Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

9 lessons on teamwork and leadership from the military

Want to build an elite team? Look to the best of the best.

Team-focused research supported or executed by the military has yielded major insights into the nature of team performance

Team allegiance features heavily in the oaths soldiers take when they swear their service to their country. Navy SEALs pledge that their “loyalty to Country and Team is beyond reproach.” US Army Rangers vow ”Never shall I fail my comrades.” Airborne Troopers promise to “cherish the sacred trust and the lives of men with whom I serve.” The obvious reason: In a military combat situation, teamwork can literally mean the difference between life and death.

In your day-to-day job, the stakes clearly aren’t as high. Collaborating with your colleagues to meet a quarterly goal or get the latest product out the door obviously doesn’t involve the same level of risk as working together to thwart an enemy.

But military teams offer valuable lessons to civilian ones. In fact, teamwork researchers often study the military to help them understand what makes other types of teams—yup, that includes business ones— effective and successful. One recent study notes that “Team-focused research supported or executed by the military has yielded major insights into the nature of team performance, advanced the methods for measuring and improving team performance, and broken new ground in understanding the assembly of effective teams.”

We asked military leaders turned C-Suite execs which lessons and experiences have made them better leaders and team members. Consider this your boot camp.

Have the tough conversations

– Jake MacDonald, former Marine and a Lead Instructor with The Program , a team building and leadership development company My units were the first conventional unit to cross the line to Iraq in 2002. It was chaos. Someone had set the oil fields on fire. We pushed for about 48 hours without any sleep in 120 degree heat, with no food, wearing full chemical suits and gas masks. We finally got an order that we were going to stop. Then a few minutes later my boss told me to take my team back out on patrol. I was incensed because I was thinking, doesn’t this guy know what it means like to take care of his people ? But I quickly realized taking care of us meant bringing us all back home to our loved ones. And that meant my platoon had to provide security so other guys could get some sleep. When you’re looking out for your team’s best interests, you have to tell people things they don’t want to hear and hold each other accountable. It’s not enjoyable. But if I have a teammate who is consistently showing up late, or who isn’t prepared for meetings, that hurts everyone’s chances of accomplishing the mission—in the business world that might be hitting our numbers so we make money to give to our families. I’m a bad teammate if I don’t say anything to him. It doesn’t have to be horribly tense. Just talk to them, one on one. “This is something that I noticed, and I just wanted to talk to you about it.”

Share the load

-Jas on Van Camp, U.S. Army Special Forces (Green Beret). Van Camp is the CEO of Mission 6 Zero , a Utah-based management consulting organization and executive director of Warrior Rising , a non-profit organization dedicated to helping veterans achieve success in business.

We all began to focus on each other, rather than on ourselves. We began to forget about our pain. Time moved faster. The log felt lighter. Jason Van Camp

One of the first exercises they do in In Green Beret training is that they put you in teams, give you a huge log, and tell you to hold it over your head for hours. Everybody’s miserable and focused on themselves. In that horrible moment, I lifted my head up. The guys around me were all suffering just as bad as, if not worse than I was. Then my friend Pat lifted his head up as well. We looked at each other and he shouted, “Let’s go Jay, you got this.” And I mustered some energy to shout some words of encouragement back at him. I noticed that more guys were lifting their heads up and looking around. We all began to focus on each other, rather than on ourselves. We began to forget about our pain. Time moved faster. The log felt lighter. The reality is that nothing changed about our situation, except our attitude.

Those situations make or break teams. When the pressure is on, and you’re on a team, it’s not about you. The secret to the elite mindset of Special Operations Force is to look up. You need to take a risk and be vulnerable. You need to expose your heart and truly reach out and get to know the other people at your work. The art of building true relationships and getting to know each other is not in the content of the team’s discussions, but in the manner in which it communicates.

Communicate the mission

– John Dillon, a former submarine officer and nuclear engineer in the U.S. Navy. Today he is the CEO of Aerospike, Inc .

Good commanders in the military share elements of the mission with the troops— we need to take that bridge, we need to take that hill or we need to be secret or we need to be radio silent, and here’s why . Because if your team is in the field and they have to rely on sending a message back to the headquarters to make a decision, they’re probably going to be killed before they get an answer. If they understand what the higher order mission is, they can make the best decisions on their own. I still use that experience today running a large tech company. I routinely hold company-wide meetings to review our strategic objectives and challenges. Sharing aspects of our sales strategy may not be relevant, say, to the engineering team or the customer support team. Yet, by understanding the high-level challenges and strategies, people can make more informed decisions that might help the company for issues that do not bubble up to a more senior level.

Recognize team members who deliver on values

– Eric Kapitulik, a former platoon leader in the Marine Corps and founder and CEO of The Program , a team building and leadership development company

As a company you need core values and standards that reinforce those values. Eric Kapitulik

As a company you need core values and standards that reinforce those values. The Marine Corps has three core values—honor, courage, and commitment—that define how every Marine behaves. As leaders, we tend to recognize performance, which is important. But we also need to recognize when team members deliver on those core values with their behavior. That’s how we communicate what’s important to us. One way the Marine Corps recognizes Marines is simply calling out Marines to the front of formations and telling everyone about how those Marines were being great Marines. In business, say one of your core values is selflessness (a core value at my company). Openly call out people who meet that standard with their behavior. Send a team email, or at the weekly meeting say, “Hey, I’d like to recognize Sarah for how selfless she was. Every day last week before she finished work, she checked in with everyone else to see if there’s anything she can do to help.”

Value diverse opinions

– Jacob Werksman, a former Navy SEAL and CEO of Victory Strategies, a consulting firm that utilizes military skills, techniques, and practices to help private sector businesses achieve success.

In a SEAL platoon, you might have an officer that’s been in for 20 years and an enlisted individual right out of high school, who’s been in for four years. Their opinions are both valued equally because they bring different perspectives. I see businesses fail to recognize this. There’s been times that C-Suite executives hire us to do strategic planning. One of our first exercises was asking the administrative assistant at the front door, ‘What do you think about this problem? What would be your solution?’ And we used exactly what she said verbatim and proposed it to the C-Suite executives. And they thought it was a brilliant idea. And I said, ‘Well, that was from your administrative assistant.’ They were just in awe. Listen to your people.

Consider culture when recruiting

– Jacob Werksman

SEALs recruiting process is so demanding and elite that we know the quality of the individual we have within our organization. Every individual that joins, joins for the same reason. The same thing is very relative when it comes to private sector organizations, yet businesses rarely recruit the individual that has a why or a purpose that’s aligned with the organization. This is a misstep. It’s very hard to change someone with a negative attitude or that doesn’t have proper alignment within their organization rather than just recruiting that person from the get-go. When you’re hiring, ask questions like: Why do you want to work here? What does this organization mean to you? Why is it aligned with who you are as both a professional and a person?”

Over-communicate

– Jake MacDonald

When I was a second lieutenant, my boss made us put a sign over our desk that had three questions on it. It said, “What do I know? Who else needs to know? And have I told them?” I had to be able to answer those three questions every single day. And I messed that up a lot of times as a young officer because I made a lot of assumptions that people knew things, so I didn’t tell them. But at the end of the day, if something didn’t happen because they didn’t know about it, it wasn’t their fault, it was mine. That’s something we push on corporations a lot. A lot of times people feel like they might insult a team member by telling them that there’s a meeting. Or thinking they must know already. But then people don’t show up because they didn’t know about it. If you don’t communicate something because you don’t want to feel awkward, you’re actually missing out on a chance to help your teammates, to help make them better.

Embrace your team’s knowledge

– John Dillon

When I was 25 years old I was on a submarine and I had enlisted men that were 40 years old working for me that were specialists. Some had been working in electronics for 20 years. Some of them had masters and PhDs. I had an enormous amount of respect for them. I learned how to ask questions that weren’t invasive, but that helped me determine whether the team knew what they were doing and how to pass the solution, or whether they were guessing. Like: What’s the path to resolution? Is this going to be fixed in time for us to go to sea? Asking this way, instead of micromanaging them, made them feel like I trusted them, that I valued them.

It’s the same in my civilian work. I run software companies, have for a long time, and I don’t know more from a programmatic standpoint, than some of the engineers who work for me. I never will. So I ask them questions like Are we going to get this done? What’s your plan X, Y or Z?

Make contingency plans

– Jacob Werksman A lot of civilians think that the SEAL teams are just a sexy concept where all these guys are just great at everything and executing these missions. What they often fail to remind themselves is that everything that could or possibly would go wrong was planned for with a contingency plan 24 hours before that mission even took place. This removes the pressure of having to think through a problem while you’re on target because you’ve already planned for it. Corporate teams need to have similar backup plans . What will you do if a team member is absent for a significant amount of time? As a team, what’s your plan B, C, and D if your subcontractor drops the ball and throws you off your deadline?

Get stories like this in your inbox

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

- Cover Letters

- Jobs I've Applied To

- Saved Searches

- Subscriptions

- Marine Corps

- Coast Guard

- Space Force

- Military Podcasts

- Benefits Home

- Military Pay and Money

- Veteran Health Care

- VA eBenefits

- Veteran Job Search

- Military Skills Translator

- Upload Your Resume

- Veteran Employment Project

- Vet Friendly Employers

- Career Advice

- Military Life Home

- Military Trivia Game

- Veterans Day

- Spouse & Family

- Military History

- Discounts Home

- Featured Discounts

- Veterans Day Restaurant Discounts

- Electronics

- Join the Military Home

- Contact a Recruiter

- Military Fitness

Why Teamwork and Mental Toughness Are Critical to Military Success

The grueling nature of SEAL training -- or any military training, for that matter -- ingrains teamwork. No one makes it through training by themselves. You are always paired up with a "swim buddy," a "battle buddy" or partner, and you are always part of a boat crew or squad. Finally, you are part of a BUD/S class that typically starts out with 120-150+ students and graduates (six months later) an average of about 25-40.

Those graduates are not necessarily the biggest, fastest or strongest, but they are the ones with the highest mental toughness and are able to mesh into the team dynamics needed to succeed each day. Sure, fitness is critical to success, and the fitter you are, the less you have to rely on mental toughness. This combination of traits can help you focus on being a good team player and a superb communicator who supports classmates with any task.

Putting everyone in a military team through the same training allows them to look at each other and know by body language what they're saying and thinking. They're able to communicate without speaking or writing. You cannot be an effective team member without stellar verbal and non-verbal communication. Effective team communication is not just about transmitting well, but having the necessary attention to detail to receive signs that are often very subtle.

What makes SEALs good communicators on land is the fact that they communicate underwater as well, sometimes at night, using hand and arm squeezes. They take non-verbal communication to another level.

Seriously. From body language and hand signals, you can convey and receive information, such as the direction to travel to a target, the number of contacts, or if someone is injured or out of air and needs help. Your awareness peaks to a high level when you successfully communicate under stressful conditions.

The end result of military training is the ultimate teammate who is flexible with timetables and adjusts to get the job done, no matter what logistical issues arise. Members of teams are still individuals who thrive on competition and hate to be beaten in anything, but that competition makes the team better.

Being a competitor helps you through the tough times. Thinking about winning instead of merely surviving helps the team and the individual compete on a new level when the stakes are high. So, yes, your individual fitness one day may save your or your teammate's life and help you push yourself and others harder when needed.

Being a well-oiled machine with regard to teamwork and communication allows you to be flexible and adapt to any situation. Personal attention to detail enables strong communication (sending and receiving) throughout the team, and this can take contingency planning to a new level. Effective communications through detailed planning enables the team to anticipate when things go wrong and still be able execute flawlessly. None of these is possible by being a bad team player, and you cannot be a good team without communication skills.

Breathing and External Awareness

The best advice I ever received and still use today, especially when under time constraints, is to breathe. Not just any old breath. The goal is to take a big, deep breath (big inhale and long exhale), step back, increase your attention to detail to see the big picture, focus on what you need to do and execute.

By breathing, you increase external awareness, and this will help you be aware of your surroundings and the people in it. Notice the crowd around you, detach from the phone, make eye contact with co-workers and notice body language, as mentioned above. It is easy to see when someone needs help if you pay attention to the team.

When on a team at work, in sports or in the military, your plan nearly always goes wrong right from the start nine times out of 10. This never fails. Contingency planning requires smart planning, attention to detail and communication.

A team has to be flexible with changes. Just because things do not go as planned does not mean you have to go off course. Keep moving with a well-communicated contingency plan. A good team can make a plan and execute it. A great team can have things go wrong and still continue the mission with a contingency plan.

Any team, whether in sports, business, military or other public service, needs all of these skills to handle the complex and ever-changing nature of stressful situations. One minute is different from the previous minute, and this requires constant communication and teamwork, and that will produce the Dream Team.

This is why when teenagers ask me what they can do to prepare for the military, I always say become a better team player -- play sports, join a band, school play, student government and whatever else gets you and others thinking and moving as one.

Stew Smith is a former Navy SEAL and fitness author certified as a Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) with the National Strength and Conditioning Association. Visit his Fitness eBook store if you're looking to start a workout program to create a healthy lifestyle. Send your fitness questions to [email protected].

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for fitness and basic training tips, or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Stew Smith, CSCS®

You May Also Like

From the start of your military experience, you are building your ability to become a team player and work together to...

The longer running distance and pull-ups alone are the events most people have trouble with when assessing themselves at the...

The Murph Workout -- a Memorial Day tradition that honors fallen Navy SEAL Lt. Michael Murphy -- is popular throughout the...

This workout combination will feature useful combinations of upper-body pushing and pulling exercises for an effective...

Fitness by Service

- Military Daily News

- Army Fitness

- Navy Fitness

- Air Force Fitness

- Marine Corps Fitness

Select Service

- National Guard

Get the Military Insider Newsletter

Get the scoop on discounts, pay, benefits, and our latest award-winning content. Right in your inbox.

View more newsletters on our Subscriptions page.

Verify your free subscription by following the instructions in the email sent to:

Fitness by Category

- SpecOps Fitness

- Close Quarters Combat

- Fitness Videos

- Weight Training

Weight Loss

- Family Fitness

- General Fitness

- Law Enforcement

Popular Workouts

Running and Cardio

Here is a workout I like to do to check progress, or lack thereof, in a variety of running styles and benchmark distances.

It is possible to get through your training program with running only a few days a week, but your risk future injury.

The focus is to run shorter and faster runs in the week and a long, slower run at a comfortable pace on the weekend.

Most of the time, I receive emails from people who are seeking to pass their PFT, and just as many who wish to max out their...

Most Recent in Fitness

A wide variety of grips can make your pull-up workouts more enjoyable and diversify the strain on wrists, elbows, shoulders...

The role of teamwork on team performance in extreme military environments: an empirical study

Team Performance Management

ISSN : 1352-7592

Article publication date: 16 July 2020

Issue publication date: 14 August 2020

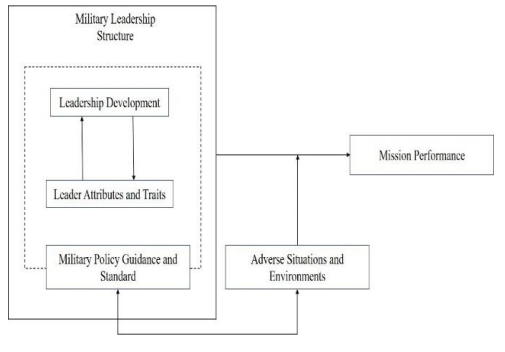

The purpose of this study is to explore the extent to which teamwork (developed either during an initial training phase or during a subsequent deployment phase) is influenced by the nature of the team’s environment (extreme vs non-extreme) and the extent to which teamwork is one of the explaining mechanisms for team performance.

Design/methodology/approach

Data was collected from 60 teams at 2 time-points: training phase in The Netherlands or Germany and deployment phase (in locations such as Afghanistan and Bosnia-Herzegovina).

This study’s results indicate that when teams consider working in extreme environments, they develop higher levels of teamwork as compared to teams expecting to work in non-extreme environments. These differences remain stable also during the deployment phase, such that teams operating in extreme environments will continue to have higher levels of teamwork as compared to teams operating in non-extreme environments.

Originality/value

With this study, the authors contribute to the teamwork quality research stream by empirically studying how teamwork quality develops in unique military contexts such as extreme environments. Studies in such contexts are relatively rare.

- Team performance

- Extreme environment

- Military teams

Meslec, N. , Duel, J. and Soeters, J. (2020), "The role of teamwork on team performance in extreme military environments: an empirical study", Team Performance Management , Vol. 26 No. 5/6, pp. 325-339. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-02-2020-0009

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Nicoleta Meslec, Jacco Duel and Joseph Soeters.

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial & non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Teams operate in a variety of contexts, from stable, predictable environments, to extreme environments. In extreme environments, events occur or are likely to occur such that they exceed an organization’s or a team’s capacity to prevent them. At the same time, those events may result in impactful or intolerable physical, psychological or material consequences to the organizational members ( Hannah et al. , 2009 ). Teams working for disaster responses, military teams in war zones and teams working in polar expeditions are just a few examples of teams that typically deal with extreme environments.

Teamwork has been found to be an important precursor of team performance in studies that have been conducted in relatively stable, regular organizational contexts ( LePine et al. , 2008 ). We define teamwork as group member’s interactions/interdependent acts that convert inputs to outcomes through cognitive, verbal and behavioral activities that are directed toward the achievement of a common goal ( Marks et al. , 2001 ). Teamwork includes both processes (such as backup behaviors and performance monitoring) as well as emergent states (such as trust and shared mental models). However, when it comes to the study of teamwork in extreme environments, empirical evidence is rather scant, partly because of the difficulties associated with studying such teams and the lack of their immediate accessibility ( Driskell et al. , 2018 ). One exception is the special issue on teamwork in extreme environments proposed by Maynard et al. (2018) .

Understanding how teamwork unfolds in teams operating in extreme environments and how teamwork affects team performance in such situations is nevertheless highly relevant. Task achievement of teams in extreme environments is oftentimes connected with the endangering of the team members’ lives or the ones of proximal or more distant others. Poor team performance in such contexts can have severe consequences. At the same time, we cannot just assume that teams in extreme environments function just the same as teams in regular environments ( Driskell et al. , 2017 ). Understanding the role of teamwork and how it can be enhanced in extreme environments is thus essential.

To what extent teams knowing to be working in the future in extreme environments develop better levels of teamwork as opposed to teams knowing to be working in regular, non-threatening environments?

To what extent these initial teamwork differences remain stable also during the military missions in extreme vs non-extreme environments?

What is the role of teamwork (T1 and T2) in predicting team performance in extreme environments?

With this study, we aim to bring a couple of contributions to the development of teams and groups research. First, we are aiming to get a better understanding of the effects of extreme environment as an environment-level input factor on teamwork development in an in vivo setting. As it has been recently emphasized, “what we don’t know regarding teams in extreme environments far exceeds what we do know” ( Driskell et al. , 2017 ) and at the same time we must explore and understand whether teams do behave differently, depending on the type of environment they are operating in.

Second, while looking at teamwork in extreme environments vs non-extreme environments at two different time points we are also contributing to the understanding of teams as dynamic systems. Organizational teams exist over time, having “a past and an expected future that influences their present” ( Harrison et al. , 2003 , p. 634). However, teamwork has oftentimes been studied from a static, cross-sectional perspective ( Harrison et al. , 2003 ; Mathieu et al. , 2017 ). Our study comes to contribute to the study of teams as dynamic entities and responds at the same time to more recent calls for studying teams while using a multi-period framework ( Humphrey and Aime, 2014 ; Mathieu et al. , 2017 ).

Theory and hypotheses

In line with Eby et al. (1999) and also Marks et al. (2001) , we define and operationalize teamwork as a global unitary construct that consists of various facets or clusters. These facets are highly interrelated, which creates difficulties in parceling teamwork in separate sub-constructs. Previous studies identified high correlations between these subdimensions ( Campion et al. , 1993 ; Campion et al. , 1996 ) and as a consequence they were oftentimes measured and studied as a unitary construct ( Janz et al. , 1997 ).

