- Contractors

- Junior Professional

How to develop critical thinking skills in finance & accounting

Stephen Moir

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

When it comes to finance and accounting roles, employers are increasingly looking for problem solvers, not a number-crunchers. Over recent years, we have seen an increasing demand for people who can analyse and interpret data and think critically.

What is critical thinking.

A critical thinker is a problem solver. They are able to evaluate complex situations, weigh-up different options and reach logical (and often quite creative) conclusions.

Critical thinkers are highly-valued by employers as they innovate and make improvements, without taking unnecessary risks. Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand recently identified that it was in the top 10 attributes that will help you get noticed in the job market.

Why are critical thinking skills important?

Once you have learnt how to develop critical thinking skills you will be better able to add value to data, interpret trends within the business, understand how people and performance intersect and take-on broader commercial outlook that benefits the business.

How to develop critical thinking skills

Critical thinking comes naturally to some people, but it is also a skill than can be practiced. Here are some tips for how to develop your own critical thinking skills :

- Examine: Self-awareness is the foundation of critical thinking. It allows you to play to your strengths and address your weaknesses. Question how and why you do things the way you do.

- Analyse: Look for opportunities to grow and improve. Consider alternative solutions to the problems you encounter in your work.

- Explain: Clear communication is key. Get into the habit of talking through your reasoning and conclusions with colleagues.

- Innovate: Develop an independent mind-set. Find ways to think outside the box and challenge the status quo. Make sure your decisions are well-thought out. A critical thinker is logical as well as creative.

- Learn: Keep an open and well-oiled mind. Brush-up on your problem-solving skills by doing brain-teasers or trying to solve problems backwards. Keep up-to-date with professional learning opportunities . You may also need to unlearn past mindsets in order to grow and move forward.

How to apply critical thinking skills in your current role

Could you implement a new process or procedure that enhances performance or profitability? You might also consider volunteering for a new project or responsibility that gives you the opportunity to innovate and take on a new challenge. It’s a great way to broaden your skillset and gain exposure to other parts of the business.

Surround yourself with other critical thinkers in the organisation and work together towards achieving a problem-solving culture. Ask questions, and always look for opportunities for continual learning.

Changing roles to develop critical thinking skills

At Moir Group, we are passionate about finding the right cultural fit between people and the organisations they work with. If you are a critical thinker, it’s worth looking for a stimulating work environment that encourages innovation and non-conformist thinking when considering your next role.

How to demonstrate critical thinking skills at an interview

During an interview, use examples from your past experiences to demonstrate your problem-solving abilities. Show that you can be analytical, weigh-up pros and cons, consider other view points and be creative in your solutions. Clearly articulating your thought process is key.

Sometimes an interviewer will ask you to simplify the complex as a way of determining your clarity of thought. For example: “How would you explain the state of the economy to a kindergarten child?” In instances like these, the focus will be on how you explain your reasoning, rather than achieving a ‘right’ answer. Learn more here.

If you’re looking to take that next step in your career, we can help. Get in touch with us here .

2 Responses to “How to develop critical thinking skills in finance & accounting”

Hi Stephen,

The above is very useful and very valuable for employers. However my understanding of critical thinking is slightly different from above. I recently listened to a course in critical thinking by Professor Steven Novella of Yale School of Medicine. To keep it simple it is to do with assessing the veracity of views and statements made by oneself, others and media being constantly aware of the many biases, the flaws and fabrications of memory, half truths, unspoken truths, and even lies. So it becomes key to adopt an inquisitive mindset, to look for external evidence that supports argument and not just wishful or hopeful thinking.

Just wanting to add to the debate as this is a really important area.

Hi Richard,

We are pleased that found this article useful. Thanks for your sharing your thoughts about critical thinking.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Moir Group acknowledges Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and recognises the continuing connection to lands, waters and communities. We pay our respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures; and to Elders past and present and encourage applications from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and people of all cultures, abilities, sex, and genders.

This site uses cookies to store information on your computer. Some are essential to make our site work; others help us improve the user experience. By using the site, you consent to the placement of these cookies. Read our privacy policy to learn more.

- CPA INSIDER

Top soft skills for accounting professionals

Soft skills are key to career advancement. one cpa at the forefront of recruitment and professional development shares tips for boosting these critical skills..

- Professional Development

Communication

- Career Development

As professionals advance in an accounting or finance career, soft skills become increasingly important. In a world that is becoming more digital, computerized, and automated, soft skills can be the differentiator between two employees competing for the same promotion or position.

In fact, in a recent survey reported by the Society for Human Resource Management, 97% of employers stated soft skills were either as important or more important than hard skills. Whether a professional is looking for a new job or seeking a promotion, focusing on and developing soft skills can help employees be more well-rounded and employable professionals.

What I am seeing, for my own team and firmwide working with hiring companies, is the importance placed on various soft skills for accounting and finance professionals, which can help take the company's work to the next level.

For professionals looking to improve their work and their employability, the four soft skills listed below are most prominent.

Time management

Time management is an essential skill for any accounting professional because of not only how deadline-focused the profession is, but also because of the time management discipline required by the large-scale shift to remote work. It can be challenging to avoid procrastination, and it is easier to get off track when working virtually.

Because of accounting's cyclical nature, employees have ample opportunities to hone time management skills. Most significant projects and deliverables will happen at the same time of year, depending on the organization. Here are a few tips I have found to help develop time management skills and stay organized.

Start with leveraging calendars and tasks. Using the organization's digital tools can help move projects along and keep them organized. For example, if working within a team setting, use a shared spreadsheet with colleagues to track each person's responsibilities for month-end close or whatever project the team has prioritized. For sole practitioners, diligently using a calendar can help with keeping on task and meeting deadlines.

Another way to develop time management skills is by talking to managers and colleagues. Ask how they keep their tasks aligned. They might be planning their days in a way that can work with other projects and tasks. CPAs who demonstrate good time management have a leg up both for new employment opportunities and for promotions within their organization.

Critical thinking

Various hiring managers we work with often request that candidates have "strong critical-thinking skills," but what does that mean for the accounting and finance profession? Critical thinking — analyzing problems and finding the causes and solutions to those problems — is a major facet of the accounting profession.

Organizations are constantly facing new financial challenges. Most recently, COVID-19 created a range of challenges for accounting and finance teams to solve. Reallocating funds and cash management, managing payroll changes, reacting to new legal changes to internal reporting practices, and other changes required employees to think critically and creatively to meet organizational needs.

While COVID-19 was unexpected, there are other challenges accounting teams can plan for. What we are seeing most employers ask for is accounting and finance professionals who not only look at the problems of the past and find solutions, but who also can predict problems before they occur. From first glance to final analysis, accounting professionals should look at all the information they have and be able to communicate why something happened and what can be done in the future to plan or account for it.

When working to develop critical thinking skills, I've found it extremely important to first question how and why processes are done the way they are and ask how they can be done better. This "professional skepticism" and general curiosity can help ensure accuracy across all tasks. Professional skepticism will make it easier to ask the right questions and find the "why" instead of just trusting information at face value.

Leveraging other successful accounting professionals' advice can hone critical thinking skills and make any accounting professional a stronger asset to their organization. Webinars, conferences, and networking with other accounting professionals can give insight into what other organizations are doing and offer vendor recommendations, process improvements, and more.

Our recruiters regularly see communication as a top skill for accounting and finance talent. Nearly every function of an organization interacts with the accounting and finance teams. Therefore, professionals need to have exceptional communication skills, both written and verbal. Important projects need to be communicated in an easy-to-understand way to executives and colleagues (especially if they are unfamiliar with accounting or finance terminology) to ensure proper completion.

If accounting and finance professionals have poor communication skills, making clear points, sharing their reports and creating action items from the findings can be difficult.

When working to develop strong communication skills, reach out to a manager for feedback. Have them review emails, reports, and other communication before sending out or sharing.

Ask them if the communication gets the point across and if they believe the end user will understand the report or the solution being communicated. It's important to recognize who your audience is and the best way to present the information.

Avoid using too much jargon and ensure that anyone can understand the information, not just accounting professionals. Along with asking a manager for help, do a self-review of any communication. For written work, read it out loud to catch errors. Hearing versus reading something has a different impact. For oral communication, practice in advance so that the meeting's goal or call is adequately communicated.

Collaboration

Collaboration with teammates and other employees is paramount for accounting professionals. Since accounting and finance teams touch every area of the business, they are expected to work cross-functionally and collaborate well with other employees. Projects that involve other employees — like budgets, cash flow projections, or strategic planning — can be complicated and require a high degree of collaboration.

While entry-level accountants might not lead these projects with other company leaders, they will eventually be expected to meet with teams across the organization, so developing this skill now is crucial for continued growth. Even for sole practitioners who work relatively independently, collaboration is absolutely key while working with clients and any other stakeholders in various projects.

One way I've found helpful in practicing to become a stronger collaborator is spending time before a meeting writing down questions and thoughts to bring to the conversation. Make speaking up in meetings and calls a regular habit, and eventually, it'll become muscle memory. Preparing questions and engaging with the topic will encourage other team members to do the same and create more dialogue and collaboration in the discussions.

— Ryan Chabus , CPA, MBA, is the controller at LaSalle Network, a staffing, recruiting, and culture firm based in the US. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact Drew Adamek, a JofA senior editor, at [email protected] .

Where to find April’s flipbook issue

The Journal of Accountancy is now completely digital.

SPONSORED REPORT

Manage the talent, hand off the HR headaches

Recruiting. Onboarding. Payroll administration. Compliance. Benefits management. These are just a few of the HR functions accounting firms must provide to stay competitive in the talent game.

FEATURED ARTICLE

2023 tax software survey

CPAs assess how their return preparation products performed.

This site uses cookies, including third-party cookies, to improve your experience and deliver personalized content.

By continuing to use this website, you agree to our use of all cookies. For more information visit IMA's Cookie Policy .

Change username?

Create a new account, forgot password, sign in to myima.

Multiple Categories

Improving Critical Thinking Skills

November 01, 2021

By: Sonja Pippin , Ph.D., CPA ; Brett Rixom , Ph.D., CPA ; Jeffrey Wong , Ph.D., CPA

Whether working with financial statements, analyzing operational and nonfinancial information, implementing machine learning and AI processes, or carrying out many of their other varied responsibilities, accounting and finance professionals need to apply critical thinking skills to interpret the story behind the numbers.

Critical thinking is needed to evaluate complex situations and arrive at logical, sometimes creative, answers to questions. Informed judgments incorporating the ever-increasing amount of data available are essential for decision making and strategic planning.

Thus, creatively thinking about problems is a core competency for accounting and finance professionals—and one that can be enhanced through effective training. One such approach is through metacognition. Training that employs a combination of both creative problem solving (divergent thinking) and convergence on a single solution (convergent thinking) can lead financial professionals to create and choose the best interpretations for phenomena observed and how to best utilize the information going forward. Employees at any level in the organization, from newly hired staff to those in the executive ranks, can use metacognition to improve their critical assessment of results when analyzing data.

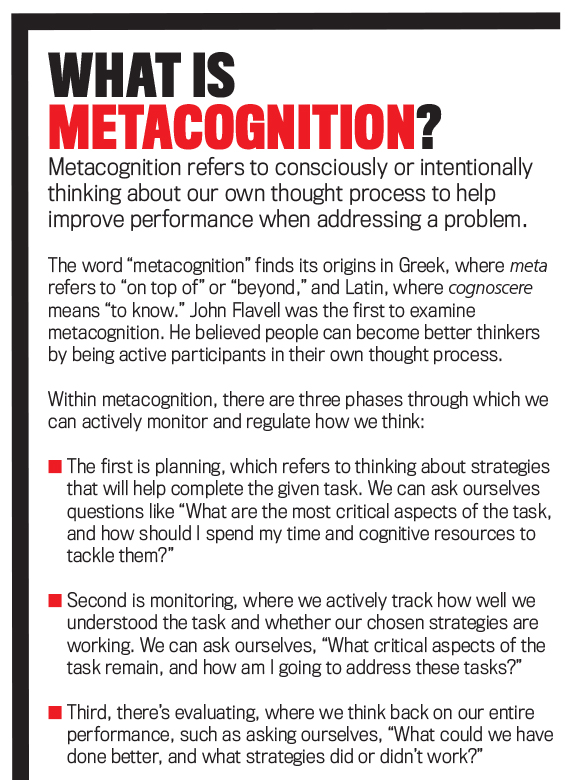

THINKING ABOUT THINKING

Metacognition refers to individuals’ ability to be aware, understand, and purposefully guide how to think about a problem (see “What Is Metacognition?”). It’s also been described as “thinking about thinking” or “knowing about knowing” and can lead to a more careful and focused analysis of information. Metacognition can be thought about broadly as a way to improve critical thinking and problem solving.

In their article “Training Auditors to Perform Analytical Procedures Using Metacognitive Skills,” R. David Plumlee, Brett Rixom, and Andrew Rosman evaluated how different types of thinking can be applied to a variety of problems, such as the results of analytical procedures, and how those types of thinking can help auditors arrive at the correct explanation for unexpected results that were found ( The Accounting Review , January 2015). The training methods they describe in their study, based on the psychological research examining metacognition, focus on applying divergent and convergent thinking.

While they employed settings most commonly encountered by staff in an audit firm, their approach didn’t focus on methods used solely by public accountants. Therefore, the results can be generalized to professionals who work with all types of financial and nonfinancial data. It’s particularly helpful for those conducting data analysis.

Their approach involved a sequential process of divergent thinking followed by convergent thinking. Divergent thinking refers to creating multiple reasons about what could be causing the surprising or unusual patterns encountered when analyzing data before a definitive rationale is used to inform what actions to take or strategy to use. Here’s an example of divergent thinking:

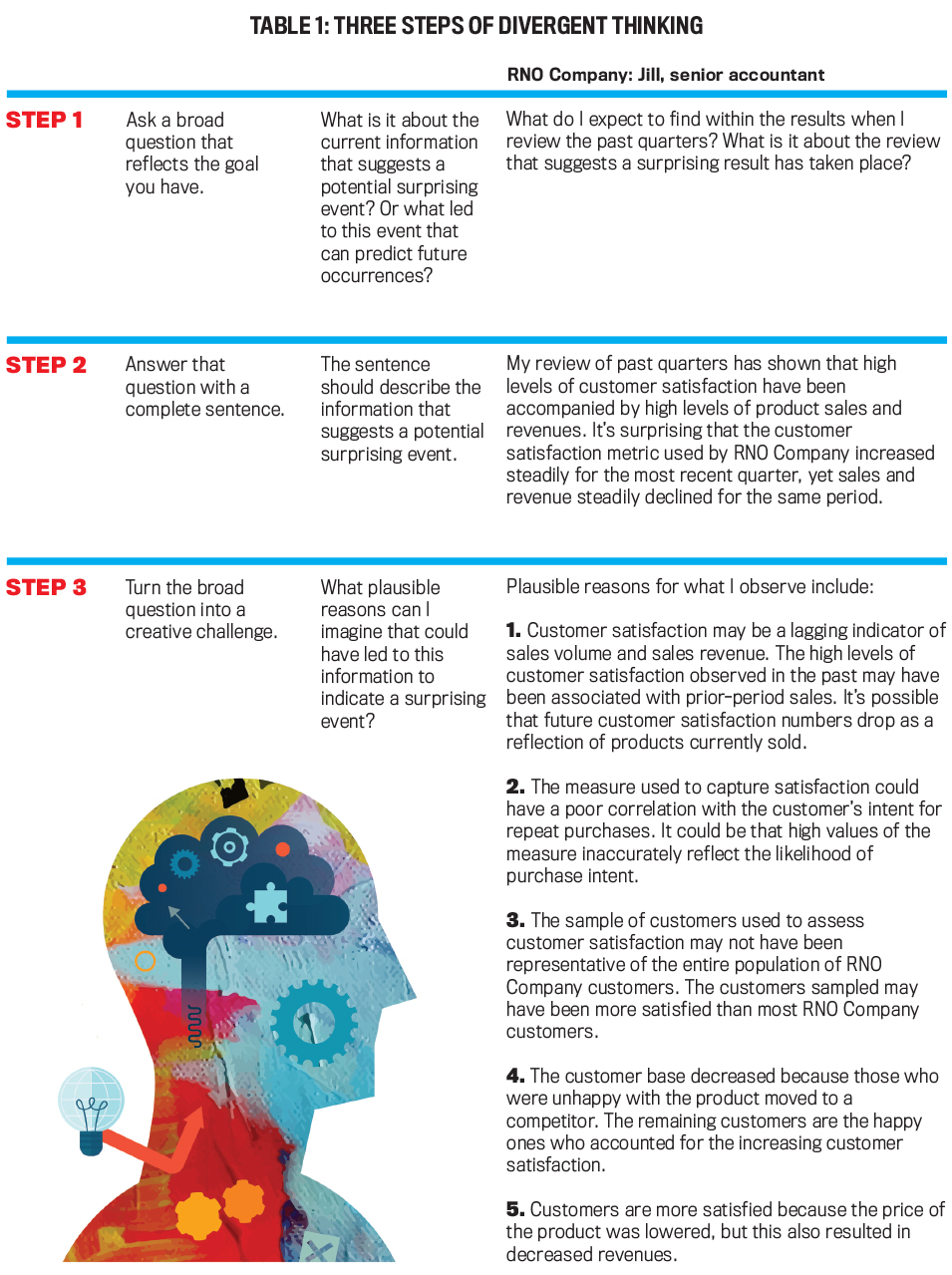

The customer satisfaction metric employed by RNO Company has increased steadily for the quarter, yet its sales numbers and revenue have declined steadily for the same period. Jill, a senior accountant, conducted ratio and trend analyses and found some of the results to be unusual. To apply divergent thinking, Jill would think of multiple potential reasons for this surprising result before removing any reason from consideration.

Convergent thinking is the process of finding the best explanation for the surprising results so that potential actions can be explored accordingly. The process consists of narrowing down the different reasons by ensuring the only reasons that are kept for consideration are ones that explain all of the surprising patterns seen in the results without explaining more than what is needed. In this way, actions can be taken to address the heart of any problems found instead of just the symptoms. On the other hand, if the surprising result is beneficial to an organization, it can make it easier to take the correct actions to replicate the benefit in other aspects of the business. Here’s an example of convergent thinking:

Washoe, Inc.’s customer satisfaction metric has increased steadily for the quarter, yet sales numbers and revenue have steadily declined for the same period. Roberto found this result to be surprising. After employing divergent thinking to identify 10 potential reasons for this result, such as “the reason that customers seem more satisfied is that the price of goods has been reduced, which also explains the reduction in sales revenue.” To apply convergent thinking, Roberto reviewed each reason that best fit. If the reason doesn’t explain the unusual results satisfactorily, then it will either be modified or discarded. For example, the reduced price of goods doesn’t explain all of the results—specifically, the decrease in units sold—so it needs to either be eliminated as a possible explanation or modified until it does explain all the results.

Exploring strategic or corrective actions based on reasons that completely explain the unusual results increases the chance of correctly addressing the actual issue behind the surprising result. Also, by making sure that the reason doesn’t contain extraneous details, unneeded actions can be avoided.

It’s important to note that a sequential process is required for these types of thinking to be most effective. When encountering a surprising or unexpected result during data analysis, accounting professionals must first focus strictly on divergent thinking—thinking about potential reasons—before using convergent thinking to choose a reason that best explains the surprising result. If convergent thinking is used before divergent thinking is completed, it can lead to reasons being picked simply because they came to mind right away.

LEARNING THE PROCESS

Improving divergent and convergent thinking can benefit employees at any level of an organization. Newer professionals who don’t have as much technical knowledge and experience to draw upon may be more likely to focus on the first explanation that comes to mind (“premature convergent thinking”) without fully considering all of the potential reasons for the surprising results. Experienced individuals such as CFOs and controllers have more technical knowledge and practical experience to rely on, but it’s possible these seasoned employees fall into habits and follow past patterns of thought without fully exploring potential causes for surprising results.

Instructing all accounting professionals on how to think about surprising results can help them have a more complete understanding of the issues at hand that will help guide actions taken in the future. It can lead to a more creative approach when analyzing information and ultimately to better problem solving.

When teaching employees to use divergent and convergent thinking, the goal is to get them to focus on what should be done once they identify information that suggests a surprising result has occurred. The first step is to learn how to properly use divergent thinking to create a set of plausible explanations more likely to contain the actual reason for the surprising results. There’s a three-step method that individuals can follow (see Table 1):

- Ask a broad question that reflects the goal you have: For instance, what is it about the current information that suggests a potential surprising event? Or what led to this event that can help predict future occurrences?

- Answer that question with a complete sentence: Be sure the answer includes a description of the information that suggests a potential surprising event.

- Turn the broad question into a creative challenge: Identify the plausible reasons that could have led to the indications of a surprising event.

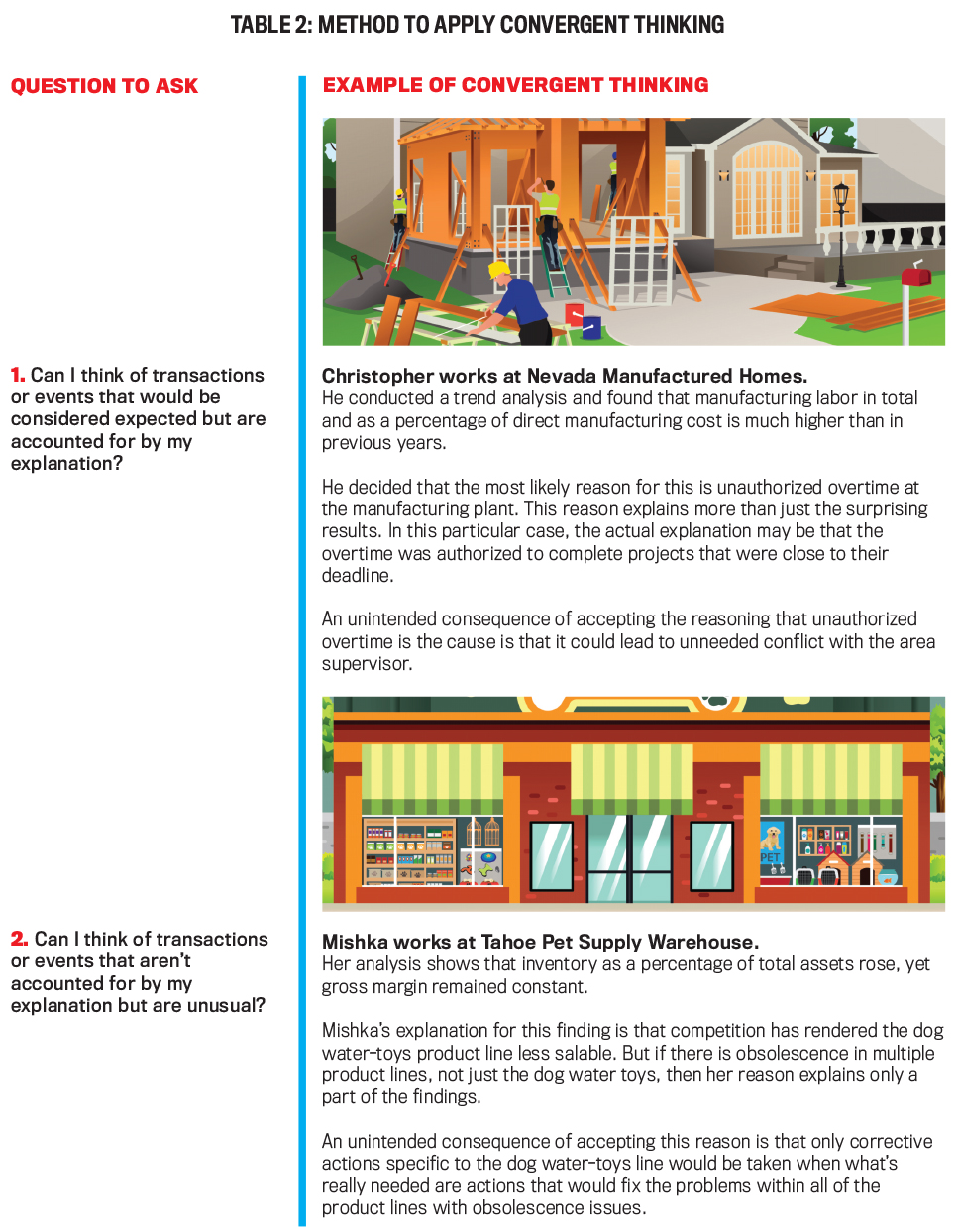

Once employees have a good grasp of how to use divergent thinking, the next step is to instruct them in the proper use of convergent thinking, which involves choosing the best possible reason from the ones identified during the divergent thinking process. Potential reasons need to be narrowed down by removing or modifying those that either don’t fully explain the surprising results or that overexplain the results.

Two simple questions can help individuals screen each of the possible explanations generated in the divergent thinking process (see Table 2):

- Can I think of transactions or events that would be considered expected but are accounted for by my explanation?

- Can I think of transactions or events that aren’t accounted for by my explanation but are unusual?

The first question is designed for an individual to think about whether there are other events outside of the current issue that fit the explanation: “Does the explanation also address phenomena that aren’t related to or outside the scope of the surprising result that’s being studied?” If the answer is “yes,” then this is a case of overexplanation. Consider, for example, a scenario involving an increase in bad debts. Relaxing credit requirements may explain the increase, but they would also explain a growth in sales and falling employee morale due to working massive amounts of overtime to make products for sale.

The second question is designed to think about whether an explanation only accounts for part of the phenomenon being observed: “Does the explanation address only part of what’s being observed while leaving other important details unexplained?” If the answer is “yes,” then it’s an under-explanation. For example, consider a decline in sales. An economic downturn at the same time as the decline may be a possible explanation, but it might only be part of the problem. A drop in product quality or a drop in demand due to obsolescence could also be causing sales to decline.

If the answer to either screening question is “yes,” then the explanation needs to be discarded from consideration or modified to better address the concern. In the case of over-explanation, the reason is too general and may lead to action areas where none is needed while still not addressing the actual issue. For underexplanation, the reason is incomplete because it accounts for only a portion of the phenomenon observed, thus action may only address a symptom and not the actual root problem.

If the answer to both questions is “no,” then the explanation is viable. The chosen reason neither overexplains nor underexplains the issue at hand, making it more likely that the recommended solution or plan of action based on that reason will be more successful at addressing the actual cause of the issue.

Divergent and convergent thinking are two distinct processes that work in conjunction with each other to arrive at potential reasons for the results they observe. Yet, as previously noted, the two ways of thinking must be conducted separately and sequentially in order to obtain optimal results. Divergent thinking must be applied first in order to achieve a diverse set of potential reasons. This will maximize the probability of generating a feasible reason that explains the results correctly. After the set of potential reasons has been generated using the divergent thinking approach, convergent thinking should be used to methodically remove or modify the reasons that don’t fit with the surprising results.

If both divergent thinking and convergent thinking are done simultaneously, premature convergence can lead to a less-than-optimal reason being chosen, which may lead to taking the wrong course of action. Thus, it’s important with training to instruct employees in the use of both divergent thinking and convergent thinking and to use the types of thinking sequentially.

ORGANIZATIONAL TRAINING

Learning to apply divergent and convergent thinking can require a substantial time commitment. The process we’ve described here is designed to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills. It outlines a general approach that doesn’t provide specific guidance on the best methods to analyze data or complete a task but rather focuses on successful methods to think of a diverse set of reasons for any surprising results and then how to choose the best explanation for that result in order to be able to recommend the most appropriate actions or solutions.

Individuals can practice the approach we’ve described on their own, but each organization will likely have its own preferred way to approach the analyses. Plumlee, et al., used training modules in their study that could be employed in a concerted effort by a company, with supervisors training their employees. We estimate that a basic training session would take about two hours. Complete training with practice and feedback would require about four hours—which could grow longer with even more for intensive training.

One area where this training could be very effective in helping employees is data analytics. In the past decade, an increasing amount of accounting and financial work involves or relies on data analysis. Data availability has increased exponentially, and companies use or have developed software that generates sophisticated analytical results.

Typical data analysis procedures accounting professionals might be called on to perform include things such as ratio and trend analyses, which compare financial and nonfinancial data over time and against industry information to examine whether results achieved are in line with expectations for strategic actions. Additionally, analyses are forward-looking when performance measures examined are leading indicators.

In order to perform data analytics effectively, accounting professionals must exercise sufficient judgment to critically assess the implications of any surprising results that are found. The quality of judgments and understanding the best ways to conduct and interpret the information uncovered by data analytics have typically been a function of time spent on the job along with training. At the same time, however, it’s commonplace that many of these analyses are performed by newer professionals.

Training in metacognition will help these employees more effectively and creatively reach conclusions about what they’ve observed in their analysis. Since the method discussed provides general instruction, each organization can customize the approach to best fit its own operations, strategies, and goals. Implementing a training program can be worth the investment given the importance of critical thinking throughout the process of evaluating operating results. Avoiding potential failures with interpreting results that could be prevented would seem to warrant the consideration of metacognitive training.

About the Authors

November 2021

- Strategy, Planning & Performance

- Business Acumen & Operations

- Decision Analysis

- Operational Knowledge

Publication Highlights

Lessons from an Agile Product Owner

Explore more.

Copyright Footer Message

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

Critical Thinking in Professional Accounting Practice: Conceptions of Employers and Practitioners

Cite this chapter.

- Samantha Sin ,

- Alan Jones &

- Zijian Wang

4868 Accesses

5 Citations

Over the past three decades or so it has become commonplace to lament the failure of universities to equip accounting graduates with the attributes and skills or abilities required for professional accounting practice, particularly as the latter has had to adapt to the demands of a rapidly changing business environment. With the aid of academics, professional accounting bodies have developed lists of competencies, skills, and attributes considered necessary for successful accounting practice. Employers have on the whole endorsed these lists. In this way “critical thinking” has entered the lexicon of both accountants and their employers, and when employers are asked to rank a range of named competencies in order of importance, critical thinking or some roughly synonymous term is frequently ranked highly, often at the top or near the top of their list of desirables (see, for example, Albrecht and Sack 2000). Although practical obstacles, such as content-focused curricula, have emerged to the inclusion of critical thinking as a learning objective in tertiary-level accounting courses, the presence of these obstacles has not altered “the collective conclusion from the accounting profession that critical thinking skills are a prerequisite for a successful accounting career and that accounting educators should assist students in the development of these skills” (Young and Warren 2011, 859). However, a problem that has not yet been widely recognized may lie in the language used to survey accountants and their employers, who may not be comfortable or familiar with the abstract and technicalized pedagogical discourse, for instance, the use of the phrase “developing self-regulating critical reflective capacities for sustainable feedback,” in which much skills talk is couched.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Accounting Education Change Commission. 1990. “Objectives of Education for Accountants: Position Statement Number One.” Issues in Accounting Education 5 (2): 307–312.

Google Scholar

Albrecht, W., and Sack, R. 2000. “Accounting Education: Charting the Course through a Perilous Future.” Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association.

American Accounting Association. 1986. “Future Accounting Education: Preparing for the Expanding Profession, Bedford Report.” Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. 1999. “ CPA Vision Project: 2011 and Beyond.” New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants.

Baril, C., Cunningham, B., Fordham, D., Gardner, R., and Wolcott, S. 1998. “Critical Thinking in the Public Accounting Profession: Aptitudes and Attitudes.” Journal of Accounting Education 16 (3–4): 381–406.

Article Google Scholar

Barnett, R. 1997. Higher Education: A Critical Business . Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and the Open University Press.

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. 1987. The Psychology of Written Composition . Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Big Eight Accounting Firms. 1989. “Perspectives on Education: Capabilities for Success in the Accounting Profession (White Paper).” New York: American Accounting Association.

Birkett, W. 1993. “Competency Based Standards for Professional Accountants in Australia and New Zealand.” Melbourne: ASCPA and ICAA.

Bloom, B., Engelhart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., and Krathwohl, D. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I: Cognitive Domain . Vol. 19: New York: David McKay.

Bui, B., and Porter, B. 2010. “The Expectation-Performance Gap in Accounting Education: An Exploratory Study.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 19 (1–2): 23–50.

Camp, J., and Schnader, A. 2010. “Using Debate to Enhance Critical Thinking in the Accounting Classroom: The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and US Tax Policy.” Issues in Accounting Education 25 (4): 655–675.

CPA Australia and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia. 2012. “Professional Accreditation Guidelines for Australian Accounting Degrees.” Melbourne and Sydney: CPA Australia and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia.

Craig, R., and McKinney, C. 2010. “A Successful Competency-Based Writing Skills Development Programme: Results of an Experiment.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 19 (3): 257–278.

Deal, K. 2004. “The Relationship between Critical Thinking and Interpersonal Skills: Guidelines for Clinical Supervision.” The Clinical Supervisor 22 (2): 3–19.

Doney, L., Lephardt, N., and Trebby, J. 1993. “Developing Critical Thinking Skills in Accounting Students.” Journal of Education for Business 68 (5): 297–300.

Dunn, D., and Smith, R. 2008. “Writing as Critical Thinking.” In Teaching Critical Thinking in Psycholog y: A Handbook of Best Practices , edited by D. S. Dunn, J. S. Halonen, and R. A. Smith, 1st ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. 163–174.

Chapter Google Scholar

Entwistle, N. 1994. Teaching and Quality of Learning: What Can Research and Development Offer to Policy and Practice in Higher Education . London: Society for Research into Higher Education.

Facione, P. 1990. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction, “The Delphi Report.” Millbrae, CA: American Philosophical Association, The California Academic Press.

Facione, P., Facione, N., and Giancario, C. 1997. Professional Judgement and the Disposition towards Critical Thinking . Millbrae, CA: Californian Academic Press.

Facione, P., Sanchez, C. A., Facione, N. C., and Gainen, J. 1995. “The Disposition toward Critical Thinking.” The Journal of General Education 44 (1): 1–25.

Flower, L., and Hayes, J. 1984. “Images, Plans, and Prose: The Representation of Meaning in Writing.” Written Communication 1 (1): 120–160.

Freeman, M., Hancock, P., Simpson, L., Sykes, C., Petocz, P., Densten, I., and Gibson, K. 2008. “Business as Usual: A Collaborative and Inclusive Investigation of the Existing Resources, Strengths, Gaps and Challenges to Be Addressed for Sustainability in Teaching and Learning in Australian University Business Faculties.” Scoping Report, Australian Business Deans Council. http://www.olt.gov.au /project-business-usual-collaborative-sydney-2006.

Galbraith, M. 1998. Adult Learning Methods: A Guide for Effective Instruction . Washington, DC: ERIC Publications.

Giancarlo, C., and Facione, P. 2001. “A Look across Four Years at the Disposition toward Critical Thinking among Undergraduate Students.” The Journal of General Education 50 (1): 29–55.

Hancock, P., Howieson, B., Kavanagh, M., Kent, J., Tempone, I., and Segal, N. 2009. “Accounting for the Future: More Than Numbers, Final Report.” Strawberry Hills: Australian Learning and Teaching Council Ltd. http://www.altc.edu.au .

Hayes, J., and Flower, L. 1987. “On the Structure of the Writing Process.” Topics in Language Disorders 7 (4): 19–30.

Hyland, K. 2005. “Stance and Engagement: A Model of Interaction in Academic Discourse.” Discourse Studies 7 (2): 173–192.

Jackson, M., Watty, K., Yu, L., and Lowe, L. 2006. “Assessing Students Unfamiliar with Assessment Practices in Australian Universities, Final Report.” Strawberry Hills: Australian Learning and Teaching Council Ltd.

Jones, A. 2010. “Generic Attributes in Accounting: The Significance of the Disciplinary Context.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 19 (1–2): 5–21.

Jones, A., and Sin, S. 2003. Generic Skills in Accounting: Competencies for Students and Graduates . Sydney: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Jones, A., and Sin, S. 2004. “Integrating Language with Content in First Year Accounting: Student Profiles, Perceptions and Performance.” In Integrating Content and Language: Meeting the Challenge of a Multilingual Higher Education , edited by R. Wilkinsoned. Maastricht: Maastricht University Press.

Jones, A., and Sin, S. 2013. “Achieving Professional Trustworthiness: Communicative Expertise and Identity Work in Professional Accounting Practice.” In Discourses of Ethics , edited by C. Candlin and J. Crichtoned. Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kavanagh, M., and Drennan, L. 2008. “What Skills and Attributes Does an Accounting Graduate Need? Evidence from Student Perceptions and Employer Expectations.” Accounting and Finance 48 (2): 279–300.

Kimmel, P. 1995. “A Framework for Incorporating Critical Thinking into Accounting Education.” Journal of Accounting Education 13 (3): 299–318.

King, P., and Kitchener, K. 2004. “Reflective Judgment: Theory and Research on the Development of Epistemic Assumptions through Adulthood.” Educational Psychologist 39 (1): 5–18.

Kurfiss, J. 1988. Critical Thinking: Theory, Research, Practice and Possibilities . Washington: ASHE-Eric Higher Education Report No. 2, Associate for the Study of Higher Education.

Kurfiss, J. 1989. “Helping Faculty Foster Students’ Critical Thinking in the Disciplines.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 37 (1): 41–50.

Lucas, U. 2008. “Being “Pulled up Short”: Creating Moments of Surprise and Possibility in Accounting Education.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 19 (3): 383–403

Menary, R. 2007. “Writing as Thinking.” Language Sciences 29 (5): 621–632.

Metlay, D., and Sarewitz, D. 2012. “Decision Strategies for Addressing Complex, “Messy” Problems.” The Bridge on Social Sciences and Engineering Practice 42 (3): 6–16.

Mezirow, J. 2000. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectivesona Theory in Progress . The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series, Washington, DC: ERIC Publications.

Morgan, G. 1988. “Accounting as Reality Construction: Towards a New Epistemology for Accounting Practice.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 13 (5): 477–485.

Partnership for Public Service and Institute for Public Policy Implementation. 2007. The Best Places to Work in the Federal Government . Washington, DC: American University.

Paul, R. 1989. Critical Thinking Handbook: High School. A Guide for Redesigning Instruction . Washington, DC: ERIC Publications.

Sarangi, S., and Candlin, C. 2010. “Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice: Mapping a Future Agenda.” Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice 7 (1): 1–9.

Serrat, O. 2011. Critical Thinking . Washington, DC: Asian Development Bank.

Simon, H. 1974. “The Structure of Ill Structured Problems.” Artificial Intelligence 4 (3): 181–201.

Sin, S. 2010. “Considerations of Quality in Phenomenographic Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods no. 9 (4): 305–319.

Sin, S. 2011. An Investigation of Practitioners’ and Students’ Conceptions of Accounting Work . Linköping: Linköping University Press.

Sin, S., Jones, A., and Petocz, P. 2007. “Evaluating a Method of Integrating Generic Skills with Accounting Content Based on a Functional Theory of Meaning.” Accounting and Finance 47 (1): 143–163.

Sin, S., Reid, A., and Dahlgren, L. 2011. “The Conceptions of Work in the Accounting Profession in the Twenty-First Century from the Experiences of Practitioners.” Studies in Continuing Education 33 (2): 139–156.

Tempone, I., and Martin, E. 2003. “Iteration between Theory and Practice as a Pathway to Developing Generic Skills in Accounting.” Accounting Education: An International Journal 12 (3): 227–244.

Thompson, J., and Tuden, A. 1959. “Strategies, Structures, and Processes of Organizational Decision.” In Comparative Studies in Administration edited by J. Thompson, P. Hammond, R. Hawkes, B. Junker, and A. Tudened. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. 195–216.

van Peursem, K. 2005. “Conversations with Internal Auditors: The Power of Ambiguity.” Managerial Auditing Journal 20 (5): 489–512.

Wang, F. 2007. Conceptions of Critical Thinking Skills in Accounting from the Perspective of Accountants in Their First Year of Experience in the Profession , Macquarie University Honours Thesis.

Watson, T. 2004. “Managers, Managism, and the Tower of Babble: Making Sense of Managerial Pseudojargon.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language (166): 67–82.

White, L. 2003. Second Language Acquisition and Universal Grammar . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Young, M., and Warren, D. 2011. “Encouraging the Development of Critical Thinking Skills in the Introductory Accounting Courses Using the Challenge Problem Approach.” Issues in Accounting Education 26 (4): 859–881.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Copyright information.

© 2015 Martin Davies and Ronald Barnett

About this chapter

Sin, S., Jones, A., Wang, Z. (2015). Critical Thinking in Professional Accounting Practice: Conceptions of Employers and Practitioners. In: Davies, M., Barnett, R. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137378057_26

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137378057_26

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-47812-5

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-37805-7

eBook Packages : Palgrave Education Collection Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, critical thinking in accounting education: processes, skills and applications.

Managerial Auditing Journal

ISSN : 0268-6902

Article publication date: 1 October 1997

Explains that many prestigious bodies, including the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business and the Accounting Change Commission, have asked accounting educators to improve their students’ critical thinking skills. Suggests that the literature contains few examples of how to apply such skills in an accounting environment and how to teach such skills as efficiently as possible. Explains and provides examples of such critical thinking skills. Shows how to incorporate such skills in the classroom.

- Thinking styles

Reinstein, A. and Bayou, M.E. (1997), "Critical thinking in accounting education: processes, skills and applications", Managerial Auditing Journal , Vol. 12 No. 7, pp. 336-342. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686909710180698

Copyright © 1997, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

41+ Critical Thinking Examples (Definition + Practices)

Critical thinking is an essential skill in our information-overloaded world, where figuring out what is fact and fiction has become increasingly challenging.

But why is critical thinking essential? Put, critical thinking empowers us to make better decisions, challenge and validate our beliefs and assumptions, and understand and interact with the world more effectively and meaningfully.

Critical thinking is like using your brain's "superpowers" to make smart choices. Whether it's picking the right insurance, deciding what to do in a job, or discussing topics in school, thinking deeply helps a lot. In the next parts, we'll share real-life examples of when this superpower comes in handy and give you some fun exercises to practice it.

Critical Thinking Process Outline

Critical thinking means thinking clearly and fairly without letting personal feelings get in the way. It's like being a detective, trying to solve a mystery by using clues and thinking hard about them.

It isn't always easy to think critically, as it can take a pretty smart person to see some of the questions that aren't being answered in a certain situation. But, we can train our brains to think more like puzzle solvers, which can help develop our critical thinking skills.

Here's what it looks like step by step:

Spotting the Problem: It's like discovering a puzzle to solve. You see that there's something you need to figure out or decide.

Collecting Clues: Now, you need to gather information. Maybe you read about it, watch a video, talk to people, or do some research. It's like getting all the pieces to solve your puzzle.

Breaking It Down: This is where you look at all your clues and try to see how they fit together. You're asking questions like: Why did this happen? What could happen next?

Checking Your Clues: You want to make sure your information is good. This means seeing if what you found out is true and if you can trust where it came from.

Making a Guess: After looking at all your clues, you think about what they mean and come up with an answer. This answer is like your best guess based on what you know.

Explaining Your Thoughts: Now, you tell others how you solved the puzzle. You explain how you thought about it and how you answered.

Checking Your Work: This is like looking back and seeing if you missed anything. Did you make any mistakes? Did you let any personal feelings get in the way? This step helps make sure your thinking is clear and fair.

And remember, you might sometimes need to go back and redo some steps if you discover something new. If you realize you missed an important clue, you might have to go back and collect more information.

Critical Thinking Methods

Just like doing push-ups or running helps our bodies get stronger, there are special exercises that help our brains think better. These brain workouts push us to think harder, look at things closely, and ask many questions.

It's not always about finding the "right" answer. Instead, it's about the journey of thinking and asking "why" or "how." Doing these exercises often helps us become better thinkers and makes us curious to know more about the world.

Now, let's look at some brain workouts to help us think better:

1. "What If" Scenarios

Imagine crazy things happening, like, "What if there was no internet for a month? What would we do?" These games help us think of new and different ideas.

Pick a hot topic. Argue one side of it and then try arguing the opposite. This makes us see different viewpoints and think deeply about a topic.

3. Analyze Visual Data

Check out charts or pictures with lots of numbers and info but no explanations. What story are they telling? This helps us get better at understanding information just by looking at it.

4. Mind Mapping

Write an idea in the center and then draw lines to related ideas. It's like making a map of your thoughts. This helps us see how everything is connected.

There's lots of mind-mapping software , but it's also nice to do this by hand.

5. Weekly Diary

Every week, write about what happened, the choices you made, and what you learned. Writing helps us think about our actions and how we can do better.

6. Evaluating Information Sources

Collect stories or articles about one topic from newspapers or blogs. Which ones are trustworthy? Which ones might be a little biased? This teaches us to be smart about where we get our info.

There are many resources to help you determine if information sources are factual or not.

7. Socratic Questioning

This way of thinking is called the Socrates Method, named after an old-time thinker from Greece. It's about asking lots of questions to understand a topic. You can do this by yourself or chat with a friend.

Start with a Big Question:

"What does 'success' mean?"

Dive Deeper with More Questions:

"Why do you think of success that way?" "Do TV shows, friends, or family make you think that?" "Does everyone think about success the same way?"

"Can someone be a winner even if they aren't rich or famous?" "Can someone feel like they didn't succeed, even if everyone else thinks they did?"

Look for Real-life Examples:

"Who is someone you think is successful? Why?" "Was there a time you felt like a winner? What happened?"

Think About Other People's Views:

"How might a person from another country think about success?" "Does the idea of success change as we grow up or as our life changes?"

Think About What It Means:

"How does your idea of success shape what you want in life?" "Are there problems with only wanting to be rich or famous?"

Look Back and Think:

"After talking about this, did your idea of success change? How?" "Did you learn something new about what success means?"

8. Six Thinking Hats

Edward de Bono came up with a cool way to solve problems by thinking in six different ways, like wearing different colored hats. You can do this independently, but it might be more effective in a group so everyone can have a different hat color. Each color has its way of thinking:

White Hat (Facts): Just the facts! Ask, "What do we know? What do we need to find out?"

Red Hat (Feelings): Talk about feelings. Ask, "How do I feel about this?"

Black Hat (Careful Thinking): Be cautious. Ask, "What could go wrong?"

Yellow Hat (Positive Thinking): Look on the bright side. Ask, "What's good about this?"

Green Hat (Creative Thinking): Think of new ideas. Ask, "What's another way to look at this?"

Blue Hat (Planning): Organize the talk. Ask, "What should we do next?"

When using this method with a group:

- Explain all the hats.

- Decide which hat to wear first.

- Make sure everyone switches hats at the same time.

- Finish with the Blue Hat to plan the next steps.

9. SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is like a game plan for businesses to know where they stand and where they should go. "SWOT" stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

There are a lot of SWOT templates out there for how to do this visually, but you can also think it through. It doesn't just apply to businesses but can be a good way to decide if a project you're working on is working.

Strengths: What's working well? Ask, "What are we good at?"

Weaknesses: Where can we do better? Ask, "Where can we improve?"

Opportunities: What good things might come our way? Ask, "What chances can we grab?"

Threats: What challenges might we face? Ask, "What might make things tough for us?"

Steps to do a SWOT Analysis:

- Goal: Decide what you want to find out.

- Research: Learn about your business and the world around it.

- Brainstorm: Get a group and think together. Talk about strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

- Pick the Most Important Points: Some things might be more urgent or important than others.

- Make a Plan: Decide what to do based on your SWOT list.

- Check Again Later: Things change, so look at your SWOT again after a while to update it.

Now that you have a few tools for thinking critically, let’s get into some specific examples.

Everyday Examples

Life is a series of decisions. From the moment we wake up, we're faced with choices – some trivial, like choosing a breakfast cereal, and some more significant, like buying a home or confronting an ethical dilemma at work. While it might seem that these decisions are disparate, they all benefit from the application of critical thinking.

10. Deciding to buy something

Imagine you want a new phone. Don't just buy it because the ad looks cool. Think about what you need in a phone. Look up different phones and see what people say about them. Choose the one that's the best deal for what you want.

11. Deciding what is true

There's a lot of news everywhere. Don't believe everything right away. Think about why someone might be telling you this. Check if what you're reading or watching is true. Make up your mind after you've looked into it.

12. Deciding when you’re wrong

Sometimes, friends can have disagreements. Don't just get mad right away. Try to see where they're coming from. Talk about what's going on. Find a way to fix the problem that's fair for everyone.

13. Deciding what to eat

There's always a new diet or exercise that's popular. Don't just follow it because it's trendy. Find out if it's good for you. Ask someone who knows, like a doctor. Make choices that make you feel good and stay healthy.

14. Deciding what to do today

Everyone is busy with school, chores, and hobbies. Make a list of things you need to do. Decide which ones are most important. Plan your day so you can get things done and still have fun.

15. Making Tough Choices

Sometimes, it's hard to know what's right. Think about how each choice will affect you and others. Talk to people you trust about it. Choose what feels right in your heart and is fair to others.

16. Planning for the Future

Big decisions, like where to go to school, can be tricky. Think about what you want in the future. Look at the good and bad of each choice. Talk to people who know about it. Pick what feels best for your dreams and goals.

Job Examples

17. solving problems.

Workers brainstorm ways to fix a machine quickly without making things worse when a machine breaks at a factory.

18. Decision Making

A store manager decides which products to order more of based on what's selling best.

19. Setting Goals

A team leader helps their team decide what tasks are most important to finish this month and which can wait.

20. Evaluating Ideas

At a team meeting, everyone shares ideas for a new project. The group discusses each idea's pros and cons before picking one.

21. Handling Conflict

Two workers disagree on how to do a job. Instead of arguing, they talk calmly, listen to each other, and find a solution they both like.

22. Improving Processes

A cashier thinks of a faster way to ring up items so customers don't have to wait as long.

23. Asking Questions

Before starting a big task, an employee asks for clear instructions and checks if they have the necessary tools.

24. Checking Facts

Before presenting a report, someone double-checks all their information to make sure there are no mistakes.

25. Planning for the Future

A business owner thinks about what might happen in the next few years, like new competitors or changes in what customers want, and makes plans based on those thoughts.

26. Understanding Perspectives

A team is designing a new toy. They think about what kids and parents would both like instead of just what they think is fun.

School Examples

27. researching a topic.

For a history project, a student looks up different sources to understand an event from multiple viewpoints.

28. Debating an Issue

In a class discussion, students pick sides on a topic, like school uniforms, and share reasons to support their views.

29. Evaluating Sources

While writing an essay, a student checks if the information from a website is trustworthy or might be biased.

30. Problem Solving in Math

When stuck on a tricky math problem, a student tries different methods to find the answer instead of giving up.

31. Analyzing Literature

In English class, students discuss why a character in a book made certain choices and what those decisions reveal about them.

32. Testing a Hypothesis

For a science experiment, students guess what will happen and then conduct tests to see if they're right or wrong.

33. Giving Peer Feedback

After reading a classmate's essay, a student offers suggestions for improving it.

34. Questioning Assumptions

In a geography lesson, students consider why certain countries are called "developed" and what that label means.

35. Designing a Study

For a psychology project, students plan an experiment to understand how people's memories work and think of ways to ensure accurate results.

36. Interpreting Data

In a science class, students look at charts and graphs from a study, then discuss what the information tells them and if there are any patterns.

Critical Thinking Puzzles

Not all scenarios will have a single correct answer that can be figured out by thinking critically. Sometimes we have to think critically about ethical choices or moral behaviors.

Here are some mind games and scenarios you can solve using critical thinking. You can see the solution(s) at the end of the post.

37. The Farmer, Fox, Chicken, and Grain Problem

A farmer is at a riverbank with a fox, a chicken, and a grain bag. He needs to get all three items across the river. However, his boat can only carry himself and one of the three items at a time.

Here's the challenge:

- If the fox is left alone with the chicken, the fox will eat the chicken.

- If the chicken is left alone with the grain, the chicken will eat the grain.

How can the farmer get all three items across the river without any item being eaten?

38. The Rope, Jar, and Pebbles Problem

You are in a room with two long ropes hanging from the ceiling. Each rope is just out of arm's reach from the other, so you can't hold onto one rope and reach the other simultaneously.

Your task is to tie the two rope ends together, but you can't move the position where they hang from the ceiling.

You are given a jar full of pebbles. How do you complete the task?

39. The Two Guards Problem

Imagine there are two doors. One door leads to certain doom, and the other leads to freedom. You don't know which is which.

In front of each door stands a guard. One guard always tells the truth. The other guard always lies. You don't know which guard is which.

You can ask only one question to one of the guards. What question should you ask to find the door that leads to freedom?

40. The Hourglass Problem

You have two hourglasses. One measures 7 minutes when turned over, and the other measures 4 minutes. Using just these hourglasses, how can you time exactly 9 minutes?

41. The Lifeboat Dilemma

Imagine you're on a ship that's sinking. You get on a lifeboat, but it's already too full and might flip over.

Nearby in the water, five people are struggling: a scientist close to finding a cure for a sickness, an old couple who've been together for a long time, a mom with three kids waiting at home, and a tired teenager who helped save others but is now in danger.

You can only save one person without making the boat flip. Who would you choose?

42. The Tech Dilemma

You work at a tech company and help make a computer program to help small businesses. You're almost ready to share it with everyone, but you find out there might be a small chance it has a problem that could show users' private info.

If you decide to fix it, you must wait two more months before sharing it. But your bosses want you to share it now. What would you do?

43. The History Mystery

Dr. Amelia is a history expert. She's studying where a group of people traveled long ago. She reads old letters and documents to learn about it. But she finds some letters that tell a different story than what most people believe.

If she says this new story is true, it could change what people learn in school and what they think about history. What should she do?

The Role of Bias in Critical Thinking

Have you ever decided you don’t like someone before you even know them? Or maybe someone shared an idea with you that you immediately loved without even knowing all the details.

This experience is called bias, which occurs when you like or dislike something or someone without a good reason or knowing why. It can also take shape in certain reactions to situations, like a habit or instinct.

Bias comes from our own experiences, what friends or family tell us, or even things we are born believing. Sometimes, bias can help us stay safe, but other times it stops us from seeing the truth.

Not all bias is bad. Bias can be a mechanism for assessing our potential safety in a new situation. If we are biased to think that anything long, thin, and curled up is a snake, we might assume the rope is something to be afraid of before we know it is just a rope.

While bias might serve us in some situations (like jumping out of the way of an actual snake before we have time to process that we need to be jumping out of the way), it often harms our ability to think critically.

How Bias Gets in the Way of Good Thinking

Selective Perception: We only notice things that match our ideas and ignore the rest.

It's like only picking red candies from a mixed bowl because you think they taste the best, but they taste the same as every other candy in the bowl. It could also be when we see all the signs that our partner is cheating on us but choose to ignore them because we are happy the way we are (or at least, we think we are).

Agreeing with Yourself: This is called “ confirmation bias ” when we only listen to ideas that match our own and seek, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms what we already think we know or believe.

An example is when someone wants to know if it is safe to vaccinate their children but already believes that vaccines are not safe, so they only look for information supporting the idea that vaccines are bad.

Thinking We Know It All: Similar to confirmation bias, this is called “overconfidence bias.” Sometimes we think our ideas are the best and don't listen to others. This can stop us from learning.

Have you ever met someone who you consider a “know it”? Probably, they have a lot of overconfidence bias because while they may know many things accurately, they can’t know everything. Still, if they act like they do, they show overconfidence bias.

There's a weird kind of bias similar to this called the Dunning Kruger Effect, and that is when someone is bad at what they do, but they believe and act like they are the best .

Following the Crowd: This is formally called “groupthink”. It's hard to speak up with a different idea if everyone agrees. But this can lead to mistakes.

An example of this we’ve all likely seen is the cool clique in primary school. There is usually one person that is the head of the group, the “coolest kid in school”, and everyone listens to them and does what they want, even if they don’t think it’s a good idea.

How to Overcome Biases

Here are a few ways to learn to think better, free from our biases (or at least aware of them!).

Know Your Biases: Realize that everyone has biases. If we know about them, we can think better.

Listen to Different People: Talking to different kinds of people can give us new ideas.

Ask Why: Always ask yourself why you believe something. Is it true, or is it just a bias?

Understand Others: Try to think about how others feel. It helps you see things in new ways.

Keep Learning: Always be curious and open to new information.

In today's world, everything changes fast, and there's so much information everywhere. This makes critical thinking super important. It helps us distinguish between what's real and what's made up. It also helps us make good choices. But thinking this way can be tough sometimes because of biases. These are like sneaky thoughts that can trick us. The good news is we can learn to see them and think better.

There are cool tools and ways we've talked about, like the "Socratic Questioning" method and the "Six Thinking Hats." These tools help us get better at thinking. These thinking skills can also help us in school, work, and everyday life.

We’ve also looked at specific scenarios where critical thinking would be helpful, such as deciding what diet to follow and checking facts.

Thinking isn't just a skill—it's a special talent we improve over time. Working on it lets us see things more clearly and understand the world better. So, keep practicing and asking questions! It'll make you a smarter thinker and help you see the world differently.

Critical Thinking Puzzles (Solutions)

The farmer, fox, chicken, and grain problem.

- The farmer first takes the chicken across the river and leaves it on the other side.

- He returns to the original side and takes the fox across the river.

- After leaving the fox on the other side, he returns the chicken to the starting side.

- He leaves the chicken on the starting side and takes the grain bag across the river.

- He leaves the grain with the fox on the other side and returns to get the chicken.

- The farmer takes the chicken across, and now all three items -- the fox, the chicken, and the grain -- are safely on the other side of the river.

The Rope, Jar, and Pebbles Problem

- Take one rope and tie the jar of pebbles to its end.

- Swing the rope with the jar in a pendulum motion.

- While the rope is swinging, grab the other rope and wait.

- As the swinging rope comes back within reach due to its pendulum motion, grab it.

- With both ropes within reach, untie the jar and tie the rope ends together.

The Two Guards Problem

The question is, "What would the other guard say is the door to doom?" Then choose the opposite door.

The Hourglass Problem

- Start both hourglasses.

- When the 4-minute hourglass runs out, turn it over.

- When the 7-minute hourglass runs out, the 4-minute hourglass will have been running for 3 minutes. Turn the 7-minute hourglass over.

- When the 4-minute hourglass runs out for the second time (a total of 8 minutes have passed), the 7-minute hourglass will run for 1 minute. Turn the 7-minute hourglass again for 1 minute to empty the hourglass (a total of 9 minutes passed).

The Boat and Weights Problem

Take the cat over first and leave it on the other side. Then, return and take the fish across next. When you get there, take the cat back with you. Leave the cat on the starting side and take the cat food across. Lastly, return to get the cat and bring it to the other side.

The Lifeboat Dilemma

There isn’t one correct answer to this problem. Here are some elements to consider:

- Moral Principles: What values guide your decision? Is it the potential greater good for humanity (the scientist)? What is the value of long-standing love and commitment (the elderly couple)? What is the future of young children who depend on their mothers? Or the selfless bravery of the teenager?

- Future Implications: Consider the future consequences of each choice. Saving the scientist might benefit millions in the future, but what moral message does it send about the value of individual lives?

- Emotional vs. Logical Thinking: While it's essential to engage empathy, it's also crucial not to let emotions cloud judgment entirely. For instance, while the teenager's bravery is commendable, does it make him more deserving of a spot on the boat than the others?

- Acknowledging Uncertainty: The scientist claims to be close to a significant breakthrough, but there's no certainty. How does this uncertainty factor into your decision?

- Personal Bias: Recognize and challenge any personal biases, such as biases towards age, profession, or familial status.

The Tech Dilemma

Again, there isn’t one correct answer to this problem. Here are some elements to consider:

- Evaluate the Risk: How severe is the potential vulnerability? Can it be easily exploited, or would it require significant expertise? Even if the circumstances are rare, what would be the consequences if the vulnerability were exploited?

- Stakeholder Considerations: Different stakeholders will have different priorities. Upper management might prioritize financial projections, the marketing team might be concerned about the product's reputation, and customers might prioritize the security of their data. How do you balance these competing interests?

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Implications: While launching on time could meet immediate financial goals, consider the potential long-term damage to the company's reputation if the vulnerability is exploited. Would the short-term gains be worth the potential long-term costs?

- Ethical Implications : Beyond the financial and reputational aspects, there's an ethical dimension to consider. Is it right to release a product with a known vulnerability, even if the chances of it being exploited are low?

- Seek External Input: Consulting with cybersecurity experts outside your company might be beneficial. They could provide a more objective risk assessment and potential mitigation strategies.

- Communication: How will you communicate the decision, whatever it may be, both internally to your team and upper management and externally to your customers and potential users?

The History Mystery

Dr. Amelia should take the following steps:

- Verify the Letters: Before making any claims, she should check if the letters are actual and not fake. She can do this by seeing when and where they were written and if they match with other things from that time.

- Get a Second Opinion: It's always good to have someone else look at what you've found. Dr. Amelia could show the letters to other history experts and see their thoughts.

- Research More: Maybe there are more documents or letters out there that support this new story. Dr. Amelia should keep looking to see if she can find more evidence.

- Share the Findings: If Dr. Amelia believes the letters are true after all her checks, she should tell others. This can be through books, talks, or articles.

- Stay Open to Feedback: Some people might agree with Dr. Amelia, and others might not. She should listen to everyone and be ready to learn more or change her mind if new information arises.

Ultimately, Dr. Amelia's job is to find out the truth about history and share it. It's okay if this new truth differs from what people used to believe. History is about learning from the past, no matter the story.

Related posts:

- Experimenter Bias (Definition + Examples)

- Hasty Generalization Fallacy (31 Examples + Similar Names)

- Ad Hoc Fallacy (29 Examples + Other Names)

- Confirmation Bias (Examples + Definition)

- Equivocation Fallacy (26 Examples + Description)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Markets We Serve

Course ID: CTFAF

Critical thinking for accounting and finance.

No skill is more important in business today than the ability to understand, analyze, and act on information effectively and responsibly. Finance and Accounting professionals who are also savvy, sharp critical thinkers can cut through ambiguity and information overload to quickly zero in on what is really important. This session shares cognitive techniques and critical thinking tools to enhance decision-making under pressure and strengthen your impact.

Learning Objectives

Examine cognitive techniques and critical thinking tools to enhance decision-making under pressure and strengthen your impact

Major Topics

- Cognitive techniques

- Critical thinking tools

- Decision making under pressure

Who Should Attend

Leaders in an organization who want to improve their communication and critical thinking skills

Fields of Study

Prerequisites, cpe credits, this course is available for your group as:, let's roll.

To learn more or customize this course for your group, complete this form and a BLI team member will get back with you shortly.

Your browser is out-of-date!

Update your browser to view this website correctly.

Update my browser now

Improving the Critical Thinking Skills of Accounting Students

- Related Documents

A Framework and Resources to Create a Data Analytics-Infused Accounting Curriculum

The technology and Data Analytics developments affecting the accounting profession in turn have a profound effect on accounting curriculum. Accounting programs need fully-integrated accounting curriculum to develop students with strong analytic and critical thinking skills that complement their accounting knowledge. This will meet the profession's expectation that accounting students have expert level skills in both technical accounting knowledge and Data Analytics. This paper provides a framework and the resources for creating a Data Analytics-infused accounting curriculum. Specifically, using the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, we apply the theory's five stages to the infusion of Data Analytics into the accounting curriculum: Knowledge, Persuasion, Decision, Implementation, and Confirmation. We formulate an Analytics Value Cube to guide the use of different analytic techniques as accounting programs integrate. We recommend free tools, questions, and cases for use across the curriculum. While our focus is on accounting programs new to Data Analytics, these resources are also useful to accounting programs and practitioners that wish to expand their data analytic offerings.

Improving the Critical Thinking Skills of Accounting Students Using the Framework-Based Teaching Approach

The purpose of this paper is to examine how the Framework-based Teaching (FBT) approach improves the critical thinking skill among accounting students at tertiary education level. This qualitative study is conducted using the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL) approach, where reflections from lecturers ‘experience in teaching and learning process are gathered. Data are collected from both accounting lecturers and students who implemented the FBT approach using the inquiry-based learning technique in the financial accounting course. Data are analysed using content analysis. The results from the study indicate that, based on lecturers’ reflection, students are pushed to think in depth in classes using the inquiry based learning of the FBT approach. This is supported by students’ feedback on their own critical thinking ability. Thus, the FBT approach improves the critical thinking skills among accounting students. The implication of this study is the practicability of the FBT approach in teaching financial accounting course at university level in encouraging critical thinking skills.

Developing Critical Thinking Skills in Accounting Students

Facebook as a pedagogical tool in fostering students’ critical thinking skills.