Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Key facts about the abortion debate in america.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade – the decision that had guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion for nearly 50 years – has shifted the legal battle over abortion to the states, with some prohibiting the procedure and others moving to safeguard it.

As the nation’s post-Roe chapter begins, here are key facts about Americans’ views on abortion, based on two Pew Research Center polls: one conducted from June 25-July 4 , just after this year’s high court ruling, and one conducted in March , before an earlier leaked draft of the opinion became public.

This analysis primarily draws from two Pew Research Center surveys, one surveying 10,441 U.S. adults conducted March 7-13, 2022, and another surveying 6,174 U.S. adults conducted June 27-July 4, 2022. Here are the questions used for the March survey , along with responses, and the questions used for the survey from June and July , along with responses.

Everyone who took part in these surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

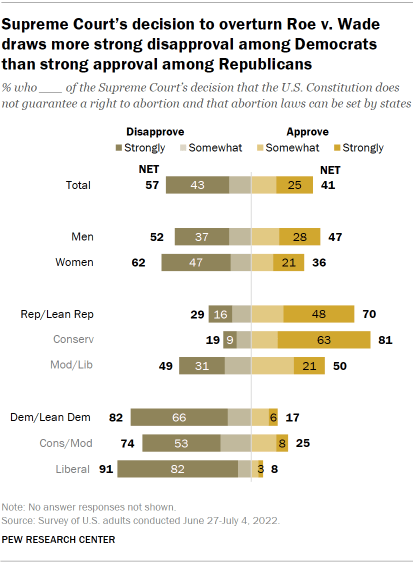

A majority of the U.S. public disapproves of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe. About six-in-ten adults (57%) disapprove of the court’s decision that the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion and that abortion laws can be set by states, including 43% who strongly disapprove, according to the summer survey. About four-in-ten (41%) approve, including 25% who strongly approve.

About eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (82%) disapprove of the court’s decision, including nearly two-thirds (66%) who strongly disapprove. Most Republicans and GOP leaners (70%) approve , including 48% who strongly approve.

Most women (62%) disapprove of the decision to end the federal right to an abortion. More than twice as many women strongly disapprove of the court’s decision (47%) as strongly approve of it (21%). Opinion among men is more divided: 52% disapprove (37% strongly), while 47% approve (28% strongly).

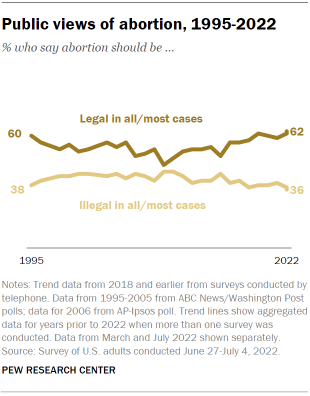

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to the summer survey – little changed since the March survey conducted just before the ruling. That includes 29% of Americans who say it should be legal in all cases and 33% who say it should be legal in most cases. About a third of U.S. adults (36%) say abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases.

Generally, Americans’ views of whether abortion should be legal remained relatively unchanged in the past few years , though support fluctuated somewhat in previous decades.

Relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the legality of abortion – either supporting or opposing it at all times, regardless of circumstances. The March survey found that support or opposition to abortion varies substantially depending on such circumstances as when an abortion takes place during a pregnancy, whether the pregnancy is life-threatening or whether a baby would have severe health problems.

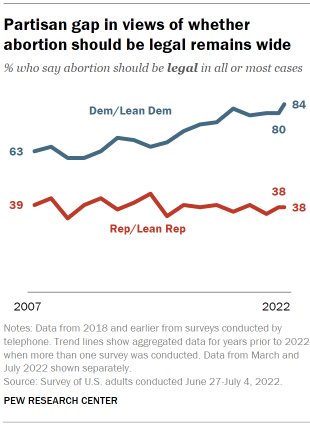

While Republicans’ and Democrats’ views on the legality of abortion have long differed, the 46 percentage point partisan gap today is considerably larger than it was in the recent past, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling. The wider gap has been largely driven by Democrats: Today, 84% of Democrats say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, up from 72% in 2016 and 63% in 2007. Republicans’ views have shown far less change over time: Currently, 38% of Republicans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, nearly identical to the 39% who said this in 2007.

However, the partisan divisions over whether abortion should generally be legal tell only part of the story. According to the March survey, sizable shares of Democrats favor restrictions on abortion under certain circumstances, while majorities of Republicans favor abortion being legal in some situations , such as in cases of rape or when the pregnancy is life-threatening.

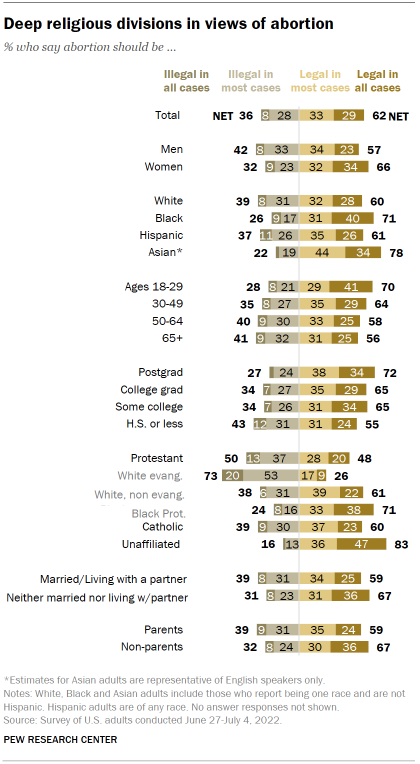

There are wide religious divides in views of whether abortion should be legal , the summer survey found. An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated adults (83%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as do six-in-ten Catholics. Protestants are divided in their views: 48% say it should be legal in all or most cases, while 50% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Majorities of Black Protestants (71%) and White non-evangelical Protestants (61%) take the position that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while about three-quarters of White evangelicals (73%) say it should be illegal in all (20%) or most cases (53%).

In the March survey, 72% of White evangelicals said that the statement “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” reflected their views extremely or very well . That’s much greater than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (32%), Black Protestants (38%) and Catholics (44%) who said the same. Overall, 38% of Americans said that statement matched their views extremely or very well.

Catholics, meanwhile, are divided along religious and political lines in their attitudes about abortion, according to the same survey. Catholics who attend Mass regularly are among the country’s strongest opponents of abortion being legal, and they are also more likely than those who attend less frequently to believe that life begins at conception and that a fetus has rights. Catholic Republicans, meanwhile, are far more conservative on a range of abortion questions than are Catholic Democrats.

Women (66%) are more likely than men (57%) to say abortion should be legal in most or all cases, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling.

More than half of U.S. adults – including 60% of women and 51% of men – said in March that women should have a greater say than men in setting abortion policy . Just 3% of U.S. adults said men should have more influence over abortion policy than women, with the remainder (39%) saying women and men should have equal say.

