Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Health Topics

- Brochures and Fact Sheets

- Help for Mental Illnesses

- Clinical Trials

- Download PDF

- Order a free hardcopy

What is depression?

Everyone feels sad or low sometimes, but these feelings usually pass. Depression (also called major depression, major depressive disorder, or clinical depression) is different. It can cause severe symptoms that affect how a person feels, thinks, and handles daily activities, such as sleeping, eating, or working.

Depression can affect anyone regardless of age, gender, race or ethnicity, income, culture, or education. Research suggests that genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors play a role in the disorder.

Women are diagnosed with depression more often than men, but men can also be depressed. Because men may be less likely to recognize, talk about, and seek help for their negative feelings, they are at greater risk of their depression symptoms being undiagnosed and undertreated. Studies also show higher rates of depression and an increased risk for the disorder among members of the LGBTQI+ community.

In addition, depression can co-occur with other mental disorders or chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and chronic pain. Depression can make these conditions worse and vice versa. Sometimes, medications taken for an illness cause side effects that contribute to depression symptoms as well.

What are the different types of depression?

There are two common types of depression.

- Major depression includes symptoms of depressed mood or loss of interest, most of the time for at least 2 weeks, that interfere with daily activities.

- Persistent depressive disorder (also called dysthymia or dysthymic disorder) consists of less severe depression symptoms that last much longer, usually for at least 2 years.

Other types of depression include the following.

- Seasonal affective disorder comes and goes with the seasons, with symptoms typically starting in the late fall and early winter and going away during the spring and summer.

- Depression with symptoms of psychosis is a severe form of depression in which a person experiences psychosis symptoms, such as delusions or hallucinations.

- Bipolar disorder involves depressive episodes, as well as manic episodes (or less severe hypomanic episodes) with unusually elevated mood, greater irritability, or increased activity level.

Additional types of depression can occur at specific points in a woman’s life. Pregnancy, the postpartum period, the menstrual cycle, and menopause are associated with physical and hormonal changes that can bring on a depressive episode in some people.

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a more severe form of premenstrual syndrome, or PMS, that occurs in the weeks before menstruation.

- Perinatal depression occurs during pregnancy or after childbirth. It is more than the “baby blues” many new moms experience after giving birth.

- Perimenopausal depression affects some women during the transition to menopause. Women may experience feelings of intense irritability, anxiety, sadness, or loss of enjoyment.

What are the signs and symptoms of depression?

Common signs and symptoms of depression include:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism

- Feelings of irritability, frustration‚ or restlessness

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities

- Fatigue, lack of energy, or feeling slowed down

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions

- Difficulty sleeping, waking too early in the morning, or oversleeping

- Changes in appetite or unplanned weight changes

- Physical aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems without a clear physical cause that do not go away with treatment

- Thoughts of death or suicide or suicide attempts

Depression can also involve other changes in mood or behavior that include:

- Increased anger or irritability

- Feeling restless or on edge

- Becoming withdrawn, negative, or detached

- Increased engagement in high-risk activities

- Greater impulsivity

- Increased use of alcohol or drugs

- Isolating from family and friends

- Inability to meet responsibilities or ignoring other important roles

- Problems with sexual desire and performance

Not everyone who is depressed shows all these symptoms. Some people experience only a few symptoms, while others experience many. Depression symptoms interfere with day-to-day functioning and cause significant distress for the person experiencing them.

If you show signs or symptoms of depression and they persist or do not go away, talk to a health care provider. If you see signs of depression in someone you know, encourage them to seek help from a mental health professional.

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org . In life-threatening situations, call 911 .

How is depression diagnosed?

To be diagnosed with depression, a person must have symptoms most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks. One of the symptoms must be a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in most activities. Children and adolescents may be irritable rather than sad.

Although several persistent symptoms, in addition to low mood, are required for a depression diagnosis, people with only a few symptoms may benefit from treatment. The severity and frequency of symptoms and how long they last vary depending on the person.

If you think you may have depression, talk to a health care provider, such as a primary care doctor, psychologist, or psychiatrist. During the visit, the provider may ask when your symptoms began, how long they have lasted, how often they occur, and if they keep you from going out or doing your usual activities. It may help to take some notes about your symptoms before the visit.

Certain medications and medical conditions, such as viruses or thyroid disorders, can cause the same symptoms as depression. A provider can rule out these possibilities by doing a physical exam, interview, and lab tests.

Does depression look the same in everyone?

Depression can affect people differently depending on their age.

- Children may be anxious or cranky, pretend to be sick, refuse to go to school, cling to a parent, or worry that a parent may die.

- Older children and teens may get into trouble at school, sulk, be easily frustrated‚ feel restless, or have low self-esteem. They may have other disorders, such as anxiety, an eating disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or substance use disorder. Older children and teens are also more likely to experience excessive sleepiness (called hypersomnia) and increased appetite (called hyperphagia).

- Young adults are more likely to be irritable, complain of weight gain and hypersomnia, and have a negative view of life and the future. They often have other disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, or substance use disorder.

- Middle-aged adults may have more depressive episodes, decreased libido, middle-of-the-night insomnia, or early morning waking. They often report stomach problems, such as diarrhea or constipation.

- Older adults often feel sadness, grief, or other less obvious symptoms. They may report a lack of emotions rather than a depressed mood. Older adults are also more likely to have other medical conditions or pain that can cause or contribute to depression. Memory and thinking problems (called pseudodementia) may be prominent in severe cases.

Depression can also look different in men versus women, such as the symptoms they show and the behaviors they use to cope with them. For instance, men (as well as women) may show symptoms other than sadness, instead seeming angry or irritable.

For some people, symptoms manifest as physical problems (for example, a racing heart, tightened chest, chronic headaches, or digestive issues). Many men are more likely to see a health care provider about these physical symptoms than their emotional ones. While increased use of alcohol or drugs can be a sign of depression in any person, men are also more likely to use these substances as a coping strategy.

How is depression treated?

Depression treatment typically involves psychotherapy (in person or virtual), medication, or both. If these treatments do not reduce symptoms sufficiently, brain stimulation therapy may be another option.

Choosing the right treatment plan is based on a person’s needs, preferences, and medical situation and in consultation with a mental health professional or a health care provider. Finding the best treatment may take trial and error.

For milder forms of depression, psychotherapy is often tried first, with medication added later if the therapy alone does not produce a good response. People with moderate or severe depression usually are prescribed medication as part of the initial treatment plan.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy (also called talk therapy or counseling) can help people with depression by teaching them new ways of thinking and behaving and helping them change habits that contribute to depression. Psychotherapy occurs under the care of a licensed, trained mental health professional in one-on-one sessions or with others in a group setting.

Psychotherapy can be effective when delivered in person or virtually via telehealth. A provider may support or supplement therapy using digital or mobile technology, like apps or other tools.

Evidence-based therapies to treat depression include cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Using other forms of psychotherapy, such as psychodynamic therapy, for a limited time also may help some people with depression.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) : With CBT, people learn to challenge and change unhelpful thoughts and behaviors to improve their depressive and anxious feelings. Recent advances in CBT include adding mindfulness principles and specializing the therapy to target specific symptoms like insomnia.

- Interpersonal therapy (IPT) : IPT focuses on interpersonal and life events that impact mood and vice versa. IPT aims to help people improve their communication skills within relationships, form social support networks, and develop realistic expectations to better deal with crises or other issues that may be contributing to or worsening their depression.

Learn more about psychotherapy .

Antidepressants are medications commonly used to treat depression. They work by changing how the brain produces or uses certain chemicals involved in mood or stress.

Antidepressants take time—usually 4−8 weeks—to work, and problems with sleep, appetite, and concentration often improve before mood lifts. Giving a medication a chance to work is important before deciding whether it is right for you.

Treatment-resistant depression occurs when a person doesn’t get better after trying at least two antidepressants. Esketamine is a medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment-resistant depression. Delivered as a nasal spray in a doctor’s office, clinic, or hospital, the medication acts rapidly, typically within a couple of hours, to relieve depression symptoms. People will usually continue to take an antidepressant pill to maintain the improvement in their symptoms.

Another option for treatment-resistant depression is to combine an antidepressant with a different type of medication that may make it more effective, such as an antipsychotic or anticonvulsant medication.

All medications can have side effects. Talk to a health care provider before starting or stopping any medication. Learn more about antidepressants .

Note : In some cases, children, teenagers, and young adults under 25 years may experience an increase in suicidal thoughts or behavior when taking antidepressants, especially in the first few weeks after starting or when the dose is changed. The FDA advises that patients of all ages taking antidepressants be watched closely, especially during the first few weeks of treatment.

Information about medication changes frequently. Learn more about specific medications like esketamine, including the latest approvals, side effects, warnings, and patient information, on the FDA website .

Brain stimulation therapy

Brain stimulation therapy is an option when other depression treatments have not worked. The therapy involves activating or inhibiting the brain with electricity or magnetic waves.

Although brain stimulation therapy is less frequently used than psychotherapy and medication, it can play an important role in treating depression in people who have not responded to other treatments. The therapy generally is used only after a person has tried psychotherapy and medication, and those treatments usually continue. Brain stimulation therapy is sometimes used as an earlier treatment option when severe depression has become life-threatening, such as when a person has stopped eating or drinking or is at a high risk of suicide.

The FDA has approved several types of brain stimulation therapy. The most used are electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Other brain stimulation therapies are newer and, in some cases, still considered experimental. Learn more about brain stimulation therapies .

Natural products

The FDA has not approved any natural products for treating depression. Although research is ongoing and findings are inconsistent, some people report that natural products, including vitamin D and the herbal dietary supplement St. John’s wort, helped their depression symptoms. However, these products can come with risks, including, in some cases, interactions with prescription medications.

Do not use vitamin D, St. John’s wort, or other dietary supplements or natural products without first talking to a health care provider. Rigorous studies must test whether these and other natural products are safe and effective.

How can I take care of myself?

Most people with depression benefit from mental health treatment. Once you begin treatment, you should gradually start to feel better. Go easy on yourself during this time. Try to do things you used to enjoy. Even if you don’t feel like doing them, they can improve your mood.

Other things that may help:

- Try to get physical activity. Just 30 minutes a day of walking can boost your mood.

- Try to maintain a regular bedtime and wake-up time.

- Eat regular, healthy meals.

- Do what you can as you can. Decide what must get done and what can wait.

- Connect with people. Talk to people you trust about how you are feeling.

- Delay making important life decisions until you feel better. Discuss decisions with people who know you well.

- Avoid using alcohol, nicotine, or drugs, including medications not prescribed for you.

How can I find help for depression?

You can learn about ways to get help and find tips for talking with a health care provider on the NIMH website.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) also has an online tool to help you find mental health services in your area.

How can I help a loved one who is depressed?

If someone you know is depressed, help them see a health care provider or mental health professional. You also can:

- Offer support, understanding, patience, and encouragement.

- Invite them out for walks, outings, and other activities.

- Help them stick to their treatment plan, such as setting reminders to take prescribed medications.

- Make sure they have transportation or access to therapy appointments.

- Remind them that, with time and treatment, their depression can lift.

What are clinical trials and why are they important?

Clinical trials are research studies that look at ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions. These studies help show whether a treatment is safe and effective in people. Some people join clinical trials to help doctors and researchers learn more about a disease and improve health care. Other people, such as those with health conditions, join to try treatments that aren’t widely available.

NIMH supports clinical trials across the United States. Talk to a health care provider about clinical trials and whether one is right for you. Learn more about participating in clinical trials .

For more information

Learn more about mental health disorders and topics . For information about various health topics, visit the National Library of Medicine’s MedlinePlus .

The information in this publication is in the public domain and may be reused or copied without permission. However, you may not reuse or copy images. Please cite the National Institute of Mental Health as the source. Read our copyright policy to learn more about our guidelines for reusing NIMH content.

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health NIH Publication No. 24-MH-8079 Revised 2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 June 2022

Loneliness associates strongly with anxiety and depression during the COVID pandemic, especially in men and younger adults

- Olivier D. Steen 1 ,

- Anil P. S. Ori 1 , 2 ,

- Klaas J. Wardenaar 1 &

- Hanna M. van Loo 1

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 9517 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4922 Accesses

13 Citations

41 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Loneliness is associated with major depressive disorder (MDD), and likely also with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). It is unclear if these associations are moderated by age, sex, or genetic susceptibility for MDD. We included 75,279 individuals from the Lifelines COVID-19 study, a longitudinal study of a Dutch population-based cohort. Participants completed up to sixteen digital questionnaires between March 2020 and January 2021, yielding a total of 616,129 observations. Loneliness was assessed with the Three-Item Loneliness Scale, and MDD and GAD with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. We used generalized estimating equations to investigate the association between loneliness and MDD and GAD, and whether this association varied across time, age, sex and MDD polygenic risk. Loneliness was strongly associated with all MDD and GAD outcomes. Individuals with the highest loneliness scores were around 14 times more likely to have MDD, and 11 times more likely to have GAD, compared to individuals who reported the least loneliness. The association between loneliness and MDD symptoms was stronger in men, younger individuals, and increased across time. While MDD polygenic risk predicted MDD and GAD outcomes, we did not find an interaction effect with loneliness. Our study, which is the largest to date, confirms that loneliness is an important risk factor for MDD, GAD, depressive and anxiety symptoms, especially in men and younger individuals. Future studies should investigate the mechanisms of these associations and explore loneliness-based interventions to prevent and treat MDD and GAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Joseph M. Rootman, Pamela Kryskow, … Zach Walsh

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

Joanna Moncrieff, Ruth E. Cooper, … Mark A. Horowitz

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Joseph M. Rootman, Maggie Kiraga, … Zach Walsh

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are two of the most common mental illnesses worldwide, with substantial morbidity and mortality 1 , 2 . Gaining a better understanding of the mechanisms that underlie their development is important to reduce the burden of these illnesses. The identification of modifiable risk factors is of particular interest because they provide targets for intervention.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of loneliness as a modifiable risk factor for MD 3 . Loneliness is the subjective negative experience of deficient social relationships and is distinct from objective social isolation 4 . Research on loneliness and depression indicates a bidirectional relationship between both constructs, with greater experienced loneliness predicting future depressive symptoms, and vice versa 5 . Furthermore, loneliness influences the course of MDD, impeding the chances of recovery 6 . Recent findings furthermore suggest an association between loneliness and GAD as well, but fewer studies have been performed 7 , 8 .

However, it is not clear which groups are most vulnerable to the effect of loneliness on depression and anxiety. Different factors may moderate this association, including sex, age and genetic susceptibility. Findings regarding age are mixed. Some studies suggest an increased vulnerability in younger individuals, but few studies included sufficient numbers of adolescents and children to reliably demonstrate this 9 , 10 . Whether sex moderates the effect of loneliness is also unclear. One study found the effect of loneliness on depression to be more pronounced in men 5 , while others did not observe a moderating effect 9 . Thus, it remains inconclusive whether age or sex moderate the association between loneliness and depression and anxiety outcomes.

