An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Educ Health Promot

Investigating the reasons for students’ attendance in and absenteeism from lecture classes and educational planning to improve the situation

Sepideh mokhtari.

Education Development Office, School of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Sakineh Nikzad

1 Department of Prosthodontics, School of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Saeedeh Mokhtari

2 Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Siamak Sabour

3 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, School of Public Health and Safety, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Sepideh Hosseini

Background:.

This study investigated the reasons for the students’ attendance in and absenteeism from lecture classes from the perspective of professors, students, and educational planning to change the unsatisfactory status quo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The present study was a narrow needs assessment survey which was performed on students ( n = 70) of the Faculty of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, in four stages. In the first stage, the opinions of professors and students about the reasons for absenteeism from the lecture classes were collected. In the second stage, the results of the first stage were discussed by an expert panel to find solutions for the problem. The results of the survey were tabulated, summarized, and discussed. In the third stage, online classes were held as one of the solutions and evaluated in the fourth stage.

The results showed that various factors, such as professor empowerment, evaluation system, audiovisual equipment of the classes, educational curriculum, and class schedules, are associated with the students’ attendance in the classes. Along with these factors, one of the most important reasons for students’ absenteeism from classes in recent years might be the generational differences of students. The evaluation of online classes showed that the ratio of the number of students who actively participated in the online classes to the number of students participating in the online classes varied from 30% to 64% ( P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION:

In addition to improving the factors associating students’ attendance in classes, online education is a proper solution for reducing absenteeism in lecture classes and increasing students’ active participation from the perspective of professors and students.

Introduction

Academic performance is one of the most critical issues of students in higher education. Since learning requires attendance and active participation in classes, attendance in classes is thought to be an essential factor in students’ academic performance.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] Previously, it was believed that students with a high attendance rate were more successful at the end of their course.[ 4 ] Students’ absenteeism from the classes significantly reduces academic achievement, which in turn disrupts the expected learning goals.[ 2 ] Class attendance and learning have received much attention, and there is a well-established positive relationship between class attendance and academic grades.[ 5 ] According to researchers, class attendance is a predictor of student success and reflects a student's positive learning habits, skills, and attitudes, all of which are directly related to their ultimate success.[ 6 ] Absenteeism is an essential issue in the medical and health sciences despite the strictness of attendance policies, affecting students’ performance around the world. Students who attend classes regularly receive useful information and use medical skills more professionally than others throughout their lives.[ 7 ] For example, nursing students’ absenteeism from classes adversely affects their performance and prolongs their duration of the study.[ 8 ] Absenteeism also prevents them from accessing relevant information and contact with relevant materials (clinical skills, lectures, and practical sessions) necessary for active learning.[ 9 ] Medical physiology education also states that classroom lectures should be considered an essential component.[ 10 ]

Although there is a high rate of absenteeism from classes, the students’ presence in the classes is significant to educational institutes because providing resources for this type of education is costly and challenging.[ 3 ] On the other hand, with the emergence of new educational technologies and new online learning methods, the level of interest and the presence of students in classes have decreased even more. Today, the world is affected by the widespread availability of the Internet, which paves the way for a revolution in education. Conventional classes have been replaced by smart classes with the latest technology.[ 11 ] The children of this generation are not confined to traditional textbooks and have more opportunities to access online education.

In recent years, in the Faculty of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, the low attendance rate of students in some lectures has attracted the attention of education planners in this faculty. This nonattendance has invoked protests by some faculty members in recent years. Therefore, to solve this problem, this study examined the root causes of the problem to provide plans to solve the problem.

Materials and Methods

The present study was a narrow needs assessment survey which was performed on students ( n = 70) of the Faculty of Dentistry, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, in four stages. We had a preset list of questions to be answered by a predetermined sample of the professors ( n = 24) and students ( n = 70) to answer these questions chosen in advance. In the first stage, the opinions of professors and students about the reasons for absenteeism from the lecture classes were collected. In the second stage, the results of the first stage were discussed by an expert panel to find solutions for the problem. The results of the survey were tabulated, summarized, and discussed. In the third stage, online classes were held as one of the solutions and evaluated in the fourth stage

The research steps were designed as follows:

- Step 1: Investigation of the factors associating with the attendance and absenteeism of students from classroom lectures

- Step 2: Provision of solutions to increase students’ attendance in classes

- Step 3: Implementation of the proposed solutions based on the set implementation priorities

- Step 4: Evaluation.

After the study protocol was approved by the Faculty Ethics Committee, the study was instituted.

Step 1: Evaluation of the factors affecting the attendance and absenteeism of students from classes from the perspective of professors and students

At this stage, the students’ opinions were collected both qualitatively and quantitatively by the “focus group” method, and the data were collected through a regional standard questionnaire. In this way, since face-to-face sessions with students and discussing open-end questions might help better identify the factors that associate with students’ attendance in classes, a focus group was formed, consisting of student representatives (approximately 10 from each academic year). Then, two faculty members on behalf of the Vice-Chancellor for Education interviewed these students and collected their opinions and views. In the next step, to quantify the students’ opinions, a valid and reliable questionnaire (Cronbach's α = 0.86) was submitted to all the clinical students. The questionnaire was designed in two parts: the study of factors associating with the presence and absence, each of which was based on 12 questions. The questions were scored on a five-point Likert scale and explained to the students before completing the questionnaire.

The professors’ views were also qualitatively examined by the “focus group” method. The young professors were only a few years older than the students, belonging almost to the same generation. Therefore, it was expected that the opinions of young professors would be different from those of experienced professors. As a result, two professors from each department of the faculty (including 12 departments), as young professors and experienced professors, were selected. Then, the opinions of these two groups of professors on the subject were examined in two separate sessions in the presence of the Vice-Chancellor for Education. In each of these sessions, 12 professors, project managers, and statistical consultants were present. This stage was carried out to analyze the reasons for students’ absence from the classes so that the results would be a basis for educational programming.

Step 2: A meeting of experts and provision of solutions to increase student attendance in classes for theoretical lessons

A meeting was held in the Educational Deputy Office with the project managers’ presence to determine proper strategies and plans. After reviewing the results of the students’ and professors’ opinions and summarizing the issues raised in the Educational Council Meeting, the project managers presented their strategies to increase the students’ attendance.

Step 3: Implementation of solutions based on executive priorities

Finally, one of the solutions was adopted by the Vice-Chancellor for Education of the Faculty of Dentistry and implemented.

Step 4: Evaluation

In this stage, to evaluate the proposed solution after its implementation, a meeting was held with the project managers and professors to collect the professors’ opinions. Besides, a reliable and valid regional standard questionnaire was designed to collect students’ opinions ( n = 70). With the cooperation of the University Development Office and the use of the e-poll system, a survey of students was conducted through the web. To get the results, data were analyzed using McNemar's test.

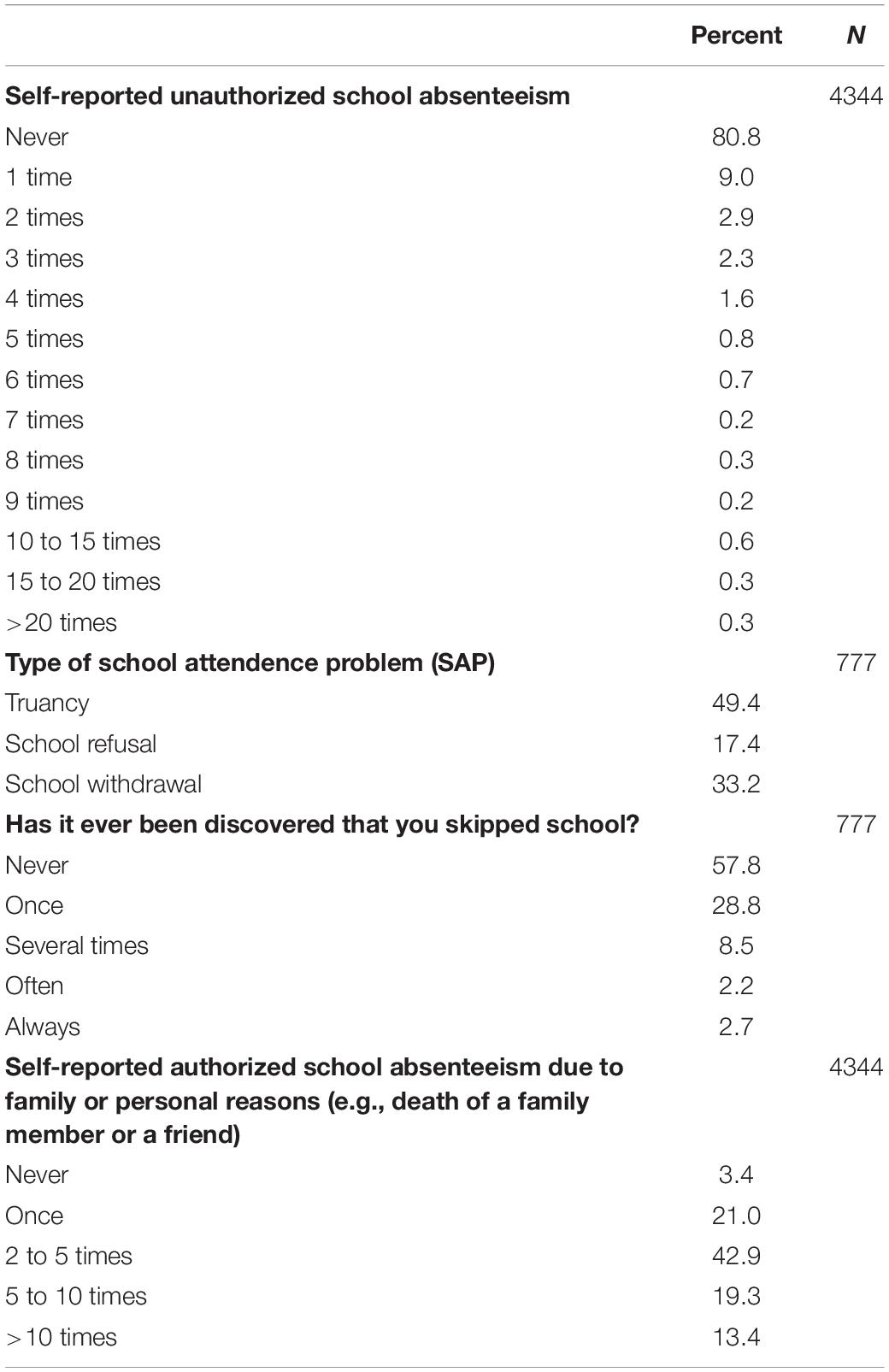

In the first stage, which included the evaluation of factors affecting attendance, 85 questionnaires were completed in the group with 70 students (71% response rate). Tables Tables1 1 and and2 2 present the results of the survey of clinical dental students of Tehran University of Medical Sciences on the reasons for attending and not attending the classes for theoretical courses, respectively.

Prioritizing the factors affecting the absence of lecture classes from the students’ perspectives

Prioritizing the factors affecting the attendance of lecture classes from the students’ perspectives

Factors which were responsible for attendance or absenteeism of students from the classes basis of the young and experienced professors 's evaluation showed in Table 3 .

Factors responsible for attendance or absenteeism of students from the classes basis of the young and experienced professors ‘s evaluation

In addition, the following were some of the highlights of the differences between the views of young and experienced professors:

- Both groups of young and experienced professors emphasized the development of virtual education

- In both groups, some professors believed in mandatory attendance, while others considered mandatory attendance useless, disturbing the classroom's peace

- Young professors laid greater emphasis on the practical and clinical nature of the material presented as an essential factor in attracting students, compared to experienced professors

- Young professors emphasized the rotational nature of the teaching curriculum of professors as an essential factor in attracting students and increasing the ability of professors

- Young professors believed that the exciting topics and chapters of the course that attract students are always in the experienced professors’ teaching agenda, and teaching entirely theoretical and unattractive topics is usually the responsibility of young professors

- Young professors emphasized presenting new educational methods, such as PBL, to increase students’ active learning

- Young professors pointed to the critical role of university policies in this regard and mentioned the gap in incentive policies for active professors in the education development compared to the incentive policies for research activities.

In stage 2, the project managers summarized the strategies for increasing student attendance in the following six areas after evaluating the students’ and professors’ points of view:

- Empowerment of professor

- Paying attention to the characteristics of the new generation (the need to benefit from new technologies and developments and promotion of virtual education)

- Improving the evaluation system

- Improving audiovisual equipment in classrooms

- Improving educational curricula

- Improving class schedules.

The project managers reviewed the six areas mentioned above, and the following points were raised about these areas:

- Professor empowerment requires policy-making and fundamental and long-term planning. It should be noted that although the faculty members might have higher capabilities for educating the learners compared to that in the past due to scientific developments, the mean abilities of current professors have not increased significantly over time

- The use of new technologies in the educational field has not improved significantly by considering the significant changes in the characteristics of the current generation compared to the students of previous decades

- The evaluation system performs better than that previously; however, fundamental changes and reforms are necessary

- The audio and visual equipment of the classes is undoubtedly more better and more numerous compared to previous years

- Concerning educational planning, the curriculum has improved in many cases. However, the timing and presentation of some topics are undesirable, necessitating a review of the new dental curriculum by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, which is beyond the jurisdiction of the faculty

- In some cases, the class schedule poses problems for students, with highly crowded classes on some days owing to a lack of time.

During the meeting, the project managers analyzed the points mentioned above and realized that although essential factors, such as the empowerment of professors, evaluation system, audiovisual equipment of the classes, educational curriculum, and class schedules, still need to be revised, they have improved to a great deal during the past decade. Therefore, they cannot be considered as the main reasons for students’ decreased desire to attend theoretical classes in recent years. Therefore, one of the most critical factors in reducing the presence of students in recent years could be a change in students’ generational preferences and ideals. In other words, today's students are more familiar with digital technology than ever before and benefit from them. The development of education is not possible without considering the developments in the present age, mainly in the field of information technology. E-learning is expanding globally, and many of the world's leading universities are taking advantage of it. The use of new technologies is not limited to virtual education, and virtual education, despite having many benefits, exhibits a lower rate of interaction between the professors and students than in conventional classes. However, this interaction forms the basis of learning in some educational topics. Therefore, virtual education could be used in cases where the simultaneous interaction of students and professors is needed at a low rate.

On the other hand, online classes, by taking advantage of virtual education, make it possible for professors and students to interact simultaneously on the web. Therefore, although it is not an in-person educational system (physical presence), it requires a kind of presence in the new world field, a presence that will become more acknowledged over time. It seems that online classes, like computers, would soon expand significantly. Therefore, it was suggested that online experimental educational classes should be held.

Finally, the project managers prioritized their planning and implementation to solve the problem of three issues, consisting of improving the capabilities of professors in using virtual education and digital technologies, paying more attention to virtual education and improving its quality, and holding online classes which is one of the new educational technologies with many benefits of in-person and non-in-person education.

The Vice-Chancellor for Education of the Faculty placed the online experimental educational classes on its agenda to develop new educational technologies in the faculty. The design and planning of the educational classes were carried out online; after coordination and education, the professors and students held online classes for at least 1 h for each of the four theoretical lessons. Online classes were selected so that students from four different academic years participated in the study.

Project managers’ evaluation of the online class attendance

Due to mandatory attendance, many students attend university classes reluctantly. Therefore, they only have a physical presence in the classroom, and in many cases, they interfere with the learning process of other students by disturbing the peace of the class. Therefore, the effective presence of students and their active participation in classes is necessary and vital. Since holding online classes for the first time was experienced by students and participating in it required some software measures for students, there were fears that many students would not be interested if they are not forced to attend the classes. Therefore, attending these classes, like conventional classes, was considered mandatory, and in the evaluation, their active presence in the classes was measured. The classes were held beyond the working hours of the faculty by coordination between the instructors and students.

