Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 13 July 2023

Integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria: their impacts on corporate sustainability performance

- Anrafel de Souza Barbosa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3178-4149 1 ,

- Maria Cristina Basilio Crispim da Silva 1 ,

- Luiz Bueno da Silva 1 ,

- Sandra Naomi Morioka 1 &

- Vinícius Fernandes de Souza 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 410 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

14 Citations

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Development studies

- Environmental studies

In a corporate sustainability context, scholars have been studying internal and external relations provided by Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, mostly from the organizational perspective. Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to map and analyze the literature on the impacts of integrating ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance from different points of view. The methodology used followed the Preferred Report Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, corroborated by a critical analysis. The results indicate that the integration of ESG criteria, observed from different perspectives, strengthens corporate sustainability performance. They also revealed narrowing gaps in the literature regarding methodological analysis. Most of the papers in the analyzed sample use company-level data and employ regression analysis in their analysis. The present study concludes that companies, regardless of nationality, follow the guidelines of ESG criteria integration and such procedure brings several benefits. It points to the lack of more confirmatory research approaches from a workers’ perspective, as the interest remains in the economic-environmental realm from the organizations’ point of view. The absence of such evidence points to a gap in the literature that suggests the need for new study initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Toward a new understanding of environmental and financial performance through corporate social responsibility, green innovation, and sustainable development

Muddassar Sarfraz, Ilhan Ozturk, … Heesup Han

Who’s in and who’s out? Reading stakeholders and priority issues from sustainability reports in Turkey

Sibel Hoştut, Seçil Deren van het Hof, … Gülten Adalı

Assessments of the environmental performance of global companies need to account for company size

Rossana Mastrandrea, Rob ter Burg, … Franco Ruzzenenti

Introduction

The discussion surrounding the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria and corporate sustainability has gained significant momentum in recent years, primarily driven by the evolving societal expectations regarding new models of production and consumption (Nishitani et al., 2021 ). Until the mid-1990s, according to Clarkson ( 1995 ), the focus of companies’ success was primarily centered on satisfying the needs of a single stakeholder, namely the shareholder. However, as time passed and the panorama shifted, particularly influenced by public policy changes, this perspective has undergone transformations. Gradually, other stakeholders have exerted pressure on companies, resulting in the integration of corporate sustainability into the strategic management of organizations, leading them to practice the ESG criteria (Wang et al., 2018 ).

Corporate sustainability performance refers to a company’s ability to operate in a manner that upholds ecological integrity, social well-being, and sound governance principles, while simultaneously generating value for its shareholders (Ahmad et al., 2023 ; Luque-Vílchez et al., 2023 ). It encompasses the effective management of environmental resources, fostering positive social relationships, and maintaining high standards of ethical conduct (Bellandi, 2023 ). The assessment of corporate sustainability performance requires the evaluation of both qualitative and quantitative indicators, examining various dimensions such as environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and corporate governance (Sandberg et al., 2022 ).

ESG criteria are used to assess corporate sustainability and ethical performance of companies and investments (Arora and Sharma, 2022 ). They are adopted by corporations to monitor and control the impacts of business activities on internal and external environments (Viranda et al., 2020 ). They mainly include: (i) collecting information; (ii) developing solutions; (iii) dealing with ESG issues in compliance with standards; (iv) conducting training; and (v) providing good communication (Boiral, 2002 ; Montabon et al., 2007 ; Merli and Preziosi, 2018 ). ESG criteria include prevention and preservation performance indicators (Gond et al., 2012 ). Besides, it requires coordination between the environmental department and other departments within companies, and balance between sustainable development goals and other corporate goals.

ESG criteria incorporates environmental, social, and governance factors into investment and business decision-making processes, and involves conditions relevant to traditional financial metrics when analyzing investments or valuing companies (Madden, 2022 ). These conditions can include metrics such as carbon emissions, water usage, employee diversity, labor practices, board diversity, executive compensation, etc. Thus, ESG criteria provide quantitative and qualitative information about a company’s sustainability practices and their potential impact on various stakeholders (Khalil et al., 2022 ; Uyar et al., 2023 ).

ESG integration involves incorporating environmental, social and governance indicators into investment and business decision-making processes. Instead of considering ESG criteria as separate from financial analysis, integration recognizes their materiality and incorporates them alongside traditional financial analysis. This integration can happen at various stages of the investment process, including portfolio construction, risk assessment, due diligence, and ongoing monitoring. Integration aims to identify and manage risks and opportunities related to ESG criteria, ultimately seeking to enhance long-term investment performance and sustainability (Gebhardt et al., 2022 ; Harasheh and Provasi, 2023 ).

ESG criteria provide the data and metrics to assess a company’s sustainability and ethical performance, while the integration involves incorporating these criteria into investment and business decision-making processes to better understand and manage the potential impacts on financial performance and corporate sustainability (Alda, 2021 ; Sahoo and Kumar, 2022 ).

In this sense, the integration of the ESG criteria has become an instrument responsible for defining, planning, operationalizing and executing the actions of corporations directed at environmental prevention and preservation, in addition to social responsibility and the quality performance of their activities (Barbosa et al., 2021 ).

Both from the standpoint of Sustainable Development Goals and the company response to shifting consumer preferences, interest in corporate sustainability has been increasing importance (Boulhaga et al., 2022 ). When looking for the relationship between the implementation of the ESG criteria and the corporate sustainability, the literature presents a heterogeneous scenario. Some researchers advocate a positive relationship (Harymawan et al., 2022 ; Kim et al., 2022 ), and others have confirmed a negative relationship (Rajesh and Rajendran, 2020 ).

As is the case with research by Lee and Isa ( 2022 ), they find a positive relationship between the implementation of ESG criteria and financial performance, suggesting that ESG criteria can increase company value. In addition, the authors also find evidence that the disclosure of ESG criteria can improve the relationship with corporate sustainability performance. Already in the study by Xu et al. ( 2022 ), the heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the negative relationship between ESG disclosure and the risk of falling stock prices is more significant in state-owned companies, companies with higher agency costs and in companies in the development phase.

Although the results are ambiguous, there are several positive examples of the relationship between the ESG criteria and the corporate sustainability, which influences the reasons why research on sustainable business models has been carried out and why organizations are changing their business model in the direction of sustainability. Additionally, there is a lot of pressure to consider ESG factors when making decisions, particularly from capital investors and financial institutions (Jonsdottir et al., 2022 ; Park and Oh, 2022 ).

Organizations responding to the pressure to implement ESG criteria must manage environmental, social, and economic risks (Triple Bottom Line) and understand their short, medium, and long-term impacts (Bravi et al., 2020 ). To this end, many companies adopt management systems related to ESG criteria to integrate elements of the Triple Bottom Line, address stakeholder needs, and mitigate risks (Esquer-Peralta et al., 2008 ).

Thus, the ESG criteria cannot be seen only as a cost, since they can bring benefits to the company and be a competitive advantage over competitors (Barbosa et al., 2023 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ).

That said, the need for an innovative and coherent research field focused on ESG issues increases as environmental, social, and governance problems intensifies (Vanderley, 2020 ).

The literature has already discussed the research situation, qualitatively and quantitatively, regarding ESG criteria through the prism of corporations, usually in the context of trying to improve the field’s problem-solving ability in relation to companies’ concerns and practices. Baumgartner and Rauter’s ( 2017 ) research addresses the strategic perspectives of corporate sustainability management to develop sustainable organizations and promote the integration of ESG criteria into business activities and techniques.

This narrow interpretation is criticized by several scholars as being insufficiently analytical, as well as lacking a rigorous appreciation of the historical basis of human-environment interaction, highlighting worker perception (Bryant and Wilson, 1998 ; Herghiligiu et al., 2019 ).

Existing research on ESG criteria primarily focuses on the corporate perspective (Bourcet, 2020 ; Khanchel et al., 2023 ; Tsang et al., 2023 ). However, this literature review did not identify any references that support the worker’s perspective or address their involvement in organizational management, as highlighted by Ouni et al. ( 2020 ).

Therefore, this study aims to map and analyze the literature on the impacts of integrating ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance through different points of view. The research will employ both qualitative and quantitative analysis and consider the viewpoints of both employers and employees. This study aims to fill the existing gap in the literature, as no significant research has yet converged in this direction.

As is the case with the research of Huang ( 2021 ), who conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to examine the link between ESG activities and organizational financial performance, focusing on the institutional aspect. Similarly, Taliento et al. ( 2019 ), who investigated the impact of ESG factors on economic performance, emphasizing the corporate sustainability advantage and business understanding.

This research holds significance due to the growing global efforts to establish ESG criteria and mitigate environmental, social, and economic risks (Triple Bottom Line) for sustainable development. It aims to comprehend how these risks can affect sustainable development in the short, medium, and long-term, considering both organizational and collaborative perspectives (workers) (Bravi et al., 2020 ).

In this sense, the main objective of this paper is to map and analyze the literature on the impacts of integrating ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance through different points of view. To achieve the proposed objective, the investigation addressed the following research questions:

What are the main features of the literature on ESG criteria?

What are the main methodological approaches used to study ESG criteria impact on corporate sustainability?

What are the main impacts of integrating ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance observed in the literature?

This paper is divided into six sections, including this introduction (section 1). Section “Theoretical backgrounds: Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria” refers to the theoretical foundation on the ESG criteria and the construction of the research hypotheses. Subsequently, in section “Methodological procedures”, the methodological procedures of the research are discussed. In section “Results”, the results are developed. Then, in section “Discussion”, a discussion is carried out. And, finally, in section “Conclusion”, the research conclusions are highlighted.

Theoretical backgrounds: Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria

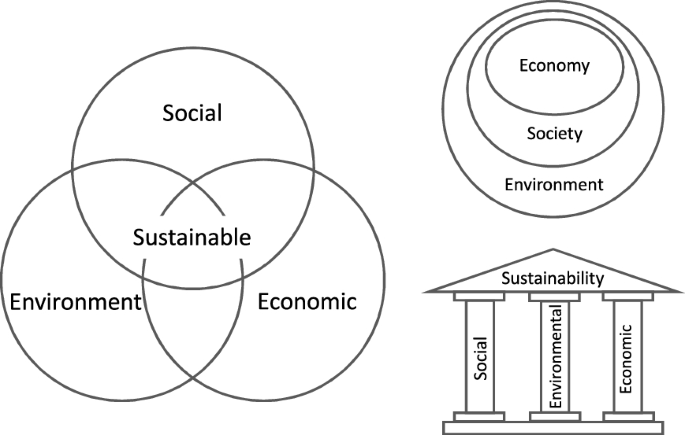

The ESG criteria are about the set of organizational practices that considers in its context environmental, social, and governance factors, with a view to achieving long-term sustainability (Sultana et al., 2018 ). The proportionality of these three aspects in business management has the purpose of analyzing the operations in a holistic way, not limited merely to the economic and financial aspects (Cek and Eyupoglu, 2020 ). In this sense, the economic, transparency and ethical precepts are articulated, seeking to ensure the competitiveness and the perdurability of a company. (Oncioiu et al., 2020 ).

The environmental dimension involves assessing the corporation’s carbon footprint, natural resource usage (energy consumption and efficiency), recycling policies, waste management, and efforts to minimize environmental impacts (Rajesh, 2020 ). The social dimension encompasses the company’s relationships with employees, suppliers, partners, clients, and communities. It includes promoting diversity, non-discrimination, gender pay equality, equal opportunities, employee education, and community protection (Li and Wu, 2020 ). The governance dimension focuses on leadership, internal controls, executive compensation, audits, shareholder rights, anti-corruption policies, and transparency and accountability practices (Cek and Eyupoglu, 2020 ).

ESG criteria, also known as sustainable or socially responsible investments, assist investors in assessing companies’ initiatives and commitment to environmental, social, and governance issues. These criteria can be applied internally or externally in a company’s management (Du Rietz, 2018 ).

That said, compliance with ESG policies and practices is increasingly important to investors, employees, and customers, shaping company perception and performance evaluation beyond financial measures (Beretta et al., 2019 ).

While ESG indicators may vary by region, market, and industry, there are emerging best practices in the corporate world (Khalid et al., 2021 ). Thus, an example of ESG practices can be observed through the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), created by initiative of investors in partnership with the United Nations Environment Program Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) and the UN Global Compact, with the aim of guiding the market in the pursuit of responsible development (Bauckloh et al., 2021 ; Naffa and Fain, 2020 ).

Therefore, one way to find out whether a particular organization is sustainable is to evaluate its performance by ESG indexes. However, these indexes have limitations as they may not capture the multidimensional aspects of ESG criteria comprehensively. Consequently, a broader focus on ESG criteria is needed, considering corporate sustainability performance.

Methodological procedures

There are distinct alternatives that can be appreciated in the deployment of a SLR, comprising a bibliometric approach, meta-analysis (Hunter et al., 1986 ) and content analysis approaches. (White and McCain, 1998 ). These three techniques were applied in the present study. The scope of this study provides qualitative and quantitative analysis of publications, in the synthesis and assimilation of the most explored academic research and authors with the support of citation analysis, as well as in the critical analysis of the sample of articles collected.

To address the research aims, which is to map and analyze the literature on the impacts on corporate sustainability performance provided by the integration of ESG criteria, this study relied on two procedures. The first procedure was a consistent and robust SLR materialized according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) methodology, which blends reference analysis, network analysis, and content analysis. The second method was a critical in-depth analysis of a specific sample of articles collected through the PRISMA structured procedure, which integrated and supported the initial technique, as already used in the sustainability literature (Bolis et al., 2014 ).

Primary procedure: PRISMA methodology

The PRISMA methodology is a directive that aims to provide scholars to improve the peculiarity of the externalization of research information, as well as to guide in the critical conjecture of a review of articles already published (Page et al., 2021 ).

Eligibility and ineligibility criteria

The documents eligible for the sample of this research were those published in the last 5 years (period from 2017 to March 2022); belonging to the study domain of environmental, social and governance areas (research area); considered exclusively as research articles (document type); disseminated only in scientific journals (journals ); written only in English language (language); and intrinsic to the topic of this research. The ineligible studies were those without a well-defined scientific structure, those without relevant data implicated in the theme of this research, those without access to the text ( in press ), and those that did not propose quantitative analysis (as this is a relevant point for future research).

Selection of the scientific databases

As a basis for this SLR and starting to answer the questions listed to achieve the objective of this study, the initial sample of articles followed systematic strategies that were adopted to consult the bibliometric databases until March 2022. Three scientific knowledge bases, Scopus , Web of Science ( WoS ), and Science Direct ( SD ) were used in to identify studies related to the ESG criteria.

The level of quality, the number of publications, the area of knowledge, and the set of metadata essential for the analysis of the references (including titles, abstracts, keywords, year of publication, number of citations, list of authors, countries, among others) were the criteria of choice for these 3 scientific databases. Scopus is one of the largest scientific knowledge bases of peer-reviewed literature (Morioka and de Carvalho, 2016 ). WoS can cover all indexed journals with an impact factor calculated in JCR ( Journal Citation Report ) (Carvalho et al., 2013 ). And SD combines reliable full-text publications in the scientific, technical and health fields (Direct, 2020 ). Another factor also considered was that all 3 databases provide metadata compatible with Mendeley reference analysis software (Carvalho et al., 2013 ).

Sampling procedure

The sampling procedure used to screen the articles was search by search terms, which were adapted for each defined bibliographic database. This was performed in March 2022. The keyword terms for the investigation were applied as follows: ("Environmental, Social, and Governance") AND (Impact* OR Effect* OR Performanc* OR Integrat*) AND (Sustainab*).

The initial searches are shown in Table 1 .

The first triage was applied as " Article title, Abstract, Keywords " in Scopus , as " Topic " in WoS and as " Title, abstract or author-specified keywords " in SD resulting in 5,760 collected documents ("Initial Sample"). Then, the primary parameter for refining the references was run as " Publication Years ", reducing the number of records by 1,152 documents. The secondary elimination criterion was applied as " Topic Area ", synthesizing the sample into 580 searches.

Continuing with the exclusion process, the third suppression factor was submitted as " Document Type ", summarizing the records into 486 studies. Subsequently, "Source Type" was used as the fourth parameter of reference reduction, reducing the records by 3 documents. Subsequently, the penultimate refinement requirement was performed as " Language ", subtracting 9 more references. Finally, the reading of the titles and abstracts of the articles was used as the sixth ground for the refinement of the sample as " Off Topic ", restricting to 3,172 documents that did not directly address the topic of this study. Thus, the quantity of rejected documents was 5,402 references, resulting in a sample of 358 research articles selected from the 3 scientific databases.

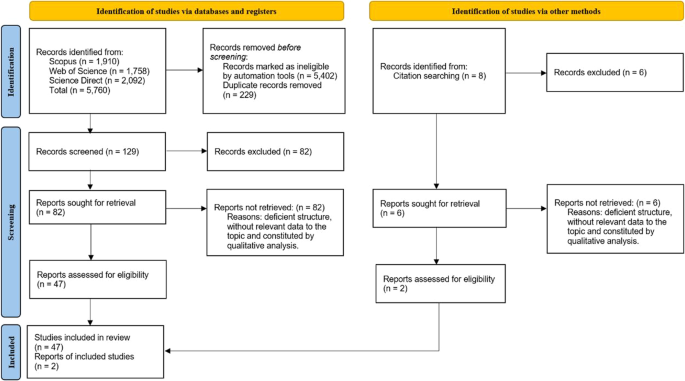

The references were then entered into Mendeley software to verify the intersections of studies between the databases. The triage identified 229 duplicate documents, which were excluded, reducing the sample to 129 articles. Subsequently, an isolated analysis of each of the 129 selected publications was performed to assess compatibility with the eligibility and ineligibility criteria focusing on the adequacy to the research premises and quality parameters related to the methodological peculiarity of the publications. This analysis resulted in an exclusion of 82 studies. The "Remaining Sample" became 47 research articles.

After rejecting studies that did not satisfy the "Initial Sample" pre-selection process, that were in duplicate, and that did not have the eligibility criteria, the snowball method was applied (Yin et al., 2020 ). The references were expanded to incorporate other studies that were cited in the 47 articles in the "Remaining Sample". The total number of records selected through the snowball technique was 2 studies ("Additional Sample"). The inclusion of the additional articles followed the same eligibility (except for the year of publication) and ineligibility criteria cited in section “Eligibility and ineligibility criteria”. Thus, the "Final Sample" for the conduct of this SLR was 49 research articles.

Reference analysis

Data tabulation and grouping strategies directed the stratification of information and a narrative synopsis. A spreadsheet ( Microsoft Excel 2021) and Mendeley software were used to manage the selected articles to transcribe predominant methodological minutiae of each research study comprising the assessment instrument used, the setting, participants, and substantive findings in terms of validity and credibility. The number of publications summarized by year and journal was the initial parameter of the reference analysis process. This resource made it possible to see how the records succeeded over the years and to discriminate the journals that repeatedly dealt with the theme of this research.

Network analysis

In this step, with the assistance of the VOSviewer software , the network analysis was performed, considering the compatibility of keywords and authors were analyzed through clustering diagrams. The first citation network developed was that of most relevant keywords. The second network developed was that of co-citations, which shows the degree of equivalence between the references presenting the articles mentioned together. The analysis of this network can help assimilate the intellectual character of a field and map the thematic similarities of scholars and the aspect of how groups of researchers relate to each other (Pilkington and Liston-Heyes, 1999 ).

Another analysis performed was on the methodological approaches applied among the studies. For this diagnosis, a deductive multivariate approach was applied based on the theoretical foundation and knowledge from the references. This analysis used insights extracted from the keywords and the analysis of important topics.

Content analysis

Each article included in the final sample was specifically cataloged using Mendeley software that comprised the metadata generated by scientific databases. For the content analysis, the articles were classified in order to consider the tools applied, the scope of application, the relevant industries, the research objectives, and the advantages and limitations of the process required to obtain the research results.

Secondary procedure: critical (interpretative) analysis

Critical analysis is a research skill outlined to contribute to the interpretation of complex issues to understand specific conjunctures (Gil-Guirado et al., 2021 ). Critical analysis involves multiple iterative cycles of interpreting and perceiving the content of parts of the phenomena of interest, and this assimilation of the parts entails a better understanding of the contexts as a whole (Valor et al., 2018 ).

To deepen the assimilation of the contexts, each researcher involved forms an understanding of their perspective in continuous cycles until a "cognitive fusion" is achieved resulting in a better conception of the phenomena. This approach does not aim to construct a theory, but rather to infer a better understanding of the contexts (Bolis et al., 2014 ). Thus, to complement the answers to the questions of this research, critical analysis was applied, which involved dialectical reasoning cycles to identify the understanding (systematization of applicable processes to determine the meaning and scope of methodologies) of researchers on the impacts of integrating ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance with the aim of finding the "cognitive fusion".

The initial cycle demanded a series of reviews, syntheses, and interpretations of the sample of articles collected in the structured procedure (PRISMA). In the next cycle, the collaborative critical process was adhered to, resulting in the refinement of the main methodological characteristics fragmented by each ESG criterion. Later, in the final interpretive cycle, the procedures of the first two cycles were analyzed, which provided additional perspectives and insights that complemented the previous interpretations.

Risk of bias

To assess the methodological quality of the included articles, the Prediction Study Trend Risk Assessment Tool (PROBAST) was used. (Wolff et al., 2019 ). This tool includes 20 questions divided into four domains (participants, predictors, outcome, and analysis). The risk of bias for each domain was rated as low risk, high risk, or very unclear to judgment (Wolff et al., 2019 ). Two researchers of the present study independently assessed the risk of bias of the included articles and performed an evaluation by qualitative analysis. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer.

The document collection strategy yielded 129 records, and after screening titles and abstracts and applying eligibility and ineligibility criteria, 49 articles were selected for this systematic literature review (SLR). Please refer to Fig. 1 for the SLR flow diagram.

Source: Adapted from Page et al. ( 2021 ).

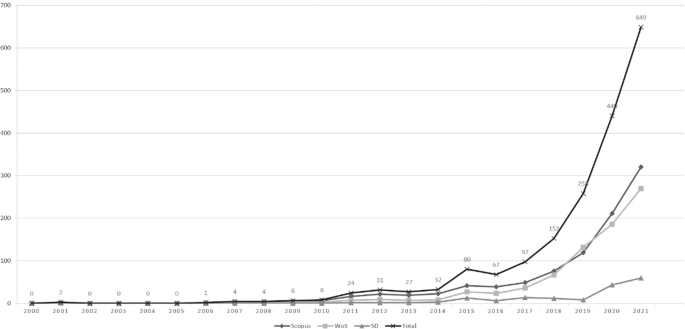

Consistent with Nishitani et al.’s ( 2021 ) assertion, Fig. 2 demonstrates the contemporary nature of discussions on ESG criteria and corporate sustainability, indicating their recent consolidation. In this specific context, the eligibility and ineligibility criteria of the articles were disregarded, and only a keyword search for "Environmental, Social, and Governance" was conducted across three databases. This was solely done to quantify the research related to the theme.

Source: Scopus , WoS , and SD .

It is evident that there has been an increasing number of studies focused on ESG criteria over the years, with a peak of 649 research articles in 2021 (an average of 54 articles per month). This trend aligns with the growing interest of organizations in implementing ESG criteria (Qureshi et al., 2021 ).

Literature overview

Starting to answer the first research question ( What are the main characteristics of the literature on ESG criteria? ), an overview of the literature was conducted based on descriptive statistics of the sample of 49 selected articles. Table 2 presents the most influential studies. It lists the publications with 20 or more citations in the Scopus database.

The study that stood out the most was that of Xie et al. ( 2019 ), which investigates whether environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance, with 115 citations over 3 years, an average of 38 citations/year; followed by the respective research of Garcia et al. ( 2017 ), which highlights the sensitive emerging market sectors in relation to improved ESG performance, published in the year 2017 and has 104 citations; and by Qureshi et al. ( 2020 ), which analyzes the moderating role of the impact of sustainability disclosure and board diversity on firm value, with 41 citations in 2 year, both averaging approximately 21 citations per year.

The articles of the core sample were designated from the network analysis of keywords, a quantitative technique practiced to identify the repercussion and expressiveness of an author or an article (Garfield and Morman, 1981 ). Nevertheless, this methodology should also take into account the relevance of the journal, besides computing the average annual citation (Carvalho et al., 2013 ), as shown in Table 2 .

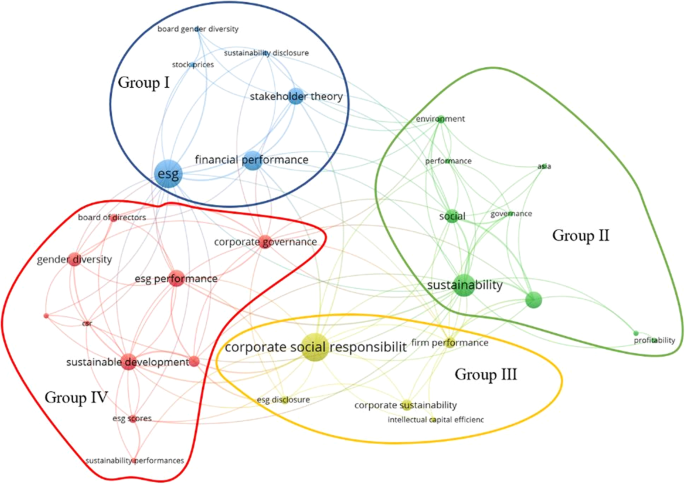

That said, Fig. 3 shows, through the network analysis of the VOSviewer software , the relationship between the keywords and the articles in the designated sample, with recurrences of at least 2 times (this implies that terms that appear only once were not displayed). Other points to be observed are that the more consistent (full-bodied) the meshes the stronger the connections and the larger the points (nodes) of connections the more relevance they have.

Source: Scopus, WoS , and SD .

Network analysis enables a better explanation of the consonance between the terms discovered, as well as simplifying the differentiation between the groupings literally associated with its operating principles.

There were 4 sets of keywords identified. Of the 4 sets of the keyword network analysis, 3 contain the term " ESG " and its variations. In the case of the terms " sustainability and performance ", all 4 clusters register their presence. This demonstrates that the search terms adopted were assertive, since it can be seen that they adhere to the proposed theme.

The research by Zhang et al. ( 2020 ), which discusses how ESG initiatives affect innovation performance for corporate sustainability; and the research of Xu et al. ( 2021 ), which examines the impacts of research and development (R&D) investment and ESG performance on green innovation performance; ratify the cited adherence.

Research topics: the main methodologies

The predominant impacts addressed in the sample of 49 scientific studies collected, classified by level of analysis and methodological interpellation, are evidenced in Table 3 , which already awakens the dissolution to the second research question ( What are the main methodological approaches used to study ESG criteria impact on corporate sustainability? ).

A content analysis of the full texts of the articles selected for this SLR was performed and it was found that approximately 87.75% of the studies (43 references) were conducted using information from companies through databases. Analyzes were quantitative, 46 studies, approximately 93.87%, applied regression analysis. Of these, 6 investigations, approximately 13.04%, implemented structural equation modeling. These results, corroborate the conjuncture that there is no evidence in the literature regarding research allusive to a mapping and quantitative analysis of the impacts of the integration of ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance, from an employee’s perspective.

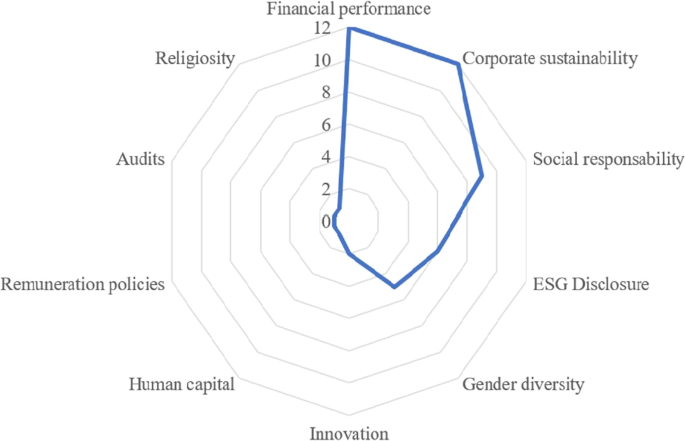

By Fig. 4 , it can be distinguished that the organizations’ commitment does not focus exclusively on financial performance (12 studies), but also prioritizes corporate sustainability (12 studies).

Financial performance and corporate sustainability were investigated in approximately 49% of the research (24 records), proving corporate concern for both sustainable development and economic performance. Landi et al. ( 2022 ), highlight this awareness in their investigation of the incorporation of sustainability into risk management and the impacts on financial performance. Taken together, these practices have the potential to minimize cost and risk, enhance the company’s reputation and legitimacy, intensify innovation, and solidify growth paths and trajectories, all of which are vitally important to stakeholder value creation. (Ting et al., 2020 ).

The corporate sustainability performance disclosed through the ESG criteria was investigated in an attempt to demonstrate the quality of an organization, because through environmental, social, and governance analysis, it is possible to determine how the company positions itself in relation to society and the planet, in addition to offering more transparency to the investor (Mohammad and Wasiuzzaman, 2021 ).

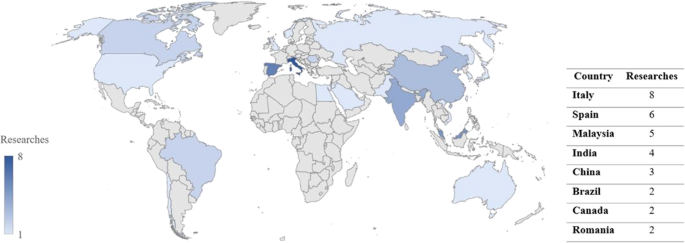

Figure 5 displays a broad view of the amount of research performed around the world according to the sample of articles selected for this SLR.

It can be seen that Europe stands out in the evolution of ESG criteria with approximately 32.65% of research, with the highest visibility for Italy and Spain. The research by Conca et al. ( 2021 ), on the impacts of ESG reports in European agri-food companies; and (Baraibar-Diez and Odriozola, 2019 ), related to the effects of ESG parameters on the social responsibility committees of European corporations, highlight the aforementioned evolutionary prominence.

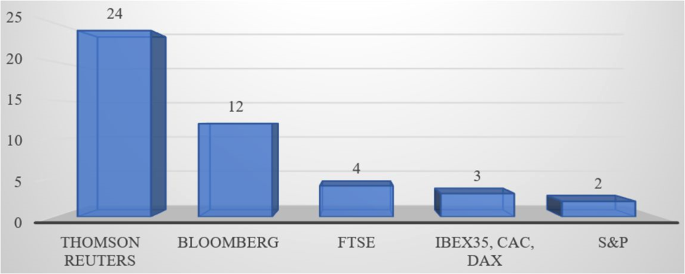

Figure 6 displays the most often consulted databases to collect information about the ESG criteria of the listed companies for their corporate sustainability performance.

Source: Table 3 .

Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg databases stand out because they are providers of reliable answers that help organizations make confident decisions and better manage business (Alsayegh et al., 2020 ). This reinforces the fact that most studies use publicly available data to measure ESG, whether than collect the ESG criteria for the companies under investigation.

Critical analysis

Critical analysis is a method of study for understanding difficult and complex situations, especially when interpretations of the same articulation are possible and competing. It is a form of text analysis and has been handled to discover their original meanings and how they are interpreted (Shephard et al., 2019 ).

Thus, complementing the results of the primary approach (PRISMA method), a critical analysis was implemented based on the selection of 49 articles considered for discussion. The aim was to answer the third question of this research ( What are the main impacts of integrating ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance observed in the literature? ). Table 4 shows the main perceptions of the fragmented research according to each of the ESG criteria.

The cycles of the critical analysis involved a series of reviews, syntheses, and interpretations of ESG criteria affecting corporate sustainability performance identified in the 49 selected articles corroborating the structured process of this SLR. The results are shown in Tables 3 and 4 , which summarize the focus of the research, the methodologies applied, and the main gaps, contributions, and limitations of the studies.

In this SLR, the need for future empirical studies was also identified. There are still several research questions that need to be answered in depth. Some propositions for future investigations and possible research questions are outlined in Table 5 .

Analyzing the risk of bias in scientific research is of paramount importance as it can significantly impact the validity and reliability of research findings. It helps ensure that research outcomes accurately reflect reality and can be trusted by other researchers, policymakers, and the public (McGuinness and Higgins, 2021 ). Reproducibility is a fundamental principle of scientific research and transparently analyzing bias allows researchers to identify potential pitfalls and enhance the reproducibility of their work. Ethical considerations are also important as biased research can lead to harm, perpetuate discrimination, or favor specific individuals or groups unjustly (Marshall et al., 2015 ). Analyzing bias helps to improve the quality of evidence available for decision-making processes and ensures that the scientific literature remains reliable, allowing researchers to build upon a solid foundation of unbiased evidence. By carefully evaluating and addressing bias, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their work (Reveiz et al., 2015 ; Wang et al., 2022 ).

In accordance with Table 6 (PROBAST diagnostics), most (93.9%) of the included research evidenced a minimal risk of bias and a low concern for applicability. The participants were the companies selected in each study; the predictors were the variables measured; the results were verified by the mathematical models; and the analysis, encompass the techniques used. The quality of the studies included in this study was rated from satisfactory to excellent.

Drawing upon rigorous research, this paper elucidates the prominent features that have appeared from the examination of ESG criteria. Table 2 and Fig. 3 show the repercussion, expressiveness and relevance of studies, authors, and journals.

The content analysis highlighted in Table 3 found that the literature on ESG criteria were carried out with information from companies through databases and applied regression analysis. These findings support the idea that there is no evidence in the study literature that maps or quantifies the effects of incorporating ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance from the viewpoint of employees.

Ouni et al. ( 2020 ), in their study on the mediating role of ESG strands in relation to executive board gender diversity and corporate financial performance, highlighted the need for future research that focuses not only on organizational understanding, but especially on the perception of women (workers) themselves, as board members, of their role and their contribution to financial performance, which strengthens the gap characterized in this SLR.

Researchers employ various methodologies to study ESG criteria, allowing for nuanced insights and robust analysis (see Table 3 ). Quantitative studies utilize large-scale data sets, statistical models, and financial indicators to explore the relationship between ESG criteria and financial performance, risk management, and firm valuation (Alkaraan et al., 2022 ; Mavlutova et al., 2022 ). Qualitative research methods employ interviews, case studies, and content analysis to investigate the organizational processes, stakeholder perceptions, and contextual factors that influence ESG practices and outcomes (Petavratzi et al., 2022 ). Some studies adopt an integrated approach by combining quantitative and qualitative methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of ESG criteria. These integrated approaches contribute to a holistic understanding of ESG-related phenomena (Aldowaish et al., 2022 ; Rehman et al., 2021 ).

Recognizing the strengths and limitations of methodologies, researchers have increasingly adopted mixed-methods approaches to investigate the impact of ESG criteria on corporate sustainability, integrating data collection and analysis processes to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research problem (Gebhardt et al., 2022 ). This approach allows researchers to triangulate findings, validate results, and gain a more nuanced perspective on the relationship between ESG criteria and corporate sustainability (Harasheh and Provasi, 2023 ). By leveraging the strengths of methodologies, research offers a more holistic and robust approach to studying complex phenomena.

The positive relationship of voluntary disclosure of corporate sustainability through the ESG criteria of organizations found in this study (see Table 4 ) provides evidence that the implementation of environmental and social strategies within an efficient system of corporate governance in the company strengthens the performance of corporate sustainability. The results also show that environmental performance and social performance are significantly positively related to sustainable economic performance, indicating that the corporation’s economic value and the creation of value for society are interdependent.

A similar fact was also found in the investigation of Zhang et al. ( 2020 ), on environmental, social and governance initiatives that affect innovative performance for corporate sustainability, which revealed that corporate governance initiatives play a moderating role in the relationship between environmental initiatives and performance innovation and the relationship between social initiatives and innovative performance.

Shaikh ( 2021 ), in his study on ESG practices and solid performance, explains the importance of voluntary reporting of non-financial indicators and a company’s responsibility towards stakeholders, reflected in the corporation’s accounting performance.

Integrating ESG criteria into business practices can have potential negative impacts, although specific effects may vary depending on context and implementation. As shown by the investigations of Wasiuzzaman et al. ( 2022 ), which verifies the extent to which culture can affect the relationship between ESG disclosure and company performance, evidencing the negative impact on the profitability of energy companies; and of Suttipun and Yordudom ( 2022 ), which analyzes the extent, level and trend of ESG disclosure in companies in Thailand, to test the different levels between high and low profile industries, which found a negative impact of governance disclosure on market reaction . Another example is the research of Yu et al. ( 2020 ), about Greenwashing in ESG disclosures, which identified organizations’ manipulations of ESG disclosures to increase market value.

While these concerns exist, effectively integrating ESG criteria can drive long-term value creation, risk management and stakeholder confidence. Implementing robust ESG practices requires careful consideration, transparency, and ongoing evaluation to mitigate potential negative impacts and ensure sustainable results.

The main objective of this article is to map and analyze the literature concerning the impacts of the integration of ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance. To this end, an SLR was performed using the PRISMA methodology, with the intention of selecting the most relevant articles.

Figure 2 revealed an increase in the number of publications on ESG criteria. In 2017, there were only 97 published papers. Already in 2021, this number expanded to 649 manuscripts, an evolution of approximately 570%.

The references were systematically appraised using a hybrid approach that combined literature review methodologies, including structured and objective techniques such as bibliometric analysis, network analysis, and content analysis, to identify key highlights and gaps in the literature related to the theme of this investigation; as well as subjective text interpretation technique (critical analysis), to robust the structured analysis.

This study assisted in diagnosing the methodologies addressed and narrowing the gaps in the literature in four ways. Initially, the article presents a bibliometric analysis with a perspective on ESG criteria and sustainability performance based on the sampling of 49 research studies outlining the main papers and journals (according to Table 2 ). Subsequently, with the aid of network analysis the main keywords were highlighted (see Fig. 3 ).

Next, based on an in-depth content analysis, the article presents the main study highlights, the focus of the research, and the stratification of methods (Table 3 ). Finally, the critical analysis is juxtaposed to consolidate the initial structured analysis (Table 4 ).

Several authors have discussed the topic addressed by this SLR, such as Lokuwaduge and Heenetigala ( 2017 ), who made an interpellation of the integration of ESG precepts for an organizational sustainable development. Another reference is the paper by Bouslah et al. ( 2013 ), which analyzed the ESG dimensions and corporate risks.

But there is no evidence, to the knowledge of the authors of this paper, in the sample selected for this SLR, of research on a mapping and quantitative analysis of the impacts of integrating of ESG criteria on corporate sustainability performance as a result of workers’ perceptions. The study points out the lack of more confirmatory research approaches applying a multidimensional perspective of workers, as the interest remains in the economic-environmental perspective from the organizations’ point of view. It was also found that none of the studies listed made use of other types of diagnostic instruments diverging from the databases.

That said, the absence of such evidence highlights a gap in the literature that suggests the need for new study initiatives to fill it.

In addition to the opportunities for future studies proposed in Table 5 , future researches could explore the developing standardized metrics, common metrics that are relevant across different sectors and geographies; the relationship between ESG and financial performance, mechanisms behind this relationship, such as the impacts of ESG criteria on customer loyalty or employee satisfaction; the impacts of ESG criteria on non-financial stakeholders, such as employees, customers, and communities; the role of technology in ESG, such as artificial intelligence and blockchain in ESG reporting and decision-making; and on emerging ESG issues, such as the impact of climate change on supply chains or the ethical considerations of artificial intelligence.

Therefore, it would be important to establish standards and parameters that allow companies to understand and evaluate ESG criteria. In this sense, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) could develop a global standardization on ESG that defines parameters, guidelines, and criteria with quality indicators, in line with the ISO 9001 standard already recognized worldwide.

This exploratory work highlights as a contribution the aspect of guiding corporations in understanding how the integration of ESG criteria can positively impact corporate sustainability performance, providing investment optimization and better business planning.

Furthermore, some important conclusions related to the ESG criteria can be obtained. It was observed that companies, regardless of nationality, follow the guidelines of ESG criteria integration and such procedure brings many benefits, such as: improving the organization’s image with stakeholders; increasing the corporation’s competitiveness; promoting corporate sustainability; improving the conjuncture in relation to gender diversity; improving intellectual opportunities; among others.

This research has limitations related to the use of keyword search engines and the filters of the selected databases. The keyword groups are asked to be elaborated in diverse ways, so the combinatorial analysis of the groupings may bring different answers. The filters of the scientific databases have disparate search characteristics, which may cause divergences in the answers. Another limitation was the critical analysis that may have generated an interpretation bias. Nevertheless, the PROBAST method and the systematic multi-method approach applied (bibliometric, network analysis, and content analysis) helped to mitigate this limitation.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analyzed.

Aboud A, Diab A (2019) The financial and market consequences of environmental, social and governance ratings: the implications of recent political volatility in Egypt. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 10:498–520. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-06-2018-0167

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad H, Yaqub M, Lee SH (2023) Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: a scientometric review of global trends. Environ Dev Sustain https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-02921-x

Alda M (2021) The environmental, social, and governance (ESG) dimension of firms in which social responsible investment (SRI) and conventional pension funds invest: The mainstream SRI and the ESG inclusion. J Clean Prod 298:126812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126812

Aldowaish A, Kokuryo J, Almazyad O, Goi HC (2022) Environmental, social, and governance integration into the business model: literature review and research agenda. Sustain. 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052959

Alkaraan F, Albitar K, Hussainey K, Venkatesh VG (2022) Corporate transformation toward Industry 4.0 and financial performance: the influence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG). Technol Forecast Soc Change 175:121423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121423

Alsayegh MF, Rahman RA, Homayoun S (2020) Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustain 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093910

Arayssi M, Jizi M, Tabaja HH (2020) The impact of board composition on the level of ESG disclosures in GCC countries. Sustain Account Manag Policy J 11:137–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-05-2018-0136

Arif M, Sajjad A, Farooq S, Abrar M, Joyo AS (2020) The impact of audit committee attributes on the quality and quantity of environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosures. Corp Gov 21:497–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-06-2020-0243

Arora A, Sharma D (2022) Do Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Performance Scores Reduce the Cost of Debt? Evidence from Indian firms. Australas Account Bus Financ J 16:4–18. https://doi.org/10.14453/aabfj.v16i5.02

Atan R, Alam MM, Said J, Zamri M (2018) The impacts of environmental, social, and governance factors on firm Performance: panel study of Malaysian companies. Manag Environ Qual An Int J https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-03-2017-0033

Baraibar-Diez E, Odriozola MD (2019) CSR committees and their effect on ESG performance in UK, France, Germany, and Spain. Sustain. 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185077

Baraibar-Diez E, Odriozola MD, Fernández Sánchez JL (2019) Sustainable compensation policies and its effect on environmental, social, and governance scores. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26:1457–1472. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1760

Barbosa A de S, Bueno da Silva L, de Souza VF, Morioka SN(2021) Integrated management systems: their organizational impacts Total Qual Manag Bus Excell 33:794–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2021.1893685

Barbosa A de S, Bueno da Silva L, Morioka SN, da Silva JMN, de Souza VF (2023). Integrated management systems and organizational performance: a multidimensional perspective. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2023.2181153

Bauckloh T, Schaltegger S, Utz S, Zeile S, Zwergel B (2021) Active first movers vs. late free-riders? An empirical analysis of UN PRI signatories’ commitment, J Bus Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04992-0

Baumgartner RJ, Rauter R (2017) Strategic perspectives of corporate sustainability management to develop a sustainable organization. J Clean Prod 140:81–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.146

Bellandi F (2023) Equilibrating financially sustainable growth and environmental, social, and governance sustainable growth. Eur Manag Rev 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12554

Beretta V, Demartini C, Trucco S (2019) Does environmental, social and governance performance influence intellectual capital disclosure tone in integrated reporting. ? J Intellect Cap 20:100–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-02-2018-0049

Birindelli G, Dell’Atti S, Iannuzzi AP, Savioli M (2018) Composition and activity of the board of directors: Impact on ESG performance in the banking system. Sustain 10:1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124699

Bodhanwala S, Bodhanwala R (2018) Does corporate sustainability impact firm profitability? Evidence from India. Manag Decis 56:1734–1747. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2017-0381

Boiral O (2002) Tacit knowledge and environmental management. Long Range Plann 35:291–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(02)00047-X

Bolis I, Morioka SN, Sznelwar LI (2014) When sustainable development risks losing its meaning. Delimiting the concept with a comprehensive literature review and a conceptual model. J Clean Prod 83:7–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.06.041

Boulhaga M, Bouri A, Elamer AA, Ibrahim BA (2022) Environmental, social and governance ratings and firm performance: the moderating role of internal control quality. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2343

Bourcet C (2020) Empirical determinants of renewable energy deployment: a systematic literature review. Energy Econ 85:104563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104563

Bouslah K, Kryzanowski L, M’Zali B (2013) The impact of the dimensions of social performance on firm risk. J Bank Financ 37:1258–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.12.004

Bravi L, Santos G, Pagano A, Murmura F (2020) Environmental management system according to ISO 14001:2015 as a driver to sustainable development. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27:2599–2614. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1985

Bravo F, Reguera-Alvarado N (2019) Sustainable development disclosure: environmental, social, and governance reporting and gender diversity in the audit committee. Bus Strateg Environ 28:418–429. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2258

Bryant RL, Wilson GA (1998) Rethinking environmental management. Prog Hum Geogr 22:321–343. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913298672031592

Carvalho MM, Fleury A, Lopes AP (2013) An overview of the literature on technology roadmapping (TRM): Contributions and trends. Technol Forecast Soc Change 80:1418–1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.11.008

Cek K, Eyupoglu S (2020) Does environmental, social and governance performance influence economic performance? J Bus Econ Manag 21:1165–1184. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2020.12725

Clarkson ME (1995) A Stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad Manag Rev 20:92–117. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9503271994

Conca L, Manta F, Morrone D, Toma P (2021) The impact of direct environmental, social, and governance reporting: empirical evidence in European-listed companies in the agri-food sector. Bus Strateg Environ 30:1080–1093. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2672

De Masi S, Słomka-Gołębiowska A, Becagli C, Paci A (2021) Toward sustainable corporate behavior: the effect of the critical mass of female directors on environmental, social, and governance disclosure. Bus Strateg Environ 30:1865–1878. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2721

Direct S (2020) Science direct advertisement. Clin Microbiol News 42:201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2020.12.002

Du Rietz S (2018) Information vs knowledge: corporate accountability in environmental, social, and governance issues. Account Audit Account J 31:586–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2013-1198

Esquer-Peralta J, Velazquez L, Munguia N (2008) Perceptions of core elements for sustainability management systems (SMS). Manag Decis 46:1027–1038. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740810890195

Gangi F, Daniele LM, Varrone N, Vicentini F, Coscia M (2021) Equity mutual funds’ interest in the environmental, social and governance policies of target firms: does gender diversity in management teams matter? Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 28:1018–1031. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2102

Garcia AS, Mendes-Da-Silva W, Orsato R (2017) Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: evidence from emerging markets. J Clean Prod 150:135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.180

Garcia AS, Orsato RJ (2020) Testing the institutional difference hypothesis: a study about environmental, social, governance, and financial performance. Bus Strateg Environ 29:3261–3272. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2570

Garfield E, Morman ET (1981) Citation indexing: its theory and application in science, technology, and humanities. Isis. https://doi.org/10.1086/352799

Gebhardt M, Thun TW, Seefloth M, Zülch H (2022) Managing sustainability—does the integration of environmental, social and governance key performance indicators in the internal management systems contribute to companies’ environmental, social and governance performance? Bus Strateg Environ 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3242

Gil-Guirado S, Cantos JO, Pérez-Morales A, Barriendos M (2021) The risk is in the detail: Historical cartography and a hermeneutic analysis of historical floods in the city of murcia. Geogr Res Lett 47:183–219. https://doi.org/10.18172/cig.4863

Gond JP, Grubnic S, Herzig C, Moon J (2012) Configuring management control systems: theorizing the integration of strategy and sustainability. Manag Account Res 23:205–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2012.06.003

Harasheh M, Provasi R (2023) A need for assurance: do internal control systems integrate environmental, social, and governance factors? Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 30:384–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2361

Harymawan I, Nasih M, Agustia D, Putra FKG, Djajadikerta HG (2022) Investment efficiency and environmental, social, and governance reporting: Perspective from corporate integration management. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 29:1186–1202. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2263

He R, Chen X, Chen C, Zhai J, Cui L (2021) Environmental, social, and governance incidents and bank loan contracts. Sustain 13:1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041885

Herghiligiu IV, Robu IB, Pislaru M, Vilcu A, Asandului AL, Avasilcai S, Balan C (2019) Sustainable environmental management system integration and business performance: a balance assessment approach using fuzzy logic. Sustain. 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195311

Huang DZX (2021) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: a review and consolidation. Account Financ 61:335–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12569

Hunter JE, Schmidt FL, Jackson GB (1986) Meta-analysis: cumulating research findings across studies. Educ Res 15:20–21. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015008020

Jonsdottir B, Sigurjonsson TO, Johannsdottir L, Wendt S (2022) Barriers to using ESG data for investment decisions. Sustain 14:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095157

Khalid F, Sun J, Huang G, Su CY (2021) Environmental, social and governance performance of chinese multinationals: a comparison of state-and non-state-owned enterprises. Sustain. 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074020

Khalil MA, Khalil R, Khalil MK (2022) Environmental, social and governance (ESG)—augmented investments in innovation and firms’ value: a fixed-effects panel regression of Asian economies. China Financ Rev Int https://doi.org/10.1108/CFRI-05-2022-0067

Khanchel I, Lassoued N, Baccar I (2023) Sustainability and firm performance: the role of environmental, social and governance disclosure and green innovation. Manag Decis https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-09-2021-1252

Kim J, Cho E, Okafor CE, Choi D (2022) Does environmental, social, and governance drive the sustainability of multinational corporation’s subsidiaries? Evidence from Korea. Front Psychol 13:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.899936

Koroleva E, Baggieri M, Nalwanga S (2020) Company performance: are environmental, social, and governance factors important? Int J Technol 11:1468–1477. https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v11i8.4527

Kuo TC, Chen HM, Meng HM (2021) Do corporate social responsibility practices improve financial performance? A case study of airline companies. J. Clean. Prod. 310:127380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127380

Landi GC, Iandolo F, Renzi A, Rey A (2022) Embedding sustainability in risk management: The impact of environmental, social, and governance ratings on corporate financial risk. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2256

Lee S-P, Isa M (2022) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices and financial performance of Shariah-compliant companies in Malaysia. J Islam Account Bus Res https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-06-2020-0183

Li J, Wu D (2020) Do corporate social responsibility engagements lead to real environmental, social, and governance impact? Manage Sci 66:2564–2588. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2019.3324

Lokuwaduge CSDS, Heenetigala K (2017) Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure for a sustainable development: an Australian study. Bus Strateg Environ 26:438–450. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1927

López-Toro A, Sánchez-Teba EM, Benítez-Márquez MD, Rodríguez-Fernández M (2021) Influence of ESGC indicators on financial performance of listed pharmaceutical companies alberto. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094556

Luque-Vílchez M, Gómez-Limón JA, Guerrero-Baena MD, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez P (2023) Deconstructing corporate environmental, social, and governance performance: heterogeneous stakeholder preferences in the food industry. Sustain Dev 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2488

Madden BJ (2022) Bet on innovation, not environmental, social and governance metrics, to lead the Net Zero transition. Syst Res Behav Sci 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2915

Marshall IJ, Kuiper J, Wallace BC (2015) Automating risk of bias assessment for clinical trials. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics 19:1406–1412. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2015.2431314

Mavlutova I, Fomins A, Spilbergs A, Atstaja D, Brizga J (2022) Opportunities to increase financial well-being by investing in environmental, social and governance with respect to improving financial literacy under covid-19: the case of Latvia. Sustain. 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010339

McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT (2021) Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods 12:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1411

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Merli R, Preziosi M (2018) The EMAS impasse: factors influencing Italian organizations to withdraw or renew the registration. J Clean Prod 172:4532–4543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.031

Minutolo MC, Kristjanpoller WD, Stakeley J (2019) Exploring environmental, social, and governance disclosure effects on the S&P 500 financial performance. Bus Strateg Environ 28:1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2303

Miralles-Quirós MM, Miralles-Quirós JL, Redondo-Hernández J (2019) The impact of environmental, social, and governance performance on stock prices: evidence from the banking industry. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26:1446–1456. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1759

Mohammad WMW, Wasiuzzaman S (2021) Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) disclosure, competitive advantage and performance of firms in Malaysia. Clean Environ Syst 2:100015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cesys.2021.100015

Moneva JM, Bonilla-Priego MJ, Ortas E (2020) Corporate social responsibility and organisational performance in the tourism sector. J Sustain Tour 28:853–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1707838

Montabon F, Sroufe R, Narasimhan R (2007) An examination of corporate reporting, environmental management practices and firm performance. J Oper Manag 25:998–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2006.10.003

Morioka SN, de Carvalho MM (2016) A systematic literature review towards a conceptual framework for integrating sustainability performance into business. J Clean Prod 136:134–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.104

Naffa H, Fain M (2020) Performance measurement of ESG-themed megatrend investments in global equity markets using pure factor portfolios methodology, PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244225

Ng TH, Lye CT, Chan KH, Lim YZ, Lim YS (2020) Sustainability in Asia: the roles of financial development in environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Soc Indic Res 150:17–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02288-w

Nishitani K, Nguyen TBH, Trinh TQ, Wu Q, Kokubu K (2021) Are corporate environmental activities to meet sustainable development goals (SDGs) simply greenwashing? An empirical study of environmental management control systems in Vietnamese companies from the stakeholder management perspective. J Environ Manage 296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113364

Nitescu DC, Cristea MA (2020) Environmental, social and governance risks-New challenges for the banking business sustainability. Amfiteatru Econ 22:692–706. https://doi.org/10.24818/EA/2020/55/692

Oncioiu I, Popescu DM, Aviana AE, Şerban A, Rotaru F, Petrescu M, Marin-Pantelescu A (2020) The role of environmental, social, and governance disclosure in financial transparency. Sustain 12:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12176757

Ortas E, Gallego-Álvarez I, Álvarez I (2019) National institutions, stakeholder engagement, and firms’ environmental, social, and governance performance. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 26:598–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1706

Ouni Z, Mansour JB, Arfaoui S (2020) Board/executive gender diversity and firm financial performance in Canada: the mediating role of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) orientation. Sustain 12:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208386

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Park SR, Oh KS (2022) Integration of ESG information into individual investors’ corporate investment decisions: utilizing the UTAUT framework. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.899480

Peng LS, Isa M (2020) Environmental, social and governance (Esg) practices and performance in shariah firms: agency or stakeholder theory? Asian Acad Manag J Account Financ 16:1–34. https://doi.org/10.21315/aamjaf2020.16.1.1

Petavratzi E, Sanchez-Lopez D, Hughes A, Stacey J, Ford J, Butcher A (2022) The impacts of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues in achieving sustainable lithium supply in the Lithium Triangle. Miner Econ 35:673–699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-022-00332-4

Pilkington A, Liston-Heyes C (1999) Is production and operations management a discipline? A citation/co-citation study. Int J Oper Prod Manag 19:7–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443579910244188

Pirtea MG, Noja GG, Cristea M, Panait M (2021) Interplay between environmental, social and governance coordinates and the financial performance of agricultural companies. Agric Econ (Czech Republic) 67:479–490. https://doi.org/10.17221/286/2021-AGRICECON

Qureshi MA, Akbar M, Akbar A, Poulova P (2021) Do ESG endeavors assist firms in achieving superior financial performance? A case of 100 best corporate citizens. SAGE Open 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211021598

Qureshi MA, Kirkerud S, Theresa K, Ahsan T (2020) The impact of sustainability (environmental, social, and governance) disclosure and board diversity on firm value: the moderating role of industry sensitivity. Bus Strateg Environ 29:1199–1214. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2427

Rajesh R (2020) Exploring the sustainability performances of firms using environmental, social, and governance scores. J Clean Prod 247:119600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119600

Rajesh R, Rajendran C (2020) Relating environmental, social, and governance scores and sustainability performances of firms: an empirical analysis. Bus Strateg Environ 29:1247–1267. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2429

Reboredo JC, Sowaity SMA (2022) Environmental, social, and governance information disclosure and intellectual capital efficiency in jordanian listed firms. Sustain. 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010115

Rehman RU, Abidin MZU, Ali R, Nor SM, Naseem MA, Hasan M, Ahmad MI (2021) The integration of conventional equity indices with environmental, social, and governance indices: Evidence from emerging economies. Sustain 13:1–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020676

Reveiz L, Chapman E, Asial S, Munoz S, Bonfill X, Alonso-Coello P (2015) Risk of bias of randomized trials over time. J Clin Epidemiol 68:1036–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.001

Romano M, Cirillo A, Favino C, Netti A (2020) ESG (Environmental, social and governance) performance and board gender diversity: the moderating role of CEO duality. Sustain 12:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219298

Sachin N, Rajesh R (2021) An empirical study of supply chain sustainability with financial performances of Indian firms. Environ Dev Sustain https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01717-1

Sahoo S, Kumar S (2022) Integration and volatility spillover among environmental, social and governance indices: evidence from BRICS countries. Glob Bus Rev 23:1280–1298. https://doi.org/10.1177/09721509221114699

Sandberg H, Alnoor A, Tiberius V (2022) Environmental, social, and governance ratings and financial performance: evidence from the European food industry. Bus Strateg Environ 2471–2489. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3259

Shahzad F, Baig MH, Rehman IU, Saeed A, Asim GA (2021) Does intellectual capital efficiency explain corporate social responsibility engagement-firm performance relationship? Evidence from environmental, social and governance performance of US listed firms. Borsa Istanbul Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2021.05.003

Shaikh I (2021) Environmental, social, and governance (Esg) practice and firm performance: an international evidence. J Bus Econ Manag 23:218–237. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2022.16202

Shakil MH (2021) Environmental, social and governance performance and financial risk: moderating role of ESG controversies and board gender diversity. Resour Policy 72:102144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102144

Shephard K, Rieckmann M, Barth M (2019) Seeking sustainability competence and capability in the ESD and HESD literature: an international philosophical hermeneutic analysis. Environ Educ Res 25:532–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1490947

Sul W, Lee Y (2020) Effects of corporate social responsibility for environmental, social, and governance sectors on firm value: a comparison between consumer and industrial goods companies. Eur J Int Manag 14:866–890. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2020.109817

Sultana S, Zulkifli N, Zainal D (2018) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) and investment decision in Bangladesh. Sustain 10:1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061831

Suttipun M, Yordudom T (2022) Impact of environmental, social and governance disclosures on market reaction: an evidence of Top50 companies listed from Thailand. J Financ Report Account 20:753–767. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRA-12-2020-0377

Taliento M, Favino C, Netti A (2019) Impact of environmental, social, and governance information on economic performance: evidence of a corporate “sustainability advantage” from Europe. Sustain. 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061738

Terzani S, Turzo T (2021) Religious social norms and corporate sustainability: The effect of religiosity on environmental, social, and governance disclosure. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 28:485–496. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2063

Ting IWK, Azizan NA, Bhaskaran RK, Sukumaran SK (2020) Corporate social performance and firm performance: comparative study among developed and emerging market firms. Sustain. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12010026

Tsang YP, Fan Y, Feng ZP (2023) Bridging the gap: building environmental, social and governance capabilities in small and medium logistics companies. J Environ Manag 338:117758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117758

Article CAS Google Scholar

Uyar A, Kuzey C, Karaman AS (2023) Does aggressive environmental, social, and governance engagement trigger firm risk? The moderating role of executive compensation. J Clean Prod 398:136542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136542

Valor C, Antonetti P, Carrero I (2018) Stressful sustainability: a hermeneutic analysis. Eur J Mark 52:550–574. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-12-2016-0712

Vanderley LB (2020) Conscientização ambiental na implantação de um sistema de gestão ambiental: um estudo de caso em uma empresa do Polo Industrial de Manaus. Sist Gestão 14:335–347. https://doi.org/10.20985/1980-5160.2019.v14n4.1474

Viranda DF, Sari AD, Suryoputro MR, Setiawan N (2020) 5 S Implementation of SME Readiness in Meeting Environmental Management System Standards based on ISO 14001:2015 (Study Case: PT. ABC). IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 722. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/722/1/012072

Wang S, Li J, Zhao D (2018) Institutional pressures and environmental management practices: the moderating effects of environmental commitment and resource availability. Bus Strateg Environ 27:52–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1983

Wang Y, Ghadimi M, Wang Q, Hou L, Zeraatkar D, Iqbal A, Ho C, Yao L, Hu M, Ye Z, Couban R, Armijo-Olivo S, Bassler D, Briel M, Gluud LL, Glasziou P, Jackson R, Keitz SA, Letelier LM, Ravaud P, Schulz KF, Siemieniuk RAC, Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt GH (2022) Instruments assessing risk of bias of randomized trials frequently included items that are not addressing risk of bias issues. J Clin Epidemiol 152:218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.10.018

Wasiuzzaman S, Ibrahim SA, Kawi F (2022) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure and firm performance: does national culture matter? Meditari Account Res https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-06-2021-1356

White HD, McCain KW (1998) Visualizing a discipline: an author co-citation analysis of information science, 1972–1995. J Am Soc Inf Sci 49:327–355

Google Scholar

Wolff RF, Moons KGM, Riley RD, Whiting PF, Westwood M, Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Kleijnen J, Mallett S (2019) PROBAST: a tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med 170:51–58. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1376

Xie J, Nozawa W, Yagi M, Fujii H, Managi S (2019) Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? Bus Strateg Environ 28:286–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2224

Xu J, Liu F, Shang Y (2021) R&D investment, ESG performance and green innovation performance: evidence from China. Kybernetes 50:737–756. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-12-2019-0793

Xu N, Liu J, Dou H (2022) Environmental, social, and governance information disclosure and stock price crash risk: evidence from Chinese listed companies. Front Psychol 13:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.977369

Yin YN, Wang Y, Jiang NJ, Long DR (2020) Can case management improve cancer patients quality of life?: a systematic review following PRISMA. Medicine (Baltimore) 99:e22448. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022448

Yu EPY, Van Luu B, Chen CH (2020) Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res Int Bus Financ 52:101192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101192

Zhang Q, Loh L, Wu W (2020) How do environmental, social and governance initiatives affect innovative performance for corporate sustainability? Sustain 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083380

Zhang Y, Ruan H, Tang G, Tong L (2021) Power of sustainable development: does environmental management system certification affect a firm’s access to finance? Bus Strateg Environ 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2839

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support received from the Federal University of Paraíba and the Federal Institute of Paraíba.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Federal University of Paraíba, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil

Anrafel de Souza Barbosa, Maria Cristina Basilio Crispim da Silva, Luiz Bueno da Silva & Sandra Naomi Morioka

University of Brasília, Brasília, Brazil

Vinícius Fernandes de Souza

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

For greater transparency, the individual contributions of the authors are as follows: AdSB: contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization, and project administration; MCBCdS and LBdS: contributed to validation, writing—review and editing, and supervision; SNM: contributed to validation, methodology, and writing—review and editing; and VFdS: contributed to validation and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anrafel de Souza Barbosa .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional information.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions