Making Britain

Discover how South Asians shaped the nation, 1870-1950

- About the database

- Individuals

- Organizations

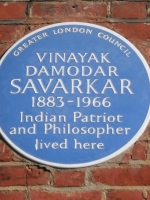

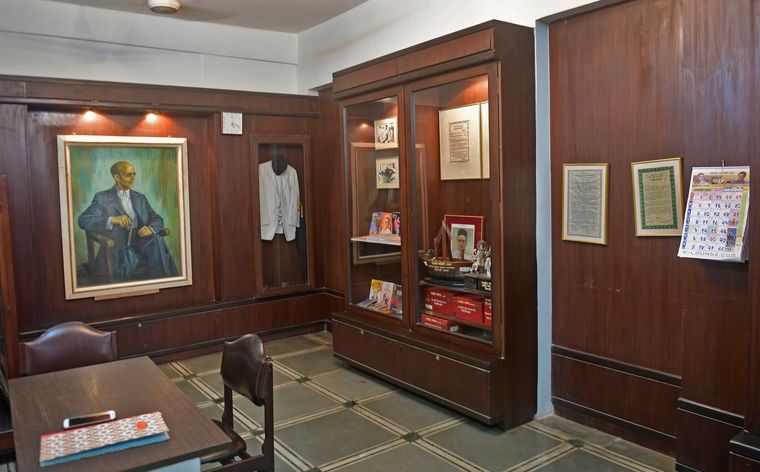

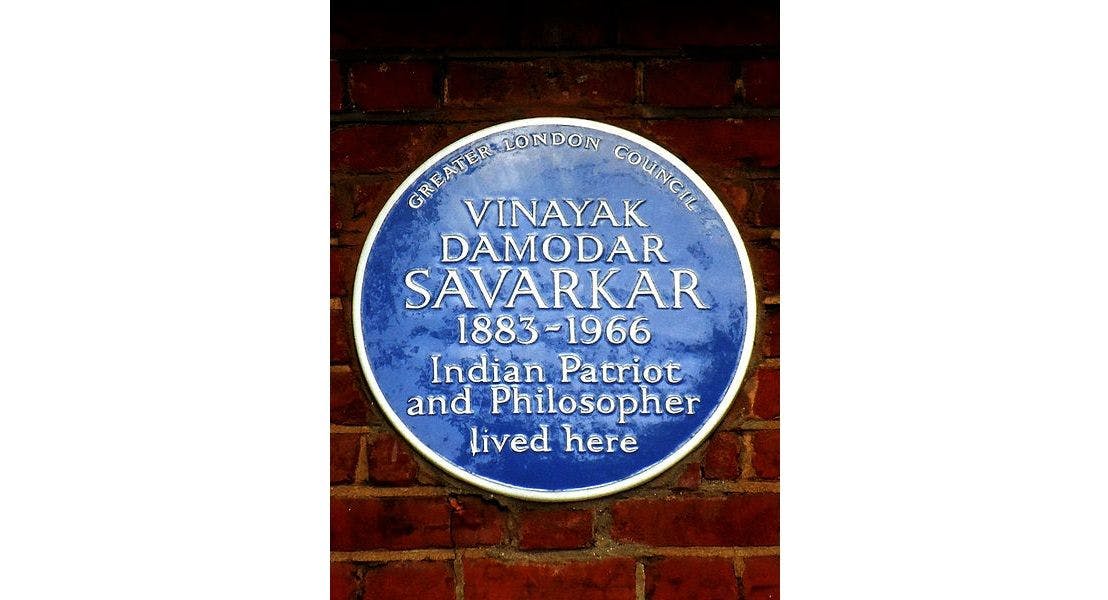

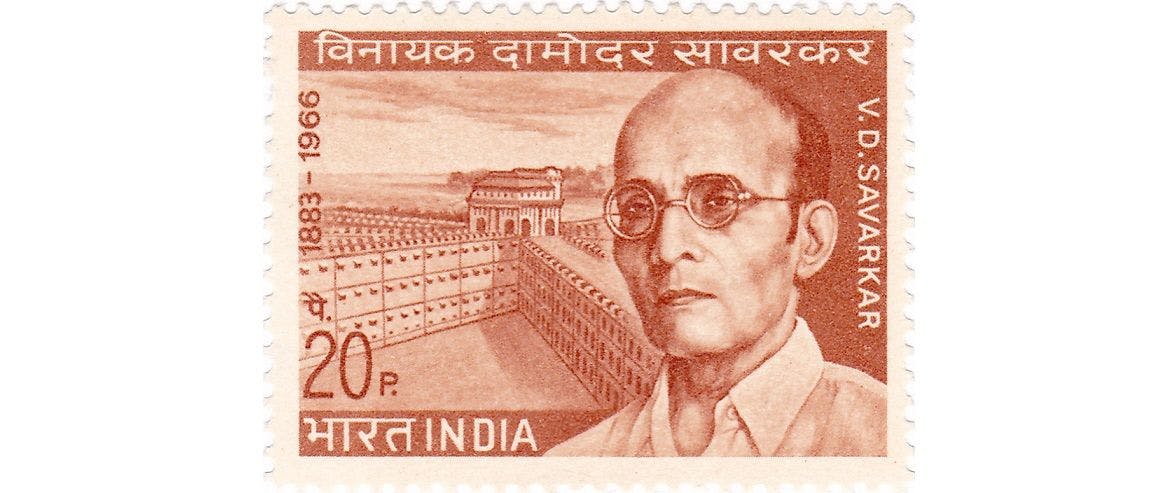

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

Veer Savarkar

3 July 1906 - 1 July 1910

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was born in 1883 in Bhagur village to father Damodarpant and mother Radhabai; he had two brothers, Ganesh and Narayan, and a sister, Mainabai. He was educated at the local Shivaji High School before he enrolled in the Ferguson College, Poona, in 1902. Here he involved himself in Indian nationalist politics before being expelled from college for his activities. He was permitted to take his BA degree and with the help of Shyamaji Krishnavarma attained a scholarship to study law at Gray's Inn in London.

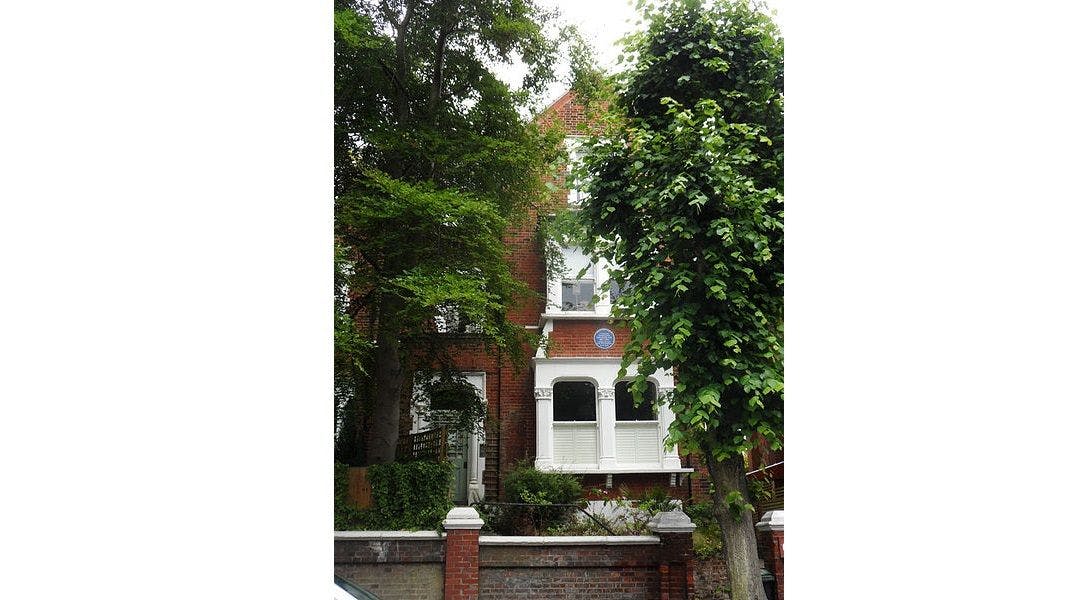

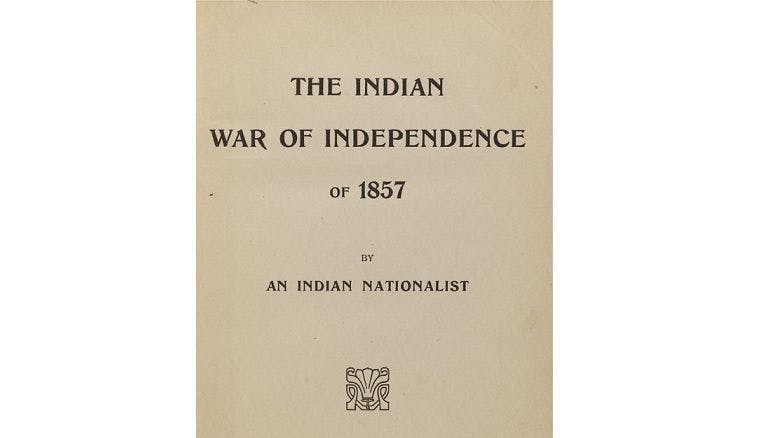

He embarked for London on 9 June 1906 and arrived in London on 3 July where he immediately found lodging at India House in Highgate. He became a protege of the founder of India House, Shyamaji Krishnavarma . Savarkar soon founded the Free India Society, based on the thoughts of the Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini (Savarkar had written a biography of Mazzini). The Society held regular meetings every Sunday where they celebrated Indian festivals and patriots, discussed Indian political problems, and how to overthrow the yoke of the British in India. Savarkar also sent bomb manuals off to India. Savarkar advocated a war for independence and in 1909 his work The Indian War of Independence was published, but it was immediately banned by the British government. The militancy of Savarkar left him and Gandhi at odds when Gandhi visited the House in October 1906.

In early May 1907, Savarkar organized the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 at Tilak House, 78 Goldsmith Avenue, Acton, London. Students wore badges with the legend 'Honour to the Martyrs of 1857'. Skirmishes broke out and the press blamed Krishnavarma who subsequently left London for Paris and left management of the House to Savarkar. Savarkar aligned the cause of Indian independence with the Irish and other overseas freedom movements andnotably met V. I. Lenin.

On 1 July 1909, on the steps of the Imperial Institute in London, Sir William Curzon Wyllie was shot by Madan Lal Dhingra ; Captain Cawas Lalkaka tried to defend Curzon-Wyllie and was also shot. Savarkar was not present but had according to some sources provided Dhingra with the revolver (Srivastava, p. 151). While most of the Indian community condemned Dhingra's action, Savarkar applauded it. Dhingra was sentenced to death. After the assassination, life became more difficult for Savarkar in London and he finally left London for Paris in early January 1910. Meanwhile, a warrant was issued for Savarkar's arrest in England. He returned to London on 13 March 1910 and was immediately sent to Brixton Jail. It was decided that he should stand trial in India, and on 1 July he embarked on the S.S. Morea . As the ship lay outside Marseilles, Savarkar escaped to French territory. The British tried to recapture him on French soil and the incident became a celebrated case in international law. He eventually arrived in Bombay on 22 July and was immediately taken to jail. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

He arrived in the Andaman Islands in July 1911 where he stayed until 1921, when he was moved to Ratnagiri, Bombay Presidency, where he was imprisoned until 1924 and interned until 1937. During his imprisonment, he wrote Hindutva: What is a Hindu? . After 1937, Savarkar continued his anti-Muslim, anti-British politics and became the ideological alternative to Gandhi's non-violence politics, as President of the right-wing Hindu Mahasabha. He remained a huge political influence until his death in Bombay in 1966.

Mirza Abbas (India House), M. P. T. Acharya (India House), Asaf Ali , Senapati Bapat (Pandurang Mahadev) (India House), Subramanya Bharati, Bhikaiji Rustom Cama , Virendranath Chattopadhyaya , Hemchandra Das, Sukhsagar Datta (Dutt) (shared a flat in Red Lion Passage), Madan Lal Dhingra , Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , David Garnett , Komre Gavarkar, Campbell Green (a correspondent for the Sunday Chronicle ; met Savarkar at India House), Shyamaji Krishnavarma , Lala Hardayal , Sikandar Hayat (visited Savarkar in jail), B. P. S. Iyer, J. C. Mukharji (India House), I. G. Mukherji, Niranjan Pal , Bhai Parmanand (India House), W. P. Phadke, T. S. Rajan, Sardar Singh Rana (India House), Harnam Singh (met on the Persia going to London), M. P. Sinha, K. V. R Swami, Gyanchand Varma (India House), Hotilal Varma, Sir William Hutt Curzon Wyllie (met at the India Office)

The Indian War of Independence of 1857 (London: [S.I.], 1909)

Who Is a Hindu?, 4th edn (Poona: S. P. Gokhale, 1949) [1923]

An Echo From Andamans (Bombay: V. V. Kelkar, 1924)

Hindu-Pad-Padashahi; or, a Review of the Hindu Empire of Maharashta (Madras: B. G. Paul & Co., 1925)

Presidential Speech (Lahore: Central Hindu Yuvak Sabha, 1938)

Hindu Sanghatan: Its Ideology and Immediate Programme (Bombay: N. V. Damle, 1940)

Presidential Address at the 23rd Session of the Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha, Bhagalpur, 1941 A.D. (Poona: Maharashtra Provincial Hindusabha Office, 1942)

Hindu Rashtra Darshan: A Collection of the Presidential Speeches Delivered from the Hindu Mahasabha Platform (Bombay: L. G. Khare, 1949)

The Story of my Transportation for Life (Bombay: Sadbhakti Publications, 1950) [1927]

Samagra Savarkar Wangmaya , 6 vols (1963–4) [collected works, vols. 1–4 in Marathi, 5–6 in Eng.]

Historic Statements , ed. by G. M. Joshi (Bombay Popular Prakashan, 1967)

Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History [by] Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, trans. and ed. by S. T. Godbole, 1st edn (Bombay: Bal Savarkar; New Delhi: Rajdhani Granthagar, 1971)

Savarakara Samagra (Dilli: Prabhata Prakasana, 2000-)

Anand, Vidyasagar, Savarkar: A Study in the Evolution of Indian Nationalism (London: Woolf, 1967)

Bakshi, S. R., V. D. Savarkar (New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 1993)

Chaudhary, S. K., Great Political Thinker: Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (New Delhi: Sonali Publications, 2008)

Chitragupta, Life of Barrister Savarkar (Madras: B. G. Paul & Co., 1926)

Deshpande, Sudhakar, Savarkar: The Prophetic Voice (Pune: Dastane Ramchandra & Co, 1999)

Fryer, Peter, Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain (London: Pluto, 1984)

Garnett, David, The Golden Echo (London: Chatto & Windus, 1953)

Godbole, V. S., Rationalism of Veer Savarkar (Thane, India: Itihas Patrika Prakashan, 2004)

Gosain, Saligram, Stormy Savarkar: The Revolutionary Who Jumped the Ship (Delhi: Vijay Goel, 2005)

Islam, Shamsul, Savarkar: Myths and Facts (Delhi: Media House, 2004)

Keer, Dhananjay, Savarkar and His Times (Bombay: A. V. Keer, 1950)

Longuet, Jean, Mémoire Présenté à la Cour d'Arbitrage de La Haye au nom de M. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar par Me J. Longuet (Paris, 1911)

Misra, Amalendu, Identity and Religion: Foundations of Anti-Islamism in India (New Delhi; London: Sage Publications, 2004)

Noorani, Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed, Savarkar and Hindutva: The Godse Connection (New Delhi: LeftWord Books, 2002)

Sarkar, Sumit, ' Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar (1883–1966)' , Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004) [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/47751]

Singh, K. Jagjit, Savarkar Commemoration Volume (Bombay: Savarkar Darshan Pratishthan, 1989)

Srivastava, Harindra , Five Stormy Years: Savarkar in London (June 1906-June 1911) (New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1983)

Srivastava, Harinda, 'The Epic Sweep of V. D. Savarkar : An Analytical Study of the Epic Sweep in the Life and Literature of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar' (PhD Thesis - Nagpur University, 1989., Savarkar Punruththan Sansthan, 1993)

Trehan, Jyoti, Veer Savarkar: Thought and Action of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications, 1991)

Vaidya, Prem, Savarkar: A Lifelong Crusader (New Delhi: New Age International (P) Ltd, 1996)

Visram, Rozina, Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History (London: Pluto, 2002)

Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi

ELECTION DAY OFFER: Subscribe For Just ₹̶2̶9̶9̶9̶ ₹699

Savarkar: The Unsung Poet

Vikrant Pande

Mar 19, 2015, 12:30 PM | Updated Feb 11, 2016, 08:51 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app .

Outside Maharashtra and Marathi-speaking people, the revolutionary got little or no recognition either in the form of state honours or in society’s appreciation of his literary talent.

Most Indians know Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, popularly known as Veer Savarkar, as a freedom fighter who is often demonized for his supposed involvement in the assassination of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi . The Indian government after independence deliberately ignored him and did not honour him as should have been his due. As an American author said, “Sometimes your light shines so bright that it blinds people from seeing who you really are.”

It is unfortunate that very few knew that Savarkar was a poet, novelist, writer of short stories, playwright, historian and a champion of ‘purification’ of language. Savarkar’s poetry is a lasting legacy, which is known to almost each Maharashtrian. As Allen Ginsberg says, “Poetry is not an expression of the party line. It’s that time of night, lying in bed, thinking what you really think, making the private world public, that’s what the poet does.” And that is what makes Savarkar’s poems so timeless; they speak the language of the heart.

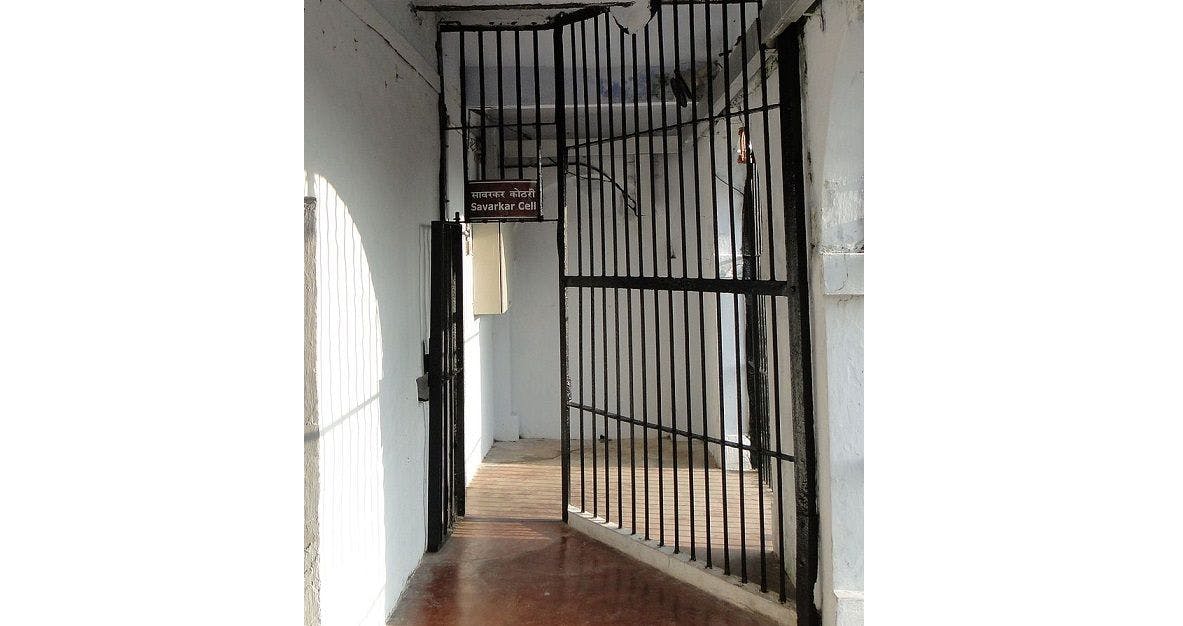

Savarkar composed his first poem “Swadeshichaphatka” at the tender age of 11 and continued writing in school and as a student in London. Some of his best works were written when he was in the Cellular Jail at the Andamans. The torture and the treatment meted out to the political prisoners – there is a story for some other day. The cruel jailor David Barry’s actions would make one wonder how someone could have conceived such ingenious ways of torture.

Savarkar wrote many books like Joseph Mazini (biography of an Italian revolutionary), 1857 Che Swantantra Samar (the first Independence struggle of India of 1857), Shikhancha Itihas (History of the Sikhs), Mazi Janmathep (a narration of his jail term in the Andamans), Sanyast Khadga (a play), Kale Pani (Black Water), Mala Kay Tyache (What is it to me), Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? and Gomantak . Savarkar’s three plays Usshaap , Sanyastakhadga and Uttarkriya are notable for their dialogues and dramatic content.

Savarkar wrote three books on history: The Indian War of Independence 1857 , Hindupadpaadshaahi and Six Glorious Epochs . These books reveal his deep study of, and insight into, history, penchant for detail and inspirational but well-researched content.

Savarkar has many firsts to his credit, as far as Marathi literature goes. He was the first to compose powada s (ballads) in modern times and was the first to use modern imagery in the powada s. He was the first Marathi journalist to contribute newsletters to Marathi periodicals Londonchi baatmipatre (Newsletters from London) from foreign countries. His taarakaaspahun (gazing at the stars) is the first Marathi poem composed outside Indian shores. His Joseph Mazzini is the first Marathi book written outside India.

One of Savarkar’s songs, known to almost all Maharashtrians, is “Saagarapraantalamala” (My heart is tormented, O Ocean), written after his close associate Madan Lal Dhingra was sent to the gallows in London. The British police were keenly shadowing Savarkar, aware of his friendship with Dhingra. Dhingra’s martyrdom and the subsequent repression by British authorities took its toll on Savarkar’s health. He went to Brighton, around 50 miles south of London, to recuperate his health and remained there for 10-12 days. His associate Niranjan Pal would visit him to give him moral support. The two would frequently walk on the shores of Brighton.

On one such occasion, both of them were sitting on the seashore surrounded by dozens of mirthful English men and women. In the midst of this mirth, Savarkar was immensely sad. Sitting in front of the vast ocean, his mind was grieving at the thought of his beloved motherland. Pal described that momentous occasion 29 years later in an article, “Reminiscences of Savarkar,” dated 27 May 1938 in The Mahratta , Pune. Pal wrote, “Presently, he (Savarkar) commenced to hum a song. He sang as he composed. It was a Marathi song, describing the pitiable serfdom of India. Forgetful of all else, Savarkar went on singing. Presently, tears began to roll down his cheeks. His voice became choked. The song remained unfinished; Savarkar began to weep like a child.”

The song, immortalised by Hridaynath Mangeshkar’s lovely music and sung by the entire Mangeshkar family (Lata, Asha, Usha, Meena and Hridaynath) , turns the listener emotional every time.

Dennis Gabor, Nobel Laureate and scientist, said, “Poetry is plucking at the heartstrings and making music with them.” Savarkar’s poetry, coming from the depths of his tormented soul, purified by the fire of patriotism, and tortured in the cells of Cellular Jail, had no option but to touch anyone who reads it even today, decades after the events have passed. It is the sheer intensity of the words that wouldn’t allow one to hum them without being affected.

Here are a few stanzas from “Saagara”:

नेमजसीनेपरतमातृभूमीला। सागरा, प्राणतळमळला भूमातेच्याचरणतलातुजधूतां। मीनित्यपाहिलाहोता मजवदलासीअन्यदेशिं चलजाऊं। सृष्टिचीविविधतापाहूं तइंजननी-हृद् विरहशंकितहिझालें। परितुवां वचनतिजदिधलें मार्गज्ञस्वयें मीचपृष्ठिं वाहीन। त्वरितयापरतआणीन विश्वसलों यातववचनीं। मी जगदनुभव-योगें बनुनी। मी तवअधिकशक्त उध्दरणीं। मी येईन त्वरेंकथुन सोडिलें तिजला। सागरा, प्राणतळमळला शुकपंजरिं वाहरिणशिरावापाशीं। हीफसगतझालीतैशी भूविरहकसासततसाहुं यापुढती। दशदिशातमोमयहोती गुण-सुमनेंमीं वेचियलीं ह्याभावें। कीं तिनें सुगंधाध्यावें जरि उध्दरणीं व्ययनतिच्या हो साचा। हाव्यर्थ भारविद्येचा सागरा, प्राणतळमळला O Ocean, take me back to my motherland; My soul is tormented. I had always seen you, Washing the feet of my motherland. You led me to a different country, To experience the diversity of nature there. Knowing that my mother’s heart was full of anguish, You promised her that you would take me back; I was reassured. I believed that my experience of the world, Would help me to serve her better. Saying that I would return soon, I took leave of her. Oh, Ocean, I am now pining for my motherland Like a doe caught in a snare, The promise you made was deceptive! I cannot suffer the separation anymore, Darkness envelops me everywhere. I had accumulated flowers of virtues, In the hope that my mother will be rendered fragrant with their smell. What use, this burden of knowledge and virtues If my mother cannot prosper from it? I miss the love of the mango tree, the flowers in my garden back home the blossoming creepers and the blooming rose… I feel desolate… Oh Ocean, I am pining for her… Take me back to my motherland Oh Ocean, I am pining for her…

In Cellular Jail, Savarkar wrote another poem “Jayostute” (Victory to you!), which too has been made popular by Hridaynath’s music . The song is a sort of ‘national song’ in Marathi, similar to Vande Mataram. The listener is bound to have his hairs stand on end as the beats and the words propels one to get enveloped in its beauty.

Savarkar sings paeans to the goddess of freedom.

ज्योस्तु तेश्रीमहन्मंगले। शिवास्पदे शुभदे स्वतंत्रते भगवति। त्वामहं यशोयुतां वंदे राष्ट्राचेचैतन्य मूर्त तूं नीतिसंपदांची स्वतंत्रते भगवति। श्रीमतीराज्ञीतूत्यांची परवशतेच्यानभांत तूंचीआकाशीहोशी स्वतंत्रते भगवती। चांदणी चमचम लखलखशी।। गालावरच्याकुसुमीकिंवाकुसुमांच्यागाली स्वतंत्रते भगवती। तूचजीविलसतसे लाली तूं सूर्याचेतेजउदधिचेगांभीर्यहि तूंची स्वतंत्रते भगवती। अन्यथा ग्रहण नष्ट तेंची।। मोक्ष मुक्तिहीतुझीच रूपें तुलाच वेदांती स्वतंत्रते भगवतीIयोगिजनपरब्रह्म वदती जेजेउत्तमउदात्तउन्नतमहन्मधुर तेंतें स्वतंत्रते भगवती। सर्व तवसहचारी होते।। हे अधम रक्त रंजिते। सुजन-पुजिते! श्रीस्वतंत्रते तुजसाठिं मरण तें जनन तुजविणजननतेमरण तुजसकलचराचरशरण स्वतंत्रते भगवतीIत्वामहं यशोयुतांवंदे।। Victory to you, O Auspicious One, the Munificent and Holy! O Goddess of Freedom, I seek you blessings for success You are the embodiment of our national spirit, our morality and our accomplishments O glorious Goddess of Freedom, you are the Queen of righteousness In the dark skies of enslavement O Goddess of Freedom, you are the shining star of hope. Whether on flowers as soft as cheeks, or on cheeks as soft as flowers! O Goddess of Freedom, You are that blush of confidence! You are the radiance of the Sun, the majesty of the Ocean O Goddess of Freedom, but for you the Sun of Freedom is eclipsed. O Goddess of Freedom, you are the face of eternal happiness and liberation, That is why the scriptures hail you as the supreme soul. All that is ideal, magnificent and sweet, O Goddess of Freedom, is associated with you You are the destroyer of evil (stained with their blood), O Goddess of Freedom Life is to die for you, Death is to live without you. All creation surrenders unto you! Victory to you, O Auspicious One, the Munificent and Holy! O Goddess of Freedom, I seek you blessings for success

A stanza of another poem written by Savarkar:

मलादेवाचेदर्शनघेउद्या डोळेभरूनदेवासमलापाहुंद्या जोतुम्हिचकरादिनरात मळकाढितमळलेहात म्हणुनीचविमल हृदयात— हृदय त्यावाहुद्या! Let me see my God in his temple Let my eyes have their fill of Him My hands have been defiled Cleaning filth day and night To cleanse them in the pure heart Allow me; I pray On his deathbed, Savarkar welcomes death saying येमृत्यो! येतूंये, यावयाप्रती निघालाचि असशिलजरि येतरीसुखें! कोमेजुनिजावयाभिवोतहींफुलें हींद्राक्षेंरसरशींतसुकुनिजावया भ्यावेंतेंकाम्हणुनीतुजसिपरी मी? Come, Death, come! Having set forth To get me, come gladly Let these flowers fear to wither and die, Let these juicy grapes dread to shrivel and die, But me! Why pray should I fear you?

It is a sad reality that India today has forgotten Veer Savarkar. It is time we honoured his contribution. But whether the government does anything or not, his lasting legacy in form of some of his poems will continue to touch and inspire generations to come.

A graduate of IIM Bangalore, Vikrant Pande’s day job is spearheading the TeamLease Skills University at Baroda. His keen desire to see his favourite Marathi books being read by a larger audience saw him translate Raja Ravi Varma by Ranjit Desai (Harper Perennial). He has since translated Shala by Milind Bokil, and is currently working on several other books. He is fluent in many languages including Marathi, Gujarati, Bangla, and a smattering of Tamil and Kannada.

- columns: Baasha

Join our WhatsApp channel - no spam, only sharp analysis

Introducing ElectionsHQ + 50 Ground Reports Project

The 2024 elections might seem easy to guess, but there are some important questions that shouldn't be missed.

Do freebies still sway voters? Do people prioritise infrastructure when voting? How will Punjab vote?

The answers to these questions provide great insights into where we, as a country, are headed in the years to come.

Swarajya is starting a project with an aim to do 50 solid ground stories and a smart commentary service on WhatsApp, a one-of-a-kind. We'd love your support during this election season.

Click below to contribute.

Get Swarajya in your inbox.

PM Modi Dashboard: "Every Vote Counts And Every Voice Matters", PM Urges Indians To Vote In Large Numbers

Historian irfan habib says 'marathas gave aligarh its name'- maratha history researcher says 'not true', maharashtra politics is caught in the ‘sage-soyre’ trap, neta families reluctant to make way for political greenhorns.

Global South Faces Trade Disruption: Green Industrial Policies Of Major Economies Raise Alarms

How pm modi's approach to policy differs from that of the upa government — economist shamika ravi explains, 'they made careers out of sounding alarm on rising inequality but failed to do anything about it,' arvind panagariya on inequality labs report, infrastructure, explained: government's aggressive debt reduction plan for nhai, to fast-track india's highway growth, after inaugural high-speed route, india working on home-built bullet train, ramkrishna forgings secures rs 270 crore order for vande bharat sleeper trains, bpcl to build 34 km atf pipeline for seamless fuel delivery to noida international airport.

DRDO Is Planning To Test Astra Mk-2 Missile; Here's A Lowdown On The New 130 KM Range Air-To-Air Missile

India's indigenous technology cruise missile demonstrates sea skimming capability, indian air force is slowly but surely upgrading its air bases to meet the china challenge.

Why Japan's New Aircraft Carriers Must Be Taken Seriously

With china in mind, europe revives magnesium mining after decade-long hiatus, chile plans to set up first mega sustainable aviation fuel factory, to decarbonise airline industry.

Where 22 January 2024 Stands In Global History

Ramlalla will be adorned with a surya tilak at the same time every ram navmi - here's how it will work, “they’ll 'talk' about music”.

Bengaluru Suburban Rail: SWR Transfers 115 Acre Land For Kanaka Corridor, Commits To Approve Airport Line Alignment

From olive green to shades of saffron — dakshina kannada bjp candidate capt brijesh chowta on his vision for karnataka's coast, karnataka: 'winnability' is an excuse, congress fielding kin of ministers, mlas because no good candidates would bet on it.

Mysore Maharaja In, Pratap Simha Out — Why The BJP May Have Arrived At This Decision

What to expect from bjp's karnataka list — key issues, possible candidates, likely outcome, bengaluru cafe blast: karnataka home minister suspects intention to deter investors, bjp says congress hiding facts.

- THE WEEK TV

- ENTERTAINMENT

- WEB STORIES

- JOBS & CAREER

- Home Home -->

- The Week The Week -->

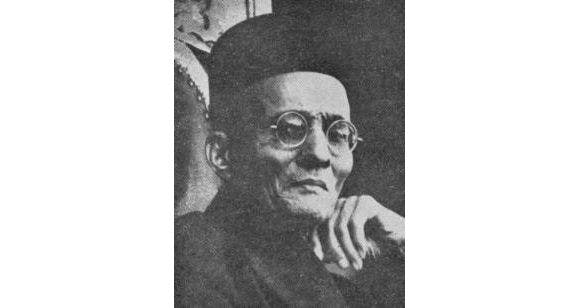

India@75: The real Savarkar

A dispassionate look at the life and philosophy of a fiery freedom fighter

The legacy of a man as contested and polarising as Swatantryaveer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar becomes an issue of contemporary politicking and raucous debate. In all this melee the real picture of the man, his life and philosophy get sadly obliterated, as I was to discover in my five-year-long journey into understanding the many complexities of his character.

As a young man, hailing from Nasik in Maharashtra, Savarkar took to revolutionary thoughts early in life, being influenced by the Italian revolutionaries Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Barely in his teens and being deeply moved by the execution of the chivalrous Chaphekar brothers of Poona who had assassinated oppressive British officials, Savarkar established India’s first secret society—the Mitra Mela, which later became Abhinav Bharat—and facilitated a fantastic network of revolutionaries across India. Under the leadership of Tilak, he organised the first-ever bonfire of foreign clothes as a student in Poona’s Fergusson College in 1905, protesting against the Partition of Bengal. He was fined and rusticated from college hostel for this.

Later, on Tilak’s recommendation Savarkar moved to London on a scholarship awarded by Shyamji Krishna Varma, ostensibly to study law at the Gray’s Inn. But while in London, he became the nucleus of a vast intercontinental, anti-colonial armed struggle to free India. From India to Europe, and even America, a network of brave-hearts guided by him made contacts with Irish, French, Italian, Russian and American leaders, revolutionaries and the press to bring British India and the misery of Indians to the forefront of global discourse. No doubt, the British Government categorised him as one of the most dangerous seditionists. Along with luminaries such as Madame Bhikaji Cama, Sardarsinh Rana, Madan Lal Dhingra, V.V.S. Aiyar, Niranjan Pal, Virendranath Chattopadhyay, Lala Hardayal and M.P.T. Acharya and others, Savarkar spearheaded numerous revolutionary acts ranging from procurement and smuggling to India of bombs, pistols and bomb manuals to orchestrating political assassinations of the British both in India and in the heart of the Empire—London.

Parallelly, Savarkar created a vast intellectual corpus for the revolutionary movement by penning the biography of Mazzini and a well-researched, definitive magnum opus on the 1857 uprising. Terming it ‘The First War of Indian Independence’, he sought to elevate the importance of an event, hitherto disparaged as being a mere Sepoy Mutiny. This book was to serve as an inspiration for revolutionaries decades after it was written—from Bhagat Singh to Rash Behari Bose and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and his INA.

The British were determined to extradite Savarkar to India at all costs. Slapping an unfair Fugitive and Offenders Act (FOA) of 1881, he was deported to India and tried with no right to appeal or defence. He was sentenced to two life-imprisonments totalling 50 years and packed off to rot in the Cellular Jail of the Andamans, where he suffered the worst punishments. Fettered in chains, flogged, condemned to six months of solitary confinement, made to extract oil all day being tied to the mill like a bullock, punished with standing handcuffs for days on end, denied the most basic human needs of toilets or water and fed with foul food that had pieces of insects and reptiles—horrific Kala Pani was indeed the Indian Bastille.

The bogey of the clemency that he sought while at the Andamans is often invoked to discredit him. But these petitions were a normal route available to several political prisoners (including important revolutionaries such as Barin Ghosh, Nand Gopal, Hrishikesh Kanjilal, Sudhir Kumar Sarkar or Sachindra Nath Sanyal who availed the same). Savarkar was also acting as a spokesperson for other prisoners in his petitions where he seeks a general amnesty for all, especially after the First World War and demands clarification of the position and relief that a political prisoner could legally claim. For instance, in his 1917 petition he states: “If the Government thinks that it is only to effect my own release that I pen this; or if my name constitutes the chief obstacle in the granting of such an amnesty; then let the Government omit my name in their amnesty and release all the rest; that would give me as great a satisfaction as my own release would do.”

British Home Department officials like Sir Reginald Craddock who interviewed Savarkar opined that the latter “cannot be said to express any regret or repentance”for whatever he did. “So important a leader is he,”Craddock noted, “that the European section of the Indian anarchists would plot for his escape which would before long be organized. If he were allowed outside the Cellular Jail in the Andamans, his escape would be certain. His friends could easily charter a steamer to lie off one of the islands and a little money distributed locally would do the rest.” The Government obviously rejected his petitions and nothing changed for Savarkar.

Sachindra Nath Sanyal in his memoirs reveals sending identical petitions as Savarkar and being released while Savarkar and his elder brother Babarao were still imprisoned since the Government feared that their release would rekindle the fizzled revolutionary movement in Maharashtra. Moreover, the entire issue of petitions was not some new discovery made in recent times, as is made out to be. Savarkar was not the first, nor the last, to file petitions. Also, he had mentioned these candidly in his own prison memoirs ‘My Transportation for Life’ and his letters to his younger brother Narayan Rao.

From his prison confines Savarkar had watched with horror the dangerous fire that Gandhi was stoking by linking religion with politics through his Khilafat agitation and yoking it to Indian freedom. By promising support to Indian Muslims to re-establish a pan-Islamist Caliphate in Turkey that the British had won in the First World War, Gandhi had sought to receive Muslim support for the non-cooperation movement. But this agitation was doomed to failure as the British were not obliged to listen to the demands of their colonies. The inevitable failure of the movement resulted in widespread clashes across India all through the 1920s—the Moplah incident in Malabar, Gulbarga, Kohat, Delhi, Panipat, Calcutta, East Bengal and Sindh to name a few. Each time, Gandhi’s lukewarm response and the pusillanimity of the Congress angered Savarkar. In this backdrop Savarkar wrote his treatise on Hindutva in 1923, as a direct response to Gandhism and Khilafat. He called for unifying Hindu society and challenged trans-national loyalties through his definition of India’s sacred geography and territorial integrity. Anyone who considered this land as the land of his ancestors and their holy land (including Muslims and Christians) was a ‘Hindu’—not by its religious term, but as a cultural marker of shared common history and bloodline. From then on, Savarkar fashioned himself as the champion for the cause of the Hindu community, though he did not care much for the ritualistic aspects of the religion itself, being an agnostic and rationalist.

From 1924 to 1937, Savarkar engaged himself in massive social reforms in Ratnagiri where he was kept in conditional confinement after being released from prison. He strove hard for unity in the Hindu society advocating a complete eradication of the caste system, varna tradition and untouchability, and championed inter-caste dining, inter-caste and inter-regional marriages, widow remarriage, female education and temple entry for all castes. His views were more in sync with those of Ambedkar than with Gandhi’s on matters of caste. Savarkar’s degrees were snatched away from him; his property confiscated. Like a few other revolutionaries in Bengal who were given a sustenance income, the Government gave him a pension of Rs60 per month between 1929 and 1937 as he had no source of livelihood.

In 1937, after being released, he took over as the president of the hitherto decrepit All-India Hindu Mahasabha. On the one hand he countered the Congress’s abject appeasement policy and on the other the divisive politics of Jinnah and the Muslim League. His party was the one that opposed the partition of India till the very end. The Constitution of free India, according to Savarkar, was to be one where equal rights and obligations were conferred on all people irrespective of caste, creed, race and religion. “We want to relieve our non-Hindu countrymen,” said Savarkar, “of even a ghost of suspicion that legitimate rights of minorities with regard to their culture, religion and language will be expressly guaranteed.” Quite erroneously he is often described as the progenitor of the dubious Two-nation theory, which actually went back to the 1880s and the times of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. Savarkar opposed the militant groups within the Muslim community and alluded that, given the imagination of a pan-Islamic ummah under a common Caliph, many Muslims did think of themselves as being a separate entity. But he for one opposed the creation of Pakistan or a nation within a nation on religious terms.

Like several other leaders of the time, from Maulana Azad to Ambedkar, who were opposed to the Quit India Movement being launched with no clear plan of action and at a time when the Japanese were threatening to invade India at the height of the Second World War, Savarkar too disapproved of it. He instead encouraged youths to enlist in the British Army, get trained and then defect to Netaji’s INA. That was more likely to win India her freedom, he believed, than jail-filling agitations. The Mahasabha also formed coalition governments with non-Muslim League Muslim parties such as the Krishak Praja Party in Bengal and the Unionist Party in Sindh to split Muslim public space. A brief alliance with the League in government went awry. Of course, in these crucial years leading to partition and freedom, the failure of Savarkar as a leader also comes through; as someone who could not even control the warring factions within his own party or present a cogent alternative to the Congress.

Shortly after freedom, Savarkar was arrested on the suspicion of being complicit in Gandhi’s murder since the main assassins Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte had been his acolytes in the Hindu Mahasabha earlier. He was arrested and the Red Fort Trials went on in Delhi for over a year. In his testimony in court Godse, however, said: “It is not true that Veer Savarkar had any knowledge of my activities which ultimately led me to fire shots at Gandhiji.” Godse, in fact, spoke about being disillusioned with Savarkar’s pacifism after 1945 and that he decided to break away from him. The edifice of the prosecution’s case stood on the statements of the police approver Digambar Badge’s claims that he, along with Godse and Apte, had visited Savarkar, who wished them success in the conspiracy. The police also got coercive statements from Savarkar’s secretary Gajanan Damle and bodyguard Appa Kasar as being witnesses to this meeting. Curiously, Damle and Kasar were not even brought to court by the prosecution despite their statements being the supposed clincher of Savarkar’s crime. Justice Atma Charan eventually exonerated Savarkar of all charges and interestingly, Nehru’s Government did not appeal against the acquittal.

The Jeevan Lal Kapoor Commission, which was set up closer to the time of Savarkar’s death in 1966, chose to unilaterally blame him for Gandhi’s murder without, once again, calling upon Damle and Kasar to testify among its 101 witnesses. From maintaining all through that a Savarkarite faction within the Mahasabha had committed the murder, it jumped to the abrupt conclusion that Savarkar was responsible for it without any corroborative evidence.

And it is this contentious legacy of Savarkar that gets dragged into contemporary political feuds and toxic electoral discourse. Whether or not to give him a Bharat Ratna posthumously raises huge hackles. On his death in 1966, the then prime minister Indira Gandhi praised him by stating that “his name was a by-word for daring and patriotism” and that “he was cast in the mould of a classic revolutionary.” She got a stamp issued in his name, a film made on his life and her private money donated to a memorial. The question that today’s Congress needs to answer is why their tallest leader would be endorsing a man whom they love to call a British stooge, coward, Islamophobe and Gandhi’s assassin. The sooner we extricate characters of the past from the hurly-burly of today’s politics, the better justice would be meted out to history.

Dr Vikram Sampath is a historian, author of a two-volume biography of Savarkar—Echoes from a Forgotten Past & A Contested Legacy—and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, UK.

- Freedom Series

- Latest Posts

- LSE Authors

- Choose a Book for Review

- Submit a Book for Review

- Bookshop Guides

Surajkumar Thube

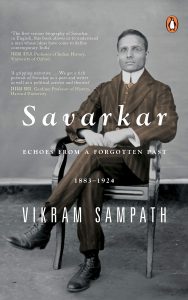

July 22nd, 2020, book review: savarkar: echoes from a forgotten past, 1883-1924 by vikram sampath.

4 comments | 24 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

In Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883-1924 , Vikram Sampath offers the first volume in a new two-part comprehensive biography of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who played a key role in the development of Hindu nationalism. While the book offers detailed biographical information and makes use of Savarkar’s writings, the lack of critical analysis of Savarkar’s intellectual thought makes it far from a definitive account of this influential figure, writes Surajkumar Thube .

Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883-1924 . Vikram Sampath. Penguin India. 2019.

Decoding Savarkar: Documentation Minus Analysis

Savarkar is widely considered as the most influential figure in the history of Hindu nationalism. His book Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? (1923) was the first comprehensive text that detailed the idea of ‘Hindutva’ (Hinduness) which became the key marker of the Hindu nationalist ideology. His emphasis on ‘Hindu unity’, equating Indian culture with the values of ‘Hindu civilization’, and his vision of a Hindu Rashtra that belonged only to those who treated India as their ‘Fatherland’ and ‘Holyland’ (thereby excluding Muslims and Christians and treating them as alien communities), were some of the core principles laid out in this book.

Largely remembered as the father of Hindu nationalism, Savarkar’s thoughts continue to influence Indians across generations. That said, it is a matter of intrigue that there has been no comprehensive biography of Savarkar in the English language up until now. Vikram Sampath attempts to fill this void in two volumes, with the first book, Savarkar: Echoes From a Forgotten Past , documenting the life events of Savarkar between 1883 and 1924. The book provides a detailed description of Savarkar’s early childhood days, his life as a law student in London where he helped Indian revolutionaries opposing British colonialism learn methods of assassination, his reading of the Indian Mutiny of 1857 as the ‘First War of Indian Independence’ and his daily struggles behind bars when he was transported to the British prison on the Andaman Islands for his alleged complicity in the killing of a British district magistrate.

The word ‘documenting’ is crucial here. The author’s goal is certainly to write a detailed two-part biography. However, as noted in the synopsis, he also aims to unearth certain aspects of Savarkar’s life which he believes have prevented ‘truth from coming to light’. He goes on to pose the question of ‘what was it that transformed Savarkar in the cellular jail to a proponent of Hindutva?’ His goal is therefore not only to chronicle Savarkar’s life events, but to make an argument for why his political thought evolved in a particular manner and to ‘put his life and philosophy in a new perspective’. However, the book largely focuses on showcasing anecdotal information and some rare public participation records rather than providing a critical analysis of Savarkar’s theoretical oeuvre. The author’s quest to include detailed information on every aspect of his life thereby becomes a limited attempt at convincing the reader that Savarkar must not be singularly maligned for his majoritarian impulse. ‘Truth’, we are told, ‘lies in between’.

Instead of focusing on all the details of Savarkar’s life in this period, I would like to highlight a few observations made by the author which fail to provide critical insight into Savarkar’s thoughts and deeds or make more persuasive and nuanced arguments. Sampath begins his introductory narrative by arguing Savarkar viewed Muslims with mere ‘suspicion’ (rather than derision and contempt), vowing to take up this narrative later in the text. Savarkar’s public projection of himself as a crusader against untouchability and his strong disbelief in everyday Hindu rituals are understood as opposition to the caste system. The possibility of such a strategic move directly helping Savarkar consolidate his idea of Hindutva by visualising all Hindus as one political entity is overlooked. This, alongside the fundamental point that being against casteism does not necessarily mean being against orthodoxy or the varna system, is not deemed significant enough for exploration. Sampath’s reference to Savarkar’s ‘alleged’ atheism is also left unexamined.

Furthermore, in order to underscore Savarkar’s ‘freedom fighter’ attributes of valour and militancy, these are juxtaposed with an oversimplified Gandhian idea of pacifism. Ironically, by deploying a term like ‘pacifism’ to explain Gandhi’s complex thought, Sampath’s documentation, which is presented as ‘self-evident’ in its meaning, robs the book of multiple possibilities for analysing Savarkar as well. This continues in the rest of the book as the detailing of life events comes at the cost of not providing enough critical substance.

We are introduced to Savarkar’s early days and how he found the caste system regressive since childhood. At the same time, we are also told that he started reading Vishnushastri Chiplunkar’s Nibandhamala among other works. Chiplunkar’s emergence marked the rise of a Marathi literary phase which had strong underpinnings of an upper-caste worldview packaged as ‘national consciousness’. There is no attempt to show how Nibandhamala’s position in history as a text that gave rise to a revivalist phase in the Marathi literary renaissance reconciles with Savarkar’s purported opposition to casteism.

Furthermore, we are made to wait until Savarkar is in his mid-twenties to explore how the concept of Hindutva developed. This abrupt introduction to what Hindutva actually entails belies the boasting of Savarkar’s precocious talents in the initial chapters. This raises the question of whether it is historically informed to accept that the basic tenets of Hindutva did not play any significant role in Savarkar’s childhood. Was there a sudden Hindutva epiphany moment in the early 1920s? What were Savarkar’s relations like with Muslims, lower castes and Dalits who may not have agreed with the growth trajectory of his intellectual thought from his childhood days?

These gaps become more pronounced when we are introduced to the readings that influenced Savarkar in his teenage years. Apart from a few local figures, Savarkar is said to have read Italian republicans Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi at the age of sixteen. He also read philosopher Herbert Spencer’s Liberal Utilitarianism and was inspired by English radical writer Thomas Frost’s book Secret Societies of the European Revolution, 1776-1876 (1876). While we do get introduced to these works, it is one thing to document Savarkar’s reading lists and quite another to dissect his comprehension methods and the development of his philosophy. For instance, what impact did reading a local rebel fighter like Vasudev Balwant Phadke, and at the same time reading a more global figure like Frost, have on Savarkar’s development of the arch of Hindutva? In this way, as information supersedes analysis, what ‘revolution’ actually meant for Savarkar eludes us. One example of this is how Sampath refers to secret societies in Ireland and Russia and their impact on Savarkar without unravelling this influence.

What substitutes for the anticipated laborious analysis is an extended graphic and emotional discussion of Savarkar’s sufferings in the notorious Andaman Jail. The jail chronicles effectively brush aside the hitherto dominant historiography (which includes works from scholars like A.G. Noorani, Jyotirmay Sharma, Vinayak Chaturvedi and many others) of how Savarkar capitulated in front of the British government. He first petitioned for release in 1911, following his attempted armed revolt against the Morley-Minto reforms (1909). He made additional petitions up until his final release from Ratnagiri jail in 1924, where he was transferred in 1921. In a bid to present Savarkar’s clemency petitions as an ingenious strategy to ensure his release from jail, the author does not address the conciliatory and timid tone of his petitions at a time when the notion of ‘sacrificing oneself for the nation’ was gaining momentum.

Despite Hindutva being written during Savarkar’s time in jail, Sampath’s focus largely remains on Savarkar’s hardships behind bars. This is only loosely accompanied by hollow comments on how ‘there was not a single book he left unread’ during this time. Again, there is no probing in terms of what transpired from Savarkar’s readings in terms of his eventual generation of thought. This is compounded further when a large section at the end of the book is a collection of essays written by Savarkar, including Savarkar’s views on the need to reform Hinduism, encouraging inter-caste marriages and dismissing cow worship as a superstition. While it is useful to provide these essays to English-language readers, we do not get any insight into Sampath’s views or his interpretation of these intellectual writings of Savarkar.

In the chapter titled ‘Who is a Hindu?’, Sampath alludes to the alienation and separatism among a vast section of Muslims in India as the context for the birth of Hindutva. By outsourcing the birth of Hindutva to ‘the suspicious’, Sampath clearly attempts to humanise Savarkar. Sampath gives examples to support this by showing how Muslims were wary of taking part in the activities of the Indian National Congress. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, a Muslim reformer of the nineteenth century, is declared as the first proponent of the Two-Nation theory. There is precious little in terms of engaging with Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s intellectual thought and how he was a vocal proponent of Hindu-Muslim unity. Furthermore, the Muslim League is said to have had actively vitiated communal harmony and the Moplah Rebellion in 1921 is described as a ‘fanatical outbreak’. As with the over-simplified portrayal of Sir Syed’s politics, the author’s discussion of the Hindu-Muslim riots that erupted in Malabar fails to provide background to how the rebellion was primarily waged against the feudal system and an ailing agrarian economy. It also fails to problematise the role of upper-caste Hindu landlords since the nineteenth century. Instead, Hindutva is ultimately projected as an ‘all-embracing philosophy’, as a phenomenon that focuses on building a unitary identity.

Sampath, in a paradoxical sense, retrieves ownership of Hindutva’s origins from Savarkar and puts the ‘Muslim context’ at the forefront. Savarkar’s case for building a strong, muscular Hindu society is primarily seen, almost always, as a reaction to Muslim aggression. This narrative, more than anything else, saves Savarkar from being castigated as an exacerbator of Hindu-Muslim discord. The book will definitely be helpful for an English reading audience as it does make use of Savarkar’s writings in the vernacular Marathi language, although a systematic study of popular and academic commentaries on Savarkar in Marathi still remains largely underexplored. That said, it remains far from being a definitive account of Hindu nationalism’s pioneering figure.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Crop of corridor of the cellular jail ( Ankur Panchbudhe CC BY SA 2.0).

About the author

Surajkumar Thube is a First Year DPhil student at the Faculty of History, University of Oxford. The title of his research project is ‘ Print, Language and Counterpublics: The Marathi Public Sphere in Late Colonial Western India, ca. 1920-1947’. He has previously contributed to Oxford Review of Books, The Book review magazine, Indian Cultural Forum, The Diplomat and Scroll.

“the fundamental point that being against casteism does not necessarily mean being against orthodoxy or the varna system”

Ambedkar himself complimented Savarkar as “among the very few who have realized that it is not enough to remove untouchability; for that matter you must destroy chaturvarnya.”

So no, whatever the ground may be between the two polarities, that’s not where Savarkar had stood. Also Musliyar was not a native of Tirurangadi. He had only moved in 14 years earlier. There was not class revolt he was handling, Vikram had missed out on nothing.

An extremely well-crafted and bigoted book review of a beautiful amalgamation of life and ideas of one of the greatest freedom fighters of mother India. The reviewer has conveniently chosen the words with his biased anti Savarkar ideology and has tried to find loads of faults in the works of Dr. Sampath. The role of Veer Savarkar as a social reformer and caste annihilator began post 1924 majorly which Dr. Sampath has elaborated in his 2nd book. He has been as unbiased as a historian should be which doesn’t bode well with the supposed leftist narrative of the west.

The detailed description of the horrors of Andaman Kaala Paani, his persistent efforts to get out through the legal route like Amnesty petition, conveniently termed as mercy petition by many, just goes to show the vast amount of legal knowledge Veer Savarkar possessed as he had almost gotten a barrister degree from London. Veer Savarkar refused to accept the degree since the erstwhile British government had put strict clauses of him not participating in any anti imperial activities.

All in all, this book is a riveting compilation of the first half of the life of a great freedom fighter, orator, poet, playwright and most importantly, a true patriot. Unlike the reviewer here, I would urge the reader to put aside any preconceived biases and read the book as a pure historical account with well documented facts.

Jab apna sikka hi khota ho toh dushmano ki kya jarurat hai.

Indian left thinkers are so predictable and so intellectually mediocre. Sampath is way above them.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related posts.

Literary Work and Contemporary Crisis: On Two Novels Concerning India

July 15th, 2020.

Book Review: Age of Entanglement: German and Indian Intellectuals across Empire by Kris Manjapara

March 6th, 2014.

Book Review: The Country of First Boys by Amartya Sen

January 11th, 2016.

Book Review: Emergency Chronicles: Indira Gandhi and Democracy’s Turning Point by Gyan Prakash

October 3rd, 2019, subscribe via email.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

- Prehistoric

- From History

- Cultural Icons

- Women In history

- Freedom fighters

- Quirky History

- Geology and Natural History

- Religious Places

- Heritage Sites

- Archaeological Sites

- Handcrafted For You

- Food History

- Arts of India

- Weaves of India

- Folklore and Mythology

- State of our Monuments

- Conservation

Savarkar’s Work on the Revolt of 1857

- AUTHOR Vaibhav Purandare

- PUBLISHED 26 August 2019

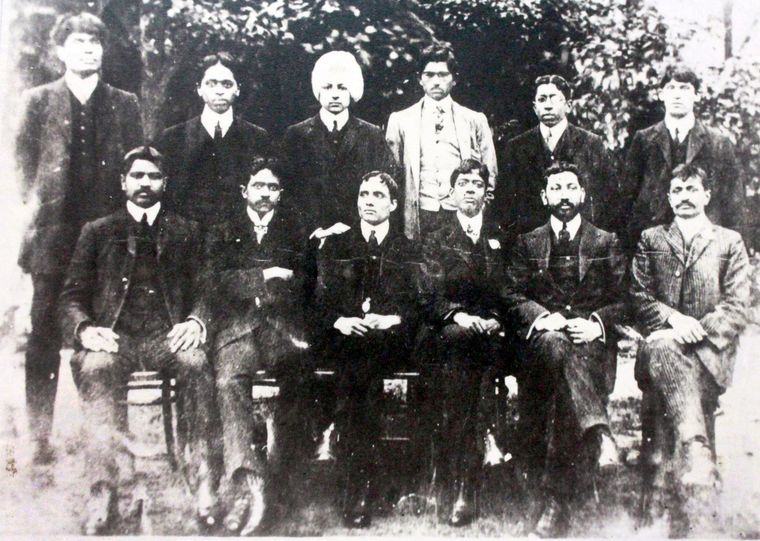

June was the month in which the mood of young Indians in cold, dreary London normally appeared to lift a little. Summer came and with it, some amount of cheer. But 1909 was proving to be something of an exception, especially for a bunch of students that in the past few years had been known to frequent India House, a sprawling five-storey mansion in the northern suburb of Highgate. The British Secret Service was familiar with the Cromwell Avenue structure as the rendezvous of firm believers in the theory of armed rebellion against the Raj, and its detectives had been tailing some of the regular visitors dutifully for some time. A handful of these twenty-something Indians, all members of the Free India Society formed in the heart of the Empire in 1907, were immensely perturbed, and not just because they suspected they were being shadowed.

The heat had in any case been on from 1907. The Times of London and the National Review had raised a red flag that year about their headquarters, India House, which they called the Highgate ‘house of mystery’, forcing the property’s owner and patron of its residents, Pandit Shyamji Krishnavarma, and his feisty Parsi aide, Bhikaiji Cama, to shift to Paris to evade action. Krishnavarma had been maintaining the place as a hostel where Indian students could stay and interact with their compatriots elsewhere in the British capital, but his principal Savarkar motive was to put together a young squad dedicated to the cause of freedom. Just when he thought things were finally coming together and more and more Indian students were showing an interest in attending weekend meetings at his address to discuss issues related to their homeland, he had had to pack his bags. After his sudden departure, Savarkar had more than simply kept the band of revolutionaries together as Krishnavarma had kept up the fl ow of funds from Paris. He had solidified contacts with Irish and Turkish nationalists, obtained manuals on the use and procurement of arms and, having added some more members to his clandestine inner circle, the Free India Society, he had emerged as the undisputed leader of India House.

Things at India House would soon take a far more serious turn. Savarkar was not happy with just making speeches and yearned to convert his philosophy into action. He insisted that rhetoric be combined with militant action and chalked out a plan in detail. Broadly, step one was to buy weapons from foreign revolutionaries in exile and ship them off to India. Step two, meant to be simultaneous, was to learn how to make small bombs and open factories in India for their manufacture. Step three involved the cultivation of Indian soldiers in the British-controlled Indian army in order to spark a rebellion within its ranks.

Thus, at one of the Sunday meetings, a chemistry student at London University whom we know only by his last name – Desai – lectured the group on the making of bombs, and Bapat and a Bengali revolutionary, Hemchandra Das (later implicated in the Alipur bomb case of 1909), got hold of a Russian-language manual on bomb-making and had it translated into English. Bapat, Das and Hotilal Varma, yet another Alipur revolutionary, set sail for India with several copies of the manual. After the connections between Abhinav Bharat and Bengal’s revolutionary outfit Anushilan Samiti were laid bare following eighteen-year-old Khudiram Bose’s bomb assault which had killed two Englishwomen in Muzaffarpur and the Maniktala police raid which had led to seizure of bombs from the Calcutta home of Aurobindo Ghose, Bapat succeeded in going underground, but Das and Varma failed to evade the police and were convicted and sentenced. Through his aides, Savarkar sent to India a bunch of Browning automatic pistols, sometimes through French-controlled Pondicherry and Portuguese-ruled Goa, naturally deemed much safer landing points.

– Meanwhile, deeply upset by the portrayal of the Rani of Jhansi, Bahadur Shah Zafar and other mutineers of the 1857 uprising as villains in a play on the London theatre circuit, the revolutionaries decided to hold a mass meeting in honour of the ‘martyrs’ on the revolt’s fifty-first anniversary.

Invites were sent out to Indians across Britain, and on 10 May 1908 the main hall of India House was overflowing. Youngsters had turned up from Oxford, Cambridge, Reading and Cirencester. The function began with a rendering of the national song ‘Vande Mataram’ by a group of young girls, and full-throated cries of ‘Vande Mataram’ – this time as a slogan – emanated from the crowd intermittently through the proceedings as speaker after speaker dwelt on the heroism of the fallen rebels. Savarkar’s personal poetic tribute, ‘Oh Martyrs’, circulated among those present, was a smashing success. Some Britishers had at the time launched a fund for their country’s veterans of 1857. The Indians now launched a fund for a memorial for their own heroes. Some students pledged to give up smoking and drinking for a month in order to be able to contribute; others said they would fast on certain days; and still others vowed to stay away from the theatre and other entertainments.

The launch of the martyrs’ memorial fund was followed by a flurry of activity. Two students of the agricultural college in Cirencester – the Sikh Harnam Singh and the Muslim R.M. Khan – quit the institution to protest the principal’s description of the 1857 revolutionaries as ‘murderers’. Both were honoured with silver medals and the title of ‘Yaar-e-Hind’ by a plucky London-based Punjabi woman, Dhan Singh.

– But in 1908 Savarkar made a far more significant contribution to the cause of the 1857 revolt which has stood the test of time.

Three months after his arrival in London in 1906 he had completed a Marathi translation of the Italian revolutionary Mazzini’s autobiography; it had sold more than 2000 copies in India as it had flown under the radar of government censors, and Savarkar’s preface, despite its implied meanings, had passed muster. After that he had been busy pounding the streets of London for more than a year and mining records at the India Office Library for material on the revolt. The result was the very first account of the uprising from an Indian point of view. The title of the book, written in Marathi and later translated into English (by W.V. Phadke and V.V.S. Aiyar) and into French (by Cama and M.P.T. Acharya), was The First Indian War of Independence. In it Savarkar vigorously contested the colonial theory of a mere ‘sepoy’ rebellion and hailed the uprising as an outstanding example of Hindu–Muslim unity. He cited mainly English sources to corroborate his arguments. In 1909 Scotland Yard obtained the still-unpublished first chapter through a mole – a Maratha by the name of Kirtikar – whom it had planted inside India House.

Kirtikar’s first name remains unknown, but what we do know is that he was about thirty years old and had earlier worked as a translator in the Bombay High Court. He was recruited as a spy and given a year’s leave to be in London, where he was told to take up lodgings at India House. He met Savarkar there without any letter of introduction and told him in their common language, Marathi, that he was from an aristocratic Maratha family. He was going to study dental surgery, he claimed. Savarkar accepted him as a lodger at India House without reservation, and Kirtikar even took admission to a dentistry course at a London institute. He would go out every morning and return late in the evening. That he was a spy was later discovered by Savarkar’s comrades Aiyar and Rajan. But by then Kirtikar had done much damage.

Scotland Yard also got to know, perhaps from Kirtikar again, that a copy of Savarkar’s yet-unpublished book had gone out to his brother Babarao in Nasik. The text was, in July 1909, immediately proscribed in India under the Customs Act, earning the distinction of becoming one of the earliest twentieth-century books to be banned even before it was published. Savarkar protested vehemently that pre-publication prescription, legal or not, was indubitably unfair.

There was no ban on the text in Britain itself – the colonizers had one set of rules for the homeland and another for a colony. This is what made London such an ideal ground for the revolutionaries. While the civil liberties of Indians could be short-circuited by the British anywhere, it was harder to do that in London.

But no printer in London would touch the manuscript. Attempts to print the book in France and Germany also failed, but the owner of a press in Holland finally agreed in the second half of 1909, and some copies were smuggled into India, allowed in at the ports because they came bearing beautiful dust-jackets of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist, David Copperfield and Great Expectations.

Quite a few reviewers of the time criticized Savarkar’s ornamental style of writing, and those loyal to the crown in particular had a problem with its content. London’s Times felt that the book was ‘in its way a very remarkable history of the Mutiny, combining considerable research with the grossest perversions of facts and great literary power with the intensest bitterness’. Yet the book profoundly stirred Indian emotions. Those inclined towards revolution were evidently impressed, but so too were those like Jawaharlal Nehru, at the time pursuing his education in Britain and warned by his father, Motilal, not to involve himself in political activities. A student of Trinity College in Cambridge, Nehru never set foot inside India House but described Savarkar’s account of 1857 as ‘a brilliant book though it suffers from proxility and want of balance occasionally’. Well after his return to India and plunge into the freedom struggle, Nehru wrote,

– ‘I have often felt that a new edition [of Savarkar’s book], more concise and with many of the oratorical flights left out, would be an ideal corrective to the British propaganda about the events of 1857.’

Excerpted with permission from ‘ Savarkar - The True Story of the Father of Hindutva ’ by Vaibhav Purandare, Juggernaut Books

Join us on our journey through India & its history, on LHI's YouTube Channel. Please Subscribe Here

Live history india is a first of its kind digital platform aimed at helping you rediscover the many facets and layers of india’s great history and cultural legacy. our aim is to bring alive the many stories that make india and get our readers access to the best research and work being done on the subject. if you have any comments or suggestions or you want to reach out to us and be part of our journey across time and geography, do write to us at [email protected].

Handcrafted Home Decor For You

Blue Sparkle Handmade Mud Art Wall Hanging

Handcrafted Tissue Box Cover Sea Green & Indigo Blue (Set of 2)

Scarlet Finely Embroidered Silk Cushion Cover

Sunflower Handmade Mud Art Wall Hanging

Best of Peepul Tree Stories

- About India Foundation

- Board of Trustees

- Governing Council

- Distinguished Fellows

- Deputy Directors

- Senior Research Fellows

- Research Fellows

- Research Associate

- Visiting Fellows

- Publications

- India Foundation Journal

- Issue Briefs

- Upcoming Events

- Event Reports

- Press Release

Looking for collaboration for your next project? Do not hesitate to contact us to say hello.

- apple podcasts

The Revolutionary Leader Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

As an intellectual fountainhead and founder of what is termed as “Hindu nationalism,” Vinayak Damodar Savarkar has emerged as one of the most controversial Indian political thinkers of the 20th Century. His writings on Hindutva have generated a great deal of attention for long and he has been eulogized and demonized in equal meausre for being the ideologue of Hindutva. In this paper, I explore the role and contribution of Savarkar as a revolutionary figure and briefly interpret the impact of his philosophy and writings on India’s revolutionary movement. The interpretations that we have had of Indian revolutionary thought are situated almost always within a Western Marxist lineage. Hence it becomes difficult for historians to accept that Savarkar was both a revolutionary and someone who also contributed to the making of a revolutionary thought. It would not be, in my opinion, an exaggeration to state that any history of revolutionary thought in early twentieth century India must examine the role of Savarkar’s works. Savarkar’s revolutionary inspiration was Italian political theorist Guiseppe Mazzini, rather than Karl Marx and other thinkers of the Marxist ideology. Savarkar used history as a tool and believed in writing about the contributions of past revolutionaries to stir and motivate individuals into armed fight against colonial injustices. He never wielded a weapon himself, but argued instead that writing histories was a necessary step in overthrowing colonial empires.

The important platform for pan-India anti-colonial voice had been the Indian National Congress, founded in 1885. But by the time of 1905 and the proposed Partition of Bengal, we see a distinct schism develop within the Congress wherein several nationalist leaders were becoming increasingly impatient with the attitude and responses of the Congress to the colonial power.

I argue here that the roots of this division in ideology could be traced back to the 1857 uprising, after which a diverse group comprising intellectuals, poets, mystics, philosophers, novelists, reformers, and spiritual leaders from around the country cultivated a distinctly Hindu anti-colonial nationalist discourse that combined inward spiritual development with external political freedom. This ideology emerged from the angst that despite her ancient culture and civilization, India had allowed herself to be defeated by a foreign country with a far inferior civilization. The spread of western attitudes among the small but growing middle class in urban colonial India only made matters more urgent. Mythological and historical imageries gave inspiration-‐ be it, an exiled ruler like Lord Rama, a teacher of duty like Lord Krishna, the heroic guerilla chieftain Chhatrapati Shivaji who conquered the might of the Mughals; and to this was added the symbolism of the India as a chained and captive mother beseeching her young sons to rescue her. These powerful iconographies inspired an entire generation of Indians into action.

The moderates under leaders such as Gopalkrishna Gokhale favoured a regionally restricted peaceful protest and talks, to resolve colonial domination of India. This was stoutly opposed by the ‘extremists’ such as Lala Lajpat Rai, Bipin Chandra Pal and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who denounced the Bengal partition in the strongest terms and spearheaded the nationwide Swadeshi or self-rule movement. Savarkar was a young undergraduate law student then and had come to the attention of the nationalists, especially Bal Gangadhar Tilak who considered Savarkar as his protégé, with his fiery speeches against partition. His affiliation with the extreme wing of nationalists was apparent even from his school days when, after being deeply affected by the execution of the Chapekar Brothers of Poona for assassinating British officials, he organized a secret revolutionary society called Rashtrabhakta Samuha, which later became the ‘Mitra Mela’ or the society of Friends in 1901 in his home town Nasik. There arefew original documents concerning this society because the members destroyed them all to prevent them falling into the hands of the British.

Savarkar believed in turning history and historical words into a tool or political weapon. He insisted that members of the Mitra Mela read works dealing with major historical figures, biographies of Mazzini, Garibaldi, Napoleon

Bonaparte. His dream was to produce an Indian nationalist, even among the villagers, who had a historical and revolutionary consciousness that was educated and inspired by these global revolutionary leaders.

Tilak recommended Savarkar’s name to that great colossus for all young Indian nationalists, Shyamji Krishna Varma, who gave scholarships to Indian students involved in revolutionary activities, to come and study in Europe. Shyamji had founded a monthly called the Indian Sociologist in 1905 that produced critical essays on the colonial government of India. He owned a house in Highgate called India House, which became a hostel of sorts for Indian students and turned into the hotbed for young Indian revolutionaries, many of whom were inspired by the movements taking place in Russia, Italy and other parts of Europe. The India House became a confluence of several leaders of the times which included, along with Savarkar, stalwarts such as Bhai Paramananda, Lala Hardayal, Virendranath Chattopadhyay, VVS Aiyar, Gyanchand Varma, Madame Bhikaji Cama, P.M. Bapat (Senapati), PT Acharya, WV Phadke, Madanlal Dhingra, Dr Rajan, KVR Swami, Shukla, Sukhsagar Dutta, Sikandar Hyat Khan, Asaf Ali, Khan of Nabha etc. 1 They held weekly meetings and celebrated anniversaries of great Indian heroes. The Scotland Yard that tracked their every movement within and outside London placed these young students under intense surveillance. 2

It was in 1906, that Savarkar left for London and immediately got involved in anti-colonial revolutionary activities from there. He worked with Shyamji Krishnavarma and other students to form a secret underground revolutionary society called the ‘Abhinav Bharat Society’. All members were required to take an oath declaring their personal commitment to the revolutionary objectives of the Society:

1 See Dhananjay Keer, Veer Savarkar

2 Detailed account of the surveillance of Indian revolutionaries is given by Richard Popplewell (1988), The Surveillance of Indian revolutionaries in GreatBritain and on the Continent, 1905–14, Intelligence and National Security, 3:1, 56-‐76,

I solemnly and sincerely swear that I shall from this moment do everything in my power to fight for independence…convinced that swarajya can never be attained except by the waging of a bloody and relentless war against the foreigner…and with this object, I join the Abhinav Bharat, the revolutionary society for all Hindustan.3

Within six months of reaching London, he translated Mazzini’s biography to Marathi. Over the next two years from 1908 to 1909, he completed his own monumental and meticulously researched history from the British Library archives of original East India Company documents, on the 1857 uprising terming it as “India’s First War of Independence.” He dismissed all the colonial arguments about the causes of 1857 of English historians of the greased cartridges, the economic motives of the elite or the doctrine of lapse etc. and instead powerfully argued that a nationalist ideology was what motivated the uprising and that it led to the end of Hindu-Muslim enmity towards achievement of a common cause. “Can any sane man,” he asked, “maintain that an all embracing Revolution could have taken place without a principle to move it? Could the vast tidal wave from Peshawar to Calcutta have risen in blood without a fixed intention of throwing something by means of its force.”4 He writes about revolutions in general, thus:

Every revolution must have a fundamental principle…A revolutionary movement cannot be based on a flimsy and momentary grievance. It is always due to some all-‐moving principle for which hundreds and thousands of men fight… The moving spirits of revolutions are deemed holy or unholy in proportion as the principle underlying them is beneficial or wicked…In history, the deeds of an individual or nation are judged by the character of the motive . . . To write a full history of a revolution means necessarily the tracing of all the events of that revolution back to their source-‐ “the motive”.5

3 Vinayak Chaturvedi (2013) A Revolutionary’s Biography: The Case of V DSavarkar, Postcolonial Studies, 16.2, p 128.

4 Savarkar,The Indian War of Independence(1909), p 3. 5 Ibid.p 4.

The ‘motives’ for Savarkar that he describes above, rested on the dual principles of swarajya and swadharma, which he defines as the love of one’s country and the love of one’s religion, respectively. For him, these were the quintessential guiding principles for all revolutionaries, both in India and outside, and believed that without these principles a true revolution was not possible or feasible. The book did not call for widespread revolution, mayhem, or anarchist violence in India. He was not a reckless revolutionary, but a strategist who advised his followers to strike when the iron is hot. Savarkar, instead, intended to give India a history of her own, to change the subject of history from the colonial state to a national state. In his introduction to the book he made clear that ‘history’ did important work for a nation and a national community, as he recognized it had done for England. He was going to do the same for India, by challenging the popular English accounts of our history. An informant leaked themanuscript of this book to Scotland Yard, and the work was banned before it was even published. It was perhaps one of the only literary works of the world to have this rare distinction of being proscribed even before it was published!

It was Savarkar’s intellectual output on revolutions and his philosophy that scared the British Government a lot more than his actual revolutionary acts, which were significant, but not as much as is made of them. Even as Savarkar was engaged in reading or smuggling bomb-making manuals and guns into India, his literary output and consequent ideological reach were much more dangerous. His associates Madame Bhikaji Cama and Sardar Singh Rana were sent by him to represent India at the International Socialist Congress held on 22 August 1907 at Stuttgart in Germany. They unfurled the Indian flag of independence designed by Savarkar and wanted to move a resolution declaring British rule, as disastrous but could not. But Cama’s speech was fiery and she made a passionate case for freeing India.6 Total freedom is what they postulated and no collaborations negotiations etc as the moderates wanted. Savarkar dispatched members of the Abhinav Bharat from India House to Paris to learn about bomb making, and while he had grandiose plans for sending some members to Belgium, Switzerland and Germany for military training, they never

6 For details of all these revolutionary activities see Dhananjay Keer, VeerSavarkar

materialized. He did, however, make copies of bomb manuals, which he sent to India, along with a few pistols for political assassinations. These were used by several revolutionaries such as Khudiram Bose, Prafulla Chakravarti, Kanailal Dutt, Satyendra Bose and by a seventeen-year-old AnantKanhere to assassinate a colonial official in Nasik. When caught, Kanhere implicated, among others, the Savarkar family. As a result, Savakar’s older brother and some family friends were arrested and sentenced to transportation for life in the Andaman Islands. Savarkar’s younger brother was also arrested in connection with a different conspiracy case in the same year. Back in England, Savarkar and other members of India House were already under surveillance. Despite this, Savarkar managed to inspire Madanlal Dhingra to assassinate former Viceroy Lord Curzon, Lord Morley and British MP Lord Curzon Wyllie. He succeeded in killing Curzon Wyllie in 1909 and was put to trial and eventually hanged. In a moving article in BandeMataram that was started by Madame Cama, Lala Hardayal wrote: “In times tocome, when the British Empire in India shall have been reduced to dust and ashes, Dhingra’s monuments will adorn the squares of our chief towns, recalling to the memory of our children the noble life and noble death of one who laid down his life in a far-off land for the cause he loved so well.” 7

On 13 March 1910, Savarkar was arrested on multiple criminal charges, including ‘procuring and distributing arms’, ‘sedition’, and ‘waging war against the King Emperor of India’. The unspoken fear in all the surveillance documents is that sedition and its effects were the real threat the colonial police had to contain. In 1911, the government opted to send Savarkar to India for his trial, rather than holding it in Britain. However, when the ship carrying Savarkar temporarily docked at Marseilles, France, Savarkar attempted to escape, jumping off the ship and swimming to shore. Unfortunately he was caught due to the treachery of an insider and was eventually sent back to India, tried and later given the maximum sentence of two transportations for life to the Kala Pani Cellular Jail in Andamans, totaling 50 years! Despite passing the law examination, he was never called by the Bench to practice and his degrees were all withdrawn once he was deported to Andamans. Till his conditional release in 1924, he was put to the greatest human tortures at Kala Pani, which are

7 Dhananjay Keer, Veer Savarkar, Chapter 4

horrifying to say the least. 8

C.A. Bayly suggests that intellectuals, like Savarkar, do not really fit into neat classifications of ‘Right or Left’, which, in any case, were probably ‘anachronistic’ for this period9 . In other words, ideas were circulated and received along multiple political trajectories forming complex ‘rhizomal networks’ on a global scale.10 And, because these networks generally functioned ‘underground’ and were classified as ‘criminal’ by states and empires, fathoming the intricate connections that made up the contemporary intellectual economy is often herculean.11

Quite curiously, Savarkar wrote a biography of himself as a revolutionary, written in the pseudo-name of Chitragupta, the mythical accountant of Yamaraj the Lord of Death, entitled “Life of Barrister Savarkar”. In other words, for Savarkar, just like works such as the history of 1857 or later his seminal work, Hindu Pad Padshahi on Maratha history, writing his own biography was meant toinfluence and inspire fellow-revolutionaries. Not surprisingly, the British government immediately banned the text, stating it to be a seditious text. But the book did manage to find light of day into the hands of sympathizers across the political spectrum, though in all its multiple reprints no one ever came to know who the author was. Savarkar also chose never to make this public till the time of his death in 1966 and even after India’s independence in 1947. It was only in the 1987 edition, in the preface that it was revealed that Chitragupta was none other than Savarkar and it was the penname he used. Almost every page has a reference to him as a “leader of the revolution.”

8 See Savarkar’s My Transportation for Life for details of the tortures in the

9 Bayly, Recovering Liberties, p 311. 10 Anderson, Under Three Flags, p 4. 11 Maia Ramnath,Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Charted Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire, Berkeley: Universityof California Press, 2011; and Daniel Bru ̈ckenhaus, The‘ TransnationalSurveillance of Anti-‐Colonialist Movements in Western Europe, 1905-‐1945’, unpublished PhD thesis, Yale University, 201

But interestingly, Vinayak Chaturvedi mentions that in an interview in 1976, Durga Das Khanna, former Chairman of the Punjab Legislative Council and himself a revolutionary, described how when he was interviewed by Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev Thapar for admission into the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), he was specifically asked by Bhagat Singh if he had read this book ‘Life of Barrister Savarkar’. So it almost seemed like an entry criteria for the HSRA recruits! Bhagat Singh is supposed to have been personally influenced immensely by Savarkar’s work on the 1857 Revolution as well. Copies of the book were found with almost all the members of the Lahore Conspiracy Case in the 1930s. 12

In conclusion, Savarkar’s own words summarize his philosophy of a revolution and its objectives:

Whenever the natural process of national and political evolution is violently suppressed by the forces of wrong, then revolution must step in as a natural reaction and therefore ought to be welcomed as the only effective instrument to re-enthrone Truth and Right. You rule by bayonets and under these circumstances it is a mockery to talk of constitutional agitation when no constitution exists at all. But it would be worse than a mockery, even a crime to talk of revolution when there is a constitution that allows the fullest and freest development of a nation. Only because you deny us a gun, we pick up a pistol. Only because you deny us light, we gather in darkness to compass means to knock out the fetters that hold our Mother down.13