Furthermore, the association between loneliness and depressive and anxiety outcomes may be influenced by genetic factors. Loneliness, MDD, and GAD have moderate heritability, which means that genetic factors contribute to their aetiology 11 , 12 , 13 . Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple overlapping regions in the genome which are associated with both experiencing loneliness 14 and developing MDD 15 , 16 . This genetic overlap suggests that loneliness and depression could have a shared genetic aetiology, or that individuals with a higher genetic risk for MDD could be more sensitive to developing depression after exposure to loneliness.

The COVID-19 pandemic offers a unique situation to study the relationship of loneliness with depression and anxiety. The COVID-19 pandemic, and subsequent lockdowns, have had a profound impact on social relationships and increased the prevalence of loneliness 3 , 17 , 18 . This is akin to a natural experiment: a large share of the population is subjected to sustained loneliness, and not only subjects with a psychiatric history or other specific groups. Some studies have investigated the impact of loneliness on anxiety and depression amidst the COVID pandemic, and report an association between loneliness and anxiety and depression 19 , with young women most at risk 20 , but their findings are challenging to interpret due to the use of unrepresentative and smaller samples. The present study makes use of the Lifelines Cohort Study, which represents a large multi-generational population-based study in the North of the Netherlands with repeated and structured assessments of loneliness, MDD and GAD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here, we investigate the association of loneliness with depression and anxiety, as well as moderators of this association, in the largest study to date on this relationship.

Lifelines COVID-19 cohort

Data were derived from the Lifelines COVID-19 study, a longitudinal extension of the Lifelines cohort 21 . Lifelines is a large multidisciplinary prospective population-based cohort that monitors the health and health-related behaviours in a detailed manner of 167,729 persons living in the North of the Netherlands. The cohort consists primarily (98%) of white Dutch native people 22 , 23 . All subjects provided written informed consent for participation in Lifelines, and the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen approved the study protocol.

Starting on March 30th 2020, Lifelines invited all adult participants of whom an email address was known (n = 139,679) to participate in the first COVID-19 digital questionnaire, which assessed somatic and mental health, COVID-19 infection status, and loneliness, among other domains. The first questionnaire was distributed on March 30, 2020. The first six questionnaires (Q1–Q6) were sent out weekly with items assessing participants' experiences in the 7 days prior to filling out the questionnaire. Starting from Q7, questionnaires were sent biweekly or monthly, with items assessing participants’ experiences in the 14 days prior to assessment (Supplementary Table A ). A further description of the Lifelines COVID-19 cohort can be found elsewhere 24 .

Data from the first nineteen consecutive assessments (March 30th, 2020, to January 29th, 2021) were available. Questionnaires eleven, twelve and thirteen did not include measures of loneliness, so data from these measurements were not included in our analyses. A total of n = 75,279 individuals participated in at least one of the remaining sixteen questionnaires and are included in this study. In some instances (n = 14,763), participants completed multiple different assessments on the same date. In this case, we included only the questionnaire completed first.

Measurements

Depression and anxiety outcomes.

Symptoms of GAD and MDD were assessed with a self-report digital questionnaire based on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) 25 , which assesses all symptoms that are part of the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Symptoms that are part of both MDD and GAD (being easily fatigued, difficulty concentrating and sleep disturbance) were assessed once in every questionnaire to avoid repetition.

The presence of current MDD and GAD were established according to the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV. For every questionnaire, we also calculated a sum score of MDD (range 0–9) and GAD (range 0–7) criterion symptoms, resulting in two outcomes (symptoms and diagnoses) for both MDD and GAD.

The experience of loneliness was assessed through the previously validated three-item UCLA scale 26 . This scale consists of three items (‘How often do you feel that you lack companionship?’, ‘How often do you feel left out?’ and ‘How often do you feel isolated from others?’), with a three-point (0–2) Likert scale. We calculated a loneliness sum score ranging from 0 to 6, with 6 being the maximum score.

Demographic variables

Age was defined as subjects’ age when completing the first questionnaire. The sex variable refers to biological sex assigned at birth, which was determined by linking the Lifelines data to information stored in personal records of the municipalities in the Netherlands.

Polygenic risk score

We calculated MDD polygenic risk scores (PRS) in 19,128 subjects who had genotype data available. MDD PRS was constructed as a weighted sum of risk alleles for MDD with weights defined as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) effect sizes derived from the meta-analysis of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) and UKBiobank GWASs 15 . The Lifelines sample was not included in the base GWAS, but was used as a target sample to calculate PRS for each participant. Details of PRS calculation are discussed in Supplementary Methods .

Missing data

While all subjects were invited to participate in all assessments, few completed all 16 assessments. Out of 75,279 subjects, 11,528 (15.3%) completed one assessment, 54,409 (72.3%) completed > 1 and < 16 assessments, and 9342 (12.4%) completed all assessments. As expected, there were thus a large number of non-responses for different time points.

Some data were missing due to design choices of the questionnaire (e.g., suicidal ideation was not assessed in every instance). As the questionnaire was web-based, some data were missing due to technical glitches (e.g., a failing internet connection on the participants’ end). Further details on missing data are provided in the Supplementary Methods , while rates of missing data are reported in Supplementary Table B .

As missing data were limited, we implemented multivariate imputation by chained equation (MICE) to impute missing data in one dataset 27 . For imputation, all available data, including data on loneliness, lifetime history of MDD and GAD and accompanying age of onset and number of experienced episodes, stressful life events, and the NEO personality inventory neuroticism score that were collected in previous Lifelines assessments, were used as predictors in MICE. Items were only imputed if a participant filled out other items on that specific questionnaire. Questionnaires with a non-response (i.e. complete missing data) were not imputed. Detailed imputation parameters are presented in Supplementary Methods .

Statistical methods

Model specification.

We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) to investigate the association between loneliness and the four depression and anxiety outcomes. GEE is a technique for estimating parameters of a generalized linear model with correlated measurements, yielding population-averaged coefficients. Because our data included repeated measurements within subjects, we used an exchangeable working correlation structure to account for the dependence of measurements within individuals. A further description of GEE can be found elsewhere 28 .

We performed GEE Poisson regression for the sum scores of MDD and GAD symptoms as both of these outcomes were count-variables. We used GEE logistic regression for the dichotomous outcomes of MDD and GAD. The fitted models included a linear and squared effect of time to account for seasonality. Furthermore, we included loneliness, age and sex as main effects. We added an interaction term between loneliness and time to investigate a possible change in the impact of loneliness on MDD and GAD outcomes across the study duration. We furthermore added interaction terms between loneliness and age, and loneliness and sex (main model) to identify possible moderating effects of age and/or sex. For the model including PRS in participants with genetic data available, we also added a main effect for MDD polygenic risk to the model, as well as an interaction term of PRS with loneliness. Furthermore, for the model including PRS, we included ten principal components as model terms to account for population structure confounding.

Multiple testing correction was implemented by Bonferroni correction. We conducted ten hypothesis tests across four outcomes, yielding a total of 40 hypothesis tests and a Bonferroni-corrected alpha of 0.00125. We performed GEE using the ‘geepack’ R package version 1.3.2 29 , and all analyses were performed in R version 4.0.3 30 .

Sensitivity analyses

Attrition bias.

