Charles Babbage

(1791-1871)

Charles Babbage was an English mathematician, philosopher and inventor born on December 26, 1791, in London, England. Often called “The Father of Computing,” Babbage detailed plans for mechanical Calculating Engines, Difference Engines, and Analytical Engines. Babbage died on October 18, 1871, in London.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Charles Babbage

- Birth Year: 1791

- Birth date: December 26, 1791

- Birth City: London

- Birth Country: England

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Charles Babbage was known for his contributions to the first mechanical computers, which laid the groundwork for more complex future designs.

- Technology and Engineering

- Business and Industry

- Education and Academia

- Internet/Computing

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- Trinity College, Cambridge

- Peterhouse, Cambridge

- Death Year: 1871

- Death date: October 18, 1871

- Death City: London

- Death Country: England

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Charles Babbage Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/inventors/charles-babbage

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: October 26, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous British People

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Christopher Nolan

Emily Blunt

Jane Goodall

Charles Babbage: The Pioneering Father of Computing

- by history tools

- November 19, 2023

Imagine a time without computers. Today, we take for granted how these revolutionary machines have transformed everything from science to business and commerce. But their origins can be traced back to the pioneering work of a 19th century English mathematician and inventor named Charles Babbage. Often called the "father of computing", his ingenious mechanical computers were the first automatic calculation machines – the precursors to modern electronic digital computers that you and I rely on today.

Babbage overcame many challenges during his lifetime to design and build devices that were far ahead of his time. Powered by steam, his complex Analytical Engine contained many key elements of a real programmable computer. From his earliest Difference Engine to handle polynomial equations to the multifunctional Analytical Engine capable of any arithmetical operation, Babbage planted the seeds that blossomed into the age of computing.

Let‘s take a closer look at the remarkable life and inventions of the trailblazing innovator who helped launch the computer revolution.

Overcoming Adversity in Early Life

Born in 1791 in London, England, Charles Babbage grew up in a life of privilege as the son of a wealthy banker. Tragically, his father passed away when Charles was just eight years old, causing the family to spiral into financial hardship. As a child, Babbage disliked his classical schooling, preferring to tinker with tools instead of studying Latin and Greek.

After his father‘s death, Babbage transferred to a country academy. There, he suffered cruelty from older boys who would beat him for sporting his typically fancy clothes. Overcoming these early challenges instilled in Babbage a grit and resilience that served him well as an innovator later in life.

In 1810, Babbage enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge. Though he did not excel academically, he soaked up new ideas, co-founding a society to introduce modern algebra to England. After graduating in 1814, he lectured at the Royal Institution on astronomy and mathematics. By age 25, Babbage was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, hinting at the greatness to come.

Conceiving the Difference Engine

As a mathematician, Babbage was frustrated by the time-consuming process of generating mathematical tables by hand calculation. Such tables were critical for navigation, science, and engineering, but mistakes often crept in during manual preparation.

In 1822, Babbage proposed a steam-powered calculating machine called the Difference Engine to automatically tabulate polynomial functions. This prototype mechanical computer aimed to calculate using the method of finite differences, avoiding human error in tables used for vital fields like shipbuilding and railways.

The British government initially funded development of the project but later withdrew support. While the unfinished Difference Engine proved too complex to build with available manufacturing methods, it cemented Babbage‘s vision for calculating machines.

The Revolutionary Analytical Engine

Undeterred by the setback, Babbage worked tirelessly to refine his designs throughout the 1820s and 1830s. By 1834, he conceived his most revolutionary invention – the Analytical Engine.

This machine represented a giant leap forward, incorporating major innovations like:

- Sequential program control – Allowing automated, sequential operations controlled by a "store" of data and instructions

- Memory storage – Thousands of numbers could be held in the Engine‘s "store"

- Arithmetical unit – To perform calculations

- Punch cards – For inputting instructions and data

The Analytical Engine was essentially a general purpose, fully programmable mechanical computer. Its design contained the key elements of a real modern computer as you know it – input, memory, processor, and output.

Table: Comparing the Difference and Analytical Engines

Unfortunately, fabrication of the elaborate Analytical Engine also proved beyond 19th century engineering capabilities. But the blueprint was complete for the first general purpose computer.

Partnership with Ada Lovelace – Programming Pioneer

Babbage collaborated with an unlikely partner in pioneering computer programming – Ada Lovelace, daughter of famous poet Lord Byron. Lovelace took keen interest in Babbage‘s Engines. In 1842, she translated an Italian mathematician‘s paper on the Analytical Engine into English.

Lovelace‘s translation contained extensive, original notes detailing how codes could symbolically represent more than just numbers. She described how the machine could compose music, produce graphics, and complete many tasks beyond calculation. Her notes included the first published computer program – an algorithm for the Analytical Engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers.

Though the Analytical Engine was never built, Lovelace correctly predicted its potential impact, writing:

"[The Analytical Engine] weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves."

This genius woman mathematician was history‘s first computer programmer – and a fitting partner to Babbage in ushering in modern computing.

Lasting Legacy as Computing Pioneer

Frustrated at being unable to build his wondrous Engines, Charles Babbage died in 1871 in London, never gaining the wealth or acclaim he deserved during his lifetime. But future generations would come to appreciate his genius.

Babbage‘s mechanical computer designs were visionary – conceived at a time when electricity itself was still in its infancy. The concepts he introduced predated electronics by over a century: automatic, programmed computation with memory storage. These breakthroughs provided the conceptual blueprint for modern programmable computers.

In the 1990s, London‘s Science Museum successfully built a working Difference Engine based on Babbage‘s designs, vindicating his mechanical computing concepts. While he did not invent the first complete digital computer, Charles Babbage‘s pioneering work earned him rightful status as the "father of computing" – lighting the spark that led to today‘s computer revolution.

Related posts:

- Peter Thiel: The Visionary Silicon Valley Billionaire

- John Patterson — Complete Biography, History and Inventions

- Hello There! Let‘s Explore How Jabez Burns‘ Addometer Paved the Way for Modern Computing

- Percy Ludgate – Complete Biography, History, and Inventions

- Samuel Kelso: Complete Biography, History, and Inventions

- Elizur Wright: The Father of Life Insurance Reform

- Friedrich Kaufmann and the Trumpet Player: A Complete History

- The Innovative Journey of YouTube Co-Founder Chad Hurley

Biography Online

Charles Babbage Biography

Charles Babbage (26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who developed the concept of a programmable computer.

“The whole of arithmetic now appeared within the grasp of mechanism.”

– Charles Babbage, (1864) Passages from the Life of a Philosopher , ch. 8 of the Analytical Engine

At Cambridge, he was dissappointed by the quality of the maths teaching, but joined the Analytical Society – a group of like minded students, interested in exploring issues of mathematics. It was as a student that he conceived of an idea to try and do calculations with a machine. It was after looking at a table for logarithms, (many of which were wrong) that he thought it would be better to try and work them out systematically.

“Mr. Herschel … brought with him the calculations of the computers, and we commenced the tedious process of verification. After a time many discrepancies occurred, and at one point these discordances were so numerous that I exclaimed, “I wish to God these calculations had been executed by steam,” to which Herschel replied, “It is quite possible.”

– Charles Babbage (1821) on seeing errors in maths tables. (computers here means people who do computations) Quoted in Harry Wilmot Buxton and Anthony Hyman (1988), Memoir of the Life and Labours of the Late Charles Babbage .

In 1822, he began working on his ‘difference engine’ that sought to mechanically compute calculations. Like many of Babbage’s machines, they were never brought to completion. This was partly because of his personality, and also because his funding often dried up. He wasn’t always the best communicator of his ideas, and he could be dismissive of the very people who were funding him. There was often a frosty relationship between Babbage and those he was trying to impress.

“On two occasions I have been asked,—”Pray, Mr. Babbage, if you put into the machine wrong figures, will the right answers come out?” In one case a member of the Upper, and in the other a member of the Lower, House put this question. I am not able rightly to apprehend the kind of confusion of ideas that could provoke such a question.”

Babbage (1864), Passages from the Life of a Philosopher , ch. 5 “Difference Engine No. 1”

In 1824, Babbage won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“for his invention of an engine for calculating mathematical and astronomical tables”.

However, he generally disliked honours, and he refused a knighthood and baronetcy.

After graduation, he worked as a maths lecturer at Cambridge. He was also employed by the government to build a programmable computer. He received substantial funding, but eventually, the government despaired of seeing a finished product and withdrew funding. Many of his nearly finished models were melted down for scrap, but he is seen as a very important inventor, for showing the possibilities available to mechanical computing. He is now considered to be the “Father of Computers”.

Babbage definitely had some foresight that computers could radically change the way calculations were done. An optimism not always shared by other people of his generation.

“As soon as an Analytical Engine exists, it will necessarily guide the future course of the science. Whenever any result is sought by its aid, the question will then arise — by what course of calculation can these results be arrived at by the machine in the shortest time?”

Babbage (1864) Passages from the Life of a Philosopher , ch. 8 “Of the Analytical Engine.”

Apart from computers, he contributed other inventions – such as a pilot or ‘cow catcher’ to be put on the front of engines to catch obstacles on railways. These were widely used in America. At various times, he worked for Brunel’s Great Western Railways.

Babbage married Georgiana Whitmore in 1814. The couple had eight children, of which only four survived childhood. Babbage died in 1871 at the age of 79.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Charles Babbage” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net 13th May 2012. Last updated 1 March 2018.

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage at Amazon.com

Charles Babbage at Amazon.co.uk

Related pages

- Machines that changed the world

- Top 10 innovators

- Wiki Quote – Charles Babbage

One Comment

babage is the computer father and also big man in the world

- November 01, 2018 5:02 AM

- By dipak singh

- Collections

- Publications

- K-12 Students & Educators

- Families & Community Groups

- Colleges & Universities

- Business & Government Leaders

- Make a Plan

- Exhibits at the Museum

- Tours & Group Reservations

- Customize It

- This is CHM

- Ways to Give

- Donor Recognition

- Institutional Partnerships

- Upcoming Events

- Hours & Directions

- Subscribe Now

Charles Babbage

Another age must be the judge. 1837

Vital Statistics

Charles Babbage (1791-1871) was born in Walworth, Surrey, on December 26, 1791. He was one of four children born to the banker Benjamin Babbage and Elizabeth Teape. He attended Trinity, Cambridge, in 1810 to study mathematics, graduated without honors from Peterhouse in 1814 and received an MA in 1817. In 1814 he married Georgiana Whitmore with whom he had eight children, only three of whom lived to adulthood. The couple made their home in London off Portland Place in 1815. His wife, father, and two of his children died in 1827. In 1828 Babbage moved to 1 Dorset Street, Marylebone, which remained his home till his death in 1871. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1816 and occupied the Lucasian chair of mathematics at Cambridge University from 1828 to 1839. He died on October 18, 1871 and was buried at Kensal Green cemetery in London.

Gentleman of Science

Science was not an established profession, and Babbage, like many of his contemporaries, was a 'gentleman scientist' - an independently wealthy amateur well able to support his interests from his own means. The scope of Babbage's interests was polymathically wide even by the generous standards of the day. Between 1813 and 1868 he published six full-length works and nearly ninety papers. He was a prolific inventor, mathematician, scientist, reforming critic of the scientific establishment and political economist. He pioneered lighthouse signalling, invented the ophthalmoscope, proposed 'black box' recorders for monitoring the conditions preceding railway catastrophes, advocated decimal currency, proposed the use of tidal power once coal reserves were exhausted, designed a cow-catcher for the front end of railway locomotives, failsafe quick release couplings for railway carriages, multi-colored theatre lighting, an altimeter, a seismic detector, a tugboat for winching vessels upstream, a 'hydrofoil' and an arcade game for members of the public to challenge in a game of tic-tac-toe. His interests included lock picking, ciphers, chess, submarine propulsion, armaments, and diving bells. Babbage was a prominent figure, regarded as colorfully controversial and even eccentric at home in England, yet feted with honors by Continental academies. He ached for recognition and was aggrieved at its lack grumbling that the Lucasian chair of mathematics at Cambridge, was the only honor bestowed on him by his country.

Personal Life

Babbage married Georgiana Whitmore in 1814, against his father's wishes. The marriage was a very happy one. Tragedy struck in 1827. In the space of a year his father with whom he had had a troubled relationship, his second son (Charles), Georgiana and a newborn son all died. Babbage was inconsolable. Close to breakdown he went on an extended trip on the Continent. There was a further cruel blow. His daughter, Georgiana, on whom he doted, died while still in her teens sometime around 1834. Babbage immersed himself in work. On his father's death he inherited an estate valued at £100,000, a sizeable fortune - somewhere between $6 and $30 million dollars in today's terms. He never remarried.

In the 1830s Babbage was a lion of the London social scene. His Saturday soirees were sparkling events in the London social calendar, and his house in Dorset Street was a hub of social and intellectual life. Celebrities, civil dignitaries, authors, actors, scientists, bishops, bankers, politicians, industrialists and socialites converged for gossip, intrigue, and the latest in science, literature, philosophy and art. 'All were eager to go to his glorious soirees' wrote Harriet Martineau, writer and philosopher. Babbage was also a sought-after dinner guest with a reputation for being a captivating raconteur. 'Mr. Babbage is coming to dinner' was a coup for any hostess.

The 'Irascible Genius'

Diplomacy was not Babbage's forte and his social and professional personas were at war. Proud and principled, he was capable of incontinent savagery in his public attacks on the scientific establishment, often beyond ordinary sensibility. He offended many whose support he needed behaving sometimes as though being right entitled him to be rude. The title of the first biography on his life was called 'Irascible Genius: A Life of Charles Babbage, Inventor'. The twin characteristics of irascibility and genius remain the defining signatures of his historical portrait.

In a prophetic passage written towards the end of his life Babbage affirmed his conviction in the value of his work.

If unwarned by my example, any man shall undertake and shall succeed in really constructing an engine ... upon different principles or by simpler mechanical means, I have no fear of leaving my reputation in his charge, for he alone will be fully able to appreciate the nature of my efforts and the value of their results.

MacTutor

Charles babbage.

Little is known of Mr Babbage's parentage and early youth except that he was born on 26 December 1792 .

Having suffered in health at the age of five years, and again at that of ten by violent fevers, from which I was with difficulty saved, I was sent into Devonshire and placed under the care of a clergyman ( who kept a school at Alphington, near Exeter ) , with instructions to attend to my health; but, not to press too much knowledge upon me: a mission which he faithfully accomplished.

Amongst these were Humphry Ditton's 'Fluxions', of which I could make nothing; Madame Agnesi 's 'Analytical Instructions' from which I acquired some knowledge; Woodhouse 's 'Principles of Analytic Calculation', from which I learned the notation of Leibniz ; and Lagrange 's 'Théorie des Fonctions'. I possessed also the 'Fluxions' of Maclaurin and of Simson .

