- Departments

- For Students

- For Faculty

- Book Appointment

- Flow and Cohesion

- Reverse Outline

Paper Skeleton

- Creating a Research Space

- Personal Statements

- Literature Reviews

What Is a Skeleton?

A skeleton is the assemblage of a given paper’s first and last sentences of each paragraph.

Why Should I Use a Skeleton?

A skeleton can be used to address a bunch of different elements of a paper: precision of topic and concluding sentences, transitions, arrangement, repetition -- you name it. Mostly, it forces us to think of these sentences as joints to a skeleton, or moves being made in papers, and whether those moves are effective and accurate.

How Do I Perform a Skeleton?

First, copy and paste (or copy if working with a paper draft) the first and last sentences of each paragraph into a different document. Then, read them in the order they’re written and consider the moves these sentences are trying to make.

Example (the Following Skeleton Represents About One-Third of a Complete Draft):

P1: Topic: Jean Rhys' Good Morning, Midnight confines the reader to Sasha's declining mental state for the whole of the novel, robbing them of varied perspectives and enveloping them in her traumatic isolation. Conclusion: In doing so, Sasha creates a world within the world, one that exists behind the curtain of her mind, to remove herself from the pain of the present. P2: T: Terrance Hawkes argues that it is human nature to create worlds – stories, myths, and the like – to deal with the immediate world creatively, rather than directly. C: Deep within this well, Sasha finds herself mute during moments where she might defend herself, or dignify her actions. P3: T: Ewa Ziarek's writing in Female Bodies, Violence, and Form, help inform Sasha's silence as having resulted from (and be Rhys' response to) sexism and the abasement of females during the time of publication. C: However, Sasha's outward silence that is ventilated in her mind reveals a great deal about the nature of her isolation and her means of maintaining it. P4: T; Sasha's most telling method of isolation is what Ziarek refers to as 'petrified female tongue' (174), a silence that arises when a voice is needed most. C*: This is the present the novel takes place in. P5: T: Stuck in the now but desperately escaping to the safe place inside her head (which proves not much better), Sasha often reflects on the past to anesthetize the pain of the present. C: Sasha doesn't feel a connection with men like Mr. Blank but rather perceives herself as a damaged commodity, albeit one with a small measure of dignity *You’ll notice that this structure can and probably should be changed. Often we open and conclude in 1-2 sentences, and so paragraph 4’s last sentence is actually only half of the conclusion.

To What End?

Many observations may be made from the above skeleton, given a reading of the entire paper. Since it’s an old paper of my own, I see now that front-loading Hawkes and Ziarek into the paper might not be the most effective use of those readings. Moreover, I can see now the transition between such readings (P2C and P3T) is pretty loose.

[ Activity written by Luke Useted, May 2015. Image by Flickr user, Shaun Dunmall and used under Creative Commons license]

The Skeletal System Essay

Introduction, axial portion of the skeleton, appendicular portion of the skeleton, functions of the skeleton, relationship between the skeletal system and the muscular system, sexual differences in skeletons, clinical conditions and disorders that affect the skeleton, works cited.

Movement is vital for all of you because it provides you with the opportunity to live your lives to the full. Just as other human beings, you fall and stand up to continue moving forward. But what provides you with this opportunity? It is your skeletal system. It does not only facilitate your physical activity but also supports and protects your bodies. This system consists of hundreds of bones that are full of calcium, which makes them strong enough to carry your weight. Bones are connected with the help of joints that facilitate motion. The majority of you were born with about 300 bones that fuse with the course of time so that now you have only 206 bones. They all are divided into two parts: axial and appendicular skeletons.

Your axial portion of skeleton is composed of “the skull, the vertebral column, and the thoracic cage” ( Skeletal System: Bones and Joints 120). Due to its location, it manages to protect your brain and spinal cord from injuries. In addition to that, it supports the organs in the ventral body cavity so that you do not need to carry them in your hands.

Twenty-two bones that are separated into two parts form the skull. You have 8 bones of the cranial cavity that are known as braincase. They surround your brain so that you do not hurt it when fall or receive a headnut. The rest of the bones (there are 14 of them) form your face. They are tightly connected to one another so that your nose is always in the right place. The only exception is the mandible that makes chewing possible. Otherwise, how would you eat? Minimal movement can also be observed within the middle ears. Each of them includes 3 auditory ossicles that are hidden deep in your head.

The vertebral column, or backbone, usually consists of “7 cervical vertebrae, 12 thoracic vertebrae, 5 lumbar vertebrae, 1 sacral bone, and 1 coccyx bone” ( Skeletal System: Bones and Joints 125). It is the central axis of the skeleton that has four major curvatures. Normally, the cervical and the lumbar regions curve anteriorly. The thoracic, as well as the sacral and coccygeal regions, curves posteriorly. However, considering the way you sit, abnormal curvatures are widespread.

The thoracic or the rib cage protects your organs and supports them. All in all, human beings have 24 ribs that are divided into 12 pairs, but you can recount them to make sure. They are categorized according to their attachment to the sternum. Thus, a direct attachment by costal cartilages is true (1-7); an attachment by a common cartilage is false (8-12); and the absence of attachment resorts to floating ribs (11-12). The sternum, or breastbone, consists of three parts: “the manubrium, the body, and the xiphoid process” ( Skeletal System: Bones and Joints 129).

Your appendicular skeleton consists of the bones of limbs and girdles so that you have:

- “4 bones in the shoulder girdle (clavicle and scapula each side).

- 6 bones in the arm and forearm (humerus, ulna, and radius).

- 58 bones in the hands (carpals 16, metacarpals 10, phalanges 28, and sesamoid 4).

- 2 pelvis bones.

- 8 bones in the legs (femur, tibia, patella, and fibula).

- 56 bones in the feet (tarsals, metatarsals, phalanges, and sesamoid)” (“The Axial & Appendicular Skeleton” par. 4).

What would you be without this part of skeleton? Imagine that it is a big 3D puzzle, gathering all these bones together in a right order, you will build your arms and legs with all details. These are all movable parts that allow you to run, dance, write, and even hug your nearest and dearest. Even though the axial skeleton seems to be more important because it is connected with your brain, the appendicular portion of the skeleton contains about 60% of all your bones, which means that its importance should not be undervalued.

As you have already understood, your skeleton maintains a lot of different functions. Some of them, such as movement and support, were already mentioned. But let us discuss them all in detail.

- Support. Your bodies are supported by the skeleton so that you can change your position to vertical one and stand strait. Without it, you would be able only to lie because of the gravitation. This function is provided by many bones but the long ones seem to be the leaders in this competition. For instance, those that are in legs, support the trunk. Similarly, vertebras support one another so that eventually the firs one provides support to the skull. In addition to that, they support the organs and ensure that they do not change their positions.

- Protection. The skeleton also protects you. For example, the skull prevents fatal brain injuries. The rib cage protects such vital organs as the heart and lungs. It also takes care of your abdominal organs ensuring that they develop normally.

- Movement. The function of bodily motion allowed you to come here today. However, it is critical to remember that it is maintained not only due to the bones but also with the help of the muscular system.

- Mineral and energy storage. From the outer side of your bones, there is a tissue that serves as a storage. It gathers calcium and phosphorus and withdraws them to maintain appropriate blood levels. In addition to that, mature bones store yellow marrow. It consists of fat almost totally and provides you with energy for various activities.

- Blood-cell formation. The inner core of your bones takes part in the formation of blood cell and platelet. It is known as bone marrow or red marrow. Platelet is vital for you because it ensures your ability to heal wounds while blood cells spread oxygen and destroy infectious cells (CAERT 3).

Have you ever thought of the way our movement are maintained? Even a simple nod of the head requires the cooperation between the skeletal and muscular systems. Muscles ensure movement of our body through the attachment to the bones. All in all, there are about 700 of them, which is an enormous amount that comprises about 50% of your weight.

So what happens in your body when you moves? When you want to move, your brain sends a message for the body to release energy. In medical terms, it is called adenosine triphosphate. Affecting your muscles, it makes them contract or shorten. Shortened muscles pulls bones at their insertion point. Thus, the angle between the bones connected by a joint shortens. Relaxation is maintained when the opposing muscle extends and pulls a bone to its initial position.

Human skeletons seem to be similar, as they contain the same bones. However, you should remember that their characteristics differ depending on the gender. For example, women have lighter pelvis bones that form a shorter cavity with less dimensions. It has less prominent marking for muscles and more circular pelvic brim. The sacral bones of men are longer and narrower, which makes them more massive. Their femur is also longer and heavier. Its texture is rough unlike women’s smooth.

Muscle marking is more developed and shaft is less oblique. The head of men’s femur is larger and trochanters are more prominent. The femoral neck angle in males is more than 125 and in females is less than 125. Women’s sternum is less than twice the length of manubrium and larger in men. Differences in skull include greater capacity, thicker walls, more marked muscular ridges, prominent air sinuses, smoother upper margin of orbit, less vertical forehead, and heavier cheekbones in males.

Hopefully, it will never affect any of you but the skeleton may be affected by tumours that cause bone defects. People may have skeletal developmental disorders including gigantism, dwarfism, osteogenesis imperfecta, and rickets lead to abnormal body sizes, brittle bones, and growth retardation. Bacterial infections cause inflammation and lead to bone destruction.

Decalcification, including the known to you osteoporosis, reduces bone tissue and softens bones. Joint disorders often deal with inflammation. For instance, arthritis. They are often influenced by age and physical activity. In this way, degradation of joints is observed in the elderly but can be delayed due to regular exercises. The abnormal curvatures of the spine may also cause health issues. That is why you should pay attention to your back posture and avoid kyphosis (a hunchback condition), lordosis (a swayback condition), and scoliosis (an abnormal lateral curvature).

CAERT. Structures and Functions of the Skeletal System . 2014. Web.

Skeletal System: Bones and Joints. 2012. Web.

“ The Axial & Appendicular Skeleton. ” TeachPE , 2017. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 13). The Skeletal System. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-skeletal-system/

"The Skeletal System." IvyPanda , 13 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/the-skeletal-system/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'The Skeletal System'. 13 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "The Skeletal System." December 13, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-skeletal-system/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Skeletal System." December 13, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-skeletal-system/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Skeletal System." December 13, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-skeletal-system/.

- The Evolution of Vertebrae Teeth

- Human Skeleton Sexes: Anthropological Perspectives

- Aspects of Radiology Assignment

- Patient with Hodgkin's Lymphoma

- Cervical, Thoracic, and Lumbosacral Spinal Cord Cross-Section Levels

- Respiratory Care of Thoracic Injuries

- Archaeoosteology: Osteological Analysis Methods

- Articular and Muscular Systems

- The Muscular System of a Human Body

- Aspects of the Skeletal System

- Neuropsychological Tests Reliability Following Concussion

- Physicians, Their Roles and Responsibilities

- Prevalence of Sleep Disorders among Medical Students

- Human Physical Performance Under Adverse Conditions

- Tongue and Why It Is Unique

How to use a skeleton outline in writing. Including my personal method & template

- Post author By Vasyl Kafidov

- Post date October 12, 2020

- Categories In tips , writing

- 3 Comments on How to use a skeleton outline in writing. Including my personal method & template

Content writing is a creative process, first of all. But it doesn’t mean that it cannot benefit from a little structure and systematic approach. I feel like a lot of bloggers underestimate the benefits of skeleton outlines in their everyday work.

Why? Well, it is hard to say for everyone, but I think a lot of them do not like skeleton outline writing since their college years.

Working on an outline might seem too academic and boring at first sight. But, it is still an excellent way to write faster, more efficiently, and provide better content for readers.

If you want to know how to implement a skeletal outline in your blogging, let’s start with the basics.

What is a skeleton outline?

To put it simply, a skeleton outline is a breakdown of the future post. It is a lot like a plan of what you are going to write with a specific structure.

A great example of a skeleton outline is a table of content of any academic publication or non-fiction book. The table of content, in this case, is very particular and describes what each part of the text is about.

An outline helps a writer to achieve several goals, starting with breaking down the big task into smaller parts. I always create a skeleton blog outline before writing a post or article because it helps me to be a better writer.

And the best part is that it can be used for any writing type, whether it is an article, press release, essay, or blog post. The difference lies only in the structure of each of them.

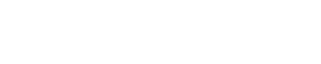

In their blog posts that cover the same topic as you are reading now, Coschedule has created a blog post outline template . You will find an outline or, as it is also called, a skeleton or skeletal outline on the picture below.

I do not want to repeat others or tell you only some theoretical information about how important an outline can be when we talk about crafting a blog post after you have already come up with a topic idea and will move forward to my personal thoughts and experience.

For me, a blog outline serves as a guide on what I’m going to cover and in what order. It is also a perfect way to get rid of writer’s block and fear of a blank page. Like with a blog content writing plan , with a skeletal outline, you’ll never have to stare at the blank screen, thinking about what to write next because you have a plan.

Why skeleton outlines are important?

There are several quite crucial benefits of starting with an outline.

- It helps to write faster. When you have a plan, you know exactly what research you need to do and what type of information to look for. It works as a compass. It also helps to figure out the lengths, breakdown, and general idea of the piece. And you can work from section to section, not necessarily in the correct order.

- An outline adds up a logical structure. Logical flow is extremely valuable for good writing. And readers appreciate it, as it is much easier to follow something consequential. An outline gives perspective and helps to reorganize your ideas in the most powerful way.

- It helps to break down a task into smaller steps. It helps to stay motivated and inspired. Huge tasks are stressful and it is much easier to work on one part at a time.

- A skeleton outline makes your writing efficient. The more you use it, the easier and faster it gets to create a skeleton outline. Texts always follow approximately the same structure. In a couple of times, you’ll know exactly where to start.

- It helps to build stronger argumentation. Always start with the strongest points and deliver them one by one.

My method of using skeleton outlines for blogging

Now, let’s get to practice. I’ll guide you through my process of creating a skeleton outline with the example of my blog post on humor.

Start with a title. Titles are important, every writer knows that. Ensure that it is specific, works for your blog, includes keywords, and is not too long.

In my case, the title is “Usage of humor for your business. Funny but serious”. It is catchy, SEO-friendly, and shows the reader what the subject of the post is.

After reading the article, you can look at the final “ Usage of humor for your business. Funny but serious ” article that was written using the method I’m showing in the article.

Research the subject and analyze what is extensively covered and what is missed. Consider what points you want to address based on your experience and knowledge.

Your personal experience is king , do not be afraid to mention several points from your personal stories or your friends’ experience in your initial blog outline draft. That WILL BE useful, believe me, even if you’ll decide to remove some of them in your final skeleton.

Write down the main points of the article. It is time to brainstorm ideas. Write them down without particular order. Think about what you want to cover and what takeaways will be there for the audience. Put them one by one.

For example, my ideas for the post were:

- Why the humor is used in marketing;

- How often do businesses use humor;

- What are the benefits;

- What are the risks;

- Which techniques can a blogger use to create humorous content;

- Can a brand be serious while using humor in a marketing campaign;

- Importance of humor in communication and everyday life

- Examples of successful use of humor in business;

- Examples of fails;

- Types of humor techniques;

- Practical advice on how to be funnier in your writing.

Combine them into larger sections. Now it is time to rearrange them in a logical order and in large groups. Some of the ideas are smaller; others are going to take a full section.

Define the bigger and most important points and add smaller aspects to them. Hubspot has clearly explained how to make larger outline sections in detail, so do not hesitate to have a look. Ready to get a sample of the skeleton outline?

My personal blog outline template:

- Importance of humor in communication and everyday life;

- Why it is used in marketing

- Statistics;

- List of benefits;

- Risks of Incorporating Humorous Strategy in Business;

- Usage of humor in your business blog and How to Do it;

- General tips on the usage of humor;

- Techniques to Make Your Blog Funnier;

- Example of successful usage;

- Examples of fails;

- Can a brand be serious while using humor in a marketing campaign?

- Summary

Go through the outline and make changes. Maybe replace some points or add marks like “find statistic data” or “link to research”.

If there is no urgency, I would also suggest you leave the outline for a blog post for one day. Take a nap or spend your time with friends and then recheck your outline with fresh thoughts. This will help you to gain some new ideas before you have started writing.

Include the links to the sources you are going to use for each section. It will surely help you once you’ll start drafting your blog post. You can also add keywords to the subtitles.

In my opinion, it will help you from the beginning, but sometimes it doesn’t make sense because of the high chances that you’ll rewrite headings and subheadings during the writing process. Therefore, this trick is up to you 😉

Okay, let’s go! Now you are ready to start writing, following your astonishing outline skeleton.

Skeleton outline is extremely helpful in any type of writing. Even when you make a writing sample , you can use an outline before writing the final draft.

It organizes thoughts and ideas, helps to write faster, and creates a logical flow.

At the same time, it helps to overcome writer’s block as you always have a plan on what to cover next.

If you have some personal methods that might be useful for my readers, kindly share them in the comments. I’ll be glad to find some new and unusual ways.

Vasyl Kafidoff is a founder and mastermind of KAFIDOFF.COM . He has a strong interest in education, modern technology, marketing, and business management. If Vasy is not working, you can find him somewhere in the world attending a Rock Concert with his mates.

- Scouting Talent: My Two Cents on Where to Find Stellar Blog Writers! July 26, 2023 Unravel the mystery of finding the perfect blog writer for your needs with our comprehensive guide. Explore top platforms for hiring freelance writers and learn from the pros about their best practices. Plus, gain insight into the world of blog writing, costs, and why you might consider hiring a professional team.

- Where To Find Free Images For Your Blog: 10 Best Websites April 14, 2023 Are you searching for ways to add visually-appealing images to your blog without breaking the bank on expensive stock photos? Our article offers a detailed list of websites where you can find top-quality images for free, as well as valuable advice on how to select and incorporate them into your blog content. Whether you need striking nature photos or authentic human portraits, we’ve got you covered. Start crafting captivating blog posts today!

- Content is King, But Editing is the Crown: Why Marketers Need Copy Editors? March 13, 2023 In the fast-paced world of marketing, producing high-quality content quickly is a must. But in the rush to get content out the door, mistakes can happen. That’s where copy editors come in. By reviewing and revising content, they ensure that it is accurate, engaging, and on-brand. In this article, we explore why copy editors are essential for marketers, and how they can help improve the quality and effectiveness of your written content.

- From Generalist to Expert: The Advantages of Writing in a Specific Niche February 13, 2023 Are you thinking about focusing your writing in a specific niche? Good news – writing in a specific niche can be super beneficial for several reasons. From becoming an expert in a particular subject to attracting a loyal reader base and opening up new opportunities, writing in a specific niche has many benefits. Plus, it can just be more fun that way.

- 50+ Most Profitable Blogging Niches With Low Competition in 2023 January 16, 2023 Everybody who’s willing to make money blogging wants to know what are the most profitable blogging niches with low completion in the year 2023. Soooooo…let’s figure it out.

- Tags blog , blogging , tips , writers , writing

Teaching Analytical Writing: Essay Skeletons

Posted March 17, 2015 by laurielmorrison & filed under Series on teaching students to write essays , Teaching .

Hi there! I’m back with the third installment of my series on teaching analytical writing. Last time, I explained the TIQA paragraph , which I see as the building block of an analytical essay, and described how I give students a lot of practice writing analytical paragraphs before moving onto essays.

When it’s time to move onto analytical essays, I lay the groundwork in a couple of ways. First, I tell students about the essay topics I plan to give them as we are reading the book they will be writing about. We look out for quotes that relate to those topics together, and I encourage them to look out for additional quotes on their own. That way they’re not starting from scratch when it comes time to find quotes for their essays.

Once we’ve finished the book, I have students choose an essay topic. I can provide scaffolding for students who need it by steering them toward one of the topics we found quotes for during class, while I can encourage other students to branch out to topics we haven’t spent much class time exploring or even to come up with topics on their own.

Next, each student creates an essay skeleton . The essay skeleton includes their thesis statement , their topic sentences , and the quotes they will use in their body paragraphs. (For eighth grade I require that at least one of the body paragraphs includes a second quote and follows the TIQATIQA format. For seventh graders I don’t require a double TIQA paragraph, but some students choose to write them.)

The essay skeleton provides the core of the essay that students will be writing. It isn’t too difficult for me to give prompt feedback to each student on a thesis statement, topic sentences, and quotes, and I find that it’s worth it to look at these elements of their essays before they move forward with drafting. The bottom line is, it’s impossible to write a successful essay without a decent thesis or with quotes that don’t match up with the thesis.

So how do you teach students to write a good thesis statement ? Here is my explanation of thesis statements , adapted from a handout I made for seventh graders writing essays about Howard Fast’s novel April Morning. If students are struggling to grasp thesis statements, it can work well to create some faulty thesis statements, model the process of fixing one, and then have students work together to fix another.

Interested in tips for explaining topic sentences ? Here’s my explanation of topic sentences , using the same example thesis from the April Morning thesis resource. It can work well to have the class practice breaking down a model thesis into effective topic sentences before students try to write their own.

Once students have their essay skeletons, they draft their body paragraphs, using the TIQA format, and then after that, we move on to introductions and conclusions. Next time I’ll explain my reasoning for leaving the introduction and conclusion until the end, and I’ll share handouts I use for those two parts of the essay.

7 Responses to “Teaching Analytical Writing: Essay Skeletons”

Wow. That’s excellent, Laurie. Have your students given you any feedback on ways the essay skeleton (great idea) or the TIQATIQA format in general helped them formulate their arguments? This is such a good way to help them to not be afraid of analytical writing.

Thanks so much! Most of them prefer creative writing assignments regardless of my attempts to make analytical writing accessible. 🙂 But several of them have mentioned that essays feel more manageable in chunks, and they definitely have some satisfying aha moments when they get what makes a good thesis and how to analyze a quote well. I’ve heard from a few of them who continue to start by coming up with the thesis, quotes, and topic sentences once they get to high school because they find the process helpful, and that makes me feel like it’s working pretty well.

Good. They’ll be ready for the research papers they will have to write!

Laurie, I love the way you’re teaching this to your students. Not an easy task at all. You sound like such a wonderful teacher!

Thanks so much, Sharon! I know you know a lot about teaching, so I especially appreciate that comment coming from you!

- Author Interviews

- Author Visits

- Book Reviews

- Coming Up Short

- Every Shiny Thing

- Middle Grade at Heart

- Middle Grade Literature

- My Reading Highlights

- Posts about author visits and Skypes

- Posts about pedagogy

- Posts with specific prompts or suggestions for specific assignments, units, and books

- Resources for Writers

- Series on teaching students to write essays

- sporty middle grade

- Student-Author Interview Series

- The Writing Process

- upper middle grade

- Writing with an eye toward the market and your intended audience

- Young Adult Literature

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.3.3: Body – the Skeleton of Your Paper, Using Paragraphs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 74447

Using Paragraphs

Read this article, which will help you understand how to organize paragraphs in the body of your essay to help make your paragraphs cohesive and to smoothly transition between one discussion point to the next. Keep in mind that the paragraphs in the body of your essay should work to prove or address your main purpose or argument set out by your thesis statement.

Understand how to organize information in paragraphs so readers can scan your work and better follow your reasoning.

Unlike punctuation, which can be subjected to specific rules, no ironclad guidelines exist for shaping paragraphs. If you presented a text without paragraphs to a dozen writing instructors and asked them to break the document into logical sections, chances are that you would receive different opinions about the best places to break the paragraph.

In part, where paragraphs should be placed is a stylistic choice. Some writers prefer longer paragraphs that compare and contrast several related ideas, whereas others opt for a more linear structure, delineating each subject on a one-point-per-paragraph basis. Newspaper articles or documents published on the Internet tend to have short paragraphs, even one-sentence paragraphs.

If your readers have suggested that you take a hard look at how you organize your ideas, or if you are unsure about when you should begin a paragraph or how you should organize final drafts, then you can benefit by reviewing paragraph structure. The following guidelines can give you some insights about alternative ways to shape paragraphs.

Note: When you are drafting, you need to trust your intuition about where to place paragraphs; you don't want to interrupt the flow of your thoughts as you write to check on whether you are placing them in logical order. Such self-criticism could interfere with creativity or the generation of ideas. Before you submit a document for a grade, however, you should examine the structure of your paragraphs.

Paragraph Transitions

Effective paragraph transitions signal to readers how two consecutive paragraphs relate to each other. The transition signals the relationship between the "new information" and the "old information".

For example, the new paragraph might:

- Elaborate on the idea presented in the preceding paragraph;

- Introduce a related idea;

- Continue a chronological narrative;

- Describe a problem with the idea presented in the preceding paragraph;

- Describe an exception to the idea presented in the preceding paragraph;

- Describe a consequence or implication of the idea presented in the preceding paragraph.

Let's consider a few examples (drawn from published books and articles) of paragraph transitions that work. The examples below reproduce paragraph endings and openings. Pay attention to how each paragraph opening signals to readers how the paragraph relates to the one they have just finished reading. Observe the loss in clarity when transitional signals are removed.

The transitional sentence signals that the new paragraph will seek to demonstrate that the phenomenon described in the preceding paragraph (Taylorism) is ongoing: it is "still" with us and "remains" the dominant workplace ethic. Compare this sentence with the one directly beneath it ("paragraph opening without transitional cues"). With this version, readers are left on their own to infer the connection.

The transitional sentence signals that the new paragraph will provide another example of the phenomenon (changed mental habits) described in the preceding paragraph. In this example, the word also serves an important function. Notice that without this transitional cue the relationship between the two paragraphs becomes less clear.

The transitional sentence signals that the new paragraph will challenge the assumption described in the preceding paragraph. The single transitional term "but" signals this relationship. Notice the drop-off in clarity when the transitional term is omitted.

The transitional sentence signals that the new paragraph will further explore the idea expressed in the preceding paragraph. The phrase "makes a similar point" signals this relationship. Without this transitional phrase, the connection between the two paragraphs can still be inferred, but it is now much less clear.

As the above examples illustrate, effective paragraph transitions signal relationships between paragraphs.

Below are some terms that are often helpful for signaling relationships among ideas.

The examples of transitional sentences are from:

- Parker, Ian. "Absolute Powerpoint". New Yorker. 28 May 2001: 76-87.

- Carr, Nicholas. "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" Atlantic Monthly. Jul/Aug2008: 56-63.

- Harrington, John. The Rhetoric of Film. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973.

- Spurr, David. The Rhetoric of Empire. Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press, 1993.

Paragraphs Often Follow Deductive Organization

Your goals for the opening sentences of your paragraphs are similar to your goals for writing an introduction to a document. In the beginning of a paragraph, clarify the purpose. Most paragraphs in academic and technical discourse move deductively--that is, the first or second sentence presents the topic or theme of the paragraph and the subsequent sentences illustrate and explicate this theme. Notice, in particular, how Chris Goodrich cues readers to the purpose of his paragraph (and article) in the first sentence of his essay "Crossover Dreams":

Norman Cantor, New York University history professor and author, most recently, of Inventing the Middle Ages, created a stir this spring when he wrote a letter to the newsletter of the American Historical Association declaring that "no historian who can write English prose should publish more than two books with a university press – one for tenure, and one for full professor after that (or preferably long before) work only in the trade market". Cantor urged his fellow scholars to seek literary agents to represent any work with crossover potential. And he did not stop there: As if to be sure of offending the entire academic community, Cantor added, "If you are already a full professor, your agent should be much more important to you than the department chair or the dean".

Paragraphs Use Inductive Structure for Dramatic Conclusions or Varied Style

While you generally want to move from the known to the new, from the thesis to its illustration or restriction, you sometimes want to violate this pattern. Educated readers in particular can be bored by texts that always present information in the same way.

For example, how Valerie Steele's anecdotal tone and dialogue in the opening sentences of her essay on fashion in academia prepare the reader for her thesis:

Once, when I was a graduate student at Yale, a history professor asked me about my dissertation. "I'm writing about fashion", I said.

"That's interesting. Italian or German?"

It took me a couple of minutes, as thoughts of Armani flashed through my mind, but finally, I realized what he meant. "Not fascism", I said. "Fashion. As in Paris."

"Oh." There was a long silence, and then, without another word, he turned and walked away.

Fashion still has the power to reduce many academics to embarrassed or indignant silence. Some of those to whom I spoke while preparing this article requested anonymity or even refused to address the subject. ("The F-Word". Lingua Franca April 1991: 17–18.)

Paragraphs Are Unified by a Single Purpose or Theme

Regardless of whether a paragraph is deductively or inductively structured, readers can generally follow the logic of a discussion better when a paragraph is unified by a single purpose. Paragraphs that lack a central idea and that wander from subject to subject are apt to confuse readers, making them wonder what they should pay attention to and why.

To ensure that each paragraph is unified by a single idea, Francis Christensen, in Notes Toward a New Rhetoric (NY: Harper & Row, 1967), has suggested that we number sentences according to their level of generality. According to Christensen, we would assign a 1 to the most general sentence and then a 2 to the second most general sentence, and so on.

Christensen considers the following paragraph, which he excerpted from Jacob Bronowski's The Common Sense of Science, to be an example of a subordinate pattern because the sentences become increasingly more specific as the reader progresses through the paragraph:

- The process of learning is essential to our lives.

- All higher animals seek it deliberately.

- They are inquisitive and they experiment.

- An experiment is a sort of harmless trial run of some action which we shall have to make in the real world; and this, whether it is made in the laboratory by scientists or by fox-cubs outside their earth.

- The scientist experiments and the cub plays; both are learning to correct their errors of judgment in a setting in which errors are not fatal.

- Perhaps this is what gives them both their air of happiness and freedom in these activities.

Christensen is quick to point out that not all paragraphs have a subordinate structure. The following one, which he took from Bergen Evans's Comfortable Words, is an example of what Christensen considers a coordinate sequence:

- He [the native speaker] may, of course, speak a form of English that marks him as coming from a rural or an unread group.

- But if he doesn't mind being so marked, there's no reason why he should change.

- Samuel Johnson kept a Staffordshire burr in his speech all his life.

- In Burns' mouth the despised lowland Scots dialect served just as well as the "correct" English spoken by ten million of his southern contemporaries.

- Lincoln's vocabulary and his way of pronouncing certain words were sneered at by many better educated people at the time, but he seemed to be able to use the English language as effectively as his critics.

Paragraphs Must Logically Relate to the Previous Paragraph(s)

Readers also expect paragraphs to relate to each other as well as to the overall purpose of a text. Establishing transitional sentences for paragraphs can be one of the most difficult challenges you face as a writer because you need to guide the reader with a light hand. When you are too blatant about your transitions, your readers may feel patronized.

To highlight the connections between your ideas, you can provide transitional sentences at the end of each paragraph that look forward to the substance of the next paragraph. Or, you can place the transition at the beginning of a paragraph looking backward, as Valerie Steele does in the following example:

Can a style of dress hurt one's professional career? True to form most academics deny that it makes any difference whatsoever. But a few stories may indicate otherwise: When a gay male professor was denied tenure at an Ivy League university, some people felt that he was punished, in part, for his dress. It was "not that he wore multiple earrings" or anything like that, but he did wear "beautiful, expensive, colorful clothes that stood out" on campus.

At the design department on one of the campuses of the University of California system, a job applicant appeared for her interview wearing a navy blue suit. The style was perfect for most departments, of course, but in this case, she was told – to her face – that she "didn't fit in, she didn't look arty enough".

Another bit of evidence that suggests dress is of career significance for academics is the fact that some universities (such as Harvard) now offer graduate students counseling on how to outfit themselves for job interviews. The tone apparently is patronizing ("You will need to think about an interview suit and a white blouse"), but the advice is perceived as necessary.

The phrase "another bit of evidence" beginning the second paragraph refers back to the topic sentence that began the first paragraph, "Can a style of dress hurt one's professional career?"

When evaluating your transitions from paragraph to paragraph, question whether the transitions appear too obtrusive, thereby undercutting your credibility. At best, when transitions are unnecessary, readers perceive explicit transitional sentences to be wordy; at worst, they perceive such sentences as insulting. (After all, they imply that the readers are too inept to follow the discussion.)

Vary the length of paragraphs to reflect the complexity and importance of the ideas expressed in them. Different ideas, arguments, and chronologies warrant their own paragraph lengths, so the form of your text should emerge in response to your thoughts. To emphasize a transition in your argument or to highlight an important point, you may want to place critical information in a one- or two-sentence paragraph.

Paragraphs Are Influenced by the Media of Writing

As much as any of the above guidelines, you should consider the media and genre where your text will appear. For as much as paragraphs are shaped by the ideas being expressed, they are also influenced by the genre of the discourse.

For instance, newspapers and magazines produced for high-school educated readers tend to require much shorter paragraphs than those published in academic journals. When evaluating how you have structured your ideas, however, pay attention to whether you have varied the length of your paragraphs. Long chunks of text without paragraph breaks tend to make ideas seem complicated, perhaps even inaccessible to less educated audiences. In turn, short paragraphs can create a list-like style, which intrudes on clarity and persuasive appeal. Because long paragraphs tend to make a document more complicated than short paragraphs, you should question how patient and educated your readers are.

Paragraphs Flow When Information Is Logical

Paragraphs provide a visual representation of your ideas. When revising your work, evaluate the logic behind how you have organized the paragraphs.

Question whether your presentation would appear more logical and persuasive if you rearranged the sequence of the paragraphs. Next, question the structure of each paragraph to see if sentences need to be reordered. Determine whether you are organizing information deductively or according to chronology or according to some sense of what is most and least important. Ask yourself these five questions:

- How is each paragraph organized? Do I place my general statement or topic sentence near the beginning or the end of each paragraph? Do I need any transitional paragraphs or transitional sentences?

- As I move from one idea to another, will my reader understand how subsequent paragraphs relate to my main idea as well as to previous paragraphs? Should any paragraphs be shifted in their order in the text? Should a later paragraph be combined with the introductory paragraph?

- Should the existing paragraphs be cut into smaller segments or merged into longer ones? If I have a concluding paragraph, do I really need it?

- Will readers understand the logical connections between paragraphs? Do any sentences need to be added to clarify the logical relationship between ideas? Have I provided the necessary forecasting and summarizing sentences that readers will need to understand how the different ideas relate to each other?

- Have I been too blatant about transitions? Are all of the transitional sentences and paragraphs really necessary or can the reader follow my thoughts without them?

- AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group

Advantages of Drafting a Skeleton Essay Structure

Table of Contents

Writing is a complex process. You are in charge of coming up with what you’re about to say and how you’re going to say it. Then you have to be able to convey it in a way that others will get what you’re saying.

That’s no small feat. So, to help you, let me look at writing as a process with several skeleton essay structures . This can help in your ability to communicate clearly.

What Is a Skeleton Essay Structure?

Just like a skeleton gives a body its basic shape and gives muscles, tendons, and other body parts something to connect to, a skeleton essay structure shows how a piece of writing is put together . It can help plan and draft work in fiction writing, article writing, or copywriting.

Think of it as your writing’s GPS. If you don’t enter a location and at least quickly look at the route you want to take, you probably will not arrive on the most efficient road. You’ll probably get there, but it could take longer.

Reasons Why You Should Use a Skeleton Essay Structure

1. having the freedom to be inspired.

Some writers think an outline will stop them from being creative, but that’s usually not the case. When I don’t have a strategy, I feel like I have to stick to the subtopic I’m working on at the time. The structure of your essay’s skeleton keeps you on track and gives you ideas .

2. The Bucket Effect

Your skeleton outline’s parts are like empty buckets, each holding blocks of a different color. If you think one bucket would perform better in another place, you can reposition it and all the colored blocks with it.

3. Research With Structure

With a skeleton outline, you don’t have to go all over the Internet looking for statistics that relate to your topic.

Your skeleton outline gives you sub-topics that help you search in a much more focused way. You should know that the more organized your research is, the fewer reasons to follow random research.

How to Start Writing Your Skeleton Essay Structure

1. start with your main points.

Assume you’ve been requested to write an essay about how to concentrate while writing. The first stage is to decide on your primary points. You make the call.

You’re ready to go on to details if you’re satisfied with your three primary points or however many you decide to employ.

2. Sort Your Details

Many writers are familiar with an awkward experience. You’ve chosen a topic and supported it with three or four specifics, each leading into the next. You started studying one of the specifics and discovered that the rest of your post is based on one supporting point, so you must go back and start over.

3. Start Writing!

If you’ve carefully approached the first two phases, this last one will be a snap. Your research is complete, and the article is organized; all that remains is transforming the information into sentences and paragraphs.

Is it feasible to write without a skeleton essay structure ? Without a doubt. The shorter the piece, the better it is to write on the spur of the moment. However, if you use an outline, you will produce better work in less time.

Abir Ghenaiet

Abir is a data analyst and researcher. Among her interests are artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing. As a humanitarian and educator, she actively supports women in tech and promotes diversity.

Explore All Essay Outline Tool Articles

How to write a synthesis essay outline.

One of the most interesting assignments you could have is writing a synthesis essay. For a college or university student,…

- Essay Outline Tool

Learning the Structure of an Informational Essay

Academic writing assignments, primarily essays, are required of all college and university students. That’s because they think it will aid…

The Correct Way to Structure an Article

Writing non-fiction has a set format that can be followed, which makes it not all that different from writing fiction.…

Exploring the Structure of a Response Essay

You will typically be expected to write in a formal and impersonal voice when you are given the assignment of…

Writing a Persuasive Essay? Use This Structure!

Writing essays is a requirement of your academic program as a college student. Whether you love them or loathe them,…

Writing a Proposal Essay? Read This!

Are you writing a proposal essay? To write it correctly, we have to know what a proposal essay actually is.…

An Awesome Essay Skeleton in 5 Simple Steps

I know what you’re wondering, what is the difference between an essay skeleton and an essay outline? To be honest, there is very little difference other than the outline tends to come equipped with a little more meat. The essay skeleton is, as the name suggests, just a basic frame of reference that helps students organize their ideas and define what goes where. In most cases, it does not have too much content other than the titles and subtitles and maybe topic sentences.

A thesis statement is also a welcome edition to the skeleton. In comparison, an outline will usually have brief paragraphs that define what the segment will talk about. The skeleton is usually very heavily edited throughout the writing process.

So, why even bother creating an essay skeleton, you wonder? Simple, because it will serve as a boilerplate for all your written assignments. And I do mean all of them. Forever!

Let’s dive in and see how is this even possible.

Table of Contents

What is an essay skeleton.

The skeleton is the framework that guides your writing . Think of it this way. If you wanted to build a house, the first thing you’d do is to draw a design, layout of the rooms, placement of the electric and water appliances, doors and windows, and similar. The skeleton is just like that, only for writing. If you do it properly, it will help you organize your research and writing, which saves time and lowers stress. So let’s dig in and see what can you do to make an awesome essay skeleton.

Understanding the Structure

Understanding the essay’s structure is crucial. Learn the anatomy of an essay: introduction, body, and conclusion. This comprehension guides your essay’s direction. In almost every situation you will come across, written work will have only three main parts – the introduction, the body, and the conclusion.

While in most cases there are some elements that must be added later such as the abstract or the bibliography , the three core elements never change.

Essay Skeleton Examples

Depending on the length of your paper, each part will vary in size and can encompass several sub-sections. It is important that you outline these immediately, as it helps define what you need to focus on. For example, a standard essay structure may look like this:

- Introduction

- Body topic 1

- Body topic 2

- Body topic 3

- Bibliography

If you need to write a longer paper, say 10-15 pages that requires primary or secondary research, then you would use something like this:

- Research question

- Thesis statement

- Literature review

- Body topic 4

- Body topic 5

Selecting the Main Points

Choose the main points wisely. They form the backbone of your essay skeleton. Prioritize key arguments that align with your thesis statement. Don’t go into too much detail, but rather focus on those elements that make the core of your essay. If you’re writing about World War II, pick 3-5 main points and create body paragraphs first, and only then develop the other parts. This way you will be more prepared and know what to write about.

Crafting a Strong Thesis

Crafting a robust thesis statement is pivotal. It succinctly summarizes the purpose of your essay and sets the roadmap for your skeleton.

Building the Body

The body of your essay skeleton fleshes out your main points. Arrange them logically, ensuring coherence and progression.

Incorporating Evidence

Support your main points with credible evidence. This can include statistics, quotes, or scholarly references. Strengthen your essay’s structure with substantial support.

Conclusion and Recap

Conclude your essay skeleton with a concise recap. Reinforce your thesis and summarize the key arguments. A well-constructed skeleton ensures a robust essay.

Related Posts

10 Tips To Study Effectively

How To Buy Essays Online? A Safety-First Guide For Students!

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Law School Toolbox®

All the tools you need for law school success

From Bare Bones to Meaty Analysis: How to Skeleton Outline Your Essay

December 15, 2014 By Ariel Salzer Leave a Comment

1. Get with the Times

Note the start time and the time when you should be moving on from outlining your answer to actually writing it. Plan to spend about a quarter to a third of the total allotted time in planning mode—just you, your fact pattern and your scratch paper—no typing.

2. Look to the Call for Help

Immediately read the call of the question first. This will help to orient you toward the question being asked and give you any structural clues your Professor may have left for you.

3. Build an Issue “Skeleton”

Read the fact pattern the first time. Note on your scratch paper any issues you see that you think may be triggered by the facts you have in front of you and the rules you’ve learned over the semester. If you’re not sure about something, write it down anyway, but put a question mark. Underline or highlight any facts that seem important. Leave space between each issue you jot down so you have room to write below each one. Think of this as the “skeleton stage.” You’re laying down the bones of your essay.

4. “Flesh Out” the Skeleton with the Facts

Read the facts for the second time. This time, try highlighting every fact and asking yourself whether it fits into the skeleton you’ve constructed, and if so, where. The goal here is to “find a home” for every fact, if possible. In matching the facts up and writing them under the issues you’ve mapped out on your scratch paper, you’re taking a valuable step toward a more structured, coherent and concise essay. Think of this step as “fleshing out” the skeleton you’ve built. Adding the facts that go with each issue is like wrapping muscle onto the bones.

Whether your Professor throws in facts that don’t matter, e.g. “red herring” facts will depend on her individual exam writing style. For each fact, though, at least ask yourself “does this fact matter?” Challenge yourself to pin each legally significant fact to an element from one of the rules triggered by the issues you’ve spotted and put in your skeleton. Check off each highlighted fact so you can tell at a glance whether you’ve used it yet or not. Note: I’m not saying you should actually spend time writing the full rule out in your skeleton. Hopefully by the time you get to exams, you know the rule in your head well enough to not have to write it down.

5. Write! Write! Write!

Either IRAC or follow an integrated approach. Which style you use will depend on what your individual Professor is looking for. Write based on the structure you’ve come up with. Hopefully, with the comprehensive blueprint you’ve made, you won’t have to stop and think about what to say, you’ll just type quickly and efficiently until you’re finished!

Want more law school tips? Sign up for our free mailing list today.

And check out these helpful posts:

- Don’t Panic! Last Minute Tips for Final Exams

- Can You Fake It Till You Make It With Law School Final Exams?

- Rely on Systems, Not Willpower

- You’re Totally Unprepared for a Law School Exam! How to Avoid Disaster

Image Credit: Slavoljub Pantelic/ Shutterstock

Looking for some help to do your best in law school? Find out about our law school tutoring options.

About Ariel Salzer

Ariel Salzer is a tutor and mentor tutor for Law School Toolbox and Bar Exam Toolbox. Ariel has taught everything from conjunctions to calculus on four different continents. A primary and secondary school educator in the U.S. and abroad before law school, Ariel has always had penchant for teaching and editing. As a student at the University of San Francisco School of Law, Ariel tutored Torts and led 1L workshops on time management, exam preparation, legal writing, and outlining. As the chief Technical Editor on the Executive Board of the USF Law Review, Ariel was in charge of ensuring the accuracy of thousands of legal citations, and has become a Bluebook expert. She also served as a Case Counsel for the USF Moot Court program, and received CALI awards for high-scoring two classes, including Legal Research and Writing. After practicing law as a product liability litigator in California for a number of years, Ariel found her way back to teaching and now enjoys helping students find success in their law school classes and on the bar exam.

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want Better Law School Grades?

Sign Up for Our Exam Tips!

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Copyright 2024 Law School Toolbox®™

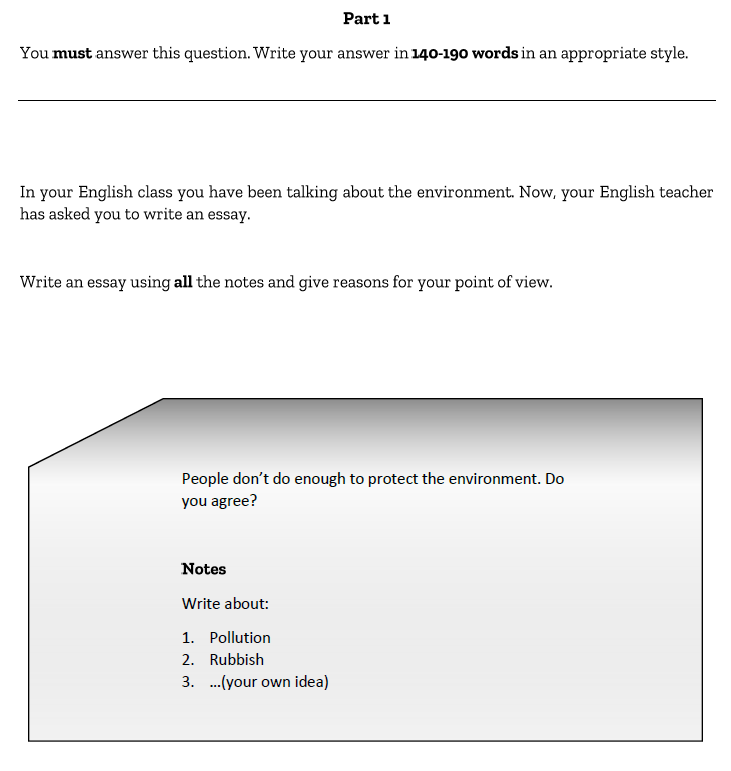

Breakout English

First (FCE) B2 Essay Structure – Essay Skeletons

There have been many occasions where my students have no time to learn the correct B2 essay structure for a Cambridge B2 First exam. Course books often do a great job of providing model answers, useful phrases and much more. However, sometimes people just want to be spoon-fed the correct way to write an essay. Well, are you hungry?

What is an essay skeleton?

An essay skeleton provides you with the base for an essay, without including any of the content. It includes all the necessary linkers, transitions and placeholders to emulate the ideal B2 essay structure. However, it is incomplete. In an ideal word, these skeletons can be memorised and adapted to any topic that you may find in the B2 First exam. Obviously, it isn’t likely to always be a perfect fit, so it can’t replace learning how to write an essay from scratch. However, if you are short on time or really struggling to produce a passing essay, this skeleton may be helpful.

B2 essay structure

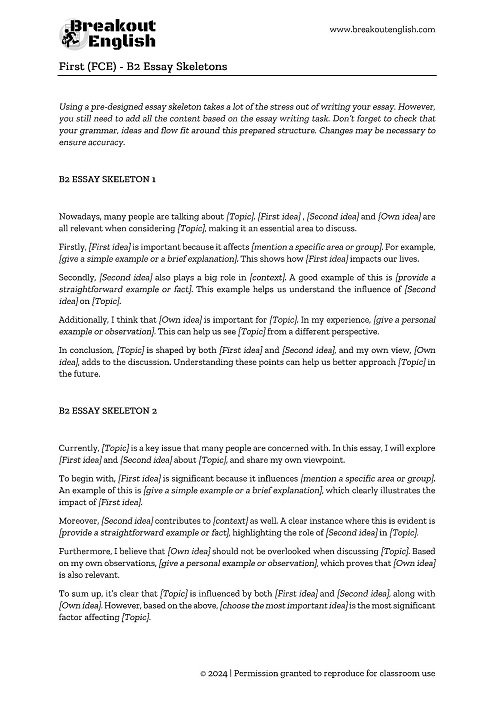

A Cambridge B2 First essay has a reasonably set structure. This is because the tasks are always similar. Take a look at the task below:

When we analyse the task, the most obvious structure is to write 5 paragraphs. This allows us to keep a clear separation between our three points. It also gives us plenty of opportunities for lovely linking words . With a word limit of 190 words, these paragraphs will be quite short, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be clear and effective.

Our standard paragraph plan for a B2 essay structure is…

- Introduction – Including a thesis statement that mentions the 3 areas of focus

- Body paragraph 1 – In this case about pollution

- Body paragraph 2 – In this case about rubbish

- Body paragraph 3 – Our own idea (for example, endangered animals)

- Conclusion – Summarise the 3 areas and optionally choose the most important

The two proposed essay skeletons below follow this paragraph plan in order to produce the perfect B2 essay every time.

The materials

We’ve designed two essay skeletons. They are similar but have subtle differences. Either one of them can be used with any topic that may come up in the B2 First exam. If you want to practise using the essay skeletons, try it out with a B2 essay task .

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Skeleton Outline – How To Use It In Writing?

If you do anything just to put off your writing, you might be stuck in a vicious cycle of procrastination.

This time, instead of simply powering through the writer’s block, you can try to alter your approach. Finding out about the skeleton outline method gave me a fresh attack plan for every piece of writing I needed to do. Instead of staring at a blank page for hours, not knowing where to start, I know exactly what points I need to get across in which paragraph. Ultimately, skeleton outlining has made my writing more efficient , less stressful, and easier to manage. And the best thing is – it’s so simple you’ll wonder how come the idea never crossed your mind!

What is a Skeleton Outline and Why Should Writers Care?

A skeleton outline is a framework you build to make content creation smoother. It’s the bare bones of your article/book/essay – ready for you to add meat and skin on top. Let’s translate that into the terminology of digitally written documents. With skeleton outlining, you want to build the heading structure and write down the main ideas to include under each heading. In a way, creating this type of outline helps you break down your project into manageable chunks . The idea behind skeleton outlining is to organize your writing before you type a single word. Planning this way results in a concise piece of writing . You build your writing up in layers, never losing sight of the big picture. This type of planning works for any kind of writing, whether you’re in charge of creating a white paper , a blog post, a podcast episode, or a fiction book.

Skeleton Outline – How it Helps in Writing:

1. don’t lose track.

Did you ever get halfway through your blog post only to realize you can’t remember the other points you wanted to make? If this sounds like you, chances are that the quality of your writing will rise significantly as soon as you integrate skeleton outlining into your routine. Setting up an outline skeleton with short notes in advance will let you focus on what you’re writing right now and know exactly what you need to write later on. That way, you’ll cover all the details without losing track of the big picture. Content and essay writers who need to reach a particular word count will love working with a skeleton outline – you can pre-calculate how long each heading needs to be to reach your target length!

2. Take It Step By Step

When you have your outline nailed down, it doesn’t matter if you write from top to bottom or from the middle out. Filling out part by part will make the whole writing process faster and help you beat procrastination. Work in little bits and tackle the easier sections first for a motivation and productivity boost !

3. Reorganize Easily

A skeleton outline makes it easy to reorganize the text you wrote if you decide to change the structure later on. Minimal editing is required! Programs like MS Word and Scrivener let you move headings (and the text under each) by simply dragging and dropping. That’s far easier than cutting, scrolling, and then pasting each paragraph separately!

How to Create a Skeleton Outline and Write Faster

So, what exactly does a skeleton outline look like? Well, it depends on the kind of writing you do. Here, I’ll share my process, which is tailored for blogging . Here’s what this article’s skeleton looks like:

Step 1 – Create a Heading Structure

This heading structure is the first thing that I created for this article, right after doing my research. This article is rather simple – it includes four H2 headings and six H3 subheadings. In some cases, the skeleton may get pretty intricate, going as far as including H4 subheadings. I wasn’t sure whether to put the “How to” or the “How it helps” section first, so I dragged them around a bit and settled for this structure in the end. In essence, your headings should cover the basic concepts, and subheadings are reserved for details and specifics.

Step 2 – Add Details and Research Notes

Now you can refine your structure further deciding where intros, transitions, lists, and other parts of the article will go. This will help you follow a pre-set structure if you need to, but I omit this step to retain structural flexibility. Apart from structural details, you can also add notes from your research to help you cover everything. I usually label research notes with a colored highlight just to be sure I don’t accidentally leave them in the finished article. If that sounds too complex, a program like Scrivener can make keeping track of research simpler for you.

Step 3 – Start Adding Meat

Now, there’s only one thing left to do – write, write, and write! You can fill in your outline in order or jump from part to part. It doesn’t matter because your skeleton outline won’t let you stray far from your main points. Case in point – I wrote this “How to” section first, even though it’s located at the end of the article! Bonus Tip: There is a lot of great outlining software for writers in the market that you can check out. These apps can help you structure your stories and other compositions faster and easier.

It’s not easy to create something great if you don’t know what it’s supposed to look like. Setting up an outline before you start writing will give you the freedom to focus on the details without worrying if your work makes sense when you zoom out. After all, it’s true that preparation is half the battle. Do you create an outline before writing? How do you approach building your content? Next up, you may want to explore a guide on how to create a synthesis essay outline .

Get your free PDF report: Download your guide to 100+ AI marketing tools and learn how to thrive as a marketer in the digital era.

Rafal Reyzer

Hey there, welcome to my blog! I'm a full-time entrepreneur building two companies, a digital marketer, and a content creator with 10+ years of experience. I started RafalReyzer.com to provide you with great tools and strategies you can use to become a proficient digital marketer and achieve freedom through online creativity. My site is a one-stop shop for digital marketers, and content enthusiasts who want to be independent, earn more money, and create beautiful things. Explore my journey here , and don't miss out on my AI Marketing Mastery online course.

- my research

- contributions and comments

writing skeletons

In order to get into the hang of academic writing it is sometimes helpful to examine closely the way in which other writers structure their work.

Swales and Feak (1) offer the use of skeleton sentences to achieve this. This where all of the content is stripped out of a paragraph in order to reveal the syntactic moves. They suggest that those wishing to improve their writing should experiment with putting their own content into these skeletons. This is the equivalent of walking in someone else’s footprints.

Here are some that Barbara Kamler and I use in our workshops on academic writing.

SKELETON ONE

(1) This chapter begins with a brief discussion of…………….(key theoretical approach you will take in your research) its history and major theorists.

(2) Next, I look at how ……………. (state the problem you are researching) is constructed in education.

(3) Then the chapter examines the literature about …………..( the problem you are addressing) that has been produced over the last …………. years.

(4) The chapter concludes with a look at some notable scholars …………..( names) from ………………..(name the theory again ) perspective.

From Ladson Billings, G (1999) Preparing teachers for diverse student populations: a critical race theory perspective, in A Iran-Nejad and P. D Pearson (Eds) Review of Research in Education. (pp. 211-247)WashingtonDC: American Educational Research Association.

SKELETON TWO

In this paper I discuss the main arguments that deal with the issue of…………

(2) it is my purpose to highlight the ……………… by pointing to…………….

(3) The paper is structured as follows. After giving an overview of the scope of the …………. I review the particular……………

(4) Next I provide a summary of …………….

(1) Finally in the last two sections I consider several implications for ……. and argue that…………….

Adapted from Lavie, J (2006) Academic discourse on school based teacher collaboration: revising the arguments. Educational Administration Quarterly 42 (5) 773-805.

SKELETON THREE

The thesis builds on and contributes to work in the field of __________________________

(2) Although a number of studies ( ) have examined _______________, there has not been a strong focus on ____________________________________________________.

(3) As such, this study provides additional insights about ______________________.

(4) This research differs from previous studies in …………. by identifying/documenting/ ………….

(5) In doing this it draws strongly on the work of ………… and …………. who……………

Adapted from Dunsmire, P (1997) Naturalizing the future in factual discourse: a critical linguistic analysis of a project event. Written Communication 14 (2) 221-264.

SKELETON FOUR

The thesis differs from other studies of_____________________.

(2) It owes a factual and interpretative debt to ________________________and _____________________ and__________________.

(3) In other respects it has benefited from the _________________ presented by _____________ and from ____________’s treatment of ________________ ( ).

(4) In these writings it is possible to find descriptions and analyses of____________ ________________________________which this thesis does not intend to match.

(5) What it rather does is to present a broader perspective on ______________ than is usually managed, with a more consistently maintained ________________, a greater attention to ____________________, a fuller sense of the range of _____________within a framework which conveys ________________________.

(6) If it is successful in these respects, then much is owed to______________________.

Adapted from Jones K (2003) Education in Britain: 1944 to the present. Oxford: Polity Press.

(1) Swales, J and Feak, C 1994 Academic writing for graduate students. University of Michigan Press. Second edition now in print.

Share this:

About pat thomson

16 responses to writing skeletons.

Thanks Pat. I’ve found this really useful in writing, especially when I’ve been stuck for ideas. It’s very similar to the ‘Writing Frames’ we give children when structuring genres for them!

I too found this useful way to scaffold the writing process for inexperienced academic writers like myself.

i think it can be quite helpful at the finishing stage leroy where you are now.. so use it to get the thesis abstract crisp

Pingback: Patter | PhD Blog (dot) Net

Pingback: why do doctoral researchers get asked to read so much? | patter

Pingback: the pleasure of texts… | patter

Very useful and timely, thank you!

Pingback: writing a road map – christmas present one | patter

Pingback: Translating Data | writing skeletons

Pingback: Sentence starters, prompts and skeletons | Joanne Hill

Pingback: www.thomson - Talk

Pingback: writing skeletons | roehampton dance ma dissertation 2015

These examples are really useful, thank you; I will definitely utilise them. A friend used a similar skeleton to construct an abstract and completed the abstract within 1/2 hour, after agonising over it for days.

Very clear examples. So helpful indeed

Pingback: your MC for this paper is… | patter

Thank you so much, this is very helpful, even for ESL students! And for teaching as well.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Search for:

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

patter on facebook

Recent Posts

- white ants and research education

- Anticipation

- research as creative practice – possibility thinking

- research as – is – creative practice

- On MAL-attribution

- a brief word on academic mobility

- Key word – claim

- key words – contribution

- research key words – significance

- a thesis is not just a display

- should you do a “side project”?

- the ABC of organising your time

SEE MY CURATED POSTS ON WAKELET

Top posts & pages.

- I can't find anything written on my topic... really?

- aims and objectives - what's the difference?

- writing a bio-note

- headings and subheadings – it helps to be specific

- connecting chapters/chapter conclusions

- the literature review - how old are the sources?

- five ways to structure a literature review

- connecting chapters/chapter introductions

- avoiding the laundry list literature review

- research as creative practice - possibility thinking

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, why you shouldn't copy skeleton templates for the sat/act essay.

SAT Writing , ACT Writing

Creating your own essay skeleton can go a long way towards helping you prepare for the SAT or ACT essay. Having an essay template ready to go before you take the test can reduce feelings of panic, since it allows you to control at least some of the unknowns of a free-response question. It can even be helpful to look at other people’s essay skeletons to get an idea what your own essay template should look like.

But when does using an essay skeleton go from a great idea to a huge mistake? Keep reading to find out.

feature image credit: Skeletons taking a selfie @ Street art @ Walk along the Amstel canal @ Amsterdam by Guilhem Vellut , used under CC BY 2.0 /Cropped from original.

UPDATE: SAT Essay No Longer Offered

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});.

In January 2021, the College Board announced that after June 2021, it would no longer offer the Essay portion of the SAT (except at schools who opt in during School Day Testing). It is now no longer possible to take the SAT Essay, unless your school is one of the small number who choose to offer it during SAT School Day Testing.

While most colleges had already made SAT Essay scores optional, this move by the College Board means no colleges now require the SAT Essay. It will also likely lead to additional college application changes such not looking at essay scores at all for the SAT or ACT, as well as potentially requiring additional writing samples for placement.

What does the end of the SAT Essay mean for your college applications? Check out our article on the College Board's SAT Essay decision for everything you need to know.

What Is An Essay Skeleton?

An essay skeleton, or essay template, is basically an outline for your essay that you prewrite and then memorize for later use/adaptation . Usually, an essay skeleton isn’t just an organizational structure—it also includes writing out entire sentences or even just specific phrases beforehand.

"But how can you do this, and more importantly, what’s the point?" I hear you cry (you sure manage to get out a lot of words in one cry).

Creating an essay template for the current SAT essay is pretty simple, as the SAT prompts tend to fall into one of six categories :

- What should people do?

- Which of two things is better?

- Support or refute counterintuitive statements (Is it possible that [an unlikely thing] is true?)

- Cause and effect (is X the result of Y?)

- Generalize about the state of the world

- Generalize about people

Because the prompts are, at the core, all "yes or no?" questions, you can somewhat customize your introduction and conclusion. Doing this is especially helpful if you tend to choke under pressure or are worried about your English language skills—you can come up with grammatically correct templates beforehand that you can memorize and then use on the actual test (filling in the blanks, depending on the prompt).

Formulating an essay template for the ACT is a little more tricky, as the new ACT essay asks you to read an excerpt, consider three perspectives, come up with your own perspective, and then discuss all the perspectives in the essay using detailed examples and logical reasoning. It’s possible to come up with a useful template, but I’ve not really come across any students using templates in the 200+ ACT essays I’ve graded.