Individuals experiencing much loneliness, or who suffer from mental illnesses, may more likely be lost to attrition in longitudinal studies 31 . To determine if results were sensitive to attrition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with individuals who participated at least three times across three intervals covering the entire study duration. As assessment dates were variable, we constructed these intervals in such a way that the number of assessments was equal across intervals. The first time interval covered the period March 30, 2020 until 29 April 2020. The second interval covered the interval of 30 April 2020 until 10 July 2020. The third interval covered 10 July 2020 until 31 January 2021. 42,001 (55.8%) participants had completed at least one assessment in each of the three intervals and were included in this sensitivity analysis. Participants in this subsample completed a median of 13 [IQR 10–15] responses.

Family structure

Lifelines is a multi-generational sample and includes family members, which means that our longitudinal data were not only nested within individuals, but also within families. GEE cannot appropriately account for correlated measurements across multiple levels of clustering 28 . Therefore, to test whether our results were influenced by pedigree structures, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in a subsample consisting of one randomly selected subject for every family. As there were 42,089 pedigrees part of the present study, this analysis included 42,089 (55.9%) subjects.

For both sensitivity analyses, we estimated models in the full sample, and in the sample with PRS data available. Because only a limited number of participants had PRS data available, subsamples in the sensitivity analyses are comparatively small (n = 10,955 and n = 7036), and possibly underpowered to detect interaction effects. The latter was therefore only used to test the robustness of a possible interaction term between loneliness and PRS.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects provided written informed consent for participation in Lifelines, and the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen approved the study protocol. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Characteristics of the study population

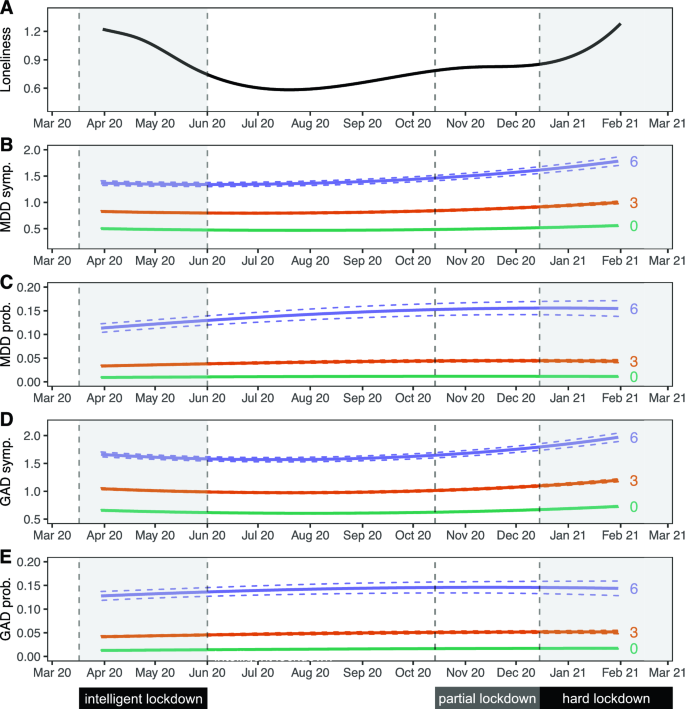

The 75,279 individuals included in this study completed a total of 616,129 assessments across 16 time points. Out of these individuals, 19,128 (25.4%) had genotype data available. The median number of collected questionnaires per individual was 8 (IQR 3–14) (Table 1 ). The mean age at first assessment was 53.7 (standard deviation 12.9). The majority of participants in the sample were female (60.8%), which is similar to the full Lifelines cohort 23 . MDD was present in 5442 (7.2%) participants and GAD in 6733 (8.9%) participants in the 1/2 weeks preceding at least one questionnaire assessment. Loneliness scores were highest during the start and end of data collection, corresponding to periods of nationwide lockdown as a result of government action in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1 A).

Trajectories of loneliness and MDD and GAD outcomes over time. Shaded areas represent periods during which lockdown measures were enforced in the Netherlands. The first 'intelligent' lockdown consisted of restrictions such as social distancing and bans on public gatherings. During the partial lockdown, some restrictions were reintroduced. The 'hard' lockdown introduced more restrictions and a curfew. ( A ) Marginal GEE effect plot of a GEE model of loneliness scores predicted by a polynomial spline time term. The 95% confidence interval of model-predicted values is not visible because the interval is very small. ( B – E ) Marginal GEE effect plot of predicted counts of MDD symptoms ( B ), odds of MDD diagnoses ( C ), counts of GAD symptoms ( D ) and odds of GAD diagnoses ( E ) across different levels (0/green; lowest, 3/orange; moderate, 6/purple; highest) of loneliness scores. Predicted values represent symptoms counts and diagnosis probabilities, and are based on main model fits (Tables 2 and 3 ). Dashed lines represent a 95% confidence interval of model-predicted values.

Loneliness is associated with MDD and GAD symptoms and diagnoses

We observed an association between loneliness and MDD and GAD. We found that a one-point increase in loneliness was associated with a 55.9% increased odds of MDD, and a 48.9% increased odds of GAD. This means that the group scoring highest on loneliness had a 14.4 times increased odds of MDD and a 10.9 times increased odds of GAD compared to those with the lowest loneliness scores (Tables 2 and 3 , Fig. 1 C, E ). Sensitivity analyses showed that these effects were robust for attrition and family structures (Supplementary Tables D 1-3 and E 1-3).

We found a similar association between loneliness and symptom severity of both MDD and GAD, which was robust across both sensitivity analyses (Tables 2 and 3 ; Fig. 1 B, D ; Supplementary Tables D 1-3 and E 1-3). A one-point increase in loneliness was associated with a 27.5% increase in the number of MDD symptoms, and a 19.9% increase in the number of GAD symptoms. This means that the group scoring highest on loneliness had on average 4.3 times as many MDD symptoms, and 3.0 times as many GAD symptoms, compared to the group with the lowest loneliness score.

We observed a significant interaction between loneliness and time, meaning that the magnitude of the association between loneliness and MDD symptoms increased slightly across time (Tables 2 and 3 , Fig. 1 B,D). A 1 week increment in time was associated with a 0.06% increase in effect size, which corresponds to a 2.4% stronger association between loneliness and MDD symptoms after 10 months (roughly the duration covered by the repeated questionnaires). This interaction effect remained significant in both sensitivity analyses. Taken together, these analyses demonstrate a strong association between loneliness and MDD and GAD outcomes.

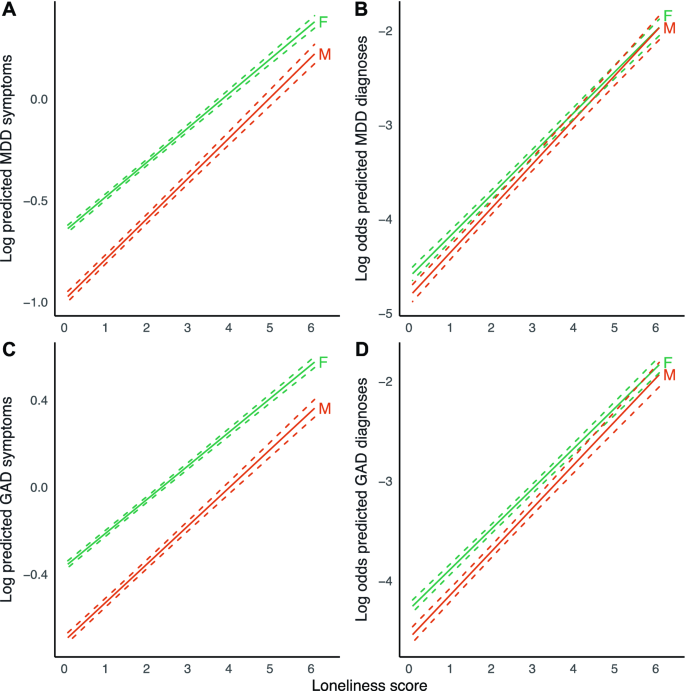

Moderators of the association between loneliness and depression

We found a significant interaction effect of loneliness and sex, indicating that the association between loneliness and MDD symptoms was stronger in men than in women (Table 2 , Fig. 2 ). This effect was consistent across both sensitivity analyses. We observed a similar result for GAD symptoms, but this was not robust in the sensitivity analysis for attrition. We performed a sex-stratified analysis for MDD symptoms to estimate effect sizes for men and women separately (Supplementary Table C 5). Results were in agreement with the main analysis, with a point increase in loneliness score being associated with a 32.1% increase in MDD symptoms in men, compared to 22.5% in women. These analyses suggest that the association between loneliness and symptoms of MDD is stronger in men.