Thus it happened that when I went to Cambridge I could work out such questions as the very moderate amount of mathematics which I then possessed admitted, with equal facility, in the dots of Newton , the d's of Leibniz , or the dashes of Lagrange . I thus acquired a distaste for the routine of the studies of the place, and devoured the papers of Euler and other mathematicians scattered through innumerable volumes of the academies of St Petersburg, Berlin, and Paris, which the libraries I had recourse to contained. Under these circumstances it was not surprising that I should perceive and be penetrated with the superior power of the notation of Leibniz .

I then drew up the sketch of a society to be instituted for translating the small work of Lacroix on the Differential and Integral Calculus. It proposed that we should have periodical meetings for the propagation of d's; and consigned to perdition all who supported the heresy of dots. It maintained that the work of Lacroix was so perfect that any comment was unnecessary.

It is a lamentable consideration, that that discovery which has most of any done honour to the genius of man, should nevertheless bring with it a train of reflections so little to the credit of his heart.

He did not compete for honours, believing Herschel sure of first place and not caring to come out second.

The Council of the Royal Society is a collection of men who elect each other to office and then dine together at the expense of this society to praise each other over wine and give each other medals.

... I was sitting in the rooms of the Analytical Society, at Cambridge, my head leaning forward on the table in a kind of dreamy mood, with a table of logarithms lying open before me. Another member, coming into the room, and seeing me half asleep, called out, Well, Babbage, what are you dreaming about?" to which I replied "I am thinking that all these tables" ( pointing to the logarithms ) "might be calculated by machinery."

Mr Babbage has displayed great talent and ingenuity in the construction of his machine for computation, which the committee thanks fully adequate to the attainment of the objects proposed by the inventory; and they consider Mr Babbage as highly deserving of public encouragement, in the prosecution of his arduous undertaking.

... six orders of differences, each of twenty places of figures, whilst the first three columns would each have had half a dozen additional figures.

Babbage had every reason to feel aggrieved about his treatment by successive governments. They had failed to understand the immense possibilities of his work, ignored the advice of the most reputable scientists and engineers, procrastinated for eight years before reaching a decision about the difference engine, misunderstood his motives and the sacrifices he had made, and ... failed to protect him from public slander and ridicule.

... all the variables to be operated upon, as well as all those quantities which had arisen from the results of other operations.

... into which the quantities about to be operated upon are always bought.

Every set of cards made for any formula will at any future time recalculate the formula with whatever constants may be required. Thus the Analytical Engine will possess a library of its own. Every set of cards once made will at any time reproduce the calculations for which it was first arranged.

... elaborations on the points made by Menabrea, together with some complicated programs of her own, the most complex of these being one to calculate the sequence of Bernoulli numbers .

The drawings of the Analytical Engine have been made entirely at my own cost: I instituted a long series of experiments for the purpose of reducing the expense of its construction to limits which might be within the means I could myself afford to supply. I am now resigned to the necessity of abstaining from its construction...

... if I survive some few years longer, the Analytical Engine will exist...

... to report upon the feasibility of the design, recorded their opinion that its successful realisation might mark an epoch in the history of computation equally memorable with that of the introduction of logarithms...

References ( show )

- N T Gridgeman, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography ( New York 1970 - 1990) . See THIS LINK .

- Biography in Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Babbage

- Obituary in The Times See THIS LINK

- C Babbage, Passages from the life of a philosopher ( London, 1864) .

- H P Babbage, Babbage's calculating emgines ( London, 1889) .

- H W Buxton, Memoir of the life and labours of the late Charles Babbage Esq. F.R.S. ( Los Angeles, CA, 1988) .

- J M Dubbey, The mathematical work of Charles Babbage ( Cambridge, 1978) .

- A Hyman, Charles Babbage : pioneer of the computer ( Oxford, 1982) .

- P Morrison and E Morrison, Charles Babbage and his calculating engines ( New York, 1961) .

- W J Ashworth, Memory, efficiency, and symbolic analysis : Charles Babbage, John Herschel, and the industrial mind, Isis 87 (4) (1996) , 629 - 653 .

- W J Ashworth, The calculating eye : Baily, Herschel, Babbage and the business of astronomy, British J. Hist. Sci. 27 (95) (4) (1994) , 409 - 441 .

- Babbage, Charles (1792 - 1871) , Dictionary of National Biography II ( London, 1885) , 304 - 306 . See THIS LINK .

- H W Becher, Woodhouse, Babbage, Peacock, and modern algebra, Historia Math. 7 (4) (1980) , 389 - 400 .

- A G Bromley, The evolution of Babbage's calculating engines, Ann. Hist. Comput. 9 (2) (1987) , 113 - 136 .

- A G Bromley, Charles Babbage's analytical engine, 1838 , Ann. Hist. Comput. 4 (3) (1982) , 196 - 217 .

- M Campbell-Kelly, Charles Babbage and the Assurance of Lives, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 16 (1994) , 5 - 14 .

- M Campbell-Kelly, Charles Babbage's table of logarithms (1827) , Ann. Hist. Comput. 10 (3) (1988) , 159 - 169 .

- Charles Babbage, The Times (23 Oct, 1871) .

- Charles Babbage, The Atheneum (28 Oct, 1871) .

- I B Cohen, Babbage and Aiken : with notes on Henry Babbage's gift to Harvard, and to other institutions, of a portion of his father's difference engine, Ann. Hist. Comput. 10 (3) (1988) , 171 - 193 .

- J M Dubbey, Babbage, Peacock and modern algebra, Historia Math. 4 (3) (1977) , 295 - 302 .

- M-J Durand-Richard, Charles Babbage (1791 - 1871) : de l'école algébrique anglaise à la 'machine analytique', Math. Inform. Sci. Humaines 118 (1992) , 5 - 31 .

- P J FitzPatrick, Leading British statisticians of the nineteenth century, Journal of the American Statistical Association 55 (1960) , 38 - 70 .

- P J FitzPatrick, Leading British statisticians of the nineteenth century, in M G Kendall and R L Plackett ( eds. ) , Studies in the History of Statistics and Probability II ( London, 1977) , 180 - 212 .

- O I Franksen, Babbage and cryptography : Or, the mystery of Admiral Beaufort's cipher, Math. Comput. Simulation 35 (4) (1993) , 327 - 367 .

- O Franksen, Immanuel Mr. Babbage, the difference engine, and the problem of notation: an account of the origin of recursiveness and conditionals in computer programming, Internat. J. Engrg. Sci. 19 (12) (1981) , 1657 - 1694 .

- I Grattan-Guinness, Charles Babbage as an algorithmic thinker, IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 14 (3) (1992) , 34 - 48 .

- I Grattan-Guinness, Babbage's mathematics in its time, British J. Hist. Sci. 12 (40) (1) (1979) , 82 - 88 .

- J D Hill, Charles Babbage, Rowland Hill and penny postage, Postal History International 2 (1) (1973) .

- V R Huskey and H D Huskey, Lady Lovelace and Charles Babbage, Ann. Hist. Comput. 2 (4) (1980) , 299 - 329 .

- D Lardner, Babbage's calculating engines, Edinburgh Review 59 (1834) , 263 - 327 .

- J Mosconi, Charles Babbage : vers une théorie du calcul mécanique, Rev. Histoire Sci. Appl. 36 (1) (1983) , 69 - 107 .

- H Nagler, Napier and Babbage, Ann. Hist. Comput. 2 (2) (1980) , 186 - 187 .

- D Nudds, Charles Babbage (1791 - 1871) , in Mid-nineteenth century scientists ( Oxford, 1969) , 1 - 34 .

- N K Taylor, Charles Babbage's mini-computer - Difference Engine No. 0 , Bull. Inst. Math. Appl. 28 (6 - 8) (1992) , 112 - 114 .

- G J Tee, More about Charles Babbage's difference engine no. 0 , Bull. Inst. Math. Appl. 30 (9 - 10) (1994) , 134 - 137 .

- G J Tee, Charles Babbage (1791 - 1871) and his New Zealand connections, New Zealand Math. Mag. 22 (3) (1986) , 112 - 123 .

- G T Tee, Charles Babbage (1791 - 1871) and his New Zealand connections, Roy. Soc. New Zealand Bull. 21 (1984) , 81 - 90 .

- G J Tee, The heritage of Charles Babbage in Australasia, Ann. Hist. Comput. 5 (1) (1983) , 45 - 59 .

- G J Tee, Charles Babbage materials in New Zealand and Australia, Historia Math. 9 (3) (1982) , 344 - 345 .

- P J Turvey, Sir John Herschel and the abandonment of Charles Babbage's Difference Engine No. 1 , Notes and Records Roy. Soc. London 45 (2) (1991) , 165 - 176 .

- A W Van Sinderen and M R Williams, Happy birthday Mr Babbage, Ann. Hist. Comput. 13 (2) (1991) , 125 - 139 .

- A W Van Sinderen, Babbage's letter to Quetelet, May 1835 , Ann. Hist. Comput. 5 (3) (1983) , 263 - 267 .

- A W Van Sinderen, The printed papers of Charles Babbage, Ann. Hist. Comput. 2 (2) (1980) , 169 - 185 .

- R Webster, Charles Babbage : the man behind the machines, Mathematical Spectrum 24 , 34 - 41 .

- M V Wilkes, Herschel, Peacock, Babbage and the development of the Cambridge curriculum, Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 44 (1990) , 205 - 219 .

- M V Wilkes, Babbage's expectations for his engines, Ann. Hist. Comput. 13 (2) (1991) , 141 - 145 .

- M V Wilkes, The design of a control unit - reflections on reading Babbage's notebooks, Ann. Hist. Comput. 3 (2) (1981) , 116 - 120 .

- M V Wilkes, Babbage as a computer pioneer, Historia Math. 4 (4) (1977) , 415 - 440 .

- M V Wilkes, Charles Babbage - the great uncle of computing?, Comm. ACM 35 (3) (1992) , 15 - 21 .

- M R Williams, Babbage and Bowditch : a transatlantic connection, Ann. Hist. Comput. 9 (3 - 4) (1988) , 283 - 290 .

- M R Williams, The scientific library of Charles Babbage, Ann. Hist. Comput. 3 (3) (1981) , 235 - 240 .

- L Yntema, Charles Babbage (1792 / 1871) ( Dutch ) , Verzekerings-Arch. 54 (3) (1977) , 189 - 205 .

Additional Resources ( show )

Other pages about Charles Babbage:

- Charles Babbage and deciphering codes

- Charles Babbage on Laplace Fourier and Biot

- Times obituary

- The cover of Babbage's Economy of Manufacturers and Machinery (1832) showing a medallion of Roger Bacon

- Multiple entries in The Mathematical Gazetteer of the British Isles ,

- Miller's postage stamps

- Heinz Klaus Strick biography

Other websites about Charles Babbage:

- Dictionary of Scientific Biography

- Dictionary of National Biography

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Lyndhurst STEM Club for Girls

- Science Museum London

- Fourmilab ( The analytical engine - including Menebrae's article )

- Jonathan Bowen

- Virginia Tech

- Gutenberg Project ( Reflections on the Decline of Science in England )

- History of Computing Project

- Sci Hi blog

- Renaissance Mathematicus

- MathSciNet Author profile

- zbMATH entry

Honours ( show )

Honours awarded to Charles Babbage

- Fellow of the Royal Society 1816

- Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1820

- Lucasian Professor 1828

- Lunar features Crater Babbage

- Popular biographies list Number 80

Cross-references ( show )

- Societies: British Association for the Advancement of Science

- Societies: Royal Astronomical Society

- Societies: Royal Statistical Society

- Societies: Turin Mathematical Society

- Other: 12th January

- Other: 13th July

- Other: 14th June

- Other: 2009 Most popular biographies

- Other: 3rd July

- Other: 5th June

- Other: 7th May

- Other: Cambridge Colleges

- Other: Cambridge Individuals

- Other: Cambridge professorships

- Other: Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (C)

- Other: Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (D)

- Other: Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (M)

- Other: Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (N)

- Other: Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Other: Jeff Miller's postage stamps

- Other: London Learned Societies

- Other: London Museums

- Other: London individuals A-C

- Other: London individuals H-M

- Other: Most popular biographies – 2024

- Other: Other Institutions in central London

- Other: Other institutions in Cambridge

- Other: Oxford Institutions and Colleges

- Other: Popular biographies 2018

The First Computer

Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine

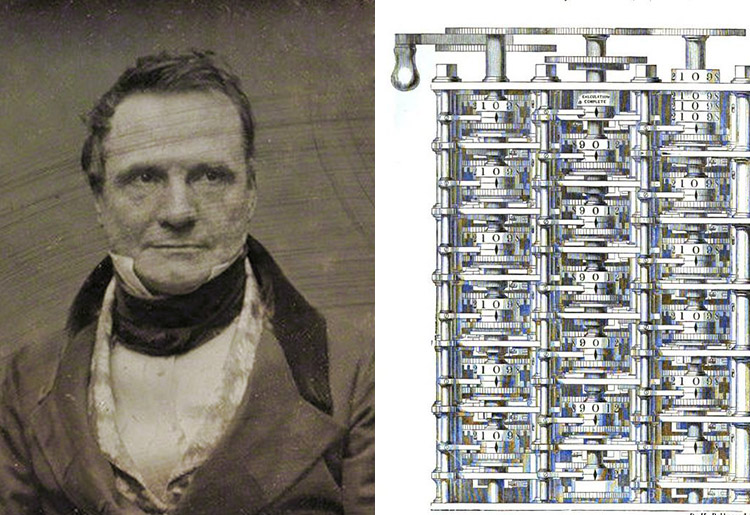

Mrjohncummings/Wikimedia Commons/CC ASA 2.0G

- European History Figures & Events

- Wars & Battles

- The Holocaust

- European Revolutions

- Industry and Agriculture History in Europe

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

- B.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

The modern computer was born out of the urgent necessity after the Second World War to face the challenge of Nazism through innovation. But the first iteration of the computer as we now understand it came much earlier when, in the 1830s, an inventor named Charles Babbage designed a device called the Analytical Engine.

Who Was Charles Babbage?

Born in 1791 to an English banker and his wife, Charles Babbage (1791–1871) became fascinated by math at an early age, teaching himself algebra and reading widely on continental mathematics. When in 1811, he went to Cambridge to study, he discovered that his tutors were deficient in the new mathematical landscape, and that, in fact, he already knew more than they did. As a result, he took off on his own to found the Analytical Society in 1812, which would help transform the field of math in Britain. He became a Royal Society member in 1816 and was a co-founder of several other societies. At one stage he was Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, although he resigned this to work on his engines. An inventor, he was at the forefront of British technology and helped create Britain’s modern postal service, a cowcatcher for trains, and other tools.

The Difference Engine

Babbage was a founding member of Britain’s Royal Astronomical Society, and he soon saw opportunities for innovation in this field. Astronomers had to make lengthy, difficult, and time-consuming calculations that could be riddled with errors. When these tables were being used in high stakes situations, such as for navigation logarithms, the errors could prove fatal. In response, Babbage hoped to create an automatic device that would produce flawless tables. In 1822, he wrote to the Society’s president, Sir Humphry Davy (1778–1829), to express this hope. He followed this up with a paper, on the "Theoretical Principles of Machinery for Calculating Tables," which won the first Society gold medal in 1823. Babbage had decided to try and build a "Difference Engine."

When Babbage approached the British government for funding, they gave him what was one of the globe’s first government grants for technology. Babbage spent this money to hire one of the best machinists he could find to make the parts: Joseph Clement (1779–1844). And there would be a lot of parts: 25,000 were planned.

In 1830, Babbage decided to relocate, creating a workshop that was immune to fire in an area that was free from dust on his own property. Construction ceased in 1833, when Clement refused to continue without advance payment. However, Babbage was not a politician; he lacked the ability to smooth relationships with successive governments, and, instead, alienated people with his impatient demeanor. By this time the government had spent £17,500, no more was coming, and Babbage had only one-seventh of the calculating unit finished. But even in this reduced and nearly hopeless state, the machine was at the cutting edge of world technology.

Difference Engine #2

Babbage wasn't going to give up so quickly. In a world where calculations were usually carried to no more than six figures, Babbage aimed to produce over 20, and the resulting Engine 2 would only need 8,000 parts. His Difference Engine used decimal figures (0–9)—rather than the binary ‘bits’ that Germany’s Gottfried von Leibniz (1646–1716) preferred—and they would be set out on cogs/wheels that interlinked to build up calculations. But the Engine was designed to do more than mimic an abacus: it could operate on complex problems using a series of calculations and could store results within itself for later use, as well as stamp the result onto a metal output. Although it could still only run one operation at once, it was far beyond any other computing device the world had ever seen. Unfortunately for Babbage, he never finished the Difference Engine. Without any further government grants, his funding ran out.

In 1854, a Swedish printer called George Scheutz (1785–1873) used Babbage’s ideas to create a functioning machine that did produce tables of great accuracy. However, they had omitted security features and it tended to break down, and, consequently, the machine failed to make an impact. In 1991, researchers at the London’s Science Museum, where Babbage's records and trials kept, created a Difference Engine 2 to the original design after six years of work. DE2 used around 4,000 parts and weighed just over three tons. The matching printer was completed in 2000, and had as many parts again, although a slightly smaller weight of 2.5 tons. More importantly, it worked.

The Analytical Engine

During his lifetime, Babbage was accused of being more interested in the theory and cutting edge of innovation than actually producing the tables the government was paying him to create. This wasn’t exactly unfair, because by the time the funding for the Difference Engine had evaporated, Babbage had come up with a new idea: the Analytical Engine. This was a massive step beyond the Difference Engine: it was a general-purpose device that could compute many different problems. It was to be digital, automatic, mechanical, and controlled by variable programs. In short, it would solve any calculation you wished. It would be the first computer.

The Analytical Engine had four parts:

- A mill, which was the section that did the calculations (essentially the CPU)

- The store, where the information was kept recorded (essentially the memory)

- The reader, which would allow data to be entered using punched cards (essentially the keyboard)

- The printer

The punch cards were modeled on those developed for the Jacquard loom and would allow the machine a greater flexibility than anything ever invented to do calculations. Babbage had grand ambitions for the device, and the store was supposed to hold 1,050 digit numbers. It would have a built-in ability to weigh up data and process instructions out of order if necessary. It would be steam-driven, made of brass, and require a trained operator/driver.

Babbage was aided by Ada Lovelace (1815–1852), daughter of the British poet Lord Byron and one of the few women of the era with an education in mathematics. Babbage greatly admired her published translation of a French article on Babbage's work, which included her voluminous notes.

The Engine was beyond what Babbage could afford and maybe what technology could then produce, but the government had grown exasperated with Babbage and funding was not forthcoming. Babbage continued to work on the project until he died in 1871, by many accounts an embittered man who felt more public funds should be directed towards the advancement of science. It might not have been finished, but the Analytical Engine was a breakthrough in imagination, if not practicality. Babbage’s engines were forgotten, and supporters had to struggle to keep him well regarded; some members of the press found it easier to mock. When computers were invented in the twentieth century, the inventors did not use Babbage’s plans or ideas, and it was only in the seventies that his work was fully understood.

Computers Today

It took over a century, but modern computers have exceeded the power of the Analytical Engine. Now experts have created a program that replicates the abilities of the Engine , so you can try it yourself .

Sources and Further Reading

- Bromley, A. G. " Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine, 1838 ." Annals of the History of Computing 4.3 (1982): 196–217.

- Cook, Simon. " Minds, Machines and Economic Agents: Cambridge Receptions of Boole and Babbage ." Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 36.2 (2005): 331–50.

- Crowley, Mary L. " The "Difference" in Babbage's Difference Engine ." The Mathematics Teacher 78.5 (1985): 366–54.

- Hyman, Anthony. "Charles Babbage, Pioneer of the Computer." Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Lindgren, Michael. "Glory and Failure: The Difference Engines of Johann Müller, Charles Babbage, and Georg and Edvard Scheutz." Trans. McKay, Craig G. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1990.

- Biography of Charles Babbage, Mathematician and Computer Pioneer

- The History of Computers

- Biography of Ada Lovelace

- Biography of Ada Lovelace, First Computer Programmer

- Biography of Konrad Zuse, Inventor and Programmer of Early Computers

- The Atanasoff-Berry Computer: The First Electronic Computer

- The History of Computer Peripherals: From the Floppy Disk to CDs

- History of Computer Memory

- The IBM 701

- The History of the ENIAC Computer

- Biography of Mark Dean, Computer Pioneer

- The History of the Computer Keyboard

- Timeline of IBM History

- History's 15 Most Popular Inventors

- The History of Ethernet

- Important Innovations and Inventions, Past and Present

Charles Babbage (1791-1871)

Further references.

| The Babbage Pages home |

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

- Industrial Revolution

Charles Babbage: Victorian Computer Pioneer

Kyle Hoekstra

12 may 2022, @kylehoekstra.

The mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage is widely credited with creating the forerunner of modern programmable computers in the early 19th century. Though he is commonly described as the creator of the first mechanical computer, his most famous machines were not actually completed.

But his inventiveness wasn’t limited to computing: as a teenager, Babbage experimented with shoes that helped with walking on water, and he was also responsible for an array of interventions that helped change public life.

Here are 10 facts about Charles Babbage.

1. Charles Babbage was a poorly child

Charles Babbage was born in 1791 and baptised at St Mary’s, Newington in London on 6 January 1792. A serious fever led to him being despatched to a school near Exeter at the age of eight, and he would later have private tuition on account of his poor health. It was at the Holmwood Academy in Enfield where Babbage’s love of mathematics was first nurtured.

2. He was a top mathematician as a student

Babbage taught himself aspects of contemporary mathematics ahead of his entry to Cambridge University. Though he did not graduate with honours and a thesis of his was considered blasphemous, he was nevertheless elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1816.

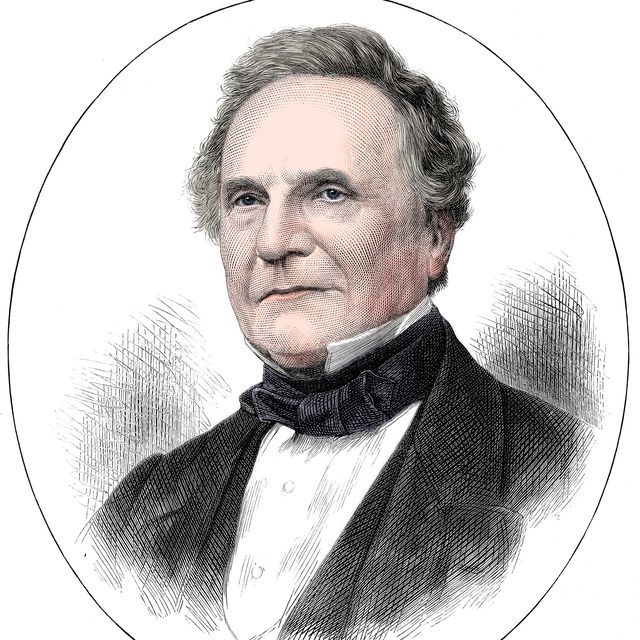

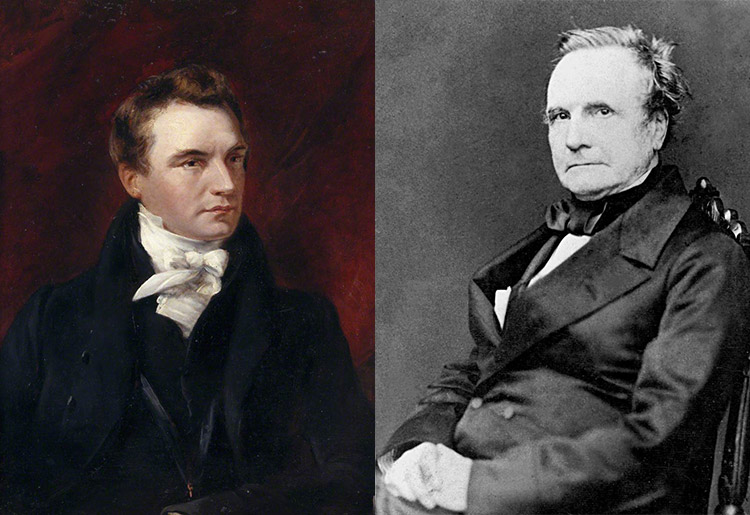

Portrait of Charles Babbage, c. 1820

Image Credit: National Trust, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

He struggled to establish the career in teaching that he sought, and as a result often leaned on his father for financial support. However, when his father died in 1827, he inherited an estate estimated to value, in today’s terms, around £8.85 million.

3. He was instrumental in setting up the Royal Astronomical Society

Babbage helped to found the Royal Astronomical Society in 1820, which aimed to circulate data and standardise astronomical calculations. As a member of the society, Babbage made mathematical tables which might be depended upon by astronomers, surveyors and navigators.

This was difficult work: it constituted repetitive tasks, yet required exquisite care. It was in this role that Babbage developed an idea for a labour-saving machine that could spit out the tables like clockwork.

4. His ‘Difference Engine’ could perform mathematical calculations

Babbage started designing a calculating machine in 1819, and by 1822 he had developed his ‘Difference Engine’.This was intended to use the differences between terms in a mathematical series to generate the contents of a navigational table, and he lobbied the British government for financial support to build a complete device.

The machine represented digits by positions on toothed wheels. When one wheel advanced from nine to zero, the next wheel in the series would advance by one digit. In this sense, it was able to carry a number in temporary storage, like a modern computer.

Babbage constructed a demonstration model of this Difference Engine in 1832, which he showed to audiences. He never finished the device to the intended room-sized proportions, although a functioning difference engine was constructed from Babbage’s original plans in 1991, proving the success of his design. Instead, Babbage looked to innovations across the Channel to inspire a yet more sophisticated mechanism.

5. Babbage created the more complex ‘Analytical Machine’

Babbage recognised in a new industrial weaving technology the potential for “a totally new engine possessing much more extensive powers”. First patented by French weaver and merchant Joseph-Marie Jacquard in 1804, the Jacquard machine automated pattern weaving by using a series of punched cards to give instructions to a loom.

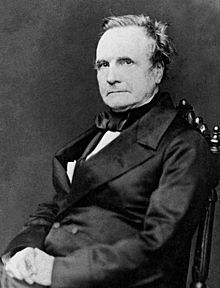

Charles Babbage, c. 1850 (left) / A portion of the difference engine (right)

Image Credit: National Portrait Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (left) / Woodcut after a drawing by Benjamin Herschel Babbage, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (right)

Jacquard’s invention transformed textile production, but it was also a predecessor for modern computing. It directly inspired the Analytical Machine with which Babbage cemented his legacy.

The Analytical Machine was more complex than the Difference Engine and it could undertake much more advanced operations. It did this by employing punched cards similar to the Jacquard machine as well as a memory unit able to hold 1,000 50-digit numbers. This was all supposed to be steam-powered, though Babbage didn’t complete his Analytical Machine.

6. He worked with Ada Lovelace

The mathematician Ada Lovelace was mentored by Charles Babbage, who arranged her tuition at the University of London. She went on to write an algorithm for the Analytical Machine which, had the machine been completed, would have enabled it to calculate a sequence of Bernoulli numbers.

She wrote of Babbage’s invention, “we may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.”

7. His inventions weren’t limited to computing

Babbage was active in many fields as an inventor. As a teenager, he came up with an idea for shoes intended to help walking on water. Later on, while working for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, he conceived of the cowcatcher.

Had he actually constructed one, it might have been the first of the plough-like devices that were mounted on the front of locomotives to push cows, and other obstructions, from the rails.

8. He campaigned to reform British science

Babbage firmly believed in the practical value of science to society but was disturbed by the conservatism of the British establishment which he was convinced held 18th-century British science back. To this end, he published Reflections of the Decline of Science in England in 1830, which painted a dismal picture of what society would look like if it failed to support scientific endeavour.

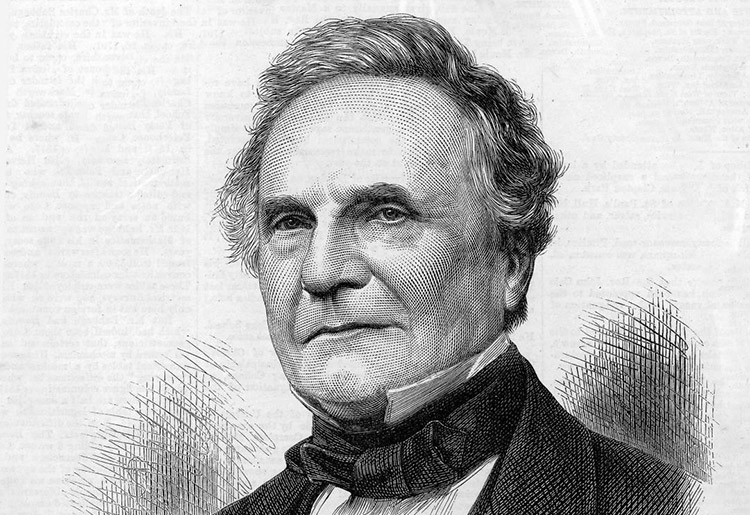

Charles Babbage in the Illustrated London News (4 November 1871)

Image Credit: Thomas Dewell Scott, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

9. He helped establish the modern postal system in England

As part of his membership of the Royal Astronomical Society, Babbage explored the demands of a modern postal system with Thomas Frederick Colby. One of the first interventions in the reform of the Royal Mail , the introduction of the Uniform fourpenny post in 1839, followed their conclusion that there should be a uniform rate.

10. Babbage’s brain is on display in London

On 18 October 1871, Charles Babbage died at home in London. His legacy is as a lifelong inventor prominent in the history of computers. It also takes material form in the halves of his brain which are preserved in two locations in London. One half of Babbage’s brain is located at the Hunterian Museum in the Royal College of Surgeons, while the other is on display at the Science Museum, London.

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

- MyU : For Students, Faculty, and Staff

Who was Charles Babbage?

"another age must be the judge." -babbage, 1837.

Charles Babbage was born on December 26, 1791, in Walworth, a district of London, United Kingdom. The son of Benjamin Babbage, a London banker. In his youth, Babbage was his own instructor in algebra, of which he was passionately fond, and was well read in the continental mathematics of his day. Upon entering Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1811, he found himself far in advance of his tutors in mathematics. Babbage co-founded the Analytical Society for promoting continental mathematics and reforming the mathematics of Newton then taught at the university.

In his twenties Babbage worked as a mathematician, principally in the calculus of functions. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1816 and played a prominent part in the foundation of the Astronomical Society (later Royal Astronomical Society) in 1820. It was about this time that Babbage first acquired the interest in calculating machinery that became his consuming passion for the remainder of his life.

Inventions & Achievements

In 1821 Babbage invented the Difference Engine to compile mathematical tables. On completing it in 1832, he conceived the idea of a better machine that could perform not just one mathematical task but any kind of calculation. This was the Analytical Engine (1856), which was intended as a general symbol manipulator, and had some of the characteristics of today’s computers.

Unfortunately, little remains of Babbage's prototype computing machines. Critical tolerances required by his machines exceeded the level of technology available at the time. And, though Babbage’s work was formally recognized by respected scientific institutions, the British government suspended funding for his Difference Engine in 1832, and after an agonizing waiting period, ended the project in 1842. There remain only fragments of Babbage's prototype Difference Engine, and though he devoted most of his time and large fortune towards construction of his Analytical Engine after 1856, he never succeeded in completing any of his several designs for it. George Scheutz, a Swedish printer, successfully constructed a machine based on the designs for Babbage's Difference Engine in 1854. This machine printed mathematical, astronomical and actuarial tables with unprecedented accuracy, and was used by the British and American governments.

Babbage occupied the Lucasian chair of mathematics at Cambridge from 1828 to 1839. He played an important role in the establishment of the Association for the Advancement of Science and the Statistical Society (later Royal Statistical Society). He also attempted to reform the scientific organizations of the period while calling upon government and society to give more money and prestige to scientific endeavor. Throughout his life Babbage worked in many intellectual fields typical of his day, and made contributions that would have assured his fame irrespective of the Difference and Analytical Engines.

End of Life

Despite his many achievements, the failure to construct his calculating machines, and in particular the failure of the government to support his work, left Babbage in his declining years a disappointed and embittered man. He died at his home in London on October 18, 1871. Though Babbage's work was continued by his son, Henry Prevost Babbage, after his death in 1871, the Analytical Engine was never successfully completed, and ran only a few "programs" with embarrassingly obvious errors.

Can't get enough Charles Babbage?

+ manuscript materials and exhibits.

- CBI holds a microfilmed copy of the Papers of Charles Babbage. The original papers are in the British Library .

- The University of Auckland, New Zealand , also has some of Babbage’s materials. CBI has photocopies of their holdings and the inventory to these copies, as well as other Charles Babbage materials held in the Charles Babbage Collection (CBI 54)

- The Science Museum in London constructed Babbage's Difference Engine No. 2 in 1991. The Science Museum Library and Archives in Wroughton holds the most comprehensive set of original manuscripts and design drawings.

+ CHARLES BABBAGE’S PUBLISHED WORKS

- A Comparative View of the Various Institutions for the Assurance of Lives (1826)

- Table of Logarithms of the Natural Numbers from 1 to 108,000 (1827)

- Reflections on the Decline of Science in England (1830)

- On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures (1832)

- Ninth Bridgewater Treatise (1837)

- Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864)

+ PUBLICATIONS ABOUT CHARLES BABBAGE

- Charles Babbage. Passages from the Life of a Philosopher . (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, Piscataway, NJ, 1994)

- Babbage, Henry Prevost . Babbage's Calculating Engines: A Collection of Papers . (Los Angeles: Tomash, 1982) Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series, vol. 2.

- Bromley, Allan G. "The Evolution of Babbage's Calculating Engines " Annals of the History of Computing , 9 (1987): 113-136.

- Buxton, H. W. Memoir of the Life and Labours of the Late Charles Babbage Esq ., F.R.S. (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1988) Charles Babbage Institute Reprint Series, vol. 13.

- Cambell-Kelly, Martin (ed.) The Works of Charles Babbage (11 vols.) (New York: New York University Press, 1989)

- Dubbey, John Michael. Mathematical Work of Charles Babbage . (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1978)

- Hyman, Anthony. Charles Babbage: Pioneer of the Computer . (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983)

- Moseley, Maboth. Irascible Genius: a Life of Charles Babbage, Inventor . (London: Hutchinson, 1964)

- Randell, Brian. "From Analytical Engine to Electronic Digital Computer: The Contributions of Ludgate, Torres, and Bush" Annals of the History of Computing , 4 (October 1982): 327.

- Swade, Doron. Charles Babbage and his Calculating Engines . (London: Science Museum, 1991)

- Swade, Doron. The Cogwheel Brain: Charles Babbage and the Quest to build the first Computer . (London: Little, Brown, 2001)

- Van Sinderen, Alfred W. "The Printed Papers of Charles Babbage" Annals of the History of Computing , 2 (April 1980); 169-185.

+ PUBLICATIONS ON BABBAGE AND ADA LOVELACE

- Huskey, Velma R., and Harry D. Huskey. "Lady Lovelace and Charles Babbage" Annals of the History of Computing 2 (October 1980): 299-329.

- Stein, Dorothy. Ada: A Life and A Legacy . (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985)

- Toole, B.A. "Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace, an analyst and metaphysician." Annals of the History of Computing 18 #3 (Fall 1996): 4-12.

- Fuegi, John, and Jo Francis. "Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'." Annals of the History of Computing 25 #4 (Oct-Dec 2003): 16-26.

- Wikipedia entry on Ada Lovelace .

- Future undergraduate students

- Future transfer students

- Future graduate students

- Future international students

- Diversity and Inclusion Opportunities

- Learn abroad

- Living Learning Communities

- Mentor programs

- Programs for women

- Student groups

- Visit, Apply & Next Steps

- Information for current students

- Departments and majors overview

- Departments

- Undergraduate majors

- Graduate programs

- Integrated Degree Programs

- Additional degree-granting programs

- Online learning

- Academic Advising overview

- Academic Advising FAQ

- Academic Advising Blog

- Appointments and drop-ins

- Academic support

- Commencement

- Four-year plans

- Honors advising

- Policies, procedures, and forms

- Career Services overview

- Resumes and cover letters

- Jobs and internships

- Interviews and job offers

- CSE Career Fair

- Major and career exploration

- Graduate school

- Collegiate Life overview

- Scholarships

- Diversity & Inclusivity Alliance

- Anderson Student Innovation Labs

- Information for alumni

- Get engaged with CSE

- Upcoming events

- CSE Alumni Society Board

- Alumni volunteer interest form

- Golden Medallion Society Reunion

- 50-Year Reunion

- Alumni honors and awards

- Outstanding Achievement

- Alumni Service

- Distinguished Leadership

- Honorary Doctorate Degrees

- Nobel Laureates

- Alumni resources

- Alumni career resources

- Alumni news outlets

- CSE branded clothing

- International alumni resources

- Inventing Tomorrow magazine

- Update your info

- CSE giving overview

- Why give to CSE?

- College priorities

- Give online now

- External relations

- Giving priorities

- Donor stories

- Impact of giving

- Ways to give to CSE

- Matching gifts

- CSE directories

- Invest in your company and the future

- Recruit our students

- Connect with researchers

- K-12 initiatives

- Diversity initiatives

- Research news

- Give to CSE

- CSE priorities

- Corporate relations

- Information for faculty and staff

- Administrative offices overview

- Office of the Dean

- Academic affairs

- Finance and Operations

- Communications

- Human resources

- Undergraduate programs and student services

- CSE Committees

- CSE policies overview

- Academic policies

- Faculty hiring and tenure policies

- Finance policies and information

- Graduate education policies

- Human resources policies

- Research policies

- Research overview

- Research centers and facilities

- Research proposal submission process

- Research safety

- Award-winning CSE faculty

- National academies

- University awards

- Honorary professorships

- Collegiate awards

- Other CSE honors and awards

- Staff awards

- Performance Management Process

- Work. With Flexibility in CSE

- K-12 outreach overview

- Summer camps

- Outreach events

- Enrichment programs

- Field trips and tours

- CSE K-12 Virtual Classroom Resources

- Educator development

- Sponsor an event

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Charles Babbage (born December 26, 1791, London, England—died October 18, 1871, London) was an English mathematician and inventor who is credited with having conceived the first automatic digital computer. Charles Babbage. In 1812 Babbage helped found the Analytical Society, whose object was to introduce developments from the European ...

Synopsis. Charles Babbage was an English mathematician, philosopher and inventor born on December 26, 1791, in London, England. Often called "The Father of Computing," Babbage detailed plans ...

Professor Charles Babbage (1792 - 1871), mathematician and inventor of the unfinished Babbage Difference Engine a mechanical programmable computer, circa 1860. Charles Babbage (December 26, 1791-October 18, 1871) was an English mathematician and inventor who is credited with having conceptualized the first digital programmable computer.

Early life Portrait of Charles Babbage (c. 1820)Babbage's birthplace is disputed, but according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography he was most likely born at 44 Crosby Row, Walworth Road, London, England. A blue plaque on the junction of Larcom Street and Walworth Road commemorates the event.. His date of birth was given in his obituary in The Times as 26 December 1792; but then a ...

Biography. Charles Babbage was born on December 26, 1791, the son of Benjamin Babbage, a London banker. As a youth Babbage was his own instructor in algebra, of which he was passionately fond, and was well read in the continental mathematics of his day. Upon entering Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1811, he found himself far in advance of his ...

Charles Babbage was born on Dec. 26, 1791 in England. He was a polymath and became a mathematician, mechanical engineer, inventor, and philosopher. He contributed to many different scientific fields but his most famous work is designing a programmable computing device. Charles Babbage is considered the "father of the computer" and is given ...

This genius woman mathematician was history's first computer programmer - and a fitting partner to Babbage in ushering in modern computing. Lasting Legacy as Computing Pioneer. Frustrated at being unable to build his wondrous Engines, Charles Babbage died in 1871 in London, never gaining the wealth or acclaim he deserved during his lifetime.

Charles Babbage (26 December 1791 - 18 October 1871) was an English mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer who developed the concept of a programmable computer. "The whole of arithmetic now appeared within the grasp of mechanism." - Charles Babbage, (1864) Passages from the Life of a Philosopher, ch. 8 of the Analytical Engine Babbage […]

Charles Babbage was born on 26 December 1791, probably in London, the son of a banker. He was often unwell as a child and was educated mainly at home. By the time he went to Cambridge University ...

Charles Babbage (1791-1871) was born in Walworth, Surrey, on December 26, 1791. He was one of four children born to the banker Benjamin Babbage and Elizabeth Teape. He attended Trinity, Cambridge, in 1810 to study mathematics, graduated without honors from Peterhouse in 1814 and received an MA in 1817. In 1814 he married Georgiana Whitmore with ...

Charles Babbage (1791-1871) was an English inventor and mathematician whose mathematical machines foreshadowed the modern computer. He was a pioneer in the scientific analysis of production systems. ... It contains an excellent short biography by the Morrisons, a selection of Babbage's works, and associated material on the engines.

Biography Both the date and place of Charles Babbage's birth were uncertain but have now been firmly established.In [1] and [12], for example, his date of birth is given as 26 December 1792 and both give the place of his birth as near Teignmouth. Also in [18] it is stated:- Little is known of Mr Babbage's parentage and early youth except that he was born on 26 December 1792.

Charles Babbage, detail of an oil painting by Samuel Lawrence, 1845; in the National Portrait Gallery, London. Charles Babbage, (born Dec. 26, 1791, London, Eng.—died Oct. 18, 1871, London), British mathematician and inventor. Educated at Cambridge University, he devoted himself from about 1812 to devising machines capable of calculating ...

Though computers weren't ever built until the mid-1900s, the first idea for a computer was actually developed starting in 1837. Charles Babbage, born to a wealthy London family in 1791, was the brain behind the idea, and is famous for his work developing plans for two different computers.

Babbage, Charles (1791-1871) English mathematician and inventor. Babbage was obsessed from his boyhood with the idea of an universal language, and he conceived his first mechanical calculator around 1812 while he was a student at the Trinity College in Cambridge, England. At that time, he was involved in research on differential and integral ...

The modern computer was born out of the urgent necessity after the Second World War to face the challenge of Nazism through innovation. But the first iteration of the computer as we now understand it came much earlier when, in the 1830s, an inventor named Charles Babbage designed a device called the Analytical Engine.

Charles Babbage is considered the father of computing. Inventor Charles Babbage lived in a time that most people today do not associate with computer science. He was born in the late 1700s toward ...

Charles Babbage was one of the key figures of a great era of British history. Born as the industrial revolution was getting into its swing, by the time Babbage died Britain was by far the most industrialized country the world had ever seen. Babbage played a crucial rôle in the scientific and technical development of the period.

Charles Babbage. (1791-1871). English mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage is credited with having conceived the first automatic digital computer. He also designed a type of speedometer and the cowcatcher (a sloping frame on the front of a locomotive that tosses obstacles off the railroad tracks). Babbage was born on December 26, 1791 ...

Abstract. Most people have heard something about Charles Babbage, F.R.S., whose work on computers in the nineteenth century was much ahead of its time. Babbage worked on two computing devices, neither of which he completed: the Difference Engine and the Analytical Engine. It is the Analytical Engine that gives him a claim to major fame.

Listen Now. 1. Charles Babbage was a poorly child. Charles Babbage was born in 1791 and baptised at St Mary's, Newington in London on 6 January 1792. A serious fever led to him being despatched to a school near Exeter at the age of eight, and he would later have private tuition on account of his poor health.

Charles Babbage was born on December 26, 1791, in Walworth, a district of London, United Kingdom. The son of Benjamin Babbage, a London banker. In his youth, Babbage was his own instructor in algebra, of which he was passionately fond, and was well read in the continental mathematics of his day. Upon entering Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1811 ...

In short, Babbage's Analytical Engine offered functions for input, output, storage, and processing. In many respects, it was the first true predecessor of the modern computer. Ada Lovelace and Italian Followers. Babbage is variously called the father of the computer, the inventor of the computer, and the first computer scientist.