Due to the mandatory attendance in conventional and online classes, the official attendance of students in both classes was almost the same. As mentioned, students’ active participation and level of activity are vital for the learning process. Therefore, the project managers considered the participation of students in online classes as an indicator of their active presence in such classes. The students’ answers to the questions posed by the professors in class and the students’ scientific questions were considered the students’ active participation. The classes were recorded to estimate the ratio of students with active participation to the total number of students present, which was estimated at 30%–64%, depending on the teaching method used, the number of questions and answers, and students’ engagement in scientific discussions. It should be noted that many students had more than one scientific activity and active participation in class, which was not calculated in the students’ participation percentage.

eProfessors’ opinions on the impact of online classes on student attendance

After holding the online classes, a meeting was held with the project managers and instructors involved to collect the comments and suggestions of the professors. After expressing their desire to hold these classes again, the professors evaluated the active participation of students in the classes as desirable and mentioned the role of online classes in increasing students’ active participation. The professors mentioned positive aspects of this project, including the possibility of roll call (which means physical presence and not necessarily active participation) in online classes like conventional classes, the possibility of re-using the classes by students since they were allowed to record the class, the impossibility of disturbing the class peace by students who are reluctant to benefit from the class, resulting in more active participation of interested students, and creating a useful environment for students with lower self-esteem who were not active in conventional classes.

Students’ feedback assessment about attending online classes

To collect the opinions of the students, a reliable and valid questionnaire was designed, and with the cooperation of the University Development Office and using the e-poll system, the students completed it through the web. Table 4 presents the results of this questionnaire. The results showed that the majority of the students were satisfied with attending online classes and the learning process in these classes. The students were eager to continue taking part in such classes, and the vast majority (80%) were reluctant to attend conventional classes with roll calls. The majority of the students (about 90%) considered recording the classroom content an essential advantage for online classes.

Student survey results about online classes based on the questionnaire

In another survey conducted as a focus group of 30 students participating in online classes, the students were asked if their active participation in online classes was more effective compared to conventional classes. This survey results showed that 73.4% of students believed that active participation and attention to educational content in online classes were better than those of conventional classes. Some students believed that the comfort of online classes, the lack of noise from other students, and the focus on the computer screen and the professor's lecture were the most important factors. However, 16.6% believed that their attention was better in conventional classes, and 10% considered conventional and online classes the same from this perspective. Most of the students’ criticisms of online classes were related to unconventional hours, stating that they were interested in attending classes during the regular hours, if possible. Students also found attending online classes easier than attending conventional classes due to the lack of commuting.

After reviewing the evaluations (reviewing by the project executives of the professors’ and students’ opinions), the active participation of students in online classes was deemed as effective, and according to the surveys, the active participation of students and their desire to attend these classes were higher compared to conventional classes.

Students’ absenteeism is a significant concern for higher and academic education around the world. One of the most important reasons for a decrease in students’ attendance classes in recent years might be their generational differences choices. As a limitation of our study, we did not try out the survey on a test group. A test group could let us know if our instructions are clear and if our questions make sense. Therefore, we did not revise the survey on the basis of our test group feedback.

Various studies have suggested many reasons for this. Magobolo and Dube[ 9 ] considered the reasons for the absence of nursing students as illness and not receiving payment for working in their study. Desalegn et al .[ 12 ] reported that the main reasons in the questionnaire completed by students for missing classes were preparing for an examination, an unfavorable class schedule, a lack of interest in the subject, a lack of interest in the teaching style, and ease of understanding the subject without guidance. They believed that not only the behavior of the students but also the characteristics of the teachers and the teaching methods to be effective in the absenteeism of the students from the lectures. In the present study too, the teaching method was considered as the main reason for missing classes due to generational preferences and was further reviewed. Abdelrahman and Abdelkader[ 8 ] showed that nursing students too attributed the main reasons for their absenteeism to educational factors, including a lack of staff in the clinical field and a lack of understanding of the lecture's content. The present study considered another factor to be more critical by considering the empowerment of the professors. A study by Bati et al .[ 13 ] on dental, medical, pharmaceutical, and nursing students showed that the factors that prevent students from attending class lectures are mainly individual (insomnia, lack of health, and the like) and the inefficiency of lecturing in a crowded hall. It is essential to improve the coaching and mentoring system by considering individual and external factors that have a critical impact on students’ attendance. In the present study, the educational aspect was the main reason for absenteeism, and factors such as fatigue and poor classroom conditions were the other less important reasons. Rawlani et al .[ 14 ] stated that the main reason for not attending lectures is the lack of motivation of students to learn. They said that new teaching styles need to be looked into. As in our study, a new way of teaching online was proposed as a solution.

So far, various solutions have been suggested to solve the problem of students’ absenteeism from class lectures. Sharmin et al .[ 1 ] showed that the use of strict roll call policies might affect students’ attendance, and medical schools should reinforce this policy to improve their students’ academic performance. However, according to the present study, it is important to note that this policy does not lead to active student attendance and probably does not improve their academic performance. Al-Shammari[ 15 ] showed that using management techniques and class attendance rules (such as assigning a portion of the total score, extra points to attend classes, and more assignments, or deducing grades for not attending or attending classes with delay) significantly increased the attendance of higher education students and on-time arrival at the class. These improvements were significantly correlated with students’ academic achievement. Thekedam and Kottaram[ 16 ] too reported that, to eradicate the problem of absenteeism, efforts must be made to address all factors in broader social, economic, and political environments, rather than focusing merely on students or faculties. They cited early interventions and preventative measures, positive reinforcement, and rewards for students who improved their attendance as practical factors in reducing chronic absenteeism and advised establishing programs for staff development, workshops, conferences, and symposiums to improve the professors’ performance by the faculty management. Professors who have tried interactive and innovative lecturing methods, by giving better and more engaging lectures, could change students’ attitudes and provide an environment that can reduce student absenteeism.

In the present study, the most important reason for the absence of dental students was the generational characteristics and subsequent changes in students’ learning passion and preferences. In the definition of generations, individuals born in 1995 or later are referred to as Generation Z.[ 17 ] These individuals are indeed our current students. Over the years, this generation has been given various names, such as Generation Z, Internet Generation, and iGeneration, because they are mainly characterized by computer addiction as well as addiction to any other type of technology. What sets this generation apart from previous generations is that they are the “most electronic generation” in history and have grown up with technology. They are growing with the Internet, cell phones, laptops, iPods, tablets, and other electronic devices that have become part of their daily lives.[ 18 ] Generation Z prefers nontraditional teaching methods and likes to use logic-based and practical learning approaches.[ 17 ] Instead of taking notes, Generation Z students rely on computer records, are more inclined to ask questions online, and do not like to wait for answers. Instead, they prefer immediate information and communication. Generation Z students do now fill our classrooms and expect an educational environment in which they can interact in the same way they do in their virtual world. This means the demand for immediate information, visual forms of learning, and the replacement of “communication” with “interaction.”[ 19 ] Active learning classes, such as flipped classrooms or problem-based learning methods, are more popular with this younger generation.[ 20 ]

In this study, holding online classes was proposed and implemented to solve the problem of student absenteeism. The results showed that the ratio of the students with active participation in the online class to the total number of participating students varied from 30% to 64%. Besides, the results of a survey of students’ opinions showed that the majority of the students were satisfied with attending online classes and the quality of learning in these classes. Similar results have been achieved in other studies on dental students.[ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] Changiz et al .[ 26 ] observed that students showed good readiness in all components of e-learning. Hence, the instructional designer can trust the e-learning strategies and build the course based on them. Dalmolin et al .[ 17 ] showed that in addition to the positive attitude of dental students toward e-learning, the use of websites as a supportive tool for learning was significantly different between different age groups. Younger students believed that websites were a better tool to help them learn compared to older students.

Rensburg carried out a systematic review of the data from 36 articles on online classes and reported results consistent with the present study. It can be concluded from the similar results of these two studies that online teaching and learning has positive results, such as increasing student satisfaction and motivation, improving problem-solving skills, increasing flexibility for learning, and increasing student participation for undergraduate health sciences educators and students. Rensburg[ 27 ] reported that unstable Internet connectivity, inadequate Internet access, technological problems, and concerns about useful and fast feedback to students as challenges to online teaching and learning. Ochs[ 28 ] also showed that the online classes were more efficient in some teaching areas compared to classroom instruction; therefore, determining the teaching topics in online class planning is one of the most critical topics in organizing and designing these classes. Kwok et al .[ 29 ] and Tse and Ellman[ 30 ] reported that a combination of online education with conventional class-based teaching might play an essential role in improving students’ scientific knowledge and increasing their skills in clinical areas. A review by Tang et al .[ 31 ] showed that the integration of online lectures in undergraduate medical education is more acceptable by students and leads to improved knowledge and clinical skills. The results of the present study are consistent with many studies focusing on medical education.[ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]

Fadol et al .[ 40 ] showed that both online and flipped classes were held better than the conventional classes, and flipped classes were held better than the online classes. Furthermore, students who had access to online content missed fewer classes and performed better. All these studies are consistent with the current study. However, there are studies with different results, such as that by Fish and Snodgrass,[ 41 ] which advocated conventional education (face to face) of students. The reasons for this preference were reported to be motivation and discipline in conventional teaching and concerns about learning in online courses. The study suggested that taking a course in online classes and preparing for them could help students gain a realistic understanding of online classes and produce a positive impact. A meta-analysis in 2015 also found that students performed better in conventional classes. It considered that online classes were not affordable for institutions, and reported that the possibility for students to leave online courses and changes in existing technologies were the weak points of online classes.[ 42 ] Some of the problems in the present study were a lack of sufficient funding due to the impossibility of holding classes during the regular hours, a lack of sufficient experience of some professors in holding classes (which was solved with the help of the support system), and a lack of access to laptops for all the students (some students shared their laptops with classmates).