Marginal effect plots of associations between loneliness and MDD and GAD outcomes across sex. Displayed are log predicted counts of MDD symptoms ( A ) and log odds of MDD diagnosis ( B ), as well as log predicted counts of GAD symptoms ( C ) and log odds of GAD ( D ), across different loneliness scores, for men (M) and women (F) (plotted estimates are derived from Tables 2 and 3 , main models). Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals of model-predicted values.

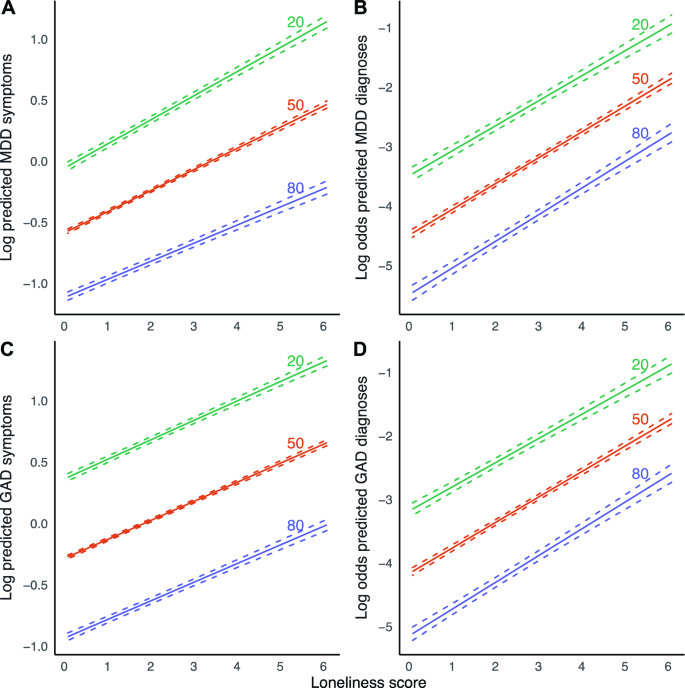

We found a significant interaction effect between loneliness and age for MDD symptoms (Table 2 , Fig. 3 ), indicating that the magnitude of the association between loneliness and MDD symptoms increased slightly across age. This finding was robust across both sensitivity analyses. A 1 year increment in age was associated with a 0.08% reduction in effect size, which corresponds to a 4.7% weaker association between loneliness and MDD symptoms with a 60-year age difference. A point increase in loneliness is then associated with an increase in the number of MDD symptoms of 25.5% in 20-year-olds, compared to 19.6% in 80-year-olds. We observed no moderating effect of age for the other outcomes.

Marginal effect plots of associations between loneliness and MDD and GAD outcomes across age. Displayed are log predicted counts of MDD symptoms ( A ) and log odds of MDD diagnosis ( B ), as well as log predicted counts of GAD symptoms ( C ) and log odds of GAD ( D ), across different loneliness scores, across three levels of age in years (plotted estimates are derived from Tables 2 and 3 , main models). Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals of model-predicted values.

We found a significant main effect of PRS on symptoms of both MDD and GAD, as well MDD and GAD diagnoses, with a one standard deviation increase in PRS Z-score being associated with 26.5% increased odds of MDD, and 20.0% increased odds of GAD. We however did not observe a modifying effect of PRS on the association between loneliness and the four outcomes in any of the models.

Summary of main findings

This study investigated the association between loneliness and (symptoms of) MDD and GAD, and whether this association differs across age, sex and MDD PRS. We found significant associations between loneliness and MDD, GAD, MDD symptoms and GAD symptoms. On average, individuals who experienced the most loneliness were about 14 times more likely to report MDD, and around 11 times more likely to report GAD compared to individuals experiencing the least loneliness. For MDD symptoms, the strength of this association increased across time, becoming ~ 2.4% stronger between April 2020 and February 2021.

The association between loneliness and symptoms of MDD was significantly stronger in men than in women. The association of loneliness and MDD symptoms was also stronger in younger individuals. MDD polygenic risk did not modify the association between loneliness and the different outcomes.

Interpretation of findings and comparison with previous studies

We found a robust association between loneliness and MDD symptom severity. We found a similar association between loneliness and MDD. These findings are in line with multiple previous population-based studies 5 , 9 , 32 , which we now replicate in, to our knowledge, the largest study conducted to date. The strength of the association between loneliness and symptoms of MDD, but not MDD diagnoses, increased across the study duration. This could be due to several reasons. It may, for example, suggest that, as the COVID-19 pandemic lingered on, its influence magnified the effect of loneliness on specific depressive symptoms, but that this increase in symptoms did not necessarily cause a participant to develop MDD. Future studies could test this hypothesis, and assess if loneliness associates with only specific depressive symptoms. Alternatively, although the depressive symptom score and MDD are positively associated, they are distinct phenotypic constructs. MDD will likely display less variation across the period of data collection compared to MDD symptoms. Furthermore, the association of the two constructs with loneliness may also be different. Lastly, the present study may be underpowered to detect a significant interaction term for dichotomous outcomes (MDD), compared to continuous outcomes (MDD symptoms). However, we think that our sample of > 75,000 individuals and > 600,000 measurements should be large enough to trace any interaction effect with a relevant effect size.

We also found a robust association between loneliness and symptoms of GAD as well as GAD diagnoses, which is in line with previous studies 7 , 8 . This could mean that loneliness is a risk factor for GAD, or it could mean that GAD is a risk factor for loneliness or both. We however did not find that this association changed over time, suggesting that the course of the COVID-19 pandemic did not impact the relationship between loneliness and (symptoms of) GAD.

We found that the association between loneliness and depressive symptoms was stronger in men than in women. Results in previous studies were inconsistent. Cacioppo et al. found a stronger association in men in a cross-sectional study of 1939 older adults 5 . However, Lee et al. did not find a moderation effect of sex in a longitudinal study with baseline loneliness as a predictor and depressive symptoms at follow-up as an outcome, in a sample of 4211 older adults 9 . The present study assessed loneliness and outcomes across multiple contemporaneous timepoints. It may be that the moderating effect of sex disappears in time-lagged scenarios—possibly, loneliness has a stronger transient impact in men, without having a stronger effect on sustained depressive symptoms or disorders. Another explanation is that previous studies may not have been sufficiently powered to consistently detect a moderating effect of sex. We stress the importance of conducting such analyses in large population-based samples. Furthermore, differences in study populations, such as demographic, social, and environmental factors could contribute to different study outcomes as well.

We found a modifying effect of younger age on the association between loneliness and MDD symptoms. One previous study conducted in 1006 adults observed a significant interaction effect between loneliness and age on both anxiety and depressive symptoms 10 , while this effect was not found in a sample of 4211 adults above 50 years of age 9 . A lack of young adults in these previous studies may have contributed to these mixed findings. As MDD and GAD often first develop in adolescents or young adults, it is warranted that this age group is included in study cohorts, as is the case for the Lifelines cohort.