The March survey also found that by some measures, women report being closer to the abortion issue than men . For example, women were more likely than men to say they had given “a lot” of thought to issues around abortion prior to taking the survey (40% vs. 30%). They were also considerably more likely than men to say they personally knew someone (such as a close friend, family member or themselves) who had had an abortion (66% vs. 51%) – a gender gap that was evident across age groups, political parties and religious groups.

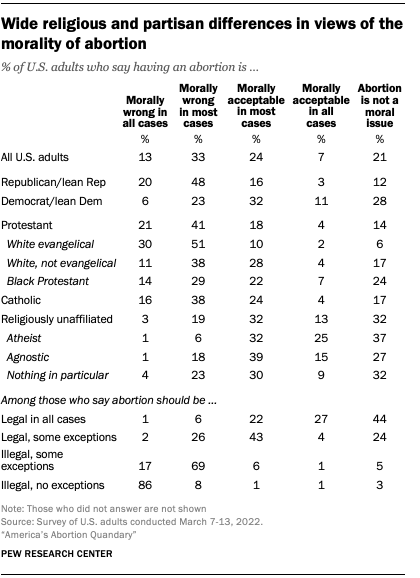

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms , the March survey found. Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say having an abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that having an abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable in most cases. An additional 21% do not consider having an abortion a moral issue.

Among Republicans, most (68%) say that having an abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Only about three-in-ten Democrats (29%) hold a similar view. Instead, about four-in-ten Democrats say having an abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say it is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say having an abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view having an abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see having an abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Public Opinion on Abortion

Majority in u.s. say abortion should be legal in some cases, illegal in others, three-in-ten or more democrats and republicans don’t agree with their party on abortion, partisanship a bigger factor than geography in views of abortion access locally, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Open access

- Published: 28 June 2021

Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol

- Foluso Ishola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8644-0570 1 ,

- U. Vivian Ukah 1 &

- Arijit Nandi 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 192 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

A country’s abortion law is a key component in determining the enabling environment for safe abortion. While restrictive abortion laws still prevail in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many countries have reformed their abortion laws, with the majority of them moving away from an absolute ban. However, the implications of these reforms on women’s access to and use of health services, as well as their health outcomes, is uncertain. First, there are methodological challenges to the evaluation of abortion laws, since these changes are not exogenous. Second, extant evaluations may be limited in terms of their generalizability, given variation in reforms across the abortion legality spectrum and differences in levels of implementation and enforcement cross-nationally. This systematic review aims to address this gap. Our aim is to systematically collect, evaluate, and synthesize empirical research evidence concerning the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs.

We will conduct a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on changes in abortion laws and women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will search Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases, as well as grey literature and reference lists of included studies for further relevant literature. As our goal is to draw inference on the impact of abortion law reforms, we will include quasi-experimental studies examining the impact of change in abortion laws on at least one of our outcomes of interest. We will assess the methodological quality of studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series checklist. Due to anticipated heterogeneity in policy changes, outcomes, and study designs, we will synthesize results through a narrative description.

This review will systematically appraise and synthesize the research evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will examine the effect of legislative reforms and investigate the conditions that might contribute to heterogeneous effects, including whether specific groups of women are differentially affected by abortion law reforms. We will discuss gaps and future directions for research. Findings from this review could provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services and scale up accessibility.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019126927

Peer Review reports

An estimated 25·1 million unsafe abortions occur each year, with 97% of these in developing countries [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Despite its frequency, unsafe abortion remains a major global public health challenge [ 4 , 5 ]. According to the World health Organization (WHO), nearly 8% of maternal deaths were attributed to unsafe abortion, with the majority of these occurring in developing countries [ 5 , 6 ]. Approximately 7 million women are admitted to hospitals every year due to complications from unsafe abortion such as hemorrhage, infections, septic shock, uterine and intestinal perforation, and peritonitis [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. These often result in long-term effects such as infertility and chronic reproductive tract infections. The annual cost of treating major complications from unsafe abortion is estimated at US$ 232 million each year in developing countries [ 10 , 11 ]. The negative consequences on children’s health, well-being, and development have also been documented. Unsafe abortion increases risk of poor birth outcomes, neonatal and infant mortality [ 12 , 13 ]. Additionally, women who lack access to safe and legal abortion are often forced to continue with unwanted pregnancies, and may not seek prenatal care [ 14 ], which might increase risks of child morbidity and mortality.

Access to safe abortion services is often limited due to a wide range of barriers. Collectively, these barriers contribute to the staggering number of deaths and disabilities seen annually as a result of unsafe abortion, which are disproportionately felt in developing countries [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. A recent systematic review on the barriers to abortion access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) implicated the following factors: restrictive abortion laws, lack of knowledge about abortion law or locations that provide abortion, high cost of services, judgmental provider attitudes, scarcity of facilities and medical equipment, poor training and shortage of staff, stigma on social and religious grounds, and lack of decision making power [ 17 ].

An important factor regulating access to abortion is abortion law [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Although abortion is a medical procedure, its legal status in many countries has been incorporated in penal codes which specify grounds in which abortion is permitted. These include prohibition in all circumstances, to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, and on request with no requirement for justification [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Although abortion laws in different countries are usually compared based on the grounds under which legal abortions are allowed, these comparisons rarely take into account components of the legal framework that may have strongly restrictive implications, such as regulation of facilities that are authorized to provide abortions, mandatory waiting periods, reporting requirements in cases of rape, limited choice in terms of the method of abortion, and requirements for third-party authorizations [ 19 , 21 , 22 ]. For example, the Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act permits abortion on socio-economic grounds. It is considered liberal, as it permits legal abortions for more indications than most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; however, abortions must only be provided in registered hospitals, and three medical doctors—one of whom must be a specialist—must provide signatures to allow the procedure to take place [ 22 ]. Given the critical shortage of doctors in Zambia [ 23 ], this is in fact a major restriction that is only captured by a thorough analysis of the conditions under which abortion services are provided.

Additionally, abortion laws may exist outside the penal codes in some countries, where they are supplemented by health legislation and regulations such as public health statutes, reproductive health acts, court decisions, medical ethic codes, practice guidelines, and general health acts [ 18 , 19 , 24 ]. The diversity of regulatory documents may lead to conflicting directives about the grounds under which abortion is lawful [ 19 ]. For example, in Kenya and Uganda, standards and guidelines on the reduction of morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion supported by the constitution was contradictory to the penal code, leaving room for an ambiguous interpretation of the legal environment [ 25 ].

Regulations restricting the range of abortion methods from which women can choose, including medication abortion in particular, may also affect abortion access [ 26 , 27 ]. A literature review contextualizing medication abortion in seven African countries reported that incidence of medication abortion is low despite being a safe, effective, and low-cost abortion method, likely due to legal restrictions on access to the medications [ 27 ].

Over the past two decades, many LMICs have reformed their abortion laws [ 3 , 28 ]. Most have expanded the grounds on which abortion may be performed legally, while very few have restricted access. Countries like Uruguay, South Africa, and Portugal have amended their laws to allow abortion on request in the first trimester of pregnancy [ 29 , 30 ]. Conversely, in Nicaragua, a law to ban all abortion without any exception was introduced in 2006 [ 31 ].

Progressive reforms are expected to lead to improvements in women’s access to safe abortion and health outcomes, including reductions in the death and disabilities that accompany unsafe abortion, and reductions in stigma over the longer term [ 17 , 29 , 32 ]. However, abortion law reforms may yield different outcomes even in countries that experience similar reforms, as the legislative processes that are associated with changing abortion laws take place in highly distinct political, economic, religious, and social contexts [ 28 , 33 ]. This variation may contribute to abortion law reforms having different effects with respect to the health services and outcomes that they are hypothesized to influence [ 17 , 29 ].

Extant empirical literature has examined changes in abortion-related morbidity and mortality, contraceptive usage, fertility, and other health-related outcomes following reforms to abortion laws [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. For example, a study in Mexico reported that a policy that decriminalized and subsidized early-term elective abortion led to substantial reductions in maternal morbidity and that this was particularly strong among vulnerable populations such as young and socioeconomically disadvantaged women [ 38 ].

To the best of our knowledge, however, the growing literature on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes has not been systematically reviewed. A study by Benson et al. evaluated evidence on the impact of abortion policy reforms on maternal death in three countries, Romania, South Africa, and Bangladesh, where reforms were immediately followed by strategies to implement abortion services, scale up accessibility, and establish complementary reproductive and maternal health services [ 39 ]. The three countries highlighted in this paper provided unique insights into implementation and practical application following law reforms, in spite of limited resources. However, the review focused only on a selection of countries that have enacted similar reforms and it is unclear if its conclusions are more widely generalizable.

Accordingly, the primary objective of this review is to summarize studies that have estimated the causal effect of a change in abortion law on women’s health services and outcomes. Additionally, we aim to examine heterogeneity in the impacts of abortion reforms, including variation across specific population sub-groups and contexts (e.g., due to variations in the intensity of enforcement and service delivery). Through this review, we aim to offer a higher-level view of the impact of abortion law reforms in LMICs, beyond what can be gained from any individual study, and to thereby highlight patterns in the evidence across studies, gaps in current research, and to identify promising programs and strategies that could be adapted and applied more broadly to increase access to safe abortion services.

The review protocol has been reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [ 40 ] (Additional file 1 ). It was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database CRD42019126927.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies.

This review will consider quasi-experimental studies which aim to estimate the causal effect of a change in a specific law or reform and an outcome, but in which participants (in this case jurisdictions, whether countries, states/provinces, or smaller units) are not randomly assigned to treatment conditions [ 41 ]. Eligible designs include the following:

Pretest-posttest designs where the outcome is compared before and after the reform, as well as nonequivalent groups designs, such as pretest-posttest design that includes a comparison group, also known as a controlled before and after (CBA) designs.

Interrupted time series (ITS) designs where the trend of an outcome after an abortion law reform is compared to a counterfactual (i.e., trends in the outcome in the post-intervention period had the jurisdiction not enacted the reform) based on the pre-intervention trends and/or a control group [ 42 , 43 ].

Differences-in-differences (DD) designs, which compare the before vs. after change in an outcome in jurisdictions that experienced an abortion law reform to the corresponding change in the places that did not experience such a change, under the assumption of parallel trends [ 44 , 45 ].

Synthetic controls (SC) approaches, which use a weighted combination of control units that did not experience the intervention, selected to match the treated unit in its pre-intervention outcome trend, to proxy the counterfactual scenario [ 46 , 47 ].

Regression discontinuity (RD) designs, which in the case of eligibility for abortion services being determined by the value of a continuous random variable, such as age or income, would compare the distributions of post-intervention outcomes for those just above and below the threshold [ 48 ].

There is heterogeneity in the terminology and definitions used to describe quasi-experimental designs, but we will do our best to categorize studies into the above groups based on their designs, identification strategies, and assumptions.

Our focus is on quasi-experimental research because we are interested in studies evaluating the effect of population-level interventions (i.e., abortion law reform) with a design that permits inference regarding the causal effect of abortion legislation, which is not possible from other types of observational designs such as cross-sectional studies, cohort studies or case-control studies that lack an identification strategy for addressing sources of unmeasured confounding (e.g., secular trends in outcomes). We are not excluding randomized studies such as randomized controlled trials, cluster randomized trials, or stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trials; however, we do not expect to identify any relevant randomized studies given that abortion policy is unlikely to be randomly assigned. Since our objective is to provide a summary of empirical studies reporting primary research, reviews/meta-analyses, qualitative studies, editorials, letters, book reviews, correspondence, and case reports/studies will also be excluded.

Our population of interest includes women of reproductive age (15–49 years) residing in LMICs, as the policy exposure of interest applies primarily to women who have a demand for sexual and reproductive health services including abortion.

Intervention

The intervention in this study refers to a change in abortion law or policy, either from a restrictive policy to a non-restrictive or less restrictive one, or vice versa. This can, for example, include a change from abortion prohibition in all circumstances to abortion permissible in other circumstances, such as to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, or on request with no requirement for justification. It can also include the abolition of existing abortion policies or the introduction of new policies including those occurring outside the penal code, which also have legal standing, such as:

National constitutions;

Supreme court decisions, as well as higher court decisions;

Customary or religious law, such as interpretations of Muslim law;

Medical ethical codes; and

Regulatory standards and guidelines governing the provision of abortion.

We will also consider national and sub-national reforms, although we anticipate that most reforms will operate at the national level.

The comparison group represents the counterfactual scenario, specifically the level and/or trend of a particular post-intervention outcome in the treated jurisdiction that experienced an abortion law reform had it, counter to the fact, not experienced this specific intervention. Comparison groups will vary depending on the type of quasi-experimental design. These may include outcome trends after abortion reform in the same country, as in the case of an interrupted time series design without a control group, or corresponding trends in countries that did not experience a change in abortion law, as in the case of the difference-in-differences design.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes.

Access to abortion services: There is no consensus on how to measure access but we will use the following indicators, based on the relevant literature [ 49 ]: [ 1 ] the availability of trained staff to provide care, [ 2 ] facilities are geographically accessible such as distance to providers, [ 3 ] essential equipment, supplies and medications, [ 4 ] services provided regardless of woman’s ability to pay, [ 5 ] all aspects of abortion care are explained to women, [ 6 ] whether staff offer respectful care, [ 7 ] if staff work to ensure privacy, [ 8 ] if high-quality, supportive counseling is provided, [ 9 ] if services are offered in a timely manner, and [ 10 ] if women have the opportunity to express concerns, ask questions, and receive answers.

Use of abortion services refers to induced pregnancy termination, including medication abortion and number of women treated for abortion-related complications.

Secondary outcomes

Current use of any method of contraception refers to women of reproductive age currently using any method contraceptive method.

Future use of contraception refers to women of reproductive age who are not currently using contraception but intend to do so in the future.

Demand for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who are currently using, or whose sexual partner is currently using, at least one contraceptive method.

Unmet need for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception.

Fertility rate refers to the average number of children born to women of childbearing age.

Neonatal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death of newborn babies within the first 28 days of life.

Maternal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth.

There will be no language, date, or year restrictions on studies included in this systematic review.

Studies have to be conducted in a low- and middle-income country. We will use the country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify LMICs (Additional file 2 ).

Search methods

We will perform searches for eligible peer-reviewed studies in the following electronic databases.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) (from 1946 to present)

Embase Classic+Embase on OvidSP (from 1947 to present)

CINAHL (1973 to present); and

Web of Science (1900 to present)

The reference list of included studies will be hand searched for additional potentially relevant citations. Additionally, a grey literature search for reports or working papers will be done with the help of Google and Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

Search strategy

A search strategy, based on the eligibility criteria and combining subject indexing terms (i.e., MeSH) and free-text search terms in the title and abstract fields, will be developed for each electronic database. The search strategy will combine terms related to the interventions of interest (i.e., abortion law/policy), etiology (i.e., impact/effect), and context (i.e., LMICs) and will be developed with the help of a subject matter librarian. We opted not to specify outcomes in the search strategy in order to maximize the sensitivity of our search. See Additional file 3 for a draft of our search strategy.

Data collection and analysis

Data management.

Search results from all databases will be imported into Endnote reference manager software (Version X9, Clarivate Analytics) where duplicate records will be identified and excluded using a systematic, rigorous, and reproducible method that utilizes a sequential combination of fields including author, year, title, journal, and pages. Rayyan systematic review software will be used to manage records throughout the review [ 50 ].

Selection process

Two review authors will screen titles and abstracts and apply the eligibility criteria to select studies for full-text review. Reference lists of any relevant articles identified will be screened to ensure no primary research studies are missed. Studies in a language different from English will be translated by collaborators who are fluent in the particular language. If no such expertise is identified, we will use Google Translate [ 51 ]. Full text versions of potentially relevant articles will be retrieved and assessed for inclusion based on study eligibility criteria. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or will involve a third reviewer as an arbitrator. The selection of studies, as well as reasons for exclusions of potentially eligible studies, will be described using a PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction

Data extraction will be independently undertaken by two authors. At the conclusion of data extraction, these two authors will meet with the third author to resolve any discrepancies. A piloted standardized extraction form will be used to extract the following information: authors, date of publication, country of study, aim of study, policy reform year, type of policy reform, data source (surveys, medical records), years compared (before and after the reform), comparators (over time or between groups), participant characteristics (age, socioeconomic status), primary and secondary outcomes, evaluation design, methods used for statistical analysis (regression), estimates reported (means, rates, proportion), information to assess risk of bias (sensitivity analyses), sources of funding, and any potential conflicts of interest.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers with content and methodological expertise in methods for policy evaluation will assess the methodological quality of included studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series risk of bias checklist [ 52 ]. This checklist provides a list of criteria for grading the quality of quasi-experimental studies that relate directly to the intrinsic strength of the studies in inferring causality. These include [ 1 ] relevant comparison, [ 2 ] number of times outcome assessments were available, [ 3 ] intervention effect estimated by changes over time for the same or different groups, [ 4 ] control of confounding, [ 5 ] how groups of individuals or clusters were formed (time or location differences), and [ 6 ] assessment of outcome variables. Each of the following domains will be assigned a “yes,” “no,” or “possibly” bias classification. Any discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer with expertise in review methodology if required.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [ 53 ].

Data synthesis

We anticipate that risk of bias and heterogeneity in the studies included may preclude the use of meta-analyses to describe pooled effects. This may necessitate the presentation of our main findings through a narrative description. We will synthesize the findings from the included articles according to the following key headings:

Information on the differential aspects of the abortion policy reforms.

Information on the types of study design used to assess the impact of policy reforms.

Information on main effects of abortion law reforms on primary and secondary outcomes of interest.

Information on heterogeneity in the results that might be due to differences in study designs, individual-level characteristics, and contextual factors.

Potential meta-analysis

If outcomes are reported consistently across studies, we will construct forest plots and synthesize effect estimates using meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed using the I 2 test where I 2 values over 50% indicate moderate to high heterogeneity [ 54 ]. If studies are sufficiently homogenous, we will use fixed effects. However, if there is evidence of heterogeneity, a random effects model will be adopted. Summary measures, including risk ratios or differences or prevalence ratios or differences will be calculated, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Analysis of subgroups

If there are sufficient numbers of included studies, we will perform sub-group analyses according to type of policy reform, geographical location and type of participant characteristics such as age groups, socioeconomic status, urban/rural status, education, or marital status to examine the evidence for heterogeneous effects of abortion laws.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted if there are major differences in quality of the included articles to explore the influence of risk of bias on effect estimates.

Meta-biases

If available, studies will be compared to protocols and registers to identify potential reporting bias within studies. If appropriate and there are a sufficient number of studies included, funnel plots will be generated to determine potential publication bias.

This systematic review will synthesize current evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health. It aims to identify which legislative reforms are effective, for which population sub-groups, and under which conditions.

Potential limitations may include the low quality of included studies as a result of suboptimal study design, invalid assumptions, lack of sensitivity analysis, imprecision of estimates, variability in results, missing data, and poor outcome measurements. Our review may also include a limited number of articles because we opted to focus on evidence from quasi-experimental study design due to the causal nature of the research question under review. Nonetheless, we will synthesize the literature, provide a critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence and discuss the potential effects of any limitations to our overall conclusions. Protocol amendments will be recorded and dated using the registration for this review on PROSPERO. We will also describe any amendments in our final manuscript.

Synthesizing available evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms represents an important step towards building our knowledge base regarding how abortion law reforms affect women’s health services and health outcomes; we will provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services, and scale up accessibility. This review will be of interest to service providers, policy makers and researchers seeking to improve women’s access to safe abortion around the world.

Abbreviations

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature

Excerpta medica database

Low- and middle-income countries

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols

International prospective register of systematic reviews

Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, Johnson BR, Tuncalp O, Assifi A, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010-14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guttmacher Institute. Induced Abortion Worldwide; Global Incidence and Trends 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-worldwide . Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, Kwok L, Onda T. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven progress and unequal access. NewYork: Guttmacher Institute; 2018.

Book Google Scholar

Fusco CLB. Unsafe abortion: a serious public health issue in a poverty stricken population. Reprod Clim. 2013;2(8):2–9.

Google Scholar

Rehnstrom Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, Klingberg-Allvin M. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2 .

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tuncalp O, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):E323–E33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benson J, Nicholson LA, Gaffikin L, Kinoti SN. Complications of unsafe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(2):117–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/11.2.117 .

Abiodun OM, Balogun OR, Adeleke NA, Farinloye EO. Complications of unsafe abortion in South West Nigeria: a review of 96 cases. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2013;42(1):111–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I. Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG. 2016;123(9):1489–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13552 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vlassoff M, Walker D, Shearer J, Newlands D, Singh S. Estimates of health care system costs of unsafe abortion in Africa and Latin America. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(3):114–21. https://doi.org/10.1363/3511409 .

Singh S, Darroch JE. Adding it up: costs and benefits of contraceptive services. Estimates for 2012. New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund; 2012.

Auger N, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Sauve R. Abortion and infant mortality on the first day of life. Neonatology. 2016;109(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442279 .

Krieger N, Gruskin S, Singh N, Kiang MV, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Reproductive justice & preventable deaths: state funding, family planning, abortion, and infant mortality, US 1980-2010. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:277–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.007 .

Banaem LM, Majlessi F. A comparative study of low 5-minute Apgar scores (< 8) in newborns of wanted versus unwanted pregnancies in southern Tehran, Iran (2006-2007). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(12):898–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802372390 .

Bhandari A. Barriers in access to safe abortion services: perspectives of potential clients from a hilly district of Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:87.

Seid A, Yeneneh H, Sende B, Belete S, Eshete H, Fantahun M, et al. Barriers to access safe abortion services in East Shoa and Arsi Zones of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. J Health Dev. 2015;29(1):13–21.

Arroyave FAB, Moreno PA. A systematic bibliographical review: barriers and facilitators for access to legal abortion in low and middle income countries. Open J Prev Med. 2018;8(5):147–68. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2018.85015 .

Article Google Scholar

Boland R, Katzive L. Developments in laws on induced abortion: 1998-2007. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2008;34(3):110–20. https://doi.org/10.1363/3411008 .

Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S, Johnson BR Jr, Ganatra B. Global Abortion Policies Database: a descriptive analysis of the legal categories of lawful abortion. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0183-1 .

United Nations Population Division. Abortion policies: A global review. Major dimensions of abortion policies. 2002 [Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/abortion/abortion-policies-2002.asp .

Johnson BR, Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S. Global abortion policies database: a new approach to strengthening knowledge on laws, policies, and human rights standards. Bmc Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0174-2 .

Haaland MES, Haukanes H, Zulu JM, Moland KM, Michelo C, Munakampe MN, et al. Shaping the abortion policy - competing discourses on the Zambian termination of pregnancy act. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0908-8 .

Schatz JJ. Zambia’s health-worker crisis. Lancet. 2008;371(9613):638–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60287-1 .

Erdman JN, Johnson BR. Access to knowledge and the Global Abortion Policies Database. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;142(1):120–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12509 .

Cleeve A, Oguttu M, Ganatra B, Atuhairwe S, Larsson EC, Makenzius M, et al. Time to act-comprehensive abortion care in east Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(9):E601–E2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30136-X .

Berer M, Hoggart L. Medical abortion pills have the potential to change everything about abortion. Contraception. 2018;97(2):79–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.12.006 .

Moseson H, Shaw J, Chandrasekaran S, Kimani E, Maina J, Malisau P, et al. Contextualizing medication abortion in seven African nations: A literature review. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(7-9):950–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1608207 .

Blystad A, Moland KM. Comparative cases of abortion laws and access to safe abortion services in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:351.

Berer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: in search of decriminalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):13–27.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Johnson BR, Mishra V, Lavelanet AF, Khosla R, Ganatra B. A global database of abortion laws, policies, health standards and guidelines. B World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):542–4. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.197442 .

Replogle J. Nicaragua tightens up abortion laws. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):15–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60011-7 .

Keogh LA, Newton D, Bayly C, McNamee K, Hardiman A, Webster A, et al. Intended and unintended consequences of abortion law reform: perspectives of abortion experts in Victoria, Australia. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2017;43(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101541 .

Levels M, Sluiter R, Need A. A review of abortion laws in Western-European countries. A cross-national comparison of legal developments between 1960 and 2010. Health Policy. 2014;118(1):95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.06.008 .

Serbanescu F, Morris L, Stupp P, Stanescu A. The impact of recent policy changes on fertility, abortion, and contraceptive use in Romania. Stud Fam Plann. 1995;26(2):76–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137933 .

Henderson JT, Puri M, Blum M, Harper CC, Rana A, Gurung G, et al. Effects of Abortion Legalization in Nepal, 2001-2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064775 .

Goncalves-Pinho M, Santos JV, Costa A, Costa-Pereira A, Freitas A. The impact of a liberalisation law on legally induced abortion hospitalisations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;203:142–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.037 .

Latt SM, Milner A, Kavanagh A. Abortion laws reform may reduce maternal mortality: an ecological study in 162 countries. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0705-y .

Clarke D, Muhlrad H. Abortion laws and women’s health. IZA discussion papers 11890. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics; 2018.

Benson J, Andersen K, Samandari G. Reductions in abortion-related mortality following policy reform: evidence from Romania, South Africa and Bangladesh. Reprod Health. 2011;8(39). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-39 .

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj-Brit Med J. 2015;349.

William R. Shadish, Thomas D. Cook, Donald T. Campbell. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, New York; 2002.

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098 .

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. The use of controls in interrupted time series studies of public health interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):2082–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy135 .

Meyer BD. Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat. 1995;13(2):151–61.

Strumpf EC, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Fixed effects and difference in differences. In: Methods in Social Epidemiology ed. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass; 2017.

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program. J Am Stat Assoc. 2010;105(490):493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. Am J Polit Sci. 2015;59(2):495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12116 .

Moscoe E, Bor J, Barnighausen T. Regression discontinuity designs are underutilized in medicine, epidemiology, and public health: a review of current and best practice. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(2):132–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.021 .

Dennis A, Blanchard K, Bessenaar T. Identifying indicators for quality abortion care: a systematic literature review. J Fam Plan Reprod H. 2017;43(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101427 .

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, Choi A, Fournier JP, Geier AK, et al. The accuracy of Google Translate for abstracting data from non-English-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019.

Reeves BC, Wells GA, Waddington H. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 5: a checklist for classifying studies evaluating the effects on health interventions-a taxonomy without labels. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.016 .

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD .

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Genevieve Gore, Liaison Librarian at McGill University, for her assistance with refining the research question, keywords, and Mesh terms for the preliminary search strategy.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Fonds de recherche du Quebec – Santé (FRQS) PhD doctoral awards and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant, “Examining the impact of social policies on health equity” (ROH-115209).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Purvis Hall 1020 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1A2, Canada

Foluso Ishola, U. Vivian Ukah & Arijit Nandi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

FI and AN conceived and designed the protocol. FI drafted the manuscript. FI, UVU, and AN revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Foluso Ishola .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist. This checklist has been adapted for use with systematic review protocol submissions to BioMed Central journals from Table 3 in Moher D et al: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 2015 4:1

Additional File 2:.

LMICs according to World Bank Data Catalogue. Country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify low- and middle-income countries

Additional File 3: Table 1

. Search strategy in Embase. Detailed search terms and filters applied to generate our search in Embase

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ishola, F., Ukah, U.V. & Nandi, A. Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 10 , 192 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Download citation

Received : 02 January 2020

Accepted : 08 June 2021

Published : 28 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Abortion law/policies; Impact

- Unsafe abortion

- Contraception

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Introduction: The Politics of Abortion 50 Years after Roe

Katrina Kimport is a professor with the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences and a medical sociologist with the ANSIRH program at the University of California, San Francisco. Her research examines the (re)production of inequality in health and reproduction, with a topical focus on abortion, contraception, and pregnancy. She is the author of No Real Choice: How Culture and Politics Matter for Reproductive Autonomy (2022) and Queering Marriage: Challenging Family Formation in the United States (2014) and co-author, with Jennifer Earl, of Digitally Enabled Social Change (2011). She has published more than 75 articles in sociology, health research, and interdisciplinary journals.

Rebecca Kreitzer is an associate professor of public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on gendered political representation and intersectional policy inequality in the US states. Much of her research focuses on the political dynamics of reproductive health care, especially surrounding contraception and abortion. She has published dozens of articles in political science, public policy, and law journals.

- Standard View

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Katrina Kimport , Rebecca Kreitzer; Introduction: The Politics of Abortion 50 Years after Roe . J Health Polit Policy Law 1 August 2023; 48 (4): 463–484. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-10451382

Download citation file:

- Reference Manager

Abortion is central to the American political landscape and a common pregnancy outcome, yet research on abortion has been siloed and marginalized in the social sciences. In an empirical analysis, the authors found only 22 articles published in this century in the top economics, political science, and sociology journals. This special issue aims to bring abortion research into a more generalist space, challenging what the authors term “the abortion research paradox,” wherein abortion research is largely absent from prominent disciplinary social science journals but flourishes in interdisciplinary and specialized journals. After discussing the misconceptions that likely contribute to abortion research siloization and the implications of this siloization for abortion research as well as social science knowledge more generally, the authors introduce the articles in this special issue. Then, in a call for continued and expanded research on abortion, the introduction to this special issue closes by offering three guiding practices for abortion scholars—both those new to the topic and those deeply familiar with it—in the hopes of building an ever-richer body of literature on abortion politics, policy, and law. The need for such a robust literature is especially acute following the US Supreme Court's June 2022 overturning of the constitutional right to abortion.

Abortion has been both siloed and marginalized in social science research. But because abortion is a perennially politically and socially contested issue as well as vital health care that one in four women in the United States will experience in their lifetime (Jones and Jerman 2022 ), it is imperative that social scientists make a change. This special issue brings together insightful voices from across disciplines to do just that—and does so at a particularly important historical moment. Fifty years after the United States Supreme Court's Roe v. Wade (1973) decision set a national standard amid disparate state policies on abortion, we again find ourselves in a country with a patchwork of laws about abortion. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (2022), the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion it had established in Roe , purportedly returning the question of legalization of abortion to the states. In the immediate aftermath of the Dobbs decision, state policies polarized, and public opinion shifted. This moment demands scholarly evaluation of where we have been, how we arrived at this moment, and what we should be attentive to in coming years. This special issue came about, in part, in response to the on-the-ground conditions of abortion in the United States.

As we argue below, the siloization of abortion research means that the social science literature broadly is not (yet) equipped to make sense of this moment, our history, and what the future holds. First, though, we make a case for the importance of political scientists, economists, and sociologists studying abortion. Then we describe the siloization of abortion research through what we call the “abortion research paradox,” wherein abortion research—despite its social and political import—is curiously absent from top disciplinary journals, even as it thrives in other publication venues that are often interdisciplinary and usually specialized. We theorize some reasons for this siloization and discuss the consequences, both for generalist knowledge and for scientific understanding of abortion. We then introduce the articles in this special issue, noting the breadth of methodological, topical, and theoretical approaches to abortion research they demonstrate. Finally, we offer three suggestions for scholars—both those new to abortion research and those already deeply familiar with it—embarking on abortion research in the hopes of building an ever-richer body of literature on abortion politics, policy, and law.

- Why Abortion?

Abortion has arguably shaped the American political landscape more than any other domestic policy issue in the last 50 years. Since the Supreme Court initially established a nationwide right to abortion in Roe v. Wade (1973), debate over this right has influenced elections at just about every level of office (Abramowitz 1995 ; Cook, Hartwig, and Wilcox 1993 ; Cook, Jelen, and Wilcox 1994 ; Cook, Jelen, and Wilcox 1992 ; Paolino 1995 ; Roh and Haider-Markel 2003 ), inspired political activism (Carmines and Woods 2002 ; Killian and Wilcox 2008 ; Maxwell 2002 ; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995 ) and social movements (Kretschmer 2014 ; Meyer and Staggenborg 1996 , 2008 ; Munson 2010a , Munson 2010b ; Rohlinger 2006 ; Staggenborg 1991 ), and fundamentally structured partisan politics (Adams 1997; Carsey and Layman 2006 ; Killian and Wilcox 2008 ). Position on abortion is frequently used as the litmus test for those seeking political office (Flaten 2010 ; Kreitzer and Osborn 2019 ). Opponents to legal abortion have transformed the federal judiciary (Hollis-Brusky and Parry 2021 ; Hollis-Brusky and Wilson 2020 ). Indeed, abortion is often called the quintessential “morality policy” issue (Kreitzer 2015 ; Kreitzer, Kane, and Mooney 2019 ; Mooney 2001 ; Mucciaroni, Ferraiolo, and Rubado 2019 ) and “ground zero” in the prominent culture wars that have polarized Americans (Adams 1997 ; Lewis 2017 ; Mouw and Sobel 2001 ; Wilson 2013 ). Almost fifty years after Roe v. Wade , in June 2022, the US Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion in its Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization decision, ushering in a new chapter of political engagement on abortion.

But abortion is not simply an abstract political issue; it is an extremely common pregnancy outcome. Indeed, as noted above, about one in four US women will get an abortion in her lifetime (Jones and Jerman 2022 ), although the rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion vary substantially across racial and socioeconomic groups (Dehlendorf, Harris, and Weitz 2013 ; Jones and Jerman 2022 ). Despite rampant misinformation claiming otherwise, abortion is a safe procedure (Raymond and Grimes 2012 ; Upadhyay et al. 2015 ), reduces physical health consequences and mortality (Gerdts et al. 2016 ), and does not cause mental health issues (Charles et al. 2008 ; Major et al. 2009 ) or regret (Rocca et al. 2013 , 2015 , 2020 ). Abortion also has a significant impact on people's lives beyond health outcomes. Legal abortion is associated with educational attainment (Everett et al. 2019 ; Ralph et al. 2019 ; Mølland 2016 ) as well as higher female labor force participation, and it affects men's and women's long-term earning potential (Bernstein and Jones 2019 ; Bloom et al. 2009 ; Everett et al. 2019 ; Kalist 2004 ). Access to abortion also shapes relationship satisfaction and stability (Biggs et al. 2014 ; Mauldon, Foster, and Roberts 2015 ). The preponderance of evidence, in other words, demonstrates substantial benefits and no harms to allowing pregnant people to choose abortion.

Yet access to abortion in the United States has been rapidly declining for years. Most abortion care in the United States takes place in stand-alone outpatient facilities that primarily provide reproductive health care (Jones, Witwer, and Jerman 2019 ). As antiabortion legislators in some states have advanced policies that target these facilities, the number of abortion clinics has decreased (Gerdts et al. 2022 ; Venator and Fletcher 2021 ), leaving large geographical areas lacking an abortion facility (Cartwright et al. 2018 ; Cohen and Joffe 2020 ) and thus diminishing pregnant people's ability to obtain abortion care when and where they need it.

The effects of policies regulating abortion, including those that target facilities, have been unevenly experienced, with people of color (Jones and Jerman 2022 ), people in rural areas (Bearak, Burke, and Jones 2017 ), and those who are financially struggling (Cook et al. 1999 ; Roberts et al. 2019 ) disproportionately affected. Even before the Dobbs decision overturned the constitutional right to abortion, the American landscape was characterized by ever-broadening contraception deserts (Axelson, Sealy, and McDonald-Mosley 2022 ; Barber et al. 2019 ; Kreitzer et al. 2021 ; Smith et al. 2022 ), maternity care deserts (Simpson 2020 ; Taporco et al. 2021 ; Wallace et al. 2021 ), and abortion deserts (Cartwright et al. 2018 ; Cohen and Joffe 2020 ; Engle and Freeman 2022 ; McNamara et al. 2022 ; Pleasants, Cartwright, and Upadhyay 2022 ). After Dobbs , access to abortion around the country changed in a matter of weeks. In the 100 days after Roe was overturned, at least 66 clinics closed in 15 states, with 14 of those states no longer having any abortion facilities (Kirstein et al. 2022 ). In this moment of heightened contention about an issue with a long history of social and political contestation, social scientists have a rich opportunity to contribute to scientific knowledge as well as policy and practice that affect millions of lives. This special issue steps into that opportunity.

- The Abortion Research Paradox

This special issue is also motivated by what we call the abortion research paradox. As established above, abortion fundamentally shapes politics in a myriad of ways and is a very common pregnancy outcome, with research consistently demonstrating that access to abortion is consequential and beneficial to people's lives. However, social science research on abortion is rarely published in top disciplinary journals. Abortion is a topic of clear social science interest and is well suited for social science inquiry, but it is relatively underrepresented as a topic in generalist social science journals. To measure this underrepresentation empirically, we searched for original research articles about abortion in the United Sates in the top journals of political science, sociology, and economics. We identified the top three journals for each discipline by considering journal reputation within their respective discipline as well as impact factors and Google Scholar rankings. (There is room for debate about what makes a journal a “top” general interest journal, but that is beyond our scope. Whether these journals are exactly the top three is debatable; nonetheless, these are undoubtedly among the top general-interest or “flagship” disciplinary journals and thus representative of what the respective disciplines value as top scholarship.) Then we searched specified journal databases for the keyword “abortion” for articles published in this century (i.e., 2000–2021), excluding commentaries and book reviews. We found few articles about abortion: just seven in economics journals, eight in political science journals, and seven in sociology journals. We read the articles and classified each into one of three categories: articles primarily about abortion; articles about more than one aspect of reproductive health, inclusive of abortion; or articles about several policy issues, among which abortion is one ( table 1 ).

In the three top economics journals, articles about abortion focused on the relationships between abortion and crime or educational attainment, or on the impact of abortion policies on trends in the timing of first births of women (Bitler and Zavodny 2002 ; Donohue III and Levitt 2001 ; Myers 2017 ). Articles that studied abortion as one among several topics also studied “morally controversial” issues (Elías et al. 2017 ), the electoral implications of abortion (Glaeser, Ponzetto, and Shapiro 2005 ; Washington 2008 ), or contraception (Bailey 2010 ). Articles published in the three top political science journals that focused primarily on abortion evaluated judicial decision-making and legitimacy (Caldarone, Canes-Wrone, and Clark 2009 ; Zink, Spriggs, and Scott 2009 ) or public opinion (Kalla, Levine, and Broockman 2022 ; Rosenfeld, Imai, and Shapiro 2016 ). More commonly, abortion was one of several (or many) different issues analyzed, including government spending and provision of services, government help for African Americans, law enforcement, health care, education, free speech, Hatch Act restrictions, and the Clinton impeachment. The degree to which these articles are “about abortion” varies considerably. In the three top sociology journals, articles represented a slightly broader range of topics, including policy diffusion (Boyle, Kim, and Longhofer 2015 ), public opinion (Mouw and Sobel 2001 ), social movements (Ferree 2003 ), and crisis pregnancy centers (McVeigh, Crubaugh, and Estep 2017 ). Unlike in economics and political science, articles in sociology on abortion mostly focused directly on abortion.

The Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law ( JHPPL ) would seem well positioned to publish research on abortion. Yet, even in JHPPL , abortion research is not very common. In the same time period (2000–2021), JHPPL published five articles on reproductive health: two articles on abortion (Daniels et al. 2016 ; Kimport, Johns, and Upadhyay 2018 ), one on contraception (Kreitzer et al. 2021 ), one on forced interventions on pregnant people (Paltrow and Flavin 2013 ), and one about how states could respond to the passage of the Affordable Care Act mandate regarding reproductive health (Stulberg 2013 ).

This is not to say that there is no extensive, rigorous published research on abortion in the social science literature. Interdisciplinary journals that are focused on reproductive health, such as Contraception and Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health , as well as health research journals, such as the American Journal of Public Health and Social Science & Medicine , regularly published high-quality social science research on abortion during the focal time period. Research on abortion can also be found in disciplinary subfield journals. In the same time period addressed above, the Journal of Women, Politics, and Public Policy and Politics & Gender— two subfield journals focused on gender and politics—each published around 20 articles that mentioned abortion in the abstract. In practice, while this means excellent research on abortion is published, the net effect is that abortion research is siloed from other research areas in the disciplines of economics, political science, and sociology. This special issue aims to redress some of this siloization and to inspire future scholarship on abortion. Our motivation is not simply premised on quantitative counts, however. As we assert below, abortion research siloization has significant consequences for knowledge—and especially for real people's lives. First, though, we consider some of the possible reasons for this siloization.

