How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Inspiration

Three things to look forward to at Insight Out

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.

For instance, in writing about medical research, consider legal and ethical norms, including patient confidentiality laws and informed consent requirements. Similarly, if analyzing user data on social media platforms, be mindful of data privacy regulations, ensuring compliance with laws governing personal information collection and use. Aligning with legal and ethical standards not only avoids potential issues but also underscores the responsible conduct of your research.

3. Gather preliminary research

Once you’ve landed on your topic, it’s time to explore it further. You’ll want to discover more about available resources and existing research relevant to your assignment at this stage.

This exploratory phase is vital as you may discover issues with your original idea or realize you have insufficient resources to explore the topic effectively. This key bit of groundwork allows you to redirect your research topic in a different, more feasible, or more relevant direction if necessary.

Spending ample time at this stage ensures you gather everything you need, learn as much as you can about the topic, and discover gaps where the topic has yet to be sufficiently covered, offering an opportunity to research it further.

4. Define your research question

To produce a well-structured and focused paper, it is imperative to formulate a clear and precise research question that will guide your work. Your research question must be informed by the existing literature and tailored to the scope and objectives of your project. By refining your focus, you can produce a thoughtful and engaging paper that effectively communicates your ideas to your readers.

5. Write a thesis statement

A thesis statement is a one-to-two-sentence summary of your research paper's main argument or direction. It serves as an overall guide to summarize the overall intent of the research paper for you and anyone wanting to know more about the research.

A strong thesis statement is:

Concise and clear: Explain your case in simple sentences (avoid covering multiple ideas). It might help to think of this section as an elevator pitch.

Specific: Ensure that there is no ambiguity in your statement and that your summary covers the points argued in the paper.

Debatable: A thesis statement puts forward a specific argument––it is not merely a statement but a debatable point that can be analyzed and discussed.

Here are three thesis statement examples from different disciplines:

Psychology thesis example: "We're studying adults aged 25-40 to see if taking short breaks for mindfulness can help with stress. Our goal is to find practical ways to manage anxiety better."

Environmental science thesis example: "This research paper looks into how having more city parks might make the air cleaner and keep people healthier. I want to find out if more green spaces means breathing fewer carcinogens in big cities."

UX research thesis example: "This study focuses on improving mobile banking for older adults using ethnographic research, eye-tracking analysis, and interactive prototyping. We investigate the usefulness of eye-tracking analysis with older individuals, aiming to spark debate and offer fresh perspectives on UX design and digital inclusivity for the aging population."

6. Conduct in-depth research

A research paper doesn’t just include research that you’ve uncovered from other papers and studies but your fresh insights, too. You will seek to become an expert on your topic––understanding the nuances in the current leading theories. You will analyze existing research and add your thinking and discoveries. It's crucial to conduct well-designed research that is rigorous, robust, and based on reliable sources. Suppose a research paper lacks evidence or is biased. In that case, it won't benefit the academic community or the general public. Therefore, examining the topic thoroughly and furthering its understanding through high-quality research is essential. That usually means conducting new research. Depending on the area under investigation, you may conduct surveys, interviews, diary studies, or observational research to uncover new insights or bolster current claims.

7. Determine supporting evidence

Not every piece of research you’ve discovered will be relevant to your research paper. It’s important to categorize the most meaningful evidence to include alongside your discoveries. It's important to include evidence that doesn't support your claims to avoid exclusion bias and ensure a fair research paper.

8. Write a research paper outline

Before diving in and writing the whole paper, start with an outline. It will help you to see if more research is needed, and it will provide a framework by which to write a more compelling paper. Your supervisor may even request an outline to approve before beginning to write the first draft of the full paper. An outline will include your topic, thesis statement, key headings, short summaries of the research, and your arguments.

9. Write your first draft

Once you feel confident about your outline and sources, it’s time to write your first draft. While penning a long piece of content can be intimidating, if you’ve laid the groundwork, you will have a structure to help you move steadily through each section. To keep up motivation and inspiration, it’s often best to keep the pace quick. Stopping for long periods can interrupt your flow and make jumping back in harder than writing when things are fresh in your mind.

10. Cite your sources correctly

It's always a good practice to give credit where it's due, and the same goes for citing any works that have influenced your paper. Building your arguments on credible references adds value and authenticity to your research. In the formatting guidelines section, you’ll find an overview of different citation styles (MLA, CMOS, or APA), which will help you meet any publishing or academic requirements and strengthen your paper's credibility. It is essential to follow the guidelines provided by your school or the publication you are submitting to ensure the accuracy and relevance of your citations.

11. Ensure your work is original

It is crucial to ensure the originality of your paper, as plagiarism can lead to serious consequences. To avoid plagiarism, you should use proper paraphrasing and quoting techniques. Paraphrasing is rewriting a text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. Quoting involves directly citing the source. Giving credit to the original author or source is essential whenever you borrow their ideas or words. You can also use plagiarism detection tools such as Scribbr or Grammarly to check the originality of your paper. These tools compare your draft writing to a vast database of online sources. If you find any accidental plagiarism, you should correct it immediately by rephrasing or citing the source.

12. Revise, edit, and proofread

One of the essential qualities of excellent writers is their ability to understand the importance of editing and proofreading. Even though it's tempting to call it a day once you've finished your writing, editing your work can significantly improve its quality. It's natural to overlook the weaker areas when you've just finished writing a paper. Therefore, it's best to take a break of a day or two, or even up to a week, to refresh your mind. This way, you can return to your work with a new perspective. After some breathing room, you can spot any inconsistencies, spelling and grammar errors, typos, or missing citations and correct them.

