Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 15 May 2003

Parallel extinction risk and global distribution of languages and species

- William J. Sutherland 1

Nature volume 423 , pages 276–279 ( 2003 ) Cite this article

3768 Accesses

203 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

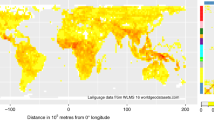

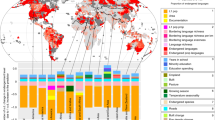

There are global threats to biodiversity with current extinction rates well above background levels 1 . Although less well publicized, numerous human languages have also become extinct, and others are threatened with extinction 2 , 3 . However, estimates of the number of threatened languages vary considerably owing to the wide range of criteria used. For example, languages have been classified as threatened if the number of speakers is less than 100, 500, 1,000, 10,000, 20,000 or 100,000 (ref. 3 ). Here I show, by applying internationally agreed criteria for classifying species extinction risk 4 , that languages are more threatened than birds or mammals. Rare languages are more likely to show evidence of decline than commoner ones. Areas with high language diversity also have high bird and mammal diversity and all three show similar relationships to area, latitude, area of forest and, for languages and birds, maximum altitude. The time of human settlement has little effect on current language diversity. Although similar factors explain the diversity of languages and biodiversity, the factors explaining extinction risk for birds and mammals (high altitude, high human densities and insularity) do not explain the numbers of endangered languages.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The ecological drivers of variation in global language diversity

Xia Hua, Simon J. Greenhill, … Lindell Bromham

The network nature of language endangerment hotspots

Nala H. Lee, Cynthia S. Q. Siew & Nadine H. N. Ng

Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity

Lindell Bromham, Russell Dinnage, … Xia Hua

Chapin, F. S. et al. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 405 , 234–242 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Krause, M. The world's languages in crisis. Language 68 , 4–10 (1992)

Article Google Scholar

Crystal, D. Language Death (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2000)

Book Google Scholar

IUCN/SSC. Red List Categories and Criteria (IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland, 1994)

Google Scholar

Lande, R. Risks of population extinction from demographic and environmental stochasticity and random catastrophes. Am. Nat. 142 , 911–927 (1993)

Stephens, P. A. & Sutherland, W. J. Consequences of the Allee effect for ecology and conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14 , 401–405 (1999)

Saccheri, I. et al. Inbreeding and extinction in a butterfly population. Nature 392 , 491–494 (1998)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Grimes, B. F. (ed.) Ethnologue: Languages of the World , 14th edn (Summer Institute of Linguistics, Dallas, Texas, 2000)

Birdlife International. Threatened Birds of the World (Lynx Edicions and Birdlife International, Barcelona and Cambridge, 2000).

Balmford, A. et al. Conservation conflicts across Africa. Science 291 , 2616–2619 (2001)

Myers, N. et al. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403 , 853–858 (2000)

Nettle, D. Linguistic Diversity (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1999)

Nettle, D. Explaining global patterns of language diversity. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 17 , 354–374 (1998)

Mace, R. & Pagel, M. A latitudinal gradient in the density of human languages in North America. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 261 , 117–121 (1995)

Article ADS Google Scholar

Morre, J. L. et al. The distribution of cultural and biological diversity in Africa. Proc R. Soc. Lond. B 269 , 1645–1653 (2002)

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P. & Piazza, A. The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1994)

MATH Google Scholar

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. Genes, Peoples and Languages (Penguin, London, 2001)

Nettle, D. Linguistic diversity of the Americas can be reconciled with a recent colonization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96 , 3325 (1999)

Groombridge, B. & Jenkins, M. D. Global Biodiversity (World Conservation Press, Cambridge, 2000)

FAO. State of the World's Forests 2001 (Food and Agriculture Organisation, Rome, 2000)

World Factbook 2002 〈 http://www.worldbank.org 〉.

Mitchel, T., Hulme, M. & Newl, M. Climate data for political areas. Area 34 , 109–112 (2002)

The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World (Times Books, London, 1999)

Brooks, T. in Threatened Birds of the World (eds Birdlife International) 701–708 (Lynx Edicions and Birdlife International, Barcelona and Cambridge, 2000)

Download references

Acknowledgements

I thank I. Côté, C. Crockford, R. Freckleton, J. Gill, P. Stephens and A. Watkinson for very useful comments.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Conservation, School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, NR4 7TJ, Norwich, UK

William J. Sutherland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to William J. Sutherland .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares that he has no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sutherland, W. Parallel extinction risk and global distribution of languages and species. Nature 423 , 276–279 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01607

Download citation

Received : 03 December 2002

Accepted : 21 March 2003

Issue Date : 15 May 2003

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01607

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Ecological discourse as a new indicator for improving individual ecological behaviour in environmental protection: an ecolinguistic continuum perspective.

- Weiwei Zhang

- Hao-Zhang Xiao

Environment, Development and Sustainability (2023)

- Lindell Bromham

- Russell Dinnage

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2021)

Traditional knowledge in semi-rural close to industrial areas: ethnobotanical studies in western Gironès (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula)

- Ginesta Serrasolses

- Teresa Garnatje

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2019)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Handbook of Research Ethics and Scientific Integrity pp 1–13 Cite as

Linguistics: Community-based Language Revitalization

Community-based language revitalization

- Nariyo Kono 2

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 14 September 2019

258 Accesses

1 Citations

11 Altmetric

This chapter explores ethical aspects of research in a field within linguistics that has developed in just the last several decades: “Language Maintenance and Revitalization.” According to Austin and Sallabank (Cambridge handbook of endangered languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2011), currently, about 7000 languages are spoken worldwide, and 50–70% of them will be extinct by 2020. The latest version of the online UNESCO Atlas (2010) captured about 2500 endangered languages out of an estimated total of 3000. The field of endangered languages has attracted wide attention from linguists as well as general public for the last several decades. This chapter focuses on aspects of ethical research surrounding the Indigenous language maintenance and revitalization area, in particular regarding the aspect of participants’ language ownership, highlighting some of the core ethical aspects by examining the history of community practices and community-based research.

- Indigenous languages

- Language maintenance and revitalization

- Linguistics

- Community-based learning

- Empowerment

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Akumbu PW (2018) Babanki literacy classes and community-based language research. In: Bischoff S, Jane C (eds) Insights from practices in community-based research: from theory to practice around the globe. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, pp 266–279

Chapter Google Scholar

American Academy of Arts & Sciences (2017) The future of undergraduate education: the future of America. Final report and recommendations from the commission on the future of undergraduate education, Cambridge, MA

Google Scholar

Austin P (2010) Communities, ethics and rights in language documentation. In: Austin P (ed) Language documentation and description, vol 7. School of Oriental and African Studies, London, pp 34–54

Austin P, Sallabank J (2011) Cambridge handbook of endangered languages. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Bath H (2008) The three pillars of trauma-informed care. Reclaiming Children and Youth 17(3):17–21

Bianco JL (2015) Ethical dilemmas and LP advising. In: De Costa PI (ed) Ethics in applied linguistics research. Routledge, New York, pp 83–100

Bischoff ST, Jany C (eds) (2018) Insights from practices in community-based research: from theory to practice around the globe. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin

Cameron D, Frazer E, Harvey P, Rampton MBH, Richardson K (1992) Researching language: issue of power and method. Routledge, London

Chirkova K (2018) Revitalization of Duoxu. In: Hinton L, Huss L, Roche G (eds) The Routledge handbook of language revitalization. Routledge, New York, pp 446–454

Denzin NK (2003) Performance ethnography: critical pedagogy and the politics of culture. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Denzin NK (2010) Grounded and indigenous theories and the politics of pragmatism. Sociol Inq 80(2):296–312

Article Google Scholar

Eckert P (2015) Ethics in linguistic research. In: Podesva R, Sharma D (eds) Research methods in linguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 11–26

Fishman JA (1991) Reversing language shift: theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened languages. Multilingual Matters, Clevedon

Fitzgerald CM (2007) 2006 presidential address: Indigenous languages and Spanish in the United States: how can/do linguists serve communities? Southwest J Linguist 26(1):1+. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A176592040/AONE?u=s1185784&sid=AONE&xid=da022b5c . Accessed 5 Aug. 2019

Fitzgerald CM (2018) Creating sustainable models of language documentation and revitalization. In: Bischoff S, Jane C (eds) Insights from practices in community-based research: from theory to practice around the globe. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, pp 94–111

Gibbons R, Thomas D, Black G (2002) The residential school experience: a century of genocide in the Americas. Mayhew: University of Washington. Native Voices; No Damn Eagles (Firm). Native voices at the University of Washington, Seattle

Himmelmann N (1998) Documentary and descriptive linguistics. Linguistics 36:161–195

Hinton L, Huss L, Roche G (2018) The Routledge handbook of language revitalization. Routledge, New York

Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C (2009) Community-based participatory research: an approach to intervention research with a native American community. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 27(3):162–175

Hornberger NH (2011) Dell H. Hymes: his scholarship and legacy in anthropology and education. Anthropol Educ Q 42(4):310–318

Hymes D (1996) Ethnography, linguistics, narrative inequality: toward an understanding of voice. Taylor and Francis, London

Kono N (2010) Gifts of master-apprenticeship: development of the revitalizing endangered indigenous languages (REIL) certificates. In: Galla CK (ed) American Indian language development institute: thirty year tradition of speaking from our heart. American Indian Language Development Institute. University of Arizona, Tucson

Kono N (2013) Ethics in research. In: Chapelle CA (ed) The encyclopedia of applied linguistics, vol 4. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, pp 2014–2024

Kramsch C, Whiteside A (2007) Three fundamental concepts in second language acquisition and their relevance in multilingual contexts. Mod Lang J 91(5):907–922

Kroskrity PV, Field MC (eds) (2009) Native American language ideologies: beliefs, practices, and struggles in Indian Country. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson

Leonard WY, Haynes E (2010) Making “collaborative” relationship collaborative: an examination of perspectives of that frame linguistic field research. Lang Doc Con 4(2010):268–293

Mercier A (2014) Trauma-informed research and planning: understanding government and urban native community partnerships to addressing substance-exposed pregnancies in Portland, OR. Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1803

Nind M (2014) What is inclusive research? Bloomsbury Academic, London

Rice K (2006) Ethical issues in linguistic fieldwork: an overview. Journal Acad Ethics 4(Springer):123–155

Rice K (2018) Collaborative research: visions and realities. In: Bischoff S, Jane C (eds) Insights from practices in community-based research: from theory to practice around the globe. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin, pp 13–37

San Code of Research Ethics (2017). http://www.globalcodeofconduct.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/San-Code-of-RESEARCH-Ethics-Booklet_English.pdf

Smith LT (1999) Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books, London

Thieberger N, Jones C (2017) Indigenous linguistics and cultural heritage ethics policy. ARC Centre of excellence for the dynamics of language. http://www.dynamicsoflanguage.edu.au/research/indigenous-linguistics-and-cultural-heritage-ethics-policy/ . Accessed 17 Oct 2018

Thieberger N, Musgrave S (2007) Documentary linguistics and ethical issues. In: Austin PK (ed) Language documentation and description, vol 4. SOAS, London, pp 26–37

Thorne SL, Suelmann S, Charles W (2015) Ethical issues in indigenous language research and interventions. In: De Costa PI (ed) Ethics in applied linguistics research. Routledge, New York, pp 142–160

United Nations Educational, Scientific, Cultural Organization (2010) UNESCO Atlas of the World languages in danger. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/endangered-languages/atlas-of-languages-in-danger/

Whalen DH, Moss M, Baldwin D (2016) Healing through language: positive physical health effects of indigenous language use. [version 1; referees: 2 approved with reservations]. F1000Research 5:852. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.8656.1 . Accessed 17 Oct 2018

Yamada R-M (2007) Collaborative linguistic fieldwork: practical application of the empowerment model. Lang Doc Con 1(2):257–282

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Public Service and University Studies, Portland State University, OR, USA

Nariyo Kono

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nariyo Kono .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Chatelaillon Plage, France

Ron Iphofen

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Kono, N. (2019). Linguistics: Community-based Language Revitalization. In: Iphofen, R. (eds) Handbook of Research Ethics and Scientific Integrity. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76040-7_45-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76040-7_45-1

Received : 14 April 2019

Accepted : 23 April 2019

Published : 14 September 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-76040-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-76040-7

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Religion and Philosophy Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Evolution of the Ainu Language in Space and Time

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Cognitive and Behavioral Science, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- Sean Lee,

- Toshikazu Hasegawa

- Published: April 26, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243

- Reader Comments

Languages evolve over space and time. Illuminating the evolutionary history of language is important because it provides a unique opportunity to shed light on the population history of the speakers. Spatial and temporal aspects of language evolution are particularly crucial for understanding demographic history, as they allow us to identify when and where the languages originated, as well as how they spread across the globe. Here we apply Bayesian phylogeographic methods to reconstruct spatiotemporal evolution of the Ainu language: an endangered language spoken by an indigenous group that once thrived in northern Japan. The conventional dual-structure model has long argued that modern Ainu are direct descendants of a single, Pleistocene human lineage from Southeast Asia, namely the Jomon people. In contrast, recent evidence from archaeological, anthropological and genetic evidence suggest that the Ainu are an outcome of significant genetic and cultural contributions from Siberian hunter-gatherers, the Okhotsk, who migrated into northern Hokkaido around 900–1600 years ago. Estimating from 19 Ainu language varieties preserved five decades ago, our analysis shows that they are descendants of a common ancestor who spread from northern Hokkaido around 1300 years ago. In addition to several lines of emerging evidence, our phylogeographic analysis strongly supports the hypothesis that recent expansion of the Okhotsk to northern Hokkaido had a profound impact on the origins of the Ainu people and their culture, and hence calls for a refinement to the dual-structure model.

Citation: Lee S, Hasegawa T (2013) Evolution of the Ainu Language in Space and Time. PLoS ONE 8(4): e62243. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243

Editor: Luísa Maria Sousa Mesquita Pereira, IPATIMUP (Institute of Molecular Pathology and Immunology of the University of Porto), Portugal

Received: January 17, 2013; Accepted: March 19, 2013; Published: April 26, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Lee, Hasegawa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Fellows (248973). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Patterns of linguistic variation among individuals often carry the signature of a speech community's demographic past. Accumulating evidence indicates that languages evolve by a process of descent with modification and they form into distinct families in a manner similar to their speakers forming into different ethnic groups through evolutionary history [1] – [3] . The intertwined history between languages and their speakers appears most vividly in the areas that experienced large-scale population expansions, often driven by agricultural intensification and cultural innovation since the end of the last Ice Age [4] . Recent empirical evidence supporting this phenomenon includes a range of language phylogenies reconstructed with computational methods [5] – [8] .

While the computational phylogenetic methods have been fruitful in shedding new light on language evolution and the speakers’ prehistory, their application has been focused mainly on inferring temporal and sequential aspects. As a result, inferences about the homeland or geographic diffusion pattern often relied on heuristic approaches such as locating a monophyletic outgroup and formulating post-hoc diffusion scenarios from the branching order. Recent progress in phylogenetic methods is, however, producing innovative ways to embed phylogenetic inference in a geographical context, and allow us to explicitly estimate both temporal and spatial aspects of evolution while accounting for phylogenetic uncertainty [9] – [11] . In this paper, we adopt these methodological innovations and directly reconstruct spatiotemporal evolution of the Ainu language: a nearly extinct language spoken by indigenous people of Japan whose origins remain obscure.

Considerable debate surrounds the apparent incompatibility between the conventional model of human prehistory for the Japanese islands and the emerging evidence from modern archaeology, anthropology and genetics. For several decades, the dual-structure model [12] has posited that similarities in dental [13] and cranial features [14] between the Ainu people and Southeast Asians meant that the Ainu ancestry originated in Southeast Asia around 10700 years before present (BP) [15] . Similarly, reconstructed proto-Ainu lexicons have also been suggested to share some similarities with proto-Austroasiatic lexicons [16] . Therefore, the Ainu have long been thought to be direct descendants of a single ancient Southeast Asian lineage, the Jomon, and have remained isolated from neighboring populations throughout the Holocene. However, recent evidence from genetic [17] , [18] , morphological [19] , [20] , and cultural studies [21] are beginning to suggest that the Okhotsk people, a hunter-gatherer group from the Amur river basin, migrated into northern Hokkaido around 900–1600 BP bringing significant genetic and cultural contributions to the preexisting Jomon, and subsequently gave rise to modern Ainu people as well as their culture. In essence, this ‘Okhotsk expansion scenario’ suggests that, far from being direct descendants of a single ancient human lineage that had no contact with the rest of the world, the Ainu and their culture are the outcome of a recent population expansion into northern Hokkaido.

If we accept premises (i) population expansions often leave its signature in the patterns of linguistic variation and (ii) the cultural flow from the incoming Okhotsk people had a profound impact on the language, then we can reason that spatiotemporal reconstruction of the Ainu language evolution might allow us to test the plausibility of the Okhotsk expansion scenario for the Ainu origin, and examine whether or not the dual-structure model should be modified to accommodate the Okhotsk expansion scenario. Accordingly, we predicted that if the scenario were correct, then the estimated root age of the Ainu varieties should coincide with 900–1600 BP, and their geographic distribution should be the end result of expansion from northern Hokkaido, where the gene and cultural flows from the Okhotsk to Jomon is likely to have taken place (blue bar in Figure 1 ). It should be noted that even if the patterns of Okhotsk expansion were correct, the specific processes of language change could be interpreted in two ways (see Discussion for more details). Following the line of reasoning above, we also predicted that if the scenario were incorrect, then the Ainu language diffusion should conform to the conventional scenario and spread northward from southern Hokkaido with the root age being at least several thousand years older than 1600 BP but not beyond 10000 BP, which is the current methodological limit for tracing language ancestry.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Colored circles represent two major subgroups (Green-Hokkaido; Yellow-Sakhalin). Blue bar in the center indicates the main area of the Okhotsk settlement.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.g001

Materials and Methods

The data consist of 19 geocoded lists of 200 basic vocabularies ( Figure 1 ; for a full list of sites, see Figure S1 ) compiled by Hattori and Chiri during 1950s [22] , when there was still a rich linguistic diversity among the Ainu people. The basic vocabularies are a set of words transmitted vertically from one generation to the next [23] , thereby preserving evolutionary signal required for reconstructing phylogenetic history [3] , [24] . Nevertheless, one could argue that the 19 varieties that we analyze here are dialects of the Ainu language and if one supposes that only languages, not dialects, constitute representative units of analysis, then using these varieties implies that the resulting tree may potentially depict a confusing branching pattern with excessive detail, or even fail to recover the actual subdivisions of the speech community [25] .

We do not, however, consider this to be a major obstacle for reconstructing Ainu language evolution for three reasons: (i) a natural model of language evolution that we use here is known to be robust against reasonable levels of noise (i.e., up to 20% of horizontal transfer per 1000 years) [26] , (ii) if we define languages as groups of tongues that are mutually unintelligible in a manner similar to biologists defining species as groups of animals that cannot interbreed [27] , then Swadesh’s criterion of mutual intelligibility (i.e., any two languages being mutually unintelligible if they share less than 90% of their basic vocabularies with each other [28] ) and a matrix of pair-wise cognate similarities of the Ainu varieties [22] allow us to estimate that any one of the varieties would be able to communicate with the rest only about 18% at a time, meaning that the majority of the 19 varieties can actually be considered languages in their own right and (iii) we used SPLITSTREE4 [29] to estimate tree-likeness of the Ainu phylogeny [30] , [31] and obtained the average delta score = 0.25 and Q -residual score = 0.01, both indicating that the evolution of Ainu lexicons was reasonably tree-like, and hence suitable for phylogenetic analysis (to put this in perspective, the tree-likeness scores calculated from a subset of 12 Indo-European languages have similar scores as our 19 Ainu varieties with the average delta score = 0.23 and Q -residual score = 0.03 [31] ). These observations provide us confidence that the data should carry robust evolutionary signal and the 19 Ainu varieties are appropriate units of analysis for the current purpose.

Cognate judgments, a process of revealing shared ancestry among lexicons, are carried out by identifying systematic correspondences in phonetic structure and meaning [25] . For our analyses, we adopted the cognate judgments made by the two linguists who compiled the data [22] . The cognate sets were encoded into binary states indicating presence ('1') or absence ('0') of a cognate, which resulted in 19×350 matrix.

We used BEAST [32] for all analyses because it allows us to reconstruct phylogenies without specifying an a priori outgroup. Continuous random walk model we use in this paper [9] , [33] is a Bayesian expansion of Brownian diffusion model developed in a maximum-likelihood framework [34] . In general, a Brownian diffusion model aims to estimate the vectors of latitudes and longitudes of internal nodes (i.e., common ancestors of extant languages) on a continuous surface, in which increments are independent and normally distributed with a mean centered on zero with variance that scales linearly in time, meaning that diffusion processes are assumed to be homogeneous over time and space. This can be unrealistic as many geographic features (e.g., mountains and rivers) can influence the rate of spread for each branch. Bayesian continuous diffusion model we adopt here effectively overcomes this limitation by relaxing the Brownian process: borrowing ideas from uncorrelated relaxed clock models [35] , the method models branch-specific dispersal processes with the diffusion rate scalar in each branch being drawn independently and identically from a range of parametric distributions. Distributions used in our analyses are (i) Cauchy distribution that has fat tails accommodating long distance dispersals [36] , (ii) gamma distribution that accommodates infinite variance in a manner similar to Lévy flight models [37] but without enforcing power-law tail behavior, and (iii) lognormal distribution that allows even greater degree of rate variability [35] . In order to make our geographic inference more realistic, we sampled the root and node locations only from the land by assigning a prior probability of zero to the water [11] .

In addition, we compared the degree of model-fit between relaxed and strict clocks [35] . Temporal scale of phylogenies was calibrated using a probabilistic prior taken from well-attested evidence that modern Ainu expanded into Sakhalin around 15th century [38] , [39] : a normally-distributed prior with a mean of 500 BP with its 95% of the distribution incorporating 200 years of uncertainty. For all analyses, we applied a stochastic Dollo model with a correction for ascertainment bias [40] and a Bayesian skyline tree prior [41] . We chose the best model by comparing Bayes Factors (BF) [42] .

Based on BF tests among diffusion models and evolutionary clock models, we chose the relaxed clock with gamma-distributed diffusion as the best model ( Table S1 ). Figure 2 shows the summary of time-dated maximum clade credibility trees for 19 Ainu language varieties. Assuming that the patterns of linguistic diversity is shaped by the demographic dynamics of speakers, we predicted that if the recent evidence supporting the Okhotsk expansion scenario were correct, then the estimated root age should overlap with 900–1600 BP. The estimated root age of the Ainu language across post-burn-in trees has a median of 1288 BP [mean: 1323 BP; 95% Highest Posterior Density (HPD): 820–1862 BP], in strong agreement with the prediction. We also predicted that if the hypothesized scenario were correct, then the current distribution of 19 Ainu language varieties should be the end result of diffusion from northern Hokkaido; otherwise, we would observe northward expansion from southern Hokkaido, conforming to the conventional dual-structure model. Figure 3 (also in Animation S1) shows that the estimated diffusion pattern in natural time scale [43] is in clear agreement with the prediction, with the estimated homeland being in northern Hokkaido. Both the diffusion pattern and root time were consistent across all models we excluded based on BF tests.

Colored branches represent two major subgroups (Green-Hokkaido; Yellow-Sakhalin). All node heights are scaled to match the posterior median node heights with bars indicating 95% HPD intervals of the estimated ages. The value on each branch is the posterior probability, showing the percentage support for the following node.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.g002

Color gradient of the polygons (80% HPD) indicates relevant age of the diffusion [Blue-older (1288 BP); Red-more recent (50 BP)]. White lines represent the phylogeny projected onto the surface. Image sources: © 2012 Google Earth; © 2012 Cnes/Spot Image; © 2012 TerraMetrics.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.g003

In order to examine the robustness of our phylogeographic inferences, we carried out two additional tests. Firstly, we tested the strength of support for northern Hokkaido origin (i.e., the Okhotsk expansion scenario) over southern Hokkaido origin (i.e., the dual-structure model) by directly calculating BF: we divided Hokkaido into two broad regions of north and south at the centroid of Hokkaido, and estimated BF by comparing the posterior to prior odds ratio of observing potential homeland in either one of the two regions. In agreement with our results, we obtained substantial support (BF = 7.5) for northern Hokkaido being the homeland of the Ainu. Secondly, we investigated whether or not our results are statistical artifacts of the diffusion model falling into the center of language mass regardless of the data: we randomly reassigned the locations of 19 Ainu varieties to the data for fifty times, and then obtained 90% HPDs for all possible root locations ( Figure S2 ). From this exercise, we observed that the absence of true signal could cause the estimated homeland to be as south as mainland Japan or as north as Sakhalin. This observation clearly demonstrates that our results are valid estimations based on true phylogeographical signal. Conversely, this also suggests that if the data contained signal indicating northward diffusion, or any other direction, our methods would have reconstructed it accordingly.

We acknowledge, however, that a well-established subgroup of the Ainu language, namely the Kuril, is absent from our data. This is because the Kuril had become extinct by the time the data were collected, and the Kuril lexicons seem to be available only through sketchy records scattered around the literature. For this reason, we currently have little information about the Kuril. If the point in time that the Kuril diverged from other varieties turns out to be much deeper, then the resulting divergence time and diffusion pattern may differ significantly from the current results. The search for a more complete set of data is, therefore, a direction that should be prioritized for further evaluation of our conclusion.

In this paper, we reconstructed spatiotemporal evolution of 19 Ainu language varieties, and the results are in strong agreement with the hypothesis that a recent population expansion of the Okhotsk people played a critical role in shaping the Ainu people and their culture. Together with the recent archaeological, biological and cultural evidence, our phylogeographic reconstruction of the Ainu language strongly suggests that the conventional dual-structure model must be refined to explain these new bodies of evidence. The case of the Ainu language origin we report here also contributes additional detail to the global pattern of language evolution, and our language phylogeny might also provide a basis for making further inferences about the cultural dynamics of the Ainu speakers [44] , [45] .

We recognize that there are also some evidence that the Jomon people, one of the two ancestral populations of the Ainu, may have descended from Northeast Asia rather than Southeast [46] , [47] , thereby questioning the validity of dual-structure model on a greater time scale. Unfortunately, the scope of our results presented here have little bearing on the larger question of the Jomon prehistory because the linguistic traces of this process may have been wiped out by the recent rise of the Ainu as our results indicate. Regardless of what further research reveals about the Jomon ancestry, however, we argue that the evidence for the Okhotsk expansion scenario should remain valid, and therefore any future models of deeper historical process for the Japanese islands must properly account for the recent northern Hokkaido origin of the Ainu. With this respect, we suggest that the most effective way of shedding light on the deeper history of the Jomon, or historical processes of any other regions, is to synthesize different lines of evidence from archaeology, biology and culture, and triangulate them to obtain a rigorous analytic framework [48] rather than relying on a single line of evidence.

If our inferences are correct, then the recent Okhotsk expansion scenario for the Ainu origin leads us to a new question: what historical factors drove the Okhotsk people to migrate from the Amur river basin to Hokkaido and give rise to the Ainu? It is now clear that early farming populations went through similar processes due to agricultural intensification and cultural innovation [4] but the Okhotsk people were hunter-gatherers, not farmers. While not resolving this question directly, Hudson [49] provides a comprehensive model of the Okhotsk socio-environmental conditions that allows us to sketch out a possible scenario: (i) the diet of the Okhotsk people relied heavily on marine mammal products and (ii) the time in which the Okhotsk expansion occurred seems to be characterized by dramatic climate changes, beginning with a cold sea-ice stage between 1300–1800 BP followed by a warmer open-ocean stage. Based on these observations, we speculate that the Okhotsk expansion may have been opportunistic in nature: the sea-ice condition in the early stage probably resulted in increased area for exploiting marine mammals as well as convenient routes for exploring new territory, thereby leading to the migration into Hokkaido. The drastic climate change in the later stage, however, may have deteriorated the hunting conditions for the Okhotsk with rapid break up of sea-ice, which may also have necessitated increased reliance on other types of food source, and hence causing a greater degree of niche overlap with the preexisting Jomon population. The end result was probably the admixture of the two populations, followed by the rise of a new ethnolinguistic group, namely the Ainu.

