- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

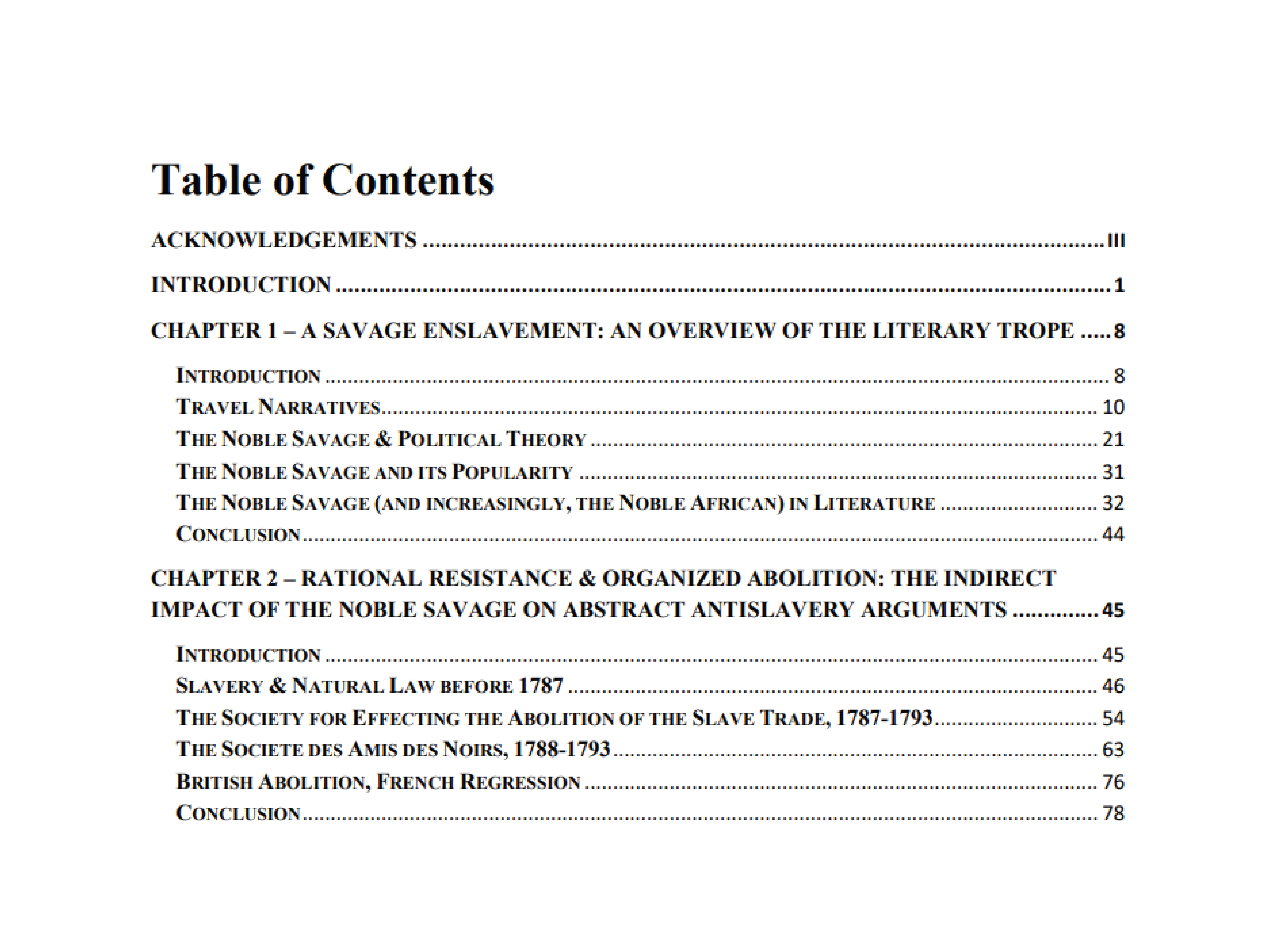

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

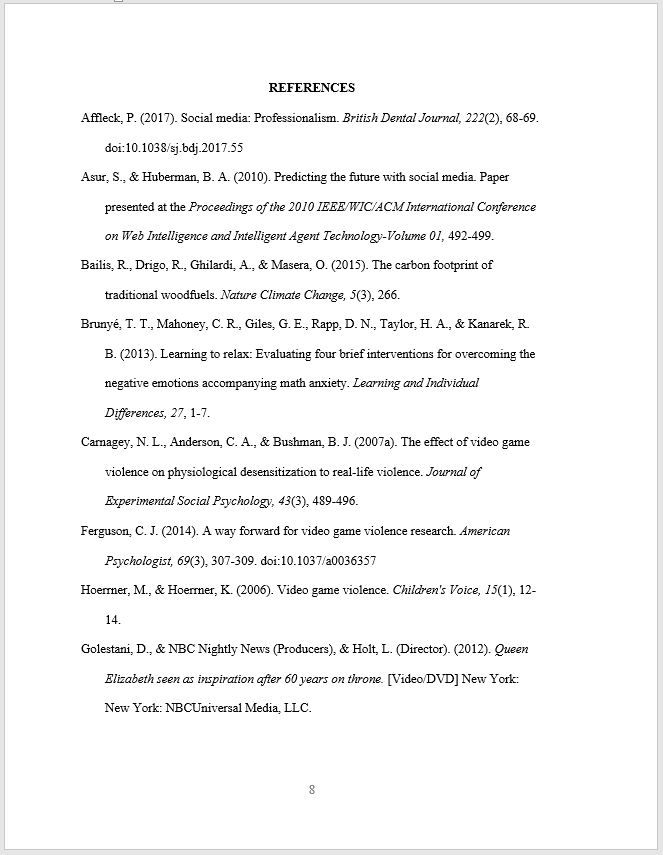

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

AI for Meta-Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

Cybersecurity in Higher Education: Safeguarding Students and Faculty Data

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

HOW TO WRITE A THESIS: Steps by step guide

Introduction

In the academic world, one of the hallmark rites signifying mastery of a course or academic area is the writing of a thesis . Essentially a thesis is a typewritten work, usually 50 to 350 pages in length depending on institutions, discipline, and educational level which is often aimed at addressing a particular problem in a given field.

