From Research to Policy Action: Communicating Research for Public Policy Making

- Open Access

- First Online: 19 October 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- E. Remi Aiyede 3

8181 Accesses

1 Citations

This chapter underscores the importance of engaging policy makers and other stakeholders in the research process. Recognizing that there are two dimensions, the demand and supply sides to the use of evidence in policy making, it discusses the various instruments and platforms for communicating research to make it accessible to a variety of stakeholders.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

New directions in evidence-based policy research: a critical analysis of the literature

Evidence-Based Decision-Making 8: Health Policy, a Primer for Researchers

Tempest in a teapot toward new collaborations between mainstream policy process studies and interpretive policy studies, introduction.

The growing concern that scientific research and the academic community in general do not meaningfully engage the world of public policy is not entirely new. The “two communities” construct is widely used to describe the sharp disconnect between the worlds of academia and policy (Newman et al. 2015 ). This construct generally depicts the existence of an underutilization or, in most cases, non-utilization of scientific research in the policy making process. Although policy makers recognize that scientific research has the potential to largely inform and transform policy outcomes and is in fact an essential determinant of effective government decision making, wide communication gap continues to exist between both worlds.

There is a growing interest in connecting scientific research, with its rigour of methodology and finesse of analysis, to the world that it is expected to influence and change. It is indeed crucial to expand research findings beyond the boundaries of the academic community to reach policy makers as they intervene through their daily activities to solve societal problems. Furthermore, evidence from policy makers in various parts of the world shows that the quality of research does not automatically guarantee that it will make its way to the appropriate stakeholders and generate positive impact. Promoting the utilization of scientific research and supporting evidence-informed decision making at the political level requires a better understanding of the enablers. What are the major challenges that militate against collaboration and knowledge transfer from scientific research to policy making process? How can policy makers maximize the underutilized potentials in scientific research? What tools of communication are appropriate to make research accessible to various stakeholders?

A Movement for Policy-Engaged Research

Across the world the concern about evidence-informed policy making has gained traction. A few governments, like those of the United Kingdom and the United States, and non-state organizations like the International Rescue Committee and the Hewlett Foundation, have placed premium on policy-engaged research. They have invested efforts in moving relevant findings from research institutions and academic outlets to the policy process. Also, the Centre for Global Development and a few foundations have promoted the development of research through engagement with stakeholders and translating the outputs from research into forms that could reach a wider audience, especially stakeholders and strategic policy actors. Indeed, White ( 2019 ) considered the current state of the engagement as an evidence revolution. He identified four waves of the evidence revolution. He traced the first wave to the results agenda of the 1990s that came with the New Public Management or managerial movement in public administration. The emphasis was on outcome as against the previous focus on inputs. This was followed by efforts to develop indicators to measure performance. In the international development community, it witnessed the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals, later succeeded by the Sustainable Development Goals and the widespread use of the “Results Framework”. The limitations of the results framework as a measure of agency performance were that goals set by agencies were often too broad and affected by multiple factors for clear attribution.

The second wave was defined by the rise of the use of randomized control trials (RCTs) in impact evaluation and the emergence of the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. The results from the burgeoning RCTs showed that interventions often do not work. They are often less than 20% in effect, with exception from some experiences in Africa. Wary of the duplication of dubious interventions that studies have shown to have no effects, some organizations such as the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Bill Melinda Gates Foundation demand a statement of evidence from rigorous studies to support new proposals. Furthermore, to establish buy-in, preference was given to a larger set of literature rather than a small number of studies. This led to the emergence and popularity of systematic literature reviews.

Systematic reviews marked the third wave of the evidence revolution. Systematic reviews for all their values posed problems of discoverability and accessibility by policy makers because they are long technical documents. There was need to translate lessons and ideas from these reviews for use by policy makers. He described the production of systematic reviews for use in the policy process as knowledge brokerage and knowledge translation.

He therefore named the fourth wave the brokering wave, defined by the emergence of “researchers whose incentive is to produce systematic reviews relevant for policy and practice”. These researchers are engaged in knowledge brokerage, by providing evidence as responses to the needs of government for informed decision making. Apart from doing reviews, these researchers connect with government agencies that need evidence to discuss priorities, available evidence and interpret them for decision making. They represent the part of an emerging evidence architecture that can institutionalize the use of evidence in policy making. He then described the dimensions of an emerging evidence architecture that will institutionalize the use of evidence in the policy process. Important parts of this architecture included legislation requiring evidence-based policy like the United States 2018 Evidence-based Policy Making Act, data bases that contain studies and reviews, evidence mapping and maps, evidence platforms for user-friendly products, evidence portals, guidelines and checklists. The evolving architecture has benefitted from the what works movement. The goals of the evidence movement can be advanced if the international development community invest in the evidence architecture beyond knowledge brokerage. He emphasized the need to undertake Evidence Ecosystem Assessment, Evidence gaps mapping and evidence-based budgeting. Finally, new technologies such as machine learning, big data and Artificial Intelligence constitute important factors in building the evidence architecture, according to White ( 2019 ). These technologies can facilitate systematic reviews, speed and accuracy of evidence synthesis. These mean that more investment on what works is required.

Demand and Supply Side Challenges in the Use of Scientific Research in the Policy Making Process

Despite the claim of an evidence revolution in the international development policy process, it is generally agreed that the use of evidence is not a settled matter in many countries. Indeed, the claim of an evolving architecture shows very clearly that there are major grounds yet to be covered even in the developed world. How many countries have legislations that require evidence-based policy making? In how many countries of the world can we point to an emerging evidence architecture? In Africa, a few countries have only begun to buy into establishing national evaluation policies and national evaluation systems. These mean that many African countries are still grappling with the results frameworks. As is often the case, many of the policies relating to monitoring and evaluation have been driven by donors and international development agencies such as the DFID. Thus, any engagement with research communication and the use of evidence in policy making must focus on both the demand and supply side. White’s ideas of the evidence architecture provide insight into what is emerging and future possibilities.

Studies on challenges of research communication and the use of evidence in policy have focused on three dimensions in bridging the gap between the world of research and policy (Wimberley and Morris 2007 ). The first dimension is focused on academics. The second is on practitioners and policy actors. The third is the intermediaries who broker within the policy process to promote interaction between the suppliers of research outputs and practitioners or actors who utilize research results for decision making. Thus, studies on research uptake for policy relate to both researchers who supply evidence and practitioners who use evidence in decision and policy making within the dynamic contexts of policy making processes around the world. Such studies also address various ways interventions can be made to smoothen and sustain the connections, to address the challenges of achieving evidence-informed policy making (Oliver and Cairney 2019 ). Some of these challenges are similar across the policy world, while others are contextual challenges, deriving from the nature of specific policy contexts (Wowk et al. 2017 , Phoenix et al. 2019 ).

While the academic environment is a marketplace of contending ideas, the policy process is a place of contending values and interests. These mean that the researcher who wants to take her/his ideas to the policy process must recognize that her/his ideas would face scrutiny. Thus, the quality of research is considered very important and has consequences for the goal of influencing policy. Secondly, it cannot be assumed that policy makers are impervious to research ideas (Newman et al. 2015 ). Scholars must consider the various policy networks and communities, and the effective ways to engage them. In this regard, there are several prescriptions on offer to academics who want to make an impact on the policy process. A lot of the literature on research communication have focused on the supply side. Cairney and Oliver ( 2020 ) provide a survey of such prescriptions derived from concerns about breaking barrier and overcoming obstacles to communication between researchers and practitioners and advancing collaboration, recognizing that academic research is not traditionally designed to feed the policy process. These include the following:

Researchers should produce high-quality research.

They should evolve an effective means of communicating research with the goal of making it easier for policy makers to access research. This relates to presentation of the content of research outputs: the elimination of academic and disciplinary jargons, use of simple, readable and accessible language, aimed for the general and not the ignorant or specialist reader, and the use techniques and forms that can fit into and catch the attention of policy makers.

Engagement with the policy process. Researchers are urged to connect with practitioners, be accessible to policy makers, take advantage of windows of opportunity, and use intermediaries or knowledge brokers.

Pay attention to the context and process of policy and the key actors in the process.

Scholars must be entrepreneurial or active in the policy process, seek collaboration and build relationships.

Academics should co-produce knowledge with practitioners; this is considered one of the best guarantees of the use of evidence in the policy process.

It is however recognized that there are ethical dilemmas and practical challenges around these prescriptions faced by individual researchers in higher education. Indeed, there are several reasons why concern about policy relevance may not to be a priority for these researchers. Time, effort and resources are involved in trying to implement these prescriptions. Everyone cannot be excited by the possibilities and opportunities to make an impact in solving real-world problems. Besides, the probability of making such an impact is often remote as noted from the experience with the results framework even in developed countries (Cairney and Kwiatkowski 2017 ; Egbetokun et al. 2020 ).

From the perspectives of policy context, policy theory provides us with several ideas about the policy process that requires reflection concerning our expectation of promoting the use of evidence (Cairney and Oliver 2020 ). Academic institutions do not provide incentives for those interested in making an impact. In many universities, promotion is not tied to relevance and impact of research. Promotion is tied to publishing in professional and specialized journals of the various disciplines, through which academics communicate with one another, the scientific community. However, breaking out of the ivory tower and reaching out to practitioners may even require specific training or reorientation and few universities invest in such an enterprise. The policy conscious academic would have to go the extra mile of finding ways and means of implementing such prescriptions without institutional incentive.

Policy makers are usually faced with issues that offer a limited time for decision making while scientists take years to publish research findings and they examine issues over a long period of time. There may be a misfit of priorities between scientists and policy makers. The value of communicating one’s research findings with policy makers to produce accessible reports within a short time is not as valuable as securing funding for new research and publishing it in high-status journals with a long-time lag (Cairney 2016 ). Besides, there is a risk of failure to impact regardless of the efforts invested by the individual. This is because the payoff to engagement may be affected by choices already made and reinforced over time within the policy process.

In developing country contexts, there is a challenge of access to the policy process that is already saturated with agenda-laden ideas promoted by powerful western institutions backed by resources. In other words, the challenge of the academic in a developing context is complicated by an unequal access to the policy process. In many African countries, donors and international institutions have a hold in the policy process that may stand in the way of alternative ideas. Such organizations often support their policy preferences with funding that make it impossible for policy makers to resist. In many instances, international policy initiatives have supplanted national policy making (see Mkandawire 1997 ).

In general, it must be recognized that not all researchers would become interested in making a difference in the world regardless of the available incentive to do so. Some would be interested in extending the frontiers of knowledge with the hope that those interested in impacting would pick up their ideas for use in the policy process. Pielke ( 2007 ) provides a typology of policy orientations among scientists regarding influencing public policy: the pure scientist, the issue advocate, the science arbiter and the honest broker. These draw on the typology of research, in terms of the nature and purpose of research. For instance, a distinction is often made between basic and applied research. Basic research is not focused on intervention while applied research targets practice.

The research activities of the pure scientist have no consideration for use or utility of research outputs for decision makers. The importance attached to research is the original contribution to the repository of knowledge. It is the responsibility of those who want to use the knowledge to search for it. They can then draw on the knowledge to clarify and solve issues of public interests. Thus, the pure scientist remains removed from the messiness of policy and politics. This position is particularly appealing if it is recognized that evidence is not the only factor to be considered in public decision making. As noted earlier, in many universities, scholars do not have to demonstrate the impact of their work for promotion. Many scholars are quite content with their roles as scientists and feel not burden to impact the policy process.

On the other hand, the issue advocate is concerned about a political or ideological position and deploys research to advance a cause. The issue advocate is a programmatic scholar or scholar activist who aligns with an interest group or movement seeking to advance policy and politics. For scholars in this orientation, science must be engaged with policy and seek to participate in the decision-making process. This orientation relates with scholars who question the neutrality of science, the argument that values and preferences of the scientist come to play in the choice of issues and priorities of research which we find in critical theory, standpoint epistemologies and similar schools. For such scholars, scientists should be concerned about changing the world and bring scientific knowledge to serve the cause of justice and the public interest.

The third orientation is the science arbiter, who seeks to stay away from explicit considerations of policy and politics but recognizes that as experts or technocrats in society, he or she should provide advice when called upon by decision makers. Decision makers are sometimes confronted with specific questions that require expert judgement. Although the question originates from a debate among decision makers who are faced with practical issues, they require expert knowledge. Questions that can be resolved by science have to be taken to the experts. In this context, the scientist plays no role of an advocate, but that of an adjudicator, who may be on an assessment panel or advisory committee, providing policy makers objective scientific results, assessments or findings.

The fourth type, the honest broker, seeks to pursue the expansion of policy alternatives that can inform decision making by clarifying choices available to decision makers. The aim is to integrate scientific knowledge with stakeholder concerns in the form of alternative possible courses of action. It is recognized that there may be conflict of values among stakeholders and uncertainty in science. But a diversity of perspectives can help place scientific understandings in the context of a wide range of interests. Thus, the scholar concerned about influencing policy must recognize that he or she is part of a community of scholars as well recognize the difficulties of interacting with the policy community with its challenges and opportunities.

It is critical that scientists bring their research findings to bear on the policy process. In many instances, research findings have led to the development of policy agenda and the prioritization of certain issues and effective solutions. It is central to the policy sciences that research is focused on issues that are relevant to policy and decision making. Public policy scholars necessarily seek to address policy issues. This is shown in the level of engagement with the policy actors within the research process, from the conception, execution of research and the implementation of its policy recommendations.

Contemporary social science methodology affirms the need for research to play a vital role in transforming society by advancing socially relevant research findings. Ojebode et al. ( 2018 ) in a study conducted among 400 social science and humanities researchers found that whereas researchers held different views about the type of researcher Africa needed the most, most of them agreed that Africa did not need pure scientists as much as other types (honest brokers and issue advocates) based on Pielke’s ( 2007 ) categorization of researchers.

Public policy scholars conduct research to understand and improve public policy, to advance knowledge in a variety of policy issues and to conduct public policy research for government, business, think tanks and other research organizations. They are expected to actively seek to influence public policy making. This is because public policy as field of study is problem-solving oriented and seeks to provide intervention to address concrete human problems. Such scholars seek to provide expert knowledge in the form of evidence to inform policy making. To do this effectively, they must understand where and how public policy practitioners’ and policy makers get scientific information.

It is equally important to have a clear idea who the policy makers are regarding specific policy issues. Policy makers could include anyone from the president or leader of government, the legislators, the senior public servants, judges or even ordinary citizens. We include ordinary citizens because they sometimes play key roles as implementers, catalysts or beneficiaries of public policy. Hence, knowledge is required for them to be effective players. For instance, during the covid-19 pandemic the general populace was the target of policies to stem the spread of the virus. They were expected to sit at home, wear nose masks and regularly wash their hands. They need to be informed and convinced about the scientific basis of this requirement to achieve voluntary compliance. Without this information available to the public, achieving significant compliance would have been impossible given the level of resistance experienced all over the world.

In general, the news media is a major source of information for policy makers. Politicians who are elected to make public policy on behalf of their constituencies pay attention to the news. The media sets the agenda by reporting what is of interest to the various communities. Politicians pay attention to what matters to their constituents. The news media include newspapers and magazines, the broadcast platforms of television and radio, and social media such as twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and WhatsApp of which they get regular alerts. These media are ubiquitous and are influential sources of information.

In addition to the media, government agencies and departments produce reports and white papers to guide policy makers. Governments have think-tanks, regulatory agencies that monitor developments in such areas as environmental protection, drug administration, sanitation, etc. They also set up commissions to investigate issues such as the Panel of Inquiry frequently used in Nigeria, or the various Committees, (such as the Davis Tax Committee in South Africa) and Commissions of inquiry used across Africa. These bodies provide reports as source of policy decision making for both parliament and the executive arm of government.

Another source of information is the various public hearings organized by the legislature or any of its committees. These hearings provide opportunity for individuals and groups to present written memoranda or speak on issues of concern or focus on such hearing events.

These mean that policy researchers must use these opportunities to communicate research findings. It is becoming the norm that outputs from research are translated into forms that are accessible to policy makers. These included policy briefs, press releases or opinion pieces, blogs and twits. These can be circulated through traditional or social media. The assumption is that the barriers to evidence-informed policy from the perspective of the policy makers can be classified into three:

Available evidence may not be used if policy makers are not aware of their existence and if the research evidence is not in a format that is accessible to policy maker. When policy makers do not have access to timely, quality and relevant research evidence, they resort to other sources of information beyond research. They may not be able to comprehend and identify the key messages from research outputs, not to talk of using the evidence from research outputs, including systematic reviews, if they are detailed and couched in technical language for their decision making. Policy makers may be overwhelmed by the vast amount of information they need to go through to deal with a particular case. Thus, research outputs must be presented in easily accessible format to facilitate their use.

Even when research evidence is presented in accessible format and policy makers are aware of its existence, they may resist the use of evidence if the sub-cultures of policy making grant little importance to evidence-informed solutions. Some of them may prioritize their own opinion when research findings go against their expectations or against current policy. Thus, methods to disseminate evidence must be done in a way that policy makers will be open to receive and consider. There is need to recognize that policy makers tend to interpret new information based on their past attitudes and beliefs, much like the general population. Research evidence may be disregarded if it goes contrary to the political environment or ideological orientation of the prevailing government.

Research needs to be sensitive to different contexts and the competitive environment of policy making. Several factors are implicated in the use or non-use of evidence in policy making. These factors include political and institutional factors such as the level of state centralization and democratization, the influence of external organizations and donors, the organization of bureaucracies and the social norms and values. This implies that policy makers make choices between different priorities while taking into consideration the limited resources available. When policy makers engage scientific research, they make judgements that balances different opinions, as well as claims and counterclaims from interest groups, including scientists. Policy makers do not necessarily hold the same value orientations with scientists on the drive to produce scientific knowledge. They do not see scientific knowledge as less biased than other forms of knowledge such as community and cultural knowledge (Cairney 2016 )

The various platforms listed above for the dissemination of research evidence are useful to achieve uptake because they enable research findings to be more accessible to non-scientific audiences and policy makers. A blog writing is easily accessed and digested by a broad audience who can understand and perhaps apply the key messages from the research output. In addition, a blog creates the opportunity for a more conversational interaction with the audience than an academic publication. By using techniques such as good keyword identification, it is more likely to rank more highly in search engines, increasing the visibility and uptake of blog post. Converting the research output into a blog post enables the researcher to present academic papers, including the title used, in a way that engage with the audience. By converting a research paper to a blog, researchers achieve the positive flow-on effect of research outputs, distilling and presenting some of the key messages for a defined audience. They can also amplify those messages to create a convincing story.

Policy briefs are an information-packaging documents used to support evidence-informed policy making. The name policy brief may also be used interchangeably with the technical note, policy note, evidence brief, evidence summary, research snapshot, etc. (Dagenais and Ridde 2018 ). A policy brief is easier to handle by policy makers than systematic reviews because they are precise documents, taking into consideration the time scales and simplicity required by a non-technical audience. The policy brief may be used to clarify and improve the understanding of a problem or a situation, to confirm or justify a decision or a choice, which has already been made (Arnautu, Diana and Christian Dagenais 2021 ). The policy brief presents the evidence in a manner that is easily identified, interpreted and considered to better inform the parties involved in a policy issue.

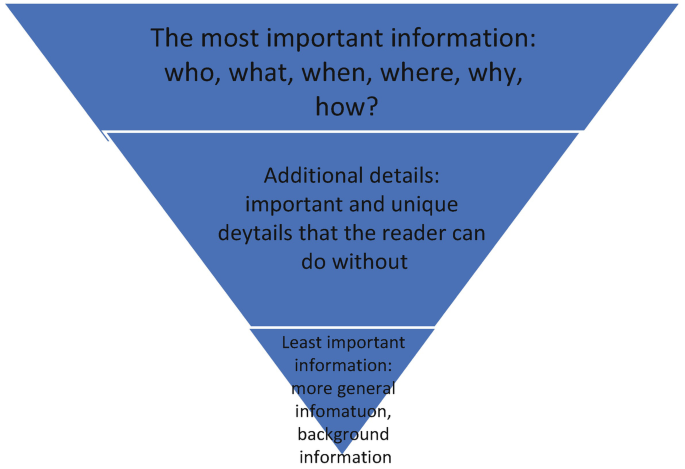

There are tools for transforming technical writing, that is the output from scientific research in easy, straightforward manner. They enable the presentation of the main points or key messages of a scientific research. These include the inverted pyramid and the message box. The inverted pyramid is a story-telling tool usually used in news reporting (Fig. 11.1 ). The inverted pyramid style presents information in a descending order of importance with the most crucial details presented first. This enables readers to get the most important information so that they can decide quickly whether to continue or stop reading the story (Scalan 2003 ).

The inverted pyramid

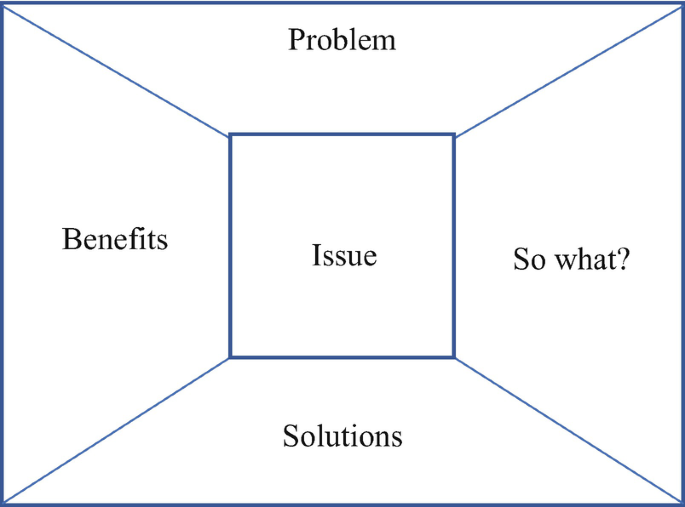

Similarly, the message box helps to explain what the research output is about and why it matters to the policy maker or the journalist (Fig. 11.2 ). It can be used to prepare for interviews with the media, frame a policy brief or press release, structure a presentation or an opinion piece. The message box can also serve as a tool to clarify the main issues of a research, the relevance of the research to the specific audience, and for condensing content of the research work into five to six sentences stating the problem, potential solutions and how the research relates to the concerns of the audience (Baron 2010 : 108). The resulting set of concise messages can be disseminated using channels appropriate for the end user, ranging from social media, to newspapers, to policy briefings and events.

The message box

These tools enable research outputs to be presented in a concise, easy to examine, understandable, user-friendly forms. They enable research outputs to be tailored and targeted to specific audiences with simple and clear messages focused on required information and recommendations. Usually, such presentations contain a link to the original journal article or source.

Research dissemination in contemporary times can be carried out in different ways, from long reports to policy briefs, message boxes, blog posts, social media posts, presentations and many more. Other means of disseminating research may take the form of engagement events by stakeholders to review the content and process of research. These include events in the form of round tables, town hall meetings, workshops, etc., involving exchanges and interactions among scholars, advocates and policy makers. They also include media interviews, writing blog features and data visualization, and social media content creation. However, determining the appropriate tool of communicating research is dependent on who the policy makers are and the kind of research being conducted. Communicating research work can adopt a multi-layered approach.

There is no scarcity of ideas how to engage the policy process. Several scholars have drawn ideas from their experiences in engagement with the policy process, others draw on the experiences of brokers or tease out ideas from policy theory and psychology. Engagements relates directly to the methodology of research. If research is directed at meeting broad policy objectives, then engagement with policy makers should be incorporated right from the inception of the research. Engagement facilitates the effective definition of questions to address the concerns of policy makers. When policy makers are engaged in the formulation of research questions, the research becomes more policy relevant. Evidence-based research is only relevant to policy making if it addresses the key policies at hand, is applicable to a local context and is constructed to meet policy needs. To enhance the possibility of a policy-engaged research, scientists must be open and willing to engage policy makers in the research process.

For social science research to be relevant for policy making, researchers and policy makers must understand their relevance and roles in the knowledge production process. Both parties need a shared understanding of the significance of these roles in policy making and implementation. Africa’s urgent problems require the expertise of policy-engaged researchers who would engage policy actors and politics. Engagement and effective communication of research would benefit society.

Efforts must be made by research communities to create engagement platforms between scientists and researchers. These platforms will ensure that policy makers are carried along at each step of the research process, thereby moving away from the common methods of engagement that reduces policy makers and other non-scientists to mere subjects of scientific research. A close interaction with policy makers on choice of method, design of instruments and major aspects of the research work stimulates an atmosphere of co-knowledge production between both worlds.

Although research communication involves distilling the key findings of high-quality research and presenting them in a format that non-scientists and policy makers can understand, interpret and use for decision making, the relevance of research will not be improved by mere speculations of policy needs and improvement in tools of communication. Effective communication involves developing relationships with stakeholders in the research process. The existence of good-quality research is not sufficient for evidence-informed policy making, a difficult task that requires interventions from both the demand and supply sides of policy-relevant research. Knowledge brokerage should be encouraged to facilitate the use of evidence in the policy processes of African governments by regional bodies like the African Union that has demonstrated capacity to promote policy diffusion across the continent.

Arnautu, Diana, and Christian Dagenais. 2021. Use and Effectiveness of Policy Briefs as a Knowledge Transfer Tool: A Scoping Review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8: 211. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00885-9 .

Article Google Scholar

Baron, Nancy. 2010. Escape from the Ivory Tower: A Guide to Making Your Science Matter . Washington, DC: Island Press.

Google Scholar

Cairney, P. 2016. The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cairney, Paul, and Richard Kwiatkowski. 2017. How to Communicate Effectively with Policymakers: Combine insights from Psychology and Policy Studies. Palgrave Communication 3 (7): 1–7.

Cairney, Paul, and Kathryn Oliver. 2020. How Should Academics Engage in Policymaking to Achieve Impact. Political Studies Review 18 (2): 228–244.

Dagenais, C., and V. Ridde. 2018. Policy Brief (PB) as a Knowledge Transfer Tool: To “make a splash”, Your PB Must First Be Read. Gaceta Sanitaria 32 (3): 203–205.

Egbetokun, A., A. Olofinyehun, Aderonke R. Ayo-Lawal, and M. Sanni. 2020. Doing Research in Nigeria Country Report Assessing Science Research System in a Global Perspective . National Centre for Technology Management and the Global Development Network.

Mkandawire, T. 1997. The Social Sciences in Africa: Breaking Local Barriers and Negotiating International Presence. African Studies Review 40 (2): 15–36.

Newman, Joshua, Andrian Cherney, and Brian W. Head. 2015. Do Policy Makers Use Academic Research Reexamining the Two Communities Theory of Research Utilisation. Public Administration Review 76 (1): 24–32.

Ojebode, Ayobami, Babatunde Raphael Ojebuyi, Oyewole Adekunle Oladapo, and Obasanjo Joseph Oyedele. 2018. Mono-Method Research Approach and Scholar–Policy Disengagement in Nigerian Communication Research, in 369–383. In The Palgrave Handbook of Media and Communication Research in Africa , ed. Bruce Mutsvairo. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Oliver, K., and P. Cairney. 2019. The Dos and Don’ts of Influencing Policy: A Systematic Review of Advice to Academics. Palgrave Communications 5 (21): 1–11.

Phoenix, Jessica H., Lucy G. Atkinson, and Hannah Baker. 2019. Creating and Communicating Social Research for Policymakers in Government. Palgrave Communication 5 (98): 1–11.

Pielke, Jr., R.A. 2007. The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scalan, C. 2003. Birth of the Inverted Pyramid: A Child of Technology, Commerce and History, Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2003/birth-of-the-inverted-pyramid-a-child-of-technology-commerce-and-history/ .

White, Howard. 2019. The Twenty-First Century Experimenting Society: The Four Waves of the Evidence Revolution. Palgrave Communication 5 (4): 1–7.

Wimberley, Ronald C., and Libby V. Morris. 2007. Communicating Research to Policymakers. American Sociologist 38: 288–293.

Wowk, Katerya, Larry Mckinney, Frank Muller-Karger, Russell Moll, Susan Avery, Elva Escobar-Briones, David Yoskowitz, and Richard McLaughliun. 2017. Evolving Academic Culture to Meet Societal Needs. Palgrave Communication 3 (35): 1–7.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Political Science, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

E. Remi Aiyede

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to E. Remi Aiyede .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

PASGR, Nairobi, Kenya

Beatrice Muganda

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Aiyede, E.R. (2023). From Research to Policy Action: Communicating Research for Public Policy Making. In: Aiyede, E.R., Muganda, B. (eds) Public Policy and Research in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99724-3_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99724-3_11

Published : 19 October 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-99723-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-99724-3

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

40 The Unique Methodology of Policy Research

Amitai Etzioni is a university professor and Professor of International Relations at The George Washington University. He served as a Senior Advisor at the Carter White House; taught at Columbia University, Harvard University, and University of California, Berkeley; and served as president of the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics (SASE). A study by Richard Posner ranked him among the top 100 American intellectuals. Etzioni is the author of many books, including Security First (2007), Foreign Policy: Thinking Outside the Box (2016), and Avoiding War with China (2017). His most recent book, Happiness is the Wrong Metric: A Liberal Communitarian Response to Populism, was published by Springer in January 2018.

- Published: 02 September 2009

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article provides a unique methodology of policy research, focusing on the various factors that differentiate policy research from basic research. It identifies malleability as a key variable of policy research, and this is defined as the amount of resources that would have to be expended to cause change in a given variable or variables. The scope of analysis/factors of policy research is shown to encompass all the major facets of the social phenomenon it is trying to deal with. Basic research, on the other hand, fragments the world into abstract and analytical slices, which are then studied individually. The last two differentiating factors of policy research and basic research, which are privacy and communication, are studied in the last two sections of the article.

Policy research requires a profoundly different methodology from that on which basic research relies, because policy research is always dedicated to changing the world while basic research seeks to understand it as it is. 1 The notion that if one merely understands the world better, then one will in turn know how to better it, is not supported by the evidence.

Typical policy goals are the reduction of poverty, curbing crime, cutting pollution, or changing some other condition (Mitchell and Mitchell 1969, 393) . Even those policies whose purpose is to maintain the status quo are promoting change—they aim to slow down or even reverse processes of deterioration, for instance that of natural monuments or historical documents. When no change is sought, say, when no one is concerned with changing the face of the moon, then there is no need for policy research in that particular area.

Moreover, although understanding the causes of a phenomenon, which successful basic research allows, is helpful in formulating policy, often a large amount of other information that is structured in a different manner best serves policy makers. 2 Policy researchers draw on a large amount of information that has no particular analytical base or theoretical background (of the kind that basic research provides). 3 In this sense medical science, which deals with changing bodies and minds, is a protypical policy science. It is estimated that about half of the information physicians employ has no basis in biology, chemistry, or any other science; but rather it is based on an accumulation of experience. 4 This knowledge is passed on from one medical cohort to another, as “these are the way things are done” and “they work.”

The same holds true for other policy sciences. For instance, criminologists who inform a local government that studies show that rehabilitation works more effectively in minimum security prisons than in maximum security prisons (a fact that can be explained by sociological theoretical concepts based on basic research) 5 know from long experience that they had better also alert the local authorities that such a reduction in security could potentially lead some inmates to escape and commit crimes in surrounding areas. Without being willing to accept such a “side effect” of the changed security policy, those governments who introduced it may well lose the next election and security in the prison will be returned to its previously high level. There is no particular sociological theoretical reason for escapes to rise when security is lowered. It is an observation based on common sense and experience; however it is hardly an observation that policy makers, let alone policy researchers should ignore. (They may though explore ways of coping with this “side effect,” for instance by either preparing the public ahead of time, introducing an alert system when inmates escape, or some other such measure.)

The examples just given seek to illustrate the difference between the information that basic research generates versus information that plays a major role in policy research. That is, there are important parts of the knowledge on which policy research draws that are based on distilled practice and are not derivable from basic research. Much of what follows deals with major differences in the ways that information and analysis are structured in sound policy research in contrast to the ways basic research is carried out.

One clarification before I can proceed: Policy research should not be confused with applied research. Applied research presumes that a policy decision has already been made and those responsible are now looking for the most efficient ways to implement it. Policy research helps to determine what the policy decision ought to be.

1. Malleability

A major difference between basic and policy research is that malleability is a key variable for the latter though not the former (Weimer and Vining 1989; 4) . Indeed for policy researchers it is arguably the single most important variable. Malleability for the purposes at hand ought to be defined as the amount of resources (including time, energy, and political capital) that would have to be expended to cause change in a given variable or variables. For policy research, malleability is a cardinal consideration because resources always fall short of what is required to implement given policy goals. Hence, to employ resources effectively requires determining the relative results to be generated from different patterns of allocation (Dunn 1981, 334– 402) . In contrast, basic research has no principled reason to favor some factors (or variables) over others. For basic research, it matters little if at all whether a condition under study can be modified and if it can how much it would cost. To illustrate, many sociological studies compare people by gender and age and although these variables may seem relevant, they are of limited value to policy research. Other variables used, such as the levels of income of various populations, the extent of education of various racial and ethnic groups, and the average size of cities, are somewhat more malleable but still not highly so. In contrast, perceptions are much more malleable.

One may say that basic research should reveal a preference for variables that have been less studied; however, such a consideration concerns the economics and politics of science rather than methodology. Because all scientific findings are conditional and temporary and often subject to profound revision and recasting, for basic researchers, retesting old findings can be just as valuable as covering new variables. In short, although in principle for basic research the study of all variables is legitimate, in a given period of time or amongst a given group of scientists, some may consider certain variables as more “interesting” or “promising” than others. In contrast, to reiterate, for policy research, malleability is the most important variable as it is directly related to its core reason for being: Promoting change.

Given the dominance of basic research methodology in the ways policy research is taught, it is not surprising to find that the question of which variables are more malleable than others is rarely studied in any systematic way. Due to the importance of this issue for policy research, some elaboration and illustrations are called for. Economic feasibility is a good case in point. Many policy researchers' final reports do not include any, not even crude estimates of the costs involved in what they are recommending. 6 Even less common is any consideration of the question of whether such changes can be made acceptable to elected representatives and the public at large; that is, political feasibility (Weimer and Vining 1989, 292– 324) . For instance, over the last decades several groups favored advancing their policy goals through constitutional amendments, ignoring the fact that these are extremely difficult to get passed.

In other cases, feasibility is treated as a secondary “applied” question to be studied later, after policy makers adopt the recommended policy. However, the issue runs much deeper than the assessments of feasibility of one kind or another. The challenge to policy research is to determine the relative resistance to change according to the different variables that are to be tackled. And this question must be tackled not on an ad hoc basis, but rather as a major part of systematic policy research. Moreover, if the variables involved are studied from this viewpoint, they themselves may be changed; that is, feasibility is enhanced rather than treated as a given.

Another example of the cardinal need to take malleability into account when conducting policy research concerns changing public attitudes. Policy makers often favor a “public education' campaign when they desire to affect people's beliefs and conduct. Policy makers tend to assume that it is feasible to change such predispositions through a way that might be called the Madison Avenue approach, which entails running a series of commercials (or public service announcements), mounting billboards, obtaining celebrity endorsements, and so on.

For example, the United States engaged in such a campaign in 2003 and 2004 to change the hearts and minds of “the Arab street” through what has also been termed “public diplomacy.” 7 The way this was carried out provides a vivid example of lack of attention to feasibility issues. American public diplomacy, developed by the State Department, included commercials, websites, and speakers programs that sought to “reconnect the world's billion Muslims with the United States the way McDonald's highlights its billion customers served” (Satloff 2003, 18) . It was based on the premiss that “blitzing Arab and Muslim countries with Britney Spears videos and Arabic‐language sitcoms will earn Washington millions of new Muslim sympathizers” (Satloff 2003, 18) . A study found that the results were “disastrous” (Satloff 2003, 18) . Some countries declined to air the messages and many Muslims who did see the material viewed it as blatant propaganda and offensive rather than compelling.

Actually, policy researchers bent on studying feasibility report that the Madison Avenue approach works only when large amounts of money are spent to shift people from one product to another when there are next to no differences between them (e.g. two brands of toothpaste) and when there is an inclination to use the product in the first place. However, when these methods are applied to changing attitudes about matters as different as condom use, 8 the United Nations, 9 electoral reform, and so forth, they are much less successful. Changing people's behavior—say to conserve energy, drive slower, cease smoking—is many hundreds of times more difficult. This is a major reason why totalitarian regimes, despite intensive public education campaigns, usually fail. The question of what is most feasible is determined by fiat by policy makers and their staffs rather than by studies that are reported to the policy makers by policy researchers. Hence decisions are often based on a fly‐by‐the‐seat‐ of‐your‐pants sense of what can be changed rather than on empirical evidence. 10 One of the few exceptions is studies of nation building in which several key policy researchers presented the reasons why such endeavors can be carried out at best only slowly while at the same time many policy makers claimed that it could be achieved in short order and at low cost. 11

In a preliminary stab at outlining the relative malleability of various factors, one may note that as a rule the laws of nature are not malleable; social relations, including patterns of asset distribution and power, are of limited malleability; and symbolic relations are highly malleable. Thus any policy‐making body that would seek to modify the level of gravity, for example, not for a particular situation (for instance a space travel simulator) but in general, will find this task at best extremely difficult to advance. In contrast, those who seek to change a flag, a national motto, the ways people refer to one another (e.g. Ms Instead of girl or broad), have a relatively easy time of doing so. Changes in the distribution of wealth among the classes or races—by public policy—are easier than changes involving the laws of nature, but more difficult than changing hearts and minds.

When policy researchers or policy makers ignore these observations and enact laws that seek grand and quick changes in power relations and economic patterns, the laws are soon reversed. A case in point is the developments that ensued when a policy researcher inserted into legislation the phrase “maximum feasible participation of the poor.” This Act was used to try to circumvent prevailing local power structures by directing federal funds to voluntary groups that included the poor on their advisory boards, which thus helped “empower the poor.” The law was nullified shortly thereafter. Similarly, when a constitutional amendment was enacted that banned the consumption of alcohol in the United States, it had some severely distorted effects on the American justice and law enforcement systems and did little actually to reduce the consumption of alcohol. It was also the only constitutional amendment ever to be repealed.

Among social changes, often legal and political reduction in inequality is relatively easier to come by than are socioeconomic changes along similar lines. Thus, African‐Americans and women gained de jure and de facto voting rights long before the differences in their income and representation in the seats of power moved closer to those of whites (in the case of African‐Americans) and of men (in the case of women). Nor have socioeconomic differences been reduced nearly as much as legal and political differences, although in both realms considerable inequalities remain. The same is true not just for the United States, but for other free societies and those that have been recently liberated.

In short, there are important differences in which dedication of resources, commitment of political capital, and public education are needed in order to bring about change. Sound policy research best makes the determination of which factors are more malleable than others, which is a major subject of study.

2. Scope of Analysis

Another particularly important difference between basic research and policy research methodology concerns the scope of factors that are best encompassed. Policy research at its best encompasses all the major facets of the social phenomenon it is trying to deal with. 12 In contrast, basic research proceeds by fragmenting the world into abstract, analytical slices which are then studied individually.