inglês

- Correção de Dissertação

- Correção de Textos Precos

- 定額 ネイティブチェック

- Copy Editing

- FREE Courses

- Revision en Ingles

- Revision de Textos en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis

- Revision Medica en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis Precio

- Revisão de Artigos Científicos

- Revisão de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Revisão de Inglês

- Revisão de Dissertação

- Revisão de Textos Precos

- Corrección de Textos en Ingles

- Corrección de Tesis

- Corrección de Tesis Precio

- Corrección Medica en Ingles

- Corrector ingles

Select Page

How To Write a Journal Article

Posted by Rene Tetzner | Sep 6, 2021 | Paper Writing Advice | 0 |

How To Write a Journal Article for Publication in Twelve Essential Steps Original articles intended for publication are the most common means of disseminating the processes, results and implications of advanced research, so it is imperative that academics and scientists who wish to publish and share their work know how to write a journal article successfully. Although there are significant variations in manuscript requirements among disciplines and publishers, the writing tips I present below apply to most scholarly articles and journals across a wide range of research fields and specialisations.

Step 1: The first question to ask yourself as you begin drafting your paper or searching for a journal to publish it is what type of article will be appropriate for the material you wish to communicate. Original research, for instance, is usually reported in an original research article, whereas an evaluation of published scholarship on a topic would be written as a review article. Choosing the right type of article before you start is essential.

Step 2: Either before or after you draft your article, you will need to learn about periodicals in the field and choose one as your target journal. The scope, aims and concerns published on the journal’s website should be appropriate for your research, and the journal must publish the kind of paper necessary to communicate all important aspects of your work.

Step 3: Once you have decided on the journal to which you will be submitting your article, you should study the journal’s guidelines for authors. In some cases these will provide a great deal of information about how to write a journal article for publication; in others very little help will be offered. Either way, the guidelines must be followed with care as you prepare your article, so pay close attention to details, examples and restrictions.

Step 4: With the journal’s guidelines and your research notes by your side (or at least firmly in mind), you are ready to outline the structure and content of your article. A scientific research article is likely to use a predictable structure of introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion and conclusions, but other fields and types of paper might offer greater freedom. Structure should never be neglected, however, since clear and logical organisation increases accessibility and reader comprehension.

Step 5: Preparing tables, figures, appendices and other supplementary materials before you actually start drafting the paper is an excellent strategy when you are struggling with how to write a journal article. The production of these tools for readers can help an author analyse and interpret findings more effectively, and writing the main text with these tools in hand tends to reduce unnecessary repetition of information.

Step 6: For many academics and scientists, starting to draft the text is the most difficult part of writing an article for publication. Beginning can be rendered easier by writing the separate sections not in the order in which they will ultimately appear, but in an order that better reflects the research process. The methods can therefore be described first, with the report of results, the discussion and the conclusions following. Once you know the contents of these parts, the introduction, background, abstract and list of references can be added.

Step 7: Be sure to take the time to assess your methods, analyse your results and interpret your findings thoroughly. Reporting what you did and what you discovered is not enough for a research paper intended for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. You will also need to tell your audience what your research means, why it is innovative and how it might be productively used by future researchers and practitioners.

Step 8: Remember as you work out how to write a journal article that there is simply no substitute for excellent writing. Scholarly prose must be both clear and correct to communicate research processes and results effectively, and the style must be both formal and appropriate for your discipline or area of specialisation. Reading published articles in your field and especially in your target journal will give you a good idea of the kind of writing you will need to submit.

Step 9: Proofread, edit and revise your draft repeatedly until you have eliminated all errors of fact, language and typing. Too many authors neglect this time-consuming aspect of how to write a journal article and suffer the consequences in the form of rejections and revision requests. As the person who knows your research better than anyone else, you are the person to ensure that your article intended for publication does that research justice.

Step 10: Recruit mentors, colleagues and friends to read your article and offer feedback. Researchers who work in your field and have successfully published their own academic or scientific writing will be able to comment constructively on research content and presentation. If English grammar, tricky references or other challenges of language and formatting prove problematic, a professional proofreader or editor can help.

Step 11: After reader feedback has been considered and the final revisions are complete, submit your manuscript exactly as the journal’s instructions indicate. Submission via an online form is an efficient and common method, but even if the journal’s preferences seem outdated, they must be observed. Unless the guidelines suggest that a cover letter to the journal editor would be unwelcome, be sure to include one to introduce your research and article in an engaging way.

Step 12: Finally, it is likely that your thoughts will be with your manuscript after you have submitted it and even that a host of ideas for further refinements will pop into your mind the instant the article is beyond your grasp. Take advantage of this impulse as you await a response by jotting your ideas down. If a request for revisions arrives from the editor, your notes are likely to prove incredibly helpful.

You might be interested in Services offered by Proof-Reading-Service.com

Journal editing.

Journal article editing services

PhD thesis editing services

Scientific Editing

Manuscript editing.

Manuscript editing services

Expert Editing

Expert editing for all papers

Research Editing

Research paper editing services

Professional book editing services

How To Write a Journal Article Reliable Tips are Designed To Help Authors Writing a Journal Article

Related Posts

How To Write the Findings Section of a Research Paper

September 2, 2021

Tips on How To Write a Journal Article

August 30, 2021

How To Write Highlights for an Academic or Scientific Paper

September 7, 2021

Tips on How To Write an Effective Figure Legend

August 27, 2021

Our Recent Posts

Our review ratings

- Examples of Research Paper Topics in Different Study Areas Score: 98%

- Dealing with Language Problems – Journal Editor’s Feedback Score: 95%

- Making Good Use of a Professional Proofreader Score: 92%

- How To Format Your Journal Paper Using Published Articles Score: 95%

- Journal Rejection as Inspiration for a New Perspective Score: 95%

Explore our Categories

- Abbreviation in Academic Writing (4)

- Career Advice for Academics (5)

- Dealing with Paper Rejection (11)

- Grammar in Academic Writing (5)

- Help with Peer Review (7)

- How To Get Published (146)

- Paper Writing Advice (17)

- Referencing & Bibliographies (16)

How to find the right journal for your research (using actual data)

Joanna Wilkinson

Want to help your research flourish? We share tips for using publisher-neutral data and statistics to find the right journal for your research paper.

The right journal helps your research flourish. It puts you in the best position to reach a relevant and engaged audience, and can extend the impact of your paper through a high-quality publishing process.

Unfortunately, finding the right journal is a particular pain point for inexperienced authors and those who publish on interdisciplinary topics. The sheer number of journals published today is one reason for this. More than 42,000 active scholarly peer-reviewed journals were published in 2018 alone, and there’s been accelerated growth of more than 5% in recent years.

The overwhelming growth in journals has left many researchers struggling to find the best home for their manuscripts which can be a daunting prospect after several long months producing research. Submitting to the wrong journal can hinder the impact of your manuscript. It could even result in a series of rejections, stalling both your research and career. Conversely, the right journal can help you showcase your research to the world in an environment consistent with your values.

Keep reading to learn how solutions like Journal Citation Reports ™ (JCR) and Master Journal List can help you find the right journal for your research in the fastest possible time.

What to look for in a journal and why

To find the right journal for your research paper, it’s important to consider what you need and want out of the publishing process.

The goal for many researchers is to find a prestigious, peer-reviewed journal to publish in. This might be one that can support an application for tenure, promotion or future funding. It’s not always that simple, however. If your research is in a specialized field, you may want to avoid a journal with a multidisciplinary focus. And if you have ground-breaking results, you may want to pay attention to journals with a speedy review process and frequent publication schedule. Moreover, you may want to publish your paper as open access so that it’s accessible to everyone—and your institution or funder may also require this.

With so many points to consider, it’s good practice to have a journal in mind before you start writing. We published an earlier post to help you with this: Find top journals in a research field, step-by-step guide . Check it out to discover where the top researchers in your field are publishing.

Already written your manuscript? No problem: this blog will help you use publisher-neutral data and statistics to choose the right journal for your paper.

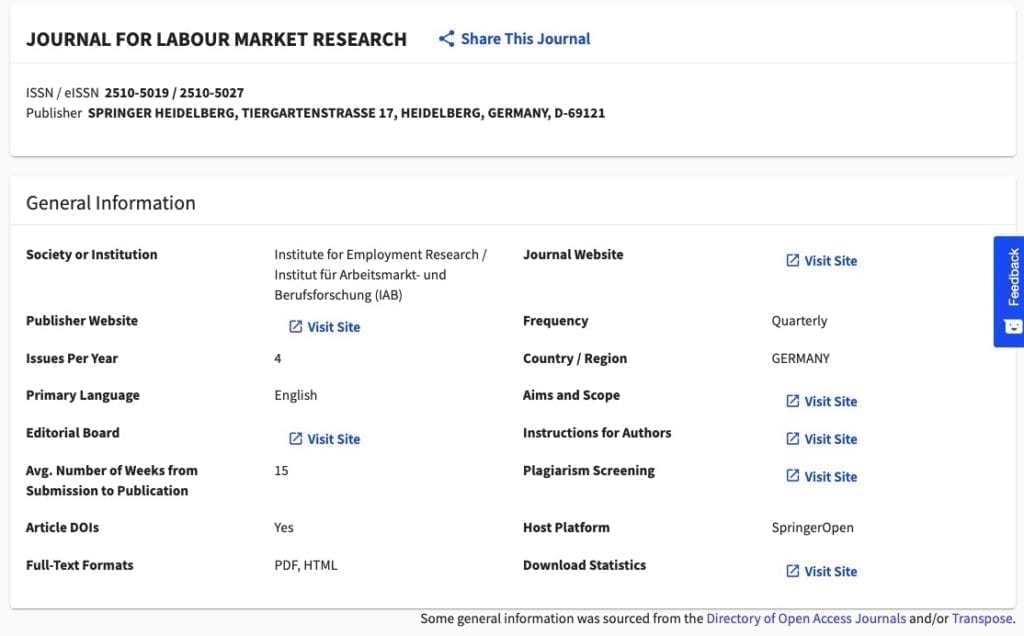

First stop: Manuscript Matcher in the Master Journal List

Master Journal List Manuscript Matcher is the ultimate place to begin your search for journals. It is a free tool that helps you narrow down your journal options based on your research topic and goals.

Pairing your research with a journal

Manuscript Matcher, also available via EndNote™ , provides a list of relevant journals indexed in the Web of Science™ . First, you’ll want to input your title and abstract (or keywords, if you prefer). You can then filter your results using the options shown on the left-hand sidebar, or simply click on the profile page of any journal listed.

Each journal page details the journal’s coverage in the Web of Science. Where available, it may also display a wealth of information, including:

- open access information (including whether a journal is Gold OA)

- the journal’s aims and scope

- download statistics

- average number of weeks from submission to publication, and

- peer review information (including type and policy)

Ready to try Manuscript Matcher? Follow this link .

Identify the journals that are a good topical fit for your research using Manuscript Matcher. You can then move to Journal Citation Reports to understand their citation impact, audience and open access statistics.

Find the right journal with Journal Citation Reports

Journal Citation Reports is the most powerful solution for journal intelligence. It uses transparent, publisher-neutral data and statistics to provide unique insight into a journal’s role and influence. This will help you produce a definitive list of journals best-placed to publish your findings, and more.

Three data points exist on every journal page to help you assess a journal as a home for your research. These are: citation metrics, article relevance and audience.

Citation Metrics

The Journal Impact Factor™ (JIF) is included as part of the rich array of citation metrics offered on each journal page. It shows how often a journal’s recently published material is cited on average.

Learn how the JIF is calculated in this guide .

It’s important to note that the JIF has its limitations and no researcher should depend on the impact factor alone when assessing the usefulness or prestige of a journal. Journal Citation Reports helps you understand the context of a journal’s JIF and how to use the metric responsibly.

The JCR Trend Graph, for example, places the JIF in the context of time and subject category performance. Citation behavior varies across disciplines, and journals in JCR may be placed across multiple subject categories depending on the scope of their content. The Trend Graph shows you how the journal performs against others in the same subject category. It also gives you an understanding of how stable that performance is year-on-year.

You can learn more about this here .

The 2021 JCR release introduced a new, field-normalized metric for measuring the citation impact of a journal’s recent publications. By normalizing for different fields of research and their widely varying rates of publication and citation, the Journal Citation Indicator provides a single journal-level metric that can be easily interpreted and compared across disciplines. Learn more about the Journal Citation Indicator here .

Article relevance

The Contributing Items section in JCR demonstrates whether the journal is a good match for your paper. It can also validate the information you found in the Manuscript Matcher. You can view the full list in the Web of Science by selecting “Show all.”

JCR helps you understand the scholarly community engaging with a journal on both a country and an institutional level. This information provides insight on where in the world your own paper might have an impact if published in that particular journal. It also gives you a sense of general readership, and who you might be talking to if you choose that journal.

Start using Journal Citation Reports today .

Ready to find the right journal for your paper?

The expansion of scholarly journals in previous years has made it difficult for researchers to choose the right journal for their research. This isn’t a good position to be in when you’ve spent many long months preparing your research for the world. Journal Citation Reports , Manuscript Matcher by Master Journal List and the Web of Science are all products dedicated to helping you find the right home for your paper. Try them out today and help your research flourish.

Stay connected

Want to learn more? You can also read related articles in our Research Smarter series, with guidance on finding the relevant papers for your research and how you can save hundreds of hours in the writing process . You can also read about the 2022 JCR release here . Finally, subscribe to receive our latest news, resources and events to help make your research journey a smart one.

Subscribe to receive regular updates on how to research smarter

Related posts

Demonstrating socioeconomic impact – a historical perspective of ancient wisdom and modern challenges.

Unlocking U.K. research excellence: Key insights from the Research Professional News Live summit

For better insights, assess research performance at the department level

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Supplements

- Virtual Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Benefits of Publishing with JBCR

- About Journal of Burn Care and Research

- About the American Burn Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

602 Too Few Burn Papers and Images, Lowering Publication Barriers for Low- and Middle-Income Country Authors

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Cameron J Kneib, Ryann E Shor, Kiran K Nakarmi, Manish K Yadav, Raslina Shrestha, Ariel Miranda, Tam N Pham, Barclay T Stewart, 602 Too Few Burn Papers and Images, Lowering Publication Barriers for Low- and Middle-Income Country Authors, Journal of Burn Care & Research , Volume 45, Issue Supplement_1, May/June 2024, Page 185, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbcr/irae036.236

- Permissions Icon Permissions

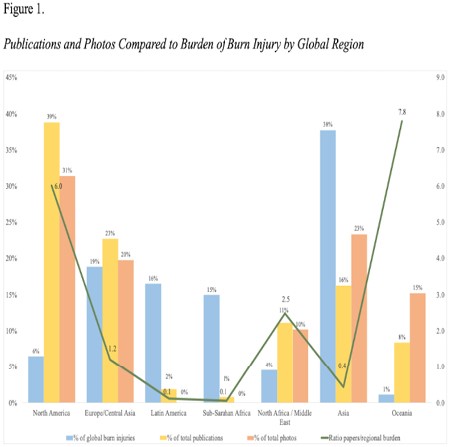

Whereas the burden of burn injury is greatest in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), publications from these regions represent a disproportionately small volume of the published burn literature in English. This important gap in our cumulative knowledge contributes to the slow progress in global burn injury control. In addition to manuscripts, clinical photographs are important representations of injury and outcomes. We aimed to compare the current volume of burn publications and photographs to the global burn injury burden and sought to identify potential journal-level barriers to publication.

A bibliometric analysis was performed by sampling three leading burn surgery journals published in the English language (Journal of Burn Care and Research, Burns, European Burn Journal) between 2021-2023. Country of corresponding author and number of photos were tabulated and categorized by region. Volume was compared to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 estimates for incidence of thermal injury by region. Journal submission instructions were reviewed for potential barriers to publication.

A total of 916 articles were reviewed from 59 countries. Analysis showed 147 articles with 1117 human photos. GBD incidence of burn, publications, and photographs by region are shown in Figure 1. North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Oceania had a higher proportion of published images to burn injury incidence than Latin America, Africa, and Asia (X2 (6, N = 915) =3585, p < 0.001). Barriers to journal publication included charges for published images (up to 600 USD/image), open access costs (900-3500 USD with 1 of 3 publishers offering tiered discounts specific to LMIC), English language review (0.06-0.07 USD/word), and society affiliation discounts. Table 1 summarizes identified barriers and potential solutions.

There is a relative paucity of LMIC contributions to publications and clinical photos in English language burn journals. Identified publication barriers and added costs from journals likely contribute to this disparity.

Publication-level strategies to increase authorship and clinical photographs from underrepresented regions are urgently needed.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1559-0488

- Print ISSN 1559-047X

- Copyright © 2024 American Burn Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

An inflammation-related subtype classification for analyzing tumor microenvironment and clinical prognosis in colorectal cancer.

- Beijing Cancer Hospital, Peking University, Beijing, China

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

Select one of your emails

You have multiple emails registered with Frontiers:

Notify me on publication

Please enter your email address:

If you already have an account, please login

You don't have a Frontiers account ? You can register here