We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Topics

40 Family Issues Research Paper Topics

Read Also: The Best Research Paper Writing Service For Writing Research Papers

40 Marriage and Family Research Topics for any Taste

- Parental neglect. Is it enough for a kid to have food, clothes, and shelter to grow up healthy?

- Divorce and its consequences for all the family members. Minimizing the negative impact of divorce

- Toxic and narcissistic parents. Overcoming the trauma of a dysfunctional family

- To live up to the family expectation: what to do if they are too high for a human being?

- Family violence: where is the point of no return?

- Sexual abuse in the family. The strategy of escaping and organizations that can help

- Toxic and abusive relationship. The psychologies issues of breaking up with toxic partner

- Substance abuse in the family. It is always possible to save yourself, but is it possible to save the rest?

- War Veterans and their families. Do Vets the only ones there who need help?

- Accepting the LGBTQ+ member of the family

- Getting out of the closet: what is like to be an LGBTQ+person in a conservative family?

- Loss of a family member: stages of grief of children and adults. How to cope together?

- Religious conflicts in families: what to do and how to solve?

- Teenage delinquency: when it turns to be more than natural seeking independence?

- Fostering a child: what problems can the parents face?

- Generation gap. The difference in morals and culture. Is it normal?

- Living with senile family members: how to cope and avoid emotional burnout?

- Mentally challenged family members: how to integrate them into society?

- The importance of family support for people with disabilities

- Pregnancy and the first year of having a baby: do tiredness and depression make people bad parents?

- The types of relationship in the family: are they healthy and just unusual or something is harmful to family members?

- Life after disasters: how to put life together again? The importance of family support

- The issue of an older sibling. How to make every kid feel equally loved?

- Gender discrimination in families. Gender roles and expectations

- Multicultural families: how do their values get along?

- Children from previous marriages: how to help them accept the new family?

- Childhood traumas of parents: helping them not to transfer them to the next generation

- Every family can meet a crisis: how to live it through in a civilized way?

- Family counseling: why it is so important?

- Accidentally learned the secrets of the family: how to cope with unpleasant truth?

- Adultery: why it happens and what to do to prevent it?

- Career choice: how to save the relationships with the family and not inherit the family business?

- The transition to adult life: the balance between family support and letting the young adult try living their own life

- Unwanted activities: shall the family take warning or it is just trendy now?

- Returning of a family member from prison: caution versus unconditional love

- A family member in distress: what can you do to actually help when someone close to you gets in serious troubles?

- The absence of love. What to do if you should love someone but can’t?

- Ageism in families. Are older people always right?

- Terminal diseases and palliative care. How to give your family member a good life?

- Where can seek help the members of the dysfunctional families?

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Get a 50% off

Study smarter with Chegg and save your time and money today!

Research Question Examples 🧑🏻🏫

25+ Practical Examples & Ideas To Help You Get Started

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | October 2023

A well-crafted research question (or set of questions) sets the stage for a robust study and meaningful insights. But, if you’re new to research, it’s not always clear what exactly constitutes a good research question. In this post, we’ll provide you with clear examples of quality research questions across various disciplines, so that you can approach your research project with confidence!

Research Question Examples

- Psychology research questions

- Business research questions

- Education research questions

- Healthcare research questions

- Computer science research questions

Examples: Psychology

Let’s start by looking at some examples of research questions that you might encounter within the discipline of psychology.

How does sleep quality affect academic performance in university students?

This question is specific to a population (university students) and looks at a direct relationship between sleep and academic performance, both of which are quantifiable and measurable variables.

What factors contribute to the onset of anxiety disorders in adolescents?

The question narrows down the age group and focuses on identifying multiple contributing factors. There are various ways in which it could be approached from a methodological standpoint, including both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Do mindfulness techniques improve emotional well-being?

This is a focused research question aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific intervention.

How does early childhood trauma impact adult relationships?

This research question targets a clear cause-and-effect relationship over a long timescale, making it focused but comprehensive.

Is there a correlation between screen time and depression in teenagers?

This research question focuses on an in-demand current issue and a specific demographic, allowing for a focused investigation. The key variables are clearly stated within the question and can be measured and analysed (i.e., high feasibility).

Examples: Business/Management

Next, let’s look at some examples of well-articulated research questions within the business and management realm.

How do leadership styles impact employee retention?

This is an example of a strong research question because it directly looks at the effect of one variable (leadership styles) on another (employee retention), allowing from a strongly aligned methodological approach.

What role does corporate social responsibility play in consumer choice?

Current and precise, this research question can reveal how social concerns are influencing buying behaviour by way of a qualitative exploration.

Does remote work increase or decrease productivity in tech companies?

Focused on a particular industry and a hot topic, this research question could yield timely, actionable insights that would have high practical value in the real world.

How do economic downturns affect small businesses in the homebuilding industry?

Vital for policy-making, this highly specific research question aims to uncover the challenges faced by small businesses within a certain industry.

Which employee benefits have the greatest impact on job satisfaction?

By being straightforward and specific, answering this research question could provide tangible insights to employers.

Examples: Education

Next, let’s look at some potential research questions within the education, training and development domain.

How does class size affect students’ academic performance in primary schools?

This example research question targets two clearly defined variables, which can be measured and analysed relatively easily.

Do online courses result in better retention of material than traditional courses?

Timely, specific and focused, answering this research question can help inform educational policy and personal choices about learning formats.

What impact do US public school lunches have on student health?

Targeting a specific, well-defined context, the research could lead to direct changes in public health policies.

To what degree does parental involvement improve academic outcomes in secondary education in the Midwest?

This research question focuses on a specific context (secondary education in the Midwest) and has clearly defined constructs.

What are the negative effects of standardised tests on student learning within Oklahoma primary schools?

This research question has a clear focus (negative outcomes) and is narrowed into a very specific context.

Need a helping hand?

Examples: Healthcare

Shifting to a different field, let’s look at some examples of research questions within the healthcare space.

What are the most effective treatments for chronic back pain amongst UK senior males?

Specific and solution-oriented, this research question focuses on clear variables and a well-defined context (senior males within the UK).

How do different healthcare policies affect patient satisfaction in public hospitals in South Africa?

This question is has clearly defined variables and is narrowly focused in terms of context.

Which factors contribute to obesity rates in urban areas within California?

This question is focused yet broad, aiming to reveal several contributing factors for targeted interventions.

Does telemedicine provide the same perceived quality of care as in-person visits for diabetes patients?

Ideal for a qualitative study, this research question explores a single construct (perceived quality of care) within a well-defined sample (diabetes patients).

Which lifestyle factors have the greatest affect on the risk of heart disease?

This research question aims to uncover modifiable factors, offering preventive health recommendations.

Examples: Computer Science

Last but certainly not least, let’s look at a few examples of research questions within the computer science world.

What are the perceived risks of cloud-based storage systems?

Highly relevant in our digital age, this research question would align well with a qualitative interview approach to better understand what users feel the key risks of cloud storage are.

