Reading and Case Study Analysis for Social Work

Professor betty kramer, social work 821.

The purpose of this initial assignment is to demonstrate your understanding of the readings and your ability to apply course content to the mental health challenges faced by an elder and their family.

Instructions:

- Review lecture notes from Week 1 and all required readings for Week 1 and Week 2.

- Read the attached case study.

- Preliminary Assessment (Suspicions): Given what Vanessa shares with you, what might you initially suspect is causing her mother’s symptoms and why? Be specific and provide and cite evidence from the reading to support your preliminary assessment.

- Engagement & the Clinical Interview: You will need to do a home visit to initiate the assessment. What will you do in advance to prepare for the interview? How will you approach Mrs. Johnson? What will want to accomplish during this home visit?

- Please list the various domains that you believe will be important to investigate as part of the assessment to determine the cause of Mrs. Johnson’s symptoms and the most appropriate care plan. Be sure to list the mental status tests and medical tests that you feel should be completed (see Ch. 4 McKinnis, 2009; Ch. 6 in Zarit & Zarit). [Note: it is acceptable to provide bulleted list of points in response to these particular questions]

- Describe how that data will be collected (and by whom)?

- Provide a brief rationale for the assessment domains that will be included.

- Possible Recommendations: Assuming your preliminary assessment turns out to be correct, name 2-3 primary recommendations that you might make to Mrs. Johnson and her family?

- Submit paper to Learn@UW dropobox by 9:00 a.m. before week 2 of class.

Daughter Requests Case Manager Consultation for her mother: Mrs. Johnson

Mrs. Johnson (Mrs. J.) is a 78-year-old, African American woman who lives in a small Midwestern city. About a year ago, her husband died suddenly of a stroke, leaving Mrs. J. to live alone in her home of 52 years. It was the home where she had raised her three children, all of whom graduated from college, have professional careers, and now live in other parts of the state. Her family is a source of pride, and her home has numerous pictures of her children and grandchildren.

About 3 months ago, Mrs. J.’s oldest daughter, Vanessa, got a call from one of the neighbors. Vanessa lives a 4-hour drive from her mother—a drive that can often be longer in bad weather. The neighbor stated that Mrs. J. had walked to the neighborhood store in her pajamas and slippers. Because Mrs. J. has lived in the community for several years, people have been watching out for her since her husband died, and someone gave her a ride back home. Mrs. J. doesn’t drive, and the temperature was fairly chilly that day.

As a result of the call, Vanessa went to Mrs. J.’s home for a visit. Although she and her siblings had been calling Mrs. J. regularly, no one had been to the family home in about 7 months. Vanessa was shocked at what she saw. Mrs. J. had been a cook in a school cafeteria earlier in life and always kept her own kitchen spotless. But now the house was in disarray with several dirty pots and pans scattered throughout different rooms. In addition, odd things were in the refrigerator such as a light bulb and several pieces of mail. Many of the food products were out of date, and there was a foul smell in the kitchen. Trash covered the counters and floor.

Vanessa contacted her siblings to ask them if their mother had told any of them that she wasn’t feeling well. Her brother, Anthony, remarked that their mother would often talk about Mr. J. in the present tense—but he thought that it was just her grief about his death. The younger brother, Darius, reported that his wife was typically the one who called their mother—about once a month. He didn’t know if there had been any problems—his wife never said anything about it to him. Vanessa also contacted the pastor of her church, Rev. M. He stated that Mrs. J. had been walking to church on Sundays, as usual, but he did notice that she left early a few times and other times seemed to come to service late. But like the brother, Anthony, he thought that this behavior was probably a grief reaction to the loss of her husband.

A final shock to Vanessa was when she went through her mother’s mail. There were several overdue bills and one urgent notice that the electricity was going to be cut off if the balance wasn’t paid. She owed several hundred dollars in past due heating, electric, and telephone bills.

Vanessa contacted her mother’s primary care physician (Dr. P.) who said that he had last seen Mrs. J. for her regular checkup 6 months earlier and that she had missed her last appointment a week ago. Dr. P. said that her staff had called to make another appointment but that her mother hadn’t called them back yet. Mrs. J. is being treated with medication for arthritis, hypertension, and gastroesophogeal reflux (GERD). Her weight was stable, and her only complaint was some difficulty staying asleep at night. Dr. P. reported that her mother’s mood was sad but had improved some in the month before the last visit. The doctor asked about memory and concentration, but her mother denied having any problems with memory. Imagine that you a case manager at the local Senior Coalition. Vanessa is calling you to seek advice about what to do. She would like you to do an assessment to help her determine what is wrong and how she can best help her mother.

Advertisement

A Case for the Case Study: How and Why They Matter

- Original Paper

- Published: 06 June 2017

- Volume 45 , pages 189–200, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- Jeffrey Longhofer 1 ,

- Jerry Floersch 1 &

- Eric Hartmann 2

3911 Accesses

13 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this special issue we have asked the contributors to make a case for the case study. The guest editors, Jeffrey Longhofer, Jerry Floersch and Eric Hartmann, intergrate ideas from across the disciplines to explore the complexties of case study methods and theory. In education, Gary Thomas explores the importance of ethnographic case studies in understanding the relationships among schools, teachers, and students. Lance Dodes and Josh Dodes use the case study to articulate a psychoanalytic approach to addiction. In policy and generalist practice, Nancy Cartwright and Jeremy Hardie elaborate a model for a case-by-case approach to prediction and the swampy ground prediction serves up to practitioners. Christian Salas and Oliver Turnbull persuasively write about the role of the case study in neuro-psychoanalysis and illustrate it with a case vignette. In political science, Sanford Schram argues for a bottom up and ethnographic approach to studying policy implementation by describing a case of a home ownership program in Philadelphia. Eric Hartman queers the case study by articulating its role in deconstructing normative explanations of sexuality. In applied psychology, Daniel Fishman describes a comprehensive applied psychology perspective on the paradigmatic case study. Richard Miller and Miriam Jaffe offer us important ways of thinking about writing the case study and the use of multi-media. Each contributor brings a unique perspective to the use of the case study in their field, yet they share practical and philosophical assumptions.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: what is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice?

Malin Eriksson, Mehdi Ghazinour & Anne Hammarström

Neurodiversity-Affirming Applied Behavior Analysis

Lauren Lestremau Allen, Leanna S. Mellon, … Armando J. Bernal

The Social Learning Theory of Crime and Deviance

Aastrup, J., & Halldórsson, Á (2008). Epistemological role of case studies in logistics: A critical realist perspective. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 38 (10), 746–763.

Article Google Scholar

Abbott, A. (1992). What do cases do? Some notes on activity in sociological analysis. In C. C. Ragin, & H. S. Becker (Eds.), What is a case?: Exploring the foundations of social inquiry (pp. 53–82). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Ahbel-Rappe, K. (2009). “After a long pause”: How to read Dora as history. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57 (3), 595–629.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Alfonso, C. A. (2002). Frontline—writing psychoanalytic case reports: Safeguarding privacy while preserving integrity. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 30 (2), 165–172.

Altstein, R. (2016). Finding words: How the process and products of psychoanalytic writing can channel the therapeutic action of the very treatment it sets out to describe. Psychoanalytic Perspectives, 13 (1), 51–70.

Anderson, W. (2013). The case of the archive. Critical Inquiry, 39 (3), 532–547.

Antommaria, A. (2004). Do as I say, not as I do: Why bioethicists should seek informed consent for some case studies. Hastings Center Report, 34 (3), 28–34.

Archer, M. S. (2010). Routine, reflexivity, and realism. Sociological Theory , 28 (3), 272–303.

Aron, L. (2000). Ethical considerations in the writing of psychoanalytic case histories. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 10 (2), 231–245.

Aron, L. (2016). Ethical considerations in psychoanalytic writing revisited. Psychoanalytic Perspectives, 13 (3), 267–290.

Barth, M., & Thomas, I. (2012). Synthesising case-study research: Ready for the next step? Environmental Education Research, 18 (6), 751–764.

Benner, P. (1982). From novice to expert. The American Journal of Nursing, 82 (3), 402–407.

PubMed Google Scholar

Benner, P. (2000a). The wisdom of our practice. The American Journal of Nursing, 100 (10), 99–105.

Benner, P. (2000b). The roles of embodiment, emotion and lifeworld for rationality and agency in nursing practice. Nursing Philosophy, 1 (1), 5–19.

Benner, P. (2004). Using the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition to describe and interpret skill acquisition and clinical judgment in nursing practice and education. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 24 (3), 188–199.

Bennett, A., & Elman, C. (2006). Qualitative research: Recent developments in case study methods. Annual Review of Political Science, 9 , 455–476.

Bennett, A., & Elman, C. (2007). Case study methods in the international relations subfield. Comparative Political Studies, 40 (2), 170–195.

Bergene, A. (2007). Towards a critical realist comparative methodology. Journal of Critical Realism, 3 (1), 5–27.

Berlant, L. (2007). On the case. Critical Inquiry, 33 (4), 663–672.

Bernstein, S. B. (2008a). Writing about the psychoanalytic process. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 28 (4), 433–449.

Bernstein, S. B. (2008b). Writing, rewriting, and working through. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 28 (4), 450–464.

Blechner, M. (2012). Confidentiality: Against disguise, for consent. Psychotherapy, 49 (1), 16–18.

Bornstein, R. F. (2007). Nomothetic psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 24 (4), 590–602.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The scholastic point of view. Cultural Anthropology, 5 (4), 380–391.

Bourdieu, P. (2000). Pascalian meditations . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Boyce, N. (2015). Dora in the 21st century. Lancet, 386 (9997), 948–949.

Brandell, J., & Varkas, T. (2010). Narrative case studies. In B. Thyer (Ed.), The handbook of social work research methods (Chap. 20, pp. 375–396). Los Angeles: SAGE

Bunch, W. H., & Dvonch, V. M. (2000). Moral decisions regarding innovation: The case method. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 378 , 44–49.

Burawoy, M. (1998). The extended case method. Sociological theory, 16 (1), 4–33.

Campbell, D. T. (1975). “Degrees of freedom” and the case study. Comparative Political Studies, 8 (2), 178–193.

Carlson, J. (2010). Commentary: Writing about clients—ethical and professional issues in clinical case reports. Counseling and Values, 54 (2), 154–157.

Cartwright, N. (2007). Are RCTs the gold standard? BioSocieties, 2 (1), 11–20.

Cartwright, N. (2011). A philosopher’s view of the long road from RCTs to effectiveness. Lancet, 377 (9775), 1400–1401.

Charlton, B. G., & Walston, F. (1998). Individual case studies in clinical research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 4 (2), 147–155.

Colombo, D., & Michels, R. (2007). Can (should) case reports be written for research use? Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 27 (5), 640–649.

Damousi, J., Lang, B., & Sutton, K. (Eds.) (2015). Case studies and the dissemination of knowledge . London: Routledge Press.

Desmet, M., Meganck, R., Seybert, C., Willemsen, J., Geerardyn, F., Declercq, F., & Schindler, I. (2012). Psychoanalytic single cases published in ISI-ranked journals: The construction of an online archive. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82 (2), 120–121.

Dobson, P. J. (2001). Longitudinal case research: A critical realist perspective. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 14 (3), 283–296.

Dreyfus, H. L. (2008). On the internet . London: Routledge Press.

Dreyfus, H. L., & Dreyfus, S. E. (2005). Peripheral vision expertise in real world contexts. Organization Studies, 26 (5), 779–792.

Easton, G. (2010). Critical realism in case study research. Industrial Marketing Management, 39 (1), 118–128.

Edelson, M. (1985). The hermeneutic turn and the single case study in psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis & Contemporary Thought, 8 , 567–614.

Feagin, J. R., Orum, A. M., & Sjoberg, G. (Eds.) (1991). A case for the case study . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Ferguson, H. (2016). Researching social work practice close up: Using ethnographic and mobile methods to understand encounters between social workers, children and families. British Journal of Social Work, 46 (1), 153–168.

Fisher, M. A. (2013). The ethics of conditional confidentiality: A practice model for mental health professionals . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Fleischman, J. (2002). Phineas Gage: A gruesome but true story about brain science . New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Floersch, J. (2000). Reading the case record: The oral and written narratives of social workers. Social Service Review, 74 (2), 169–192.

Floersch, J. (2002). Meds, money, and manners: The case management of severe mental illness . Columbia: Columbia University Press.

Floersch, J., & Longhofer, J. (2016). Social work and the scholastic fallacy. Investigacao Em Trabalho Social, 3 , 71–91. https://www.isssp.pt/si/web_base.gera_pagina?p_pagina=21798 .

Florek, A. G., & Dellavalle, R. P. (2016). Case reports in medical education: A platform for training medical students, residents, and fellows in scientific writing and critical thinking. Journal of Medical Case Reports, 10 (1), 1.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

Flyvbjerg, B., Landman, T., & Schram, S. (Eds.). (2012). Real social science: Applied phronesis . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forrester, J. (1996). If p, then what? Thinking in cases. History of the Human Sciences, 9 (3), 1–25.

Forrester, J. (2007). On Kuhn’s case: Psychoanalysis and the paradigm. Critical Inquiry, 33 (4), 782–819.

Foucault, M. (1994). The birth of the clinic: An archaeology of medical perception . London: Routledge Press.

Freeman, W. J. (2000). How brains make up their minds . New York: Columbia University Press.

Freud, S. (1905). Fragment of an analysis of a case of hysteria. Standard Edition , 7 , 7–122.

Freud, S. (1909a). Analysis of a phobia in a five-year-old boy. Standard Edition , 10 , 5–147.

Freud, S. (1909b). Notes upon a case of obsessional neurosis. Standard Edition , 10 , 151–318.

Freud, S. (1911). Psycho-analytic notes on an autobiographical account of a case of paranoia (dementia paranoides). Standard Edition , 12 , 9–79.

Freud, S. (1918). From the history of an infantile neurosis. Standard Edition , 17 , 7–122.

George, A. L. & Bennett, A. (2004). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? American Political Science Review, 98 (02), 341–354.

Gerring, J. (2007a). Case study research: Principles and practices . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gerring, J. (2007b). Is there a (viable) crucial-case method? Comparative Political Studies, 40 (3), 231–253.

Gilgun, J. F. (1994). A case for case studies in social work research. Social Work, 39 , 371–380.

Gottdiener, W. H., & Suh, J. J. (2012). Expanding the single-case study: A proposed psychoanalytic research program. The Psychoanalytic Review, 99 (1), 81–102.

Gupta, M. (2007). Does evidence-based medicine apply to psychiatry? Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 28 (2), 103–120.

Gupta, M. (2014). Is evidence-based psychiatry ethical? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gwande, A. (2014). Being mortal: Medicine and what matters most in the end . New York: Metropolitan Books.

Haas, L. (2001). Phineas Gage and the science of brain localisation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 71 (6), 761.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hacking, I. (1999). The social construction of what? Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Haggis, T. (2008). ‘Knowledge must be contextual’: Some possible implications of complexity and dynamic systems theories for educational research. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40 (1), 158–176.

Hare-Mustin, R. T. (1983). An appraisal of the relationship between women and psychotherapy: 80 years after the case of Dora. American Psychologist, 38 (5), 593–601.

Held, B. S. (2009). The logic of case-study methodology. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 5 (3), 90–100.

Hoffman, I. Z. (2009). Doublethinking our way to “scientific” legitimacy: The desiccation of human experience. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57 (5), 1043–1069.

Hollan, D., & Throop, C. J. (2008). Whatever happened to empathy?: Introduction. Ethos, 36 (4), 385–401.

Hurwitz, B. (2011). Clinical cases and case reports: Boundaries and porosities. The Case and the Canon. Anomalies, Discontinuities, Metaphors Between Science and Literature , 45–57.

Ioannidis, J. P., Haidich, A. B., & Lau, J. (2001). Any casualties in the clash of randomized and observational evidence? British Medical Journal, 322 , 879–880.

Iosifides, T. (2012). Migration research between positivistic scientism and relativism: A critical realist way out. In C. Vargas-Silva (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in migration (pp. 26–49). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kächele, H., Schachter, J., & Thomä, H. (2011). From psychoanalytic narrative to empirical single case research: Implications for psychoanalytic practice (vol. 30). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Kantrowitz, J. L. (2004). Writing about patients: I. Ways of protecting confidentiality and analysts’ conflicts over choice of method. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 52 (1), 69–99.

Ketokivi, M., & Choi, T. (2014). Renaissance of case research as a scientific method. Journal of Operations Management, 32 (5), 232–240.

Kitchin, R. (2014a). Big data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts. Big Data & Society, 1 (1), 1–12.

Kitchin, R. (2014b). The data revolution: Big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press.

Kitchin, R., & Lauriault, T. P. (2015). Small data in the era of big data. GeoJournal, 80 (4), 463–475.

Koenig, G. (2009). Realistic evaluation and case studies stretching the potential. Evaluation, 15 (1), 9–30.

Lahire, B. (2011). The plural actor . Cambridge: Polity.

Leong, S. M. (1985). Metatheory and metamethodology in marketing, a lakatosian reconstruction. Journal of Marketing, 49 (4), 23–40.

Levy, J. S. (2008). Case studies: Types, designs, and logics of inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25 (1), 1–18.

Longhofer, J., & Floersch, J. (2012). The coming crisis in social work: Some thoughts on social work and science. Research on Social Work Practice, 22 (5), 499–519.

Longhofer, J., & Floersch, J. (2014). Values in a science of social work: Values-informed research and research-informed values. Research on Social Work Practice, 24 (5), 527–534.

Longhofer, J., Floersch, J., & Hoy, J. (2013). Qualitative methods for practice research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luyten, P., Corveleyn, J., & Blatt, S. J. (2006). Minding the gap between positivism and hermeneutics in psychoanalytic research. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 54 (2), 571–610.

Macmillan, M. (2000). Restoring phineas gage: A 150th retrospective. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 9 (1), 46–66.

Mahoney, J., Kimball, E., & Koivu, K. L. (2009). The logic of historical explanation in the social sciences. Comparative Political Studies, 42 (1), 114–146.

Marchal, B., Westhorp, G., Wong, G., Van Belle, S., Greenhalgh, T., Kegels, G., & Pawson, R. (2013). Realist RCTs of complex interventions: An oxymoron. Social Science & Medicine, 94 (12), 124–128.

Maroglin, L. (1997). Under the cover of kindness. The invention of social work . Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

McKeown, A. (2015). Critical realism and empirical bioethics: A methodological exposition. Health Care Analysis, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10728-015-0290-2 .

McLeod, J. (2010). Case study research in counseling and psychotherapy . Thousand Oaks, LA: Sage Publications.

McLeod, J. (2015). Reading case studies to inform therapeutic practice. In Psychotherapie forum (vol. 20, No. 1–2, pp. 3–9). Vienna: Springer.

McLeod, J., & Balamoutsou, S. (1996). Representing narrative process in therapy: Qualitative analysis of a single case. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 9 (1), 61–76.

Mearsheimer, J. J., & Walt, S. M. (2013). Leaving theory behind: Why simplistic hypothesis testing is bad for international relations. European Journal of International Relations, 19 (3), 427–457.

Michels, R. (2000). The case history. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 48 (2), 355–375.

Miller, E. (2009). Writing about patients: What clinical and literary writers share. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57 (5), 1097–1120.

Mingers, J. (2004). Realizing information systems: Critical realism as an underpinning philosophy for information systems. Information and Organization, 14 (2), 87–103.

Mishna, F. (2004). A qualitative study of bullying from multiple perspectives. Children & Schools, 26 (4), 234–247.

Mittelstadt, B. D., Allo, P., Taddeo, M., Wachter, S., & Floridi, L. (2016). The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data & Society , 3(2), 2053951716679679

Morgan, M. S. (2012). Case studies: One observation or many? Justification or discovery? Philosophy of Science, 79 (5), 667–677.

Naiburg, S. (2015). Structure and spontaneity in clinical prose: A writer’s guide for psychoanalysts and psychotherapists . London: Routledge Press.

Nissen, T., & Wynn, R. (2014a). The clinical case report: A review of its merits and limitations. BMC Research Notes, 7 (1), 1–7.

Nissen, T., & Wynn, R. (2014b). The history of the case report: A selective review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Open, 5 (4), 1–5. doi: 10.1177/2054270414523410 .

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy . New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Payne, S., Field, D., Rolls, L., Hawker, S., & Kerr, C. (2007). Case study research methods in end-of-life care: Reflections on three studies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58 (3), 236–245.

Perry, C. (1998). Processes of a case study methodology for postgraduate research in marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 32 (9/10), 785–802.

Pinter, H. (1982). A kind of alaska: A premier . Retrieved from http://www.haroldpinter.org/plays/plays_alaska.shtml .

Probst, B. (2015). The eye regards itself: Benefits and challenges of reflexivity in qualitative social work research. Social Work Research Social Work Research , 39 (1), 37–48.

Romano, C. (2015). Freud and the Dora case: A promise betrayed . London: Karnac Books.

Ruddin, L. P. (2006). You can generalize stupid! Social scientists, Bent Flyvbjerg, and case study methodology. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (4), 797–812.

Sacks, O. (1970). The man who mistook his wife for a hat . New York: Touchstone.

Sacks, O. (1995). An anthropologist on mars: Seven paradoxical tales . New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Sacks, O. (2015). On the move: A life . New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Safran, J. D. (2009). Clinical and empirical issues: Disagreements and agreements. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57 (5), 1043–1069.

Sampson, R. J. (2010). Gold standard myths: Observations on the experimental turn in quantitative criminology. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26 (4), 489–500.

Sayer, A. (2011). Why things matter to people: Social science, values and ethical life . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shaw, E. (2013). Sacred cows and sleeping dogs: Confidentiality: Not as straightforward as we would have thought. Psychotherapy in Australia, 19 (4), 65–66.

Sieck, B. C. (2012). Obtaining clinical writing informed consent versus using client disguise and recommendations for practice. Psychotherapy, 49 (1), 3–11.

Siggelkow, N. (2007). Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal, 50 (1), 20–24.

Skocpol, T., & Sommers, M. (1980). The uses of comparative theory in macrosocial inquiry. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 22 (2), 174–197.

Smith, C. (2011). What is a person?: Rethinking humanity, social life, and the moral good from the personup . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sperry, L., & Pies, R. (2010). Writing about clients: Ethical considerations and options. Counseling and Values, 54 (2), 88–102.

Steinmetz, G. (2004). Odious comparisons: Incommensurability, the case study, and “small N’s” in sociology. Sociological Theory, 22 (3), 371–400.

Steinmetz, G. (2005). The politics of method in the human. In G. Steinmetz (Ed.), Sciences . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sutherland, E. (2016). The case study in telecommunications policy research. Info, 18 (1), 16–30.

Taylor, C., & White, S. (2001). Knowledge, truth and reflexivity: The problem of judgement in social work. Journal of social work , 1 (1), 37–59.

Taylor, C., & White, S. (2006). Knowledge and reasoning in social work: Educating for humane judgement. British Journal of Social Work , 36 (6), 937–954.

Thacher, D. (2006). The Normative Case Study 1. American journal of sociology , 111 (6), 1631–1676.

Tice, K. W. (1998). Tales of wayward girls and immoral women: Case records and the professionalization of social work . Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Tsang, E. W. (2014). Case studies and generalization in information systems research: A critical realist perspective. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 23 (2), 174–186.

Tsang, E. W. (2014). Generalizing from research findings: The merits of case studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16 (4), 369–383.

Tufekci, Z. (2015). Algorithmic harms beyond Facebook and Google: Emergent challenges of computational agency. Journal on Telecommunication, 13 , 203–218.

Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research: A guide for organizational and social research . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Haselen, R. A. (2015). Towards improving the reporting quality of clinical case reports in complementary medicine: Assessing and illustrating the need for guideline development. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 23 (2), 141–148.

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42 (5), 740–762.

Wilgus, J., & Wilgus, B. (2009). Face to face with Phineas Gage. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 18 (3), 340–345.

Willemsen, J., Cornelis, S., Geerardyn, F. M., Desmet, M., Meganck, R., Inslegers, R., & Cauwe, J. M. (2015). Theoretical pluralism in psychoanalytic case studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 6 , 1466

Willemsen, J., Della Rosa, E., & Kegerreis, S. (2017). Clinical case studies in psychoanalytic and psychodynamic treatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 8 , 1–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00108 .

Winship, G. (2007). The ethics of reflective research in single case study inquiry. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 43 (4), 174–182.

Wolpert, L., & Fonagy, P. (2009). There is no place for the psychoanalytic case report in the British Journal of Psychiatry. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195 , 483–487.

Woolcock, M. (2013). Using case studies to explore the external validity of ‘complex’ development interventions. Evaluation, 19 (3), 229–248.

Wynn, D. Jr., & Williams, C. K. (2012). Principles for conducting critical realist case study research in information systems. Mis Quarterly, 36 (3), 787–810.

Yang, D. D. (2006). Empirical social inquiry and models of causal inference. The New England Journal of Political Science, 2 (1), 51–88.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Rutgers School of Social Work, New Brunswick, USA

Jeffrey Longhofer & Jerry Floersch

DSW Program, Rutgers School of Social Work, New Brunswick, USA

Eric Hartmann

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeffrey Longhofer .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Longhofer, J., Floersch, J. & Hartmann, E. A Case for the Case Study: How and Why They Matter. Clin Soc Work J 45 , 189–200 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-017-0631-8

Download citation

Published : 06 June 2017

Issue Date : September 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-017-0631-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Case study research

- Critical realism

- Psychoanaltyic case study

- Social work clinical research

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Report Writing for Social Workers

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

This is a useful and largely accessible text that I hope will be helpful to our students. It is helpful to have a book specifically addressing this essential skill as it is a common complaint of empoyers that students learn to write essays but not reports.

This book follows the valuable tenets of the learning matters series: A clear, accessible overview of report writing. Thought-provoking case examples illustrate the complexities and challenges of report writing in social work, offering qualifying students valuable insights within which to contextualise development of their report writing skills.

This is a good read for all social workers. The text is very practical and provides the reader with the confidence to follow suggestions made in the book. A must read for all social workers, particularly if in practice, or teaching students social workers in practice.

A useful resource for social work students, many of whom find writing reports a major challenge

Used a supplementary reading to a course we run based on report writing. Good case studies with clear information.

This book deals competently and clearly the essentials of report writing at a basic level for beginning undergraduate students. At the present time many students struggle with writing skills (!), and the book is useful to recommend further along the education continuum also in particular cases.

I have delivered a annual course in report writing to various government agencies for almost ten years, and so I looked forward to reading this work. It did not disappoint. The structure and content of this book make it eminently 'useable' and useful.

Although it is still early in the course, I have already used this book extensively with my honours students, including exercises in probation report writing, and theory to practice reflection reports. It has been very well received by my students, a number of whom have already purchased this book for themselves. I highly recommend this work and I look forward to using it for the rest of the honours course.

When I is the title of this book I was excited as I thought it would be very relevant to my role as a practice educator supporting social workers in training on PLO1 & 2 at both undergraduate and Masters levels. However the book for me falls short, both in what it includes and the level of detail. For example in defining "report" -- what to include -- I would have hoped for sections on writing case files, the importance of chronologies etc. In the section on notetaking there are only three points made and I find social workers in training need far more than this. For example it could have included different styles of notetaking such as using spider diagrams; the use of abbreviations; using a timeline with service users which shares the power of recording as it is done together. I would have hoped for a section on how focusing on a form in report writing can be a barrier to communication.

The section on "what to leave out "on page 69 really disappoints. It gives the example of a sentence "Mr M had a difficult childhood". It does not highlight that "difficult" can mean different things to different people and the importance of not using such value judgement words in reports and records but rather replacing them with descriptors. In this section it would have been helpful to include examples of unnecessary details that often we see written in reports. As a result I have just ordered an inspection copy of the Karen Healy book on writing skills for social workers and I'm hoping for more from this.

Currently one of the skills social workers need to develop hi lighted by the reform board agenda. It is useful top use individually and in group sessions.

Clear and concise. Useful pointers for the basics of report writing often overlooked by practitioners.

Perhaps could have had section on requirements of court rules governing reporting.

Preview this book

For instructors, select a purchasing option, related products.

Text for Mobile

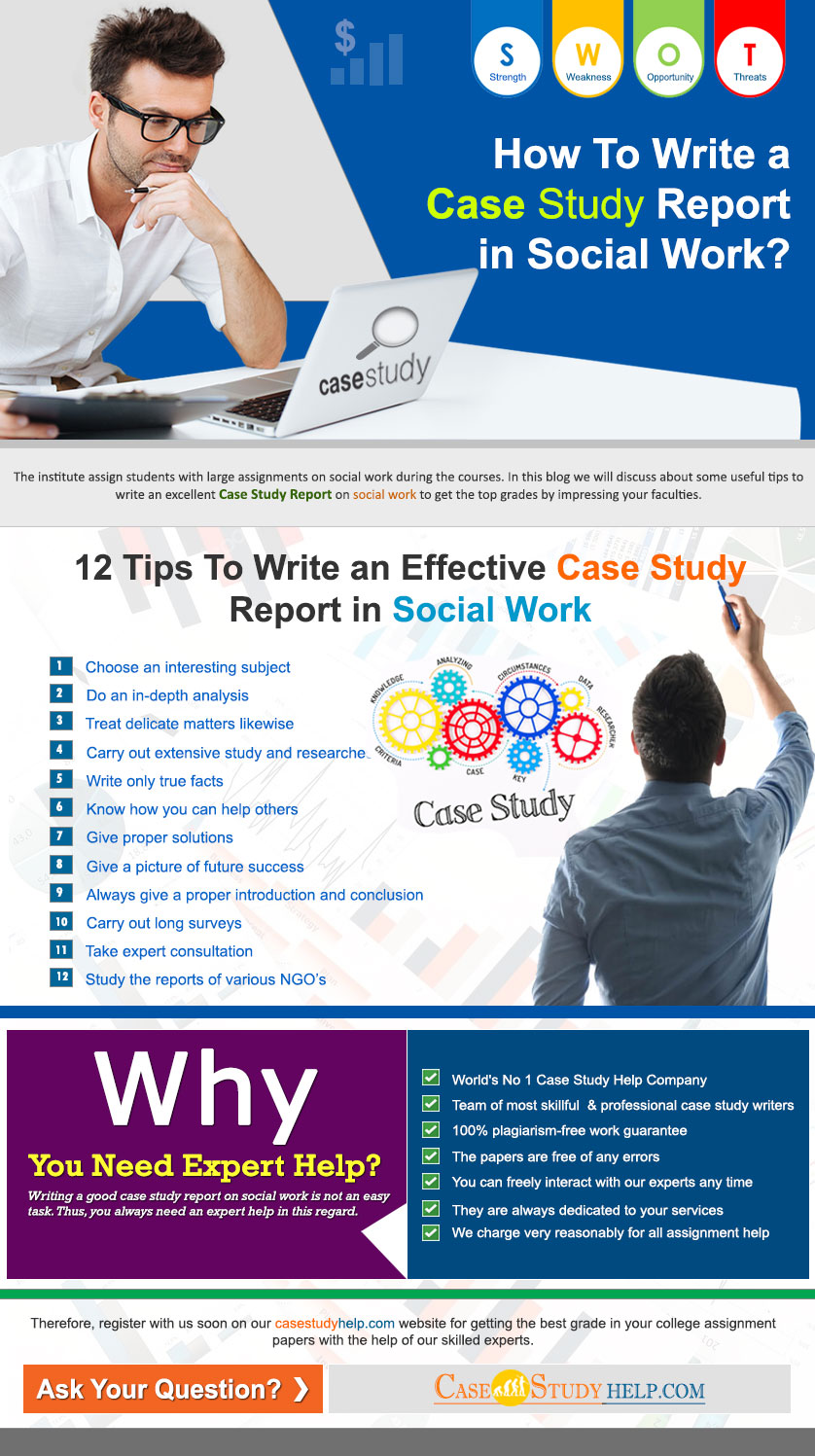

How To Write A Case Study Report In Social Work?

Social work is one of the most important branches or streams of study for students in Australia and around the world. The subject has become so important that even reputed colleges and universities of Australia are offering graduation and postgraduate degree courses in social work.

The institute assigns students large assignments on social work during the courses. In this blog, we will discuss some useful tips for writing an excellent case study report on social work to impress your faculty and get the top grades .

Tips To Write an Effective Case Study Report in Social Work

- Choose an interesting subject: First, you need to choose a very interesting and updated subject for your social work case study. Some such subjects might be domestic violence, corruption, women’s empowerment, drug abuse, and alcohol abuse.

- Do an in-depth analysis: After that, you need to analyse the chosen subject or topic in-depth. You need to explain each and every fact related to that topic. No fiction should be there. Only try, and you will accept the current facts.

- Treat delicate matters likewise: A study on social work is one of the most delicate types of studies in the world. Thus, you need to write your report by treating the matter as seriously as possible and avoiding all types of fluffy language.

- Carry out extensive study and research: You always need to do extensive study and research while writing your case study report on social work. You need to note all the legal, social, and political status of the country, territory, or region in which you are doing your social study.

- Write only true facts: You must always write only true facts in your case study. Writing wrong facts can be very harmful to your paper. You always need to depict a very true picture of the scenario.

- Know how you can help others: The ultimate aim of your social study work is to help the people of your society. Each class of people suffers from particular issues or problems. You need to deal with their issues likewise to solve their problems. Thus, you always need to know the right methods to solve various problems of the suffering people.

- Give proper solutions: You must always give proper solutions to the suffering people of your society to overcome their problems. These solutions must be strictly within the legal limits of your nation. You must keep in mind that people truly benefit from the suggestions and solutions provided by you in your social work case study report.

- Give a picture of future success: In your case study report on social work, you need to depict a true picture of your social work project’s success in the long run and how it will benefit people in the concluding part.

- Always give a proper introduction and conclusion: The introduction and concluding part of your social work case study report are of high importance. The introductory part makes the first impression on your readers. If your concluding part is interesting enough, it will create an everlasting good impression on your reader faculty. Thus, you are bound to get good grades.

- Carry out long surveys: The subject of social work is very much related to practical surveys and studies. Thus, you need to conduct a lot of surveys among the people of society to learn about their real problems in life and find effective solutions for them.

- Take expert consultation: To write an ideal case study report, it is advisable to seek consultation and help from a social service expert. You need to do this under the supervision of an expert social worker.

- Study the reports of various NGOs: There are a number of NGOs or non-government organisations involved in various social studies. You can read their published reports to get an idea of how to do proper social work with true success.

What Common Mistakes Should Be Avoided While Writing a Case Study Report?

You need to avoid certain common mistakes while writing a case study report on social work or any other subject. Some of these are listed below:

- Many errors are often present in the case study paper. You always need to remove these errors by properly proofreading and editing the papers. Manual checking is preferred in this regard rather than any error-detecting software.

- You always need to avoid plagiarism in your report work. You can also use any kind of updated and advanced plagiarism-checking software technology in this regard in order to make your paper a hundred per cent plagiarism-free

- Always submit all your case study papers before the deadlines. If you cross the deadlines, your paper will come under the defaulter list, and you will lose your grades

- Try to complete all your assignment papers within specified time frames

- Do not repeat any idea more than once in any of your case study papers. Add new ideas with to-the-point explanations. This will make your paper more interesting.

How do you avail yourself of the Case Study Report Writing Services?

Writing a good case study report on social work is not an easy task. Thus, you always need expert help in this regard. You can get the best case study report on social work writing help from the most reputed C aseStudyHelp.com online organisation.

We have a team of the best writers with extensive experience in the social service case report writing field. Thus, students can always expect the best service from them. You can easily avail of our services by registering online on the CaseStudyHelp.com official website . We are always here to provide the best solutions for writing social work case study reports.

Author Bio:

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.

- Analysis relies too much on opinion . Your analysis is interpretive, but the narrative must be connected clearly to evidence from the case and any models and theories discussed in class or in course readings. Any positions or arguments you make should be supported by evidence.

- Analysis does not focus on the most important elements of the case . Your paper should provide a thorough overview of the case. However, the analysis should focus on providing evidence about what you identify are the key events, stakeholders, issues, and problems. Emphasize what you identify as the most critical aspects of the case to be developed throughout your analysis. Be thorough but succinct.

- Writing is too descriptive . A paper with too much descriptive information detracts from your analysis of the complexities of the case situation. Questions about what happened, where, when, and by whom should only be included as essential information leading to your examination of questions related to why, how, and for what purpose.

- Inadequate definition of a core problem and associated symptoms . A common error found in case analysis papers is recommending a solution or course of action without adequately defining or demonstrating that you understand the problem. Make sure you have clearly described the problem and its impact and scope within the organizational setting. Ensure that you have adequately described the root causes w hen describing the symptoms of the problem.

- Recommendations lack specificity . Identify any use of vague statements and indeterminate terminology, such as, “A particular experience” or “a large increase to the budget.” These statements cannot be measured and, as a result, there is no way to evaluate their successful implementation. Provide specific data and use direct language in describing recommended actions.

- Unrealistic, exaggerated, or unattainable recommendations . Review your recommendations to ensure that they are based on the situational facts of the case. Your recommended solutions and courses of action must be based on realistic assumptions and fit within the constraints of the situation. Also note that the case scenario has already happened, therefore, any speculation or arguments about what could have occurred if the circumstances were different should be revised or eliminated.

Bee, Lian Song et al. "Business Students' Perspectives on Case Method Coaching for Problem-Based Learning: Impacts on Student Engagement and Learning Performance in Higher Education." Education & Training 64 (2022): 416-432; The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Georgallis, Panikos and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching using Case-Based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Georgallis, Panikos, and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching Using Case-based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; .Dean, Kathy Lund and Charles J. Fornaciari. "How to Create and Use Experiential Case-Based Exercises in a Management Classroom." Journal of Management Education 26 (October 2002): 586-603; Klebba, Joanne M. and Janet G. Hamilton. "Structured Case Analysis: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in a Marketing Case Course." Journal of Marketing Education 29 (August 2007): 132-137, 139; Klein, Norman. "The Case Discussion Method Revisited: Some Questions about Student Skills." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 30-32; Mukherjee, Arup. "Effective Use of In-Class Mini Case Analysis for Discovery Learning in an Undergraduate MIS Course." The Journal of Computer Information Systems 40 (Spring 2000): 15-23; Pessoa, Silviaet al. "Scaffolding the Case Analysis in an Organizational Behavior Course: Making Analytical Language Explicit." Journal of Management Education 46 (2022): 226-251: Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Schweitzer, Karen. "How to Write and Format a Business Case Study." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/how-to-write-and-format-a-business-case-study-466324 (accessed December 5, 2022); Reddy, C. D. "Teaching Research Methodology: Everything's a Case." Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 18 (December 2020): 178-188; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

Writing Tip

Ca se Study and Case Analysis Are Not the Same!

Confusion often exists between what it means to write a paper that uses a case study research design and writing a paper that analyzes a case; they are two different types of approaches to learning in the social and behavioral sciences. Professors as well as educational researchers contribute to this confusion because they often use the term "case study" when describing the subject of analysis for a case analysis paper. But you are not studying a case for the purpose of generating a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of a research problem. R ather, you are critically analyzing a specific scenario to argue logically for recommended solutions and courses of action that lead to optimal outcomes applicable to professional practice.

To avoid any confusion, here are twelve characteristics that delineate the differences between writing a paper using the case study research method and writing a case analysis paper:

- Case study is a method of in-depth research and rigorous inquiry ; case analysis is a reliable method of teaching and learning . A case study is a modality of research that investigates a phenomenon for the purpose of creating new knowledge, solving a problem, or testing a hypothesis using empirical evidence derived from the case being studied. Often, the results are used to generalize about a larger population or within a wider context. The writing adheres to the traditional standards of a scholarly research study. A case analysis is a pedagogical tool used to teach students how to reflect and think critically about a practical, real-life problem in an organizational setting.

- The researcher is responsible for identifying the case to study; a case analysis is assigned by your professor . As the researcher, you choose the case study to investigate in support of obtaining new knowledge and understanding about the research problem. The case in a case analysis assignment is almost always provided, and sometimes written, by your professor and either given to every student in class to analyze individually or to a small group of students, or students select a case to analyze from a predetermined list.

- A case study is indeterminate and boundless; a case analysis is predetermined and confined . A case study can be almost anything [see item 9 below] as long as it relates directly to examining the research problem. This relationship is the only limit to what a researcher can choose as the subject of their case study. The content of a case analysis is determined by your professor and its parameters are well-defined and limited to elucidating insights of practical value applied to practice.

- Case study is fact-based and describes actual events or situations; case analysis can be entirely fictional or adapted from an actual situation . The entire content of a case study must be grounded in reality to be a valid subject of investigation in an empirical research study. A case analysis only needs to set the stage for critically examining a situation in practice and, therefore, can be entirely fictional or adapted, all or in-part, from an actual situation.

- Research using a case study method must adhere to principles of intellectual honesty and academic integrity; a case analysis scenario can include misleading or false information . A case study paper must report research objectively and factually to ensure that any findings are understood to be logically correct and trustworthy. A case analysis scenario may include misleading or false information intended to deliberately distract from the central issues of the case. The purpose is to teach students how to sort through conflicting or useless information in order to come up with the preferred solution. Any use of misleading or false information in academic research is considered unethical.

- Case study is linked to a research problem; case analysis is linked to a practical situation or scenario . In the social sciences, the subject of an investigation is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to generate new knowledge leading to a solution. Case analysis narratives are grounded in real life scenarios for the purpose of examining the realities of decision-making behavior and processes within organizational settings. A case analysis assignments include a problem or set of problems to be analyzed. However, the goal is centered around the act of identifying and evaluating courses of action leading to best possible outcomes.

- The purpose of a case study is to create new knowledge through research; the purpose of a case analysis is to teach new understanding . Case studies are a choice of methodological design intended to create new knowledge about resolving a research problem. A case analysis is a mode of teaching and learning intended to create new understanding and an awareness of uncertainty applied to practice through acts of critical thinking and reflection.

- A case study seeks to identify the best possible solution to a research problem; case analysis can have an indeterminate set of solutions or outcomes . Your role in studying a case is to discover the most logical, evidence-based ways to address a research problem. A case analysis assignment rarely has a single correct answer because one of the goals is to force students to confront the real life dynamics of uncertainly, ambiguity, and missing or conflicting information within professional practice. Under these conditions, a perfect outcome or solution almost never exists.

- Case study is unbounded and relies on gathering external information; case analysis is a self-contained subject of analysis . The scope of a case study chosen as a method of research is bounded. However, the researcher is free to gather whatever information and data is necessary to investigate its relevance to understanding the research problem. For a case analysis assignment, your professor will often ask you to examine solutions or recommended courses of action based solely on facts and information from the case.

- Case study can be a person, place, object, issue, event, condition, or phenomenon; a case analysis is a carefully constructed synopsis of events, situations, and behaviors . The research problem dictates the type of case being studied and, therefore, the design can encompass almost anything tangible as long as it fulfills the objective of generating new knowledge and understanding. A case analysis is in the form of a narrative containing descriptions of facts, situations, processes, rules, and behaviors within a particular setting and under a specific set of circumstances.

- Case study can represent an open-ended subject of inquiry; a case analysis is a narrative about something that has happened in the past . A case study is not restricted by time and can encompass an event or issue with no temporal limit or end. For example, the current war in Ukraine can be used as a case study of how medical personnel help civilians during a large military conflict, even though circumstances around this event are still evolving. A case analysis can be used to elicit critical thinking about current or future situations in practice, but the case itself is a narrative about something finite and that has taken place in the past.

- Multiple case studies can be used in a research study; case analysis involves examining a single scenario . Case study research can use two or more cases to examine a problem, often for the purpose of conducting a comparative investigation intended to discover hidden relationships, document emerging trends, or determine variations among different examples. A case analysis assignment typically describes a stand-alone, self-contained situation and any comparisons among cases are conducted during in-class discussions and/or student presentations.

The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017; Crowe, Sarah et al. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (2011): doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Works

- Next: Writing a Case Study >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

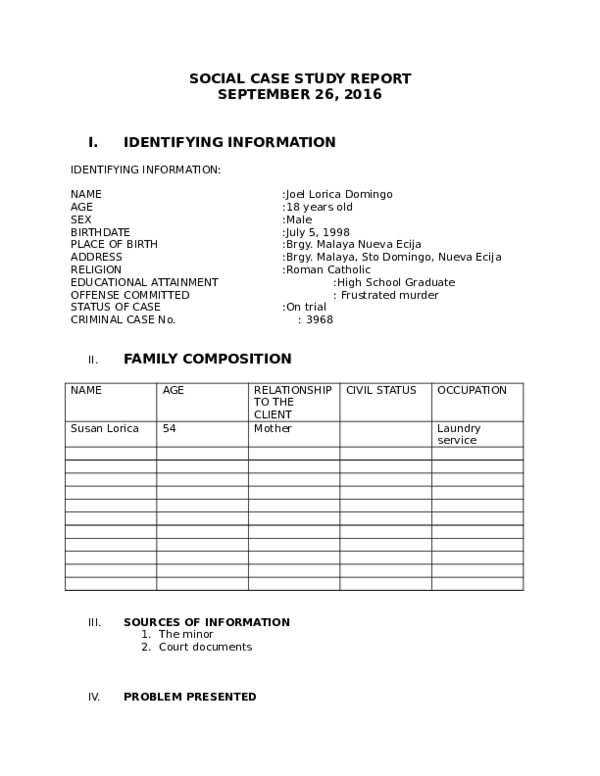

SOCIAL CASE STUDY REPORT SEPTEMBER 26, 2016 IDENTIFYING INFORMATION

Related Papers

International Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research

Argel B . Masanda

This study investigated the children"s experiences of the familial stresses as a gauge of looking into their family dynamics. Primary emphasis was focused on the children"s psychological functioning in the context of their experienced stresses in their family. Creative expressive approaches were utilized to facilitate data gathering from 3 abused children who were housed in a government facility. The 3 girls suffered physical and/or sexual abuse, neglect and/or abandonment or the combinations of those. Qualitative analyses (genogram and thematic analysis) were employed to make sense of the data. Results suggested that children"s experiences of societal stresses can be ranged from intrafamilial (from "within" the family) to extrafamilial (from "without" the family). In spite of being under too much stress, children were observed to be authentic "family mirrors": they can precisely measure and showcase the family"s dynamics including emotional patterns and overall functioning in an effortless and subconscious ways. This suggested that their experiences of stress seemed to be subliminal-they have a natural way of making sense of their experiences through their sheer ability to catch and understand the emotional contents of the messages they receive from the world, albeit uncritically. Hence, children"s behavior (or misbehavior) and ineffective ways of coping from their stressful experiences, tend to be a viable measure in appraising their family"s dynamics. Furthermore, it was likewise conclusive that marital relationship seemed to be a pivotal point in the maintenance of the family equilibrium.

The law of succession in Roman Egypt: Siblings and Non-siblings disputes over inheritance In: Proceedings of the 28th International Congress of Papyrology Barcelona 1-6 August 2016, Scripta Orientalia 3, Barcelona 2019, 475-483.

Marianna Thoma

Papyrus documents give evidence that in the multicultural society of Roman Egypt all children regardless their legal status inherited their father and after the SC Orfitianum of AD 178 children of Roman status could inherit their mothers. However, numerous petitions prove that various conflicts arose between family members especially about the division of parental property. For example, in P.Lond. II 177 (1st c. AD) the eldest sister of a family with her husband grabbed the paternal furniture and utensils, which also belonged to her brothers in terms of their father’s will. The conflicts between an heir and his guardian about the disposition of the inheritance are also common. In P.Oxy. XVII 2133 (4th c. AD) a daughter complains to the prefect, because her uncle-guardian deprived her of her share to the paternal inheritance in the form of dowry. While family conflicts about intestate succession and wills were a common phenomenon, the papyri give also evidence for violations of inherited property by non siblings. PSI X 1102 (3rd c. AD) preserves an important dispute about property rights between two children and three men who have stolen the property of the children’s father who died intestate. Furthermore, in P.Oxy.VII 1067 (3rd c. AD) Helen blaims her brother Petechon for neglecting the burial of their third brother and as a result a non-sibling woman inherited him. The purpose of the proposed paper is to discuss the various cases of conflicts over an inheritance between siblings and non-siblings. My interest will focus on the arguments and legal grounds used by the defendants in each case discussed with special attention paid to the differences between property claimed coming from intestate succession and testamentary disposition. By studying the various petitions to the judges, private letters or settlements and lawsuit proceedings I aim to investigate the legal and social ways in which people in Roman Egypt could protect their parental inheritance both from persons inside and outside the family.

Dominador N Marcaida Jr.