Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, the return of 70mm.

In this age of multiplexes that boast IMAX, Dolby Cinema and/or RPX auditoriums—large-format, giant-screen temples where both the picture and sound are designated to swallow you up and immerse you in your feature presentation—an old-school, premium film format has been making a comeback.

For most of the 20th century, epic, cinematic productions, from “ Lawrence of Arabia ” to “ Die Hard ,” often had 70mm prints struck and shown in specially equipped theaters for limited engagements. 70mm has a higher resolution than both 35mm and 4K DCP. It captures a bigger, brighter picture, complete with a broader color range and detailed, vibrant visuals. However, by the mid-’90s, showing films in 70mm began to die down, years before showing films on 35mm began to die down. (35mm has also been making a comeback; Alexander Payne ’s “ The Holdovers ” and Todd Haynes ’ “ May December ” are two new films that have been shown in 35mm across the country.)

But even though multiplexes mainly screen movies using digital projection, 70mm films have been slipping back into theaters. Last summer, Christopher Nolan ’s latest, shot-with-IMAX-cameras opus “ Oppenheimer ” was shown in both 70mm and IMAX 70mm formats. IMAX theaters that could still project 70mm film—30 worldwide, 19 nationwide—had sold-out screenings all throughout the season. Those theaters alone raked in $17 million . TikTokers would document the journey they would take just to catch the three-hour biopic in IMAX 70mm. (One person I know attended a Mann’s Chinese Theatre screening at 6am on a Sunday, and that was also sold out.)

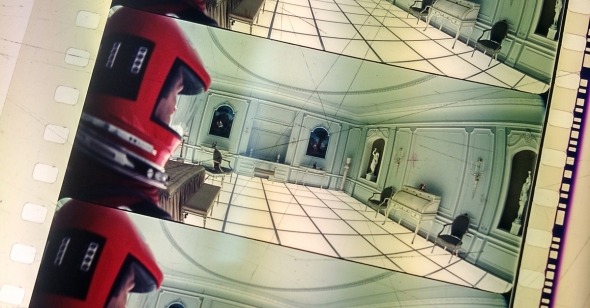

Recently, the IMAX 70mm “Oppenheimer” was brought back for a one-week run at select theaters. But the movie can still be seen in Digital IMAX and 70mm formats. Thomas Hauerslev, a Copenhagen-based editor who’s been running the in70mm.com website since 1999, has seen “Oppenheimer” six times in 70mm, in Denmark, Sweden, and Germany. Even though he hasn’t seen it in IMAX 70mm, watching it in 70mm was still a thrill to behold. “For me,” says Hauerslev, “it’s the mechanical thing because, being a projectionist, I know what it takes to be upstairs in the projection room and run that big film. It’s like moving Hasselblad pictures, because it’s so sharp, it adds a depth to the image. It’s a kind of reality you can’t get anywhere else. It’s the perfect illusion of reality. It’s as if you are in the movie. It’s like looking out of a window.”

More movies are getting the 70mm treatment. Zack Snyder ’s latest Netflix sci-fi epic “Rebel Moon: A Child of Fire” had a week-long, 70mm engagement in a few theaters before it hit the platform. And Ridley Scott ’s “ Napoleon ” played in 70mm in several North American theaters, including the newly reopened Vista Theatre in Hollywood, which is now owned by Quentin Tarantino . (The director is no stranger to the 70mm format; his last two films, “ The Hateful Eight ” and “Once Upon in a Time in Hollywood,” had 70mm engagements.)

Mark E. Anastasio, director of special programming at the Coolidge Corner Theatre in Brookline, Mass., says the theater’s recent, 70mm run of " Napoleon " did quite well. “I don't think any showings were sold out, but we certainly had healthy-sized audiences for the primetime shows,” Anastasio said in an email. “The demographics definitely skewed a bit older and male. People were talking about the 70mm difference! We have a display of 70mm and 35mm frames set up in our box office window to show folks the size difference. And I feel like a lot of the celluloid fans know to come here for these special engagements.”

Nolan and Tarantino aren’t the only film-loving auteurs striking up 70mm prints of their pictures. Last year, Damien Chazelle and Jordan Peele were going around showing their respective, old-Hollywood tributes—“ Babylon ” and “ Nope ”—in 70mm. In previous years, Steven Spielberg (“ Ready Player One ”), Alfonso Cuaron (“ Roma ”), Todd Phillips (“ Joker ”), and Patty Jenkins (“ Wonder Woman ”) have also done 70mm blow/glow-ups.

If you wanna know when this 70mm resurgence truly began, we have to go back over a decade ago. Paul Thomas Anderson shot his 2012 film “ The Master ” in 65mm film stock, which led to the film having 70mm showings during its run. This was mostly thanks to former distribution boss Erik Lomis, who passed away earlier this year . When Lomis was head of distribution at The Weinstein Company (which released “Master”), Anderson convinced him releasing it in 70mm was the way to go. “He explained how the projectors worked, I was humbled,” Anderson said during an event that honored Lomis, “He mapped out how he would release the 70mm (edition of ‘The Master’).” Lomis also told him that if theaters didn’t want to play it, he “was going to put projectors in them.”

Anderson has not only struck 70mm prints of his post- Master films; he has also gone back to get a 70mm print of his breakthrough 1997 film “ Boogie Nights ,” which played at several repertory theaters this year. Grant Moninger, artistic director of LA-based rep-theater collective American Cinematheque, has programmed many 70mm films. (“ Boogie ” did five packed nights at the Cinematheque’s Aero Theatre last February.) He’s glad Anderson got the ball rolling on reviving 70mm. “It had been pretty much neglected since Kenneth Branagh ’s ‘Hamlet’ or Spike Lee ’s ‘Malcolm X,’” he says. “Some of those were the last gasp of 70. And, so, when Lomis and PTA did that, I think it opened up a world where people started to see it again.”

Repertory theaters around the country have also been getting in on the 70mm love. During the summer, theaters in Chicago , Los Angeles , New York , and Somerville, Mass. have annual 70mm festivals. Netflix also had 70mm festivals when they re-opened movie palaces in New York and Los Angeles . LA venues like the Academy Museum and the Fine Arts Cinema in Beverly Hills continually have 70mm showings. American Cinematheque just had a mini-70mm fest of Nolan’s recent films . (Nolan and producer/wife Emma Thomas were in attendance for Oppenheimer .) There will also be a New Year’s Eve screening of Anderson’s “ Phantom Thread .”

Whether they’re being shown at a multiplex or a repertory theater, 70mm films are still attracting audiences young and old. 70mm offers moviegoers something they can’t get from their flat-screen TV at home: a grand, nostalgic, moviegoing experience. Considering that the upcoming “Dune: Part Two” will be shown in IMAX 70mm , it appears that studios are beginning to realize that 70mm can bring people back to the theaters. “To me, it’s an added attraction,” says Hauerslev. “It all comes down to how do we get the audience into the cinema. You have to show something different from the neighbor cinema… In the ‘80s, when you show a ‘Star Trek’ film in 70mm in Theater A and, next door, you have Theater B, people will flock to Theater A to see it in 70mm. So, people just know that, in 70mm, that’s a better presentation compared to 35mm in the old days, and it’s basically the same today. I mean, you have to have something that gets the audience out of their sofas in their nice living rooms and into the cinemas. And, to me, 70mm has always been able to do that.”

Latest blog posts

The Unloved, Part 124: Play Dirty

Beyoncé and My Daughter Love Country Music

A Poet of an Actor: Louis Gossett, Jr. (1936-2024)

Why I Love Ebertfest: A Movie Lover's Dream

Latest reviews.

The Synanon Fix

Brian tallerico.

The Listener

Matt zoller seitz.

Christy Lemire

On the Adamant

Peter sobczynski.

In the Land of Saints and Sinners

Wicked Little Letters

Sheila o'malley.

Why You Should Go Out Of Your Way To See The Master In 70mm

A major topic of conversation surrounding Paul Thomas Anderson ’s The Master had nothing to do with the enthralling performances of Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman, or even with the film’s obvious connections to Scientology. Film savvy audiences spoke about the need to see The Master in 70mm, Anderson’s preferred method of visual presentation.

But what, exactly, is 70mm presentation? How is this different than, say, IMAX (which several “event” movies like Mission Impossible : Ghost Protocol or the re-released Raiders of the Lost Ark prefer)? And where do you have to actually go to see Anderson’s opus in 70mm?

I was lucky enough to see Anderson’s film at the Toronto International Film Festival, where the movie screened in 70mm at the festival’s TIFF Bell Lightbox. I sat next to my good friend Jay Morong, a lecturer of Theater and Film at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte who also has served as film programmer for the Charlotte Film Society and has been a film projectionist in Massachusetts and North Carolina for 16 years. After our Master screening, I picked Morong’s brain on the beauty of PTA’s vision, and the importance of 70mm projection. You can read what he had to say below, and if you still have questions, feel free to post them in the comments-- I'll do my best to answer them or go back to expert Jay for even more info.

OK, Jay, what, exactly, does 70mm mean?

70mm -- and we are talking 5 perforation 70mm, not IMAX 15 perforation 70mm -- is a large format film stock which produces a motion picture format that is twice the width of a standard 35mm film image. [ Editor's note: Perforations are the holes placed along the sides of each frame, which can be used to measure the height of a frame. The highest number right now is 15, which signifies an IMAX-ready frame. PTA's The Master , even in 70mm, is 5 perforations, and is not being screened in IMAX.] This creates an image area that is at least 3 times the size of standard 35mm. This means that the contrast, colors, and sharpness of the image are impeccable, and when projected on bigger screens there is little-to-no loss of picture quality.

It is (apart from true 70mm/15perf IMAX) the best image that can be presented on a motion picture screen. So that means 70mm is the best possible film medium for a filmmaker to use to get the clearest, cleanest, most vibrant image possible as an artist.

Cool. But is 70mm available in every major market? And if it isn't available at a local theater, why not?

CINEMABLEND NEWSLETTER

Your Daily Blend of Entertainment News

That depends what you mean by “major market.” The short answer is “No.” Most markets that I would consider “major markets” (New York, Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco) all have 70mm, and some of these cities have multiple 70mm houses. (Boston, for example, has the Somerville Theater and the Coolidge Corner Cinema that can both show 70mm.) These cities are, of course, A Tier exhibition markets, so they never lost 70mm and still have it.

For the B and C markets, 70mm has been gone for a while. In fact, I believe the only 70mm in the entire state of North Carolina is housed at the North Carolina School for the Arts. So while 70mm still exists in most states, there are probably no more than 100 theaters (if that) in the country capable of presenting a film in 70mm.

The reason why this happened? Who knows, but my theory has to do with the shift of major theater chains from changeover booths -- where a union/experienced projectionist had to be present to change reels every 20 minutes or so -- to platter systems, where you build up the entire print on a platter and then press start once on a projector and the entire movie plays all the way through. Basically, the theater chains in the 1970s, and onwards, realized that with platter systems you could basically train anyone to run a show. Projection became less of a specialized skill for the chains. This in turn would help them get rid of union projectionists (a skilled labor job) and save them money, since the managers of the theaters could now do projection.

This also started the trend of substandard projection (out of focus, poor framing, dim bulbs, damaged prints) in theaters. It also meant you could build theaters with more screens (multiplexes) since there was less attention needed to run a film. You cannot run a 70mm print on a platter, so as more and more theaters switched to manager-operated projection booths, there was no skilled labor to run 70mm.

Eventually, over time, I think filmmakers and studios saw that this format wasn’t viable since their prints couldn’t be screened in houses, and they slowly abandoned the format. This of course didn’t happen overnight. It took decades. So you still had 70mm in the ‘80s and ‘90s, but it slowly fizzled away as a viable film format for filmmakers.

When you watched The Master in 70mm, did you see a difference? What looked different? And how will it differ from a digital projection, if audiences can’t see it in 70mm as PTA wishes?

Let’s be honest: I sure like to think I did. Although some of it may be subconscious, since I love film formats so much. But that print looked amazing! The print was incredibly sharp, the colors were incredible, and the contrast between the lights and the darks was stunning! I think that is the key to the difference between digital projection and film projection.

Digital, for me, can never get the contrast exactly right. It is always a little muddied or grayed out. So you never get that real depth of field and those real good edges. Things just don’t pop in digital (especially if they were shot originally on film and then transferred to a digital format) like they do with a film print … and especially a 70mm film. If something is shot on film and then converted to digital, digital just cannot get the look of film correct. It can get close, but digital still cannot reproduce a film image exactly. Digital just cannot get the brightness correct in my opinion.

The bottom line for the screening of The Master is this: Watching a film shot in 70mm and then projected in 70mm by an experienced film projectionist means you are not going to get a better image than that, ever, in a cinema (except true 70mm/15perf IMAX). It is the best image there is. That is the highest resolution we have. You cannot get that at home, and digital cinema cannot replicate it. So while 2K or even 4K digital projection is what most people will see the film in -- and it will look great -- you are still miles away from the true celluloid image being presented at some theaters for this film. Click here for an up-to-date list of theaters capable of screening The Master in 70mm.

Sean O’Connell is a journalist and CinemaBlend’s Managing Editor. Having been with the site since 2011, Sean interviewed myriad directors, actors and producers, and created ReelBlend, which he proudly cohosts with Jake Hamilton and Kevin McCarthy. And he's the author of RELEASE THE SNYDER CUT, the Spider-Man history book WITH GREAT POWER, and an upcoming book about Bruce Willis.

32 Great Pieces Of Giles Wisdom From Buffy The Vampire Slayer

32 Quotes From The Twilight Movies That Are Surprisingly Funny

'I See Plenty Of Potential For More': 9-1-1's Oliver Stark Opens Up About ABC Crossover Potential Ahead Of The Bachelor Event

Most Popular

By Jessica Rawden March 31, 2024

By Heidi Venable March 31, 2024

By Carly Levy March 31, 2024

By Laura Hurley March 31, 2024

By Connie Lee March 31, 2024

By Erik Swann March 31, 2024

By Mack Rawden March 31, 2024

By Ryan LaBee March 31, 2024

- 2 32 Hilarious Ricky Gervais Quotes

- 3 The Walking Dead: The One Who Live’s Finale Landed The Emotional Beats, But I Honestly Don't Understand How Anyone Survived

- 4 I Watched Ewan McGregor's A Gentleman In Moscow Premiere, And I Didn't Expect Obi-Wan Kenobi Vibes In The Historical Drama

- 5 Sam Mendes’ Beatles Movies: What We Know So Far

- New Directors/New Films (Begins Wednesday w. Q&As!)

- The Beast (Opens Friday w. Q&A)

- Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus (Ends Thursday!)

- The Taste of Things (Ends Thursday!)

- A Brighter Summer Day + Yi Yi (April 17–25)

- Film Comment Live: Tribute to Navroze Contractor (April 22 w. Q&A)

- The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed (Opens April 26 w. Q&As)

- Hamaguchi I & II (April 26-30)

- 49th Chaplin Award Gala Honoring Jeff Bridges (April 29)

- GIFT : A Film by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi X Live Score by Eiko Ishibashi (May 1 & 2)

- Evil Does Not Exist (Opens May 3 w. Q&A)

- Time of the Heathen (Opens May 10)

- The Met: Live in HD 2023-2024 (Through May 13)

- Become a Member

- Join the New Wave

- Become a Patron

- FLC 25 & Under

- Member Corner

- Gift Certificates

- Partnerships & Advertising

- Film Comment

- Announcements

- Film at Lincoln Center Podcast

- Photo Galleries

- Chaplin Award Gala

- FLC Academies

What is 70mm?

We’re glad you asked! The ancestor of IMAX, 70mm refers to a high-resolution film stock twice the width of ordinary 35mm film. 65mm of the 70mm area is allocated for picture recording and the remaining 5mm for the high-fidelity, six-track magnetic soundtrack (replaced, on newer 70mm prints, by digital sound encoding). While experiments with large-format motion-picture stocks date back to the late 19th century, Hollywood first became interested in the late 1920s, when Fox Film Corporation (the forerunner of 20th Century Fox) introduced a short-lived 70mm film process known as “Grandeur,” used most notably by Raoul Walsh for his 1930 western The Big Trail . (A 35mm version of the film was shot simultaneously.) But the Great Depression and strong resistance from theater owners still in the process of upgrading to sound doomed Grandeur from the start, and it would be another 25 years decades before 70mm returned with a vengeance.

Beginning with Oklahoma! in 1955, a variety of new 70mm processes began to proliferate, including producer Mike Todd’s signature Todd-AO format (which employed a frame rate of 30 frames per second instead of the standard 24) and Ultra Panavision (which used a combination of 70mm stock and anamorphic lenses to create an extra wide 2.76:1 aspect ratio, seen in our series in Khartoum and It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World ). In addition to those screening here, other films originally shot in 70mm include Around the World in 80 Days , Ben-Hur , Cleopatra , Lawrence of Arabia and Patton . The expense of making prints and equipping theaters with proper projection equipment kept 70mm restricted to premiere or “roadshow” engagements in major cities—with 35mm “reduction” prints created for general release—but the format remained in active use for big-budget studio prestige pictures throughout the 1960s, and was used for several decades after that to create “blowup” prints of 35mm movies for special engagements.

Championed by such filmmakers as Paul Thomas Anderson, Brad Bird, Christopher Nolan and Martin Scorsese, the technology lives on in the form of IMAX (which uses 70mm film stock run horizontally through a specially designed camera) and in occasional films shot in traditional 70mm, including this year’s The Master and Samsara .

10 great films shot in 70mm

With directors such as Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino resurrecting the joys of large-format celluloid, we revisit those milestones of 70mm movie-making whose pleasures just cry out for the big screen.

23 December 2015

By Matthew Thrift

It’s probably best, in the words of LL Cool J, that we don’t call it a comeback.

Not just yet, anyway.

With 3D so yesterday’s news, a small band of high-profile members of Hollywood’s digital resistance are resurrecting large-format celluloid – once the preserve of prestige epics from yesteryear – and one man is leading the charge. Not only did Quentin Tarantino shoot his eighth film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film – using reconditioned anamorphic lenses to create a super-widescreen image – he spearheaded a heroic campaign to retrofit over 100 cinemas worldwide with the projectors capable of screening the film in its intended, Ultra Panavision format.

The special ‘Roadshow’ cut of the film, complete with old-school overture and intermission, ran longer than its digital counterpart and needed to be seen to be believed. “The colours scream,” said cinematographer Robert Richardson in a Variety interview on the entirely photochemical process.

Get the latest from the BFI

Sign up for BFI news, features, videos and podcasts.

With so many cinemas exclusively geared towards digital content today, it remains to be seen how many in the UK will be able to play The Hateful Eight from a 70mm print when it opens in January. It’s worth the effort to track down a celluloid screening over its 70-Milli-Vanilli DCP equivalent, the Roadshow cut’s success presumably going some way to determine the format’s fate in the long-run.

It’s not just the added cost and unwieldiness of shooting on such a large format, but as much a question of availability of equipment. Richardson was apparently unable to acquire the same lenses he’d used for Tarantino for his next project, as they’d already been nabbed by Gareth Edwards for the next Star Wars film.

It seems that public appetite has been whetted, however, as sold-out screenings at the Prince Charles Cinema in London – just one theatre where a 70mm projector has recently been installed – can attest. The format may be unlikely to attain the ubiquity of 3D, but then it’s only ever been used for the grandest of productions. So with these 100-odd cinemas now newly fitted with 70mm screening capabilities, we picked out 10 films we’d like to see play in their original format, on the big screen where they belong.

Ben-Hur (1959)

Director: William Wyler

Irrespective of the Gospels’ failure to tease the prospect of expanded cinematic universes beyond the story of the Christ, Hollywood was hardly about to let things lie on Golgotha. What Ben-Hur lacked in parallel-narrative necessity, it certainly made up for in scale, sidelining a certain Nazarene miracle-worker to the role of bit-player in favour of the altogether more toothy charms of Charlton Heston’s greased heroics.

From running time to budget, box office take to Oscar haul, it hardly matters that Ben-Hur remains little more than the sum of its stats. While it’s hard to recall much – even as you’re watching it – beyond the iconic chariot race, this thrilling sequence serves to wholly justify the film’s existence. It’s as breathless today as it is stunningly captured by MGM ’s newfangled Camera 65 system.

Exodus (1960)

Director: Otto Preminger

The most widely recognised of golden age Hollywood directors this side of Alfred Hitchcock (as much a result of his knack for self-promotion as his acting roles in Stalag 17 and the Batman TV series), Otto Preminger remains a tough customer to pin down. As famous for his singular series of film noirs in the 1940s as for his later institutional epics, Preminger would operate on the grandest scale with Exodus, a three-and-a-half-hour adaptation of Leon Uris’s bestseller charting the foundation of the state of Israel.

As well remembered now for its off-screen politics – Preminger hired (and credited) blacklisted screenwriter, Dalton Trumbo – as for those on screen, Exodus remains a directorial tour de force, however dated or one-sided it comes across retrospectively. Rarely screened today – in 70mm, especially – it was a modest hit on release, despite comedian Mort Sahl’s protestations against its length at the premiere, where he stood and shouted mid-film: “Otto, let my people go!”

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Director: David Lean

Of all the cinematic epics captured on 70mm, few come as grand and successfully realised as Lawrence of Arabia. It’s almost impossible to highlight just a single moment from the countless miracles the film pulls off: the visual onomatopoeia of cinema’s greatest ‘match’ cut? The dazzling, single-shot orchestration of the raid on Aqaba? Peter O’Toole dancing in the sunlight aboard the crashed train (shot by Nic Roeg and André de Toth’s second unit)? The dressing of the mirage sequence? Freddie Young’s peerless cinematography?

Of course, the film plays loose with historical veracity, seeking to de-mythologise Lawrence and any sense of Kiplingesque heroics in favour of something that aspires to Shakespearean tragedy. A portrait of a flawed, neurotic genius, its scale and ambition (the 313-day shoot lasting longer than the Arab revolt itself) serves to mock even the most impressive home cinema set-up.

Cleopatra (1963)

Director: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Movies don’t come much bigger than Cleopatra. One of the most expensive and extravagant productions in Hollywood history – it’s $44m budget equates to over $300m today – it remains notorious (incorrectly) as one of cinema’s biggest flops. Originally conceived as a swords-n-sandals quickie, the scale – and problems – swiftly escalated once Elizabeth Taylor was cast in the title role. “Tell them I’ll do it for a million dollars,” said Taylor, cementing her position as the highest paid actress in the business, her behind-the-scenes antics with lover Richard Burton keeping John Glenn’s first orbit of the earth off the front pages of the world’s press.

Audiences came for Liz and Dick; what they got was four hours of riotously camp melodrama and an unimpeachable production design that dwarfed the epic standard set by Ben-Hur. Director Joseph L. Mankiewicz called it: “The most difficult three films I’ve ever made,” going some way to explaining why they don’t make’em like they used to.

The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964)

Director: Anthony Mann

Revisiting the films on this list chronologically, as they’re presented here, provides quite the tonic when one gets to The Fall of the Roman Empire. That it feels so cynical compared to the bombastic emphasis on scale and spectacle employed by Ben-Hur and Cleopatra should come as little surprise, given the proclivities of its director, the great Anthony Mann. Not that the film wants for scale or spectacle either, both of which remain plentiful in Mann’s wintry widescreen vistas. It’s more that it actively suppresses any triumphalism in favour of a masochistic sense that the epoch’s end is predetermined.

To which end, its sensibilities feel strikingly modern, even as it possesses a tactility of design that could never be replicated in our CG -reliant era. Narratively speaking, it shares a kinship with Gladiator (2000), but Mann’s poised frames, encompassing an increasingly desolate strangeness, knock that young upstart’s pretensions for six.

Cheyenne Autumn (1964)

Director: John Ford

If ever there were a filmmaker for whom 70mm were made, it’s John Ford. It’s a shame he didn’t get to work with the format until late in his career (he only made two subsequent features), and that Cheyenne Autumn is hardly a film to rank among his best works. It’s a disjointed telling of a Native American tribe’s journey back to their homeland from enforced exile, something of an apologia for Ford’s less-than-progressive depictions earlier in his career.

While the film feels padded to epic-length – not least through a diversion to Dodge City for an extended James Stewart cameo – there’s no denying the majesty of its location work, stunningly captured in Super Panavision 70 by cinematographer, William Clothier.

Playtime (1967)

Director: Jacques Tati

If ever there were a movie that benefited from the extra definition afforded by shooting on 70mm, it’s Jacques Tati’s 1967 masterpiece, Play Time. With sight-gags playing out, often simultaneously, in every nook and cranny of Tati’s architecturally rigorous frame, it’s impossible to take in everything that Playtime has to offer in a single viewing.

An endlessly inspired, delightfully strange urban satire, it’s a film of absurd curiosity and curious absurdities, shot over two years on a vast, specially constructed city set. The production was plagued with drawbacks, from Tati’s notorious perfectionism to much of the set being destroyed in a storm. A box-office failure on its initial release (bankrupting its director in the process), it’s now considered Tati’s crowning achievement; a film of jaw-dropping ambition that demands the big-screen experience, all the better to drink in its exquisite details played out on the grandest stage.

TRON (1982)

Director: Steven Lisberger

This was shot predominantly on Super Panavision 65, but it’s incredible to think that TRON ’s groundbreaking effects were executed on a computer with just 330mb of storage and a mere 2mb of memory. Jeff Bridges stars as arcade-owning hacker Flynn, digitally interpolated into the computer system he helped create. With its digital gladiatorial contests and technological anthropomorphism, TRON remains a sugar-rush of singular aesthetic vision, standing apart from the effects-driven vehicles that would follow in its wake.

The rotoscopic technique – a combination of traditional cel-animation and multi-layered photographic effects – marks the film as a visually thrilling one-off, its closest descendants perhaps Richard Linklater’s animated experiments, Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006). Even its belated, underrated sequel TRON : Legacy (2010) jettisoned both format and approach for a more conventional – if still remarkable – digitally-rendered IMAX spectacle.

Hamlet (1996)

Director: Kenneth Branagh

Continuing the format’s synonymity with prestige and scale, it’s fitting that the first fully unexpurgated cinematic adaptation of Hamlet would be the last film to be shot on 70mm before the recent semi-revival begun by the last film on our list. Running to over four hours, Branagh’s film cuts as few corners in its production as it does with Shakespeare’s text, the cast list alone an international Who’s Who of old-school and neophyte Bard-botherers.

While Blenheim Palace stands in for Elsinore exteriors, it’s the sumptuous interiors (by production designer Tim Harvey) shot on stages at Shepperton Studios that prove the film’s true star, not least the mirrored throne room around which key scenes revolve. If Branagh’s lead defines an acquired taste, there are few such concerns as far as his direction is concerned, especially when coupled with Alex Thomson’s stellar lensing. It may not reach the dizzying peaks of Kurosawa’s Shakespeare films, but as adaptations go, it’s up there with the best of the rest.

The Master (2012)

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

The special 70mm presentation of Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master back in 2012 proved there’s an appetite for a unique cinema experience away from the now-ubiquitous (and home-replicable) 3D screenings. Using a different set of lenses to those more usually adopted for such a large format, The Master eschews the vast, anamorphic widescreen frame for something tighter, its emphasis on portraiture over the grand landscapes of its antecedents.

Word is out that Anderson is looking to return to 70mm for his next feature (his last, 2014’s Inherent Vice was shot on 35mm), apparently inspired by the 2.78:1 aspect ratio adopted by Tarantino for The Hateful Eight. With Kodak recently announcing a return to profitability in the wake of the latest Star Wars film – perhaps the most high-profile recent feature shot on celluloid – it looks like the format could be back to stay. That said, Anderson could shoot his next feature on a phone, and we’d still be queuing round the block.

Discover award-winning independent British and international cinema

Free for 14 days, then £4.99/month or £49/year.

Other things to explore

10 great bible films.

By Matthew Thrift

5 things to watch this Easter weekend – 29 March to 1 April

By Sam Wigley

5 things to watch this weekend – 22 to 24 March

Explained: What is 70mm film and how is it different from ordinary format? Exploring the hype behind Oppenheimer's ratio

W ith Oppenheimer out and about, there is little doubt about the film's great craftsmanship. The IMAX favorite has won the hearts of viewers and critics alike, making it one of the most successful projects from Christopher Nolan, who has an affinity for good-looking cinema. Over the course of the past few weeks, there have been plenty of mentions about the 70mm film format, which has been used for shooting the Cillian Murphy starrer.

There have been plenty of discussions about the theaters that are more suited to Oppenheimer and the intriguing format that makes the viewing so pleasurable. However, many still fail to understand what makes this format different from the ordinary film format and how it could impact the viewing of Oppenheimer.

In simple words, the 70mm format utilizes frames that are larger in size and wider in aspect ratio than the standard 35mm format. This lets filmmakers capture bigger frames and more richly detailed images within the same rectangle. However, they do need bigger screens for a more holistic experience, much like the 70mm IMAX screens that are ideally suited for Oppenheimer.

"Epic story of a complicated patriot." - TIME.

Get Tickets now to see #Oppenheimer on the largest screen possible. OppenheimerMovie.com pic.twitter.com/nGxv8AgWOS

Another easier analogy to understand the difference between 35mm and 70mm film is the difference between DVD and Blu-Ray. Though not quite similar, it is easier to understand how Blu-ray fits in better resolution and more detail in the same frame.

Exploring the 70mm film format

The 70mm format is hardly a new innovation, unlike many new screen-based technologies. Instead, full-format images have been around since the invention of cinema. However, a 70mm reel meant a larger, heavier, and more cumbersome set of equipment.

Hence, the 35mm was often preferred in the early days. However, 70mm was used for certain sequences or certain movies, like Lawrence of Arabia, to give the moviegoers a sense of added realism and grandeur, something that Christopher Nolan has also aimed for with Oppenheimer.

Apart from the aspect ratio, the pixel density is also different for 70mm films, with the pixels going up to 8000 in certain films. Recently, there has been a resurgence of the format, especially because of the need for more visual appeal. Films like West Side Story have relied on this format before.

Why is it necessary to watch Oppenheimer on a 70mm screen?

The primary reason why there is hype about watching Oppenheimer on the 70mm IMAX screen , which is quite rare in the United States, is because of the director's comments.

Nolan had previously explained that his idea for the film involved watching it in the 70mm format, which could effectively immerse viewers in a 3D-like world. He said:

"The sharpness and the clarity and the depth of the image is unparalleled...The headline, for me, is by shooting on IMAX 70mm film, you're really letting the screen disappear. You're getting a feeling of 3D without the glasses. You've got a huge screen and you're filling the peripheral vision of the audience. You're immersing them in the world of the film."

Moreover, the film is also shot in IMAX format, making it all the more appealing on the bigger screen.

Oppenheimer is now playing in theaters .

How ‘Oppenheimer’ Ignited an Explosion of 70mm

TheWrap magazine: Film-school administrators and a student weigh in whether the celluloid celebration is here to stay or merely a passing fad

A version of this story about the resurgence of celluloid presentation first appeared in the College Issue of TheWrap magazine .

Judging from the lines snaking down the street at 70mm mini festivals taking place everywhere in the past few years — from NYC’s Paris Theater to Chicago’s Music Box Theatre to L.A.’s American Cinematheque theaters — one thing is abundantly clear: The love for celluloid is everlasting. But aside from the proper showcasing of “Oppenheimer,” “Licorice Pizza” and—and if you’re lucky, movies such as “Nope” and “Last Night in Soho” (and on the small screen, the beloved HBO series’ “Succession” and “ Euphoria ,” both film-shot programs), is the ongoing passion for celluloid reflected in current film school curriculum? In the age of digital everything, are future cineastes learning more about the tactile art of tape-handling and editing their work on Steenbecks?

Quite possibly more than you might think. Many institutions still regularly offer courses studying celluloid, particularly 35mm, including New York City’s The New School and Potsdam’s The Konrad Wolf Film University of Babelsberg, and New York University’s graduate film program makes it an essential for first-year students, not to mention a study-away program every year in Prague that specializes in 35mm coursework. “You know, we never stopped it,” says NYU Associate Dean Kanbar Film & Television professor Michael Burke, “we love the rigor in the training of it that’s required for film.” Adds Burke’s colleague, Rosanne Limoncelli, Director of Production for Film and New Media at the Kanbar Institute at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, “It’s not required like it is in the grad program, but the undergrad students also have the opportunity. They take a cinematography class, they can do Super 16mm, they can continue on celluloid if they want to, or they can mix and match.”

Since becoming dean of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts in 2021, Deborah LaVine has observed an uptick in students’ interest in celluloid. “Students love the materialism of it, they love the image that is produced on film, whether it’s black-and-white or color, whether it’s 16mm or 35mm,” she said. “And if it weren’t for the price, I think we would see many, many more student films made on celluloid.”

Ah, yes. The price. Shooting on film can be prohibitive on a student budget, considering the going rate of about $100 per 100 feet of 16mm film stock. Compare that to the cost of laboratory and equipment insurance fees universities can tack on (close to $1000 a semester in some cases), which and it’s easy to understand why cost alone can be an insurmountable hurdle. (The estimated cost of a student film can end up being upwards of $30,000 in many cases.)

Chapman University graduate film student Ben Lu loves celluloid, but he has been learning his craft primarily on digital since he was an undergraduate in Taiwan. This is not inherently a bad thing, since one of his cinematic heroes, a two-time Oscar-winning director of photography who received his 16 th Academy Award nomination last year, has embraced digital.

“Roger Deakins, around 2010, totally transformed from film to digital after shooting with the Arri Alexa (camera),” Lu said. “And (“Knives Out,” “Poker Face”) cinematographer Steve Yedlin , in a presentation, conducted numerous rigorous tests, controlling and operating the variables between digital and film. He showed digital and film side by side, the same exact same shots, and no one could tell the difference.”

But like all beautiful things, film stock is fragile and can wither away if not rigorously protected by archivists, who are integral to the cinematic ecosystem but are not as common as they once were. “Every archivist I know, a major part of their career is constantly re-justifying their existence,” said Matt Jones, associate curator of UNCSA’s impressive film archive, home to more than 30,000 assets including original film prints, trailers, and shorts, some of them original 70mm stock. “A lot of people talk a good game about archiving, but I don’t think it is a sexy cause that can pull down dollars very well. There are a few—your Scorseses and your Tarantinos—that really take it on as personal passion projects. But there’s not nearly enough of them to get it near where it needs to be.”

Still, the UNCSA team is adamant about keeping celluloid preservation alive. The school is so well known for its devotion to film perseveration that when Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” opened in a large number of 70mm and 70mm IMAX formats this past summer, the UNCSA archive department was tapped to train projectionists, since most non-repertory cinemas nowadays only use digital projection. (Jones and his colleagues have also been involved in recent 70mm presentations of Nolan’s “Dunkirk” and Tarantino’s roadshow presentation of “The Hateful Eight.”) “I always tell people when training them here, your first loyalty is to the print.” Further evidence of the school’s commitment: LaVine indicated that UNCSA, like NYU has currently, is looking into beginning a Master’s program for film archiving as soon as next year.

For Lu, Oliver Stone’s 1991 opus “JFK” is a great example of the power of celluloid, with its mix of various film stocks, sometimes within the same scenes, to tell the film’s panoramic tale. He hopes that interest in the artform continues, even if the current 70mm craze fades. “I feel like we have to preserve that history, but not be obstinate about that at the same time,” he said.

And Jones would love to give audiences a greater understanding about what the archival process means. “There’s a pretty baked-in misconception lots of people have where they use ‘archival’ as a synonym for ‘remastered’ and think, ‘Oh, it will be so much better than what we normally see,’” he said. “The truth is, an archival print is going to have all the scratches and the flaws of the lifetime of this print. I mean, you can have fantastic equipment with a very knowledgeable expert projectionist, and it can still go sideways at any time because you’re talking about a moving object that’s pulled through this mechanism. “But I guarantee you,” he added, “in those moments, no one is more interested in getting that show back on track than the projectionist.”

Read more from the College Issue here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Common Film Stocks

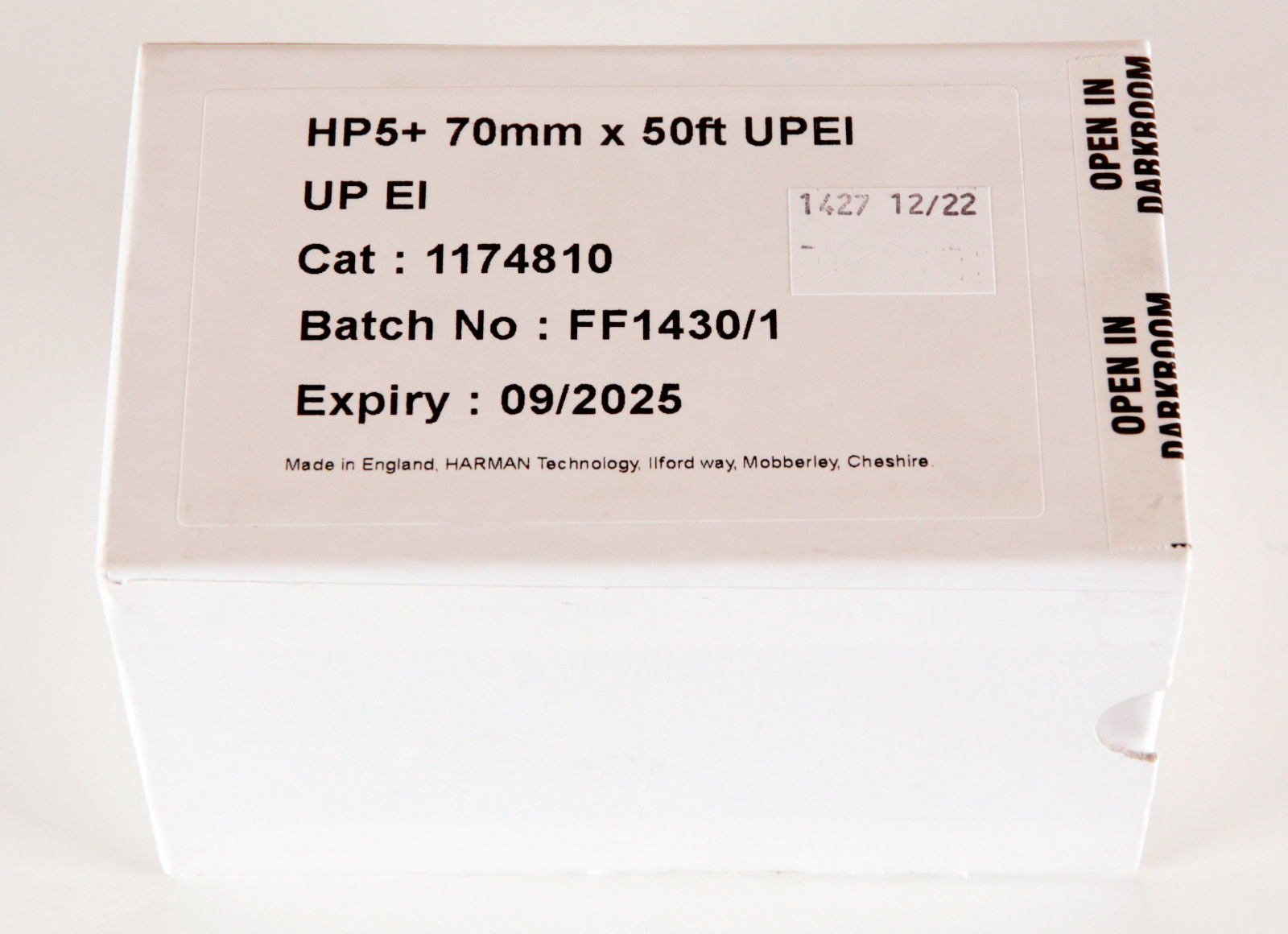

Ilford hp5+.

Unlike traditional 70mm manufacturers, this stock is produced in 50 ft lengths, not 100 ft. It comes as a roll without a spool. Ilford offers it in both perforated and unperforated versions-- unperforated is cheaper.

Ilford's HP5+ costs about the same per exposure in 70mm as 120, but you will gain the other advantages of 70mm discussed above. Because HP5+ can be easily pushed 1-2 stops, this is also the fastest film available in 70mm at this point.

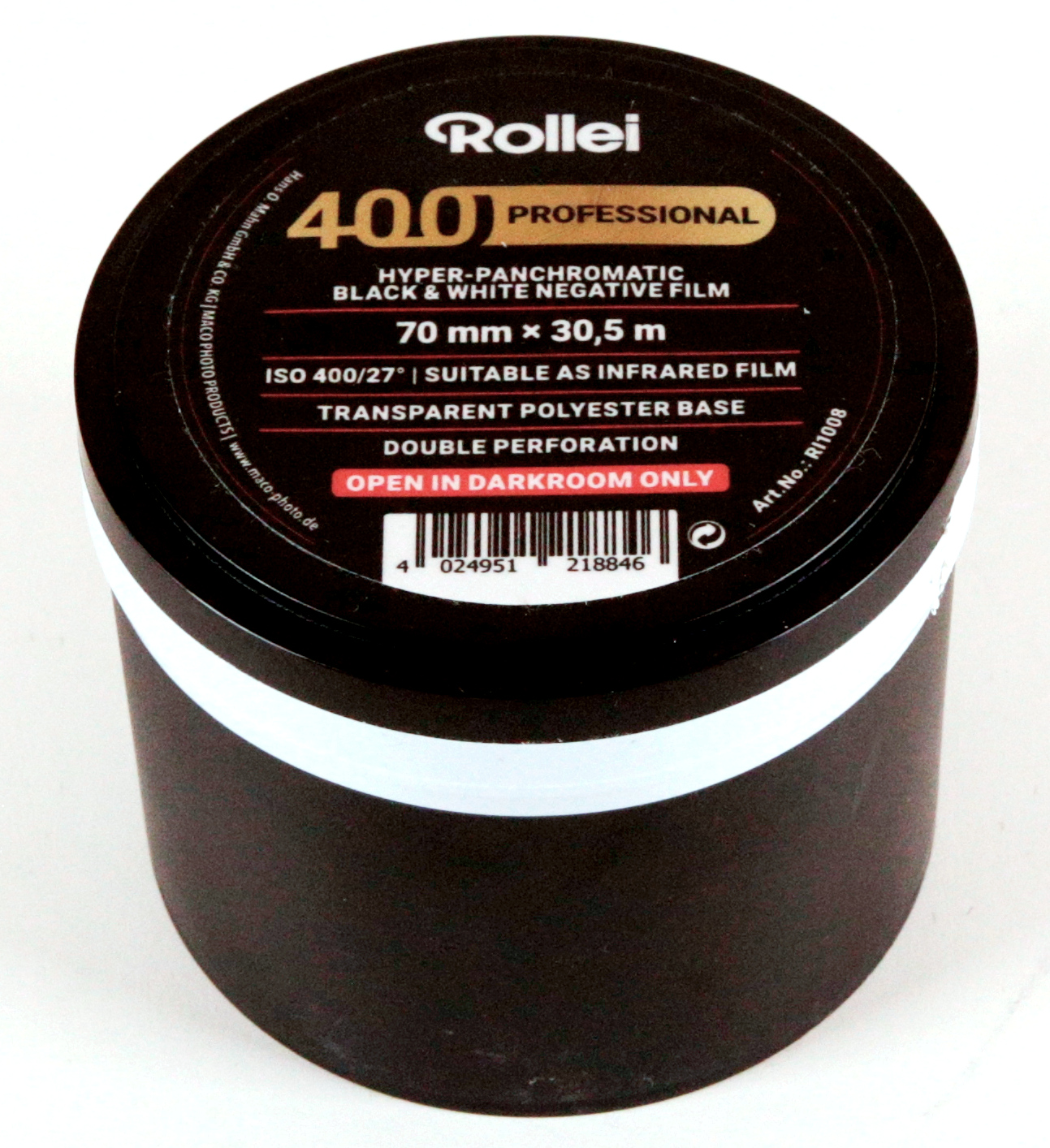

Rollei 400 Professional

This film, which is also marketed in 120 format as “Rollei IR” and “Rollei Retro 400” is produced by Agfa for Rollei. It was produced in 70mm format through 2019, but is now discontinued. There's plenty of it around, with the final batches expiring in 2022. This is a great BW film, with two special advantages: it was much cheaper than HP5+ while it was produced, and it has extended IR range. This means that you can shoot it normally or with an R72 filter for excellent infrared results. When shooting with an R72 filter, open up 5-6 stops from metered exposure.

This film produces beautiful highlights when slightly overexposed. I recommend rating it at 320 ISO, or rating it at its box speed of 400 and pushing it ½ stop in development.

Agfa Aviphot Pan 200

This was Agfa's most popular aerial film and is thus frequently available on the used market for incredibly cheap prices. Agfa still manufactures it, but only on a special order basis. It was (and is) generally available in 30.3M (100ft) lengths, 45.7M (150ft) lengths, and 85M (250ft) lengths, as well as a variety of others, for compatibility with a wide range of aerial cameras. Aviphot Pan is usually perforated, occasionally unperforated.

Agfa reformulated this stock, changing its characteristics slightly, as Rollei 400 Professional. Nonetheless, the original Aviphot Pan is rated at half the speed, and because it is now expired stock, you will need to rate it even slower. We recommend rating this at 100 ISO, or rating it at 200 and pushing it one stop. It's a decent BW stock, suffering only from somewhat high contrast. It has an extreme cost advantage when you buy it in bulk. Stock up on this and you can shoot as much BW film as you wish, for pennies!

One thing to be aware of with this stock, however, is that it has a very thin base. This makes the film slightly more difficult to handle when developing (it isn't as rigid on a spiral, so you have to take greater care when loading it). Once you get used to it, however, it is not a significant problem.

Kodak Plus-X Aerographic

This was Kodak's most popular aerial film for about 60 years. No matter how old it is, unless it exposed to light or stored in blistering heat for years, it holds up quite well. I have a 250 ft roll that expired in 1974 that I purchased for $20 that takes fabulous photos. Here is an example:

Plus-X expired in 1974

This is another stock that is occasionally sold off in large lots by aerographic photo companies on Ebay, and can therefore be extremely economical. It is a fine-grained, beautiful stock, with slightly more latitude and less contrast than Agfa 200. Like that stock, however, it has a thin base, and therefore extra care should be taken when developing it.

Originally this stock was rated at 125 ISO. This is one reason that it ages so well (slower films are more stable over time). I rate stock that expired in 2005 or later at 100. I rate the 1974 stock at 40 ISO. These should give you a good starting point, but as with any expired film, shoot a test at different ISOs and see which one comes out best.

Plus-X expired in 2005

Kodak Portra 160

This was Kodak's most popular professional portrait film from 1998 to 2008 and was produced in 70mm in high quantities. It is sometimes available in larger lots on Ebay when portrait studios clear out their old stock. A lot is in the hands of 70mm enthusiasts at this point.

As a fairly volatile, professional color stock, storage conditions really affect Portra. Its sensitivity has somewhat decreased, but color shift is its bigger problem if it was exposed to heat. Well stored stock will have only minor shift that can be digitally corrected, but poorly stored stock can have significant color shift toward cyan. Often this is not an aesthetically pleasing shift. So some care should be taken to determine the storage conditions of this stock before you purchase it, or you will be rolling the dice. But of course, any film can be used artistically!

Here’s an example of badly heat/age damaged Portra.

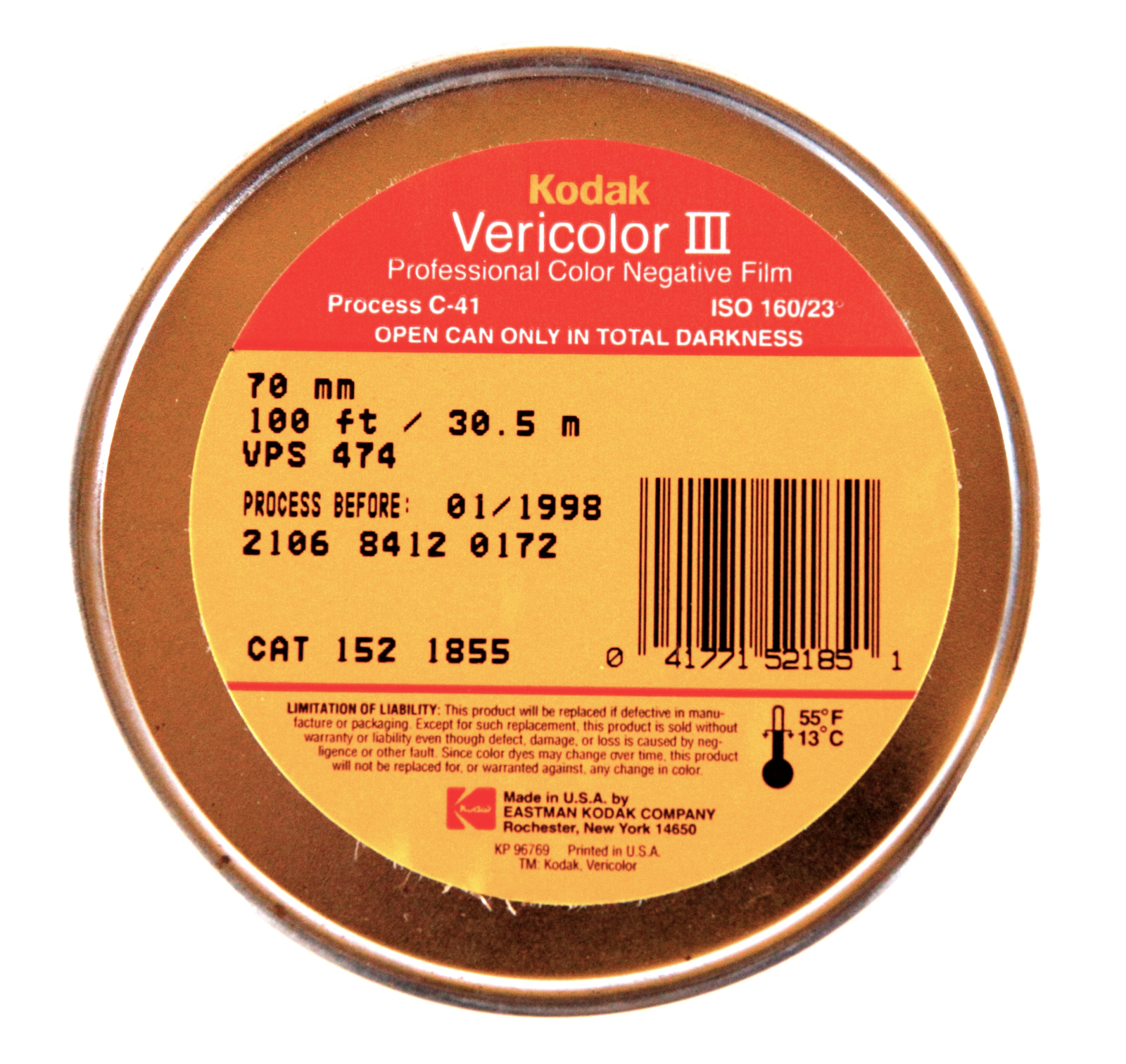

Kodak Vericolor (VPS) III

This was Kodak's professional portrait film from 1987 to 1998, preceding Portra. It was produced in 70mm in very large quantities, and can thus be found sometimes on Ebay

This film also loses sensitivity and shifts color as it ages, especially if subject to higher temperatures. However, unlike Portra, it shifts toward orange. Personally, I love the look of expired Vericolor III! It's my favorite expired color film, in any format.

Be prepared for lower ISOs, though. I rate my 1997 expired film at 50 ISO and it produces rich results.

This stock has a very thick base, and you may not be able to fit a full 15 ft in one cassette. I usually load 56 turns (about 10 ft) instead of 68.

Film Ferrania plans to offer 70mm film in the future, once they have their factory fully working. Mercury Works is also exploring the possibility of packaging and releasing other new stocks, should this community generate sufficient demand. Hopefully we'll be adding to this list in the future!

Less Common 70mm Stocks

Kodak Portra 400: This was less popular than Portra 160, as most 70mm portrait film was used in studios with strobes. In any case, this film is more volatile than Portra 160 and thus suffers to a greater extent from loss of sensitivity and color shift over time. Not recommended unless you are sure that it has been continually cold stored since originally purchased.

Kodak Tri-X: This was a very popular 70mm stock in the 1960s – 1990s. Because it is generally quite old, and is a faster speed film with significant grain, it generally doesn’t age as well as Plus-X.

Kodak Ektachrome 64: The legendary slide film was popular in 70mm. Expired slide film is a risky bet because any color shifts are uncorrectable in your slides. However, slow speed slide film is quite stable and can last much longer, with fewer shifts, than color negative. I have some well-stored rolls of this that produce excellent results. Rate between 32 and 64 ISO depending on age.

Kodak Aerochrome III: Probably Kodak's most legendary stock, this false color chrome (slide) film was only produced in aerial formats--usually 5" and 9.5", but occasionally in 70mm. It turns organic green objects to red, while leaving most other colors intact. However, this is as rare as hens' teeth. In the last decade I've only seen one 70mm roll for sale, and I purchased it (to save some and sell the rest).

Kodak Ektacolor Type S: This was Kodak's first color portrait film in the 70mm format, and was produced from the early 1960s to the mid 1970s. Unfortunately, it uses the older C-22 color development process, for which the original chemicals are no longer available. It can still be developed in BW chemistry, but what's the fun of that? For those willing to experiment, an alternate developing process is given here.

Kodak WL Surveillance: This stock was produced for security cameras. It is a higher speed BW stock that I have not personally used. It is grainy, but has its adherents. Though not as common as the others listed here, and usually older, it is sometimes available on Ebay. Another surveillance film produced in 70mm was Kodak Recording Film 2475 , renowned for its high speed and extreme grain.

Agfa XPS 160: Agfa's professional color portrait film, competitor to Kodak's Vericolor III and Portra. A well regarded portrait film.

Agfa Color N400 / X400: Agfa's color aerial film. As a faster stock, it doesn't age as well. The N version has a regular “orange” base for printing, while the X version has a clear base for projection (and is also very easy to scan nowadays).

Agfa Color N200 / X200: Slower version of Agfa's color aerial film, but even less common.

Fuji CDU-II: This was Fuji's only 70mm stock, and has a special purpose: to duplicate medium format slides through contact printing. It is very slow (rated at 6 ISO if shot as a camera film). It can be cross processed as C41 to produce a negative.

Konica Pro 160: Another 160 ISO portrait stock produced during the heyday of 70mm portraiture.

There are many other film stocks that were released in 70mm. Explore and experiment!

Perforation Types

70mm film comes in three different types of perforation: Type I, Type II, and non-perf.

Type I has a pitch of 5.944mm and fairly large holes. It was an early standard, apparently designed for long-roll portrait cameras. It is common in 1960s and 1970s portrait film.

Type II (4.75mm pitch, smaller holes) is the aerial camera standard and the most common (by volume) perforation to this day. Linhoff, Hasselblad, Mamiya, and Bronica backs are all designed to take this type of perforation because it was common by the time those 70mm systems were developed, and the designers felt that sprockets turned by perforations were the surest method of measuring film transport.

Non-Perf film simply does away with the perforations altogether. 1980s and later portrait film often omits the perforations entirely. Such film is cheaper and easier to manufacture as it leads to less machine wear and fewer quality control rejects. Transet and RH50 large format backs work with this film natively. Other backs need to be modified to “all perf” to do so, as described in the Cameras and Backs page of this site.

Rollei films are labeled “d.p.” which means Type II perfs, or “n.p.” which means non-perf.

Ilford 70mm film is labeled as either “UPEI” (unperforated) or “DPEI” (Type 2 perforations).

Core Variations

100 ft rolls of Kodak 70mm film most commonly come on Kodak’s excellent S-84 metal spool. This is a daylight spool, meaning that it somewhat protects the film from stray light hitting the top or bottom edges of the roll. (Do not, however, ever open a 100 ft can of film in anything but darkness!) The spool has square openings and fits nicely in 70mm cassette loaders.

Kodak S-84 spool with film

However, both Kodak and other companies also produced rolls of 70mm with different cores. Kodak has a “Spec Number” system that specifies the perforation and core configuration of the film. The spec number is printed on all boxes and cans of 70mm film:

Unfortunately, other companies don’t have a similar system, and it can be difficult to tell what core you will receive until you open the film and feel it in darkness. Generally, portrait film often comes on the S-84 spool. Aerial films vary widely.

Agfa aerial films come on very plain cores that are basically just cylinders with large holes in the center. This appears to be similar or identical to Kodak spec 494.

Ilford’s 70mm film comes without any core at all.

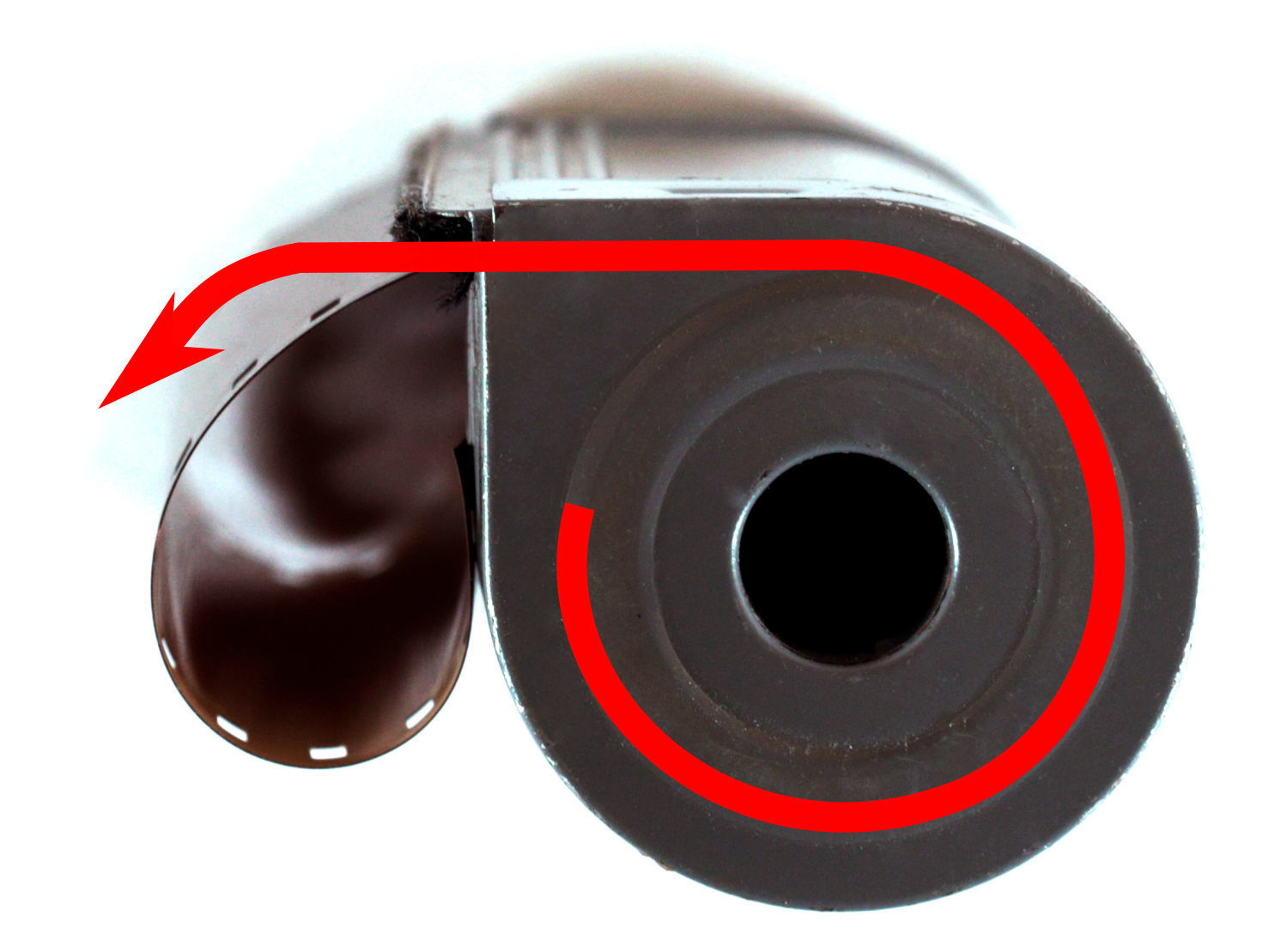

How to Load a 70mm Cassette

You will start with a 100 ft (30.5 m) or 250 ft roll of film. This can only be opened in complete darkness. Film is unspooled from this roll and rolled around a 70mm cassette spool. The film is spooled on emulsion side down. Another way to remember this is that you use the same direction of curl to unroll from the large roll and to spool onto the cassette spool: you should be making use of the curl of the film, not fighting it.

Unspool from a long roll...

...onto a cassette spool

You can do this carefully by hand, or use an Alden 70mm Daylight Loader, or use a Mercury Bulk Loader and spool in darkness.

I have not had good luck with the Daylight Loader. Not only does it have a “counter” that easily catches the film, but I've found that it tends to create hairline scratches in film, especially noticeable in some aerial films. And since you must load and unload it in the dark, there isn't much advantage to doing the actual rolling in the light: it isn't as if there's anything to see!

Nonetheless, some form of loader is useful, to make the process fast, safe for the film (minimizing dust, fingerprints, and scratches) and to accurately count how much film you’ve spooled. You can create a basic loader fairly easily.

Mercury Works recently reformulated its 70mm Cassette Loader kit. The Mercury kit comes with all the parts you need to load various types of 70mm film (which come on different spools, as explained in the 70mm Film section of this guide), as well as a comfortable crank for fast loading. This kit can load film from Kodak SP-84 spools, common cores, aerial cores, and even no core (Ilford). It includes attachments for all of these options.

No matter which method you use, you need to count the number of turns you make while winding the film on the cassette spool:

- 23 turns = 220 length (for developing in 220 reels)

- 46 turns = 10 ft length (thick film)

- 50 turns = 13 ft length (thick film)

- 60 turns = 13 ft length (thin film)

- 68 turns = full 15 ft length (thin film)

I recommend that you load onto a plain cassette spool, then (still in the dark) place the spool inside a cassette when you are done. This prevents extra wear and tear on the light seal of the cassette, and further reduces the potential for hairline scratches. However, if you wish, you can load directly into a cassette.

When placing your wound spool into your cassette, it is important that the emulsion remain on the inside of the curl. See the following image for the correct orientation of the film going out of or into a cassette:

Leave an inch or two of film sticking out of the cassette. If your film disappears into the cassette, you will need to open it in complete darkness to pull out the end.

Don't forget to label your cassette with the film stock inside! You can do this with a small strip of tape on the flat section of the cassette.

Your loaded cassette can be stored inside an original Kodak cassette can, or more compactly and securely with a Mercury cassette canister .

Kodak cassette can

Mercury cassette canister

Advanced: Adding a Leader

If you are shooting with especially rare or expensive film and don't want to lose any of it to the back loading process, you can attach an 11 inch piece of scrap film (preferably already developed). The film and leader must be perfectly aligned to load properly. If loading in a perforated-only back, the perforations should also line up. If shooting with an RH50 or an any-perf modified back, this doesn't matter.

This can be done quickly and easily with the Mercury Cassette Splicer. A guided weight holds your leader in place and your cassette slots in, perfectly aligning the film.

Tape the film on one side with Scotch Magic Tape or Kodak Film Splicing Tape. Allow it to overlap each edge a bit, then fold it over to cover the back side of the film splice. Now turn the spool from the opening on either the top or the bottom of the cassette to roll the leader into the cassette.

The Mercury 70mm Cassette Splicer can be purchased here .

- Action/Adventure

- Children's/Family

- Documentary/Reality

- Amazon Prime Video

More From Decider

'The View's Whoopi Goldberg Blasts Republicans For "Stupid" Question...

R.I.P. Chance Perdomo: ‘Gen V’ & ‘Chilling Adventures Of...

Kyra Sedgwick Tells 'The View' It's Hard To Film Sex Scenes With Husband...

‘10 Things I Hate About You’ Turns 25: Writers Karen McCullah and...

Jenn Tran's 'Bachelorette' Season: Everything We Know About Season 21

'The Bachelor' Season 28 Finale Recap: Did Joey Graziadei Get Engaged To...

'The View' Audience Groans After Kathy Griffin Compares Herself To...

Holly Madison Says There Was Demand For Her to Pose Nude on OnlyFans in...

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to copy URL

Everything You Need To Know About 70mm Film (Plus How It Will Look In Theaters And At Home)

By now, you’ve probably heard the hype surrounding Quentin Tarantino ‘s The Hateful Eight and its rare, 70mm Ultra Panavision format. It sure sounds fancy, but you’re probably wondering: what the heck is 70mm, anyway? And how is it going to look when you watch it in theaters? Or, perhaps more importantly for you couch potatoes, how will the film’s quality fare when it’s available to stream at home? Not to worry: we’ve got all of your formatting and aspect ratio questions answered so you’ll have an idea of what to expect from Tarantino’s latest western epic, no matter where or how you see it following its Christmas Day release. [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gnRbXn4-Yis] What is 70mm and why does it matter? In essence, a 70mm (or 65mm) print of film is a higher resolution format and twice the size of a standard 35mm print. Instead of adhering to the commonly used aspect ratios of 1.375:1 (Academy) or 1.85:1 (standard widescreen; familiarly 16:9), it stretches the image to a much wider ratio of 2.20:1 to 2.28:1 . Though it seems like a confusing, flashy new fad used by some of the industry’s most profitable directors, including Tarantino, Christopher Nolan , and Paul Thomas Anderson ; 70mm has been around since the dawn of motion pictures . Back when audiences would trek out to the “movie palaces” of yesteryear , they sat before a massive, incredibly wide screen that called for an equally wide image. As populations increased and towns across the country acquired multiple movie theaters, however, the size of the screens shrunk, ultimately doing away with the 70mm format and adopting the Academy standard 35mm before the rise of digital. It’s similar to what’s happening nowadays as screens get smaller and smaller. With the advent of digital, new versions of films (that are physically shot on digital, not celluloid film) are able to crunch down the image to whatever size your screen is without compromising resolution, whether you’re watching on your TV, laptop, tablet, or smartphone.

If you watch The Hateful Eight in a theater that isn’t equipped for the format, or, if you view it at home in digital, know that the letterboxes (those black bars on the top and bottom of the screen) will be thicker than they are on the big screen.

Is 'The Chosen' Season 4 Available To Stream?

Does 'Yellowstone' Return Tonight? The Latest Updates On 'Yellowstone's Season 5, Part 2 Premiere Date

Maya Rudolph On The Fake ‘Golden Girls’ Remake Poster: “I Just Want To Say For Amy: Whoever Did This, F*** You”

Why Isn't 'The Bachelor' Finale On Hulu?

'The Accountant 2:' Release Date, Plot, and Everything We Know About the Ben Affleck Sequel

Melissa Barrera Speaks Out On “Mean-Spirited” Reception Of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s ‘In The Heights’: “It Was Very Heartbreaking”

Reverse Shot A different angle on moving images—past, present, and future

What is 70mm.

What Is 70mm? A History of Wide-Gauge Cinema by Nick Pinkerton

It is the format of imperial pomp and imperial folly. It is a tool for showmen that has occasionally found its way into the hands of artists , and sometimes the showman and the artist have been one and the same person. The wide-gauge format 70mm reached its greatest popularity in the 1950s amid a boom of new innovations (Cinemascope, Cinerama, 3D) intended to reverse the fortunes of foundering Hollywood studios; for a time, they even appeared to have done the trick. But every great reign is followed by an epoch of decadence, and the heyday of 70mm encompassed smashes and busts: Oklahoma! (1955) but also Dr. Doolittle (1967); Ben-Hur (1959) but also Cleopatra (1963). One of the greatest films shot in 70mm appeared at the cusp of its popular decline, Anthony Mann’s significantly titled The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). Now Quentin Tarantino, the most high-profile (or at least the most grating) public advocate for preserving analog celluloid as an exhibition format, has shot his The Hateful Eight on the all-but-extinct Ultra Panavision 70, making a crackerjack piece of advance publicity of this fact. The film will open on Christmas in—one expects—nearly every 70mm-equipped theater in the country. As to if this signifies a rise or fall of the format, and in the industry as a whole, remains to be seen.

1. Early Experiments

The appeal of the wide-film image is a combination of consuming clarity and enveloping breadth. Audiences have always been in thrall to the impression made by sheer size, and all the more so when they can lose themselves in a delicate fretwork of detail within that largeness. Herein lay the draw of the original “blockbusters,” paintings on the grand scale teeming with brushstrokes, like the Belshazzar’s Feast (1821) of John Martin, that Cecil B. DeMille of the 19th century; the heroic nationalist mythologies of Jacques-Louis David and John Trumbull; or Frederic Edwin Church’s jungle vista The Heart of the Andes (1859). These are paintings whose subject matters—immersive exotic environments separated from the culture that produced them by vast historical or geographic distance, military fanfare, and the movements of massed men—would often be echoed by those of wide-gauge cinema.

We can’t say how, exactly, the original innovators of wide-gauge celluloid would’ve explained their compulsion toward bigness, but while wide-film formats reached their pinnacle of public visibility from about 1955 to 1965, the history of wide-film goes back very nearly to the birth of cinema. The most touted early innovators of the celluloid motion picture camera on either side of the Atlantic, Auguste and Louis Lumière in France and Thomas Alva Edison and W. K. L. Dickson in the United States, both used a practical, puny 35mm film strip for their early cameras and projectors, though at the time it was by no means the only possible option, and other contemporaries had ideas of their own. Stateside, Edison tried unsuccessfully to exclusively patent his four-perforation 35mm filmstrip. This attempt was struck down by a 1902 court ruling, but until then cautious competitors were forced to experiment with their own formats of varying sizes. Birt Acres, who invented the first 35mm moving picture camera in England and who some consider to have been out ahead of the Lumières, shot a 70mm film of the Henley Regatta in July of 1896. Dickson, after leaving Edison’s employ, experimented with a 68mm filmstrip at the American Mutoscope & Biograph Company, feeding it through the projector by means of unreliable rubber rollers. France’s Demeny-Gaumont produced a 60mm film, while Prestwich in the U.K. made the 63mm negative on which the first wide-gauge hit of early cinema was shot, depicting the entire fourteen-round fight between boxers James J. Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons in Carson City, Nevada, on St. Patrick’s Day in 1897. (Its unusual 1.65:1 widescreen frame, which captured a broader swath of the ring, was dubbed “Veriscope,” an early episode in the long history of hanging silly names onto wide-film processes.) Even the Lumières got into the act, exhibiting a 75mm “widefilm” at Paris’s Universal Exposition of 1900, where the other attractions included Cinéorama, an immersive early virtual reality ride devised by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson which used ten synchronized 70mm projectors to reproduce the experience of hovering over the Jardin des Tuileries in a hot air balloon. (The Cinéorama was shut down after only four days for safety reasons, but its spirit would live on in such novelty formats as Fred Waller’s eleven-projector Vitarama at the 1939 World’s Fair.)

After these early years of idiosyncratic film formats run amok, the Edison-established Motion Picture Patents Company fixed 35mm as the national standard in 1909, and the Congrès International des éditeurs de films in Paris followed suit shortly thereafter. While this thinned the herd of nonconforming wide-film formats, it didn’t end experimentation on wide-gauge film outright. Filoteo Alberini, an Italian exhibitor and cinematographer who had been dabbling in wide-film since the turn of the last century, introduced his 70mm Panoramico Alberini in 1914. John P. Berggren and George Spoor, a cofounder of Chicago-based Essanay Studios, tinkered incessantly with a 63.5mm process called “Natural Vision,” which they used to shoot views from a roller coaster and the Niagara Falls with the intention of inducing potential investors, screening the results in 1926. (A January 1930 article in American Cinematographer on “The Early History of Wide Films” claims that Berggren and Spoor “have worked for more than ten years” on Natural Vision.)

The Natural Vision process would be little employed in feature filmmaking, being used on The American (1927), a now-lost western made under the auspices of “Natural Vision Pictures,” and Danger Lights , a railroad yard drama released by RKO that had its wide-gauge engagement at Chicago’s State Lake Theatre in November 1930. By the time that RKO had begun monkeying around with Natural Vision, they were playing catch-up with the other studios, who’d been testing out their own wide-gauge, widescreen films. Fox Film Corporation introduced their 70mm Grandeur process in 1929, and released a handful of films in it, including Frank Borzage’s Song o’ My Heart and Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail , both in 1930. They would appear at roughly the same time that Warner Brothers, not to be outdone, was unveiling John Francis Dillon’s Kismet (1930), playing in ten cities across America in 65mm, 2.05:1 Vitascope, and that MGM trotted out its 70mm, 2.13:1 Realife, essentially employing the licensed Grandeur camera and lenses, showcased on King Vidor’s Billy the Kid (1930).

In addition to widescreen processes using wide-gauge film, there were several that attempted to create a larger image without abandoning the 35mm format. Perhaps the most famous of these is Polyvision, the simultaneous projection of three synchronized 1.33:1 images that allowed for the triptych scenes in Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927). Along similar lines, in 1921 George W. Bingham and John D. Elms invented a process called Widescope, in which a double-lensed camera recorded images onto two 35mm strips, which combined for an effective 2.66:1 aspect ratio when projected side-by-side. A process called Magnascope was used in exhibiting the maritime battle scenes of Paramount’s 1926 Old Ironsides . At the film’s debut at the since-demolished Rivoli on Broadway and 49th, the image suddenly expanded at a crucial moment in the action, nearly tripling in size from 12 x 18 to 30 x 40 feet as Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld’s orchestra performed “Ship of State.” (Magnascope was also employed in select sequences in other Paramount films, including Chang and Wings .) The effect was produced using a lens on the projector that literally magnified the 35mm frame, enlarging image and grain alike , and resulting in a coarse, low-resolution picture, leading Paramount to further experiments with 56mm Magnifilm, their answer to Grandeur, Vitascope, and Realife. Combined, all of these bits of trial and error and stymied innovation evoke an image not unlike archival footage of failed flying machines, always used to redoubtable comic effect.

These simultaneously occurring developments would appear to presage the wide-gauge, widescreen revolution, but that industry upheaval would have to wait for more than another two decades. This was a matter of economics, pure and simple—there was a Depression at the time, for starters, and moreover exhibitors had just laid out the cash to retrofit their booths and theaters to accommodate new sound-on-film technology, and were in no position to put themselves in hock by paying for another makeover. Until the 1950s, most high-profile developments in film format would involve new narrow-gauge stocks for home usage. Then, at midcentury , faced with new competition and dwindling audiences, the studios struck on supersizing the screen as one way to reestablish moviegoing as an event . As the question of how to get a bigger image without concurrently sacrificing image quality was raised, the old wide-format processes, long malingering in neglect, were waiting to be picked up again.

2. The Big Fifties

The key figure in the return of wide-format cinema was a flamboyant Minneapolis-born theater impresario named Mike Todd, who had entered the motion picture business in 1950, helping to bring a process called Cinerama before the public eye. Fred Waller, earlier of Vitarama fame, had invented Cinerama some years previous, but until the intervention of backers Todd, Lowell Thomas, and Merian C. Cooper, codirector of the Magnascope classic Chang , he had been unable to produce a practical demonstration of it, in part because of the exigencies required for its exhibition—projection of the Cinerama image involved three interlocked projectors running simultaneously, à la Polyvision, their beams combining to create a single image on a special curved screen.

This Is Cinerama , the long-deferred coming-out party for Waller’s process whose scenes included a new variation on the old Natural Vision roller coaster ride, premiered at the Broadway Theatre in New York City on September 30, 1952, but by that time Todd had already left the company, seeking to invest in a widescreen technique that would eliminate the exorbitant demands that Cinerama placed on an exhibitor. The resulting product was Todd-AO, a single-projector widescreen format using a 65mm camera negative and 70mm release print. The “AO” stood for the American Optical Company in Buffalo, New York, where the principal architect of Todd-AO, Dr. Brian O’Brien, the director of the Institute of Optics at the University of Rochester, midwifed it into existence. Todd’s other partners included George Skouras, President of United Artists Theatres, and Joseph Schenck, a veteran studio executive who’d produced Roland West’s 1930 The Bat Whispers , the only film shot in 65mm Magnifilm—no apparent relation to the 56mm Paramount process—with whom Todd formed the Magna Theatre Corporation.

Besides lending the new technology his namesake and oversight, Todd concentrated his efforts on its behalf to his area of expertise: ballyhoo. For the first Todd-AO feature, he set out to sweet-talk composer-librettist team Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, then nothing less than an American institution, into selling him the rights to their 1943 stage hit Oklahoma! , which offered a hummable songbook and, in its “wind comes sweepin’ down the plains” locations, plenty of picturesque opportunities to show off the process. Rodgers and Hammerstein were sufficiently impressed by the Todd-AO demonstration film that they were shown, depicting the canals of Venice, to give Todd and his partners the go-ahead, and Oklahoma! , directed by Fred Zinnemann, premiered on October 11, 1955, at the Hollywood Egyptian in Los Angeles, equipped for the occasion with a mammoth new curved screen intended to emphasize the enveloping embrace of the extreme wide angle photography. Oklahoma! handily earned back its original budget, and the next Todd-AO film, Michael Anderson’s star-strewn Around the World in 80 Days (1956), was a gargantuan hit. A contemporary parody ( Around the Days in 80 Worlds ) in Harvey Kurtzman’s short-lived humor magazine Humbug refers to “Mike Toddy” and his “Toddy A-OO-AH-EE wide screen, bringing movie talkies a step closer to feelies,” while its dialogue razzes the perceived excessive breath of the 2.20:1 Todd-AO frame:

“I’m sorry, Mr. Fogg! We’ve run out of fuel. We can’t find another scrap of wood in the box! We’ll never make it back to England in time!”

“Have you searched both ends of the Toddy-A-AH-E-O wide screen? Surely there is wood somewhere in those vast expanses.”

The successes of Oklahoma! , Around the World in 80 Days , and Todd-AO triggered the second coming, after the late 1920s, of the wide-gauge rush. After Cinerama, the appearance of CinemaScope had expanded the accessibility of widescreen movies—though the latter, by taking over more screen real-estate without a corresponding increase in the size of the film area that was being enlarged through projection, effectively downgraded the resolution of the image being shown, a variation on the old Magnascope conundrum. Fox, who’d been unusually committed to Grandeur, had released the first shot-in-CinemaScope feature, Henry Koster’s The Robe , in fall of 1953. They were also the first on the wide-gauge bandwagon, taking a page from Todd’s playbook and introducing their “Cinemascope 55” with two tried-and-true Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, Carousel and The King and I (both 1956). Cinemascope 55, as the name suggests, used 55mm film, shot on a modified Grandeur camera, though both Carousel and The King and I were exhibited in 35mm and 70mm. Ultimately, equipping theaters for 55mm projection was deemed impracticable, and Fox entered into an exclusive arrangement with Todd-AO beginning with their next Rodgers and Hammerstein adaptation, South Pacific (1958), which also abandoned some of the more idiosyncratic elements of Todd-AO: the thirty frames-per-second frame rate and the curved screen. After Todd’s death in plane crash in spring of 1958, Fox assumed control of the Todd-AO process, and over the next decade the Todd-AO label would grace films including Porgy and Bess (1959), The Alamo (1960), Cleopatra (1963), The Sound of Music (1965), Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965), The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), Krakatoa, East of Java (1969), and Airport (1970), with increasingly less prominence as the brand’s early luster began to fade.

3. Further Expansions

Todd’s death came just as the wide-gauge boom that he’d envisioned was entering its full swing. His soon-to-be-widow, Elizabeth Taylor, would, some time before Cleopatra , star in Raintree County (1957), the first film shot in MGM’s 65mm Camera 65 process, distinguished by its band-thin 2.76:1 aspect ratio. After Ben-Hur (1959), the Camera 65 name was retired, and the format was renamed Ultra Panavision, used on films including Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), The Battle of the Bulge (1965), and Khartoum (1965). ( The Hateful Eight will be the first feature outing for Ultra Panavision in nearly forty years.)

Camera 65/Ultra Panavision was developed with the assistance of Panavision, a Los Angeles company who’d made a fortune by manufacturing anamorphic lenses in the early days of widescreen, and who would later debut a wide-gauge format of their own, the somewhat confusingly named Super Panavision 70. Walt Disney Pictures’ The Big Fisherman (1959), directed by a past-prime Borzage, was the first Super Panavision 70 production, followed in short order by Exodus (1960), West Side Story (1961), My Fair Lady (1964), Cheyenne Autumn (1964), and perhaps the two most famous wide-gauge productions of all time, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Super Panavision would be the preferred format of the few 1980s wide-gauge revivalists, including Tron (1982) and Brainstorm (1983), though its credits for the latter half of the 60s are hit-and-miss, including Lord Jim (1965), Grand Prix (1965), Ice Station Zebra (1968), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), Song of Norway (1970), and Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter (1970).