Which factors affect the energy efficiency of data centres in Ohio?

With a clear focus, this research question lays a firm foundation for a quantitative study.

How do TikTok algorithms impact user behaviour amongst new graduates?

While this research question is more open-ended, it could form the basis for a qualitative investigation.

What are the perceived risk and benefits of open-source software software within the web design industry?

Practical and straightforward, the results could guide both developers and end-users in their choices.

Remember, these are just examples…

In this post, we’ve tried to provide a wide range of research question examples to help you get a feel for what research questions look like in practice. That said, it’s important to remember that these are just examples and don’t necessarily equate to good research topics . If you’re still trying to find a topic, check out our topic megalist for inspiration.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Search All Records

- Collections Catalog

- What's New

- Digitize New York

- Articles & Guides

- Webinar Library

- Most Recent Issue

- Research Services

- New York Family History School

- NYG&B at the NYPL

- Events List

- NYS Family History Conference

- 2024 Programming

- NYG&B Store

- Flagship Publications

- Internships

- 1869 Circle

- Team & Leadership

- Year in Review

- Career Opportunities

Are you asking the right genealogy research question?

Tracing your family history and discovering interesting stories about your ancestors is an exciting way to maintain a rich connection to the past. But tracking down your relatives and finding the evidence you need is not always an easy task.

Searching the many records available on the internet has become so easy that it can be tempting to simply plug in a name and date, and then begin browsing through records. But this unfocused approach can cause you to feel overwhelmed, and is not the best approach to finding out accurate information about your family.

An unfocused search is less likely to find the information you need, and even worse, it can lead you down a wrong research path based on incorrect information.

Genealogy is a skill and requires a solid foundation. Similar to the Scientific Method, if you follow the appropriate genealogy research steps and best practices, you’ll be much more successful and your findings will be more likely to be your true ancestors.

Thinking carefully about your research question is the perfect place for a beginner to start before searching. If you just recently interviewed your relatives at a family gathering , the next step is to formulate your first research question.

Even intermediate and advanced genealogists can benefit from reflecting on the research questions they have been asking, to ensure no bad habits are being formed.

What is a research question and why is it important?

Research questions should be specific.

Put simply, a research question forms the basis of your search. Simply ask yourself what information you want to know - research questions can be general or specific, though the more specific they are, the better.

For instance, a general research question could be something like “What was the life of my great-grandmother like?” This is an excellent starting question, but think about how it may guide your search - does this question give us a clear idea of a specific piece of information to seek? Not exactly.

We can focus our research even more by generating a more specific research question from the general one. For instance, “When and where was my great-grandmother born?” or “Where did my great-grandmother live in 1940?” A question like this will set you on the best path.

A good research question is achievable and motivating

The primary reason to develop a well-thought-out research question is that it focuses your research. Genealogy can feel overwhelming - we can all relate to the burning desire to know everything about our ancestors. But clearly, nobody is going to find out everything in a single research session.

When you break up your quest into achievable bits and pieces, it helps you recognize the progress you're making. Specific research questions are highly answerable - before you know it, you'll be crossing the question off your list and forming the next one! It's a great feeling.

Specific research questions like the examples above will focus your search into a much more manageable quest - for instance, if you know you’re seeking information on an ancestor’s birth, you can safely narrow down your search to only include records that would contain birth information. Or, using the other example, if you’re looking for a place of residence in 1940, you can confidently search the 1940 census first.

Research questions help us help you

A good research question can also help you communicate effectively with other researchers or experts who you would like guidance from.

If you’re preparing for a research consultation , or are looking for help at an expert’s conference booth, be ready with a specific research question! A good research question can help you get the most out of your professional consultation .

Experts and professionals will be far more helpful if they're presented with a specific research question. It's very common for our experts to hear a researcher ask a question like "Can you help me find my family who lived in New York State in the 1800s?" With such a broad question, it's very difficult for an expert to recommend a place to look or an approach to solving your problem.

When asked something more specific, like "I'm trying to find the birth record of my great-grandmother, who lived in Erie County in the 1800s" an expert is far more likely to provide useful information.

Even if you don't know the location or time period, asking "I'm looking for my great-grandmother's birth record" will be an excellent starting point if you're consulting with an expert.

Subscribe to the NYG&B eNews

The latest NY records news, expert genealogy tips, and fascinating stories, delivered twice a month to your inbox!

Tips for forming a research question

What do i already know.

If you’re not even sure what research question you want to ask, the first thing you need to think about is “what do I already know?” and “what’s missing?”

This is also an excellent habit for intermediate and advanced genealogists as well - organize a beginning of the year audit to get yourself on the right course for 2019!

Begin by organizing all the family records you have proof of - if you’re just beginning and don’t yet have any proof, that’s okay too.

Create a one-sheet document for each specific family member, and detail everything you know about them.

If you already have some records related to them, this is where you want to indicate that. Citations will help you remember where information came from, and help you locate it again later. If you don’t yet have any records, write down anything you can gather from other family members or pieces of information you may have heard in the past.

It’s okay if they’re not backed up by documentary evidence yet - this information will help you form research questions or guide your research question-focused searches.

What do I want to know, or need to prove?

Now, identify the blank spaces. What would you like to know? What information do you have that needs to be backed up with documentary evidence?

A genealogy best-practice is to complete as much research as possible on a single family unit or generation before moving onto the next one.

Records from one generation will often contain clues to help you find other family members later on (such as the name of a witnesses, parents, or godparents).

Here is where you form your specific research question - it’s always a good idea to begin by seeking vital records - birth, marriage, and death records - for each individual. Remember, even if you have a general question such as “What was the life of my great-grandmother like,” this can be broken down into finite, achievable questions.

Go beyond names and dates

Seeking out records that prove the names, dates, and places associated with the key events in your ancestor's lifetime is a good place to start because this information forms the skeleton of your understanding.

But don't leave those bones bare!

Genealogy research is based on facts and evidence but is also rich and colorful. Don't be afraid to ask research questions about what life was like or what their interests were. These can be fun and rewarding questions to answer.

For example, an inventory in an ancestor's probate file may tell you that he or she loved to read and had an extensive library; a newspaper might mention a quarrel with a neighbor over runaway livestock; or religious records can offer a glimpse at our ancestors' personal beliefs and the communities they belonged to.

Learning more about your relative’s job, community, hobby, beliefs, or interests will make your research more rewarding and your connection to your family history richer.

It's always a good idea to look to professional genealogy researchers and writers for examples of research questions. Take some time to peruse a scholarly genealogical journal, such as The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record - these journals accept only the highest-quality genealogy writing and are excellent examples of the kind of thoroughness all genealogists should aspire to emulate.

Read the latest issue of The Record , or search the full archives of The Record in our eLibrary and pay close attention to the kind of research questions the authors of each article ask.

You'll see how a good, focused research question can help form a research plan, which is the next step in your own process. Once you have formed a research question, it's time to make a research plan.

A good research plan involves thinking about more questions - such as when and where the event your research question investigates may have occurred, and also what kind of record sets to look in.

Like a good research question, a good research plan will wind up saving you a lot of time and frustration and is crucial to successful research. Keep an eye out for a coming blog on this subject!

If you have already formed a great research question, and are now wondering about formulating your research plan, you may want to schedule a consultation with an NYG&B genealogist to receive personalized expertise on next steps for your own research.

Looking to start researching your family? Interview your relatives and grow your family tree

11 ways to use the nyg&b website to improve your skills and find ancestors, when you can benefit from a professional genealogy consultation.

- Log in to post comments

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee on the Science of Research on Families; Olson S, editor. Toward an Integrated Science of Research on Families: Workshop Report. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

Toward an Integrated Science of Research on Families: Workshop Report.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

5 Family Research Methods and Frameworks: Examples from the Study of Biomarkers, Child Health, and Econometric Methods

A major objective of the workshop was to examine methodologies used in family research to explore how different kinds of studies could be combined to yield a deeper and more accurate picture of family structures, processes, and relationships. In family research, biological and behavioral processes are often inseparable, but significant advances have recently emerged that offer new opportunities for distinguishing and measuring these processes with greater precision. The presentations summarized in this chapter demonstrate both the great potential of incorporating biological measures into family research and the considerable challenges in doing so.

Yet the integration of biological measures into family research can be difficult. The relationships between biological mechanisms and specific behaviors (such as parenting practices) are typically complex. In addition, integrating biological and behavioral research typically requires close collaboration among investigators with different backgrounds, training, and methodological perspectives.

It is important to note here that some domains of family research were beyond the scope of this single workshop. For example, the full range of biobehavioral approaches—including developmental epigenetics, gene-environment interaction, and developmental neuroscience—have all produced large new fields of research with relevance to the study of families in recent years. These are worth more attention, but it was not possible to integrate them into this workshop.

The presentations did review some focused sets of methodologies and concerns. This chapter looks at three research approaches: family research on the biological stress response system, the effects of family life on child health, and the contributions of econometric studies to causal inference in family research. The research methodologies used in each of these areas are distinct, yet they share certain concerns and approaches that may offer a way of linking disciplines into multidisciplinary efforts.

- ASSESSING THE BIOLOGICAL STRESS SYSTEM: CONSIDERATIONS FOR FAMILY RESEARCH

Environmental factors and life experiences affect human development, behavior, and health through their impact on physiological processes, such as activity of the biological stress response system. The activity of one component of this system—known as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis—affects nearly every organ system in the body, with impacts on cognition, emotion, memory, behavior, and health. Darlene Kertes, assistant professor of psychology at the University of Florida, described some of the strategies and challenges in examining the HPA axis in family research. She highlighted the need for methodological development to facilitate integration of multiple levels of analysis, from genes to the social environment.

The activity of the HPA axis is critical to maintaining homeostatic processes and facilitating adaptation to physical and psychological stressors. Two streams of input relay information about both systemic stressors, such as pain and inflammation, and psychogenic stressors, including actual and perceived threats in the environment. Both inputs act on the hypothalamus to trigger the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone. This initiates a biological cascade resulting in the release of glucocorticoids (cortisol in humans) into general circulation. Via feedback loops, cortisol acts to terminate the stress response as well as to sensitize brain regions involved in fear to shape an individual's future behavioral and physiological responses to threat. Long-term effects of cortisol are achieved by its action as a transcription factor regulating gene expression in target tissues. Thus, the HPA axis is an adaptive system in which life experiences affect responses to future events, with potentially widespread consequences for behavior and health.

Whereas activity of the biological stress system is essential for life, chronic or repeated elevations may have deleterious effects. Disturbances in the HPA axis are linked with impaired growth in children, disturbed immune functioning, altered memory and attentional processes, and altered fear circuits in the brain. Altered activity of this system is also associated with a variety of disorders—psychiatric, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular, among others ( De Kloet et al., 2005 ).

Because cortisol can be used in both experimental and naturalistic settings, it is studied in a wide variety of family research contexts, Kertes observed. For example, research has shown that cortisol reactivity to a psychosocial stressor differs in the presence of a personal friend or spouse ( Kirschbaum et al., 1995 ). Among girls exposed to maternal postnatal depression, basal cortisol levels at the transition to adolescence predicted future depressive symptoms ( Halligan et al., 2007 ). Children of an alcohol-abusing parent showed altered cortisol reactivity in ways that are consistent with disturbances that predate alcohol dependence ( Lovallo, 2006 ).

Kertes described two studies that document effects of early life experiences on HPA axis activity to illustrate strategies and challenges of studying the biological stress system in family research. The first study described long-term effects of early life adversity on basal cortisol levels in children. This study involved measuring cortisol levels among internationally adopted children, many of whom came from orphanages or other types of institutional care in which there was little opportunity to form relationships with stable caregivers ( Kertes et al., 2008 ). Severe relationship deprivation early in life is known to lead to a pattern of growth delay in which linear growth (i.e., height) is primarily affected. This study showed that deprived care severe enough to impact children's linear growth predicted subtle alterations in basal cortisol levels years after adoption into low-stress homes. Elevated cortisol levels were most evident in the early morning, at the peak of the diurnal rhythm, with no effect of deprivation-induced growth delay on cortisol levels observed at bedtime.

A second study described cortisol reactivity to a variety of novel social and nonsocial events among typically developing preschool-age children. This study tested a potential buffering effect of parenting quality on young children's HPA axis reactivity ( Kertes et al., 2009 ). There was evidence that children showed heightened cortisol reactivity to social or nonsocial challenges if they had a temperamental (behavioral) vulnerability to reacting to these types of events with fear and inhibition. For children very fearful of social interactions, having a sensitive, responsive parent—even though the parent was not present—buffered their biological responses to novel social events.

Whereas these studies document the impact of early experiences on children's HPA axis activity, they also illustrate some of the challenges of detecting effects in biomarker data. It is actually quite difficult to elicit a biological stress response among children in an experimental context, Kertes pointed out. Ethical constraints limit the intensity of stressors that can be used, and experiments are terminated if a participant exhibits distress. One immediate and pragmatic solution is to target research questions aimed at identifying subgroups of individuals for whom particular kinds of stressors are likely to elicit a biological stress response. The study of typically developing children described above illustrates this point. In that study Kertes et al. (2009) subjected 4-year-olds to a battery of mildly stressful events, including being separated from the parent, interacting with an experimenter that included some body contact, being asked to interact with strange, novel objects, and being approached in a conversation by a stranger. There was no evidence for an overall HPA axis activation among most children to this series of events. Rather, some children showed stressor-specific biological responses that directly related to their individual temperamental vulnerabilities. Children high in social fear showed biological stress responses to the social challenges but not nonsocial ones, and the opposite was true for children high in nonsocial fear. Thus, said Kertes, research questions can be tailored to detect stress responses within the ethical constraints of mimicking children's everyday experiences.

“Targeted research questions are a pragmatic but limited solution,” said Kertes. The inherent challenge of ethically eliciting a stress response in children has resulted in the development of a large number of protocols with limited or varied effectiveness. Protocols that activate the biological stress response system that are both effective and ethical for use with children or across the developmental spectrum are particularly lacking. Basic science research is needed for standard methods of eliciting and assessing stress responses in research with children and families, with attention to the factors that most consistently elicit a biological stress response (for a discussion, see Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004 ; Gunnar et al., 2009 ).

Detecting associations between life experiences and biological measures is further challenged by the varied factors that impact the activity of biological systems. Cortisol levels, for example, are affected by digestion, sleep, exercise, systemic stressors (such as inflammation or pain), caffeine, alcohol, tobacco, endogenously regulated basal activity, and perceived or actual psychosocial stress. Typically, researchers interested in psychosocial influences impose sampling constraints (e.g., on food or drink consumption or sampling days) to minimize the impact of these factors. However, there may be physical or psychosocial stressors specific to certain populations or age groups that may confound results. For example, in grade-school children (particularly boys), cortisol levels differ on days that children participate in structured extracurricular activities like sports, compared with days when they are just in and around the home ( Kertes and Gunnar, 2004 ). “This cautions us against erroneously attributing differences in children's cortisol to some other variable if we don't assess or control for it,” Kertes said. In the study described earlier on internationally adopted children ( Kertes et al., 2008 ), elevated evening cortisol levels previously reported among this population were not apparent when sampling was restricted to exclude days that children participated in sports.

Since limiting sampling for every possible known and unknown confound is impractical, another strategy is to refine statistical methods to disentangle variance that is stable in individuals or is due to some predictor of interest. For example, a structural equation modeling technique termed latent state trait modeling distinguishes variance in a phenotype that is due to stable, trait-like factors from the variance due to situational or state factors. As applied to basal cortisol data, approximately half of the variance in children's cortisol can be explained by trait factors at both the peak and the nadir of the diurnal cycle ( Kertes and van Dulmen, 2010 ). “This method might potentially allow us to improve our ability to detect subtle relations between environmental or behavioral factors and the stable trait-like component of cortisol in individuals while parceling out other factors that affect day-to-day fluctuations.”

Refining methods that facilitate the detection of family effects on HPA axis activity is likely to be of growing interest because of the impact of HPA axis activity on emotional and physical health. However, methodological innovation and statistical advances to facilitate analysis of environment-behavior-biological relations need to focus on the array of biological measures of interest to family research. At the physiological level, these include activity of the sympathetic adrenomedullary system, the immune system, and other steroids and peptide hormones as well as sleep disturbance/circadian rhythmicity and indices of brain functioning. All of these interact with the HPA axis in influencing behavioral and health outcomes. Advanced analytic techniques, refinement or standardization of protocols assessing momentary changes or basal activity, and growth of technologies capturing long-term activity with minimally invasive procedures are needed to foster this work. These methodological advances would facilitate the study of family effects on biological changes that influence risk for physical and mental disorders.

Another important conceptual and methodological issue in stress research is that stress biomarkers are often not correlated highly or even at all with behavioral measures of stressful life events or perceived stress. “Researchers are often very frustrated when they start to collect stress biomarkers and discover this fact,” Kertes said. From a methodological perspective, part of the reason for this uncoupling may be measurement concerns with the behavioral measures themselves ( Monroe, 2008 ). Interactions with sex steroid or other peptide hormones may also play a role.

From a conceptual perspective, however, the uncoupling of behavioral and biological measures of stress to some degree is to be expected. When combined, they provide a more complete view of exposure and response. “Biological measures do not replace the need for behavioral measures,” she said. “Both help us to disentangle stressors or even the same stressor acting on the biological stress pathway in different ways. For example, poverty might impact children's cortisol via its effect on family stress, but it might also disrupt endocrine systems via the effects of environmental toxins. We need both levels of assessment to identify the mechanism of action.”

As Gilbert Gottlieb argued, events at various levels—environmental, behavioral, physiological, and genetic—constantly interact with one another in a multidirectional way over the life course. As applied to stress research, a stressor in the environment might elicit a change at the behavioral level ( Gottlieb, 1992 ). If it does not sufficiently meet the challenge, it may also elicit a change at the fast-acting physiological level (including the HPA axis). If the immediate physiological response does not meet the challenge, it in turn elicits a change at the genetic level—that is, in gene expression. This suggests that coping resources at one level may prevent a stressor from impacting the individual at other levels. The results from the cortisol study with preschoolers illustrate this point. The 4-year-old children who were behaviorally fearful of social challenges did not show cortisol elevations in response to those challenges if they had a history of exposure to sensitive, high-quality parenting. “This speaks to the need for multiple levels of analysis,” said Kertes.

Methodological advances that promote multilevel research are also needed because family effects on emotional and physical health have multiple modes of transmission. These include direct genetic effects and gene-environment interplay, changes in gene expression initiated by the HPA axis or epigenetic mechanisms, and direct cultural or social modes of transmission. Capturing the joint and interactive effects occurring via multiple modes of transmission will require both collaboration across disciplines and cross-training of individual researchers, Kertes said.

One major methodological challenge to integrating across multiple levels of analysis, particularly when bridging biological and behavioral data, is balancing the need for deep phenotyping of behavior and the environment with the need for sufficiently large sample sizes to detect interactions among the environment, behavior, and biology. This is particularly true for research involving genetics, in which the effect of any given genetic variant is small for complex traits. Although comprehensive genotypic and phenotypic assessment is ideal, another strategy is to balance these various priorities across a program of research rather than an individual research study. For example, HPA axis disturbances are believed to play a role in stress-related mental health problems, including alcohol dependence and major depression. Family and life stress may in part promote these biological changes and emergence of disorder, but genetic risks are also likely to be involved. Gene-identification studies with large sample sizes but limited phenotyping can identify potential genes of interest, such as those involved in neurotransmission or the biological stress response ( Kertes et al., 2011 ). Top candidates then can be integrated in studies with family, developmental, and/or physiological data to ask meaningful questions about the interplay of genetic risks with psychosocial factors on behavioral or biological functioning.

Methodological development that supports integration across multiple levels of analysis has two key benefits. First, resolving the challenges inherent to integration across disciplines can fuel conceptual and methodological innovation in the disciplines from which they draw. Second, integration of biological data in family research has the potential to personalize preventive interventions, in which modifiable environmental conditions can buffer individuals' risks for poor outcomes in the face of biologically influenced vulnerabilities.

In sum, integration of physiological processes in family research is important because they serve as mechanisms by which family experiences impact an individual's response to future events as well as their emotional and physical well-being. Implementation, however, requires careful attention to methodology, and challenges remain. Nevertheless, because family effects are transmitted through physiological and genetic routes as well as through social and cultural routes, multiple levels of analysis are needed to adequately capture the effects of family life on individual behavioral and health outcomes.

