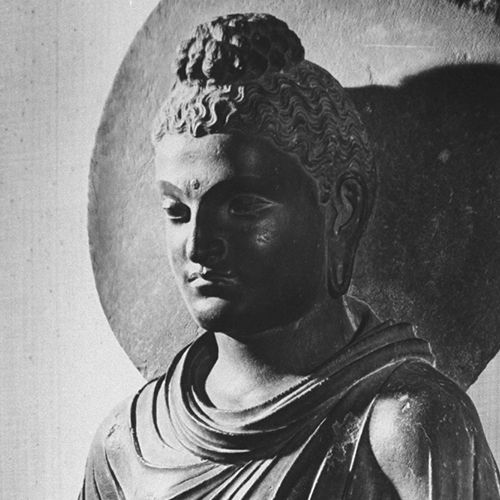

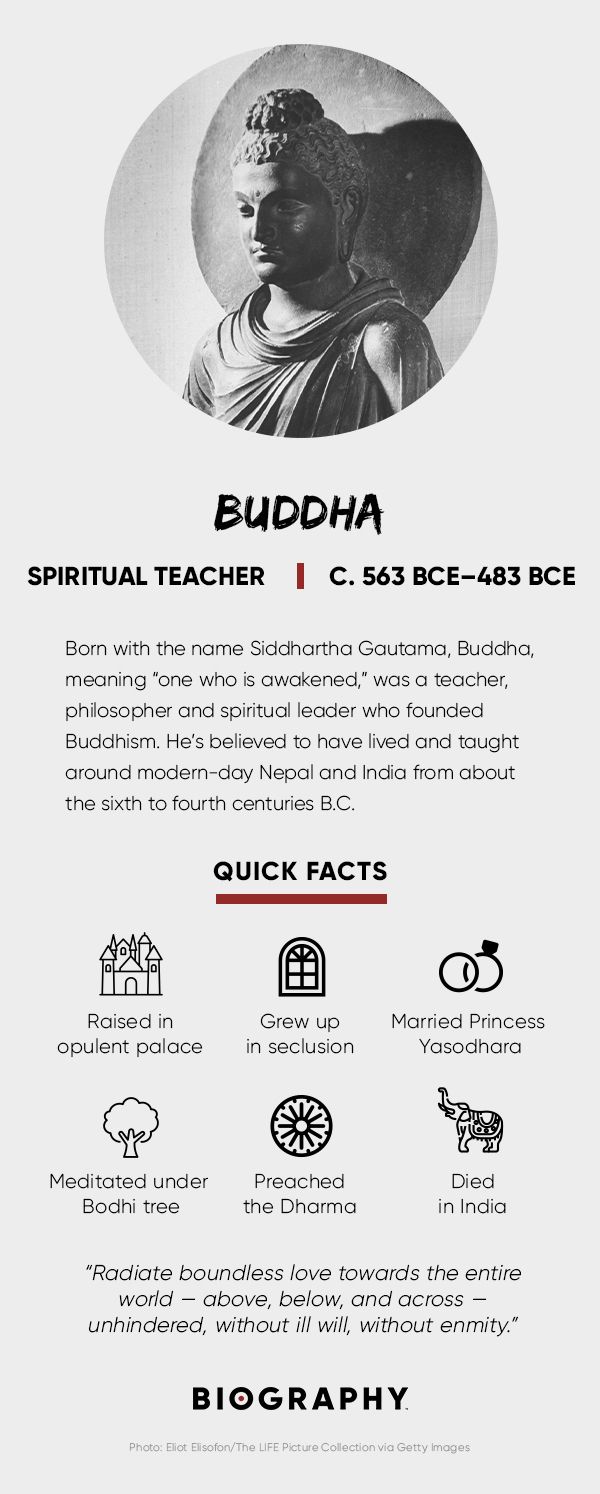

Who Was Buddha?

The name Buddha means "one who is awakened" or "the enlightened one." While scholars agree that Buddha did in fact exist, the specific dates and events of his life are still debated.

According to the most widely known story of his life, after experimenting with different teachings for years, and finding none of them acceptable, Siddhartha Gautama spent a fateful night in deep meditation beneath a tree. During his meditation, all of the answers he had been seeking became clear, and he achieved full awareness, thereby becoming Buddha.

Buddha was born in the 6th century B.C., or possibly as early as 624 B.C., according to some scholars. Other researchers believe he was born later, even as late as 448 B.C. And some Buddhists believe Gautama Buddha lived from 563 B.C. to 483 B.C.

But virtually all scholars believe Siddhartha Gautama was born in Lumbini in present-day Nepal. He belonged to a large clan called the Shakyas.

In 2013, archaeologists working in Lumbini found evidence of a tree shrine that predated other Buddhist shrines by some 300 years, providing new evidence that Buddha was probably born in the 6th century B.C.

Siddhartha Gautama

Siddhartha ("he who achieves his aim") Gautama grew up the son of a ruler of the Shakya clan. His mother died seven days after giving birth.

A holy man, however, prophesied great things for the young Siddhartha: He would either be a great king or military leader or he would be a great spiritual leader.

To protect his son from the miseries and suffering of the world, Siddhartha's father raised him in opulence in a palace built just for the boy and sheltered him from knowledge of religion, human hardship and the outside world.

According to legend, he married at the age of 16 and had a son soon thereafter, but Siddhartha's life of worldly seclusion continued for another 13 years.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S BUDDHA FACT CARD

Siddhartha in the Real World

The prince reached adulthood with little experience of the world outside the palace walls, but one day he ventured out with a charioteer and was quickly confronted with the realities of human frailty: He saw a very old man, and Siddhartha's charioteer explained that all people grow old.

Questions about all he had not experienced led him to take more journeys of exploration, and on these subsequent trips he encountered a diseased man, a decaying corpse and an ascetic. The charioteer explained that the ascetic had renounced the world to seek release from the human fear of death and suffering.

Siddhartha was overcome by these sights, and the next day, at age 29, he left his kingdom, his wife and his son to follow a more spiritual path, determined to find a way to relieve the universal suffering that he now understood to be one of the defining traits of humanity.

The Ascetic Life

For the next six years, Siddhartha lived an ascetic life, studying and meditating using the words of various religious teachers as his guide.

He practiced his new way of life with a group of five ascetics, and his dedication to his quest was so stunning that the five ascetics became Siddhartha's followers. When answers to his questions did not appear, however, he redoubled his efforts, enduring pain, fasting nearly to starvation and refusing water.

Whatever he tried, Siddhartha could not reach the level of insight he sought, until one day when a young girl offered him a bowl of rice. As he accepted it, he suddenly realized that corporeal austerity was not the means to achieve inner liberation, and that living under harsh physical constraints was not helping him achieve spiritual release.

So he had his rice, drank water and bathed in the river. The five ascetics decided that Siddhartha had given up the ascetic life and would now follow the ways of the flesh, and they promptly left him.

The Buddha Emerges

That night, Siddhartha sat alone under the Bodhi tree, vowing to not get up until the truths he sought came to him, and he meditated until the sun came up the next day. He remained there for several days, purifying his mind, seeing his entire life, and previous lives, in his thoughts.

During this time, he had to overcome the threats of Mara, an evil demon, who challenged his right to become the Buddha. When Mara attempted to claim the enlightened state as his own, Siddhartha touched his hand to the ground and asked the Earth to bear witness to his enlightenment, which it did, banishing Mara.

And soon a picture began to form in his mind of all that occurred in the universe, and Siddhartha finally saw the answer to the questions of suffering that he had been seeking for so many years. In that moment of pure enlightenment, Siddhartha Gautama became the Buddha.

Armed with his new knowledge, the Buddha was initially hesitant to teach, because what he now knew could not be communicated to others in words. According to legend, it was then that the king of gods, Brahma, convinced Buddha to teach, and he got up from his spot under the Bodhi tree and set out to do just that.

About 100 miles away, he came across the five ascetics he had practiced with for so long, who had abandoned him on the eve of his enlightenment. Siddhartha encouraged them to follow a path of balance instead of one characterized by either aesthetic extremism or sensuous indulgence. He called this path the Middle Way.

To them and others who had gathered, he preached his first sermon (henceforth known as Setting in Motion the Wheel of the Dharma) , in which he explained the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, which became the pillars of Buddhism.

The ascetics then became his first disciples and formed the foundation of the Sangha, or community of monks. Women were admitted to the Sangha, and all barriers of class, race, sex and previous background were ignored, with only the desire to reach enlightenment through the banishment of suffering and spiritual emptiness considered.

For the remainder of his years, Buddha traveled, preaching the Dharma (the name given to his teachings) in an effort to lead others along the path of enlightenment.

Buddha died around the age of 80, possibly of an illness from eating spoiled meat or other food. When he died, it is said that he told his disciples that they should follow no leader, but to "be your own light."

The Buddha is undoubtedly one of the most influential figures in world history, and his teachings have affected everything from a variety of other faiths (as many find their origins in the words of the Buddha) to literature to philosophy, both within India and to the farthest reaches of the world.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Buddha

- Birth Year: 563

- Birth City: Lumbini

- Birth Country: Nepal

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Buddha was a spiritual teacher in Nepal during the 6th century B.C. Born Siddhartha Gautama, his teachings serve as the foundation of the Buddhist religion.

- Nacionalities

- Nepalese (Nepal)

- Death Year: 483

- Death Country: India

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Buddha Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/religious-figures/buddha

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: July 13, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous Religious Figures

7 Little-Known Facts About Saint Patrick

Saint Nicholas

Jerry Falwell

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

Saint Thomas Aquinas

History of the Dalai Lama's Biggest Controversies

Saint Patrick

Pope Benedict XVI

John Calvin

Pontius Pilate

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Buddha (fl. circa 450 BCE) is the individual whose teachings form the basis of the Buddhist tradition. These teachings, preserved in texts known as the Nikāyas or Āgamas , concern the quest for liberation from suffering. While the ultimate aim of the Buddha’s teachings is thus to help individuals attain the good life, his analysis of the source of suffering centrally involves claims concerning the nature of persons, as well as how we acquire knowledge about the world and our place in it. These teachings formed the basis of a philosophical tradition that developed and defended a variety of sophisticated theories in metaphysics and epistemology.

1. Buddha as Philosopher

2. core teachings, 3. non-self, 4. karma and rebirth, 5. attitude toward reason, primary sources, secondary sources, other internet resources, related entries.

This entry concerns the historical individual, traditionally called Gautama, who is identified by modern scholars as the founder of Buddhism. According to Buddhist teachings, there have been other buddhas in the past, and there will be yet more in the future. The title ‘Buddha’, which literally means ‘awakened’, is conferred on an individual who discovers the path to nirvana, the cessation of suffering, and propagates that discovery so that others may also achieve nirvana. This entry will follow modern scholarship in taking an agnostic stance on the question of whether there have been other buddhas, and likewise for questions concerning the superhuman status and powers that some Buddhists attribute to buddhas. The concern of this entry is just those aspects of the thought of the historical individual Gautama that bear on the development of the Buddhist philosophical tradition.

The Buddha will here be treated as a philosopher. To so treat him is controversial, but before coming to why that should be so, let us first rehearse those basic aspects of the Buddha’s life and teachings that are relatively non-controversial. Tradition has it that Gautama lived to age 80. Up until recently his dates were thought to be approximately 560–480 BCE, but many scholars now hold that he must have died around 405 BCE. He was born into a family of some wealth and power, members of the Śākya clan, in the area of the present border between India and Nepal. The story is that in early adulthood he abandoned his comfortable life as a householder (as well as his wife and young son) in order to seek a solution to the problem of existential suffering. He first took up with a number of different wandering ascetics ( śramanas ) who claimed to know the path to liberation from suffering. Finding their teachings unsatisfactory, he struck out on his own, and through a combination of insight and meditational practice attained the state of enlightenment ( bodhi ) which is said to represent the cessation of all further suffering. He then devoted the remaining 45 years of his life to teaching others the insights and techniques that had led him to this achievement.

Gautama could himself be classified as one of the śramanas . That there existed such a phenomenon as the śramanas tells us that there was some degree of dissatisfaction with the customary religious practices then prevailing in the Gangetic basin of North India. These practices consisted largely in the rituals and sacrifices prescribed in the Vedas. Among the śramanas there were many, including the Buddha, who rejected the authority of the Vedas as definitive pronouncements on the nature of the world and our place in it (and for this reason are called ‘heterodox’). But within the Vedic canon itself there is a stratum of (comparatively late) texts, the Upaniṣads , that likewise displays disaffection with Brahmin ritualism. Among the new ideas that figure in these (‘orthodox’) texts, as well as in the teachings of those heterodox śramanas whose doctrines are known to us, are the following: that sentient beings (including humans, non-human animals, gods, and the inhabitants of various hells) undergo rebirth; that rebirth is governed by the causal laws of karma (good actions cause pleasant fruit for the agent, evil actions cause unpleasant fruit, etc.); that continual rebirth is inherently unsatisfactory; that there is an ideal state for sentient beings involving liberation from the cycle of rebirth; and that attaining this state requires overcoming ignorance concerning one’s true identity. Various views are offered concerning this ignorance and how to overcome it. The Bhagavad Gītā (classified by some orthodox schools as an Upaniṣad ) lists four such methods, and discusses at least two separate views concerning our identity: that there is a plurality of distinct selves, each being the true agent of a person’s actions and the bearer of karmic merit and demerit but existing separately from the body and its associated states; and that there is just one self, of the nature of pure consciousness (a ‘witness’) and identical with the essence of the cosmos, Brahman or pure undifferentiated Being.

The Buddha agreed with those of his contemporaries embarked on the same soteriological project that it is ignorance about our identity that is responsible for suffering. What sets his teachings apart (at this level of analysis) lies in what he says that ignorance consists in: the conceit that there is an ‘I’ and a ‘mine’. This is the famous Buddhist teaching of non-self ( anātman ). And it is with this teaching that the controversy begins concerning whether Gautama may legitimately be represented as a philosopher. First there are those (e.g. Albahari 2006) who (correctly) point out that the Buddha never categorically denies the existence of a self that transcends what is empirically given, namely the five skandhas or psychophysical elements. While the Buddha does deny that any of the psychophysical elements is a self, these interpreters claim that he at least leaves open the possibility that there is a self that is transcendent in the sense of being non-empirical. To this it may be objected that all of classical Indian philosophy—Buddhist and orthodox alike—understood the Buddha to have denied the self tout court . To this it is sometimes replied that the later philosophical tradition simply got the Buddha wrong, at least in part because the Buddha sought to indicate something that cannot be grasped through the exercise of philosophical rationality. On this interpretation, the Buddha should be seen not as a proponent of the philosophical methods of analysis and argumentation, but rather as one who sees those methods as obstacles to final release.

Another reason one sometimes encounters for denying that the Buddha is a philosopher is that he rejects the characteristically philosophical activity of theorizing about matters that lack evident practical application. On this interpretation as well, those later Buddhist thinkers who did go in for the construction of theories about the ultimate nature of everything simply failed to heed or properly appreciate the Buddha’s advice that we avoid theorizing for its own sake and confine our attention to those matters that are directly relevant to liberation from suffering. On this view the teaching of non-self is not a bit of metaphysics, just some practical advice to the effect that we should avoid identifying with things that are transitory and so bound to yield dissatisfaction. What both interpretations share is the assumption that it is possible to arrive at what the Buddha himself thought without relying on the understanding of his teachings developed in the subsequent Buddhist philosophical tradition.

This assumption may be questioned. Our knowledge of the Buddha’s teachings comes by way of texts that were not written down until several centuries after his death, are in languages (Pāli, and Chinese translations of Sanskrit) other than the one he is likely to have spoken, and disagree in important respects. The first difficulty may not be as serious as it seems, given that the Buddha’s discourses were probably rehearsed shortly after his death and preserved through oral transmission until the time they were committed to writing. And the second need not be insuperable either. (See, e.g., Cousins 2022.) But the third is troubling, in that it suggests textual transmission involved processes of insertion and deletion in aid of one side or another in sectarian disputes. Our ancient sources attest to this: one will encounter a dispute among Buddhist thinkers where one side cites some utterance of the Buddha in support of their position, only to have the other side respond that the text from which the quotation is taken is not universally recognized as authoritatively the word of the Buddha. This suggests that our record of the Buddha’s teaching may be colored by the philosophical elaboration of those teachings propounded by later thinkers in the Buddhist tradition.

Some scholars (e.g., Gombrich 2009, Shulman 2014) are more sanguine than others about the possibility of overcoming this difficulty, and thereby getting at what the Buddha himself had thought, as opposed to what later Buddhist philosophers thought he had thought. No position will be taken on this dispute here. We will be treating the Buddha’s thought as it was understood within the later philosophical tradition that he had inspired. The resulting interpretation may or may not be faithful to his intentions. It is at least logically possible that he believed there to be a transcendent self that can only be known by mystical intuition, or that the exercise of philosophical rationality leads only to sterile theorizing and away from real emancipation. What we can say with some assurance is that this is not how the Buddhist philosophical tradition understood him. It is their understanding that will be the subject of this essay.

The Buddha’s basic teachings are usually summarized using the device of the Four Nobles’ Truths:

- There is suffering.

- There is the origination of suffering.

- There is the cessation of suffering.

- There is a path to the cessation of suffering.

The first of these claims might seem obvious, even when ‘suffering’ is understood to mean not mere pain but existential suffering, the sort of frustration, alienation and despair that arise out of our experience of transitoriness. But there are said to be different levels of appreciation of this truth, some quite subtle and difficult to attain; the highest of these is said to involve the realization that everything is of the nature of suffering. Perhaps it is sufficient for present purposes to point out that while this is not the implausible claim that all of life’s states and events are necessarily experienced as unsatisfactory, still the realization that all (oneself included) is impermanent can undermine a precondition for real enjoyment of the events in a life: that such events are meaningful by virtue of their having a place in an open-ended narrative.

It is with the development and elaboration of (2) that substantive philosophical controversy begins. (2) is the simple claim that there are causes and conditions for the arising of suffering. (3) then makes the obvious point that if the origination of suffering depends on causes, future suffering can be prevented by bringing about the cessation of those causes. (4) specifies a set of techniques that are said to be effective in such cessation. Much then hangs on the correct identification of the causes of suffering. The answer is traditionally spelled out in a list consisting of twelve links in a causal chain that begins with ignorance and ends with suffering (represented by the states of old age, disease and death). Modern scholarship has established that this list is a later compilation. For the texts that claim to convey the Buddha’s own teachings give two slightly different formulations of this list, and shorter formulations containing only some of the twelve items are also found in the texts. But it seems safe to say that the Buddha taught an analysis of the origins of suffering roughly along the following lines: given the existence of a fully functioning assemblage of psychophysical elements (the parts that make up a sentient being), ignorance concerning the three characteristics of sentient existence—suffering, impermanence and non-self—will lead, in the course of normal interactions with the environment, to appropriation (the identification of certain elements as ‘I’ and ‘mine’). This leads in turn to the formation of attachments, in the form of desire and aversion, and the strengthening of ignorance concerning the true nature of sentient existence. These ensure future rebirth, and thus future instances of old age, disease and death, in a potentially unending cycle.

The key to escape from this cycle is said to lie in realization of the truth about sentient existence—that it is characterized by suffering, impermanence and non-self. But this realization is not easily achieved, since acts of appropriation have already made desire, aversion and ignorance deeply entrenched habits of mind. Thus the measures specified in (4) include various forms of training designed to replace such habits with others that are more conducive to seeing things as they are. Among these is training in meditation, which serves among other things as a way of enhancing one’s observational abilities with respect to one’s own psychological states. Insight is cultivated through the use of these newly developed observational powers, as informed by knowledge acquired through the exercise of philosophical rationality. There is a debate in the later tradition as to whether final release can be attained through theoretical insight alone, through meditation alone, or only by using both techniques. Ch’an, for instance, is based on the premise that enlightenment can be attained through meditation alone, whereas Theravāda advocates using both but also holds that analysis alone may be sufficient for some. (This disagreement begins with a dispute over how to interpret D I.77–84; see Cousins 2022, 81–6.) The third option seems the most plausible, but the first is certainly of some interest given its suggestion that one can attain the ideal state for humans just by doing philosophy.

The Buddha seems to have held (2) to constitute the core of his discovery. He calls his teachings a ‘middle path’ between two extreme views, and it is this claim concerning the causal origins of suffering that he identifies as the key to avoiding those extremes. The extremes are eternalism, the view that persons are eternal, and annihilationism, the view that persons go utterly out of existence (usually understood to mean at death, though a term still shorter than one lifetime is not ruled out). It will be apparent that eternalism requires the existence of the sort of self that the Buddha denies. What is not immediately evident is why the denial of such a self is not tantamount to the claim that the person is annihilated at death (or even sooner, depending on just how impermanent one takes the psychophysical elements to be). The solution to this puzzle lies in the fact that eternalism and annihilationism both share the presupposition that there is an ‘I’ whose existence might either extend beyond death or terminate at death. The idea of the ‘middle path’ is that all of life’s continuities can be explained in terms of facts about a causal series of psychophysical elements. There being nothing more than a succession of these impermanent, impersonal events and states, the question of the ultimate fate of this ‘I’, the supposed owner of these elements, simply does not arise.

This reductionist view of sentient beings was later articulated in terms of the distinction between two kinds of truth, conventional and ultimate. Each kind of truth has its own domain of objects, the things that are only conventionally real and the things that are ultimately real respectively. Conventionally real entities are those things that are accepted as real by common sense, but that turn out on further analysis to be wholes compounded out of simpler entities and thus not strictly speaking real at all. The stock example of a conventionally real entity is the chariot, which we take to be real only because it is more convenient, given our interests and cognitive limitations, to have a single name for the parts when assembled in the right way. Since our belief that there are chariots is thus due to our having a certain useful concept, the chariot is said to be a mere conceptual fiction. (This does not, however, mean that all conceptualization is falsification; only concepts that allow of reductive analysis lead to this artificial inflation of our ontology, and thus to a kind of error.) Ultimately real entities are those ultimate parts into which conceptual fictions are analyzable. An ultimately true statement is one that correctly describes how certain ultimately real entities are arranged. A conventionally true statement is one that, given how the ultimately real entities are arranged, would correctly describe certain conceptual fictions if they also existed. The ultimate truth concerning the relevant ultimately real entities helps explain why it should turn out to be useful to accept conventionally true statements (such as ‘King Milinda rode in a chariot’) when the objects described in those statements are mere fictions.

Using this distinction between the two truths, the key insight of the ‘middle path’ may be expressed as follows. The ultimate truth about sentient beings is just that there is a causal series of impermanent, impersonal psychophysical elements. Since these are all impermanent, and lack other properties that would be required of an essence of the person, none of them is a self. But given the right arrangement of such entities in a causal series, it is useful to think of them as making up one thing, a person. It is thus conventionally true that there are persons, things that endure for a lifetime and possibly (if there is rebirth) longer. This is conventionally true because generally speaking there is more overall happiness and less overall pain and suffering when one part of such a series identifies with other parts of the same series. For instance, when the present set of psychophysical elements identifies with future elements, it is less likely to engage in behavior (such as smoking) that results in present pleasure but far greater future pain. The utility of this convention is, however, limited. Past a certain point—namely the point at which we take it too seriously, as more than just a useful fiction—it results in existential suffering. The cessation of suffering is attained by extirpating all sense of an ‘I’ that serves as agent and owner.

The Buddha’s ‘middle path’ strategy can be seen as one of first arguing that since the word ‘I’ is a mere enumerative term like ‘pair’, there is nothing that it genuinely denotes; and then explaining that our erroneous sense of an ‘I’ stems from our employment of the useful fiction represented by the concept of the person. While the second part of this strategy only receives its full articulation in the later development of the theory of two truths, the first part can be found in the Buddha’s own teachings, in the form of several philosophical arguments for non-self. Best known among these is the argument from impermanence (S III.66–8), which has this basic structure:

It is the fact that this argument does not contain a premise explicitly asserting that the five skandhas (classes of psychophysical element) are exhaustive of the constituents of persons, plus the fact that these are all said to be empirically observable, that leads some to claim that the Buddha did not intend to deny the existence of a self tout court . There is, however, evidence that the Buddha was generally hostile toward attempts to establish the existence of unobservable entities. In the Pohapāda Sutta (D I.178–203), for instance, the Buddha compares someone who posits an unseen seer in order to explain our introspective awareness of cognitions, to a man who has conceived a longing for the most beautiful woman in the world based solely on the thought that such a woman must surely exist. And in the Tevijja Sutta (D I.235–52), the Buddha rejects the claim of certain Brahmins to know the path to oneness with Brahman, on the grounds that no one has actually observed this Brahman. This makes more plausible the assumption that the argument has as an implicit premise the claim that there is no more to the person than the five skandhas .

Premise (1) appears to be based on the assumption that persons undergo rebirth, together with the thought that one function of a self would be to account for diachronic personal identity. By ‘permanent’ is here meant continued existence over at least several lives. This is shown by the fact that the Buddha rules out the body as a self on the grounds that the body exists for just one lifetime. (This also demonstrates that the Buddha did not mean by ‘impermanent’ what some later Buddhist philosophers meant, viz., existing for just a moment; the Buddhist doctrine of momentariness represents a later development.) The mental entities that make up the remaining four types of psychophysical element might seem like more promising candidates, but these are ruled out on the grounds that these all originate in dependence on contact between sense faculty and object, and last no longer than a particular sense-object-contact event. That he listed five kinds of psychophysical element, and not just one, shows that the Buddha embraced a kind of dualism. But this strategy for demonstrating the impermanence of the psychological elements shows that his dualism was not the sort of mind-body dualism familiar from substance ontologies like those of Descartes and of the Nyāya school of orthodox Indian philosophy. Instead of seeing the mind as the persisting bearer of such transient events as occurrences of cognition, feeling and volition, he treats ‘mind’ as a kind of aggregate term for bundles of transient mental events. These events being impermanent, they too fail to account for diachronic personal identity in the way in which a self might be expected to.

Another argument for non-self, which might be called the argument from control (S III.66–8), has this structure:

Premise (1) is puzzling. It appears to presuppose that the self should have complete control over itself, so that it would effortlessly adjust its state to its desires. That the self should be thought of as the locus of control is certainly plausible. Those Indian self-theorists who claim that the self is a mere passive witness recognize that the burden of proof is on them to show that the self is not an agent. But it seems implausibly demanding to require of the self that it have complete control over itself. We do not require that vision see itself if it is to see other things. The case of vision suggests an alternative interpretation, however. We might hold that vision does not see itself for the reason that this would violate an irreflexivity principle, to the effect that an entity cannot operate on itself. Indian philosophers who accept this principle cite supportive instances such as the knife that cannot cut itself and the finger-tip that cannot touch itself. If this principle is accepted, then if the self were the locus of control it would follow that it could never exercise this function on itself. A self that was the controller could never find itself in the position of seeking to change its state to one that it deemed more desirable. On this interpretation, the first premise seems to be true. And there is ample evidence that (2) is true: it is difficult to imagine a bodily or psychological state over which one might not wish to exercise control. Consequently, given the assumption that the person is wholly composed of the psychophysical elements, it appears to follow that a self of this description does not exist.

These two arguments appear, then, to give good reason to deny a self that might ground diachronic personal identity and serve as locus of control, given the assumption that there is no more to the person than the empirically given psychophysical elements. But it now becomes something of a puzzle how one is to explain diachronic personal identity and agency. To start with the latter, does the argument from control not suggest that control must be exercised by something other than the psychophysical elements? This was precisely the conclusion of the Sāṃkhya school of orthodox Indian philosophy. One of their arguments for the existence of a self was that it is possible to exercise control over all the empirically given constituents of the person; while they agree with the Buddha that a self is never observed, they take the phenomena of agency to be grounds for positing a self that transcends all possible experience.

This line of objection to the Buddha’s teaching of non-self is more commonly formulated in response to the argument from impermanence, however. Perhaps its most dramatic form is aimed at the Buddha’s acceptance of the doctrines of karma and rebirth. It is clear that the body ceases to exist at death. And given the Buddha’s argument that mental states all originate in dependence on sense-object contact events, it seems no psychological constituent of the person can transmigrate either. Yet the Buddha claims that persons who have not yet achieved enlightenment will be reborn as sentient beings of some sort after they die. If there is no constituent whatever that moves from one life to the next, how could the being in the next life be the same person as the being in this life? This question becomes all the more pointed when it is added that rebirth is governed by karma, something that functions as a kind of cosmic justice: those born into fortunate circumstances do so as a result of good deeds in prior lives, while unpleasant births result from evil past deeds. Such a system of reward and punishment could be just only if the recipient of pleasant or unpleasant karmic fruit is the same person as the agent of the good or evil action. And the opponent finds it incomprehensible how this could be so in the absence of a persisting self.

It is not just classical Indian self-theorists who have found this objection persuasive. Some Buddhists have as well. Among these Buddhists, however, this has led to the rejection not of non-self but of rebirth. (Historically this response was not unknown among East Asian Buddhists, and it is not rare among Western Buddhists today.) The evidence that the Buddha himself accepted rebirth and karma seems quite strong, however. The later tradition would distinguish between two types of discourse in the body of the Buddha’s teachings: those intended for an audience of householders seeking instruction from a sage, and those intended for an audience of monastic renunciates already versed in his teachings. And it would be one thing if his use of the concepts of karma and rebirth were limited to the former. For then such appeals could be explained away as another instance of the Buddha’s pedagogical skill (commonly referred to as upāya ). The idea would be that householders who fail to comply with the most basic demands of morality are not likely (for reasons to be discussed shortly) to make significant progress toward the cessation of suffering, and the teaching of karma and rebirth, even if not strictly speaking true, does give those who accept it a (prudential) reason to be moral. But this sort of ‘noble lie’ justification for the Buddha teaching a doctrine he does not accept fails in the face of the evidence that he also taught it to quite advanced monastics (e.g., A III.33). And what he taught is not the version of karma popular in certain circles today, according to which, for instance, an act done out of hatred makes the agent somewhat more disposed to perform similar actions out of similar motives in the future, which in turn makes negative experiences more likely for the agent. What the Buddha teaches is instead the far stricter view that each action has its own specific consequence for the agent, the hedonic nature of which is determined in accordance with causal laws and in such a way as to require rebirth as long as action continues. So if there is a conflict between the doctrine of non-self and the teaching of karma and rebirth, it is not to be resolved by weakening the Buddha’s commitment to the latter.

The Sanskrit term karma literally means ‘action’. What is nowadays referred to somewhat loosely as the theory of karma is, speaking more strictly, the view that there is a causal relationship between action ( karma ) and ‘fruit’ ( phala ), the latter being an experience of pleasure, pain or indifference for the agent of the action. This is the view that the Buddha appears to have accepted in its most straightforward form. Actions are said to be of three types: bodily, verbal and mental. The Buddha insists, however, that by action is meant not the movement or change involved, but rather the volition or intention that brought about the change. As Gombrich (2009) points out, the Buddha’s insistence on this point reflects the transition from an earlier ritualistic view of action to a view that brings action within the purview of ethics. For it is when actions are seen as subject to moral assessment that intention becomes relevant. One does not, for instance, perform the morally blameworthy action of speaking insultingly to an elder just by making sounds that approximate to the pronunciation of profanities in the presence of an elder; parrots and prelinguistic children can do as much. What matters for moral assessment is the mental state (if any) that produced the bodily, verbal or mental change. And it is the occurrence of these mental states that is said to cause the subsequent occurrence of hedonically good, bad and neutral experiences. More specifically, it is the occurrence of the three ‘defiled’ mental states that brings about karmic fruit. The three defilements ( kleśa s) are desire, aversion and ignorance. And we are told quite specifically (A III.33) that actions performed by an agent in whom these three defilements have been destroyed do not have karmic consequences; such an agent is experiencing their last birth.

Some caution is required in understanding this claim about the defilements. The Buddha seems to be saying that it is possible to act not only without ignorance, but also in the absence of desire or aversion, yet it is difficult to see how there could be intentional action without some positive or negative motivation. To see one’s way around this difficulty, one must realize that by ‘desire’ and ‘aversion’ are meant those positive and negative motives respectively that are colored by ignorance, viz. ignorance concerning suffering, impermanence and non-self. Presumably the enlightened person, while knowing the truth about these matters, can still engage in motivated action. Their actions are not based on the presupposition that there is an ‘I’ for which those actions can have significance. Ignorance concerning these matters perpetuates rebirth, and thus further occasions for existential suffering, by facilitating a motivational structure that reinforces one’s ignorance. We can now see how compliance with common-sense morality could be seen as an initial step on the path to the cessation of suffering. While the presence of ignorance makes all action—even that deemed morally good—karmically potent, those actions commonly considered morally evil are especially powerful reinforcers of ignorance, in that they stem from the assumption that the agent’s welfare is of paramount importance. While recognition of the moral value of others may still involve the conceit that there is an ‘I’, it can nonetheless constitute progress toward dissolution of the sense of self.

This excursus into what the Buddha meant by karma may help us see how his middle path strategy could be used to reply to the objection to non-self from rebirth. That objection was that the reward and punishment generated by karma across lives could never be deserved in the absence of a transmigrating self. The middle path strategy generally involves locating and rejecting an assumption shared by a pair of extreme views. In this case the views will be (1) that the person in the later life deserves the fruit generated by the action in the earlier life, and (2) that this person does not deserve the fruit. One assumption shared by (1) and (2) is that persons deserve reward and punishment depending on the moral character of their actions, and one might deny this assumption. But that would be tantamount to moral nihilism, and a middle path is said to avoid nihilisms (such as annihilationism). A more promising alternative might be to deny that there are ultimately such things as persons that could bear moral properties like desert. This is what the Buddha seems to mean when he asserts that the earlier and the later person are neither the same nor different (S II.62; S II.76; S II.113). Since any two existing things must be either identical or distinct, to say of the two persons that they are neither is to say that strictly speaking they do not exist.

This alternative is more promising because it avoids moral nihilism. For it allows one to assert that persons and their moral properties are conventionally real. To say this is to say that given our interests and cognitive limitations, we do better at achieving our aim—minimizing overall pain and suffering—by acting as though there are persons with morally significant properties. Ultimately there are just impersonal entities and events in causal sequence: ignorance, the sorts of desires that ignorance facilitates, an intention formed on the basis of such a desire, a bodily, verbal or mental action, a feeling of pleasure, pain or indifference, and an occasion of suffering. The claim is that this situation is usefully thought of as, for instance, a person who performs an evil deed due to their ignorance of the true nature of things, receives the unpleasant fruit they deserve in the next life, and suffers through their continuing on the wheel of saṃsāra. It is useful to think of the situation in this way because it helps us locate the appropriate places to intervene to prevent future pain (the evil deed) and future suffering (ignorance).

It is no doubt quite difficult to believe that karma and rebirth exist in the form that the Buddha claims. It is said that their existence can be confirmed by those who have developed the power of retrocognition through advanced yogic technique. But this is of little help to those not already convinced that meditation is a reliable means of knowledge. What can be said with some assurance is that karma and rebirth are not inconsistent with non-self. Rebirth without transmigration is logically possible.

When the Buddha says that a person in one life and the person in another life are neither the same nor different, one’s first response might be to take ‘different’ to mean something other than ‘not the same’. But while this is possible in English given the ambiguity of ‘the same’, it is not possible in the Pāli source, where the Buddha is represented as unambiguously denying both numerical identity and numerical distinctness. This has led some to wonder whether the Buddha does not employ a deviant logic. Such suspicions are strengthened by those cases where the options are not two but four, cases of the so-called tetralemma ( catuṣkoṭi ). For instance, when the Buddha is questioned about the post-mortem status of the enlightened person or arhat (e.g., at M I.483–8) the possibilities are listed as: (1) the arhat continues to exist after death, (2) does not exist after death, (3) both exists and does not exist after death, and (4) neither exists nor does not exist after death. When the Buddha rejects both (1) and (2) we get a repetition of ‘neither the same nor different’. But when he goes on to entertain, and then reject, (3) and (4) the logical difficulties are compounded. Since each of (3) and (4) appears to be formally contradictory, to entertain either is to entertain the possibility that a contradiction might be true. And their denial seems tantamount to affirmation of excluded middle, which is prima facie incompatible with the denial of both (1) and (2). One might wonder whether we are here in the presence of the mystical.

There were some Buddhist philosophers who took ‘neither the same nor different’ in this way. These were the Personalists ( Pudgalavādins ), who were so called because they affirmed the ultimate existence of the person as something named and conceptualized in dependence on the psychophysical elements. They claimed that the person is neither identical with nor distinct from the psychophysical elements. They were prepared to accept, as a consequence, that nothing whatever can be said about the relation between person and elements. But their view was rejected by most Buddhist philosophers, in part on the grounds that it quickly leads to an ineffability paradox: one can say neither that the person’s relation to the elements is inexpressible, nor that it is not inexpressible. The consensus view was instead that the fact that the person can be said to be neither identical with nor distinct from the elements is grounds for taking the person to be a mere conceptual fiction. Concerning the persons in the two lives, they understood the negations involved in ‘neither the same nor different’ to be of the commitmentless variety, i.e., to function like illocutionary negation. If we agree that the statement ‘7 is green’ is semantically ill-formed, on the grounds that abstract objects such as numbers do not have colors, then we might go on to say, ‘Do not say that 7 is green, and do not say that it is not green either’. There is no contradiction here, since the illocutionary negation operator ‘do not say’ generates no commitment to an alternative characterization.

There is also evidence that claims of type (3) involve parameterization. For instance, the claim about the arhat would be that there is some respect in which they can be said to exist after death, and some other respect in which they can be said to no longer exist after death. Entertaining such a proposition does not require that one believe there might be true contradictions. And while claims of type (4) would seem to be logically equivalent to those of type (3) (regardless of whether or not they involve parameterization), the tradition treated this type as asserting that the subject is beyond all conceptualization. To reject the type (4) claim about the arhat is to close off one natural response to the rejections of the first three claims: that the status of the arhat after death transcends rational understanding. That the Buddha rejected all four possibilities concerning this and related questions is not evidence that he employed a deviant logic.

The Buddha’s response to questions like those concerning the arhat is sometimes cited in defense of a different claim about his attitude toward rationality. This is the claim that the Buddha was essentially a pragmatist, someone who rejects philosophical theorizing for its own sake and employs philosophical rationality only to the extent that doing so can help solve the practical problem of eliminating suffering. The Buddha does seem to be embracing something like this attitude when he defends his refusal to answer questions like that about the arhat , or whether the series of lives has a beginning, or whether the living principle ( jīva ) is identical with the body. He calls all the possible views with respect to such questions distractions insofar as answering them would not lead to the cessation of the defilements and thus to the end of suffering. And in a famous simile (M I.429) he compares someone who insists that the Buddha answer these questions to someone who has been wounded by an arrow but will not have the wound treated until they are told who shot the arrow, what sort of wood the arrow is made of, and the like.

Passages such as these surely attest to the great importance the Buddha placed on sharing his insights to help others overcome suffering. But this is consistent with the belief that philosophical rationality may be used to answer questions that lack evident connection with pressing practical concerns. And on at least one occasion the Buddha does just this. Pressed to give his answers to the questions about the arhat and the like, the Buddha first rejects all the possibilities of the tetralemma, and defends his refusal on the grounds that such theories are not conducive to liberation from saṃsāra . But when his questioner shows signs of thereby losing confidence in the value of the Buddha’s teachings about the path to the cessation of suffering, the Buddha responds with the example of a fire that goes out after exhausting its fuel. If one were asked where this fire has gone, the Buddha points out, one could consistently deny that it has gone to the north, to the south, or in any other direction. This is so for the simple reason that the questions ‘Has it gone to the north?’, ‘Has it gone to the south?’, etc., all share the false presupposition that the fire continues to exist. Likewise the questions about the arhat and the like all share the false presupposition that there is such a thing as a person who might either continue to exist after death, cease to exist at death, etc. (Anālayo 2018, 41) The difficulty with these questions is not that they try to extend philosophical rationality beyond its legitimate domain, as the handmaiden of soteriologically useful practice. It is rather that they rest on a false presupposition—something that is disclosed through the employment of philosophical rationality.

A different sort of challenge to the claim that the Buddha valued philosophical rationality for its own sake comes from the role played by authority in Buddhist soteriology. For instance, in the Buddhist tradition one sometimes encounters the claim that only enlightened persons such as the Buddha can know all the details of karmic causation. And to the extent that the moral rules are thought to be determined by the details of karmic causation, this might be taken to mean that our knowledge of the moral rules is dependent on the authority of the Buddha. Again, the subsequent development of Buddhist philosophy seems to have been constrained by the need to make theory compatible with certain key claims of the Buddha. For instance, one school developed an elaborate form of four-dimensionalism, not because of any deep dissatisfaction with presentism, but because they believed the non-existence of the past and the future to be incompatible with the Buddha’s alleged ability to cognize past and future events. And some modern scholars go so far as to wonder whether non-self functions as anything more than a sort of linguistic taboo against the use of words like ‘I’ and ‘self’ in the Buddhist tradition (Collins 1982: 183). The suggestion is that just as in some other religious traditions the views of the founder or the statements of scripture trump all other considerations, including any views arrived at through the free exercise of rational inquiry, so in Buddhism as well there can be at best only a highly constrained arena for the deployment of philosophical rationality.

Now it could be that while this is true of the tradition that developed out of the Buddha’s teachings, the Buddha himself held the unfettered use of rationality in quite high esteem. This would seem to conflict with what he is represented as saying in response to the report that he arrived at his conclusions through reasoning and analysis alone: that such a report is libelous, since he possesses a number of superhuman cognitive powers (M I.68). But at least some scholars take this passage to be not the Buddha’s own words but an expression of later devotionalist concerns (Gombrich 2009: 164). Indeed one does find a spirited discussion within the tradition concerning the question whether the Buddha is omniscient, a discussion that may well reflect competition between Buddhism and those Brahmanical schools that posit an omniscient creator. And at least for the most part the Buddhist tradition is careful not to attribute to the Buddha the sort of omniscience usually ascribed to an all-perfect being: the actual cognition, at any one time, of all truths. Instead a Buddha is said to be omniscient only in the much weaker sense of always having the ability to cognize any individual fact relevant to the soteriological project, viz. the details of their own past lives, the workings of the karmic causal laws, and whether a given individual’s defilements have been extirpated. Moreover, these abilities are said to be ones that a Buddha acquires through a specific course of training, and thus ones that others may reasonably aspire to as well. The attitude of the later tradition seems to be that while one could discover the relevant facts on one’s own, it would be more reasonable to take advantage of the fact that the Buddha has already done all the epistemic labor involved. When we arrive in a new town we could always find our final destination through trial and error, but it would make more sense to ask someone who already knows their way about.

The Buddhist philosophical tradition grew out of earlier efforts to systematize the Buddha’s teachings. Within a century or two of the death of the Buddha, exegetical differences led to debates concerning the Buddha’s true intention on some matter, such as that between the Personalists and others over the status of the person. While the parties to these debates use many of the standard tools and techniques of philosophy, they were still circumscribed by the assumption that the Buddha’s views on the matter at hand are authoritative. In time, however, the discussion widened to include interlocutors representing various Brahmanical systems. Since the latter did not take the Buddha’s word as authoritative, Buddhist thinkers were required to defend their positions in other ways. The resulting debate (which continued for about nine centuries) touched on most of the topics now considered standard in metaphysics, epistemology and philosophy of language, and was characterized by considerable sophistication in philosophical methodology. What the Buddha would have thought of these developments we cannot say with any certainty. What we can say is that many Buddhists have believed that the unfettered exercise of philosophical rationality is quite consistent with his teachings.

- Albahari, Miri, 2006, Analytical Buddhism , Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- –––, 2014, ‘Insight Knowledge of No Self in Buddhism: An Epistemic Analysis,’ Philosophers’ Imprint , 14(1), available online .

- Anālayo, Bhikkhu, 2018, Rebirth in Early Buddhism and Current research , Cambridge, MA: Wisdom.

- Collins, Stephen, 1982, Selfless Persons , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cousins, L. S., 2022, Meditations of the Pali Tradition: Illuminating Buddhist Doctrine, History, and Practice, edited by Sarah Shaw, Boulder, CO: Shambala.

- Gethin, Rupert, 1998, The Foun dations of Buddhism , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gombrich, Richard F., 1996, How Buddhism Began , London: Athlone.

- –––, 2009, What the Buddha Thought , London: Equinox.

- Gowans, Christopher, 2003, Philosophy of the Buddha , London: Routledge.

- Harvey, Peter, 1995, The Selfless Mind , Richmond, UK: Curzon.

- Jayatilleke, K.N., 1963, Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge , London: George Allen and Unwin.

- Rahula, Walpola, 1967, What the Buddha Taught , 2 nd ed., London: Unwin.

- Ronkin, Noa, 2005, Early Buddhist Metaphysics , London: Routledge.

- Ruegg, David Seyfort, 1977, ‘The Uses of the Four Positions of the Catuṣkoṭi and the Problem of the Description of Reality in Mahāyāna Buddhism,’ Journal of Indian Philosophy , 5: 1–71.

- Siderits, Mark, 2021, Buddhism As Philosophy , 2nd edition, Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Smith, Douglass and Justin Whitaker, 2016, ‘Reading the Buddha as a Philosopher,’ Philosophy East and West , 66: 515–538.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

- The Pali Tipitaka , Pali texts

- Ten Philosophical Questions to Ask About Buddhism , a series of talks by Richard P. Hayes

- Access to Insight , Readings in Theravada Buddhism

- Buddhanet , Buddha Dharma Education Association

Abhidharma | Chinese Philosophy: Chan Buddhism | Chinese Philosophy: Huayan Buddhism | Chinese Philosophy: Tiantai Buddhism | ethics: in Indian Buddhism | Japanese Philosophy: Pure Land | Japanese Philosophy: Zen Buddhism | -->Korean Philosophy: Buddhism --> | Madhyamaka | Nāgārjuna | two truths in India, theory of | two truths in Tibet, theory of | -->yogaacaara -->

Copyright © 2023 by Mark Siderits < msideri @ ilstu . edu >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

- Gautama Buddha

Gautama Buddha , also known as Shakyamuni Buddha , or simply the Buddha , was an Indian sage on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. He is believed to have lived and taught in northeastern India sometime between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE. [1]

When referring to the period before he became enlightened, the Buddha is known as Siddhārtha Gautama ( Sanskrit ) or Siddhattha Gotama ( Pali ). Siddhartha , his given name, means "one who achieves his goals"; Gautama is his family name.

Gautama Buddha is believed by Buddhists to have been a fully awakened being who taught the true path to the cessation of suffering ( dukkha ) and the attainment of liberation ( nirvana ). Accounts of his life, discourses and monastic rules are believed by Buddhists to have been summarized after his death and memorized by his followers. Various collections of teachings attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition and first committed to writing about 400 years after his death.

- 1.1 Influences

- 1.2 Birth and death

- 1.3 Shakya clan

- 1.4 Birthplace

- 1.5 Travels and teaching

- 1.6 Written records

- 2.2 Life in the palace

- 2.3 The four sights

- 2.4 Renunciation

- 2.5 Spiritual quest

- 2.6 Enlightenment

- 2.7 First teaching

- 2.8 The first sangha

- 2.9 Return to Kapilavastu to teach his family

- 2.10 Mahaparinirvana

- 3 Traditional biographical sources

- 4 Meaning of "Buddha"

- 6 Physical characteristics

- 8 References

- 9.1 Printed sources

- 9.2 Online souces

- 10.1 The Buddha

- 10.2 Early Buddhism

- 10.3 Buddhism general

- 11 External links

Historical Siddhārtha Gautama

Scholars are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical facts of the Buddha's life. Most accept that he lived, taught and founded a monastic order, but do not accept many of the details contained in traditional biographies. [2] [3]

According to author Michael Carrithers, while there are good reasons to doubt the traditional account, "the outline of the life must be true: birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death." [4] In her biography of the Buddha, Karen Armstrong writes,

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhārtha was born in a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the northeastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE. [6]

The Buddha was born into the Shakya clan, which historians believe to have been organized into either an oligarchy or a republic. Historians suggest that Siddhartha's father was likely an important figure in the republic or oligarchy, rather than a "king" as described in the traditional biographies. [6]

Most scholars accept that he lived, taught and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada era in India during the reign of Bimbisara , the ruler of the Magadha empire, and died during the early years of the reign of Ajatshatru who was the successor of Bimbisara, thus making him a younger contemporary of Mahavira , the Jain teacher. [7] [8]

Apart from the Vedic Brahmins , the Buddha's lifetime coincided with the flourishing of other influential sramana schools of thoughts like Ājīvika , Cārvāka , Jain , and Ajñana. It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahāvīra , Pūraṇa Kassapa , Makkhali Gosāla , Ajita Kesakambalī , Pakudha Kaccāyana , and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta , whose viewpoints the Buddha most certainly must have been acquainted with and influenced by. [9] [10] [note 1] Indeed, Sariputta and Maudgalyāyana , two of the foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the skeptic. [11] There is also evidence to suggest that the two masters, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta , were indeed historical figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of meditative techniques. [12]

Birth and death

The times of Gautama's birth and death are uncertain. Most historians in the early 20th century dated his lifetime as circa 563 BCE to 483 BCE. [13] [14] More recently his death is dated later, between 411 and 400 BCE, while at a symposium on this question held in 1988, [15] [16] [17] the majority of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha's death. [13] [18] [note 3] These alternative chronologies, however, have not yet been accepted by all historians. [24] [25] [note 5]

According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini , nowadays in modern-day Nepal , and raised in Kapilavastu (Shakya capital), which may either be in present day Tilaurakot , Nepal or Piprahwa , India. [note 2]

Shakya clan

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhārtha Gautama was born into the Shakya clan, a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the northeastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE. [6] According to Gombrich, they seem to have had no cast system, but did have servants.

Gombrich states, "Some historians call [Shakya] an oligarchy, some a republic; certainly it was not a brahminical monarchy, and makes more than dubious the later story that the future Buddha’s father was the local king." [33] In this view, Siddhartha's father was more likely an important figure in the republic or oligarchy, rather than a traditional monarch.

Historians believe that the Shakyas were self governing and heads of housholds met in council to discuss problems and reach unanimous decisions. According to Gombrich, this gave the Buddha a model of a castless society; in the Sangha he instituted rank based on seniority counted from ordination. [6]

The Buddhist tradition regards Lumbini , present-day Nepal, to be the birthplace of the Buddha. [34] [note 2] According to tradition, he grew up in Kapilavastu . [note 2] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown. It may have been either Piprahwa , Uttar Pradesh , present-day India, [31] or Tilaurakot , present-day Nepal. [35] Both places belonged to the Sakya territory, and are located only 15 miles apart from each other. [35]

Siddharta Gautama was born as a Kshatriya , [36] [note 7] the son of Śuddhodana , "an elected chief of the Shakya clan ", [1] whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha's lifetime. Gautama was the family name . His mother, Queen Maha Maya (Māyādevī) was a Koliyan princess.

Travels and teaching

The Buddha spent about 45 years of his life teaching the dharma. He is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain , in what is now Uttar Pradesh , Bihar and southern Nepal , teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to servants, murderers such as Angulimala , and cannibals such as Alavaka. [38] Although the Buddha's language remains unknown, it's likely that he taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, of which Pali may be a standardization.

The sangha, the Buddha's disciples, would travel throughout the subcontinent, expounding the dharma.

Written records

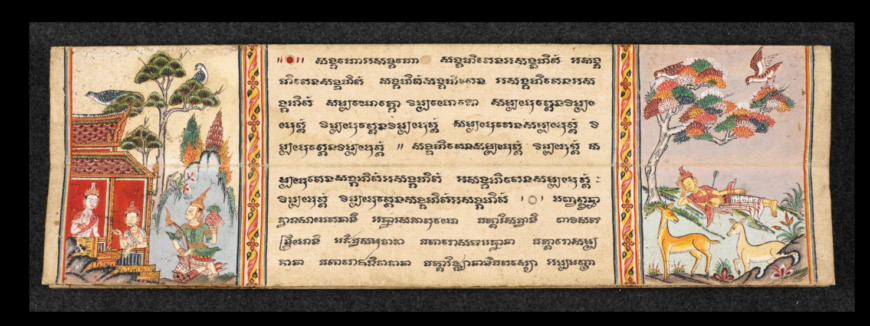

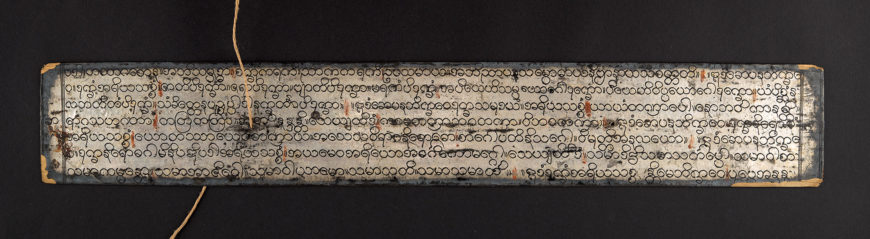

No written records about Gautama have been found from his lifetime or some centuries thereafter. One edict of Emperor Ashoka , who reigned from circa 269 BCE to 232 BCE, commemorates the Emperor's pilgrimage to the Buddha's birthplace in Lumbini . Another one of his edict mentions several Dhamma texts, establishing the existence of a written Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Mauryan era and which may be the precursors of the Pāli Canon . [39] [note 8] The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist texts , reported to have been found in or around Haḍḍa near Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan and now preserved in the British Library . They are written in the Kharoṣṭhī script and the Gāndhārī language on twenty-seven birch bark scrolls , and they date from the first century BCE to the third century CE. [web 8]

Traditional life story

There are multiple accounts of the life of the Buddha within Buddhist literature. These accounts generally agree on the broad outlines of his life story, though there are differences in detail and interpretation. [40]

Alexander Berzin states:

The account below follows the broad outline of Buddha's life, according to traditional sources.

Gautama Buddha's parents were King Śuddhodana and Queen Maya , who were the rulers of the Shakya kingdom of Northern India. His given name was Siddhartha.

The King and Queen lived in the Shakya capital of Kapilavastu . Following the traditional custom of the time, when Queen Maya knew the time of her son's birth was drawing near, she began to travel to her father's home in Kapilavastu , in order to give birth to the child there. However, the queen was unable to reach her destination before giving birth, and her son was born in a garden beneath a sal tree in the region of Lumbini (in present-day Nepal).

Siddhartha's mother, Queen Maya died soon after giving birth. Siddhartha would be raised by his father, King Śuddhodana, and his mother's younger sister, Maha Pajapati .

Life in the palace

Siddhartha's father, King Śuddhodana , gave him the name Siddhartha , meaning "one who achieves his goals".

Soon after the birth of Siddhartha, Śuddhodana invited a group of eight brahmin sages to his court to examine the child and predict his future. The sages prophesied that Siddhartha would either become a great king and military conqueror ( chakravartin ) or an enlightened spiritual guide ( buddha ).

Śuddhodana was eager for his son to become a great king and conqueror. But he was concerned that Siddhartha might choose the spiritual path and renounce his worldly inheritance.

Thus, as a young man, Siddhartha wore robes of the finest silk, ate the best food and was surrounded by beautiful dancing girls. He was extremely handsome and he excelled at his studies and at every type of sporting contest. His father arranged for him to marry a young woman of exceptional grace and beauty, Yasodhara . Siddhartha and Yasodhara lived together in peace and harmony for many years, and they had a son together.

Yet despite all of this, Siddhartha still had not yet been outside the palace walls. His curiosity grew stronger and stronger and he pleaded with his father to allow him to venture beyond the palace gates. Finally, when Siddhartha reached the age of 29, his father relented and allowed him to visit the world outside the palace gates.

The four sights

Siddhartha ventured beyond the gates with his faithful charioteer Channa and they had a series of encounters known as the four sights . In these encounters, Siddhartha and Channa first encountered an old man, then a sick man, and then a corpse. From these three encounters Siddhartha began to understand the nature of suffering in the world. Finally, they met an ascetic holy man ( śramaṇa ), who appeared to be content and at peace with the world.

These encounters had a profound impact on Siddhartha. Through the first three sights, Siddhartha came to understand that despite the luxury of his surroundings, and despite the immense wealth and power of his family, both he himself and everyone he loved would eventually have to face the sufferings of old age, sickness and death. And he was powerless to stop this. Siddhartha was also inspired by the holy man who was seeking a path beyond suffering, and Siddhartha resolved that he too would seek that path in order that he could lead his family beyond suffering.

Renunciation

Siddhartha made the decision to renounce his worldly life and follow the path of an ascetic spiritual seeker. According to one account, late one night, after the rest of the household had gone to sleep, Siddhartha ordered Channa the charioteer to prepare his horse, and together they slipped unnoticed outside the palace gates. They rode to the edge of a nearby forest, and once there, Siddhartha informed Channa that he was renouncing his worldly life to become a seeker of truth. As a sign of his renunciation, Siddhartha cut off his long, beautiful hair and discarded his royal robes. Siddhartha instructed Channa to return to the palace and inform his father of his decision, and then he walked off into the forest.

Spiritual quest

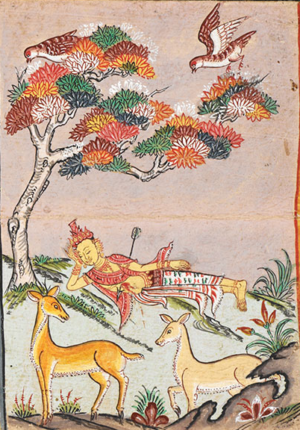

After renouncing his worldly life, Siddhartha sought out the great spiritual teachers of his day. He studied with several teachers, and in each case, he mastered the meditative techniques which they taught. But he found that the meditation techniques that he learned from these teachers did not provide a permanent end to suffering, so he continued his quest. He next joined a group of five other ascetics ( śramaṇa ), led by a holy man named Kondañña . For the next several years, Siddhartha practiced extreme austerities along with his five companions. These austerities included prolonged fasting, breath-holding, and exposure to pain. He almost starved himself to death in the process.

Eventually Siddhartha realized that he had taken this kind of practice to its limit, and had not put an end to suffering. In a pivotal moment, as he was near death, Siddhartha accepted milk and rice from a village girl and began to regain his strength. He then devoted himself to meditation, taking in the nourishment that he needed, but not more than that. He would later describe his new approach as the Middle Way : a path of moderation between the extremes of self-indulgence and self-denial.

Enlightenment

At the age of 35, Siddhartha sat in meditation under a fig tree — now known as the Bodhi tree — and he vowed not to rise before achieving enlightenment ( bodhi ). After many days, he finally destroyed the fetters of his mind, thereby liberating himself from the cycle of suffering and rebirth ( saṃsāra ), and arose as a fully enlightened being ( samyaksambuddha ).

According to some accounts, after his awakening, the Buddha debated with himself whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others. [note 9] He was concerned that humans were so overpowered by ignorance ( avidya ), greed ( raga ) and hatred ( dvesha ) that they would not understand his dharma, which is subtle, deep and difficult to grasp. However, while he was contemplating this, he was approached by a being from the heavenly realms ( Brahma Sahampati ), who urged the Buddha to teach, arguing that at least some people will understand the dharma. The Buddha relented, and agreed to teach.

First teaching

After a period of deep reflection, the Buddha sought out his five former companions (with whom he had practiced austerities). He found them in a deer park in Sarnath , northern India.

There he gave his first teaching to his former companions, in which he explained his middle way approach and the four noble truths . Traditionally, it is said the Buddha "set in motion the Wheel of Dharma " when he gave this first teaching; this teaching is recorded in The Discourse That Sets Turning the Wheel of Truth ( Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta ).

The Buddha spent the rest of his life traveling throughout northeastern India and teaching the path of awakening he had discovered.

The first sangha

The Buddha along with his first five followers are said to have formed the first saṅgha : the company of Buddhist monks. As the Buddha traveled and continued teaching, he attracted many more followers, many of whom became monks and nuns, and many who became lay followers.

Return to Kapilavastu to teach his family

Upon hearing of Siddhartha's awakening, his father King Śuddhodana sent many requests to ask the Buddha to return to Kapilavastu. Two years after his awakening, the Buddha agreed to return to Kapilavastu, and made a two-month journey by foot, teaching the dharma as he went. When he reached his father's home in Kapilavastu, he taught the dharma to his father and his extended family. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha . The Buddha's cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arhat.

Of the Buddha's disciples, Sariputta, Maudgalyayana , Mahakasyapa , Ananda and Anuruddha are believed to have been the five closest to him.

Mahaparinirvana

At the age of 80, the Buddha fell ill in the town of Kushinagar in northern India. At this time, he said to his attendant Ananda :

When Ananda become despondent, the Buddha said to him:

The Buddha then passed away. He death is considered to be a parinirvana , a complete release from the cycle of existence ( samsara ).

The Buddha's body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present.

Traditional biographical sources

There are multiple accounts of the life of the Buddha within Buddhist literature. These accounts generally agree on the broad outlines of his life story, though there are differences in detail and interpretation. [40] The sources for these accounts include:

- Buddhacarita ,

- Lalitavistara Sūtra ,

- Mahāvastu , and

- Nidānakathā . [44]

Of these, the Buddhacarita [45] [46] [47] is considered to be the earliest full biography. This text is an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa , and dating around the beginning of the 2nd century CE. [44]

The Lalitavistara Sūtra is thought to be the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna / Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE. [48]

The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE. [48]

The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra , [49] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE.

Lastly, the Nidānakathā is from the Theravāda tradition in Sri Lanka and was composed in the 5th century CE by Buddhaghoṣa . [50]

Additional sources from the Pali Canon include the Jātakas , the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123) which include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jātakas retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva , and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts. [51] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama's birth, such as the bodhisattva's descent from Tuṣita Heaven into his mother's womb.

Meaning of "Buddha"

The word Buddha means "awakened one" or "the enlightened one". "Buddha" is also used as a title for the first awakened being in an era . In most Buddhist traditions, Siddhartha Gautama is regarded as the Supreme Buddha ( Pali sammāsambuddha , Sanskrit samyaksaṃbuddha ) of our age. [note 10]

After his death, Buddha's cremation relics were divided amongst 8 royal families and his disciples; centuries later they would be enshrined by King Ashoka into 84,000 stupas. [web 9] [52] [53]

Physical characteristics

Traditionally, the Buddha's physical body is said to possess:

- Mahapurusalaksana - thirty-two major marks of a great man

- Minor marks of a great person - eighty minor marks

Within Buddhist cosmology , these physical marks are shared by both buddhas and chakravartins . However the marks are more clear and distinct on the body of a buddha. The Buddha also has a few marks that are not found on the chakravartin, such as the protuberance on the crown of the Buddha's head. [54]

- ↑ According to Alexander Berzin, "Buddhism developed as a shramana school that accepted rebirth under the force of karma, while rejecting the existence of the type of soul that other schools asserted. In addition, the Buddha accepted as parts of the path to liberation the use of logic and reasoning, as well as ethical behavior, but not to the degree of Jain asceticism. In this way, Buddhism avoided the extremes of the previous four shramana schools." [web 1]

- Warder: "The Buddha [...] was born in the Sakya Republic, which was the city state of Kapilavastu, a very small state just inside the modern state boundary of Nepal against the Northern Indian frontier. [1]

- Walsh: "He belonged to the Sakya clan dwelling on the edge of the Himalayas, his actual birthplace being a few miles north of the present-day Northern Indian border, in Nepal. His father was in fact an elected chief of the clan rather than the king he was later made out to be, though his title was raja – a term which only partly corresponds to our word 'king'. Some of the states of North India at that time were kingdoms and others republics, and the Sakyan republic was subject to the powerful king of neighbouring Kosala, which lay to the south". [30] The exact location of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown. [28] It may have been either Piprahwa in Uttar Pradesh , northern India, [31] [28] or Tilaurakot , present-day Nepal . [32] [28] The two cities are located only fifteen miles from each other. [32]