If we accept a view that transmission of language may be gender-specific [50] – [52] , then we are able to formulate at least two hypotheses for the specific processes of the Ainu language origin. Because Y-chromosome haplogroup D is thought to represent Jomon male ancestry, the predominance of that particular haplogroup in the Ainu (75–87.5%) implies that the majority of Ainu male ancestry is from the Jomon [53] , [54] , whereas a heavy mixture of mtDNA haplogroups indicates that a significant proportion of the Ainu female ancestry is from the Okhotsk (excluding 35.3% of mtDNA haplogroups that the Ainu share with other neighboring populations, 39.4% of the remaining female heritage is shared exclusively with the Okhotsk and the rest is a mixture of both Jomon and Okhotsk [18] , [47] , [54] ). If we thus assume male-specific language transmission for the Ainu, the first hypothesis for the processes behind the Ainu language origin could be that proto-Ainu arose from a large number of Jomon males who intermarried with Okhotsk females in northern Hokkaido, and subsequently spread to the rest of region. Similarly, if we assume that the transmission of Ainu language corresponds with female ancestry, the second hypothesis could be that proto-Ainu was spoken by the incoming Okhotsk females who merged with the preexisting Jomon males. Based on these observations, we propose that one potential way of understanding how language change occurred for the Ainu is to estimate which gender was more influential when early Ainu people established family membership. This may be carried out indirectly by revealing the signature of historical post-marital residence pattern via estimating the degrees of genetic variation in their Y-chromosome and mtDNA [55] as well as reconstructing ancestral post-marital residence rules from regional cultural variation [56] . Investigating which model of language change [57] is relevant to the Ainu is a direction that deserves more attention, and acquiring an accurate description of how language change occurred for the Ainu would allow us to make further inferences about the deeper history of the human lineage that once thrived in northern Japan.

Languages rise and fall, and so do the communities who speak them. Although significant progress has been made in recent years, we are still far from thoroughly understanding why languages are so deeply related to the fates of their speakers or how the process unfolds through evolutionary history. These are perhaps some of the most challenging questions in human sciences, and a complete understanding of this complex phenomenon might thus be reached only with further methodological innovations as well as more language data from around the world. But as we demonstrate in this paper, a combination of spatiotemporal reconstruction of language evolution and synthesis of several different historical evidences is probably one of the most promising methodologies that can further illuminate the process and consequence of this fascinating phenomenon.

Supporting Information

Full list of the Ainu language varieties. Colored circles represent subgrouping (Green-Hokkaido; Yellow-Sakhalin).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.s001

Ninety percent highest probability density obtained from fifty random reassignments of location coordinates to the tips of phylogeny. This demonstrates that our results are not statistical artifacts of the diffusion model returning to the center of language mass. For all analyses, we applied an arbitrary root calibration consisting of a normal distribution with the mean of 1500 BP and the standard deviation of 400 years.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.s002

Log-marginal likelihoods estimated from all models fitted to data. The model with a relaxed clock and gamma-distributed random walk model shows the best fit with the highest log-marginal likelihood.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.s003

Animation S1.

Animated origin and diffusion of the Ainu language varieties in natural time scale. Color gradient of the polygons (80% HPD) indicates relevant age of the diffusion [Blue-older (1288 BP); Red-more recent (50 BP)]. White lines represent the phylogeny projected onto the surface. Image sources: © 2012 Google Earth; © 2012 Cnes/Spot Image; © 2012 TerraMetrics.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.s004

Analysis S1.

NEXUS and BEAST input files for full details of the analysis.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062243.s005

Acknowledgments

We thank Russell Gray, Simon Greenhill and Quentin Atkinson for their insightful comments and help with technical issues. We also thank two thoughtful reviewers for their constructive comments.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: SL TH. Analyzed the data: SL. Wrote the paper: SL TH.

- 1. Darwin C (1871) The descent of man. London: Murray.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 16. Vovin A (1993) A reconstruction of proto-Ainu. Leiden: Brill.

- 18. Sato T, Amano T, Ono H, Ishida H, Kodera H, et al.. (2009) Mitochondrial DNA haplogrouping of the Okhotsk people based on analysis of ancient DNA: an intermediate of gene flow from the continental Sakhalin people to the Ainu. Anthro Sci: 905260063. doi:10.1537/ase081202.

- 23. Embleton SM (1986) Statistics in historical linguistics. Bochum, Germany: Brockmeyer.

- 25. Crowley T, Bowern C (2009) An introduction to historical linguistics. Oxford, London: Oxford University Press.

- 28. Swadesh M (2006) The origin and diversification of language. Sherzer JF, editor. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- 32. Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A (2012) Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol: 1–4. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss075.

- 33. Pybus OG, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Bernardin FJ, Rambaut A, et al.. (2012) Unifying the spatial epidemiology and molecular evolution of emerging epidemics. Proc Natl Acad Sci: 1–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206598109.

- 42. Baele G, Lemey P, Bedford T, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, et al.. (2012) Improving the accuracy of demographic and molecular clock model comparison while accommodating phylogenetic uncertainty. Mol Biol Evol. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss084.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Times Insider

Mapping New York’s Endangered Languages

A new interactive article for The New York Times Magazine captured one group’s efforts to document languages in peril.

By John Otis

Times Insider explains who we are and what we do and delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how our journalism comes together.

A few years ago, Alex Carp, a research editor at The New York Times Magazine, learned about the work of the nonprofit Endangered Language Alliance . Founded in Manhattan in 2010 and co-directed by the linguists Ross Perlin and Daniel Kaufman, E.L.A. documents languages spoken in New York City, hundreds of which are endangered.

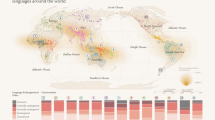

Through their research, Mr. Perlin and Mr. Kaufman learned that more than 700 languages are spoken throughout the city. Some of the languages have no formal writing system; they survive only through oral traditions.

Mr. Carp, who writes and fact-checks articles for The Times Magazine, wanted to share E.L.A.’s work with The Times’s audience and did so in a project published online last week . The interactive article features a series of detailed digital maps, designed by Francesco Muzzi, that pinpoint where in the city many endangered languages are spoken.

The article also includes videos of people who speak some of these languages, captured by Ruven Afanador, as well as audio recordings provided by E.L.A. Times readers can hear languages such as Wakhi, which is spoken in the Pamir mountains in Central Asia, and Seke, a language from Nepal that has only about 700 global speakers.

In a recent conversation, Mr. Carp shared how he collected the data and why he hoped the project would serve generations to come. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Why did you find E.L.A.’s research so compelling?

E.L.A.’s work provides a portrait of New York City and its communities that many Times readers have no idea about. Many of the languages are not acknowledged at all by schools, large businesses or the census. When the city began to do so, by offering videos and webinars in some of these languages for programs like pandemic outreach and IDNYC, which provides New York City’s identification cards, it was the first official recognition that many of these languages existed.

Can you elaborate on the data-collection process?

We used E.L.A.’s “Languages of New York City” map, which documents all the languages they know are spoken in the city. Then we cross-referenced those languages with three independent language databases that track the threat level of languages around the world.

Those databases each use slightly different criteria, such as the number of global speakers and transmission of the language between generations; they helped establish a base line for the number of languages in the city or in a given borough that would broadly be considered to be in danger. From there, The Times’s design team built maps of boroughs and specific neighborhoods that were especially dense with endangered languages, reflecting where these languages are spoken across the city.

E.L.A. very consciously did not make a demarcation for every language about whether it was endangered or not. It can be a contested category; some languages only get documented by linguists once, and maybe that was done 20 or 30 years ago. So a database might have a language listed as stable or safe when there have been huge changes in the region since the last time rigorous, on-the-ground work has been done.

Why was it so important to include audio recordings and video portraits in the online article?

A lot of these languages are oral only. Reading the languages in text is different from hearing people speak them. The E.L.A. is documenting and studying these languages because many of them are unlikely to exist in a generation or two. In a small way, my hope for this article is that it will represent a sort of mini-language documentation project.

How did you select which languages to feature in audio clips?

We worked with E.L.A. to select people who spoke languages from different language families — groups of historically related languages that often share similar traits — who lived in different parts of the city. We tried to get as close as we could to a representative cross-section of E.L.A.’s work, and of the endangered languages spoken in the city.

What do you hope readers take away from this article?

New Yorkers who speak these languages or know people who do are often overlooked and are fighting for recognition. For those who speak them or have people in their lives who do, I hope that there’s some satisfaction in seeing themselves reflected in The New York Times.

For people who don’t speak these languages or who may have never encountered those who speak them, I hope the article helps them see New York City, and our country, in a slightly different, richer way than they might have otherwise.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Chakma language: Survival from being extinct in Bangladesh

Related Papers

Nayma Afreen

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation

Drishtipat Writers' Collective

Naeem Mohaiemen

Kapaeeng Foundation

Pallab Chakma

Bablu Chakma

Anurug Chakma , Bablu Chakma , Manik Soren , Binota Moy Dhamai , M. Promila

Journal of Asian Linguistic Anthropology

Razaul K A R I M Faquire

This study explores the effects of the language contact situation which has been recently created in the Chittagong Hill-Tracts (CHT) by means of immigration of Bangla speaking people from other parts of Bangladesh. The CHT, which borders India and Myanmar, has been the abode of approximately million people, about 50% of whom are minority speech communities, including the speakers of Tibeto-Burman (TB) languages such as Marma, Tripura (Kokborok), Kyang and Khumi (Faquire, 2010). The remaining 50% are the speakers of Bangla, the national and official language of Bangladesh. The new distribution of various speech communities comprising an overwhelming majority of Bangla speakers has been created by the Government of Bangladesh through a migration policy during the 1980s.

Mohammed kabir

Munin logo. "Let's go back to go forward" : history and practice of schooling in the indigenous communities in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. DSpace/Manakin Repository. ...

RELATED PAPERS

Niaz Makhdum

Khondoker Shakhawat Ali

in: Willem van Schendel and Erik-Jan Zürcher (eds.), Identity Politics in Central Asia and the Muslim World: Nationalism, Ethnicity and Labour in the Twentieth Century (London and New York: I.B.Tauris, 2001), 107-147.

Willem van Schendel

Jumland Printing Press (Pvt) Limited

Chakma Ratan

Bablu Chakma , Manik Soren

Zabarang Kalyan Samity

Mathura Tripura

S. R. Khan Orthy

jUMMALAND INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL

Binota Moy Dhamai , Bablu Chakma , Sayon Dewan , anmoy chakma

Sawani dilini

Dr.Ratan B.Chakma PhD

Zobaida Nasreen

An Analytical Study of History of Buddhism and Political Activism in Jummaland, Bangladesh by Rev.Dr.Rashtrapal Mahathero (Ratan Bikas Chakma)

GRFDT Research Monograph Series

Diaspora Transnationalism

Manik Soren , Bablu Chakma

Shaila Sultana

UN WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME (WFP) FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON THE CHITTAGONG HILL TRACTS

uchacha A Chak

H M Ashraf Ali

Hana S Ahmed

Lars T Soeftestad

Master Thesis

Zahid Hassan

Eva Gerharz

Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development

Md Mijanur Rahman,SAD, personnel.

Dr. Abu Shahid Abdullah

PHD FINAL THESIS

Hossain, D. M. (2013), Socio-economic Situation of the Indigenous People in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh, Middle East Journal of Business, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 22-30. (Australia)

DEWAN MAHBOOB HOSSAIN

876543212019

Dr. Matthew Wilkinson

Created only for academic thesis purpose

Shawkat Hasan

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Language Extinction in East Africa Research Paper

Introduction, language extinction.

Endangered Languages are languages that are growing obsolete because their native speakers are being lost. Endangered Languages are defined as those that won’t be spoken by coming generations in the next 100 years; while languages free from extinction are those that would be spoken by children in the coming 100 years. Most of the languages in the world fall under the endangered languages category with UNESCO approximating the percentage of endangered languages to be around 60%-80% (Global Language Hotspots, 2010). There are however about six thousand dialects spoken globally today.

Language extinction is therefore a result of languages being endangered. Extinct languages are dead languages. Extinct languages actually have no native speakers; in the sense that nobody uses it as his/ her main language (Salzman, 1998). Normally, this is a process that’s facilitated by the replacement of the original language with another (Hale and Ladefoged, 2006). For instance, Native American Languages were also substituted.In Egypt, the Arabian influence replaced the Coptic language and therefore making it extinct (Crawford, 1992).

This study will utilize Eastern Africa as a language hotspot. It will identify the endangered languages in the region and explain the factors that basically lead to the observation of this phenomenon. Eastern Africa is basically comprised of nations namely; Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan and Tanzania. This region is at the Horn of Africa but under the Sub Saharan region of Africa. It is majorly a Kiswahili speaking region with Tanzania embracing it in various social sectors such as education and government programs (National Geographic, 2010). Kenya was majorly a British colony, so English is majorly used in most of its social aspects including corporate affairs, education and other forums. Kiswahili is however it’s national language.

Other languages however characterize the region but are on a smaller scale. The number of languages spoken in this region is 215 with 17 genetic units (Global Language Hotspots, 2010). The threat level of languages in this region is not very high; it has a genetic index of 080 and a research index that’s yet to be determined (Global Language Hotspots, 2010).

The region being in Sub Saharan Africa, it’s majorly under agriculture and nomadic activities. Nomadic activities have led to assimilation and intermixing of languages at various social levels including trade (during the pre colonial era and afterwards). Omotik stands out to be an endangered language in Kenya. It has become moribund with fewer than 50 native speakers; most of them above the age of 40. Most of them had been assimilated into the Maasai language group who are majorly pastoralists in Kenya. The Omotik used to be hunters and gatherers and have been observed to be living among the Maasai population. They are noted to adopt the Maasai lifestyle of pastoralist and even speak Maasai as a language now. The descendants of Omotik grew using the Maasai language. The adoption of this language worked negatively on chances of living on for the language (Brenzinger, 1992).

Other endangered languages in the Eastern Africa region include the Birale who are a classical language group of Afro-asiatic living in Ethiopia. Currently there are only about 20 native speakers. Boon is also under the category of endangered languages with only 60 speakers of Cushitic origin. The Boon speaking group majorly inhabits Somalia. There exists another small minority group inhabiting Tanzania known as Gweno . There are less than 100 native speakers currently in existence. Karo is also an endangered Language with 200 native speakers. The language is spoken among the Omotic group residing in Ethiopia. Molo is an endangered language in Sudan among the East Jebel group residing in Sudan. There are only 100 native speakers left (Global Language Hotspots, 2010). Most the native speakers of these endangered languages are basically farmers, hunters and gatherers or pastoralists. Their religion orientation varies from place to place with groups in Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan majorly being Muslim whiles those from Kenya and Tanzania being Christian.

Language extinction is a process whereby the language orientation of a community is affected. As a result, the level of linguistic competency in the language is decreased. Native speakers then become extinct as other languages take root. However, language death should be differentiated from language loss, as the latter depicts a scenario where there is loss of proficiency of language at an individual level only (Denison, 1977).

A comparison can be drawn between the extinction of languages and the extinction of plants and animals. The obvious reasons that could be attributed to this phenomenon are the effects of predators and competitors. The changing environment can also be an attribution to the same. The threat of languages is increasingly becoming prominent with the process going on in discretion. However, we seem to be living in a period of massive extinctions including the cultural heritage of various language speaking groups (Crawford, 1992).

However, the rate of language extinction cannot be correctly verified like the rate of plant and animal extinction through use of fossil records. Modern culture and technological revolutions have been noted to contribute immensely to language extinction. This has greatly encroached on the way of life for many native speakers. It has even sought to change the environment in which they live in. Consumerism and individualism has been noted to be great facilitators to language extinction. This has occurred on a forum of Western perpetration of cultures across various cultural blocks. A resultant destruction of land and livelihoods has been noted with a direct influence towards assimilation into dominant cultures. Unfortunately, this dominant pressure on assimilation is directed towards indigenous groups. The world’s bio diversity has greatly been affected as a result. Cultural and linguistic identities have also suffered the same impact (Denison, 1977). The case of the Omotik is a good example because they lost their cultural identity from being hunters and gatherers to pick up Maasai’s culture of pastoralism.

Language resuscitation is however possible as can be seen with the case of Hebrew language which had been dead for almost 2000 years but re-introduced in Israel. This effort to revitalize extinct language involves a lot of social and educational programs. The effort to revitalize languages is however ill-advised, if there is little hope for reviving extinct languages. Tremendous capital requirements are however needed to revitalize languages that are in the process of extinction or already extinct. This is because of the programs that have to be undertaken to initiate this course (Brenzinger, 1992).

Languages in Eastern Africa under the threat of extinction aren’t being countered with much revitalization efforts though. This is because the small minority languages are ignored by the government and other social groups. Most of the endangered languages are pre colonial and are overshadowed by other dominant but minority languages spoken in their countries of origin. For example the Omotik is being overshadowed by the Maasai language which is a small but dominant language in a larger context of a Swahili speaking nation (Kenya).

Governments have therefore neglected small languages in a wider quest to embrace national languages that would facilitate integration efforts. This is so, because the region (Eastern Africa) has been characterized by incidences of tribalism and civil unrests traced to a lack of integration among language speaking groups. Not much effort is being made to save the dying languages because of this reason.

For instance, recent community violence in Kenya after 2007 general election was greatly attributed to tribal differences between major language speaking groups. The government then undertook a massive social exercise to diffuse the influences of specific language speaking groups for a major pursuit of nationalism. Civil societies and the government have since then been involved in national exercises to promote the use of Kiswahili as a national language at the expense of smaller languages. However, specific language groups have undertaken individual initiatives to preserve their identities through showcasing authentic group activities like bull fighting and cultural nights that aim at preserving language identities.

Language extinction is critical in the sense that it preserves selective community heritages; though it might be destructive in the sense that it acts contrary to efforts of unifying communities. The context to which language extinction is studied should be analyzed relatively, with regard to the cause for preventing language extinction. The society which efforts for revitalizing languages are undertaken should also be put into consideration (McWorther, 1995). A nation like Israel would seek to gain from preserving its native languages like Hebrew but in the context of Eastern Africa, the effects would be different. This is because Israel isn’t susceptible to civil violence as a result of language identities.

Eastern Africa has experienced some of the worst cases of civil unrests facilitated by language group identities. The Rwanda genocide that took the lives of millions of people across the globe was majorly perpetrated by individual language groups more specifically the Hutsi and Tutsi tribes. These language groups killed each other in a blood bath across the nation which was among the worst forms of humanitarian disasters in the world, to date. The situation would however be different if Rwanda had a unifying language that most citizens would identify with. It would also be difficult for political leaders to use the avenue of language orientation and cultural identity to mobilize groups against each other.

I was aware of language extinction prior to this discussion because of the levels of Western dominance across the globe coupled with various cultural changes across decades. However, this study majorly depends on individual societies and contexts. Western dominance has greatly impacted on indigenous language speaking groups but has led to faster integration of economies, speaking the same language. More integration has also been observed in other social setups like marriage and even tourism facilitation. People would be more inclined to tour places where they can communicate effectively with the people around.

However, dominance of other cultures has been observed to be detrimental to societies at large; for example, the dominance of Western cultures over other conservative cultures. The culture is purported to increase immorality among other forms of social decadence that have led to a loss of core societal values. There have been cultures and individual groups that have been observed to have no issues with the influence of other cultures while some have been observed to be against external cultural influence. The situation is therefore varied.

Language preservation is therefore more detrimental than otherwise thought. There would be more to be gained if languages were to fade away and a more dominant culture used to cover every group. This would eliminate small segregational effects being experienced in the society today. Other sectors of the society have also been noted to develop as a result of the society integrating on a language front. Caution should however be made to preserve positive community identities like sports, specific economic activities and religious orientation but this shouldn’t be left to affect integration between language speaking groups for the betterment of the society.

- Brenzinger, M. (1992). Language Death: Factual and Theoretical Explorations with Special Reference to East Africa. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Crawford, J. (1992). Language Loyalties: A Source Book on the Official English Controversy . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Denison, N. (1977). Language death or language suicide? International Journal of the Sociology of Language , 12, 13-22.

- Global Language Hotspots. (2010). Eastern Africa .

- Hale, K., & Ladefoged, P. (2006). Should Anthropologists and Linguists be concerned about Endangered Languages? New York: Routledge.

- McWorther, J. (1995). Most of the Worlds Languages Went Extinct . New York: Princeton Press.

- National Geographic. (2010). Enduring Voices Project .

- Salzman, Z. (1998). Endangered Languages and Language Death : Language Culture and Society. London: Oxford Publishers.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, May 16). Language Extinction in East Africa. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-extinction/

"Language Extinction in East Africa." IvyPanda , 16 May 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/language-extinction/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Language Extinction in East Africa'. 16 May.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Language Extinction in East Africa." May 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-extinction/.

1. IvyPanda . "Language Extinction in East Africa." May 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-extinction/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Language Extinction in East Africa." May 16, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-extinction/.

- Impact of Globalization on the Maasai Peoples` Culture

- The Maasai and Bushmen of Africa

- The Maasai: One of the Indigenous Tribes in the World

- The African American and Maasai Culture as a Co-Culture

- Significance of the Rite of Passage: Maasai Lion Hunt

- The Unfamiliar Culture of the Maasai People

- Maasai Mara Trip and Preparations

- The History of Tanzania

- Dodo Bird and Why It Went Extinct

- Political Risk and Legal Restrictions in Tanzania

- Position of Catalan in Catalonia and of Irish in Ireland

- New Zealand English: Environment as a Vocabulary Area

- Sociolinguistic Variation Study

- "Viva Bilingualism" by James Fallows

- English Only Laws Review

English dominates scientific research – here’s how we can fix it, and why it matters

Científica titular del Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales (CCHS - CSIC), Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales (CCHS - CSIC)

Disclosure statement

Elea Giménez Toledo does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation ES.

View all partners

It is often remarked that Spanish should be more widely spoken or understood in the scientific community given its number of speakers around the world, a figure the Instituto Cervantes places at almost 600 million .

However, millions of speakers do not necessarily grant a language strength in academia. This has to be cultivated on a scientific, political and cultural level, with sustained efforts from many institutions and specialists.

The scientific community should communicate in as many languages as possible

By some estimates, as much as 98% of the world’s scientific research is published in English , while only around 18% of the world’s population speaks it. This makes it essential to publish in other languages if we are to bring scientific research to society at large.

The value of multilingualism in science has been highlighted by numerous high profile organisations, with public declarations and statements on the matter from the European Charter for Researchers , the Helsinki Initiative on Multiligualism , the Unesco Recommendation on Open Science , the OPERAS Multiligualism White Paper , the Latin American Forum on Research Assessment , the COARA Agreement on Reforming Research Assessment , and the Declaration of the 5th Meeting of Minsters and Scientific Authorities of Ibero-American Countries . These organisations all agree on one thing: all languages have value in scientific communication.

As the last of these declarations points out, locally, regionally and nationally relevant research is constantly being published in languages other than English. This research has an economic, social and cultural impact on its surrounding environment, as when scientific knowledge is disseminated it filters through to non-academic professionals, thus creating a broader culture of knowledge sharing.

Greater diversity also enables fluid dialogue among academics who share the same language, or who speak and understand multiple languages. In Ibero-America, for example, Spanish and Portuguese can often be mutually understood by non-native speakers, allowing them to share the scientific stage. The same happens in Spain with the majority of its co-official languages .

Read more: Non-native English speaking scientists work much harder just to keep up, global research reveals

No hierarchies, no categories

Too often, scientific research in any language other than English is automatically seen as second tier, with little consideration for the quality of the work itself.

This harmful prejudice ignores the work of those involved, especially in the humanities and social sciences. It also profoundly undermines the global academic community’s ability to share knowledge with society.

By defending and preserving multilingualism, the scientific community brings research closer to those who need it. Failing to pursue this aim means that academia cannot develop or expand its audience. We have to work carefully, systematically and consistently in every language available to us.

Read more: Prestigious journals make it hard for scientists who don't speak English to get published. And we all lose out

The logistics of strengthening linguistic diversity in science

Making a language stronger in academia is a complex process. It does not happen spontaneously, and requires careful coordination and planning. Efforts have to come from public and private institutions, the media, and other cultural outlets, as well as from politicians, science diplomacy , and researchers themselves.

Many of these elements have to work in harmony, as demonstrated by the Spanish National Research Council’s work in ES CIENCIA , a project which seeks to unite scientific and and political efforts.

Academic publishing and AI models: a new challenge

The global academic environment is changing as a result the digital transition and new models of open access. Research into publishers of scientific content in other languages will be essential to understanding this shift. One thing is clear though: making scientific content produced in a particular language visible and searchable online is crucial to ensuring its strength.

In the case of academic books, the transition to open access has barely begun , especially in the commercial publishing sector, which releases around 80% of scientific books in Spain. As with online publishing, a clear understanding will make it possible to design policies and models that account for the different ways of disseminating scientific research, including those that communicate locally and in other languages. Greater linguistic diversity in book publishing can also allow us to properly recognise the work done by publishers in sharing research among non-English speakers.

Read more: Removing author fees can help open access journals make research available to everyone

Making publications, datasets, and other non-linguistic research results easy to find is another vital element, which requires both scientific and technical support. The same applies to expanding the corpus of scientific literature in Spanish and other languages, especially since this feeds into generative artificial intelligence models.

If linguistically diverse scientific content is not incorporated into AI systems, they will spread information that is incomplete, biased or misleading: a recent Spanish government report on the state of Spanish and co-official languages points out that 90% of the text currently fed into AI is written in English.

Deep study of terminology is essential

Research into terminology is of the utmost importance in preventing the use of improvised, imprecise language or unintelligible jargon. It can also bring huge benefits for the quality of both human and machine translations, specialised language teaching, and the indexing and organisation of large volumes of documents.

Terminology work in Spanish is being carried out today thanks to the processing of large language corpuses by AI and researchers in the TeresIA project, a joint effort coordinated by the Spanish National Research Council. However, 15 years of ups and downs were needed to to get such a project off the ground in Spanish.

The Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia, on the other hand, have worked intensively and systematically on their respective languages. They have not only tackled terminology as a public language policy issue, but have also been committed to established terminology projects for a long time.

Multiligualism is a global issue

This need for broader diversity also applies to Ibero-America as a whole, where efforts are being coordinated to promote Spanish and Portuguese in academia, notably by the Ibero-American General Secretariat and the Mexican National Council of Humanities, Sciences and Technologies .

While this is sorely needed, we cannot promote the region’s two most widely spoken languages and also ignore its diversity of indigenous and co-official languages. These are also involved in the production of knowledge, and are a vehicle for the transfer of scientific information, as demonstrated by efforts in Spain.

Each country has its own unique role to play in promoting greater linguistic diversity in scientific communication. If this can be achieved, the strength of Iberian languages – and all languages, for that matter – in academia will not be at the mercy of well intentioned but sporadic efforts. It will, instead, be the result of the scientific community’s commitment to a culture of knowledge sharing.

This article was originally published in Spanish

- Scientific publishing

- Multilingualism

- The Conversation Europe

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition

Title: mm1: methods, analysis & insights from multimodal llm pre-training.

Abstract: In this work, we discuss building performant Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs). In particular, we study the importance of various architecture components and data choices. Through careful and comprehensive ablations of the image encoder, the vision language connector, and various pre-training data choices, we identified several crucial design lessons. For example, we demonstrate that for large-scale multimodal pre-training using a careful mix of image-caption, interleaved image-text, and text-only data is crucial for achieving state-of-the-art (SOTA) few-shot results across multiple benchmarks, compared to other published pre-training results. Further, we show that the image encoder together with image resolution and the image token count has substantial impact, while the vision-language connector design is of comparatively negligible importance. By scaling up the presented recipe, we build MM1, a family of multimodal models up to 30B parameters, including both dense models and mixture-of-experts (MoE) variants, that are SOTA in pre-training metrics and achieve competitive performance after supervised fine-tuning on a range of established multimodal benchmarks. Thanks to large-scale pre-training, MM1 enjoys appealing properties such as enhanced in-context learning, and multi-image reasoning, enabling few-shot chain-of-thought prompting.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- Download PDF

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS