Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This handout is intended to help you become more comfortable with the uses of and distinctions among quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. This handout compares and contrasts the three terms, gives some pointers, and includes a short excerpt that you can use to practice these skills.

What are the differences among quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing?

These three ways of incorporating other writers' work into your own writing differ according to the closeness of your writing to the source writing.

Quotations must be identical to the original, using a narrow segment of the source. They must match the source document word for word and must be attributed to the original author.

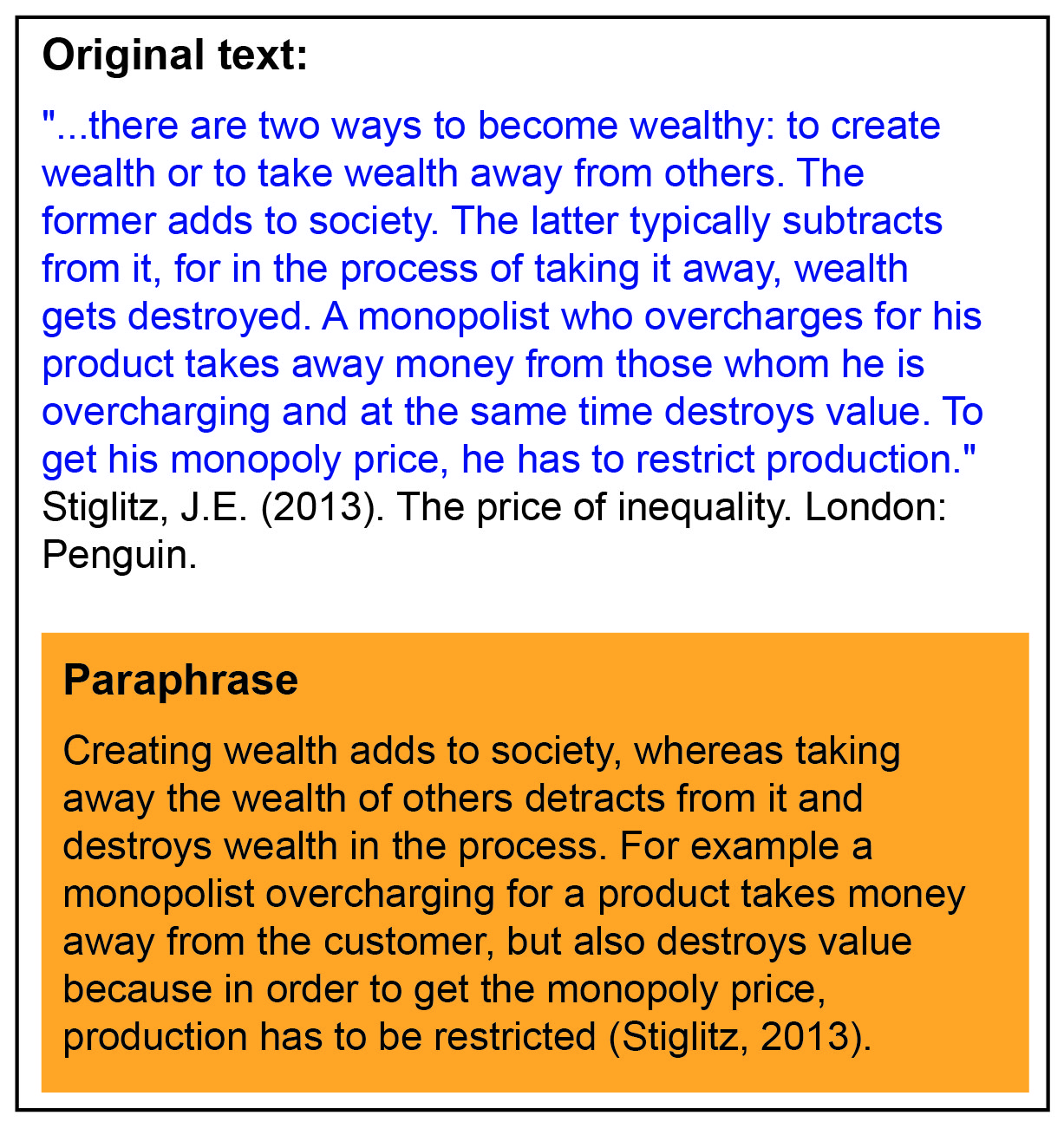

Paraphrasing involves putting a passage from source material into your own words. A paraphrase must also be attributed to the original source. Paraphrased material is usually shorter than the original passage, taking a somewhat broader segment of the source and condensing it slightly.

Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s). Once again, it is necessary to attribute summarized ideas to the original source. Summaries are significantly shorter than the original and take a broad overview of the source material.

Why use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries?

Quotations, paraphrases, and summaries serve many purposes. You might use them to:

- Provide support for claims or add credibility to your writing

- Refer to work that leads up to the work you are now doing

- Give examples of several points of view on a subject

- Call attention to a position that you wish to agree or disagree with

- Highlight a particularly striking phrase, sentence, or passage by quoting the original

- Distance yourself from the original by quoting it in order to cue readers that the words are not your own

- Expand the breadth or depth of your writing

Writers frequently intertwine summaries, paraphrases, and quotations. As part of a summary of an article, a chapter, or a book, a writer might include paraphrases of various key points blended with quotations of striking or suggestive phrases as in the following example:

In his famous and influential work The Interpretation of Dreams , Sigmund Freud argues that dreams are the "royal road to the unconscious" (page #), expressing in coded imagery the dreamer's unfulfilled wishes through a process known as the "dream-work" (page #). According to Freud, actual but unacceptable desires are censored internally and subjected to coding through layers of condensation and displacement before emerging in a kind of rebus puzzle in the dream itself (page #).

How to use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries

Practice summarizing the essay found here , using paraphrases and quotations as you go. It might be helpful to follow these steps:

- Read the entire text, noting the key points and main ideas.

- Summarize in your own words what the single main idea of the essay is.

- Paraphrase important supporting points that come up in the essay.

- Consider any words, phrases, or brief passages that you believe should be quoted directly.

There are several ways to integrate quotations into your text. Often, a short quotation works well when integrated into a sentence. Longer quotations can stand alone. Remember that quoting should be done only sparingly; be sure that you have a good reason to include a direct quotation when you decide to do so. You'll find guidelines for citing sources and punctuating citations at our documentation guide pages.

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Download this Handout PDF

College writing often involves integrating information from published sources into your own writing in order to add credibility and authority–this process is essential to research and the production of new knowledge.

However, when building on the work of others, you need to be careful not to plagiarize : “to steal and pass off (the ideas and words of another) as one’s own” or to “present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source.”1 The University of Wisconsin–Madison takes this act of “intellectual burglary” very seriously and considers it to be a breach of academic integrity . Penalties are severe.

These materials will help you avoid plagiarism by teaching you how to properly integrate information from published sources into your own writing.

1. Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed. (Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 1993), 888.

How to avoid plagiarism

When using sources in your papers, you can avoid plagiarism by knowing what must be documented.

Specific words and phrases

If you use an author’s specific word or words, you must place those words within quotation marks and you must credit the source.

Information and Ideas

Even if you use your own words, if you obtained the information or ideas you are presenting from a source, you must document the source.

Information : If a piece of information isn’t common knowledge (see below), you need to provide a source.

Ideas : An author’s ideas may include not only points made and conclusions drawn, but, for instance, a specific method or theory, the arrangement of material, or a list of steps in a process or characteristics of a medical condition. If a source provided any of these, you need to acknowledge the source.

Common Knowledge?

You do not need to cite a source for material considered common knowledge:

General common knowledge is factual information considered to be in the public domain, such as birth and death dates of well-known figures, and generally accepted dates of military, political, literary, and other historical events. In general, factual information contained in multiple standard reference works can usually be considered to be in the public domain.

Field-specific common knowledge is “common” only within a particular field or specialty. It may include facts, theories, or methods that are familiar to readers within that discipline. For instance, you may not need to cite a reference to Piaget’s developmental stages in a paper for an education class or give a source for your description of a commonly used method in a biology report—but you must be sure that this information is so widely known within that field that it will be shared by your readers.

If in doubt, be cautious and cite the source. And in the case of both general and field-specific common knowledge, if you use the exact words of the reference source, you must use quotation marks and credit the source.

Paraphrasing vs. Quoting — Explanation

Should i paraphrase or quote.

In general, use direct quotations only if you have a good reason. Most of your paper should be in your own words. Also, it’s often conventional to quote more extensively from sources when you’re writing a humanities paper, and to summarize from sources when you’re writing in the social or natural sciences–but there are always exceptions.

In a literary analysis paper , for example, you”ll want to quote from the literary text rather than summarize, because part of your task in this kind of paper is to analyze the specific words and phrases an author uses.

In research papers , you should quote from a source

- to show that an authority supports your point

- to present a position or argument to critique or comment on

- to include especially moving or historically significant language

- to present a particularly well-stated passage whose meaning would be lost or changed if paraphrased or summarized

You should summarize or paraphrase when

- what you want from the source is the idea expressed, and not the specific language used to express it

- you can express in fewer words what the key point of a source is

How to paraphrase a source

General advice.

- When reading a passage, try first to understand it as a whole, rather than pausing to write down specific ideas or phrases.

- Be selective. Unless your assignment is to do a formal or “literal” paraphrase, you usually don?t need to paraphrase an entire passage; instead, choose and summarize the material that helps you make a point in your paper.

- Think of what “your own words” would be if you were telling someone who’s unfamiliar with your subject (your mother, your brother, a friend) what the original source said.

- Remember that you can use direct quotations of phrases from the original within your paraphrase, and that you don’t need to change or put quotation marks around shared language.

Methods of Paraphrasing

- Look away from the source then write. Read the text you want to paraphrase several times until you feel that you understand it and can use your own words to restate it to someone else. Then, look away from the original and rewrite the text in your own words.

- Take notes. Take abbreviated notes; set the notes aside; then paraphrase from the notes a day or so later, or when you draft.

If you find that you can’t do A or B, this may mean that you don’t understand the passage completely or that you need to use a more structured process until you have more experience in paraphrasing.

The method below is not only a way to create a paraphrase but also a way to understand a difficult text.

Paraphrasing difficult texts

Consider the following passage from Love and Toil (a book on motherhood in London from 1870 to 1918), in which the author, Ellen Ross, puts forth one of her major arguments:

- Love and Toil maintains that family survival was the mother’s main charge among the large majority of London?s population who were poor or working class; the emotional and intellectual nurture of her child or children and even their actual comfort were forced into the background. To mother was to work for and organize household subsistence. (p. 9)

Children of the poor at the turn of the century received little if any emotional or intellectual nurturing from their mothers, whose main charge was family survival. Working for and organizing household subsistence were what defined mothering. Next to this, even the children’s basic comfort was forced into the background (Ross, 1995).

According to Ross (1993), poor children at the turn of the century received little mothering in our sense of the term. Mothering was defined by economic status, and among the poor, a mother’s foremost responsibility was not to stimulate her children’s minds or foster their emotional growth but to provide food and shelter to meet the basic requirements for physical survival. Given the magnitude of this task, children were deprived of even the “actual comfort” (p. 9) we expect mothers to provide today.

You may need to go through this process several times to create a satisfactory paraphrase.

Successful vs. unsuccessful paraphrases

Paraphrasing is often defined as putting a passage from an author into “your own words.” But what are your own words? How different must your paraphrase be from the original?

The paragraphs below provide an example by showing a passage as it appears in the source, two paraphrases that follow the source too closely, and a legitimate paraphrase.

The student’s intention was to incorporate the material in the original passage into a section of a paper on the concept of “experts” that compared the functions of experts and nonexperts in several professions.

The Passage as It Appears in the Source

Critical care nurses function in a hierarchy of roles. In this open heart surgery unit, the nurse manager hires and fires the nursing personnel. The nurse manager does not directly care for patients but follows the progress of unusual or long-term patients. On each shift a nurse assumes the role of resource nurse. This person oversees the hour-by-hour functioning of the unit as a whole, such as considering expected admissions and discharges of patients, ascertaining that beds are available for patients in the operating room, and covering sick calls. Resource nurses also take a patient assignment. They are the most experienced of all the staff nurses. The nurse clinician has a separate job description and provides for quality of care by orienting new staff, developing unit policies, and providing direct support where needed, such as assisting in emergency situations. The clinical nurse specialist in this unit is mostly involved with formal teaching in orienting new staff. The nurse manager, nurse clinician, and clinical nurse specialist are the designated experts. They do not take patient assignments. The resource nurse is seen as both a caregiver and a resource to other caregivers. . . . Staff nurses have a hierarchy of seniority. . . . Staff nurses are assigned to patients to provide all their nursing care. (Chase, 1995, p. 156)

Word-for-Word Plagiarism

Critical care nurses have a hierarchy of roles. The nurse manager hires and fires nurses. S/he does not directly care for patients but does follow unusual or long-term cases. On each shift a resource nurse attends to the functioning of the unit as a whole, such as making sure beds are available in the operating room , and also has a patient assignment . The nurse clinician orients new staff, develops policies, and provides support where needed . The clinical nurse specialist also orients new staff, mostly by formal teaching. The nurse manager, nurse clinician, and clinical nurse specialist , as the designated experts, do not take patient assignments . The resource nurse is not only a caregiver but a resource to the other caregivers . Within the staff nurses there is also a hierarchy of seniority . Their job is to give assigned patients all their nursing care .

Why this is plagiarism

Notice that the writer has not only “borrowed” Chase’s material (the results of her research) with no acknowledgment, but has also largely maintained the author’s method of expression and sentence structure. The phrases in red are directly copied from the source or changed only slightly in form.

Even if the student-writer had acknowledged Chase as the source of the content, the language of the passage would be considered plagiarized because no quotation marks indicate the phrases that come directly from Chase. And if quotation marks did appear around all these phrases, this paragraph would be so cluttered that it would be unreadable.

A Patchwork Paraphrase

Chase (1995) describes how nurses in a critical care unit function in a hierarchy that places designated experts at the top and the least senior staff nurses at the bottom. The experts — the nurse manager, nurse clinician, and clinical nurse specialist — are not involved directly in patient care. The staff nurses, in contrast, are assigned to patients and provide all their nursing care . Within the staff nurses is a hierarchy of seniority in which the most senior can become resource nurses: they are assigned a patient but also serve as a resource to other caregivers. The experts have administrative and teaching tasks such as selecting and orienting new staff, developing unit policies , and giving hands-on support where needed.

This paraphrase is a patchwork composed of pieces in the original author’s language (in red) and pieces in the student-writer’s words, all rearranged into a new pattern, but with none of the borrowed pieces in quotation marks. Thus, even though the writer acknowledges the source of the material, the underlined phrases are falsely presented as the student’s own.

A Legitimate Paraphrase

In her study of the roles of nurses in a critical care unit, Chase (1995) also found a hierarchy that distinguished the roles of experts and others. Just as the educational experts described above do not directly teach students, the experts in this unit do not directly attend to patients. That is the role of the staff nurses, who, like teachers, have their own “hierarchy of seniority” (p. 156). The roles of the experts include employing unit nurses and overseeing the care of special patients (nurse manager), teaching and otherwise integrating new personnel into the unit (clinical nurse specialist and nurse clinician), and policy-making (nurse clinician). In an intermediate position in the hierarchy is the resource nurse, a staff nurse with more experience than the others, who assumes direct care of patients as the other staff nurses do, but also takes on tasks to ensure the smooth operation of the entire facility.

Why this is a good paraphrase

The writer has documented Chase’s material and specific language (by direct reference to the author and by quotation marks around language taken directly from the source). Notice too that the writer has modified Chase’s language and structure and has added material to fit the new context and purpose — to present the distinctive functions of experts and nonexperts in several professions.

Shared Language

Perhaps you’ve noticed that a number of phrases from the original passage appear in the legitimate paraphrase: critical care, staff nurses, nurse manager, clinical nurse specialist, nurse clinician, resource nurse.

If all these phrases were in red, the paraphrase would look much like the “patchwork” example. The difference is that the phrases in the legitimate paraphrase are all precise, economical, and conventional designations that are part of the shared language within the nursing discipline (in the too-close paraphrases, they’re red only when used within a longer borrowed phrase).

In every discipline and in certain genres (such as the empirical research report), some phrases are so specialized or conventional that you can’t paraphrase them except by wordy and awkward circumlocutions that would be less familiar (and thus less readable) to the audience.

When you repeat such phrases, you’re not stealing the unique phrasing of an individual writer but using a common vocabulary shared by a community of scholars.

Some Examples of Shared Language You Don’t Need to Put in Quotation Marks

- Conventional designations: e.g., physician’s assistant, chronic low-back pain

- Preferred bias-free language: e.g., persons with disabilities

- Technical terms and phrases of a discipline or genre : e.g., reduplication, cognitive domain, material culture, sexual harassment

Chase, S. K. (1995). The social context of critical care clinical judgment. Heart and Lung, 24, 154-162.

How to Quote a Source

Introducing a quotation.

One of your jobs as a writer is to guide your reader through your text. Don’t simply drop quotations into your paper and leave it to the reader to make connections.

Integrating a quotation into your text usually involves two elements:

- A signal that a quotation is coming–generally the author’s name and/or a reference to the work

- An assertion that indicates the relationship of the quotation to your text

Often both the signal and the assertion appear in a single introductory statement, as in the example below. Notice how a transitional phrase also serves to connect the quotation smoothly to the introductory statement.

Ross (1993), in her study of poor and working-class mothers in London from 1870-1918 [signal], makes it clear that economic status to a large extent determined the meaning of motherhood [assertion]. Among this population [connection], “To mother was to work for and organize household subsistence” (p. 9).

The signal can also come after the assertion, again with a connecting word or phrase:

Illness was rarely a routine matter in the nineteenth century [assertion]. As [connection] Ross observes [signal], “Maternal thinking about children’s health revolved around the possibility of a child’s maiming or death” (p. 166).

Formatting Quotations

Short direct prose.

Incorporate short direct prose quotations into the text of your paper and enclose them in double quotation marks:

According to Jonathan Clarke, “Professional diplomats often say that trying to think diplomatically about foreign policy is a waste of time.”

Longer prose quotations

Begin longer quotations (for instance, in the APA system, 40 words or more) on a new line and indent the entire quotation (i.e., put in block form), with no quotation marks at beginning or end, as in the quoted passage from our Successful vs. Unsucessful Paraphrases page.

Rules about the minimum length of block quotations, how many spaces to indent, and whether to single- or double-space extended quotations vary with different documentation systems; check the guidelines for the system you’re using.

Quotation of Up to 3 Lines of Poetry

Quotations of up to 3 lines of poetry should be integrated into your sentence. For example:

In Julius Caesar, Antony begins his famous speech with “Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears; / I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him” (III.ii.75-76).

Notice that a slash (/) with a space on either side is used to separate lines.

Quotation of More than 3 Lines of Poetry

More than 3 lines of poetry should be indented. As with any extended (indented) quotation, do not use quotation marks unless you need to indicate a quotation within your quotation.

Punctuating with Quotation Marks

Parenthetical citations.

With short quotations, place citations outside of closing quotation marks, followed by sentence punctuation (period, question mark, comma, semi-colon, colon):

Menand (2002) characterizes language as “a social weapon” (p. 115).

With block quotations, check the guidelines for the documentation system you are using.

Commas and periods

Place inside closing quotation marks when no parenthetical citation follows:

Hertzberg (2002) notes that “treating the Constitution as imperfect is not new,” but because of Dahl’s credentials, his “apostasy merits attention” (p. 85).

Semicolons and colons

Place outside of closing quotation marks (or after a parenthetical citation).

Question marks and exclamation points

Place inside closing quotation marks if the quotation is a question/exclamation:

Menand (2001) acknowledges that H. W. Fowler’s Modern English Usage is “a classic of the language,” but he asks, “Is it a dead classic?” (p. 114).

[Note that a period still follows the closing parenthesis.]

Place outside of closing quotation marks if the entire sentence containing the quotation is a question or exclamation:

How many students actually read the guide to find out what is meant by “academic misconduct”?

Quotation within a quotation

Use single quotation marks for the embedded quotation:

According to Hertzberg (2002), Dahl gives the U. S. Constitution “bad marks in ‘democratic fairness’ and ‘encouraging consensus'” (p. 90).

[The phrases “democratic fairness” and “encouraging consensus” are already in quotation marks in Dahl’s sentence.]

Indicating Changes in Quotations

Quoting only a portion of the whole.

Use ellipsis points (. . .) to indicate an omission within a quotation–but not at the beginning or end unless it’s not obvious that you’re quoting only a portion of the whole.

Adding Clarification, Comment, or Correction

Within quotations, use square brackets [ ] (not parentheses) to add your own clarification, comment, or correction.

Use [sic] (meaning “so” or “thus”) to indicate that a mistake is in the source you’re quoting and is not your own.

Additional information

Information on summarizing and paraphrasing sources.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). (2000). Retrieved January 7, 2002, from http://www.bartleby.com/61/ Bazerman, C. (1995). The informed writer: Using sources in the disciplines (5th ed). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Leki, I. (1995). Academic writing: Exploring processes and strategies (2nd ed.) New York: St. Martin?s Press, pp. 185-211.

Leki describes the basic method presented in C, pp. 4-5.

Spatt, B. (1999). Writing from sources (5th ed.) New York: St. Martin?s Press, pp. 98-119; 364-371.

Information about specific documentation systems

The Writing Center has handouts explaining how to use many of the standard documentation systems. You may look at our general Web page on Documentation Systems, or you may check out any of the following specific Web pages.

If you’re not sure which documentation system to use, ask the course instructor who assigned your paper.

- American Psychological Assoicaion (APA)

- Modern Language Association (MLA)

- Chicago/Turabian (A Footnote or Endnote System)

- American Political Science Association (APSA)

- Council of Science Editors (CBE)

- Numbered References

You may also consult the following guides:

- American Medical Association, Manual for Authors and Editors

- Council of Science Editors, CBE style Manual

- The Chicago Manual of Style

- MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

APA Citation Guide (7th edition): Quotes vs Paraphrases

- Book Examples

- Article Examples

- Media Examples

- Internet Resources Examples

- Other Examples

- Quotes vs Paraphrases

- Reference Entry Components

- Paper Formatting

What's the Difference?

Quoting vs paraphrasing: what's the difference.

There are two ways to integrate sources into your assignment: quoting directly or paraphrasing.

Quoting is copying a selection from someone else's work, phrasing it exactly as it was originally written. When quoting place quotation marks (" ") around the selected passage to show where the quote begins and where it ends. Make sure to include an in-text citation.

Paraphrasing is used to show that you understand what the author wrote. You must reword the passage, expressing the ideas in your own words, and not just change a few words here and there. Make sure to also include an in-text citation.

Quoting Example

There are two basic formats that can be used:

Parenthetical Style:

Narrative Style:

Quoting Tips

- Long Quotes

- Changing Quotes

What Is a Long Quotation?

A quotation of more than 40 words.

Rules for Long Quotations

There are 4 rules that apply to long quotations that are different from regular quotations:

- The line before your long quotation, when you're introducing the quote, usually ends with a colon.

- The long quotation is indented half an inch from the rest of the text, so it looks like a block of text.

- There are no quotation marks around the quotation.

- The period at the end of the quotation comes before your in-text citation as opposed to after, as it does with regular quotations.

Example of a Long Quotation

At the end of Lord of the Flies the boys are struck with the realization of their behaviour:

The tears began to flow and sobs shook him. He gave himself up to them now for the first time on the island; great, shuddering spasms of grief that seemed to wrench his whole body. His voice rose under the black smoke before the burning wreckage of the island; and infected by that emotion, the other little boys began to shake and sob too. (Golding, 1960, p.186)

Changing Quotations

Sometimes you may want to make some modifications to the quote to fit your writing. Here are some APA rules when changing quotes:

Incorrect spelling, grammar, and punctuation

Add the word [sic] after the error in the quotation to let your reader know the error was in the original source and is not your error.

Omitting parts of a quotation

If you would like to exclude some words from a quotation, replace the words you are not including with an ellipsis - ...

Adding words to a quote

If you are adding words that are not part of the original quote, enclose the additional words in square brackets - [XYZ]

Secondary Source Quotes

What is a secondary source.

In scholarly work, a primary source reports original content; a secondary source refers to content first reported in another source.

- Cite secondary sources sparingly—for instance, when the original work is out of print, unavailable, or available only in a language that you do not understand.

- If possible, as a matter of good scholarly practice, find the primary source, read it, and cite it directly rather than citing a secondary source.

Rules for Secondary Source Citations

- In the reference list, provide an entry only for the secondary source that you used.

- In the text, identify the primary source and write “as cited in” the secondary source that you used.

- If the year of publication of the primary source is known, also include it in the in-text citation.

Example of a Secondary Source Use

Quote & In-Text Citation

Reference List Entry

Paraphrases

Paraphrasing example.

When you write information from a source in your own words, cite the source by adding an in-text citation at the end of the paraphrased portion as follows:

If you refer to the author's name in a sentence you do not have to include the name again as part of your in-text citation, instead include the year of publication following his/her name:

NOTE : Although not required, APA encourages including the page number when paraphrasing if it will help the reader locate the information in a long text and distinguish between the information that is coming from you and the source.

Paraphrasing Tips

- Long Paraphrases

Original Source

Homeless individuals commonly come from families who are riddled with problems and marital disharmony, and are alienated from their parents. They have often been physically and even sexually abused, have relocated frequently, and many of them may be asked to leave home or are actually thrown out, or alternatively are placed in group homes or in foster care. They often have no one to care for them and no one knows them intimately.

Source from:

Rokach, A. (2005). The causes of loneliness in homeless youth. The Journal of Psychology, 139, 469-480.

Example: Incorrect Paraphrasing

Example: correct paraphrasing.

If your paraphrase is longer than one sentence, provide an in-text citation for the source at the beginning of the paraphrase. As long as it's clear that the paraphrase continues to the following sentences, you don't have to include in-text citations for the following sentences.

If your paraphrase continues to another paragraph and/or you include paraphrases from other sources within the paragraph, repeat the in-text citations for each.

Additional Resource

- Paraphrasing (The Learning Portal)

Tip sheet on paraphrasing information

- << Previous: In-Text Citations

- Next: Reference Entry Components >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 4:00 PM

- URL: https://simmons.libguides.com/apa

- Utility Menu

fa3d988da6f218669ec27d6b6019a0cd

A publication of the harvard college writing program.

Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- The Honor Code

Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting

Depending on the conventions of your discipline, you may have to decide whether to summarize a source, paraphrase a source, or quote from a source.

Scholars in the humanities tend to summarize, paraphrase, and quote texts; social scientists and natural scientists rely primarily on summary and paraphrase.

When and how to summarize

When you summarize, you provide your readers with a condensed version of an author's key points. A summary can be as short as a few sentences or much longer, depending on the complexity of the text and the level of detail you wish to provide to your readers. You will need to summarize a source in your paper when you are going to refer to that source and you want your readers to understand the source's argument, main ideas, or plot (if the source is a novel, film, or play) before you lay out your own argument about it, analysis of it, or response to it.

Before you summarize a source in your paper, you should decide what your reader needs to know about that source in order to understand your argument. For example, if you are making an argument about a novel, you should avoid filling pages of your paper with details from the book that will distract or confuse your reader. Instead, you should add details sparingly, going only into the depth that is necessary for your reader to understand and appreciate your argument. Similarly, if you are writing a paper about a journal article, you will need to highlight the most relevant parts of the argument for your reader, but you should not include all of the background information and examples. When you have to decide how much summary to put in a paper, it's a good idea to consult your instructor about whether you are supposed to assume your reader's knowledge of the sources.

Guidelines for summarizing a source in your paper

- Identify the author and the source.

- Represent the original source accurately.

- Present the source’s central claim clearly.

- Don’t summarize each point in the same order as the original source; focus on giving your reader the most important parts of the source

- Use your own words. Don’t provide a long quotation in the summary unless the actual language from the source is going to be important for your reader to see.

Stanley Milgram (1974) reports that ordinarily compassionate people will be cruel to each other if they are commanded to be by an authority figure. In his experiment, a group of participants were asked to administer electric shocks to people who made errors on a simple test. In spite of signs that those receiving shock were experiencing great physical pain, 25 of 40 subjects continued to administer electric shocks. These results held up for each group of people tested, no matter the demographic. The transcripts of conversations from the experiment reveal that although many of the participants felt increasingly uncomfortable, they continued to obey the experimenter, often showing great deference for the experimenter. Milgram suggests that when people feel responsible for carrying out the wishes of an authority figure, they do not feel responsible for the actual actions they are performing. He concludes that the increasing division of labor in society encourages people to focus on a small task and eschew responsibility for anything they do not directly control.

This summary of Stanley Milgram's 1974 essay, "The Perils of Obedience," provides a brief overview of Milgram's 12-page essay, along with an APA style parenthetical citation. You would write this type of summary if you were discussing Milgram's experiment in a paper in which you were not supposed to assume your reader's knowledge of the sources. Depending on your assignment, your summary might be even shorter.

When you include a summary of a paper in your essay, you must cite the source. If you were using APA style in your paper, you would include a parenthetical citation in the summary, and you would also include a full citation in your reference list at the end of your paper. For the essay by Stanley Milgram, your citation in your references list would include the following information:

Milgram, S. (1974). The perils of obedience. In L.G. Kirszner & S.R. Mandell (Eds.), The Blair reader (pp.725-737).

When and how to paraphrase

When you paraphrase from a source, you restate the source's ideas in your own words. Whereas a summary provides your readers with a condensed overview of a source (or part of a source), a paraphrase of a source offers your readers the same level of detail provided in the original source. Therefore, while a summary will be shorter than the original source material, a paraphrase will generally be about the same length as the original source material.

When you use any part of a source in your paper—as background information, as evidence, as a counterargument to which you plan to respond, or in any other form—you will always need to decide whether to quote directly from the source or to paraphrase it. Unless you have a good reason to quote directly from the source , you should paraphrase the source. Any time you paraphrase an author's words and ideas in your paper, you should make it clear to your reader why you are presenting this particular material from a source at this point in your paper. You should also make sure you have represented the author accurately, that you have used your own words consistently, and that you have cited the source.

This paraphrase below restates one of Milgram's points in the author's own words. When you paraphrase, you should always cite the source. This paraphrase uses the APA in-text citation style. Every source you paraphrase should also be included in your list of references at the end of your paper. For citation format information go to the Citing Sources section of this guide.

Source material

The problem of obedience is not wholly psychological. The form and shape of society and the way it is developing have much to do with it. There was a time, perhaps, when people were able to give a fully human response to any situation because they were fully absorbed in it as human beings. But as soon as there was a division of labor things changed.

--Stanley Milgram, "The Perils of Obedience," p.737.

Milgram, S. (1974). The perils of obedience. In L.G. Kirszner & S.R. Mandell (Eds.), The Blair reader (pp.725-737). Prentice Hall.

Milgram (1974) claims that people's willingness to obey authority figures cannot be explained by psychological factors alone. In an earlier era, people may have had the ability to invest in social situations to a greater extent. However, as society has become increasingly structured by a division of labor, people have become more alienated from situations over which they do not have control (p.737).

When and how much to quote

The basic rule in all disciplines is that you should only quote directly from a text when it's important for your reader to see the actual language used by the author of the source. While paraphrase and summary are effective ways to introduce your reader to someone's ideas, quoting directly from a text allows you to introduce your reader to the way those ideas are expressed by showing such details as language, syntax, and cadence.

So, for example, it may be important for a reader to see a passage of text quoted directly from Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried if you plan to analyze the language of that passage in order to support your thesis about the book. On the other hand, if you're writing a paper in which you're making a claim about the reading habits of American elementary school students or reviewing the current research on Wilson's disease, the information you’re providing from sources will often be more important than the exact words. In those cases, you should paraphrase rather than quoting directly. Whether you quote from your source or paraphrase it, be sure to provide a citation for your source, using the correct format. (see Citing Sources section)

You should use quotations in the following situations:

- When you plan to discuss the actual language of a text.

- When you are discussing an author's position or theory, and you plan to discuss the wording of a core assertion or kernel of the argument in your paper.

- When you risk losing the essence of the author's ideas in the translation from their words to your own.

- When you want to appeal to the authority of the author and using their words will emphasize that authority.

Once you have decided to quote part of a text, you'll need to decide whether you are going to quote a long passage (a block quotation) or a short passage (a sentence or two within the text of your essay). Unless you are planning to do something substantive with a long quotation—to analyze the language in detail or otherwise break it down—you should not use block quotations in your essay. While long quotations will stretch your page limit, they don't add anything to your argument unless you also spend time discussing them in a way that illuminates a point you're making. Unless you are giving your readers something they need to appreciate your argument, you should use quotations sparingly.

When you quote from a source, you should make sure to cite the source either with an in-text citation or a note, depending on which citation style you are using. The passage below, drawn from O’Brien’s The Things They Carried , uses an MLA-style citation.

On the morning after Ted Lavender died, First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross crouched at the bottom of his foxhole and burned Martha's letters. Then he burned the two photographs. There was a steady rain falling, which made it difficult, but he used heat tabs and Sterno to build a small fire, screening it with his body holding the photographs over the tight blue flame with the tip of his fingers.

He realized it was only a gesture. Stupid, he thought. Sentimental, too, but mostly just stupid. (23)

O'Brien, Tim. The Things They Carried . New York: Broadway Books, 1990.

Even as Jimmy Cross burns Martha's letters, he realizes that "it was only a gesture. Stupid, he thought. Sentimental too, but mostly just stupid" (23).

If you were writing a paper about O'Brien's The Things They Carried in which you analyzed Cross's decision to burn Martha's letters and stop thinking about her, you might want your reader to see the language O'Brien uses to illustrate Cross's inner conflict. If you were planning to analyze the passage in which O'Brien calls Cross's realization stupid, sentimental, and then stupid again, you would want your reader to see the original language.

Using and Incorporating Sources

Examples of quotations and paraphrases.

Here are a couple examples of what we mean about properly quoting and paraphrasing evidence in your research essays. In each case, we begin with a BAD example, or the way NOT to quote or paraphrase.

Quoting in APA Style

Consider this BAD example in APA style, of what NOT to do when quoting evidence:

“If the U.S. scallop fishery were a business, its management would surely be fired, because its revenues could readily be increased by at least 50 percent while its costs were being reduced by an equal percentage.” (Repetto, 2001, p. 84).

Again, this is a potentially valuable piece of evidence, but it simply isn’t clear what point the research writer is trying to make with it. Further, it doesn’t follow the preferred method of citation with APA style.

Here is a revision that is a GOOD (or at least BETTER ) example:

Repetto (2001) concludes that, in the case of the scallop industry, those running the industry should be held responsible for not considering methods that would curtail the problems of over-fishing. If the U.S. scallop fishery were a business, its management would surely be fired, because its revenues could readily be increased by at least 50 percent while its costs were being reduced by an equal percentage (p. 84).

This revision is improved because the research writer has introduced and explained the point of the evidence with the addition of a clarifying sentence. It also follows the rules of APA style. Generally, APA style prefers that the research writer refer to the author only by last name followed immediately by the year of publication. Whenever possible, you should begin your citation with the author’s last name and the year of publication, and, in the case of a direct quote like this passage, the page number (including the “p.”) in parentheses at the end.

Paraphrasing in APA Style

Paraphrasing in APA style is slightly different from MLA style as well. Consider first this BAD example of what NOT to do in paraphrasing from a source in APA style:

Computer criminals have lots of ways to get away with credit card fraud (Cameron, 2002).

The main problem with this paraphrase is there isn’t enough here to adequately explain to the reader what the point of the evidence really is. Remember: your readers have no way of automatically knowing why you as a research writer think that a particular piece of evidence is useful in supporting your point. This is why it is key that you introduce and explain your evidence.

Here is a revision that is GOOD (or at least BETTER ):

Cameron (2002) points out that computer criminals intent on committing credit card fraud are able to take advantage of the fact that there aren’t enough officials working to enforce computer crimes. Criminals are also able to use the technology to their advantage by communicating via email and chat rooms with other criminals.

Again, this revision is better because the additional information introduces and explains the point of the evidence. In this particular example, the author’s name is also incorporated into the explanation of the evidence as well. In APA, it is preferable to weave in the authors’ names into your essay, usually at the beginning of a sentence. However, it would also have been acceptable to end an improved paraphrase with just the author’s last name and the date of publication in parentheses.

- Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Avoiding Plagiarism. Authored by : Steven D. Krause . Located at : http://www.stevendkrause.com/tprw/chapter3.html . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Privacy Policy

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Mentor Texts

Quoting and Paraphrasing Experts and Research: The Times Tip Column

This short, engaging column can teach you a few moves for incorporating information from sources into an essay.

By Katherine Schulten

Our new Mentor Text series spotlights writing from The Times that students can learn from and emulate.

This entry aims to help support those participating in our STEM-writing contest , in which students are invited to choose an issue or question in science, technology, engineering, math or health that interests them, then write a 500-word explanation that will engage and enlighten readers.

For even more on how to help your students write interesting, clear and meaningful informational pieces, please see our related writing unit .

All informational journalism quotes experts and stakeholders. That’s the journalist’s job — to gather information from a range of sources so that the resulting article is authoritative and balanced.

Page or click through The Times or any other news source and you’ll see. You would of course expect front-page articles about serious issues to reference multiple perspectives the way this one on the coronavirus does, quoting patients, Chinese officials, public health experts and scientists who study virology. But if you check out pieces from sections like Style and Sports, you’ll notice the same. Whether you’re reading a piece on social-media influencers or skateboarding , you’ll see that the writer has included a range of points of view.

If you’re writing your own piece, perhaps for our contest , you might be wondering, how do you choose the right people to quote? How do you use the information they give you? Even if you’re not conducting live interviews the way journalists do, any research-based writing task requires you to learn how to weave in the information you find in books or other sources. So when do you quote and when do you paraphrase? How do you do both of those things seamlessly?

For this edition of Mentor Texts, we’ve chosen to spotlight the short, engaging Tip column that appears weekly in the Magazine. Here’s why it’s so useful:

It is written to a practical and engaging formula, one you are welcome to follow if you are participating in our STEM-writing contest .

The column is usually no more than 400 words long. Since our contest gives you only 500 words to work with, Tip can show you how to impart a wealth of interesting information in just a few paragraphs.

Because it is so short, each edition is built around an interview with a single expert. Noting what expert the author, Malia Wollan, chooses and how she uses the resulting information can help you see when to quote and when to paraphrase, and teach you how to do both gracefully.

Here are some ways to do that.

First: Spot the Pattern

Choose three articles from the Tip column , whichever you think will interest you most.

For instance, you might choose …

How to survive a shark attack , rip current , flu pandemic or bear encounter .

How to build a sand castle , moat , bat box or latrine .

Or, how to thwart facial recognition , prepare yourself for space , attract butterflies , talk to dogs , or find a four-leaf clover .

After you’ve read three, answer these questions: What do you notice about the structure of a Tip column? That is, what predictable elements can readers expect to find in every edition?

Next: Examine Three Short Mentor Texts

If you went through the exercise above, you no doubt noticed this pattern:

The first line of all Tip articles is a quote from an expert. ( For example , “Hit the shark in the eyes and gills,” says Sarah Waries, the chief executive of Shark Spotters, an organization in Cape Town that employs 30 specialists to scan the city’s beaches with binoculars from the cliffs and sound the alarm when they see one in the water.” )

That same expert gives background and advice throughout the piece. ( “It’s critical to stop the bleeding,” Waries says. )

The expert also usually gets the last word in the form of a final, fitting quote. ( “Sharks are everywhere,” Waries says. “They’re in all the oceans.” )

Below are three STEM-focused articles from this column that we have chosen as mentors. We’ve excerpted the first paragraph of each, but please read them all in full.

“ How to Enjoy Snowflakes ”:

“It’s easier to appreciate snowflakes when you don’t have a shovel in your hand,” says Kenneth G. Libbrecht, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif., who studies snowflake morphology by growing ice crystals in his laboratory. Go out in the snow with dark clothing on and let a few flakes fall on your coat. Peer at them through a magnifying glass. Don’t assume you’ll see the archetypal, branching-star type called stellar dendrites, which require temperatures around minus 15 degrees Celsius. To see those in the wild, Libbrecht travels to a small town in northeastern Ontario. “The people there think I’m crazy,” he says.

“ How to Hold a Venomous Snake ”:

‘‘The snake will defecate on you,’’ says Jim Harrison, who extracts venom from approximately 1,000 snakes every week for use in drug research and development. Learn to ignore the stink. Collecting venom requires pinching a snake firmly behind its skull until it clamps its fangs over a sterile collection vial; snakes will squirt excreta in an effort to escape. ‘‘When I’m done extracting the cobras, I’m covered in feces and my wife won’t come close to me,’’ Harrison says.

“ How to Fast ”:

“Fasting is mental over physical, just like basketball and most other stuff in life,” says Enes Kanter, the 6-foot-11 center for the Portland Trail Blazers. Raised in Turkey, Kanter, 27, is a Muslim who has fasted from sunrise to sunset during the month of Ramadan since he was 8. This season, Ramadan aligned with the N.B.A. playoffs, so Kanter fasted through seven playoff games . During the year he forgoes food and water a day or two a week. “Don’t be scared to try it,” he says.

Now, answer these questions:

Whom does the writer quote in each of these columns? Why do you think the author chose them? Do you think they were good sources of information?

Look closely at when the author chooses to quote the experts and when she paraphrases the information they gave her. What is the difference? Why do you think she chose to quote the lines she did? Give some examples from the pieces to explain your reasoning.

What do you notice about how she works in quotations? How does she introduce them so they make sense and add a little color? For instance, the second paragraph of “How to Hold a Venomous Snake” begins this way: “Unless you’re a trained venom extractor, don’t pick up a snake with your hands. Even zookeepers and herpetologists keep out of striking distance by scooping specimens up with a pole called a snake hook. ‘Everybody thinks they know what they’re doing because they saw it on YouTube,’ Harrison says.” How do the first two sentences give practical information that leads us into the YouTube quote? How does that quote add a bit of humor to the piece?

Finally, look closely at the quotes that begin and end each piece. How would you describe the differences? Would the quotes work if they were flipped? What about any quotes you find in the middle paragraphs of these pieces? What observations can you make in general about the structure of a Tip column and how quotations work to build that structure?

Before you go, one last thing to notice. You may have been taught in school to cite your sources by using footnotes, or by putting them in parentheses after you’ve referenced the information. That’s not how journalists do it, yet they still make their sources clear.

If the article is online-only, sources are sometimes linked. For pieces like Tip, which appear both online and in print, sources are referenced in the reporting. For example, direct quotes, like “It’s critical to stop the bleeding,” from the shark piece, above, will have a “[name of person] says” somewhere in the sentence (“Waries says”). Paraphrases often start with a lead-in like, “According to …” or “Studies have found …” The Tip column quotes only one expert each week, so there is no need to keep adding “According to,” but, to continue our shark theme, notice the ways this paragraph from an Aug. 2019 article, “ How Sharks Glow to Each Other Deep in the Ocean ,” acknowledges its source:

In a study published Thursday in iScience , researchers reveal the secret behind this magical transformation: Molecules inside their scales transform how shark skin interacts with light, bringing in blue photons, and sending out green. This improved understanding of these sharks’ luminous illusions may lead to improvements in scientific imaging, as the study of biofluorescence in other marine life already has.

How does the first sentence make clear that the information comes from a particular study? How does the use of a colon help?

Now Try This: Make a List of Reliable Sources

Massive shark spotted in cape cod, great white sharks have become increasingly prevalent along the beaches in cape cod in massachusetts. last year was the state’s first fatal shark attack since 1936..

“Whoa. No way. Oh my God.” “Hold on, you guys. Hold on.” “Holy [expletive].” “It just hit the boat.” “Oh my God.” “Oh my God.” “Wow.” “Left, left.” “Dad, come look at it. Dad, come, come over here. Dad.”

We started with sharks, and we’re ending with sharks.

Let’s pretend that you’re a journalist, it’s summer, and there have been a rash of shark attacks in the United States and around the world. Your editor gives you not just the 400 words Malia Wollan got to write about how to survive a shark attack, but, instead, 1,200, three times that number. She assigns you to investigate the question: Should swimmers worry about sharks?

How will you find out? Whom will you interview? What information will you be looking for? What individuals, institutions and organizations might be reliable experts or stakeholders on this question? How will you know they’re reliable? What kinds of studies and statistics might you need, and how will you know those are reliable?

Make as long of a list as you can of all the people and places you might consult to get a full answer to that question, then share your list with others.

Then take a look at a 2015 Times piece in which the reporter Christine Hauser answers the very question we posed above : Should swimmers worry about sharks? What experts and organizations does she seem to have consulted? How many of them are similar to what you put on your list? Are there any she’s missing that she might have included if she had another 1,000 words to work with? How did she work the information in, both via direct quotes and paraphrases?

Finally, now that you’ve gone through all the exercises in this lesson, your next assignment is, of course, to figure out who and what expert sources to consult to find a range of information about whatever you’re writing about — then borrow some of the “writer’s moves” above to weave that information into your essay as seamlessly as you can. Good luck!

Related Questions for Any Informational Piece That Quotes Experts

Look through the piece. How many sources, whether they’re people or institutions, are named? How many are quoted, and how many are cited as the source of paraphrased information? How are they cited? What do those sources add to the piece?

Why do you think the author chose these sources? How reliable do they seem? How do you know?

How is the information from experts woven into the piece? How are quotes introduced? How do paraphrases make the source of the information clear?

What points of view, if any, are missing? What experts or stakeholders could this person have interviewed to get those points of view? Why?

What else do you notice or admire about this piece? What lessons might it have for your writing?

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / Citation Basics / Quoting vs. Paraphrasing vs. Summarizing

Quoting vs. Paraphrasing vs. Summarizing

If you’ve ever written a research essay, you know the struggle is real. Should you use a direct quote? Should you put it in your own words? And how is summarizing different from paraphrasing—aren’t they kind of the same thing?

Knowing how you should include your source takes some finesse, and knowing when to quote directly, paraphrase, or summarize can make or break your argument. Let’s take a look at the nuances among these three ways of using an outside source in an essay.

What is quoting?

The concept of quoting is pretty straightforward. If you use quotation marks, you must use precisely the same words as the original , even if the language is vulgar or the grammar is incorrect. In fact, when scholars quote writers with bad grammar, they may correct it by using typographical notes [like this] to show readers they have made a change.

“I never like[d] peas as a child.”

Conversely, if a passage with odd or incorrect language is quoted as is, the note [sic] may be used to show that no changes were made to the original language despite any errors.

“I never like [sic] peas as a child.”

The professional world looks very seriously on quotations. You cannot change a single comma or letter without documentation when you quote a source. Not only that, but the quote must be accompanied by an attribution, commonly called a citation. A misquote or failure to cite can be considered plagiarism.

When writing an academic paper, scholars must use in-text citations in parentheses followed by a complete entry on a references page. When you quote someone using MLA format , for example, it might look like this:

“The orphan is above all a character out of place, forced to make his or her own home in the world. The novel itself grew up as a genre representing the efforts of an ordinary individual to navigate his or her way through the trials of life. The orphan is therefore an essentially novelistic character, set loose from established conventions to face a world of endless possibilities (and dangers)” (Mullan).

This quote is from www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/orphans-in-fiction , which discusses the portrayal of orphans in Victorian English literature. The citation as it would look on the references page (called Works Cited in MLA) is available at the end of this guide.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing means taking a quote and putting it in your own words.

You translate what another writer has said into terms both you and your reader can more easily understand. Unlike summarizing, which focuses on the big picture, paraphrasing is involved with single lines or passages. Paraphrasing means you should focus only on segments of a text.

Paraphrasing is a way for you to start processing the information from your source . When you take a quote and put it into your own words, you are already working to better understand, and better explain, the information.

The more you can change the quote without changing the original meaning , the better. How can you make significant changes to a text without changing the meaning?

Here are a few paraphrasing techniques:

- Use synonyms of words

- Change the order of words

- Change the order of clauses in the sentences

- Move sentences around in a section

- Active – passive

- Positive – negative

- Statement-question

Let’s look at an example. Here is a direct quote from the article on orphans in Victorian literature:

“It is no accident that the most famous character in recent fiction – Harry Potter – is an orphan. The child wizard’s adventures are premised on the death of his parents and the responsibilities that he must therefore assume. If we look to classic children’s fiction we find a host of orphans” (Mullan).

Here is a possible paraphrase:

It’s not a mistake that a well-known protagonist in current fiction is an orphan: Harry Potter. His quests are due to his parents dying and tasks that he is now obligated to complete. You will see that orphans are common protagonists if you look at other classic fiction (Mullan).

What differences do you spot? There are synonyms. A few words were moved around. A few clauses were moved around. But do you see that the basic structure is very similar?

This kind of paraphrase might be flagged by a plagiarism checker. Don’t paraphrase like that.

Here is a better example:

What is the most well-known fact about beloved character, Harry Potter? That he’s an orphan – “the boy who lived”. In fact, it is only because his parents died that he was thrust into his hero’s journey. Throughout classic children’s literature, you’ll find many orphans as protagonists (Mullan).

Do you see that this paraphrase has more differences? The basic information is there, but the structure is quite different.

When you paraphrase, you are making choices: of how to restructure information, of how to organize and prioritize it. These choices reflect your voice in a way a direct quote cannot, since a direct quote is, by definition, someone else’s voice.

Which is better: Quoting or paraphrasing?

Although the purpose of both quoting and paraphrasing is to introduce the ideas of an external source, they are used for different reasons. It’s not that one is better than the other, but rather that quoting suits some purposes better, while paraphrasing is more suitable for others.

A direct quote is better when you feel the writer made the point perfectly and there is no reason to change a thing. If the writer has a strong voice and you want to preserve that, use a direct quote.

For example, no one should ever try to paraphrase John. F. Kenney’s famous line: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

However, think of direct quotes like a hot pepper: go ahead and sprinkle them around to add some spice to your paper, but… you might not want to overdo it.

Conversely, paraphrasing is useful when you want to bring in a longer section of a source into your piece, but you don’t have room for the full passage . A paraphrase doesn’t simplify the passage to an extreme level, like a summary would. Rather, it condenses the section of text into something more useful for your essay. It’s also appropriate to paraphrase when there are sentences within a passage that you want to leave out.

If you were to paraphrase the section of the article about Victorian orphans mentioned earlier, you might write something like this:

Considering the development of the novel, which portrayed everyday people making their way through life, using an orphan as a protagonist was effective. Orphans are characters that, by definition, need to find their way alone. The author can let the protagonist venture out into the world where the anything, good or bad, might happen (Mullan).

You’ll notice a couple of things here. One, there are no quotation marks, but there is still an in-text citation (the name in parentheses). A paraphrase lacks quotation marks because you aren’t directly quoting, but it still needs a citation because you are using a specific segment of the text. It is still someone else’s original idea and must be cited.

Secondly, if you look at the original quote, you’ll see that five lines of text are condensed into four and a half lines. Everything the author used has been changed.

A single paragraph of text has been explained in different words—which is the heart of paraphrasing.

What is summarizing?

Next, we come to summarizing. Summarizing is on a much larger scale than quoting or paraphrasing. While similar to paraphrasing in that you use your own words, a summary’s primary focus is on translating the main idea of an entire document or long section.

Summaries are useful because they allow you to mention entire chapters or articles—or longer works—in only a few sentences. However, summaries can be longer and more in-depth. They can actually include quotes and paraphrases. Keep in mind, though, that since a summary condenses information, look for the main points. Don’t include a lot of details in a summary.

In literary analysis essays, it is useful to include one body paragraph that summarizes the work you’re writing about. It might be helpful to quote or paraphrase specific lines that contribute to the main themes of such a work. Here is an example summarizing the article on orphans in Victorian literature:

In John Mullan’s article “Orphans in Fiction” on bl.uk.com, he reviews the use of orphans as protagonists in 19 th century Victorian literature. Mullan argues that orphans, without family attachments, are effective characters that can be “unleashed to discover the world.” This discovery process often leads orphans to expose dangerous aspects of society, while maintaining their innocence. As an example, Mullan examines how many female orphans wind up as governesses, demonstrating the usefulness of a main character that is obligated to find their own way.

This summary includes the main ideas of the article, one paraphrase, and one direct quote. A ten-paragraph article is summarized into one single paragraph.

As for giving source credit, since the author’s name and title of the source are stated at the beginning of the summary paragraph, you don’t need an in-text citation.

How do I know which one to use?

The fact is that writers use these three reference types (quoting, paraphrasing, summarizing) interchangeably. The key is to pay attention to your argument development. At some points, you will want concrete, firm evidence. Quotes are perfect for this.

At other times, you will want general support for an argument, but the text that includes such support is long-winded. A paraphrase is appropriate in this case.

Finally, sometimes you may need to mention an entire book or article because it is so full of evidence to support your points. In these cases, it is wise to take a few sentences or even a full paragraph to summarize the source.

No matter which type you use, you always need to cite your source on a References or Works Cited page at the end of the document. The MLA works cited entry for the text we’ve been using today looks like this:

Mullan, John. Orphans in Fiction” www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/orphans-in-fiction. Accessed 20. Oct. 2020

————–

See our related lesson with video: How to Quote and Paraphrase Evidence

Citation Guides

- Annotated Bibliography

- Block Quotes

- Citation Examples

- et al Usage

- In-text Citations

- Page Numbers

- Reference Page

- Sample Paper

- APA 7 Updates

- View APA Guide

- Bibliography

- Works Cited

- MLA 8 Updates

- View MLA Guide

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

Citations & References (New): Quoting, Paraphrasing and Summarizing

- Quoting, Paraphrasing and Summarizing

- In-Text Citations (MLA9 & APA7)

- From the IB

Quoting, paraphrasing and summarizing are three main ways to fairly and honestly include, integrate and refer to others’ work within your own. In other words – great ways to avoid plagiarism!

Quoting is reproducing an author’s words from a source, using the exact wording, spelling and punctuation. This adds emphasis and weight to an argument.

To correctly integrate a quote you should:

- According to Jones…

- Include quotation marks at the beginning and end of the quote.

- Cite and reference it in the appropriate style.

Summarizing

Summarizing is expressing the main ideas and concepts from another source, without including details. Summaries are short and concise.

To correctly summarize you should:

- Jones states… Jones further indicates…

- Cite and reference in the appropriate style

Signal Phrase

A Signal Phrase is when you name the author or resource as part of your sentence.

- According to Jones...

- Jones states that...

- As indicated by Jones...

- As seen on A brief history of books...

- As stated in Shakespeare : the illustrated edition ...

Using a Signal Phrase is a very important part of in-text citations.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is incorporating ideas from another source using your own words. This enables you to demonstrate your understanding and interpretation of the original idea in relation to your topic.

To correctly paraphrase you should:

- Rewrite, reorder, and rephrase key points from the original source

- Jones states … As indicated by Jones…

- Cite and Reference in the appropriate style.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: In-Text Citations (MLA9 & APA7) >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 3:29 PM

- URL: https://nist.libguides.com/citeandreference

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.6: Quoting and Paraphrasing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 120102

- Amy Guptill

- The College at Brockport, SUNY

Media Alternative

Listen to an audio version of this page (15 min, 22 sec):

We have seen that paragraphs need supporting sentences, but how specifically can we bring in quotations and paraphrases of other sources into our own essay?

Listen to your sources

Have you ever had the maddening experience of arguing with someone who twisted your words to make it seem like you were saying something you weren’t? Novice writers sometimes inadvertently misrepresent their sources when they quote very minor points from an article or even positions that the authors of an article disagree with. It often happens when students approach their sources with the goal of finding snippets that align with their own opinion. For example, the passage above contains the phrase “measuring teachers’ performance by student test scores is the best way to improve education.” An inexperienced writer might include that quote in a paper without making it clear that the author(s) of the source actually dispute that very claim. Doing so is not intentionally fraudulent, but it reveals that the paper-writer isn’t really thinking about and responding to claims and arguments made by others. In that way, it harms his or her credibility.

Academic journal articles are especially likely to be misrepresented by student writers because their literature review sections often summarize a number of contrasting viewpoints. For example, sociologists Jennifer C. Lee and Jeremy Staff wrote a paper in which they note that high-schoolers who spend more hours at a job are more likely to drop out of school. 1 However, Lee and Staff’s analysis finds that working more hours doesn’t actually make a student more likely to drop out. Instead, the students who express less interest in school are both more likely to work a lot of hours and more likely to drop out. In short, Lee and Staff argue that disaffection with school causes students to drop-out, not working at a job. In reviewing prior research about the impact of work on dropping out, Lee and Staff write “Paid work, especially when it is considered intensive, reduces grade point averages, time spent on homework, educational aspirations, and the likelihood of completing high school” 2 . If you included that quote without explaining how it fits into Lee and Staff’s actual argument, you would be misrepresenting that source.

Provide context

Another error beginners often make is to drop in a quote without any context. If you simply quote, “Students begin preschool with a set of self-regulation skills that are a product of their genetic inheritance and their family environment” (Willingham, 2011, p.24), your reader is left wondering who Willingham is, why he or she is included here, and where this statement fits into his or her larger work. The whole point of incorporating sources is to situate your own insights in the conversation. As part of that, you should provide some kind of context the first time you use that source. Some examples:

Willingham, a cognitive scientist, claims that …

Research in cognitive science has found that … (Willingham, 2011).

Willingham argues that “Students begin preschool with a set of self-regulation skills that are a product of their genetic inheritance and their family environment” (Willingham, 2011, 24). Drawing on findings in cognitive science, he explains “…”

As the first example above shows, providing a context doesn’t mean writing a brief biography of every author in your bibliography—it just means including some signal about why that source is included in your text.

Quoted material that does not fit into the flow of the text baffles the reader even more. For example, a novice student might write,

Schools and parents shouldn’t set limits on how much teenagers are allowed to work at jobs. “We conclude that intensive work does not affect the likelihood of high school dropout among youths who have a high propensity to spend long hours on the job” (Lee and Staff, 2007, p. 171). Teens should be trusted to learn how to manage their time.

The reader is thinking, who is this sudden, ghostly “we”? Why should this source be believed? If you find that passages with quotes in your draft are awkward to read out loud, that’s a sign that you need to contextualize the quote more effectively. Here’s a version that puts the quote in context:

Schools and parents shouldn’t set limits on how much teenagers are allowed to work at jobs. Lee and Staff’s carefully designed study found that “intensive work does not affect the likelihood of high school dropout among youths who have a high propensity to spend long hours on the job” (2007, p. 171). Teens should be trusted to learn how to manage their time.

In this latter example, it’s now clear that Lee and Staff are scholars and that their empirical study is being used as evidence for this argumentative point. Using a source in this way invites the reader to check out Lee and Staff’s work for themselves if they doubt this claim.