Citing sources: Overview

- Citation style guides

Manage your references

Use these tools to help you organize and cite your references:

- Citation Management and Writing Tools

If you have questions after consulting this guide about how to cite, please contact your advisor/professor or the writing and communication center .

Why citing is important

It's important to cite sources you used in your research for several reasons:

- To show your reader you've done proper research by listing sources you used to get your information

- To be a responsible scholar by giving credit to other researchers and acknowledging their ideas

- To avoid plagiarism by quoting words and ideas used by other authors

- To allow your reader to track down the sources you used by citing them accurately in your paper by way of footnotes, a bibliography or reference list

About citations

Citing a source means that you show, within the body of your text, that you took words, ideas, figures, images, etc. from another place.

Citations are a short way to uniquely identify a published work (e.g. book, article, chapter, web site). They are found in bibliographies and reference lists and are also collected in article and book databases.

Citations consist of standard elements, and contain all the information necessary to identify and track down publications, including:

- author name(s)

- titles of books, articles, and journals

- date of publication

- page numbers

- volume and issue numbers (for articles)

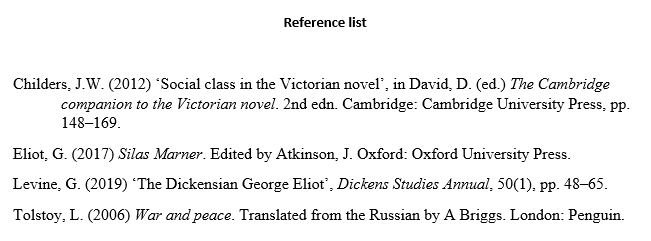

Citations may look different, depending on what is being cited and which style was used to create them. Choose an appropriate style guide for your needs. Here is an example of an article citation using four different citation styles. Notice the common elements as mentioned above:

Author - R. Langer

Article Title - New Methods of Drug Delivery

Source Title - Science

Volume and issue - Vol 249, issue 4976

Publication Date - 1990

Page numbers - 1527-1533

American Chemical Society (ACS) style:

Langer, R. New Methods of Drug Delivery. Science 1990 , 249 , 1527-1533.

IEEE Style:

R. Langer, " New Methods of Drug Delivery," Science , vol. 249 , pp. 1527-1533 , SEP 28, 1990 .

American Psychological Association (APA) style:

Langer, R. (1990) . New methods of drug delivery. Science , 249 (4976), 1527-1533.

Modern Language Association (MLA) style:

Langer, R. " New Methods of Drug Delivery." Science 249.4976 (1990) : 1527-33.

What to cite

You must cite:

- Facts, figures, ideas, or other information that is not common knowledge

Publications that must be cited include: books, book chapters, articles, web pages, theses, etc.

Another person's exact words should be quoted and cited to show proper credit

When in doubt, be safe and cite your source!

Avoiding plagiarism

Plagiarism occurs when you borrow another's words (or ideas) and do not acknowledge that you have done so. In this culture, we consider our words and ideas intellectual property; like a car or any other possession, we believe our words belong to us and cannot be used without our permission.

Plagiarism is a very serious offense. If it is found that you have plagiarized -- deliberately or inadvertently -- you may face serious consequences. In some instances, plagiarism has meant that students have had to leave the institutions where they were studying.

The best way to avoid plagiarism is to cite your sources - both within the body of your paper and in a bibliography of sources you used at the end of your paper.

Some useful links about plagiarism:

- MIT Academic Integrity Overview on citing sources and avoiding plagiarism at MIT.

- Avoiding Plagiarism From the MIT Writing and Communication Center.

- Plagiarism: What It is and How to Recognize and Avoid It From Indiana University's Writing Tutorial Services.

- Plagiarism- Overview A resource from Purdue University.

- Next: Citation style guides >>

- Last Updated: Jan 16, 2024 7:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/citing

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and Examples

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Citation

Research paper citation refers to the act of acknowledging and referencing a previously published work in a scholarly or academic paper . When citing sources, researchers provide information that allows readers to locate the original source, validate the claims or arguments made in the paper, and give credit to the original author(s) for their work.

The citation may include the author’s name, title of the publication, year of publication, publisher, and other relevant details that allow readers to trace the source of the information. Proper citation is a crucial component of academic writing, as it helps to ensure accuracy, credibility, and transparency in research.

How to Cite Research Paper

There are several formats that are used to cite a research paper. Follow the guide for the Citation of a Research Paper:

Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Smith, John. The History of the World. Penguin Press, 2010.

Journal Article

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, vol. Volume Number, no. Issue Number, Year of Publication, pp. Page Numbers.

Example : Johnson, Emma. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Environmental Science Journal, vol. 10, no. 2, 2019, pp. 45-59.

Research Paper

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Paper.” Conference Name, Location, Date of Conference.

Example : Garcia, Maria. “The Importance of Early Childhood Education.” International Conference on Education, Paris, 5-7 June 2018.

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Title, Publisher, Date of Publication, URL.

Example : Smith, John. “The Benefits of Exercise.” Healthline, Healthline Media, 1 March 2022, https://www.healthline.com/health/benefits-of-exercise.

News Article

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper, Date of Publication, URL.

Example : Robinson, Sarah. “Biden Announces New Climate Change Policies.” The New York Times, 22 Jan. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/climate/biden-climate-change-policies.html.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example: Smith, J. (2010). The History of the World. Penguin Press.

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range.

Example: Johnson, E., Smith, K., & Lee, M. (2019). The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture. Environmental Science Journal, 10(2), 45-59.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of paper. In Editor First Initial. Last Name (Ed.), Title of Conference Proceedings (page numbers). Publisher.

Example: Garcia, M. (2018). The Importance of Early Childhood Education. In J. Smith (Ed.), Proceedings from the International Conference on Education (pp. 60-75). Springer.

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of webpage. Website name. URL

Example: Smith, J. (2022, March 1). The Benefits of Exercise. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/benefits-of-exercise

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Newspaper name. URL.

Example: Robinson, S. (2021, January 22). Biden Announces New Climate Change Policies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/climate/biden-climate-change-policies.html

Chicago/Turabian style

Please note that there are two main variations of the Chicago style: the author-date system and the notes and bibliography system. I will provide examples for both systems below.

Author-Date system:

- In-text citation: (Author Last Name Year, Page Number)

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

- In-text citation: (Smith 2005, 28)

- Reference list: Smith, John. 2005. The History of America. New York: Penguin Press.

Notes and Bibliography system:

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, Title of Book (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), Page Number.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: John Smith, The History of America (New York: Penguin Press, 2005), 28.

- Bibliography citation: Smith, John. The History of America. New York: Penguin Press, 2005.

JOURNAL ARTICLES:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Article Title.” Journal Title Volume Number (Issue Number): Page Range.

- In-text citation: (Johnson 2010, 45)

- Reference list: Johnson, Mary. 2010. “The Impact of Social Media on Society.” Journal of Communication 60(2): 39-56.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Article Title,” Journal Title Volume Number, Issue Number (Year): Page Range.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Article Title.” Journal Title Volume Number, Issue Number (Year): Page Range.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Mary Johnson, “The Impact of Social Media on Society,” Journal of Communication 60, no. 2 (2010): 39-56.

- Bibliography citation: Johnson, Mary. “The Impact of Social Media on Society.” Journal of Communication 60, no. 2 (2010): 39-56.

RESEARCH PAPERS:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Paper.” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date. Publisher, Page Range.

- In-text citation: (Jones 2015, 12)

- Reference list: Jones, David. 2015. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015. Springer, 10-20.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Paper,” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), Page Range.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Paper.” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date. Place of publication: Publisher, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: David Jones, “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015 (New York: Springer, 10-20).

- Bibliography citation: Jones, David. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015. New York: Springer, 10-20.

- In-text citation: (Author Last Name Year)

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL.

- In-text citation: (Smith 2018)

- Reference list: Smith, John. 2018. “The Importance of Recycling.” Environmental News Network. https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Webpage,” Website Name, URL (accessed Date).

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL (accessed Date).

- Footnote/Endnote citation: John Smith, “The Importance of Recycling,” Environmental News Network, https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling (accessed April 8, 2023).

- Bibliography citation: Smith, John. “The Importance of Recycling.” Environmental News Network. https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling (accessed April 8, 2023).

NEWS ARTICLES:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper, Month Day.

- In-text citation: (Johnson 2022)

- Reference list: Johnson, Mary. 2022. “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity.” The New York Times, January 15.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Article,” Name of Newspaper (City), Month Day, Year.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper (City), Month Day, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Mary Johnson, “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity,” The New York Times (New York), January 15, 2022.

- Bibliography citation: Johnson, Mary. “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity.” The New York Times (New York), January 15, 2022.

Harvard referencing style

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example: Smith, J. (2008). The Art of War. Random House.

Journal article:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of journal, volume number(issue number), page range.

Example: Brown, M. (2012). The impact of social media on business communication. Harvard Business Review, 90(12), 85-92.

Research paper:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of paper. In Editor’s First initial. Last name (Ed.), Title of book (page range). Publisher.

Example: Johnson, R. (2015). The effects of climate change on agriculture. In S. Lee (Ed.), Climate Change and Sustainable Development (pp. 45-62). Springer.

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of page. Website name. URL.

Example: Smith, J. (2017, May 23). The history of the internet. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-the-internet

News article:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of newspaper, page number (if applicable).

Example: Thompson, E. (2022, January 5). New study finds coffee may lower risk of dementia. The New York Times, A1.

IEEE Format

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Book. Publisher.

Smith, J. K. (2015). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House.

Journal Article:

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Title of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number), page numbers.

Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. K. (2016). Interactivity and the Future of Journalism. Journalism Studies, 17(2), 228-246.

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Paper. Paper presented at Conference Name, Location.

Jones, L. K., & Brown, M. A. (2018). The Role of Social Media in Political Campaigns. Paper presented at the 2018 International Conference on Social Media and Society, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Website: Author(s) or Organization Name. (Year of Publication or Last Update). Title of Webpage. Website Name. URL.

Example: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (2019, August 29). NASA’s Mission to Mars. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/topics/journeytomars/index.html

- News Article: Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Name of News Source. URL.

Example: Johnson, M. (2022, February 16). Climate Change: Is it Too Late to Save the Planet? CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/16/world/climate-change-planet-scn/index.html

Vancouver Style

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “The study conducted by Smith and Johnson^1 found that…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of book. Edition if any. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Smith J, Johnson L. Introduction to Molecular Biology. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “Several studies have reported that^1,2,3…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of article. Abbreviated name of journal. Year of publication; Volume number (Issue number): Page range.

Example: Jones S, Patel K, Smith J. The effects of exercise on cardiovascular health. J Cardiol. 2018; 25(2): 78-84.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “Previous research has shown that^1,2,3…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of paper. In: Editor(s). Title of the conference proceedings. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication. Page range.

Example: Johnson L, Smith J. The role of stem cells in tissue regeneration. In: Patel S, ed. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Regenerative Medicine. London: Academic Press; 2016. p. 68-73.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “According to the World Health Organization^1…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of webpage. Name of website. URL [Accessed Date].

Example: World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public [Accessed 3 March 2023].

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “According to the New York Times^1…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of article. Name of newspaper. Year Month Day; Section (if any): Page number.

Example: Jones S. Study shows that sleep is essential for good health. The New York Times. 2022 Jan 12; Health: A8.

Author(s). Title of Book. Edition Number (if it is not the first edition). Publisher: Place of publication, Year of publication.

Example: Smith, J. Chemistry of Natural Products. 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2015.

Journal articles:

Author(s). Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume, Inclusive Pagination.

Example: Garcia, A. M.; Jones, B. A.; Smith, J. R. Selective Synthesis of Alkenes from Alkynes via Catalytic Hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10754-10759.

Research papers:

Author(s). Title of Paper. Journal Name Year, Volume, Inclusive Pagination.

Example: Brown, H. D.; Jackson, C. D.; Patel, S. D. A New Approach to Photovoltaic Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2018, 26, 134-142.

Author(s) (if available). Title of Webpage. Name of Website. URL (accessed Month Day, Year).

Example: National Institutes of Health. Heart Disease and Stroke. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/heart-disease-and-stroke (accessed April 7, 2023).

News articles:

Author(s). Title of Article. Name of News Publication. Date of Publication. URL (accessed Month Day, Year).

Example: Friedman, T. L. The World is Flat. New York Times. April 7, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/07/opinion/world-flat-globalization.html (accessed April 7, 2023).

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a book should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of book (in italics)

- Edition (if applicable)

- Place of publication

- Year of publication

Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, et al. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th ed. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman; 2000.

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a journal article should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of article

- Abbreviated title of journal (in italics)

- Year of publication; volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Chen H, Huang Y, Li Y, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e207081. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7081

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a research paper should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of paper

- Name of journal or conference proceeding (in italics)

- Volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Bredenoord AL, Kroes HY, Cuppen E, Parker M, van Delden JJ. Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet. 2011;27(2):41-47. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2010.11.004

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a website should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of web page or article

- Name of website (in italics)

- Date of publication or last update (if available)

- URL (website address)

- Date of access (month day, year)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to protect yourself and others. CDC. Published February 11, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a news article should include the following information, in this order:

- Name of newspaper or news website (in italics)

- Date of publication

Gorman J. Scientists use stem cells from frogs to build first living robots. The New York Times. January 13, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/13/science/living-robots-xenobots.html

Bluebook Format

One author: Daniel J. Solove, The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet (Yale University Press 2007).

Two or more authors: Martha Nussbaum and Saul Levmore, eds., The Offensive Internet: Speech, Privacy, and Reputation (Harvard University Press 2010).

Journal article

One author: Daniel J. Solove, “A Taxonomy of Privacy,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 154, no. 3 (January 2006): 477-560.

Two or more authors: Ethan Katsh and Andrea Schneider, “The Emergence of Online Dispute Resolution,” Journal of Dispute Resolution 2003, no. 1 (2003): 7-19.

One author: Daniel J. Solove, “A Taxonomy of Privacy,” GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 113, 2005.

Two or more authors: Ethan Katsh and Andrea Schneider, “The Emergence of Online Dispute Resolution,” Cyberlaw Research Paper Series Paper No. 00-5, 2000.

WebsiteElectronic Frontier Foundation, “Surveillance Self-Defense,” accessed April 8, 2023, https://ssd.eff.org/.

News article

One author: Mark Sherman, “Court Deals Major Blow to Net Neutrality Rules,” ABC News, January 14, 2014, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/wireStory/court-deals-major-blow-net-neutrality-rules-21586820.

Two or more authors: Siobhan Hughes and Brent Kendall, “AT&T Wins Approval to Buy Time Warner,” Wall Street Journal, June 12, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/at-t-wins-approval-to-buy-time-warner-1528847249.

In-Text Citation: (Author’s last name Year of Publication: Page Number)

Example: (Smith 2010: 35)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Book. Edition. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Smith J. Biology: A Textbook. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Example: (Johnson 2014: 27)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Article. Abbreviated Title of Journal. Year of publication;Volume(Issue):Page Numbers.

Example: Johnson S. The role of dopamine in addiction. J Neurosci. 2014;34(8): 2262-2272.

Example: (Brown 2018: 10)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Paper. Paper presented at: Name of Conference; Date of Conference; Place of Conference.

Example: Brown R. The impact of social media on mental health. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; August 2018; San Francisco, CA.

Example: (World Health Organization 2020: para. 2)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Webpage. Name of Website. URL. Published date. Accessed date.

Example: World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. WHO website. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-coronavirus-2019. Updated August 17, 2020. Accessed September 5, 2021.

Example: (Smith 2019: para. 5)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Article. Title of Newspaper or Magazine. Year of publication; Month Day:Page Numbers.

Example: Smith K. New study finds link between exercise and mental health. The New York Times. 2019;May 20: A6.

Purpose of Research Paper Citation

The purpose of citing sources in a research paper is to give credit to the original authors and acknowledge their contribution to your work. By citing sources, you are also demonstrating the validity and reliability of your research by showing that you have consulted credible and authoritative sources. Citations help readers to locate the original sources that you have referenced and to verify the accuracy and credibility of your research. Additionally, citing sources is important for avoiding plagiarism, which is the act of presenting someone else’s work as your own. Proper citation also shows that you have conducted a thorough literature review and have used the existing research to inform your own work. Overall, citing sources is an essential aspect of academic writing and is necessary for building credibility, demonstrating research skills, and avoiding plagiarism.

Advantages of Research Paper Citation

There are several advantages of research paper citation, including:

- Giving credit: By citing the works of other researchers in your field, you are acknowledging their contribution and giving credit where it is due.

- Strengthening your argument: Citing relevant and reliable sources in your research paper can strengthen your argument and increase its credibility. It shows that you have done your due diligence and considered various perspectives before drawing your conclusions.

- Demonstrating familiarity with the literature : By citing various sources, you are demonstrating your familiarity with the existing literature in your field. This is important as it shows that you are well-informed about the topic and have done a thorough review of the available research.

- Providing a roadmap for further research: By citing relevant sources, you are providing a roadmap for further research on the topic. This can be helpful for future researchers who are interested in exploring the same or related issues.

- Building your own reputation: By citing the works of established researchers in your field, you can build your own reputation as a knowledgeable and informed scholar. This can be particularly helpful if you are early in your career and looking to establish yourself as an expert in your field.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

How To Cite a Research Paper: MLA, APA, and Chicago Style

- Posted on January 25, 2022

When you’re writing a research paper, you’ll use a variety of sources to find information. You might find that you end up using other people’s research papers as sources of information for your own work. You need to know how to cite a research paper properly.

Using text citations tells readers where you got your information, and help build a sense of trust, allowing the reader to feel confident that you haven’t falsified the information. You have to prove that you’ve done the research and found data to back up the claims you’re making.

Writing a paper without giving credit to people whose work you’re using is plagiarism. Unless you’re citing a direct quote you want to change the language enough, by putting the quote in your own words, so it sounds like original content. Quetext’s plagiarism checker helps you search for similar content across the web so you can turn in a completely original paper.

Whether you’re submitting a research paper to school or for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, you’re required to cite your sources. Editors often reread the work of writers and researchers to ensure the information is factual. A teacher or professor will definitely check that your sources are accurate, so using tools like Quetext will help avoid unintentional plagiarism errors or wrongfully cited information.

Why Text Citations are Important

If you don’t have sources to back up your research, others might accuse you of spreading false information or plagiarism. Any journal publishing papers should verify what they’re printing, but ultimately, as the author, the buck stops with you.

In general, it’s a kindness to cite your sources. The people who created them did a lot of work, so it’s wrong to claim ownership of their ideas and information. But it’s also an ethical issue that can have major repercussions.

There have been cases where researchers make up information or falsify their sources and must face the consequences. People depend on factual information and don’t react well when they realize you lied to them or falsely paraphrase information.

That’s why it’s common knowledge to write a well-researched paper with text citations. If anyone claims your information is incorrect, you can point them to the source where you found the data. This doesn’t guarantee that the information you cited is correct, but you’ll be able to provide readers with a source of where you gathered your information.

When you’re citing other people’s research papers, make sure the source is legitimate. You should only use peer-reviewed journals so you know the article has gone through edits and fact-checking. Something identified as a research paper that is only on a blog or message board isn’t always a reliable source.

Many students like to use Wikipedia because there’s so much information available from one source. However, Wikipedia allows users to edit the information. What you read in a specific entry might not be true. It’s best to scroll down to the works cited and go to the original source yourself. If you can’t find a reliable, original source for the information, you shouldn’t use it.

Using the Various Citation Styles

The information used in any citation is basically the same across each style guide. The formatting and order of some elements may vary, so it’s important to know the difference between Modern Language Association (MLA), American Psychological Association (APA), and Chicago Styles.

The style you use depends on what type of writing you’re doing. All will use these basic elements in some form or another:

Source name

Volume and edition

Publication date

Page numbers

Publisher name

City and country of the publisher

URL and DOI for web pages and digital sources

The date you accessed the material

In addition to a reference list at the end of your work, you’ll also use in-text citations. Whenever you reference an idea or data that isn’t yours, you cite it. Each style has different types of in-text citations as well. Read on to find out about each citation format.

You’ll likely use the MLA citation guide if you’re writing papers in the humanities, such as for language arts, literary criticism, cultural studies, and more. The current edition of the MLA Handbook is the ninth because the style constantly evolves. As new technology creates new potential sources, MLA adds information to help students and researchers cite everything correctly.

The MLA Handbook has instructions on how to cite song lyrics, social media posts, and digital images, along with all of the standard research outlets. The book also gives detailed information on how to cite a research paper.

The MLA Handbook includes information about how to format your reference page. Use a 12-pt standard font like Times New Roman, so the text in italics is clearly different from the regular font. Center the title, Works Cited, at the top of the page. Your last name and page number are in the top right corner, and the reference page always comes at the end of your document.

Alphabetize citations according to the last name of the author. Left-align the citations and double-space them with no extra lines between each entry. When a citation goes beyond a single line, use a hanging indent to format it correctly. This lets the reader know it’s still the same citation continuing on.

Now that you know the basic format for the Works Cited page read on to find out how to cite a research paper for inclusion on this list.

Citing a Research Paper in MLA Style

When you’re citing a research paper in MLA style, you start with the author’s full name, putting the last name of the author first, followed by the title of the research paper in quotation marks. Next comes the the title of the journal that published the paper in italics, followed by the volume number, issue number, and date of publication.

You’ll also include the page number since the paper is in a journal with many pages. If you found the source online, include the digital object identifier or DOI. The DOI is a way to give a document a permanent web address so people reading your work can easily find the source.

MLA format also asks you to include the date you accessed online materials. Doing so gives your reader more information about when you read the research if it changed since that date. Here is an example of a research paper citation in MLA style:

Writer, Maria. “My Research Paper.” Research Journal, vol 3, no. 4, 2020, pp. 7-9. doi:12.34/mfs.12.34. Accessed 13 March 2021.

If the work wasn’t published online, you could stop your citation after the page numbers.

Sometimes you might find research papers that aren’t published in a scholarly journal. You can still use those in your work, but the MLA citation will look different. You’ll still put the last name of the author first, but instead of putting the title of the research paper in quotation marks, you’ll put it in italics.

Here is an example of an unpublished research paper citation in MLA style:

Writer, Maria. My Research Paper. 2020, http://websiteused.com . Accessed 13 March 2021.

These two examples show you how to document the source on your Works Cited page. In-text citations look different.

In-Text Citations for a Research Paper in MLA Style

When you’re working with the MLA format, an in-text reference requires a parenthetical citation.

If you refer to someone else’s research in a sentence, either with a direct quote or by paraphrasing, you need to give that author credit. At the end of the sentence where you use the information, you’ll put the author’s information in parenthesis and then put the sentence’s ending punctuation.

You use the author’s last name and the page number where you found the information for in-text citations. Then anyone reading your work can go to your Works Cited page, find the entry by the author’s last name, and access the document themselves. The page number directs them to where you got the specific information, so they don’t have to read the whole paper to find it. Here is an example of an in-text citation in MLA style:

Over 80% of the city’s garbage ended up in the ocean (Writer, 8).

You might mention the author’s name in your sentence. In that case, the parenthetical citation only needs to have the page numbers for reference. Here is an example:

According to Maria Writer, over 80% of the city’s garbage went into the ocean (8).

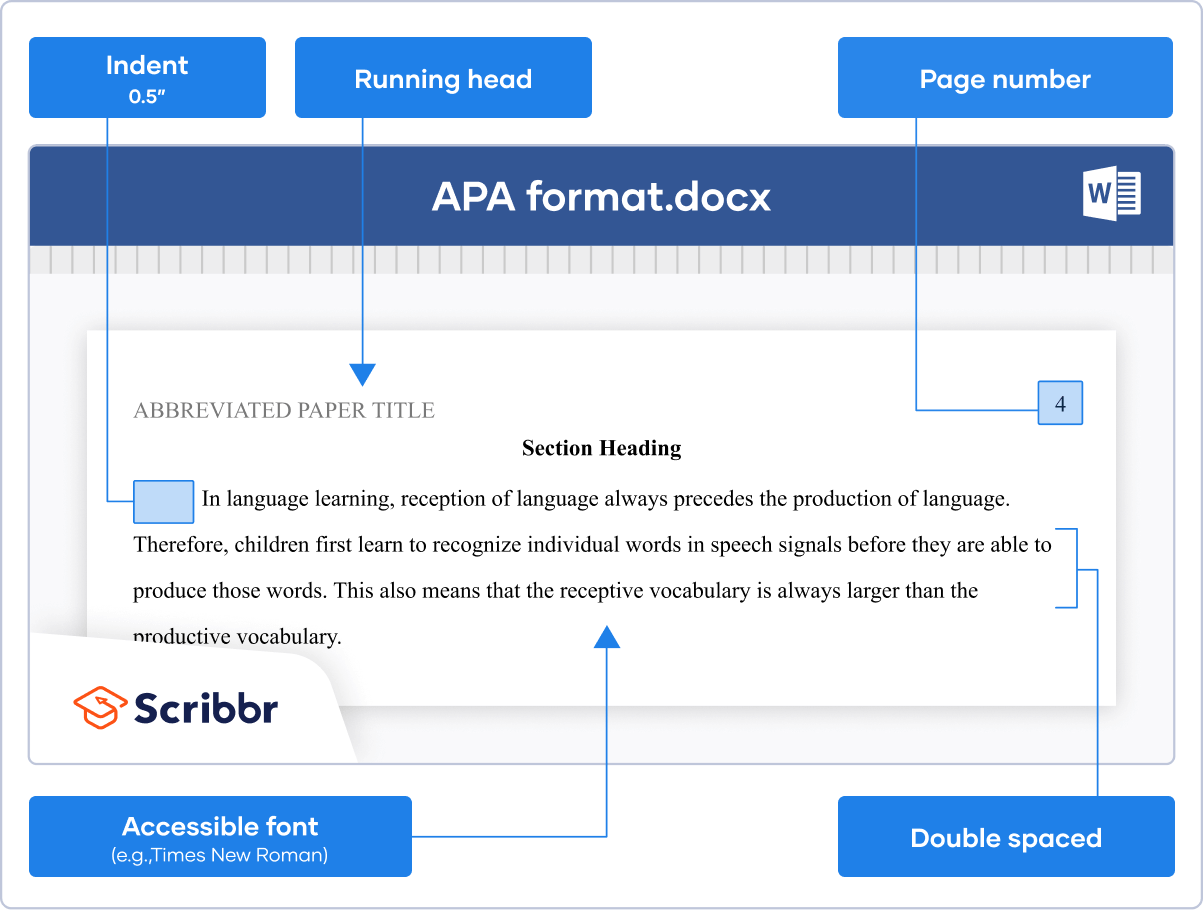

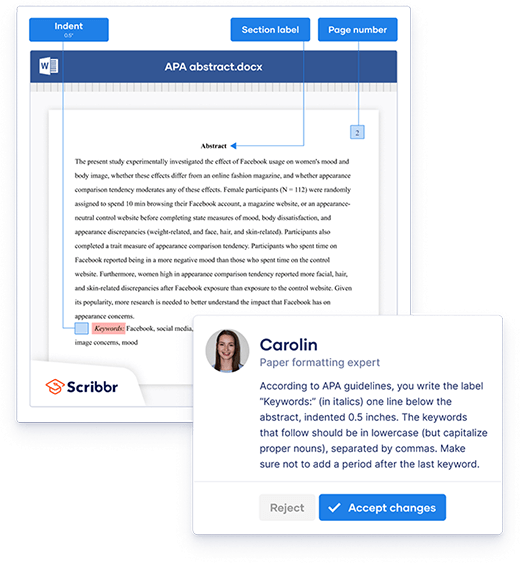

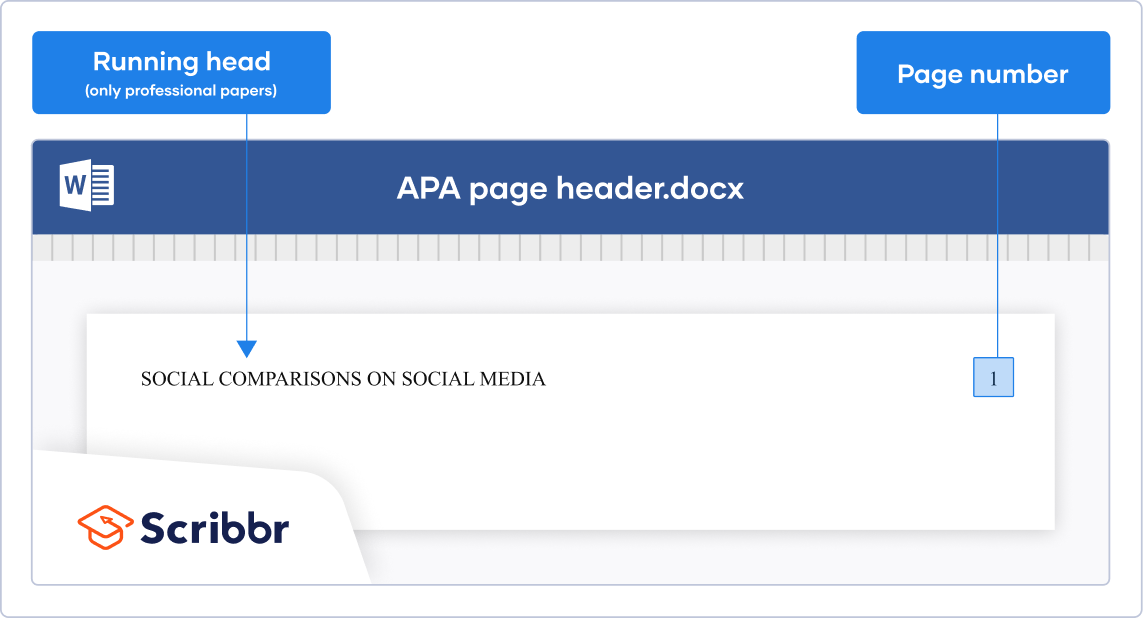

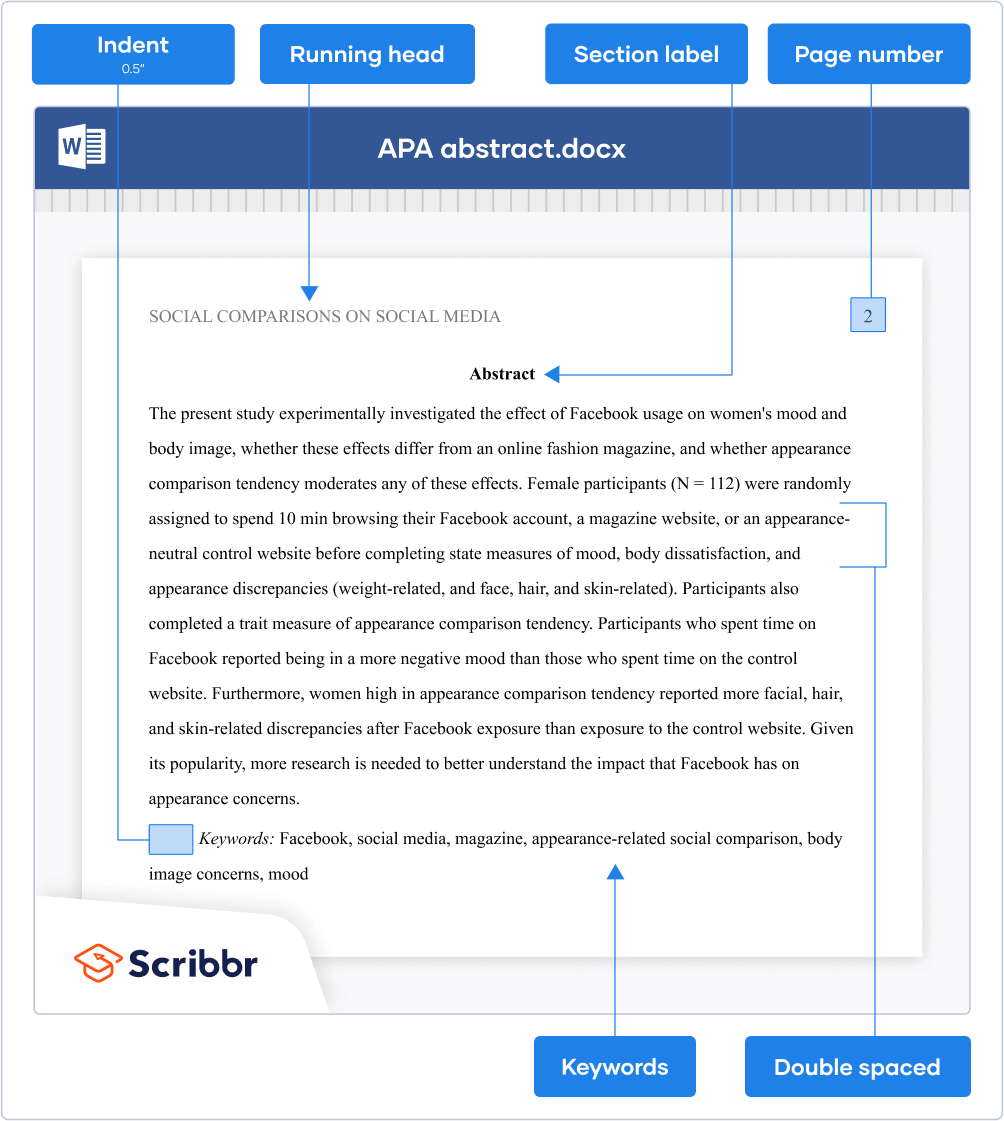

Researchers in the social science field, like sociology, anthropology, and psychology, use the APA style in their work. Like the MLA Handbook, the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association has gone through changes over the years. It’s currently on the 7th edition.

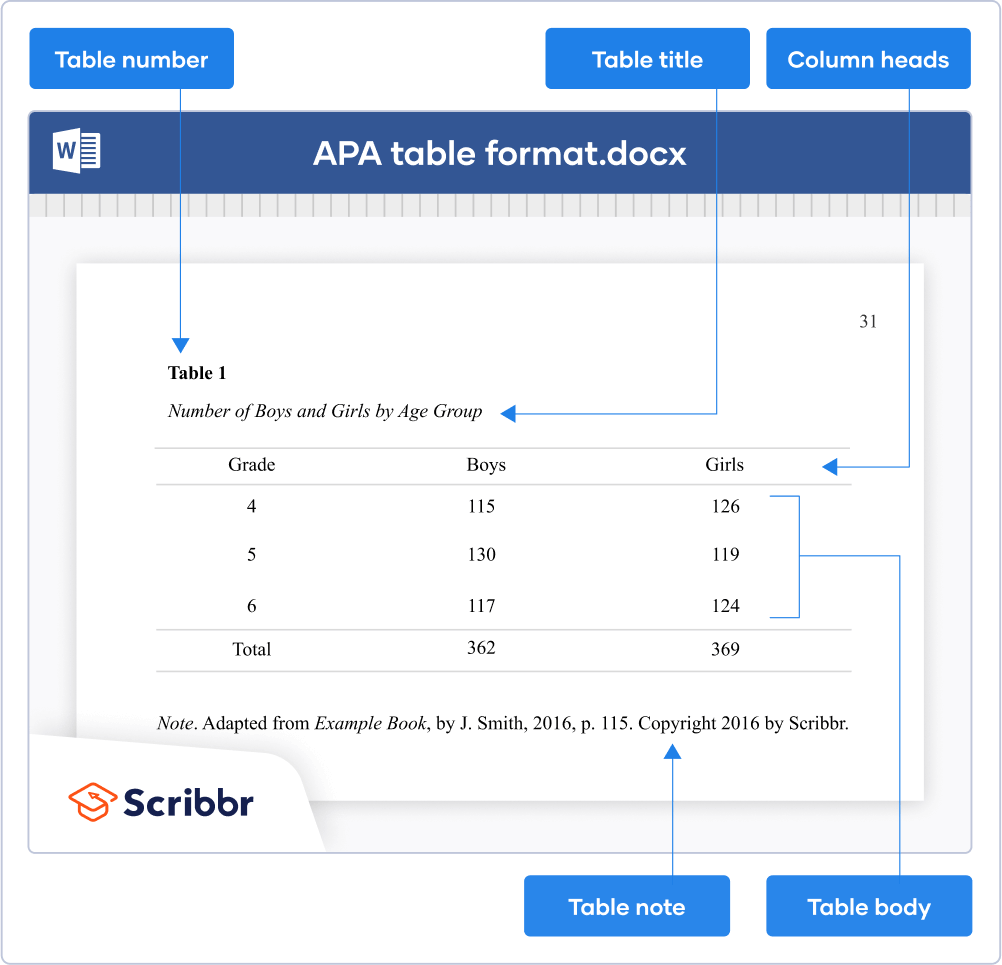

In addition to helping you understand how to cite research, the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association has information about how to format your paper to include tables, figures, and headings that often accompany scientific journal articles.

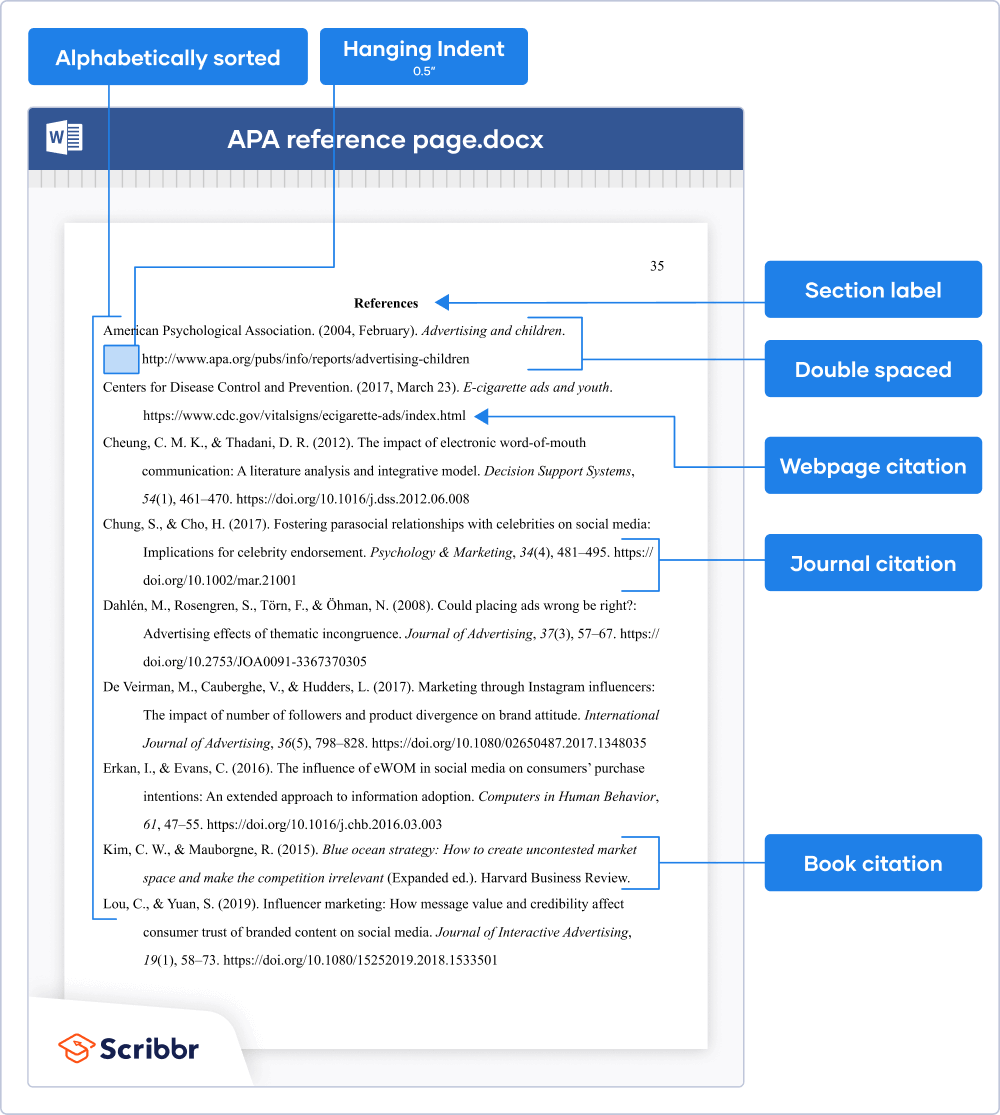

The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association also tells you how to format your reference page. In MLA style, this is the Works Cited page. For APA style, it’s either the Reference List or Reference Page.

This page uses the same font style as the rest of the paper but starts on its own page with a number in the top right corner. The title of the page is bold and centered at the top and should simply read “References.”

List citations in alphabetical order by author’s last name regardless of the type of source. Each citation is double-spaced and has a hanging indent if it goes beyond one line.

Now that you understand how to properly format your APA reference page, learn how to cite a research paper to include on the list.

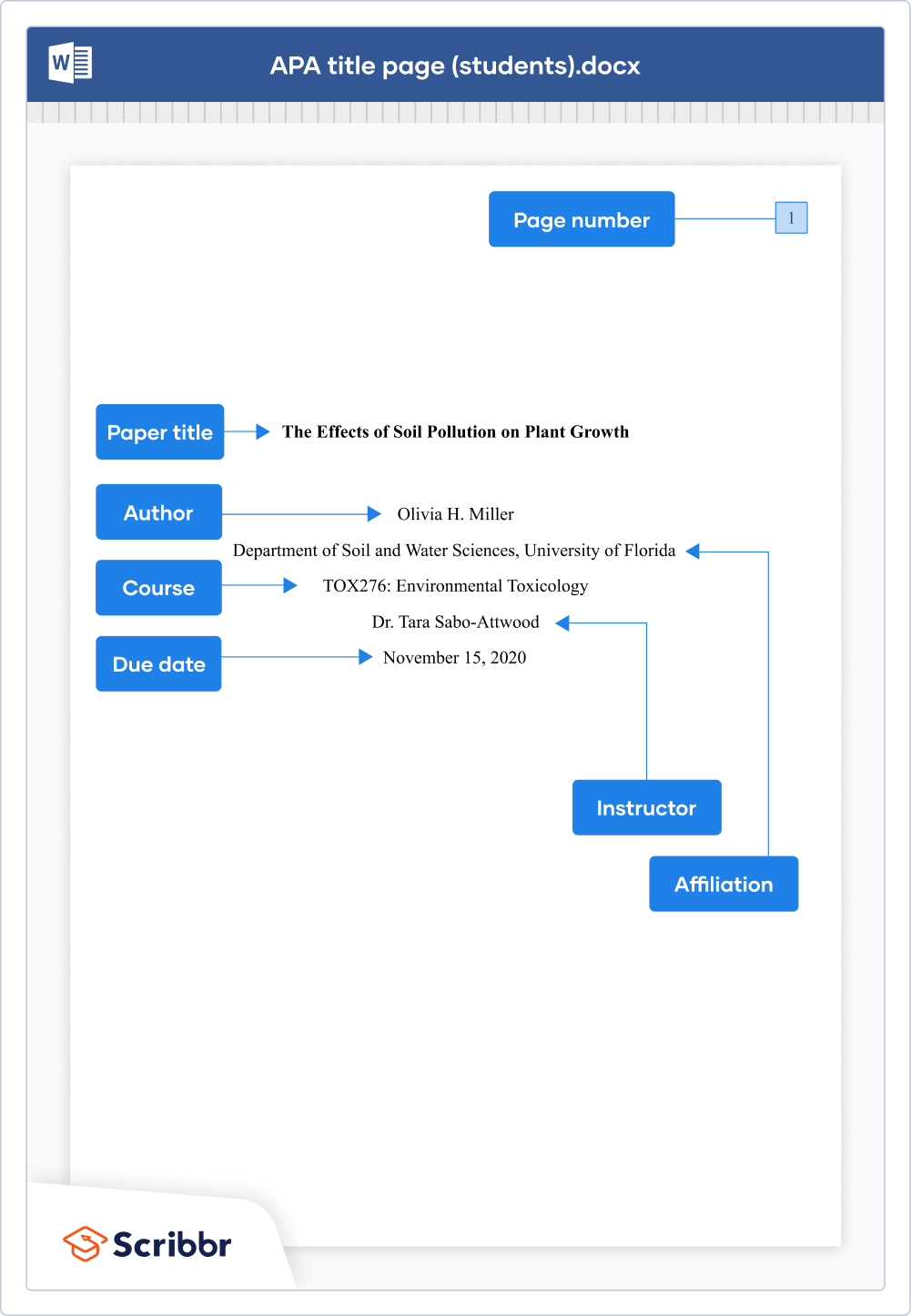

Citing a Research Paper in APA Style

When you use a research paper in your work, you need to include it on your APA references page at the end of your document.

An APA citation includes the same information as the MLA format but in a different order. The citation starts with the author’s last name but only uses their first initial. Then comes the year of publication in parenthesis.

The paper’s title follows, then the title of the journal in italics. You also include the journal volume, issue number, and page numbers. As with MLA citations, include a DOI if you found the research paper online. Here is an example of a published research paper cited in APA format:

Writer, M. (2020). My Research Paper. Research Journal, 3(4), 7-9. doi:12.34/mfs.12.34

If the paper isn’t published in a journal, you can still use it in your work with a proper citation. Here is an example:

Writer, M. (2020). My Research Paper [PDF]. Retrieved from http://websiteused.com

In-Text Citations for a Research Paper in APA Style

In-text citations in the APA format differ from MLA style. You still put it in parenthesis, but you include different information. For APA parentheticals, include the author’s last name and the paper’s year of publication. This method applies when you’re summarizing or paraphrasing the author’s idea. Here is an example of an in-text citation for a research paper in APA style:

Over 80% of the city’s garbage went into the ocean (Writer, 2020).

If you’re using a direct quote from the work you need to include the page number so the reader can find the quotation. Here is an example:

Maria Writer said, “Over 80% of the city’s garbage is going into the ocean” (2020, p. 8).

Chicago Style

Chicago Style got its name from the University of Chicago, where the style originated. Writers use this format for works in the field of history, but you can also use it for the sciences, social sciences, and humanities.

MLA style has a Works Cited page, APA has References, and Chicago Style differs because it includes a Bibliography. The page comes at the end of your work with a page number in the top right corner. The title, “Bibliography,” is bold and centered at the top.

You will single-space your citations, but you’ll add an extra line between each entry. As with the other reference pages, you’ll left-align the work and use a hanging indent when a citation continues onto a second line.

Having an overview of how to format the bibliography will help you understand the citation styles for a research paper.

Citing a Research Paper in Chicago Style

Citations in Chicago Style are a mix of MLA and APA formats. It’s easiest to follow this template:

Writer, Maria. 2020. “My Research Paper.” Research Journal 3 (4): 7-9. doi:12.34/mfs.12.34.

As with other styles, you can reference an unpublished research paper as a document. Here is an example:

Writer, Maria. 2020. My Research Paper. PDF. http://websiteused.com .

In both instances, if there are multiple authors for a paper, list the rest of the authors in normal format. For example:

Author, Alan, Stanley Sample, and Maria Writer. 2020. “My Research Paper.” Research Journal 3 (4): 7-9. doi:12.34/mfs.12.34.

In-Text Citations for a Research Paper in Chicago Style

An in-text citation in Chicago Style is much simpler than both MLA and APA formats. You only need to include the last name of the author and year of publication in parenthesis with no comma in between them. For example:

Almost 80% of the city’s garbage goes into the ocean (Writer 2020).

You’ll include the page number for specificity if you’re quoting the author. Here’s an example:

Maria Writer said, “Over 80% of the city’s garbage is going into the ocean” (2020, 8).

You can also use endnotes in Chicago Style. A citation refers the reader to your source, but an endnote includes a bit of an explanation of why you used it. The information included in an endnote would disrupt the flow of your paper, but it’s still something you want the reader to know.

Make Text Citations Easy

Knowing when you need to cite a source helps you manage your research. Anytime you find information that you’re going to paraphrase, summarize, or quote in your work, you need to cite the source. The full citation will go on your reference page, but you’ll need an in-text citation where you use the information in your paper.

When you’re stating something that is common knowledge , there’s no need to make a citation. Common knowledge is something that your reader would believe without needing proof. You can check if something is common knowledge by searching for it and finding it mentioned, without a citation, in at least five sources.

Once you learn the basics about citing a research paper in MLA, APA, and Chicago Styles, you’ll feel more confident in your work. The important thing is to pay attention to small details, like capitalization, italics and the use of abbreviations. But there’s no need to do it all on your own—Quetext has a citation assistant waiting to help. Give Quetext citation generator a try on your next project.

Sign Up for Quetext Today!

Click below to find a pricing plan that fits your needs.

You May Also Like

Empowering Educators: How AI Detection Enhances Teachers’ Workload

- Posted on March 14, 2024

The Ethical Dimension | Navigating the Challenges of AI Detection in Education

- Posted on March 8, 2024

How to Write a Thesis Statement & Essay Outline

- Posted on February 29, 2024 February 29, 2024

The Crucial Role of Grammar and Spell Check in Student Assignments

- Posted on February 23, 2024 February 23, 2024

Revolutionizing Education: The Role of AI Detection in Academic Integrity

- Posted on February 15, 2024

How Reliable are AI Content Detectors? Which is Most Reliable?

- Posted on February 8, 2024 February 8, 2024

What Is an Article Spinner?

- Posted on February 2, 2024 February 2, 2024

Recognizing & Avoiding Plagiarism in Your Research Paper

- Posted on January 26, 2024 January 26, 2024

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

University Library

Start your research.

- Research Process

- Find Background Info

- Find Sources through the Library

- Evaluate Your Info

- Cite Your Sources

- Evaluate, Write & Cite

- is the right thing to do to give credit to those who had the idea

- shows that you have read and understand what experts have had to say about your topic

- helps people find the sources that you used in case they want to read more about the topic

- provides evidence for your arguments

- is professional and standard practice for students and scholars

What is a Citation?

A citation identifies for the reader the original source for an idea, information, or image that is referred to in a work.

- In the body of a paper, the in-text citation acknowledges the source of information used.

- At the end of a paper, the citations are compiled on a References or Works Cited list. A basic citation includes the author, title, and publication information of the source.

From: Lemieux Library, University of Seattle

Why Should You Cite?

Quoting Are you quoting two or more consecutive words from a source? Then the original source should be cited and the words or phrase placed in quotes.

Paraphrasing If an idea or information comes from another source, even if you put it in your own words , you still need to credit the source. General vs. Unfamiliar Knowledge You do not need to cite material which is accepted common knowledge. If in doubt whether your information is common knowledge or not, cite it. Formats We usually think of books and articles. However, if you use material from web sites, films, music, graphs, tables, etc. you'll also need to cite these as well.

Plagiarism is presenting the words or ideas of someone else as your own without proper acknowledgment of the source. When you work on a research paper and use supporting material from works by others, it's okay to quote people and use their ideas, but you do need to correctly credit them. Even when you summarize or paraphrase information found in books, articles, or Web pages, you must acknowledge the original author.

Citation Style Help

Helpful links:

- MLA , Works Cited : A Quick Guide (a template of core elements)

- CSE (Council of Science Editors)

For additional writing resources specific to styles listed here visit the Purdue OWL Writing Lab

Citation and Bibliography Resources

- How to Write an Annotated Bibliography

- Zotero Basics

- << Previous: Evaluate Your Info

- Next: Evaluate, Write & Cite >>

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License except where otherwise noted.

Land Acknowledgement

The land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, comprised of the descendants of indigenous people taken to missions Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista during Spanish colonization of the Central Coast, is today working hard to restore traditional stewardship practices on these lands and heal from historical trauma.

The land acknowledgement used at UC Santa Cruz was developed in partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Chairman and the Amah Mutsun Relearning Program at the UCSC Arboretum .

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / How to Cite Sources

How to Cite Sources

Here is a complete list for how to cite sources. Most of these guides present citation guidance and examples in MLA, APA, and Chicago.

If you’re looking for general information on MLA or APA citations , the EasyBib Writing Center was designed for you! It has articles on what’s needed in an MLA in-text citation , how to format an APA paper, what an MLA annotated bibliography is, making an MLA works cited page, and much more!

MLA Format Citation Examples

The Modern Language Association created the MLA Style, currently in its 9th edition, to provide researchers with guidelines for writing and documenting scholarly borrowings. Most often used in the humanities, MLA style (or MLA format ) has been adopted and used by numerous other disciplines, in multiple parts of the world.

MLA provides standard rules to follow so that most research papers are formatted in a similar manner. This makes it easier for readers to comprehend the information. The MLA in-text citation guidelines, MLA works cited standards, and MLA annotated bibliography instructions provide scholars with the information they need to properly cite sources in their research papers, articles, and assignments.

- Book Chapter

- Conference Paper

- Documentary

- Encyclopedia

- Google Images

- Kindle Book

- Memorial Inscription

- Museum Exhibit

- Painting or Artwork

- PowerPoint Presentation

- Sheet Music

- Thesis or Dissertation

- YouTube Video

APA Format Citation Examples

The American Psychological Association created the APA citation style in 1929 as a way to help psychologists, anthropologists, and even business managers establish one common way to cite sources and present content.

APA is used when citing sources for academic articles such as journals, and is intended to help readers better comprehend content, and to avoid language bias wherever possible. The APA style (or APA format ) is now in its 7th edition, and provides citation style guides for virtually any type of resource.

Chicago Style Citation Examples

The Chicago/Turabian style of citing sources is generally used when citing sources for humanities papers, and is best known for its requirement that writers place bibliographic citations at the bottom of a page (in Chicago-format footnotes ) or at the end of a paper (endnotes).

The Turabian and Chicago citation styles are almost identical, but the Turabian style is geared towards student published papers such as theses and dissertations, while the Chicago style provides guidelines for all types of publications. This is why you’ll commonly see Chicago style and Turabian style presented together. The Chicago Manual of Style is currently in its 17th edition, and Turabian’s A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations is in its 8th edition.

Citing Specific Sources or Events

- Declaration of Independence

- Gettysburg Address

- Martin Luther King Jr. Speech

- President Obama’s Farewell Address

- President Trump’s Inauguration Speech

- White House Press Briefing

Additional FAQs

- Citing Archived Contributors

- Citing a Blog

- Citing a Book Chapter

- Citing a Source in a Foreign Language

- Citing an Image

- Citing a Song

- Citing Special Contributors

- Citing a Translated Article

- Citing a Tweet

6 Interesting Citation Facts

The world of citations may seem cut and dry, but there’s more to them than just specific capitalization rules, MLA in-text citations , and other formatting specifications. Citations have been helping researches document their sources for hundreds of years, and are a great way to learn more about a particular subject area.

Ever wonder what sets all the different styles apart, or how they came to be in the first place? Read on for some interesting facts about citations!

1. There are Over 7,000 Different Citation Styles

You may be familiar with MLA and APA citation styles, but there are actually thousands of citation styles used for all different academic disciplines all across the world. Deciding which one to use can be difficult, so be sure to ask you instructor which one you should be using for your next paper.

2. Some Citation Styles are Named After People

While a majority of citation styles are named for the specific organizations that publish them (i.e. APA is published by the American Psychological Association, and MLA format is named for the Modern Language Association), some are actually named after individuals. The most well-known example of this is perhaps Turabian style, named for Kate L. Turabian, an American educator and writer. She developed this style as a condensed version of the Chicago Manual of Style in order to present a more concise set of rules to students.

3. There are Some Really Specific and Uniquely Named Citation Styles

How specific can citation styles get? The answer is very. For example, the “Flavour and Fragrance Journal” style is based on a bimonthly, peer-reviewed scientific journal published since 1985 by John Wiley & Sons. It publishes original research articles, reviews and special reports on all aspects of flavor and fragrance. Another example is “Nordic Pulp and Paper Research,” a style used by an international scientific magazine covering science and technology for the areas of wood or bio-mass constituents.

4. More citations were created on EasyBib.com in the first quarter of 2018 than there are people in California.

The US Census Bureau estimates that approximately 39.5 million people live in the state of California. Meanwhile, about 43 million citations were made on EasyBib from January to March of 2018. That’s a lot of citations.

5. “Citations” is a Word With a Long History

The word “citations” can be traced back literally thousands of years to the Latin word “citare” meaning “to summon, urge, call; put in sudden motion, call forward; rouse, excite.” The word then took on its more modern meaning and relevance to writing papers in the 1600s, where it became known as the “act of citing or quoting a passage from a book, etc.”

6. Citation Styles are Always Changing

The concept of citations always stays the same. It is a means of preventing plagiarism and demonstrating where you relied on outside sources. The specific style rules, however, can and do change regularly. For example, in 2018 alone, 46 new citation styles were introduced , and 106 updates were made to exiting styles. At EasyBib, we are always on the lookout for ways to improve our styles and opportunities to add new ones to our list.

Why Citations Matter

Here are the ways accurate citations can help your students achieve academic success, and how you can answer the dreaded question, “why should I cite my sources?”

They Give Credit to the Right People

Citing their sources makes sure that the reader can differentiate the student’s original thoughts from those of other researchers. Not only does this make sure that the sources they use receive proper credit for their work, it ensures that the student receives deserved recognition for their unique contributions to the topic. Whether the student is citing in MLA format , APA format , or any other style, citations serve as a natural way to place a student’s work in the broader context of the subject area, and serve as an easy way to gauge their commitment to the project.

They Provide Hard Evidence of Ideas

Having many citations from a wide variety of sources related to their idea means that the student is working on a well-researched and respected subject. Citing sources that back up their claim creates room for fact-checking and further research . And, if they can cite a few sources that have the converse opinion or idea, and then demonstrate to the reader why they believe that that viewpoint is wrong by again citing credible sources, the student is well on their way to winning over the reader and cementing their point of view.

They Promote Originality and Prevent Plagiarism

The point of research projects is not to regurgitate information that can already be found elsewhere. We have Google for that! What the student’s project should aim to do is promote an original idea or a spin on an existing idea, and use reliable sources to promote that idea. Copying or directly referencing a source without proper citation can lead to not only a poor grade, but accusations of academic dishonesty. By citing their sources regularly and accurately, students can easily avoid the trap of plagiarism , and promote further research on their topic.

They Create Better Researchers

By researching sources to back up and promote their ideas, students are becoming better researchers without even knowing it! Each time a new source is read or researched, the student is becoming more engaged with the project and is developing a deeper understanding of the subject area. Proper citations demonstrate a breadth of the student’s reading and dedication to the project itself. By creating citations, students are compelled to make connections between their sources and discern research patterns. Each time they complete this process, they are helping themselves become better researchers and writers overall.

When is the Right Time to Start Making Citations?

Make in-text/parenthetical citations as you need them.

As you are writing your paper, be sure to include references within the text that correspond with references in a works cited or bibliography. These are usually called in-text citations or parenthetical citations in MLA and APA formats. The most effective time to complete these is directly after you have made your reference to another source. For instance, after writing the line from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities : “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…,” you would include a citation like this (depending on your chosen citation style):

(Dickens 11).

This signals to the reader that you have referenced an outside source. What’s great about this system is that the in-text citations serve as a natural list for all of the citations you have made in your paper, which will make completing the works cited page a whole lot easier. After you are done writing, all that will be left for you to do is scan your paper for these references, and then build a works cited page that includes a citation for each one.

Need help creating an MLA works cited page ? Try the MLA format generator on EasyBib.com! We also have a guide on how to format an APA reference page .

2. Understand the General Formatting Rules of Your Citation Style Before You Start Writing

While reading up on paper formatting may not sound exciting, being aware of how your paper should look early on in the paper writing process is super important. Citation styles can dictate more than just the appearance of the citations themselves, but rather can impact the layout of your paper as a whole, with specific guidelines concerning margin width, title treatment, and even font size and spacing. Knowing how to organize your paper before you start writing will ensure that you do not receive a low grade for something as trivial as forgetting a hanging indent.

Don’t know where to start? Here’s a formatting guide on APA format .

3. Double-check All of Your Outside Sources for Relevance and Trustworthiness First

Collecting outside sources that support your research and specific topic is a critical step in writing an effective paper. But before you run to the library and grab the first 20 books you can lay your hands on, keep in mind that selecting a source to include in your paper should not be taken lightly. Before you proceed with using it to backup your ideas, run a quick Internet search for it and see if other scholars in your field have written about it as well. Check to see if there are book reviews about it or peer accolades. If you spot something that seems off to you, you may want to consider leaving it out of your work. Doing this before your start making citations can save you a ton of time in the long run.

Finished with your paper? It may be time to run it through a grammar and plagiarism checker , like the one offered by EasyBib Plus. If you’re just looking to brush up on the basics, our grammar guides are ready anytime you are.

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

Research Skills Tutorial

- Turning A Topic Into A Research Question

- Getting Background Information About Your Topic

- Portfolio Activity 1

- Types of Information Sources

- Scholarly, Popular and Trade Information Sources

- Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Information Sources

- Current and Retrospective Information Sources

- Information Sources for Different Audiences and Purposes

- Portfolio Activity 2

- Library Databases vs. the Web

- Creating a Concept Chart

- Boolean Operators

- Refining Results by Date, Peer Review and Document Type

- Advanced Searching

- Advanced Searching with Descriptors

- Descriptor Chaining

- Citation Chaining (or Reference Mining)

- Searching Outside the SUNY Empire Library

- Searching Google

- Portfolio Activity 3

- Understanding Search Results

- Saving Search Results

- Portfolio Activity 4

- Credible Sources

- What Does the Information Source Tell You About Itself?

- Reliability

- Some More About Validity

- Portfolio Activity 5

- What Is Citing?

- What Is a Citation?

- Citation Styles

- Citing Tools and Tips

- Practice Activity 6

- Practice Activity 7 - Final Project

What Is A Citation?

When to cite.

A citation is a reference to the source of information used in your research. Any time you directly quote, paraphrase or summarize the essential elements of someone else's idea in your work, an in-text citation should follow. An in-text citation is a brief notation within the text of your paper or presentation which refers the reader to a fuller notation, or end-of-paper citation , that provides all necessary details about that source of information. Direct quotations should be surrounded by quotations marks and are generally used when the idea you want to capture is best expressed by the source. Paraphrasing and summarizing involve rewording an essential idea from someone else's work, usually to either condense the point or to make it better fit your writing style. You do not have to cite your own ideas, unless they have been published. And you do not have to cite common knowledge , or information that most people in your audience would know without having to look it up.

In-Text Citations

In-text citations alert the reader to an idea from an outside source.

Parenthetical Notes

In MLA and APA styles, in-text citations usually appear as parenthetical notes (sometimes called parenthetical documentation ). They are called parenthetical notes because brief information about the source, usually the author's name, year of publication, and page number, is enclosed in parentheses as follows:

MLA style: (Smith 263)

APA style: (Smith, 2013, p. 263)

Parenthetical notes are inserted into the text of the paper at the end of a sentence or paragraph:>

In MLA and APA styles, in-text citations are associated with end-of-paper citations that provide full details about an information source. Note: Different source types and situations require different information within the parentheses. Refer to a style guide for the style you are using for details.

Note Numbers

In Chicago and CSE styles, in-text citations usually appear as superscript numerals, or note numbers , as follows:

These note numbers are associated with full citations that can appear as footnotes (bottom of page), endnotes (end of chapter or paper), or lists of cited references at the end of the paper.

End-of-Paper Citations

End-of-paper citations, as well as footnotes and endnotes, include full details about a source of information. Citations contain different pieces of identifying information about your source depending on what type of source it is. In academic research, your sources will most commonly be articles from scholarly journals, and the citation for an article typically includes:

- article title

- publication information (journal title, date, volume, issue, pages, etc.)

- DOI (digital object identifier).

- URL of the information source itself

- URL of the journal that published the article

There are many other types of sources you might use, including books, book chapters, films, song lyrics, musical scores, interviews, e-mails, blog entries, art works, lectures, websites and more. To determine which details are required for a citation for a particular source type, find that source type within the style guide for the citation style you are using. At the end of your research paper, full citations should be listed in order according to the citation style you are using:

- In MLA style, this list is called a W orks Cited page.

- In APA style, it is called a References page.

- In CSE style, it is called a C ited References page.

- And, in Chicago style, there may be both a Notes page and a Bibliography page.

Citations In Library Databases

When you search the library's databases for articles or e-books, the list of search results you see is actually a list of full citations. Instead of being formatted according to MLA, APA, CSE, or Chicago style, these citations are formatted according to the database vendor's style. It is up to you to take the source information you find in a library database (or elsewhere) and format it according to the citation style you are using.

Accessibility Note

Please note: If you need to request accommodations with content linked to on this guide, on the basis of a disability, please contact Accessibility Resources and Services by emailing them . Requests for accommodations should be submitted as early as possible to allow for sufficient planning. If you have questions, please visit the Accessibility Resources and Services website .

- << Previous: Why Cite?

- Next: Citation Styles >>

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 1:37 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.sunyempire.edu/researchskillstutorial

SpringShare Privacy Policy

- Safety & Security

- ITS Service Desk

- Facilities & Maintenance

- University Policies

- Web Accessibility

- Freedom of Information

© 2023 SUNY Empire State University The Torch logo is a trademark of SUNY Empire State University.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 11. Citing Sources

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A citation is a formal reference to a published or unpublished source that you consulted and obtained information from while writing your research paper. It refers to a source of information that supports a factual statement, proposition, argument, or assertion or any quoted text obtained from a book, article, web site, or any other type of material . In-text citations are embedded within the body of your paper and use a shorthand notation style that refers to a complete description of the item at the end of the paper. Materials cited at the end of a paper may be listed under the heading References, Sources, Works Cited, or Bibliography. Rules on how to properly cite a source depends on the writing style manual your professor wants you to use for the class [e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago, Turabian, etc.]. Note that some disciplines have their own citation rules [e.g., law].

Citations: Overview. OASIS Writing Center, Walden University; Research and Citation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Citing Sources. University Writing Center, Texas A&M University.

Reasons for Citing Your Sources

Reasons for Citing Sources in Your Research Paper

English scientist, Sir Isaac Newton, once wrote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”* Citations support learning how to "see further" through processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time and the subsequent ways this leads to the devarication of new knowledge.

Listed below are specific reasons why citing sources is an important part of doing good research.

- Shows the reader where to find more information . Citations help readers expand their understanding and knowledge about the issues being investigated. One of the most effective strategies for locating authoritative, relevant sources about a research problem is to review materials cited in studies published by other authors. In this way, the sources you cite help the reader identify where to go to examine the topic in more depth and detail.

- Increases your credibility as an author . Citations to the words, ideas, and arguments of scholars demonstrates that you have conducted a thorough review of the literature and, therefore, you are reporting your research results or proposing recommended courses of action from an informed and critically engaged perspective. Your citations offer evidence that you effectively contemplated, evaluated, and synthesized sources of information in relation to your conceptualization of the research problem.

- Illustrates the non-linear and contested nature of knowledge creation . The sources you cite show the reader how you characterized the dynamics of prior knowledge creation relevant to the research problem and how you managed to effectively identify the contested relationships between problems and solutions proposed among scholars. Citations don't just list materials used in your study, they tell a story about how prior knowledge-making emerged from a constant state of creation, renewal, and transformation.

- Reinforces your arguments . Sources cited in your paper provide the evidence that readers need to determine that you properly addressed the “So What?” question. This refers to whether you considered the relevance and significance of the research problem, its implications applied to creating new knowledge, and its importance for improving practice. In this way, citations draw attention to and support the legitimacy and originality of your own ideas.

- Demonstrates that you "listened" to relevant conversations among scholars before joining in . Your citations tell the reader where you developed an understanding of the debates among scholars. They show how you educated yourself about ongoing conversations taking place within relevant communities of researchers before inserting your own ideas and arguments. In peer-reviewed scholarship, most of these conversations emerge within books, research reports, journal articles, and other cited works.

- Delineates alternative approaches to explaining the research problem . If you disagree with prior research assumptions or you believe that a topic has been understudied or you find that there is a gap in how scholars have understood a problem, your citations serve as the source materials from which to analyze and present an alternative viewpoint or to assert that a different course of action should be pursued. In short, the materials you cite serve as the means by which to argue persuasively against long-standing assumptions propagated in prior studies.

- Helps the reader understand contextual aspects of your research . Cited sources help readers understand the specific circumstances, conditions, and settings of the problem being investigated and, by extension, how your arguments can be fully understood and assessed. Citations place your line of reasoning within a specific contextualized framework based on how others have studied the problem and how you interpreted their findings in support of your overall research objectives.

- Frames the development of concepts and ideas within the literature . No topic in the social and behavioral sciences rests in isolation from research that has taken place in the past. Your citations help the reader understand the growth and transformation of the theoretical assumptions, key concepts, and systematic inquiries that emerged prior to your engagement with the research problem.

- Underscores what sources were most important to you . Your citations represent a set of choices made about what you determined to be the most important sources for understanding the topic. They not only list what you discovered, but why it matters and how the materials you chose to cite fit within the broader context of your research design and arguments. As part of an overall assessment of the study’s validity and reliability , the choices you make also helps the reader determine what research may have been excluded.

- Provides evidence of interdisciplinary thinking . An important principle of good research is to extend your review of the literature beyond the predominant disciplinary space where scholars have examined a topic. Citations provide evidence that you have integrated epistemological arguments, observations, and/or the methodological strategies from other disciplines into your paper, thereby demonstrating that you understand the complex, interconnected nature of contemporary research problems.

- Supports critical thinking and independent learning . Evaluating the authenticity, reliability, validity, and originality of prior research is an act of interpretation and introspective reasoning applied to assessing whether a source of information will contribute to understanding the problem in ways that are persuasive and align with your overall research objectives. Reviewing and citing prior studies represents a deliberate act of critically scrutinizing each source as part of your overall assessment of how scholars have confronted the research problem.

- Honors the achievements of others . As Susan Blum recently noted,** citations not only identify sources used, they acknowledge the achievements of scholars within the larger network of research about the topic. Citing sources is a normative act of professionalism within academe and a way to highlight and recognize the work of scholars who likely do not obtain any tangible benefits or monetary value from their research endeavors.

*Vernon. Jamie L. "On the Shoulder of Giants." American Scientist 105 (July-August 2017): 194.

**Blum, Susan D. "In Defense of the Morality of Citation.” Inside Higher Ed , January 29, 2024.

Aksnes, Dag W., Liv Langfeldt, and Paul Wouters. "Citations, Citation Indicators, and Research Quality: An Overview of Basic Concepts and Theories." Sage Open 9 (January-March 2019): https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019829575; Blum, Susan Debra. My Word!: Plagiarism and College Culture . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009; Bretag, Tracey., editor. Handbook of Academic Integrity . Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020; Ballenger, Bruce P. The Curious Researcher: A Guide to Writing Research Papers . 7th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2012; D'Angelo, Barbara J. "Using Source Analysis to Promote Critical Thinking." Research Strategies 18 (Winter 2001): 303-309; Mauer, Barry and John Venecek. “Scholarship as Conversation.” Strategies for Conducting Literary Research, University of Central Florida, 2021; Why Cite? Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, Yale University; Citing Information. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Harvard College Writing Program. Harvard University; Newton, Philip. "Academic Integrity: A Quantitative Study of Confidence and Understanding in Students at the Start of Their Higher Education." Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (2016): 482-497; Referencing More Effectively. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Using Sources. Yale College Writing Center. Yale University; Vosburgh, Richard M. "Closing the Academic-practitioner Gap: Research Must Answer the “SO WHAT” Question." H uman Resource Management Review 32 (March 2022): 100633; When and Why to Cite Sources. Information Literacy Playlists, SUNY, Albany Libraries.

Structure and Writing Style

Referencing your sources means systematically showing what information or ideas you acquired from another author’s work, and identifying where that information come from . You must cite research in order to do research, but at the same time, you must delineate what are your original thoughts and ideas and what are the thoughts and ideas of others. Citations help achieve this. Procedures used to cite sources vary among different fields of study. If not outlined in your course syllabus or writing assignment, always speak with your professor about what writing style for citing sources should be used for the class because it is important to fully understand the citation style to be used in your paper, and to apply it consistently. If your professor defers and tells you to "choose whatever you want, just be consistent," then choose the citation style you are most familiar with or that is appropriate to your major [e.g., use Chicago style if its a history class; use APA if its an education course; use MLA if it is literature or a general writing course].

GENERAL GUIDELINES

1. Are there any reasons I should avoid referencing other people's work? No. If placed in the proper context, r eferencing other people's research is never an indication that your work is substandard or lacks originality. In fact, the opposite is true. If you write your paper without adequate references to previous studies, you are signaling to the reader that you are not familiar with the literature on the topic, thereby, undermining the validity of your study and your credibility as a researcher. Including references in academic writing is one of the most important ways to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of how the research problem has been addressed. It is the intellectual packaging around which you present your thoughts and ideas to the reader.