Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

This topic will review the development, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of portal hypertension in adults. The causes of portal hypertension and the treatment of its complications are discussed in detail elsewhere:

● (See "Cirrhosis in adults: Etiologies, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis" .)

● (See "Noncirrhotic portal hypertension" .)

● (See "Cirrhosis in adults: Overview of complications, general management, and prognosis", section on 'Preventing complications' .)

Advertisement

Systemic Disease and Portal Hypertension

- Published: 04 March 2024

- Volume 23 , pages 162–173, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Talal Khurshid Bhatti 1 &

- Paul Y. Kwo 2

60 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

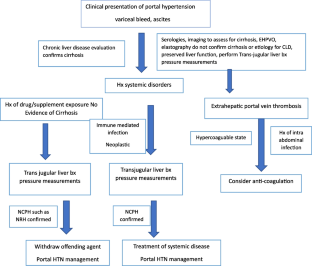

The development of portal hypertension is typically a consequence of liver cirrhosis due mainly to primary liver disorders, whereas non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) can be a complication of systemic, primarily extrahepatic diseases. Our purpose was to review the various systemic disorders leading to portal hypertension and provide a pathway for diagnosis and management.

Recent Findings

Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension is a heterogeneous group of liver disorders primarily of vascular origin that may manifest as portal hypertension. The diagnosis of NCPH in the setting of systemic diseases is challenging and a liver biopsy may be required to confirm the diagnosis. Etiologies include those of vascular origin, autoimmune disorders, drug exposures, and infections.

Complications of portal hypertension in the setting of systemic diseases are similar to patients having cirrhosis and should be addressed similarly while addressing the underlying systemic disorder if possible

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Non-Cirrhotic Portal Hypertension: an Overview

Idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: a review.

Non-cirrhotic Portal Fibrosis

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• of major importance.

Schouten JN, Garcia-Pagan JC, Valla DC, Janssen HL. Idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2011;54(3):1071–81.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gracia-Sancho J, Marrone G, Fernández-Iglesias A. Hepatic microcirculation and mechanisms of portal hypertension. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(4):221–34.

Intagliata NM, Caldwell SH, Tripodi A. Diagnosis, development, and treatment of portal vein thrombosis in patients with and without cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6).

Simonetto DA, Liu M, Kamath PS. Portal hypertension and related complications :diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(4):714–26.

Khanna R, Sarin SK. Idiopathic portal hypertension and extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(Suppl 1):148–67.

Da BL, Surana P, Kapuria D, Vittal A, Levy E, Kleiner DE, Koh C, Heller T. Portal pressure in noncirrhotic portal hypertension: to measure or not to measure. Hepatology. 2019;70(6):2228–30. Of major importance: This study reported in a large cohort of individuals with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension that portal pressures as assessed by HVPH are not typically elevated and also do not correlate with complications of portal hypertension. They suggest that at obtaining a liver biopsy percutaneously may be an appropriate strategy in this population .

Eapen CE, Nightingale P, Hubscher SG, et al. Non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension: associated gut diseases and prognostic factors. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(1):227–35.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sharma P, Agarwal R, Dhawan S, Bansal N, Singla V, Kumar A, Arora A. Transient elastography (fibroscan) in patients with non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7(3):230–4.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sarin SK, Khanna R. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:451–76.

Verheij J, Schouten JN, Komuta M, et al. Histological features in western patients with idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Histopathology. 2013;62(7):1083–91.

Lee H, Rehman AU, Fiel MI. Idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension: an appraisal. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50(1):17–25.

Nayak NC, Jain D, Saigal S, Soin AS. Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis: one disease with many names? An analysis from morphological study of native explant livers with end stage chronic liver disease. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(7):592–8.

Hillaire S, Bonte E, Denninger MH, et al. Idiopathic non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension in the west: a re-evaluation in 28 patients. Gut. 2002;51(2):275–80.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

De Gottardi A, Rautou PE, Schouten J, Rubbia-Brandt L, Leebeek F, Trebicka J, Murad SD, Vilgrain V, Hernandez-Gea V, Nery F, Plessier A. Porto-sinusoidal vascular disease: proposal and description of a novel entity. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(5):399–411.

Cerda Reyes E, González-Navarro EA, Magaz M, Muñoz-Sánchez G, Diaz A, Silva-Junior G, et al. Autoimmune biomarkers in porto-sinusoidal vascular disease: potential role in its diagnosis and pathophysiology. Liver Int. 2021;41(9):2171–8.

Sarin SK, Kapoor D. Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis: current concepts and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:526–34.

Madhu K, Avinash B, Ramakrishna B, Eapen CE, Shyamkumar NK, Zachariah U, et al. Idiopathic non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension: common cause of cryptogenic intrahepatic portal hypertension in a Southern Indian tertiary hospital. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:83–7.

Okudaira M, Ohbu M, Okuda K. Idiopathic portal hypertension and its pathology. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22(1):59–72.

Chang P-E, Miquel R, Blanco J-L, Laguno M, Bruguera M, Abraldes JG, et al. Idiopathic portal hypertension in patients with HIV infection treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1707–14.

Schouten JN, Van der Ende ME, Koëter T, et al. Risk factors and outcome of HIV associated idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(9):875–85.

Mallet V, Blanchard P, Verkarre V, Vallet-Pichard A, Fontaine H, Lascoux-Combe C, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is a new cause of chronic liver disease in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2007;21:187–92.

Okuda K. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension versus idiopathic portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S204–13.

PubMed Google Scholar

Salzer U, Warnatz K, Peter HH. Common variable immunodeficiency: an update. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:223.

Xiao X, Miao Q, Chang C, Gershwin ME, Ma X. Common variable immunodeficiency and autoimmunity—an inconvenient truth. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:858–64.

Bonilla FA, Barlan I, Chapel H, Costa-Carvalho BT, Cunningham-Rundles C, de la Morena MT, Espinosa-Rosales FJ, et al. International consensus document (ICON): common variable immunodeficiency disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:38–59.

Resnick ES, Moshier EL, Godbold JH, Cunningham-Rundles C. Morbidity and mortality in common variable immune deficiency over 4 decades. Blood. 2012;119:1650–7.

Gathmann B, Mahlaoui N, Gerard L, Oksenhendler E, Warnatz K, Schulze I, Kindle G, et al. Clinical picture and treatment of 2212 patients with common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:116–26.

Cunningham-Rundles C, Maglione PJ. Common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1425-1426.e1423.

Fuss IJ, Friend J, Yang Z, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:748–58.

Inagaki H, Nonami T, Kawagoe T, et al. Idiopathic portal hypertension associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(3):235–9.

van Hoek B. The spectrum of liver disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Neth J Med. 1996;48(6):244–53.

Matsumoto T, Yoshimine T, Shimouchi K, et al. The liver in systemic lupus erythematosus: pathologic analysis of 52 cases and review of Japanese Autopsy Registry Da-ta. Hum Pathology. 1992;23(10):1151–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Efe C, Purnak T, Ozaslan E, et al. Autoimmune liver disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus retrospective analysis of 147 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(6):732–7.

Kraaijvanger R, Janssen Bonás M, Vorselaars AD, Veltkamp M. Biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of sarcoidosis: current use and future prospects. Front Immunol. 2020;14(11):1443.

Article Google Scholar

Kennedy PTF, Zakaria N, Modawi SB, et al. Natural history of hepatic sarcoidosis and its response to treatment. European J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:721–6.

Bodh V, Chawla YK. Noncirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;3:129–32.

Koukounari A, Donnelly CA, Sacko M, Keita AD, Landouré A, Dembelé R, et al. The impact of single versus mixed schistosome species infections on liver, spleen and bladder morbidity within Malian children pre- and post-praziquantel treatment. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:227.

Mazigo HD, Nuwaha F, Wilson S, Kinung’hi SM, Morona D, Waihenya R, et al. Epidemiology and interactions of human immunodeficiency virus - 1 and Schistosoma Mansoni+ in sub-Saharan Africa. Infect Dis Poverty. 2013;2(1):2.

Pereira TA, Xie G, Choi SS, Syn WK, Voieta I, Lu J, et al. Macrophage-derived hedgehog ligands promotes fibrogenic and angiogenic responses in human Schistosomiasis mansoni. Liver Int. 2013;33:149–61.

Mallet VO, Varthaman A, Lasne D, Viard JP, Gouya H, Borgel D, Lacroix-Desmazes S. et al. Acquired protein S deficiency leads to obliterative portal venopathy and to compensatory nodular regenerative hyperplasia in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 2009;23(12):1511–1518.

Lafeuillade A, Alessi MC, Poizot-Martin I, Dhiver C, Quilichini R, Aubert L, et al. Protein S deficiency and HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1220.

Siramolpiwat S, Seijo S, Miquel R, et al. Idiopathic portal hypertension: natural history and long-term outcome. Hepatology. 2014;59(6):2276–85.

Bora D. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in India. Natl Med J India. 1999;12:62–8.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bryceson A. Visceral leishmaniasis in India. Lancet. 2000;356:1933.

Singh S, Sivakumar R. Recent advances in the diagnosis of leishmaniasis. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:55–60.

Datta DV, Saha S, Grover SL, Samant A, Singh R, Chakravarti N, et al. Portal hypertension in kalaazar. Gut. 1972;13:147–52.

Agrawal P, Wali JP, Chopra P. Liver in kala-azar. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1990;9:135–6.

Google Scholar

Guevara P, Ramirez JL, Rojas L, Scorza JV, Gonzales N, Anez N. Leishmania braziliensis in blood 30 years after cure. Lancet. 1993;341:1341.

Rogler G. Gastrointestinal and liver adverse effects of drugs used for treating IBD. Best Practice Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(2):157–65.

Wanless IR, Godwin TA, Allen F, Feder A. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver in hematologic disorders: a possible response to obliterative portal venopathy. A morphometric study of nine cases with an hypothesis on the pathogenesis. Medicine. 1980;59:367–79.

DeLeve LD, Wang X, Kuhlenkamp JF, et al. Toxicity of azathioprine and monocrotaline in murine sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatocytes: the role of glutathione and relevance to hepatic venoocclusive disease. Hepatology. 1996;23:589–99.

De Vito C, Tyraskis A, Davenport M, Thompson R, Heaton N, Quaglia A. Histopathology of livers in patients with congenital portosystemic shunts (Abernethy malformation): a case series of 22 patients. Virchows Arch. 2018;474(1):47–57.

Baiges A, Turon F, Simón-Talero M, Tasayco S, Bueno J, Zekrini K, et al. Congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts (Abernethy malformation): an international observational study. Hepatology. 2019;71(2):658–69.

Majumdar A, Delatycki MB, Crowley P, et al. with m. J Hepatol. 2015;63(2):525–7.

Besmond C, Valla D, Hubert L, et al. Mutations in the novel gene FOPV are associated with familial autosomal dominant and non-familial obliterative portal venopathy. Liver Int. 2018;38(2):358–64.

Dumortier J, Boillot O, Chevallier M, et al. Familial occurrence of nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver: a report on three families. Gut. 1999;45(2):289–94.

Witters P, Libbrecht L, Roskams T, Boeck KD, Dupont L, Proesmans M, et al. Noncirrhotic pre-sinusoidal portal hypertension is common in cystic fibrosis-associated liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:1064–5.

Mayer JE, Schiano TD, Fiel MI, Hoffman R, Mascarenhas JO. An association of myeloproliferative neoplasms and obliterative portal venopathy. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(7):1638–41.

Valla DC, Cazals-Hatem D. Vascular liver diseases on the clinical side: definitions and diagnosis, new concepts. Virchows Arch. 2018;473(1):3–13.

Schouten JNL, Nevens F, Hansen B, Laleman W, den Born M, Komuta M, et al. Idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension is associated with poor survival: results of a long-term cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1424–33.

Cazals-Hatem D, Hillaire S, Rudler M, Plessier A, Paradis V, Condat B, et al. Obliterative portal venopathy: portal hypertension is not always present at diagnosis. J Hepatol. 2011;54:455–61.

Carreras LO, Defreyn G, Machin SJ, Vermylen J, Deman R, Spitz B, et al. Arterial thrombosis, intrauterine death and “lupus” antiocoagulant: detection of immunoglobulin interfering with prostacyclin formation. Lancet. 1981;1:244–6.

O’Leary JG, Cai J, Freeman R, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for chronic antibody mediated rejection in liver allografts. Am J Transpl. 2016;16(2):603–14.

Etzion O, Koh C, Heller T. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension: An overview. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2015;6(3):72–74.

Glatard AS, Hillaire S, d’Assignies G, Cazals-Hatem D, Plessier A, Valla DC, Vilgrain V. Obliterative portal venopathy: findings at CT imaging. Radiology. 2012;263(3):741–50.

Arora A, Sarin SK. Multimodality imaging of obliterative portal venopathy: what every radiologist should know. Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1046):20140653.

Elkrief L, Lazareth M, Chevret S, Paradis V, Magaz M, Blaise L, Rubbia-Brandt L, et al. Liver stiffness by transient elastography to detect porto-sinusoidal vascular liver disease with portal hypertension. Hepatology . 2020.

Sarin SK, Kumar A, Chawla YK, Baijal SS, Dhiman RK, Jafri W, et al. Noncirrhotic portal fibrosis/idiopathic portal hypertension: APASL recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Hepatol Int. 2007.

Dhiman RK, Chawla Y, Vasishta RK, Kakkar N, Dilawari JB, Trehan MS, et al. Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (idiopathic portal hypertension): experience with 151 patients and a review of the literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:6–16.

Okuda K, Kono K, Ohnishi K, Kimura K, Omata M, Koen H, et al. Clinical study of eighty-six cases of idiopathic portal hypertension and comparison with cirrhosis with splenomegaly. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:600–10.

Rangari M, Gupta R, Jain M, Malhotra V, Sarin SK. Hepatic dysfunction in patients with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Liver Int. 2003;23:434–9.

Bissonnette J, Garcia-Pagán JC, Albillos A, Turon F, Ferreira C, Tellez L, et al. Role of the trans-jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of severe complications of portal hypertension in idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension: liver failure/cirrhosis/portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):224–31.

Lattanzi B, Gioia S, Di Cola S, et al. Prevalence and impact of sarcopenia in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Liver Int. 2019;39(10):1937–42. Of major importance: This report notes that the prevalence of sarcopenia in a cohort of patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension as assessed by skeletal muscle index (SMI) was similar to those with cirrhosis, decompensated and portal vein thrombosis suggesting that the presence of portal hypertension contributes sarcopenia. In addition, sarcopenia was also associated with a higher rate of variceal bleeding requiring TIPS placement .

Dhiman RK, Behera A, Chawla YK, Dilawari JB, Suri S. Portal hypertensive biliopathy. Gut. 2007;56:1001–8.

Dilawari JB, Chawla YK. Extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Gut. 1988;29:L554-555.

Maruyama H, Okugawa H, Kobayashi S, Yoshizumi H, Takahashi M, Ishibashi H, et al. Non-invasive porto-graphy: a microbubble-induced three-dimensional sonogram for discriminating idiopathic portal hypertension from cirrhosis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1013):587–95.

Lee H, Ainechi S, Singh M, Ells PF, Sheehan CE, Lin J. Histological spectrum of idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension in liver biopsies from dialysis patients. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23(6):439–46.

Bioulac-Sage P, Le Bail B, Bernard PH, Balabaud C. Hepatoportal sclerosis. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15(4):329–39.

Jharap B, van Asseldonk DP, de Boer NKH, et al. Diagnosing nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver is thwarted by low interobserver agreement. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120299.

de Franchis R; On behalf of the Baveno V Faculty. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–768.

Sarin SK, Gupta N, Jha SK, Agrawal A, Mishra SR, Sharma BC, et al. Equal efficacy of endoscopic variceal ligation and propranolol in preventing variceal bleeding in patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1238–45.

Sarin SK, Sollano JD, Chawla YK, Amarapurkar D, Hamid S, Hashizume M, et al. Members of the APASL working party on portal hypertension. Consensus on extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction. Liver Int. 2006;26:512–9.

Romano M, Giojelli A, Capuano G, Pomponi D, Salvatore M. Partial splenic embolization in patients with idiopathic portal hypertension. Eur J Radiol. 2004;49:268–73.

Hirota S, Ichikawa S, Matsumoto S, Motohara T, Fukuda T, Yoshikawa T. Interventional radiologic treatment for idiopathic portal hypertension. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1999;22:311–4.

Krasinskas AM, Eghtesad B, Kamath PS, Demetris AJ, Abraham SC. Liver transplantation for severe intrahepatic noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:627–34.

Dumortier J, Bizollon T, Scoazec JY, Chevallier M, Bancel B, Berger F, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation for idiopathic portal hypertension: indications and outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:417–22.

Loinaz C, Colina F, Musella M, Lopez-Rios F, Gomez R, Jimenez C, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation in 4 patients with portal hypertension and non-cirrhotic nodular liver. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 1998.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Medical University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Talal Khurshid Bhatti

Stanford University School of Medicine, 430 Broadway, Pavilion C, 3Rd Floor, Redwood City, Palo Alto, CA, USA

Paul Y. Kwo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PK made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. TK made substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paul Y. Kwo .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of Interest

Human and animal rights and informed consent.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Bhatti, T.K., Kwo, P.Y. Systemic Disease and Portal Hypertension. Curr Hepatology Rep 23 , 162–173 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-024-00645-8

Download citation

Accepted : 15 January 2024

Published : 04 March 2024

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-024-00645-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension

- Nodular regenerative hyperplasia

- Extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis

- Hepatoportal sclerosis

- Idiopathic portal hypertension

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Current Issue

- Supplements

Gastroenterology & Hepatology

January 2021 - volume 17, issue 1, overview of current management of portal hypertension, guadalupe garcia-tsao, md.

Professor of Medicine Yale University School of Medicine New Haven, Connecticut Chief, Digestive Diseases Section VA-CT Healthcare System West Haven, Connecticut

G&H Currently, what are the most common causes of portal hypertension?

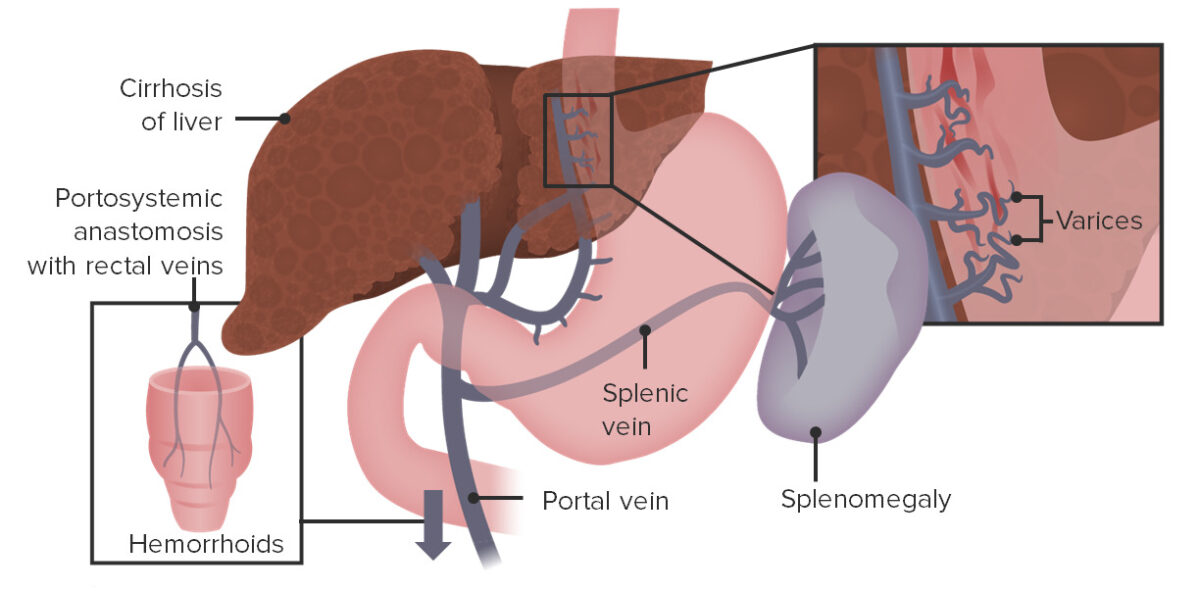

GG-T Portal hypertension is high pressure in the portal vein, which is the vein that carries blood to the liver. By far, the most common cause of portal hypertension is cirrhosis. Normally, the liver is a soft organ, and blood flows through it very easily. With cirrhosis, the liver becomes hard and blood cannot flow easily, so it backs up and pressure increases in the portal vein.

The second most common cause is portal vein thrombosis, when there is a clot in a part of the portal vein before the liver. This results in a prehepatic type of portal hypertension. The liver is healthy, but the clot is an obstruction, and pressure increases in the portion of the portal vein that is proximal to the clot. In cirrhosis, the obstruction is the liver itself.

G&H How do patients with portal hypertension typically present?

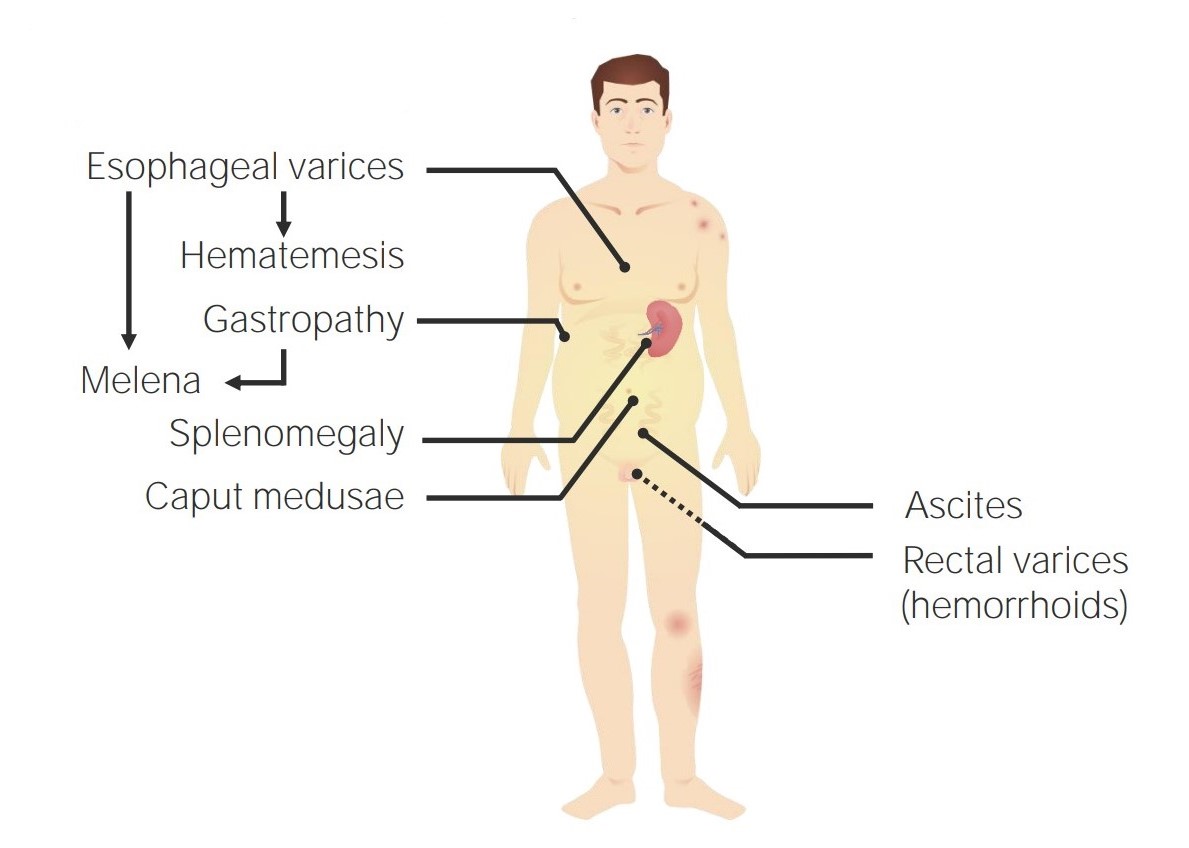

GG-T A typical presentation involves varices or variceal bleeding. Vessels in the esophagus, known as varices, normally carry blood into the portal system, but with portal hypertension, these vessels enlarge and carry blood away from the portal vein. These vessels may rupture, causing the patient to vomit blood. A more common, but more ominous, presentation of cirrhosis with portal hypertension is the development of fluid in the abdomen, referred to as ascites. Once the patient presents with variceal bleeding or ascites, the patient’s cirrhosis has decompensated.

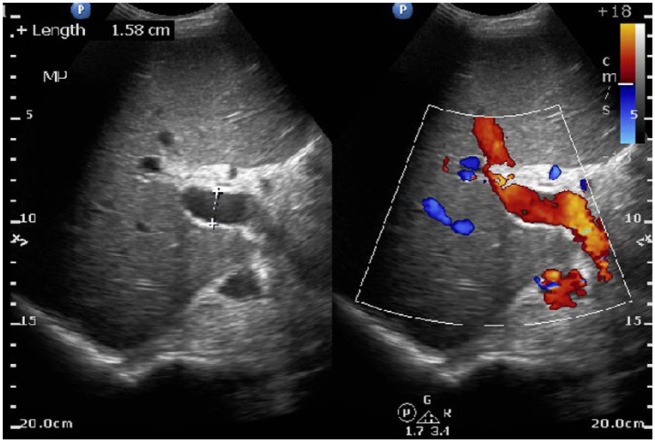

G&H How is portal hypertension currently measured?

GG-T All of the research to date has measured portal pressure by determining the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), although this approach is invasive. A needle is placed in the jugular vein, and pressure is measured in the liver sinusoids. This indirect measure is used because accessing the portal vein directly is very difficult.

G&H What is the current understanding of clinically significant portal hypertension?

GG-T Clinically significant portal hypertension is defined as an HVPG equal to or higher than 10 mm Hg, mild portal hypertension as 6 to less than 10 mm Hg, and normal pressure as 3 to 5 mm Hg. Patients with mild portal hypertension are unlikely to decompensate, whereas patients with clinically significant portal hypertension are more likely to decompensate (ie, they develop ascites; bleed from varices; or develop encephalopathy, which is when ammonia is not cleared by the liver because it escapes through collateral veins, causing the patient to become confused).

G&H Have there been any recent changes in the treatment paradigm of patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension?

GG-T There may now be a new treatment approach. In the past, when cirrhosis was diagnosed, the next step was to perform an endoscopy to determine whether the patient had varices. Patients with large varices were treated via banding of the varices or with nonselective beta blockers because the varices were likely to bleed. The main goal was to prevent variceal hemorrhage, and no measures were used to prevent the other 2 decompensating events, ascites or encephalopathy. A seminal randomized, placebo-controlled study was published last year, the PREDESCI trial, which showed that nonselective beta blockers prevent decompensation (mainly ascites) in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension. This concept will likely lead to a paradigm shift. Now, when a diagnosis of cirrhosis is made, the next step is to determine whether the patient has clinically significant portal hypertension and, if so, to start nonselective beta blockers to prevent decompensation.

G&H How effective are nonselective beta blockers in patients with portal hypertension?

GG-T These agents are very effective, although they do not decrease portal pressure in all patients. In the PREDESCI trial, investigators used the beta blockers propranolol and carvedilol and adjusted their doses based on heart rate and blood pressure. Carvedilol is a much more potent nonselective beta blocker because it has additional alpha-adrenergic blocking effects. In the trial, one-third of patients received carvedilol, while two-thirds received propranolol. Patients who received carvedilol had a greater portal pressure–reducing effect and had better outcomes.

G&H What have other studies reported thus far regarding which nonselective beta blocker is most effective in this setting?

GG-T Several investigational studies have shown that carvedilol is more effective than propranolol at lowering HVPG. However, carvedilol lowers the mean arterial pressure much more than propranolol. Thus, if an individual taking carvedilol has low blood pressure, as is often the case with a decompensated patient, he or she is more likely to become hypotensive. This is the main concern with using carvedilol. On the other hand, there is no issue with carvedilol use in compensated patients, as their blood pressure is typically normal.

G&H What is the current role of portosystemic shunting procedures in patients with portal hypertension?

GG-T It is important to emphasize that portosystemic shunts such as the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure should never be used in compensated patients, as this will divert blood flow away from the liver and could actually lead to decompensation in a patient who is otherwise doing well. In contrast, decompensated patients may need to urgently decompress portal pressure because they may be bleeding massively from varices. In these decompensated patients, the TIPS procedure could be life-saving.

G&H When should the TIPS procedure be used in decompensated patients?

GG-T In general, the TIPS procedure is second-line therapy for variceal hemorrhage or ascites in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. That is, it is performed when bleeding or ascites are not responding to standard of care. Having said that, doctors probably have been waiting too long to use the TIPS procedure. It should not be used too late, but it should also not be used too early, when it may divert blood flow away from the liver. The ideal timing is still being debated. I think doctors are starting to consider the TIPS procedure earlier on now. I would not wait for a patient to bleed for the third time; once a patient bleeds a second time, I would turn to the TIPS procedure. The current indications and timing of the TIPS procedure were recently discussed at an expert consensus conference by the ALTA (Advancing Liver Therapeutic Approaches) Consortium and are expected to be published soon.

G&H Does there appear to be a role for statins in the management of portal hypertension?

GG-T Statins can dilate the vessels that are inside the liver and that are constricted. There are experimental studies and proof-of-concept studies in patients with cirrhosis showing that statins lower portal pressure while improving flow to the liver. However, there is a lack of randomized clinical trials that show that statins can prevent decompensation. There is currently an ongoing multicenter, randomized, controlled Veterans Affairs study investigating the use of statins in compensated cirrhosis with the objective of preventing decompensation. The National Institutes of Health has recently announced a research project cooperative agreement looking at trials on statins for this use.

G&H What other research is being conducted in this field?

GG-T As previously mentioned, measurement of HVPG is invasive. Many investigations are looking at noninvasive methods to determine who has or does not have clinically significant portal hypertension. For example, some research is examining noninvasive assessment of liver stiffness because the stiffer the liver, the higher the portal pressure. Another method being studied to determine whether a patient has clinically significant portal hypertension is measuring the platelet count in combination with liver stiffness measurement.

In addition to looking for other ways of reducing portal pressure, there has also been much discussion on the preemptive use of the TIPS procedure. This involves placement of the TIPS procedure in patients admitted with variceal bleeding who respond to standard of care but are at a high risk of rebleeding during the admission. In these patients, rather than wait to use the TIPS procedure when the patient rebleeds, it would be used preemptively. There is controversy over which patients are candidates for doing this, so further research is needed.

Finally, we are looking forward to the upcoming Baveno VII Consensus Conference, which will take place in less than a year. New guidelines will be developed for portal hypertension that will include the use of nonselective beta blockers in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension (without having to perform an endoscopy) and the indications for preemptive use of the TIPS procedure.

Disclosures

Dr Garcia-Tsao has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Suggested Reading

Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology . 2017;65(1):310-335.

Mandorfer M, Hernández-Gea V, García-Pagán JC, Reiberger T. Noninvasive diagnostics for portal hypertension: a comprehensive review. Semin Liver Dis . 2020;40(3):240-255.

Turco L, Garcia-Tsao G. Portal hypertension: pathogenesis and diagnosis. Clin Liver Dis . 2019;23(4):573-587.

Villanueva C, Albillos A, Genescà J, et al. β blockers to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension (PREDESCI): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet . 2019;393(10181):1597-1608.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Hepatol

- v.2012; 2012

Clinical Manifestations of Portal Hypertension

Said a. al-busafi.

1 Department of Medicine, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, P.O. Box 35, 123 Muscat, Oman

2 Department of Gastroenterology, Royal Victoria Hospital, McGill University Health Center, Montreal, QC, Canada H3A 1A1

Julia McNabb-Baltar

Amanda farag.

3 Department of Medicine, Royal Victoria Hospital, McGill University Health Center, Montreal, QC, Canada H3A 1A1

Nir Hilzenrat

4 Department of Gastroenterology, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

The portal hypertension is responsible for many of the manifestations of liver cirrhosis. Some of these complications are the direct consequences of portal hypertension, such as gastrointestinal bleeding from ruptured gastroesophageal varices and from portal hypertensive gastropathy and colopathy, ascites and hepatorenal syndrome, and hypersplenism. In other complications, portal hypertension plays a key role, although it is not the only pathophysiological factor in their development. These include spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepatic encephalopathy, cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and portopulmonary hypertension.

1. Introduction

Portal hypertension (PH) is a common clinical syndrome defined as the elevation of hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) above 5 mm Hg. PH is caused by a combination of two simultaneous occurring hemodynamic processes: (1) increased intrahepatic resistance to passage of blood flow through the liver due to cirrhosis and (2) increased splanchnic blood flow secondary to vasodilatation within the splanchnic vascular bed. PH can be due to many different causes at prehepatic, intrahepatic, and posthepatic sites ( Table 1 ). Cirrhosis of the liver accounts for approximately 90% of cases of PH in Western countries.

Causes of portal hypertension (PH).

The importance of PH is defined by the frequency and severity of its complications including variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome, which represent the leading causes of death and of liver transplantation in patients with cirrhosis. PH is considered to be clinically significant when HVPG exceeds 10 to 12 mm Hg, since this is the threshold for the clinical complications of PH to appear [ 1 ]. Proper diagnosis and management of these complications are vital to improving quality of life and patients' survival. This paper will review the multisystemic manifestations of PH in cirrhosis.

2. Gastrointestinal Manifestations

2.1. gastroesophageal (ge) varices.

Approximately 5–15% of cirrhotics per year develop varices, and it is estimated that the majority of patients with cirrhosis will develop GE varices over their lifetime. The presence of GE varices correlates with the severity of liver disease; while only 40% of child A patients have varices, they are present in 85% of child C patients ( Table 2 ) [ 2 ].

Child-Pugh-Turcotte (CPT) Classification of the Severity of Cirrhosis.

Collaterals usually exist between the portal venous system and the systemic veins. The resistance in the portal vessels is normally lower than in the collateral circulation, and so blood flows from the systemic bed into the portal bed. However, when PH develops, the portal pressure is higher than systemic venous pressure, and this leads to reversal of flow in these collaterals. In addition, the collateral circulatory bed also develops through angiogenesis and the development of new blood vessels in an attempt to decompress the portal circulation [ 3 ]. The areas where major collaterals occur between the portal and systemic venous system are shown in Table 3 . Unfortunately these collaterals are insufficient to decompress the PH, leading to complications including variceal bleeding.

Location and blood vessels of collaterals between the portal and systemic venous circulations.

GE area is the main site of formation of varices [ 4 ]. Esophageal varices (EV) form when the HVPG exceeds 10 mm Hg [ 5 ]. In the lower 2 to 3 cm of the esophagus, the varices in the submucosa are very superficial and thus have thinner wall. In addition, these varices do not communicate with the periesophageal veins and therefore cannot easily be decompressed. These are the reasons why EV bleeds only at this site.

Over the last decade, most practice guidelines recommend to screen known cirrhotics with endoscopy to look for GE varices. Varices should be suspected in all patients with stigmata of chronic liver disease such as spider nevi, jaundice, palmar erythema, splenomegaly, ascites, encephalopathy, and caput medusae. EV are graded as small (<5 mm) and large (>5 mm), where 5 mm is roughly the size of an open biopsy forceps [ 6 ].

The rate of progression of small EV to large is 8% per year [ 2 ]. Decompensated cirrhosis (child B or C), presence of red wale marks (defined as longitudinal dilated venules resembling whip marks on the variceal surface), and alcoholic cirrhosis at the time of baseline endoscopy are the main factors associated with the progression from small to large EV [ 2 ]. EV bleeding occurs at a yearly rate of 5%–15% [ 7 ]. The predictors of first bleeding include the size of varices, severity of cirrhosis (Child B or C), variceal pressure (>12 mm Hg), and the endoscopic presence of red wale marks [ 7 , 8 ]. Although EV bleeding stops spontaneously in up to 40% of patients, and despite improvements in therapy over the last decade, the 6 weeks mortality rate is still ≥20% [ 9 ].

Gastroesophageal varices (GOV) are an extension of EV and are categorized based on Sarin's classification into 2 types ( Figure 1 ). The most common are Type 1 (GOV1) varices, which extend along the lesser curvature. Type 2 GOV (GOV2) are those that extend along the fundus. They are longer and more tortuous than GOV1. Isolated gastric varices (IGV) occur in the absence of EV and are also classified into 2 types. Type 1 (IGV1) are located in the fundus and tend to be tortuous and complex, and type 2 (IVG2) are located in the body, antrum, or around the pylorus. When IGV1 is present, one must exclude splenic vein thrombosis. GV are less common than EV and are present in 5%–30% of patients with PH with a reported incidence of bleeding of about 25% in 2 years, with a higher bleeding incidence for fundal varices [ 10 ]. Predictors of GV bleeding include the size of fundal varices (large (>10 mm) > medium (5–10 mm) > small (<5 mm)), severity of cirrhosis (child class C>B>A), and endoscopic presence of variceal red spots (defined as localized reddish mucosal area or spots on the mucosal surface of a varix) [ 11 ].

Sarin classification of gastric varices.

2.2. Ectopic Varices (EcV)

EcV are best defined as large portosystemic venous collaterals occurring anywhere in the abdomen except for the GE region [ 12 ]. They are an unusual cause of GI bleeding, but account for up to 5% of all variceal bleeding [ 13 ]. Compared to GE varices, EcV are difficult to locate, occur at distal sites, and when identified, the choice of therapy is unclear, therefore representing a clinical challenge [ 12 ]. Furthermore, bleeding EcV may be associated with poor prognosis, with one study quoting mortality reaching 40% [ 14 ]. Different areas of EcV are the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon, rectum, peristomal, biliary tree, gallbladder, peritoneum, umbilicus, bare area of the liver, ovary, vagina, and testis [ 15 , 16 ].

The prevalence of EcV varies in the literature and seems to be related to the etiology of the PH and the diagnostic modalities used [ 17 ]. In patients with PH due to cirrhosis, duodenal varices are seen in 40% of patients undergoing angiography [ 18 ]. Results of a survey for EcV conducted over 5 years in Japan identified 57 cases of duodenal varices; they were located in the duodenal bulb in 3.5%, the descending part in 82.5%, and the transverse part in 14.0% [ 15 ].

In contrast to duodenal varices, it appears that most cases of varices in other portions of the small bowel and colonic varices are seen in patients with cirrhosis who have previously undergone abdominal surgery [ 12 ]. Using advanced endoscopic technologies, particularly capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy, the prevalence of small bowel varices is estimated to be approximately 69% in patients with PH [ 19 ]. The prevalence of colonic varices and rectal varices has been found to be 34% to 46% [ 20 , 21 ] and 10% to 40% [ 22 ], respectively, in patients with cirrhosis undergoing colonoscopy. It is important to differentiate rectal varices from hemorrhoids; rectal varices extend more than 4 cm above the anal verge, are dark blue in color, collapse with digital pressure, and do not prolapse into the proctoscope on examination, whereas hemorrhoids do not extend proximal to the dentate line, are purple in color, do not collapse with digital pressure, and often prolapse into the proctoscope [ 22 , 23 ]. Stomal varices are a particularly common cause of EcV and can occur in patients with cirrhosis secondary to primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) [ 12 ].

In the west, because the prevalence of noncirrhotic PH is low, most bleeding EcV is usually associated with cirrhotic PH (6,8). Although EcV can occur at several sites, bleeding EcV are most commonly found in the duodenum and at sites of previous bowel surgery including stomas.

In a review of 169 cases of bleeding EcV, 17% occurred in the duodenum, 17% in the jejunum or ileum, 14% in the colon, 8% in the rectum, and 9% in the peritoneum. In the review, 26% bled from stomal varices and a few from infrequent sites such as the ovary and vagina [ 24 ].

Portal biliopathy, which includes abnormalities (stricture and dilatation) of both extra and intrahepatic bile ducts and varices of the gallbladder, is associated with PH, particularly extrahepatic portal vein obstruction [ 25 , 26 ]. They are also seen associated with cirrhosis, non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis, and congenital hepatic fibrosis [ 27 ]. While a majority of these patients are asymptomatic, some present with a raised alkaline phosphatase level, abdominal pain, fever, and cholangitis. Choledocholithiasis may develop as a complication and manifest as obstructive jaundice with or without cholangitis [ 26 ]. On cholangiography, bile-duct varices may be visualized as multiple, smooth, mural-filling defects with narrowing and irregularity resulting from compression of the portal vein and collateral vessels. They may mimic PSC or cholangiocarcinoma (pseudocholangiocarcinoma sign) [ 28 ].

2.3. Portal Hypertensive Intestinal Vasculopathies

Mucosal changes in the stomach in patients with PH include portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) and gastric vascular ectasia. PHG describes the endoscopicappearance of gastric mucosa with a characteristic mosaic, or snake-skin-like appearance with or without red spots. It is a common finding in patients with PH [ 29 ]. The prevalence of PHG parallels the severity of PH and it is considered mild when only a mosaic-like pattern is present and severe when superimposed discrete red spots are also seen. Bleeding (acute or chronic) from these lesions is relatively uncommon, and rarely severe [ 30 ]. Patients with chronic bleeding usually present with chroniciron deficiency anemia.

In gastric vascular ectasia, collection of ectatic vessels can be seen on endoscopy as red spots without a mosaic-like pattern [ 31 ]. When the aggregates are confined to the antrum of the stomach, the term gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is used, and if aggregates in the antrum are linear, the term watermelon stomach is used to describe the lesion. The prevalence of GAVE syndrome in cirrhosis is low [ 32 ] and can be endoscopically difficult to differentiate from severe PHG. Therefore, gastric biopsy may be required to differentiate them as histologically GAVE lesions are completely distinct from PHG ( Table 4 ) [ 33 ].

Comparison of portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE).

PH: portal hypertension, TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Small bowel might also show mucosal changes related to PH, which is called portal hypertensive enteropathy (PHE). The diagnosis of PHE has been limited in the past due to the difficult access to the small bowel. With advanced endoscopic techniques such as capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy, PHE is now thought to be a frequent finding in patients with cirrhosis, perhaps as common as PHG, and may cause occult GI blood loss [ 34 , 35 ].

Portal hypertensive colopathy (PHC) refers to mucosal edema, erythema, granularity, friability, and vascular lesions of the colon in PH. PHC may be confused with colitis [ 36 , 37 ]. Although they are found in up to 70% of patients with PH and are more common in patients with EV and PHG, they rarely cause bleeding [ 38 , 39 ].

2.4. Ascites and Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP)

Ascites is defined as the accumulation of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. Cirrhotic PH is the most common cause of ascites, which accounts for approximately 75% patients with ascites. About 60% of patients with cirrhosis develop ascites during 10 years of observation [ 40 ]. The development of ascites is an important event in cirrhosis as the mortality is approximately 50% at 2 years without a liver transplantation [ 41 ]. The formation of ascites in cirrhosis is due to a combination of abnormalities in both renal function and portal and splanchnic circulation. The main pathogenic factor is sodium retention [ 42 ].

The main clinical symptom of patients with ascites is an increase in abdominal girth, often accompanied by lower-limb edema. In some cases, the accumulation of fluid is so severe that respiratory function and physical activity is impaired. In most cases, ascites develop insidiously over the course of several weeks. Patients must have approximately 1500 mL of fluid for ascites to be detected reliably by physical examination. Dyspnea in these patients can occur as a consequence of increasing abdominal distension and/or accompanying pleural effusions. Increased intra-abdominal pressure might favour the development of abdominal hernias (mainly umbilical) in patients with cirrhosis and longstanding ascites [ 43 ].

The current classification of ascites, as defined by the International Ascites Club, divides patients in three groups ( Table 5 ) [ 44 ]. Patients with refractory ascites are those that do not respond to sodium restriction and high doses of diuretics or develop diuretic-induced side effects that preclude their use.

International ascites club grading system for ascites.

Ascites may not be clinically detectable when present in small volumes. In larger volumes, the classic findings of ascites are adistended abdomen with a fluid thrill or shifting dullness. Ascites must be differentiated from abdominal distension due to other causes such as obesity, pregnancy, gaseous distension of bowel, bladder distension, cysts, and tumours. Ultrasonography is used to confirm the presence of minimal ascites and guide diagnostic paracentesis.

Successful treatment depends on an accurate diagnosis of the cause of ascites. Paracentesis with analysis of ascitic fluid is the most rapid and cost-effective method of diagnosis. It should be done in patients with ascites of recent onset, cirrhotic patients with ascites admitted to hospital, or those with clinical deterioration. The most important analyses are cell count, fluid culture, and calculation of the serum: ascites albumin gradient (SAAG), which reflects differences in oncotic pressures and correlates with portal venous pressure. It SAAG is greater or equal to 1.1 g/dL (or 11 g/L), ascites is ascribed to PH with approximately 97% accuracy [ 45 ].

Patients with cirrhosis and ascites are also at risk of developing infections, particularly spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). SBP occurs in approximately 10% of hospitalized cirrhotic patients [ 46 ], with an associated mortality of 20–40% if untreated [ 47 ]. Many patients are asymptomatic, but clinical signs can include abdominal pain, fever, and diarrhea. The diagnosis of SBP is based on neutrophil count >250 cells/mm 3 in the ascitic fluid.

3. Renal Manifestations

3.1. hepatorenal syndrome.

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a common complication seen in patients with advanced cirrhosis and PH [ 48 ]. HRS can also be seen in other types of severe chronic liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis, or in acute liver failure. This syndrome generally predicts poor prognosis [ 48 ]. HRS has been defined in the literature as a reversible functional renal impairment in the absence of other causes of renal failure, tubular dysfunction, proteinuria, or morphological alterations in histological studies. Precise and accurate diagnostic criteria have been established in order to clearly define this syndrome ( Table 6 ) [ 49 ]. The diagnosis remains one of exclusion.

Revised diagnostic criteria of Hepatorenal syndrome.

The reported incidence of HRS is approximately 10% among hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites. The probability of occurrence of HRS in patients with cirrhosis is around 20% after 1 year and 40% after 5 years [ 50 ]. The pathogenesis of HRS is not completely understood, but is likely the result of an extreme underfilling of the peripheral arterial circulation secondary to arterial vasodilatation in the splanchnic circulation [ 51 ]. In addition, recent data indicates that a reduction in cardiac output also plays a significant role [ 52 ].

HRS-associated renal failure is seen in late stages of cirrhosis and is marked by severe oliguria, increased sodium and water retention, volume overload, hyperkalemia, and spontaneous dilutional hyponatremia. There are two main subtypes of HRS described [ 49 ]. Type 1 HRS is a rapidly progressive renal failure that is defined by doubling of serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL (>221 μ moL/L) or a decrease of 50% in creatinine clearance (<20 mL/min) in less than 2 weeks. This form of HRS is usually precipitated by gastrointestinal bleeds, large volume paracenthesis, acute alcoholic hepatitis and SBP [ 53 ]. In addition to renal failure, patients with type 1 HRS present deterioration in the function of other organs, including the heart, brain, liver, and adrenal glands. The median survival of these patients without treatment is <2 weeks, and almost all of them die within 10 weeks after onset of HRS. Type 2 HRS is a moderate and stable renal failure with a serum creatinine of >1.5 mg/dL (>133 μ moL/L) that remains stable over a longer period and is characterized by diuretics resistant ascites [ 49 , 54 ].

4. Neurological Manifestations

4.1. hepatic encephalopathy.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is defined as neurologic and psychiatric dysfunction in a patient with chronic liver disease. The exact mechanism leading to this dysfunction is still poorly understood, but multiple factors appear to play a role in its genesis. The liver normally metabolizes ammonia, produced by enteric bacteria [ 56 ] and enterocytes [ 57 , 58 ]. In a patient with PH, ammonia bypasses the liver through portosystemic shunt and reaches the astrocytes in the brain. Within the astrocyte, ammonia is metabolized into glutamine, which acts as an osmole to attract water, thus causing cerebral edema. In addition, direct ammonia toxicity triggers nitrosative and oxidative stress, which lead to astrocyte mitochondrial dysfunction [ 59 , 60 ]. Another important factor is the enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA-A) receptors through neuroinhibitory steroids (i.e., allopregnanolone) [ 61 ] and benzodiazepine. Benzodiazepine also contributes to astrocyte swelling through a specific receptor [ 62 ]. Finally, tryptophane byproducts indole and oxindole [ 63 ], manganese [ 64 ], inflammation, hyponatremia [ 65 ], and reduced acetylcholine through acetylcholinesterase activity [ 66 ] also contribute to cerebral dysfunction.

The clinical manifestations of HE can be subtle. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy (grade 0) ( Table 7 ) can present with impaired driving ability [ 67 ], minimally impaired psychometric tests, decreased global functioning, and increased risk of falls [ 68 ]. In overt hepatic encephalopathy, diurnal sleep pattern changes will often precede neurologic symptoms. To add to the complexity, HE can be intermittent or persistent.

West Haven Criteria of Severity of Hepatic Encephalopathy (Adapted with permission [ 55 ]).

The severity of presentation is usually classified using the West Haven criteria ( Table 7 ). Grade 1 hepatic encephalopathy represents lack of awareness, anxiety or euphoria, and short attention span. Change of personality, lethargy, and inappropriate behavior can be seen in grade 2 encephalopathy. More advanced features include disorientation, stupor, confusion (grade 3), and can even reach coma (grade 4). Focal neurologic symptoms, including hemiplegia, may also be observed [ 69 ]. Physical examination may be normal, but typical signs include bradykinesia, asterixis, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes and even decerebrate posturing [ 55 ].

5. Pulmonary Manifestations

5.1. hepatopulmonary syndrome.

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is a triad of liver disease, pulmonary vascular ectasia and impaired oxygenation. HPS is defined in the literature as a widened alveolar-arterial oxygen difference (A-a gradient) in room air (>15 mm Hg or >20 mm Hg in patients > 64 years of age) with or without hypoxemia due to intrapulmonary vasodilatation in the presence of hepatic dysfunction [ 70 , 71 ]. This syndrome occurs mostly in those with PH (with or without cirrhosis) and indicates poor prognosis and higher mortality. Estimates of the prevalence of HPS among patients with chronic liver disease range from 4 to 47%, depending upon the diagnostic criteria and methods used [ 71 – 73 ].

HPS results in hypoxemia through pulmonary microvascular vasodilatation and intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunting resulting in ventilation-perfusion mismatch [ 74 ], and can occur even with mild liver disease [ 75 ]. Clinically, patients with HPS complain of progressive dyspnea on exertion, at rest, or both. Severe hypoxemia (PaO 2 < 60 mm Hg) is often seen and strongly suggests HPS [ 70 , 71 ]. A classical finding in HPS is orthodeoxia defined as a decreased arterial oxygen tension by more than 4 mm Hg or arterial oxyhemoglobin desaturation by more than 5% with changing position from supine to standing. It is associated with platypnea defined as dyspnea worsened by upright position [ 70 , 71 ]. Platypnea-orthodeoxia is caused by the worsening of diffusion-perfusion matching and increased shunting at the lung bases in the upright position. There are no hallmark signs on physical exam; however, cyanosis, clubbing, and cutaneous telangiectasia (spider nevi) are commonly noted. Furthermore, systemic arterioembolisation may cause stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, or brain abscess, and can present with neurological deficits.

5.2. Portopulmonary Hypertension

Portopulmonary hypertension (PPH), a well-recognized complication of chronic liver disease, refers to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) associated with PH when no alternative causes exist. It is defined by the presence of elevated pulmonary arterial pressure (mean pressure >25 mm Hg at rest and 30 mm Hg on exertion) elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (>240 dyne s −1 cm −5 ) in the presence of a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure <15 mm Hg [ 76 ].

The prevalence of PPH depends on the patient population studies and severity of the liver disease, 0.7–2% and 3.5–16.1% in cirrhotics and patients undergoing liver transplantation, respectively. The development of PPH is independent of the cause of PH, and it is often seen in cirrhosis. It is however, also described in those with PH due to nonhepatic pathologies such as portal venous thrombosis [ 71 , 77 ]. PH seems to be the driving force of PAH. The pathogenesis of PPH is not completely understood; however, several theories have been offered. The most widely accepted theory is that a humoral vasoactive substances (e.g., serotonin, endothelin-1, interleukin-1, thromboxane B2, and secretin), normally metabolized by the liver, is able to reach the pulmonary circulation via portosystemic shunts, resulting in PPH [ 71 , 78 , 79 ].

Clinically, most patients with PPH present with evidence of both PAH and PH. Typically manifestations of PH precede those of PAH. The most common presenting symptom is progressive dyspnea on exertion [ 80 ] and less frequently fatigue, palpitations, syncope, hemoptysis, orthopnea, and chest pain. On physical exam, classical features include edema, an accentuated P2 and a systolic murmur, indicating tricuspid regurgitation [ 71 , 77 , 80 ]. In severe cases, signs and symptoms of right-heart failure can be noted.

5.3. Hepatic Hydrothorax

Hepatic hydrothorax is an uncommon complication of end-stage liver disease. It is defined as a pleural effusion greater than 500 mL in patients with cirrhosis in absence of primary cardiac, pulmonary, or pleural disease [ 81 ]. The underlying pathogenesis of hepatic hydrothorax is incompletely understood. Patients with cirrhosis and PH have abnormal extracellular fluid volume regulation resulting in passage of ascites from the peritoneal space to the pleural cavity via diaphragmatic defects generally in the tendinous portion of the diaphragm [ 82 ]. Negative intrathoracic pressure during inspiration pulls the fluid from the intra-abdominal cavity into the pleural cavity. Hydrothorax develops when the pleural absorptive capacity is surpassed, leading to accumulation of fluid in the pleural space. Multiple studies have shown the passage of fluid from the intra-abdominal space to the pleural space via 99mTc-human albumin or 99mTc-sulphur colloid [ 81 ].

Clinical manifestations of hepatic hydrothorax include shortness of breath, cough, hypoxemia, and chest discomfort [ 81 ]. Ascites may not always be present. Hepatic hydrothorax should always be suspected in patients with cirrhosis or PH and undiagnosed pleural effusion, regardless of the presence of ascites. Serious complications include acute tension hydrothorax with dyspnoea and hypotension [ 83 ] and spontaneous bacterial empyema [ 84 ].

6. Other Organs Manifestations

6.1. cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.

Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy is defined as a chronic cardiac dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis. It occurs in up to 50% of patients with advanced cirrhosis. It is characterized by impaired contractile response and/or altered diastolic relaxation in the absence of other cardiac diseases. The pathophysiology of this condition is complex, and seemingly related to PH and cirrhosis. In advanced liver disease, splanchnic vasodilatation leads to a resting hyperdynamic state [ 85 ]. Plasma volume expands, leading to a relative central volume decrease [ 86 ]. In cirrhosis, the arterial vessel wall thickness and tone decreases, leading to reduced arterial compliance [ 87 , 88 ]. Autonomic dysfunction may also contribute to blunted cardiac response [ 89 ]. Ultimately, these factors lead to systolic and diastolic dysfunction.

Symptoms associated with cirrhotic cardiomyopathy include dyspnea with exertion, impaired exercise capacity, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, peripheral edema, and orthopnea. Less-frequent presentations include long QT on electrocardiography, arrhythmia, and sudden death [ 90 ].

6.2. Hepatic Osteodystrophy

Hepatic osteodystrophy is defined as bone disease (osteomalacia, osteoporosis, and osteopenia) associated with liver disease. Osteomalacia and osteoporosis are frequently seen in cirrhotic patients and can predispose to pathologic fractures. The pathophysiology of osteoporosis in liver disease is relatively complex. The leading hypothesis suggests that it is related to the uncoupling of osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity. Osteoclastogenic proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin 1(Il-1) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF α )) are increased in hepatic fibrosis. Moreover, TNF α is increased in a rat model of PH [ 91 ]. Decreased osteoblastic activity has also been linked with insulin-like growth factor 1 in a rat model (IGF-1). Increasing IGF-1 levels are associated with liver disease severity [ 92 ]. Finally, vitamin K mediates the carboxylation of glutamyl residues on osteocalcin, stimulating osteoclastic activity [ 93 ].

Patients with osteoporosis are usually asymptomatic. They may present with pain following a nontraumatic fracture of the axial skeleton or bone deformity, including pronounced cervical kyphosis. Osteomalacia presentation is similar and includes proximal muscle weakness [ 94 ].

6.3. Hypersplenism

Hypersplenism is a common complication of massive congestive splenomegaly in patients with cirrhosis and PH. In this condition, splenomegaly is associated with thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, or anemia or a combination of any the three [ 95 , 96 ]. Severe hypersplenism is present in about 1/3 of patients with cirrhosis being assessed for liver transplantation. Most patients have no symptoms related to hypersplenism, however severe thrombocytopenia may increase the risk of bleeding, especially after invasive procedures.

7. Conclusion

Portal hypertension secondary to cirrhosis has multisystem effects and complications. Once a patient develops such complications, they are considered to have decompensated disease with the high morbidity and mortality. The quality of life and survival of patients with cirrhosis can be improved by the prevention and treatment of these complications.

Achieve Mastery of Medical Concepts

Study for medical school and boards with lecturio.

USMLE Step 1 | USMLE Step 2 | COMLEX Level 1 | COMLEX Level 2 | ENARM | NEET

Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension is increased pressure in the portal venous system. This increased pressure can lead to splanchnic vasodilation Vasodilation The physiological widening of blood vessels by relaxing the underlying vascular smooth muscle. Pulmonary Hypertension Drugs , collateral blood flow Blood flow Blood flow refers to the movement of a certain volume of blood through the vasculature over a given unit of time (e.g., mL per minute). Vascular Resistance, Flow, and Mean Arterial Pressure through portosystemic anastomoses Portosystemic anastomoses Systemic and Special Circulations , and increased hydrostatic pressure Hydrostatic pressure The pressure due to the weight of fluid. Edema . There are a number of etiologies, including cirrhosis Cirrhosis Cirrhosis is a late stage of hepatic parenchymal necrosis and scarring (fibrosis) most commonly due to hepatitis C infection and alcoholic liver disease. Patients may present with jaundice, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly. Cirrhosis can also cause complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, portal hypertension, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatorenal syndrome. Cirrhosis , right-sided heart failure Right-Sided Heart Failure Ebstein’s Anomaly , schistosomiasis Schistosomiasis Infection with flukes (trematodes) of the genus schistosoma. Three species produce the most frequent clinical diseases: Schistosoma haematobium (endemic in Africa and the Middle East), Schistosoma Mansoni (in Egypt, northern and southern Africa, some West Indies islands, northern 2/3 of South america), and Schistosoma japonicum (in Japan, China, the Philippines, Celebes, Thailand, Laos). S. mansoni is often seen in Puerto Ricans living in the United States. Schistosoma/Schistosomiasis , portal vein Portal vein A short thick vein formed by union of the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein. Liver: Anatomy thrombosis Thrombosis Formation and development of a thrombus or blood clot in the blood vessel. Epidemic Typhus , hepatitis, and Budd-Chiari syndrome Budd-Chiari syndrome Budd-Chiari syndrome is a condition resulting from the interruption of the normal outflow of blood from the liver. The primary type arises from a venous process (affecting the hepatic veins or inferior vena cava) such as thrombosis, but can also be from a lesion compressing or invading the veins (secondary type). The patient typically presents with hepatomegaly, ascites, and abdominal discomfort. Budd-Chiari Syndrome . Most individuals are asymptomatic until complications arise, including esophageal varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy gastropathy Damage to the epithelial lining with no or minimal associated inflammation and is technically a separate entity from gastritis Gastritis , ascites Ascites Ascites is the pathologic accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity that occurs due to an osmotic and/or hydrostatic pressure imbalance secondary to portal hypertension (cirrhosis, heart failure) or non-portal hypertension (hypoalbuminemia, malignancy, infection). Ascites , and hypersplenism Hypersplenism Condition characterized by splenomegaly, some reduction in the number of circulating blood cells in the presence of a normal or hyperactive bone marrow, and the potential for reversal by splenectomy. Splenomegaly . The diagnosis is clinical, but it can be supported by ultrasound findings (and hepatic venous pressure gradient Pressure gradient Vascular Resistance, Flow, and Mean Arterial Pressure measurement in unclear cases). Management requires treating the underlying etiology and managing the complications. This can include nonselective beta blockers to prevent bleeding from varices, diuretics Diuretics Agents that promote the excretion of urine through their effects on kidney function. Heart Failure and Angina Medication and sodium Sodium A member of the alkali group of metals. It has the atomic symbol na, atomic number 11, and atomic weight 23. Hyponatremia restriction for ascites Ascites Ascites is the pathologic accumulation of fluid within the peritoneal cavity that occurs due to an osmotic and/or hydrostatic pressure imbalance secondary to portal hypertension (cirrhosis, heart failure) or non-portal hypertension (hypoalbuminemia, malignancy, infection). Ascites , and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt A type of surgical portosystemic shunt to reduce portal hypertension with associated complications of esophageal varices and ascites. It is performed percutaneously through the jugular vein and involves the creation of an intrahepatic shunt between the hepatic vein and portal vein. The channel is maintained by a metallic stent. The procedure can be performed in patients who have failed sclerotherapy and is an additional option to the surgical techniques of portocaval, mesocaval, and splenorenal shunts. It takes one to three hours to perform. Ascites for refractory complications.

Last updated: Jul 7, 2023

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Clinical presentation, clinical relevance.

Share this concept:

The etiologies of portal hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension can be classified based on the location of increased resistance Resistance Physiologically, the opposition to flow of air caused by the forces of friction. As a part of pulmonary function testing, it is the ratio of driving pressure to the rate of air flow. Ventilation: Mechanics of Breathing to blood flow Blood flow Blood flow refers to the movement of a certain volume of blood through the vasculature over a given unit of time (e.g., mL per minute). Vascular Resistance, Flow, and Mean Arterial Pressure through the liver Liver The liver is the largest gland in the human body. The liver is found in the superior right quadrant of the abdomen and weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms. Its main functions are detoxification, metabolism, nutrient storage (e.g., iron and vitamins), synthesis of coagulation factors, formation of bile, filtration, and storage of blood. Liver: Anatomy .

Prehepatic etiologies:

- Portal vein Portal vein A short thick vein formed by union of the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein. Liver: Anatomy thrombosis Thrombosis Formation and development of a thrombus or blood clot in the blood vessel. Epidemic Typhus

- Splenic vein thrombosis Thrombosis Formation and development of a thrombus or blood clot in the blood vessel. Epidemic Typhus

- Massive splenomegaly Massive Splenomegaly Splenomegaly

- Splanchnic arteriovenous fistula Arteriovenous fistula An abnormal direct communication between an artery and a vein without passing through the capillaries. An a-v fistula usually leads to the formation of a dilated sac-like connection, arteriovenous aneurysm. The locations and size of the shunts determine the degree of effects on the cardiovascular functions such as blood pressure and heart rate. Vascular Surgery

Hepatic etiologies:

- Schistosomiasis Schistosomiasis Infection with flukes (trematodes) of the genus schistosoma. Three species produce the most frequent clinical diseases: Schistosoma haematobium (endemic in Africa and the Middle East), Schistosoma Mansoni (in Egypt, northern and southern Africa, some West Indies islands, northern 2/3 of South america), and Schistosoma japonicum (in Japan, China, the Philippines, Celebes, Thailand, Laos). S. mansoni is often seen in Puerto Ricans living in the United States. Schistosoma/Schistosomiasis

- Early primary biliary cholangitis Primary Biliary Cholangitis Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a chronic disease resulting in autoimmune destruction of the intrahepatic bile ducts. The typical presentation is that of a middle-aged woman with pruritus, fatigue, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Elevated liver enzymes and antimitochondrial antibodies (AMAs) establish the diagnosis. Primary Biliary Cholangitis

- Granulomatous disease Granulomatous disease A defect of leukocyte function in which phagocytic cells ingest but fail to digest bacteria, resulting in recurring bacterial infections with granuloma formation. When chronic granulomatous disease is caused by mutations in the cybb gene, the condition is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. When chronic granulomatous disease is caused by cyba, ncf1, ncf2, or ncf4 gene mutations, the condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID) (e.g., sarcoidosis Sarcoidosis Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease that causes noncaseating granulomas. The exact etiology is unknown. Sarcoidosis usually affects the lungs and thoracic lymph nodes, but it can also affect almost every system in the body, including the skin, heart, and eyes, most commonly. Sarcoidosis )

- Congenital Congenital Chorioretinitis hepatic fibrosis Hepatic fibrosis Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD)

- Polycystic liver Liver The liver is the largest gland in the human body. The liver is found in the superior right quadrant of the abdomen and weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms. Its main functions are detoxification, metabolism, nutrient storage (e.g., iron and vitamins), synthesis of coagulation factors, formation of bile, filtration, and storage of blood. Liver: Anatomy disease

- Idiopathic Idiopathic Dermatomyositis noncirrhotic portal hypertension Hypertension Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a common disease that manifests as elevated systemic arterial pressures. Hypertension is most often asymptomatic and is found incidentally as part of a routine physical examination or during triage for an unrelated medical encounter. Hypertension

- Cirrhosis Cirrhosis Cirrhosis is a late stage of hepatic parenchymal necrosis and scarring (fibrosis) most commonly due to hepatitis C infection and alcoholic liver disease. Patients may present with jaundice, ascites, and hepatosplenomegaly. Cirrhosis can also cause complications such as hepatic encephalopathy, portal hypertension, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatorenal syndrome. Cirrhosis (most common cause in Western countries)

- Acute alcoholic Alcoholic Persons who have a history of physical or psychological dependence on ethanol. Mallory-Weiss Syndrome (Mallory-Weiss Tear) hepatitis

- Viral hepatitis

- Vitamin A Vitamin A Retinol and derivatives of retinol that play an essential role in metabolic functioning of the retina, the growth of and differentiation of epithelial tissue, the growth of bone, reproduction, and the immune response. Dietary vitamin A is derived from a variety of carotenoids found in plants. It is enriched in the liver, egg yolks, and the fat component of dairy products. Fat-soluble Vitamins and their Deficiencies intoxication

- Postsinusoidal: hepatic veno-occlusive disease

Posthepatic etiologies:

- Right-sided heart failure Right-Sided Heart Failure Ebstein’s Anomaly

- Severe tricuspid regurgitation Regurgitation Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- Constrictive pericarditis Constrictive pericarditis Inflammation of the pericardium that is characterized by the fibrous scarring and adhesion of both serous layers, the visceral pericardium and the parietal pericardium leading to the loss of pericardial cavity. The thickened pericardium severely restricts cardiac filling. Clinical signs include fatigue, muscle wasting, and weight loss. Pericarditis

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy Restrictive Cardiomyopathy Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is a fairly uncommon condition characterized by progressive stiffening of the cardiac muscle, which causes impaired relaxation and refilling of the heart during diastole, resulting in diastolic dysfunction and eventual heart failure. Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

- Noncardiac: Budd-Chiari syndrome Budd-Chiari syndrome Budd-Chiari syndrome is a condition resulting from the interruption of the normal outflow of blood from the liver. The primary type arises from a venous process (affecting the hepatic veins or inferior vena cava) such as thrombosis, but can also be from a lesion compressing or invading the veins (secondary type). The patient typically presents with hepatomegaly, ascites, and abdominal discomfort. Budd-Chiari Syndrome

Pathophysiology

- Supplies 25% of the liver Liver The liver is the largest gland in the human body. The liver is found in the superior right quadrant of the abdomen and weighs approximately 1.5 kilograms. Its main functions are detoxification, metabolism, nutrient storage (e.g., iron and vitamins), synthesis of coagulation factors, formation of bile, filtration, and storage of blood. Liver: Anatomy ’s blood supply

- Carries oxygenated blood

- Supplies 75% of blood supply

- Formed most commonly by the union of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins Veins Veins are tubular collections of cells, which transport deoxygenated blood and waste from the capillary beds back to the heart. Veins are classified into 3 types: small veins/venules, medium veins, and large veins. Each type contains 3 primary layers: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. Veins: Histology

- Carries oxygen-poor, nutrient-rich blood drained from the abdominal organs

- Venous drainage: sinusoids Sinusoids Liver: Anatomy → central vein of each lobule → hepatic veins Veins Veins are tubular collections of cells, which transport deoxygenated blood and waste from the capillary beds back to the heart. Veins are classified into 3 types: small veins/venules, medium veins, and large veins. Each type contains 3 primary layers: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. Veins: Histology → inferior vena cava Inferior vena cava The venous trunk which receives blood from the lower extremities and from the pelvic and abdominal organs. Mediastinum and Great Vessels: Anatomy ( IVC IVC The venous trunk which receives blood from the lower extremities and from the pelvic and abdominal organs. Mediastinum and Great Vessels: Anatomy )

- Alternative routes of circulation Circulation The movement of the blood as it is pumped through the cardiovascular system. ABCDE Assessment ensure venous drainage of the abdominal organs even if a blockage occurs in the portal system.

- Left gastric veins Veins Veins are tubular collections of cells, which transport deoxygenated blood and waste from the capillary beds back to the heart. Veins are classified into 3 types: small veins/venules, medium veins, and large veins. Each type contains 3 primary layers: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. Veins: Histology and lower esophageal veins Veins Veins are tubular collections of cells, which transport deoxygenated blood and waste from the capillary beds back to the heart. Veins are classified into 3 types: small veins/venules, medium veins, and large veins. Each type contains 3 primary layers: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. Veins: Histology