Planning and Conducting Health Education for Community Members

Health education is any combination of learning experiences designed to help individuals and communities improve their environmental health literacy. The goals of health education are to increase awareness of local environmental conditions, potential exposures, and the impacts of exposures on individual and public health. Health education can also prepare community members to receive and better understand the findings of your public health work.

Some health education takes the form of shorter, one-on-one, or small group conversations with community members, state, territorial, local, and tribal (STLT) partners, and stakeholders. In the beginning of your public health work, you may need to constantly educate community members about exposure sources and exposure pathways –that is, how they may encounter harmful substances.

Later in your public health work, you may want to do a full community workshop or participate in existing community events to increase understanding about specific exposures related to the chemical of concern. Be sure to address how the harmful substance may be encountered, levels of exposure, and ways community members can prevent, reduce, or eliminate exposure. There may be other concerns that are not chemical-specific, such as environmental odors and community stress.

Health education is a professional discipline with unique graduate-level training and credentialing. Health educators are critical partners that advise in the development and implementation of health education programs. Public health work benefits from the skills that a health educator can provide. (See resource: What Is a Health Education Specialist? external icon ) If you don’t have this training, see what you can do to build your skills and improve your one-on-one and small group educational conversations. Health educators may also work with other public health professionals such as health communication specialists. Health communication specialists develop communication strategies to inform and influence individual and community decisions that enhance health.

- Assess individual and community needs for health education. (See activity: Developing a Community Profile )

- Ask community members about factors that directly or indirectly increase the degree of exposure to environmental contamination. Factors may include community members accessing a hazardous site or the presence of lead in house paint, soil, or water.

- Develop a health education plan.

- Listen for opportunities to provide health education throughout your community engagement work.

Despite nearby mines being shut down, a tribal nation continued to face risks of exposure to uranium and radon. To help the community better understand how to reduce the risk of exposure, a group of federal and tribal agencies developed a uranium education workshop. The agencies established a vision and a set of strategies to ensure the workshop was technically-sound and culturally appropriate.

The agencies ensured that they

- Offered the workshop in English and tribal languages,

- Developed materials at the average US reading level for broad accessibility,

- Invited all local tribal families to participate, and

- Piloted the workshop with three communities before finalizing the content.

Before the first pilot workshop, the agencies sought feedback on content, tone, and complexity from community health representatives from the tribe’s department of health. The community health representatives provided many suggestions to tailor the presentation for tribal community audiences.

The workshop content was further refined after each pilot presentation. Working with local professionals and offering workshops as pilot sessions enabled the agencies to tailor content to the needs, preferences, and beliefs of local community members.

CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH) and ATSDR have many existing materials to help educate community members about specific chemicals. ATSDR’s Toxicological Profiles and Tox FAQs provide a comprehensive summary and interpretation of available toxicological and epidemiological information on a substance. ATSDR’s Choose Safe Places for Early Care and Education Program provides a framework and practices to make sure early care and education sites are located away from chemical hazards. Consider leveraging or adapting these resources, as well as the following chemical-specific websites and interventions, when developing health education activities for your community, such as

- NCEH’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program Website

- ATSDR’s soilSHOP Toolkit —A toolkit to help people learn if their soil is contaminated with lead

- ATSDR’s Don’t Mess with Mercury — Mercury spill prevention materials for schools

Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS):

- ATSDR’s PFAS Website

As noted above there may be other concerns that are not chemical-specific, such as environmental odors and community stress. Some helpful resources to address these concerns can be found here:

- ATSDR Environmental Odors

- ATSDR Community Stress Resource Center

Develop health education materials that are culturally appropriate, with community input.

Be aware that your health education messages may be received by the community differently than you intend. Consider testing your messages with community counterparts before you use them widely. Be aware of community beliefs about health and the environment, so that you can develop culturally appropriate health education materials. Your awareness will help you design, plan, and implement activities that are protective of health and respectful of community beliefs. (See callout box: Cultural Awareness )

Avoid stigmatizing (devaluing) communities living in “contaminated” areas [ ATSDR 2020 ].

- CDC Learning Connection (CDC). A source for information about public health training.

- Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum (CDC). A list of characteristics that you can use to develop an effective health education curriculum.

- Community Environmental Health Education Presentations (ATSDR). A collection of presentations designed for health educators to use in face-to-face sessions with community members to increase environmental health literacy.

- Promoting Environmental Health in Communities (ATSDR). A guide that includes talking points, PowerPoint presentations, and covers the basic concepts of the environment, toxicology, and health.

- What is a Health Education Specialist? external icon (Society for Public Health Education – SOPHE): A description of a health education specialist including areas of responsibility and competency.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Search form

Schedule an Appointment Apply Online Current Student Resources

- Master of Business Administration

- Master of Science in Nursing

- Master of Public Health

- Master of Science in Management and Organizational Behavior

- Dual MPH/Master of Science in Management and Organizational Behavior

- Dual MSN/Master of Business Administration

- Dual MBA/Master of Public Health

- Graduate Certificate in Health Education and Promotion

- Graduate Certificate in Health Management and Policy

- Graduate Certificate in Epidemiology

- Graduate Certificate in Data Analytics

- Post Master's Nurse Educator Certificate

- Post Master's Nurse Executive Leader Certificate

- Graduate Certificate in Change Management

- Graduate Certificate in Digital Marketing

- Graduate Certificate in Project Management

- Graduate Certificate in Talent Management

- Undergraduate Programs

- RN to Bachelor of Science in Nursing

- Other Benedictine Programs:

- On Campus Programs

- Hybrid Programs

- Admission Requirements

- Admission Process

- Financial Aid

- Scholarships & Awards

- Military Students

- International Students

- Virtual Open House

- Course Experience

- Support Services

- Student Orientation

- Alumni Community

- Professional Development

- Online Student BENefits

- Why Choose Benedictine University

- Mission & Values

- Accreditation

- Request Info

Impact Lives

Empowering communities with health education.

Public health officials are constantly working to inform, educate and empower communities about health issues to encourage a healthier way of life. Through educational programs, these professionals strive to inspire communities to make better health choices. There are many different strategies for effective health education in communities to promote interaction and raise awareness on the elements of health related issues. Through effective health education strategies, public health officials can make a considerable impact on the overall health and knowledge within communities.

What is Public Health?

Public Health is described as the science of protecting and improving the health of communities through education, promotion of healthy lifestyles and research for disease and injury prevention. Professionals in Public Health study health related concerns that are potentially affecting communities and work to find ways to educate individuals to avoid health risks.

This field deals with health issues impacting communities as whole. Compared to traditional medical professionals who work on an individual basis, public health officials treat communities as their patients, whether it is on a global scale or local neighborhood. Main duties of a public health official involve conducting research and sharing their findings by implementing educational programs to prevent problems from occurring.

Increasing Health Literacy

Nearly nine out of 10 adults have difficulty using everyday health information that is routinely available in health care facilities. Defined as the ability to process and understand basic health information needed to make informed health decisions, health literacy requires skills to break down that information. This involves calculating numbers to determine things such as cholesterol and sugar levels, measuring medication and understanding nutrition labels. Poor literacy skills have been associated with higher health care expenses by affecting a patient’s capability to effectively use available information to implement health behaviors or respond to health warnings.

National Action Plan

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services developed the National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy with the goal of creating a society that:

- Provides everyone access to accurate, actionable health information

- Delivers person-centered health information and services

- Supports life-long learning and skills to promote good health

The Action Plan is based on the idea that each individual has the right and need to access health information that will assist in making informed decisions as well as the need for health services to be provided in a way that can be easily understood by the average citizen and beneficial in encouraging health, longevity and quality of life. The seven goals in the plan include:

- Develop and disseminate health and safety information that is accurate, accessible and actionable.

- Promote changes in the health care delivery system that improve information, communication, informed decision-making and access to health services.

- Incorporate accurate and standards-based health and developmentally appropriate health and science information and curricula into child care and education through the university level.

- Support and expand local efforts to provide adult education, English-language Instruction, and culturally and linguistically appropriate health information services in the community.

- Build partnerships, develop guidance and change policies.

- Increase basic research and the development, implementation, and evaluation of practices and interventions to improve health literacy.

- Increase the dissemination and use of evidence-based health literacy practices and interventions.

Educational and Community-Based Programs

Health educators attempt to bridge the gap between distributed information and the public by developing effective educational programs for communities to prevent disease and injury, improve health and enhance the quality of life. These programs play a key role in reaching people outside of traditional health care settings such as schools, worksites and hospitals.

For a community to effectively improve its health, changes are often needed in physical, social, organizational and political environments in order to adjust factors that could be contributing to health problems. For example, communities may need to implement new programs or policies to change community norms in order to promote better health.

These programs work to educate communities on issues such as:

- Chronic diseases

- Mental illness/behavioral health

- Unintended pregnancies

- Nutrition and obesity prevention

- Substance abuse

Through successful education programs that use proper cultural communication methods, public health professionals are able to promote policy change and advocacy for better health education in communities. Health educators are constantly working to ensure that individuals have a clear understanding of how life choices affect health status. For those interested in being involved in the education of communities to promote health education, Benedictine University offers an online Master of Public Health ( MPH ) with a 35-year legacy as well as a specialized certificate in Health Education and Promotion .

Related Benedictine Programs

With the proper stress management, a health care career in nursing is one of the most rewarding careers available. Benedictine University offers an online accredited Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) degree for those looking to advance their nursing careers while juggling their busy work and personal schedules. To learn more click here or talk with one of our Program Advisors today.

- Donate to BMCC

- About BMCC Home

- Mission Statement and Goals

- College Structure and Governance

- Our Students

- Faculty and Academics

- Campus and NYC

- College Administration

- Institutional Advancement

- History of BMCC

- Public Affairs

- Institutional Effectiveness and Analytics

- Race, Equity and Inclusion

- Admissions Home

- BMCC and Beyond

- Visit Our Campus

- Request Information

- After You Are Admitted

- First-Time Freshmen

- Transfer Students

- Evening/Weekend Programs

- Students Seeking Readmission

- Non Degree Students

- Military and Veterans

- Adult Learners

- International Students

- Academic Affairs

- Academic Departments

- Academic Programs

- Success Programs

- Course Listings

- Learning Options

- Course Schedule

- Honors and Awards

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Advisement

- Activities & Athletics

- Administration and Planning

- Compliance & Diversity

- Financial Aid

- Human Resources

- Information Resources and Technology

- Panther Station

- Public Safety

- Sponsored Programs

- Student Affairs

- The Heights

- Continuing Ed

- Faculty/Staff Resources

- BMCC Experts

- Faculty Affairs

- Student Email

- Faculty/Staff Outlook

- BMCC Portal

- Brightspace (coming Summer 2024)

- DegreeWorks

- Connect2Success

- Linkedin Learning

- Faculty Pages

Reimagining BMCC

Monitoring and Reporting Positive Cases

- Health Education

Community Health Education (A.S.)

- Mission Statement

Programs Offered

- Community Health Education

- Gerontology

- School Health Education

- Public Health

BMCC Admissions

or learn more .

The Community Health Education program will teach you to positively influence the health behavior of individuals, groups and communities. You will also learn to address lifestyle factors (i.e., nutrition, physical activity, sexual behavior and drug use) and living conditions that influence health. Community Health Education is the study and improvement of health characteristics among specific populations. Community health is focused on promoting, protecting and improving the health of individuals, communities, and organizations.

The program focuses on career preparation and teaching individuals and groups how to better care for themselves. The Community Health Education degree is a general health degree that prepares you to work in hospitals, community-based organizations, wellness centers or the fitness industry. It provides a foundation for careers in health promotion, disease prevention, fitness, health education and healthcare administration. It is also an entry point for those interested in pursuing clinical degrees.

Transfer Options

You will have the option to transfer to CUNY colleges such as York, Hunter, Lehman and Brooklyn College or to private schools such as Long Island University Brooklyn and Hofstra to major in Community Health Education, Health Administration, Public Health, Gerontology, Physical Therapy, Exercise Science, or Nursing. BMCC has articulation agreements with several four year colleges to allow you to seamlessly continue your education studies there.

Explore Careers

BMCC is committed to students’ long-term success and will help you explore professional opportunities. Undecided? No problem. The college offers Career Coach for salary and employment information, job postings and a self-discovery assessment to help students find their academic and career paths. Visit Career Express to make an appointment with a career advisor, search for jobs or sign-up for professional development activities with the Center for Career Development. Students can also visit the Office of Internships and Experiential Learning to gain real world experience in preparation for a four-year degree and beyond. These opportunities are available to help BMCC students build a foundation for future success.

Professor Lisa Grace Program Coordinator [email protected]

Related Communities

This program is offered in-person, online and in a hybrid format.

Requirements

Community health education academic program maps.

- Community Health Education Program 2 Year Plan

- Community Health Education Program 5 Semester Plan

Required Common Core

Flexible core 3, curriculum requirements, program electives (areas of study).

Choose 12 credits from 1 area of study below:

Health Education and Promotion

Food studies, exercise science, health services administration, health communication, health education electives.

Choose 1 course (3-4 credits) from:

Please note, these requirements are effective the 2021-2022 catalog year. Please check your DegreeWorks account for your specific degree requirements as when you began at BMCC will determine your program requirements.

- Consult with an advisor on which courses to take to satisfy these areas.

- These areas can be satisfied by taking a STEM variant.

- No more than two courses in any discipline or interdisciplinary field can be used to satisfy Flexible Core requirements.

Health Education Department

199 Chambers Street, Room N-798 New York, NY 10007 Phone: (212) 220-1453

Office Hours: Monday-Friday 9 a.m.-5 p.m

Borough of Manhattan Community College The City University of New York 199 Chambers Street New York, NY 10007 Directions (212) 220-8000 Directory

Notice of Non-Discrimination

Bookstore News Event Calendar Job Opportunities Human Resources Admissions Library Give to BMCC Accessibility Virtual Tour Academic Policies Privacy Policy

Information for: Students Faculty & Staff Alumni

Social Media Directory

Educational and Community-Based Programs Workgroup

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP)

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

Members of the Educational and Community Based Programs (ECBP) Workgroup have expertise in areas including school-based health centers, K-12 school and workplace health programs and policies, and medical/allied professions training curricula. They developed the objectives related to educational and community-based programs, and they’ll provide data to track progress toward achieving these objectives throughout the decade.

Read more about the Educational and Community-Based Programs Workgroup

Objective Status

Learn more about objective types

Educational and Community-Based Programs Workgroup Objectives (14)

About the workgroup, approach and rationale.

Educational and community-based programs and strategies are designed to reach people outside of traditional health care settings. These settings may include:

- Community-based organizations

Each setting provides opportunities for people to interact with physical and programmatic structures on a regular basis.

The core objective selected by the ECBP Workgroup aims to increase participation in daily school physical education by helping schools create a strong, evidence-based foundation for physical education programs.

The developmental objectives focus on kindergarten to 12th-grade health interventions, medical and allied health preparation programs, community-based organization prevention services, and worksite health promotion programs. As more data become available, these developmental objectives may become core objectives.

Understanding Educational and Community-Based Programs

Health and quality of life rely on interwoven community systems and factors — not simply on a well-functioning health and medical care system. Making changes within existing systems, like improving school health programs and policies, can effectively optimize the health of many people in a community.

Chronic diseases like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes are the leading causes of death and disability in the United States. They’re also leading drivers of the nation’s annual health care costs. 1 Promoting health in workplaces and community-based organizations, establishing healthy habits in school-age children, and including public health education in medical and allied health preparation programs can directly address this burden.

To improve community health, it’s often necessary to change aspects of the physical, social, organizational, and even political environments to eliminate or reduce factors that contribute to health problems — and to introduce new elements that promote better health. These changes may include:

- Instituting new programs, policies, and practices

- Changing aspects of the physical or organizational infrastructure

- Changing community attitudes, beliefs, or social norms 2

Emerging issues in Educational and Community-Based Programs

- Adopting a Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) approach to reduce dropout rates. The WSCC model is CDC’s framework for addressing health in schools. The WSCC model is student-centered and emphasizes the role of the community in supporting the school, the connections between health and academic achievement, and the importance of evidence-based school policies and practices.

- Establishing an evidence base for community health and education policy interventions to determine their impact and effectiveness.

- Increasing the number of community health and other auxiliary public health workers — and building their skill level — to support healthier communities.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). About Chronic Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm

Institute of Medicine. (2003). The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221239

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Community Health Education Strategies: Student Experiences

- June 23, 2021

- Health@Emory , Read

Editor’s Note: This summer, Exploring Health will feature posts from students within the Health 1,2,3,4 program’s Health 497 course — Community Health Education Strategies. This piece is an introduction to student blog posts about their experiences participating in the course.

Health 1,2,3,4 is an academic program housed within the Center for the Study of Human Health at Emory University. The four-course series aims to provide students with strategies and resources to play an active role in their own health, while also equipping them with the skills to promote the health of their peers. Â In addition to growing their knowledge of the science of health and strategies for health promotion, students who complete courses within the Health 1,2,3,4 program walk away with tangible skills that prepare them for a wide range of careers or educational programs after graduation.

Recognizing the need for students to translate the skills and knowledge acquired in the Human Health courses, the Health 1,2,3,4 program introduced a new course for the 2020-2021 academic year: Health 497 — Community Health Education Strategies. Â In this two-part course (Fall and Spring semesters), students apply their understanding of health education principles and strategies to develop and facilitate the delivery of health education with collaborative partners in the Atlanta and Emory communities. Students who participate in the course are provided with the opportunity to develop professional skills, including leadership, discussion facilitation, communication, and more. Â This year, Health 497 offered two paths for the students to pursue: group coaching to support Healthy Emory’s Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and health education lessons for Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School .

Healthy Emory’s Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Group Coaching Path

Developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Healthy Emory’s Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) enables Emory employees with pre-diabetes to modify their behaviors to prevent the progression of the disease. Partnering with Healthy Emory, Health 497 provided optional, student-led group coaching sessions to support DPP participants in maintaining healthy behaviors and reaching their health goals. Students within the Health 497 DPP path trained to become student health coaches, developing and facilitating group coaching support sessions on four different topics: food logging, physical activity, embracing a problem-solving mindset, and overcoming social obstacles to healthful nutrition. By participating in the group coaching support sessions, DPP participants revisited key components of the DPP curriculum, discussed personal health barriers, and developed specific goals to promote well-being.

Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School Health Education Path

The Health 1,2,3,4 program maintains a collaborative partnership with Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School to provide health education to its 6 th -8 th grade student population. Students who pursued the Health 497 King Middle School path developed and facilitated lesson plans on several health-related topics, including nutrition, positive mental health, and time and energy management. The middle school students who participated in the health lessons expanded their understanding of health and health-promoting behaviors.

It is with great pleasure that we share the personal experiences and reflections of our Health 497 students within their specific paths to highlight the impact this course has had on their academic and professional growth. Stay tuned for the student pieces as they are posted in the Exploring Health blog this summer.

To learn more about the Health 1,2,3,4 program, visit the program webpage. For more information about collaborative partnership opportunities, contact program director Lisa DuPree at [email protected] .

Related Posts

- previous post: Hunting for a Dose

- next post: Becoming a Student Health Coach

Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Module: 12. Planning Health Education Programmes: 1

Study session 12 planning health education programmes: 1, introduction.

Careful planning is essential to the success of all health education activities. This study session is the first of two sessions that will help you to learn about ways in which you can plan your health education activities. In this study session, you will learn about the purpose of planning health education interventions, the basic concepts of planning, and what steps to take when you are planning. The study session will focus in particular on needs assessment, which is the first step in planning health education and promotion. You will learn about categories of needs and techniques that you can use when carrying out needs assessment.

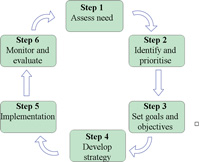

You may have covered some aspects of planning in other modules such as the Health Management, Ethics and Research Module. However, planning in this study session refers specifically to the health education planning process (Figure 12.1).

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 12

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

12.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold . (SAQs 12.1 and 12.2)

12.2 Explaiin the purpose of planning health education activities. (SAQ 12.2)

12.3 List the principles of planning in health education practice. (SAQ 12.2)

12.4 Describe the six steps of planning health education interventions. (SAQ 12.3)

12.5 Describe the main categories of needs assessment. (SAQs 12.4 and 12.5)

12.5 Discuss some of the techniques of needs assessment. (SAQs 12.4 and 12.6)

12.1 Planning health education activities

Before you can begin planning your health education activities, you need to have a clear understanding of what planning means. Planning is the process of making thoughtful and systematic decisions about what needs to be done, how it has to be done, by whom, and with what resources. Planning is central to health education and health promotion activities (Box 12.1). If you do not have a plan, it will not be clear to you how and when you are going to carry out necessary tasks. Everyone makes plans — for looking after their family, for cooking, and so on. You can build on experience you already have in planning, and apply it to health education.

Box 12.1 Key questions to ask when planning

- What will be done?

- When will it be done?

- Where will it be done?

- Who will do it?

- What resources are required?

12.2 The purpose of planning in health education

There are several benefits to planning your activities. Firstly, planning enables you to match your resources to the problem you intend to solve (Figure 12.2). Secondly, planning helps you to use resources more efficiently so you can ensure the best use of scarce resources. Thirdly, it can help avoid duplication of activities. For example, you wouldn’t offer health education to households on the same topic at every visit. Fourthly, planning helps you prioritise needs and activities. This is useful because your community may have a lot of problems, but not the resources or the capacity to solve all these problems at the same time. Finally, planning enables you to think about how to develop the best methods with which to solve a problem.

Haimonot is a Health Extension Practitioner. She is working at a health post near your village. Haimonot is doing health education activities — but not planning them. How would you convince her that planning health education activities would be helpful? What points would you want to talk about? Use the paragraph above to help you plan what you want to say.

To convince Haimonot to plan her own health education activities, you could explain the purpose of planning to her. You could explain that:

- Planning will make it easier for her to identify what she needs to do, and be more efficient in her work.

- Planning would help her to prioritise the health problems in her community that need intervention.

- Planning would help her choose the problems that are most important, and to match resources with the problems she intends to address. This would enable her to use her scarce resources more efficiently, and avoid unnecessary activities.

12.3 Principles of planning in health education

In this section you will learn about the principles you should apply when planning any activity in the community. Planning is not haphazard — that means there is a principle, or a rule, which you should take into account when developing your health education plans. You should always consider the principles shown in Box 12.2 when you plan a piece of work.

Box 12.2 Six principles of planning in health education

- It is important that plans are made with the needs and context of the community in mind. You should try to understand what is currently happening in the community you work in.

- Consider the basic needs and interests of the community. If you do not consider the local needs and interests, your plans will not be effective.

- Plan with the people involved in the implementation of an activity. If you include people they will be more likely to participate, and the plan will be more likely to succeed.

- Identify and use all relevant community resources.

- Planning should be flexible, not rigid. You can modify your plans when necessary. For example, you would have to change your priorities if a new problem, needing an urgent response, arose.

- The planned activity should be achievable, and take into consideration the financial, personnel, and time constraints on the resources you have available. You should not plan unachievable activities.

Meserete is a Health Extension Practitioner. Some time ago she developed a health education programme for her community. At the beginning, she identified some important health problems that were occurring in her community. Local people were recruited to identify their own health problems, and to look for a solution appropriate to their setting. Meserete also identified local resources that would be helpful for her health education activities. Finally, she developed a plan to meet the needs of the community and started to implement it. However, she faced a shortage of resources to carry out all of the items in her plan, so she prioritised the items and modified her plan according to the resources that were available. Look at Box 12.2 above, and work out which principles of planning you think Meserete used.

Meserete has worked well, and used all the principles of planning. She understood local problems [principle 1], and considered the interests of the community [2]. Local people participated in the programme at all stages [3]. She also identified local resources for her health education programme [4], and made sure that her plan was flexible [5]. Meserete also modified her plan, and she thought very carefully about what was achievable [6].

12.4 Steps involved in planning health education activities

Planning is a continuous process. It doesn’t just happen at the start of a project. If you are involved in improving and promoting individual, family and community health, you should make sure that you plan your activities. Planning can be thought of as a cycle that has six steps (Figure 12.3). In this section, you will learn the basic steps to take when planning your health education activities.

12.5 Needs assessment

Conducting a needs assessment is the first, and probably the most important, step in any successful planning process. Sufficient time should be given for each needs assessment. The amount of time required for a needs assessment will depend on the time you have available to address the problem, and the nature and urgency of the problem being assessed.

Needs assessment is the process of identifying and understanding the health problems of the community, and their possible causes (Figure 12.4). The problems are then analysed so that priorities can be set for any necessary interventions. The information you collect during a needs assessment will serve as a baseline for monitoring and evaluation at a later stage.

Before you begin a needs assessment, it is important to become familiar with the community you are working in. This involves identifying and talking with the key community members such as the kebele leaders, as well as religious and idir leaders. Ideally, you would involve key community members throughout the planning process, and in the implementation and evaluation of your health education activities.

There are various categories of needs assessment. In order to develop a workable and appropriate plan, several types of needs should be identified, including health needs and resource needs, which are outlined below.

12.5.1 Health needs assessment

In a health needs assessment , you identify health problems prevalent in your community. In other words, you look into any local health conditions which are associated with morbidity, mortality and disability. The local problems may include malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS, diarrhoea, or other conditions arising from the local context, such as goitre caused by lack of iodine in the diet.

Having identified the problems, you need to think about the extent to which local health conditions are a result of insufficient education. For example, are people lacking in knowledge about malaria, or HIV, or diarrhoea? Are they aware that some of their behaviours may be part of the problem?

12.5.2 Resource needs assessment

A resource needs assessment identifies the resources needed to tackle the identified health problems in your community. You should consider whether there is a lack of resources or materials that is preventing the community from practising healthy behaviours. For example, a mother may have good knowledge about malaria and its prevention methods, and want to use Insecticide Treated Bed Nets (ITNs). However, if ITNs are not available, it may not be possible for her to avoid malaria. Therefore, a bed net is a resource which is required to bring about behaviour change. Similarly, a woman may intend to use contraception. However, if contraceptive services are not available in her locality, she remains at risk of unplanned pregnancies. In order to facilitate behaviour change, you should identify ways of addressing this lack of contraceptive resources.

Be aware too that education is in itself one of the great resources you can call on. An education needs assessment should also be part of you plan.

12.5.3 Community resources

First read Case Study 12.1 to help you think about community needs.

Case Study 12.1 Tigist

Ms Tigist is a Health Extension Practitioner. She has been working for three years in a village called Burka. She has conducted a needs assessment in order to develop an appropriate health education plan. During the needs assessment, Ms Tigist identified that malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS and harmful traditional practices, such as female genital mutilation (FGM), were prevalent problems in the village. In addition, she identified that many community members did not know the causes of these problems, or any methods of prevention. For example, many young people did not like to use condoms, and many households did not use bed nets properly due to lack of knowledge. Ms Tigist also identified that many households did not own bed nets.

During a needs assessment, you also need to identify the resources available in the community, such as labour power. This would include finding out about the help that community leaders and volunteers could give, and the local materials and spaces in which to conduct health education sessions. When looking at community resources, you should include local information such as the number of people in each household, their ages and their economic characteristics. You would also include information on community groups and their impact on local health activities and communication networks.

Read Case Study 12.1 again, and then answer the questions below.

- a. Which categories of needs assessment has Ms Tigist conducted?

- b. List the problems Ms Tigist has identified in each of the categories of needs assessment.

a. Ms Tigist has undertaken a health needs assessment (look at Section 12.5.1 if you need to clarify this), and a resource needs assessment (see Section 12.5.2).

b. Problems identified in the health needs assessment showed that malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS and harmful traditional practices were prevalent, and that there is a lack of knowledge about causes and prevention methods for these problems. The main resource need identified was mosquito bed nets in some households.

If you identify malaria as a common health problem in your locality, what additional information would you need in order to plan and implement an appropriate intervention? You will find that looking at Section 12.5.2 again should help here. The important information you need to consider is the effect of current behaviours on the health problem you have chosen.

You should conduct a further assessment for this specific disease to identify the reasons why malaria is a problem in your locality. Knowing it is a problem is only the start. You may identify behavioural factors such as not using bed nets, not seeking timely treatment, or not clearing stagnant water around the dwellings. When all these behavioural factors have been identified, proper health education strategies can be developed to address them, including resources that are needed, and whether you can get them.

12.6 Assessment techniques

Data related to the health needs of the community can be obtained from two main sources — these are called primary and secondary sources . Primary sources are data which you collect during a needs assessment, using techniques such as observation, in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, and focus group discussions. Secondary sources are data that were collected and documented for other purposes, including health centre and health post records, activity reports, and research reports. You may also be able to review data which has already been collected by other people to identify local health problems.

Think about a health education issue you are aware of in your community. Make a list of primary and secondary sources of information you could collect on this issue.

You could collect primary information by conducting some interviews with key people in your community, or holding focus group discussions. Secondary sources of information about the health issue may be available from your local health centre, or health post data.

Various techniques can be used to collect data from the community. These include observation, in-depth interviews, key informant interviews, and focus group discussions — which we describe next.

12.6.1 Observation

To carry out an o bservation , you watch and record events as they are happening. Box 12.3 outlines some situations where observation can be a useful method of collecting relevant data.

Box 12.3 Observation is useful to understand

- Community cultures, norms and values in their social context.

- Human behaviour that may be complex and hidden.

When you are observing households, individuals, or more general practice or behaviour in your community, you may find it useful to use a checklist. For example, you could prepare a checklist to keep a detailed record of household practice and environmental hygiene. Following your checklist might help you to be more systematic about the things you are observing. You cannot observe everything at the same time, so the checklist will help you prioritise what to observe, and how to record what you have seen. A checklist is a very helpful tool for observation, and more generally with planning. There is an example of a checklist in Box 12.4.

Box 12.4 Checklist to organise observations

A Health Extension Practitioner has prepared a checklist to help organise her observations when she visits pregnant mothers in her community to put up new insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs).

The checklist includes the following points:

- Is the net hung above the bed? Yes/No

- Has it been tied at all four angles above the bed? Yes/No

- Is the net tucked under the mattress? Yes/No

- Does the net have a hole anywhere where an insect might get in? Yes/No

You have probably already gathered a lot of information by using observation within your community. If you keep alert to all the things that are happening around you, you will be able to gather a lot of very useful information. Systematically observing and recording what you see is an important technique that you can use to identify health problems and their possible causes (Figure 12.5).

Observation is a real skill, and one you can practise very easily. Make a list of a number of small observations you can make in the next week or so. It doesn’t even have to be work related! Then just try a few out, and make a brief checklist for each.

You could observe how many people greet you over one half-hour period, and make a note of how they do it. You could observe how many bicycles go past in ten minutes and the age of the people riding them. Or choose an observation on health education. The important thing is to really pay attention, and then make some sort of record.

12.6.2 Interviews

The in-depth interview is another important method of data collection. This technique can be used when you want to explore individual beliefs, practices, experiences and attitudes in greater detail. It is usually conducted as a direct personal interview with one person — a single respondent. Using in-depth interviews as a Health Extension Practitioner, you can discover an individual’s motivations, beliefs, attitudes and feelings about health and illness. For example, you may want to explore a mother’s attitudes to — and use of — contraception.

It is a good idea to use open-ended questions to encourage the respondent to talk, rather than closed questions that just require a yes or no answer.

An in-depth interview can take around 30–90 minutes. Box 12.5 lists the steps you should take when conducting an in-depth interview.

Box 12.5 Conducting an in-depth interview

- Identify an individual with whom you are going to conduct an in-depth interview, obtain their consent and arrange a time.

- Prepare your interview guide — this is a list of questions you can use to guide you during the interview. You can generate more questions during the interview if other issues arise that you want to follow up.

- Write down the responses as accurately as you can. You can also use a tape recorder to record the responses. However, you should ask permission from the respondent to use a tape recorder.

- After the interview is completed, review your notes or listen to the tape and prepare a detailed report of what you have learned.

Perhaps you could practise inventing open-ended questions. Try it out on your family and friends until it becomes easy to do. A closed question goes like this: Do you like vegetables? The person can only really say yes or no. An open question goes like this: Tell me something about how vegetables fit into your diet? Then the person can start talking about vegetables much more — and you will get a lot more information.

A good time to do an in-depth interview is when the subject matter is sensitive; for example, gathering data from women regarding their feelings about sexuality and family planning, or if the woman has had an abortion. This is a useful technique when you need to explore an individual’s experiences, beliefs and attitudes in greater detail.

12.6.3 Key informants

Key informants are people who have first-hand knowledge about the community. They include community leaders, cultural leaders, religious leaders, and other people with lots of experience in the community. These community experts, with their particular knowledge and understanding, represent the views of an important sector of the community. They can provide you with detailed information about the community, its health beliefs, cultural practices, and other relevant information that might help you in your work. How do you feel about talking to leaders and people with lots of experience? Do you ask them different sorts of questions from those you ask of other people? Although beliefs and attitudes apply to key informants too, you also have a chance to find out some answers to questions about ‘the bigger picture’ of your community when people are public figures.

12.6.4 Focus group discussions

Focus g roup d iscussion s are group discussions where around 6 to 12 people meet to discuss health problems in detail. The discussion is led by a person known as a ‘facilitator’. Box 12.6 describes the steps to use if you want to conduct a focus group discussion.

Box 12.6 Conducting a focus group discussion

- Select 6–12 participants for your focus group discussion. For the discussion of some sensitive issues, it might be necessary to lead one focus group of men only (Figure 12.7), and another of women only. For other issues, a mixed group could lead to interesting and informative discussions.

- Prepare a focus group discussion guide. This is a set of questions which are used to facilitate the discussion. While the discussion is going, you can also generate more questions to ask the participants.

- There should be one person who facilitates the discussion, and another person who takes notes during the discussion. If possible, it is also useful to record the discussion using a tape recorder, so that you can listen and analyse it later.

You may find it useful to use focus group discussions in the following situations:

- When group interaction might produce better quality data. Interaction between the participants can stimulate richer responses, and allow new and valuable issues to emerge.

- Where resources and time are limited. Focus groups can be done more quickly, and are generally less expensive than a series of in-depth interviews.

In this study session, you have learnt four techniques that will help you to conduct needs assessments. You can either select one technique which best fits the aims of your needs assessment, or use a combination of more than one technique to build a more complete picture of the issues you need more information about.

Spend a few moments thinking about these four techniques. Do you feel more at home with one than another? Do you think it might be best to use more than one method with a particular health education issue?

You do not have to use all of these techniques all the time. Some work better in some situations. But it is worth practising, so that if and when you need a particular technique you have it at your finger tips.

Summary of Study Session 12

In Study Session 12, you have learned that:

- Planning is the process of making thoughtful and systematic decisions about what needs to be done, how it has to be done, by whom, and with what resources.

- Planning health education activities has several advantages. It enables you to prioritise problems, use your resources efficiently, avoid duplication of activities, and develop the most effective methods to solve community health problems.

- Planning should be based on your local situation, and take into account all the interests and needs of the community.

- A needs assessment is the usual starting point for the health planning process. There are a variety of techniques you can use for this, including observation, interviews and focus group discussions.

- No matter what techniques are used to conduct your health and resource needs assessments, the basic concept is to find out more about health problems in your community, and gather information about their underlying causes.

Planning is covered in more depth in Study Session 13.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 12

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 12.1 (tests Learning Outcome 12.1)

What do you think are the most important elements of:

- a. Health planning?

- b. Health needs assessment?

- a. Planning involves creative thinking. It is the process of making decisions about what needs to be done, when it will be done, where it will be done, who will do it, and with what resources. Planning is central to health education and health promotion activities.

- b. Needs assessment is the process of identifying and understanding the health problems in your community, and their possible causes. This is used to analyse problems and set priorities for intervention.

SAQ 12.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.1, 12.2 and 12.3)

Which of the following statements about planning health education activities are false ? In each case, explain what is incorrect.

A Planning should be rigid.

B Planning will create duplication of effort and activities.

C Planning should be based on the local situation.

D It is not important to consider the interests of local people when planning health education activities.

E We should not worry about the availability of resources when we plan our health education activities.

A is false because planning is not rigid. You can adjust or modify your plan at any time.

B is false, planning helps you avoid duplication of activities.

C is true because the local situation is the foundation for all planning. A plan which is not based on local facts cannot be a good plan.

D is false because engagement with the local community in health education activity is one of the core principles of planning. The interest and the needs of the community should be kept at the centre of planning.

E is false because a plan cannot be executed without sufficient resources. Resources are one of the important things that you should consider while planning health education activities.

SAQ 12.3 (tests Learning Outcome 12.4)

Below are the steps you need to go through when planning your health education activities, but they are not in the correct order. Match the steps to the numbers 1 to 6 in the order you should do them.

Needs assessment

Problem identification and prioritisation

Setting goals and objectives

Develop your strategy

Implementation

Monitoring and evaluation

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

SAQ 12.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.5 and 12.6)

Suppose you are asked to develop a health education plan for the community in which you are working. What are the three categories of needs assessment? What techniques might you use to conduct a health needs assessment?

Categories of needs assessment include health needs assessment, educational needs assessment, and resource needs assessment. In addition, information related to community resources and demographic characteristics should be collected during needs assessment.

Techniques of needs assessment include observation, in-depth interviews, key informant interviews and focus group discussions.

SAQ 12.5 (tests Learning Outcome 12.5)

Derartu has conducted a health needs assessment to develop her health education activity plan. She has assessed the following needs. Which category of need would you put each of these into?

- a. Lack of knowledge about the benefits of latrine use.

- b. Lack of skill in using insecticide-treated bed nets.

- c. Having a negative attitude towards condom use.

- d. Condoms are not available in the village.

- e. Belief that malaria is caused by drinking dirty water.

- a. Educational

- b. Educational

- c. Educational

- d. Resources

- e. Educational.

Read Case Study 12.1 about Ms Tigist again, to see how her needs assessment covered a range of issues.

SAQ 12.6 (tests Learning Outcome 12.6)

Match the correct descriptions with each of the needs assessment techniques.

Uses a checklist

Observation

Used to explore individual beliefs

In-depth interview

Used when the subject is not sensitive

Focus group discussion

Interviews with religious and other community leaders

Key informant

a. Key informant

b. In-depth interview

c. Observation

d. Focus group discussion

Except for third party materials and/or otherwise stated (see terms and conditions ) the content in OpenLearn is released for use under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Sharealike 2.0 licence . In short this allows you to use the content throughout the world without payment for non-commercial purposes in accordance with the Creative Commons non commercial sharealike licence. Please read this licence in full along with OpenLearn terms and conditions before making use of the content.

When using the content you must attribute us (The Open University) (the OU) and any identified author in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Licence.

The Acknowledgements section is used to list, amongst other things, third party (Proprietary), licensed content which is not subject to Creative Commons licensing. Proprietary content must be used (retained) intact and in context to the content at all times. The Acknowledgements section is also used to bring to your attention any other Special Restrictions which may apply to the content. For example there may be times when the Creative Commons Non-Commercial Sharealike licence does not apply to any of the content even if owned by us (the OU). In these stances, unless stated otherwise, the content may be used for personal and non-commercial use. We have also identified as Proprietary other material included in the content which is not subject to Creative Commons Licence. These are: OU logos, trading names and may extend to certain photographic and video images and sound recordings and any other material as may be brought to your attention.

Unauthorised use of any of the content may constitute a breach of the terms and conditions and/or intellectual property laws.

We reserve the right to alter, amend or bring to an end any terms and conditions provided here without notice.

All rights falling outside the terms of the Creative Commons licence are retained or controlled by The Open University.

Head of Intellectual Property, The Open University

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- NAM Perspect

- v.2020; 2020

Health Literacy and Health Education in Schools: Collaboration for Action

M. elaine auld.

Society for Public Health Education

Marin P. Allen

National Institutes of Health (ret.)

Cicily Hampton

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

J. Henry Montes

American Public Health Association

Cherylee Sherry

Minnesota Department of Health

Angela D. Mickalide

American College of Preventive Medicine

Robert A. Logan

U.S. National Library of Medicine and University of Missouri-Columbia

Wilma Alvarado-Little

New York State Department of Health

July 20, 2020

Introduction

This NAM Perspectives paper provides an overview of health education in schools and challenges encountered in enacting evidence-based health education; timely policy-related opportunities for strengthening school health education curricula, including incorporation of essential health literacy concepts and skills; and case studies demonstrating the successful integration of school health education and health literacy in chronic disease management. The authors of this manuscript conclude with a call to action to identify upstream, systems-level changes that will strengthen the integration of both health literacy and school health education to improve the health of future generations. The COVID-19 epidemic [ 10 ] dramatically demonstrates the need for children, as well as adults, to develop new and specific health knowledge and behaviors and calls for increased integration of health education with schools and communities.

Enhancing the education and health of school-age children is a critical issue for the continued well-being of our nation. The 2004 Institute of Medicine (IOM, now the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM]) report, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion [ 27 ] noted the education system as one major pathway for improving health literacy by integrating health knowledge and skills into the existing curricula of kindergarten through 12th grade classes. The NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy has held multiple workshops and forums to “inform, inspire, and activate a wide variety of stakeholders to support the development, implementation, and sharing of evidence-based health literacy practices and policies” [ 37 ]. This paper strives to present current evidence and examples of how the collaboration between health education and health literacy disciplines can strengthen K–12 education, promote improved health, and foster dialogue among school officials, public health officials, teachers, parents, students, and other stakeholders.

This discussion also expands on a previous NAM Perspectives paper, which identified commonalities and differences in the fields of health education, health literacy, and health communication and called for collaboration across the disciplines to “engage learners in both formal and informal health educational settings across the life span” [ 1 ]. To improve overall health literacy, i.e., “the capacity of individuals to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [ 42 ], it is important to start with youth, when life-long health habits are first being formed.

Another recent NAM Perspectives paper proposed the expansion of the definition of health literacy to include broader contextual factors, including issues that impact K–12 health education efforts like state rather than federal control of education priorities and administration, and subsequent state- or local-level laws that impact specific school policies and practices [ 39 ]. In addition to addressing individual needs and abilities, socio-ecological factors can impact a student’s health. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses a four-level social-ecological model to describe “the complex interplay” of (1) individuals (biological and personal history factors), (2) relationships (close peers, family members), (3) community (settings such as neighborhoods, schools, after-school locations), and (4) societal factors (cultural norms, policies related to health and education, or inequalities between groups in societies) that put one at risk or prevent him/her from experiencing negative health outcomes [ 11 ]. Also worth examining are protective factors that help children and adolescents avoid behaviors that place them at risk for adverse health and educational outcomes (e.g., self-efficacy, self-esteem, parental support, adult mentors, and youth programs) [ 21 , 59 ].

Recognizing the influence of this larger social context on learning and health can help catalyze both individual and community-based solutions. For example, students with chronic illnesses such as asthma, which can affect their school attendance, can be educated about the impact of air quality or housing (e.g., mold, mites) in exacerbating their condition. Students in varied locations and at a range of ages continue, often with the guidance of adults, to take health-related social action. Various local, national, and international examples illustrate high schoolers taking social action related to health issues such as tobacco, gun safety, and climate change [ 18 , 21 , 57 ].

By employing a broad approach to K–12 education (i.e., using combined principles of health education and health literacy), the authors of this manuscript foresee a template for the integration of skills and abilities needed by both school health professionals and children and parents to increase health knowledge for a lifetime of improved health [ 1 , 29 , 31 ].

The right measurements to evaluate success and areas that need improvement must be clearly identified because in all matters related to health education and health literacy, it is vital to document the linkages between informed decisions and actions. Often, individuals are presumed to be making informed decisions when actually broader socio-ecological factors are predominant behavioral influences (e.g., an individual who is overweight but has never learned about food label-ling and lives in a community where there are no safe places to be physically active).

Health Education in Schools

Standardized and broadly adopted strategies for how health education is implemented in schools—and by whom and on what schedule—is a continuing challenge. Although the principles of health literacy are inherently important to any instruction in schools and in community settings, the most effective way to incorporate those principles in existing and differing systems becomes a key to successful health education for children and young people.

The concept of incorporating health education into the formal education system dates to the Renaissance. However, it did not emerge in the United States until several centuries later [ 26 ]. In the early 19th century, Horace Mann advocated for school-based health instruction, while William Alcott also underscored the contributions of health services and the school environment to children’s health and well-being [ 17 ]. Public health pioneer Lemuel Shattuck wrote in 1850 that “every child should be taught early in life, that to preserve his own life and his own health and the lives of others, is one of the most important and abiding duties” [ 43 ]. During this same time, Harvard University and other higher education institutions with teacher preparation programs began including hygiene (health) education in their curricula.

Despite such early historical recognition, in the mid-1960s, the School Health Education Study documented serious disarray in the organization and administration of school health education programs [ 45 ]. A renewed call to action, several decades later, introduced the concepts of comprehensive school health programs and school health education [ 26 ].

From 1998 through 2014, the CDC and other organizations began using the term “coordinated school health programs” to encompass eight components affecting children’s health in schools, including nutrition, health services, and health instruction. Unfortunately, the term was not broadly embraced by the educational sector, and in 2014, CDC and ASCD (formerly the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) unveiled the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) framework [ 36 ]. This framework has ten components, including health education, which aims to ensure that each student is healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged. Among the foundational tenets of the framework is ensuring that every student enters school healthy and, while there, learns about and practices a healthy lifestyle.

At its core, health education is defined as “any combination of planned learning experiences using evidence based practices and/or sound theories that provide the opportunity to acquire knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to adopt and maintain healthy behaviors” [ 3 ]. Included are a variety of physical, social, emotional, and other components focused on reducing health-risk behaviors and promoting healthy decision making. Health education curricula emphasize a skills-based approach to help students practice and advocate for their health needs, as well as the needs of their families and their communities. These skills help children and adolescents find and evaluate health information needed for making informed health decisions and ultimately provide the foundation of how to advocate for their own well-being throughout their lives.

In the last 40 years, many studies have documented the relationship between student health and academic outcomes [ 29 , 40 , 41 ]. Health-related problems can diminish a student’s motivation and ability to learn [ 4 ]. Complications with vision, hearing, asthma, occurrences of teen pregnancy, aggression and violence, lack of physical activity, and low cognitive and emotional ability can reduce academic success [ 4 ].

To date, there have been no long-term sequential studies of the impact of K–12 health education curricula on health literacy or health outcomes. However, research shows that students who participate in health education curricula in combination with other interventions as part of the coordinated school health model (i.e., physical activity, improved nutrition, and/or family engagement) have reduced rates of obesity and/or improved health-promoting behaviors [ 25 , 30 , 34 ]. In addition, school health education has been shown to prevent tobacco and alcohol use and prevent dating aggression and violence. Teaching social and emotional skills improves academic behaviors of students, increases motivation to do well in school, enhances performance on achievement tests and grades, and improves high school graduation rates.

As with other content areas, it is up to the state and/or local government to determine what should be taught, under the 10th Amendment to the US Constitution [ 48 ]. However, both public and private organizations have produced seminal documents to help guide states and local governments in selecting health education curricula. First published in 1995 and updated in 2004, the National Health Education Standards (NHES) framework comprises eight health education foundations for what students in kindergarten through 12th grade should know and be able to do to promote personal, family, and community health (see Table 1 ) [ 12 ]. The NHES framework serves as a reference for school administrators, teachers, and others addressing health literacy in developing or selecting curricula, allotting instructional resources, and assessing student achievement and progress. The NHES framework contains written expectations for what students should know and be able to do by grades 2, 5, 8, and 12 to promote personal, family, and community health.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. National Health Education Standards. Available at: National Health Education Standards Website. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/standards/index.htm (accessed June 19, 2020).

The Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH) model, which was first developed in the late 1980s with funds by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, serves to implement the NHES framework and was the largest school-based health promotion study ever conducted in the United States. CATCH has 25 years of continuous research and development of its programs [ 24 ] and aligns with the WSCC framework. Individualized programs like the CATCH model develop programming based on the NHES framework at the local level, so that local control still exists, but the mix and depth of topics can vary based on need and composition of the community.

Based on reviews of effective programs and curricula and experts in the field of health education, CDC recommends that today’s state-of-the-art health education curricula emphasize four core elements: “Teaching functional health information (essential knowledge); shaping personal values and beliefs that support healthy behaviors; shaping group norms that value a healthy lifestyle; and developing the essential health skills necessary to adopt, practice, and maintain health enhancing behavior” [ 13 ]. In addition to the 15 characteristics presented in Box 1 , the CDC website has more detailed explanations and examples of how the statements could be put into practice in the classroom. For example, a curriculum that “builds personal competence, social competence, and self-efficacy by addressing skills” would be expected to guide students through a series of developmental steps that discuss the importance of the skill, its relevance, and relationship to other learned skills; present steps for developing the skill; model the skill; practice and rehearse the skill using real-life scenarios; and provide feedback and reinforcement.

Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum

- 1. Focuses on clear health goals and related behavioral outcomes.

- 2. Is research-based and theory-driven.

- 3. Addresses individual values, attitudes, and beliefs.

- 4. Addresses individual and group norms that support health-enhancing behaviors.

- 5. Focuses on reinforcing protective factors and increasing perceptions of personal risk and harmfulness of engaging in specific unhealthy practices and behaviors.

- 6. Addresses social pressures and influences.

- 7. Builds personal competence, social competence, and self-efficacy by addressing skills.

- 8. Provides functional health knowledge that is basic, accurate, and directly contributes to health-promoting decisions and behaviors.

- 9. Uses strategies designed to personalize information and engage students.

- 10. Provides age-appropriate and developmentally appropriate information, learning strategies, teaching methods, and materials.

- 11. Incorporates learning strategies, teaching methods, and materials that are culturally inclusive.

- 12. Provides adequate time for instruction and learning.

- 13. Provides opportunities to reinforce skills and positive health behaviors.

- 14. Provides opportunities to make positive connections with influential others.

- 15. Includes teacher information and plans for professional development and training that enhance effectiveness of instruction and student learning.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/characteristics/index.htm (accessed June 19, 2020.)

In addition, CDC has developed a Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool [ 14 ] to help schools conduct an analysis of health education curricula based on the NHES framework and the Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum.

Despite CDC’s extensive efforts during the past 40 years to help schools implement effective school health education and other components of the broader school health program, the integration of health education into schools has continued to fall short in most US states and cities. According to the CDC’s 2016 School Health Profiles report, the percentage of schools that required any health education instruction for students in any of grades 6 through 12 declined. For example, 8 in 10 US school districts only required teaching about violence prevention in elementary schools and violence prevention plus tobacco use prevention in middle schools, while instruction in only seven health topics was required in most high schools [ 6 ].

Although 8 of every 10 districts required schools to follow either national, state, or district health education standards, just over a third assessed attainment of health standards at the elementary level while only half did so at the middle and high school levels [ 6 ]. No Child Left Behind legislation, enacted in 2002, emphasized testing of core subjects, such as reading, science, and math, which resulted in marginalization of other subjects, including health education [ 22 , 31 ]. Academic subjects that are not considered “core” are at risk of being eliminated as public school principals and administrators struggle to meet adequate yearly progress for core subjects, now required to maintain federal funding.