- INSIDE FAMILY LIFE: MULTIPLE LAYERS OF INFLUENCE ON CHILDREN'S HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

Children's health is rarely if ever the result of a single factor, said Barbara Fiese, professor of human development and family studies and director of the Family Resiliency Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It is embedded in a familial, social, and cultural context that changes over time, including parents' beliefs and practices, neighborhoods, and access to health care, among others. Even something as straightforward as feeding a child becomes subject to the effects of income, media, and peers as a child grows up.

Many daily activities support the health of children, including routines created to support eating, sleeping, and physical activity. More broadly, family health is sustained through planning, open and direct communication, a sense of order and routines, and a belief that challenges in everyday life are manageable ( Fiese, 2006 ). Family health is compromised when planning is absent or thwarted, routines are disrupted, communication is strained, and everyday life challenges consume personal energy.

Multiple factors can be combined in a cumulative risk model to predict childhood health problems. These factors include such things as poverty, parents' perceptions of discrimination, neighborhood factors, and cultural stress. However, these factors do not reveal much about what happens in a family over time. Also, the focus on a single disease state does not reflect what often happens in real life.

Fiese described several studies involving family life and asthma. The studies were conducted in upstate New York and in Denver, Colorado. They involved approximately 400 Hispanic, black, and white families with a child between ages 5 and 12 with persistent asthma. About 58 percent of the families had two or more adults in the household, and 30 percent of the mothers had a high school education or less.

Asthma is the most common chronic illness of childhood. In any given classroom, 1 child in 10 is likely to have a diagnosis of persistent asthma. It is an expensive disease to treat, but it is treatable. Comorbidities include anxiety, sleep disturbances, and overweight conditions.

The household routines needed to manage asthma include taking medication twice a day, avoiding such environmental allergens as tobacco smoke and pet allergens, engaging in daily physical activity, and getting a good night's sleep. At the same time, families with asthmatic children have to juggle home and work life, they move and experience job loss, they have babies and get divorced, they have to care for their elders, they experience domestic violence, they have psychiatric illnesses and suicidal ideation, they are involved in gang killings, and sometimes their children die. “All of these experiences have happened to members of the families in our studies,” she said.

Fiese examined three questions during her presentation:

- Are routines associated with children's health and well-being?

- Are different aspects of routines associated with different health outcomes?

- How can the study of household routines inform the study of health comorbidities?

Lung functioning was ascertained through spirometry tests. The study also gathered parent and child reports of functional severity, such as how much the child was wheezing and coughing or waking up in the middle of the night. Daily diary reports included information on nighttime waking. The quality of life of the child and the parent were measured through such factors as how activities were disrupted by symptoms. Comorbidities, such as anxiety symptoms of the child, were ascertained through a structured diagnostic interview, and the study also looked at obesity.

Routines were measured through self-reports, semistructured interviews, questionnaires, and videotapes of family mealtimes. The families ranged considerably in terms of their level of organization and their commitment to routines.

The most basic routine was whether a child had taken his or her medicine. Less than half of the children Fiese studied took their medicine as prescribed. Taking medication can be measured through recall, reports to physicians, or a computerized chip on the bottom of an inhaler that measures not only whether a child took the medicine, but whether it was taken appropriately.

A simple eight-item questionnaire measured the likelihood that parents have routines around taking medication and the amount of burden that they feel in carrying out these medication routines. Results showed that if families have such routines, children are more likely to take their medication ( Fiese et al., 2005 ). The factor most related to quality of life for both the caregiver and the child was whether caregivers reported these routines as burdensome. This was true both for caregivers and children. Children who reported that they worry more about their symptoms and that their symptoms get in the way of having a relatively normal life were more likely to have parents who reported that carrying out routines was difficult.

To examine sleep patterns, the researchers conducted telephone diaries. They called the parents three times during the week and once on the weekend during selected times over the course of a year, gathering a collection of about 500 observations. They looked at four things in collecting the telephone diaries: (1) whether a parent had a negative mood that day, (2) whether a parent was hassled by kids not listening, (3) whether a parent was hassled because plans had to be changed, and (4) whether a disruption occurred in their bedtime routines. Each of these factors was significant in predicting the likelihood that the child would wake up at night ( Fiese et al., 2007 ). The elevated likelihood is not overwhelming, although it is statistically significant. But it is as large as the odds ratios for biological indicators for nighttime waking in response to environmental allergens (such as cockroaches, dust mites, cats).

The researchers also constructed an asthma impact interview to understand how this condition affects family life. In an open-ended interview format, they asked families to tell the story of when their child was diagnosed with asthma and how it affected the child and family life. “We don't want to hear the story they tell their pediatrician. We want to hear the story that they would tell a neighbor over a cup of coffee. Usually what we get at this point is what we call the head nodding response. Parents say, ‘We know which story you want to hear.’”

The researchers have identified three categories of ways in which families manage asthma in their daily life: reactive care, coordinated care, and family partnership. In the reactive category, anxiety leads the family to action. The family has not established clear and consistent strategies. In the coordinated care category, a single way to handle all situations has been identified. Typically one or two people are responsible for carrying out doctor's orders. In the family partnership category, plans are based on multiple sources of information and a shared philosophy, and multiple family members are involved in planning.

These different strategies predicted emergency room use one year after the interview was conducted ( Fiese and Wamboldt, 2003 ). Families in the reactive category were about four times more likely to use emergency room care for their children's symptoms than families in the coordinated care category and eight times more likely than those in the family partnership category. Families that have less burden in carrying out daily routines and have better medical adherence were less likely to use emergency room care, and they had better quality of life overall for both children and caregivers.

One common comorbid feature of asthma is separation anxiety. When people are anxious or panicked, they can have trouble breathing, and children with asthma are almost three times more likely to have separation anxiety symptoms than those without asthma. Fiese and her colleagues hypothesized that the way in which families interact with each other on a daily basis may mediate this relationship. They looked at interactions during meals, providing a basis for measuring such factors as communication and involvement of parents in children's lives. They found that families that were able to be responsive during mealtimes, show genuine concern about their child's daily activities, and manage affect in a positive way were less likely to have children with separation anxiety symptoms ( Fiese et al., 2010 ). In contrast, families who have a child with separation anxiety symptoms have more difficulty getting tasks done during mealtimes, have more problems managing affect, and are less involved with their children.

They found the same relationship when looking at obesity in children ( Jacobs and Fiese, 2007 ). Families that were more organized, regularly managed affect, assigned roles, and showed genuine concern about their children's activities were less likely to have overweight children. The researchers also made mealtime observations on a second-by-second basis—”which we are calling our DNA prototype of family mealtime”— looking at activity levels, behavior management, and communication, expressed by every family member during a meal. They found that time spent at the meal distinguished families that have a child of healthy weight versus overweight. Children who are overweight spent less time at meals. When these observations were put into a cumulative risk model that included census tract data, poverty, communication, time spent at the meal, and the scheduling and importance of mealtime, the model demonstrated associations between risk factors and a child's body mass index and nighttime waking.

