How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

Summary table

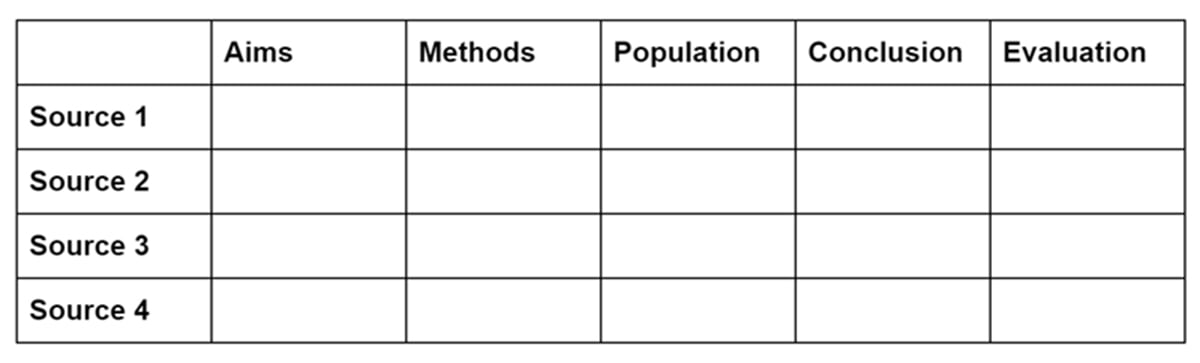

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

Synthesis matrix

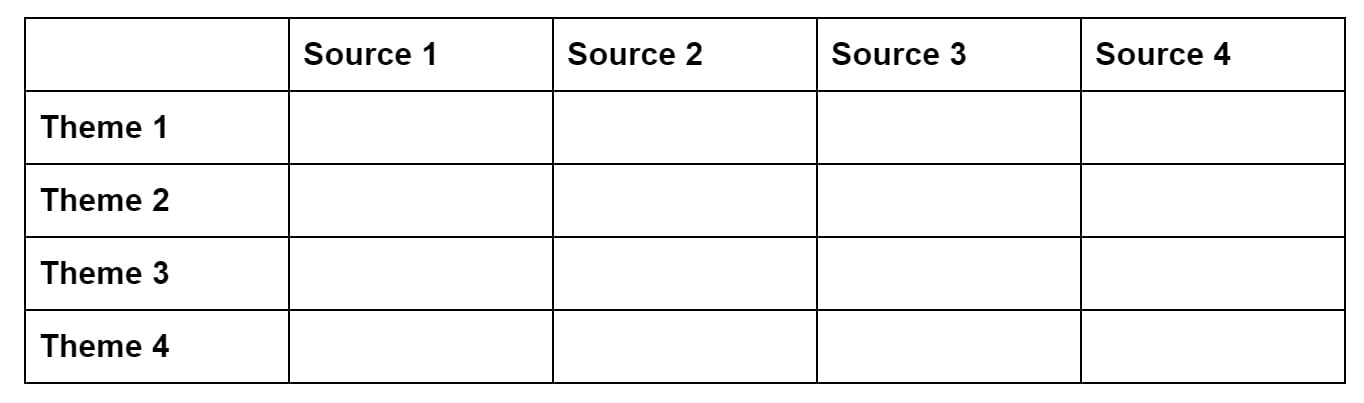

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

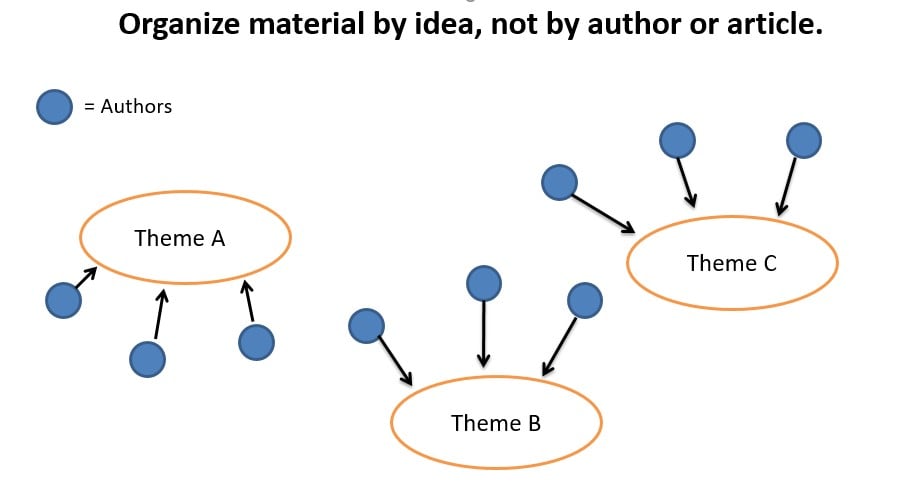

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

Published on July 4, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Synthesizing sources involves combining the work of other scholars to provide new insights. It’s a way of integrating sources that helps situate your work in relation to existing research.

Synthesizing sources involves more than just summarizing . You must emphasize how each source contributes to current debates, highlighting points of (dis)agreement and putting the sources in conversation with each other.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field or throughout your research paper when you want to position your work in relation to existing research.

Table of contents

Example of synthesizing sources, how to synthesize sources, synthesis matrix, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about synthesizing sources.

Let’s take a look at an example where sources are not properly synthesized, and then see what can be done to improve it.

This paragraph provides no context for the information and does not explain the relationships between the sources described. It also doesn’t analyze the sources or consider gaps in existing research.

Research on the barriers to second language acquisition has primarily focused on age-related difficulties. Building on Lenneberg’s (1967) theory of a critical period of language acquisition, Johnson and Newport (1988) tested Lenneberg’s idea in the context of second language acquisition. Their research seemed to confirm that young learners acquire a second language more easily than older learners. Recent research has considered other potential barriers to language acquisition. Schepens, van Hout, and van der Slik (2022) have revealed that the difficulties of learning a second language at an older age are compounded by dissimilarity between a learner’s first language and the language they aim to acquire. Further research needs to be carried out to determine whether the difficulty faced by adult monoglot speakers is also faced by adults who acquired a second language during the “critical period.”

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

To synthesize sources, group them around a specific theme or point of contention.

As you read sources, ask:

- What questions or ideas recur? Do the sources focus on the same points, or do they look at the issue from different angles?

- How does each source relate to others? Does it confirm or challenge the findings of past research?

- Where do the sources agree or disagree?

Once you have a clear idea of how each source positions itself, put them in conversation with each other. Analyze and interpret their points of agreement and disagreement. This displays the relationships among sources and creates a sense of coherence.

Consider both implicit and explicit (dis)agreements. Whether one source specifically refutes another or just happens to come to different conclusions without specifically engaging with it, you can mention it in your synthesis either way.

Synthesize your sources using:

- Topic sentences to introduce the relationship between the sources

- Signal phrases to attribute ideas to their authors

- Transition words and phrases to link together different ideas

To more easily determine the similarities and dissimilarities among your sources, you can create a visual representation of their main ideas with a synthesis matrix . This is a tool that you can use when researching and writing your paper, not a part of the final text.

In a synthesis matrix, each column represents one source, and each row represents a common theme or idea among the sources. In the relevant rows, fill in a short summary of how the source treats each theme or topic.

This helps you to clearly see the commonalities or points of divergence among your sources. You can then synthesize these sources in your work by explaining their relationship.

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Synthesizing sources means comparing and contrasting the work of other scholars to provide new insights.

It involves analyzing and interpreting the points of agreement and disagreement among sources.

You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field of research or throughout your paper when you want to contribute something new to existing research.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Topic sentences help keep your writing focused and guide the reader through your argument.

In an essay or paper , each paragraph should focus on a single idea. By stating the main idea in the topic sentence, you clarify what the paragraph is about for both yourself and your reader.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/synthesizing-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, signal phrases | definition, explanation & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc., unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Analysis and Synthesis

While analysis usually considers one text at a time, synthesis considers multiple, related texts. Rather than looking at one text’s purpose, construction, and contents, you look at several texts’ purposes, construction, and contents. What do these texts say about their shared topic? Where do they agree and disagree? Do they neglect or omit a perspective or idea?

When conducting a synthesis, you are not only looking for similarities and differences in multiple sources, but you are looking for what these sources say cumulatively. Synthesizing recent sources on a particular topic is how you answer this question: What is the current state of the research on this topic? A good way to begin is to document these differences and similarities in a synthesis matrix . A synthesis matrix will help you to locate and identify areas where sources overlap or differ, thus helping you to see what the current research is saying about the topic.

A good way to ensure you are synthesizing your sources is to be sure each topic you introduce is supported by two or more sources. If you locate an interesting point that only one text seems to make, you would still need to discuss how other texts are not discussing this specific point.

Applying Research Skills

While we stated what makes a credible review when discussing analysis, how do you determine the overall rating of an item you are interested in purchasing from multiple reviews? You synthesize these reviews to look for agreements, disagreements, and omissions.

If most of the reviews seem to point to the same flaw in the item, you will most likely accept this flaw as being real and credible. However, if some reviews reveal this flaw, while others claim this flaw does not exist, you will seek to find more reviews to try and find a consensus. After all, you want to be sure you know what you are buying.

Eventually, you will weigh the evidence from multiple reviews and rely on those you deem credible to make your decision. Basically, if you use reviews to determine your purchasing behavior, you are already analyzing and synthesizing texts.

- Synthesis. Authored by : Keith Boran and Sheena Boran. Provided by : University of Mississippi. Project : WRIT 250 Committee OER Project. License : CC BY: Attribution

Privacy Policy

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

UMGC Effective Writing Center Write to Synthesize: The Research Essay

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

In a synthesis, you bring things together. This combination, integration, or merging creates something new--your synthesis. The action of synthesis is basic to our world. Take, for example, what happens when a single oxygen molecule is combined with two hydrogen molecules. Water is created or synthesized. Hard to get more basic than that.

You also use synthesis to make personal decisions. If two instructors are teaching a class you must take, you may synthesize your past experiences with the teachers to choose the best class for you.

Research Essays:

Thesis driven.

In school, when writing a synthesis from your research, your sources may come from the school's library, a textbook, or the Internet. Here are some important points to keep in mind:

First, regardless of where your sources come from or how many you have, what you write should be driven by a thesis that you devise. After reading and studying your sources, you should form a personal point of view, a slant to connect your sources.

Here's a quick example--Let's say you've read three folktales: Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Little Red Riding Hood, and the Pied Piper--and now you must write a synthesis of them. As you study the three sources, you think about links between them and come up with this thesis:

Folktales use fear to teach children lessons.

Then you use this thesis to synthesize your three sources as you support your point of view. You combine elements from the three sources to prove and illustrate this thesis. Your support points could focus on the lessons for children:

- Lesson 1 : Never talk to strangers.

- Lesson 2 : Don't wander from home.

- Lesson 3 : Appearances can deceive us.

This step of outlining your thesis and main points is a crucial one when writing a synthesis. If your goal in writing a research essay is to provide readers a unified perspective based on sources, the unified perspective must be clear before the writing begins.

Once the writing begins, your point of view is then carried through to the paragraph and sentence levels. Let's examine some techniques for achieving the unity that a good synthesis requires. First, here’s an example of an unsuccessful attempt at synthesizing sources:

Many sources agree that capital punishment is not a crime deterrent. [This is the idea around which the sources should be unified. Now comes the sources] According to Judy Pennington in an interview with Helen Prejean, crime rates in New Orleans rise for at least eight weeks following executions (110). Jimmy Dunne notes that crime rates often go up in the first two or three months following an execution. “Death in the Americas” argues that America’s crime rate as a whole has increased drastically since the re-instatement of the death penalty in the 1960s. The article notes that 700 crimes are committed for every 100,000 Americans (2). Helen Prejean cites Ellis in her book to note that in 1980, 500,000 people were behind bars and in 1990 that figure rose to 1.1 million (112).

Sample student paragraph adapted from "Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources." Retrieved 2011 from https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/items/7dda80e7-b0b3-477c-a972-283b48cfdf5c

This paragraph certainly uses a number of sources. However, the sources are presented in a random, grocery list fashion. Besides the main point at the beginning, there is no further attempt to synthesize. The sources seem tossed in, like ingredients in a salad. Let's examine a possible revision of that paragraph and how an adequate synthesis might be achieved:

Major studies suggest that capital punishment fails to deter crime. Helen Prejean, in "Deadman Walking," reviews decades of statistics that indicate capital punishment does little to lower crime. [Key idea from topic sentence—"capital punishment fails to deter crime"— echoed in sentence about source–"capital punishment does little to lower crime." Repetition links source to main idea.] Based on this evidence, Prejean concludes “Executions do not deter crime . . . the U.S. murder rate is no higher in states that do not have the death penalty than those who do” (110). ["Based on this evidence" forces reader to refer back to "statistics" in previous sentence.] Prejean’s point is reiterated from a historical perspective in Dunne's article “Death in the Americas.” [This sentence provides a thought bridge between two sources.] Dunne first points out that, despite the social and economic upheavals from 1930 to 1960, crime rates were unchanged (2). [Linking phrase:"Dunne first points out"] However, after the reinstatement of the death penalty in the 1960s, “crime rates soared” (2). [Linking phase "However, Dunne notes."]

The result is a matrix of connective devices that unifies the sources around a key idea stated at the beginning. Although this matrix seems complex, it is actually built on a simple three-point strategy.

- Stay in charge . You the writer must control the sources, using them to serve your purpose. In good synthesis writing, sources are used to support what you, the writer, have already said in your own words.

- Stay focused . Your main point is not merely stated once and left to wilt. Your main idea is repeated and echoed throughout as a way to link the sources, to weave them together into a strong fabric of meaning.

- Stay strategic . Notice the "source sandwich" strategy at work. First, the author sets up the source with its background and relevance to the point. After the source comes a follows up in his/her own words as a way to bridge or link to the next part. In other words, the writer's own words are used like two slices of bread, with the source in the middle.

Follow these simple principles when using sources in your writing and you will achieve the most important goal of synthesis writing--to create a whole greater than its parts.

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Literature Review How To

- Things To Consider

- Synthesizing Sources

- Video Tutorials

- Books On Literature Reviews

What is Synthesis

What is Synthesis? Synthesis writing is a form of analysis related to comparison and contrast, classification and division. On a basic level, synthesis requires the writer to pull together two or more summaries, looking for themes in each text. In synthesis, you search for the links between various materials in order to make your point. Most advanced academic writing, including literature reviews, relies heavily on synthesis. (Temple University Writing Center)

How To Synthesize Sources in a Literature Review

Literature reviews synthesize large amounts of information and present it in a coherent, organized fashion. In a literature review you will be combining material from several texts to create a new text – your literature review.

You will use common points among the sources you have gathered to help you synthesize the material. This will help ensure that your literature review is organized by subtopic, not by source. This means various authors' names can appear and reappear throughout the literature review, and each paragraph will mention several different authors.

When you shift from writing summaries of the content of a source to synthesizing content from sources, there is a number things you must keep in mind:

- Look for specific connections and or links between your sources and how those relate to your thesis or question.

- When writing and organizing your literature review be aware that your readers need to understand how and why the information from the different sources overlap.

- Organize your literature review by the themes you find within your sources or themes you have identified.

- << Previous: Things To Consider

- Next: Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2018 4:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/literature-review

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

A Guide to Evidence Synthesis: What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Meet Our Team

- Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- What is Evidence Synthesis?

- Types of Evidence Synthesis

- Evidence Synthesis Across Disciplines

- Finding and Appraising Existing Systematic Reviews

- 0. Develop a Protocol

- 1. Draft your Research Question

- 2. Select Databases

- 3. Select Grey Literature Sources

- 4. Write a Search Strategy

- 5. Register a Protocol

- 6. Translate Search Strategies

- 7. Citation Management

- 8. Article Screening

- 9. Risk of Bias Assessment

- 10. Data Extraction

- 11. Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Evidence Synthesis Institute for Librarians

- Open Access Evidence Synthesis Resources

What are Evidence Syntheses?

What are evidence syntheses.

According to the Royal Society, 'evidence synthesis' refers to the process of bringing together information from a range of sources and disciplines to inform debates and decisions on specific issues. They generally include a methodical and comprehensive literature synthesis focused on a well-formulated research question. Their aim is to identify and synthesize all of the scholarly research on a particular topic, including both published and unpublished studies. Evidence syntheses are conducted in an unbiased, reproducible way to provide evidence for practice and policy-making, as well as to identify gaps in the research. Evidence syntheses may also include a meta-analysis, a more quantitative process of synthesizing and visualizing data retrieved from various studies.

Evidence syntheses are much more time-intensive than traditional literature reviews and require a multi-person research team. See this PredicTER tool to get a sense of a systematic review timeline (one type of evidence synthesis). Before embarking on an evidence synthesis, it's important to clearly identify your reasons for conducting one. For a list of types of evidence synthesis projects, see the next tab.

How Does a Traditional Literature Review Differ From an Evidence Synthesis?

How does a systematic review differ from a traditional literature review.

One commonly used form of evidence synthesis is a systematic review. This table compares a traditional literature review with a systematic review.

Video: Reproducibility and transparent methods (Video 3:25)

Reporting Standards

There are some reporting standards for evidence syntheses. These can serve as guidelines for protocol and manuscript preparation and journals may require that these standards are followed for the review type that is being employed (e.g. systematic review, scoping review, etc).

- PRISMA checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

- PRISMA-P Standards An updated version of the original PRISMA standards for protocol development.

- PRISMA - ScR Reporting guidelines for scoping reviews and evidence maps

- PRISMA-IPD Standards Extension of the original PRISMA standards for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of individual participant data.

- EQUATOR Network The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that seeks to improve the reliability and value of published health research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting and wider use of robust reporting guidelines. They provide a list of various standards for reporting in systematic reviews.

Video: Guidelines and reporting standards

PRISMA Flow Diagram

The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of an evidence synthesis. It maps the search (number of records identified), screening (number of records included and excluded), and selection (reasons for exclusion). Many evidence syntheses include a PRISMA flow diagram in the published manuscript.

See below for resources to help you generate your own PRISMA flow diagram.

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Tool

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Word Template

- << Previous: Our Published Reviews and Protocols

- Next: Types of Evidence Synthesis >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 4:35 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Synthesizing Sources

Learning objectives.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- synthesize key sources connecting them with the research question and topic area.

7.1 Overview of synthesizing

7.1.1 putting the pieces together.

Combining separate elements into a whole is the dictionary definition of synthesis. It is a way to make connections among and between numerous and varied source materials. A literature review is not an annotated bibliography, organized by title, author, or date of publication. Rather, it is grouped by topic to create a whole view of the literature relevant to your research question.

Your synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers you collected as well as your ability to integrate the results of your analysis into your own literature review. Each paper collected should be critically evaluated and weighed for “adequacy, appropriateness, and thoroughness” ( Garrard, 2017 ) before inclusion in your own review. Papers that do not meet this criteria likely should not be included in your literature review.

Begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline where you will summarize, using common themes you have identified and the sources you have found. The summary grid or outline will help you compare and contrast the themes so you can see the relationships among them as well as areas where you may need to do more searching. Whichever method you choose, this type of organization will help you to both understand the information you find and structure the writing of your review. Remember, although “the means of summarizing can vary, the key at this point is to make sure you understand what you’ve found and how it relates to your topic and research question” ( Bennard et al., 2014 ).

As you read through the material you gather, look for common themes as they may provide the structure for your literature review. And, remember, research is an iterative process: it is not unusual to go back and search information sources for more material.

At one extreme, if you are claiming, ‘There are no prior publications on this topic,’ it is more likely that you have not found them yet and may need to broaden your search. At another extreme, writing a complete literature review can be difficult with a well-trod topic. Do not cite it all; instead cite what is most relevant. If that still leaves too much to include, be sure to reference influential sources…as well as high-quality work that clearly connects to the points you make. ( Klingner, Scanlon, & Pressley, 2005 ).

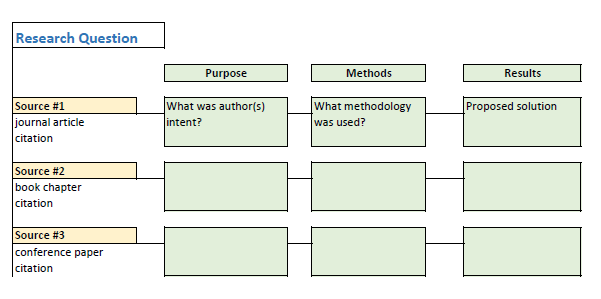

7.2 Creating a summary table

Literature reviews can be organized sequentially or by topic, theme, method, results, theory, or argument. It’s important to develop categories that are meaningful and relevant to your research question. Take detailed notes on each article and use a consistent format for capturing all the information each article provides. These notes and the summary table can be done manually, using note cards. However, given the amount of information you will be recording, an electronic file created in a word processing or spreadsheet is more manageable. Examples of fields you may want to capture in your notes include:

- Authors’ names

- Article title

- Publication year

- Main purpose of the article

- Methodology or research design

- Participants

- Measurement

- Conclusions

Other fields that will be useful when you begin to synthesize the sum total of your research:

- Specific details of the article or research that are especially relevant to your study

- Key terms and definitions

- Strengths or weaknesses in research design

- Relationships to other studies

- Possible gaps in the research or literature (for example, many research articles conclude with the statement “more research is needed in this area”)

- Finally, note how closely each article relates to your topic. You may want to rank these as high, medium, or low relevance. For papers that you decide not to include, you may want to note your reasoning for exclusion, such as ‘small sample size’, ‘local case study,’ or ‘lacks evidence to support assertion.’

This short video demonstrates how a nursing researcher might create a summary table.

7.2.1 Creating a Summary Table

Summary tables can be organized by author or by theme, for example:

For a summary table template, see http://blogs.monm.edu/writingatmc/files/2013/04/Synthesis-Matrix-Template.pdf

7.3 Creating a summary outline

An alternate way to organize your articles for synthesis it to create an outline. After you have collected the articles you intend to use (and have put aside the ones you won’t be using), it’s time to identify the conclusions that can be drawn from the articles as a group.

Based on your review of the collected articles, group them by categories. You may wish to further organize them by topic and then chronologically or alphabetically by author. For each topic or subtopic you identified during your critical analysis of the paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which ones in the group differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for the contradiction (for example, differences in population demographics). Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic as the entire group of studies relate to it. For example, you may have several studies that agree on outcome, such as ‘hands on learning is best for science in elementary school’ or that ‘continuing education is the best method for updating nursing certification.’ In that case, you may want to organize by methodology used in the studies rather than by outcome.

Organize your outline in a logical order and prepare to write the first draft of your literature review. That order might be from broad to more specific, or it may be sequential or chronological, going from foundational literature to more current. Remember, “an effective literature review need not denote the entire historical record, but rather establish the raison d’etre for the current study and in doing so cite that literature distinctly pertinent for theoretical, methodological, or empirical reasons.” ( Milardo, 2015, p. 22 ).

As you organize the summarized documents into a logical structure, you are also appraising and synthesizing complex information from multiple sources. Your literature review is the result of your research that synthesizes new and old information and creates new knowledge.

7.4 Additional resources:

Literature Reviews: Using a Matrix to Organize Research / Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota

Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources / Indiana University

Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix / Florida International University

Sample Literature Reviews Grid / Complied by Lindsay Roberts

Select three or four articles on a single topic of interest to you. Then enter them into an outline or table in the categories you feel are important to a research question. Try both the grid and the outline if you can to see which suits you better. The attached grid contains the fields suggested in the video .

Literature Review Table

Test yourself.

- Select two articles from your own summary table or outline and write a paragraph explaining how and why the sources relate to each other and your review of the literature.

- In your literature review, under what topic or subtopic will you place the paragraph you just wrote?

Image attribution

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students Copyright © by Linda Frederiksen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Open synthesis and the coronavirus pandemic in 2020

Neal r. haddaway.

a Stockholm Environment Institute, Linnégatan 87D, Stockholm, Sweden

b African Centre for Evidence, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

c The SEI Centre of the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence, Stockholm, Sweden

d Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, Berlin, Germany

Elie A. Akl

e Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

f Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact (HE&I), McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

g The Global Evidence Synthesis Initiative (GESI) Secretariat, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

Matthew J. Page

h School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

Vivian A. Welch

i Bruyere Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

j Campbell Collaboration, Oslo, Norway

k School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa

Ciara Keenan

l Campbell UK and Ireland, Belfast, UK

m Centre for Evidence and Social Innovation, Queen's University Belfast, Belfast, UK

Tamara Lotfi

Associated data.

- • Open Science principles are vital for ensuring reproducibility, trust, and legacy.

- • Evidence synthesis is a vital means of summarizing research for decision-making.

- • Open Synthesis is the application of Open Science principles to evidence synthesis.

- • Open approaches to planning, conducting, and reporting synthesis have many benefits.

- • We call on the evidence synthesis community to embrace Open Synthesis.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic of 2020 has caused high levels of mortality and continues to threaten the lives of the global population [ 1 ]. The pandemic has amounted to a “once in a lifetime” event for humanity and has affected it across its different sectors of existence: health, education, economy, environment, etc. The pandemic continues to threaten job prospects for millions of people and has resulted in widespread economic turmoil [ 2 ]. It has also led to the cancellation of numerous conferences (e.g., [ 3 ]) and research fieldwork and closed offices across the globe.

As the scientific community grapples to respond to the massive and rapidly evolving crisis, the volume of research literature that has been published in relation to the outbreak has expanded rapidly ( Figure 1 ). Simultaneously, efforts to synthesize this growing evidence base have begun, both through ongoing traditional approaches to independent systematic reviews (e.g., [ 4 , 5 ]), and through both rapid and living systematic reviews (e.g., https://covidrapidreviews.cochrane.org/search/site ). Rapid systematic reviews provide in a timely way the evidence needed to inform policy making under urgent circumstances. On the other hand, living systematic reviews ensure that any evidence synthesis is up to date with the latest evidence (e.g., by the L.OVE team at Epistemonikos).

Proliferation of publications on COVID-19 found in PubMed on 5th June 2020 with creation dates in 2020 [corresponding to week 23] (all fields search for (“COVID-19″ OR “nCoV” OR ″2019 novel coronavirus” OR ″2019-nCoV” OR “SARS-CoV-2″) AND research). A total of 19,260 hits were identified. Data and code were freely accessible from https://github.com/nealhaddaway/COVID19/ . Week of 2020 calculated based on PubMed creation date. Records lacking creation date were excluded.

As the volume of evidence increases and decision makers and scientists struggle to grapple with the rapidly expanding evidence base, many research groups are volunteering to support these efforts by using online collaborative tools and virtual workspaces, in an effort to support continued working during challenging times, and also to help identify, map, and synthesize research as it emerges.

This work faces a suite of challenges because of the often closed nature of science. The major challenges are the duplication of efforts (leading to research waste), the inefficiency in conducting research, and missing the opportunity to address important questions. Open science principles present an opportunity to address these challenges in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. They would also ensure that the research in the field is more collaborative, transparent, and rigorous. This article argues for, and illustrates how, to apply the principles of Open Science to the field of evidence synthesis, a concept we refer to as Open Synthesis [ 6 ]. We use the COVID-19 pandemic as a case in point to highlight the potential significant benefits of Openness to the research, policy, and practice communities.

1. Evidence synthesis

Evidence synthesis is the name for research methodologies that involve identifying, collating, appraising, and summarizing a body of research evidence using tried and tested systematic and robust literature review methods: i.e., systematic reviews and systematic maps [ 7 ]. Systematic reviews are now widely used in the field of health care as a “gold standard” for summarizing evidence to provide support for decision-making in policy and practice, through a variety of knowledge translation products and practice guidelines [ 8 ].

However, systematic reviewers face challenges as a result of an often closed academic system; research can be difficult to find and download without access to expensive bibliographic databases [ 9 ]; primary research articles and the systematic reviews that synthesize them are hidden behind paywalls [ 10 , 11 ]; reporting of methods used in trials and syntheses is often deficient to some degree, hampering verification and learning about methodology [ 12 ]; research data are often not made public, particularly when produced by organizations with commercial interests, such as pharmaceutical companies [ 13 ]; analytical code is rarely shared and statistical methods can be hard to verify [ 14 ], and educational materials to train the next generation of evidence synthesists are often not made public [ 15 ].

2. Open Science

Open Science has central premises relating to accessibility and the collaborative nature of knowledge creation and the knowledge itself [ 16 ]. These principles (see Table 1 ) include concepts such as open access (unrestricted availability of research publications,11) and open data (freely accessible research data used in analyses; [ 17 ]) that together support efficient, transparent, and rigorous research.

Table 1

Main concepts within Open Science [translated and adapted from OpenScienceASAP; http://openscienceasap.org/open-science ]

There are various definitions of Open Science, ranging from relatively simple classifications of “data, analysis, publications, and comments” [ 18 ] to somewhat more elaborate frameworks (see Table 1 ), all the way to complex hierarchical conceptual models [ 19 ]. Although these classifications differ in their complexity, they each attempt to cover all aspects of research processes from initiation to communication.

3. Open Synthesis

Some of the problems with traditional approaches to evidence synthesis described above (access to data, methods, publications, etc.) can be and indeed are being mitigated by applying these Open Science principles to evidence synthesis; the result has been termed Open Synthesis [ 6 ]. Open Synthesis was first proposed to apply Open Access, Open Data, Open Source and Open Methodology to evidence synthesis, with the possible addition of Open Education. We propose a finer resolution based on more complex taxonomies (e.g., [ 19 ]).

We suggest that such Open Synthesis would support the transfer of knowledge from primary research to decision support tools and evidence portals (e.g., the Teaching and Learning Toolkit), particularly during humanitarian crises; for example, Evidence Aid hosts a freely accessible evidence repository that holds summaries of COVID-19 relevant evidence ( https://www.evidenceaid.org/coronavirus-covid-19-evidence-collection/ ) [ 20 ]. Many Open Synthesis resources have been developed and assembled in an effort to facilitate access to the novel evidence base emerging in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. These examples are (understandably) almost exclusively related to the field of health, but the evidence base will become increasingly multidisciplinary and cross-sectoral as research focus spreads to include the societal and environmental impacts of the outbreak and subsequent social policies, such as widescale lockdowns. The key components of Open Synthesis are described in Figure 2 , and examples are given below.

Provisional core principles of Open Synthesis. This is the subject of discussion by an international, interdisciplinary Open Synthesis Working Group ( https://opensynthesis.github.io ) that aims to define and describe pathways toward more Open evidence synthesis.

3.1. Open collaboration

The COVID-19 evidence map of emerging literature produced by the Meta-Evidence blog was open to interested collaborators (before the project was discontinued because of considerable overlap with several other projects) and involved substantial efforts to translate and extract information from literature written in Chinese. The synthesizing group under COVID Evidence Network to support Decision makers (COVID-END; https://www.mcmasterforum.org/networks/covid-end/working-groups/synthesizing ) supports efforts to synthesize the evidence that already exists in ways that are more coordinated and efficient and that balance quality and timeliness. Cochrane's COVID Rapid Reviews repository provides space for Open Collaboration by connecting authors interested in addressing the same rapid review question that were submitted by the public.

3.2. Open discovery

To enable free (i.e., not paywalled) searching for relevant evidence, various efforts are seeking to build “living” bibliographies and databases of research on COVID-19. For example, the CORD19 database (MIT); the COVID-19 living systematic map (EPPI center); Cochrane's COVID-19 Study Register; the Norwegian Institute of Public Health's live map of COVID-19 evidence. Similarly, the McMaster GRADE Center is collaborating with the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and others to map recommendations relevant to COVID-19 and make them publicly available (including the strength and certainty of supporting evidence) [ 21 ].

3.3. Open methods

Efforts exist to ensure that evidence syntheses use transparent and well reported methods to improve repeatability and usability. For example, the systematic review registry PROSPERO has provided a link to already registered reviews of human and animal studies relevant to COVID-19.

3.4. Open data

Freely accessible data (including those extracted and generated within the process of conducting a systematic review) are being made available for reuse and analysis. From evidence syntheses, the Epistemonikos COVID-19 collection archives data extracted from within reviews in a publicly accessible database ( https://www.epistemonikos.cl/all-about-covid-19/ ).

3.5. Open source

Freely useable and adaptable tools for analysis and visualization have been made available online to support the conduct and communication of COVID-19 relevant research, for example, corona-cli (code for analyzing and visualizing data on the outbreak); the EviAtlas tool for mapping the geographical spread of evidence on COVID-19 [ 22 ].

3.6. Open code

Many researchers routinely publish the analytic code to accompany their research (e.g., R script for statistical analyses), although to date this practice is not common in the syntheses we have examined; perhaps because this is challenging where reviewers have not made use of code-driven software, and code does not readily exist (e.g., for reviews conducted using RevMan software). However, some examples of Open Code in primary research include code to webscrape COVID data from Worldometers and epidemiological modeling code for COVID.

3.7. Open access

Several publishers and journals have made COVID-19 relevant research articles and evidence syntheses freely accessible, including the Cochrane COVID-19 evidence collection and several Elsevier journals including Journal of Clinical Epidemiology and The Lancet ( https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-center ). Systematic reviewers can facilitate Open Access by ensuring their reviews are freely accessible (e.g., by publishing in open access journals or depositing preprints or postprints in publicly accessible repositories) but also by facilitating access to the primary research synthesized in their reviews (e.g., by providing DOIs for the full texts of their included studies).

3.8. Open peer review:

Although most journals do not currently publish peer review reports and revisions of systematic reviews, some resources exist to support this, including the Outbreak Science Rapid PREReview for prepublication peer review.

3.9. Open education

Various freely accessible training resources (e.g., courses, webinars, and handbooks) exist for evidence synthesis methodology, including #ESTraining provided by the Collaboration for Environmental Evidence and Stockholm Environment Institute and webinars provided by the Global Evidence Synthesis Initiative.

3.10. Open interests

Systematic reviews have been shown to suffer from poor reporting of funding, role of funders, and conflicts of interest in general [ 23 ]. Open Interests calls for individuals to transparently declare possible financial and nonfinancial interests—ideally, this would be performed by all parties involved in the conduct and publication of systematic reviews (including educators, engaged stakeholders, review authors, advisory group members, peer reviewers, editors, and publishers); these should be updated regularly. In practical terms, this could either be a declaration at the point of publication (e.g., review publications, educational materials, or peer review comments) or via a freely accessible central database of interests. At present, no Open Interests initiative exists.

3.10.1. Challenges of implementing Open Synthesis and their relation to Open Science criticisms

Although no criticisms have been fielded against Open Synthesis yet, some researchers have raised concerns about Open Science. We have described some of these in Table 2 . These concerns either relate to openness itself as a practice or the application and enforcement of Open Science within current institutions and incentive structures.

Table 2

Concerns relating to Open Science and their applicability to and mitigation within Open Synthesis

In addition, there are risks associated with some of the practices that may be facilitated by Open Synthesis, for example, 1) living systematic reviews may involve repeated incremental rerunning of meta-analyses, leading to increased chances of false positive that need to be accounted for (e.g., [ 40 ]); 2) updates may need to account for changes in best practice in risk of bias assessments as novel methods become available, potentially involving reassessment of studies identified in the original review.

These are not problems with Open Synthesis but rather important issues that should be addressed when planning incentives and infrastructure in support of Open Syntheses. However, a pathway to Open systematic reviews and systematic maps will involve many steps and a diverse array of different actions; these changes should not be expected overnight, and there is a need for detailed discussion about implications and pitfalls. That said, it is generally accepted that the advantages of Open Science outweigh the disadvantages [ 41 ].

3.10.2. Open Synthesis and current systematic review traditions

At present, some of these Open Synthesis practices are enforced or encouraged by review coordinating bodies. Cochrane reviews can be made immediately Open Access at the point of publication for a fee (payable by authors) or made free after a 12 month period (otherwise requiring subscription to access, green Open Access). Cochrane does not yet require systematic review–extracted data to be made public [ 42 ]. While methods in Cochrane reviews are typically well-reported thanks to the Methodological Expectations for Cochrane Intervention Reviews reporting standards [ 43 ], the “raw” data extracted from primary studies within a review are not typically included. All Campbell Collaboration reviews are published in their Open Access journal. Transparent and Open Methods are required by the Methodological Expectations for Campbell Collaboration Intervention Reviews. Open Data and Code are in the vision for the future of the journal [ 44 ]. For both organizations, review protocols are published online and time-stamped before work commences, as should be performed with all systematic reviews and maps (e.g., in PROSPERO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, or published in a suitable journal).

3.10.3. Ways forward

Adopting truly Open evidence synthesis approaches has the potential to globalize research, break down barriers to data sharing and collaboration, and mitigate inequality in knowledge availability (e.g., a large body of Chinese coronavirus trials was recently translated and mapped by researchers from Lanzhou University). Open synthesis also supports either living systematic reviews or intermittent updates; it is agnostic toward the framework chosen to update reviews. Importantly, it emphasizes the need to facilitate updates however that may occur.

Moreover, Open Synthesis of evidence will provide guideline developers with faster and better access to the synthesis methods, findings, conflict of interest information, and other elements necessary for guideline development, and subsequently, improve the quality and efficiency of guideline development.

Achieving the optimal impact of Open Synthesis requires the consideration of other principles. Of outmost importance is to respond to the knowledge needs of decision makers by adopting valid prioritisty setting approaches. Similarly, it has to feed into knowledge translation tools that are appropriate to the target decision makers. In addition, it should build on emerging concepts, such as Evidence Synthesis 2.0 [ 33 ], to ensure the efficiency of the process and appropriateness of the output.

We encourage adoption of these principles across all disciplines to meet the social, legal, ethical, and economic challenges of the global COVID-19 pandemic, such as supporting home-based education for children out of school; mitigating social impacts of isolation; responding to the increased risk and severity of domestic violence, global food insecurity, or the implications of social lockdowns on environmental recovery from long-term anthropogenic disturbance and climate change.

We call for increasing application of Open Science and Open Synthesis principles across disciplines both within and beyond the COVID-19 epidemic to support evidence production, synthesis, and evidence-informed policy. By embracing Open Synthesis, evidence synthesis communities from all disciplines can maximize the efficiency, impact, and legacy of systematic reviews and better support decision-making, particularly in global crises such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, establishing a more resilient and collaborative future in the event of similar global challenges.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Neal R. Haddaway: Conceptualization, Data curation. Elie A. Akl: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Matthew J. Page: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Vivian A. Welch: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Ciara Keenan: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Tamara Lotfi: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declarations of interest: NRH and TL are the coordinators of the Open Synthesis Working Group, a voluntary collaboration of stakeholders interested in the application of Open Science principles in evidence synthesis conduct and publication.

Funding: This work was produced in part as a result of funding from FORTE, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare (2018-01619).

Author’s contributions: NRH and TL developed the concept for the manuscript. NRH drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.032 .

Supplementary data

Research Guides

Information Literacy & Library Research: Information Synthesis

- Table of Contents

- Information Literacy

- Research Process

- Topics and Background Research

- Writing a Research Question

- Source Types

- Keyword Basics

- Research: A Journey in Small Steps

- Keywords and Boolean Operators

- Using Databases

- How to Find Books and eBooks

- Popular vs Scholarly

- "Search the Library" through the EBSCO Discovery Service

- Applying the CRAAP Test to Sources

- Citing with MLA 9

- Information Synthesis

- How to Critically Read Academic Articles

- Information Has Value

- How to Avoid Plagiarism

- Module 6. Reflecting

- Academic Honesty and Plagiarism

- Copyright and Fair Use

- Creative Commons Licenses

- Information has Value

- Joining the Scholarly Conversation

- Library Classification Systems

- Google Scholar

- Subject Databases

- Find Journal by Title

- Advanced Search Strategies

- MLA Style Examples

- APA Style Examples

Introduction: Scholarship is a Conversation

Information synthesis is the process of analyzing and evaluating information from various sources, making connections between the information found, and combining the recently acquired information with prior knowledge to create something new. Without information synthesis strategies, we cannot derive new knowledge from these large amounts of data. Effective information synthesis is also vital in developing effective writing and communication skills to share new knowledge.

Here is an example of a paragraph where the authors have synthesized information across several sources on the idea of information synthesis. Note also how connector words are used to make the writing flow.

Information synthesis is a key skill for participants in our knowledge society and requires complex processing (Fitzgerald, 2004; Goldman, 2004). Yet information literacy instruction and practice tend to favor easily-defined skills that often only emphasize the search component of the research process, leaving out higher order processes like information synthesis (Lloyd, 2007; Montiel-Overall, 2007). Similarly, in the writing classroom, teachers are largely unfamiliar with how to teach synthesis sometimes implying it is a linear process (McGinley, 1992), leading Mateos and Sole (2009) to call for a “unique, careful teaching approach” (p. 448).

Creating the Information Synthesis Matrix

Important questions to answer when you are reading your sources are: What are the major themes or ideas? How are these ideas related to each other? What are my assertions based on what I’ve learned about these ideas and my prior knowledge on this topic?

Keeping track of ideas gets more complex the more sources you are using. This is where the information synthesis matrix comes in. It is a table where the first column collects the ideas, and all the other columns are taken up by your sources, one source per column. Each row represents a unique idea. In the intersection of sources and ideas, the cells of the matrix, you provide short descriptions of how this idea is represented in that source (adding the page number at the end of the description can also remind you where you got the idea).You leave the cell blank if that idea does not appear in a source. If you find an existing idea that already has a row, find the cell where your new source and that idea intersect, and put the description there. Make sure that your descriptions are in your own words so they can easily be used when writing a synthesized paragraph for your paper and are not plagiarized.

This is an abbreviated matrix but you can view more complete synthesis matrix examples to help you understand how to create your own.

Note for INFO 1010:

For the Synthesize: Module 5 Assignment you create a synthesis matrix using the sources you found for your paper. The synthesis matrix is a good way to keep track of the ideas you read about in your sources which will be very helpful when you create an outline for your paper and write a first draft.

Shortened video (9:47):

Full Length Video (21:44):

Paraphrasing, Summarizing, and Quoting

When creating your synthesis matrix, it is best for you to keep the information in each cell shorter, so the size of the matrix stays manageable. This can be done by summarizing or paraphrasing how your sources talk about each main idea. Summarizing and paraphrasing are also good ways to make sure you use your own voice more, which is an important part of synthesis. An added benefit of using your own voice is that you are avoiding plagiarism . Please keep quotes to a minimum as professors are interested in reading your original thoughts and interpretations.

Paraphrasing is when you use different words to say the same thing without actually quoting the source. It involves fully understanding the original source and then using your own words to convey the same idea. Make sure to add the page number of the source (if possible) in the cell with your paraphrase.

Summarizing is when you give an overview of the text. It will always reduce the content to the important points without using details or examples. Summarizing is ideal for your synthesis matrix because you will be able to get the idea of how that source talks about the main point without taking a lot of space. Including the page number from the original source will help you know where to return for those details when you start to write your paper.

Quoting is when you take the exact wording used by your source and use it in your paper. Quoting is good for providing strong evidence to support your point. However, use quotes sparingly or not at all. Good things to quote are definitions or text that is written so beautifully you want to frame it to hang on your wall. When deciding to use a quote in your matrix, put it in quotation marks and include the page number. This way you will know it is a quote and not accidentally plagiarize later, and quotes require an in-text citation with a page number. If the quote is too long for the cell, include part of the quote and add [...] to show there is more and then end with the page number (p. #).

Writing Using the Information Synthesis Matrix

Once you have read enough sources and you have added them to your synthesis matrix, it is time to use the matrix to write your paper. Because you have collected all the interesting ideas in your matrix (in first column, one idea per row), you can now use that first column to create an outline for your paper by determining a logical order in which to discuss the ideas. Next, you can use each row to write a paragraph or section on that idea, integrating information from all the sources that had something on that idea. Finally, you can also easily see when you don’t have enough sources for an idea. In some cases, the idea might not be that important for your paper. Other times the idea is something that you want to include in your paper so you go out and find more sources, specifically on that idea.

When you write a paragraph in which you synthesize ideas, you can use so-called transition words that: 1) add to an idea (e.g. furthermore, moreover, in addition); 2) introduce information (e.g. for example, for instance, including, as an illustration); 3) compare and contrast (e.g. similarly, in the same way, conversely, however); 4) make a concession (e.g. nevertheless, even though, despite this). See http://www.csuci.edu/cis/CIS_Science_Writing_Pilot/helpful-steps.pdf for more information.

A more detailed description on creating and using an information synthesis matrix in the writing process, was created by Utah State University: https://libguides.usu.edu/synthesizing_info

- << Previous: Module 5. Synthesizing

- Next: How to Critically Read Academic Articles >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 2:17 PM

- URL: https://library.suu.edu/LibraryResearch

Contact the Sherratt Library

351 W. University Boulevard Cedar City, UT 84720 (435) 586-7933 [email protected]

Connect with us

share this!

April 8, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

On-surface synthesis of carbyne: An sp-hybridized linear carbon allotrope

by Science China Press

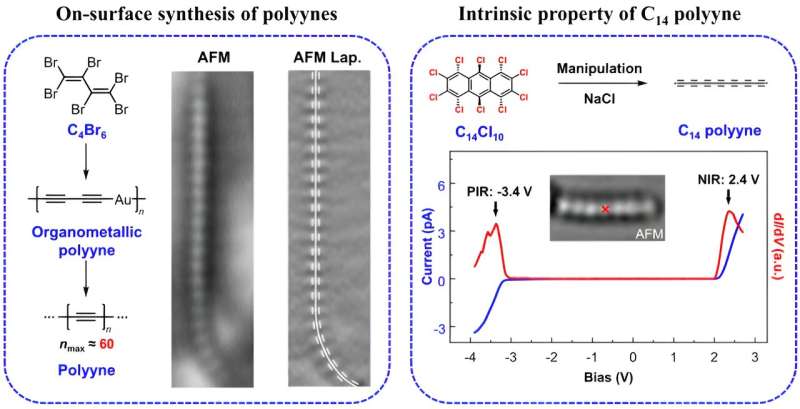

In a study led by Prof. Wei Xu (Interdisciplinary Materials Research Center, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tongji University) and published in the journal National Science Review , a research team achieved the successful synthesis of a one-dimensional carbon chain on the Au(111) surface, with the longest chain containing approximately 120 carbon atoms, and the polyynic nature of the carbon chain was unambiguously characterized by bond-resolved atomic force microscopy (AFM).

The creation of new carbon forms with different topologies has emerged as an exciting topic in both fundamental chemistry and materials science. Carbyne (linear carbon chain), an elusive sp-hybridized linear carbon allotrope, has fascinated chemists and physicists for decades. Due to its high chemical reactivity and extreme instability, carbyne was much less explored.

On-surface synthesis is emerging as a promising approach for atomically precise fabrication of highly reactive 1D nanostructures with sp-hybridization that could hardly be synthesized via conventional solution synthetic chemistry. Xu's group employed the on-surface synthesis strategy, utilizing C 4 Br 6 as a precursor, to synthesize polyynic carbon chains on the Au(111) surface via dehalogenative polymerization and subsequent demetallization, and the longest chain consists of ~120 carbon atoms .

Bond-resolved AFM unambiguously revealed the polyynic structure of carbon chains with alternating single and triple bonds.

Moreover, to measure the intrinsic electronic property of the carbon chain, a specific C 14 polyyne was produced via tip-induced dehalogenation and ring-opening of the decachloroanthracene molecule (C 14 Cl 10 ) on a bilayer NaCl/Au(111) surface at 4.7 K. The electronic properties were characterized by scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS), exhibiting two pronounced peaks at –3.4 V and 2.4 V, corresponding to the positive and negative ion resonances (PIR and NIR), respectively, exhibiting a band gap of 5.8 eV.

This work from Prof. Wei Xu's group provides bond-resolved experimental insights into the structure of the polyynic carbon chains and may open an avenue for the synthesis and characterization of long polyynes without endgroups.

Provided by Science China Press

Explore further

Feedback to editors

First languages of North America traced back to two very different language groups from Siberia

4 minutes ago

'Swallowed,' torn up or live on: How Earth will fare when the sun dies

17 minutes ago

Research team exerts electrical control over polaritons, hybridized light-matter particles, at room temperature

24 minutes ago

A natural touch for coastal defense: Hybrid solutions may offer more benefits in lower-risk areas

5 hours ago

Public transit agencies may need to adapt to the rise of remote work, says new study

Broken record: March is 10th straight month to be hottest on record, scientists say

Early medieval money mystery solved

15 hours ago

Finding new chemistry to capture double the carbon

17 hours ago

Americans are bad at recognizing conspiracy theories when they believe they're true, says study

18 hours ago

A total solar eclipse races across North America as clouds part along totality