- The best research paper format

The format of your research paper should align with the requirements set forth by your college, school, or target publication.

There is no one “best” format, per se. Depending on the stated requirements, you may need to include the following elements:

Title page: The title page of a research paper typically includes the title, author's name, and institutional affiliation and may include additional information such as a course name or instructor's name.

Table of contents: Include a table of contents to make it easy for readers to find specific sections of your paper.

Abstract: The abstract is a summary of the purpose of the paper.

Methods : In this section, describe the research methods used. This may include collecting data, conducting interviews, or doing field research.

Results: Summarize the conclusions you drew from your research in this section.

Discussion: In this section, discuss the implications of your research. Be sure to mention any significant limitations to your approach and suggest areas for further research.

Tables, charts, and illustrations: Use tables, charts, and illustrations to help convey your research findings and make them easier to understand.

Works cited or reference page: Include a works cited or reference page to give credit to the sources that you used to conduct your research.

Bibliography: Provide a list of all the sources you consulted while conducting your research.

Dedication and acknowledgments : Optionally, you may include a dedication and acknowledgments section to thank individuals who helped you with your research.

- General style and formatting guidelines

Formatting your research paper means you can submit it to your college, journal, or other publications in compliance with their criteria.

Research papers tend to follow the American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), or Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) guidelines.

Here’s how each style guide is typically used:

Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS):

CMOS is a versatile style guide used for various types of writing. It's known for its flexibility and use in the humanities. CMOS provides guidelines for citations, formatting, and overall writing style. It allows for both footnotes and in-text citations, giving writers options based on their preferences or publication requirements.

American Psychological Association (APA):

APA is common in the social sciences. It’s hailed for its clarity and emphasis on precision. It has specific rules for citing sources, creating references, and formatting papers. APA style uses in-text citations with an accompanying reference list. It's designed to convey information efficiently and is widely used in academic and scientific writing.

Modern Language Association (MLA):

MLA is widely used in the humanities, especially literature and language studies. It emphasizes the author-page format for in-text citations and provides guidelines for creating a "Works Cited" page. MLA is known for its focus on the author's name and the literary works cited. It’s frequently used in disciplines that prioritize literary analysis and critical thinking.

To confirm you're using the latest style guide, check the official website or publisher's site for updates, consult academic resources, and verify the guide's publication date. Online platforms and educational resources may also provide summaries and alerts about any revisions or additions to the style guide.

Citing sources

When working on your research paper, it's important to cite the sources you used properly. Your citation style will guide you through this process. Generally, there are three parts to citing sources in your research paper:

First, provide a brief citation in the body of your essay. This is also known as a parenthetical or in-text citation.

Second, include a full citation in the Reference list at the end of your paper. Different types of citations include in-text citations, footnotes, and reference lists.

In-text citations include the author's surname and the date of the citation.

Footnotes appear at the bottom of each page of your research paper. They may also be summarized within a reference list at the end of the paper.

A reference list includes all of the research used within the paper at the end of the document. It should include the author, date, paper title, and publisher listed in the order that aligns with your citation style.

10 research paper writing tips:

Following some best practices is essential to writing a research paper that contributes to your field of study and creates a positive impact.

These tactics will help you structure your argument effectively and ensure your work benefits others:

Clear and precise language: Ensure your language is unambiguous. Use academic language appropriately, but keep it simple. Also, provide clear takeaways for your audience.

Effective idea separation: Organize the vast amount of information and sources in your paper with paragraphs and titles. Create easily digestible sections for your readers to navigate through.

Compelling intro: Craft an engaging introduction that captures your reader's interest. Hook your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

Thorough revision and editing: Take the time to review and edit your paper comprehensively. Use tools like Grammarly to detect and correct small, overlooked errors.

Thesis precision: Develop a clear and concise thesis statement that guides your paper. Ensure that your thesis aligns with your research's overall purpose and contribution.

Logical flow of ideas: Maintain a logical progression throughout the paper. Use transitions effectively to connect different sections and maintain coherence.

Critical evaluation of sources: Evaluate and critically assess the relevance and reliability of your sources. Ensure that your research is based on credible and up-to-date information.

Thematic consistency: Maintain a consistent theme throughout the paper. Ensure that all sections contribute cohesively to the overall argument.

Relevant supporting evidence: Provide concise and relevant evidence to support your arguments. Avoid unnecessary details that may distract from the main points.

Embrace counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing views to strengthen your position. Show that you have considered alternative arguments in your field.

7 research tips

If you want your paper to not only be well-written but also contribute to the progress of human knowledge, consider these tips to take your paper to the next level:

Selecting the appropriate topic: The topic you select should align with your area of expertise, comply with the requirements of your project, and have sufficient resources for a comprehensive investigation.

Use academic databases: Academic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR offer a wealth of research papers that can help you discover everything you need to know about your chosen topic.

Critically evaluate sources: It is important not to accept research findings at face value. Instead, it is crucial to critically analyze the information to avoid jumping to conclusions or overlooking important details. A well-written research paper requires a critical analysis with thorough reasoning to support claims.

Diversify your sources: Expand your research horizons by exploring a variety of sources beyond the standard databases. Utilize books, conference proceedings, and interviews to gather diverse perspectives and enrich your understanding of the topic.

Take detailed notes: Detailed note-taking is crucial during research and can help you form the outline and body of your paper.

