An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Digg

Latest Earthquakes | Chat Share Social Media

Measurable Performance Verbs for Writing Objectives

Do not use the following verbs in your objectives: Know, Comprehend, Understand, Appreciate, Familiarize, Study, Be Aware, Become Acquainted with, Gain Knowledge of, Cover, Learn, Realize. These are not measurable!

Knowledge Verbs

Count, Define, Draw, Identify, Indicate, List, Name, Point, Quote, recognize, Recall, Recite, Read, Record, Repeat, State, Tabulate, Trace, Write

Comprehension Verbs

Associate, Compare, Compute, Contrast, Describe, Differentiate, Discuss, Distinguish, Estimate, Interpret, Interpolate, Predict, Translate

Application Verbs

Apply, Calculate, Classify, Complete, Demonstrate, Employ, Examine, Illustrate, Practice, Relate, Solve, Use, Utilize

Analysis Verbs

Order, Group, Translate, Transform, Analyze, Detect, Explain, Infer, Separate, Summarize, Construct

Synthesis Verbs

Arrange, Combine, Construct, Create, Design, Develop, Formulate, Generalize, Integrate, Organize, Plan, Prepare, Prescribe, Produce, Propose, Specify

Evaluation Verbs

Appraise, Assess, Critique, Determine, Evaluate, Grade, Judge, Measure, Rank, Rate, Select, Test, Recommend

« Return to Training Developer's Tool Box

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Brief research report article, a pragmatic master list of action verbs for bloom's taxonomy.

- Research in Health Professions Education, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom

Bloom's Taxonomy is an approach to organizing learning that was first published in 1956. It is ubiquitous in UK Higher Education (HE), where Universities use it as the basis for teaching and assessment; Learning Outcomes are created using suggested verbs for each tier of the taxonomy, and these are then “constructively aligned” to assessments. We conducted an analysis to determine whether there is consensus regarding the presentation of Bloom's Taxonomy across UK HE. Forty seven publicly available verb lists were collected from 35 universities and textbooks. There was very little agreement between these lists, most of which were not supported by evidence explaining where the verbs came from. We were able to construct a pragmatic “master list” of action verbs by using a simple majority consensus method. We were also able to construct a master list of commonly recommended “verbs to avoid.” These master lists should be useful for anyone tasked with using Bloom's Taxonomy to write Learning Outcomes for assessment. However, our findings raise broader questions about the evidence base which underpins a common approach to teaching and assessment in UK HE and education generally.

Introduction

Learning Outcomes are a starting point for education at many levels in many countries. They are a statement of what students should be able to do by the end of their learning, and form the basis for how students are assessed ( Biggs, 1996 ). In Higher Education (HE), in the United Kingdom (UK), it is a requirement of university accreditation to have learning outcomes mapped to levels of learning ( QAA, 2014 ).

Part of the origin of the concept of Learning Outcomes is Bloom's Taxonomy. First published in 1956 ( Bloom et al., 1956 ) and revised in 2002 ( Krathwohl, 2002 ), the motivation for the taxonomy was a desire to define learning and assessment in an observable, measurable way. This was in contrast to the perceived practice of the time; using “nebulous terms” to characterize the aims of teaching, for example for learners to “understand” or to “comprehend” or to “internalize” knowledge. The genesis of the taxonomy can be summarized in this quote from page one of the original publication:

“ what does a student do who “really understands” which he does not do when he does not understand?” ( Bloom et al., 1956 , 1)

Critical to writing effective Learning Outcomes is the use of specific and measurable verbs, avoiding verbs that are unobservable or unmeasurable and thus cannot be objectively assessed. For example a “good” Learning Outcome for an introductory research methods class might be to “ list the main research methods used in [a discipline],” whereas a “bad” learning outcome might be to “ know the main research methods….” According to the original version of the taxonomy, as expertise develops, the learner moves through a series of hierarchical steps, from “Knowledge,” through “Comprehension,” “Application,” “Analysis,” “Synthesis,” and “Evaluation.” Thus, by the end of a program of study we might want students to “ evaluate the use of research method X to test hypothesis Y.”

The taxonomy was designed to form the basis for assessment as well as teaching. The original taxonomy contained numerous sample test items designed for use by teachers, mapped to the different levels of the taxonomy ( Bloom et al., 1956 ), whereas the revised taxonomy was designed to emphasize more the use of the taxonomy in marking assessments, for example in scoring rubrics ( Anderson, 1999 ).

The taxonomy has become near ubiquitous in educational theory and practice across many countries. A Google Scholar search for “Bloom's Taxonomy” (April 2020) returns over 29,000 results, and indicates that the original taxonomy ( Bloom et al., 1956 ) has been cited over 34,000 times, with over 19,500 citations for the revised taxonomy ( Krathwohl, 2002 ). A search for “Blooms taxonomy” “assessment” returns 21,700 results.

Criticism of Bloom's taxonomy has been published for decades (e.g., Stedman, 1973 ). Much of the criticism arises from the perception of the taxonomy as a simplistic, blunt instrument, particularly with regards to so-called higher-order learning and thinking ( Ormell, 1974 ). Concerns have also been raised regarding the underlying epistemology and philosophy ( Pring, 1971 ; Sockett, 1971 ). A major criticism of the taxonomy is that it is not aligned to current evidence about how, and why, people learn. For example, Bloom and co were clear that the taxonomy was hierarchical, that “ the objectives in one class are likely to make use of and be built on the behaviors found in the preceding classes” ( Bloom et al., 1956 ). Even at a basic level this is troublesome. For example, in the revised taxonomy “understanding” precedes “analysis” and “application.” It could easily be argued that understanding comes from analysis and application rather than the other way round. The original taxonomy makes it clear that students are expected to perform better on assessments that are mapped to the lower tiers of the taxonomy, yet faculty show only a modest ability to map exam questions on Bloom's Taxonomy, even when the taxonomy is collapsed into three tiers ( Karpen et al., 2017 ; Dempster and Kirby, 2018 ).

Bloom and co recognized many of these problems which would later be leveled as criticisms. For example, the overlap between the different classifications, and the fact that two students demonstrating the same observable behavior in an assessment may have arrived at that behavior in completely different ways, representing different types and even different levels of learning. One example quoted is as follows;

“ For example, two students solve an algebra problem. One student may be solving it from memory, having had the identical problem in class previously. The other student has never met the problem before and must reason out the solution by applying general principles, We can only distinguish between their behaviors as we analyze the relation between the problem and each student's background of experience.” ( Bloom et al., 1956 )

Despite these criticisms, the taxonomy remains near-ubiquitous in UK Higher Education, although the format of the taxonomy is often a considerably simplified version of the 216 page original. As we describe below, the websites of many UK universities contain an image of the hierarchical taxonomy in some form, normally a triangle, along with guidance about how to write Learning Outcomes based on the taxonomy. The forms in which the taxonomy appears vary considerably, but most include lists of verbs aligned to each step of the hierarchy. The verbs themselves appear to be derived, originally, from the subheadings of the tiers in the original and revised taxonomies. The verbs at the lower end of the hierarchy tend to be associated with assessments that might be used to test factual knowledge; “ list,” describe,” “identify.” Those at the higher end tend to be associated with assessments of “higher order thinking,” for example “ appraise” or “ evaluate.”

Given the age and ubiquity of the taxonomy, it seems reasonable to ask whether it is consistent. If multiple universities are basing teaching and assessment on learning outcomes mapped to the taxonomy; are they asking for the same thing? An analysis of the verb lists aligned with Blooms Taxonomy shown on 30 different educational websites from the USA found that there was very little agreement between the versions of Bloom's Taxonomy found, i.e., verbs which were suggested as belonging to one tier of the hierarchy on one version of the taxonomy were found, on a different list, to be associated with a different tier. The degree of disagreement between the different versions of Bloom's was considerable. Not a single verb was assigned to the same tier by all 30 lists. Three verbs ( choose, relate, select ) appeared in all six tiers, depending on which list was consulted ( Stanny, 2016 ).

Here we repeat and expand the work of Stanny, in the context of UK Higher Education. Having found similar results, we also attempt to salvage something useful from the current inconsistencies of Blooms Taxonomy, by applying a pragmatic philosophy and research method. Pragmatic research prioritizes the undertaking of research that is practically useful ( Feilzer, 2010 ), choosing the most appropriate methodology to address the research question(s) ( Creswell, 2003 ). The knowledge that results from pragmatic research is valued for how useful it can be to address real world problems, that affect people ( Duram, 2010 ). This methodology is often contrasted with approaches which prioritize other aspects of the research process, such as the definition of the epistemological position taken in a research activity.

In this paper then the research questions we seek to address are

1. How consistent is the presentation of Bloom's taxonomy to the UK Higher Education Sector by the websites of Universities and other stakeholders in the sector that present the taxonomy?

2. Can we identify a useful consensus position of the verbs identified within the taxonomy?

In line with the pragmatic approach, the primary stakeholders for whom we intend the findings to be useful are teaching staff responsible for writing Learning Outcomes, with follow-on value to their students and universities.

A previous project ( Ransome and Newton, 2017 ) identified the textbooks most commonly recommended to academics taking postgraduate certificates in Higher Education; the basic “teacher training” programmes currently used in UK HE. Of the six most commonly recommended books on general higher education, three included a version of Bloom's taxonomy and a verb list ( Fry et al., 2003 ; Butcher et al., 2006 ; Biggs and Tang, 2011 ).

Stanny (2016) identified verb lists using a simple Google search for the string “action words for Bloom”s taxonomy.” To restrict our analysis to UK Higher Education we conducted a Google Search for the terms.”ac.uk” and “Bloom's Taxonomy.” We then included verb lists from university websites where the taxonomy was used as part of guidance for writing learning outcomes, or some other way or organizing or planning learning. This approach returned a total of 47 verb lists identified from 35 different sources (some sources included multiple lists). Of the 35 sources, 31 were UK Universities, 3 were the aforementioned textbooks and the final one was the UK Higher Education Academy, now called Advance HE, a professional body for academic teachers in UK Higher Education. We did not include search results that were about Bloom's taxonomy itself, for example research that cited the taxonomy. We only included verb lists that had six tiers from Blooms taxonomy, either the original or the revised (in addition to the 47 analyzed we also found 3 that combined the two 6-tier taxonomies into a 7-tier taxonomy, and two which used a five-tier list). Where a university linked to an external site with multiple lists, we transcribed only the first list.

Of the 47 lists, there was little consistency in terms of whether they used the original taxonomy, the revised taxonomy, a combination of the two, or a hybrid of the two. Thus, as in the work of Stanny (2016) , we considered both the original and the revised taxonomy together. The 47 lists were transcribed into a single excel spreadsheet. Some sources included a list of “verbs to avoid” and these were also transcribed. The transcription of each list was rechecked by at least one author. Each source was examined to determine whether it directly cited the original version of Bloom's taxonomy ( Bloom et al., 1956 ), or the revision ( Krathwohl, 2002 ) or some other source explaining how the list of verbs was arrived at. This was also rechecked by at least one author.

Terms were rationalized into agreed verbs meanings between lists, for example “be familiar with” and “familiarize” were both rationalized to “familiar.” This rationalization was not performed where both versions appeared in the same list (e.g., one list included “solve” and “solution”) or where there appeared to be an error in the original list that could not be simply corrected (e.g., one list proposed the verb “or recount”). Unnecessary prefixes or suffixes were also removed, for example “have a good grasp of” was rationalized to “grasp.” UK English was used throughout (e.g., memorize was changed to memorise). These changes were agreed by all three authors.

Unique Verbs

A total of 401 unique verbs were contained across the 47 lists. The full list of sources and verbs is shown in Appendix 1 . Many verbs appeared in multiple lists and across multiple tiers of each list. Two hundred and fifty one unique verbs appeared in only one tier. These were distributed as follows; 43 for the Knowledge tier, 30 for Comprehension, 45 for Analysis, 54 for Application, 52 for Synthesis and 27 for Evaluation. Of the remaining 150 verbs, 71 were present in two tiers, 46 in three tiers, 24 in four tiers, 5 in five tiers. Four verbs ( select, explain, relate, arrange ) appeared across all six tiers of the taxonomies. Two of these ( select and relate ) also appeared across all six tiers in the analysis of US sites undertaken by Stanny, along with the verb choose ( Stanny, 2016 ).

Unique Verbs Within and Across Tiers

To determine whether there is any consensus regarding the format of Bloom's Taxonomy, we examined the frequency with which one-tier verbs appeared within the tiers. Not one of the 251 one-tier verbs appeared in all 47 lists. The most common was “list,” which appeared in the “Knowledge” tier in 43 of the 47 lists. Only 10 of the 251 one-tier verbs appeared in more than half (24+) of the lists, and none of these were in the top two tiers of the taxonomy. In contrast, 214 (85%) of the one-tier verbs appeared in 5 or fewer of the lists, suggesting that most of the verbs which appeared in only one tier were very uncommon and potentially newer, perhaps explaining why they only appeared in one tier. Eyeballing the list appeared to confirm this—these verbs included terms like “tweet,” “google,” wiki build,” “film,” and “video blog”; terms which are anchored in a particular technology rather than the underlying learning. Considering that both the original taxonomies proposed some sort of overlap between tiers we relaxed the analysis to include verbs that were included across two tiers did not add much in terms of identifying consensus; only 6 (8%) of the 71 two-tier verbs were in more than half the lists.

Master List of Verbs

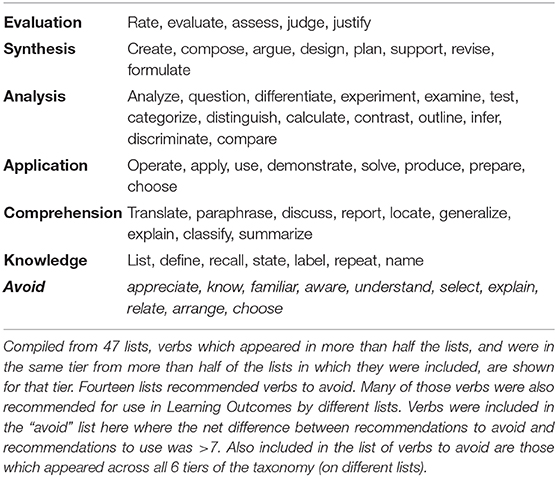

Due to the limited lack of agreement between lists, we applied a simple majority consensus method to the construction of a master list. From the 47 lists, we first identified verbs which appeared in >50% (24+) of the lists. From that list we then identified verbs for which 50% of their appearances were in one specific tier. The results are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1 . A Master list of Action Verbs for Learning Outcomes written using Bloom's Taxonomy.

Verbs to Avoid

Fourteen sources recommended a list of verbs to avoid. Many of those verbs were also recommended for use in Learning Outcomes by different lists. To identify a “master list” of verbs to avoid, we calculated the net difference between recommendations to avoid and recommendations to use. Verbs were included in the “master avoid” list when the net difference was >7. We also added in those five verbs which appeared across all six tiers of the taxonomy in our analysis and that of Stanny (2016) . The results are also shown in Table 1 .

Eight lists cited both the original and the revised taxonomy. Ten lists cited only the original, four lists cited only the revised, 25 lists did not offer a citation. None of the sources gave any other citations that explained where the verb lists came from although other works were often cited to support the linking of verb lists and learning outcomes to assessments (e.g., Biggs, 1996 ; Moon, 2004 ; Biggs and Tang, 2011 ).

The writing of Learning Outcomes based on Bloom's taxonomy is a common approach to organizing teaching and assessment. Verb lists based on the taxonomy are found on the websites of many UK Universities and in the textbooks recommended to academic staff as part of teacher training programmes in UK HE. Our findings demonstrate that there is not any one format representing “Bloom's Taxonomy,” echoing findings from other settings ( Almerico and Baker, 2004 ; Stanny, 2016 ). Thus, the action verbs used by one university to plan learning at one tier of the hierarchy may be used to represent different tiers at other universities. For example, four verbs ( select, explain, relate, arrange ) appeared across all six tiers of the taxonomies. Two of these ( select and relate ) were the most commonly cited verbs, appearing 80 and 87 times, respectively. They also appeared across all six tiers in the analysis of US sites undertaken by Stanny, along with the verb choose ( Stanny, 2016 ). As another example of basic problems with the current status of the taxonomy, two verbs ( understand and know ) commonly cited as problematic for writing specific learning outcomes even in the original taxonomy ( Bloom et al., 1956 ), were actually recommended for use by five of the lists. At least one university with a proposed list of verbs to avoid, then recommended some of those same verbs for use in the taxonomy.

Does it matter that there is a lack of consistency between UK HE providers with regard to the verbs they use to map learning to the different levels? Part of the answer to this depends on whether the lists are actually used. Future work to answer this could include an analysis of whether the verb list proposed for use at a particular university actually maps on to the learning outcomes used at that University. The current analysis could also be developed through further discussion with subject experts to expand the master taxonomy devised here, and identify subject-specific verbs and assessments.

It could be argued that having diversity within the sector is a good thing. The taxonomy was revised in 2001, demonstrating it has evolved over time. The existence of two versions of the taxonomy might also be thought to explain some of the heterogeneity in the verb lists. However, these arguments are undermined by the lack of any supporting evidence provided, by the University webpages, for the verb lists proposed. Twenty five lists did not offer a citation of Bloom's taxonomy and no other obvious citations were given, by any source, to support the hierarchical nature of the taxonomy or the verb lists contained within. Many universities directed their staff to external sources for the verb list; blogs and other informal sites, often with multiple colorful representations of the taxonomy, some including apps that map to the taxonomy and so clearly post-date either of the published versions of the taxonomy. This seems problematic given that a fundamental basis of UK Higher Education, in fact a requirement of university accreditation, is having learning outcomes mapped to levels of learning; this is one of the ways in which consistency can be achieved across the sector ( QAA, 2014 ). Most of the sources used here were offering up Blooms Taxonomy in support of these levels and the writing of learning outcomes mapped to them, but did not cite either version of the published versions of Bloom's taxonomy and represented the taxonomy in very different ways, including many which merged the two versions together. This aforementioned diversity then is not evidence-based.

There is a broader question of whether the taxonomy accurately represents how we learn. A misalignment of learning science and the taxonomy was identified even when the taxonomy was first published in 1956. Bloom and co-wrote that, basically, there was no satisfactory, unifying, theory for how people learn, and that their taxonomy would make it easier for such a theory to be developed, even going so far as to state that

“ our method of ordering educational outcomes will make it possible to define the range of phenomena for which such a theory must account.” ( Bloom et al., 1956 )

In essence, they are saying “this is what learning looks like, now you have to explain how it happens.”

This is not the case now. There is an abundance of evidence from psychology, sociology, and neuroscience to explain how, and why, people learn, and what that looks like at the behavioral level ( Bjork and Bjork, 2011 ; Dunlosky et al., 2013 ; Cowan, 2014 ; Freeman et al., 2014 ; Deslauriers et al., 2019 ) There is clearly a great deal that we do not know, but we propose that any attempt to classify learning outcomes should now be based on the science of learning, rather than the other way round. This could eventually lead to a revised, third version of the taxonomy that is grounded in an evidence-based understanding of how we learn.

There are many approaches used in education which are not supported by rigorous evidence. The use of some, such as the matching of teaching to so-called “Learning Styles,” have been directly contradicted by research evidence many years ago ( Coffield et al., 2004 ; Pashler et al., 2008 ) and yet are still very popular in HE ( Newton, 2015 ; Newton and Miah, 2017 ). We should therefore expect that Bloom's taxonomy will remain part of an approach to organizing learning in UK HE for the foreseeable future, despite the lack of evidence used to support the formats in which it is currently presented. Rather than simply complain about this, we offer up Table 1 as an approach to some sort of consensus regarding verbs to use, and of verbs to avoid. The broad consensus method used to generate the table allows for the fact that many of the verbs appeared in multiple tiers, a principle that is consistent with the principles of the revised taxonomy which proposes that the tiers, in particular the upper tiers, are not a fixed rigid hierarchy ( Krathwohl, 2002 ). This principle is lost in the presentation of the taxonomy on the website of the UK universities analyzed here, where the verbs are simply presented in fixed lists and without reference to the supporting literature.

From a pragmatic perspective, for those wishing to (or required to) use Bloom's or any other taxonomy, we would advise careful inspection of the verbs in context before adopting any correspondence between verbs and any learning of a certain complexity. Given that verbs themselves can be used in different tiers we would further advise against establishing automatic correspondence between the isolated verb and HE level when designing or evaluating modules or programmes. We would echo the advice given by others that the best way to give meaning to a learning outcome is to identify the assessment type(s) that might map to that outcome ( Ewell and Schneider, 2013 ) and that this is, itself, a test of whether one has written a useful Learning Outcome ( Adelman, 2015 ). If an educator wishes to use any sort of hierarchical taxonomy to classify and map their outcomes, then we propose going further still and asking educators to identify assessments that would not be suitable for an outcome mapped to a specific level of the hierarchy.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material .

Author Contributions

PN designed the study, collected the data, checked the transcribed data, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. AD and LP recollected the data for verification, checked the transcribed data, and provided critical revisions of the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of Ms. Judy Williams who transcribed the original verb lists into an excel spreadsheet.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.00107/full#supplementary-material

Adelman, C. (2015). “To imagine a verb: the language and syntax of learning outcomes stateme,” Occasional Paper No. 24 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment 201. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED555528.pdf .

Almerico, G. M., and Baker, R. K. (2004). Bloom's taxonomy illustrative verbs: developing a comprehensive list for educator use. Florida Assoc. Teach. Educ. J. 1, 1–10.

Google Scholar

Anderson, L. W. (1999). Rethinking Bloom's Taxonomy: Implications for Testing and Assessment . Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED435630.pdf (accessed December 25, 2019).

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High. Educ. 32, 347–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00138871

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Biggs, J., and Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University . McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Bjork, E. L., and Bjork, R. (2011). “Making Things hard on yourself, but in a good way: creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning,” in Psychology and the Real World: Essays Illustrating Fundamental Contributions to Society, 2nd Edn , (Worth Publishers, 59–68.

Bloom, B. S., Englehart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., and Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook 1. Cognitive Domain. London: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd.

Butcher, C., Davies, C., and Highton, M. (2006). Designing Learning: From Module Outline to Effective Teaching . Taylor and Francis.

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., and Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning Styles and Pedagogy in Post 16 Learning: A Systematic and Critical Review. The Learning and Skills Research Centre . Available online at: http://localhost:8080/xmlui/handle/1/273 (accessed December 25, 2019).

Cowan, N. (2014). Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 26, 197–223. doi: 10.1007/s10648-013-9246-y

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Chapter 1: “a framework for design,” in Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.), 9–11.

Dempster, E. R., and Kirby, N. F. (2018). Inter-rater agreement in assigning cognitive demand to life sciences examination questions. Perspect. Educ. 36, 94–110. doi: 10.18820/2519593X/pie.v36i1.7

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., and Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 19251–19257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., and Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students learning with effective learning techniques: promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 14, 4–58. doi: 10.1177/1529100612453266

Duram, C. (2010). “Pragmatic study,” in Encyclopedia of Research Design , ed A. Leslie (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.), 1073–1075.

Ewell, P., and Schneider, C. G. (2013). National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment in Occasional Paper #16. The Lumina Degree Qualifications Profile (DQP): Implications for Assessment . University of Illinois.

Feilzer, M. (2010). Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. J. Mixed Methods Res. 4, 6–16. doi: 10.1177/1558689809349691

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 8410–15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Fry, H., Ketteridge, S., and Marshall, S. (2003). Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education . Psychology Press.

Karpen, S. C., Welch, A. C., Cross, L. B., and LeBlanc, B. N. (2017). A multidisciplinary assessment of faculty accuracy and reliability with bloom's taxonomy. Res. Pract. Assess. 12, 96–105.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of bloom's taxonomy: an overview. Theory Into Pract. 41, 212–18. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Moon, J. (2004). Linking Levels, Learning Outcomes and Assessment Criteria. Exeter University, Bologna seminar . Available online at: http://aic.lv/ace/ace_disk/Bologna/Bol_semin/Edinburgh/J_Moon_backgrP.pdf (accessed December 25, 2019).

Newton, P. M. (2015). The learning styles myth is thriving in higher education. Educ. Psychol. 6:1908. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01908

Newton, P. M., and Miah, M. (2017). Evidence-based higher education – is the learning styles “Myth” important? Front. Psychol. 8:444. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00444

Ormell, C. P. (1974). Bloom's taxonomy and the objectives of education. Educ. Res. 17, 3–18. doi: 10.1080/0013188740170101

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., and Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: concepts and evidence. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 9, 105–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

Pring, R. (1971). Bloom's taxonomy: a philosophical critique (2). Cambridge J. Educ. 1, 83–91. doi: 10.1080/0305764710010205

QAA (2014). UK Quality Code for Higher Education Part A: Setting and Maintaining Academic Standards .

Ransome, J., and Newton, P. M. (2017). Are we educating educators about academic integrity? a study of UK higher education textbooks. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1300636

Sockett, H. (1971). Bloom's taxonomy: a philosophical critique (I). Cambridge J. Educ. 1, 16–25. doi: 10.1080/0305764710010103

Stanny, C. J. (2016). Reevaluating bloom's taxonomy: what measurable verbs can and cannot say about student learning. Educ. Sci. 6:37. doi: 10.3390/educsci6040037

Stedman, C. H. (1973). An analysis of the assumptions underlying the taxonomy of educational objectives: cognitive domain. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 10, 235–41. doi: 10.1002/tea.3660100307

Keywords: learning outcomes, pragmatism, evidence-based education, Blooms taxonomy, assessment, constructive alignment

Citation: Newton PM, Da Silva A and Peters LG (2020) A Pragmatic Master List of Action Verbs for Bloom's Taxonomy. Front. Educ. 5:107. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00107

Received: 18 April 2020; Accepted: 05 June 2020; Published: 10 July 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Newton, Da Silva and Peters. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Philip M. Newton, p.newton@swansea.ac.uk

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

Published on July 12, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on November 20, 2023.

Research objectives describe what your research is trying to achieve and explain why you are pursuing it. They summarize the approach and purpose of your project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement . They should:

- Establish the scope and depth of your project

- Contribute to your research design

- Indicate how your project will contribute to existing knowledge

Table of contents

What is a research objective, why are research objectives important, how to write research aims and objectives, smart research objectives, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research objectives.

Research objectives describe what your research project intends to accomplish. They should guide every step of the research process , including how you collect data , build your argument , and develop your conclusions .

Your research objectives may evolve slightly as your research progresses, but they should always line up with the research carried out and the actual content of your paper.

Research aims

A distinction is often made between research objectives and research aims.

A research aim typically refers to a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear at the end of your problem statement, before your research objectives.

Your research objectives are more specific than your research aim and indicate the particular focus and approach of your project. Though you will only have one research aim, you will likely have several research objectives.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Research objectives are important because they:

- Establish the scope and depth of your project: This helps you avoid unnecessary research. It also means that your research methods and conclusions can easily be evaluated .

- Contribute to your research design: When you know what your objectives are, you have a clearer idea of what methods are most appropriate for your research.

- Indicate how your project will contribute to extant research: They allow you to display your knowledge of up-to-date research, employ or build on current research methods, and attempt to contribute to recent debates.

Once you’ve established a research problem you want to address, you need to decide how you will address it. This is where your research aim and objectives come in.

Step 1: Decide on a general aim

Your research aim should reflect your research problem and should be relatively broad.

Step 2: Decide on specific objectives

Break down your aim into a limited number of steps that will help you resolve your research problem. What specific aspects of the problem do you want to examine or understand?

Step 3: Formulate your aims and objectives

Once you’ve established your research aim and objectives, you need to explain them clearly and concisely to the reader.

You’ll lay out your aims and objectives at the end of your problem statement, which appears in your introduction. Frame them as clear declarative statements, and use appropriate verbs to accurately characterize the work that you will carry out.

The acronym “SMART” is commonly used in relation to research objectives. It states that your objectives should be:

- Specific: Make sure your objectives aren’t overly vague. Your research needs to be clearly defined in order to get useful results.

- Measurable: Know how you’ll measure whether your objectives have been achieved.

- Achievable: Your objectives may be challenging, but they should be feasible. Make sure that relevant groundwork has been done on your topic or that relevant primary or secondary sources exist. Also ensure that you have access to relevant research facilities (labs, library resources , research databases , etc.).

- Relevant: Make sure that they directly address the research problem you want to work on and that they contribute to the current state of research in your field.

- Time-based: Set clear deadlines for objectives to ensure that the project stays on track.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Research objectives describe what you intend your research project to accomplish.

They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement .

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, November 20). Research Objectives | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-objectives/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Best Active Verbs for Research Papers with Examples

What are active verbs.

Active verbs, often referred to as "action verbs," depict activities, processes, or occurrences. They energize sentences by illustrating direct actions, like "run," "write," or "discover." In contrast, linking verbs connect the subject of a sentence to its complement, offering information about the subject rather than denoting an action. The most common linking verb is the "be" verb (am, is, are, was, were, etc.), which often describes a state of being. While active verbs demonstrate direct activity or motion, linking and "be" verbs serve as bridges, revealing relations or states rather than actions.

While linking verbs are necessary to states facts or show connections between two or more items, subjects, or ideas, active verbs usually have a more specific meaning that can explain these connections and actions with greater accuracy. And they captivate the reader’s attention! (See what I did there?)

Why are active verbs important to use in research papers?

Using active verbs in academic papers enhances clarity and precision, propelling the narrative forward and making your arguments more compelling. Active verbs provide clear agents of action, making your assertions clearer and more vigorous. This dynamism ensures readers grasp the research's core points and its implications.

For example, using an active vs passive voice sentence can create more immediate connection and clarity for the reader. Instead of writing "The experiment was conducted by the team," one could write, "The team conducted the experiment."

Similarly, rather than stating "Results were analyzed," a more direct approach would be "We analyzed the results." Such usage not only shortens sentences but also centers the focus, making the statements about the research more robust and persuasive.

Best Active Verbs for Academic & Research Papers

When writing research papers , choose active verbs that clarify and energize writing: the Introduction section "presents" a hypothesis, the Methods section "describes" your study procedures, the Results section "shows" the findings, and the Discussion section "argues" the wider implications. Active language makes each section more direct and engaging, effectively guiding readers through the study's journey—from initial inquiry to final conclusions—while highlighting the researcher's active role in the scholarly exploration.

Active verbs to introduce a research topic

Using active verbs in the Introduction section of a research paper sets a strong foundation for the study, indicating the actions taken by researchers and the direction of their inquiry.

Stresses a key stance or finding, especially when referring to published literature.

Indicates a thorough investigation into a research topic.

Draws attention to important aspects or details of the study topic you are addressing.

Questions or disputes established theories or beliefs, especially in previous published studies.

Highlights and describes a point of interest or importance.

Inspects or scrutinizes a subject closely.

Sets up the context or background for the study.

Articulates

Clearly expresses an idea or theory. Useful when setting up a research problem statement .

Makes something clear by explaining it in more detail.

Active verbs to describe your study approach

Each of these verbs indicates a specific, targeted action taken by researchers to advance understanding of their study's topic, laying out the groundwork in the Introduction for what the study aims to accomplish and how.

Suggests a theory, idea, or method for consideration.

Investigates

Implies a methodical examination of the subject.

Indicates a careful evaluation or estimation of a concept.

Suggests a definitive or conclusive finding or result.

Indicates the measurement or expression of an element in numerical terms.

Active verbs to describe study methods

The following verbs express a specific action in the methodology of a research study, detailing how researchers execute their investigations and handle data to derive meaningful conclusions.

Implies carrying out a planned process or experiment. Often used to refer to methods in other studies the literature review section .

Suggests putting a plan or technique into action.

Indicates the use of tools, techniques, or information for a specific purpose.

Denotes the determination of the quantity, degree, or capacity of something.

Refers to the systematic gathering of data or samples.

Involves examining data or details methodically to uncover relationships, patterns, or insights.

Active verbs for a hypothesis or problem statement

Each of the following verbs initiates a hypothesis or statement of the problem , indicating different levels of certainty and foundations of reasoning, which the research then aims to explore, support, or refute.

Suggests a hypothesis or a theory based on limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.

Proposes a statement or hypothesis that is assumed to be true, and from which a conclusion can be drawn.

Attempts to identify

Conveys an explicit effort to identify or isolate a specific element or relationship in the study.

Foretells a future event or outcome based on a theory or observation.

Theorizes or puts forward a consideration about a subject without firm evidence.