Finally, e-learning makes it possible for students to tailor the educational content to their individual learning styles with visual media, charts, digital content, interactive videos, or web-based interactions. This is facilitated by the use of mobile devices that provide easy access. Learning online could be an excellent option to help university professors teach future dentists. Teachers need to acknowledge that by introducing e-learning courses, they can encourage students to use online tools to educate and communicate with their professors and peers. Typically, teaching in dentistry relies more on visual techniques; therefore, students are more interested in visual transmission than text transmission.[ 17 ]

Undoubtedly, with the rapid advances in educational technologies and virtual teaching methods around the world, and with generational preferences of students, soon, the physical space of most universities will become centers merely for program coordination for educational courses. Theoretical classes will be held only with new and online methods. With the advances in online classroom software, a complete simulation of conventional classes will be possible virtually so that each individual will sit in a specific chair in the virtual classroom and will be trained. Clearly, at that time, having the skills to use these technologies and using new methods of virtual learning for professors will be an essential measure of excellence and success.

The results showed that various factors, such as the empowerment of professors, evaluation system, audiovisual equipment of the classes, educational curriculum, and class schedules, affect the attendance of students in the classroom. However, significant progress has been made in many of these factors over the past decade. Therefore, along with these factors, one of the most important reasons for the decrease in the attendance of students in recent years could be related to the change of generation and preferences of students. Since the new generation is more inclined to use educational technologies, in the present study, online classes were used as a solution to increase the active participation of students in the classrooms. The results showed that online classes are suitable from the perspective of professors and students and could significantly increase the participation of students in class lectures.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. MJ Kharazi Fard and all professors and students in Dental School of Tehran University of Medical Sciences for their assistance in this study.

A Diagnostic Analysis of Absenteeism—A Case Study in a Portuguese Cork Industry

- First Online: 21 February 2020

Cite this chapter

- Alfredo Silva 11 ,

- Ana Luísa Ramos 12 ,

- Marlene Brito 13 &

- António Ramos 14

Part of the book series: Studies in Systems, Decision and Control ((SSDC,volume 277))

1174 Accesses

Absenteeism is defined as the absence of a worker from his or her workplace during a normal day’s work schedule and is seen as a problem which companies face every day. The absence of an employee can result in a significant drop in productivity and the company’s daily revenue can be negatively impacted by it, which when multiplied by the absence of multiple workers in different days can have a harmful impact on the company’s production. However, most managers neither understand nor have looked into the causes of their absence issue. This study took place at a company which produces cork stoppers, which deals with a problem of high absenteeism that costs around 1,200,000 € per year to the company. The main goal of this study is to identify the sectors which have the highest percentage of absenteeism, quantify its impact on related outcomes and diagnose its causes. The results show that, most absenteeism occurs in production areas and the causes are related to musculoskeletal problems. The consequences involve various costs to the society, some of them difficult to quantify. The methodology used in this study was the action research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bitner, M.J., Bernard, H.B., Tetreault, M.S.: The service encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J. Mark. 54 , 71–84 (1990)

Article Google Scholar

Nickson, D., Tom, B., Erwin, L., Morrison, A.: Skills, Organisational Performance and Economic Activity in the Hospitality Industry: A Literature Review. Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Skills, Knowledge, and Organizational Performance (SKOPE). University of Oxford and Warwick, Oxford (2002)

Google Scholar

Schneider, B., Godfrey, E.G., Hayes, S.H., Huang, M., Lim, M., Nishii, L.H., Raver, J.L., Ziegert, J.C.: The human side of strategy: employee experiences of strategic alignment in a service organization. Organ. Dyn. 32 , 122–141 (2003)

Cikes, V., Ribaric, H.M., Crnjar, K.: The determinants and outcomes of absence behavior: a systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. 7 (8), 120 (2018)

Ramdass, K.: Absenteeism—a major inhibitor of productivity in South Africa: a clothing industry perspective. In: 2017 Proceedings of PICMET 17: Technology Management for Interconnected World, United States, pp. 1–7 (2017)

Mathis, R.L., Jackson, J.H.: Human Resource Management, 12th edn. International Student Edition, Mason, Thomson South-Western (2004)

Cucchiella, F., Gastaldi, M., Ranieri, L.: Managing Absenteeism in the workplace: the case of an Italian multiutility company. Proc.-Soc. Behav. Sci. 150 , 1157–1166 (2014)

Pizam, A., Thornburg, S.W.: Absenteeism and voluntary turnover in central Florida hotels: a pilot study. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 19 , 211–217 (2000)

March, J.G., Herbert, A.S.: Organizations, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York (1958)

Blau, G.J.: Relationship of extrinsic, intrinsic, and demographic predictors to various types of withdrawal behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 70 , 442–450 (1985)

Cheloha, R.S., Farr, J.L.: Absenteeism, job involvement, and job satisfaction in an organizational setting. J. Appl. Psychol. 65 , 467–473 (1980)

Steel, R.P.: Methodological and operational issues in the construction of absence variables. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 13 , 243–251 (2003)

Chadwick-Jones, J.K., Colin, A.B., Nicholson, N., Sheppard, C.: Absence measures: their reliability and stability in an industrial setting. Pers. Psychol. 24 , 463–470 (1971)

MacDonald, C.: Understanding participatory action research: a qualitative research methodology option. Can. J. Action Res. 13 (2), 34–50 (2012)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

DEGEIT, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Alfredo Silva

DEGEIT, University GOVCOPP Research Centre, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Ana Luísa Ramos

CIDEM, Research Center of Mechanical Engineering, Porto, Portugal

Marlene Brito

DEM, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

António Ramos

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Alfredo Silva or Marlene Brito .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Production and Systems, School of Engineering, University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

Pedro M. Arezes

Department of Mining Engineering, Engineering Faculty, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

J. Santos Baptista

Mónica P. Barroso

Paula Carneiro

Patrício Cordeiro

Nélson Costa

Faculty of Human Kinetics, University of Lisbon, Cruz Quebrada–Dafundo, Portugal

Rui B. Melo

A. Sérgio Miguel

Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Gonçalo Perestrelo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Silva, A., Ramos, A.L., Brito, M., Ramos, A. (2020). A Diagnostic Analysis of Absenteeism—A Case Study in a Portuguese Cork Industry. In: Arezes, P., et al. Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health II. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol 277. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41486-3_85

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41486-3_85

Published : 21 February 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-41485-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-41486-3

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, leadership and its influence on employee absenteeism: a qualitative review.

Management Decision

ISSN : 0025-1747

Article publication date: 11 March 2022

Issue publication date: 10 November 2022

The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the last 50 years of empirical research on leaders' influence on employee absenteeism. Furthermore, the aim is to direct future management research by identifying what is still undiscovered regarding areas such as leadership concepts, measurements of absenteeism, methodology and country-specific contexts of the studies.

Design/methodology/approach

This is a qualitative review which is suitable as the literature on leadership and employee absenteeism is still emergent and characterized by heterogeneity in terms of operationalization of absenteeism and leadership concepts, respectively, as well as types of analyses.

This review identifies different aspects of leadership affecting employee absence, i.e. leadership behaviours (i.e. task, relational, change, passive), leadership styles, leaders' social modelling and attitudes, and leaders' management of health and absence. Furthermore, a number of gaps in extant research are identified as well as a research agenda is provided.