Stay up on trends: Keep abreast of the latest developments in your field by regularly checking for recent publications. Subscribe to newsletters, follow relevant journals, and attend conferences to stay informed about emerging trends and advancements.

Engage in peer review: Seek feedback from peers or mentors to ensure the rigor and validity of your research. Peer review helps identify potential weaknesses in your methodology and strengthens the overall credibility of your findings.

- The real-world impact of research papers

Writing a research paper is more than an academic or business exercise. The experience provides an opportunity to explore a subject in-depth, broaden one's understanding, and arrive at meaningful conclusions. With careful planning, dedication, and hard work, writing a research paper can be a fulfilling and enriching experience contributing to advancing knowledge.

How do I publish my research paper?

Many academics wish to publish their research papers. While challenging, your paper might get traction if it covers new and well-written information. To publish your research paper, find a target publication, thoroughly read their guidelines, format your paper accordingly, and send it to them per their instructions. You may need to include a cover letter, too. After submission, your paper may be peer-reviewed by experts to assess its legitimacy, quality, originality, and methodology. Following review, you will be informed by the publication whether they have accepted or rejected your paper.

What is a good opening sentence for a research paper?

Beginning your research paper with a compelling introduction can ensure readers are interested in going further. A relevant quote, a compelling statistic, or a bold argument can start the paper and hook your reader. Remember, though, that the most important aspect of a research paper is the quality of the information––not necessarily your ability to storytell, so ensure anything you write aligns with your goals.

Research paper vs. a research proposal—what’s the difference?

While some may confuse research papers and proposals, they are different documents.

A research proposal comes before a research paper. It is a detailed document that outlines an intended area of exploration. It includes the research topic, methodology, timeline, sources, and potential conclusions. Research proposals are often required when seeking approval to conduct research.

A research paper is a summary of research findings. A research paper follows a structured format to present those findings and construct an argument or conclusion.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics.

- 10 research paper

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Spring & Summer 2024 Admissions Open Now. Sign up for upcoming live information sessions here .

How to Write a Research Paper

Undergrads often write research papers each semester, causing stress. Yet, it’s simpler than believing if you know how to write a research paper . Divide the task, get tips, a plan, and tools for an outstanding paper. Simplify research, writing, topic choice, and illustration use!

A research paper is an academic document that involves deep, independent research to offer analysis, interpretation, and argument. Unlike academic essays, research papers are lengthier and more detailed, aiming to evaluate your writing and scholarly research abilities. To write one, you must showcase expertise in your subject, interact with diverse sources, and provide a unique perspective to the discussion.

Research papers are a foundational element of contemporary science and the most efficient means of disseminating knowledge throughout a broad network. Nonetheless, individuals usually encounter research papers during their education; they are frequently employed in college courses to assess a student’s grasp of a specific field or their aptitude for research.

Given their significance, research papers adopt a research paper format – a formal, unadorned style that eliminates any subjective influence from the writing. Scientists present their discoveries straightforwardly, accompanied by relevant supporting proof, enabling other researchers to integrate the paper into their investigations.

This guide leads you through every steps to write a research paper , from grasping your task to refining your ultimate draft and will teach you how to write a research paper.

Understanding The Research Paper

A research paper is a meticulously structured document that showcases the outcomes of an inquiry, exploration, or scrutiny undertaken on a specific subject. It embodies a formal piece of academic prose that adds novel information, perspectives, or interpretations to a particular domain of study. Typically authored by scholars, researchers, scientists, or students as part of their academic or professional pursuits, these papers adhere to a well-defined format. This research paper format encompasses an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

The introduction provides context and outlines the study’s significance, while the literature review encapsulates existing research and situates the study within the broader academic discourse. The methodology section elucidates the research process, encompassing data collection and analysis techniques. Findings are presented in the results section, often complemented by graphical and statistical representations. Interpretation of findings, implications, and connection to existing knowledge transpire in the discussion section.

Ultimately, the conclusion encapsulates pivotal discoveries and their wider import.

Research papers wield immense significance in advancing knowledge across diverse disciplines, enabling researchers to disseminate findings, theories, and revelations to a broader audience. Before publication in academic journals or presentations at conferences, these papers undergo a stringent peer review process conducted by domain experts, ensuring their integrity, precision, and worth.

Academic and non-academic research papers diverge across several dimensions. Academic papers are crafted for scholarly circles to expand domain knowledge and theories. They maintain a formal, objective tone and heavily rely on peer-reviewed sources for credibility. In contrast, non-academic papers, employing a more flexible writing style, target a broader audience or specific practical goals. These papers might incorporate persuasive language, anecdotes, and various sources beyond academia. While academic papers rigorously adhere to structured formats and established citation styles, non-academic papers prioritize practicality, adapting their structure and citation methods to suit the intended readership.

The purpose of a research paper revolves around offering fresh insights, knowledge, or interpretations within a specific field. This formal document serves as a conduit for scholars, researchers, scientists, and students to communicate their investigative findings and actively contribute to the ongoing academic discourse.

Research Paper Writing Process – How To Write a Good Research Paper

Selecting a suitable research topic .

Your initial task is to thoroughly review the assignment and carefully absorb the writing prompt’s details. Pay particular attention to technical specifications like length, formatting prerequisites (such as single- vs. double-spacing, indentation, etc.), and the required citation style. Also, pay attention to specifics, including an abstract or a cover page.

Once you’ve a clear understanding of the assignment, the subsequent steps to write a research paper are aligned with the conventional writing process. However, remember that research papers have rules, adding some extra considerations to the process.

When given some assignment freedom, the crucial task of choosing a topic rests on you. Despite its apparent simplicity, this choice sets the foundation for your entire research paper, shaping its direction. The primary factor in picking a research paper topic is ensuring it has enough material to support it. Your chosen topic should provide ample data and complexity for a thorough discussion. However, it’s important to avoid overly broad subjects and focus on specific ones that cover all relevant information without gaps. Yet, approach topic selection more slowly; choosing something that genuinely interests you is still valuable. Aim for a topic that meets both criteria—delivering substantial content while maintaining engagement.

Conducting Thorough Research

Commence by delving into your research early to refine your topic and shape your thesis statement. Swift engagement with available research aids in dispelling misconceptions and unveils optimal paths and strategies to gather more material. Typically, research sources can be located either online or within libraries. When navigating online sources, exercise caution and opt for reputable outlets such as scientific journals or academic papers. Specific search engines, outlined below in the Tools and Resources section, exclusively enable exploring accredited sources and academic databases.

While pursuing information, it’s essential to differentiate between primary and secondary sources. Primary sources entail firsthand accounts, encompassing published articles or autobiographies, while secondary sources, such as critical reviews or secondary biographies, are more distanced. Skimming sources instead of reading each part proves more efficient during the research phase. If a source shows promise, set it aside for more in-depth reading later. Doing so prevents you from investing excessive time in sources that won’t contribute substantively to your work. You should present a literature review detailing your references and submit them for validation in certain instances.

Organizing And Structuring The Research Paper

According to the research paper format , an outline for a research paper is a catalogue of essential topics, arguments, and evidence you intend to incorporate. These elements are divided into sections with headings, offering a preliminary overview of the paper’s structure before commencing the writing process. Formulating a structural outline can significantly enhance writing efficiency, warranting an investment of time to establish one.

Start by generating a list encompassing crucial categories and subtopics—a preliminary outline. Reflect on the amassed information while gathering supporting evidence, pondering the most effective means of segregation and categorization.

Once a discussion list is compiled, deliberate on the optimal information presentation sequence and identify related subtopics that should be placed adjacent. Consider if any subtopic loses coherence when presented out of order. Adopting a chronological arrangement can be suitable if the information follows a straightforward trajectory.

Given the potential complexity of research papers, consider breaking down the outline into paragraphs. This aids in maintaining organization when dealing with copious information and provides better control over the paper’s progression. Rectifying structural issues during the outline phase is preferable to addressing them after writing.

Remember to incorporate supporting evidence within the outline. Since there’s likely a substantial amount to include, outlining helps prevent overlooking crucial elements.

Writing The Introduction

According to the research paper format , the introduction of a research paper must address three fundamental inquiries: What, why, and how? Upon completing the introduction, the reader should clearly understand the paper’s subject matter, its relevance, and the approach you’ll use to construct your arguments.

What? Offer precise details regarding the paper’s topic, provide context, and elucidate essential terminology or concepts.

Why? This constitutes the most crucial yet challenging aspect of the introduction. Endeavour to furnish concise responses to the subsequent queries: What novel information or insights do you present? Which significant matters does your essay assist in defining or resolving?

How? To provide the reader with a preview of the paper’s forthcoming content, the introduction should incorporate a “guide” outlining the upcoming discussions. This entails briefly outlining the paper’s principal components in chronological sequence.

Developing The Main Body

One of the primary challenges that many writers grapple with is effectively organizing the wealth of information they wish to present in their papers. This is precisely why an outline can be an invaluable tool. However, it’s essential to recognize that while an outline provides a roadmap, the writing process allows flexibility in determining the order in which information and arguments are introduced.

Maintaining cohesiveness throughout the paper involves anchoring your writing to the thesis statement and topic sentences. Here’s how to ensure a well-structured paper:

- Alignment with Thesis Statement: Regularly assess whether your topic sentences correspond with the central thesis statement. This ensures that your arguments remain on track and directly contribute to the overarching message you intend to convey.

- Consistency and Logical Flow: Review your topic sentences concerning one another. Do they follow a logical order that guides the reader through a coherent narrative? Ensuring a seamless flow from one topic to another helps maintain engagement and comprehension.

- Supporting Sentence Alignment: Each sentence within a paragraph should align with the topic sentence of that paragraph. This alignment reinforces the central idea, preventing tangential or disjointed discussions.

Additionally, identify paragraphs that cover similar content. While some overlap might be inevitable, it’s essential to approach shared topics from different angles, offering fresh insights and perspectives. Creating these nuanced differences helps present a well-rounded exploration of the subject matter.

An often-overlooked aspect of effective organization is the art of crafting smooth transitions. Transitions between sentences, paragraphs, and larger sections are the glue that holds your paper together. They guide the reader through the progression of ideas, enhancing clarity and creating a seamless reading experience.

Ultimately, while the struggle to organize information is accurate, employing these strategies not only aids in addressing the challenge but also contributes to the overall quality and impact of your writing.

Crafting A Strong Conclusion

The purpose of the research paper’s conclusion is to guide your reader out of the realm of the paper’s argument, leaving them with a sense of closure.

Trace the paper’s trajectory, underscoring how all the elements converge to validate your thesis statement. Impart a sense of completion by ensuring the reader comprehends the resolution of the issues introduced in the paper’s introduction.

In addition, you can explore the broader implications of your argument, outline your paper’s contributions to future students studying the subject, and propose questions that your argument raises—ones that might not be addressed in the paper itself. However, it’s important to avoid:

- Introducing new arguments or crucial information that wasn’t covered earlier.

- Extending the conclusion unnecessarily.

- Employing common phrases that signal the decision (e.g., “In conclusion”).

By adhering to these guidelines, your conclusion can serve as a fitting and impactful conclusion to your research paper, leaving a lasting impression on your readers.

Refining The Research Paper

- Editing And Proofreading

Eliminate unnecessary verbiage and extraneous content. In tandem with the comprehensive structure of your paper, focus on individual words, ensuring your language is robust. Verify the utilization of active voice rather than passive voice, and confirm that your word selection is precise and tangible.

The passive voice, exemplified by phrases like “I opened the door,” tends to convey hesitation and verbosity. In contrast, the active voice, as in “I opened the door,” imparts strength and brevity.

Each word employed in your paper should serve a distinct purpose. Strive to eschew the inclusion of surplus words solely to occupy space or exhibit sophistication.

For instance, the statement “The author uses pathos to appeal to readers’ emotions” is superior to the alternative “The author utilizes pathos to appeal to the emotional core of those who read the passage.”

Engage in thorough proofreading to rectify spelling, grammatical, and formatting inconsistencies. Once you’ve refined the structure and content of your paper, address any typographical and grammatical inaccuracies. Taking a break from your paper before proofreading can offer a new perspective.

Enhance error detection by reading your essay aloud. This not only aids in identifying mistakes but also assists in evaluating the flow. If you encounter sections that seem awkward during this reading, consider making necessary adjustments to enhance the overall coherence.

- Formatting And Referencing

Citations are pivotal in distinguishing research papers from informal nonfiction pieces like personal essays. They serve the dual purpose of substantiating your data and establishing a connection between your research paper and the broader scientific community. Given their significance, citations are subject to precise formatting regulations; however, the challenge lies in the existence of multiple sets of rules.

It’s crucial to consult the assignment’s instructions to determine the required formatting style. Generally, academic research papers adhere to either of two formatting styles for source citations:

- MLA (Modern Language Association)

- APA (American Psychological Association)

Moreover, aside from MLA and APA styles, occasional demands might call for adherence to CMOS (The Chicago Manual of Style), AMA (American Medical Association), and IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) formats.

Initially, citations might appear intricate due to their numerous regulations and specific details. However, once you become adept at them, citing sources accurately becomes almost second nature. It’s important to note that each formatting style provides detailed guidelines for citing various sources, including photographs, websites, speeches, and YouTube videos.

Tips For Writing An Effective Research Paper

By following these research paper writing tips , you’ll be well-equipped to create a well-structured, well-researched, and impactful research paper:

- Select a Clear and Manageable Topic: Choose a topic that is specific and focused enough to be thoroughly explored within the scope of your paper.

- Conduct In-Depth Research: Gather information from reputable sources such as academic journals, books, and credible websites. Take thorough notes to keep track of your sources.

- Create a Strong Thesis Statement: Craft a clear and concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or purpose of your paper.

- Develop a Well-Structured Outline: Organize your ideas into a logical order by creating an outline that outlines the main sections and their supporting points.

- Compose a Captivating Introduction: Hook the reader with an engaging introduction that provides background information and introduces the thesis statement.

- Provide Clear and Relevant Evidence: Support your arguments with reliable and relevant evidence, such as statistics, examples, and expert opinions.

- Maintain Consistent Tone and Style: Keep a consistent tone and writing style throughout the paper, adhering to the formatting guidelines of your chosen citation style.

- Craft Coherent Paragraphs: Each paragraph should focus on a single idea or point, and transitions should smoothly guide the reader from one idea to the next.

- Use Active Voice: Write in the active voice to make your writing more direct and engaging.

- Revise and Edit Thoroughly: Proofread your paper for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and sentence structure. Revise for clarity and coherence.

- Seek Peer Feedback: Have a peer or instructor review your paper for feedback and suggestions.

- Cite Sources Properly: Accurately cite all sources using the required citation style (e.g., MLA, APA) to avoid plagiarism and give credit to original authors.

- Be Concise and Avoid Redundancy: Strive for clarity by eliminating unnecessary words and redundancies.

- Conclude Effectively: Summarize your main points and restate your thesis in the conclusion. Provide a sense of closure without introducing new ideas.

- Stay Organized: Keep track of your sources, notes, and drafts to ensure a structured and organized approach to the writing process.

- Proofread with Fresh Eyes: Take a break before final proofreading to review your paper with a fresh perspective, helping you catch any overlooked errors.

- Edit for Clarity: Ensure that your ideas are conveyed clearly and that your arguments are easy to follow.

- Ask for Feedback: Don’t hesitate to ask for feedback from peers, instructors, or writing centers to improve your paper further.

In conclusion, we’ve explored the essential steps to write a research paper . From selecting a focused topic to mastering the intricacies of citations, we’ve navigated through the key elements of this process.

It’s vital to recognize that adhering to the research paper writing tips is not merely a suggestion, but a roadmap to success. Each stage contributes to the overall quality and impact of your paper. By meticulously following these steps, you ensure a robust foundation for your research, bolster your arguments, and present your findings with clarity and conviction.

As you embark on your own research paper journey, I urge you to put into practice the techniques and insights shared in this guide. Don’t shy away from investing time in organization, thorough research, and precise writing. Embrace the challenge, for it’s through this process that your ideas take shape and your voice is heard within the academic discourse.

Remember, every exceptional research paper begins with a single step. And with each step you take, your ability to articulate complex ideas and contribute to your field of study grows. So, go ahead – apply these tips, refine your skills, and witness your research papers evolve into compelling narratives that inspire, inform, and captivate.

In the grand tapestry of academia, your research paper becomes a thread of insight, woven into the larger narrative of human knowledge. By embracing the writing process and nurturing your unique perspective, you become an integral part of this ever-expanding tapestry.

Happy writing, and may your research papers shine brightly, leaving a lasting mark on both your readers and the world of scholarship.

Related Posts

Steps To Write A Great Research Paper

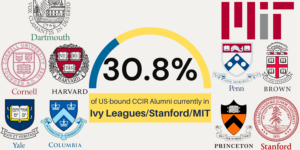

CCIR Academy Featured by Nature, The World’s Most Prestigious Academic Publication

Our Exceptional Alumni: College Admission Results 2020-2023

High School Student Researcher Sailahari’s Paper on Machine Learning Approach in Predicting Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in E. coli Accepted at the MIT URTC 2023

High School Student Researcher Hyojin on Understanding Psychopathy through Structural and Functional MRI

High School Student Researcher Abigail’s Paper on Quantifying Exam Stress Progressions Presented at the IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE) and Published in the IEEE Xplore Journal

Download Programme Prospectus

- Programme structure

- Research course catalogue

- Professor biographies

- Tuition and Scholarship

Start Your Application

Cambridge Future Scholar (Summer 24)

Pre-application is OPEN

Official Admissions Open & Prospectus Release: April 1

Early Admissions Deadline: May 1

Regular Admissions Deadline: May 15

Rolling Admissions.

1-on-1 Research Mentorship Admission is open all year.

How to Write a Research Paper

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Research Paper Fundamentals

How to choose a topic or question, how to create a working hypothesis or thesis, common research paper methodologies, how to gather and organize evidence , how to write an outline for your research paper, how to write a rough draft, how to revise your draft, how to produce a final draft, resources for teachers .

It is not fair to say that no one writes anymore. Just about everyone writes text messages, brief emails, or social media posts every single day. Yet, most people don't have a lot of practice with the formal, organized writing required for a good academic research paper. This guide contains links to a variety of resources that can help demystify the process. Some of these resources are intended for teachers; they contain exercises, activities, and teaching strategies. Other resources are intended for direct use by students who are struggling to write papers, or are looking for tips to make the process go more smoothly.

The resources in this section are designed to help students understand the different types of research papers, the general research process, and how to manage their time. Below, you'll find links from university writing centers, the trusted Purdue Online Writing Lab, and more.

What is an Academic Research Paper?

"Genre and the Research Paper" (Purdue OWL)

There are different types of research papers. Different types of scholarly questions will lend themselves to one format or another. This is a brief introduction to the two main genres of research paper: analytic and argumentative.

"7 Most Popular Types of Research Papers" (Personal-writer.com)

This resource discusses formats that high school students commonly encounter, such as the compare and contrast essay and the definitional essay. Please note that the inclusion of this link is not an endorsement of this company's paid service.

How to Prepare and Plan Out Writing a Research Paper

Teachers can give their students a step-by-step guide like these to help them understand the different steps of the research paper process. These guides can be combined with the time management tools in the next subsection to help students come up with customized calendars for completing their papers.

"Ten Steps for Writing Research Papers" (American University)

This resource from American University is a comprehensive guide to the research paper writing process, and includes examples of proper research questions and thesis topics.

"Steps in Writing a Research Paper" (SUNY Empire State College)

This guide breaks the research paper process into 11 steps. Each "step" links to a separate page, which describes the work entailed in completing it.

How to Manage Time Effectively

The links below will help students determine how much time is necessary to complete a paper. If your sources are not available online or at your local library, you'll need to leave extra time for the Interlibrary Loan process. Remember that, even if you do not need to consult secondary sources, you'll still need to leave yourself ample time to organize your thoughts.

"Research Paper Planner: Timeline" (Baylor University)

This interactive resource from Baylor University creates a suggested writing schedule based on how much time a student has to work on the assignment.

"Research Paper Planner" (UCLA)

UCLA's library offers this step-by-step guide to the research paper writing process, which also includes a suggested planning calendar.

There's a reason teachers spend a long time talking about choosing a good topic. Without a good topic and a well-formulated research question, it is almost impossible to write a clear and organized paper. The resources below will help you generate ideas and formulate precise questions.

"How to Select a Research Topic" (Univ. of Michigan-Flint)

This resource is designed for college students who are struggling to come up with an appropriate topic. A student who uses this resource and still feels unsure about his or her topic should consult the course instructor for further personalized assistance.

"25 Interesting Research Paper Topics to Get You Started" (Kibin)

This resource, which is probably most appropriate for high school students, provides a list of specific topics to help get students started. It is broken into subsections, such as "paper topics on local issues."

"Writing a Good Research Question" (Grand Canyon University)

This introduction to research questions includes some embedded videos, as well as links to scholarly articles on research questions. This resource would be most appropriate for teachers who are planning lessons on research paper fundamentals.

"How to Write a Research Question the Right Way" (Kibin)

This student-focused resource provides more detail on writing research questions. The language is accessible, and there are embedded videos and examples of good and bad questions.

It is important to have a rough hypothesis or thesis in mind at the beginning of the research process. People who have a sense of what they want to say will have an easier time sorting through scholarly sources and other information. The key, of course, is not to become too wedded to the draft hypothesis or thesis. Just about every working thesis gets changed during the research process.

CrashCourse Video: "Sociology Research Methods" (YouTube)

Although this video is tailored to sociology students, it is applicable to students in a variety of social science disciplines. This video does a good job demonstrating the connection between the brainstorming that goes into selecting a research question and the formulation of a working hypothesis.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Analytical Essay" (YouTube)

Students writing analytical essays will not develop the same type of working hypothesis as students who are writing research papers in other disciplines. For these students, developing the working thesis may happen as a part of the rough draft (see the relevant section below).

"Research Hypothesis" (Oakland Univ.)

This resource provides some examples of hypotheses in social science disciplines like Political Science and Criminal Justice. These sample hypotheses may also be useful for students in other soft social sciences and humanities disciplines like History.

When grading a research paper, instructors look for a consistent methodology. This section will help you understand different methodological approaches used in research papers. Students will get the most out of these resources if they use them to help prepare for conversations with teachers or discussions in class.

"Types of Research Designs" (USC)

A "research design," used for complex papers, is related to the paper's method. This resource contains introductions to a variety of popular research designs in the social sciences. Although it is not the most intuitive site to read, the information here is very valuable.

"Major Research Methods" (YouTube)

Although this video is a bit on the dry side, it provides a comprehensive overview of the major research methodologies in a format that might be more accessible to students who have struggled with textbooks or other written resources.

"Humanities Research Strategies" (USC)

This is a portal where students can learn about four methodological approaches for humanities papers: Historical Methodologies, Textual Criticism, Conceptual Analysis, and the Synoptic method.

"Selected Major Social Science Research Methods: Overview" (National Academies Press)

This appendix from the book Using Science as Evidence in Public Policy , printed by National Academies Press, introduces some methods used in social science papers.

"Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: 6. The Methodology" (USC)

This resource from the University of Southern California's library contains tips for writing a methodology section in a research paper.

How to Determine the Best Methodology for You

Anyone who is new to writing research papers should be sure to select a method in consultation with their instructor. These resources can be used to help prepare for that discussion. They may also be used on their own by more advanced students.

"Choosing Appropriate Research Methodologies" (Palgrave Study Skills)

This friendly and approachable resource from Palgrave Macmillan can be used by students who are just starting to think about appropriate methodologies.

"How to Choose Your Research Methods" (NFER (UK))

This is another approachable resource students can use to help narrow down the most appropriate methods for their research projects.

The resources in this section introduce the process of gathering scholarly sources and collecting evidence. You'll find a range of material here, from introductory guides to advanced explications best suited to college students. Please consult the LitCharts How to Do Academic Research guide for a more comprehensive list of resources devoted to finding scholarly literature.

Google Scholar

Students who have access to library websites with detailed research guides should start there, but people who do not have access to those resources can begin their search for secondary literature here.

"Gathering Appropriate Information" (Texas Gateway)

This resource from the Texas Gateway for online resources introduces students to the research process, and contains interactive exercises. The level of complexity is suitable for middle school, high school, and introductory college classrooms.

"An Overview of Quantitative and Qualitative Data Collection Methods" (NSF)

This PDF from the National Science Foundation goes into detail about best practices and pitfalls in data collection across multiple types of methodologies.

"Social Science Methods for Data Collection and Analysis" (Swiss FIT)

This resource is appropriate for advanced undergraduates or teachers looking to create lessons on research design and data collection. It covers techniques for gathering data via interviews, observations, and other methods.

"Collecting Data by In-depth Interviewing" (Leeds Univ.)

This resource contains enough information about conducting interviews to make it useful for teachers who want to create a lesson plan, but is also accessible enough for college juniors or seniors to make use of it on their own.

There is no "one size fits all" outlining technique. Some students might devote all their energy and attention to the outline in order to avoid the paper. Other students may benefit from being made to sit down and organize their thoughts into a lengthy sentence outline. The resources in this section include strategies and templates for multiple types of outlines.

"Topic vs. Sentence Outlines" (UC Berkeley)

This resource introduces two basic approaches to outlining: the shorter topic-based approach, and the longer, more detailed sentence-based approach. This resource also contains videos on how to develop paper paragraphs from the sentence-based outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL)

The Purdue Online Writing Lab's guide is a slightly less detailed discussion of different types of outlines. It contains several sample outlines.

"Writing An Outline" (Austin C.C.)

This resource from a community college contains sample outlines from an American history class that students can use as models.

"How to Structure an Outline for a College Paper" (YouTube)

This brief (sub-2 minute) video from the ExpertVillage YouTube channel provides a model of outline writing for students who are struggling with the idea.

"Outlining" (Harvard)

This is a good resource to consult after completing a draft outline. It offers suggestions for making sure your outline avoids things like unnecessary repetition.

As with outlines, rough drafts can take on many different forms. These resources introduce teachers and students to the various approaches to writing a rough draft. This section also includes resources that will help you cite your sources appropriately according to the MLA, Chicago, and APA style manuals.

"Creating a Rough Draft for a Research Paper" (Univ. of Minnesota)

This resource is useful for teachers in particular, as it provides some suggested exercises to help students with writing a basic rough draft.

Rough Draft Assignment (Duke of Definition)

This sample assignment, with a brief list of tips, was developed by a high school teacher who runs a very successful and well-reviewed page of educational resources.

"Creating the First Draft of Your Research Paper" (Concordia Univ.)

This resource will be helpful for perfectionists or procrastinators, as it opens by discussing the problem of avoiding writing. It also provides a short list of suggestions meant to get students writing.

Using Proper Citations

There is no such thing as a rough draft of a scholarly citation. These links to the three major citation guides will ensure that your citations follow the correct format. Please consult the LitCharts How to Cite Your Sources guide for more resources.

Chicago Manual of Style Citation Guide

Some call The Chicago Manual of Style , which was first published in 1906, "the editors' Bible." The manual is now in its 17th edition, and is popular in the social sciences, historical journals, and some other fields in the humanities.

APA Citation Guide

According to the American Psychological Association, this guide was developed to aid reading comprehension, clarity of communication, and to reduce bias in language in the social and behavioral sciences. Its first full edition was published in 1952, and it is now in its sixth edition.

MLA Citation Guide

The Modern Language Association style is used most commonly within the liberal arts and humanities. The MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing was first published in 1985 and (as of 2008) is in its third edition.

Any professional scholar will tell you that the best research papers are made in the revision stage. No matter how strong your research question or working thesis, it is not possible to write a truly outstanding paper without devoting energy to revision. These resources provide examples of revision exercises for the classroom, as well as tips for students working independently.

"The Art of Revision" (Univ. of Arizona)

This resource provides a wealth of information and suggestions for both students and teachers. There is a list of suggested exercises that teachers might use in class, along with a revision checklist that is useful for teachers and students alike.

"Script for Workshop on Revision" (Vanderbilt University)

Vanderbilt's guide for leading a 50-minute revision workshop can serve as a model for teachers who wish to guide students through the revision process during classtime.

"Revising Your Paper" (Univ. of Washington)

This detailed handout was designed for students who are beginning the revision process. It discusses different approaches and methods for revision, and also includes a detailed list of things students should look for while they revise.

"Revising Drafts" (UNC Writing Center)

This resource is designed for students and suggests things to look for during the revision process. It provides steps for the process and has a FAQ for students who have questions about why it is important to revise.

Conferencing with Writing Tutors and Instructors

No writer is so good that he or she can't benefit from meeting with instructors or peer tutors. These resources from university writing, learning, and communication centers provide suggestions for how to get the most out of these one-on-one meetings.

"Getting Feedback" (UNC Writing Center)

This very helpful resource talks about how to ask for feedback during the entire writing process. It contains possible questions that students might ask when developing an outline, during the revision process, and after the final draft has been graded.

"Prepare for Your Tutoring Session" (Otis College of Art and Design)

This guide from a university's student learning center contains a lot of helpful tips for getting the most out of working with a writing tutor.

"The Importance of Asking Your Professor" (Univ. of Waterloo)

This article from the university's Writing and Communication Centre's blog contains some suggestions for how and when to get help from professors and Teaching Assistants.

Once you've revised your first draft, you're well on your way to handing in a polished paper. These resources—each of them produced by writing professionals at colleges and universities—outline the steps required in order to produce a final draft. You'll find proofreading tips and checklists in text and video form.

"Developing a Final Draft of a Research Paper" (Univ. of Minnesota)

While this resource contains suggestions for revision, it also features a couple of helpful checklists for the last stages of completing a final draft.

Basic Final Draft Tips and Checklist (Univ. of Maryland-University College)

This short and accessible resource, part of UMUC's very thorough online guide to writing and research, contains a very basic checklist for students who are getting ready to turn in their final drafts.

Final Draft Checklist (Everett C.C.)

This is another accessible final draft checklist, appropriate for both high school and college students. It suggests reading your essay aloud at least once.

"How to Proofread Your Final Draft" (YouTube)

This video (approximately 5 minutes), produced by Eastern Washington University, gives students tips on proofreading final drafts.

"Proofreading Tips" (Georgia Southern-Armstrong)

This guide will help students learn how to spot common errors in their papers. It suggests focusing on content and editing for grammar and mechanics.

This final set of resources is intended specifically for high school and college instructors. It provides links to unit plans and classroom exercises that can help improve students' research and writing skills. You'll find resources that give an overview of the process, along with activities that focus on how to begin and how to carry out research.

"Research Paper Complete Resources Pack" (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This packet of assignments, rubrics, and other resources is designed for high school students. The resources in this packet are aligned to Common Core standards.

"Research Paper—Complete Unit" (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This packet of assignments, notes, PowerPoints, and other resources has a 4/4 rating with over 700 ratings. It is designed for high school teachers, but might also be useful to college instructors who work with freshmen.

"Teaching Students to Write Good Papers" (Yale)

This resource from Yale's Center for Teaching and Learning is designed for college instructors, and it includes links to appropriate activities and exercises.

"Research Paper Writing: An Overview" (CUNY Brooklyn)

CUNY Brooklyn offers this complete lesson plan for introducing students to research papers. It includes an accompanying set of PowerPoint slides.

"Lesson Plan: How to Begin Writing a Research Paper" (San Jose State Univ.)

This lesson plan is designed for students in the health sciences, so teachers will have to modify it for their own needs. It includes a breakdown of the brainstorming, topic selection, and research question process.

"Quantitative Techniques for Social Science Research" (Univ. of Pittsburgh)

This is a set of PowerPoint slides that can be used to introduce students to a variety of quantitative methods used in the social sciences.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1895 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 39,904 quotes across 1895 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.