While a thesis is inadequate to address all the problems in a given field, it is succinct enough to address a specialized aspect of the problem by taking a stance or making a claim on what the resolution of the problem should be. Writing a thesis can be a very daunting task because most times it is the first complex research undertaking for the student. The lack of research and writing skills to write a thesis coupled with fear and a limited time frame are factors that makes the writing of a thesis daunting. However, commitment to excellence on the part of the student combined with some of the techniques and methods that will be discussed below gives a fair chance that the student will be able to deliver an excellent thesis regardless of the subject area, the depth of the research specialization and the daunting amount of materials that must be comprehended(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

Contact us now if you need help with writing your thesis. Check out our services

Visit our facebookpage

What is a thesis?

A thesis is a statement, theory, argument, proposal or proposition, which is put forward as a premise to be maintained or proved. It explains the stand someone takes on an issue and how the person intends to justify the stand. It is always better to pick a topic that will be able to render professional help, a topic that you will be happy to talk about with anybody, a topic you have personal interest and passion for, because when writing a thesis gets frustrating personal interest, happiness and passion coupled with the professional help it will be easier to write a great thesis (see you through the thesis). One has to source for a lot of information concerning the topic one is writing a thesis on in order to know the important question, because for you to take a good stand on an issue you have to study the evidence first.

Qualities of a good thesis

A good thesis has the following qualities

- A good thesis must solve an existing problem in the society, organisation, government among others.

- A good thesis should be contestable, it should propose a point that is arguable which people can agree with or disagree.

- It is specific, clear and focused.

- A good thesis does not use general terms and abstractions.

- The claims of a good thesis should be definable and arguable.

- It anticipates the counter-argument s

- It does not use unclear language

- It avoids the first person. (“In my opinion”)

- A strong thesis should be able to take a stand and not just taking a stand but should be able to justify the stand that is taken, so that the reader will be tempted to ask questions like how or why.

- The thesis should be arguable, contestable, focused, specific, and clear. Make your thesis clear, strong and easy to find.

- The conclusion of a thesis should be based on evidence.

Steps in writing a Thesis

- First, think about good topics and theories that you can write before writing the thesis, then pick a topic. The topic or thesis statement is derived from a review of existing literature in the area of study that the researcher wants to explore. This route is taken when the unknowns in an area of study are not yet defined. Some areas of study have existing problems yearning to be solved and the drafting of the thesis topic or statement revolves around a selection of one of these problems.

- Once you have a good thesis, put it down and draw an outline . The outline is like a map of the whole thesis and it covers more commonly the introduction, literature review, discussion of methodology, discussion of results and the thesis’ conclusions and recommendations. The outline might differ from one institution to another but the one described in the preceding sentence is what is more commonly obtainable. It is imperative at this point to note that the outline drew still requires other mini- outlines for each of the sections mentioned. The outlines and mini- outlines provide a graphical over- view of the whole project and can also be used in allocating the word- count for each section and sub- section based on the overall word- count requirement of the thesis(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

- Literature search. Remember to draw a good outline you need to do literature search to familiarize yourself with the concepts and the works of others. Similarly, to achieve this, you need to read as much material that contains necessary information as you can. There will always be a counter argument for everything so anticipate it because it will help shape your thesis. Read everything you can–academic research, trade literature, and information in the popular press and on the Internet(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

- After getting all the information you need, the knowledge you gathered should help in suggesting the aim of your thesis.

Remember; a thesis is not supposed to be a question or a list, thesis should specific and as clear as possible. The claims of a thesis should be definable and also arguable.

- Then collecting and analyzing data, after data analysis, the result of the analysis should be written and discussed, followed by summary, conclusion, recommendations, list of references and the appendices

- The last step is editing of the thesis and proper spell checking.

Structure of a Thesis

A conventional thesis has five chapters – chapter 1-5 which will be discussed in detail below. However, it is important to state that a thesis is not limited to any chapter or section as the case may be. In fact, a thesis can be five, six, seven or even eight chapters. What determines the number of chapters in a thesis includes institution rules/ guideline, researcher choice, supervisor choice, programme or educational level. In fact, most PhD thesis are usually more than 5 chapters(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

Preliminaries Pages: The preliminaries are the cover page, the title page, the table of contents page, and the abstract.

The introduction: The introduction is the first section and it provides as the name implies an introduction to the thesis. The introduction contains such aspects as the background to the study which provides information on the topic in the context of what is happening in the world as related to the topic. It also discusses the relevance of the topic to society, policies formulated success and failure. The introduction also contains the statement of the problem which is essentially a succinct description of the problem that the thesis want to solve and what the trend will be if the problem is not solved. The concluding part of the statement of problem ends with an outline of the research questions. These are the questions which when answered helps in achieving the aim of the thesis. The third section is the outline of research objectives. Conventionally research objectives re a conversion the research questions into an active statement form. Other parts of the introduction are a discussion of hypotheses (if any), the significance of the study, delimitations, proposed methodology and a discussion of the structure of the study(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The main body includes the following; the literature review, methodology, research results and discussion of the result, the summary, conclusion and recommendations, the list of references and the appendices.

The literature review : The literature review is often the most voluminous aspects of a thesis because it reviews past empirical and theoretical literature about the problem being studied. This section starts by discussing the concepts relevant to the problem as indicated in the topic, the relationship between the concepts and what discoveries have being made on topic based on the choice of methodologies. The validity of the studies reviewed are questioned and findings are compared in order to get a comprehensive picture of the problem. The literature review also discusses the theories and theoretical frameworks that are relevant to the problem, the gaps that are evident in literature and how the thesis being written helps in resolving some of the gaps.

The major importance of Literature review is that it specifies the gap in the existing knowledge (gap in literature). The source of the literature that is being reviewed should be specified. For instance; ‘It has been argued that if the rural youth are to be aware of their community development role they need to be educated’ Effiong, (1992). The author’s name can be at the beginning, end or in between the literature. The literature should be discussed and not just stated (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The methodology: The third section is a discussion of the research methodology adopted in the thesis and touches on aspects such as the research design, the area, population and sample that will be considered for the study as well as the sampling procedure. These aspects are discussed in terms of choice, method and rationale. This section also covers the sub- section of data collection, data analysis and measures of ensuring validity of study. It is the chapter 3. This chapter explains the method used in data collection and data analysis. It explains the methodology adopted and why it is the best method to be used, it also explains every step of data collection and analysis. The data used could be primary data or secondary data. While analysing the data, proper statistical tool should be used in order to fit the stated objectives of the thesis. The statistical tool could be; the spearman rank order correlation, chi square, analysis of variance (ANOVA) etc (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The findings and discussion of result : The next section is a discussion of findings based on the data collection instrumentation used and the objectives or hypotheses of study if any. It is the chapter 4. It is research results. This is the part that describes the research. It shows the result gotten from data that is collected and analysed. It discusses the result and how it relates to your profession.

Summary, Conclusion and Recommendation: This is normally the chapter 5. The last section discusses the summary of the study and the conclusions arrived at based on the findings discussed in the previous section. This section also presents any policy recommendations that the researcher wants to propose (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

References: It cite all ideas, concepts, text, data that are not your own. It is acceptable to put the initials of the individual authors behind their last names. The way single author is referenced is different from the way more than one author is referenced (RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

The appendices; it includes all data in the appendix. Reference data or materials that is not easily available. It includes tables and calculations, List of equipment used for an experiment or details of complicated procedures. If a large number of references are consulted but all are not cited, it may also be included in the appendix. The appendices also contain supportive or complementary information like the questionnaire, the interview schedule, tables and charts while the references section contain an ordered list of all literature, academic and contemporary cited in the thesis. Different schools have their own preferred referencing styles(RE: write a thesis or writing a thesis).

Follow the following steps to achieve successful thesis writing

Start writing early. Do not delay writing until you have finished your project or research. Write complete and concise “Technical Reports” as and when you finish each nugget of work. This way, you will remember everything you did and document it accurately, when the work is still fresh in your mind. This is especially so if your work involves programming.

Spot errors early. A well-written “Technical Report” will force you to think about what you have done, before you move on to something else. If anything is amiss, you will detect it at once and can easily correct it, rather than have to re-visit the work later, when you may be pressured for time and have lost touch with it.

Write your thesis from the inside out. Begin with the chapters on your own experimental work. You will develop confidence in writing them because you know your own work better than anyone else. Once you have overcome the initial inertia, move on to the other chapters.

End with a bang, not a whimper. First things first, and save the best for last. First and last impressions persist. Arrange your chapters so that your first and last experimental chapters are sound and solid.

Write the Introduction after writing the Conclusions. The examiner will read the Introduction first, and then the Conclusions, to see if the promises made in the former are indeed fulfilled in the latter. Ensure that your introduction and Conclusions match.

“No man is an Island”. The critical review of the literature places your work in context. Usually, one third of the PhD thesis is about others’ work; two thirds, what you have done yourself. After a thorough and critical literature review, the PhD candidate must be able to identify the major researchers in the field and make a sound proposal for doctoral research. Estimate the time to write your thesis and then multiply it by three to get the correct estimate. Writing at one stretch is very demanding and it is all too easy to underestimate the time required for it; inflating your first estimate by a factor of three is more realistic.

Punctuating your thesis

Punctuation Good punctuation makes reading easy. The simplest way to find out where to punctuate is to read aloud what you have written. Each time you pause, you should add a punctuation symbol. There are four major pause symbols, arranged below in ascending order of “degree of pause”:

- Comma. Use the comma to indicate a short pause or to separate items in a list. A pair of commas may delimit the beginning and end of a subordinate clause or phrase. Sometimes, this is also done with a pair of “em dashes” which are printed like this:

- Semi-colon. The semi-colon signifies a longer pause than the comma. It separates segments of a sentence that are “further apart” in position, or meaning, but which are nevertheless related. If the ideas were “closer together”, a comma would have been used. It is also used to separate two clauses that may stand on their own but which are too closely related for a colon or full stop to intervene between them.

- Colon. The colon is used before one or more examples of a concept, and whenever items are to be listed in a visually separate fashion. The sentence that introduced the itemized list you are now reading ended in a colon. It may also be used to separate two fairly—but not totally—independent clauses in a sentence.

- Full stop or period. The full stop ends a sentence. If the sentence embodies a question or an exclamation, then, of course, it is ended with a question mark or exclamation mark, respectively. The full stop is also used to terminate abbreviations like etc., (for et cetera), e.g., (for exempli gratia), et al., (for et alia) etc., but not with abbreviations for SI units. The readability of your writing will improve greatly if you take the trouble to learn the basic rules of punctuation given above.

Don't forget to contact us for your thesis and other academic assistance

30 thoughts on “how to write a thesis: steps by step guide”.

wow.. thanks for sharing

Thanks for the article it’s very helpful

It’s very good

This is a great deal

Thank you much respect from here.

Thanks for the education.

thank you for the guide ,is very educating.

What can I say but THANK YOU. I will read your post many times in the future to clear my doubts.

Just came across this insightful article when about to start my PhD program. This is helpful thanks

Very informative website.

I’m really interested in your help. I’m doing my Master and this is my real challenge. I have given my thesis topic already.

chat with us on 09062671816

thanks so much and i will keep on reading till I get much more understanding.

thanks so much i will get in touch with you

Thanks for sharing…

Thanyou for sharing…

You can write my ms thesis

Pingback: My Site

There is perceptibly a bunch to realize about this. I assume you made some nice points in features also.

Loving the information on this web site, you have done great job on the blog posts.

Am happy to come across this web site, thanks a lot may God bless. In few months time I will be back.

anafranil prices

colchicine tablet brand name in india

can i buy colchicine without a prescription

synthroid over the counter online

Wow, marvelous blog format! How long have you been running a blog for? you make running a blog glance easy. The entire look of your site is wonderful, let alone the content!

thank you very much

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Thesis Process

The thesis is an opportunity to work independently on a research project of your own design and contribute to the scholarly literature in your field. You emerge from the thesis process with a solid understanding of how original research is executed and how to best communicate research results. Many students have gone on to publish their research in academic or professional journals.

To ensure affordability, the per-credit tuition rate for the 8-credit thesis is the same as our regular course tuition. There are no additional fees (regular per-credit graduate tuition x 8 credits).

Below are the steps that you need to follow to fulfill the thesis requirement. Please know that through each step, you will receive guidance and mentorship.

1. Determine Your Thesis Topic and Tentative Question

When you have completed between 24 and 32 credits, you work with your assigned research advisor to narrow down your academic interests to a relevant and manageable thesis topic. Log in to MyDCE , then ALB/ALM Community to schedule an appointment with your assigned research advisor via the Degree Candidate Portal.

Thesis Topic Selection

We’ve put together this guide to help frame your thinking about thesis topic selection.

Every effort is made to support your research interests that are grounded in your ALM course work, but faculty guidance is not available for all possible projects. Therefore, revision or a change of thesis topic may be necessary.

- The point about topic selection is particularly pertinent to scientific research that is dependent upon laboratory space, project funding, and access to private databases. It is also critical for our candidates in ALM, liberal arts fields (English, government, history, international relations, psychology, etc.) who are required to have Harvard faculty direct their thesis projects. Review Harvard’s course catalog online ( my.harvard.edu ) to be sure that there are faculty teaching courses related to your thesis topic. If not, you’ll need to choose an alternative topic.

- Your topic choice must be a new area of research for you. Thesis work represents thoughtful engagement in new academic scholarship. You cannot re-purpose prior research. If you want to draw or expand upon your own previous scholarship for a small portion of your thesis, you need to obtain the explicit permission of your research advisor and cite the work in both the proposal and thesis. Violations of this policy will be referred to the Administrative Board.

2. Prepare Prework for the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP) Course or Tutorial

The next step in the process is to prepare and submit Prework in order to gain registration approval for the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP) tutorial or course. The Prework process ensures that you have done enough prior reading and thinking about your thesis topic to benefit from the CTP.

The CTP provides an essential onramp to the thesis, mapping critical issues of research design, such as scope, relevance to the field, prior scholarly debate, methodology, and perhaps, metrics for evaluating impact as well as bench-marking. The CTP identifies and works through potential hurdles to successful thesis completion, allowing the thesis project to get off to a good start.

In addition to preparing, submitting, and having your Prework approved, to be eligible for the CTP, you need to be in good standing, have completed a minimum of 32 degree-applicable credits, including the statistics/research methods requirement (if pertinent to your field). You also need to have completed Engaging in Scholarly Conversation (if pertinent to your field). If you were admitted after 9/1/2023 Engaging in Scholarly Conversation (A and B) is required, if admitted before 9/1/2023 this series is encouraged.

Advising Note for Biology, Biotechnology, and Bioengineering and Nanotechnology Candidates : Thesis projects in these fields are designed to support ongoing scientific research happening in Harvard University, other academic institutions, or life science industry labs and usually these are done under the direction of a principal investigator (PI). Hence, you need to have a thesis director approved by your research advisor prior to submitting CTP prework. Your CTP prework is then framed by the lab’s research. Schedule an appointment with your research advisor a few months in advance of the CTP prework deadlines in order to discuss potential research projects and thesis director assignment.

CTP Prework is sent to our central email box: [email protected] between the following firm deadlines:

- April 1 and June 1 for fall CTP

- September 1 and November 1 for spring CTP.

- August 1 and October 1 for the three-week January session (ALM sustainability candidates only)

- International students who need a student visa to attend Harvard Summer School should submit their prework on January 1, so they can register for the CTP on March 1 and submit timely I-20 paperwork. See international students guidelines for more information.

Your research advisor will provide feedback on your prework submission to gain CTP registration approval. If your prework is not approved after 3 submissions, your research advisor cannot approve your CTP registration. If not approved, you’ll need to take additional time for further revisions, and submit new prework during the next CTP prework submission time period for the following term (if your five-year degree completion deadline allows).

3. Register and Successfully Complete the Crafting the Thesis Proposal Tutorial or Course

Once CTP prework is approved, you register for the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP) course or tutorial as you would any other course. The goal of the CTP is to produce a complete, well-written draft of a proposal containing all of the sections required by your research advisor. Creating an academically strong thesis proposal sets the foundation for a high-quality thesis and helps garner the attention of a well-respected thesis director. The proposal is normally between 15 to 25 pages in length.

The CTP tutorial is not a course in the traditional sense. You work independently on your proposal with your research advisor by submitting multiple proposal drafts and scheduling individual appointments. You need to make self-directed progress on the proposal without special prompting from the research advisor. You receive a final grade of SAT or UNSAT (failing grade).

The CTP for sustainability is a three-week course in the traditional sense and you receive a letter grade, and it must be B- or higher to receive degree credit for the course.

You are expected to incorporate all of your research advisor’s feedback and be fully committed to producing an academically strong proposal leading to a thesis worthy of a Harvard degree. If you are unable to take advice from your research advisor, follow directions, or produce an acceptable proposal, you will not pass the CTP.

Successful CTP completion also includes a check on the proper use of sources according to our academic integrity guidelines. Violations of our academic integrity policy will be referred to the Administrative Board.

Maximum of two attempts . If you don’t pass that CTP, you’ll have — if your five-year, degree-completion date allows — just one more attempt to complete the CTP before being required to withdraw from the program. If you fail the CTP just once and have no more time to complete the degree, your candidacy will automatically expire. Please note that a WD grade counts as an attempt.

If by not passing the CTP you fall into poor academic standing, you will need to take additional degree-applicable courses to return to good standing before enrolling in the CTP for your second and final time, only if your five-year, degree-completion date allows. If you have no more time on your five-year clock, you will be required to withdraw.

Human Subjects

If your thesis, regardless of field, will involve the use of human subjects (e.g., interviews, surveys, observations), you will need to have your research vetted by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (CUHS) of Harvard University. Please review the IRB LIFECYCLE GUIDE located on the CUHS website. Your research advisor will help you prepare a draft copy of the project protocol form that you will need to send to CUHS. The vetting process needs to be started during the CTP tutorial, before a thesis director has been assigned.

4. Thesis Director Assignment and Thesis Registration

We expect you to be registered in thesis soon after CTP completion or within 3 months — no later. You cannot delay. It is critical that once a research project has been approved through the CTP process, the project must commence in a timely fashion to ensure the academic integrity of the thesis process.

Once you (1) successfully complete the CTP and (2) have your proposal officially approved by your research advisor (RA), you move to the thesis director assignment phase. Successful completion of the CTP is not the same as having an officially approved proposal. These are two distinct steps.

If you are a life science student (e.g., biology), your thesis director was identified prior to the CTP, and now you need the thesis director to approve the proposal.

The research advisor places you with a thesis director. Do not approach faculty to ask about directing your thesis. You may suggest names of any potential thesis directors to your research advisor, who will contact them, if they are eligible/available to direct your thesis, after you have an approved thesis proposal.

When a thesis director has been identified or the thesis proposal has been fully vetted by the preassigned life science thesis director, you will receive a letter of authorization from the Assistant Dean of Academic Programs officially approving your thesis work and providing you with instructions on how to register for the eight-credit Master’s Thesis. The letter will also have a tentative graduation date as well as four mandatory thesis submission dates (see Thesis Timetable below).

Continuous Registration Tip: If you want to maintain continued registration from CTP to thesis, you should meet with your RA prior to prework to settle on a workable topic, submit well-documented prework, work diligently throughout the CTP to produce a high-quality proposal that is ready to be matched with a thesis director as soon as the CTP is complete.

Good academic standing. You must be good academic standing to register for the thesis. If not, you’ll need to complete additional courses to bring your GPA up to the 3.0 minimum prior to registration.

Thesis Timetable

The thesis is a 9 to 12 month project that begins after the Crafting the Thesis Proposal (CTP); when your research advisor has approved your proposal and identified a Thesis Director.

The date for the appointment of your Thesis Director determines the graduation cycle that will be automatically assigned to you:

Once registered in the thesis, we will do a 3-month check-in with you and your thesis director to ensure progress is being made. If your thesis director reports little to no progress, the Dean of Academic Programs reserves the right to issue a thesis not complete (TNC) grade (see Thesis Grading below).

As you can see above, you do not submit your thesis all at once at the end, but in four phases: (1) complete draft to TA, (2) final draft to RA for format review and academic integrity check, (3) format approved draft submitted to TA for grading, and (4) upload your 100% complete graded thesis to ETDs.

Due dates for all phases for your assigned graduation cycle cannot be missed. You must submit materials by the date indicated by 5 PM EST (even if the date falls on a weekend). If you are late, you will not be able to graduate during your assigned cycle.

If you need additional time to complete your thesis after the date it is due to the Thesis Director (phase 1), you need to formally request an extension (which needs to be approved by your Director) by emailing that petition to: [email protected] . The maximum allotted time to write your thesis, including any granted extensions of time is 12 months.

Timing Tip: If you want to graduate in May, you should complete the CTP in the fall term two years prior or, if a sustainability student, in the January session one year prior. For example, to graduate in May 2025:

- Complete the CTP in fall 2023 (or in January 2024, if a sustainability student)

- Be assigned a thesis director (TD) in March/April 2024

- Begin the 9-12 month thesis project with TD

- Submit a complete draft of your thesis to your TD by February 1, 2025

- Follow through with all other submission deadlines (April 1, April 15 and May 1 — see table above)

- Graduate in May 2025

5. Conduct Thesis Research

When registered in the thesis, you work diligently and independently, following the advice of your thesis director, in a consistent, regular manner equivalent to full-time academic work to complete the research by your required timeline.

You are required to produce at least 50 pages of text (not including front matter and appendices). Chapter topics (e.g., introduction, background, methods, findings, conclusion) vary by field.

6. Format Review — Required of all Harvard Graduate Students and Part of Your Graduation Requirements

All ALM thesis projects must written in Microsoft Word and follow a specific Harvard University format. A properly formatted thesis is an explicit degree requirement; you cannot graduate without it.

Your research advisor will complete the format review prior to submitting your thesis to your director for final grading according to the Thesis Timetable (see above).

You must use our Microsoft Word ALM Thesis Template or Microsoft ALM Thesis Template Creative Writing (just for creative writing degree candidates). It has all the mandatory thesis formatting built in. Besides saving you a considerable amount of time as you write your thesis, the preprogrammed form ensures that your submitted thesis meets the mandatory style guidelines for margins, font, title page, table of contents, and chapter headings. If you use the template, format review should go smoothly, if not, a delayed graduation is highly likely.

Format review also includes a check on the proper use of sources according to our academic integrity guidelines. Violations of our academic integrity policy will be referred directly to the Administrative Board.

7. Mandatory Thesis Archiving — Required of all Harvard Graduate Students and Part of Your Graduation Requirements

Once your thesis is finalized, meaning that the required grade has been earned and all edits have been completed, you must upload your thesis to Harvard University’s electronic thesis and dissertation submission system (ETDs). Uploading your thesis ETDs is an explicit degree requirement; you cannot graduate without completing this step.

The thesis project will be sent to several downstream systems:

- Your work will be preserved using Harvard’s digital repository DASH (Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard).

- Metadata about your work will be sent to HOLLIS (the Harvard Library catalog).

- Your work will be preserved in Harvard Library’s DRS2 (digital preservation repository).

By submitting work through ETDs @ Harvard you will be signing the Harvard Author Agreement. This license does not constrain your rights to publish your work subsequently. You retain all intellectual property rights.

For more information on Harvard’s open access initiatives, we recommend you view the Director of the Office of Scholarly Communication (OSC), Peter Suber’s brief introduction .

Thesis Grading

You need to earn a grade of B- or higher in the thesis. All standard course letter grades are available to your thesis director. If you fail to complete substantial work on the thesis, you will earn a grade of TNC (thesis not complete). If you have already earned two withdrawal grades, the TNC grade will count as a zero in your cumulative GPA.

If you earn a grade below B-, you will need to petition the Administrative Board for permission to attempt the thesis for a second and final time. The petition process is only available if you are in good academic standing and your five-year, degree-completion deadline allows for more time. Your candidacy will automatically expire if you do not successfully complete the thesis by your required deadline.

If approved for a second attempt, you may be required to develop a new proposal on a different topic by re-enrolling in the CTP and being assigned a different thesis director. Tuition for the second attempt is calculated at the current year’s rate.

If by not passing the thesis you fall into poor academic standing, you’ll need to take additional degree-applicable courses to return to good standing before re-engaging with the thesis process for the second and final time. This is only an option if your five-year, degree-completion deadline allows for more time.

The Board only reviews cases in which extenuating circumstances prevented the successful completion of the thesis.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

1000+ FREE Research Topics & Title Ideas

If you’re at the start of your research journey and are trying to figure out which research topic you want to focus on, you’ve come to the right place. Select your area of interest below to view a comprehensive collection of potential research ideas.

Research Topic FAQs

What (exactly) is a research topic.

A research topic is the subject of a research project or study – for example, a dissertation or thesis. A research topic typically takes the form of a problem to be solved, or a question to be answered.

A good research topic should be specific enough to allow for focused research and analysis. For example, if you are interested in studying the effects of climate change on agriculture, your research topic could focus on how rising temperatures have impacted crop yields in certain regions over time.

To learn more about the basics of developing a research topic, consider our free research topic ideation webinar.

What constitutes a good research topic?

A strong research topic comprises three important qualities : originality, value and feasibility.

- Originality – a good topic explores an original area or takes a novel angle on an existing area of study.

- Value – a strong research topic provides value and makes a contribution, either academically or practically.

- Feasibility – a good research topic needs to be practical and manageable, given the resource constraints you face.

To learn more about what makes for a high-quality research topic, check out this post .

What's the difference between a research topic and research problem?

A research topic and a research problem are two distinct concepts that are often confused. A research topic is a broader label that indicates the focus of the study , while a research problem is an issue or gap in knowledge within the broader field that needs to be addressed.

To illustrate this distinction, consider a student who has chosen “teenage pregnancy in the United Kingdom” as their research topic. This research topic could encompass any number of issues related to teenage pregnancy such as causes, prevention strategies, health outcomes for mothers and babies, etc.

Within this broad category (the research topic) lies potential areas of inquiry that can be explored further – these become the research problems . For example:

- What factors contribute to higher rates of teenage pregnancy in certain communities?

- How do different types of parenting styles affect teen pregnancy rates?

- What interventions have been successful in reducing teenage pregnancies?

Simply put, a key difference between a research topic and a research problem is scope ; the research topic provides an umbrella under which multiple questions can be asked, while the research problem focuses on one specific question or set of questions within that larger context.

How can I find potential research topics for my project?

There are many steps involved in the process of finding and choosing a high-quality research topic for a dissertation or thesis. We cover these steps in detail in this video (also accessible below).

How can I find quality sources for my research topic?

Finding quality sources is an essential step in the topic ideation process. To do this, you should start by researching scholarly journals, books, and other academic publications related to your topic. These sources can provide reliable information on a wide range of topics. Additionally, they may contain data or statistics that can help support your argument or conclusions.

Identifying Relevant Sources

When searching for relevant sources, it’s important to look beyond just published material; try using online databases such as Google Scholar or JSTOR to find articles from reputable journals that have been peer-reviewed by experts in the field.

You can also use search engines like Google or Bing to locate websites with useful information about your topic. However, be sure to evaluate any website before citing it as a source—look for evidence of authorship (such as an “About Us” page) and make sure the content is up-to-date and accurate before relying on it.

Evaluating Sources

Once you’ve identified potential sources for your research project, take some time to evaluate them thoroughly before deciding which ones will best serve your purpose. Consider factors such as author credibility (are they an expert in their field?), publication date (is the source current?), objectivity (does the author present both sides of an issue?) and relevance (how closely does this source relate to my specific topic?).

By researching the current literature on your topic, you can identify potential sources that will help to provide quality information. Once you’ve identified these sources, it’s time to look for a gap in the research and determine what new knowledge could be gained from further study.

How can I find a good research gap?

Finding a strong gap in the literature is an essential step when looking for potential research topics. We explain what research gaps are and how to find them in this post.

How should I evaluate potential research topics/ideas?

When evaluating potential research topics, it is important to consider the factors that make for a strong topic (we discussed these earlier). Specifically:

- Originality

- Feasibility

So, when you have a list of potential topics or ideas, assess each of them in terms of these three criteria. A good topic should take a unique angle, provide value (either to academia or practitioners), and be practical enough for you to pull off, given your limited resources.

Finally, you should also assess whether this project could lead to potential career opportunities such as internships or job offers down the line. Make sure that you are researching something that is relevant enough so that it can benefit your professional development in some way. Additionally, consider how each research topic aligns with your career goals and interests; researching something that you are passionate about can help keep motivation high throughout the process.

How can I assess the feasibility of a research topic?

When evaluating the feasibility and practicality of a research topic, it is important to consider several factors.

First, you should assess whether or not the research topic is within your area of competence. Of course, when you start out, you are not expected to be the world’s leading expert, but do should at least have some foundational knowledge.

Time commitment

When considering a research topic, you should think about how much time will be required for completion. Depending on your field of study, some topics may require more time than others due to their complexity or scope.

Additionally, if you plan on collaborating with other researchers or institutions in order to complete your project, additional considerations must be taken into account such as coordinating schedules and ensuring that all parties involved have adequate resources available.

Resources needed

It’s also critically important to consider what type of resources are necessary in order to conduct the research successfully. This includes physical materials such as lab equipment and chemicals but can also include intangible items like access to certain databases or software programs which may be necessary depending on the nature of your work. Additionally, if there are costs associated with obtaining these materials then this must also be factored into your evaluation process.

Potential risks

It’s important to consider the inherent potential risks for each potential research topic. These can include ethical risks (challenges getting ethical approval), data risks (not being able to access the data you’ll need), technical risks relating to the equipment you’ll use and funding risks (not securing the necessary financial back to undertake the research).

If you’re looking for more information about how to find, evaluate and select research topics for your dissertation or thesis, check out our free webinar here . Alternatively, if you’d like 1:1 help with the topic ideation process, consider our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

- Advisory Board

- Biological Sciences

- Computing & Software Systems

- Engineering & Mathematics

- Physical Sciences

- STEM Inclusivity Awards

- School of STEM contact

- School of STEM Employment

- Student Forms & Resources

- Investigative Biology

- Research & Internships

- Student Organizations

- Friday Harbor Laboratories

- Earth System Science

- Student Projects

- Actuarial Science

- Computer Science & Software Engineering (CSSE)

- Data Science

- Information Technology (IT)

- Marine Biology

- Mathematics

- Neuroscience

- Capstone & Symposium Event

- Undergraduate Policies & Procedures

- CSS Registration & Waitlists

- Getting Started with Computer Science

- Excellence in Cybersecurity Education

- How to Apply

- Core Courses

- Elective Courses

- Project or Thesis

- Computer Engineering

- Power & Energy

- Signal Processing

- Biomedical Systems and Devices

- Microelectronics and Devices

- Wireless, RF/Microwave, and Telecommunications

- Prerequisites guide

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Career Resources

- Previous Quarters

- Division of Biological Sciences Faculty

- Division of Computing & Software Systems Faculty

- Division of Engineering & Mathematics Faculty

- Faculty in Chemistry

- Faculty in Earth System Science

- Faculty in Physics

- Associate Professor with Tenure

- Full Professor

- Teaching Track Faculty

- Promotion and Tenure Public Statement

- Teaching Effectiveness

- Capstones & internships

- Center for Biotechnology Innovation & Training

- National Center of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity

- Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU)

- Faculty Research Projects

- Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) from Heritage University

- Ocean Engineering

- Safety and Security Studies and Modeling in Fluids

- Instrumentation

- Room Access

- Support Services

- Quick Links & Forms

- EE Open lab schedule

Quick Links

- Information Technology

- Commuter Services

- Human Resources

- Campus Safety

Thesis/Project Student Process

The following process applies to all Division of Computing & Software Systems (CSS) graduate students, regardless of degree program (CSSE or CSE) or thesis/project goals.

In general, a thesis is a scholarly written document aimed at an academic audience as a contribution to an existing body of knowledge. A project is aimed at building a connection between academic concepts and the application of those concepts into real-world context.

Before students determine which option to pursue, they should discuss how each option applies to their own individual goals for their degree program with their faculty advisor and the CSS Graduate Advisor.

Step 1: Form a Supervisory Committee

Students who desire to register for their thesis/project credit(s) must first form a committee of faculty who will supervise and grade their efforts and results of their work. A supervisory committee will consist of a student’s Faculty Advisor (who will serve as Committee Chair) and at least 2-3 additional faculty members. At least two of the committee members must be faculty whose primary appointment is in the Computing & Software Systems Division. The Chair of the Committee and at least one-half of the total membership must be members of the graduate faculty.

Students must submit a signed Request to Form a Supervisory Committee to the CSS Graduate Advisor to obtain an entry code to register for the class. Included with the signed form should be a proposal (minimally 3 pages) addressing the questions asked in section 2 of the form. Please follow the proposal guidelines detailed in the link below:

- Proposal Guidelines

- Proposal Rubric

Before submitting the form, students are expected to attend another students CSS master’s project or thesis final examination & defense. View the Thesis/Project Final Exam Schedule .

The deadline for all committee requests is the first day of the seventh week of the quarter PRECEDING the start of a student’s project or thesis coursework . Students should request for specific faculty to staff their Supervisory Committee; however, final staffing assignments of the Supervisory Committee resides with the CSS Division’s Graduate Program Coordinator. Once a supervisory request has been granted, students will receive an email from the CSS Graduate Advisor notifying them of the approved committee and an entry code to register for their thesis/project credit(s). Students are encouraged to submit their request early, to avoid any registration late fees.

Submission Deadlines

- Winter 2024: November 6, 2023

- Spring 2024: February 12, 2024

- Summer 2024: May 6, 2024

- Autumn 2024: July 29, 2024

Step 2: File a Thesis or Project Plan

By the end of the second week of the quarter in which a student is registered for their first capstone credits, the student must submit to their Supervisory Committee a detailed project or thesis plan. The plan should include an updated proposal of the work to be done, a time table listing key milestones and associated deliverables, the quality criteria and specific metrics by which student expects to measure the quality of their result, and the software development lifecycle and processes planned to complete the work. There are no penalties for deviations in the approved plan or failure to meet the estimates in the timetable or failure to achieve the quality goals. The plan simply provides a well-defined start for the remainder of the capstone work. A PDF copy of the approved plan must be submitted by the student to the STEM Graduate Advising Office.

- Winter 2024: January 16, 2024

- Spring 2024: April 8, 2024

- Summer 2024: July 1, 2024

To submit your plan to the STEM Graduate Office, please send your PDF document to [email protected] , with the subject line “Project Plan” or “Thesis Plan”.

Register for CSSSKL 594

A substantial working draft of the capstone research project paper or thesis should be completed by the beginning of the quarter in which you expect to graduate. For this reason, generally, you will enroll in CSSSKL 594 “Scientific Writing for Thesis/Project” during the quarter before you expect to graduate. (For example, to graduate in the spring, you should enroll in 594 in the Winter). Please consult with your supervisory committee chair as to the best timing of this class for the most benefit to you.

Step 3: Communicate Regular Progress Reports with the Supervisory Committee

Throughout the period of enrollment in the thesis/project credit(s), students are expected to lead the effort to regularly update their Supervisory Committee members on their work progress. Students should plan on meeting with their Committee Chair frequently based on the advice from the committee chair (minimally three times in each quarter that they are enrolled for thesis/project credits).

To register for second and subsequent quarters, students should work with their Chair to determine the workload for the upcoming quarter and the number of credits to enroll for. Once the Committee Chair grants permission and confirms the number of credits for the next quarter, the student forwards that permission to the CSS Graduate Advisor, who will issue a new entry code to use for registration. In cases where satisfactory progress is made, the student will be issued of a grade of N (in progress) until the project/thesis is complete.

Students who fail to make appropriate progress in their project/thesis during a quarter may receive a notification from their Chair warning them of lack of progress. If students continue failing to achieve satisfactory progress, Chairs may also choose to issue a grade of NC (No Credit) and move to dissolve the Committee. For full information regarding the project/thesis continuation policy, please see the Academic Progress Policy .

- Guidelines for Status Reports

- Rubric for Status Reports

Step 4: Schedule Final Defense

By 5PM on Thursday of the third week of the quarter that a student is registered for their final thesis/project credits, the student must consult with their supervisory committee members to schedule a defense of their culminating work. Students should work closely with their committee chair to ensure that they are ready for their final examination and defense. The STEM Graduate Advising Office will send students the link to the online scheduling system each quarter to select a time/date for their defense. View details about defense format options and attendance requirements in the Defense Attendance Policy .

Step 5: Apply to Graduate