Originality/value

This review is the first of its kind and hence contributes more profound insights into leaders' influence on employee absenteeism. Leaders as a factor explaining employee absenteeism have only played a minor role, in large theoretical contributions, and the exact behaviour and style is not elaborated much in the literature. Thus, this paper provides practical and theoretical considerations over the role of leaders in shaping employee absenteeism.

- Employee absenteeism

- Qualitative review

Løkke, A.-K. (2022), "Leadership and its influence on employee absenteeism: a qualitative review", Management Decision , Vol. 60 No. 11, pp. 2990-3018. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-05-2021-0693

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Administrative Intensity at UW-Madison

Junjie Guo, Kim Ruhl and Ananth Seshadri

Executive Summary:

The fourth white paper in the series presents measures of administrative intensity for UW-Madison and comparisons with peer institutions. The issue of administrative costs in higher education has been at the forefront of a lot of debates concerning the efficiency of allocation of resources within higher education.

Read White Paper #4

- Facebook Logo

- Twitter Logo

- Linkedin Logo

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Measuring school absenteeism: administrative attendance data collected by schools differ from self-reports in systematic ways.

- 1 Research Group TOR, Department of Sociology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

- 2 Centre for Educational Effectiveness and Evaluation, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

In order to use attendance monitoring within an integrative strategy for preventing, assessing and addressing cases of youth with school absenteeism, we need to know whether the attendance data collected by schools cover all students with (emerging) school attendance problems (SAPs). The current article addresses this issue by comparing administrative attendance data collected by schools with self-reported attendance data from the same group of students (age 15–16) in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium ( N = 4344). We seek to answer the following question: does an estimation of unauthorized absenteeism based on attendance data as collected by schools through electronic registration differ from self-reported unauthorized absenteeism and, if so, are the differences between administrative and self-reported unauthorized absenteeism systematic? Our results revealed a weak association between self-reported unauthorized school absenteeism and registered unauthorized school absenteeism. Boys, students in technical and vocational tracks and students who speak a foreign language at home, with a less-educated mother and who receive a school allowance, received more registered unauthorized absences than they reported themselves. In addition, pupils with school refusal and who were often authorized absent from school received more registered unauthorized absences compared to their self-reported unauthorized school absenteeism. In the discussion, we elaborate on the implications of our findings.

Introduction

School absenteeism is a serious problem among youth. Youth with school attendance problems (SAPs) report lower academic efficacy, poorer academic performances, more anxiety, more symptoms of depression and less self-esteem ( Kearney, 2008 ; Reid, 2014 ). In addition, school absenteeism is often embedded in a broader pattern of social deviant behavior: youth with attendance problems have an increased risk of stealing, getting involved in vandalism and are more likely to partake in behaviors at the risk of their health (e.g., smoking, substance use; Maynard et al., 2012 ; Reid, 2014 ). These specific problems may in turn reinforce long-term SAP and give rise to a vicious circle eventually increasing the risk of early school leaving and later unemployment ( Archambault et al., 2009 ; Rumberger, 2011 ; Cabus and De Witte, 2015 ). Hence, early identification of youths with relatively new absentee problems is paramount to prevent more severe and enduring SAPs ( Kearney and Graczyk, 2014 ; Ingul et al., 2019 ).

In order to optimize identification of youth with (relatively new) absentee problems, many countries invest in attendance monitoring through centralized student management systems. Daily monitoring of students’ attendance is used to ensure fast detection and to enable schools to adopt strategies to intervene when youth have emerging SAPs. More recently, it has been emphasized that in order to maximize early identification of attendance problems, schools need to make better use of their data by also analyzing their collected attendance data ( Reid, 2014 ; Kearney, 2016 ; Chu et al., 2019 ). Reid (2014) , for example, stresses that an analysis of school attendance data enables schools to identify the causes and school-specific issues of absenteeism. Attendance data can be produced weekly, monthly or yearly and can indicate trends between classes and types of attendance (e.g., seasonal attendance, luxury absenteeism). By using this information, schools can optimize early interventions and create tailor-made strategies. Similarly, Chu et al. (2019) assert that actively analyzing attendance data enables schools to provide attendance feedback to key stakeholders such as students, parents, and counselors. Accordingly, they can use this data to create individualized intervention plans for students or use the data as part of comprehensive school interventions. The extent to which schools maximize the potential of attendance data, however, depends on certain preconditions. This obviously includes the degree of data literacy of the school actors involved ( Mandinach, 2012 ), but also a good understanding of the collected data. Understanding the nature of absenteeism at a school is a crucial first step to appoint more targeted, individualized interventions. To ensure that this process runs efficiently, however, it is important to assess whether certain groups of students are more or less likely to be present in these registration data, compared to information they report themselves. Indeed, in order to apply attendance monitoring within an integrative strategy for preventing, assessing and addressing cases of youth with school absenteeism (cf. Kearney, 2016 ), we need to know whether the attendance data collected by schools covers all students with (emerging) SAPs.

This article contributes to the aforementioned literature by comparing administrative attendance data collected by schools with self-reported attendance data from the same group of students in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium ( N = 4344). As far as we know, this study is novel in investigating this relationship. The key questions concern whether an estimation of unauthorized absenteeism based on attendance data as collected by schools through electronic registration differs from self-reported unauthorized absenteeism. And if so, whether any differences between administrative and self-reported unauthorized absenteeism are systematic? In other words, are there specific groups of students who are systematically under or overrepresented according to the chosen measurement technique? The latter would indicate that certain types of (emerging) SAPs are more or less prevalent in administrative attendance data when compared to self-reported data.

Strengths and Limitations of Administrative and Self-Report Attendance Data

School absenteeism is generally measured by means of one out of three different types of data collection strategies: surveys, registration data from school administration or through secondary sources (parents, peers). In this study we focus on self-reported school absenteeism and administrative school attendance data. This section briefly reviews the strengths and limitations of both measurement techniques. Rather than providing a general overview of the strengths and limitations of the data types, we primarily aim to inventory reasons to expect that attendance data as collected by schools (will not) cover all students with (emerging) SAPs. This focus on registration data is justified by the fact if schools aim to include data in their school policies, they are most likely to rely on registration data. Furthermore, we want to know which specific groups of students are more or less likely to be present according to the measurement technique.

Administrative Data on School Attendance

Analyses on administrative data of school attendance rely on absences that are recorded by the school staff. In most countries, teachers register school attendance for all students per lesson or per (half) school day. Attendance is monitored by administrative assistants who define whether an absence is (un)authorized and notify school counselors when students exceed a certain threshold of unauthorized absences. Obviously, only those absences that are effectively detected by the school (and defined as unauthorized) are included in administrative data. One strength of administrative data is that they are collected for all students. This implies, for example, that unlike self-reported survey data (see next section), administrative data on school attendance also contains information on groups of students who represent only a very small percentage of the total student population (i.e., students with a specific ethnic background or special needs). Nevertheless, administrative data suffer from at least two limitations.

First, in certain situations, a registered unauthorized absence has little to do with a young person not going to school while having the opportunity to do so. This concerns, for example, absences due to illness which are not justified through a doctor’s note and/or parental consent for the absence. In particular, the latter might apply to children living in low income households due to the financial costs of medical consultation. In such cases, administrative school attendance data are likely to overestimate the level of unauthorized absences from school in a non-random way.

Secondly, there are also indications that official statistics underestimate the amount of absenteeism which is taking place in schools because certain categories of absenteeism remain undetected or are falsely reported as authorized. The first category concerns pre-planned school absenteeism during specific lessons or with specific teachers for which the risk of getting caught is known to be limited. In this context, Reid (1999) distinguishes between specific lessons absenteeism and post-registration truancy. Specific lesson absenteeism refers to the chronic skipping of a specific subject area due to content or the instructor. According to Reid (1999) , specific lesson absences originate from a negative student-teacher relationship or dislike of the subject. Keppens and Spruyt (2016 , 2017a) argue that it may also be due to an estimated low probability of getting caught whereby some students take advantage of teachers who are sloppier in the registration of absences. Post-registration truancy refers to truancy that occurs after students are registered as being present at school ( O’Keefe, 1993 ; Reid, 1999 ; Keppens and Spruyt, 2016 ). Hence, post-registration truancy can be considered a specific type of pre-planned specific lesson absence.

A second category of a type of school absenteeism that is more likely to be registered as an authorized absence from school is due to parental consent for the absence. In the first place, this concerns school withdrawal, defined by Heyne et al. (2019 , p. 23) as an absence which is (a) not concealed from the parent(s) and (b) attributable to active parental effort to keep the young person at home, or little or no parental effort to get the young person to school. Absenteeism with parents’ knowledge but not consent is called school refusal. The latter refers to a refusal to attend school (a) in conjunction with emotional distress, (b) with parents’ knowledge, (c) without display of antisocial behavior or (d) when parents have made reasonable efforts or express their intention to secure attendance at school ( Heyne et al., 2019 , pp. 22–23).

Self-Reported Attendance Data

In the literature, school absenteeism is most often measured through self-reported data ( Maynard et al., 2012 ; Havik et al., 2015 ; Keppens and Spruyt, 2016 ), irrespective of whether it is combined with reports from the parents ( Kearney and Silverman, 1993 ; Kearney, 2002 ). In these studies, young people themselves indicate whether or not they missed school. One of the main strengths of the self-report method is the capacity to investigate the etiology of school absenteeism by means of collecting comprehensive information on individual, familial, school and societal characteristics and influences. The self-report method allows differentiation between different types (e.g., truancy, school refusal, specific lesson absence, school withdrawal), and reasons for (the maintenance of) SAPs ( Kearney, 2007 ; Keppens and Spruyt, 2016 ; Heyne et al., 2019 ). This enables one to grasp certain types of school absenteeism (e.g., pre-planned truancy, school refusal) which are difficult to detect in registration data. Hence, one could argue that the measurement of school absenteeism through the self-report method complements administrative school attendance data. However, authors also indicate that self-reported measures of school absenteeism are plagued with a number of problems, resulting in under- or over-reporting.

First, measuring unauthorized school absenteeism through the self-report method may introduce problems because the aim is to gauge behavior that is deviant or delinquent. For example, truancy, defined by Heyne et al. (2019 , p. 23) as an absence which occurs (a) when a young person is absent from school for an entire day or part of the day, or at school but absent from the proper location, (b) without the permission of the school authorities and (c) when the young person tries to conceal the absence from their parents, is considered a status offense ( Zhang et al., 2007 ). Hence, respondents are more likely to conceal or fail to recall their truancy out of fear of the consequences, resulting in an underestimation of the actual truancy rate. In this context, research suggests that this underestimation is structurally higher among ethnic minority youth ( Kirk, 2006 ; van Batenburg-Eddes et al., 2012 ). For example, a Dutch study investigating the discrepancy between self-reported juvenile delinquency and official police statistics found that, in particular, Moroccan youth are less inclined to admit delinquent behavior. The study also showed that this is due to (a) discrimination by the police and (b) a higher level of suspicion toward the authorities due to higher feelings of stigmatization ( van Batenburg-Eddes et al., 2012 ). The same reasoning may apply to the self-reporting of unauthorized absenteeism, and particularly truancy. Zhang (2003) , for example, problematizes the subjectivity in authorizing absences since the attendance regulations stipulate that it is up to the school staff to decide which absence should be authorized. In these circumstances, it is plausible that certain students (whose school absenteeism is accompanied by other school misbehavior) or certain types of absences (truancy) are more easily registered as unauthorized than others. Skiba et al. (2011) , for example, show that ethnic minorities in the United States are more likely to be referred for truancy as compared to their white peers (African American youths in grade 6 to 9 are 4.40 times more likely to be referred for truancy than their white peers; Hispanic/Latino youth in grade 6 to grade 9 are 2.44 times more likely to be referred for truancy than their white peers). Skiba et al. (2011) also demonstrated that ethnic minorities are more likely than their white peers to receive expulsion or out of school suspension as a consequence of referred truancy. Hence, ethnic minorities might (compared to their peers without a migration background) be overrepresented in administrative data on absenteeism because of discrimination by the school staff. However, at the same time, ethnic minorities might also be underrepresented in the self-reported school absenteeism data due to feelings of suspicion toward the school authorities when filling in self-reported questionnaires on deviant behavior.

A second limitation of the self-report technique is that it relies on students’ recollections of their absenteeism and this might undermine the reliability of the data. This applies in particular to self-report measures that rely on longer time frames. The longer this period, the greater the chance that the self-reported absenteeism will deviate from the real absenteeism rate ( Stone et al., 2000 ; Kirk, 2006 ). However, it should also be noted that self-reported measures that use a shorter reference period to measure absenteeism (for example, 2 weeks) may lead to an underestimation of school absenteeism. When the reference period is short, there will likely be an underreporting of students who are only absent a few times a year ( Keppens and Spruyt, 2017b ).

The Current Study

The preceding arguments suggest that self-reported data and administrative data on school absenteeism are each associated with some advantages and disadvantages due to their specificity. The added value of self-reported data on school absenteeism is that it enables stakeholders to assess absenteeism in more detail. Certain types of absences that remain invisible in administrative data on absenteeism are more likely to be grasped with the self-report technique. In this way, self-reported data on school absenteeism provide an indication of the extent to which administrative data on absenteeism cover all students with (emerging) SAPs. Against this background, this paper is the first study that compares self-reported data on school absenteeism with administrative data of unauthorized absences among (the same group of) students from the fourth year of secondary education in Flanders. More specifically, we investigate: (1) the extent to which self-reported data on school absenteeism and administrative data of unauthorized absences gauge the same behavior, and (2) the extent to which possible discrepancies are related to the type of school absenteeism (e.g., truancy, school refusal, school withdrawal, pre-planned truancy and authorized school absenteeism) and students’ characteristics (in particular, ethnicity and SES).

Materials and Methods

Study design.

To answer our research questions, we merged self-reported data on school absenteeism from the longitudinal LiSO (Educational Trajectories in Secondary Education) project with data from the administrative database on absences from the Flemish Ministry of Education and Training (named DISCIMUS in the remainder of this paper).

The LiSO project follows a cohort of 6457 students in 57 schools who started secondary education in the school year 2013–2014 ( Stevens et al., 2015 ). A regional sampling strategy was used whereby nearly all students in the targeted cohort who attended school in the target geographic region were included in the study ( Dockx et al., 2019 ). For the present study, data were used from wave 4 (T4) which was gathered at the end of the fourth year (May 2017) of secondary education (age 15–16). T4 is the only wave that included items gauging self-reported school absenteeism. The total sample of students in T4 consisted of 6545 students in 53 schools. Within this sample, 4344 students completed the questionnaire in a valid way resulting in a total response rate of 66.69%.

Registration data on absences among all students in primary and secondary education are collected by the Flemish Agency for Educational services (AGODI). In Flanders, school attendance is registered twice a day. There are many reasons why a student is absent from school. Absences due to illness (and authorized by a doctor or through a parental note) 1 , a funeral of a relative or religious holidays are authorized. When a student has no justified reason for his/her absence (i.e., has an unauthorized absence from school), s/he receives, per half school day, a so-called “B-code”. Schools automatically exchange these registered absences (all absences including unauthorized absences) within a centralized database (DISCIMUS). This enables the Flemish Ministry of Education and Training to link the collected data to other student characteristics. At any time, schools can request the absences they have registered. As a result, the registration data on school absenteeism in Flanders is not only used to intervene at the level of the students 2 , but also to gain insight into the distribution of all absences across different classes and school years. In general, Flanders can be considered as one of the forerunners in Europe when it comes to the accurate and systematic collection of data on school absenteeism among students who follow compulsory education ( European Commission, 2013 ).

In DISCIMUS, each student has a unique identification number. In this paper, we used this unique identification number to merge data from the DISCIMUS database with data from the LiSO database. Only registrations of unauthorized absences that occurred before filling in the LiSO questionnaire were considered.

Because this study involved students in Flemish secondary education and was an initiative of the Flemish government, approval was required of the Belgian Commissie voor de bescherming van de persoonlijke levenssfeer (Commission for the protection of the personal privacy). The Commission approved the data collection of the LiSO-project. Parents and students have been informed yearly, with a personal letter and the schoolreglement (school charter). A schoolreglement in Flanders is a document that contains the specific regulations of the school and its pedagogical project. It needs to be signed by the parents and the student to declare that they agree with the regulations and pedagogical project of the school. By signing this document, they also agree to participate with the LiSO-project and other studies that the school had chosen to participate in.

However, even after signing to agree with the school charter, parents and students can still choose to opt out of a study. This procedure was also approved by the Commissie voor de bescherming van de persoonlijke levenssfeer. The linking of the data of the LiSO-project and DISCIMUS poses no specific issues, for the Commissie voor de bescherming van de persoonlijke levenssfeer approved that the data can be linked to other datasets. Furthermore, parents and students were informed in the personal letter and the school charter that such linking of data would occur.

Questionnaire Data

Self-reported unauthorized school absenteeism was measured through the following question: “How many times did you skip school without a valid reason in the current school year?” Students who reported to have skipped school at least once were asked about whether their parents knew about the absence and if so whether they approved the absence. These characteristics allowed us to differentiate between three types of SAP: truancy, school refusal and school withdrawal ( Heyne et al., 2019 ). In this study, and following Heyne et al. (2019) , unauthorized absences that are concealed from the parents were labeled as truancy . Unauthorized absences that occurred with knowledge of parents, but without consent were labeled as school refusal . Unauthorized absences that occurred with approval of the parents were labeled as school withdrawal . In addition, information was gathered on pre-planned truancy and self-reported authorized absenteeism. Pre-planned truancy was measured by asking students who reported to have skipped at least once whether their unauthorized absences were discovered by the school staff. Self-reported authorized absenteeism was measured by asking: “How often were you absent from school for a valid reason this school year due to family or personal reasons (e.g., death of a friend or family member) or illness (I had a valid note from my parents or the doctor)”. Respondents answered on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (more than 10 times).

Administrative Data

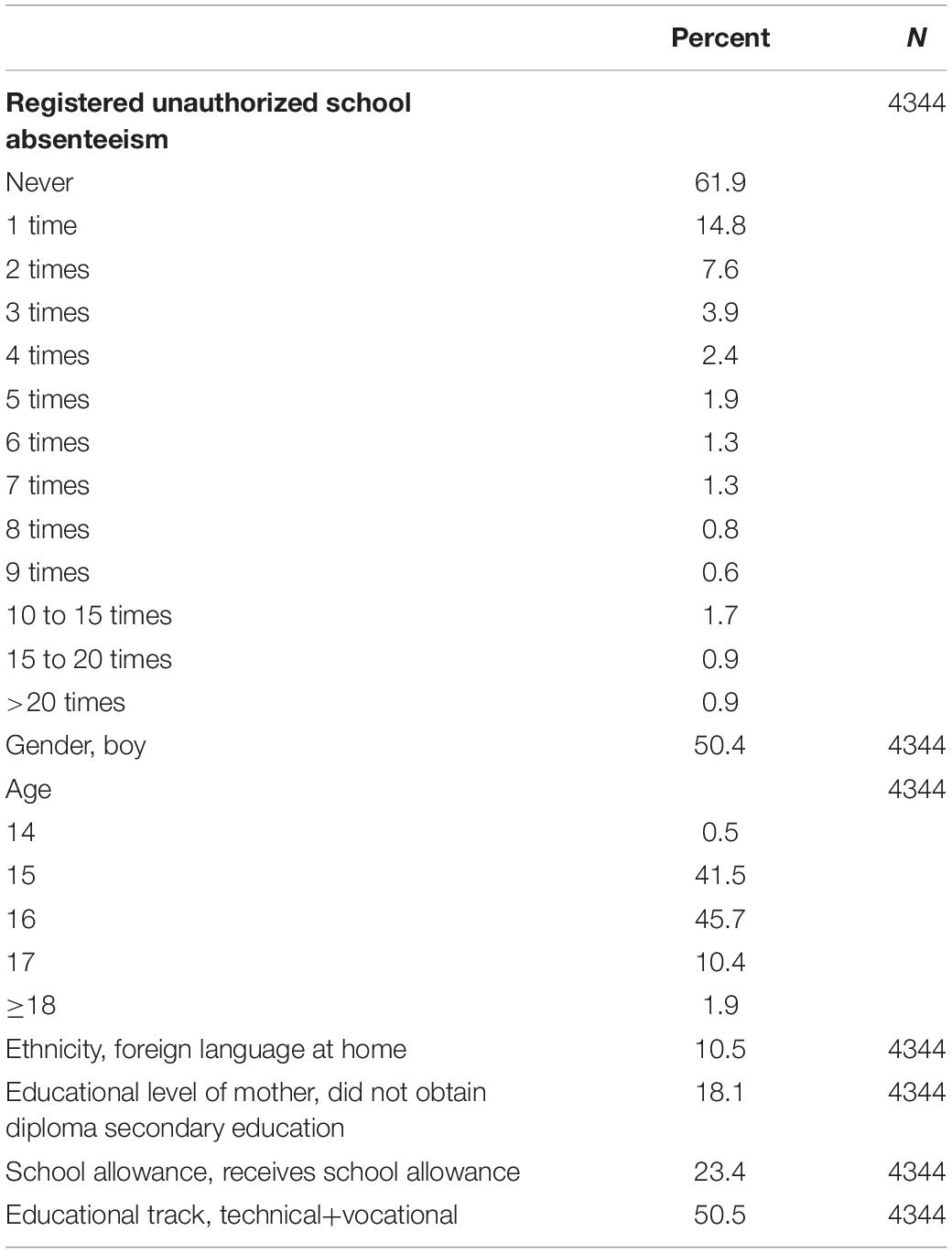

Registered unauthorized absences are measured through the number of “B-codes” in the DISCIMUS dataset. A student receives a B-code for each half school day of unauthorized absence. In other words, a student who had an unauthorized absence for a whole school day receives 2 B-codes. The school year 2016–2017 in fulltime secondary education counted 316 half school days, which equals the maximum number of B-codes a student can receive for that school year. The rate of B-codes among the students in our sample ranged from 0 to 101 ( M = 2.41, SD = 6.75). To compare the registered and self-reported unauthorized absences, the following procedure was used. First, every day on which a student was absent for the whole school day (i.e., for which s/he received 2 B-codes) was recoded to 1. Since the self-reported measure of unauthorized absenteeism asks respondents to report how many times they skipped school, students who were absent for a whole school day will likely report this as one time. Next, we recoded the number of B-codes to match the categories used in the self-report measure: none, once, 2 times, 3 times, 4 times, 5 times, 6 times, 7 times, 8 times, 9 times, 10 to 15 times, 15 to 20 times, or more than 20 times. In addition, information on the characteristics of the students were obtained, including gender, ethnicity (speaks foreign language at home), age, educational track (general/arts or technical/vocational) and SES. The latter is measured through the educational level of the mother and whether the student receives an education allowance.

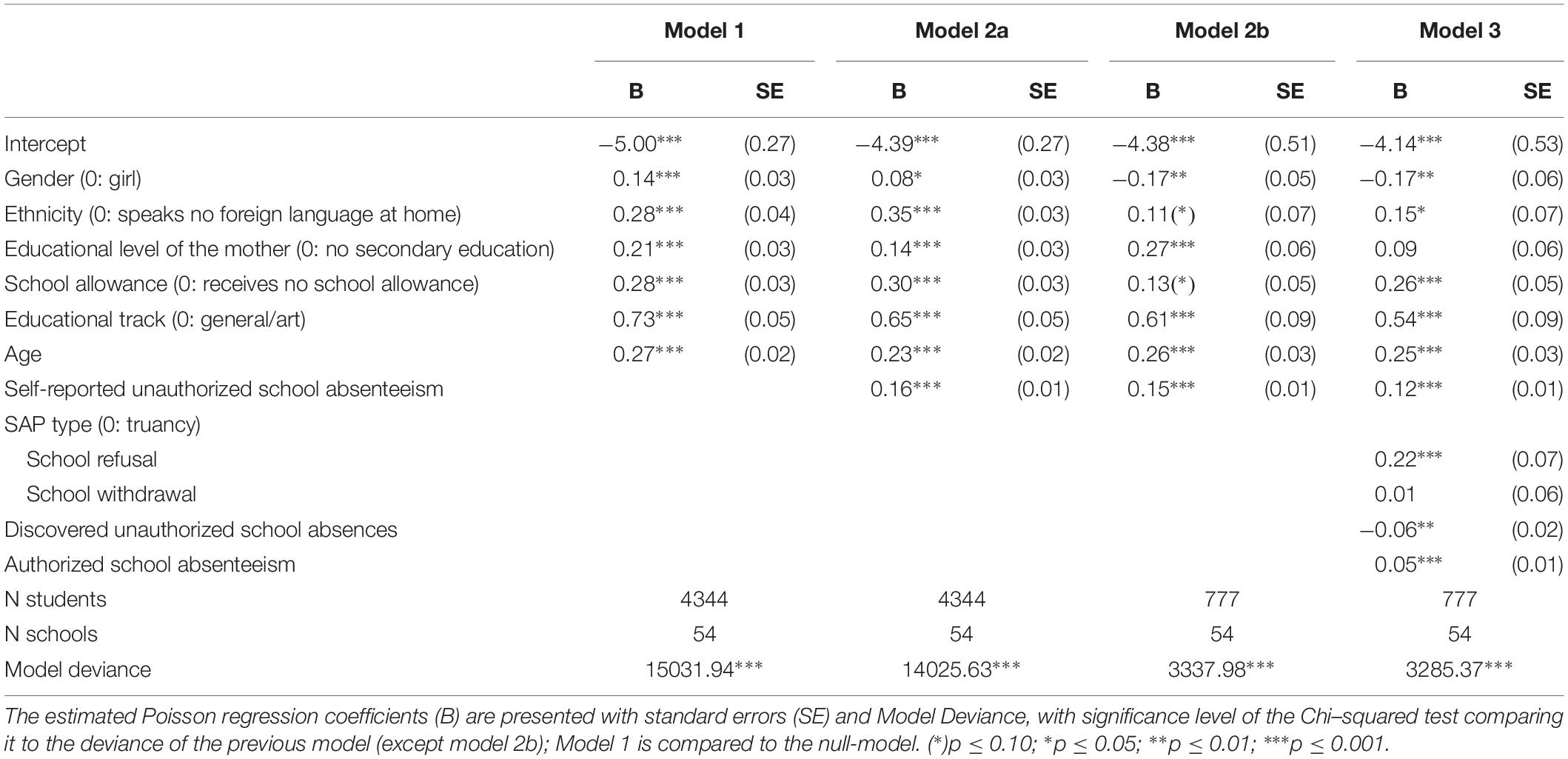

Statistical Analyses

In this study we conducted Poisson multilevel regression analyses (with STATA 14) with the prevalence of registered unauthorized school absences as dependent variable to assess the relationship between self-reported and registered unauthorized school absenteeism. A Poisson model is the most suitable technique since our measures of unauthorized school absenteeism are count variables that are bounded by zero (one cannot be absent from school less than 0 times) and not normally distributed ( Cameron and Trivedi, 2013 ). The multilevel structure enabled us to control for differences between schools (e.g., whether schools are more or less strict in their registration and detection of unauthorized absences). The first model included the sociodemographic variables gender, ethnicity, age, educational level and SES that are known to relate to school absenteeism ( Kearney, 2008 ; Reid, 2014 ). In the second model we added the prevalence of self-reported unauthorized school absenteeism. This allowed us to assess whether the administrative data under or overestimated the degree of unauthorized school absenteeism of particular social groups, compared to the self-report data. The latter would be the case when some of the sociodemographic variables remained significant after taking into account the self-reported absences. Model 2a examines these associations for our total sample ( N = 4344). Model 2b examines these associations only for those students who reported to have an unauthorized absence from school at least once ( N = 777). This subsample included students who had valid answers on the self-reported question on unauthorized school absenteeism and all subsequent measures concerning the type of SAPs. In the third model, we analyzed whether the administrative data under or overestimated (when compared to the self-report data) the degree of unauthorized school absenteeism of certain types of school absenteeism by adding the typology of SAPs, pre-planned truancy and authorized school absenteeism.

Non-response

For the non-response analysis, students who did not (adequately) complete the questionnaire were compared with students who did. Students who did not complete the questionnaire could not because they were absent when their classmates filled in the questionnaires. Some schools were also less motivated to give students sufficient time to properly fill out the questionnaire. Students who failed to complete the questionnaire had statistically more unauthorized absences from school than students who completed a questionnaire, respectively, 13.51 to 2.62 [ F (1) = 737.58, p < 0.001].

Tables 1 , 2 present the characteristics of the study population based upon, respectively, the questionnaire data and the administrative data: 50.4% of the participants were boys, 10.5% spoke a foreign language at home, 18.1% had a less educated mother (not finished secondary education), 23.4% received a school allowance and 50.5% was enrolled in technical or vocational education. The prevalence of registered unauthorized school absenteeism was higher (39.1%) than the prevalence of self-reported school absenteeism (19.2%). Among the group of students who reported to have at least once been unauthorized absent from school, 49.4% could be categorized as truancy, 17.4% as school refusal and 33.2% as school withdrawal. Additionally, 57.8% of the students reported that their unauthorized school absenteeism was never discovered.

Table 1. Sample characteristics based upon questionnaire data.

Table 2. Sample characteristics based upon administrative data.

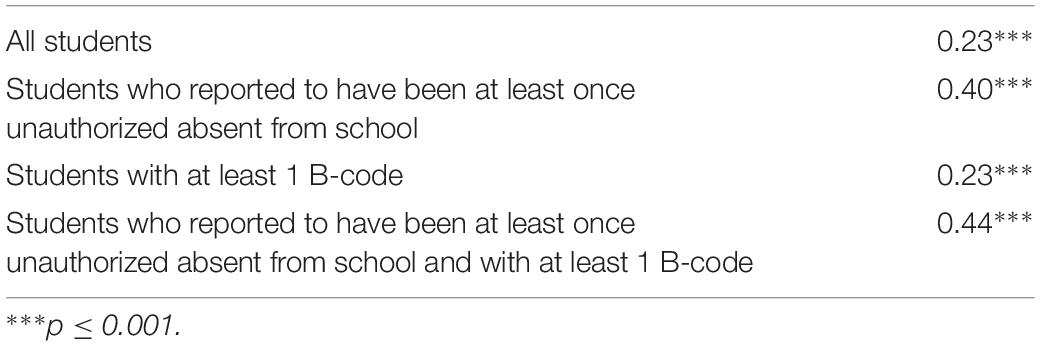

Table 3 shows the correlation between self-reported and registered unauthorized school absenteeism and helps to answer our first research question. We observed a weak but significant positive correlation ( r s = 0.23, p < 0.001). The strength of this correlation increased when it was re-estimated among the subsample of students who reported to have an unauthorized absence from school at least once ( r s = 0.40, p < 0.001). The same observation applies for the group of students who reported to have at least one unauthorized absence from school and who have been registered with at least 1 B-code ( r s = 0.44, p < 0.001). This indicates that the rather weak association between self-reported and registered unauthorized school absenteeism is mainly due to students who have been registered with at least one B-code but do not report to have skipped school. When we omitted this group of students, we found a medium-strong association between self-reported and registered unauthorized school absenteeism.

Table 3. Spearman correlation coefficients between self-reported and registered unauthorized school absenteeism.

Multivariate analyses enabled us to answer our second research question: whether the observed discrepancies between registration and self-reported data are related to the type of school absenteeism or the student’s characteristics ( Table 4 ). Model 1 confirms earlier research showing that unauthorized school absenteeism is more prevalent among boys, students in technical and vocational tracks and students who speak a foreign language at home and with a low SES ( Kearney, 2008 ; Reid, 2014 ). Model 2 shows significant associations between all of our inserted student characteristics and registered unauthorized school absenteeism after controlling for self-reported unauthorized school absenteeism. In other words, boys, students in the technical and vocational tracks and students who speak a foreign language at home, with a low-educated mother and who received a school allowance received more B-codes than they reported themselves. The same applied for older students. For model 2b, only students who reported to have an unauthorized absence from school at least once were selected ( N = 777). We observed no large discrepancies between model 2a and 2b, except for gender 3 . Model 3 indicates that, in particular, students with school refusal received more B-codes compared to their self-reported rate of unauthorized school absenteeism. The same applied for authorized school absenteeism. Students who (often) had authorized absences from school received more B-codes compared to their self-reported unauthorized school absenteeism. Finally, we found that students who pre-planned their school absenteeism and reported that their absenteeism had never been discovered received less B-codes when compared to the rate of unauthorized school absenteeism that they reported themselves.

Table 4. Results of Poisson multilevel analyses on the association between registered unauthorized school absenteeism, self-reported unauthorized school absenteeism, student’s characteristics and the type of school absenteeism.