The present study did not find a significant moderation effect of MDD PRS on the association between loneliness and anxiety or depression. As far as we know, no comparable studies exist. A previous study by Lee et al. did assess the impact of both loneliness and MDD PRS on the association between loneliness and depression, but only as a confounder, not as an interaction term with loneliness. The authors found that the effect of loneliness persisted also in a model adjusted for PRS 9 . PRS for MDD currently explains only a limited amount of variance (Nagelkerke’s R 2 1.5–3.2%) of MDD 15 , thereby capturing only a small proportion of the heritability. As PRS does not capture the complete genetic architecture of MDD, we cannot exclude that genetic factors may impact the relationship between loneliness and MDD and GAD outcomes. Furthermore, while loneliness and depression share genes and heritability, both constructs likely also have phenotype-specific heritability, while the present study only employed genetic susceptibility for MDD. Perhaps, a PRS for loneliness or a PRS calculated from gene variants shared between the two constructs might be a significant moderator. Future work should revisit such analyses as sample sizes of GWASs, continue to increase. Finally, genetic analyses are worthwhile to explore for GAD and loneliness PRS as well, especially now that larger GWASs have been conducted 14 , 33 .

While loneliness is strongly associated with MDD and GAD outcomes, many individuals experiencing significant loneliness do not develop MDD or GAD. While age and sex explain some of these differences, future research should include other variables as well to further understand how loneliness impacts MDD and GAD. These might include socioeconomic variables, specific environmental variables, or psychological traits related to (tolerance of) loneliness and isolation.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present study is its large sample size and longitudinal design, with repeated measures of loneliness and depression and anxiety outcomes that are measured using multi-item and well-validated instruments.

As our study was conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in the North of the Netherlands, it raises the question of whether our results are generalizable to populations not or no longer affected by the pandemic or to other regions or countries. We think results may be robust, given that the effect sizes of the association between loneliness and MDD and GAD outcomes are comparable to those found in studies conducted before the pandemic and in other populations 5 , 9 .

Because of the initial weekly and later biweekly/monthly assessments of symptoms, we only assessed MDD and GAD symptoms during the past week or 2 weeks. The DSM requires GAD symptoms to be present for 6 months, which means that our GAD diagnoses likely do not correspond to those of the cases seen in clinical practice. A similar point can be made for MDD diagnoses, which require 14 days of symptoms according to the DSM.

The present study focused on contemporaneous associations but did not investigate temporal relations between loneliness and MDD or GAD. While previous longitudinal studies showed that loneliness predicts (symptoms of) MDD 9 , and vice versa 5 , such studies have not yet been performed for GAD. In addition, studies involving loneliness-targeted interventions can further elucidate the causal relevance of loneliness towards depression and anxiety outcomes, besides evaluating its value as a target for treatment.

As we imputed one single dataset, we have sub-optimally accounted for the uncertainty introduced by our missing data handling approach 34 . However, as we had limited missing data and most data were missing by design (i.e., missing completely at random), we deem it unlikely to have significantly influenced our results.

The present study used a GEE marginal model as opposed to a conditional approach such as generalized linear mixed-effects models. The latter approach also allows the estimation of population-averaged estimates and can adjust for multiple correlation structures (such as for correlation within both individuals and families). This approach however was not feasible as it required excessive computational resources given our large sample size. However, in this study, the estimates from GEE models are likely to be in line with results that would have been derived from conditional models. First, estimates obtained from a GEE model agree closely with those from a conditional model if the right assumptions are being met, as is the case for the present study 35 . Second, our sample size was large, which means that we had sufficient power to trace small effects, even with GEE.

Implications

The current study replicates that loneliness is strongly associated with MDD and demonstrates a significant association in a large population-based sample for GAD. We furthermore observed that the association between loneliness and MDD symptoms became stronger over time. As COVID-19-related restrictions have led to more loneliness in the population, this might precipitate a subsequent increase in diagnoses, possibly even as government restrictions are being loosened. Our findings warrant extra vigilance in groups such as younger individuals, who experienced more loneliness.

Besides its association with MDD and GAD, loneliness is strongly predictive of a myriad of adverse health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease and mortality 36 . Currently, few effective interventions are used routinely in clinical practice or the community, while effective interventions do exist 37 , 38 . Furthermore, there is a stigma surrounding loneliness 39 , and it has not received significant attention in clinical practice or policy. This is unfortunate, as its amelioration could entail a large health gain across somatic and mental domains. If nationwide restrictions on social relationships can lead to more loneliness and a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in the population, public health policies aimed at nurturing social interactions may achieve the reverse. Some interventions already exist 37 , 38 , but have not yet been widely employed in clinical or public health settings.

Conclusions

In the largest study on loneliness and mental health to date, we found that loneliness is strongly associated with MDD, GAD and the symptoms thereof during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. The association between loneliness and symptoms of MDD was stronger in men and in younger adults. Finally, we found the association between loneliness and symptoms of MDD to become stronger over time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

All data is available through the Lifelines Cohort Study. Application for data access can be sent to the Lifelines Research Office: https://www.lifelines.nl/researcher/how-to-apply .

Meier, S. M. et al. Increased mortality among people with anxiety disorders: Total population study. Br. J. Psychiatry 209 , 216–221 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Cuijpers, P. & Schoevers, R. A. Increased mortality in depressive disorders: A review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 6 , 430–437 (2004).

Killgore, W. D. S., Cloonan, S. A., Taylor, E. C. & Dailey, N. S. Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 290 , 113117 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cacioppo, J. T. & Hawkley, L. C. Loneliness. (2009).

Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C. & Thisted, R. A. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol. Aging 21 , 140 (2006).

Van Den Brink, R. H. S. et al. Prognostic significance of social network, social support and loneliness for course of major depressive disorder in adulthood and old age. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 27 , 266 (2018).

Beutel, M. E. et al. Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry 17 , 97 (2017).

Domènech-Abella, J., Mundó, J., Haro, J. M. & Rubio-Valera, M. Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). J. Affect. Disord. 246 , 82–88 (2019).

Lee, S. L. et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: A 12-year population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 48–57 (2021).

Hubbard, G., den Daas, C., Johnston, M. & Dixon, D. Sociodemographic and psychological risk factors for anxiety and depression: Findings from the Covid-19 health and adherence research in Scotland on mental health (CHARIS-MH) cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Behav. Med. 28 , 788–800 (2021).

Distel, M. A. et al. Familial resemblance for loneliness. Behav. Genet. 40 , 480–494 (2010).

Sullivan, P. F., Neale, M. C. & Kendler, K. S. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 157 , 1552–1562 (2000).

Hettema, J. M., Neale, M. C. & Kendler, K. S. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 158 , 1568–1578 (2001).

Day, F. R., Ong, K. K. & Perry, J. R. B. Elucidating the genetic basis of social interaction and isolation. Nat. Commun. 9 , 2457 (2018).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Howard, D. M. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 22 , 343–352 (2019).

Wray, N. R. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 50 , 668–681 (2018).

McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H. & Barry, C. L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 324 , 93–94 (2020).

Bu, F., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 265 , 113521 (2020).

Robb, C. E. et al. Associations of social isolation with anxiety and depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of older adults in London. UK. Front. Psychiatry 11 , 991 (2020).

Google Scholar

McQuaid, R. J., Cox, S. M. L., Ogunlana, A. & Jaworska, N. The burden of loneliness: Implications of the social determinants of health during COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 296 , 113648 (2021).

McIntyre, K. et al. Lifelines COVID-19 cohort: Investigating COVID-19 infection and its health and societal impacts in a Dutch population-based cohort. BMJ Open 11 , e044474 (2021).

Scholtens, S. et al. Cohort Profile: LifeLines, a three-generation cohort study and biobank. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44 , 1172–1180 (2015).

Klijs, B. et al. Representativeness of the LifeLines cohort study. PLoS ONE 10 , e0137203 (2015).

Mc Intyre, K. et al. Lifelines COVID-19 cohort: Investigating COVID-19 infection and its health and societal impacts in a Dutch population-based cohort. BMJ Open 11 , e044474 (2021).

Sheehan, D. V. et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59 , 22–33 (1998).

PubMed Google Scholar

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res. Aging 26 , 655–672 (2004).

Azur, M. J., Stuart, E. A., Frangakis, C. & Leaf, P. J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work?. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 20 , 40–49 (2011).

Pekár, S. & Brabec, M. Generalized estimating equations: A pragmatic and flexible approach to the marginal GLM modelling of correlated data in the behavioural sciences. Ethology 124 , 86–93 (2018).

Højsgaard, S., Halekoh, U. & Yan, J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J. Stat. Softw. 15 , 1–11 (2005).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2019).

Nunan, D., Aronson, J. & Bankhead, C. Catalogue of bias: Attrition bias. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 23 , 21–22 (2018).

Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd-Evans, B., Ma, R. & Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 18 , 1–16 (2018).

Levey, D. F. et al. Reproducible genetic risk loci for anxiety: Results from ∼ 200,000 participants in the Million Veteran Program. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 223–232 (2020).

Pedersen, A. B. et al. Missing data and multiple imputation in clinical epidemiological research. Clin. Epidemiol. 9 , 157 (2017).

Hedeker, D., du Toit, S. H. C., Demirtas, H. & Gibbons, R. D. A note on marginalization of regression parameters from mixed models of binary outcomes. Biometrics 74 , 354–361 (2018).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T. & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10 , 227–237 (2015).

Masi, C. M., Chen, H.-Y., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 15 , 219–266 (2011).

Kahlon, M. K. et al. Effect of layperson-delivered, empathy-focused program of telephone calls on loneliness, depression, and anxiety among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 78 , 616–622 (2021).

Rotenberg, K. J. & MacKie, J. Stigmatization of social and intimacy loneliness. Psychol. Rep. 84 , 147–148 (1999).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding for the Lifelines Corona Research project from the University of Groningen and the University Medical Centre Groningen. The authors wish to acknowledge the efforts of the Lifelines Corona Research Initiative and the following initiative participants:

H. M. Boezen 1 , Jochen O. Mierau 2,3 , Lude H. Franke 4 , Jackie Dekens 4,6 , Patrick Deelen 4 , Pauline Lanting 4 , Judith M. Vonk 1 , Ilja Nolte 1 , Anil P.S. Ori 4,5 , Annique Claringbould 4 , Floranne Boulogne 4 , Marjolein X.L. Dijkema 4 , Henry H. Wiersma 4 , Robert Warmerdam 4 , Soesma A. Jankipersadsing 4 , Irene van Blokland 4,7 .

1 Department of Epidemiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. 2 Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. 3 Aletta Jacobs School of Public Health, Groningen, The Netherlands. 4 Department of Genetics, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. 5 Department of Psychiatry, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. 6 Center of Development and Innovation, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. 7 Department of Cardiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

The generation and management of GWAS genotype data for the Lifelines Cohort Study is supported by the UMCG Genetics Lifelines Initiative (UGLI). The authors wish to acknowledge the services of the Lifelines Cohort Study, the contributing research centres delivering data to Lifelines:

Raul Aguirre-Gamboa 1 , Patrick Deelen 1 , Lude Franke 1 , Jan A. Kuivenhoven 2 , Esteban A. Lopera Maya 1 , Ilja M Nolte 3 , Serena Sanna 1 , Harold Snieder 3 , Morris A. Swertz 1 , Judith M. Vonk 3 , Cisca Wijmenga 1 .

1 Department of Genetics, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands. 2 Department of Paediatrics, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands. 3 Department of Epidemiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands

As well as all the study participants.

We thank the UMCG Genomics Coordination Center, the UG Center for Information Technology and their sponsors BBMRI-NL & TarGet for storage and computing infrastructure.

We thank Lian Beijers, Aranka Ballering, Judith Rosmalen and Nord van den Bos for their collaboration and feedback as part of our COVID Psychiatry working group.

The Lifelines Biobank initiative has been made possible by funding from the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG the Netherlands), the University of Groningen, the Northern Provinces of the Netherlands, FES (Fonds Economische Structuurversterking), SNN (Samenwerkingsverband Noord Nederland) and REP (Ruimtelijk Economisch Programma). Hanna M. van Loo was supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation and a VENI grant from the Talent Programme of the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (NWO-ZonMW 09150161810021).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Hanzeplein 1, PO Box 30.001, 9700 RB, Groningen, The Netherlands

Olivier D. Steen, Anil P. S. Ori, Klaas J. Wardenaar & Hanna M. van Loo

Department of Genetics, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Anil P. S. Ori

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

O.D.S., A.P.S.O., H.M.v.L. designed the study. A.P.S.O. and H.M.v.L. were involved in data collection. O.D.S. performed the statistical analyses and primary drafting of the manuscript with critical input from A.P.S.O., K.J.W., and H.M.v.L. A.P.S.O. and H.M.v.L. oversaw the study. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hanna M. van Loo .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Steen, O.D., Ori, A.P.S., Wardenaar, K.J. et al. Loneliness associates strongly with anxiety and depression during the COVID pandemic, especially in men and younger adults. Sci Rep 12 , 9517 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13049-9

Download citation

Received : 09 November 2021

Accepted : 09 May 2022

Published : 09 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13049-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Loneliness, belonging and psychosomatic complaints across late adolescence and young adulthood: a swedish cohort study.

- Karina Grigorian

- Viveca Östberg

- Sara Brolin Låftman

BMC Public Health (2024)

The Association Between Emotion Recognition and Internalizing Problems in Children and Adolescents: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis

- Heting Liang

Journal of Youth and Adolescence (2024)

Het beloop van suïcidaliteit tijdens de coronapandemie in Nederland

- Lizanne J. S. Schweren

- Marjolein Veerbeek

- Renske Gilissen

TSG - Tijdschrift voor gezondheidswetenschappen (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

New Research: Serotonin Does Have a Direct Role in Depression

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence..

Posted November 5, 2022 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- What Is Depression?

- Find a therapist to overcome depression

- There has been no direct evidence that serotonin plays a key role in depression until now.

- New research reported here uses a radioactive tracer and PET scans to show that serotonin activity is lower in people with clinical depression.

- While a small study, this work presents a new paradigm for directly assaying serotonin in psychiatry.

- Future research will seek to replicate or refute these findings and expand studies to larger and more diverse groups.

By Grant H. Brenner

Over the years, the serotonin hypothesis of depression , which suggests that low or impaired serotonin neurotransmission is related to the symptoms and possible causes of depression and related psychiatric disorders, has taken many hits.

Recently, a widely publicized review paper in Nature (Moncrieff et al., 2022) found no direct evidence that serotonin is involved in the pathophysiology of depression. This led to an explosion of reports and even attacks which reverberated across the internet about the serotonin hypothesis, the long-debunked “chemical imbalance” explanation, and, to an extent, psychiatry as a field.

The uproar is understandable–depression affects an estimated 20 million US citizens and nearly 300 million worldwide , and current treatments are only partially effective. There is a growing awareness that mental health problems are epidemic–a recent survey by the American Psychiatric Association found 79 percent of people see mental health as a public health emergency.

Moreover, rates of anxiety and depression are skyrocketing, especially among younger people , suicide has become a leading cause of death, and we are more aware every day of the hazardous effect of endemic stress and trauma on mental and physical health.

Despite various studies over the years and the recognition that antidepressant and psychedelic medications, 1 which improve depression, often increase serotonin levels and are associated with positive brain changes (such as increased neuronal complexity via "sprouting" and possible restoration of brain volume in areas like the hippocampus), there has been a startling lack of evidence showing a direct role for serotonin, perhaps because more sophisticated research methods have not been available.

Absence of Evidence Is Not Evidence of Absence

That is, until now. For the first time, study authors have found a clear association between altered serotonin activity and depression in a robust experimental design.

Researchers Erritzoe and colleagues (2022) report their findings in a recent paper in Biological Psychiatry entitled "Brain Serotonin Release Is Reduced in Patients With Depression." In this study, they compared two groups of people, 17 people with clinical depression (MDD group for major depressive disorder) rigorously diagnosed with depression and free from other conditions, not taking antidepressants at the time of the study (most never had, some had in the past), and 17 people without any mental illness (the HC or healthy control group).

The statistics analyzed clinical data and brain-imaging findings to determine if MDD and HC differed significantly in the serotonin neurotransmission, and if so, in what direction? If MDD showed lower serotonin, or 5HT, activity, this would directly support the serotonin hypothesis of depression.

Study participants were administered a mildly radioactive chemical developed to directly measure serotonin activity in the brain. Rather than the previous studies reviewed in the Nature article, which included indirect measures, using [11C]Cimbi-36 (a "radioligand") allows researchers to probe actual 5HT activity on PET (Positron Emission Tomography) and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scan.

PET is an imaging approach more sophisticated than MRI. Unlike MRI, which produces a lower resolution scan indirectly estimating brain activity (often based on inferred blood flow), PET images positrons (a form of antimatter, antielectrons) to get a fine-grained, direct window into the brain's inner workings.

Why [11C]Cimbi-36? Prior PET studies have shown that when serotonin goes up, [11C]Cimbi-36 predictably and reliably goes down. It’s called a radioligand because the molecule contains a radioactive form of carbon that lights up on PET.

Study participants, in addition to careful clinical diagnosis, completed depression ratings and underwent PET-MRI imaging after being given a dose of d- amphetamine (a drug familiar for its use in treating ADHD and also for its abuse potential as a street drug and misused prescriptions).

Prior research has shown that if we give a dose of d-amphetamine to non-depressed individuals (HCs), [11C]Cimbi-36 levels drop significantly, reflecting an increase in 5HT activity. Is this response the same in people with depression? If not, it would lend new support to the serotonin hypothesis of depression.

The main study result was that in patients with depression, serotonin activity is indeed diminished compared with people without depression. Following d-amphetamine challenge, [11C]Cimbi-36 tracer binding across brain cortex (surface) areas was as expected for healthy individuals, consistent with prior experiments.

However, for depressed participants, a very different pattern emerged. When this group received d-amphetamine, [11C]Cimbi-36 binding was significantly lower than in the non-depressed group, reflecting underlying decreased serotonin activity in depressed patients compared with healthy controls. This activity was seen across many brain regions, reaching statistical significance in the temporal cortex (areas located on the sides of the brain, in rough proximity to the ears 2 ).

The effect was stronger in MDD participants who had never taken antidepressants (" medication naive") versus those who had but were not taking them during the study, but this finding is hard to interpret due to the small number of participants in the prior medication group.

Implications and Future Directions

Overall, this study found diminished serotonin activity in patients with diagnoses of clinical depression. This does not mean that depression is caused by serotonin deficiency or that medications that increase serotonin will treat depression. If only it were that easy.

The picture is much more complex than that, with an array of not only many different serotonin receptors and systems throughout the brain but also many other factors, including but not limited to an array of implicated non-serotonin neurotransmitters (norepinephrine, dopamine , glutamate, GABA, and others), the role of other biological factors and psychosocial factors, and the increasingly recognized role of supporting role of glial cells in brain function–cells which are not neurons but which support and modulate what neurons do. 3

This study is not the end of the discussion but rather a new beginning. It is the first study to show diminished serotonin activity in depression.

However, it is only one study with a relatively small number of participants, and as with any study requires replication to determine if it is really true and to build in more nuance to the study design to account for potential confounding factors (like time of day, clinical presentation in a more diverse population, the role of serotonin in disorders which overlap with depression, and so on).

In addition to the main finding that people with depression do have lower serotonin activity compared with those without depression, at least here, this work is important because it is proof of concept for a study approach to directly assess brain serotonin activity. This approach can and will be refined–for example, using challenges other than with d-amphetamine to perturb serotonin tracer activity.

Nevertheless, it is a powerful tool and one which, along with others under development such as computational tools to develop better ways of understanding psychiatric conditions (“ transdiagnostic approaches "), 4 will help to usher in a new era, with the expectation that growing understanding will enable more effective treatment and ultimate reduce the considerable suffering associated with mental illness.

Facebook image: Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

1. Serotonin is also implicated in psychedelic medications, including psilocybin ("magic mushrooms") and LSD–however, the psychedelic effect may be different from the antidepressant effect (Kaplan et al., 2022), suggesting that aside from depression as a mental illness, culturally we may be looking for ways to break out of conventional, restrictive ways of thinking while folding this need into a medicalized view of human experience.

2. 3D Brain Online

3. A recent study found that astrocytes, a supporting cell in the brain, actually pull back part of their cell bodies ("leaflets") to expose the gap between neurons (the "synapse"), which in turn facilitates glutamate transmission involved in fear-based learning!

4. A recent paper discusses evolving diagnostic approaches in psychiatry: Identifying transdiagnostic mechanisms in mental health using computational factor modeling

Erritzoe D. CA, Searle G., Lewis Y., Passchier J., Azeem S., Beaver J., Nutt D., Knudsen G., Gunn R., Rabiner E. (2017): Serotonin release measured in the human brain: A PET study with [11C]Cimbi-36 and d-amphetamine challenge. BrainPET 2017. Berlin, Germany.

Erritzoe D., Godlewska B.R., Rizzo G., Searle G.E., Agnorelli C., Lewis Y., Ashok A.H., Colasanti A., Boura I., Farrell C., Parfit H., Howes O., Passchier J., Gunn R.N., Nutt D.J., Cowen P.J, Knudsen G. & Rabiner E.A., BRAIN SEROTONIN RELEASE IS REDUCED IN PATIENTS WITH DEPRESSION: A [11C]Cimbi-36 PET STUDY WITH A D-AMPHETAMINE CHALLENGE., Biological Psychiatry (2022), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.10.012 .

Kaplan, A.L., Confair, D.N., Kim, K. et al. Bespoke library docking for 5-HT2A receptor agonists with antidepressant activity. Nature 610, 582–591 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05258-z

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Obligatory Disclaimer: This Blog Post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third-party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Grant H. Brenner/Neighborhood Psychiatry & Wellness/The Collective - Integrated Behavioral Health. All rights reserved.

SOL Mental Health is a practice of medical professionals, therapists, wellness experts, and administrative support staff dedicated to providing compassionate, conscientious care. We strive to constantly improve patient experience and raise the overall standard of what patients seeking mental health care receive.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy