An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines

Jessie s. barrot.

College of Education, Arts and Sciences, National University, Manila, Philippines

Ian I. Llenares

Leo s. del rosario, associated data.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis that has shaken up its foundation. Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although many studies have investigated this area, limited information is available regarding the challenges and the specific strategies that students employ to overcome them. Thus, this study attempts to fill in the void. Using a mixed-methods approach, the findings revealed that the online learning challenges of college students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. The findings further revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic had the greatest impact on the quality of the learning experience and students’ mental health. In terms of strategies employed by students, the most frequently used were resource management and utilization, help-seeking, technical aptitude enhancement, time management, and learning environment control. Implications for classroom practice, policy-making, and future research are discussed.

Introduction

Since the 1990s, the world has seen significant changes in the landscape of education as a result of the ever-expanding influence of technology. One such development is the adoption of online learning across different learning contexts, whether formal or informal, academic and non-academic, and residential or remotely. We began to witness schools, teachers, and students increasingly adopt e-learning technologies that allow teachers to deliver instruction interactively, share resources seamlessly, and facilitate student collaboration and interaction (Elaish et al., 2019 ; Garcia et al., 2018 ). Although the efficacy of online learning has long been acknowledged by the education community (Barrot, 2020 , 2021 ; Cavanaugh et al., 2009 ; Kebritchi et al., 2017 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Wallace, 2003 ), evidence on the challenges in its implementation continues to build up (e.g., Boelens et al., 2017 ; Rasheed et al., 2020 ).

Recently, the education system has faced an unprecedented health crisis (i.e., COVID-19 pandemic) that has shaken up its foundation. Thus, various governments across the globe have launched a crisis response to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic on education. This response includes, but is not limited to, curriculum revisions, provision for technological resources and infrastructure, shifts in the academic calendar, and policies on instructional delivery and assessment. Inevitably, these developments compelled educational institutions to migrate to full online learning until face-to-face instruction is allowed. The current circumstance is unique as it could aggravate the challenges experienced during online learning due to restrictions in movement and health protocols (Gonzales et al., 2020 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Given today’s uncertainties, it is vital to gain a nuanced understanding of students’ online learning experience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, many studies have investigated this area with a focus on students’ mental health (Copeland et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ), home learning (Suryaman et al., 2020 ), self-regulation (Carter et al., 2020 ), virtual learning environment (Almaiah et al., 2020 ; Hew et al., 2020 ; Tang et al., 2020 ), and students’ overall learning experience (e.g., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ). There are two key differences that set the current study apart from the previous studies. First, it sheds light on the direct impact of the pandemic on the challenges that students experience in an online learning space. Second, the current study explores students’ coping strategies in this new learning setup. Addressing these areas would shed light on the extent of challenges that students experience in a full online learning space, particularly within the context of the pandemic. Meanwhile, our nuanced understanding of the strategies that students use to overcome their challenges would provide relevant information to school administrators and teachers to better support the online learning needs of students. This information would also be critical in revisiting the typology of strategies in an online learning environment.

Literature review

Education and the covid-19 pandemic.

In December 2019, an outbreak of a novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19, occurred in China and has spread rapidly across the globe within a few months. COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus that attacks the respiratory system (World Health Organization, 2020 ). As of January 2021, COVID-19 has infected 94 million people and has caused 2 million deaths in 191 countries and territories (John Hopkins University, 2021 ). This pandemic has created a massive disruption of the educational systems, affecting over 1.5 billion students. It has forced the government to cancel national examinations and the schools to temporarily close, cease face-to-face instruction, and strictly observe physical distancing. These events have sparked the digital transformation of higher education and challenged its ability to respond promptly and effectively. Schools adopted relevant technologies, prepared learning and staff resources, set systems and infrastructure, established new teaching protocols, and adjusted their curricula. However, the transition was smooth for some schools but rough for others, particularly those from developing countries with limited infrastructure (Pham & Nguyen, 2020 ; Simbulan, 2020 ).

Inevitably, schools and other learning spaces were forced to migrate to full online learning as the world continues the battle to control the vicious spread of the virus. Online learning refers to a learning environment that uses the Internet and other technological devices and tools for synchronous and asynchronous instructional delivery and management of academic programs (Usher & Barak, 2020 ; Huang, 2019 ). Synchronous online learning involves real-time interactions between the teacher and the students, while asynchronous online learning occurs without a strict schedule for different students (Singh & Thurman, 2019 ). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning has taken the status of interim remote teaching that serves as a response to an exigency. However, the migration to a new learning space has faced several major concerns relating to policy, pedagogy, logistics, socioeconomic factors, technology, and psychosocial factors (Donitsa-Schmidt & Ramot, 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Varea & González-Calvo, 2020 ). With reference to policies, government education agencies and schools scrambled to create fool-proof policies on governance structure, teacher management, and student management. Teachers, who were used to conventional teaching delivery, were also obliged to embrace technology despite their lack of technological literacy. To address this problem, online learning webinars and peer support systems were launched. On the part of the students, dropout rates increased due to economic, psychological, and academic reasons. Academically, although it is virtually possible for students to learn anything online, learning may perhaps be less than optimal, especially in courses that require face-to-face contact and direct interactions (Franchi, 2020 ).

Related studies

Recently, there has been an explosion of studies relating to the new normal in education. While many focused on national policies, professional development, and curriculum, others zeroed in on the specific learning experience of students during the pandemic. Among these are Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ) who examined the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health and their coping mechanisms. Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) reported that the pandemic adversely affected students’ behavioral and emotional functioning, particularly attention and externalizing problems (i.e., mood and wellness behavior), which were caused by isolation, economic/health effects, and uncertainties. In Fawaz et al.’s ( 2021 ) study, students raised their concerns on learning and evaluation methods, overwhelming task load, technical difficulties, and confinement. To cope with these problems, students actively dealt with the situation by seeking help from their teachers and relatives and engaging in recreational activities. These active-oriented coping mechanisms of students were aligned with Carter et al.’s ( 2020 ), who explored students’ self-regulation strategies.

In another study, Tang et al. ( 2020 ) examined the efficacy of different online teaching modes among engineering students. Using a questionnaire, the results revealed that students were dissatisfied with online learning in general, particularly in the aspect of communication and question-and-answer modes. Nonetheless, the combined model of online teaching with flipped classrooms improved students’ attention, academic performance, and course evaluation. A parallel study was undertaken by Hew et al. ( 2020 ), who transformed conventional flipped classrooms into fully online flipped classes through a cloud-based video conferencing app. Their findings suggested that these two types of learning environments were equally effective. They also offered ways on how to effectively adopt videoconferencing-assisted online flipped classrooms. Unlike the two studies, Suryaman et al. ( 2020 ) looked into how learning occurred at home during the pandemic. Their findings showed that students faced many obstacles in a home learning environment, such as lack of mastery of technology, high Internet cost, and limited interaction/socialization between and among students. In a related study, Kapasia et al. ( 2020 ) investigated how lockdown impacts students’ learning performance. Their findings revealed that the lockdown made significant disruptions in students’ learning experience. The students also reported some challenges that they faced during their online classes. These include anxiety, depression, poor Internet service, and unfavorable home learning environment, which were aggravated when students are marginalized and from remote areas. Contrary to Kapasia et al.’s ( 2020 ) findings, Gonzales et al. ( 2020 ) found that confinement of students during the pandemic had significant positive effects on their performance. They attributed these results to students’ continuous use of learning strategies which, in turn, improved their learning efficiency.

Finally, there are those that focused on students’ overall online learning experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. One such study was that of Singh et al. ( 2020 ), who examined students’ experience during the COVID-19 pandemic using a quantitative descriptive approach. Their findings indicated that students appreciated the use of online learning during the pandemic. However, half of them believed that the traditional classroom setting was more effective than the online learning platform. Methodologically, the researchers acknowledge that the quantitative nature of their study restricts a deeper interpretation of the findings. Unlike the above study, Khalil et al. ( 2020 ) qualitatively explored the efficacy of synchronized online learning in a medical school in Saudi Arabia. The results indicated that students generally perceive synchronous online learning positively, particularly in terms of time management and efficacy. However, they also reported technical (internet connectivity and poor utility of tools), methodological (content delivery), and behavioral (individual personality) challenges. Their findings also highlighted the failure of the online learning environment to address the needs of courses that require hands-on practice despite efforts to adopt virtual laboratories. In a parallel study, Adarkwah ( 2021 ) examined students’ online learning experience during the pandemic using a narrative inquiry approach. The findings indicated that Ghanaian students considered online learning as ineffective due to several challenges that they encountered. Among these were lack of social interaction among students, poor communication, lack of ICT resources, and poor learning outcomes. More recently, Day et al. ( 2021 ) examined the immediate impact of COVID-19 on students’ learning experience. Evidence from six institutions across three countries revealed some positive experiences and pre-existing inequities. Among the reported challenges are lack of appropriate devices, poor learning space at home, stress among students, and lack of fieldwork and access to laboratories.

Although there are few studies that report the online learning challenges that higher education students experience during the pandemic, limited information is available regarding the specific strategies that they use to overcome them. It is in this context that the current study was undertaken. This mixed-methods study investigates students’ online learning experience in higher education. Specifically, the following research questions are addressed: (1) What is the extent of challenges that students experience in an online learning environment? (2) How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact the online learning challenges that students experience? (3) What strategies did students use to overcome the challenges?

Conceptual framework

The typology of challenges examined in this study is largely based on Rasheed et al.’s ( 2020 ) review of students’ experience in an online learning environment. These challenges are grouped into five general clusters, namely self-regulation (SRC), technological literacy and competency (TLCC), student isolation (SIC), technological sufficiency (TSC), and technological complexity (TCC) challenges (Rasheed et al., 2020 , p. 5). SRC refers to a set of behavior by which students exercise control over their emotions, actions, and thoughts to achieve learning objectives. TLCC relates to a set of challenges about students’ ability to effectively use technology for learning purposes. SIC relates to the emotional discomfort that students experience as a result of being lonely and secluded from their peers. TSC refers to a set of challenges that students experience when accessing available online technologies for learning. Finally, there is TCC which involves challenges that students experience when exposed to complex and over-sufficient technologies for online learning.

To extend Rasheed et al. ( 2020 ) categories and to cover other potential challenges during online classes, two more clusters were added, namely learning resource challenges (LRC) and learning environment challenges (LEC) (Buehler, 2004 ; Recker et al., 2004 ; Seplaki et al., 2014 ; Xue et al., 2020 ). LRC refers to a set of challenges that students face relating to their use of library resources and instructional materials, whereas LEC is a set of challenges that students experience related to the condition of their learning space that shapes their learning experiences, beliefs, and attitudes. Since learning environment at home and learning resources available to students has been reported to significantly impact the quality of learning and their achievement of learning outcomes (Drane et al., 2020 ; Suryaman et al., 2020 ), the inclusion of LRC and LEC would allow us to capture other important challenges that students experience during the pandemic, particularly those from developing regions. This comprehensive list would provide us a clearer and detailed picture of students’ experiences when engaged in online learning in an emergency. Given the restrictions in mobility at macro and micro levels during the pandemic, it is also expected that such conditions would aggravate these challenges. Therefore, this paper intends to understand these challenges from students’ perspectives since they are the ones that are ultimately impacted when the issue is about the learning experience. We also seek to explore areas that provide inconclusive findings, thereby setting the path for future research.

Material and methods

The present study adopted a descriptive, mixed-methods approach to address the research questions. This approach allowed the researchers to collect complex data about students’ experience in an online learning environment and to clearly understand the phenomena from their perspective.

Participants

This study involved 200 (66 male and 134 female) students from a private higher education institution in the Philippines. These participants were Psychology, Physical Education, and Sports Management majors whose ages ranged from 17 to 25 ( x ̅ = 19.81; SD = 1.80). The students have been engaged in online learning for at least two terms in both synchronous and asynchronous modes. The students belonged to low- and middle-income groups but were equipped with the basic online learning equipment (e.g., computer, headset, speakers) and computer skills necessary for their participation in online classes. Table Table1 1 shows the primary and secondary platforms that students used during their online classes. The primary platforms are those that are formally adopted by teachers and students in a structured academic context, whereas the secondary platforms are those that are informally and spontaneously used by students and teachers for informal learning and to supplement instructional delivery. Note that almost all students identified MS Teams as their primary platform because it is the official learning management system of the university.

Participants’ Online Learning Platforms

Informed consent was sought from the participants prior to their involvement. Before students signed the informed consent form, they were oriented about the objectives of the study and the extent of their involvement. They were also briefed about the confidentiality of information, their anonymity, and their right to refuse to participate in the investigation. Finally, the participants were informed that they would incur no additional cost from their participation.

Instrument and data collection

The data were collected using a retrospective self-report questionnaire and a focused group discussion (FGD). A self-report questionnaire was considered appropriate because the indicators relate to affective responses and attitude (Araujo et al., 2017 ; Barrot, 2016 ; Spector, 1994 ). Although the participants may tell more than what they know or do in a self-report survey (Matsumoto, 1994 ), this challenge was addressed by explaining to them in detail each of the indicators and using methodological triangulation through FGD. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: (1) participant’s personal information section, (2) the background information on the online learning environment, (3) the rating scale section for the online learning challenges, (4) the open-ended section. The personal information section asked about the students’ personal information (name, school, course, age, and sex), while the background information section explored the online learning mode and platforms (primary and secondary) used in class, and students’ length of engagement in online classes. The rating scale section contained 37 items that relate to SRC (6 items), TLCC (10 items), SIC (4 items), TSC (6 items), TCC (3 items), LRC (4 items), and LEC (4 items). The Likert scale uses six scores (i.e., 5– to a very great extent , 4– to a great extent , 3– to a moderate extent , 2– to some extent , 1– to a small extent , and 0 –not at all/negligible ) assigned to each of the 37 items. Finally, the open-ended questions asked about other challenges that students experienced, the impact of the pandemic on the intensity or extent of the challenges they experienced, and the strategies that the participants employed to overcome the eight different types of challenges during online learning. Two experienced educators and researchers reviewed the questionnaire for clarity, accuracy, and content and face validity. The piloting of the instrument revealed that the tool had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

The FGD protocol contains two major sections: the participants’ background information and the main questions. The background information section asked about the students’ names, age, courses being taken, online learning mode used in class. The items in the main questions section covered questions relating to the students’ overall attitude toward online learning during the pandemic, the reasons for the scores they assigned to each of the challenges they experienced, the impact of the pandemic on students’ challenges, and the strategies they employed to address the challenges. The same experts identified above validated the FGD protocol.

Both the questionnaire and the FGD were conducted online via Google survey and MS Teams, respectively. It took approximately 20 min to complete the questionnaire, while the FGD lasted for about 90 min. Students were allowed to ask for clarification and additional explanations relating to the questionnaire content, FGD, and procedure. Online surveys and interview were used because of the ongoing lockdown in the city. For the purpose of triangulation, 20 (10 from Psychology and 10 from Physical Education and Sports Management) randomly selected students were invited to participate in the FGD. Two separate FGDs were scheduled for each group and were facilitated by researcher 2 and researcher 3, respectively. The interviewers ensured that the participants were comfortable and open to talk freely during the FGD to avoid social desirability biases (Bergen & Labonté, 2020 ). These were done by informing the participants that there are no wrong responses and that their identity and responses would be handled with the utmost confidentiality. With the permission of the participants, the FGD was recorded to ensure that all relevant information was accurately captured for transcription and analysis.

Data analysis

To address the research questions, we used both quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative analysis, we entered all the data into an excel spreadsheet. Then, we computed the mean scores ( M ) and standard deviations ( SD ) to determine the level of challenges experienced by students during online learning. The mean score for each descriptor was interpreted using the following scheme: 4.18 to 5.00 ( to a very great extent ), 3.34 to 4.17 ( to a great extent ), 2.51 to 3.33 ( to a moderate extent ), 1.68 to 2.50 ( to some extent ), 0.84 to 1.67 ( to a small extent ), and 0 to 0.83 ( not at all/negligible ). The equal interval was adopted because it produces more reliable and valid information than other types of scales (Cicchetti et al., 2006 ).

For the qualitative data, we analyzed the students’ responses in the open-ended questions and the transcribed FGD using the predetermined categories in the conceptual framework. Specifically, we used multilevel coding in classifying the codes from the transcripts (Birks & Mills, 2011 ). To do this, we identified the relevant codes from the responses of the participants and categorized these codes based on the similarities or relatedness of their properties and dimensions. Then, we performed a constant comparative and progressive analysis of cases to allow the initially identified subcategories to emerge and take shape. To ensure the reliability of the analysis, two coders independently analyzed the qualitative data. Both coders familiarize themselves with the purpose, research questions, research method, and codes and coding scheme of the study. They also had a calibration session and discussed ways on how they could consistently analyze the qualitative data. Percent of agreement between the two coders was 86 percent. Any disagreements in the analysis were discussed by the coders until an agreement was achieved.

This study investigated students’ online learning experience in higher education within the context of the pandemic. Specifically, we identified the extent of challenges that students experienced, how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their online learning experience, and the strategies that they used to confront these challenges.

The extent of students’ online learning challenges

Table Table2 2 presents the mean scores and SD for the extent of challenges that students’ experienced during online learning. Overall, the students experienced the identified challenges to a moderate extent ( x ̅ = 2.62, SD = 1.03) with scores ranging from x ̅ = 1.72 ( to some extent ) to x ̅ = 3.58 ( to a great extent ). More specifically, the greatest challenge that students experienced was related to the learning environment ( x ̅ = 3.49, SD = 1.27), particularly on distractions at home, limitations in completing the requirements for certain subjects, and difficulties in selecting the learning areas and study schedule. It is, however, found that the least challenge was on technological literacy and competency ( x ̅ = 2.10, SD = 1.13), particularly on knowledge and training in the use of technology, technological intimidation, and resistance to learning technologies. Other areas that students experienced the least challenge are Internet access under TSC and procrastination under SRC. Nonetheless, nearly half of the students’ responses per indicator rated the challenges they experienced as moderate (14 of the 37 indicators), particularly in TCC ( x ̅ = 2.51, SD = 1.31), SIC ( x ̅ = 2.77, SD = 1.34), and LRC ( x ̅ = 2.93, SD = 1.31).

The Extent of Students’ Challenges during the Interim Online Learning

Out of 200 students, 181 responded to the question about other challenges that they experienced. Most of their responses were already covered by the seven predetermined categories, except for 18 responses related to physical discomfort ( N = 5) and financial challenges ( N = 13). For instance, S108 commented that “when it comes to eyes and head, my eyes and head get ache if the session of class was 3 h straight in front of my gadget.” In the same vein, S194 reported that “the long exposure to gadgets especially laptop, resulting in body pain & headaches.” With reference to physical financial challenges, S66 noted that “not all the time I have money to load”, while S121 claimed that “I don't know until when are we going to afford budgeting our money instead of buying essentials.”

Impact of the pandemic on students’ online learning challenges

Another objective of this study was to identify how COVID-19 influenced the online learning challenges that students experienced. As shown in Table Table3, 3 , most of the students’ responses were related to teaching and learning quality ( N = 86) and anxiety and other mental health issues ( N = 52). Regarding the adverse impact on teaching and learning quality, most of the comments relate to the lack of preparation for the transition to online platforms (e.g., S23, S64), limited infrastructure (e.g., S13, S65, S99, S117), and poor Internet service (e.g., S3, S9, S17, S41, S65, S99). For the anxiety and mental health issues, most students reported that the anxiety, boredom, sadness, and isolation they experienced had adversely impacted the way they learn (e.g., S11, S130), completing their tasks/activities (e.g., S56, S156), and their motivation to continue studying (e.g., S122, S192). The data also reveal that COVID-19 aggravated the financial difficulties experienced by some students ( N = 16), consequently affecting their online learning experience. This financial impact mainly revolved around the lack of funding for their online classes as a result of their parents’ unemployment and the high cost of Internet data (e.g., S18, S113, S167). Meanwhile, few concerns were raised in relation to COVID-19’s impact on mobility ( N = 7) and face-to-face interactions ( N = 7). For instance, some commented that the lack of face-to-face interaction with her classmates had a detrimental effect on her learning (S46) and socialization skills (S36), while others reported that restrictions in mobility limited their learning experience (S78, S110). Very few comments were related to no effect ( N = 4) and positive effect ( N = 2). The above findings suggest the pandemic had additive adverse effects on students’ online learning experience.

Summary of students’ responses on the impact of COVID-19 on their online learning experience

Students’ strategies to overcome challenges in an online learning environment

The third objective of this study is to identify the strategies that students employed to overcome the different online learning challenges they experienced. Table Table4 4 presents that the most commonly used strategies used by students were resource management and utilization ( N = 181), help-seeking ( N = 155), technical aptitude enhancement ( N = 122), time management ( N = 98), and learning environment control ( N = 73). Not surprisingly, the top two strategies were also the most consistently used across different challenges. However, looking closely at each of the seven challenges, the frequency of using a particular strategy varies. For TSC and LRC, the most frequently used strategy was resource management and utilization ( N = 52, N = 89, respectively), whereas technical aptitude enhancement was the students’ most preferred strategy to address TLCC ( N = 77) and TCC ( N = 38). In the case of SRC, SIC, and LEC, the most frequently employed strategies were time management ( N = 71), psychological support ( N = 53), and learning environment control ( N = 60). In terms of consistency, help-seeking appears to be the most consistent across the different challenges in an online learning environment. Table Table4 4 further reveals that strategies used by students within a specific type of challenge vary.

Students’ Strategies to Overcome Online Learning Challenges

Discussion and conclusions

The current study explores the challenges that students experienced in an online learning environment and how the pandemic impacted their online learning experience. The findings revealed that the online learning challenges of students varied in terms of type and extent. Their greatest challenge was linked to their learning environment at home, while their least challenge was technological literacy and competency. Based on the students’ responses, their challenges were also found to be aggravated by the pandemic, especially in terms of quality of learning experience, mental health, finances, interaction, and mobility. With reference to previous studies (i.e., Adarkwah, 2021 ; Copeland et al., 2021 ; Day et al., 2021 ; Fawaz et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ; Khalil et al., 2020 ; Singh et al., 2020 ), the current study has complemented their findings on the pedagogical, logistical, socioeconomic, technological, and psychosocial online learning challenges that students experience within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, this study extended previous studies and our understanding of students’ online learning experience by identifying both the presence and extent of online learning challenges and by shedding light on the specific strategies they employed to overcome them.

Overall findings indicate that the extent of challenges and strategies varied from one student to another. Hence, they should be viewed as a consequence of interaction several many factors. Students’ responses suggest that their online learning challenges and strategies were mediated by the resources available to them, their interaction with their teachers and peers, and the school’s existing policies and guidelines for online learning. In the context of the pandemic, the imposed lockdowns and students’ socioeconomic condition aggravated the challenges that students experience.

While most studies revealed that technology use and competency were the most common challenges that students face during the online classes (see Rasheed et al., 2020 ), the case is a bit different in developing countries in times of pandemic. As the findings have shown, the learning environment is the greatest challenge that students needed to hurdle, particularly distractions at home (e.g., noise) and limitations in learning space and facilities. This data suggests that online learning challenges during the pandemic somehow vary from the typical challenges that students experience in a pre-pandemic online learning environment. One possible explanation for this result is that restriction in mobility may have aggravated this challenge since they could not go to the school or other learning spaces beyond the vicinity of their respective houses. As shown in the data, the imposition of lockdown restricted students’ learning experience (e.g., internship and laboratory experiments), limited their interaction with peers and teachers, caused depression, stress, and anxiety among students, and depleted the financial resources of those who belong to lower-income group. All of these adversely impacted students’ learning experience. This finding complemented earlier reports on the adverse impact of lockdown on students’ learning experience and the challenges posed by the home learning environment (e.g., Day et al., 2021 ; Kapasia et al., 2020 ). Nonetheless, further studies are required to validate the impact of restrictions on mobility on students’ online learning experience. The second reason that may explain the findings relates to students’ socioeconomic profile. Consistent with the findings of Adarkwah ( 2021 ) and Day et al. ( 2021 ), the current study reveals that the pandemic somehow exposed the many inequities in the educational systems within and across countries. In the case of a developing country, families from lower socioeconomic strata (as in the case of the students in this study) have limited learning space at home, access to quality Internet service, and online learning resources. This is the reason the learning environment and learning resources recorded the highest level of challenges. The socioeconomic profile of the students (i.e., low and middle-income group) is the same reason financial problems frequently surfaced from their responses. These students frequently linked the lack of financial resources to their access to the Internet, educational materials, and equipment necessary for online learning. Therefore, caution should be made when interpreting and extending the findings of this study to other contexts, particularly those from higher socioeconomic strata.

Among all the different online learning challenges, the students experienced the least challenge on technological literacy and competency. This is not surprising considering a plethora of research confirming Gen Z students’ (born since 1996) high technological and digital literacy (Barrot, 2018 ; Ng, 2012 ; Roblek et al., 2019 ). Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on students’ online learning experience, the findings reveal that teaching and learning quality and students’ mental health were the most affected. The anxiety that students experienced does not only come from the threats of COVID-19 itself but also from social and physical restrictions, unfamiliarity with new learning platforms, technical issues, and concerns about financial resources. These findings are consistent with that of Copeland et al. ( 2021 ) and Fawaz et al. ( 2021 ), who reported the adverse effects of the pandemic on students’ mental and emotional well-being. This data highlights the need to provide serious attention to the mediating effects of mental health, restrictions in mobility, and preparedness in delivering online learning.

Nonetheless, students employed a variety of strategies to overcome the challenges they faced during online learning. For instance, to address the home learning environment problems, students talked to their family (e.g., S12, S24), transferred to a quieter place (e.g., S7, S 26), studied at late night where all family members are sleeping already (e.g., S51), and consulted with their classmates and teachers (e.g., S3, S9, S156, S193). To overcome the challenges in learning resources, students used the Internet (e.g., S20, S27, S54, S91), joined Facebook groups that share free resources (e.g., S5), asked help from family members (e.g., S16), used resources available at home (e.g., S32), and consulted with the teachers (e.g., S124). The varying strategies of students confirmed earlier reports on the active orientation that students take when faced with academic- and non-academic-related issues in an online learning space (see Fawaz et al., 2021 ). The specific strategies that each student adopted may have been shaped by different factors surrounding him/her, such as available resources, student personality, family structure, relationship with peers and teacher, and aptitude. To expand this study, researchers may further investigate this area and explore how and why different factors shape their use of certain strategies.

Several implications can be drawn from the findings of this study. First, this study highlighted the importance of emergency response capability and readiness of higher education institutions in case another crisis strikes again. Critical areas that need utmost attention include (but not limited to) national and institutional policies, protocol and guidelines, technological infrastructure and resources, instructional delivery, staff development, potential inequalities, and collaboration among key stakeholders (i.e., parents, students, teachers, school leaders, industry, government education agencies, and community). Second, the findings have expanded our understanding of the different challenges that students might confront when we abruptly shift to full online learning, particularly those from countries with limited resources, poor Internet infrastructure, and poor home learning environment. Schools with a similar learning context could use the findings of this study in developing and enhancing their respective learning continuity plans to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic. This study would also provide students relevant information needed to reflect on the possible strategies that they may employ to overcome the challenges. These are critical information necessary for effective policymaking, decision-making, and future implementation of online learning. Third, teachers may find the results useful in providing proper interventions to address the reported challenges, particularly in the most critical areas. Finally, the findings provided us a nuanced understanding of the interdependence of learning tools, learners, and learning outcomes within an online learning environment; thus, giving us a multiperspective of hows and whys of a successful migration to full online learning.

Some limitations in this study need to be acknowledged and addressed in future studies. One limitation of this study is that it exclusively focused on students’ perspectives. Future studies may widen the sample by including all other actors taking part in the teaching–learning process. Researchers may go deeper by investigating teachers’ views and experience to have a complete view of the situation and how different elements interact between them or affect the others. Future studies may also identify some teacher-related factors that could influence students’ online learning experience. In the case of students, their age, sex, and degree programs may be examined in relation to the specific challenges and strategies they experience. Although the study involved a relatively large sample size, the participants were limited to college students from a Philippine university. To increase the robustness of the findings, future studies may expand the learning context to K-12 and several higher education institutions from different geographical regions. As a final note, this pandemic has undoubtedly reshaped and pushed the education system to its limits. However, this unprecedented event is the same thing that will make the education system stronger and survive future threats.

Authors’ contributions

Jessie Barrot led the planning, prepared the instrument, wrote the report, and processed and analyzed data. Ian Llenares participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing. Leo del Rosario participated in the planning, fielded the instrument, processed and analyzed data, reviewed the instrument, and contributed to report writing.

No funding was received in the conduct of this study.

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

The study has undergone appropriate ethics protocol.

Informed consent was sought from the participants.

Authors consented the publication. Participants consented to publication as long as confidentiality is observed.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Adarkwah MA. “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post Covid-19. Education and Information Technologies. 2021; 26 (2):1665–1685. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10331-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Almaiah MA, Al-Khasawneh A, Althunibat A. Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies. 2020; 25 :5261–5280. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10219-y. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Araujo T, Wonneberger A, Neijens P, de Vreese C. How much time do you spend online? Understanding and improving the accuracy of self-reported measures of Internet use. Communication Methods and Measures. 2017; 11 (3):173–190. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2017.1317337. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrot, J. S. (2016). Using Facebook-based e-portfolio in ESL writing classrooms: Impact and challenges. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29 (3), 286–301.

- Barrot, J. S. (2018). Facebook as a learning environment for language teaching and learning: A critical analysis of the literature from 2010 to 2017. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34 (6), 863–875.

- Barrot, J. S. (2020). Scientific mapping of social media in education: A decade of exponential growth. Journal of Educational Computing Research . 10.1177/0735633120972010.

- Barrot, J. S. (2021). Social media as a language learning environment: A systematic review of the literature (2008–2019). Computer Assisted Language Learning . 10.1080/09588221.2021.1883673.

- Bergen N, Labonté R. “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2020; 30 (5):783–792. doi: 10.1177/1049732319889354. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

- Boelens R, De Wever B, Voet M. Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review. 2017; 22 :1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2017.06.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buehler MA. Where is the library in course management software? Journal of Library Administration. 2004; 41 (1–2):75–84. doi: 10.1300/J111v41n01_07. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter RA, Jr, Rice M, Yang S, Jackson HA. Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: Strategies for remote learning. Information and Learning Sciences. 2020; 121 (5/6):321–329. doi: 10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0114. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cavanaugh CS, Barbour MK, Clark T. Research and practice in K-12 online learning: A review of open access literature. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2009; 10 (1):1–22. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v10i1.607. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cicchetti D, Bronen R, Spencer S, Haut S, Berg A, Oliver P, Tyrer P. Rating scales, scales of measurement, issues of reliability: Resolving some critical issues for clinicians and researchers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006; 194 (8):557–564. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000230392.83607.c5. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Copeland WE, McGinnis E, Bai Y, Adams Z, Nardone H, Devadanam V, Hudziak JJ. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021; 60 (1):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Day T, Chang ICC, Chung CKL, Doolittle WE, Housel J, McDaniel PN. The immediate impact of COVID-19 on postsecondary teaching and learning. The Professional Geographer. 2021; 73 (1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2020.1823864. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donitsa-Schmidt S, Ramot R. Opportunities and challenges: Teacher education in Israel in the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Teaching. 2020; 46 (4):586–595. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1799708. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drane, C., Vernon, L., & O’Shea, S. (2020). The impact of ‘learning at home’on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature Review Prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. Curtin University, Australia.

- Elaish M, Shuib L, Ghani N, Yadegaridehkordi E. Mobile English language learning (MELL): A literature review. Educational Review. 2019; 71 (2):257–276. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2017.1382445. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fawaz, M., Al Nakhal, M., & Itani, M. (2021). COVID-19 quarantine stressors and management among Lebanese students: A qualitative study. Current Psychology , 1–8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Franchi T. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: A student’s perspective. Anatomical Sciences Education. 2020; 13 (3):312–315. doi: 10.1002/ase.1966. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia R, Falkner K, Vivian R. Systematic literature review: Self-regulated learning strategies using e-learning tools for computer science. Computers & Education. 2018; 123 :150–163. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.006. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gonzalez T, De La Rubia MA, Hincz KP, Comas-Lopez M, Subirats L, Fort S, Sacha GM. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15 (10):e0239490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239490. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hew KF, Jia C, Gonda DE, Bai S. Transitioning to the “new normal” of learning in unpredictable times: Pedagogical practices and learning performance in fully online flipped classrooms. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 2020; 17 (1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00234-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang Q. Comparing teacher’s roles of F2F learning and online learning in a blended English course. Computer Assisted Language Learning. 2019; 32 (3):190–209. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2018.1540434. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- John Hopkins University. (2021). Global map . https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- Kapasia N, Paul P, Roy A, Saha J, Zaveri A, Mallick R, Chouhan P. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal. India. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020; 116 :105194. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kebritchi M, Lipschuetz A, Santiague L. Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 2017; 46 (1):4–29. doi: 10.1177/0047239516661713. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, Almisnid K, Aldamegh M, Al-Nafeesah A, Al-Wutayd O. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Medical Education. 2020; 20 (1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Matsumoto K. Introspection, verbal reports and second language learning strategy research. Canadian Modern Language Review. 1994; 50 (2):363–386. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.50.2.363. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng W. Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education. 2012; 59 (3):1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pham T, Nguyen H. COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities for Vietnamese higher education. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and beyond. 2020; 8 :22–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rasheed RA, Kamsin A, Abdullah NA. Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education. 2020; 144 :103701. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103701. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Recker MM, Dorward J, Nelson LM. Discovery and use of online learning resources: Case study findings. Educational Technology & Society. 2004; 7 (2):93–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roblek V, Mesko M, Dimovski V, Peterlin J. Smart technologies as social innovation and complex social issues of the Z generation. Kybernetes. 2019; 48 (1):91–107. doi: 10.1108/K-09-2017-0356. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seplaki CL, Agree EM, Weiss CO, Szanton SL, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP. Assistive devices in context: Cross-sectional association between challenges in the home environment and use of assistive devices for mobility. The Gerontologist. 2014; 54 (4):651–660. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt030. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Simbulan N. COVID-19 and its impact on higher education in the Philippines. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and beyond. 2020; 8 :15–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh K, Srivastav S, Bhardwaj A, Dixit A, Misra S. Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single institution experience. Indian Pediatrics. 2020; 57 (7):678–679. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1899-2. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh V, Thurman A. How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988–2018) American Journal of Distance Education. 2019; 33 (4):289–306. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2019.1663082. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spector P. Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1994; 15 (5):385–392. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150503. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suryaman M, Cahyono Y, Muliansyah D, Bustani O, Suryani P, Fahlevi M, Munthe AP. COVID-19 pandemic and home online learning system: Does it affect the quality of pharmacy school learning? Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy. 2020; 11 :524–530. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tallent-Runnels MK, Thomas JA, Lan WY, Cooper S, Ahern TC, Shaw SM, Liu X. Teaching courses online: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research. 2006; 76 (1):93–135. doi: 10.3102/00346543076001093. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tang, T., Abuhmaid, A. M., Olaimat, M., Oudat, D. M., Aldhaeebi, M., & Bamanger, E. (2020). Efficiency of flipped classroom with online-based teaching under COVID-19. Interactive Learning Environments , 1–12.

- Usher M, Barak M. Team diversity as a predictor of innovation in team projects of face-to-face and online learners. Computers & Education. 2020; 144 :103702. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103702. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Varea, V., & González-Calvo, G. (2020). Touchless classes and absent bodies: Teaching physical education in times of Covid-19. Sport, Education and Society , 1–15.

- Wallace RM. Online learning in higher education: A review of research on interactions among teachers and students. Education, Communication & Information. 2003; 3 (2):241–280. doi: 10.1080/14636310303143. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus . https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1

- Xue, E., Li, J., Li, T., & Shang, W. (2020). China’s education response to COVID-19: A perspective of policy analysis. Educational Philosophy and Theory , 1–13.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Online classes and learning in the Philippines during the Covid-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic brought great disruption to all aspects of life specifically on how classes were conducted both in an offline and online modes. The sudden shift to purely online method of teaching and learning was a result of the lockdowns that were imposed by the Philippine government. While some institutions have dealt with the situation by shutting down operations, others continued to deliver instructions and lessons using the Internet and different applications that support online learning. The continuation of classes online had caused several issues from students and teachers ranging from lack of technology to mental health matters. Finally, recommendations were asserted to mitigate the presented concerns and improve the delivery of the necessary quality education to the intended learners.

Related Papers

RD Deo , Abraham Deogracias

Knowing that education has been inaccessible and ineffective to some students in the Philippines, it is crucial to know the efficacy and success of the new learning setup during this time of the pandemic to assess if these new modalities are beneficial to the students or not. This paper reviewed and studied the various perceptions and lived experiences of selected students in a private university in Manila regarding online classes amidst the pandemic. Using a phenomenological approach, the researchers gathered data by interviewing 15 students who are attending online classes. Findings and results were drawn on the themes created by the researchers. It can be seen that majority of the students find online classes ineffective and only cater the privileged. Furthermore, lessons and discussions are difficult to digest using the current mode of learning. These findings signify a need to improve the mode of learning in order to provide a quality and effective education to students despite the current crisis faced by the country. Keywords: distance learning, online learning, online classes

Walailak Journal of Social Science

Asia Social Issues

Understanding students' experiences towards online learning can help in devising innovative pedagogical approaches and creating effective online learning spaces. This study aimed to solicit the perception of 80 undergraduate students in one of the leading private institutions in the Philippines towards the compulsory shift from a blended to fully online learning modality amidst the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The study used a descriptive research design involving online surveys which contained Likert scale items and open-ended questions assessing one's capacity for and the challenges to online learning, as well as the proposed recommendations for enhancing the overall online class experience. Descriptive statistics was used to group data across different subsets. Likewise, a content analysis of qualitative variables of the actual experiences of online classes using the school's learning management system was prepared. Results indicate four self-perceived challenges in online learning: technological and infrastructural difficulties, individual readiness, instructional struggles, and domestic barriers. The study recommends re-evaluation and modification of current online learning guidelines to address the aforesaid challenges and build a genuinely resilient model for technology-driven and care-centered education based on student recommendations and challenges experienced.

Universal Journal of Educational Research

Horizon Research Publishing(HRPUB) Kevin Nelson

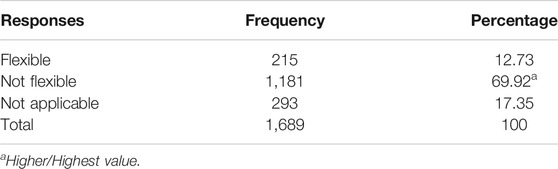

In light of the learning continuity challenges experienced by educational institutions in the Philippines amidst the onset of the Covid-19 health crisis, the research serves to assess the conduct of emergency response online classes in a Philippine city schools division. It utilized a researcher-made instrument which assessed the profile of the respondents; their level of competence and confidence in conducting and supervising online classes; the level of preparedness of the schools; the levels of difficulty in lesson delivery and instructional supervision; and perceived advantages, disadvantages, and suggestions for improvement of online classes. Through purposive sampling, the respondents comprised 91 teachers and 24 instructional supervisors from 18 schools. Results of the study revealed that teachers and instructional supervisors needed experience and training to be able to efficiently and effectively perform their tasks in online classes; and that there were students and teachers who were not able to regularly participate in online classes due to lack of resources. Respondents also said that online classes were flexible in terms of schedule and choice of strategies, able to ensure learning continuity, were convenient, and efficient in terms of saving time, money, and effort. However, they also said that online classes had decreased participation rate, were ineffective, and had limited interaction and socialization. Conduct of training/orientation and regular practice on online classes, and ensuring needed infrastructure and resources are in place and available, respectively; as well as further research on the topic were suggested.

Education and Information Technologies

Leo del Rosario

Jurnal Prima Edukasia

rimba hamid

This study aims to obtain an in-depth overview of (1) the distribution of students at the Department of PGSD FKIP UHO based on domicile in implementing online learning during the Covid-19 period; (2) infrastructure support for the effectiveness of online learning in the Covid-19 period; and (3) students' perceptions about online learning conducted by lecturers of the Department of PGSD FKIP UHO during Covid-19. This research was conducted in May 2020, which was included in the descriptive study, by conducting a survey of students at the Department of PGSD FKIP UHO, which was spread across all districts/cities in Southeast Sulawesi and other regions. Data collection techniques using open and closed questionnaires, with the research subjects of the class of 2017, 2018 and 2019 students who filled 316 questionnaires online from the link sent. Data obtained from students in the form of qualitative and quantitative raw data collected online and converted in Excel format. The data was...

Arun Antonyraj

The Corona virus (Covid-19) pandemic out broken at the late 2019 was reported as a cluster of cases in December at Wuhan, China by The World Health Organization. The pandemic has been lasting about a year claimed more than 55 million cases and 1.5 million of death globally. This has brought into drastic changes in the normal lifestyle of people worldwide, especially into the routine of education field creating many changes into their policies and practices. The Pandemic has disrupted the cl assroom education system and paved a new normal way to online education system. The Information Communication Technologies have provided a rescue hand to bring back the student and teacher communication through online classes to persist the education. The study involves in analyzing the new normal practices at education sector in providing their classes online and the precautionary measures in enhancing the effectiveness of online classes.

Kimkong Heng

Afraseyab khattak

Afraseyab Khattak , sayyed Shah

Background: The spread of COVID-19 triggered a range of health sector responses. As a response to minimize the spread,e-learning schemes are employed in many countries including Pakistan. It is playing an important role during this outbreak; however, there are technical, educational, financial, infrastructural, and socioeconomic barriers that exist in the developing countries like Pakistan. These barriers have huge impact on the e-learning process in the country on both students and teachers. Purpose: This study tends to investigate the impact of online classes on students learning process and teachers fulfilling their responsibilities at university level, particularly during the lockdown of the third wave of COVID-19. Methods: For the data collection, a descriptive cross-sectional online and self-administrated survey has been conducted. The study sample has been made from eight different private and public sector universities of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Results: The results of the study have presented interesting facts which are not common is developed countries. Around 47.5% of teachers have reported their anxiousness about their online class cause of electrical problems and also 30.5% of the Internet connectivity issues. More than half of the students i.e., 58.5% have faced disturbance due to power shortage (load shedding) and around 56.7% have highlighted the Internet issue including availability and signal strength.The study has also shown that only 59% of the students have fully access their online

Journal ijmr.net.in(UGC Approved)

Corona virus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by newly discovered corona virus. It is slowing down the world economy. Each and every sector whether working or non-working has been totally affected by it. Educational issues have grown up to a very large extent due to the pandemic. Educational issues are one of major issues among those topics which need to be taken into consideration now days. Internet has changed the things that how we communicate nowadays, Online teaching during this pandemic Covid-19 has proved to be another perk of technology. Teachers are efficiently taking online classes but the questions arise the consideration and challenges that students and teachers are facing. Study is to throw light on some of the major concerns regarding it.

Shivani Sawhney

The lockdown has compelled many educational institutions to cancel their classes, examinations etc. and to choose the online modes. In this regard, E-learning tools have played decisive role during this pandemic, helping educational institute to facilitate students learning. The use of suitable and relevant pedagogy for online education may depend on the expertise and exposure to information technology for both educators and the students. The present study assesses the challenges faced by students and its impact on their studies due to online classes during Covid-19. A total of 140 respondents were participated in survey that was pursuing their graduation. The research instrument used for survey was Google form and link was created and sends to the students by WhatsApp mode. The results reveal that the low connectivity issue was the one of the hurdle students were facing. Results also indicate that online learning has reduced the quality of education.

RELATED PAPERS

International Journal of Engineering & Technology

Jeevana sujitha

Advances and Applications in Bioinformatics and Chemistry

Daniel Kessler

Josandra Melo

kate semple

Wildlife Society Bulletin

Dale Rollins

Adel D M Kotb

Journal of History School

Interseções: Revista de Estudos Interdisciplinares

Janine Targino

International Journal of Occupational Safety and Health

Sivabalan Kaniapan

Microbial Pathogenesis

sachin sharma

Nipon Boonkumkrong

andhika firdauz27

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics

Maryam Shahbazi

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

Duygu Toplu

Bojan Mohar

Journal of Physics: Conference Series

Christine Fountzoula

isaias Silva

British Journal of Haematology

050 NATCHAYA TIPMONTREE

Nature Communications

Gene Yogodzinski

Realidad: Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades

Mario Lagomarsino Barrientos

Annals of medical research

Perçin Karakol

Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology

Ann Acheson

Industrial Robot: An International Journal

Gunnar Bolmsjö

Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology

Quang Nguyễn

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, teaching and learning continuity amid and beyond the pandemic.

- Office of the University President, Palompon - Office of the Vice-President for Academic Affairs, Garcia-Center for Research and Development, Olvido - Office of the Board and University Secretary, Cebu, Philippines

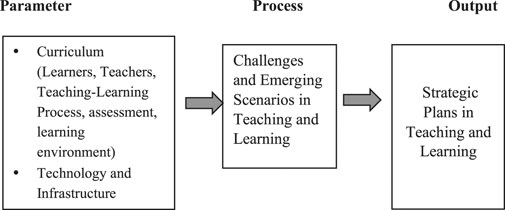

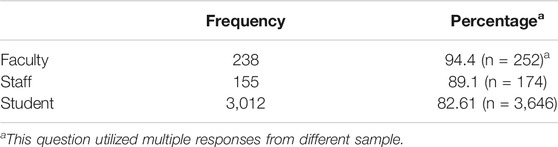

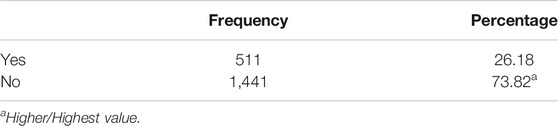

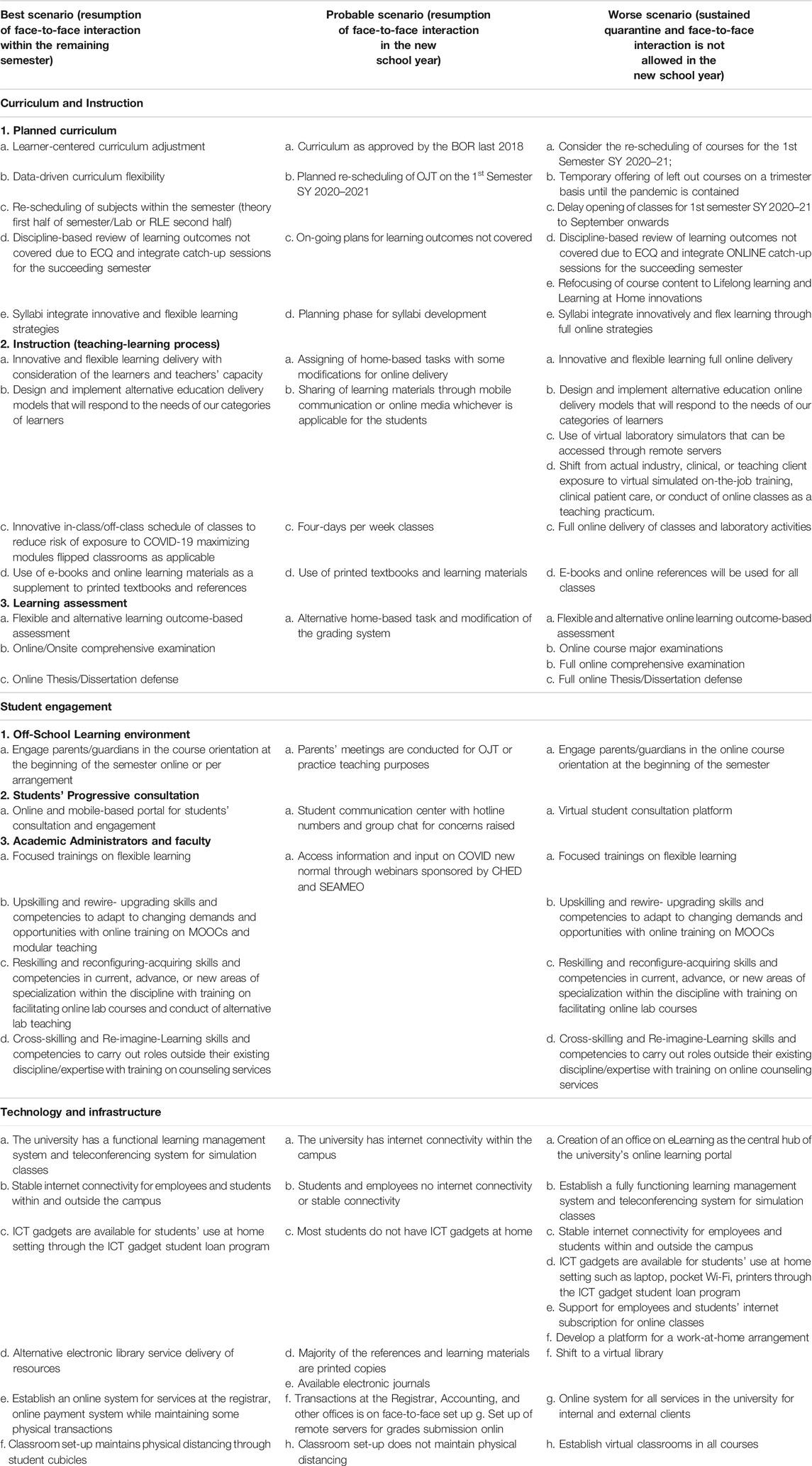

The study explored the challenges and issues in teaching and learning continuity of public higher education in the Philippines as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study employed the exploratory mixed-method triangulation design and analyzed the data gathered from 3, 989 respondents composed of students and faculty members. It was found out that during school lockdowns, the teachers made adjustments in teaching and learning designs guided by the policies implemented by the institution. Most of the students had difficulty complying with the learning activities and requirements due to limited or no internet connectivity. Emerging themes were identified from the qualitative responses to include the trajectory for flexible learning delivery, the role of technology, the teaching and learning environment, and the prioritization of safety and security. Scenario analysis provided the contextual basis for strategic actions amid and beyond the pandemic. To ensure teaching and learning continuity, it is concluded that higher education institutions have to migrate to flexible teaching and learning modality recalibrate the curriculum, capacitate the faculty, upgrade the infrastructure, implement a strategic plan and assess all aspects of the plan.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented challenges economically, socially, and politically across the globe. More than just a health crisis, it has resulted in an educational crisis. During lockdowns and quarantines, 87% of the world’s student population was affected and 1.52 billion learners were out of school and related educational institutions ( UNESCO Learning Portal, 2020 ). The suddenness, uncertainty, and volatility of COVID-19 left the education system in a rush of addressing the changing learning landscape.

The disruption of COVID-19 in the educational system is of great magnitude that universities have to cope with at the soonest possible time. The call is for higher education institutions to develop a resilient learning system using evidence-based and needs-based information so that responsive and proactive measures can be instituted. Coping with the effects of COVID-19 in higher education institutions demands a variety of perspectives among stakeholders. Consultation needs to include the administration who supports the teaching-learning processes, the students who are the core of the system, the faculty members or teachers who perform various academic roles, parents, and guardians who share the responsibility of learning continuity, the community, and the external partners who contribute to the completion of the educational requirements of the students. These complicated identities show that an institution of higher learning has a large number of stakeholders ( Illanes et al., 2020 ; Smalley, 2020 ). In the context of the pandemic, universities have to start understanding and identifying medium-term and long-term implications of this phenomenon on teaching, learning, student experience, infrastructure, operation, and staff. Scenario analysis and understanding of the context of each university are necessary to the current challenges they are confronted with (Frankki et al., 2020). Universities have to be resilient in times of crisis. Resiliency in the educational system is the ability to overcome challenges of all kinds–trauma, tragedy, crises, and bounce back stronger, wiser, and more personally powerful ( Henderson, 2012 ). The educational system must prepare to develop plans to move forward and address the new normal after the crisis. To be resilient, higher education needs to address teaching and learning continuity amid and beyond the pandemic.

Teaching and Learning in Times of Crisis

The teaching and learning process assumes a different shape in times of crisis. When disasters and crises (man-made and natural) occur, schools and colleges need to be resilient and find new ways to continue the teaching–learning activities ( Chang-Richards et al., 2013 ). One emerging reality as a result of the world health crisis is the migration to online learning modalities to mitigate the risk of face-to-face interaction. Universities are forced to migrate from face-to-face delivery to online modality as a result of the pandemic. In the Philippines, most universities including Cebu Normal University have resorted to online learning during school lockdowns. However, this sudden shift has resulted in problems especially for learners without access to technology. When online learning modality is used as a result of the pandemic, the gap between those who have connectivity and those without widened. The continuing academic engagement has been a challenge for teachers and students due to access and internet connectivity.

Considering the limitation on connectivity, the concept of flexible learning emerged as an option for online learning especially in higher institutions in the Philippines. Flexible learning focuses on giving students choice in the pace, place, and mode of students’ learning which can be promoted through appropriate pedagogical practice ( Gordon, 2014 ). The learners are provided with the option on how he/she will continue with his/her studies, where and when he/she can proceed, and in what ways can the learners comply with the requirements and show evidences of learning outcomes. Flexible learning and teaching span a multitude of approaches that can meet the varied needs of diverse learners. These include “independence in terms of time and location of learning, and the availability of some degree of choice in the curriculum (including content, learning strategies, and assessment) and the use of contemporary information and communication technologies to support a range of learning strategies” ( Alexander, 2010 ).

One key component in migrating to flexible modality is to consider how flexibility is integrated into the key dimensions of teaching and learning. One major consideration is leveraging flexibility in the curriculum. The curriculum encompasses the recommended, written, taught or implemented, assessed, and learned curriculum ( Glatthorn, 2000 ). Curriculum pertains to the curricular programs, the teaching, and learning design, learning resources as assessment, and teaching and learning environment. Adjustment on the types of assessment measures is a major factor amid the pandemic. There is a need to limit requirements and focus on the major essential projects that measure the enduring learning outcomes like case scenarios, problem-based activities, and capstone projects. Authentic assessments have to be intensified to ensure that competencies are acquired by the learners. In the process of modifying the curriculum amid the pandemic, it must be remembered that initiatives and evaluation tasks must be anchored on what the learners need including their safety and well-being.

Curriculum recalibration is not just about the content of what is to be learned and taught but how it is to be learned, taught, and assessed in the context of the challenges brought about by the pandemic. A flexible curriculum design should be learner-centered; take into account the demographic profile and circumstances of learners–such as access to technology, technological literacies, different learning styles and capabilities, different knowledge backgrounds and experiences - and ensure varied and flexible forms of assessment ( Ryan and Tilbury, 2013 ; Gachago et al., 2018 ). The challenge during the pandemic is how to create a balance between relevant basic competencies for the students to acquire and the teachers’ desire to achieve the intended outcomes of the curriculum.

The learners’ engagement in the teaching-learning process needs to be taken into consideration in the context of flexibility. This is about the design and development of productive learning experiences so that each learner is exposed to most of the learning opportunities. Considering that face-to-face modality is not feasible during the pandemic, teachers may consider flexible distant learning options like correspondence teaching, module-based learning, project-based, and television broadcast. For learners with internet connectivity, computer-assisted instruction, synchronous online learning, asynchronous online learning, collaborative e-learning may be considered.

The Role of Technology in Learning Continuity

Technology provides innovative and resilient solutions in times of crisis to combat disruption and helps people to communicate and even work virtually without the need for face-to-face interaction. This leads to many system changes in organizations as they adopt new technology for interacting and working ( Mark and Semaan, 2008 ). However, technological challenges like internet connectivity especially for places without signals can be the greatest obstacle in teaching and learning continuity especially for academic institutions who have opted for online learning as a teaching modality. Thus, the alternative models of learning during the pandemic should be supported by a well-designed technical and logistical implementation plan ( Edizon, 2020 ).

The nationwide closure of educational institutions in an attempt to contain the spread of the virus has impacted 90% of the world’s student population ( UNESCO, 2020 ). It is the intent of this study to look into the challenges in teaching and learning continuity amidst the pandemic. The need to mitigate the immediate impact of school closures on the continuity of learning among learners from their perspectives is an important consideration ( Edizon, 2020 ; Hijazi, 2020 ; UNESCO, 2020 ). Moreover, the teachers' perspectives are equally as important as the learners since they are the ones providing and sustaining the learning process. Teachers should effectively approach these current challenges to facilitate learning among learners, learner differentiation, and learner-centeredness and be ready to assume the role of facilitators on the remote learning platforms ( Chi-Kin Lee, 2020 ; Edizon, 2020 ; Hijazi, 2020 ).

Statement of Objective

This study explores the issues and challenges in teaching and learning amid the pandemic from the lenses of the faculty members and students of a public university in the Philippines as the basis for the development of strategic actions for teaching and learning continuity. Specifically, this study aimed to:

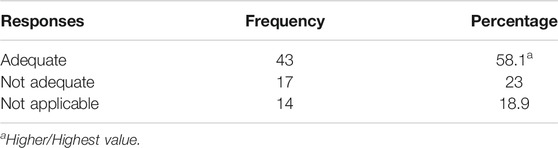

a.1. Preferred flexible learning activities.

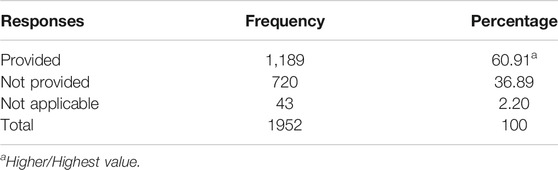

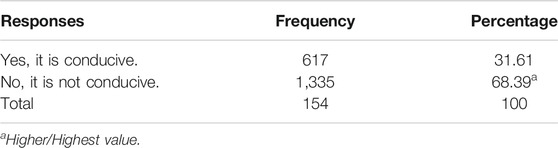

a.2. Problems completing Requirements due to ICT Limitation

a.3. Provision of alternative/additional requirement.

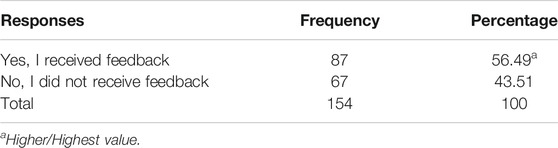

a.4. Receipt of learning feedback.

a.5. Learning environment.

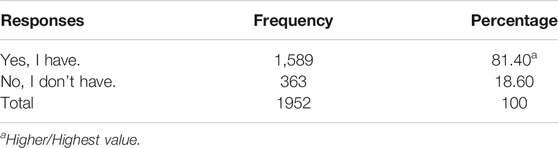

Objective 2: determine the profile of faculty and students in terms of online capacity as categorized into:

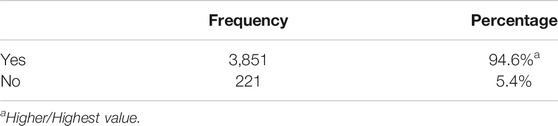

b.1. Access to Information Technology.

b.2. Access to Internet/Wi-fi.

b.3. Stability of internet connection.

Objective 3: develop emerging themes from the experiences and challenges of teaching and learning amidst the pandemic.

Methodology

The design used in the study is an exploratory mixed-method triangulation design. It was utilized to obtain different information but complementary data on a common topic or intent of the study, bringing together the differing strengths non-overlapping weaknesses of quantitative methods with those of qualitative methods ( Creswell, 2006 ). The use of the mixed method provided the data used as a basis for the analysis and planning perspective of the study.

This study was conducted in the context of a state university funded by the Philippine government whose location was once identified as having one of the highest COVID19 cases in the country. With this incidence, the sudden suspension of classes and the immediate need to shift the learning platform responsive to the needs of the learners lend a significant consideration in this study. This explored the perspectives of the learners in terms of their current capacity and its implications in the learning continuity using online learning. These were explored based on the availability of gadgets, internet connectivity, and their learning experiences with their teachers. These perspectives were also explored on the part of the teachers as they were the ones who provided learning inputs to the students. These are necessary information to identify strategic actions for the teaching and learning continuity plan of the university.