Understanding Creativity

- Posted June 25, 2020

- By Emily Boudreau

Understanding the learning that happens with creative work can often be elusive in any K–12 subject. A new study from Harvard Graduate School of Education Associate Professor Karen Brennan , and researchers Paulina Haduong and Emily Veno, compiles case studies, interviews, and assessment artifacts from 80 computer science teachers across the K–12 space. These data shed new light on how teachers tackle this challenge in an emerging subject area.

“A common refrain we were hearing from teachers was, ‘We’re really excited about doing creative work in the classroom but we’re uncertain about how to assess what kids are learning, and that makes it hard for us to do what we want to do,’” Brennan says. “We wanted to learn from teachers who are supporting and assessing creativity in the classroom, and amplify their work, and celebrate it and show what’s possible as a way of helping other teachers.”

Create a culture that values meaningful assessment for learning — not just grades

As many schools and districts decided to suspend letter grades during the pandemic, teachers need to help students find intrinsic motivation. “It’s a great moment to ask, ‘What would assessment look like without a focus on grades and competition?’” says Veno.

Indeed, the practice of fostering a classroom culture that celebrates student voice, creativity, and exploration isn’t limited to computer science. The practice of being a creative agent in the world extends through all subject areas.

The research team suggests the following principles from computer science classrooms may help shape assessment culture across grade levels and subject areas.

Solicit different kinds of feedback

Give students the time and space to receive and incorporate feedback. “One thing that’s been highlighted in assessment work is that it is not about the teacher talking to a student in a vacuum,” says Haduong, noting that hearing from peers and outside audience members can help students find meaning and direction as they move forward with their projects.

- Feedback rubrics help students receive targeted feedback from audience members. Additionally, looking at the rubrics can help the teacher gather data on student work.

Emphasize the process for teachers and students

Finding the appropriate rubric or creating effective project scaffolding is a journey. Indeed, according to Haduong, “we found that many educators had a deep commitment to iteration in their own work.” Successful assessment practices conveyed that spirit to students.

- Keeping design journals can help students see their work as it progresses and provides documentation for teachers on the student’s process.

- Consider the message sent by the form and aesthetics of rubrics. One educator decided to use a handwritten assessment to convey that teachers, too, are working on refining their practice.

Scaffold independence

Students need to be able to take ownership of their learning as virtual learning lessens teacher oversight. Students need to look at their own work critically and know when they’ve done their best. Teachers need to guide students in this process and provide scaffolded opportunities for reflection.

- Have students design their own assessment rubric. Students then develop their own continuum to help independently set expectations for themselves and their work.

Key Takeaways

- Assessment shouldn’t be limited to the grade a student receives at the end of the semester or a final exam. Rather, it should be part of the classroom culture and it should be continuous, with an emphasis on using assessment not for accountability or extrinsic motivation, but to support student learning.

- Teachers can help learners see that learning and teaching are iterative processes by being more transparent about their own efforts to reflect and iterate on their practices.

- Teachers should scaffold opportunities for students to evaluate their own work and develop independence.

Additional Resources

- Creative Computing curriculum and projects

- Karen Brennan on helping kids get “unstuck”

- Usable Knowledge on how assessment can help continue the learning process

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Strategies for Leveling the Educational Playing Field

New research on SAT/ACT test scores reveals stark inequalities in academic achievement based on wealth

How to Help Kids Become Skilled Citizens

Active citizenship requires a broad set of skills, new study finds

Student Testing, Accountability, and COVID

What creativity really is - and why schools need it

Associate Professor of Psychology and Creative Studies, University of British Columbia

Disclosure statement

Liane Gabora's research is supported by a grant (62R06523) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

University of British Columbia provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Although educators claim to value creativity , they don’t always prioritize it.

Teachers often have biases against creative students , fearing that creativity in the classroom will be disruptive. They devalue creative personality attributes such as risk taking, impulsivity and independence. They inhibit creativity by focusing on the reproduction of knowledge and obedience in class.

Why the disconnect between educators’ official stance toward creativity, and what actually happens in school?

How can teachers nurture creativity in the classroom in an era of rapid technological change, when human innovation is needed more than ever and children are more distracted and hyper-stimulated ?

These are some of the questions we ask in my research lab at the Okanagan campus of the University of British Columbia. We study the creative process , as well as how ideas evolve over time and across societies. I’ve written almost 200 scholarly papers and book chapters on creativity, and lectured on it worldwide. My research involves both computational models and studies with human participants. I also write fiction, compose music for the piano and do freestyle dance.

What is creativity?

Although creativity is often defined in terms of new and useful products, I believe it makes more sense to define it in terms of processes. Specifically, creativity involves cognitive processes that transform one’s understanding of, or relationship to, the world.

There may be adaptive value to the seemingly mixed messages that teachers send about creativity. Creativity is the novelty-generating component of cultural evolution. As in any kind of evolutionary process, novelty must be balanced by preservation.

In biological evolution, the novelty-generating components are genetic mutation and recombination, and the novelty-preserving components include the survival and reproduction of “fit” individuals. In cultural evolution , the novelty-generating component is creativity, and the novelty-preserving components include imitation and other forms of social learning.

It isn’t actually necessary for everyone to be creative for the benefits of creativity to be felt by all. We can reap the rewards of the creative person’s ideas by copying them, buying from them or simply admiring them. Few of us can build a computer or write a symphony, but they are ours to use and enjoy nevertheless.

Inventor or imitator?

There are also drawbacks to creativity . Sure, creative people solve problems, crack jokes, invent stuff; they make the world pretty and interesting and fun. But generating creative ideas is time-consuming. A creative solution to one problem often generates other problems, or has unexpected negative side effects.

Creativity is correlated with rule bending, law breaking, social unrest, aggression, group conflict and dishonesty. Creative people often direct their nurturing energy towards ideas rather than relationships, and may be viewed as aloof, arrogant, competitive, hostile, independent or unfriendly.

Also, if I’m wrapped up in my own creative reverie, I may fail to notice that someone else has already solved the problem I’m working on. In an agent-based computational model of cultural evolution , in which artificial neural network-based agents invent and imitate ideas, the society’s ideas evolve most quickly when there is a good mix of creative “inventors” and conforming “imitators.” Too many creative agents and the collective suffers. They are like holes in the fabric of society, fixated on their own (potentially inferior) ideas, rather than propagating proven effective ideas.

Of course, a computational model of this sort is highly artificial. The results of such simulations must be taken with a grain of salt. However, they suggest an adaptive value to the mixed signals teachers send about creativity. A society thrives when some individuals create and others preserve their best ideas.

This also makes sense given how creative people encode and process information. Creative people tend to encode episodes of experience in much more detail than is actually needed. This has drawbacks: Each episode takes up more memory space and has a richer network of associations. Some of these associations will be spurious. On the bright side, some may lead to new ideas that are useful or aesthetically pleasing.

So, there’s a trade-off to peppering the world with creative minds. They may fail to see the forest for the trees but they may produce the next Mona Lisa.

Innovation might keep us afloat

So will society naturally self-organize into creators and conformers? Should we avoid trying to enhance creativity in the classroom?

The answer is: No! The pace of cultural change is accelerating more quickly than ever before. In some biological systems, when the environment is changing quickly, the mutation rate goes up. Similarly, in times of change we need to bump up creativity levels — to generate the innovative ideas that will keep us afloat.

This is particularly important now. In our high-stimulation environment, children spend so much time processing new stimuli that there is less time to “go deep” with the stimuli they’ve already encountered. There is less time for thinking about ideas and situations from different perspectives, such that their ideas become more interconnected and their mental models of understanding become more integrated.

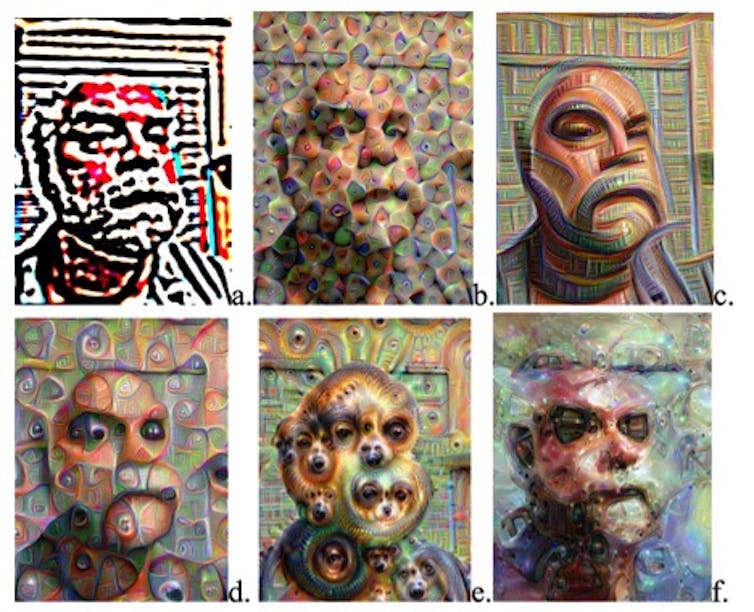

This “going deep” process has been modeled computationally using a program called Deep Dream , a variation on the machine learning technique “Deep Learning” and used to generate images such as the ones in the figure below.

The images show how an input is subjected to different kinds of processing at different levels, in the same way that our minds gain a deeper understanding of something by looking at it from different perspectives. It is this kind of deep processing and the resulting integrated webs of understanding that make the crucial connections that lead to important advances and innovations.

Cultivating creativity in the classroom

So the obvious next question is: How can creativity be cultivated in the classroom? It turns out there are lots of ways ! Here are three key ways in which teachers can begin:

Focus less on the reproduction of information and more on critical thinking and problem solving .

Curate activities that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries, such as by painting murals that depict biological food chains, or acting out plays about historical events, or writing poems about the cosmos. After all, the world doesn’t come carved up into different subject areas. Our culture tells us these disciplinary boundaries are real and our thinking becomes trapped in them.

Pose questions and challenges, and follow up with opportunities for solitude and reflection. This provides time and space to foster the forging of new connections that is so vital to creativity.

- Cultural evolution

- Creative pedagody

- Teaching creativity

- Creative thinking

- Back to School 2017

Events Officer

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, a conceptual graph-based model of creativity in learning.

- 1 Educational Technology Lab, German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence, Berlin, Germany

- 2 Computer Science Education/Computer Science and Society Lab, Institute of Informatics, Humboldt-University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 3 Department of Software and Information Systems Engineering, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel

- 4 School of Informatics, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Teaching creativity is one of the key goals of modern education. Yet, promoting creativity in teaching remains challenging, not least because creative achievement is contingent on multiple factors, such as prior knowledge, the classroom environment, the instruction given, and the affective state of the student. Understanding these factors and their interactions is crucial for successfully integrating creativity in teaching. However, keeping track of all factors and interactions on an individual student level may well exceed the capacity of human teachers. Artificial intelligence techniques may thus prove helpful and necessary to support creativity in teaching. This paper provides a review of the existing literature on creativity. More importantly, the review is distilled into a novel, graph-based model of creativity with three target audiences: Educators, to gain a concise overview of the research and theory of creativity; educational researchers, to use the interactions predicted by theory to guide experimental design; and artificial intelligence researchers, who may use parts of the model as a starting point for tools which measure and facilitate creativity.

1. Introduction

Fostering creative problem solving in students is becoming an important objective of modern education ( Spendlove, 2008 ; Henriksen et al., 2016 ). However, psychological research has found that creativity in classrooms is contingent on many contextual variables ( Kozbelt et al., 2010 ; Csikszentmihalyi, 2014 ; Amabile, 2018 ), that negative myths regarding creativity are abound ( Plucker et al., 2004 ), and that creativity is in tension with other educational goals like standardization ( Spendlove, 2008 ; Henriksen et al., 2016 ). As such, it appears highly challenging to successfully integrate creativity in teaching, alongside a wide variety of other educational goals that have to be achieved ( Spendlove, 2008 ).

Artificial intelligence may point a way forward by monitoring and enhancing the creative process in students without putting additional workload on teachers ( Swanson and Gordon, 2012 ; Muldner and Burleson, 2015 ; Roemmele and Gordon, 2015 ; Clark et al., 2018 ; Kovalkov et al., 2020 ; Beaty and Johnson, 2021 ). However, for such systems to be successful, we require a model of creativity that can be implemented computationally ( Kovalkov et al., 2020 ). In this paper, we review the existing literature on creativity in learning to provide a starting point for such a model–although our conceptual model must still be translated to a computational version. Few reviews of creativity research have focused on education and none, to our knowledge, have attempted to integrate the research result into a single model. We close this gap in the literature.

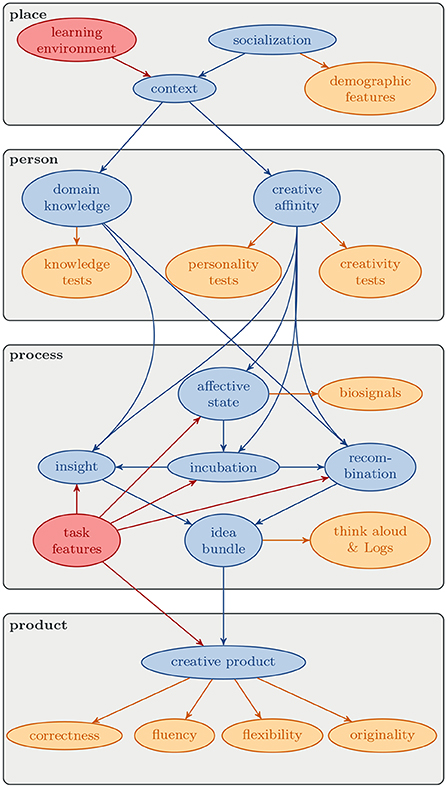

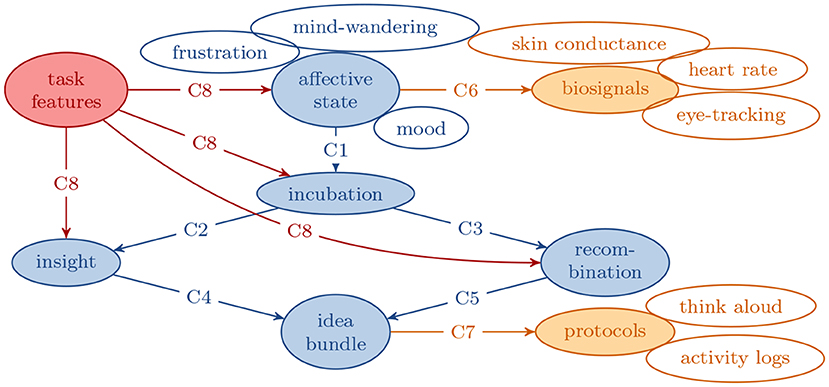

More precisely, we develop a conceptual, graph-based model of creativity in learning (see Figure 1 ), which we distill from prior research from the fields of psychology, education, and artificial intelligence. We design our model with three criteria in mind. It should be

• Comprehensive , in the sense that it includes all variables and interactions that are important for creativity in teaching, according to the existing literature,

• Minimal , in the sense that it does not introduce variables or interactions beyond what has been found in prior literature and restricts itself to variables that are relevant to creativity in teaching, and

• Consistent , in the sense that it remains a valid causal graph without loops or disconnected nodes.

Figure 1 . Our conceptual, graph-based model of creativity. Each student/personality, process, and product corresponds to a replicate of a plate in this graph. Red-colored nodes refer to interventional variables, orange nodes to observable variables, and blue nodes to hidden variables.

We note that there is tension between these goals. Namely, comprehensiveness encourages more nodes, whereas minimality encourages fewer nodes. Comprehensiveness means including nodes and relationships which are in conflict, whereas consistency means avoiding such conflicts. During the construction of our model, we will make note of such tensions and how we chose to resolve them. Thus, we also provide insight into consensus and lack thereof in the literature.

Following the 4P framework of Rhodes (1961) , our model has four components, namely the (social) place or press in which creativity occurs, the person who performs a creative task, the creative process itself, and the product of the task. For each component, we distinguish between latent variables, observable variables, and intervention variables. This distinction is useful to design practical strategies for promoting creativity: we can manipulate an intervention variable, monitor observable variables, and thus make inferences regarding the effect of our intervention on latent variables.

Consider the example of a math course. One variable we can intervene upon is the difficulty of a math task. But even this simple intervention may influence creativity very differently, depending on a multitude of factors: if we make a task easy, some students may be bored such that they disengage and submit a basic and uncreative solution. Other students may be motivated to solve a boring task in a particularly creative way to make it interesting. Conversely, a harder task may lead some students to submit particularly unoriginal solutions to solve the task at all, whereas other students may be engaged by the challenge and thus more motivated to find a particularly clever solution.

The purpose of our conceptual model is to make such mechanisms more transparent, to make creative achievement more predictable and, as a result, enable interventions to facilitate creativity. Accordingly, we believe that our proposed model is not only useful for artificial intelligence researchers, but also for teachers and educational researchers to inform their instructional strategy and their study design, respectively.

In this paper, we focus on providing three main contributions:

(1) Reviewing the existing work on creativity in learning,

(2) Distilling a conceptual, graph-based model of creativity in learning from our review, and

(3) Discussion of potential applications and challenges of putting the developed conceptual model into practice.

The paper is structured as follows: First, we provide a detailed discussion on the evolution of creativity definitions and creativity research to date (Section 2). The discussion is intended to show more clearly the multifaceted nature of creativity. Consequently, we discuss prior works on how artificial intelligence techniques have been used to generate creative behaviors in computers and in humans (Section 2). The third section presents the methodologies used for gathering the necessary literature for the conceptual model (Section 3). In the fourth section (Section 4), we present the proposed conceptual model of creativity, in four different creativity plates namely place, person, process, and product. Finally, we discuss limitations and points to future work (Section 5).

2. Background and related work

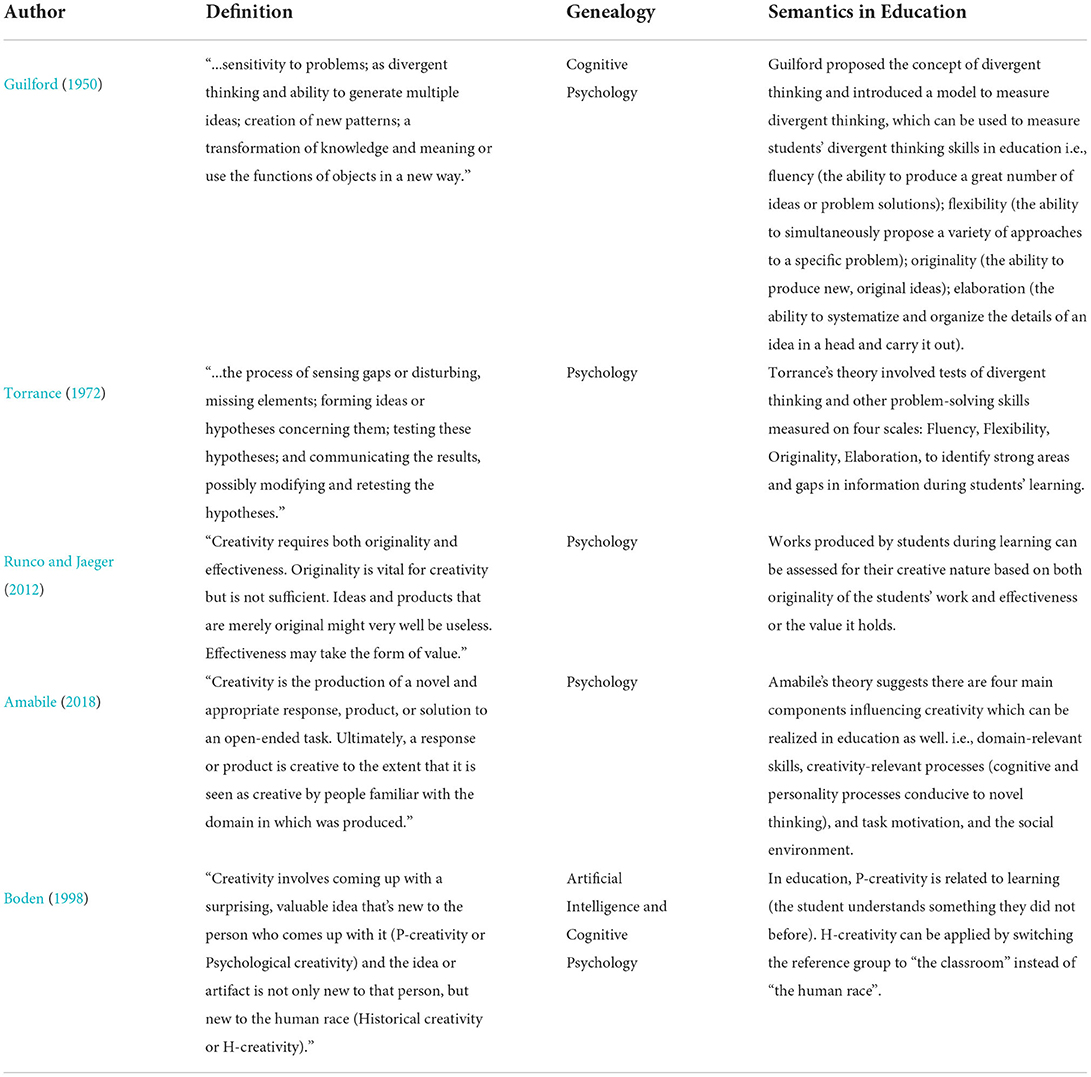

The roots of creativity research date back at least to the 19th century, when scholars attempted to define creativity philosophically ( Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ). The motivation for such scholarship was to find a shared trait that enabled creative geniuses to achieve works of art and science ( Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ). Accordingly, creativity was mostly seen as an innate trait of a small elite, a gift to create things both useful and beautiful ( Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ). Creativity was defined much broader after the second world war, in attempts to develop creativity tests which quantify creative problem solving skills in the general population ( Csikszentmihalyi, 2014 ). Creativity tests broadly fell into two classes: First, tests that pose creative problem-solving tasks and measure creativity as the success in solving these tasks (e.g., Torrance, 1972 ; Williams, 1980 ; Runco et al., 2016 ). Second, autobiographic surveys which measure creativity as the sum of past creative achievement (e.g., Hocevar, 1979 ; Diedrich et al., 2018 ). Importantly, both classes of tests frame creativity as the trait of a person . In the words of Guilford (1950) : “creativity refers to the abilities that are most characteristic of creative people”. The implicit view 1 of the time seems to be that creativity is an innate property of people that is either present or not, independent of context. This view has been criticized in the decades to come, especially by Amabile (2018) and Csikszentmihalyi (2014) , who emphasized that creativity is dependent on a host of contextual factors such as individual motivation, ability to solve a problem from multiple perspectives, the domain in question ( Baer, 2010 ), and who gets to be the judge of creativity. Table 1 shows an overview of creativity definitions in the literature and how they relate to education.

Table 1 . Definitions of creativity in prior literature.

The current discussion about creativity research is characterized by two aspects: the variety in creativity theories and creativity definitions, and the challenges of applying creativity models for pedagogical implementations. The aspect of pedagogical implementations is important because there still exists potential barriers to computationalize the definitions of creativity. To address this complex phenomenon, we discuss existing works on creativity and works on artificial intelligence for creativity in learning.

2.1. Prior reviews on creativity

Multiple other scholars have already provided reviews of this long research tradition, complementary to our present work. Mumford (2003) summarizes book chapters on creativity, covering multiple theories that existed at the time, as well as empirical findings on the role of factors such as expertise, motivation, affect, situational factors, and development. These findings form one of the bases for our own model.

Cropley and Cropley (2008) propose a theory that divides a creative activity into seven phases, namely preparation, activation, cogitation, illumination, verification, communication, and validation. A key motivation for this phase model is to resolve paradoxes in creativity, e.g., that convergent thinking both hampers and supports creativity. In the phase model, convergent thinking is crucial in the preparation, illumination, and verification phases, but detrimental in the activation phase, where divergent thinking is required. More generally, Cropley and Cropley (2008) relate each phase to the four P's—press, person, process, and product—of Rhodes (1961) . Our own work follows the example of Cropley and Cropley (2008) in that we try to provide a consistent model that is compatible with the wider literature. However, our perspective is slightly wider, in that we do not only focus on a single creative activity but an entire course or tutoring system.

Kozbelt et al. (2010) reviewed theories of creativity and classified them into ten different classes, namely developmental, psychometric, economic, process, expertise-based, problem-finding, evolutionary, typological, and systems theories. Given the wide variety of perspectives, they recommend to not attempt a “grand unifying theory” but to include the perspectives relevant to a certain application. We aim to follow this recommendation. In particular, we limit ourselves to theories that apply to creativity in learning, but we aim to be comprehensive for this setting, including the developmental, process, expertise-based, and systems perspective, and we try to be explicit how our model is situated in the broader landscape of creativity research.

Sawyer (2011) reviews neuroscience studies of creativity, especially studies involving EEG, PET, and fMRI recordings. He highlights that neural activation during creative activity is not localized in a certain brain area but involves a wide variety of areas (such as psychological and cognitive areas; Guilford, 1950 ; Vosburg, 1998 ; Mumford, 2003 ; Sawyer, 2006 ; Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ; Csikszentmihalyi, 2014 ; Kaufman, 2016 ; Zhou, 2018 ) that are also active during everyday activity ( Khalil et al., 2019 ); that subconscious processes appear to be crucial for creativity, such as mind wandering; and that the importance of domain-specific knowledge is confirmed. Despite this complexity, the work of Muldner and Burleson (2015) indicates that creativity can be detected from EEG signals (in combination with skin conductance and eye tracking) at least for a geometry problem.

Similarly, Zhou (2018) reviews creativity-related studies involving fMRI and EEG signals to assess human brain function while performing creativity-related cognitive tasks. In line with Sawyer (2011) 's findings, the author highlights studies that show neural activities are not limited to a particular region in a human brain, and in fact, some studies ( Liu et al., 2012 ; Takeuchi et al., 2013 ; Vartanian et al., 2013 ) show that neural efficiency (i.e., most efficient brain functioning or more focused brain activation) in creative thinking can be attained through cognitive training, as well as targeted training on fundamental cognitive abilities such as attention and working memory ( Vartanian et al., 2013 ). Our review is different because our focus is not neuroscience but, rather, creativity as an outcome of a cognitive process that depends on personal and context variables.

Runco and Jaeger (2012) review the history of creativity research leading up to what they call the standard definition of creativity , namely that creativity combines originality with effectiveness (alternatively: usefulness, fit, or appropriateness). We include this standard definition to define creativity in products, but we also go beyond the standard definition by including place, person, and process in our model.

Finally, Schubert and Loderer (2019) review creativity-related tests and classify them according to their relation to the 4P model ( Rhodes, 1961 ) and their method (self-report survey, expert judgment, psychometrics, and qualitative interview). We incorporate such techniques as observable variables in our model.

Overall, we build upon all these prior reviews but also provide complementary value in our focus (creativity in teaching), our scope (all variables related to a course), and our approach (a graph model).

2.2. Artificial intelligence and creativity

Our goal is to facilitate the construction of artificial intelligence tools that measure and support human creativity. This is in contrast to most prior work in artificial intelligence on creativity, which has been focused on generating creative behavior in computers (computational creativity; Jordanous, 2012 ; Mateja and Heinzl, 2021 ). In this field, the work of Boden (1998) has been foundational. Boden understands creativity as three operations on a knowledge base, namely

• Exploration: Computing the knowledge space corresponding to a given domain,

• Recombination: Combining existing ideas in a new context or fashion, and

• Transformation: Giving the knowledge space new rules by which it can be processed (a distant reminder of SWRL rules in OWL, as proposed by Horrocks and Patel-Schneider, 2004 ).

While these three operations do not necessarily describe creativity in human thinking, we do believe that it can be useful to distinguish between ideas that emerge by insight/illumination and ideas that result from recombining existing ideas. Accordingly, we translate this distinction into our model.

Ram et al. (1995) elaborate Boden's model by discussing the difference between knowledge and thinking. The authors add the task, situation, and strategic control of inference as dimensions and claim that only a combination of these will constitute the basis for thought. We believe that these extensions are suitably covered in our model by the process and person variables.

Similar to the standard definition of creativity, Boden states that creativity requires novelty and a positive evaluation of the creative product (i.e., appropriateness). In terms of novelty, Boden distinguishes between P-creativity (an idea is novel only to myself), and H-creativity (an idea is novel with respect to the entire society). Lustig (1995) suggests to generalize this distinction to “novelty with respect to a reference community”, which is also the view we take.

Jordanous (2012) argues that it is crucial to evaluate computationally generated products with a shared (fair) standard. Just as in human creativity, optimizing for originality alone is insufficient, one also requires a domain-specific usefulness standard. Accordingly, most seminal works in computational creativity have invested much effort into finding domain-specific rules to explore in a way that is more likely to generate appropriate results ( Baer, 2010 ; Colton and Wiggins, 2012 ). A lesson for our model is that the “appropriateness” measure of creative products needs to be well-adjusted to the task in order to make sure that we do not misjudge creative products. Further, there is debate whether it is sufficient for evaluation to judge the final product or whether the computational process must be included in the evaluation. We account for this by including the process in our model.

Recently, machine learning models and, specifically, generative neural networks have been utilized to generative computationally creative works ( DiPaola et al., 2018 ; Berns and Colton, 2020 ; Mateja and Heinzl, 2021 ). This is somewhat surprising as generative models are intrinsically novelty-averse as they are trained to model and reproduce an existing data distribution ( DiPaola et al., 2018 ; Berns and Colton, 2020 ). Still, by cleverly exploring the latent space of such models, one can generate samples that appear both novel and domain-appropriate, hence indicating creativity ( DiPaola et al., 2018 ; Berns and Colton, 2020 ). Such an approach searches for novelty between existing works and can, as such, be viewed as recombination ( DiPaola et al., 2018 ), which we also include in our model.

2.3. Artificial intelligence for creativity in education

Using artificial intelligence to measure and support creativity in education is a relatively recent approach. Huang et al. (2010) developed an “idea storming cube” application for collaborative brainstorming which automatically measures creativity by the number of distinct generated ideas. Muldner and Burleson (2015) used biosensors and machine learning to distinguish high and low creativity students in a geometry tasks. Kovalkov et al. (2020 , 2021) define automatic measures of creativity in computer programs in terms of fluency, flexibility, and originality, following the work of Torrance (1972) . Hershkovitz et al. (2019) ; Israel-Fishelson et al. (2021) quantify the relation between creativity and computational thinking in a learning environment. Finally, Cropley (2020) highlights the need to teach creativity-focused technology fluency to make use of AI and other novel technologies. Given the relative paucity of such works, we believe there is ample opportunity for further research at the intersection of artificial intelligence, education, and creativity, which we wish to facilitate with our model.

3. Literature search

To scan the literature for relevant contributions, we used two techniques.

First, we performed a snowball sampling ( Lecy and Beatty, 2012 ), meaning we started with the foundational seed papers of Boden (1998) and Runco and Jaeger (2012) and branched out from there, following their references as well as papers that cited them, recursively.

Second, we started a structured keyword search. Here we focused on the application of creativity measurement in the area of learning and formal educational institutions. The keywords used were “creativity AND measure”, “creativity AND analytics”, “creativity AND learning”, “creativity AND tutoring”, as well as “creativity AND [school subject]”. For the list of school subjects we used the German secondary curriculum.

We searched for the keywords in the following data bases (with the number of initial search results in brackets).

• Google Scholar (107)

• ACM digital library (8)

• ScienceDirect (17)

• Elsevier (344)

• IEEE Explore (20)

• Jstor (2)

Note that there are duplicates between the searches.

In order to narrow down the relevant literature for the goal of constructing a model of creativity that is easy to use in the field of educational technologies, content filters were applied. These are not as succinct as the keywords as they usually consist of two or more dimensions that function as decision boundaries whether to keep a paper for the output model or not. For example, we encountered one paper that dealt with creativity as part of design. On the one hand, it fit our lens because it provided a clear and operational definition of creativity. However, it did not satisfy the rule that the creativity definition should be generic regarding the fields of learning.

In the following we provide list of dimensions that were used to filter the literature.

• A general definition of creativity beyond a single domain,

• a clear and well-defined concept of creativity,

• creativity is seen as measurable,

• the concept of creativity does not contradict its use in the learning field, and

• the creativity definition contains either a measurement or a product component.

In the end, 77 papers remained after applying our filters (marked with a * in the literature list). Of these, eight cover artificial intelligence approaches.

Note that it is still possible that interesting related works are not covered because they evaded our particular search criteria. Nonetheless, we aim to be comprehensive and representative. We distill our results into a graph-based model in the following section.

4. A conceptual graph-based model of creativity

In this section, we provide a conceptual, graph-based model of creativity (refer to Figure 1 ), based on a review of the existing literature. As noted in Section 1, we aim for a model which is comprehensive, minimal , and consistent . To achieve these objectives, we opt for a conceptual, graph-based model ( Waard et al., 2009 ). A graph enables us to include all variables and their relationships, as stated in the literature (comprehensiveness), aggregate variables that fulfill the same function in the graph (minimality), and avoid cycles in the graph (consistency). We keep our model abstract enough to cover a wide range of positions expressed in the literature but specific enough to understand how creativity in learning comes about. Therefore, we model the network structure but avoid quantitative claims regarding the strength of connections.

In particular, we represent a relevant variable x as a node in our graph and a hypothesized causal influence of a variable x on another variable y as an edge/arrow ( Waard et al., 2009 ). We further distinguish between three kinds of variables: Intervention variables (red) are variables that educators can manipulate to influence creativity, namely the curriculum and task design. Observable variables (orange) are variables that we can measure via tools established in the literature, such as sensors, creativity tests, or teacher judgments. Finally, latent variables (blue) are all remaining variables, i.e., those that we can neither directly observe nor intervene on, but which are nonetheless crucial for creativity. Most importantly, this includes the creative process inside a student's mind. Importantly, we only include a node if the respective variable is named in at least one of the 77 papers we reviewed; and we only include an edge if the respective connection is indicated in at least one of these papers. In Figures 2 – 5 , each edge is annotated with the literature it is based on.

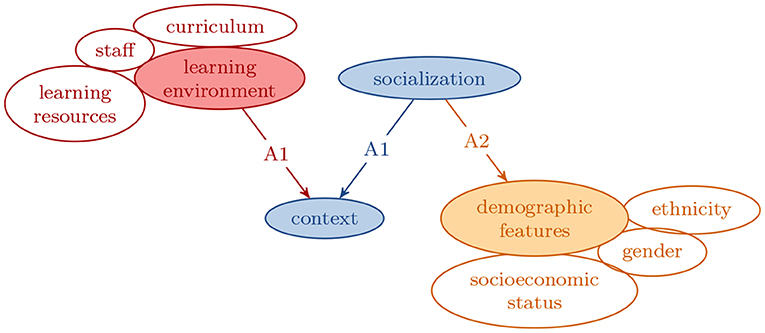

Figure 2 . A closer look at the place (or environment) plate. It highlights a (few) external factors that influences an individuals' knowledge and behavior. Citations: A1 ( Csikszentmihalyi, 2014 ; Amabile, 2018 ), A2 ( Runco et al., 2017 ; Castillo-Vergara et al., 2018 ).

Finally, we group our variables into plates according to the four Ps of Rhodes (1961) , namely place, person, process, and product. We use this particular structure for three reasons. First, the paper of Rhodes (1961) can be regarded as a foundational paper of the field (cited 3,099 times according to Google scholar) such that the basic structure of the four Ps can hopefully be regarded as accepted–we did not find evidence to the contrary, at least. Second, the four Ps comprehensively cover a wide variety of topics and are, thus, well-suited for a literature review. Third, the four Ps provide a well-defined framework which allows us to sort existing work according to scope (from societal to personal) and time scales (from societal change over years to second scale).

Consider the example of a math course. For each relevant social group in our class, we need a copy of the “place” plate that models the respective socialization. For each student, we need a copy of the “person” plate, describing individual domain knowledge and creative affinity. For each learning task and each student, we need a copy of the “process” plate which describes the student's work on this particular task. And finally, for each submitted task solution in the course, we need a copy of the “product” plate.

In the remainder of this section, we will introduce each plate in detail and justify nodes and edges based on the literature.

In our model, the term “place” or “press” (press was the original word used by Rhodes, 1961 ) covers environmental factors influencing creativity which go beyond a single learning task or student. Prior work has covered, for example, the social group in which students learn ( Amabile, 2018 ), students' socio-economic status ( Hayes, 1989 ), and the broader culture, where notions of creativity change over decades and centuries ( Csikszentmihalyi, 2014 ). Following this work, we define “place” as the aggregation of all variables outside of a student's individual cognition which may influence their creativity. To make this definition more practically applicable, we introduce two separate nodes in our graph: the learning environment and the socialization.

In more detail, we define the learning environment as the collection of variables that educators or system designers can intervene upon but which go beyond an individual student or task, such as the teaching staff, the access to auxiliary resources, the quality of such resources, and the prior curriculum that the students were exposed to before entering the current course. By contrast, we define the socialization as the collection of variables which we are outside educators' control but nonetheless influence students' creativity beyond a single person or task. While the socialization, as such, is hidden, we can measure proxy variables, such as gender, socioeconomic status, or ethnicity ( Runco et al., 2017 ; Castillo-Vergara et al., 2018 ), which can also be captured in digital learning environments or intelligent tutoring systems.

While not the focus of this work, we note that students are oftentimes subject of (structural, indirect) discrimination based on such proxy features and special attention must be paid to promoting equity instead of exacerbating existing biases in society ( Loukina et al., 2019 ). For example, one can try to adjust the learning environment to deliberately counterbalance the differential impact of socialization on creativity.

Note that there is no consensus in the literature how strongly different aspects of socialization or learning environment influence creativity. Amabile (2018) ; Csikszentmihalyi (2014) would argue for a strong influence of socialization, for example, whereas (some) creativity tests (implicitly) assume that it is possible to quantify creative affinity independent of context, in a lab setting ( Torrance, 1972 ; Williams, 1980 ). Further, the relationship between socialization and observable, easy-to-measure demographic variables is complex and one can argue for different scales ( Buchmann, 2002 ). Our model is abstract enough to accommodate either position: If one believes that socialization has a small or large influence, one can apply a small or large weight to the respective arrow. Similarly, one could fill the “demographic features” node with different scales, depending on which aspects of socialization should be measured.

4.2. Person

In our model, a person is a student who is enrolled in a course or an intelligent tutoring system and has an individual capacity for creative achievement within this course.

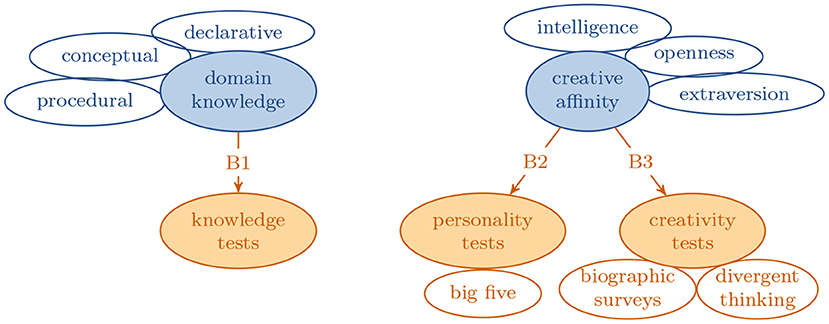

A large number of prior works has investigated which personality traits or skills facilitate creativity. For example, Hayes (1989) argues that creative thinking can be broken down into a combination of other skills, like domain knowledge, general education, mental flexibility, different representations of knowledge, and hard work. Hayes (1989) also claims that there is no relation between general intelligence and creativity, after controlling for domain knowledge and education. By contrast, Guilford (1967) argues that intelligence is a necessary but not sufficient condition for creativity, which sparked an ongoing series of empiric studies (e.g., Jauk et al., 2013 ; Weiss et al., 2020 ). Beyond intelligence and cognitive skills, there has been ample research on the connection between personality traits, especially openness to experiences and extraversion in the big-five inventory (e.g., Eysenck, 1993 ; Sung and Choi, 2009 ; Karwowski et al., 2013 ; Jauk et al., 2014 ).

Most tests for of a person's capacity for creativity assess either the amount of past creative achievement via biographic questions ( Hocevar, 1979 ; Diedrich et al., 2018 ), or confront a person with a specific, psychometrically validated creative task and measure their performance in this task ( Torrance, 1972 ; Williams, 1980 ; Runco et al., 2016 ). Such tasks typically consist of a prompt, in response to which a person is asked to come up with as many ideas as possible. The number (fluency), distinctness (flexibility), and novelty (originality) of these ideas is then used as a measure of creativity ( Torrance, 1972 ; Kim, 2006 ).

Note that all these tests share an implicit assumption, namely that creativity is, to some degree, generalizable. In other words, if a person behaves creatively in one context, this translates to creativity in other contexts. This is in tension with the view that creativity can only be judged in context ( Amabile, 2018 ). Sternberg (2005) proposes an intermediate position: knowledge is domain-specific but there also exist thinking styles and other factors that are domain-general. This view is also mirrored in cognitive science. For example, ( Burnard, 2011 , p. 141) writes: “Especially important is the notion that creative learning is a mediated activity in which imaginative achievement and the development of knowledge have a crucial role.”, and ( Mumford et al., 2011 , p. 32) adds: “Knowledge is domain-specific. Moreover, multiple alternative knowledge structures may be employed in creative thought within a domain, schematic, case-based, associational, spatial, and mental model knowledge structures, and these knowledge structures appear to interact in complex ways.” In this quote, Mumford also indicates that domain-specific knowledge and domain-general skills influence the creative process in different ways. We will account for this difference in our process plate later.

In our model, we represent a person—that is, a student—by two nodes, namely domain knowledge and creative affinity. Domain knowledge includes declarative, procedural, and conceptual knowledge for any domain that is relevant to the current course. By contrast, creative affinity includes all variables that vary between people but are domain-general, such as openness to experiences, extraversion, (general) intelligence, and generalized creative capacity. To measure domain knowledge, we suggest domain-specific knowledge tests, which we do not cover here for brevity (refer, e.g., to Schubert and Loderer, 2019 ). To measure creative affinity, literature suggests personality tests 2 and/or creativity tests, as listed above, yielding the graph in Figure 3 . In the overall model ( Figure 1 ), we also include incoming arrows that account for possible influence of the (social) context on both domain knowledge and creative affinity.

Figure 3 . A closer look at the person plate. This plate includes variables describing the creative capacity of a single student. We provide examples of such variables from the literature in transparent nodes. Citations: B1 ( Hayes, 1989 ; Sternberg, 2005 ; Mumford et al., 2011 ; Schubert and Loderer, 2019 ), B2 ( Eysenck, 1993 ; Sung and Choi, 2009 ; Karwowski et al., 2013 ; Jauk et al., 2014 ), B3 ( Torrance, 1972 ; Hocevar, 1979 ; Williams, 1980 ; Diedrich et al., 2018 ).

Our model refrains from making any assumptions regarding the weight of each edge or the specific form of the influence because there is no consensus in the literature regarding these questions. Some authors might argue that there is no general “creative affinity” at all, but only context-dependent affinity ( Amabile, 2018 ), whereas some creativity tests would argue that domain-general creative affinity does exist ( Runco et al., 2016 ). There is also professional debate regarding the value of personality tests to measure creative affinity ( Schubert and Loderer, 2019 ), which creativity test is best suited to measure creative affinity ( Runco et al., 2016 ), or how knowledge tests ought to be constructed ( Schubert and Loderer, 2019 ).

4.3. Process

In our model, a process refers to the chain of cognitive activities a student engages in while trying to solve a specific learning task, from receiving the task instructions to submitting a solution attempt.

Researchers have developed multiple theories how the creative process is structured. Rhodes (1961) lists four different steps, namely preparation, incubation, inspiration, and verification. Preparation refers to the pre-processing of input information; incubation to the conscious and unconscious further processing, revealing new connections between known pieces; inspiration to the actual generation of an idea during incubation; and verification to the conversion of a rough idea to a creative product. Cropley and Cropley (2008) splits “incubation” into “activation” (relating a problem to prior knowledge) and “cogitation” (processing the problem and prior knowledge), renames “inspiration” to “illumination”, and adds two new phases at the end, namely “communication” and “validation”. These new phases account for the social context of creativity, namely that a creative product only “counts” if it has been communicated to and validated by other people.

In contrast to these models, Treffinger (1995) argues that creative problem solving does not occur in strict phases but by inter-related activities such as problem-finding and solution-finding. Similarly, Davidson and Sternberg (1984) suggest the following three processes:

1. Selective encoding: distinguishing irrelevant from relevant information,

2. Selective combination: taking selectively encoded information and combining it in a novel but productive way, and

3. Selective comparison: relating new information to old information.

Davidson and Sternberg's view aligns well with Boden's model of artificial creativity ( Boden, 1998 ). In particular, selective encoding can be related to exploration, combination and comparison to recombination, and comparison to transformation. An alternative computational view is provided by Towsey et al. (2001) , who argue that creativity can be described as an evolutionary process. From a set of existing ideas, the ones that best address the current problem are selected (selective comparison and encoding) and recombined to form a new set of existing ideas (selective combination), until a sufficiently good solution to the problem is found.

Multiple scholars agree that repurposing and combining prior knowledge is crucial for creativity. For example, Lee and Kolodner (2011) relate creativity to case-based reasoning, where a new problem is compared against a data base of known problems and the best-matching solution is retrieved and adapted to the present case. Such case-based reasoning can be regarded as creative if the relation between the past case and the present case is non-obvious but the solution still works. Similarly, Hwang et al. (2007) argue that creativity is related to making ordinary objects useful in a novel and unexpected way. Sullivan (2011) names this repurposing process “Bricolage” in reference to the work of Levi-Strauss (1966) .

There is some disagreement in the literature regarding the creative process. Nonetheless, we aim to provide a model that is as widely compatible as possible while remaining useful. In particular, we include three cognitive processes, namely incubation, recombination, and insight. Incubation refers to processing the existing set of ideas to support idea generation. Recombination refers to generating new ideas by combining existing ones. Finally, insight refers to generating new ideas beyond combination, e.g., via re-purposing. Both recombination and insight generate ideas which the student needs to validate against the problem at hand ( Cropley and Cropley, 2008 ). After validation, the ideas become part of the “idea bundle”, that is, the current working set of ideas that may end up as parts of the solution. Note that our model is compatible both with models that emphasize the order of different phases ( Cropley and Cropley, 2008 ), as well as models which focus more on the different types of operations used to generate creative ideas, without regard for their order ( Davidson and Sternberg, 1984 ; Treffinger, 1995 ). Across theories, there is broad agreement that ideas can be generated via recombination or insight and that they get filtered or validated before they become part of a solution to a learning task.

The final component of our process model is the affective state. Amabile (2018) argues that the affective state influences creativity, which is confirmed by several empiric studies. For example, Csikszentmihalyi (1996) finds that a positive affective state (such as flow state) is identified in individuals when they are being highly creative; Vosburg (1998) find that positive mood facilitates divergent thinking; and the review of Davis (2009) finds that (moderate amounts of) positive also affect enhances creativity. However, George and Zhou (2002) also point to scenarios where bad mood is related to better creativity outputs, especially when short moments of frustration motivate refinement and improvement ( Muldner and Burleson, 2015 , as described by), which could be seen as an aspect of incubation. Further, Baird et al. (2012) ; Sawyer (2011) found that absent-mindedness or mind-wandering are crucial to incubation. Accordingly, we include an arrow form the affective state to incubation, yielding the graph of blue nodes in Figure 4 .

Figure 4 . A closer look at the process plate. The nodes represent different stages of the student cognitive process to generate and validate creative ideas, namely insight, incubation, and recombination, as well as the affective state which influences the process and the idea bundle as result of the process. Citations: C1 ( George and Zhou, 2002 ; Sawyer, 2011 ; Baird et al., 2012 ), C2 ( Rhodes, 1961 ; Cropley and Cropley, 2008 ), C3 ( Davidson and Sternberg, 1984 ; Boden, 1998 ), C4/C5 ( Cropley and Cropley, 2008 ), C6 ( Cooper et al., 2010 ; Blanchard et al., 2014 ; Muldner and Burleson, 2015 ; Pham and Wang, 2015 ; Faber et al., 2018 ), C7 ( Kim, 2006 ; Huang et al., 2010 ; Bower, 2011 ; Sullivan, 2011 ; Liu et al., 2016 ), C8 ( Amabile et al., 2002 ; Baer and Oldham, 2006 ).

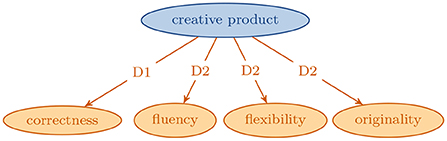

Figure 5 . A closer look at the product plate. It describes the creativity of a product in terms of correctness, fluency, flexibility, and originality. Citations: D1 ( Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ), D2 ( Torrance, 1972 ; Huang et al., 2010 ; Muldner and Burleson, 2015 ; Yeh and Lin, 2015 ; Kovalkov et al., 2020 , 2021 ).

In line with Cropley and Cropley (2008) ; Amabile (1982) ; Baer (2010) , we emphasize that different cognitive skills contribute to different parts of the creative process. For example, domain knowledge is required for both insight and recombination of ideas, whereas creative affinity more broadly may also affect incubation ( Burnard, 2011 ), as summarized in Baer (2010) . Within creative affinity, one may also distinguish between divergent thinking, which is crucial for recombination and insight, whereas convergent thinking is crucial for filtering ideas before they get added to the idea bundle ( Cropley and Cropley, 2008 ).

While the process is, in principle, hidden because it occurs inside a student's mind, there do exist approaches to measure different aspects of the creative process as it happens. First, we can monitor a students' affective state via biosignals, as is evidenced by the literature on the detection of mind-wandering via skin conductance ( Cooper et al., 2010 ; Blanchard et al., 2014 ; Muldner and Burleson, 2015 ), heart rate ( Pham and Wang, 2015 ), or eye movement ( Iqbal et al., 2004 ; Schultheis and Jameson, 2004 ; Muldner and Burleson, 2015 ; Faber et al., 2018 ). Second, we can indirectly observe how the student's idea bundle develops over time. For one, we can ask students to verbalize their thinking while it happens (“think aloud” protocols). Such techniques are particularly promising for collaborative work where students need to interact and communicate their incomplete creative process with their group partners anyways ( Kim, 2006 ; Huang et al., 2010 ; Bower, 2011 ; Sullivan, 2011 ; Liu et al., 2016 ). Third, if students work inside a digital learning environment or intelligent tutoring system, we can log student activity and thus gather insight into their process ( Greiff et al., 2016 ).

As an example, consider a simple math multiplication question, such as 25·12. We could now ask the student to write down all intermediate steps they take. One student may apply a long multiplication, which requires the initial insight that long multiplication can be applied, the decomposition into 25·10 and 25·2, the solution of these intermediate steps (250 and 50), and finally the combination to the overall answer (250 + 50 = 300). Another student may connect the multiplication with geometry, draw a rectangle of 25 cm x 12 cm on a grid and count the number of grid cells covered. Finally, another student may recognize that 12 factors as 4·3, work out 25·4 = 100 and 100·3 = 300. In all cases, the different creative process becomes apparent by inspecting an activity log of the intermediate steps the students took.

This example also illustrates how the process is influenced by personal or contextual factors: If a student hasn't learned long multiplication, the first strategy is unavailable. If a student lacks time, or if the learning environment does not supply a grid, the second strategy is unavailable. If a student lacks experience in factorizing or is too stressed, the third strategy is unavailable.

Importantly, we can intervene on the creative process by designing task instruction and/or task environment in a specific way.

For example, Baer and Oldham (2006) found that time pressure influences creativity. In a workplace context, experienced time pressure was generally detrimental for creativity, except for participants with high openness to experience and high support for creativity, who performed best with a moderate level of time pressure. Similarly, Amabile et al. (2002) suggest that moderate levels of time pressure are endogenous within a team project, as it only allows an individual to be positively challenged, in turn triggering creativity. For our multiplication example, we would discourage the second strategy by imposing a strict time limit, which prohibits the time-intensive re-representation via geometry. Conversely, we would encourage the third strategy by providing the prime factorization of 12 as a hint in our instruction.

We aggregate all options of educators/designers to influence how a task is processed in a node we call “task features”. Following the terminology of VanLehn (2006) , task features include all aspects of the “inner loop” of our tutoring system, whereas the “learning/environment” in “place” includes the “outer loop”.

4.4. Product

We define a creative product as the result of translating a student's idea bundle into something tangible that can be inspected by a teacher, such as a response to a math question, including a log of all intermediate steps. This translation is lossy: Depending on the task features, a student may be more or less able to translate ideas into a product. Further, even the ideas that do get translated into a product may not be picked up by the sensors of our system because they lie outside our expectations when designing the system. As Hennessey et al. (2011) put it: creativity may be difficult to formalize in all its richness, but people recognize it when they see it. Accordingly, they suggest to assess creativity via a consensual assessment technique (CAT), using the judgment of a panel of human domain experts. Unfortunately, though, a panel of multiple experts is usually not available in education, especially not in automated systems. Accordingly, we turn toward notions of creativity in products that are easier to evaluate automatically.

There is wide agreement that two abstract criteria are necessary for creativity in products, namely novelty and appropriateness (sometimes with different names; refer to Sternberg and Lubart, 1999 ; Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ). For example, submitting a drawn flower as solution to an multiplication task is certainly novel, but it is inappropriate for the task. However, if the drawn flower encodes the right answer (e.g., via the number of petals), it is both novel and appropriate, thus counting as creative. Note that both criteria are context-dependent: appropriateness depends on the current learning task and novelty on the reference set to which the current solution is compared ( Sternberg and Lubart, 1999 ; Csikszentmihalyi, 2014 ; Amabile, 2018 ). In other words, if all students in a class submit flowers, this representation seizes to be novel.

Creativity tests provide further detail. For example, Torrance (1972) suggests multiple scales including

• Fluency: the number of generated ideas,

• Flexibility: the number of distinct classes of ideas, and

• Originality: the infrequency of ideas compared to a typical sample of students.

These three scales are particularly interesting because they have been applied in recent work on artificial intelligence for creativity in education. In particular, Huang et al. (2010) , Muldner and Burleson (2015) , and Kovalkov et al. (2020) all use fluency, flexibility, and originality to measure the creativity of student solutions (namely in a collaborative brainstorming task, geometry proofs, and Scratch programs, respectively). The Digital Imagery Test of Yeh and Lin (2015) measures creativity by the amount of unique associations (fluency/flexibility) in reaction to an ambiguous, inkblot-like picture. There is also some evidence that combining measures of fluency, flexibility, and originality with artificial intelligence can approximate human ratings ( Kovalkov et al., 2021 ).

We believe this body of work establishes that at least fluency, flexibility, and originality can be automatically assessed with computational methods and thus introduce these three dimensions as observable nodes in our model. Additionally, we include appropriateness as required by the “standard definition of creativity” of Runco and Jaeger (2012) . However, we call our node “correctness” to be more in line with the educational setting.

Returning to our math example, consider an assignment of multiple multiplication questions. We can measure correctness by counting how many answers a student got right; we can measure fluency by counting the number of different strategies the student employed; we can measure flexibility by measuring how different those strategies are; and we can measure originality by counting how often these strategies were used in a typical sample of students with the same amount of prior knowledge on the same assignment.

5. Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we reviewed the research on creativity and distilled a conceptual, graph-based model which captures all crucial variables as well as their relations (refer to Figure 1 ). This model can serve teachers to get a clearer understanding of creativity and how to measure and facilitate it in the classroom by adjusting task features/instruction. More specifically, Cropley and Cropley (2008) discuss how to improve instruction for creativity based on different phases of the creative process; and several interventions investigate automatic measurement and support for creativity in educational technology ( Huang et al., 2010 ; Muldner and Burleson, 2015 ; Hershkovitz et al., 2019 ; Israel-Fishelson et al., 2021 ; Kovalkov et al., 2021 ).

The proposed model can also be useful for educational researchers as a basis for study design, that is, which measures to include in a study and which connections to investigate. Finally, we hope to provide a starting point for the construction of artificial intelligence tools that measure and facilitate creativity, e.g., in intelligent tutoring systems. For example, one can use our model as an initial graph for a Bayesian network ( Barber, 2012 ) or a structural causal model ( Pearl, 2009 ). Such an implementation would permit probabilistic estimates for every variable and every individual student at every point in time, thus giving students and teachers a detailed view of creative developments and highlighting individual opportunities for higher creative achievement. We note that some approaches already exist which assess creativity in an educational setting, using AI components. For example, Muldner and Burleson (2015) classify high vs. low creative students from biosensor data, and Kovalkov et al. (2021) estimate the creativity of multimodal computer programs using regression forests.

Still, we acknowledge serious challenges in putting our model into practice. First, while we justified our nodes and edges via literature, we do not provide precise structural equations, as required by a structural causal model; nor probability distributions, as required by a Bayesian network. Any implementation needs to fill our model with “mathematical life” by making reasonable assumptions regarding connection strengths and the relation of incoming influences at each variable. Some of the following questions can help designers who aim to implement our conceptual model for a specific application scenario. Is the broader (social) context crucial in the scenario or are personal variables sufficient to model individual differences? Which knowledge domain is concerned and how can we measure domain-specific knowledge? Is a “generic” creativity affinity plausible in the scenario or is the contextual influence more important? Which aspects of a student's affective state are important for the scenario? Which theory of the creative process appears most plausible; e.g., a phase model or an “unordered model”? None of these questions is easy to answer and answers will require application-specific considerations. Nonetheless, the works cited in this paper can serve as inspiration.

Second, it is technologically challenging to implement a sufficient number of sensors (i.e., the orange nodes in Figure 1 ) to accurately estimate all latent variables (i.e., the blue nodes) in our model. Some sensors are domain-specific and thus need to be developed for any new domain, such as correctness, fluency, flexibility, and originality ( Kovalkov et al., 2020 ). Further, some of the sensors raise privacy concerns, especially biosignals. As such, it may be pragmatically advisable to limit the number of sensors. However, fewer sensors mean that it may become impossible to estimate (some) latent variables with sufficient certainty. Accordingly, one also needs to consider whether to exclude/simplify some latent variables for pragmatic reasons.

Third, creativity is not value-neutral. If a system judges a student/product as more creative than another, this judgment is value-laden and should not be made lightly. This is especially critical as even a full implementation of our model is unlikely to capture the full richness of creativity, including elements of aesthetic beauty, surprise, and other hard-to-formalize dimensions ( Runco and Jaeger, 2012 ). All that non-withstanding, we believe it is crucial to face the full complexity of creativity and to be explicit where we simplify the model to comply with practical constraints.

Beyond our existing model, further extensions may be useful in the future: First, our process model does not include cognitive load as explicit construct, which is a crucial variable for classroom instruction ( Longo and Orru, 2022 ) and is likely related to creativity ( Sun and Yao, 2012 ). Second, our current model is focused on individual creativity and does not explicitly include group work. If students work in groups, we need to copy the “person” and “process” plate in the model for every group member and draw additional arrows between the idea bundles of the group members, referring to their communication. Third, our model currently does not account for personal development over time. Such an extension would require a copy of the “person” plate for a next time step and drawing arrows from the creative product in the previous time step to the domain knowledge and creative affinity variables in the next time step.

Finally, we note that future work should validate our model beyond its utility as a distillation of the literature: In particular, empiric studies in education may reveal the actual strength of influence between variables; educational researchers should investigate whether the model can be used to assess instruction from the perspective of creativity; educators may validate the model's utility for teaching, and AIEd engineers may extend the model to a full-fledged computational model for practical applications. Such research does not only benefit our model but will deepen our understanding of creativity in education in its own right. As such, we hope that our model will form a symbiotic relationship with future research: being improved and revised by research, but also being useful as a conceptual tool to guide and support research.

Author contributions

JD and AK performed the original literature review and wrote the initial draft. BP performed the main revision work and distilled the initial graphical model. SK performed revision for text and model. KG and NP supervised the research and performed additional revision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant numbers PI 764/14-1 and PA 3460/2-1. The article processing charge was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – 491192747 and the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ Not promoted by Guilford (1950) , one should add; his paper already mentions that creativity research should investigate not only how to detect creative potential but how to ensure circumstances in which creative potential can be realized.

2. ^ For brevity, we subsume intelligence tests under personality tests, even though that is inaccurate.

Amabile, T. M., Mueller, J. S., Simpson, W. B., Hadley, C. N., Kramer, S. J., and Fleming, L. (2002). “Time pressure and creativity in organizations: a longitudinal field study,” in Harvard Business School Working Papers (Boston, MA), 1–30. doi: 10.5089/9781451852998.001*

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: a consensual assessment technique. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol . 43, 997. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.997*

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M. (2018). Creativity in Context: Update to the Social Psychology of Creativity . Milton Park: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429501234*

Baer, J. (2010). “Is creativity domain specific?” in The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity , eds J. C. Kaufman and R. J. Sternberg (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 321–341. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511763205.021*

Baer, M., and Oldham, G. R. (2006). The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. J. Appl. Psychol . 91, 963–970. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.963*

Baird, B., Smallwood, J., Mrazek, M. D., Kam, J. W. Y., Franklin, M. S., and Schooler, J. W. (2012). Inspired by distraction: mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychol. Sci . 23, 1117–1122. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446024*

Barber, D. (2012). Bayesian Reasoning and Machine Learning . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511804779

Beaty, R., and Johnson, D. (2021). Automating creativity assessment with SemDis: an open platform for computing semantic distance. Behav. Res. Methods 53, 757–780. doi: 10.3758/s13428-020-01453-w

Berns, S., and Colton, S. (2020). “Bridging generative deep learning and computational creativity,” in Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC'20) (Coimbra), 406–409.*

Google Scholar

Blanchard, N., Bixler, R., Joyce, T., and D'Mello, S. (2014). “Automated physiological-based detection of mind wandering during learning,” in Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS 2014) , eds S. Trausan-Matu, K. E. Boyer, M. Crosby, and K. Panourgia (Honolulu, HI), 55–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07221-0_7*

Boden, M. A. (1998). Creativity and artificial intelligence. Artif. Intell . 103, 347–356. doi: 10.1016/S0004-3702(98)00055-1*

Bower, M. (2011). Redesigning a web-conferencing environment to scaffold computing students' creative design processes. J. Educ. Technol. Soc . 14, 27–42.*

Buchmann, C. (2002). “Measuring family background in international studies of education: conceptual issues and methodological challenges,” in Methodological Advances in Cross-National Surveys of Educational Achievement , eds A. Porter and A. Gamoran (Washington, DC: National Academy Press), 197.*

Burnard, P. (2011). “Constructing assessment for creative learning,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Creative Learning , eds J. Sefton-Green, P.Thomson, K. Jones, and L. Bresler (London: Routledge), 140–149.*

Castillo-Vergara, M., Barrios Galleguillos, N., Jofre Cuello, L., Alvarez-Marin, A., and Acuna-Opazo, C. (2018). Does socioeconomic status influence student creativity? Think. Skills Creat . 29, 142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2018.07.005*

Clark, E., Ross, A. S., Tan, C., Ji, Y., and Smith, N. A. (2018). “Creative writing with a machine in the loop: case studies on slogans and stories,” in 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, IUI '18 (New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery), 329–340. doi: 10.1145/3172944.3172983

Colton, S., and Wiggins, G. A. (2012). “Computational creativity: the final frontier?” in Proceedings of the 20th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ECAI 2012) , 21–26.*

Cooper, D. G., Muldner, K., Arroyo, I., Woolf, B. P., and Burleson, W. (2010). “Ranking feature sets for emotion models used in classroom based intelligent tutoring systems,” in User Modeling, Adaptation, and Personalization , eds P. De Bra, A. Kobsa, and D. Chin (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 135–146. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-13470-8_14*

Cropley, A. (2020). Creativity-focused technology education in the age of industry 4.0. Creat. Res. J . 32, 184–191. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2020.1751546*

Cropley, A., and Cropley, D. (2008). Resolving the paradoxes of creativity: an extended phase model. Cambridge J. Educ . 38, 355–373. doi: 10.1080/03057640802286871*

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention . New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The Systems Model of Creativity . Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7*

Davidson, J. E., and Sternberg, R. J. (1984). The role of insight in intellectual giftedness. Gifted Child Q . 28, 58–64. doi: 10.1177/001698628402800203*

Davis, M. A. (2009). Understanding the relationship between mood and creativity: a meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process . 108, 25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.001*

Diedrich, J., Jauk, E., Silvia, P. J., Gredlein, J. M., Neubauer, A. C., and Benedek, M. (2018). Assessment of real-life creativity: the inventory of creative activities and achievements (ICAA). Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 12, 304–316. doi: 10.1037/aca0000137*

DiPaola, S., Gabora, L., and McCaig, G. (2018). Informing artificial intelligence generative techniques using cognitive theories of human creativity. Proc. Comput. Sci . 145, 158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.11.024*

Eysenck, H. J. (1993). Creativity and personality: suggestions for a theory. Psychol. Inq . 4, 147–178. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0403_1*

Faber, M., Bixler, R., and D?Mello, S. K. (2018). An automated behavioral measure of mind wandering during computerized reading. Behav. Res . 50, 134–150. doi: 10.3758/s13428-017-0857-y*

George, J. M., and Zhou, J. (2002). Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don't: the role of context and clarity of feelings. J. Appl. Psychol . 87, 687–697. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.687*

Greiff, S., Niepel, C., Scherer, R., and Martin, R. (2016). Understanding students' performance in a computer-based assessment of complex problem solving: an analysis of behavioral data from computer-generated log files. Comput. Hum. Behav .61, 36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.095*

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. Am. Psychol . 5, 444–454. doi: 10.1037/h0063487*

Guilford, J. P. (1967). The Nature of Human Intelligence . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.*

Hayes, J. R. (1989). “Cognitive processes in creativity,” in Handbook of Creativity , eds J. A. Glover, R. R. Ronning, and C. R. Reynolds (Boston, MA: Springer US), 135–145. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-5356-1_7*

Hennessey, B. A., Amabile, T. M., and Mueller, J. S. (2011). “Consensual Assessment,” in Encyclopedia of Creativity, 2nd Edn eds Marc A Runco and Steven R. Pritzker (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 253–260. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-375038-9.00046-7*

Henriksen, D., Mishra, P., and Fisser, P. (2016). Infusing creativity and technology in 21st century education: a systemic view for change. Educ. Technol. Soc . 19, 27–37.

Hershkovitz, A., Sitman, R., Israel-Fishelson, R., Eguiluz, A., Garaizar, P., and Guenaga, M. (2019). Creativity in the acquisition of computational thinking. Interact. Learn. Environ . 27, 628–644. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2019.1610451*

Hocevar, D. (1979). “The development of the creative behavior inventory (CBI),” in Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Rocky Mountain Psychological Association (Denver, CO), 1–14.*

Horrocks, I., and Patel-Schneider, P. F. (2004). “A proposal for an owl rules language,” in Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW '04) (New York, NY), 723–731. doi: 10.1145/988672.988771

Huang, C.-C., Yeh, T.-K., Li, T.-Y., and Chang, C.-Y. (2010). The idea storming cube: evaluating the effects of using game and computer agent to support divergent thinking. J. Educ. Technol. Soc . 13, 180–191.*

Hwang, W.-Y., Chen, N.-S., Dung, J.-J., and Yang, Y.-L. (2007). Multiple representation skills and creativity effects on mathematical problem solving using a multimedia whiteboard system. J. Educ. Technol. Soc . 10, 191–212.*

Iqbal, S. T., Zheng, X. S., and Bailey, B. P. (2004). “Task-evoked pupillary response to mental workload in human-computer interaction,” in Proceedings of the 2004 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI04) , eds E. Dykstra-Erickson and M. Tscheligi, 1477–1480. doi: 10.1145/985921.986094*

Israel-Fishelson, R., Hershkovitz, A., Eguiluz, A., Garaizar, P., and Guenaga, M. (2021). A log-based analysis of the associations between creativity and computational thinking. J. Educ. Comput. Res . 59, 926–959. doi: 10.1177/0735633120973429*