- The Origins of Siloization

We do not know why abortion research is not more commonly published in top disciplinary journals, given the topic's clear importance in key areas of focus for these disciplines, including public discourse, politics, law, family life, and health. The siloing and marginalization of abortion is likely related to several misconceptions. For one, because of social contention on the issue, peer reviewers may not have a deep understanding of abortion as a research topic, may express hostility to the topic, or may believe that abortion is exceptional in some way—a niche or ungeneralizable research topic better published in a subfield journal. Scholars themselves may share this mischaracterization of abortion. As Borgman ( 2014 ) argues about the legal arena, and as Roberts, Schroeder, and Joffe ( 2020 ) provide evidence of in medicine, abortion is regularly treated as exceptional, making it both definitional and reasonable that abortion be treated differently in the law and in health care from other medical experiences. Scholars are not immune to social patterns that exceptionalize abortion. In their peer and editor reviews, they may inappropriately—and perhaps inadvertently—draw on their social, rather than academic, knowledge. For scholars of abortion, reviews premised on social knowledge may not be constructive to strengthening the research, and additional labor may be required to educate reviewers and editors on the academic parameters of the topic, including which social assumptions about abortion are scientifically inaccurate. Comments from authors educating editors and peer reviewers on abortion research may then counterintuitively reinforce the (mis)perception that abortion research is niche and not of general interest.

Second, authors' negative experiences while trying to publish about abortion or reproductive health in top disciplinary journals may compound as scholars share information about journals. This is the case for research on gender; evidence from political science suggests that certain journals are perceived as more or less likely to publish research on gender (Brown et al. 2020 ). Such reputations, especially for venues that do not publish abortion research, may not even be rooted in negative experiences. The absence of published articles on abortion may itself dissuade scholars from submitting to a journal based on an educated guess that the journal does not welcome abortion research. Regardless of the veracity of these perceptions, certain journals may get a reputation for publishing on abortion (or not), which then may make future submissions of abortion research to those outlets more (or less) likely. After all, authors seek publication venues where they believe their research will get a robust review and is likely to be published. This pattern may be more common for some author groups than others. Research from political science suggests women are more risk averse than men when it comes to publishing strategies and less likely to submit manuscripts to journals where the perceived likelihood of successful publication is lower (Key and Sumner 2019 ). Special issues like this one are an important way for journals without a substantial track record of publishing abortion research to establish their willingness to do so.

Third, there might be a methodological bias, which unevenly intersects with some author groups. Top disciplinary journals are more likely to publish quantitative approaches rather than qualitative ones, which can result in the exclusion of women and minority scholars who are more likely to utilize mixed or qualitative methods (Teele and Thelen 2017 ). To the extent that investigations of abortion in the social sciences have utilized qualitative rather than quantitative methods, that might contribute to the underrepresentation of abortion-focused scholarship in top disciplinary journals.

Stepping back from the idiosyncrasies of peer review and methodologies, a fourth explanation for why abortion research is not more prominent in generalist social science journals may arise far earlier than the publishing process. PhD-granting departments in the social sciences may have an undersupply of scholars with expertise in reproductive health who can mentor junior scholars interested in studying abortion. (We firmly believe one need not be an expert in reproductive health to mentor junior scholars studying reproductive health, so this explanation only goes so far.) Anecdotally, we have experienced and heard many accounts of scholars who were discouraged from focusing on abortion in dissertation research because of advisors', mentors', and senior scholars' misconceptions about the topic and about the viability of a career in abortion research. In data provided to us by Key and Sumner from their analysis of the “leaky pipeline” in the publication of research on gender at top disciplinary journals in political science (Key and Sumner 2019 ), there were only nine dissertations written between 2000 and 2013 that mention abortion in the abstract, most of which are focused on judicial behavior or political party dynamics rather than focusing on abortion policy itself. If few junior scholars focus on abortion, it makes sense there may be an undersupply of cutting-edge social science research on abortion submitted to top disciplinary journals.

- The Implications of Siloization

The relative lack of scholarly attention to abortion as a social phenomenon in generalist journals has implications for general scholarship. Most concerningly, it limits our ability to understand other social phenomena for which the case of abortion is a useful entry point. For example, the case of abortion as a common, highly safe medical procedure is useful for examining medical innovations and technologies, such as telemedicine. Similarly, given the disparities in who seeks and obtains abortion care in the United States, abortion is an excellent case study for scholars interested in race, class, and gender inequality. It also holds great potential as an opportunity for exploration of public opinion and attitudes, particularly as a case of an issue whose ties to partisan politics have solidified over time and that is often—but not always—“moralized” in policy engagement (Kreitzer, Kane, and Mooney 2019 ). Additionally, there are missed opportunities to generate theory from the specifics of abortion. For example, there is ample evidence of abortion stigma and stigmatization (Hanschmidt et al. 2016 ) and of their effects on people who obtain abortions (Sorhaindo and Lavelanet 2022 ). This research is often unmoored from existing theorization on stigmatization, however, because the bulk of the stigma literature focuses on identities; and having had an abortion is not an identity the same way as, for example, being queer is. (For a notable exception to this trend, see Beynon-Jones 2017 .)

There is, it must be noted, at least one benefit of abortion research being regularly siloed within social science disciplines. The small but growing number of researchers engaged in abortion research has often had to seek mentorship and collaborations outside their disciplines. Indeed, several of the articles included in this special issue come from multidisciplinary author teams, building bridges between disciplinary literatures and pushing knowledge forward. Social scientists studying abortion regularly engage with research by clinicians and clinician-researchers, which is somewhat rare in the academy. The interdisciplinary journals noted above that regularly publish social science abortion research ( Contraception and Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health ) also regularly publish clinical articles and are read by advocates and policy makers. In other words, social scientists studying abortion frequently reach audiences that include clinicians, advocates, and policy makers, marking an opportunity for social science research to influence practice.

The siloization of abortion research in the social sciences affects more than broad social science knowledge; it also dramatically shapes our understanding of abortion. When abortion researchers are largely relegated to their own spaces, they risk missing opportunities to learn from other areas of scholarship that are not related to abortion. Lacking context from other topics, abortion scholars may inaccurately understand an aspect of abortion as exceptional that is not, or they may reinvent the proverbial theoretical wheel to describe an abortion-related phenomenon that is not actually unique to abortion. For example, scholars have studied criminalized behavior for decades, offering theoretical insights and methodological best practices for research on illegal activities. With abortion now illegal in many states, abortion researchers can benefit from drawing on that extant literature to examine the implications of illegality, identifying which aspects of abortion illegality are unique and which are common to other illegal activities. Likewise, methodologically, abortion researchers can learn from other researchers of illegal activities about how to protect participants' confidentiality.

The ontological and epistemological implications for the siloization of abortion research extend beyond reproductive health. When abortion research is not part of the central discussions in economics, political science, and sociology, our understanding of health policy, politics, and law is impoverished. We thus miss opportunities to identify and address chronic health disparities and health inequities, with both conceptual and practical consequences. These oversights matter for people's lives. Following the June 2022 Dobbs decision, millions of people with the capacity of pregnancy are now barred from one key way to control fertility: abortion. The implications of scholars' failure to comprehensively grapple with the place of abortion in health policy, politics, and law are playing out in those people's lives and the lives of their loved ones.

Articles in this Special Issue

In this landscape, we offer this special issue on “The Politics of Abortion 50 Years After Roe .” We seek in this issue to illustrate some of the many ways abortion can and should be studied, with benefits not only for scholarly knowledge about abortion and its role in policy, politics, and law but also for general knowledge about health policy, politics, and law themselves.