- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Special Issues

- Virtual Issues

- Trending Articles

- IMPACT Content

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Author Resources

- Read & Publish

- Why Publish with JOPE?

- About the Journal of Philosophy of Education

- About The Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- MORAL PRINCIPLES: HELP OR HINDRANCE?

- MORAL PERCEPTION AND THE NEED FOR ATTENTION

- EMOTIONS AND MORAL SENSITIVITY

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- < Previous

Moral sensitivity: The central question of moral education

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Roger Marples, Moral sensitivity: The central question of moral education, Journal of Philosophy of Education , Volume 56, Issue 2, April 2022, Pages 342–355, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12633

- Permissions Icon Permissions

There is more to the moral life than mere adherence to a set of moral rules or principles to which the moral agent has autonomously subscribed. Something more fundamental is required for moral personhood, requiring explication in terms of ‘sensitive perception’ in relation to the particularities pertaining to any given set of circumstances meriting a moral response. The article addresses the importance of accuracy of conceptualisation, the need for attentiveness and sensitivity in the identification of moral salience, and concludes with the role of affect in this enterprise.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1467-9752

- Print ISSN 0309-8249

- Copyright © 2024 Philosophy of Education Society of Great Britain

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Advertisers

- Agents and Vendors

- Book Authors and Editors

- Booksellers / Media / Review Copies

- Librarians and Consortia

- Journal Authors and Editors

- Licensing and Subsidiary Rights

- Mathematics Authors and Editors

- Prospective Journals

- Scholarly Publishing Collective

- Explore Subjects

- Authors and Editors

- Society Members and Officers

- Prospective Societies

Open Access

- Job Opportunities

Debating Moral Education

Rethinking the role of the modern university.

Editor(s): Elizabeth Kiss , J. Peter Euben

Contributor(s): Noah Pickus , Elizabeth Kiss , Julie A. Reuben , Stanley Fish , Stanley Hauerwas , Elizabeth Spelman , Wilson Carey McWilliams , Lawrence Blum , James Bernard Murphy , Patchen Markell , George Shulman , Romand Coles , David . Hoekema , J. Donald Moon , Ruth W. Grant , Michael Gillespie , J. Peter Euben , Susan McWilliams

Subjects Pedagogy and Higher Education , Religious Studies , Politics > Political Theory

“ Debating Moral Education is a provocative and productive collection, which can positively impact the teaching and practice of moral education in the academy. While the authors are not of one voice on the subject, their thorough and passionate responses evoke deeper thought about the practice of moral education. Their lively conversation invites the participation of a wide audience of faculty, administrators, student affairs professionals, as well as the larger community. Many of these essays can also provide students with an opening to think about their own education and the role of the university.” — Matthew Maruggi, Teaching Theology and Religion

“ Debating Moral Education makes an indispensable contribution to moral education’s expanding bibliography.” — Jerry Pattengale, Books & Culture

“[An] engaging collection of essays by prominent scholars from religious, philosophical, and political backgrounds who debate the role of morality and ethics in the university. . . . Readers who begin this book can easily imagine themselves caught up in the unfolding, urgent, but friendly controversy of scholarly opinions regarding moral education.” — Lois Calian Trautvetter, Review of Higher Education

“Elizabeth Kiss and Peter Euben's Debating Moral Education brings together an impressive group of philosophers, political scientists and, in the case of Stanley Hauerwas, a theologian to discuss these matters. . . . The strength of the volume lies in the editors' determination to give voice to a range of different views and leave readers (free) to pick their own way through.” — J. Mark Halstead, Times Higher Education

“This is an excellent book, offering a great deal for many educators globally. It is timely, articulate and thought-provoking.” — Joseph Zajda, International Review of Education

“Those interested in its topic would be well advised to read this book. . . .The contributors draw from an impressive variety of fields of inquiry to support their positions on both sides of the question. The cumulative effect is a nuanced overview of many considerations important to the debate, illuminated by thinkers as diverse as Socrates, Plato, Dewey, Marx, Bloch,Nietzsche, Nussbaum, Arendt and Foucault.” — Daniel Vokey, Journal of Moral Education

“Recently colleges and universities that had for many years distanced themselves from their students’ growth as moral agents have begun taking this aspect of higher education very seriously. In this book they will find the issues laid out with admirable clarity and the fresh ideas and approaches they need to do the work well.” — W. Robert Connor, Professor of Classics, Emeritus, Princeton University

“Some of the best scholars in the field engage in the contemporary debate over the nature and scope of moral education, especially in American universities. Anyone wishing to trace this complex but fascinating debate would do well to read Debating Moral Education .” — Terence Ball, author of Reappraising Political Theory

“This excellent collection of essays provides a timely and thoughtful account of the perils and prospects of moral education in our time. The contributors are prominent moral philosophers, political theorists, and civic educators whose different perspectives—some enthusiastic, others wary—make for a lively and reflective volume. The issues raised in this important book will interest and challenge students and educators in a context defined by related debates over academic freedom, intelligent design, and the ever-present culture wars.” — James Farr, University of Minnesota

- Buy the e-book: Amazon Kindle Apple iBooks Barnes & Noble nook Google Play Kobo

- Author/Editor Bios

- Table of Contents

- Additional Information

Elizabeth Kiss is President of Agnes Scott College. J. Peter Euben is Professor of Political Science, Research Professor of Classical Studies, and Kenan Distinguished Faculty Fellow in Ethics at Duke University. He is the author of Platonic Noise , Corrupting Youth , and The Tragedy of Political Theory , and an editor of Athenian Political Thought and the Reconstruction of American Democracy .

If you are requesting permission to photocopy material for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com;

If the Copyright Clearance Center cannot grant permission, you may request permission from our Copyrights & Permissions Manager (use Contact Information listed below).

If you are requesting permission to reprint DUP material (journal or book selection) in another book or in any other format, contact our Copyrights & Permissions Manager (use Contact Information listed below).

Many images/art used in material copyrighted by Duke University Press are controlled, not by the Press, but by the owner of the image. Please check the credit line adjacent to the illustration, as well as the front and back matter of the book for a list of credits. You must obtain permission directly from the owner of the image. Occasionally, Duke University Press controls the rights to maps or other drawings. Please direct permission requests for these images to [email protected] . For book covers to accompany reviews, please contact the publicity department .

If you're interested in a Duke University Press book for subsidiary rights/translations, please contact [email protected] . Include the book title/author, rights sought, and estimated print run.

Instructions for requesting an electronic text on behalf of a student with disabilities are available here .

Email: [email protected] Email contact for coursepacks: [email protected] Fax: 919-688-4574 Mail: Duke University Press Rights and Permissions 905 W. Main Street Suite 18B Durham, NC 27701

1. Author's name. If book has an editor that is different from the article author, include editor's name also. 2. Title of the journal article or book chapter and title of journal or title of book 3. Page numbers (if excerpting, provide specifics) For coursepacks, please also note: The number of copies requested, the school and professor requesting For reprints and subsidiary rights, please also note: Your volume title, publication date, publisher, print run, page count, rights sought

This book is subject to the standard Duke University Press rights and permissions.

- read Michael Allen Gillespie's essay on the NCAA Men's Basketball championship

- David Brooks cites Michael Allen Gillespie in his essay "The Sporting Mind" in the February 4, 2010 issue of The New York Times

- Bk Cover Image Full

- Also Viewed

- Also Purchased

On Being Included

The Problem with Work

Vibrant Matter

The American Colonial State in the Philippines

Necropolitics

Conspiracy/Theory

On Decoloniality

Israel/Palestine and the Queer International

Bad Education

Making the World Global

Pikachu's Global Adventure

Poor Queer Studies

99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best moral development topic ideas & essay examples, 📌 simple & easy moral development essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on moral development, ❓ questions about moral development.

- Kohlberg’s Moral Development Concept This is continuous because, in every stage of the moral development, the moral reasoning changes to become increasingly complex over the years.

- Aggression Development: Piaget’s Moral Development Theory It is the first stage of moral development in which a child views the rules of authority figures as revered and unchangeable. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- School Bullying and Moral Development The middle childhood is marked by the development of basic literacy skills and understanding of other people’s behavior that would be crucial in creating effective later social cognitions. Therefore, addressing bullying in schools requires strategies […]

- Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development in Justice System Burglars, whose predominant level of morality is conventional, tend to consider the opinion of the society on their actions. Kohlberg’s stages of moral development help to identify the problems and find solutions to them.

- Pulp Fiction: Moral Development of American Life and Interests Quentin Tarantino introduces his Pulp Fiction by means of several scenes which have a certain sequence: proper enlightenment, strong and certain camera movements and shots, focus on some details and complete ignorance of the others, […]

- Moral Development in Early Childhood The only point to be poorly addressed in this discussion is the options for assessing values in young children and the worth of this task.

- The Moral Development of Children Child development Rev 2000; 71: 1033 1048.’ moral development/moral reasoning which is an important aspect of cognitive development of children has been studied very thoroughly with evidence-based explanations from the work of many psychologists based […]

- Moral Development and Bullying in Children The understanding of moral development following the theories of Kohlberg and Gilligan can provide useful solutions to eliminating bullying in American schools.

- Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development Dilemma According to Kohlberg, justice is the driver of the process of moral development. Therefore, the early Christians should have continued to practice Christianity regardless of the persecution.

- Moral Development: Emotion and Moral Behavior More moral emotion is guilt as compared to shame because those who are shamed are relatively unlikely to rectify as compared to the guilty people.

- Adolescent Moral Development in the United States Adolescents who are in this stage begin to acknowledge and understand the beliefs embraced in their societies. The absence of a moral compass can make it hard for adolescents in this country to realize their […]

- Moral Development Theory Review by Kohlberg and Hersh Overall, the main strength of this article is that the authors present a comprehensive overview of theories that can throw light on the moral development of a person.

- Moral Development and Aggression The reason is that children conclude about the acceptability of aggressive or violent behaviors with reference to what they see and hear in their family and community.

- Moral Development: Kohlberg’s Dilemmas Another characteristic of this stage of moral speculation is that the speculators mostly view the dilemma through the lens of consequences it might result in and engage them in a direct or indirect manner.

- Chinese Foundations for Moral Education and Character Development In Chinese Foundations for Moral Education and Character Development, Vincent Shen and his team make a wonderful attempt to describe how rich and captivating Chinese cultural heritage may be, how considerable knowledge for this country […]

- Cognitive, Psychosocial, Psychosexual and Moral Development This, he goes ahead to explain that it is at this very stage that children learn to be self sufficient in terms of taking themselves to the bathroom, feeding and even walking.

- Moral Development and Ethical Concepts The two concepts are important in the promotion of ethical culture within the organizations, the organizations’ performance and the much needed moral and financial support from the organization’s stakeholders and the public in general.

- Empathy and Moral Development For a manager to have empathy, he/she has to be able to interact freely with the employees, and spend time with them at their work places. This makes the employees to know that what they […]

- Cognitive or Moral Development This is the second of the four Piagetian stages of development and the children begin to make use of words, pictures and diagrams to represent their sentiments.

- Moral Intelligence Development In the course of his day-to-day banking activities, I realized that the general manager used to work in line with the banking rules and regulations to the letter.

- An Evaluation of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development and How It Could Be Applied to Grade School It is the purpose of this essay to summarize Kohlberg’s theory, and thereafter analyze how the theory can be applied to grade a school.

- Moral Development and Its Relation to Psychology These stages reveal the individual’s moral orientation expanding his/her experiences and perceptions of the world with regard to the cognitive development of a person admitting this expansion. The views of Piaget and Kohlberg differ in […]

- The Impact Of Television On The Moral Development

- Influences in Moral Development

- The Influence of Parenting in the Moral Development of a Child

- The Effect of Cognitive Moral Development on Honesty in Managerial Reporting

- Huckleberry Finn Moral Development & Changes

- Responsibility For Moral Development In Children

- Morality and Responsibility – Moral Development in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

- Moral Development And Gender Care Theories

- Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg on Moral Development

- Kaylee Georgeoff’s Moral Development According To Lawrence Kohlberg

- The Criticisms Of Kohlberg’s Moral Development Stages

- The Ethics Of The Organization ‘s Moral Development

- Lawrence Kohlbergs Stages Of Moral Development

- Personal, Psychosocial, And Moral Development Theories

- Moral Development and Importance of Moral Reasoning

- Integrating Care and Justice: Moral Development

- Moral Development in Youth Sport

- Kohlberg’s Theory on Moral Development: New Field of Study in Western Science

- The Definition of Ethics and the Foundation of Moral Development

- Kohleberg´s Philosophy of Moral Development

- Stealing and Moral Reasoning: Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

- Plagiarism and Moral Development

- Kohlberg and Moral Development Between the Ages of One and Six

- Kohlberg’s 6 Stages of Cognitive Moral Development and Model Suggestions

- Moral Development and Narcissism of Private and Public University Business Students

- The Effect of the Transcendental Meditation TM Technique on Moral Development

- Psychology Stages of Moral Development

- The Link Between Friendship and Moral Development

- Moral Development And Gender Related Reasoning Styles

- Moral Development in the Adventures of Huckleberry Fin by Mark Twain

- Moral Development : The Way Someone Thinks, Feels, And Behaves

- The Effect of Nuclear and Joint Family Systems on the Moral Development: A Gender Based Analysis

- Moral Development and Dilemmas of Huck in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- Teaching Moral Development To School Children In The Caribbean

- History and Moral Development of Mental Health Treatment and Involuntary Commitment

- Incorporating Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development into the Justice System

- Moral Development Theory in Boys and Girls: Kohlberg and Gilligan

- The Different Levels in Moral Development

- Moral Development Of Six-Year-Old Children

- Portrait of Erik Erikson’s Developmental Theory and Kohlberg’s Model of Moral Development

- Moral Development Of Jem And Scout In To Kill A Mockingbird

- Moral Development and Aggression in Children

- The Idea Of Moral Development In The Novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn By Mark Twain

- The Influence of Media Technology on the Moral Development and Self-Concept of Youth

- The Character of Tituba in Lawrence Kohlberg’s Different Stages of Moral Development

- Multiple Intelligences, Metacognition And Moral Development

- Moral Development : The Foundation Of Ethical Behavior

- Can Moral Development Lead To Upward Influence Behavior?

- What Are the Five Stages of Moral Development?

- What Is an Example of Moral Development?

- What Is Moral Development, and Why Is It Important?

- What Are the Three Levels of Moral Development?

- What Are the Six Stages of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development?

- What Is Moral Development in a Child?

- What Is Moral Development, According to Kohlberg?

- How Many Levels of Moral Development Are There?

- Why Is Moral Development Significant in Early Childhood?

- What Factors Play Into Moral Development?

- What Is Moral Development in Adolescence?

- What Are the Characteristics of Moral Development?

- Why Is Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development Critical?

- What Characteristics Are Essential for Healthy Moral Development?

- How Do Parents Affect a Child’s Moral Development?

- What Is the Most Important Influence on a Child’s Moral Development?

- What Is the Role of the Teacher in Moral Development?

- Why Is Moral Development Significant?

- What Is Meant by Moral Development?

- Why Is Research on Moral Development Necessary?

- What Is the Study of Moral Development?

- What Factors Affect Moral Development?

- Which of the Following Researchers Studied Moral Development?

- How Did Kohlberg Research Moral Development?

- What Is Carol Gilligan’s Theory of Moral Development?

- How Did Piaget Study Moral Development?

- What Was Gilligan’s Main Criticism of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development?

- What Is the Difference Between Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development and Gilligan’s Theory of Moral Evolution and Gender?

- Why Do Different Scholars Criticize Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 26). 99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/

"99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

- Developmental Psychology Essay Ideas

- Morality Research Ideas

- Cognitive Development Essay Ideas

- Social Responsibility Topics

- Emotional Development Questions

- Human Development Research Ideas

- Ethnicity Research Topics

- Organization Development Research Ideas

- Personality Development Ideas

- Professional Development Research Ideas

- Respect Essay Topics

- Ethics Ideas

- Lifespan Development Essay Titles

- Social Development Essay Topics

- Ethical Dilemma Titles

Advertisement

Moral Disagreement and Moral Education: What’s the Problem?

- Open access

- Published: 05 June 2023

- Volume 27 , pages 5–24, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Dominik Balg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2078-9312 1

1413 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Although initially plausible, the view that moral education should aim at the transmission of moral knowledge has been subject to severe criticism. In this context, one particularly prominent line of argumentation rests on the empirical observation that moral questions are subject to widespread and robust disagreement. In this paper, I would like to discuss the implications of moral disagreement for the goals of moral education in more detail. I will start by laying out the empirical and philosophical assumptions behind the idea that widespread and robust moral disagreement undermines the prospects of transmitting moral knowledge in educational settings. Having thus provided a specific interpretation of the epistemic dynamics behind this so-called ‘challenge of disagreement’, I will proceed by discussing its didactical implications. More specifically, I will defend two claims: first, I will argue that the challenge of disagreement is not an effective challenge, because it undermines the possibility of knowledge transfer only with respect to a limited set of moral propositions. Second, I will argue that the challenge of disagreement is not a specific challenge, because the epistemically destructive effects of moral disagreement also pose a challenge for other prominent accounts of moral education that were originally proposed as promising alternatives to knowledge transmission accounts. If convincing, my arguments show that knowledge transmission accounts of moral education are in a much better position than is usually expected to incorporate the fact that moral questions are notoriously controversial.

Similar content being viewed by others

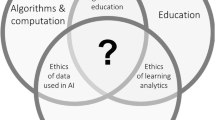

Evolution and Revolution in Artificial Intelligence in Education

Ido Roll & Ruth Wylie

Ethics of AI in Education: Towards a Community-Wide Framework

Wayne Holmes, Kaska Porayska-Pomsta, … Kenneth R. Koedinger

Discourses of artificial intelligence in higher education: a critical literature review

Margaret Bearman, Juliana Ryan & Rola Ajjawi

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

What are the goals of moral education? One possible answer to this question is the following: moral education is simply education with respect to a specific topic. Accordingly, the goals of moral education are simply general educational goals that are applied to this specific topic . Viewed from this perspective, there is nothing special about moral education. For example, let’s assume that the transmission of knowledge is one important general goal of education. Given this, we could simply apply this goal to a variety of specific educational domains. One important goal of science education would be the transmission of scientific knowledge. One important goal of history education would be the transmission of historical knowledge. And one important goal of moral education would be the transmission of moral knowledge. Footnote 1

Although initially intuitive, many if not most authors within the didactics of philosophy and the philosophy of education will likely reject the above idea. One main reason for this reluctance to regard the transmission of moral knowledge as an important goal of moral education is the worry that – given widespread philosophical disagreement about moral questions – such transmission is simply impossible: if all or most moral questions are subject to widespread and robust disagreement, there won’t be much transferable moral knowledge to begin with, so that any attempt to directly transmit specific moral beliefs would simply amount to indoctrination (Hand 2018 , 1).

In this paper, I would like to discuss this challenge of disagreement in more detail. More specifically, I will defend two claims. First, I will argue that the challenge of disagreement is not an effective challenge, because it undermines the possibility of knowledge transfer only with respect to a limited set of moral propositions. Second, I will argue that the challenge of disagreement is not a specific challenge for knowledge transmission accounts of moral education, because the epistemically destructive effects of moral disagreement also pose a challenge for other prominent accounts of moral education. I will proceed as follows. In Section 2 , I will start by laying out the empirical and philosophical assumptions behind the challenge of disagreement, conceived as a specific epistemic challenge for moral knowledge transmission, in more detail. Having thus provided a specific interpretation of the epistemic dynamics behind the challenge of disagreement, I will proceed by discussing its didactical implications in more detail. In Section 3 , I will critically discuss the efficacy of the challenge of disagreement, arguing that it doesn’t undermine the possibility of moral knowledge transmission in general, but only with respect to specific first-order moral propositions that are sufficiently controversial among professional ethicists. In Section 4 , I will discuss the accuracy of the challenge of disagreement, arguing that it also undermines other dimensions of moral education that were originally proposed as promising alternatives to moral knowledge transmission, such as teaching moral reasoning skills or enabling students to participate in moral discourse. Section 5 will sum up the main results.

If convincing, my arguments show that knowledge transmission accounts of moral education are not just better than widely assumed, but actually do better than their main competitors in dealing with the educational implications of moral disagreement. However, I want to stay explicitly neutral on the question of whether knowledge transmission accounts are superior overall to alternative accounts of moral education – or whether they are even feasible at all. Besides the problem of disagreement, there are a number of further challenges that knowledge transmission accounts of moral education must face. Most importantly, these accounts seem to rest on a number of controversial epistemological assumptions – e.g. assumptions about the existence of moral experts or the possibility of moral testimony. While I am personally optimistic that many of the various objections lurking in this context can be successfully met, any detailed discussion of them would clearly exceed the scope of this paper. What’s more, even if we assume that knowledge transmission accounts of moral education are epistemically defensible, there will still be political and pedagogical challenges to the idea that moral knowledge should be directly transmitted in educational contexts (for an overview, see e.g. Giesinger 2021 ). Accordingly, all I want to argue for in the following is the comparatively narrow claim that the specific phenomenon of moral disagreement is not so much a problem for knowledge transmission accounts as it is for competing accounts of moral education. While clearly being comparatively narrow, this claim still has bite: in fact, the challenge of disagreement is often seen as one of the most pressing problems for moral education in the relevant literature (Hand 2018 , p. 1). Given that, a satisfactory solution of this specific challenge would already lead to a significant shift in the dialectical landscape.

Before I proceed, however, and in order to avoid misunderstandings, I would like to make an important conceptual clarification. Especially for experienced educators, the idea that „knowledge transmission “ should be a goal of any kind of education might already raise some concerns. To better understand this idea, it is helpful to distinguish between an epistemological, a psychological and a didactical reading of “knowledge transmission”. According to the epistemological reading, this notion only refers to a specific epistemic relation between the input beliefs and the output beliefs of educational transfer processes. According to the psychological reading, the transmission of knowledge also includes the transmission of psychological features that concern the cognitive embeddedness of beliefs. According to the didactical reading, “transmission of knowledge “ refers to top-down educational settings where instructors simply impart knowledge to their students instead of enabling them to acquire the relevant insights on their own. While the educational importance of knowledge transmission in the epistemological sense has been widely acknowledged (see e.g. Goldman 2006 , p.11)—in fact, it is epistemologically uncontroversial that most of what we know we only know on the basis of other people’s knowledge (see e.g. Goldberg 2010 )—knowledge transmission in the psychological and didactical sense is usually judged to be pedagogically illegitimate or even impossible. Footnote 2 In this paper, whenever I speak of „knowledge transmission “, I speak of knowledge transmission in the epistemological sense. Aiming at the transmission of knowledge in this sense in educational contexts is both compatible with psychological findings to the effect that the acquisition of knowledge is rather a result of individual construction than of passive perception and with the didactical demand that students should acquire insights on their own (Hand 2018 , 38).

2 The Epistemic Dynamics behind the Challenge of Disagreement

At first glance, the idea that the pervasiveness of moral disagreement directly speaks against the possibility of educational transfers of moral knowledge seems pretty straightforward. However, upon closer inspection, it is at least not obvious why and how the controversiality of moral issues is supposed to undermine educational transfer processes. After all, one might argue, people disagree about almost everything – and still, at least in domains like mathematics, science, history or geography, educational transfer of substantive, domain-specific insights seems to be perfectly legitimate. So why should the mere fact that moral questions are notoriously controversial pose a specific problem for the educational transmission of moral knowledge?

To answer this question, I would like to provide a deeper analysis of the challenge of disagreement in this section. In order to get a better grasp of the philosophical details behind this challenge, it is helpful to cite one of its proponents in a little more detail. So, to begin with, consider the following passage from Kirsten Meyer (Meyer 2011 , p. 229 f., my translation):

Let‘s suppose that there are in fact specific moral principles whose correctness we are able to grasp and upon which we can act. Even against the background of this assumption, there remains an important problem for moral education. After all, it is still not clear at all which moral principles are correct – and accordingly, which principles should be taught in educational settings. One simple reason why moral education can‘t be aimed at the transmission of moral principles is that such principles are controversial within academic philosophy. If moral education was about transferring knowledge of correct moral principles, one would first need to know which exact principles these should be. […] Which principles should be taught in philosophy classes in order to enable students to act morally? Should we advocate for a kantian or a utilitarian position? Do we have to wait for the underlying philosophical disputes to be settled before we can answer this question? […] When we try to identify the proper goals of moral education […], we encounter […] several open questions. A satisfying answer to these questions would require a settlement of century-old philosophical disputes. And such a settlement is not to be expected.

Against the background of this passage, the dialectical profile of the challenge of disagreement already becomes clearer. Most importantly, it becomes clear that the challenge of disagreement is a specific objection against knowledge transmission accounts of moral education that already rests on a number of specific assumptions: first of all, the basic idea behind this challenge is not that it is in principle impossible to transfer moral knowledge in educational settings – e.g. because there aren ‘t any moral principles, or because such principles aren’t truth-apt. Rather, the idea is that in light of widespread moral disagreement, it isn ‘t clear which moral principles should be transferred in educational settings. In this way, the challenge of disagreement already presupposes the possibility of moral knowledge. And in fact, this shouldn’t come as a surprise: for instance, let ‘s suppose that a fundamentally pessimistic view on the possibility of moral knowledge –e.g. moral nihilism or moral non-cognitivism—was correct. In such a case, it seems that whether moral questions are in fact controversial or not would be completely irrelevant to the possibility of moral knowledge transfer, because even if everyone agreed on the same moral verdicts, we still wouldn ‘t be in a position to transfer any moral knowledge in educational settings. The challenge of disagreement is supposed to show that crucial features of moral knowledge transfers are effectively undermined by the fact that moral questions are notoriously controversial. But if there is nothing to be undermined in the first place, this idea seems like a nonstarter.

Furthermore, the challenge of disagreement explicitly presupposes that moral questions are controversial among professional philosophers and that it is exactly this kind of disagreement that undermines the possibility of moral knowledge transfer. In fact, it is important to note that in the above passage, Meyer isn’t just talking about any old moral disagreement, but rather specifically refers to moral disagreements within academic philosophy , e.g. between kantians and utilitarians. But what’s so special about moral disagreements between academic philosophers? The idea seems to be here that – just as educational knowledge transfer in other domains – educational transfer of moral knowledge should be informed by the relevant experts. However, given that even the experts disagree about moral questions, we are in no position to decide which moral principles should be taught in educational settings. In what follows, I would like to discuss these assumptions behind the challenge of disagreement in a little more detail in order to provide a more fine-grained understanding of the prima facie plausible idea that widespread moral disagreement poses a fundamental problem for educational transfer of moral knowledge.

Let ‘s start with the assumption that it is in principle possible to acquire moral knowledge. As we have seen, this assumption is implicitly presupposed by the challenge of disagreement, because if it was impossible to acquire any moral knowledge in the first place, it would be completely irrelevant whether moral questions are in fact controversial or not. Given how extensively pessimistic views on the possibility of moral knowledge have been discussed in the philosophical literature, this already seems like a substantive and potentially problematic metaethical commitment. However, there are several things to be said to soften the worry that the challenge of disagreement can simply be rejected by appealing to some form of metaethical pessimism. First of all, the assumption that we are in principle in a position to acquire moral knowledge doesn ‘t just underlie the challenge of disagreement, but also much of our everyday moral practice: at least from a pretheoretical perspective, it seems overwhelmingly plausible that we can and actually do have a lot of moral knowledge. For example, most people would agree that I know that torturing puppies out of boredom is morally wrong, or that I ‘m not morally obliged to compliment random strangers on their outfits. Given this, the fact that the challenge of disagreement questions the legitimacy of moral knowledge transfer on the basis of critical considerations concerning the scope —and not the mere possibility – of moral knowledge seems to be a strength and not a weakness.

Furthermore, and more importantly, the assumption that it is in principle possible to acquire moral knowledge is obviously already presupposed by the very target of the challenge of disagreement – i.e. by knowledge transmission accounts of moral education. Proponents of these accounts cannot defend themselves against the challenge of disagreement on the basis of pessimistic views on the possibility of moral knowledge without undermining their own position. Given this, any critique of the challenge of disagreement that points to the optimistic presuppositions that this challenge implies with respect to the possibility of moral knowledge seems to be at least dialectically ineffective.

Notably, the same is true with respect to the second assumption behind the challenge of disagreement that has been identified above – the assumption that moral questions are controversial among professional philosophers and that it is exactly this kind of disagreement that undermines the possibility of moral knowledge transfer. One rather obvious problem with this assumption is that it seems to presuppose that academic philosophers enjoy some kind of moral expertise and are thus in a privileged position to inform educational transfer processes. This presupposition will probably strike many people as hopelessly elitist (Driver 2006 ) – but again, it is plausibly already presupposed by knowledge transmission accounts of moral education. Footnote 3 For as already illustrated at the outset of this paper, the very idea behind these accounts seems to be that there is nothing special about moral education: just as in other domains, educational processes in the moral domain should be aimed at the transmission of domain-specific knowledge that is provided by the relevant academic community. Given this, proponents of these accounts cannot defend themselves against the challenge of disagreement by rejecting its presuppositions concerning the possibility of moral expertise without undermining their own position.

So let‘s suppose that professional philosophers can plausibly be considered as moral experts. Is it true that moral questions are controversial among professional philosophers? And how exactly are these disagreements supposed to undermine the possibility of educational knowledge transfer? The first of these questions is clearly an empirical one. However, it is surprisingly hard to answer. One obvious difficulty is to identify the relevant group of people in the first place – what does it even mean to be a philosopher? And is every philosopher an expert on any philosophical question? Footnote 4 Furthermore, many widespread views on the amount of controversy within academic philosophy will likely be distorted by naive misconceptions and prejudices which portray philosophy as a messy and hopelessly unoriented endeavor.

Despite all these difficulties and biases, there has been one notable attempt to get a clearer picture of the amount and distribution of disagreement among professional philosophers that has received a lot of attention within the philosophical community. In their much-discussed PhilPapers Surveys, David Chalmers and David Bourget regularly survey professional philosophers in order to help uncover their views on key philosophical questions. The results of this project allow for a more justified estimation of the degree of moral disagreement among experts. For example, considering only the answers of respondents who are regular faculty members in BA-granting philosophy departments, and who named “normative ethics” as their area of specialization, the 2020 PhilPapers Survey revealed a fundamental disagreement about which ethical theory is correct (for the following numbers, see Bourget and Chalmers 2021 ). While 27.27% accept or lean toward deontology, 20.45% accept or lean toward consequentialism. 17.42% accept or lean toward virtue ethics and 0.76% are agnostic or undecided. In fact, it looks like the degree of controversy has even increased over the last few years. For, in the preceding PhilPapers Survey of 2009, 35.25% accepted or leaned toward deontology, 23.02% accepted or leaned toward consequentialism, and 12.23% accepted or leaned toward virtue ethics (Bourget and Chalmers 2014 ). While it is also important to keep in mind that (i) conflicting ethical theories don ‘t necessarily yield conflicting verdicts with respect to all or even most concrete moral questions and (ii) proponents of the same ethical theory regularly end up with conflicting applications of this theory, these numbers clearly justify the assumption that a lot of concrete moral issues will be highly controversial among the relevant experts.

Why is such a high degree of controversy among experts a serious problem for moral knowledge transmission? In what follows, I would like to provide a specific interpretation of the epistemic dynamics behind the idea that widespread expert disagreement undermines the possibility of educational knowledge transfer. This interpretation is directly informed by the recent debate about the epistemic implications of disagreement within social epistemology. One important insight from this debate is that the epistemic implications of a situation of disagreement crucially depend on the respective levels of competence of the disagreeing parties (see e.g. Kelly 2005 , p. 168). In this context, one specific constellation of cases that have received a lot of attention within the epistemological literature are disagreement situations where the disagreeing parties are epistemic peers , which means that the disagreeing parties have access to the same (or equally good) evidence and are equally competent in assessing this evidence (Christensen 2009 , pp. 756–757). Footnote 5 One reason why such cases have received so much attention within the epistemological literature is that they apparently have profound epistemic implications. More specifically, peer disagreements seem to make it epistemically irrational to hold on to one’s beliefs. For, whenever a person finds herself in disagreement with someone she considers her epistemic peer, she is rationally required to revise her original position. To illustrate this point, many authors refer to the so-called Restaurant Case which was originally developed by Christensen ( 2007 ). The case goes as follows (ibid., p. 193):

Suppose that five of us go out to dinner. It’s time to pay the check, so the question we’re interested in is how much we each owe. We can all see the bill total clearly, we all agree to give a 20% tip, and we further agree to split the whole cost evenly […]. I do the math in my head and become highly confident that our shares are $43 each. Meanwhile, my friend does the math in her head and becomes highly confident that our shares are $45 each. How should I react, upon learning of her belief? […] Let us suppose that my friend and I have a long history of eating out together and dividing the check in our heads, and that we’ve been equally successful in our arithmetic efforts: the vast majority of times, we agree; but when we disagree, she’s right as often as I am. So for the sort of epistemic endeavor under consideration, we are clearly peers. Suppose further that there is no special reason to think one of us particularly dull or sharp this evening—neither is especially tired or energetic, and neither has had significantly more wine or coffee.

In this case, many authors agree that the protagonist of the case is rationally required to give up her belief that the share is $43 each. Although there is some considerable disagreement about the relevant epistemic mechanics behind the rationally required response in such a case, and its exact doxastic nature, there is wide agreement that the described situation requires a state of substantive uncertainty (for a discussion, see e.g. Christensen 2007 ; Grundmann 2019 ; Kelly 2011 ). While this verdict and its generalization over all cases of peer disagreement can – and actually has been (see e.g. Kelly 2005 , 2011 ) – disputed, I will assume a conciliationist view in what follows, according to which situations of recognized peer disagreement undermine the epistemic status of the conflicting beliefs. Footnote 6 If we assume a conciliationist view on the significance of disagreement and combine this view with the above assumption about the degree of controversy among professional ethicists, it is easy to see how moral disagreements directly lead to a problem for the possibility of moral knowledge transfer. In situations where the relevant experts agree, disagreement with laypeople doesn’t pose a problem for such transfers, because it doesn’t undermine the experts’ knowledge, which is the ultimate source of the transfer processes. However, this is not the case in situations where the relevant experts disagree with each other . Footnote 7 For, if even the experts are (or should be) in a state of substantive uncertainty about the questions at issue, they are in no position to inform educational transfer processes. Footnote 8

I take the epistemic dynamics that has been delineated above to be the most plausible interpretation of the assumption that widespread expert disagreement undermines the possibility of moral knowledge transfer in educational settings. This interpretation doesn’t only neatly explain how the controversiality of moral questions might undermine the possibility of such knowledge transfers, but also sheds some light on the significance of agreement for moral education. Given the epistemic dynamics analyzed above, it gets clear that the absence of (sufficiently robust) disagreement among moral experts is a necessary condition for moral knowledge transfer. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that (sufficiently robust) agreement among moral experts is necessary for knowledge transfer. To see this, we just have to consider situations in which widespread agreement among experts is absent because only a very small fraction of the expert community has formed any beliefs on a given question, because this question hasn’t even been considered by most of their colleagues. If we assume that the beliefs of these few experts constitute knowledge, this status will in no way be undermined by the mere fact that other experts don’t agree. Furthermore, moral agreement is also not sufficient for moral knowledge transfer to be legitimate or even possible. For example, if we have good reasons to believe that a specific group of experts is fundamentally corrupt or misguided, the mere fact that they agree with each other should be of no relevance. In this way, the above interpretation doesn’t just help to better understand the challenge of disagreement, but also to locate its dialectical profile more accurately.

As we have seen in this section, the challenge of disagreement is a specific challenge for knowledge transmission accounts of moral education that rests on a number of specific empirical and philosophical assumptions. Some of these assumptions are more controversial than others, and some also have to be presupposed by proponents of knowledge transmission accounts. In what follows, I would not like to discuss these assumptions in more detail. Instead, I will simply accept them in order to make the challenge of disagreement as strong as possible. For as we will see, even if we accept all the assumptions that underlie the challenge of disagreement, it will still fail to pose a devastating problem for knowledge transmission accounts of moral education.

3 The Efficacy of the Challenge of Disagreement

In the last section, we saw why moral disagreement among professional ethicists poses a fundamental challenge to the possibility of moral knowledge transfer. That is, if professional ethicists are rationally required to adopt a stance of uncertainty with respect to moral questions, then they are in no position to present their moral views as knowledge to laypeople. In this section, I would like to critically discuss the efficacy of this challenge in more detail. Obviously, moral disagreement among professional ethicists has profound implications for the prospects of moral knowledge transfer. Yet, at the same time, it seems that it doesn’t undermine all transfer of moral knowledge, but only with respect to certain propositions . As we saw in the last section, the challenge of disagreement as it stands ultimately rests on the observation that professional ethicists disagree about which moral theory is correct (Meyer 2011 , pp. 229–230). Given this, professional ethicists will also disagree about any first-order moral question to which their competing moral theories imply conflicting answers, which in turn will undermine any possibility of knowledge transfer with respect to these questions. However, as I will argue in this section, there will also be a lot of moral questions which are subject to substantive agreement – and with respect to these questions, the challenge of disagreement remains ineffective.

At first glance, to someone who is familiar with the relevant literature, it might seem that this is something that has already been done. For example, in his paper ‚Towards a Theory of Moral Education ‘, Michael Hand, a prominent proponent of knowledge transmission accounts of moral education, writes (Hand 2014 , p. 528):

[…] Disagreement about the justificatory status of many moral standards […] looks set to be a salient feature of our moral landscape for the foreseeable future. But it would [be] premature to infer from this state of affairs that robustly justified moral standards are unavailable. From the fact that some moral standards have an uncertain justificatory status, it does not follow that all do; and from the fact that some arguments for moral subscription are dubious, it does not follow that all are. Perhaps, somewhere in the melee of controversial moral standards and arguments, there are at least some standards on which all are agreed and to which subscription is demonstrably justified. This, I think, is just how things are. Within the reasonable plurality of moral standards there is an identifiable subset to which more or less everyone subscribes and for which the reasons to subscribe are compelling. There is a very broad consensus in society on some basic moral prohibitions (on stealing, cheating, causing harm, etc.) and prescriptions (to treat others fairly, help those in need, keep one’s promises, etc.). And there is a familiar rational justification for those basic moral standards whose cogency is hard to dispute. It is, briefly, that moral standards are justified when their currency in society serves to ameliorate the ever-present risk in human social groups of breakdowns in cooperation and outbreaks of conflict.

To my mind, there are several problems with the above passage. First of all, it seems that Hand is talking about the wrong kind of justification. In order to constitute knowledge – and thus in order to qualify as eligible input for educational transfer processes – moral beliefs need to enjoy a sufficient degree of epistemic justification. In contrast, Hand seems to talk about pragmatic justification: his idea is that we have pragmatic reasons to accept certain standards because they help us to sustain social cooperation – and not that we have epistemic reasons that speak for the truth of these standards. Footnote 9

But even putting this worry to the side, it still seems that Hand is also looking for the wrong kind of agreement: just as in other domains, educational knowledge transfer in the moral domain should be, given that it is feasible at all, informed by the relevant experts – and not by the general public. Given this, the kind of agreement that is necessary for educational knowledge transfer to be epistemically legitimate is agreement among the relevant experts – because as we have seen, it is exactly this kind of agreement whose absence potentially undermines the epistemic status of expert beliefs.

To be clear, this should obviously be a rather significant distinction. It is easily conceivable that there are moral questions which are almost completely uncontroversial among the general public, but highly controversial among moral experts – and vice versa. Furthermore, there might also be moral questions which are sufficiently uncontroversial among the relevant experts, but which haven ‘t even been considered by the general public. So at least against the background of the specific interpretation of the challenge of disagreement that has been developed in the last section, it seems that the question that needs to be answered in order to assess the efficacy of this challenge is not whether there are any moral principles that are sufficiently uncontroversial among the general public to be pragmatically justified, but whether there are any moral principles that are sufficiently uncontroversial among the relevant experts to be epistemically justified. In what follows, I would like to make some steps towards answering this question.

3.1 (Meta-)Ethical Agreement

One first obvious source of moral expert agreement are (i) first-order moral questions with regard to which the competing moral theories yield the same result and (ii) meta-ethical questions. With respect to these questions, the possibility of moral knowledge transmission seems to be untouched by the challenge of disagreement. And in fact, the 2020 PhilPapers Survey seems to support this assumption. For example, of the 227 meta-ethicists who participated in this study, 77.53% accept or lean toward cognitivism, and 65.35% accept or lean toward moral realism. With respect to the latter issue, the degree of controversy has indeed significantly decreased in comparison to 2009 (Bourget and Chalmers 2021 ). Given the prevalence of student statements like “When it comes to moral questions, there is no true or false” and “There are no moral facts”, it seems that these results will be of some didactical significance. Footnote 10 Furthermore, there also seems to be some striking agreement with respect to first-order moral questions. For example, 86.11% of professional ethicists Footnote 11 agree that abortion is generally permissible, 74.13% Footnote 12 agree that capital punishment is impermissible, and 74.26% agree that human genetic engineering is permissible. Footnote 13 And again, given how controversial these issues usually are among students, this result should be of some didactical significance. To be fair, the above results in no way suffice to establish any significant number of moral insights that could then be readily taken as the proper input of knowledge transfer processes. One first problem is that the available empirical evidence is still pretty meager: what we would need is a substantial body of empirical data that enables us to get a clearer picture of the scope and degree of moral agreement among the relevant experts. A second problem is rather philosophical in nature. That is, even if we knew exactly what moral philosophers agree on, there would still be the question of how much agreement is needed to allow for the possibility of knowledge transmission. Or, to put it differently: what degree of expert disagreement suffices to undermine the possibility of knowledge transmission? While any answer to this question depends on a variety of complicated issues, epistemologists do agree that numbers matter (Grundmann 2013 ). Footnote 14 In a situation where only a small group of experts deviate from the majority view, this level of disagreement won’t suffice to undermine the possibility of knowledge transmission. At the same time, it is not easy to determine any specific threshold above which disagreement starts to have sufficiently destructive epistemic implications. Solving this philosophical problem would also be of great help for estimating the exact scope of the challenge of disagreement for moral knowledge transfer. Nevertheless, the above considerations do show that it would be premature to simply dismiss any attempt to legitimize moral knowledge transfer in educational settings by vaguely pointing to the alleged pervasiveness of moral disagreement. While professional ethicists certainly disagree about many moral questions, there will also be a considerable amount of moral agreement.

3.2 Agreement on Second-Order Principles

What I would like to argue for in the remainder of this section is that even in cases where professional ethicists disagree, the transmission of moral knowledge is still possible. To see how, let’s start with a simple thought experiment developed by Matheson ( 2021 , p. 15):

Trina is travelling for work. When she travels for work, her work covers her travel costs upon receiving the receipts. On this trip, Trina has a particularly bad travel experience. Her travel experience is so bad that the airlines refunds the price of her return trip. Upon returning home, Trina is thinking about whether she should still submit the original receipt to her work since the refund was intended as compensation for a bad experience. Trina talks things over with her good friend Lesley. Trina and Lesley disagree about what is morally permissible here even though they agree about all the non-moral facts relevant to the issue.

What should Trina do in this scenario? Intuitively, it seems that under the described circumstances, Trina shouldn’t submit the receipt to her work. Furthermore, it seems that Trina is also in a position to know that she shouldn’t do this and that she would therefore be blameworthy if she decided to submit the receipt anyway. At the same time, Trina doesn’t know whether submitting the receipt would be morally permissible. To describe this peculiar case in a slightly improper way, we could say that although Trina doesn’t know what to do, she knows what to do given that she doesn’t know what to do . How can we put this more precisely? At this point, it is helpful to distinguish between different levels of decision-guiding norms. With respect to the relevant first-order norms, Trina is in a state of substantial uncertainty. Given her disagreement with her friend Lesley, she doesn’t know whether submitting the receipt would be a morally objectionable form of fraud, which would directly give her a first-order reason to not submit the receipt. However, it still seems that Trina is in a position to know perfectly well what she should do. In light of this, it looks like there is a different set of norms – second-order norms – that guide decisions under moral uncertainty. And in the above case, it is easily conceivable that Trina knows about the second-order norms guiding her decision while not knowing about the relevant first-order norms.

More specifically, the second-order moral norm that Matheson identifies on the basis of the above case is the following (see Matheson

MORAL CAUTION (MC): Having considered the moral status of doing action A in context C, if (i) subject S (epistemically) should believe or suspend judgment that doing A in C is a serious moral wrong, while (ii) S knows that refraining from doing A in C is not morally wrong, then S (morally) should not do A in C.

One immediate objection at this point is that this norm doesn ‘t tell us how to deal with , but only how to avoid states of substantive moral uncertainty. To counter this objection, it will help to look at cases of complete moral uncertainty , i.e. cases where the moral status of every available option is unclear. Consider, then, the following case from MacAskill et al. ( 2020 , p.16):

Susan is a doctor, who faces two sick individuals, Anne and Charlotte. Anne is a human patient, whereas Charlotte is a chimpanzee. They both suffer from the same condition and are about to die. Susan has a vial of a drug that can help. If she administers all of the drug to Anne, Anne will survive but with disability, at half the level of welfare she’d have if healthy.

Now consider the following: if Susan decides instead to give all of the drug to Charlotte, then Charlotte will survive with a slight disability at three quarters of the welfare that she’d have if she were healthy. Alternatively, if Susan splits the drug between the two, then they will both survive at a little less than 50% of the welfare that they’d have if they were healthy. Given this specification, we can now consider the rest of the case (MacAskill et al. 2020 , p. 17):

Susan is certain that the way to aggregate welfare is simply to sum it up, but is unsure about the value of the welfare of non-human animals. She thinks it is equally likely that chimpanzees’ welfare has no moral value and that chimpanzees’ welfare has the same moral value as human welfare. As she must act now, there is no way that she can improve her epistemic state with respect to the relative value of humans and chimpanzees. Her three options, then, are as follows: A: Give all of the drug to Anne. B: Split the drug. C: Give all of the drug to Charlotte.

Susan’s decision situation can be represented in the following table:

The crucial difference between this case and Trina’s is that in the above case, every option that is relevant to the decision situation is subject to substantive moral uncertainty. More specifically, given that Susan is unsure about the moral value of the welfare of non-human animals, she is not in a position to determine the relative choiceworthiness of any of the available options. To see this, suppose that chimpanzees’ welfare has no moral value at all. Against the background of this assumption, A is the best option and C is the worst option. However, if we suppose that chimpanzees’ welfare has the same moral value as human welfare, B will be the best option and A will be the worst option. So given that Susan is unsure about the moral value of chimpanzees’ welfare, she is in a state of substantive moral uncertainty with respect to each of the options available to her.

Let’s call cases like the above cases of complete moral uncertainty. The important point in our present context is that even in cases of complete moral uncertainty, there seem to be specific second-order norms that guide our decisions. For example, in the above case, it seems intuitive that it would be morally reckless for Susan not to choose option B. For given her uncertainty about the moral status of non-human animals, she would risk severe wrongdoing by choosing either option A or option C. However, Susan doesn’t know whether B really is the best option – if it turned out that chimpanzees’ welfare didn’t have any moral value, then A would be the best option. So if we suppose that Susan knows that she should choose option B, then her knowledge wouldn’t consist in first-order knowledge about what the morally best option is, but rather in second-order knowledge about what she should do given that she doesn’t know what the morally best option is – i.e. knowledge about second-order norms that guide our decisions under moral uncertainty.

While these first-order and second-order norms are epistemically independent in the way just described, they are still both moral norms. One just has to consider the kind of blame that the protagonists in our cases would deserve if they violated the second-order norms guiding their decisions: in such a case, we would say that they have made a moral mistake and that they accordingly deserve moral blame. Furthermore, while the specific hypothetical scenarios underlying the above cases are comparatively artificial, they also seem to have obvious implications for more realistic situations. For example, take Susan ‘s uncertainty with respect to chimpanzee welfare: just as Susan, many people are uncertain about the moral status that they should assign to non-human animals. And just as in Susan ‘s case, this uncertainty will have direct implications for their moral decisions. To see this, we can just apply the Moral Caution Principle to the situation that many people find themselves in with respect to the question of whether they should continue to consume animal products or adopt a vegan lifestyle. Given the increasing public awareness of the horrific conditions under which many animal products are produced, many of these people will be unsure whether continued consumption of these products would be morally permissible or not. At the same time, many people will plausibly assume that a vegan lifestyle is at least morally permissible. If we apply the Moral Caution Principle to this situation, it seems that it would directly require veganism. What these considerations show is that second-order moral norms, while usually being developed and discussed against the background of highly artificial and idealized counterfactual scenarios, are directly applicable to real-life contexts. In fact, Matheson himself has applied his principle to the question of whether eating meat is morally permissible and a number of further concrete moral problems like abortion and charitable giving (Matheson ).

So as far as the above considerations are convincing, there are substantive moral norms guiding our decisions that are epistemically accessible to us even in cases of moral uncertainty. This result should clearly have significant implications for the prospects of knowledge transmission accounts to adequately deal with the challenge of moral disagreement. The obvious idea at this point is that even in cases where the experts are uncertain about what is morally right, they can still tell us what we should do given that they are uncertain about what is morally right. Or to put it a little more formally: even in cases where the relevant first-order moral norms are subject to substantive expert disagreement, experts can still agree about the corresponding second-order norms that would therefore constitute the proper input of educational transfer processes. Given that these second-order norms, albeit their apparent abstractness, are directly applicable to many real-life situations, this result should be highly relevant to educational practice.

In light of this, there is a direct possibility of transmitting substantive moral insights even with respect to questions that are controversial among professional ethicists. This possibility consists in the transmission of knowledge about second-order moral norms that guide our decisions under moral uncertainty. One obvious objection at this point is that while the above strategy may indeed point to a specific theoretical possibility of transferring moral knowledge in the face of moral expert disagreement, it is still doomed to fail, because the second-order norms that it relies upon will again be subject to persistent expert disagreement. But to my mind, such skepticism is at least premature. First of all, it would have to be substantiated by concrete empirical evidence – and given how new the philosophical debate about moral uncertainty is, such evidence won’t be readily available. However, simply resorting to pessimistic platitudes about the inevitable controversiality of all philosophical questions won’t be enough, since as we have seen, there seems to be a surprising number of philosophical questions with respect to which the relevant experts agree. Given this, a more realistic prediction would be that at least some second-order moral norms will be controversial. If we assume that, then the proposed strategy will be inapplicable in some cases of first-order expert disagreement – namely in those cases in which no fitting second-order principle is available or in which the relevant second-order principles are subject to persistent expert disagreement. Nevertheless, it will still be applicable in some – and perhaps many – cases of first-order expert disagreement, and thereby effectively help to further mitigate the challenge of disagreement for moral knowledge transmission.

4 The Accuracy of the Challenge of Disagreement

In the last section, I have argued that the challenge of disagreement is not an effective challenge against knowledge transmission accounts of moral education: although it effectively undermines the possibility of knowledge transmission with respect to first-order moral propositions that are in fact controversial among moral experts, the transmission of knowledge about sufficiently uncontroversial first-order norms and about second-order norms that guide our decisions under moral uncertainty remains untouched. In this section, I would like to discuss the accuracy of the challenge of disagreement: are we really dealing with a specific challenge to knowledge transmission accounts of moral education, or does the underlying problem run deeper? In this context, I would like to focus on so-called skill- and virtue-based accounts, which have been particularly influential in the literature. One core idea behind these accounts is that if – given how controversial moral issues are within academic philosophy – students can’t just rely on moral experts in gaining moral insights, then they will have to develop these insights on their own. And to do this, they have to be provided with specific skills like critical reasoning skills (Musschenga ) and debating skills (Meyer 2011 ), but also emotional skills (Slote 2009 ) and general intellectual virtues like open-mindedness or tolerance (Haydon 2003 ). Michael Hand summarizes this idea as follows (Hand 2018 , p. 11):

A […] standard response to the problem of […] disagreement is the suggestion that we educate children about morality rather than in it. On this view we should make children aware of a broad range of moral codes and justificatory arguments, encourage them to subject those codes and arguments to critical scrutiny, and invite them to subscribe to whichever code they take to enjoy the strongest argumentative support. […] Our job as educators is to cultivate moral autonomy by enabling children to make their own independent judgements on the content and justification of morality.

In this passage, Hand rightly calls these competing accounts explicitly a ‚response’ to the challenge of disagreement. To appreciate the dialectical significance of this point, it is helpful to elaborate on it in a little more detail. If alternative accounts of moral education are to be read as a response to a specific objection against knowledge transmission accounts, this will already constitute a significant concession. More specifically, if proponents of skill- and virtue-based accounts have developed their theories as a reaction to specific problems of knowledge transmission accounts, this will indicate that they would in principle be willing to accept knowledge transmission accounts – given that those problems can be solved satisfactorily. And in fact, while many proponents of skill- and virtue-based accounts of moral education will plausibly also promote the development of intellectual skills and virtues as a value in itself, at least one important idea behind these accounts seems to be the following: just as educational measures in other domains, moral education would ideally – among other things – also aim at the transmission of substantive domain-specific knowledge. However, this is not how things are. In face of some regrettable epistemic peculiarities of the moral domain, we are in no position to simply pass moral knowledge on to future generations. Given this, we have no other choice than to enable students to make their own, independent moral judgements.

In what follows, I would like to argue that this line of thought is ultimately unconvincing, because skill- and virtue-based accounts of moral education are also heavily affected by the epistemically destructive implications of moral disagreement—and that the challenge of disagreement is therefore not a specific challenge for knowledge transmission accounts. Actually, on closer inspection, it is not at all clear how the acquisition of intellectual skills and virtues could serve as an adequate response to the challenge of disagreement. For instance, one just has to envision the situation that students will find themselves in after they have used all these skills and virtues to develop their own moral views. In fact, many of the beliefs that students will form will be controversial, both among professional philosophers and among their classmates. Whenever students take a stance on a controversial moral issue, they will inevitably find themselves disagreeing not only with their superiors, but also with their peers. And given that the epistemically destructive effects of these disagreements are equal to or greater than those of moral disagreements among professional philosophers, this will undermine the epistemic status of their beliefs. Footnote 15

At this point, it becomes clear why proponents of moral knowledge transmission and proponents of skill and virtue development are really in the same boat. One main motivation behind promoting the development of intellectual skills and virtues was that it allows students to arrive at well-formed moral beliefs that serve as a suitable basis for decisions and actions, even in cases where the relevant moral questions are controversial among experts. However, this is not the case. When it comes to moral questions that are controversial among experts, it is simply not possible for students to arrive at justified verdicts on their own, because the disagreeing experts undermine the justificatory status of any belief that the students could possibly form.

Given this, it seems that the challenge of disagreement is not a specific challenge to moral transmission accounts, but rather a general challenge to all accounts of moral education that aim at the development of moral insights. What’s more, it seems that knowledge transmission accounts are even less affected by the challenge of disagreement than their direct competitors. For instance, take cases where moral experts do in fact agree : in such cases, students who are encouraged to make up their own minds will likely still find themselves disagreeing with each other, which will again undermine their freshly formed beliefs’ justificatory status. In light of this, it looks like skill- or virtue-oriented accounts of moral education are actually more severely affected by the epistemically destructive implications of moral disagreement than knowledge transmission accounts.

That being said, it is important to stress that the above considerations are in no way meant as a general rejection of the idea that moral education should also aim at the development of various skills and virtues. Enabling students to make their own independent judgements is rightly widely regarded as a central educational goal, and should certainly be an integral part of their philosophical and moral education. However, this idea is in no way incompatible with knowledge transmission accounts of moral education. Passing moral insights on to future generations doesn’t mean to simply tell students what’s right and what’s wrong. Any pedagogically respectable realization of knowledge transfers will encourage and assist students to autonomously engage with the arguments and considerations that actually support the views that are presented to them. In fact, one might even argue that the transmission of moral knowledge already implies teaching the processes through which experts arrive at their conclusions. Understood in this way, enabling students to identify, evaluate and formulate ethical arguments and to critically assess the plausibility of different ethical theories is not just compatible with, but an integral part of moral knowledge transmission.