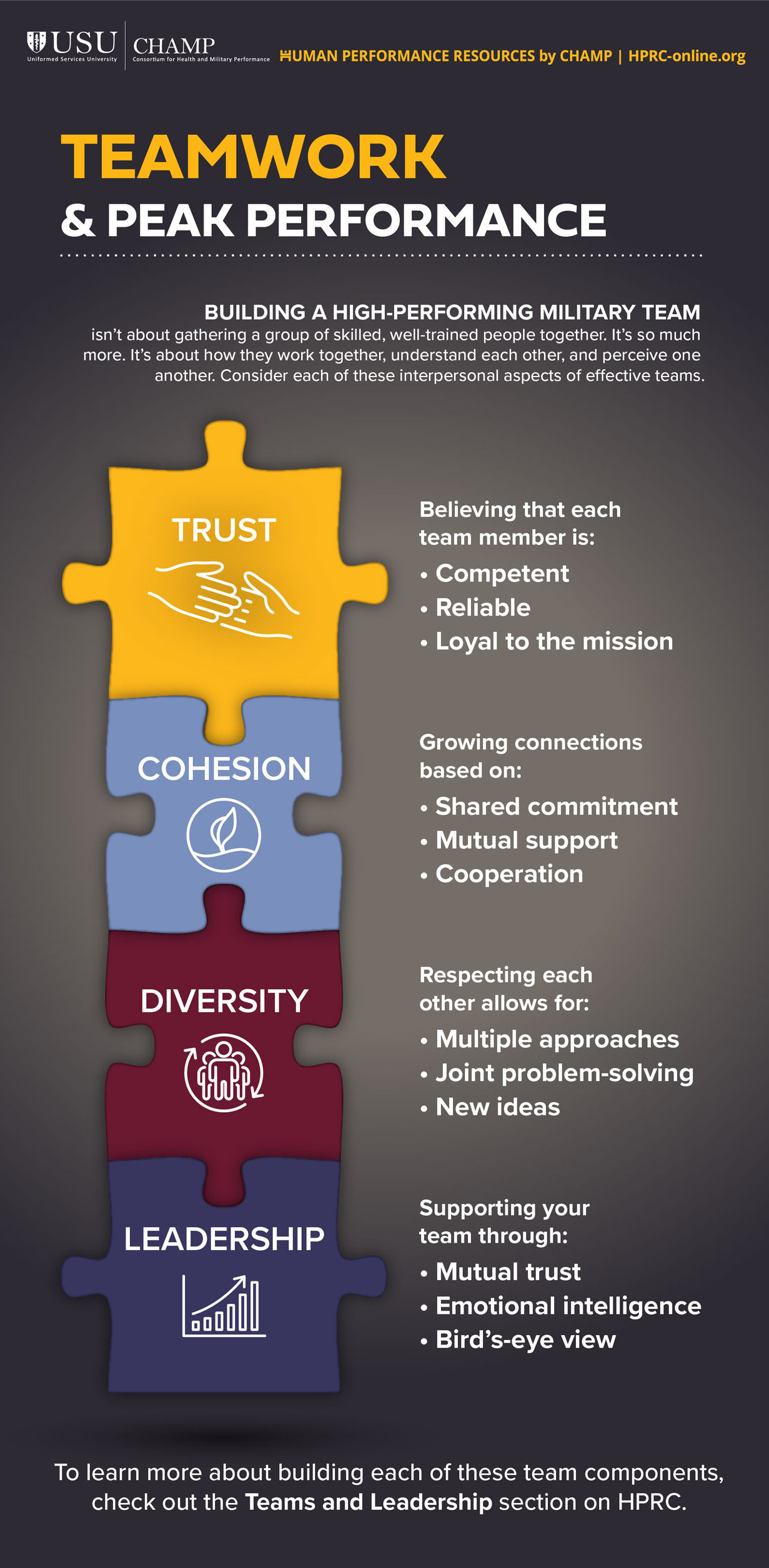

For this study, we include four teamwork facets that have proven to be highly relevant for the coordination and execution of team tasks ( Salas et al. , 2005 ) and that exemplify the mutual or reciprocal action or influence among team members in action teams. These facets are mutual performance monitoring, backup behavior, shared mental models and mutual trust.

Mutual performance monitoring is defined as the ability of teams to “keep track of fellow team members’ work while carrying out their own to ensure that everything is running as expected and to ensure that they are following procedures correctly” ( McIntyre and Salas, 1995 , p. 23). Backup behavior represents the extent to which team members provide feedback and coaching to each other, assist each other in performing their tasks and complete tasks for members when overload is detected ( Marks et al. , 2000 ). Shared mental models are defined as collective representations of task and team-related knowledge. Team-related knowledge structures contain information on aspects such as what the team should strive for, how the team should function and how team members should behave in certain situations. Task-related knowledge structures contain information such as task procedures or procedures related to the use of tools and equipment ( Salas et al. , 2005 ). Mutual trust is “the shared perception that individuals in the team will perform particular actions important to its members and will recognize and protect the rights and interests of all the team members engaged in their joint endeavor” ( Salas et al. , 2005 ; p. 568–569).

These four facets are a good representation of the two most important dimensions of teamwork (i.e. processes and emergent states) in a military setting. Mutual performance monitoring and backup behavior represent crucial teamwork processes for coordination and execution of the task whereas shared mental models and trust represent the climate in which such processes can be rightfully enacted. Without trust, team members may regard mutual performance monitoring as spying on each other and reduce information sharing. Without shared mental models, team members would have difficulties to anticipate and predict each other’s needs and are therefore less likely to engage in backup behaviors ( Salas et al. , 2005 ).

Effects of extreme environments on teamwork over time

Both threat rigidity theory ( Staw et al. , 1981 ) and more recent adaptations of input-process-output models of teams in extreme environments ( Driskell et al. , 2017 ) discuss the potential negative effects of extreme environments on teamwork. When confronted with external threat, teams are more likely to narrow their attention to a local focus, to restrict their information processing and ignore relevant pieces of information from the environment ( Staw et al. , 1981 ; Driskell et al. , 2017 ). This has been described as a “freeze,” non-adaptive reaction with negative consequences on team processes and emergent states. In an experimental study with ad-hoc teams, Kamphuis et al. (2011) showed that physical threat leads to a decrease of team discussions, coordination and supporting behavior. When teams are faced with threat, they reduce their focus on the team and narrow their attentional capacity related to social cues ( Kamphuis et al. , 2011 ). Although proponents of threat-rigidity theory acknowledge that a shared team history might influence the extent to which this “freezing” reaction emerges (e.g. previous successful episodes might enhance teamwork and reduce the “freezing” effect), no specific claims have been advanced. We build further on threat rigidity theory to empirically test two connected claims.

Teams training for a military mission in an extreme environment will develop higher levels of teamwork than teams training for a military mission in a non-extreme environment.

During the deployment phase, teams will maintain the same level of teamwork as the one developed during the training phase such that teams operating in extreme environments will display higher levels of teamwork in comparison with teams operating in non-extreme environments.

Mediating role of teamwork

Teamwork (both at the training phase and while being deployed) will positively mediate the relation between extreme environments and team performance while being deployed.

Context of the study

This study was conducted among military teams of the Royal Netherlands Army that were prepared for (T1) and deployed to Afghanistan or Bosnia-Herzegovina (T2) in 2006 or 2007. The training phase included intensive preparation in The Netherlands or Germany. This phase lasted several months and included activities such as training team-level skills and drills necessary for the tasks to be completed during deployment. During the training phase, the teams knew that they were going to be deployed either to an extreme environment context or to a regular, non-threatening context (i.e. in Bosnia that had calmed after the peak of hostilities in 1995). The composition of the teams remained the same in both phases, with some exceptions. Also teams in extreme as well as non-extreme environment received the same training.

Military teams were deployed to Afghanistan (extreme environment for most teams) or Bosnia-Herzegovina (regular, non-war environment for all teams). The troops in Afghanistan aimed to contribute to a safe, stable and democratic nation-state. The teams provided security for the population, trained the police and the Afghan army and combated forces that opposed the legal government. Moreover, the troops contributed to the development of the country by executing several reconstruction projects, such as building schools or repairing the infrastructure. The teams in Afghanistan varied in the tasks they had to perform. A large part of the teams in this study conducted (long range) patrols, escorted provincial reconstruction teams, manned strongholds and outposts and were engaged in combat operations. Most teams in Afghanistan operated under dangerous circumstances, as testified by a number of casualties that occurred during the mission. Besides combat actions, the main threats against the teams were bomb attacks with improvised explosive devices and suicide attacks. Several attacks wounded or killed soldiers and civilians. For the teams in Afghanistan, the deployment lasted four months.

The troops in Bosnia-Herzegovina mainly assisted the government in combating (organized) crime, providing for border control against smuggling and disarming the population. In addition, they monitored the democratic and economic development of the country, and assisted the government with these developments. The teams that participated in this study in Bosnia-Herzegovina operated under relatively safe circumstances. Most teams conducted “policing activities” such as searching houses for illegal weapons, and preventing illegal logging in forests. Other teams provided for logistical support. There were no casualties during this mission period. For the teams in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the deployment lasted six months.

Data regarding teamwork and team performance were collected at two time-points. Time 1 data were collected at the end of an extensive training period two to four months before the start of the deployment. Time 2 data were collected two months after the start of the deployment for the troops in Afghanistan and, three months after the start of the deployment for the troops in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Team performance at T2 was used as the dependent variable for our study while team performance at T1 was used as a control variable for two of our models. To avoid common method bias, we used multiple sources for our data collection ( Podsakoff et al. , 2003 ). First, we asked the team members to provide information about teamwork. Second, we asked the commanders of the immediate command level above the team (mostly the platoon commanders and their deputies) to provide information on the performance of the teams under their command. Most operations in Afghanistan and Bosnia-Herzegovina were conducted with platoons, without other hierarchical levels present. So, the platoon commander and their deputy were the only parties external to the team to have a reliable, first-hand view on team performance.

At both measurement moments, the units to which the teams belonged were dispersed, with teams training at several training locations (T1) or operating at outposts (T2). Also, at T1 and to a lesser degree at T2, team members were not always available. At T1, a number of soldiers were absent because of the individual training courses they were following in various training centers. At T2, not all team members were able to answer the questionnaires as they could be absent because of sickness or leave for a special occasion or a temporarily re-assignment. These situations account for the different response rates and numbers of teams in the study. Moreover, these situations made the coordination and execution of data collection difficult. Specific personnel belonging to the military units to which the teams belonged were asked to hand out the questionnaires. The questionnaires were collected at times that were most convenient for each unit within a timeframe of about two weeks at both T1 and T2. Because of this procedure, it is not exactly clear how many soldiers were asked to participate in the study.

At T1, 1,498 respondents participated, and at T2, there were 1,360 respondents. After eliminating the teams with one respondent only and the ones missing identification numbers, the final sample consisted of 301 teams that provided teamwork data at T1 and 258 teams that provided teamwork data at T2. The average team size (of respondents) was 5.8 at T1 (standard deviation [SD] = 4.8) and 3.8 at T2 (SD = 2.4). Performance ratings were available for 86 teams at T1 and 109 teams at T2. When matching the data from T1 and T2 for all variables, the sample size equaled 60 teams that provided information on teamwork and for which performance ratings from platoon commanders were available. To maximize the power of the data gathered, we used all data we had to test various hypotheses. This resulted in different sample sizes for the testing of various hypotheses. Information about the sample sizes can be found in the results tables ( Table 3 ).

Teamwork was measured with a self-rating scale containing 27 items that was administered to the respondents of this study. Teamwork facets included mutual performance monitoring, backup behavior, shared mental models and trust. The scale was developed by a small team of (military) teamwork experts in line with the definitions of these teamwork facets as provided by Salas et al. (2005) and other studies that adapted scales for specific settings ( Schaubroeck et al. , 2012 ). See Table 1 for the items and response options. The overall teamwork scale indicates good reliability; Cronbach’s alpha at T1 is 0.95 and 0.96 at T2. We conducted a factor analysis to check if the items pertain to one overall teamwork factor. Principles axes extraction with oblique rotation was used because we assumed that the measured variables were a linear function of one latent variable (teamwork). Results were similar for both teamwork T1 and T2. Here, we report the results for teamwork at T1; more details about the factor loadings for T1 and T2 can be found in Table 1 . In the initial extraction, four factors emerged with eigenvalues higher than 1. However, in line with our conceptualization, the scree plot suggested one general factor explaining the majority of variance. The first factor accounted for 47.6% of the total variance (the other factors explained 9%, 6.5% and 4.4% of the variance). This provides sufficient evidence to use teamwork as an overall construct.

Team performance was measured with a nine-item scale. The questions were developed by a team of (military) teamwork experts in line with previously developed team performance scales ( Rousseau and Aubé, 2010 ). The Cronbach’s alpha at T1 is 0.90 and at T2 is 0.91, indicating good reliability. We ran an exploratory factor analysis to check for the unidimensionality of the construct. One factor emerged accounting for 57.3% of the total variance at T1 and 59.1% of the total variance at T2. Factor loadings and items can be found in Table 2 .

Extreme environment was coded in a dichotomous way (0 = not extreme; 1 = extreme). Commanders of the units to which the teams belonged provided information regarding the teams operating in extreme environments. In general, teams deployed to Afghanistan were assessed as operating in extreme environments if they operated oftentimes outside the forward operating base. This means these teams had to perform their tasks in dangerous and demanding circumstances. The teams were confronted with serious threats to military personnel, such as the risk and the actual occurrence of (suicide) attacks, or attacks by improvised explosive devices, leading to military personnel getting wounded and killed. This is a very salient aspect of extreme environments in military missions ( Van den Berg, 2009 ). Teams that were deployed to Afghanistan, but performed their tasks in the forward operating base (so they were mostly able to work and live under protective circumstances), and teams that were deployed to Bosnia-Herzegovina were assessed to perform their tasks in (relatively) safe environments (i.e. not extreme).

Aggregation to team level constructs

Given that teamwork is a team-level variable and data were gathered from individual team members, an inter-rater agreement index that justifies aggregation is required. We computed an r wG(J) index for teamwork ratings in line with the recommendation given by LeBreton and Senter (2008) and James et al. (1984) . The values for the r wG(J) index are higher than 0.80 for both T1 and T2. In line with Bliese (2000) , we also computed interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (1) and ICC (2). The average ICC (1) for all items was 0.1 while for ICC (2) was 0.35.Overall these scores suggest that there is agreement among the members within each team and aggregation of scores at a team level is justified ( LeBreton and Senter, 2008 ; James, 1982 ).

To test H1 and H2 , we ran two independent samples t -test for teamwork at T1 and T2, respectively. In addition, we ran a generalized linear model (GLM) repeated measures analysis with teamwork as a within factor and extreme environment as a between factor. To test H3 , we ran two mediation models (see Models 1 and 3 in Table 4 ) while using the nonparametric resampling procedure of bootstrapping developed by Hayes (2012) . This method has been proved powerful and valid for testing intervening variable effects ( Hayes, 2009 ; MacKinnon et al. , 2004 ; Williams and MacKinnon, 2008 ). In Models 2 and 4, we ran the same two mediation models but this time we controlled for previous levels of performance and teamwork.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the team level measures are displayed in Table 3 . Teamwork at T1 is positively correlated with teamwork at T2 ( r = 0.29, p < 0.01), extreme environment variable correlates positively with both teamwork at T1 ( r = 0.18, p < 0.01) and teamwork at T2 ( r = 0.29, p < 0.01) and team performance at T2 correlates with both teamwork at T1 ( r = 0.22, p < 0.01) and team performance at T1 ( r = 0.63, p < 0.01). The results of our test of H1 indicate that teams knowing to work in extreme environments displayed higher levels of teamwork at T1 (M = 3.91, SD = 0.32) as opposed to teams anticipating to work in non-extreme environments (M = 3.77, SD = 0.41), with t = 2.35, p = 0.03 and d = 0.38. To test H2 , we first ran an independent sample t -test to check whether teamwork differences remain stable at T2. Our results indicate that teams working in extreme environments (M = 3.92, SD = 0.37) at T2 displayed higher levels of teamwork as opposed to teams working in non-extreme environment (M = 3.66, SD = 0.45), with t = 4.35, p = 0.000 and d = 0.63. We also checked the robustness of our results with an additional GLM repeated measures analysis, with teamwork as a within factor (T1 and T2) and extreme environment as a between factor. The within subjects effect of teamwork was not significant with Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F (1,164) = 0.64 and p = 0.42. Also there was no significant effect for the interaction between teamwork and extreme environment, with Wilks’ λ = 0.99, F (1,164) = 0.66 and p = 0.41. This indicates that teams did not change the level of their teamwork from T1 to T2, irrespective of the environment in which they operated (extreme vs non-extreme). The between effect was significant with F (1, 164) = 12.42 and p = 0.001. This indicates that teamwork differed between extreme and non-extreme environment context such that teams in extreme environment displayed higher levels of teamwork. This is illustrated also in Figure 1 .

The results of our mediation analysis (see Models 1 and 3 in Table 4 ) indicate that extreme environment has a negative effect on team performance T2 ( coeff = −0.47, p < 0.001 for teamwork T1 as a mediator and coeff = −0.35, p < 0.001 for teamwork T2 as a mediator). Teamwork T1 ( coeff = 0.46, p < 0.001) as well as teamwork T2 ( coeff = 0.50, p < 0.001) have a positive direct effect on team performance T2 and at the same time mediate the relation between extreme environment and team performance T2 [ coeff = 0.11 CI (0.004; 0.32) for teamwork T1 and 0.12 CI (0.02; 0.31) for teamwork T2]. In Models 2 and 4, we ran the same two mediation models but this time we controlled for previous levels of performance (T1) and teamwork. We wanted to explore the extent to which both teamwork at T1 and teamwork at T2 are equally relevant in predicting team performance at T2. At the same time, we wanted to explore if teamwork has a predictive power beyond and above the predictive power of team performance displayed at T1. Our results indicate that in the case of teamwork T1 as a mediator, when controlling for previous performance (performance T1) and teamwork T2, the results remain unchanged. Extreme environment continues to have a negative effect on team performance ( coeff = −0.58, p < 0.001). Teamwork T1 continues to have a positive effect on performance T2 ( coeff = 0.41, p < 0.05) and to mediate the relation between extreme environment and performance T2 [ coeff = 0.09, CI (0.003; 0.25)]. In the case of teamwork T2 as a mediator however, the results change. When controlling for the effects of teamwork T1 and performance T1, the effect of teamwork T2 on team performance T2 disappears ( coeff = 0.19, p > 0.05) while the effect of teamwork T1 as a control variable is significant and positive ( coeff = 0.41, p < 0.05). The effect of extreme environment on teamwork T2 is also no longer significant ( coeff = 0.005, p > 0.05), while the effect of extreme environment on team performance T2 remains significant ( coeff = −0.58, p < 0.001). The indirect effect also disappears, coeff = 0.009 CI (−0.01; 0.10). This means that the mediation effect of teamwork T2 on team performance is qualified by the effect of teamwork T1, indicating the relevance of previously developed teamwork episodes for later performance.

Discussions

The purpose of our study was to explore the extent to which teamwork (developed either during the training phase or during deployment phase) is influenced by the nature of the team’s environment (extreme vs non-extreme) and the extent to which teamwork is one of the explaining mechanisms for team performance. In line with H1 and H2 , our results indicate that when teams consider working in extreme environments, they develop higher levels of teamwork as compared to teams expecting to work in non-extreme environments. Furthermore, these differences remain stable also during the deployment phase, such that teams operating in extreme environments will continue to have higher levels of teamwork as compared to teams operating in non-extreme environments. Teamwork reflects a climate of the team where team members trust, help, monitor and coordinate with each other in an effective manner. Development of such a climate can be seen as an adaptation mechanism through which teams attempt to better cope with the idea of confronting dangerous situations in the future. Given that teams have been specifically trained for the situations they would encounter during the training phase, they are able to maintain their level of teamwork also during the deployment phase. With these findings, we contribute to the threat-rigidity theory ( Staw et al. , 1981 ) by showing that teams operating in extreme environments do not always experience the “freezing” reaction, described as a decrease in the quality of interpersonal interactions in the presence of threat. In our study, we found evidence that when teams develop their teamwork prior to the extreme environment missions they are more likely to maintain it also during these missions. Thus, having a shared history matters for the maintenance of teamwork.

In H3 , we advanced the idea that teamwork developed during the training phase, as well as teamwork developed during the deployment phase will mediate the relation between extreme environments and team performance at T2. Our results indicate that extreme environments hamper team performance. This effect has been shown in theoretical treatises and experimental work before. In this study, the effect is replicated in real-life circumstances. However, this negative effect is attenuated by the quality of interpersonal interactions developed within teams. Our results show that teamwork developed early in a team’s life (during the training phase in this case) can have long-lasting effects for team performance (during the deployment phase). This effect remains robust even when we control for previous team performance episodes and teamwork displayed during the deployment phase. Not the same can be concluded about the mediation effect of teamwork T2 and thus H3 is only partially supported. When controlling for previous teamwork and performance episodes, the mediation effect of teamwork T2 disappears. Teams are dynamic systems, where time plays an important role ( Marks et al. , 2001 ). McGrath et al. (1993) found for example that performance losses generated by virtual interaction disappear after three or four weeks of interaction. If one would measure the impact of virtual interaction on performance after five weeks, he/she would wrongly conclude that there is no effect. Similarly, our study shows that if one would only measure teamwork at T2, he/she would wrongly conclude that this teamwork episode is crucial for performance in extreme environments. This would be a wrong conclusion because the effect disappears if one controls for previous teamwork and performance episodes. Longitudinal research designs are inevitable to determine the dynamics in teamwork and performance. Overall, with this finding we contribute to a better understanding of team performance in extreme environments.

Overall our findings have implications for practice. Managers and trainers working with teams operating in extreme environments should be aware of the crucial role teamwork plays for performance. Early stimulation of teamwork quality is highly important and thus managers and trainers should consider developing specific trainings and teambuilding activities at the very early phases of team development.

Strengths, limitations and directions for future research

One notable strength of our study is the combination between the setting in which this study was conducted and the design used. In this regard, our study has important methodological contributions. Studies in military operational conditions are hard to find, even though there are famous exceptions such as Schaubroeck et al. (2012) . Collecting data at two different time points, while using multiple sources, further increases the complexities associated with such data collection. As a result, we could not incorporate a very large number of teams with teamwork and team performance ratings at both measurement moments which is a limitation of this study. We embraced this approach, however, because of the limits associated with cross-sectional designs, such as type 1 and 2 errors ( Harrison et al. , 2003 ). Although studying teams “in the wild” has a high ecological validity, it comes also with drawbacks. Given that the teams were not randomly assigned to the two conditions (extreme vs non-extreme environment), other intervening variables might explain also the differences found especially for H1 and H2 . Future studies could try to replicate these results in a controlled experimental setting. Also, we were only able to collect data at two different timepoints. It would be interesting to explore how teamwork evolves also across a longer period of time. Team research in general lacks empirical evidence concerning the dynamics of team processes and emergent states over time.

All in all our study shows that teams knowing to be working in the future in extreme environments develop higher levels of teamwork in comparison with teams that expect to work in regular environments and at the same time they are able to maintain these levels of teamwork also in later phases. Initial teamwork is the main mechanism through which the negative direct effects of extreme environments on team performance are diminished. These findings have implications for practice. Managers, commanders, instructors and trainers working with teams that prepare themselves to operate in extreme environments should facilitate the development of such teamwork at very early stages of team development. Teamwork may provide teams with the necessary abilities to successfully adapt to threatening situations in the foreseeable future.

Teamwork development from training to deployment phase

Teamwork facets and factor loadings

For Model 1, N = 84; for Model 3, N = 82; for Models 2 and 4, N = 60; Team perf = team performance; T1 = time 1; T2 = time 2; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

Austin , J.R. ( 1997 ), “ A cognitive framework for understanding demographic influences in groups ”, The International Journal of Organizational Analysis , Vol. 5 No. 4 , pp. 342 - 359 , doi: 10.1108/eb028873 .

Bliese , P.D. ( 2000 ), “ Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: implications for data aggregation and analysis ”, in Klein , K.J. and Kozlowski , S.W.J. (Eds), Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions , Jossey-Bass , pp. 349 - 381 .

Campion , M.A. , Medsker , G.J. and Higgs , A.C. ( 1993 ), “ Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: implications for designing effective work groups ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 46 No. 4 , pp. 823 - 850 , doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01806.x .

Campion , M.A. , Papper , E.M. and Medsker , G.J. ( 1996 ), “ Relations between work team characteristics and effectiveness: a replication and extension ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 49 No. 2 , pp. 429 - 452 , doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01806.x .

Chen , G. , Thomas , B. and Wallace , J.C. ( 2005 ), “ A multilevel examination of the relationships among training outcomes, mediating regulatory processes, and adaptive performance ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 90 No. 5 , pp. 827 - 841 , doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.827 .

Driskell , T. , Driskell , J.E. , Burke , C.S. and Salas , E. ( 2017 ), “ Team roles: a review and integration ”, Small Group Research , Vol. 48 No. 4 , pp. 482 - 511 , doi: 10.1177/1046496417711529 .

Driskell , T. , Salas , E. and Driskell , J.E. ( 2018 ), “ Teams in extreme environments: alterations in team development and teamwork ”, Human Resource Management Review , Vol. 28 No. 4 , pp. 434 - 449 .

Eby , L.T. , Meade , A.W. , Parisi , A.G. and Douthitt , S.S. ( 1999 ), “ The development of an individual-level teamwork expectations measure and the application of a within-group agreement statistic to assess shared expectations for teamwork ”, Organizational Research Methods , Vol. 2 No. 4 , pp. 366 - 394 , doi: 10.1177/109442819924003 .

Friedman , V.J. and Lipshitz , R. ( 1992 ), “ Teaching people to shift cognitive gears: overcoming resistance on the road to model II ”, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , Vol. 28 No. 1 , pp. 118 - 136 , doi: 10.1177/0021886392281010 .

Hannah , S.T. , Uhl-Bien , M. , Avolio , B.J. and Cavarretta , F.L. ( 2009 ), “ A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts ”, The Leadership Quarterly , Vol. 20 No. 6 , pp. 897 - 919 , doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.09.006 .

Harrison , D.A. , Mohammed , S. , McGrath , J.E. , Florey , A.T. and Vanderstoep , S.W. ( 2003 ), “ Time matters in team performance: effects of member familiarity, entrainment, and task discontinuity on speed and quality ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 56 No. 3 , pp. 633 - 669 , doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00753.x .

Hayes , A.F. ( 2009 ), “ Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium ”, Communication Monographs , Vol. 76 No. 4 , pp. 408 - 420 , doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360 .

Hayes , A.F. ( 2012 ), “ PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling ”, available at: www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

Humphrey , S.E. and Aime , F. ( 2014 ), “ Team microdynamics: toward an organizing approach to teamwork ”, The Academy of Management Annals , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 443 - 503 , doi: 10.1080/19416520.2014.904140 .

James , L.R. ( 1982 ), “ Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 67 No. 2 , pp. 219 - 229 .

James , L.R. , Demaree , R.G. and Wolf , G. ( 1984 ), “ Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 69 No. 1 , pp. 85 - 98 , doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.85 .

Janz , B.D. , Colquitt , J.A. and Noe , R.A. ( 1997 ), “ Knowledge worker team effectiveness: the role of autonomy, interdependence, team development, and contextual support variables ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 50 No. 4 , pp. 877 - 904 , doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1997.tb01486.x .

Kamphuis , W. , Gaillard , A.W. and Vogelaar , A.L. ( 2011 ), “ The effects of physical threat on team processes during complex task performance ”, Small Group Research , Vol. 42 No. 6 , pp. 700 - 729 , doi: 10.1177/1046496411407522 .

Kozlowski , S.W.J. and Ilgen , D.R. ( 2006 ), “ Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams ”, Psychological Science in the Public Interest , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 77 - 124 , doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00030.x .

LeBreton , J.M. and Senter , J.L. ( 2008 ), “ Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement ”, Organizational Research Methods , Vol. 11 No. 4 , pp. 815 - 852 , doi: 10.1177/1094428106296642 .

LePine , J.A. , Piccolo , R.F. , Jackson , C.L. , Mathieu , J.E. and Saul , J.R. ( 2008 ), “ A meta-analysis of teamwork processes: test of a multidimensional model and relationships with team effectiveness criteria ”, Personnel Psychology , Vol. 61 No. 2 , pp. 273 - 307 , doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00114.x .

McGrath , J.E. , Arrow , H. , Gruenfeld , D.H. , Hollingshead , A.B. and O'Connor , K.M. ( 1993 ), “ Groups, tasks, and technology the effects of experience and change ”, Small Group Research , Vol. 24 No. 3 , pp. 406 - 420 , doi: 10.1177/1046496493243007 .

McIntyre , R.M. and Salas , E. ( 1995 ), “ Measuring and managing for team performance: lessons from complex environments ”, in Guzzo , R.A. , Salas , E. and Associates (Eds), Team Effectiveness and Decision Making in Organizations , Jossey-Bass , San Francisco , pp. 9 - 45 .

MacKinnon , D.P. , Lockwood , C.M. and Williams , J. ( 2004 ), “ Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods ”, Multivariate Behavioral Research , Vol. 39 No. 1 , pp. 99 - 128 , doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 .

Marks , M.A. , Mathieu , J.E. and Zaccaro , S.J. ( 2001 ), “ A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes ”, The Academy of Management Review , Vol. 26 No. 3 , pp. 356 - 376 , doi: 10.2307/259182 .

Marks , M.A. , Zaccaro , S.J. and Mathieu , J.E. ( 2000 ), “ Performance implications of leader briefings and team- interaction training for team adaptation to novel environments ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 85 No. 6 , pp. 971 - 986 , doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.971 .

Mathieu , J.E. , Hollenbeck , J.R. , van Knippenberg , D. and Ilgen , D.R. ( 2017 ), “ A century of work teams in the ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 102 No. 3 , pp. 452 - 467 , doi: 10.1037/apl0000128 .

Maynard , M.T. , Kennedy , D.M. and Resick , C.J. ( 2018 ), “ Teamwork in extreme environments: lessons, challenges, and opportunities ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 39 No. 6 , pp. 695 - 700 .

Podsakoff , P.M. , MacKenzie , S.B. , Lee , J.Y. and Podsakoff , N.P. ( 2003 ), “ Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 88 No. 5 , pp. 879 - 903 , doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 .

Rasmussen , T.H. and Jeppesen , H.J. ( 2006 ), “ Teamwork and associated psychological factors: a review ”, Work and Stress , Vol. 20 No. 2 , pp. 105 - 128 , doi: 10.1080/02678370600920262 .

Rousseau , V. and Aubé , C. ( 2010 ), “ Team self-managing behaviors and team effectiveness: the moderating effect of task routineness ”, Group and Organization Management , Vol. 35 No. 6 , pp. 751 - 781 , doi: 10.1177/1059601110390835 .

Salas , E. , Burke , C.S. and Cannon-Bowers , J.A. ( 2000 ), “ Teamwork: emerging principles ”, International Journal of Management Reviews , Vol. 2 No. 4 , pp. 339 - 356 , doi: 10.1111/1468-2370.00046 .

Salas , E. , Sims , D.E. and Burke , C.S. ( 2005 ), “ Is there a “big five” in teamwork? ”, Small Group Research , Vol. 36 No. 5 , pp. 555 - 599 , doi: 10.1177/1046496405277134 .

Schaubroeck , J.M. , Hannah , S.T. , Avolio , B.J. , Kozlowski , S.W. , Lord , R.G. , Treviño , Dimotakis , N. and Peng , A.C. , ( 2012 ), “ Embedding ethical leadership within and across organization levels ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 55 No. 5 , pp. 1053 - 1078 , doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0064 .

Schein , E.H. ( 1969 ), “ The mechanisms of change ”, The Planning of Change , Vol. 2 , pp. 98 - 107 .

Staw , B.M. , Sandelands , L.E. and Dutton , J.E. ( 1981 ), “ Threat rigidity effects in organizational behavior: a multilevel analysis ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 26 No. 4 , pp. 501 - 524 , doi: 10.2307/2392337 .

Tuckman , B.W. ( 1965 ), “ Developmental sequence in small groups ”, Psychological Bulletin , Vol. 63 No. 6 , pp. 384 - 399 , doi: 10.1037/h0022100 .

Van den Berg , C.E. ( 2009 ), “ Soldiers under threat: an exploration of the effects of real threat on soldiers’ perceptions, attitudes and morale ”, Doctoral dissertation, Radboud University Nijmegen , the Netherlands .

Williams , J. and MacKinnon , D.P. ( 2008 ), “ Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models ”, Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 23 - 51 , doi: 10.1080/10705510701758166 .

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to commemorate the contribution of Ad Vogelaar, who passed away after the field work and primary analyses had been conducted.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics