Competency Domains for Clinical Research Professionals

The core competency framework for clinical research professionals is designed to standardize competency expectations for the clinical research workforce by defining the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for conducting safe, ethical, and high-quality clinical trials., developed by the joint task force for clinical trial competency — an international team of investigators, educators, and other stakeholders, including acrp — the framework focuses on eight core competency domains, including scientific concepts and research design, ethical and patient safety considerations, investigational products development and regulation, clinical study operations (good clinical practice), study and site management, data management and informatics, leadership and professionalism, and communications and teamwork., explore each domain below (click to expand images), along with several acrp-developed resources to help guide workforce development..

Scientific Concepts and Research Design

Encompasses knowledge of scientific concepts related to the design and analysis of clinical trials., demonstrate knowledge of pathophysiology, pharmacology, and toxicology as related to medicines discovery and development, identify clinically important questions that are potentially testable clinical research hypotheses, through review of the professional literature, explain the elements (statistical, epidemiological, and operational) of clinical and translational study design, design a clinical trial, critically analyze study results with an understanding of therapeutic and comparative effectiveness.

Ethical and Participant Safety Considerations

Encompasses care of patients, aspects of human subject protection, and safety in the conduct of a clinical trial., compare and contrast clinical care and clinical management of research participants, define the concepts of “clinical equipoise” and “therapeutic misconception” as related to the conduct of a clinical trial, compare the requirements for human subject protections and privacy under different national and international regulations and ensure their implementation throughout all phases of a clinical study, explain the evolution of the requirement for informed consent from research participants and the principles and content of the key documents ensuring the protection of human participants in clinical research, describe the ethical issues involved when dealing with vulnerable populations and the need for additional safeguards, evaluate and apply an understanding of the past and current ethical issues, cultural variations, and commercial aspects to the medicines development process, explain how inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in a clinical protocol to assure human subject protection, summarize the principles and methods of distributing and balancing risk and benefit through selection and management of clinical trial subjects.

Investigational Products Development and Regulation

Encompasses knowledge of how drugs, devices, and biologicals are developed and regulated., discuss the historical events that precipitated the development of governmental regulatory processes for drugs, devices, and biologics, describe the roles and responsibilities of the various institutions participating in the medicines development process, explain the medicines development process and the activities that integrate commercial realities into the life cycle management of medical products, summarize the legislative and regulatory framework that supports the development and registration of medicines, devices, and biologics and ensures their safety, efficacy, and quality, describe the specific processes and phases that must be followed in order for the regulatory authority to approve the marketing authorization for a medical product, describe the safety reporting requirements of regulatory agencies both pre- and post-approval, appraise the issues generated and the effects of global expansion on the approval and regulation of medical products.

Clinical Trial Operations (GCPs)

Encompasses study management and gcp compliance; safety management (adverse event identification and reporting, postmarket surveillance, and pharmacovigilance), and handling of investigational product., evaluate the conduct and management of clinical trials within the context of a clinical development plan, describe the roles and responsibilities of the clinical investigation team as defined by gcp guidelines, evaluate the design conduct and documentation of clinical trials as required for compliance with gcp guidelines, compare and contrast the regulations and guidelines of global regulatory bodies relating to the conduct of clinical trials, describe appropriate control, storage, and dispensing of investigational products, differentiate the types of adverse events (aes) that occur during clinical trials, understand the identification process for aes, and describe the reporting requirements to institutional review boards/independent ethics committees (irbs/iecs), sponsors, and regulatory authorities, describe how global regulations and guidelines assure human subject protection and privacy during the conduct of clinical trials, describe the reporting requirements of global regulatory bodies relating to clinical trial conduct, describe the role and process for monitoring of the study, describe the roles and purpose of clinical trial audits, describe the various methods by which safety issues are identified and managed during the development and postmarketing phases of clinical research.

Study and Site Management

Encompasses content required at the site level to run a study (financial and personnel aspects). includes site and study operations (not encompassing regulatory/gcps)., describe the methods utilized to determine whether or not to sponsor, supervise, or participate in a clinical trial, develop and manage the financial, timeline, and cross-disciplinary personnel resources necessary to conduct a clinical or translational research study, apply management concepts and effective training methods to manage risk and improve quality in the conduct of a clinical research study, utilize elements of project management related to organization of the study site to manage patient recruitment, complete procedures, and track progress, identify the legal responsibilities, issues, liabilities, and accountabilities that are involved in the conduct of a clinical trial, identify and explain the specific procedural, documentation, and oversight requirements of pis, sponsors, contract research organizations (cros), and regulatory authorities related to the conduct of a clinical trial.

Data Management and Informatics

Encompasses how data are acquired and managed during a clinical trial, including source data, data entry, queries, quality control, and correction and the concept of a locked database., describe the role that biostatistics and informatics serve in biomedical and public health research, describe the typical flow of data throughout a clinical trial, summarize the process of electronic data capture and the importance of information technology in data collection, capture, and management, describe the ich gcp requirements for data correction and queries, describe the significance of data quality assurance systems and how standard operating procedures are used to guide these processes.

Leadership and Professionalism

Encompasses the principles and practice of leadership and professionalism in clinical research, describe the principles and practices of leadership, management, and mentorship, and apply them within the working environment, identify and implement procedures for the prevention or management of the ethical and professional conflicts that are associated with the conduct of clinical research, identify and apply the professional guidelines and codes of ethics that apply to the conduct of clinical research, describe the impact of regional diversity and demonstrate cultural competency in clinical study design and conduct.

Communication and Teamwork

Encompasses all elements of communication within the site and between the site and sponsor, cro, and regulators. understanding of teamwork skills necessary for conducting a clinical trial., discuss the relationship and appropriate communication between sponsor, cro, and clinical research site, describe the component parts of a traditional scientific publication, effectively communicate the content and relevance of clinical research findings to colleagues, advocacy groups, and the nonscientist community, describe methods necessary to work effectively with multidisciplinary teams, acrp core competency guidelines for clinical research coordinators™, these guidelines are intended to provide crcs with the support they need while improving operational quality and trial outcomes for all stakeholders in the clinical research enterprise., learn more >, acrp core competency framework for clinical trial monitoring™, prepare for the future of clinical trial monitoring by understanding the core competencies required of individuals involved in clinical study monitoring., acrp functional competency guidelines for pis and sub investigators™, these guidelines provide a comprehensive set of practical guidelines and actionable steps to help set and keep pis and sub-investigators on a path to success in clinical trials., acrp partners advancing the clinical research workforce™, acrp’s partners advancing the clinical research workforce™ is a multi-stakeholder collaborative of clinical research industry leaders who are committed to building a diverse, research-ready clinical research workforce..

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Brief research report article, a six-step model for developing competency frameworks in the healthcare professions.

- 1 Department of Paramedicine, Monash University, Frankston, VIC, Australia

- 2 McNally Project for Paramedicine Research, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3 Assessment and Evaluation, Faculty of Education, Queens University, Kingston, ON, Canada

- 4 The Wilson Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 5 Post Graduate Medical Education and Continuing Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Competency frameworks are developed for a variety of purposes, including describing professional practice and informing education and assessment frameworks. Despite the volume of competency frameworks developed in the healthcare professions, guidance remains unclear and is inconsistently adhered to (perhaps in part due to a lack of organizing frameworks), there is variability in methodological choices, inconsistently reported outputs, and a lack of evaluation of frameworks. As such, we proposed the need for improved guidance. In this paper, we outline a six-step model for developing competency frameworks that is designed to address some of these shortcomings. The six-steps comprise [1] identifying purpose, intended uses, scope, and stakeholders; [2] theoretically informed ways of identifying the contexts of complex, “real-world” professional practice, which includes [3] aligned methods and means by which practice can be explored; [4] the identification and specification of competencies required for professional practice, [5] how to report the process and outputs of identifying such competencies, and [6] built-in strategies to continuously evaluate, update and maintain competency framework development processes and outputs. The model synthesizes and organizes existing guidance and literature, and furthers this existing guidance by highlighting the need for a theoretically-informed approach to describing and exploring practice that is appropriate, as well as offering guidance for developers on reporting the development process and outputs, and planning for the ongoing maintenance of frameworks.

Introduction

Competency frameworks are developed for a variety of purposes, including describing professional practice and informing education and assessment frameworks. Despite the volume of frameworks developed in the healthcare professions, and the increasing move toward competency-based education, no clear guidance exists for those who develop them ( 1 , 2 ). As such, developers may be unclear about the purpose and scope of the framework, the selection of methods, and the use of such methods. This may be in part due to the lack of organizing or conceptual frameworks to guide decision making. As a result, there may be uncertainty in the appropriateness of the outputs from the development process—for example, evidence of a previous lack of focus on non-technical, structural, and teamwork competencies ( 3 – 7 ). These shortcomings were only reported in the years after the development and implementation of competency frameworks. To reduce some of this uncertainty, and to provide developers with a conceptual framework that is transferable across settings, we previously outlined a systems thinking approach by which to view and describe professional healthcare practice when developing competency frameworks ( 8 ). Systems thinking provides a lens that obligates a consideration of real-world contexts and complexities associated with professional practice, and the components and features required to competently enact such practice.

While a conceptual framework informed by systems thinking provides developers with an improved means by which to explore practice ( 8 ), it does little to aid developers with other, more practical elements of the development process. While guidance for developing competency frameworks exists, previous research exploring its use suggests further guidance is needed ( 1 ). Existing guidance is often vague [e.g., “use at least two methods that are complementary” ( 9 )], and can at times be contradictory, [e.g., some suggest specific methods, while others propose it should be guided by purpose ( 10 , 11 )]. Therefore, we offer that those developing competency frameworks in the healthcare professions would benefit from renewed guidance that clarifies ambiguities in the literature, and extends guidance to include a theoretically-informed means by which to explore professional healthcare practice, and contemporary approaches to evaluation of outcomes ( 1 , 8 , 12 – 14 ). In this paper, by synthesizing and consolidating existing guidance, and leveraging recent research exploring ways of improving framework development, we will outline a six-step model for developing competency frameworks in the health professions.

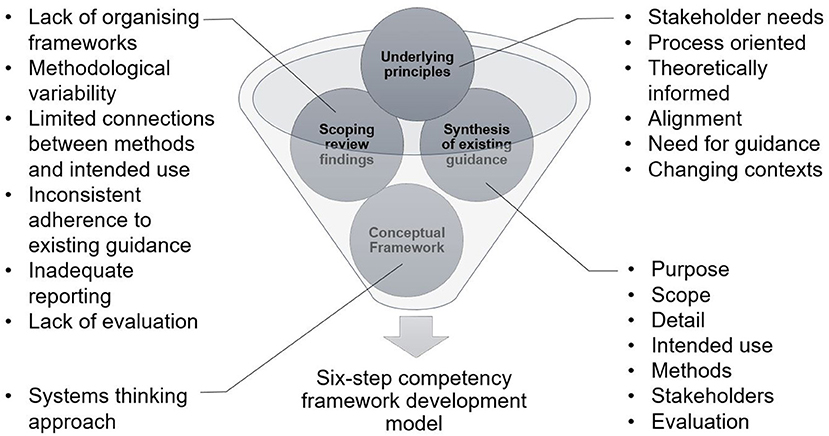

Using an iterative process informed by multiple sources of data we identified the necessary features of a model to provide renewed guidance for developing competency frameworks (see Figure 1 for sources). First, we utilized the findings of our scoping review of competency framework development in the healthcare professions ( 1 ). This detailed the shortcomings of the existing guidance, and highlighted several items that needed to be considered in the model. Second, we identified, organized, and synthesized the existing guidance on developing competency frameworks from multiple sources ( 9 – 11 , 15 – 27 ). These sources were informed by our scoping review ( 1 ), and contemporary methodological approaches ( 22 – 27 ). We approached this organization and synthesis as a form of qualitative data analysis ( 28 )—we iteratively analyzed the data, extracted the individual elements of guidance from each source, and then created categories of data from the elements (e.g., coding, and collapsing of codes). At this point, we integrated the findings from our scoping review in a similar manner. We observed a common structure in the existing guidance (e.g., plan study, gather data, translate data to competencies, report, and maintain), and elected to use this structure to inform the creation of the model. Third, we integrated a theoretically-informed approach to describing and exploring professional practice that utilized systems thinking ( 8 ). The use of a theoretical or conceptual approach to practice represents a novel contribution to the existing guidance. We incorporated this early in the model to help inform and guide subsequent choices made by developers. Finally, informed by these sources, we iteratively identified and extracted a set of underlying principles that seem to inform ways forward for renewed guidance (see Table 1 ).

Figure 1 . Inputs informing the structuring of guidance for the development of competency frameworks.

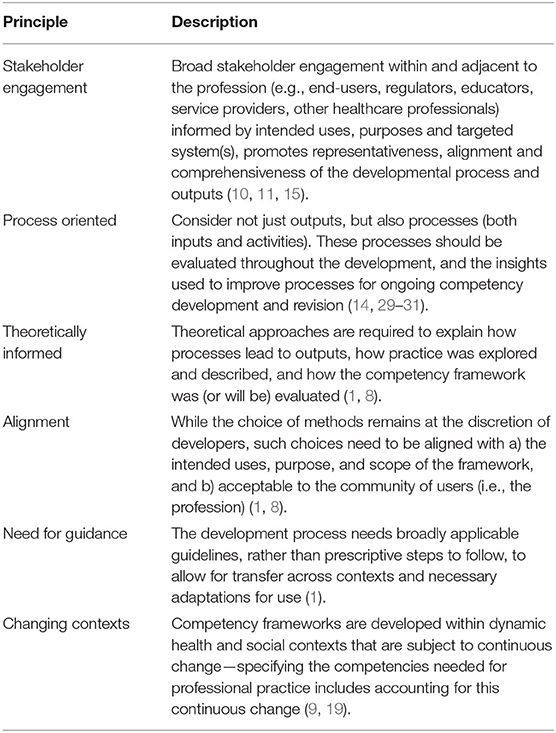

Table 1 . Underlying principles guiding competency framework development.

The findings of our scoping review highlighted a number of shortcomings with the existing approach to competency framework development ( 1 ). These included a focus on outputs over process, a lack of conceptual and/or theoretical frameworks, a lack of alignment between methodological choices and intended use of the framework, inconsistent adherence to existing guidance, significant variation in reporting, and a lack of planned evaluation and update of frameworks. The existing guidance on competency framework development outlined the need to identify the purpose and intended uses of the framework; the scope of contexts in which it was to be enacted; the methods used in the development process; and the stakeholders involved in the development ( 9 – 11 , 15 – 23 ). A systems thinking approach to identifying and exploring practice described the need to approach practice as a patient-centered activity which occurs in dynamic health and social contexts that need to be considered. In particular, practice is increasingly inter-professional, and competencies need to reflect this ( 4 , 32 ). Based on our understanding of the findings from these sources (scoping review, conceptual framework, and existing development literature), we identified a set of underlying principles to inform the development of our six-step model (see Table 1 ). First, there was a need for improved guidance that was not prescriptive. There needed to be alignment between methods and purpose of framework, and a renewed focus on the development process and not just the output. In line with existing guidance, broad stakeholder involvement would aid in improving the acceptability of the output to the profession ( 11 ). Finally, the model needed to acknowledge the dynamic and complex nature of practice.

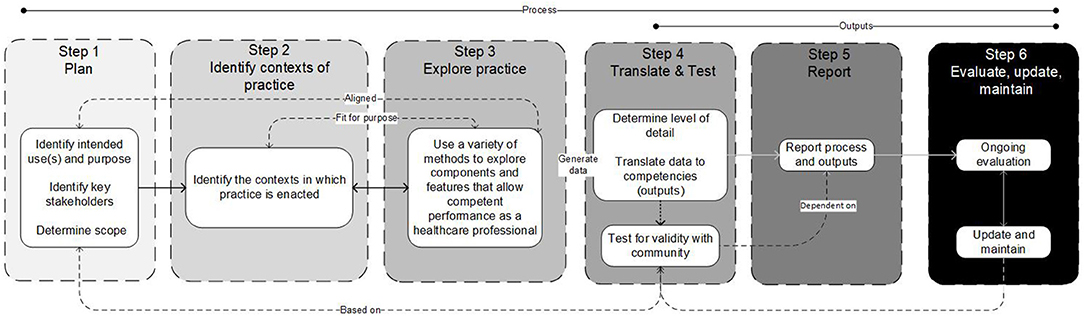

The inputs informing the structuring of our improved guidance ( Figure 1 ), suggest that any such guidance would need to account for [1] identifying intended uses, purpose, scope, detail, and stakeholders; [2] involve theoretically informed ways of identifying the people, elements, and contexts of complex, “real-world” professional practice, which includes [3] aligned methods and means by which such features and contexts can be explored. This would then provide a foundation on which to consider [4] the identification of and specification of competencies required for professional practice, [5] how to report the process and outputs of identifying such competencies, and [6] built-in strategies to continuously evaluate, update and maintain competency framework development processes and outputs (see Figure 2 ). Next, we will outline each step of the model. In particular, it is the inclusion of real-world contexts and complexities ( 8 ) in Step 2, and using “fit-for-purpose” aligned methods (Step 3), as well as the overall organizing framework—that we propose in this perspective— as necessary and unique augments when developing competency frameworks. We provide a practical overview of the six-step model for developers in Supplementary File 1 . We provide additional evidence to highlight the utility of this model including insights derived from examples of its use in practice in Supplementary File 2 .

Figure 2 . A schematic of the six-step model, illustrating the influences and connections between various steps, and indicating that the model is not necessarily intended to be implemented linearly in all cases.

The Six-Step Model

Step 1. plan.

In Step 1 we suggest that developers consider the purpose, intended uses and scope of the framework, and identify key stakeholders and their roles. Clearly outlining the purpose (e.g., identify competencies which enable inter-professional care), intended use (e.g., to make claims about the readiness of individuals to enact those competencies), and scope (e.g., health professions A, B and C of inter-professional teams working in all public hospital settings) serves to then inform and articulate specific claims of the framework, but also to support later steps of determining whether the final output sufficiently addresses those claims ( 9 , 33 , 34 ). Focusing on purposes and intended uses includes whether the framework is for binary (e.g., competent/not competent, accreditation granted/not granted) or other more continuous reasons (e.g., learning). Scope refers to contexts, boundaries, underlying principles, and articulated assumptions that ultimately inform an intended time, space, and place for the framework. This helps control for unintended uses or its transferability. For example, a competency framework intended to serve complex integrated health care models carries different implications (e.g., who to include as stakeholders) than for a highly specialized role (e.g., paramedics working independently in a specific region). Stakeholders at this step—those that can productively impact the developmental process or output—serve in general, two purposes. First, to contribute to defining purpose, scope and intended uses. Second, to provide a means for developers to eventually access the system, participate in developmental decisions and evaluations of processes and outputs (described in more detail below). Stakeholders can include for example, patients, families, healthcare professionals, educators, regulators, employers and partnering health professions, and are (at least initially), defined by developers and in consideration of purpose, intended use and scope ( 18 , 34 , 35 ). The stakeholder composition for these activities may be different but are expected to overlap in most cases. Consideration of that composition and their involvement at this early stage provide the foundation for subsequent steps.

These early decisions, including whether it is appropriate and feasible to have multiple purposes, collectively start to inform the degree of evidence needed, the kinds of methods that will or must follow, what developmental processes may be needed, what to do when unintended uses show up (when implemented) and who has or should have a say. Other considerations such as mandate of the developer, timeframes, availability of resources (e.g., financial and manpower), development experience and expertise, maturity and state of the targeted profession, access to and the complexity of practice, and consistent terminology are expected to be discussed and influence this early stage (and subsequent stages) of the development process ( 1 ).

Step 2. Identify Contexts of Practice

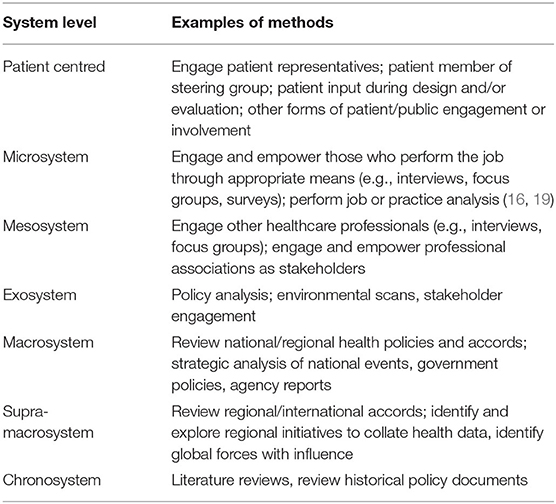

In Step 2, developers and stakeholders are actively involved in identifying and defining the contexts in which professional practice occurs. Here we define practice as something that exists and can be defined, which involves independent and then overlapping analyses with Step 3 ( 9 , 15 , 16 , 21 , 36 ). Developers might ask: “ What is healthcare profession X?” and “ What role does it serve the healthcare system and how is it unique?” and “ Who does profession X interact with to serve its function?” The intention here is to be as comprehensive as needed (given Step 1) toward understanding the professional role in context. The aim in this step is to sufficiently collect, discuss and generally be informed and influenced by the context(s) of practice. At least three different approaches can be considered. For example, developers may take iterative steps involving the analysis of existing position/profession descriptions, policy documents, or related government statements, conducting literature searches describing or informing the profession, evidence of role expansion or change, analysis of existing or planned activities, and analysis of gaps not sufficiently represented by existing competency frameworks ( 15 ). The second is to be guided by concepts derived from developmental evaluation ( 37 ). This makes evaluation an integral component of the design process, whereby inputs, processes and outputs are continuously evaluated and monitored in a rapidly changing environment. Finally, “systems thinking” has been presented as a meaningful way to structure the exploration of relevant contexts of practice ( 8 ), in order to capture the dynamic nature of contemporary healthcare systems ( 38 , 39 ). This conceptual framework outlines different ways of examining the components of the system at various levels (e.g., micro, meso, macro) as well as the relationships between them ( 40 ). While other ways of approaching the system exist and what people can or should be able to do in or for that system to be deemed competent, systems thinking provides a comprehensive and flexible starting point ( 40 – 44 ).

Examples of methods by which to identify and explore system levels are outlined in Table 2 .

Table 2 . Examples of methods by which to identify and explore system levels.

Step 3. Explore Practice

In Step 3, developers and stakeholders are involved in exploring practice to identify the components and features that allow competent performance as a healthcare professional. Here we define practice as something people do, which involves independent and then overlapping analyses with Step 2 and eventually description ( 9 , 15 , 16 , 21 , 36 ). Developers might ask “ What does an individual in the profession do?” and “ Does profession X perform differently depending on context?” and “ What is it that society and end-users expect a member of profession X to be able to do?” The intention here is to comprehensively understand how an individual in the profession enacts practice, within the context(s) identified in Step 2. Doing so will require developers to select appropriate methods to explore practice. The choice of methods by which to explore practice offers flexibility for developers (e.g., weighing practicality and cost-effectiveness, considering timeframes) ( 9 , 15 , 19 , 34 ) but also the opportunity to support or threaten alignment/coherence goals ( 45 ) (see Table 2 for examples of methods that developers may choose to enact to identify and explore practice).

Mixing of methods or the use of multiple methods may be necessary ( 22 , 23 ); however, the evidence to support the degree to which selected methods are “fit-for-purpose” should be considered with a rationale ( 46 ). Inherent in the consideration of multiple and/or mixed sources of information is the need to consider the alignment of various methods/methodologies to obtain information/data related to those sources. Selected methods should be applied defensibly, including but not limited to choice of sequence ( 46 ), and how data from multiple sources are integrated ( 46 , 47 ). Developers will need to determine the representativeness of samples (e.g., do you have data to represent the perspectives of diverse stakeholders and intended users?)—this may require equity-based considerations to ensure such perspectives are represented. The blending of diverse sources of information/data is expected to require a level of interpretation by developers, which means developers will need to consider what “stake” to give each source of data. This raises considerations such as whether data sources are considered equal, the sequence of data use, the priority of sources, the merging of data, the timing of integration, and the process of analysis ( 47 ).

Step 4. Translate and Test

In Step 4, developers and stakeholders will work collaboratively to identify competencies informed by the data collected in Steps 2 and 3. The actual process of translating data to outputs (i.e., competencies) will be informed and guided by methodological choices. As a general approach, we suggest there is value for developers in borrowing methods from qualitative data analysis. Developers begin by exploring the data, then coding the data iteratively and inductively ( 28 ) looking for repetitive and discrepant units of meaning, collapsing codes to reduce redundancy and overlap, and generating categories of data and descriptions and key themes (i.e., competencies) from the codes. There is a level of interpretation inherent in this process, and previous guidance suggests this step is “as much art as science” ( 34 ). Developers can improve the rigor of this translation process (from data to competencies) by focusing on improving credibility (e.g., by member checking) and dependability (e.g., by clearly outlining coding methods and ensuring a detailed audit trail throughout the translation process) ( 28 , 48 ).

Defensibility in this translation activity is promoted in at least three ways. These include a philosophical alignment between methods, underlying principles, contexts of practice and practice analysis; developing and implementing a plan of data collection and analysis that is methodologically defensible and fit-for-purpose; and an audit trail that can be examined by the intended community. An initial draft of the competency framework should be generated, informed by the data collected in Steps 2 and 3 ( 20 ), and developers can then engage with the broader profession, gathering feedback to further select and/or refine the framework. Healthcare professionals, subject matter experts, regulators, end-users, and those who the framework will affect as part of this translation process ( 10 , 20 , 35 ) should have the opportunity to reflect on the document, and provide feedback on whether it meets their needs, and reflects the values of the profession. Such a process is iterative and may require the use of consensus methods to finalize the output. This process is necessary to ensure the validity of the output (i.e., does the framework accurately represent the profession?) ( 35 ), and it should be noted that frameworks with “high-stakes” intended uses (e.g., regulation of practice) may require more extensive validation efforts in order to ensure that the output is accurate.

How a profession conceptualizes competence (e.g., degree of granularity from atomistic to holistic/integrated) will influence how developers decide to represent competence in a framework ( 29 ). Developers will need to consider the level of granularity desired in the framework ( 19 ), balancing enhanced precision (atomistic) against competency in dynamic contexts (holistic) ( 17 , 19 ). Atomistic frameworks risk introducing a reductionist, decontextualized approach to complex professional practice and the assumption that the linear accumulation of items assembles neatly again to inform competence. Holistic frameworks risk being too vague or generic, ultimately threatening utility ( 17 ). The identification of an appropriate organizing or conceptual framework will guide the structure of the output. For example, developers may elect to organize competencies by roles identified and defined within the profession (e.g., roles identified in Steps 2 and 3 or existing roles).

Notwithstanding the organizing structure of the output, competencies must be considered within the context of the profession, and linked back to the intended uses, purpose, and scope ( 19 ), once the professional role is broadly understood and defined (Steps 2 and 3) ( 15 ). The output should identify and integrate the knowledge, skills, attitudes and other important attributes associated with an identifiable aspect of professional performance. Competencies should be expressed in a manner that is easily understood, recognizable, and demonstrable in professional practice ( 15 ). Informed by intended use, purpose, scope and detail, in addition to considering “what is,” developers may also wish to consider “what will be needed in the future” and “what should be” when identifying competencies ( 18 , 19 ). Balancing immediate future needs (e.g., short-term developments in technology or society) with potential longer-term predictions (e.g., emerging technologies) may need to be considered.

Step 5. Report

In Step 5, developers report and communicate the output of the development process to the intended users and the broader profession. The six-step model outlined here, including the guiding principles, may be used to structure reporting of processes and outputs. This not only includes components of the output such as purpose, intended uses, scope etc., but also details of the processes that were undertaken—e.g., who was involved and for what purpose, how the contexts of practice were identified, how consensus was achieved, how and why methods were conducted, how data were collected and used, how the development process was evaluated throughout and how those results were used, and rationale for decisions (Step 3).

Previous efforts at reporting competency framework development largely focused on outputs, and much of the detail related to the development process remained implicit or was inconsistently reported ( 1 ). This focus on reporting of outputs means that we struggle to gain a meaningful understanding of processes and contexts, which hinders the ability to examine the validity and inherent limitations of frameworks. This can present obstacles when the community attempts to use or adopt frameworks and evaluate the short, medium, and long term outcomes of use. Finally, developers should report on the process used to translate or make sense of the data collected in Step 3 into competencies, and the results of any validation exercises (Step 4). Developers should use appropriate reporting guidelines if available and applicable.

Step 6. Evaluate, Update, and Maintain

Finally, in Step 6, developers plan for ongoing evaluation and updating of the competency framework ( 9 , 15 , 20 ) in order to ensure competencies reflect contemporary practice changes over time and to ensure their applicability and utility ( 19 , 21 ). Competency framework development and outputs may be treated as a type of “program,” and evaluated using existing program evaluation techniques ( 4 ). Identifying outcome measures is key to evaluation, but developers also need to consider unintended outcomes as a result of implementation. Such unintended outcomes will only become evident through a rigorous evaluation process that considers the factors surrounding (un)successful implementation of a program and not simply whether it worked or not. For example, using a logic or program approach would require developers to look at inputs, processes, outputs, and anticipated outcomes over the short, medium and long-term, and not just whether an output was produced ( 30 , 49 ). Contemporary program evaluation models emphasize the complex interactions between program factors (i.e., how and why did it work?) ( 12 , 14 , 50 , 51 ). The use of rapid-cycle program evaluation approaches, although resource intense, may also provide developers with real-time evidence to support changes to processes and competency frameworks ( 13 ). An approach that acknowledges context, complexity and processes should be applied to evaluate the development process, outputs, and achievement of intended outcomes over time ( 12 , 13 , 30 , 31 , 49 , 51 , 52 ). Such approaches may help us to understand the relationships between development processes, outputs (i.e., the competencies themselves), and implementation/use of the competence framework over time, which can inform ongoing revisions/improvements to future competency development processes and frameworks.

Competency framework development is a continuous process ( 9 , 15 ); thus, the reported framework or its validity is never “final.” Ongoing evaluation will help to identify what impact the framework is having, and in what areas it requires additional focus. As such, developers may wish to consider a “living document” approach whereby the framework becomes a dynamic publication that can be revisited and revised as time progresses, contexts change or practice expectations evolve. In any event, developers should form and articulate a plan to update, and maintain the competency framework over time ( 9 , 15 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 34 , 36 ). Previous guidance suggests that frameworks be updated every 5 years as a minimum, while acknowledging that frameworks may require more regular updates and maintenance if the profession in question is undergoing significant changes ( 19 , 53 ). Thus, we refrain from proposing any criteria concerning timeframes, and instead, recommend that developers consider factors that may reflect significant changes in practice or the contexts in which it is to be enacted (e.g., technology eliminating some jobs and introducing the need for new competencies).

We have outlined a six-step model for developing competency frameworks in the healthcare professions that synthesizes and organizes existing guidance and literature. The six-step model advances this existing guidance by incorporating the need for a theoretically-informed approach to identifying and exploring practice. The model offers clearer guidance for developers on reporting the development process and outputs, and planning for the ongoing maintenance of frameworks. The model, despite being described as a “six-step” model, is not intended to be implemented in a stepwise linear fashion, and in practice, the competency framework development process is non-linear—earlier steps may need to be revisited as later steps are considered ( 2 ). However, while the model allows for flexibility and there is an expectation for developers to move back and forth between steps, the sequence provided is logical, and therefore using the term steps appears appropriate.

One of the claims to which this model may be vulnerable is that there is no single “correct” approach to describing or representing professional practice. Developers may wish to consider other approaches to exploring practice that may provide alternative insights. The six-step model can be adapted to allow for this. Additionally, developers using this six-step model may require significant investment in resources and time. However, the model outlined here balances obligations with intended purpose, timeline, resource availability, expected outputs and the degree of defensibility/validity called for by the community. This suggests that if the framework will be used to make high-stakes decisions (e.g., entry to practice certification), then investing in appropriate resources may be necessary. A development process informed by developmental evaluation ( 37 ), organizing frameworks, and engages those who will use the framework, may assist with validation efforts and thresholds of acceptability among the community of users. Continuous evaluation and ongoing maintenance of the framework will contribute to its ongoing utility.

We suggest that the six-step model itself is transferable across contexts and professions. We also acknowledge there may be cases whereby an output (competency framework) developed using this six-step model could be transferable to other contexts (for example developed in one country, adopted in another). However, there are risks in doing so, the main risk being the validity of the framework for use in contexts from which it was not derived ( 8 ). As a result, the framework may be missing important contextual elements of practice, thereby leading to unintended outcomes. Developers will need to determine the level of contextual similarity before adopting or adapting a framework in a novel context.

Further research should continue to apply and examine this six-step model to clarify and refine the process, improve the identification of features and components, identify additional means of data collection, and analyse and explore the process for making meaning of the data to inform usable competency frameworks. In addition, developers may find benefit in reporting guidelines, which outline the essential items that should be included when reporting research studies. The use of reporting guidelines has increased the transparency of study methods and improved the translation of study findings in other fields ( 54 , 55 ).

The development of competency frameworks in healthcare professions to date demonstrates variable approaches, inconsistent reporting, and inadequate descriptions of practice. We offer a six-step model intended to guide future efforts at developing frameworks. Such efforts might be improved by applying the six-step model that considers intended uses, processes, outputs, and anticipates downstream uses of the framework. The model embraces theoretically informed approaches, acknowledges context, and consolidates existing guidance. The adoption of our model facilitates the sharing of common underlying principles and therefore shifts the focus from “what” or “how many” methods were used to whether such methods were aligned with the intended purpose and overall objectives, and meet an acceptability threshold set by the community. In addition, our model accepts that change occurs over time, and competencies require continuing evaluation, maintenance, and update. This six-step model ultimately offers developers a structure by which to identify the competencies required to enact competent healthcare professional practice.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

AB, BW, and WT devised the study. AB performed the literature review and drafted the initial manuscript. AB, BW, JR, and WT critically analyzed the literature. BW, JR and WT revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Open-access publication was funded by the Department of Paramedicine, Monash University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer SA declared a shared affiliation with several of the authors, AB and BW to the handling editor at the time of review.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Content within this manuscript previously appeared online via preprint, available from https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202103.0296/v2 ( 56 ).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.789828/full#supplementary-material

1. Batt AM, Tavares W, Williams B. The development of competency frameworks in healthcare professions: a scoping review. Adv Health Sci Educ. (2020) 25:913–87. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09946-w

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Tackett S, Sugarman J, Ng CJ, Kamarulzaman A, Ali J. Developing a competency framework for health research ethics education and training. J Med Ethics. (2021). doi: 10.1136/medethics-2021-107237

3. Castillo EG, Isom J, Debonis KL, Jordan A, Braslow JT, Rohrbaugh R. Reconsidering systems-based practice: advancing structural competency, health equity, and social responsibility in graduate medical education. Acad Med. (2020) 95:1817–22. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003559

4. Lingard L. Rethinking competence in the context of teamwork. In: Hodges BD, Lingard L, editors. Quest Competence . New York, NY, US: Cornell University Press (2012). p. 42–70.

Google Scholar

5. Salhi BA, Tsai JW, Druck J, Ward-Gaines J, White MH, Lopez BL. Toward structural competency in emergency medical education. AEM Educ Train. (2020) 4. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10416

6. Veen M, Skelton J, de la Croix A. Knowledge, skills and beetles: respecting the privacy of private experiences in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. (2020) 9:111–6. doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00565-5

7. Whitehead CR, Kuper A. Competency-based training for physicians: are we doing no harm? CMAJ. (2015) 187:E128–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140873

8. Batt AM, Williams B, Brydges M, Leyenaar M, Tavares W. New ways of seeing: supplementing existing competency framework development guidelines with systems thinking. Adv Health Sci Educ. (2021) 26:1355–137. doi: 10.1007/s10459-021-10054-x

9. Marrelli AF, Tondora J, Hoge MA. Strategies for developing competency models. Adm Policy Ment Health. (2005) 32:533–61. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-3264-0

10. Kwan J, Crampton R, Mogensen LL, Weaver R, Van Der Vleuten CPM, Hu WCY. Bridging the gap: a five stage approach for developing specialty-specific entrustable professional activities. BMC Med Educ. (2016) 16:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0637-x

11. Whiddett S, Hollyforde S. A Practical Guide to Competencies: How to Enhance Individual and Organisational Performance . London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2003).

12. Rich JV, Fostaty Young S, Donnelly C, Hall AK, Dagnone JD, Weersink K, et al. Competency-based education calls for programmatic assessment: but what does this look like in practice? J Eval Clin Pract . (2019) 26:1087–1095. doi: 10.1111/jep.13328

13. Hall AK, Rich J, Dagnone JD, Weersink K, Caudle J, Sherbino J, et al. It's a marathon, not a sprint: rapid evaluation of competency-based medical education program implementation. Acad Med. (2020) 95:786–93. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003040

14. Rojas D. Using Systems Engineering to Inform Program Evaluation Practices in Health Professions Education: Conceptualizing Educational Programs as Socio-Technical Systems to Study System Emergence. University of Toronto, Toronto (2018).

15. Heywood L, Gonczi A, Hager P. A Guide to Development of Competency Standards for Professions. Canberra . Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra (1992).

16. Roe R. What makes a competent psychologist? Eur Psychol. (2002) 7:192–202. doi: 10.1027//1016-9040.7.3.192

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Child SFJ, Shaw SD. A purpose-led approach towards the development of competency frameworks. J Furth High Educ. (2019) 00:1–14. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2019.1669773

18. Mansfield RS. Practical questions for building competency models. Communications. (2000) 1–34.

19. Campion MA, Fink AA, Ruggeberg BJ, Carr L, Phillips GM, Odman RB. Doing competencies well: best practices in competency modeling. Pers Psychol. (2011) 64:225–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01207.x

20. Lucia AD, Lepsinger R. The Art and Science of Competency Models : Pinpointing Critical Success Factors in Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer (1999).

21. Ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. (2005) 39:1176–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x

22. Ash S, Dowding K, Phillips S. Mixed methods research approach to the development and review of competency standards for dietitians. Nutr Diet. (2011) 68:305–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2011.01552.x

23. Palermo C, Conway J, Beck EJ, Dart J, Capra S, Ash S. Methodology for developing competency standards for dietitians in Australia. Nurs Health Sci. (2016) 18:130–7. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12247

24. Shorey S, Lau TC, Lau LST, Ang E. Entrustable professional activities in health care education: a scoping review. Med Educ. (2019) 53:766–777. doi: 10.1111/medu.13879

25. Wooltorton E, Seale E, Lewis D, Noel K, Liddy C, Viner G, et al. Rapid, collaborative generation and review of COVID-19 pandemic-specific competencies for family medicine residency training. Can Med Educ J. (2020) 11:50–5. doi: 10.36834/cmej.70254

26. Mucalo I, HadŽiabdić MO, Govorčinović T, Šarić M, Bruno A, Bates I. The development of the croatian competency framework for pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. (2016) 80. doi: 10.5688/ajpe808134

27. van der Aa JE, Aabakke AJM, Ristorp Andersen B, Settnes A, Hornnes P, Teunissen PW, et al. From prescription to guidance: a European framework for generic competencies. Adv Health Sci Educ. (2020) 25:173–87. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09910-8

28. Creswell J. Research Design : Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc (2014).

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

29. Rich JV. Do professions represent competence for entry-to-practice in similar ways? An exploration of competence frameworks through document analysis. Int J Scholarsh Teach Learn. (2019) 13. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130305

30. Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE Guide No. 67. Med Teach . (2012) 34. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668637

31. Rojas D, Grierson L, Mylopoulos M, Trbovich P, Bagli D, Brydges R. How can systems engineering inform the methods of programme evaluation in health professions education? Med Educ. (2018) 52:364–75. doi: 10.1111/medu.13460

32. Lingard L. What we see and don't see when we look at ‘competence': notes on a god term. Adv Health Sci Educ. (2009) 14:625–8. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9206-y

33. Shaw S, Crisp V. Reflections on a framework for validation – five years on. Res Matters Camb Assess Publ. (2015) 19:31–37.

34. Lucia AD, Lepsinger R. The Art and Science of Competency Models : Pinpointing Critical Success Factors in Organizations . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer (1999).

35. Whiddett S, Hollyforde S. A Practical Guide to Competencies: How to Enhance Individual and Organisational Performance . London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2003).

36. Klink M van der, Boon J. The investigation of competencies within professional domains. Hum Resour Dev Int. (2002) 5:411–24. doi: 10.1080/13678860110059384

37. Patton MQ. Developmental Evaluation: Applying Complexity Concepts to Enhance Innovation and Use . New York, NY: Guilford press (2010). p.399.

38. Hays RB, Ramani S, Hassell A. Healthcare systems and the sciences of health professional education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. (2020) 25:1149–62. doi: 10.1007/s10459-020-10010-1

39. Peters DH. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking? Health Res Policy Syst. (2014) 12:51. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-51

40. Armson R. Growing Wings on the Way Systems Thinking for Messy Situations . Axminster: Triarchy Press (2011).

41. Rosas SR. Systems thinking and complexity: considerations for health promoting schools. Health Promot Int. (2017) 32:301–311. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav109

42. Sweeney K, Griffiths F editors. Complexity and Healthcare: An Introduction . Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press (2002).

43. Midgley G. Systems Thinking. London: Sage London (2003). p. 492.

44. Savigny, Donald D, Taghreed, Adam. Alliance for health policy and systems research In: World Health Organization, editors. Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening . Geneva: WHO (2009).

45. Creswell JW, Klassen A, Plano Clark V, Smith K. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences (2014).

46. Curry LA, Krumholz HM, O'Cathain A, Clark VLP, Cherlin E, Bradley EH. Mixed methods in biomedical and health services research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2013) 6:119–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967885

47. O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ Online. (2010) 341:1147–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4587

48. Thomas E, Magilvy JK. Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. J Spec Pediatr Nurs JSPN. (2011) 16:151–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00283.x

49. Funnell S, Rogers P. Purposeful Program Theory: Effective Use of Theories of Change and Logic Models . San Fransisco, SF: Wiley (2011). p.576.

50. Hamza DM, Ross S, Oandasan I. Process and outcome evaluation of a CBME intervention guided by program theory. J Eval Clin Pract. (2020) 13344. doi: 10.1111/jep.13344

51. Van Melle E, Gruppen L, Holmboe ES, Flynn L, Oandasan I, Frank JR. Using contribution analysis to evaluate competency-based medical education programs. Acad Med. (2017) 92:752–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001479

52. Doll WE, Trueit D. Complexity and the health care professions. J Eval Clin Pract. (2010) 16:841–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01497.x

53. Werner E. “The answer key: CLEAR examination review,” in Clearinghouse for Licensure Enforcement and Regulation . Nicholasville (1990).

54. Moher D. Reporting guidelines: doing better for readers. BMC Med. (2018) 16:18–20. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1226-0

55. Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, Hoey J, Schulz KF, Altman DG. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR network. BMC Med. (2010) 8:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24

56. Batt AM, Williams B, Rich J, Tavares W. A six-step model for developing competency frameworks in the healthcare professions. Front Med Healthc Prof Educ. (2021). doi: 10.20944/preprints202103.0296.v2

Keywords: competency framework, competency profile, developing competencies, professional competency frameworks, professional practice

Citation: Batt A, Williams B, Rich J and Tavares W (2021) A Six-Step Model for Developing Competency Frameworks in the Healthcare Professions. Front. Med. 8:789828. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.789828

Received: 05 October 2021; Accepted: 23 November 2021; Published: 14 December 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Batt, Williams, Rich and Tavares. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alan Batt, alan.batt1@monash.edu

ResearchComp: The European Competence Framework for Researchers

Tool to assess and develop researchers' transferable skills and foster career development

What is ResearchComp?

ResearchComp is a tool that helps

- researchers assess and develop their own transversal skills

- higher education institutions and training providers adapt their offer to researchers

- employers to be aware of the wide set of competences of researchers

By supporting the development of researchers' transversal skills, it fosters inter-sectoral careers.

The tool was developed by the European Commission in close consultation with relevant stakeholders, delivering on the new European Research Area and the Skills Agenda , and contributing to the European Year of Skills .

ResearchComp is also the first competence framework aligned with the European Skills, Competences, and Occupations classification (ESCO) , as it has been developed on the basis of the taxonomy of transversal skills for researchers that was included in the 2022 version of the classification.

Researchers are a fundamental resource for research and innovation and for society at large. It is important that they are equipped with the transferrable skills necessary for effective and successful careers in all relevant sectors of the society, including academia, industry, the public administration and the non-profit sector.

Who can benefit from ResearchComp?

ResarchComp establishes a common language and a common understanding of researchers’ transversal competences, and it can be used, on a voluntary basis, by a variety of stakeholders.

- researchers can identify the competences that can foster interoperable careers in relevant socio-economic sectors, and will be able to assess which ones they already master and with what proficiency level, and which ones deserve additional efforts, with clear benefits for their career and employability

- universities, research organisations, and training providers can develop or adapt their training offer in order to equip researchers with the right transversal competences from the outset or through targeted training opportunities, with a lifelong learning perspective

- employers will be aware of the competences researchers can offer which will facilitate their search for highly-skilled talents

- policy makers can monitor researchers’ competences better, and can develop targeted policies in support of inter-sectorally mobile researchers

How is ResearchComp structured?

ResearchComp has 3 main dimensions

- 7 competence areas (cognitive abilities, doing research, managing research, managing research tools, making an impact, working with others, self-management)

- 38 competences

- 389 learning outcomes along 4 proficiency levels (foundational, intermediate, advanced, expert)

Each competence is defined by a descriptor, and is further developed with learning outcomes for each of the proficiency levels.

It is not suggested that researchers acquire the highest level of proficiency for all 38 competences or have the same proficiency across all the competences. However, researchers should develop competences in all 7 areas.

Progression across levels for the various competences can be the result of dedicated training courses, on-the-job-training, peer-to-peer learning, coaching and mentoring.

Frequently asked questions

Other eu competence frameworks.

- Competence Framework ‘Science for Policy’ for researchers

- Competence framework for 'innovative policymaking'

This policy brief, as part of the wider study “Knowledge ecosystems in the new ERA”, presents the European Competence Framework for Researchers ‘ResearchComp’, developed in line with the new ERA communication and the Skills Agenda.

This factsheet outlines the objectives and methodology for the development of a European Competence Framework for Researchers (ResearchComp).

Share this page

Competency Framework

What is it and who is it for.

The competency framework is for all research staff and includes anyone who contributes to the work undertaken by site based clinical research teams. Its purpose is to define the knowledge, skills and attributes of research staff.

How does it work?

The framework is made up of three sections; the Core Document which contains an introduction and outlines the competencies required; Evidence Forms which are used to document witness statements, testimonies and personal reflections and finally blank competency forms which can be used by mentors for Customisation of the framework to more specific needs if necessary.

How do I use it?

Where and how people work differs greatly and your setting can impact on how you use the framework. For example you may need to collaborate electronically on a document with people who don’t always work on the same site as you, or you may work somewhere with restricted access to computers, internet or Wi-Fi and find it easier to print a document out and work on it with a good old fashioned pen!

To help you with this, there are two ways of using the framework...

Offline Version

This is a pdf document which you can download and print.

Y ou can then work with your mentor face to face to fill out action plans and sign off your evidence.

This version is best if you have limited online access and you can meet with your mentor regularly.

Online Version

This is a Google D ocument t o copy and share with your mentor using G oogle D rive.

This means that you and your mentor can work remotely on the same, up-to-date document .

It can be really beneficial if you don't always work in the same physical place as your mentor.

B oth online and offline versions available to download and copy below.

Useful Links

Core Document

Core Document for the main core documents (both online and offline versions)

Evidence Forms

Click here for evidence forms to record reflection and witness statements

Customisation

Click here for blank competency templates

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- Expert advice

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Evidence and practice

A novel research competency framework for clinical research nurses and midwives, clair harris head of research workforce (nursing, ahps and practitioners), guy’s and st thomas’ hospitals nhs foundation trust, london, england, naomi hare research matron, guy’s and st thomas’ hospitals nhs foundation trust, london, england, laura mccabe research matron, guy’s and st thomas’ hospitals nhs foundation trust, london, england, hemawtee sreeneebus research matron, guy’s and st thomas’ hospitals nhs foundation trust, london, england, teresa crowley research practice educator, guy’s and st thomas’ hospitals nhs foundation trust, london, england.

• To explore the skill set and standards of competency in research delivery practice

• To understand the learning and development needs of nurses and midwives transitioning into research delivery roles

• To learn how one NHS trust developed and implemented a novel competency framework for research delivery

Background Clinical research nurses and midwives (CRN/Ms) are highly specialised registered nurses. They combine their clinical nursing expertise with research knowledge and skills to aid in the delivery of rigorous, high-quality clinical research to improve health outcomes, the research participant’s experience and treatment pathways ( Beer et al 2022 ). However, there is evidence that the transition into a CRN/M role is challenging for registered nurses.

Aim To discuss the development of a competency framework for CRN/Ms.

Discussion The authors identified a gap in their organisation for standards that would support the development of CRN/Ms new to the role. The standards needed to be clear and accessible to use while encompassing the breadth of scope of CRN/Ms’ practice. The authors used a systematic and inclusive process drawing on Benner’s (1984) theory of competence development to develop a suitable framework. Stakeholders engaged in its development included research participants, inclusion agents and CRN/Ms.

Conclusion The project identified 15 elements that are core to the CRN/M role and the knowledge, skills and behaviours associated with it.

Implications for practice A large NHS Trust has implemented the framework. It is also being shown to national and regional networks. Evaluation is under way.

Nurse Researcher . doi: 10.7748/nr.2023.e1900

This article has been subject to external double-blind peer review and checked for plagiarism using automated software

None declared

Harris C, Hare N, McCabe L et al (2023) A novel research competency framework for clinical research nurses and midwives. Nurse Researcher. doi: 10.7748/nr.2023.e1900

Published online: 28 December 2023

competence - competency framework - education - post-registration education - practice learning - professional development - professional issues - research

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

13 March 2024 / Vol 32 issue 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: A novel research competency framework for clinical research nurses and midwives

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Not a member?

Find out what The Global Health Network can do for you. Register now.

Member Sites Our network of members around the world. Join us now.

- 1000 Challenge

- ODIN Wastewater Surveillance Project

- Global Health Research Management

- UK Overseas Territories Public Health Network

- Global Malaria Research

- Coronavirus

- Sub-Saharan Congenital Anomalies Network

- Global Health Data Science

- AI for Global Health Research

- MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL

- Virtual Biorepository

- Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

- Rapid Support Team

- The Global Health Network Africa

- The Global Health Network Asia

- The Global Health Network LAC

- Global Health Bioethics

- Global Pandemic Planning

- EPIDEMIC ETHICS

- Global Vector Hub

- Global Health Economics

- LactaHub – Breastfeeding Knowledge

- Global Birth Defects

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

- Human Infection Studies

- EDCTP Knowledge Hub

- CHAIN Network

- Brain Infections Global

- Research Capacity Network

- Global Research Nurses

- ZIKAlliance

- TDR Fellows

- Global Health Coordinators

- Global Health Laboratories

- Global Health Methodology Research

- Global Health Social Science

- Global Health Trials

- Zika Infection

- Global Musculoskeletal

- Global Pharmacovigilance

- Global Pregnancy CoLab

- INTERGROWTH-21ˢᵗ

- East African Consortium for Clinical Research

- Women in Global Health Research

- Global Pathogen Variants

Research Tools Our resources designed to help you.

- Site Finder

- Process Map

- Global Health Training Centre

- Resources Gateway

- Global Health Research Process Map

What is it?

- Scoring & Moderation

- Translations

- For Individuals

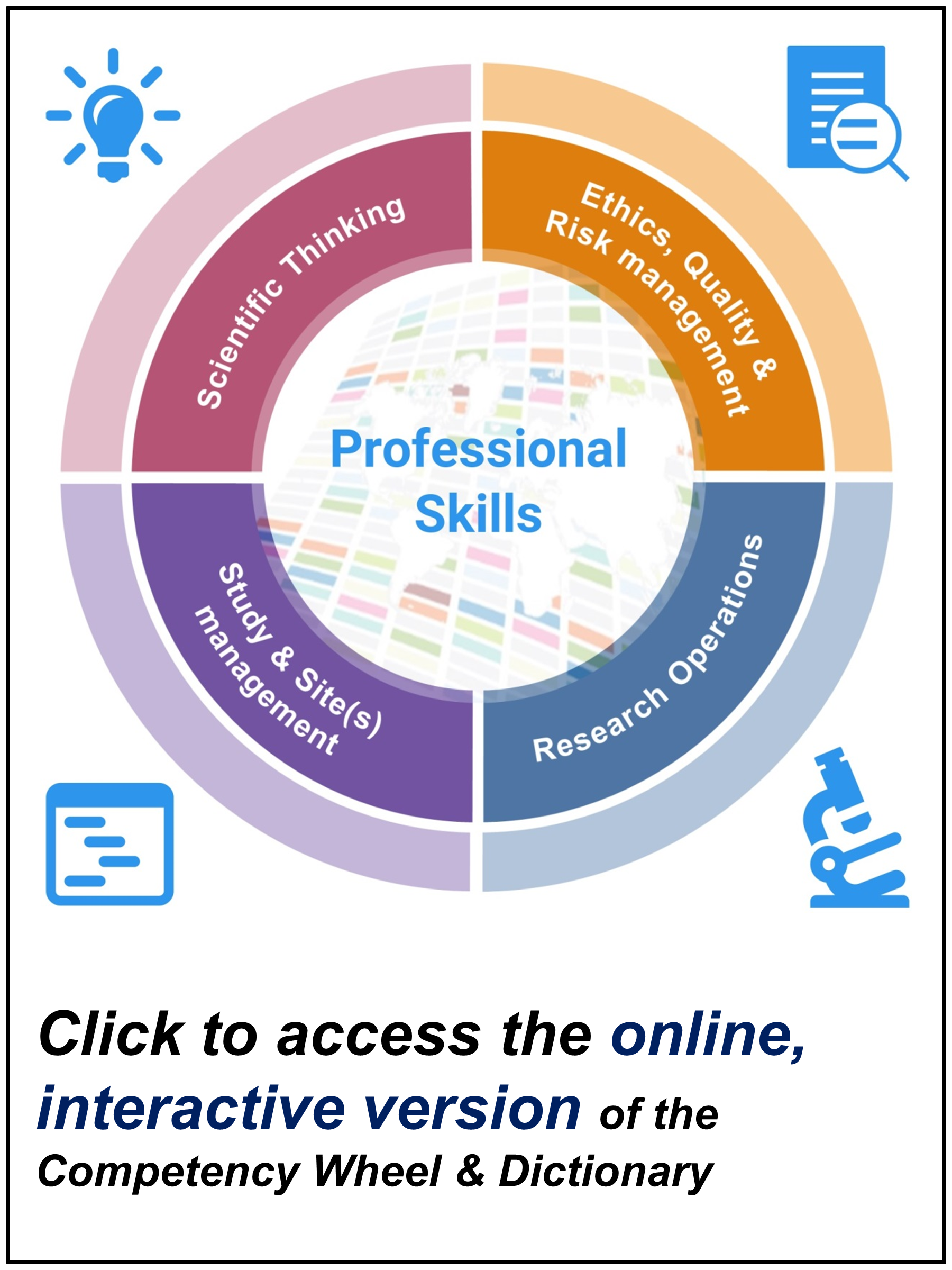

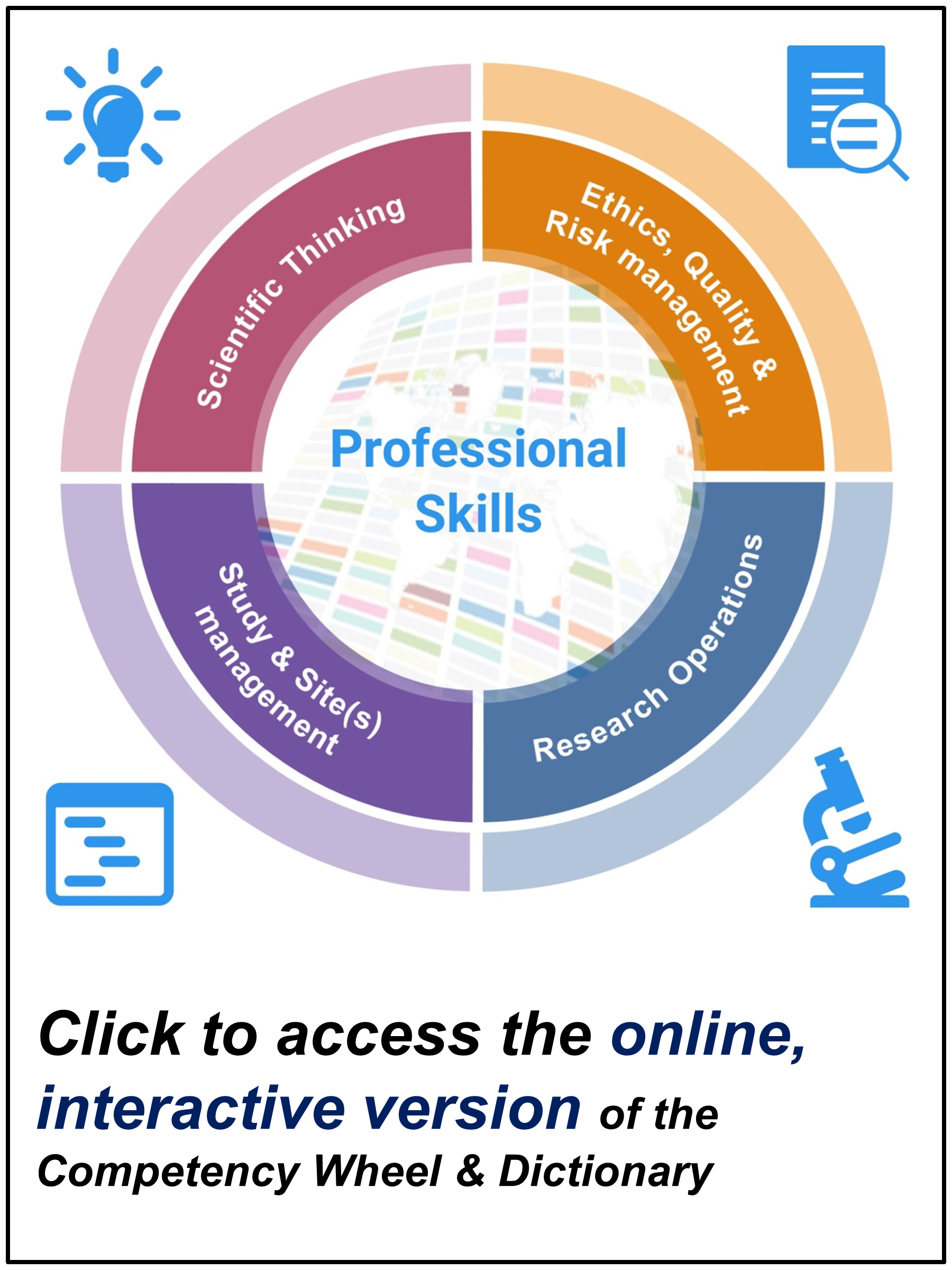

Research Competencies

The TDR Global Competency Framework for Clinical Research is a flexible framework which lists all the competencies that should be demonstrated by a research team to carry out a successful study. The framework can be applied to any research study, regardless of the size of the team, place, disease focus and type of research. Together with its supporting tools, the framework can be used to plan staffing requirements for a study, to carry out appraisals of staff, to guide career development, and to create educational curricula for research staff.

The Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) and researchers from The Global Health Network led the development of this framework, to bridge the lack of information about clinical research roles, especially for those working in low and middle income countries (LMICs). It has been developed alongside experts and collaborators from around the world.

What are the parts of the framework, and how does it work?

The framework consists of several complementary parts, including the Competency Wheel (overview) and Dictionary (explanation) which can be downloaded below.

What can I do?

You can use the framework in its current form for whatever you like: staff appraisals, assisting in your own career development, for planning the team you need for a new trial, for creating a new training programme - anything you like. You will find a full explanation of how to use the different parts of the framework in the User Guide available below.

Research Competency Scoring

Research Competency Framework

The Research Competency Framework has been designed to record your work to date and show that you are up to date with research training requirements. If you have an EDGE account, you can upload your completed Framework documents to your account so that you always have access. Otherwise, you could store them in the Google Drive cloud storage facility attached to your @nihr.ac.uk account.

You can access and download the Competency Framework document and Appendices below. The PDFs are editable so you can complete them digitally. Please download and reopen the document in order to do this. You can also complete the document by hand.

Competency Framework document

Appendix A: Essential Levels of Performance

Appendix B: Templates

Appendix C: Witness Statement

Appendix D: Reflective Accounts

- Schools & departments

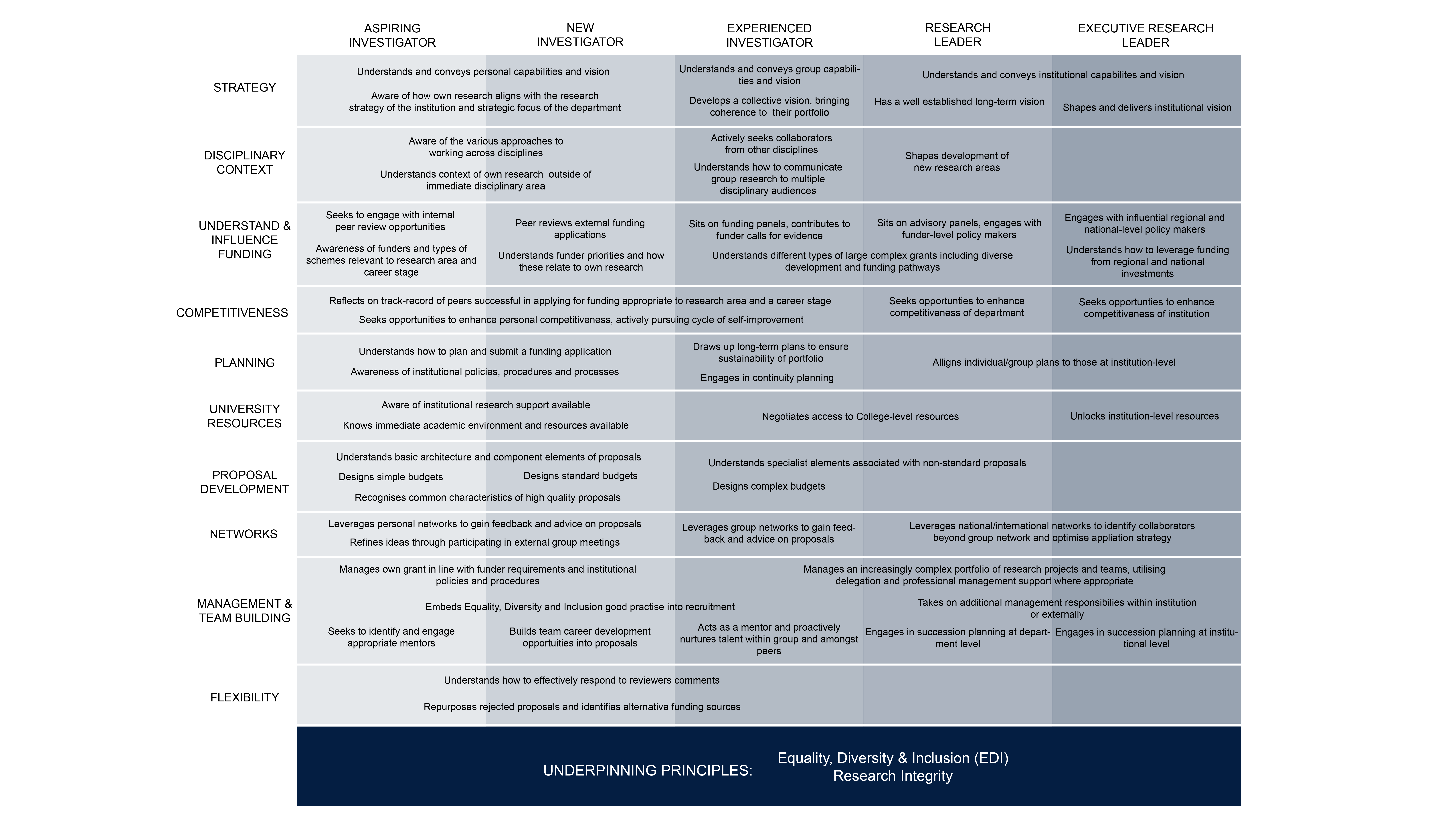

Competency framework for research funding

The competency framework for research funding sets out and defines the skills, knowledge and behaviours that researchers need to win research funding.

Researcher Development for Research Funding

Researcher Development for Research Funding is a learning and development hub, designed to give you the skills you need to write competitive, and ultimately successful, research funding applications. You will find learning resources related to the following research funding competencies:

- Strategy and Planning

- Understanding and Influencing Funding

- Proposal Writing

Visit the hub

The complete framework comprises ten competencies and spans the range of academic career levels. It is underpinned by two core principles:

- Equality, Diversity & Inclusion, and

- Research Integrity.

Who is it for?

The competency framework for research funding is designed for:

- Researchers – as a tool to help you evaluate and plan your route to research funding success

- Managers of researchers – as a resource to help you in your role supporting the career development of researchers

- Research management professionals – as a resource to help you in your planning and provision of research funding development opportunities

How to use the competency framework for research funding

Self-evaluation.

- Review the academic career-levels. Which one best fits your current funding track record?

- For each competency, read the associated skills, knowledge and behaviours and make an assessment of where you are.

- In which areas do you excel? Where do you need to develop your competence?

Planning your professional development

- Reflect on your research funding goals. Do you aspire to win your first grant, consolidate your funding portfolio, or win a large grant?

- Identify the competencies you need to develop in order to reach your funding goals.

- Use the framework to look for learning opportunities and to structure career development conversations with your line manager.

Download the framework

Read the below user guide to understand the competency framework.

This article was published on 2024-01-24

Not a member?

Find out what The Global Health Network can do for you. Register now.

Member Sites A network of members around the world. Join now.

- 1000 Challenge

- ODIN Wastewater Surveillance Project

- Global Health Research Management

- UK Overseas Territories Public Health Network

- Global Malaria Research

- Coronavirus

- Sub-Saharan Congenital Anomalies Network

- Global Health Data Science

- AI for Global Health Research

- MRC Clinical Trials Unit at UCL

- Virtual Biorepository

- Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

- Rapid Support Team

- The Global Health Network Africa

- The Global Health Network Asia

- The Global Health Network LAC

- Global Health Bioethics

- Global Pandemic Planning

- EPIDEMIC ETHICS

- Global Vector Hub

- Global Health Economics

- LactaHub – Breastfeeding Knowledge

- Global Birth Defects

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

- Human Infection Studies

- EDCTP Knowledge Hub

- CHAIN Network

- Brain Infections Global

- Research Capacity Network

- Global Research Nurses

- ZIKAlliance

- TDR Fellows

- Global Health Coordinators

- Global Health Laboratories

- Global Health Methodology Research

- Global Health Social Science

- Global Health Trials

- Zika Infection

- Global Musculoskeletal

- Global Pharmacovigilance

- Global Pregnancy CoLab

- INTERGROWTH-21ˢᵗ

- East African Consortium for Clinical Research

- Women in Global Health Research

- Global Pathogen Variants

Research Tools Resources designed to help you.

- Site Finder

- Process Map

- Global Health Training Centre

- Resources Gateway

- Global Health Research Process Map

Global Competency Framework for Research

New research competency web tool track your professional development using these competencies in the professional development scheme, and access an automated competency wheel of your experience. click here for more information.

What is it?

The TDR Global Competency Framework for Research is a flexible framework which lists all the competencies that should be demonstrated by a research team to carry out a successful study. The framework can be applied to any research study, regardless of the size of the team, place, disease focus and type of research. Together with its supporting tools, the framework can be used to plan staffing requirements for a study, to carry out appraisals of staff, to guide career development, and to create educational curricula for research staff.

The Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) and researchers from The Global Health Network led the development of this framework, to bridge the lack of information about research roles, especially for those working in low and middle income countries (LMICs). It has been developed alongside experts and collaborators from around the world.

You can learn more about how and why the framework was created by reading the article here .

What are the parts of the framework, and how does it work?

The framework consists of several complementary parts, including the Competency Wheel (overview), Dictionary (explanation), and Grading System (flexible tool for assessment of competency level). You can use the interactive online version or download individual parts by clicking on the icons below.

What can I do?

You can use the framework in its current form for whatever you like: staff appraisals, assisting in your own career development, for planning the team you need for a new study, for creating a new training programme - anything you like. You can find all the tools you need on this area of Global Health Trials, please just make sure to referen1ce us! You will find a full explanation of how to use the different parts of the framework in the User Guide available here , or by clicking on the Download the How-To User Guide button above).

Any feedback on the framework is welcome, good or bad! Please email [email protected] with your comments.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Med (Lausanne)

A Six-Step Model for Developing Competency Frameworks in the Healthcare Professions

1 Department of Paramedicine, Monash University, Frankston, VIC, Australia

2 McNally Project for Paramedicine Research, Toronto, ON, Canada

Brett Williams

Jessica rich.

3 Assessment and Evaluation, Faculty of Education, Queens University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Walter Tavares

4 The Wilson Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

5 Post Graduate Medical Education and Continuing Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Associated Data

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.