Fiese and her colleagues are now translating this work into interventions to promote the relationship between medical adherence and family routines. Targets of the intervention include quality of life, lung functioning, weight status, behavior problems, and health care utilization. For example, public service announcements around the topic of “mealtime minutes” remind families of the importance of mealtime routines, interactions, and time.

This research poses several methodological challenges, Fiese observed. The resources to transcribe, code, and analyze observations and narratives can be in short supply. There can be important differences among families across cultures, socioeconomic status, and life stage. It also can be difficult to capture differences among ages, which is especially challenging with large families. Family size is not necessarily static, with multiple players in a family, including neighbors, cousins, uncles, aunts, grandparents, and babysitters. Disease status may not be clear, and more attention needs to be devoted to comorbidities.

- ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVES ON UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF FAMILIES ON CHILD WELL-BEING

One recent example of multidisciplinarity in family science is the increased attention across disciplines to causal inference in estimating family influences. Approaches from economics to estimate unbiased causal estimates in research have been influential in other disciplines. To estimate causal effects using observational data, economists use four main approaches, said Betsey Stevenson of the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School.

The “first and easiest” thing is to apply a cross-sectional regression analysis, she said. This approach examines the differences among people and tries to identify the causal effects of a single difference while controlling for other differences. This approach has a major limitation because there are often unobserved differences among individuals or groups that interfere with isolating the effects of a single variable.

The second approach is to do a time-series analysis. This technique documents a correlation between variables of interest over time. It works particularly well if there are sharp changes in variables over time, such as a change in policy. However, many things can change at the same time, which is a limitation of this approach.

A third approach is what is called a quasi-experiment. This approach uses changes in the environment that create roughly identical treatment and control groups for studying the effects of that change. Quasi-experiments can provide estimates of the causal impacts of a particular treatment, but they are better at telling how outcomes change rather than why they change, which can create ambiguity in extending or applying an analysis.

The fourth approach is to use structural modeling. These models use the same data as a regression analysis, but they use theory to constrain the data in an effort to derive understanding from them. The limitations of this approach are that causal impacts can be difficult to estimate and the results are only as good as the theoretical assumptions contained in the model.

Stevenson illustrated two of these approaches—regression analysis and quasi-experiments—in her analysis of the effects of girls' participation in high school sports on years of schooling completed ( Stevenson, 2010 ). (Her research on Title IX examines, in addition to education, labor force participation, wages, and occupational choice, but for the purposes of the example she limited her discussion to years of education completed.) Students who participate in sports complete more years of schooling. The relevant questions are whether the correlation between sports and schooling is because of the types of people who choose to play sports or whether this is something that occurs because of sports. Answering this question is necessary to consider whether increasing the opportunities for students to play sports would increase their educational attainments.

Stevenson started with data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), which has been tracking a cohort of more than 12,000 young people who were between the ages of 14 and 22 in 1979, when they were first interviewed. Her regression analysis included a wide range of independent variables, including personal characteristics, like race, age, IQ, and self-confidence; family characteristics, such as parents' education and family income; community characteristics; and school characteristics. Some of these independent factors are easier to measure than others, and the ones that cannot be measured can cause bias in the causal estimates if they are correlated with the variable of interest.

After controlling for the race and age of students along with state and urban status, the regression analysis shows that girls who participate in sports acquire about a year's more education than girls who do not. “That is huge,” Stevenson said. “If we thought that was a causal effect, you should all run out of this room and start sponsoring sports programs.” The effect is about the same for boys who participate in high school sports.

However, as more independent variables are added as controls, the size of the effect shrinks. Adding family characteristics and school characteristics cuts the estimated years of additional education by about a third. Adding student ability and achievement measures, such as student IQ, cuts the effect another third, so that it is now less than half a year. “It turns out smarter kids play sports. For those of you who thought of the dumb jock, that is not true. Smarter kids play sports, smarter kids get more education. Without controlling for IQ, I get big estimates. When I control for IQ they shrink, and now they are at about 0.4 of a year's schooling.”

Nevertheless, the effects of participating in high school sports never shrink to zero as more and more controls are added. “Every cross sectional regression that has been run, no matter what you control for, you see that kids who participate in sports do better than kids who don't.”

The question remains whether students who participate in sports are different in ways that cannot be determined from the available data. For example, perhaps those who participate in sports are the type of people who would have stayed in school longer because of an unmeasured factor, such as ambition or energy, that is not contained in the control variables. All possible source of bias cannot be eliminated. But another source of information on the effects of sports on education is available: the quasi-experiment afforded by the passage of Title IX in 1972.

Title IX of the Education Amendments to the 1964 Civil Rights Act declared that “no person in the United Sates shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving financial assistance.” It requires that girls be given the same opportunities to participate in sport at boys. “It doesn't mean equal participation rates, but it does mean that if a girl wants to play and there are boys who are able to play, then either you need to have equal participation rates or you need to be able to make sure that girl can play.”

Title IX led to a major increase in girls participating in sports. Prior to Title IX, less than 5 percent of girls played high school sports compared with 50 percent of boys. After Title IX, about 30 percent of girls played high school sports and about 50 percent of boys did.

While this changes yields some potentially useful time-series evidence, the useful quasi-experiment comes from exploiting differences across states over time. Differences across states emerge because the percentage of boys who participate in high school sports varies widely by state. In states where boys' participation is high, more girls need to be given opportunities to participate in sports to be in compliance with Title IX.

By analyzing the change in girls' sporting opportunities generated by the interaction of the passage of Title IX and the variation across states in boys' pre-Title IX sports participation rates, Stevenson was able to assess whether girls' outcomes related to education were changed in a way that is related to the growth in sporting opportunities generated by Title IX (and in particular, in a way predicted by the preexisting level of boys' participation). The quasi-experimental approach is to identify a treated and untreated cohort. The treated cohort were those attending high school after Title IX went into effect in 1978, and the untreated cohort were those finishing high school before Title IX passed in 1972.

Combining differences across generations with the differences across states creates what economists call a “differences-in-differences” estimator. It combines time-series and cross-sectional analysis in an experimental setting, thereby controlling for cross-sectional differences and time-series differences, in which the cross-sectional differences are stable over time. It is still possible that some states increased girls' sports participation more than others because of other factors, such as a school board superintendent who worked very hard at it. But this can be controlled through what are called intention-to-treat or instrumental variables that isolate the exogenous part of the policy change.

This technique shows that female educational attainment rises with the opportunity to play sports. States with a 10 percentage point greater increase in the statewide female athletic participation rate had an overall increase in educational attainment of 0.039 years, an increase in the probability of some postsecondary education of 1.3 percentage points, and an increase of 0.8 percentage points in the probability of obtaining at least a college degree. Since Title IX raised female participation by around 30 percent, these results would be multiplied by more than three to get the aggregate effects. Meanwhile, female educational attainment rose by about 0.7 years over the time period being analyzed. As a result, Stevenson concluded that increases in sports participation caused by Title IX explain about 20 percent of the increase in women's education over the time period being analyzed. Similar analyses can be applied to the participation of women in the labor market and entrance into previously male-dominated jobs.

Documenting this effect does not mean that every girl should be forced to participate in sports, Stevenson observed. Some may benefit more from playing sports, and some may benefit less. Title IX, by increasing opportunities, allowed girls to self-select whether or not to participate. It remains to be known whether all girls would benefit from participating in sports.

During the discussion period, the presenters were asked how they would use an increase in research funding to extend their work. Barbara Fiese responded that she would integrate more sophisticated biological markers into her investigations. Such markers could be used with all of the members of a family to look at variations in the family unit over time. “I think that would be incredibly fascinating.”

Another enhancement would be to integrate the investigation with interventions and the response to interventions. It is difficult to do lengthy qualitative observations in intervention science, yet more narrative approaches can capture the richness in family situations.

A final addition would be integrate and translate research results into public arenas. For example, “how can we use this information to inform public service announcements, where we reach a broader audience, and how can we use this information to cast a wider net to communities at large?”

Darlene Kertes said that some of the issues in family research are similar for behavioral and biological measures. As with behavioral measures, attention needs to be paid to developing protocols that can be assessed longitudinally. A second point was that it is important to consider both data collection and consenting methods that are flexible and adaptable. It is difficult to predict what technologies might be available 10 years from now to analyze biological specimens. One challenge is therefore collecting biological specimens that allow for potential future use. Another is establishing best practices for consenting participants in a way that is ethical (particularly for minors) but allows for analyses to be conducted using knowledge and technologies that will be developed in the future.

Hirokazu Yoshikawa asked whether the projects that incorporated biological measures brought together people trained in specific methods or engaged in cross-training to combine the behavioral and the biological approaches. McMahon responded that his work has involved complementary studies proposed to different funders that historically have favored one kind of research over another. To carry out the work, he assembled a group of faculty with different areas of expertise. Although people were trained for each study, the quantitative methods were kept separate from the qualitative methods.

Fiese said that her research has had one team work on the narrative coding, one team work on the observational coding, and one team work on structured interviews. “But I am leaning more toward trying to integrate some of the training within individuals so that they can be a little more flexible because I am seeing this as an added value in their future careers.”

- Cite this Page Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee on the Science of Research on Families; Olson S, editor. Toward an Integrated Science of Research on Families: Workshop Report. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. 5, Family Research Methods and Frameworks: Examples from the Study of Biomarkers, Child Health, and Econometric Methods.

- PDF version of this title (1.4M)

In this Page

Other titles in this collection.

- The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health

Recent Activity

- Family Research Methods and Frameworks: Examples from the Study of Biomarkers, C... Family Research Methods and Frameworks: Examples from the Study of Biomarkers, Child Health, and Econometric Methods - Toward an Integrated Science of Research on Families

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Question: Types and Examples

The first step in any research project is framing the research question. It can be considered the core of any systematic investigation as the research outcomes are tied to asking the right questions. Thus, this primary interrogation point sets the pace for your research as it helps collect relevant and insightful information that ultimately influences your work.

Typically, the research question guides the stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting. Depending on the use of quantifiable or quantitative data, research questions are broadly categorized into quantitative or qualitative research questions. Both types of research questions can be used independently or together, considering the overall focus and objectives of your research.

What is a research question?

A research question is a clear, focused, concise, and arguable question on which your research and writing are centered. 1 It states various aspects of the study, including the population and variables to be studied and the problem the study addresses. These questions also set the boundaries of the study, ensuring cohesion.

Designing the research question is a dynamic process where the researcher can change or refine the research question as they review related literature and develop a framework for the study. Depending on the scale of your research, the study can include single or multiple research questions.

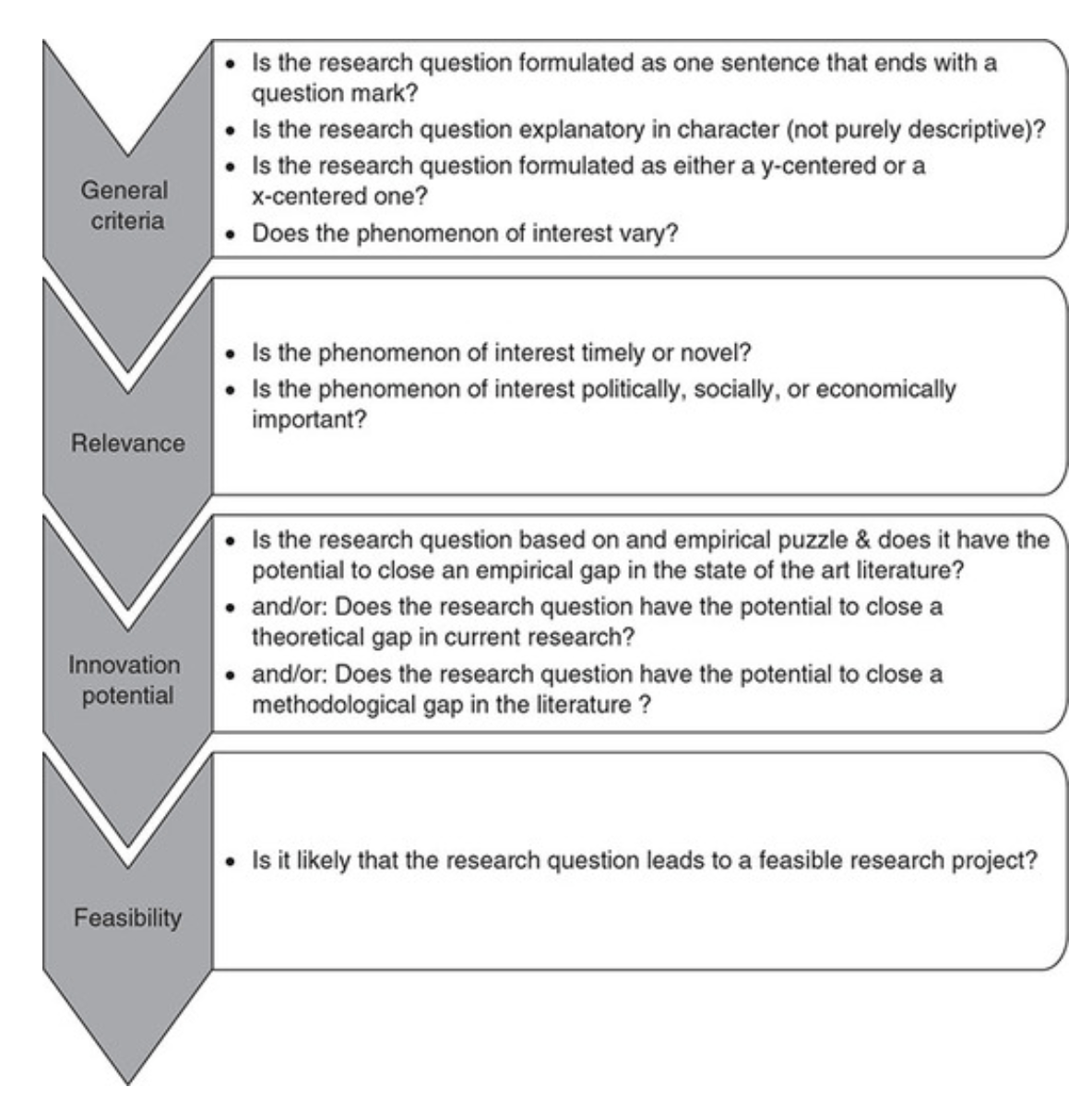

A good research question has the following features:

- It is relevant to the chosen field of study.

- The question posed is arguable and open for debate, requiring synthesizing and analysis of ideas.

- It is focused and concisely framed.

- A feasible solution is possible within the given practical constraint and timeframe.

A poorly formulated research question poses several risks. 1

- Researchers can adopt an erroneous design.

- It can create confusion and hinder the thought process, including developing a clear protocol.

- It can jeopardize publication efforts.

- It causes difficulty in determining the relevance of the study findings.

- It causes difficulty in whether the study fulfils the inclusion criteria for systematic review and meta-analysis. This creates challenges in determining whether additional studies or data collection is needed to answer the question.

- Readers may fail to understand the objective of the study. This reduces the likelihood of the study being cited by others.

Now that you know “What is a research question?”, let’s look at the different types of research questions.

Types of research questions

Depending on the type of research to be done, research questions can be classified broadly into quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies. Knowing the type of research helps determine the best type of research question that reflects the direction and epistemological underpinnings of your research.

The structure and wording of quantitative 2 and qualitative research 3 questions differ significantly. The quantitative study looks at causal relationships, whereas the qualitative study aims at exploring a phenomenon.

- Quantitative research questions:

- Seeks to investigate social, familial, or educational experiences or processes in a particular context and/or location.

- Answers ‘how,’ ‘what,’ or ‘why’ questions.

- Investigates connections, relations, or comparisons between independent and dependent variables.

Quantitative research questions can be further categorized into descriptive, comparative, and relationship, as explained in the Table below.

- Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional, and more flexible. It concerns broad areas of research or more specific areas of study to discover, explain, or explore a phenomenon. These are further classified as follows:

- Mixed-methods studies

Mixed-methods studies use both quantitative and qualitative research questions to answer your research question. Mixed methods provide a complete picture than standalone quantitative or qualitative research, as it integrates the benefits of both methods. Mixed methods research is often used in multidisciplinary settings and complex situational or societal research, especially in the behavioral, health, and social science fields.

What makes a good research question

A good research question should be clear and focused to guide your research. It should synthesize multiple sources to present your unique argument, and should ideally be something that you are interested in. But avoid questions that can be answered in a few factual statements. The following are the main attributes of a good research question.

- Specific: The research question should not be a fishing expedition performed in the hopes that some new information will be found that will benefit the researcher. The central research question should work with your research problem to keep your work focused. If using multiple questions, they should all tie back to the central aim.

- Measurable: The research question must be answerable using quantitative and/or qualitative data or from scholarly sources to develop your research question. If such data is impossible to access, it is better to rethink your question.

- Attainable: Ensure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific.

- You have the expertise

- You have the equipment and resources

- Realistic: Developing your research question should be based on initial reading about your topic. It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline.

- Based on some sort of rational physics

- Can be done in a reasonable time frame

- Timely: The research question should contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on.

- Novel

- Based on current technologies.

- Important to answer current problems or concerns.

- Lead to new directions.

- Important: Your question should have some aspect of originality. Incremental research is as important as exploring disruptive technologies. For example, you can focus on a specific location or explore a new angle.

- Meaningful whether the answer is “Yes” or “No.” Closed-ended, yes/no questions are too simple to work as good research questions. Such questions do not provide enough scope for robust investigation and discussion. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation before providing an answer.

Steps for developing a good research question

The importance of research questions cannot be understated. When drafting a research question, use the following frameworks to guide the components of your question to ease the process. 4

- Determine the requirements: Before constructing a good research question, set your research requirements. What is the purpose? Is it descriptive, comparative, or explorative research? Determining the research aim will help you choose the most appropriate topic and word your question appropriately.

- Select a broad research topic: Identify a broader subject area of interest that requires investigation. Techniques such as brainstorming or concept mapping can help identify relevant connections and themes within a broad research topic. For example, how to learn and help students learn.

- Perform preliminary investigation: Preliminary research is needed to obtain up-to-date and relevant knowledge on your topic. It also helps identify issues currently being discussed from which information gaps can be identified.

- Narrow your focus: Narrow the scope and focus of your research to a specific niche. This involves focusing on gaps in existing knowledge or recent literature or extending or complementing the findings of existing literature. Another approach involves constructing strong research questions that challenge your views or knowledge of the area of study (Example: Is learning consistent with the existing learning theory and research).

- Identify the research problem: Once the research question has been framed, one should evaluate it. This is to realize the importance of the research questions and if there is a need for more revising (Example: How do your beliefs on learning theory and research impact your instructional practices).

How to write a research question

Those struggling to understand how to write a research question, these simple steps can help you simplify the process of writing a research question.

Sample Research Questions

The following are some bad and good research question examples

- Example 1

- Example 2

References:

- Thabane, L., Thomas, T., Ye, C., & Paul, J. (2009). Posing the research question: not so simple. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie , 56 (1), 71-79.

- Rutberg, S., & Bouikidis, C. D. (2018). Focusing on the fundamentals: A simplistic differentiation between qualitative and quantitative research. Nephrology Nursing Journal , 45 (2), 209-213.

- Kyngäs, H. (2020). Qualitative research and content analysis. The application of content analysis in nursing science research , 3-11.

- Mattick, K., Johnston, J., & de la Croix, A. (2018). How to… write a good research question. The clinical teacher , 15 (2), 104-108.

- Fandino, W. (2019). Formulating a good research question: Pearls and pitfalls. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia , 63 (8), 611.

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP journal club , 123 (3), A12-A13

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the World of Research

Language and grammar rules for academic writing, you may also like, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , 9 steps to publish a research paper, what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, 6 tips for post-doc researchers to take their..., presenting research data effectively through tables and figures, ethics in science: importance, principles & guidelines , jenni ai review: top features, pricing, and alternatives.

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Primary research questions.

Broadly speaking, our research is aimed at understanding how couple and family relationships ameliorate or perpetuate depression, anxiety, and related indicators of health (e.g., alcohol use, sleep dysfunction, poor diet). Our work is largely focused on couple relationships, investigating how multiple relationship processes (e.g., humanization and respect, support, closeness and intimacy, sexual satisfaction, conflict management strategies) impact partners and their children. However, we also investigate larger family system processes (e.g., aspects of the parent-child relationship, coparenting dynamics) that contribute to health and well-being. We conduct research that has the translational goal of informing interventions that minimize family dysfunction, build healthy couple dynamics, and promote adult and child health throughout the lifespan. There are four primary lines of inquiry we are currently pursuing: