Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay

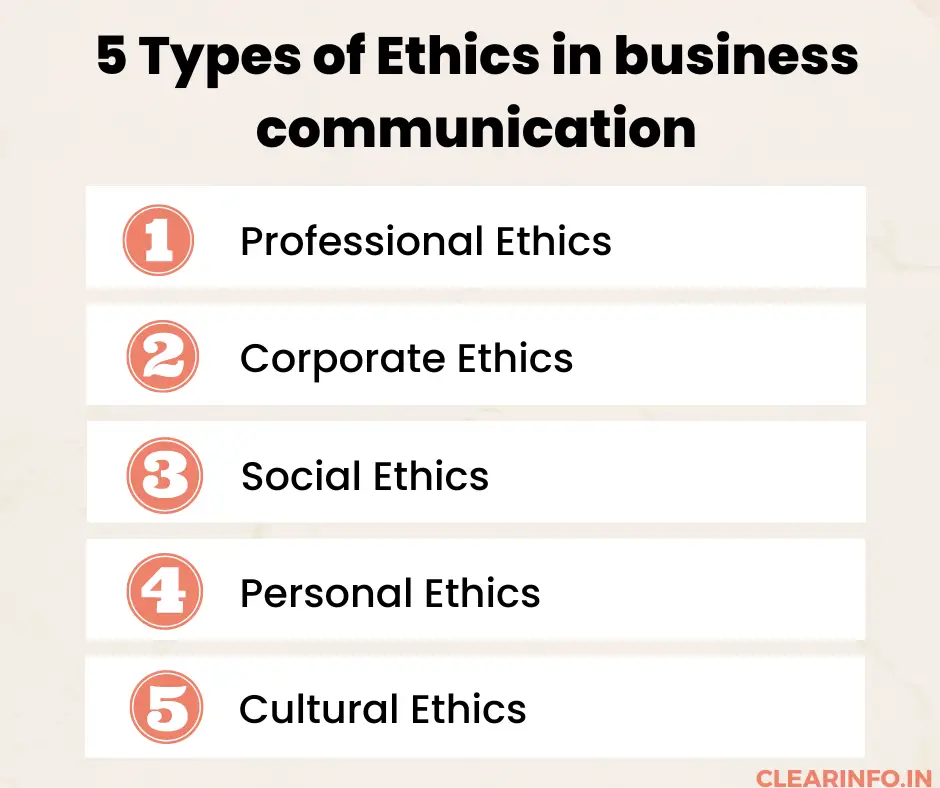

Introduction, what is communication ethics, how can one observe ethics in communication, unethical communication, importance of ethics in communication.

In any organization, the workplace needs to be run in such a way that every person feels part of the organization. On many occasions, decisions are made by the leaders and supervisors, leaving the subordinates as mere observers. Self-initiative is crucial in solving some of the problems that arise and as such, every employee is expected to possess self initiative.

Communication ethics is an integral part of the decision making process in an organization. Employees need to be trained on the importance of ethics in decision making so as to get rid of the blame game factor when wrong choices are made. The working place has changed and the employees have become more independent in the decision making process.

The issue that arises is whether employees make the right decision that would benefit the company or they make the wrong choices that call for the downfall of the company. Some organizations have called for the establishment of an ethics program that can aid and empower employees so that unethical actions would be intolerable. This is because occasionally, bad decisions destroy organizations making the whole decision making process unethical.

Some programs on good ethics can help in guiding the employees in the process of decision making. This would ensure the smooth running of organizations and instances of unethical decision making would be null. An ethical decision making process is important in ensuring that the decisions made by the employees are beneficial to organization welfare and operations.

Ethical communication is prudent in both the society and the organizations. The society can remain functional if every person acted in a way that defines and satisfies who they are. However, this could be short lived because of the high probability of making unethical decisions and consequently, a chaotic society. For this reason, it would be of essence to make ethical rules based on a set guidelines and principles.

Ethical communications is defined by ethical behavioral principles that include honesty, concern on counterparts, fairness, and integrity. This cannot be achieved if everyone acted in isolation. The action would not be of any good to most people. Adler and Elmhorst (12) note that actions should be based on the professional ethics where other professionals have to agree that the actions in question are ethical and standard. If a behavior is standard there is nothing to fear if exposed to the media.

However, unethical behavior can taint the reputation of an organization. An action needs to do good to most people in the long run. Adler and Elmhorst (12) note that this golden rule needs to be applicable in organizations. Failure to do this, it becomes an obstacle to this principle.

In achieving the ideals, several obstacles are bound to arise in the process of decision making. Rationalizations often distract individuals involved in making tough decisions. According to the Josephson Institute of ethics (2002) the false assumption that people hold on to that necessity leads to propriety can be judgmental that unethical tasks are part of the moral imperative.

For example, assuming that a particular action is necessary and it lies in the ethical domain is a mere assumption that can be suicidal to an organization. This necessity assumption often leads to a false necessity trap that prompts individuals to take actions without putting into account the cost of doing or failing to do the right thing (Josephson Institute of ethics, Para 5). As part of a routine job, it is likely to be an obstacle in the sense that an individual is doing what he/she got to do.

For example, morality of professional behavior is often neglected at the workplace and on most occasions, people do what they feel is justifiable although it is morally wrong even if not in that context. Individuals often assume that if everyone is doing a certain action, then it is ethical. However, this is not the right way to go as the accountability of individuals and their behaviors should not be treated as a norm in the organization. For example, we could assume that everyone tells lies in an organization.

This assumption is uncertain because lying is unethical and can hinder the achievement of certain goals in an organizational. It may not bring harm at the given time but in the long run it may be chaotic. An observation by the Josephson Institute of Ethics (para 9) is that false rationalization is just an excuse to commit unethical conduct. Basically, the assumption that an action would not harm somebody or the organization does not give the limelight to committing unethical deeds.

The management of an organization should make the ethics of their employees their concern and business. The assumption that employees can make ethical decisions without advising them on what is ethical and then blaming the employees in case the plan backfires is unethical. In ensuring that the actions carried by employees are ethical, the human resource management should set up ethical programs within the organization.

As noted by Flynn (30) the principles of ethical behavior are bound to develop if an organization itself practices acts of ethics. For example, honesty, fairness, concern for others, morality and truthfulness can be achieved if code of ethical conduct is practiced in organization. In achieving an ethical decision some steps need to be followed. Decisions making should be ethical and objective to the organization and its components.

According to Flynn (37) the rules of the Texas instrument company noted that the legality of an action is of imperative importance. If for example an action is illegal then the law should not be broken because an action has to be taken. Instead, the executioner of the action needs to stop right away. Actions need to comply with the values of an organization. If the actions cannot comply with the set organizational values then the action may not fit well.

An action carried should not make someone feel bad or the actions carried should not be harmful to the executioner. The public image of an action in the newspaper or media should be considerate. An action should be within a given timeframe and be done even if its appearance will affect it. For an action that one is not sure, they are obligated to ask and if not satisfied they continue asking until an answer is got (Flynn 37).

Communication ethics is important in the operation of an organization. The way in which decision making is carried in an organization determines the outcome. Ethical decision making process is necessary in an organization. Some of the obstacles that restrict rationalization are merely based on assumptions. They lead to downfall or negative ramifications that affect the organizations. Organizational managers are advised to take decision making of employees as their own concern.

Legitimacy of actions is important and so are the values, because some actions maybe illegal or values fail to meet the organizational values. This may have negative impact if they are not illegal or in line with organizational goals. In general, ethical decision making process is important as it saves a company from the problems it would face for its unethical actions

Works Cited

Adler, Ronald B. and Jeanne Marquardt Elmhorst. Communicating at Work . 9 th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008. Print.

Flynn, Gillian. “Make Employee Ethics Your Business.” Personnel Journal ( 1995) 74.6: 30-37. Web.

Josephson Institute of Ethics. “Making Ethical Decisions—Part Five: Obstacles to Ethical Decision Making.” Accounting Web (2002 ). Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 28). Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/

"Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." IvyPanda , 28 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay'. 28 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

1. IvyPanda . "Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

- Unethical Workplace Behavior: How to Address It

- Business Ethics of Negotiation

- Business Ethics Theories and Unethical Actions Punishment

- Extreme Working Conditions

- Business Ethics: Reflective Essay

- Ethics Program: Hyatt Hotels Corporation Code of Ethics

- Corporate Ethical Challenges

- Value and Ethics in Organizations

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.7: Ethical Communication

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 137751

- Multiple Authors

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Defining Communication Ethics

Communication has ethical implications. Ethics in the broadest sense asks questions about what we believe to be right and wrong. Communication ethics asks these questions when reflecting on our communication. Everyday we have to make communicative choices, and some of these choices will be more or less ethical than other options. It is because we have these different options that our ethics are tested. We can never really say that something is completely ethical or unethical, especially when it comes to communication. “Murdering someone is generally thought of as unethical and illegal, but many instances of hurtful speech, or even what some would consider hate speech, have been protected as free speech. This shows the complicated relationship between protected speech, ethical speech, and the law” (Communication in the Real World, 2013).

When we make communication choices, the question of whether they are ethical or not depends on a variety of situational, personal, and and/or contextual variables that can be difficult to navigate. Many professional organizations have created ethical codes to help guide this decision-making, and the field of Communication Studies is no different. In 1999, the National Communication Association officially adopted the Credo for Ethical Communication. The NCA Credo for Ethical Communication is a set of beliefs that Communication scholars have about the ethics of human communication (NCA Legislative Council, November 1999).

We should always strive for ethical communication, but it is particularly important in interpersonal interactions. We will talk more about climate, trust and honesty, and specific relationships in the coming chapters, but at the most basic level you should strive to make ethical choices in your communication. Communication is impactful. Our communication choices have lasting impacts on those with whom we engage. While ethics is a focus on what is right and wrong, it is not easy to navigate. What is right in one circumstance may not be in another. To help us make our way through difficult ethical choices we must be competent.

Communication Competence

Communication competence focuses on communicating effectively and appropriately in various contexts (Kiessling & Fabry, 2021). In order to be competent you must have knowledge, motivation, and skills. You have been communicating for most of your life, so you have observational knowledge about how communication works. You are also now a college student actively studying communication so your knowledge will continue to increase. As you learn more about communication, continue to observe these concepts around you and you will expand the information you have to draw on in any given context. In addition to having basic information you must also be motivated to better your own communication and you need to develop the skills necessary to do so. One way to improve your communication competence is to become a more mindful communicator. “A mindful communicator actively and fluidly processes information, is sensitive to communication contexts and multiple perspectives, and is able to adapt to novel communication situations” (Communication in the Real World), 2013. Your path to improving your interpersonal communication competence is just beginning. You will learn more about specific aspects of mindfulness, such as listening, conflict management, deception, etc., in the coming chapters. For now we hope you are motivated to improve your knowledge and grow your skills.

Communication: Ethics

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2022

- Cite this reference work entry

- Ronald C. Arnett 2

155 Accesses

Communication ethics assumes a distinctive perspective of bioethics, engaging it from two principal standpoints: biopolitics and post-human. These two perspectives yield a targeted standpoint on communication ethics. The notion of communication ethics does not suggest a uniform or universal assertion about what is and is not ethical. The term “communication ethics” is more aptly understood within (Gadamer, H. G. (1988). Truth and method . New York: The Crossroads Publishing Company. (Original work published 1975)) conception of “horizon” (p. 217). Theorized in visual terms, a horizon implies a series of images in the distance; the horizon is composed of multiplicity and fuzzy clarity. A horizon is akin to an impressionistic painting that invites a number of glimpses and perspectives, all temporal and partial. The question of bioethics from the vantage point of communication ethics does not dictate correct answers. The task is to open the conversation by unmasking unstated presuppositions. The first obligation of communication ethics is the act of understanding, not the conversion of the ignorant into correct ethical alignment. Communication ethics understood as content or a sense of the good furnishes moral gravity, simultaneously assuming the pragmatic reality of multiplicity. Distancing communicative ethics from universal truth counters imposition, bullying, and historical campaigns reminiscent of colonialism and totalitarianism in the name of self-righteous assurance.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Arnett, R. C. (2012). Biopolitics: An Arendtian communication ethic in the public domain. Communication and Cultural/Critical Studies, 9 (2), 225–233.

Google Scholar

Arnett, R. C., Fritz, J. M. H., & Bell, L. M. (2009). Communication ethics literacy: Dialogue and difference . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bonhoeffer, D. (1972). Letters & papers from prison (The enlarged edition. Ed. E. Bethge.). New York: Macmilian Publishing. (Original work published 1953).

Ellul, J. (1990). The technological bluff (G. W. Bromily, Trans.). Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. (Original work published 1964).

Foucault, M. (1997). “Society must be defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976 (D. Macey, Trans.). New York: Picador.

Hyde, M. J. (2013). Perfection: Coming to terms with being human . Waco: Baylor University Press.

Hyde, M. J., & King, N. M. P. (2010). Communication ethics and bioethics: An interface. The Review of Communication, 10 , 156–171.

Kuhn, T. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1962).

MacIntyre, A. (1984). After virtue: A study in moral theory (2nd ed.). Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. (Original work published 1981).

MacMillian, A. (2011). Empire, biopolitics, and communication. Journal of Communication Inquiry, XX (X), 1–6.

McKerrow, R. E. (2011). Foucault’s relationship to rhetoric. The Review of Communication, 11 , 253–271.

Negri, A. (2008). The labor of the multitude and the fabric of biopolitics. M. Coté (Ed.). (S. Mayo & P. Graefe with M. Coté, Trans.). Meditations: Journal of the Marxist Literary Group, 23 (2), 1–7.

Further Readings

Hyde, M. J., & Herrick, J. A. (2013). After the genome: A language for our own biotechnological future . Waco: Baylor University Press.

King, N. M. P., & Hyde, M. J. (Eds.). (2014). Bioethics, public moral argument, and social responsibility . New York: Routledge. (Original work published 2012)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Ronald C. Arnett

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ronald C. Arnett .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Center for Healthcare Ethics, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Henk ten Have

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Arnett, R.C. (2016). Communication: Ethics. In: ten Have, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global Bioethics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09483-0_109

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-09483-0_109

Published : 19 January 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-09482-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-09483-0

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

35 Communication Ethics and Virtue

Janie M. Harden Fritz (PhD, University of Wisconsin-Madison) is Professor of Communication and Rhetorical Studies at Duquesne University. She is a past President of the Eastern Communication Association and the Religious Communication Association. Her research interests include communication and virtue ethics, professional civility, problematic workplace relationships, communication ethics and leadership, and religious communication. She is the author of Professional ↵Civility: Communicative Virtue at Work (Peter Lang, 2013), co-author (with Ronald C. Arnett and Leeanne M. Bell) of Communication Ethics Literacy: Diversity and Difference (Sage, 2009), and co-editor (with Becky L. Omdahl) of volumes 1 and 2 of Problematic Relationships in the Workplace (Peter Lang, 2006, 2012).

- Published: 06 December 2017

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Virtue approaches to communication ethics have experienced a resurgence over the last decades. Tied to rhetoric since the time of Aristotle, virtue ethics offers scholars in the broad field of communication an approach to ethics based on character and human flourishing as an alternative to deontology. In each major branch of communication scholarship, the turn to virtue ethics has followed a distinctive trajectory in response to concerns about the adequacy of theoretical foundations for academic and applied work in communication ethics. Recent approaches to journalism and media ethics integrate moral psychology and virtue ethics to focus on moral exemplars, drawing on the work of Philippa Foot and Rosalind Hursthouse, or explore journalism as a MacIntyrean tradition of practice. Recent work in human communication ethics draws on MacIntyre’s approach to narrative, situating communication ethics within virtue structures that protect and promote particular goods in a moment of narrative and virtue contention.

I. Introduction

The field of communication, as it has been studied in the West, has existed for over two millennia, beginning with the ancient Greeks. Questions of ethics were inherent in this domain of scholarly inquiry from the start. 1 Virtue ethics, present explicitly or implicitly throughout the field’s history, has resurfaced as an explicit approach to communication ethics within the last three decades.

The current status of virtue ethics in the field of communication is tied to the field’s scholarly development and identity. The academic domain of communication hosts three loosely affiliated disciplines claiming different histories. 2 One derives from the oral speech tradition, referred to here as human communication studies ; another focuses on mediated (or mass) communication, referred to here as media studies ; and another reflects the profession of journalism. 3 During the last decades, elements of these three areas converged to form the interdisciplinary field of communication, united by the study of communicative practices and/or messages and their meanings and/or effects. 4

Gehrke (2009) suggested that the question of ethics may be “the single most persistent and important question in the history of the study of communication and rhetoric.” 5 This enduring question grows in salience as new media and digital communication technologies reconfigure the interactive landscape of public and private life, placing new demands on journalism and media ethics. 6 Calls for theoretical and philosophical approaches supporting communication ethics scholarship in a globalizing world and concerns about fragmentation as the area of communication ethics expands have elicited volumes such as the inaugural and comprehensive Handbook of Communication Ethics . 7 In this context, virtue ethics offers communication ethics scholars an alternative to complement and enhance existing approaches.

Questions of communication ethics arise whenever human communicative behavior (1) involves significant intentional choice regarding ends and means to secure those ends, (2) holds the potential for significant impact on others, and (3) can be judged according to standards of right and wrong. 8 Ethical issues are inherent in the communication process—human existence is a cooperative, social endeavor in which communicative action holds the potential for influence and necessarily bears moral valence. 9 Communication theorists look to Aristotle’s phronesis , or practical wisdom, to anchor the issue of ethical choice. 10 Ethical decisions are not formulaic, but are discerned in response to the historical moment and constraints of particular situations.

Some journalism and media ethicists understand ethics as a quest for the universal end of human and social improvement, which extends beyond rules and regulations. 11 Plaisance (2002) connects media practices with the human condition in noting the role of media in upholding what it means to be human, a position echoed by Gehrke (2009) , who observes that human communication scholars have long considered the symbolic capacity a defining feature of the human being, necessary for personal and communal well-being. 12 Tying communicative practices to perennial questions related to the good life for human beings, personally and collectively, places communication squarely within the purview of virtue ethics, which offers theoretical and practical grounding for the role of communication in human flourishing.

II. A Turn to Virtue Ethics

During the last fifteen years, explicitly articulated Aristotelian or neo-Aristotelian virtue ethics perspectives have increased, particularly in journalism and media studies. 13 In human communication studies, Aristotelian and neo-Aristotelian approaches have enjoyed consistent representation from classical rhetoricians. 14 Now virtue ethics scholarship is making an appearance in other areas of human communication, such as argument, integrated marketing communication, interpersonal and organizational communication, marital communication, and public relations/crisis communication. 15 In journalism/media studies and in human communication studies, the turn to virtue ethics traces an identifiable trajectory. The remainder of this chapter highlights major developments in virtue ethics in these two broad areas of communication scholarship.

One of the major issues emerging from this review is how virtues are best conceptualized, which depends, in turn, on the view of human persons embraced by a given theoretical perspective. Are virtues discrete, internal, individualized properties of persons, much like personality characteristics or traits? Or are virtues situated within larger traditions, such as philosophical or religious worldviews or narratives, which then find embodiment through acting persons’ communicative practices? This concern has been articulated most explicitly in human communication studies, where similar questions related to the nature of communication and the locus of meaning have given rise to discussions of alternative perspectives on communication. 16

III. Virtue Ethics in Journalism and Media Studies

I. answering the call of the historical moment.

Klaidman and Beauchamp’s (1987) The Virtuous Journalist foreshadowed the growing interest in virtue ethics in journalism and media. Beforehand, journalism ethics had taken a largely atheoretical, descriptive approach, loosely based on deontological ethics. 17 Klaidman and Beauchamp argued for both duty-based and virtue ethics as professional guides. Three years later, Edmund B. Lambeth (1990) assessed Alasdair MacIntyre’s (1981) work as offering a new perspective for journalism scholarship, particularly journalism ethics. A decade later, virtue-based pieces appeared increasingly in the media ethics literature.

Two major concerns propelled the turn to virtue in journalism and media ethics. One was the need for a philosophical framework for applied journalism and media practice to assist practitioners in navigating an increasingly challenging and dynamic commercial context with the integrity befitting a member of a tradition of professional practice. 18 Another was to develop an adequate philosophical foundation for global media ethics to guide practice in multiple media contexts and across cultural boundaries. 19 To these concerns was added a recent third: the need to take account of developments in the human sciences in ways that could inform ethical theorizing. 20

ii. Representative Scholarship

Scholars in journalism and media ethics appreciate the holistic approach of virtue ethics, which asks questions about what sort of person one should be and what sort of life one should live, rather than what rules one should follow. 21 The broad framework of virtue ethics maintains clarity and rigor without resting on culture-bound norms and values. Some also see virtue ethics as consistent with a malleable, responsive human nature that develops over time while retaining its distinctively human character. 22

Sandra Borden (2007) develops an ethical theory for professional journalists based on MacIntyre’s virtue ethics. She identifies practice-sustaining virtues emergent from the tradition of journalism as practice and as responsive to the environment of contemporary journalism. For example, courage and ingenuity protect journalism against corruption by external goods, such as market competitiveness; stewardship sustains journalists as institutional bearers of the practice by supporting the excellence in news reporting necessary for the success of news organizations; and justice, courage, and honesty support the collegial relationships needed to achieve journalism’s goals through constructive criticism and recognition of excellence, including mutual verification of information. 23

Scholars pursuing virtue ethics in global media, the most prominent of whom are Nick Couldry and Patrick Lee Plaisance, push off from the work of Clifford G. Christians, the leading journalism and media ethics scholar. Christians has worked deductively to establish a foundation for media ethics grounded in dialogic communitarianism, an approach identifying transcultural ethical protonorms and resting on assumptions of the sacredness of life and a relational ontology of the human person. 24 Couldry and Plaisance see virtue ethics as a more fruitful direction for a global media ethics than dialogic communitarianism.

Couldry (2010) articulates four perspectives other than virtue ethics available for media ethics: Christian humanism, based on the work of Christians; nomadism, based on the work of Deleuze or Foucault; Kantian deontological ethics; and Levinasian ethics. 25 Couldry, contrasting virtue ethics and deontology, notes that Aristotelian virtue ethics focuses on human beings rather than on any rational being, an approach responsive to potential areas of agreement about the good among human beings and to the reality of historical contingency. Although Couldry recognizes the possibility of integrating concerns for the right and the good, he argues for virtue ethics because of its open-endedness and applicability to multiple cultures and for its prioritizing of the good for human beings. Virtue ethics offers a starting point in the nature of human beings, a more universal foundation than culturally bound understandings of duty. 26

Couldry ( 2010 , 2013 ) draws on the work of Bernard Williams (2002) and Sabina Lovibond (2002) to identify “communicative virtues” of accuracy and sincerity connected to the human need for reliable information from others about the environment, identifying media as a type of MacIntyrean practice. 27 Two regulative ideals are internal to journalistic practice: circulating information contributing to individual and community success within a given sphere, and providing opportunities to express opinions aimed at sustaining “a peaceable life together” despite disagreements related to “conflicting values, interests, and understandings.” 28 Couldry’s work assumes the relevance of media ethics for both media consumers and producers.

In his later work, Couldry (2013) highlights Ricoeur’s focus on hospitality as a key issue for media ethics. 29 This expanded treatment of Ricouer, beyond the brief mention of Ricoeur’s critique of Rawls in Couldry (2010) , leads to the potential of a “virtue of care through media” consistent with both Onora O’Neill’s (1996) work and that of Lovibond (2013) , who offers an integrated perspective on rights and duties in her perspective on “ethical living” in the media. 30 “Living well through media” and “ethical living through media” together suggest a constructive approach to a media ethics grounded in virtue and duty. 31

Plaisance (2013) considers a virtue ethics approach more robust than a deductive approach predicated on identifying universal principles. The inductive nature of virtue ethics permits identification of “behaviors and practices that are directly linked to human flourishing,” locating their warrant in the human species. 32 Plaisance points to Philippa Foot’s (2001) natural normativity as the virtue ethics approach most suitable for the global media context, noting that a focus on “traditional virtues and vices such as temperance and avarice” permits us to “see the concrete connections between the conditions of human life—the presence and absence of the various necessary ‘goods’—and the objective reasons for acting morally.” 33 These concrete connections are made manifest in selected exemplars of virtuous media practice, which Plaisance (2015) offers in an extended treatment of virtue ethics in the context of media and public relations.

Plaisance (2015) continues his ongoing project to integrate virtue ethics with the findings of moral psychology by presenting and interpreting the results of a study of exemplary professionals in journalism and public relations in a book-length treatment. He provides models of good behavior—exemplars of excellence—rather than failures in ethics, following the lead of positive psychology scholars, 34 as well as strengthening virtue ethics theory in the area of media practices, noting that “our understanding of virtue in professional media work remains both abstract and rudimentary.” 35 His goal is to develop a theory that accounts for virtuous practice, and he identifies factors that lead to or thwart practitioners’ moral action.

Plaisance builds his study on the twin pillars of Philippa Foot’s virtue ethics and Jonathan Haidt’s moral psychology. 36 He interprets the study’s qualitative and quantitative findings by drawing on MacIntyre, O’Neill, and Rosalind Hursthouse. 37 Chapters on professionalism and public service, moral courage, and humility and hubris describe contexts within which the participants in his study developed “patterns of virtue” in their professional lives, thereby becoming moral exemplars of virtues for journalism and media practice. 38

The work of journalism and media ethics scholars in virtue ethics takes two forms. One, represented by Borden and Couldry (and Christians), moves outward, focusing on understandings of the human person that embed the human person within a meaning structure, such as a MacIntyrean tradition or another framework. The other, represented by Plaisance, moves inward to identify influences on personal dispositions to explain virtuous behavior. As will be seen in the next section, virtue ethics in human communication scholarship appears to break along similar lines, although the theoretical discussion surrounding these approaches emerges from a different set of underlying concerns.

IV. Virtue Ethics in Human Communication Studies

I. an ongoing story.

Human communication ethics theorists trace their lineage to Aristotle’s connection of persuasion and virtue, and to Quintilian’s assumption that great orators should have excellent character as well as superior oratorical skills. 39 Some version of ethics containing virtue language consistent with an Aristotelian perspective was taken for granted in human communication ethics through the early part of the twentieth century. Moral character was considered key to excellent speaking, and moral training in the tradition of the humanities was considered necessary for effective speech. 40 The mid-1930s, however, witnessed a shift in which virtue-related terms were “redefined into mental health standards” consistent with a mental hygiene approach. 41 Bryngelson (1942), for example, listed “sincerity, humility, and confidence” as characteristics of excellent speakers, but his assumptions about human beings, consistent with mechanistic reductionism and laced with psychoanalytic language, were far different from those undergirding the virtues associated with classical rhetoric. 42

As the human communication field developed during the twentieth century, the basis for communication ethics underwent significant changes. Neo-Aristotelian understandings locating ethics in human nature and society recaptured explicit status in rhetorical studies mid-century in response to challenges from existential understandings of the human being, which denied an essential human nature. 43 In the face of crumbling philosophical foundations for moral judgments characterizing the 1960s and 1970s, rhetoricians who maintained faith in humanist or neo-Aristotelian understandings of human nature as a foundation for moral and ethical judgments kept the language of virtue ethics present in the scholarly literature, 44 even as approaches that understood ethics as “contingent, limited, and variable” surged. 45

Concurrently, methodological differences between social scientists and those committed to the rhetorical and philosophical tradition grew more pronounced. By this point, “the very possibility of moral judgment had been undermined by the prevalence of social scientific and psychotherapeutic understandings of human behavior,” and rhetoric took up ethics as one of its defining elements. 46 Although communication scientists implicitly assumed some human good guiding their quest to predict and explain communicative behavior and thereby improve human well-being, the philosophical foundations for that good and the substance of that well-being, as well as questions of ethics, were seldom, if ever, addressed. 47 The law-like generalizations characterizing communication science, which rested on a materialist ontology accompanied by empiricist methodology, did not accommodate axiological claims. 48

The subfield of interpersonal communication exemplifies an area characterized predominantly by quantitative social science assumptions and methodology. 49 Only recently have questions of ethics from this perspective been raised and addressed explicitly in the scholarly literature. 50 However, an approach to interpersonal communication rooted in dialogic philosophy found traction in a narrative understanding of human communication inspired by Alasdair MacIntyre’s work, which provided a context in which an approach to communication ethics consistent with virtue ethics could be addressed.

ii. By Way of Narrative

The narrative turn in the communication field paralleled that of many areas of academic inquiry seeking to reclaim a sense of human meaning and values lost with the adoption of social scientific methodologies steeped in rationalism and naturalism. 51 Within this context, Walter Fisher articulated the narrative paradigm, an approach to communication that invited understandings of human engagement with the world beyond traditional rationality and reclaimed meaning structures jeopardized by modernism’s subversion of the “rational world paradigm” inherited from the ancients. 52 Ronald C. Arnett’s initial treatment of narrative, which incorporated Fisher’s theorizing, drew also on the scholarship of Stanley Hauerwas, whose work reflected the virtue ethics of Alasdair MacIntyre. 53 Later, MacIntyre’s work played a direct role in Arnett’s conceptualization of practices, traditions, and competing virtue structures in the public sphere. 54

Arnett critiqued the confounding of humanistic psychological approaches to dialogue, which centered meaning within the self, with philosophical approaches, which located meaning in the communicative space between persons emerging during dialogic encounter. 55 For humanistic, or third-force, psychologists, 56 such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, meaning resides within the human person and emerges within a developing self. For Martin Buber, communicative meaning emerges between persons in conversation who are responsive to what the situation calls for. 57 The locus of meaning is not in the mind of persons, but in the interaction, a joint construction of the two parties.

Arnett’s concern in differentiating these approaches focused on implications of the emphasis of humanistic psychology on the “ ‘real self,’ ” which he interpreted as challenging the legitimacy of roles that persons are called to enact in various life contexts and the struggles that persons undergo when seeking an appropriate response that may run counter to impulse. 58 Arnett’s concern was to reduce the unreflective importation of therapeutic language into contexts of public discourse. 59 An emphasis on phenomenological dialogue and narrative moves the focus of attention back to larger meaning structures that situate the self within guidelines that offer direction without assuming universal legitimacy. 60 Arnett (1989) , in his discussion of the importance of a common center for community or for relationships—a mission or goal that keeps people together and in conversation—made a theoretical connection between Buber’s work on dialogue and Fisher’s work on narrative. Narrative, a story larger than any of the participants and irreducible to the sum of their interactions, provides a common meaning center external to the self to bind persons together, even under conditions of personal dislike. 61 Arnett (1989) also conceptualized Buber’s “interhuman” as a story that emerges as participants “simultaneously engage in the writing of the narrative” in which each person becomes a vital participant. 62 Neither the self nor the other is the center—the narrative is. Two senses of narrative become relevant: narrative as a larger story or common center connecting persons who join in participation, and narrative emerging as a joint construction between two persons. Both senses locate meaning not in the person, but between or among persons. By then, narrative communication ethics, a response to the work of MacIntyre, Hauerwas, and Fisher, had been identified as an approach to communication ethics, distinguished from universal/humanitarian approaches in its constructed, rather than a priori, nature: narrative is “rooted in community … [and] … constituted in the common communication life of a people.” 63

Arnett’s joining of Fisher’s narrative perspective with Buber’s phenomenological dialogue provided a foundation for understanding the human person as an embedded agent consistent with a MacIntyrean understanding of narrative and tradition, a framework that emerged in a later treatment of dialogic civility in public and private relationships. Drawing from MacIntyre, Arnett and Pat Arneson (1999) framed narrative as a story gathering public assent that provides a location within which embedded agents find meaning and in which virtue is situated. Arnett (2005) applied this framework to the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Arnett, Fritz, and Bell (2009) identified narrative as the location within which a given communication ethic finds traction.

Arnett, Fritz, and Bell (2009) did not claim to be presenting a virtue ethic for communication. However, their work offers a potential conceptualization of a communicative virtue ethics that follows MacIntyre and Charles Taylor (1989) . In the face of the contemporary denial of a human nature that could supply the content of a substantive good to provide meaning and purpose for human life, or a telos , Arnett et al. situate virtue within narrative traditions. Arnett et al. appropriate Taylor’s (1989) notion of the inescapable experience of humans as moral agents located in a space of the good and on the value of human participation in ordinary life, particularly in its communicative, relational contexts, thereby conceptualizing communication ethics as centered on a particular substantive good or goods in human experience given meaning within a narrative structure.

Arnett et al.’s understanding of communication ethics as protecting and promoting goods of, for, and in human life refrains from explicit reference to an ontological telos for human beings. Their work explores communication ethics as a question of literacy related to different perspectives on the good emerging in a postmodern moment of virtue contention. Goods relevant to the virtues emerge from philosophical and religious frameworks or worldviews—narratives—that provide the substance of the good that defines human flourishing; approaches to communication ethics are situated within these virtue structures that define these underlying goods. Since these virtue structures are not shared publicly in today’s historical moment, they must be made explicit in order to identify the narrative ground upon which communicators stand with monologic clarity as they engage in dialogue. 64 From this surfacing of goods, learning from difference and the identification of particular interests emerge as interlocutors discover each other’s perspectives.

Arnett et al. do not assume that character-defining virtues, such as may exist, are best conceptualized as internal characteristics, mental properties, or elements of personality located within an individual self; instead, virtues emerge from worldviews, traditions, or narrative structures that situate persons. Virtues and goods, for Arnett et al., are tied to petite narratives, particular traditions, or worldviews within which persons are situated as embedded agents. In this sense, virtues are tied to character only inasmuch as persons are enactors of traditions of virtue, shaped and formed by those traditions. 65 One may derive from this work that engaging in communicative practices that protect and promote a given good may lead to the inculcation of virtuous character reflective of a particular narrative or worldview. Arnett et al.’s approach to ethics is rooted in an understanding of rhetorical contingency—human beings cannot stand above history, although they are able to glean temporal glimpses of alternative understandings of the world through dialogic engagement with others who inhabit different narratives or traditions. The key virtue or “good” in Arnett et al.’s dialogic communication ethics framework is openness to learning.

Communication ethics, then, can be conceptualized as communicative practices that protect and promote an underlying contextual good—for example, the relationship, the public sphere, health, organizational mission, or culture—assumed to hold meaning within a larger framework. The centrality of the good in ethical considerations guides Arnett et al.’s (2009) understanding of definitions of communication ethics appearing in the literature. These definitions highlight issues such as relativistic and absolute positions, ends and means, “is” and “ought,” and public and private domains of human life; careful discernment of what values are important; attentiveness to the historical moment; choice; information-based judgments; and the “heart” and care for others, all of which become goods protected and promoted by a particular definition of communication ethics. 66 Arnett et al. (2009) revisit approaches to communication ethics through the framework of protecting and promoting goods: universal/humanitarian; democratic; codes, procedures, and standards; narrative; and dialogic ethics. For example, a universal/humanitarian communication ethic protects and promotes the good of universal rationality and of duty, while a codes, procedures, and standards approach protects and promotes the good of agreed-upon regulations, and dialogic ethics protects and promotes what emerges unexpectedly between persons. Each of these approaches could be explored as a virtue ethics approach supporting a good connected to a particular human telos .

The next section explores recent developments in virtue ethics in human communication studies, most of which have emerged within the last decade. These treatments address several specific domains of communicative practice ranging from the interpersonal to the institutional level. Several of them find their roots in the work of MacIntyre.

iii. Virtue Ethics in Human Communication Studies

As noted earlier, the rhetorical tradition maintained a focus on virtue ethics since ancient times, although the ground for this approach departed occasionally from its Aristotelian foundations during the early twentieth century. The revival of interest in Aristotelian virtue ethics on the part of rhetorical scholars, propelled initially by the work of MacIntyre, prompted James Herrick (1992) to conceptualize rhetoric as a practice marked by internal goods. 67 Rhetorical virtues would be “enacted habits of character” prompting apprehension of the ethical nature of rhetorical contexts, appreciation of rhetorical discourse as a practice, and skilled enactment of rhetorical practice. 68

As interest in virtue ethics continued, additional work in rhetorical studies and other areas of human communication emerged. Aberdein (2010) developed a virtue theory of argumentation, expanding the circle of philosophers of virtue ethics theorists relevant to questions of communication. Aberdein draws on Linda Trinkaus Zagzebski’s (1996) work on epistemological virtues and Richard Paul’s (2000) investigation of virtues of critical thinking to identify argumentative virtues, including attention to detail, fairness in evaluating others’ arguments, intellectual courage, and inventiveness. Aberdein offers a typology of four categories of argumentational virtue: willingness to engage in argumentation; willingness to listen to others; willingness to modify one’s own position; and willingness to question the obvious. 69

Fritz’s (2013) work on civility as a communicative virtue draws on Kingwell (1995) , who addresses civility as a modality of virtuous communicative engagement in the public square. Kingwell offers a sociolinguistic understanding of politeness as “just talking,” a method of public deliberation taking place between citizens who hold different positions on issues but who seek to accomplish the shared good of collective decision-making. This approach is consistent with that of Shils, who understood civility as a civic virtue that “enables persons to live and work together by fostering the cooperative action that makes civilized life possible.” 70

Fritz (2013) interprets several domains of communication theory and research within the civility/incivility virtue/vice framework that connect to Kingwell’s (1995) appropriation of communicative pragmatics—tact, restraint, role-taking, and sensitivity to context as civil communication practices necessary for joint action in the public sphere. Civility embodies practical communicative habits of character that define virtuous public interpersonal communication, which protects and promotes the good of the public sphere. 71 In related fashion, Pat Arneson (2014) addresses the virtue of moral courage prompting a fitting response in the service of liberating others in her study of white women’s efforts during the mid-1800s and early 1900s in the struggle to fight racism against black Americans. One virtue perspective on interpersonal communication emerges from a positive approach to communication, which tracks the recent turn in the social sciences to positive approaches to human behavior. 72 Julien Mirivel (2012) suggests that communication excellence embodies virtues in interpersonal communication, employing Aristotle, MacIntyre, and Comte-Sponville (2001) as philosophical touchpoints. For example, the virtue of gentleness involves restraining impulses toward violence and anger, which requires face-attentiveness, or respect for others’ dialectical needs for autonomy and interconnectedness, manifested in deferential verbal forms of address and compliments

Nathan Miczo (2012) bases his approach to virtuous interpersonal communication on Aristotle, Hannah Arendt, Nietzsche, and Comte-Sponville. 73 Communicative virtue is “excellence in ‘words and deeds’ … [that] comprises the performance of behaviors indicative of engagement.” 74 Partners in discourse and a shared object of discourse between them constitute a vital relationship to the world that defines such engagement. Miczo focuses on four dispositions of the virtuous communicator: politeness, compassion, generosity, and fidelity. Politeness requires space for expression and listening. Compassion requires attentiveness to others, which helps bring forth their responses. Through generosity, persons contribute to the conversation to enrich it by sharing positions. Being committed to a position defines fidelity, taking and endorsing a stance. The twin commitments to assisting others in their expression and standing within a position are necessary conditions for dialogue.

Fritz (2013) , drawing on Arnett et al. (2009) and Arnett and Arneson (1999) and following Borden’s (2007) application of MacIntyre to the profession of journalism, articulates professional civility as a virtue-based interpersonal communication ethic for organizational settings. The theoretical foundation of professional civility connects elements from the dialogic civility framework and the conceptualization of civility as a communicative virtue to the notion of profession as practice from a MacIntyrean virtue ethics perspective. 75 Professional civility protects and promotes goods of productivity, place (the organization within which professional work is accomplished), persons (those with whom one works), and the profession itself.

V. Conclusion

Virtue ethics is rising to prominence as an approach to communication ethics. For journalism and media studies, the fit between the conceptual strengths of virtue ethics and issues salient to media practices provides a compelling rationale for application. Borden (2007) and Quinn (2007) , for example, identify virtue ethics as well suited to professional contexts in which journalists must make decisions rapidly, with little time for reflection. For human communication, approaches to virtue ethics offer communication a central theoretical role in meaningful human existence, as exemplified in the work of Herrick (1992) on rhetoric as virtuous practice.

The scholar with by far the largest effect on virtue approaches to communication ethics is Alasdair MacIntyre. His work is a key source for scholars in all areas of communication ethics, from human communication studies to journalism and media. Although some communication scholars take issue with MacIntyre’s conclusions, many find his analysis of the current moral predicament stemming from Enlightenment rationalism and the accompanying loss of a foundation for moral judgment compelling. 76 Taylor and Hawes (2011), for instance, identify themes across communication scholars’ responses to MacIntyre’s work, each suggesting a potentially constitutive role for communication in the enactment of virtue in human communities. In the area of journalism, MacIntyre’s work is foundational for Sandra Borden’s treatment of journalism as practice. Christians, John P. Ferré, and P. Mark Fackler (1993) address problems with the Enlightenment articulated by Alasdair MacIntyre as they seek to establish a new basis for media ethics.

MacIntyre’s work offers a framework resting in tradition and narrative that gives ground for the character traits supplied by virtue ethics, providing a place for the human person within a larger narrative. However, not all applications of virtue ethics in the communication field systematically engage a broad framework for virtue ethics. For example, Philippa Foot, Onora O’Neill, and Rosalind Hursthouse figure prominently in the virtue ethics adopted by media ethics theorists such as Couldry, Plasiance, and Quinn. Although the rationale for such appropriations is the fit between virtue ethics and the nature of the human person, communication scholars make little explicit effort to situate the person within a larger narrative framework or tradition within which virtue finds its form and expression in particular human communities.