Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

- Fetal presentation before birth

The way a baby is positioned in the uterus just before birth can have a big effect on labor and delivery. This positioning is called fetal presentation.

Babies twist, stretch and tumble quite a bit during pregnancy. Before labor starts, however, they usually come to rest in a way that allows them to be delivered through the birth canal headfirst. This position is called cephalic presentation. But there are other ways a baby may settle just before labor begins.

Following are some of the possible ways a baby may be positioned at the end of pregnancy.

Head down, face down

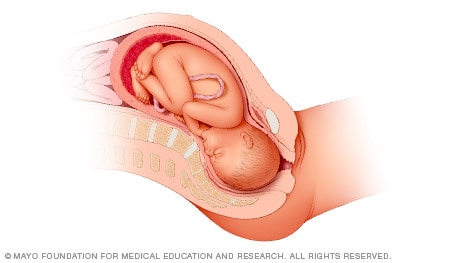

When a baby is head down, face down, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput anterior position. This the most common position for a baby to be born in. With the face down and turned slightly to the side, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the birth canal. It is the easiest way for a baby to be born.

Head down, face up

When a baby is head down, face up, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput posterior position. In this position, it might be harder for a baby's head to go under the pubic bone during delivery. That can make labor take longer.

Most babies who begin labor in this position eventually turn to be face down. If that doesn't happen, and the second stage of labor is taking a long time, a member of the health care team may reach through the vagina to help the baby turn. This is called manual rotation.

In some cases, a baby can be born in the head-down, face-up position. Use of forceps or a vacuum device to help with delivery is more common when a baby is in this position than in the head-down, face-down position. In some cases, a C-section delivery may be needed.

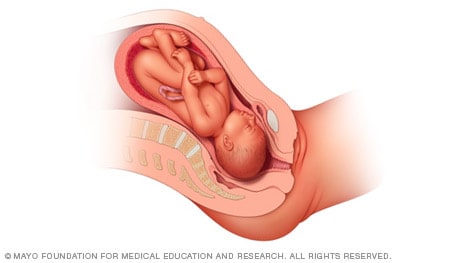

Frank breech

When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a frank breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Most babies in a frank breech position are born by planned C-section.

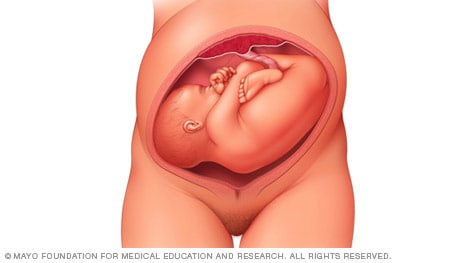

Complete and incomplete breech

A complete breech presentation, as shown below, is when the baby has both knees bent and both legs pulled close to the body. In an incomplete breech, one or both of the legs are not pulled close to the body, and one or both of the feet or knees are below the baby's buttocks. If a baby is in either of these positions, you might feel kicking in the lower part of your belly.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a complete or incomplete breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies in a complete or incomplete breech position are born by planned C-section.

When a baby is sideways — lying horizontal across the uterus, rather than vertical — it's called a transverse lie. In this position, the baby's back might be:

- Down, with the back facing the birth canal.

- Sideways, with one shoulder pointing toward the birth canal.

- Up, with the hands and feet facing the birth canal.

Although many babies are sideways early in pregnancy, few stay this way when labor begins.

If your baby is in a transverse lie during week 37 of your pregnancy, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of your health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a transverse lie, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies who are in a transverse lie are born by C-section.

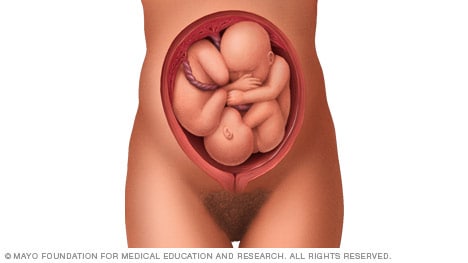

If you're pregnant with twins and only the twin that's lower in the uterus is head down, as shown below, your health care provider may first deliver that baby vaginally.

Then, in some cases, your health care team may suggest delivering the second twin in the breech position. Or they may try to move the second twin into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

Your health care team may suggest delivery by C-section for the second twin if:

- An attempt to deliver the baby in the breech position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to have the baby delivered vaginally in the breech position.

- An attempt to move the baby into a head-down position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to move the baby to a head-down position.

In some cases, your health care team may advise that you have both twins delivered by C-section. That might happen if the lower twin is not head down, the second twin has low or high birth weight as compared to the first twin, or if preterm labor starts.

- Landon MB, et al., eds. Normal labor and delivery. In: Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Holcroft Argani C, et al. Occiput posterior position. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Frequently asked questions: If your baby is breech. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/if-your-baby-is-breech. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Hofmeyr GJ. Overview of breech presentation. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Strauss RA, et al. Transverse fetal lie. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Chasen ST, et al. Twin pregnancy: Labor and delivery. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Cohen R, et al. Is vaginal delivery of a breech second twin safe? A comparison between delivery of vertex and non-vertex second twins. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.2005569.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 31, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Obstetricks

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 3rd trimester pregnancy

- Fetal development: The 3rd trimester

- Overdue pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

- Prenatal care: 3rd trimester

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Getting Pregnant

- Registry Builder

- Baby Products

- Birth Clubs

- See all in Community

- Ovulation Calculator

- How To Get Pregnant

- How To Get Pregnant Fast

- Ovulation Discharge

- Implantation Bleeding

- Ovulation Symptoms

- Pregnancy Symptoms

- Am I Pregnant?

- Pregnancy Tests

- See all in Getting Pregnant

- Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Week by Week

- Pregnant Sex

- Weight Gain Tracker

- Signs of Labor

- Morning Sickness

- COVID Vaccine and Pregnancy

- Fetal Weight Chart

- Fetal Development

- Pregnancy Discharge

- Find Out Baby Gender

- Chinese Gender Predictor

- See all in Pregnancy

- Baby Name Generator

- Top Baby Names 2023

- Top Baby Names 2024

- How to Pick a Baby Name

- Most Popular Baby Names

- Baby Names by Letter

- Gender Neutral Names

- Unique Boy Names

- Unique Girl Names

- Top baby names by year

- See all in Baby Names

- Baby Development

- Baby Feeding Guide

- Newborn Sleep

- When Babies Roll Over

- First-Year Baby Costs Calculator

- Postpartum Health

- Baby Poop Chart

- See all in Baby

- Average Weight & Height

- Autism Signs

- Child Growth Chart

- Night Terrors

- Moving from Crib to Bed

- Toddler Feeding Guide

- Potty Training

- Bathing and Grooming

- See all in Toddler

- Height Predictor

- Potty Training: Boys

- Potty training: Girls

- How Much Sleep? (Ages 3+)

- Ready for Preschool?

- Thumb-Sucking

- Gross Motor Skills

- Napping (Ages 2 to 3)

- See all in Child

- Photos: Rashes & Skin Conditions

- Symptom Checker

- Vaccine Scheduler

- Reducing a Fever

- Acetaminophen Dosage Chart

- Constipation in Babies

- Ear Infection Symptoms

- Head Lice 101

- See all in Health

- Second Pregnancy

- Daycare Costs

- Family Finance

- Stay-At-Home Parents

- Breastfeeding Positions

- See all in Family

- Baby Sleep Training

- Preparing For Baby

- My Custom Checklist

- My Registries

- Take the Quiz

- Best Baby Products

- Best Breast Pump

- Best Convertible Car Seat

- Best Infant Car Seat

- Best Baby Bottle

- Best Baby Monitor

- Best Stroller

- Best Diapers

- Best Baby Carrier

- Best Diaper Bag

- Best Highchair

- See all in Baby Products

- Why Pregnant Belly Feels Tight

- Early Signs of Twins

- Teas During Pregnancy

- Baby Head Circumference Chart

- How Many Months Pregnant Am I

- What is a Rainbow Baby

- Braxton Hicks Contractions

- HCG Levels By Week

- When to Take a Pregnancy Test

- Am I Pregnant

- Why is Poop Green

- Can Pregnant Women Eat Shrimp

- Insemination

- UTI During Pregnancy

- Vitamin D Drops

- Best Baby Forumla

- Postpartum Depression

- Low Progesterone During Pregnancy

- Baby Shower

- Baby Shower Games

Breech, posterior, transverse lie: What position is my baby in?

Fetal presentation, or how your baby is situated in your womb at birth, is determined by the body part that's positioned to come out first, and it can affect the way you deliver. At the time of delivery, 97 percent of babies are head-down (cephalic presentation). But there are several other possibilities, including feet or bottom first (breech) as well as sideways (transverse lie) and diagonal (oblique lie).

Fetal presentation and position

During the last trimester of your pregnancy, your provider will check your baby's presentation by feeling your belly to locate the head, bottom, and back. If it's unclear, your provider may do an ultrasound or an internal exam to feel what part of the baby is in your pelvis.

Fetal position refers to whether the baby is facing your spine (anterior position) or facing your belly (posterior position). Fetal position can change often: Your baby may be face up at the beginning of labor and face down at delivery.

Here are the many possibilities for fetal presentation and position in the womb.

Medical illustrations by Jonathan Dimes

Head down, facing down (anterior position)

A baby who is head down and facing your spine is in the anterior position. This is the most common fetal presentation and the easiest position for a vaginal delivery.

This position is also known as "occiput anterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the front (anterior) of your pelvis.

Head down, facing up (posterior position)

In the posterior position , your baby is head down and facing your belly. You may also hear it called "sunny-side up" because babies who stay in this position are born facing up. But many babies who are facing up during labor rotate to the easier face down (anterior) position before birth.

Posterior position is formally known as "occiput posterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the back (posterior) of your pelvis.

Frank breech

In the frank breech presentation, both the baby's legs are extended so that the feet are up near the face. This is the most common type of breech presentation. Breech babies are difficult to deliver vaginally, so most arrive by c-section .

Some providers will attempt to turn your baby manually to the head down position by applying pressure to your belly. This is called an external cephalic version , and it has a 58 percent success rate for turning breech babies. For more information, see our article on breech birth .

Complete breech

A complete breech is when your baby is bottom down with hips and knees bent in a tuck or cross-legged position. If your baby is in a complete breech, you may feel kicking in your lower abdomen.

Incomplete breech

In an incomplete breech, one of the baby's knees is bent so that the foot is tucked next to the bottom with the other leg extended, positioning that foot closer to the face.

Single footling breech

In the single footling breech presentation, one of the baby's feet is pointed toward your cervix.

Double footling breech

In the double footling breech presentation, both of the baby's feet are pointed toward your cervix.

Transverse lie

In a transverse lie, the baby is lying horizontally in your uterus and may be facing up toward your head or down toward your feet. Babies settle this way less than 1 percent of the time, but it happens more commonly if you're carrying multiples or deliver before your due date.

If your baby stays in a transverse lie until the end of your pregnancy, it can be dangerous for delivery. Your provider will likely schedule a c-section or attempt an external cephalic version , which is highly successful for turning babies in this position.

Oblique lie

In rare cases, your baby may lie diagonally in your uterus, with his rump facing the side of your body at an angle.

Like the transverse lie, this position is more common earlier in pregnancy, and it's likely your provider will intervene if your baby is still in the oblique lie at the end of your third trimester.

Was this article helpful?

What to know if your baby is breech

What's a sunny-side up baby?

What happens to your baby right after birth

How your twins’ fetal positions affect labor and delivery

BabyCenter's editorial team is committed to providing the most helpful and trustworthy pregnancy and parenting information in the world. When creating and updating content, we rely on credible sources: respected health organizations, professional groups of doctors and other experts, and published studies in peer-reviewed journals. We believe you should always know the source of the information you're seeing. Learn more about our editorial and medical review policies .

Ahmad A et al. 2014. Association of fetal position at onset of labor and mode of delivery: A prospective cohort study. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 43(2):176-182. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23929533 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Gray CJ and Shanahan MM. 2019. Breech presentation. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448063/ Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Hankins GD. 1990. Transverse lie. American Journal of Perinatology 7(1):66-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2131781 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Medline Plus. 2020. Your baby in the birth canal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002060.htm Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Where to go next

Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

- IN THIS TOPIC

Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

, MD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Variations in Fetal Position and Presentation

- 3D Models (0)

- Calculators (0)

- Lab Test (0)

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus’s body that leads the way out through the birth canal (called the presenting part). Usually, the head leads the way, but sometimes the buttocks (breech presentation), shoulder, or face leads the way.

Position refers to whether the fetus is facing backward (occiput anterior) or forward (occiput posterior). The occiput is a bone at the back of the baby's head. Therefore, facing backward is called occiput anterior (facing the mother’s back and facing down when the mother lies on her back). Facing forward is called occiput posterior (facing toward the mother's pubic bone and facing up when the mother lies on her back).

Lie refers to the angle of the fetus in relation to the mother and the uterus. Up-and-down (with the baby's spine parallel to mother's spine, called longitudinal) is normal, but sometimes the lie is sideways (transverse) or at an angle (oblique).

For these aspects of fetal positioning, the combination that is the most common, safest, and easiest for the mother to deliver is the following:

Head first (called vertex or cephalic presentation)

Facing backward (occiput anterior position)

Spine parallel to mother's spine (longitudinal lie)

Neck bent forward with chin tucked

Arms folded across the chest

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible.

Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when

The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion).

The fetus has a birth defect Overview of Birth Defects Birth defects, also called congenital anomalies, are physical abnormalities that occur before a baby is born. They are usually obvious within the first year of life. The cause of many birth... read more .

There is more than one fetus (multiple gestation).

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

Some variations in position and presentation that make delivery difficult occur frequently.

Occiput posterior position

In occiput posterior position (sometimes called sunny-side up), the fetus is head first (vertex presentation) but is facing forward (toward the mother's pubic bone—that is, facing up when the mother lies on her back). This is a very common position that is not abnormal, but it makes delivery more difficult than when the fetus is in the occiput anterior position (facing toward the mother's spine—that is facing down when the mother lies on her back).

Breech presentation

In breech presentation, the baby's buttocks or sometimes the feet are positioned to deliver first (before the head).

When delivered vaginally, babies that present buttocks first are more at risk of injury or even death than those that present head first.

The reason for the risks to babies in breech presentation is that the baby's hips and buttocks are not as wide as the head. Therefore, when the hips and buttocks pass through the cervix first, the passageway may not be wide enough for the head to pass through. In addition, when the head follows the buttocks, the neck may be bent slightly backwards. The neck being bent backward increases the width required for delivery as compared to when the head is angled forward with the chin tucked, which is the position that is easiest for delivery. Thus, the baby’s body may be delivered and then the head may get caught and not be able to pass through the birth canal. When the baby’s head is caught, this puts pressure on the umbilical cord in the birth canal, so that very little oxygen can reach the baby. Brain damage due to lack of oxygen is more common among breech babies than among those presenting head first.

Breech presentation is more likely to occur in the following circumstances:

Labor starts too soon (preterm labor).

Sometimes the doctor can turn the fetus to be head first before labor begins by doing a procedure that involves pressing on the pregnant woman’s abdomen and trying to turn the baby around. Trying to turn the baby is called an external cephalic version and is usually done at 37 or 38 weeks of pregnancy. Sometimes women are given a medication (such as terbutaline ) during the procedure to prevent contractions.

Other presentations

In face presentation, the baby's neck arches back so that the face presents first rather than the top of the head.

In brow presentation, the neck is moderately arched so that the brow presents first.

Usually, fetuses do not stay in a face or brow presentation. These presentations often change to a vertex (top of the head) presentation before or during labor. If they do not, a cesarean delivery is usually recommended.

In transverse lie, the fetus lies horizontally across the birth canal and presents shoulder first. A cesarean delivery is done, unless the fetus is the second in a set of twins. In such a case, the fetus may be turned to be delivered through the vagina.

Was This Page Helpful?

Test your knowledge

Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada)—dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the MSD Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge .

- Permissions

- Cookie Settings

- Terms of use

- Veterinary Edition

- IN THIS TOPIC

28.4 Changes During Pregnancy, Labor, and Birth

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how estrogen, progesterone, and hCG are involved in maintaining pregnancy

- List the contributors to weight gain during pregnancy

- Describe the major changes to the maternal digestive, circulatory, and integumentary systems during pregnancy

- Summarize the events leading to labor

- Identify and describe each of the three stages of childbirth

A full-term pregnancy lasts approximately 270 days (approximately 38.5 weeks) from conception to birth. Because it is easier to remember the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP) than to estimate the date of conception, obstetricians set the due date as 284 days (approximately 40.5 weeks) from the LMP. This assumes that conception occurred on day 14 of the menstrual cycle, which is usually a good approximation. The 40 weeks of an average pregnancy are usually discussed in terms of three trimesters , each approximately 13 weeks. During the second and third trimesters, the pre-pregnancy uterus—about the size of a fist—grows dramatically to contain the fetus, causing a number of anatomical changes in the pregnant person ( Figure 28.18 ).

Effects of Hormones

Virtually all of the effects of pregnancy can be attributed in some way to the influence of hormones—particularly estrogens, progesterone, and hCG. During weeks 7–12 from the LMP, the pregnancy hormones are primarily generated by the corpus luteum. Progesterone secreted by the corpus luteum stimulates the production of decidual cells of the endometrium that nourish the blastocyst before placentation. As the placenta develops and the corpus luteum degenerates during weeks 12–17, the placenta gradually takes over as the endocrine organ of pregnancy.

The placenta converts weak androgens secreted by the maternal and fetal adrenal glands to estrogens, which are necessary for pregnancy to progress. Estrogen levels climb throughout the pregnancy, increasing 30-fold by childbirth. Estrogens have the following actions:

- They suppress FSH and LH production, effectively preventing ovulation. (This function is the biological basis of hormonal birth control pills.)

- They induce the growth of fetal tissues and are necessary for the maturation of the fetal lungs and liver.

- They promote fetal viability by regulating progesterone production and triggering fetal synthesis of cortisol, which helps with the maturation of the lungs, liver, and endocrine organs such as the thyroid gland and adrenal gland.

- They stimulate maternal tissue growth, leading to uterine enlargement and mammary duct expansion and branching.

Relaxin, another hormone secreted by the corpus luteum and then by the placenta, helps prepare the body for childbirth. It increases the elasticity of the symphysis pubis joint and pelvic ligaments, making room for the growing fetus and allowing expansion of the pelvic outlet for childbirth. Relaxin also helps dilate the cervix during labor.

The placenta takes over the synthesis and secretion of progesterone throughout pregnancy as the corpus luteum degenerates. Like estrogen, progesterone suppresses FSH and LH. It also inhibits uterine contractions, protecting the fetus from preterm birth. This hormone decreases in late gestation, allowing uterine contractions to intensify and eventually progress to true labor. The placenta also produces hCG. In addition to promoting survival of the corpus luteum, hCG stimulates the male fetal gonads to secrete testosterone, which is essential for the development of the male reproductive system.

The anterior pituitary enlarges and ramps up its hormone production during pregnancy, raising the levels of thyrotropin, prolactin, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Thyrotropin, in conjunction with placental hormones, increases the production of thyroid hormone, which raises the maternal metabolic rate. This can markedly augment a pregnant person's appetite and cause hot flashes. Prolactin stimulates enlargement of the mammary glands in preparation for milk production. ACTH stimulates maternal cortisol secretion, which contributes to fetal protein synthesis. In addition to the pituitary hormones, increased parathyroid levels mobilize calcium from maternal bones for fetal use.

Weight Gain

The second and third trimesters of pregnancy are associated with dramatic changes in maternal anatomy and physiology. The most obvious anatomical sign of pregnancy is the dramatic enlargement of the abdominal region, coupled with weight gain. This weight results from the growing fetus as well as the enlarged uterus, amniotic fluid, and placenta. Additional breast tissue and dramatically increased blood volume also contribute to weight gain ( Table 28.2 ). Surprisingly, fat storage accounts for only approximately 2.3 kg (5 lbs) in a normal pregnancy and serves as a reserve for the increased metabolic demand of breastfeeding.

During the first trimester, a pregnant person does not need to consume additional calories to maintain a healthy pregnancy. However, a weight gain of approximately 0.45 kg (1 lb) per month is common. During the second and third trimesters, the appetite increases, but it is only necessary to consume an additional 300 calories per day to support the growing fetus. Most pregnant people gain approximately 0.45 kg (1 lb) per week.

Changes in Organ Systems During Pregnancy

As the body adapts to pregnancy, characteristic physiologic changes occur. These changes can sometimes prompt symptoms often referred to collectively as the common discomforts of pregnancy.

Digestive and Urinary System Changes

Nausea and vomiting, sometimes triggered by an increased sensitivity to odors, are common during the first few weeks to months of pregnancy. This phenomenon is often referred to as “morning sickness,” although the nausea may persist all day. The source of pregnancy nausea is thought to be the increased circulation of pregnancy-related hormones, specifically circulating estrogen, progesterone, and hCG. Decreased intestinal peristalsis may also contribute to nausea. By about week 12 of pregnancy, nausea typically subsides.

A common gastrointestinal complaint during the later stages of pregnancy is gastric reflux, or heartburn, which results from the upward, constrictive pressure of the growing uterus on the stomach. The same decreased peristalsis that may contribute to nausea in early pregnancy is also thought to be responsible for pregnancy-related constipation as pregnancy progresses.

The downward pressure of the uterus also compresses the urinary bladder, leading to frequent urination. The problem is exacerbated by increased urine production. In addition, the maternal urinary system processes both maternal and fetal wastes, further increasing the total volume of urine.

Circulatory System Changes

Blood volume increases substantially during pregnancy, so that by childbirth, it exceeds its preconception volume by 30 percent, or approximately 1–2 liters. The greater blood volume helps to manage the demands of fetal nourishment and fetal waste removal. In conjunction with increased blood volume, the pulse and blood pressure also rise moderately during pregnancy. As the fetus grows, the uterus compresses underlying pelvic blood vessels, hampering venous return from the legs and pelvic region. As a result, many pregnant people develop varicose veins or hemorrhoids.

Respiratory System Changes

During the second half of pregnancy, the respiratory minute volume (volume of gas inhaled or exhaled by the lungs per minute) increases by 50 percent to compensate for the oxygen demands of the fetus and the increased maternal metabolic rate. The growing uterus exerts upward pressure on the diaphragm, decreasing the volume of each inspiration and potentially causing shortness of breath, or dyspnea. During the last several weeks of pregnancy, the pelvis becomes more elastic, and the fetus descends lower in a process called lightening . This typically ameliorates dyspnea.

The respiratory mucosa swell in response to increased blood flow during pregnancy, leading to nasal congestion and nose bleeds, particularly when the weather is cold and dry. Humidifier use and increased fluid intake are often recommended to counteract congestion.

Integumentary System Changes

The dermis stretches extensively to accommodate the growing uterus, breast tissue, and fat deposits on the thighs and hips. Torn connective tissue beneath the dermis can cause striae (stretch marks) on the abdomen, which appear as red or purple marks during pregnancy that fade to a silvery white color in the months after childbirth.

An increase in melanocyte-stimulating hormone, in conjunction with estrogens, darkens the areolae and creates a line of pigment from the umbilicus to the pubis called the linea nigra ( Figure 28.19 ). Melanin production during pregnancy may also darken or discolor skin on the face to create a chloasma, or “mask of pregnancy.”

Physiology of Labor

Childbirth, or parturition , typically occurs within a week of the due date, unless the pregnancy involves more than one fetus, which usually causes labor to begin early. As a pregnancy progresses into its final weeks, several physiological changes occur in response to hormones that trigger labor.

First, recall that progesterone inhibits uterine contractions throughout the first several months of pregnancy. As the pregnancy enters its seventh month, progesterone levels plateau and then drop. Estrogen levels, however, continue to rise in the maternal circulation ( Figure 28.20 ). The increasing ratio of estrogen to progesterone makes the myometrium (the uterine smooth muscle) more sensitive to stimuli that promote contractions (because progesterone no longer inhibits them). Moreover, in the eighth month of pregnancy, fetal cortisol rises, which boosts estrogen secretion by the placenta and further overpowers the uterine-calming effects of progesterone. Some people may feel the result of the decreasing levels of progesterone in late pregnancy as weak and irregular peristaltic Braxton Hicks contractions , also called false labor. These contractions can often be relieved with rest or hydration.

A common sign that labor will be short is the so-called “bloody show.” During pregnancy, a plug of mucus accumulates in the cervical canal, blocking the entrance to the uterus. Approximately 1–2 days prior to the onset of true labor, this plug loosens and is expelled, along with a small amount of blood.

Meanwhile, the posterior pituitary has been boosting its secretion of oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates the contractions of labor. At the same time, the myometrium increases its sensitivity to oxytocin by expressing more receptors for this hormone. As labor nears, oxytocin begins to stimulate stronger, more painful uterine contractions, which—in a positive feedback loop—stimulate the secretion of prostaglandins from fetal membranes. Like oxytocin, prostaglandins also enhance uterine contractile strength. The fetal pituitary also secretes oxytocin, which increases prostaglandins even further. Given the importance of oxytocin and prostaglandins to the initiation and maintenance of labor, it is not surprising that, when a pregnancy is not progressing to labor and needs to be induced, a pharmaceutical version of these compounds (called pitocin) is administered by intravenous drip.

Finally, stretching of the myometrium and cervix by a full-term fetus in the vertex (head-down) position is regarded as a stimulant to uterine contractions. The sum of these changes initiates the regular contractions known as true labor , which become more powerful and more frequent with time. The pain of labor is attributed to myometrial hypoxia during uterine contractions.

Stages of Childbirth

The process of childbirth can be divided into three stages: cervical dilation, expulsion of the newborn, and afterbirth ( Figure 28.21 ).

Cervical Dilation

For vaginal birth to occur, the cervix must dilate fully to 10 cm in diameter—wide enough to deliver the newborn’s head. The dilation stage is the longest stage of labor and typically takes 6–12 hours. However, it varies widely and may take minutes, hours, or days, depending in part on whether the person has given birth before; in each subsequent labor, this stage tends to be shorter.

True labor progresses in a positive feedback loop in which uterine contractions stretch the cervix, causing it to dilate and efface, or become thinner. Cervical stretching induces reflexive uterine contractions that dilate and efface the cervix further. In addition, cervical dilation boosts oxytocin secretion from the pituitary, which in turn triggers more powerful uterine contractions. When labor begins, uterine contractions may occur only every 3–30 minutes and last only 20–40 seconds; however, by the end of this stage, contractions may occur as frequently as every 1.5–2 minutes and last for a full minute.

Each contraction sharply reduces oxygenated blood flow to the fetus. For this reason, it is critical that a period of relaxation occur after each contraction. Fetal distress, measured as a sustained decrease or increase in the fetal heart rate, can result from severe contractions that are too powerful or lengthy for oxygenated blood to be restored to the fetus. Such a situation can be cause for an emergency birth with vacuum, forceps, or surgically by Caesarian section.

The amniotic membranes rupture before the onset of labor in about 12 percent of people; they typically rupture at the end of the dilation stage in response to excessive pressure from the fetal head entering the birth canal.

Expulsion Stage

The expulsion stage begins when the fetal head enters the birth canal and ends with birth of the newborn. It typically takes up to 2 hours, but it can last longer or be completed in minutes, depending in part on the orientation of the fetus. The vertex presentation known as the occiput anterior vertex is the most common presentation and is associated with the greatest ease of vaginal birth. The fetus faces the maternal spinal cord and the smallest part of the head (the posterior aspect called the occiput) exits the birth canal first.

In fewer than 5 percent of births, the infant is oriented in the breech presentation, or buttocks down. In a complete breech, both legs are crossed and oriented downward. In a frank breech presentation, the legs are oriented upward. Before the 1960s, it was common for breech presentations to be delivered vaginally. Today, most breech births are accomplished by Caesarian section.

Vaginal birth is associated with significant stretching of the vaginal canal, the cervix, and the perineum. Until recent decades, it was routine procedure for an obstetrician to numb the perineum and perform an episiotomy , an incision in the posterior vaginal wall and perineum. The perineum is now more commonly allowed to tear on its own during birth. Both an episiotomy and a perineal tear need to be sutured shortly after birth to ensure optimal healing. Although suturing the jagged edges of a perineal tear may be more difficult than suturing an episiotomy, tears heal more quickly, are less painful, and are associated with less damage to the muscles around the vagina and rectum.

Upon birth of the newborn’s head, an obstetrician will aspirate mucus from the mouth and nose before the newborn’s first breath. Once the head is birthed, the rest of the body usually follows quickly. The umbilical cord is then double-clamped, and a cut is made between the clamps. This completes the second stage of childbirth.

The delivery of the placenta and associated membranes, commonly referred to as the afterbirth , marks the final stage of childbirth. After expulsion of the newborn, the myometrium continues to contract. This movement shears the placenta from the back of the uterine wall. It is then easily delivered through the vagina. Continued uterine contractions then reduce blood loss from the site of the placenta. Delivery of the placenta marks the beginning of the postpartum period—the period of approximately 6 weeks immediately following childbirth during which the body gradually returns to a non-pregnant state. If the placenta does not birth spontaneously within approximately 30 minutes, it is considered retained, and the obstetrician may attempt manual removal. If this is not successful, surgery may be required.

It is important that the obstetrician examines the expelled placenta and fetal membranes to ensure that they are intact. If fragments of the placenta remain in the uterus, they can cause postpartum hemorrhage. Uterine contractions continue for several hours after birth to return the uterus to its pre-pregnancy size in a process called involution , which also allows the abdominal organs to return to their pre-pregnancy locations. Breastfeeding facilitates this process.

Although postpartum uterine contractions limit blood loss from the detachment of the placenta, the person who has recently given birth does experience a postpartum vaginal discharge called lochia . This is made up of uterine lining cells, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and other debris. Thick, dark, lochia rubra (red lochia) typically continues for 2–3 days, and is replaced by lochia serosa, a thinner, pinkish form that continues until about the tenth postpartum day. After this period, a scant, creamy, or watery discharge called lochia alba (white lochia) may continue for another 1–2 weeks.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble, Peter DeSaix

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Anatomy and Physiology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 20, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/28-4-changes-during-pregnancy-labor-and-birth

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Vaginal delivery.

Ninad M. Desai ; Alexander Tsukerman .

Affiliations

Last Update: July 24, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Vaginal delivery is safest for the fetus and for the mother when the newborn is full-term at the gestational age of 37 to 42 weeks. Vaginal delivery is preferred considering the morbidity and the mortality associated with operative cesarean births has increased over time. This activity outlines the process of vaginal delivery, the technique, and preparation required to successfully accomplish a vaginal delivery, and reviews the role of an interprofessional team in managing labor and proving care for patients who undergo vaginal delivery as a means of childbirth.

- Outline the typical course of a patient undergoing vaginal delivery.

- Identify the most common adverse events associated with vaginal delivery.

- Summarize the risks associated with vaginal delivery.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients undergoing vaginal delivery.

- Introduction

Vaginal delivery is safest for the fetus and the mother when the newborn is full-term at the gestational age of 37 to 42 weeks. Vaginal delivery is preferred considering the morbidity and the mortality associated with operative cesarean births has increased over time. [1] Approximately 80% of all singleton vaginal deliveries are at full-term via spontaneous labor, whereas 11% are preterm, and 10% are post-term. [2] Of note, with the advent of operative delivery modalities and surgical delivery modalities, the number of patients who reach spontaneous labor has decreased over time, and the induction of labor has increased. [3]

The labor leading to the delivery is divided into 3 stages, and each stage requires specific management. Complications arise during each of the three stages, which can lead to the conversion of the anticipated vaginal delivery to operative cesarean delivery. According to the latest published data, in the USA, in 2017, there were 3,855,500 births, and 68% (2,621,010) of those were vaginal deliveries. The preterm birth rate was 9.9%, and the population’s birth rate was 11.8 per 1000. [4]

- Anatomy and Physiology

The labor leading to delivery of a full-term pregnancy is divided into three stages. The management of each stage varies, and exam findings during each of the stages can help identify short-term and long-term complications for the anticipated vaginal delivery such as fetal distress and hypoxemia, cord prolapse, placental abruption, uterine rupture, permanent disability, and maternal and/or fetal death. [5]

The first stage of labor is the longest stage of labor; it is the result of progressive and rhythmic uterine contraction which causes the cervix to dilate. The first stage of labor is divided into two sub-stages. The first sub-stage is known as the latent phase, which can last for several hours and starts from the cervical size of 0 cm to dilation of the cervix to 6 cm. The second sub-stage is known as the active phase, which includes the time from the end of the latent phase to the complete dilation of the cervix. This phase is rapid; in nulliparous women, the cervix dilates at an approximate rate of 1.00 cm/hour. It dilates slightly faster at a rate of 1.2 cm/hour in multiparous women. [6]

The second stage of labor includes the time from complete cervical dilation, which is the end of the first stage to delivery of the fetus. Duration of this phase is variable and can last from minutes to hours; however, the maximum amount of time that a woman can be in this phase of labor depends on the parity of the patient and whether the patient has an epidural catheter placed for anesthesia. [7]

During this stage, three clinical parameters are important to be aware of, which include fetal presentation, fetal station, and fetal position. The fetal presentation is dictated by which fetal body part first passes through the birth canal; most commonly, this is the occiput or the vertex of the head. The fetal station is determined by the relationship between the fetal head and maternal ischial spines; the station is defined from a range of -5 to +5, and 0 indicates that the fetal head is level with the maternal ischial spines. The fetal position is defined as the position of the top of the fetus’ head in comparison to the plane of the maternal ischial spines when it is born. The vertex, which is the top of the fetus’ head, normal rotates in either direction during the internal rotation portion of the cardinal movements during childbirth. [3]

There are six cardinal movements of childbirth, all of which occur during the second stage of labor. The first of these movements is engagement, which occurs when the head of the fetus enters the lower pelvis. Then, there is flexion of the head, which enables the occiput of the head of the fetus to be in a presentation position. This flexion is then followed by descent when the fetus descends through the birth canal through the pelvis. Once the descent is complete, there is internal rotation, which enables the vertex of the fetal head to rotate away from the ischial spines located laterally. Then, there is an extension of the head, which allows the fetal head to pass the maternal pubic symphysis, and finally, there is external rotation of the head, which allows the anterior shoulder to be delivered. The second stage of labor ends once the fetus is delivered. [3]

The final stage of labor includes the time after the child is born to the delivery of the placenta. The duration of this phase is approximately 30 minutes; [8] during this time, as the uterus contracts, the placenta separates from the endometrium. This process begins at the lower pole of the placenta, and progress is along with the adjacent sites of placental attachment. The continual uterine contraction causes a wave-like separation in the upward direction, which causes the most superior portion of the placenta to detach last. Signs of placental detachment include a sudden gush of blood, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and cephalad movement of the uterine fundus, which becomes firm and globular once the placenta detaches. The third stage of labor concludes once the placenta completely separates and is delivered. [9]

- Indications

For full-term pregnancies, vaginal delivery is indicated when spontaneous labor occurs or if amniotic and chorionic membranes rupture. In addition, for complicated gestations or for post-term pregnancies, induction of labor is indicated, which is also an indication for vaginal delivery.

For women in spontaneous labor, the consensus in the review of the literature reveals that if the woman has regular contractions that require her focus and attention combined with either sufficient effacement (greater than or equal to 80%) and/or 4-5 cm of cervical dilation, the woman is in spontaneous labor and should be admitted to the hospital for a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. It is important to note that woman near labor can feel regular contractions, but can present without cervical effacement or dilation and can be discharged with a follow up after routine monitoring of the fetus’ heart rate and monitoring contractions with a tocodynamometer. Subsequently, some women with cervical dilation or effacement without sufficient spontaneous contractions can be admitted for augmentation and induction of labor using oxytocin. [1]

The rupture of membranes is another indication of vaginal delivery. This may be indicated by a sudden gush of watery-fluid reported by the mother, which may be associated with a uterine contraction. Not all vaginal fluid is amniotic fluid, and this can be confirmed by multiple modalities, such as the pH of the fluid, microscopic visualization for the amniotic fluid for ferning, fetal fibronectin assays, and amniotic fluid nitrazine tests. Rupture of membranes at term gestation is an indication for vaginal delivery. [10] Management of a patient's preterm premature rupture of membranes is dependent on the gestation of pregnancy, among other maternofetal characteristics.

Certain conditions necessitate the induction of labor as timely delivery of pregnancy is important to peripartum outcomes of both the mother and fetus. Conditions such as post-term pregnancy (defined as gestation that is greater than 42 weeks and 0 days), [11] pre-labor rupture of membranes, gestational hypertensive disorders (preeclampsia, eclampsia), HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome, fetal demise, fetal growth restriction, chorioamnionitis, oligohydramnios, placental abruption, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, among other conditions are all indications for labor and vaginal delivery. [3]

- Contraindications

Vaginal delivery is the preferred method for childbirth; however, there are certain conditions when vaginal delivery is contraindicated. Certain conditions require immediate conversion of vaginal delivery to an emergent cesarean section for childbirth, while some conditions can spontaneously resolve, and trial of vaginal delivery can be attempted.

Conditions that require prompt cesarean section and are contraindications to vaginal delivery can be categorized by the system; certain presentations such as footling breech, frank breech, complete breech, and cord prolapse are indications for emergent conversion to cesarean section. [12] Pathologies associated with malposition of the fetus, such as face presentation with mentum (chin in the direction of the maternal sacrum) posterior, transverse lie or shoulder presentation, and occiput posterior, should be converted to an abdominal delivery. [13] Twin gestations when presenting twin is in a breech position, conjoined twins and mono-amniotic twins are contraindications for vaginal delivery. [14] Abnormal placenta positions such as placenta previa, known placenta accreta, or history of uterine rupture are conditions that are contraindications for vaginal delivery. [15] Infection such as active genital herpes outbreak is also an absolute contraindication for vaginal delivery. [16] In the USA, higher-order births are also contraindications for vaginal delivery.

Relative contraindications also exist for vaginal delivery. There are certain conditions where vaginal delivery can be tried. During labor, if the fetus presents in a brow situation, this may spontaneously convert to face or vertex presentations, which can then progress to vaginal delivery. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns, such as Category II and Category III fetal heart rate tracings that can signal fetal hypoxia or acidosis, may represent cord compression and entrapment can indicate avoidance of vaginal delivery. [17] Trial of Labor after Caesarean section (TOLAC) can also be attempted but is contraindicated when there is a history of multiple cesarean sections, history of placenta previa, and evidence of cephalopelvic disproportion as indicated by macrosomia. [18] Fetal weight greater than 5000 grams in a mother with diabetes or fetal weight greater than 4500 grams in a mother without diabetes are relative contraindications for vaginal delivery. [19]

Ensuring proper equipment is essential to a successful vaginal delivery and to minimize fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality. Appropriate equipment is necessary to anticipate and appropriately manage improbable but realistic complications of low-risk vaginal deliveries, as 20% to 25% of all perinatal morbidity and mortality occurs in pregnancies devoid of risk factors for adverse outcomes. [20]

Appropriate preparation includes a warm and clean room with adequate lighting and supplemental light source, a delivery bed with clean linen whose height can be adjusted, a plastic sheet to place under the mother, chlorhexidine, and wipes. There should be equipment for barrier protection such as gloves and masks. Sterile equipment includes appropriate sterile gloves, sterile instruments such as scissors, needle holders, artery forceps for cord clamping, dissecting forceps, sponge forceps, sterile blade, and cord ties. [21]

The list of equipment needed also includes a tocodynamometer to monitor uterine contractions using an external monitor or an intrauterine pressure catheter and fetal heart rate monitor with either external heart rate monitor or an internal fetal heart rate monitor (scalp electrode). If the delivery needs assistance, either forceps or vacuum can be kept bedside to assist in vaginal delivery. [22]

Analgesia can be kept bedside, but is not absolutely needed, as the use of oral or epidural analgesia is based on maternal preference.

For a normally anticipated vaginal delivery, a physician or a midwife with the aide of a nurse can appropriately and safely perform the procedure. Additional personnel are optional, however additional support and coaching from a formally trained doula, family member, and/or partner can enhance the experience for the mother and results in a decreased need for analgesia. [23] In addition, a pediatrician and an anesthesiologist should be available and on-call for any complications related to vaginal delivery.

- Preparation

As with any procedure, appropriate preparation and positioning of the patient are key to maximizing the success of the procedure while simultaneously minimizing morbidity and mortality. There are many factors to consider in preparing a patient for a vaginal delivery and the position of the patient changes based on the progression of labor through its various stages.

Patients should be adequately hydrated, as hypovolemia during labor can cause fetal heart tracing abnormalities. [24] Routine administration of antacids, routine enemas, and perineal shaving is not indicated. [25] [26] [27] [26] [25] Systemic antibiotics are indicated for a known positive Group B streptococcus (GBS) culture or unknown maternal GBS status. [28] There is no evidence in the literature supporting intrapartum chlorhexidine to prevent maternal or neonatal infections during vaginal delivery; conversely, this can lead to vaginal irritation and discomfort. [29] However, some institutions and providers routinely use povidone-iodine solutions, especially if there is intrapartum defecation during labor and delivery.

Once the patient is prepared for the delivery, it is important to ensure proper positioning for the vaginal delivery. For the first stage of labor, the patient should be connected to monitors to assess fetal and maternal vital signs, as well as maternal uterine contractions. Progression of labor can be assessed by regular pelvic exams to assess for cervical effacement and dilation; this examination can be done every three or four hours, or as needed. A Foley urinary catheter can be placed; however, it is not necessary. Current literature suggests that bladder distension does not affect labor progress. [30] During the first stage of labor, mothers are encouraged to ambulate and move around on the bed until a comfortable position is reached. Walking during the first stage of labor has no effect on the progress of and does not cause inhibition of normal labor. [31]

For the second stage of labor, it is important to chart fetal station and cervical dilation at each examination. Pushing with contractions should begin and be encouraged once the cervix has completely dilated. At the time, the birthing bed should be detached with the physician by the patient’s vagina. The patient is encouraged to be in a position that is most comfortable for her while pushing, but it is generally a lying position where the patient is supine lithotomy position.

Once the fetus is delivered, during the third stage of labor, optimally, the fetus is placed on the mother’s chest with the umbilical cord initially clamped then cut, while the mother continues to maintain the same position until the placenta is delivered. After the placenta is delivered and all equipment is cleared, the mother can lay supine and recumbent in a position she finds most comfortable.

- Technique or Treatment

Once maximal cervical dilation is reached and the patient experiences regular contractions every two to three minutes, she should be encouraged to push. The best way to push is bearing down, and the patient can be coached by asking the patient to push for at least ten seconds and for at least two or three times per contraction. [32] The patient should be encouraged to push towards the baby’s head, and can also be encouraged by asking the patient to minimize yelling while maximizing pushing.

While the patient continues to push, warm compresses can be applied, and the perineum can be massaged digitally with lubricant to soften and stretch the perineum. In women without a history of vaginal birth, perineal massage reduced the incidence of perineal trauma and the need for episiotomies but did not reduce the incidence of perineal trauma of any degree. [33] The second stage of labor can continue as long as needed as long as fetal heart rate tracing is normal, and progress is achieved, which can be quantified by progression in the fetal station. Once the fetus reaches +5 fetal station, which is crowning, the delivery of the fetus is imminent. At this time, the head of the fetus exerts dilatory pressure on the perineum, which leads to a tremendous urge for mothers to push, but appropriate steps of delivery should be followed in order to minimize perineal trauma.

Once the head crowns, a sterile towel or lap pad can be used to hold the fetal head; one hand should support the fetal head and maintain it in the flexion position while the other hand should be used to support the lower edge of the perineum by pinching it to avoid tearing or trauma. [34] During this time, the mother should be encouraged to stop pushing, and then use small contractions to enable the physician to control the pace of the fetal head delivery; precipitous delivery of the head can cause perineal trauma. Once the head is delivered, the mother should once again be asked to stop pushing, and the neck should be manually examined for the umbilical cord. If a nuchal cord is detected, it should be reduced [35] , and then the delivery of the rest of the fetus should continue.

Routine oropharyngeal care through suctioning is no longer supported by evidence as gently wiping mucus from the child’s face and nose is found to be equivalent. [36] Once the head is delivered, the next step is for delivery of the shoulders. With the next contraction, and using gentle downward traction towards the mother’s sacrum, the anterior shoulder is delivered as each side of the head is held. This maneuver allows the anterior shoulder to pass under the maternal pubic symphysis. While continuing to hold each side of the head, the posterior shoulder is delivered by applying gentle upward traction. It is important to apply the least amount of traction during the delivery of fetal shoulders to minimize the risk of traction-induced perineal injury and fetal brachial plexus injuries. [37] After the shoulders are delivered, care must be maintained as the rest of the delivery is spontaneous and requires minimal maternal effort, but it is important to guide the newborn child’s body as it passes the birth canal. Once the child is delivered, the umbilical cord should be clamped after a delay. In full-term vaginal deliveries, evidence supports that delayed cord clamping, which is defined as clamping of the cord after 30 seconds, prevents anemia in infants. The umbilical cord should be clamped using two clamps that are approximately three to four centimeters apart. The partner of the mother or the accompanying family member should be afforded the opportunity to cut the umbilical cord between the two clamps. Once the cord is cut, the newborn should be cleaned, and one-minute and five-minute APGAR scores should be evaluated. If the APGAR scores are within normal limits, the infant should immediately be transferred to the mother and placed on her bare chest. Early Skin-to-skin contact between the newborn infant and mother serves a multitude of functions. It has been shown to increase mother-infant bond and attachment, improve breastfeeding outcomes, and minimize infant head loss. [38] [39]

The third stage of labor is defined as the time from the delivery of the fetus until the delivery of the placenta. Active management at this time of delivery can reduce the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage and the need for blood transfusion. The active management of the third stage begins before the delivery of the placenta and includes uterotonic agent administration, application of gentle traction to umbilical cord after clamping it, and uterine massage. [40] The preferred uterotonic agent is oxytocin, which is administered immediately after the delivery of the fetus. Signs of placental separation from the uterus, such as a gush of blood, should be observed as the uterus contracts. Cord traction facilitates the separation of the placenta and enables its delivery. One method of cord traction application is known as the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, in which one hand secures the uterine fundus on the abdomen to prevent uterine inversion while the other hand exerts sustained downward gentle traction of the clamp on the umbilical cord. This maneuver leads to a reduction in the need for manual placental removal; in addition, there is a statistically significant reduction in the duration of the third stage of labor, blood loss, and incidence of postpartum hemorrhage. Once the placenta is delivered, it should be thoroughly inspected on the outside and by inverting it to check for missing pieces, because retained products of conception are a known risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage.

After the placenta is delivered, the vaginal canal should be inspected for any lacerations, and if lacerations are detected, they should be repaired.

- Complications

There are numerous complications associated with vaginal delivery; these complications vary by stages of labor and are dependent on numerous factors. In general, complications can be generalized into the following categories: failure to progress, abnormal fetal heart rate tracing, intrapartum hemorrhage, and post-partum hemorrhage.

Failure to progress can happen in either the first stage or the second stage. Failure to progress in the first stage of labor can be either protraction of active phase of labor, which is defined as cervical dilation rate less than one to two centimeters per hour in women who’s cervix is at least six centimeters dilated. [41] The arrest of the first stage of labor is defined as no change in cervical dilation for more than four hours in a woman with adequate uterine contraction strength (defined as 200 Montevideo units or greater) or no change in cervical dilation in a woman for more than six hours with inadequate contraction strength. Protracted labor can be managed by augmenting labor with oxytocin, which is a uterotonic agent. [42] Women with arrested labor are managed by conversion of vaginal delivery to a cesarean section mode of delivery. [43]

Failure to progress during the second stage of labor is diagnosed when there is minimal descent of the fetus in nulliparous women who have pushed for a minimum of three hours and multiparous women who have pushed for a minimum of two hours; women with epidural anesthesia are allowed slightly longer durations for pushing. [44] Failure to progress during the second stage of labor due to inadequate contractions or minimal descent of the fetus can be managed by the administration of oxytocin to augment labor after 60-90 minutes of pushing. If this does not help, an operative vaginal delivery using a vacuum or forceps or a cesarean section should be considered.

Failure to progress can also be due to abnormal passage of descent for the fetus, which is directly related to cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD). CPD can be related to fetal malposition or macrosomia and is a subjective diagnosis which requires conversion of the delivery to a cesarean section. CPD is most commonly observed during the second stage of labor. [45]

During a vaginal delivery, the fetal heart rate must be monitored, and decelerations during labor, whether early decelerations or late decelerations, can indicate head compression of the fetus, cord compression of the fetus, hypoxemia, and even anemia of the fetus. If an abnormal fetal heart rate persists, resolution can be attempted by removing labor augmenting agents such as oxytocin or repositioning the mother on the left lateral side. [46] If these maneuvers do not lead to the resolution of the abnormal fetal heart rate, an emergent cesarean section is indicated.

Vaginal delivery can be complicated by intrapartum hemorrhage. During a normal vaginal delivery, some blood from the effacement of the cervix or minor trauma of the vaginal canal can mix with amniotic fluid and can present as a serosanguineous appearance. However, the presence of frank blood is abnormal and can either be due to placental abruption, uterine rupture, placenta accrete, undiagnosed placenta previa, or vasa previa. These conditions are true obstetric emergencies and require an emergent cesarean section. [47]

Finally, vaginal deliveries can be complicated by postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). PPH can be due to atony of the uterus, trauma to the birth canal, retained products of conception or due to a coagulopathy; uterine atony is the most common cause of PPH. [7]

- Clinical Significance

Proper preparation, monitoring, and technique during vaginal delivery are important to minimize morbidity and mortality to both the mother and the fetus. According to the latest data on births in the United States, [4] The incidence of cesarean delivery increased from 2016 to 2017, which is the first increase since 2017. While cesarean section deliveries are absolutely necessary for certain peripartum conditions, cesarean section deliveries have been shown to increase the long-term risk of small bowel obstruction in women. [48]

Additionally, cesarean sections correlate with an increased risk of uterine rupture, abnormal placentation for future pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies, preterm births, and stillbirth. Evidence suggests cesarean section deliveries lead to differing and altered physiology in neonates due to exposure to differing hormonal, physical, microbiological, and medical exposures, which can affect short-term and long-term development. Short-term risks to babies include alteration in the immune system, increased likelihood in developments of allergies, asthma, and reduced intestinal microbiome, while long-term risks include the development of obesity and risks associated with obesity.

Conversely, advantages of a successful vaginal delivery are numerous to both the baby and the mother. With a vaginal delivery, there is a higher chance of being able to breastfeed successfully shortly after delivery, decreased hospital stay after childbirth, rapid recovery physically and psychologically, and increased mother-child bond and attachment. For the baby, the benefits of vaginal delivery include improved hormonal and endocrinological functions such as blood sugar regulation, respiratory function, temperature regulation, and an increase in exploratory behaviors. Other benefits include better long-term growth, immunity, and development compared to children born as a result of a cesarean section. [49]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Vaginal delivery is a major and ubiquitous procedure that can be associated with serious morbidities and potential mortality to the mother and the neonate due to a number of intrapartum and postpartum complications related to the procedure. Maternal complications include, but are not limited to, placental abruption, uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage, endometritis, amniotic fluid embolism, and neonatal complications include sepsis, meningitis, shoulder dystocia, and brachial plexus injuries. Responsibilities of the healthcare team include minimizing these complications via proactive management of the patient during vaginal delivery.

While some women opt for home births, pregnant women are unable to confirm the rupture of membranes, check for cervical dilation or effacement, and the healthcare team's goal is to ensure safe progression through labor and to lead to the successful delivery of the baby. Nurses and midwives are needed to help the patient get ready and motivate her through labor, and even facilitate the delivery of the baby, physicians are responsible for monitoring the fetal and maternal well-being while being cognizant of possible complications and treating those.

A collaborative effort between the patient, her support system, the nurses, technicians, and physicians is required for successful vaginal delivery to minimize morbidity and mortality.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Forceps delivery Image courtesy S Bhimji MD

Disclosure: Ninad Desai declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Alexander Tsukerman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Desai NM, Tsukerman A. Vaginal Delivery. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Severe maternal and neonatal morbidity after attempted operative vaginal delivery. [Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021] Severe maternal and neonatal morbidity after attempted operative vaginal delivery. Panelli DM, Leonard SA, Joudi N, Girsen AI, Judy AE, El-Sayed YY, Gilbert WM, Lyell DJ. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021 May; 3(3):100339. Epub 2021 Feb 23.

- Review Cesarean section on request at 39 weeks: impact on shoulder dystocia, fetal trauma, neonatal encephalopathy, and intrauterine fetal demise. [Semin Perinatol. 2006] Review Cesarean section on request at 39 weeks: impact on shoulder dystocia, fetal trauma, neonatal encephalopathy, and intrauterine fetal demise. Hankins GD, Clark SM, Munn MB. Semin Perinatol. 2006 Oct; 30(5):276-87.

- The impact of manual rotation of the occiput posterior position on spontaneous vaginal delivery rate: study protocol for a randomized clinical trial (RMOS). [Trials. 2018] The impact of manual rotation of the occiput posterior position on spontaneous vaginal delivery rate: study protocol for a randomized clinical trial (RMOS). Verhaeghe C, Parot-Schinkel E, Bouet PE, Madzou S, Biquard F, Gillard P, Descamps P, Legendre G. Trials. 2018 Feb 14; 19(1):109. Epub 2018 Feb 14.

- Maternal and newborn outcomes with elective induction of labor at term. [Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019] Maternal and newborn outcomes with elective induction of labor at term. Souter V, Painter I, Sitcov K, Caughey AB. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Mar; 220(3):273.e1-273.e11. Epub 2019 Feb 17.

- Review Delivery for women with a previous cesarean: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). [Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Bi...] Review Delivery for women with a previous cesarean: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Sentilhes L, Vayssière C, Beucher G, Deneux-Tharaux C, Deruelle P, Diemunsch P, Gallot D, Haumonté JB, Heimann S, Kayem G, et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013 Sep; 170(1):25-32. Epub 2013 Jun 28.

Recent Activity

- Vaginal Delivery - StatPearls Vaginal Delivery - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

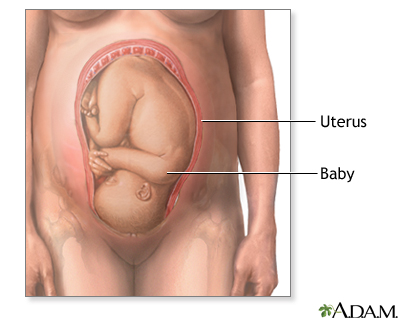

Breech - series—Normal position of the baby

- Go to slide 1 out of 7

- Go to slide 2 out of 7

- Go to slide 3 out of 7

- Go to slide 4 out of 7

- Go to slide 5 out of 7

- Go to slide 6 out of 7

- Go to slide 7 out of 7

The term "fetal presentation" refers to the part of your baby's body that is closest to the birth canal. In most full-term pregnancies, the baby is positioned head down, or cephalic, in the uterus.

Review Date 11/21/2022

Updated by: LaQuita Martinez, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Emory Johns Creek Hospital, Alpharetta, GA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Related MedlinePlus Health Topics

- Childbirth Problems

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 10: Normal Mechanisms of Labor

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Left occiput anterior: loa.

- BIRTH OF THE PLACENTA

- CLINICAL COURSE OF LABOR: LOA

- RIGHT OCCIPUT ANTERIOR: ROA

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

LOA is a common longitudinal cephalic presentation ( Fig. 10-1 ). Two-thirds of occiput anterior positions are in the LOA position. The attitude is flexion, the presenting part is the posterior part of the vertex and the posterior fontanelle, and the denominator is the occiput (O).

FIGURE 10-1.

Left occiput anterior.

Diagnosis of Position: LOA

Abdominal examination.

The lie is longitudinal. The long axis of the fetus is parallel to the long axis of the mother

The head is at or in the pelvis

The back is on the left and anterior and is palpated easily except in obese women