Internet Explorer Alert

It appears you are using Internet Explorer as your web browser. Please note, Internet Explorer is no longer up-to-date and can cause problems in how this website functions This site functions best using the latest versions of any of the following browsers: Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Opera, or Safari . You can find the latest versions of these browsers at https://browsehappy.com

- Publications

- HealthyChildren.org

Shopping cart

Order Subtotal

Your cart is empty.

Looks like you haven't added anything to your cart.

- Career Resources

- Philanthropy

- About the AAP

- The Role of the Pediatrician in the Promotion of Healthy, Active Living

- How Can You Support Patients in Healthy, Active Living? Check Out Updated Report

- Helping Kids Build Healthy Active Lives: AAP Policy Explained

- Climate Change & Children’s Health: AAP Policy Explained

- News Releases

- Policy Collections

- The State of Children in 2020

- Healthy Children

- Secure Families

- Strong Communities

- A Leading Nation for Youth

- Transition Plan: Advancing Child Health in the Biden-Harris Administration

- Health Care Access & Coverage

- Immigrant Child Health

- Gun Violence Prevention

- Tobacco & E-Cigarettes

- Child Nutrition

- Assault Weapons Bans

- Childhood Immunizations

- E-Cigarette and Tobacco Products

- Children’s Health Care Coverage Fact Sheets

- Opioid Fact Sheets

- Advocacy Training Modules

- Subspecialty Advocacy Report

- AAP Washington Office Internship

- Online Courses

- Live and Virtual Activities

- National Conference and Exhibition

- Prep®- Pediatric Review and Education Programs

- Journals and Publications

- NRP LMS Login

- Patient Care

- Practice Management

- AAP Committees

- AAP Councils

- AAP Sections

- Volunteer Network

- Join a Chapter

- Chapter Websites

- Chapter Executive Directors

- District Map

- Create Account

- Early Relational Health

- Early Childhood Health & Development

- Safe Storage of Firearms

- Promoting Firearm Injury Prevention

- Mental Health Education & Training

- Practice Tools & Resources

- Policies on Mental Health

- Mental Health Resources for Families

The Importance of Access to Comprehensive Sex Education

Comprehensive sex education is a critical component of sexual and reproductive health care.

Developing a healthy sexuality is a core developmental milestone for child and adolescent health.

Youth need developmentally appropriate information about their sexuality and how it relates to their bodies, community, culture, society, mental health, and relationships with family, peers, and romantic partners.

AAP supports broad access to comprehensive sex education, wherein all children and adolescents have access to developmentally appropriate, evidence-based education that provides the knowledge they need to:

- Develop a safe and positive view of sexuality.

- Build healthy relationships.

- Make informed, safe, positive choices about their sexuality and sexual health.

Comprehensive sex education involves teaching about all aspects of human sexuality, including:

- Cyber solicitation/bullying.

- Healthy sexual development.

- Body image.

- Sexual orientation.

- Gender identity.

- Pleasure from sex.

- Sexual abuse.

- Sexual behavior.

- Sexual reproduction.

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- Abstinence.

- Contraception.

- Interpersonal relationships.

- Reproductive coercion.

- Reproductive rights.

- Reproductive responsibilities.

Comprehensive sex education programs have several common elements:

- Utilize evidence-based, medically accurate curriculum that can be adapted for youth with disabilities.

- Employ developmentally appropriate information, learning strategies, teaching methods, and materials.

- Human development , including anatomy, puberty, body image, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

- Relationships , including families, peers, dating, marriage, and raising children.

- Personal skills , including values, decision making, communication, assertiveness, negotiation, and help-seeking.

- Sexual behavior , including abstinence, masturbation, shared sexual behavior, pleasure from esx, and sexual dysfunction across the lifespan.

- Sexual health , including contraception, pregnancy, prenatal care, abortion, STIs, HIV and AIDS, sexual abuse, assault, and violence.

- Society and culture , including gender roles, diversity, and the intersection of sexuality and the law, religion, media, and the arts.

- Create an opportunity for youth to question, explore, and assess both personal and societal attitudes around gender and sexuality.

- Focus on personal practices, skills, and behaviors for healthy relationships, including an explicit focus on communication, consent, refusal skills/accepting rejection, violence prevention, personal safety, decision making, and bystander intervention.

- Help youth exercise responsibility in sexual relationships.

- Include information on how to come forward if a student is being sexually abused.

- Address education from a trauma-informed, culturally responsive approach that bridges mental, emotional, and relational health.

Comprehensive sex education should occur across the developmental spectrum, beginning at early ages and continuing throughout childhood and adolescence :

- Sex education is most effective when it begins before the initiation of sexual activity.

- Young children can understand concepts related to bodies, gender, and relationships.

- Sex education programs should build an early foundation and scaffold learning with developmentally appropriate content across grade levels.

- AAP Policy outlines considerations for providing developmentally appropriate sex education throughout early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood.

Most adolescents report receiving some type of formal sex education before age 18. While sex education is typically associated with schools, comprehensive sex education can be delivered in several complementary settings:

- Schools can implement comprehensive sex education curriculum across all grade levels

- The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) provides guidelines for providing developmentally appropriate comprehensive sex education across grades K-12.

- Pediatric health clinicians and other health care providers are uniquely positioned to provide longitudinal sex education to children, adolescents, and young adults.

- Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents outlines clinical considerations for providing comprehensive sex education at all developmental stages, as a part of preventive health care.

- Research suggests that community-based organizations should be included as a source for comprehensive sexual health promotion.

- Faith-based communities have developed sex education curricula for their congregations or local chapters that emphasize the moral and ethical aspects of sexuality and decision-making.

- Parents and caregivers can serve as the primary sex educators for their children, by teaching fundamental lessons about bodies, development, gender, and relationships.

- Many factors impact the sex education that youth receive at home, including parent/caregiver knowledge, skills, comfort, culture, beliefs, and social norms.

- Virtual sex education can take away feelings of embarrassment or stigma and can allow for more youth to access high quality sex education.

Comprehensive sex education provides children and adolescents with the information that they need to:

- Understand their body, gender identity, and sexuality.

- Build and maintain healthy and safe relationships.

- Engage in healthy communication and decision-making around sex.

- Practice healthy sexual behavior.

- Understand and access care to support their sexual and reproductive health.

Comprehensive sex education programs have demonstrated success in reducing rates of sexual activity, sexual risk behaviors, STIs, and adolescent pregnancy and delaying sexual activity. Many systematic reviews of the literature have indicated that comprehensive sex education promotes healthy sexual behaviors:

- Reduced sexual activity.

- Reduced number of sexual partners.

- Reduced frequency of unprotected sex.

- Increased condom use.

- Increased contraceptive use.

However, comprehensive sex education curriculum goes beyond risk-reduction, by covering a broader range of content that has been shown to support social-emotional learning, positive communication skills, and development of healthy relationships.

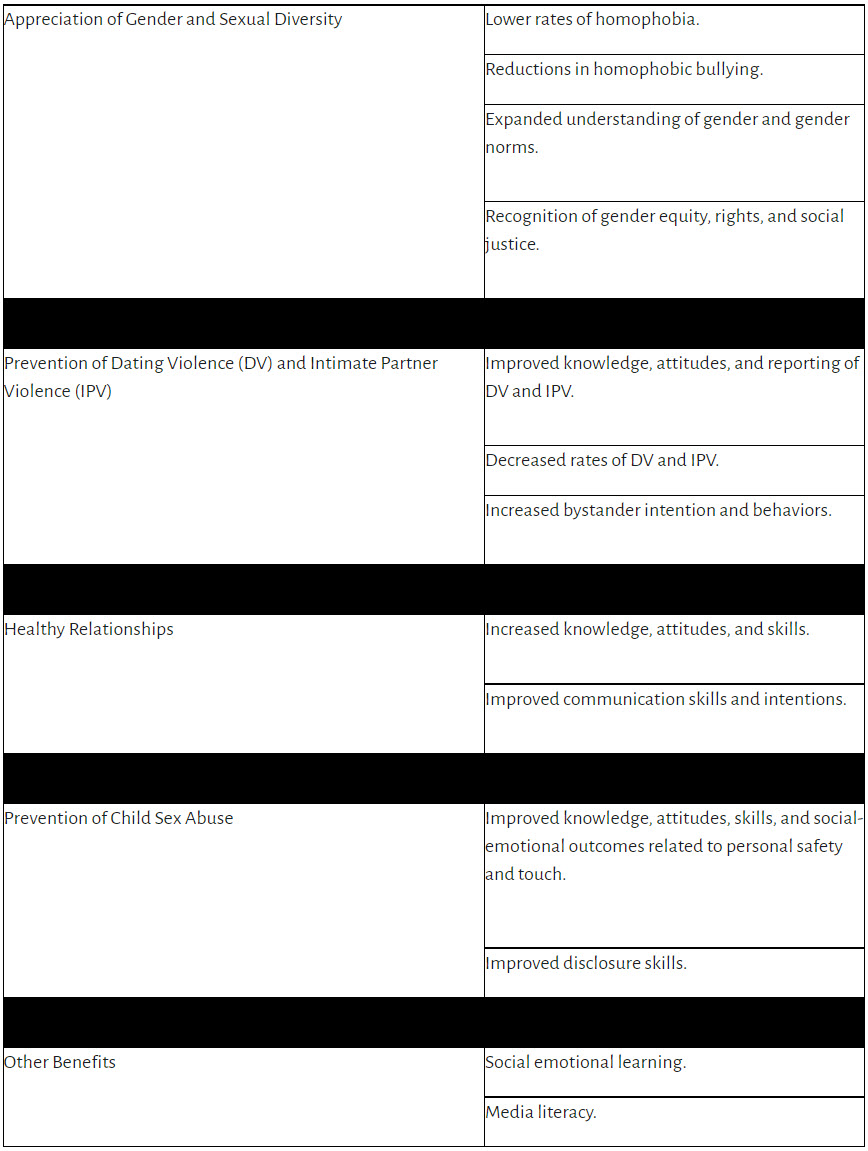

A 2021 review of the literature found that comprehensive sex education programs that use a positive, affirming, and inclusive approach to human sexuality are associated with concrete benefits across 5 key domains:

Benefits of comprehensive sex education programs

When children and adolescents lack access to comprehensive sex education, they do not get the information they need to make informed, healthy decisions about their lives, relationships, and behaviors.

Several trends in sexual health in the US highlight the need for comprehensive sex education for all youth.

Education about condom and contraceptive use is needed:

- 55% of US high school students report having sexual intercourse by age 18 .

- Self-reported condom use has decreased significantly among high school students.

- Only 9% of sexually active high school students report using both a condom for STI-prevention and a more effective form of birth control to prevent pregnancy .

STI prevention is needed:

- Adolescents and young adults are disproportionately impacted by STIs.

- Cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis are rising rapidly among young people.

- When left untreated , these infections can lead to infertility, adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes, and increased risk of acquiring new STIs.

- Youth need comprehensive, unbiased information about STI prevention, including human papillomavirus (HPV) .

Continued prevention of unintended pregnancy is needed:

- Overall US birth rates among adolescent mothers have declined over the last 3 decades.

- There are significant geographic disparities in adolescent pregnancy rates, with higher rates of pregnancy in rural counties and in southern and southwestern states.

- Social drivers of health and systemic inequities have caused racial and ethnic disparities in adolescent pregnancy rates.

- Eliminating disparities in adolescent pregnancy and birth rates can increase health equity, improve health and life outcomes, and reduce the economic impact of adolescent parenting.

Misinformation about sexual health is easily available online:

- Internet use is nearly universal among US children and adolescents.

- Adolescents report seeking sexual health information online .

- Sexual health websites that adolescents visit can contain inaccurate information .

Prevention of sex abuse, dating violence, and unhealthy relationships is needed:

- Child sexual abuse is common: 25% of girls and 8% of boys experience sexual abuse during childhood .

- Youth who experience sexual abuse have long-term impacts on their physical, mental, and behavioral health.

- 1 in 11 female and 1 in 14 male students report physical DV in the last year .

- 1 in 8 female and 1 in 26 male students report sexual DV in the last year .

- Youth who experience DV have higher rates of anxiety, depression, substance use, antisocial behaviors, and suicide risk.

The quality and content of sex education in US schools varies widely.

There is significant variation in the quality of sex education taught in US schools, leading to disparities in attitudes, health information, and outcomes. The majority of sex education programs in the US tend to focus on public health goals of decreasing unintended pregnancies and preventing STIs, via individual behavior change.

There are three primary categories of sex educational programs taught in the US :

- Abstinence-only education , which teaches that abstinence is expected until marriage and typically excludes information around the utility of contraception or condoms to prevent pregnancy and STIs.

- Abstinence-plus education , which promotes abstinence but includes information on contraception and condoms.

- Comprehensive sex education , which provides medically accurate, age-appropriate information around development, sexual behavior (including abstinence), healthy relationships, life and communication skills, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

State laws impact the curriculum covered in sex education programs. According to a report from the Guttmacher Institute :

- 26 US states and Washington DC mandate sex education and HIV education.

- 18 states require that sex education content be medically accurate.

- 39 states require that sex education programs provide information on abstinence.

- 20 states require that sex education programs provide information on contraception.

US states have varying requirements on sex education content related to sexual orientation :

- 10 states require sex education curriculum to include affirming content on LGBTQ2S+ identities or discussion of sexual health for youth who are LGBTQ2S+.

- 7 states have sex education curricular requirements that discriminate against individuals who are LGBTQ2S+.Youth who live in these states may face additional barriers to accessing sexual health information.

Abstinence-only sex education programs do not meet the needs of children and adolescents.

While abstinence is 100% effective in preventing pregnancy and STIs, research has conclusively shown that abstinence-only sex education programs do not support healthy sexual development in youth.

Abstinence-only programs are ineffective in reaching their stated goals, as evidenced by the data below:

- Abstinence-only programs are unsuccessful in delaying sex until marriage .

- Abstinence-only sex education programs do not impact the rates of pregnancy, STIs, or HIV in adolescents .

- Youth who take a “virginity pledge” as part of abstinence-only education programs have the same rates of premarital sex as their peers who do not take pledges, but are less likely to use contraceptives .

- US states that emphasize abstinence-only education have higher rates of adolescent pregnancy and birth .

Abstinence-only programs can harm the healthy sexual and mental development of youth by:

- Withholding information or providing inaccurate information about sexuality and sexual behavior .

- Contributing to fear, shame, and stigma around sexual behaviors .

- Not sharing information on contraception and barrier protection or overstating the risks of contraception .

- Utilizing heteronormative framing and stigma or discrimination against students who are LGBTQ2S+ .

- Reinforcing harmful gender stereotypes .

- Ignoring the needs of youth who are already sexually active by withholding education around contraception and STI prevention.

Abstinence-plus sex education programs focus solely on decreasing unintended pregnancy and STIs.

Abstinence-plus sex education programs promote abstinence until marriage. However, these programs also provide information on contraception and condom use to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs.

Research has demonstrated that abstinence-plus programs have an impact on sexual behavior and safety, including:

- HIV prevention.

- Increase in condom use .

- Reduction in number of sexual partners .

- Delay in initiation of sexual behavior .

While these programs add another layer of education, they do not address the broader spectrum of sexuality, gender identity, and relationship skills, thus withholding critical information and skill-building that can impact healthy sexual development.

AAP and other national medical and public health associations support comprehensive sex education for youth.

Given the evidence outlined above, AAP and other national medical organizations oppose abstinence-only education and endorse comprehensive sex education that includes both abstinence promotion and provision of accurate information about contraception, STIs, and sexuality.

National medical and public health organizations supporting comprehensive sex education include:

- American Academy of Pediatrics .

- American Academy of Family Physicians.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists .

- American Medical Association .

- American Public Health Association .

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine .

Pediatric clinics provide a unique opportunity for comprehensive sex education.

Pediatric health clinicians typically have longitudinal care relationships with their patients and families, and thus have unique opportunities to address comprehensive sex education across all stages of development.

The clinical visit can serve as a useful adjunct to support comprehensive sex education provided in schools, or to fill gaps in knowledge for youth who are exposed to abstinence-only or abstinence-plus curricula.

AAP policy and Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents provide recommendations for comprehensive sex education in clinical settings, including:

- Encouraging parent-child discussions on sexuality, contraception, and internet/media use.

- Understanding diverse experiences and beliefs related to sexuality and sex education and meeting the unique needs of individual patients and families.

- Including discussions around healthy relationships, dating violence, and intimate partner violence in clinical care.

- Discussing methods of contraception and STI/HPV prevention prior to onset of sexual intercourse.

- Providing proactive and developmentally appropriate sex education to all youth, including children and adolescents with special health care needs.

Perspective

Karen Torres, Youth activist

There were two cardboard bears, and a person explained that one bear wears a bikini to the beach and the other bear wears shorts – that is the closest thing I ever got to sex ed throughout my entire K-12 education. I often think about that bear lesson because it was the day our institutions failed to teach me anything about my body, relationships, consent, and self-advocacy, which became even more evident after I was sexually assaulted at 16 years old. My story is not unique, I know that many young people have been through similar traumas, but many of us were also subjected to days, months, and years of silence and embarrassment because we were never given the knowledge to know how to spot abuse or the language to ask for help. Comprehensive sex ed is so much more than people make it out to be, it teaches about sex but also about different types of experiences, how to respect one another, how to communicate in uncomfortable situations, how to ask for help and an insurmountable amount of other valuable lessons.

From these lessons, people become well-rounded, people become more empathetic to other experiences, and people become better. I believe comprehensive sex ed is vital to all people and would eventually work as a part to build more compassionate communities.

Many US children and adolescents do not receive comprehensive sex education; and rates of formal sex education have declined significantly in recent decades.

Barriers to accessing comprehensive sex education include:

Misinformation, stigma, and fear of negative reactions:

- Misinformation and stigma about the content of sex education curriculum has been the primary barrier to equitable access to comprehensive sex education in schools for decades .

- Despite widespread parental support for sex education in schools, fears of negative public/parent reactions have led school administrators to limit youth access to the information they need to make healthy decisions about their sexuality for nearly a half-century.

- In recent years, misinformation campaigns have spread false information about the framing and content of comprehensive sex education programs, causing debates and polarization at school board meetings .

- Nearly half of sex education teachers report that concerns about parent, student, or administrator responses are a barrier to provision of comprehensive sex education.

- Opponents of comprehensive sex education often express concern that this education will lead youth to have sex; however, research has demonstrated that this is not the case . Instead, comprehensive sex ed is associated with delays in initiation of sexual behavior, reduced frequency of sexual intercourse, a reduction in number of partners, and an increase in condom use.

- Some populations of youth lack access to comprehensive sex education due to a societal belief that they are asexual, in need of protection, or don’t need to learn about sex. This barrier particularly impacts youth with disabilities or special health care needs .

- Sex ed curricula in some schools perpetuate gender/sex stereotypes, which could contribute to negative gender stereotypes and negative attitudes towards sex .

Inconsistencies in school-based sex education:

- There is significant variation in the content of sex education taught in schools in the US, and many programs that carry the same label (eg, “abstinence-plus”) vary widely in curriculum.

- While decisions about sex education curriculum are made at the state level, the federal government has provided funding to support abstinence-only education for decades , which incentivizes schools to use these programs.

- Since 1996, more than $2 billion in federal funds have been spent to support abstinence-only sex education in schools.

- 34 US states require schools to use abstinence-only curriculum or emphasize abstinence as the main way to avoid pregnancy and STIs.

- Only 16 US states require instruction on condoms or contraception.

- It is not standard to include information on how to come forward if a student is being sexually abused, and many schools do not have a process for disclosures made.

- Because of this, abstinence-only programs are commonly used in US schools, despite overwhelming evidence that they are ineffective in delaying sexual behavior until marriage, and withhold critical information that youth need for healthy sexual and relationship development.

Need for resources and training:

- Integration of comprehensive sex education into school curriculum requires financial resources to strengthen and expand evidence-based programs.

- Successful implementation of comprehensive sex education requires a trained workforce of teachers who can address the curriculum in age-appropriate ways for students in all grade-levels.

- Education, training, and technical assistance are needed to support pediatric health clinicians in addressing comprehensive sex education in clinical settings, as a complement to school-based education.

Lack of diversity and cultural awareness in curricula:

- A history of systemic racism, discrimination, and long-standing health, social and systemic inequities have created racial and ethnic disparities in access to sexual health services and representation in sex education materials. The legacy of intergenerational trauma in the medical system should be acknowledged in sex education curricula.

- Sex education curriculum is often centered on a white audience, and does not address or reflect the role of systemic racism in sexuality and development .

- Traditional abstinence-focused sex education programs have a heteronormative focus and do not address the unique needs of youth who are LGBTQ2S+ .

- Sex education programs often do not address reproductive body diversity, the needs of those with differences in sex development, and those who identify as intersex .

- Sex education programs often do not reflect the unique needs of youth with disabilities or special health care needs .

- Sex education programs are often not tailored to meet the religious considerations of faith communities.

- There is a need for sex education programs designed to help youth navigate sexual health and development in the context of their own culture and community .

Disparities in access to comprehensive sex education.

The barriers listed above limit access to comprehensive sex education in schools and communities. While these barriers impact youth across the US, there are some populations who are less likely to have access to comprehensive to sex education.

Youth who are LGBTQ2S+:

- Only 8% of students who are LGBTQ2S+ report having received sexual education that was inclusive .

- Students who are LGBTQ2S+ are 50% more likely than their peers who are heterosexual to report that sex education in their schools was not useful to them .

- Only 13% of youth who are bisexual+ and 10% of youth who are transgender and gender expansive report receiving sex education in schools that felt personally relevant.

- Only 20% of youth who are Black and LGBTQ2S+ and 13% of youth who are Latinx and LGBTQ2S+ report receiving sex education in schools that felt personally relevant.

- Only 10 US states require affirming content on LGBTQ2S+ relationships in sex education curriculum.

Youth with disabilities or special health care needs:

- Youth with disabilities or special health care needs have a particular need for comprehensive sex education, as these youth are less likely to learn about sex or sexuality form their parents , healthcare providers , or peer groups .

- In a national survey, only half of youth with disabilities report that they have participated in sex education .

- Typical sex education may not be sufficient for youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder, and special methods and curricula are necessary to match their needs .

- Lack the desire or maturity for romantic or sexual relationships.

- Are not subject to sexual abuse.

- Do not need sex education.

- Only 3 states explicitly include youth with disabilities within their sex education requirements.

Youth from historically underserved communities:

- Students who are Black in the US are more likely than students who are white to receive abstinence-only sex education , despite significant support from parents and students who are Black for comprehensive sex education.

- Youth who are Black and female are less likely than peers who are white to receive education about where to obtain birth control prior to initiating sexual activity.

- Youth who are Black and male and Hispanic are less likely than their peers who are white to receive formal education on STI prevention or contraception prior to initiating sexual activity.

- Youth who are Hispanic and female are less likely to receive instruction about waiting to have sex than youth of other ethnicities.

- Tribal health educators report challenges in identifying culturally relevant sex education curriculum for youth who are American Indian/Alaska Native.

- In a 2019 study, youth who were LGBTQ2S+ and Black, Latinx, or Asian reported receiving inadequate sex education due to feeling unrepresented, unsupported, stigmatized, or bullied.

- In survey research, many young adults who are Asian American report that they received inadequate sex education in school.

Youth from rural communities:

- Adolescents who live in rural communities have faced disproportionate declines in formal sex education over the past two decades, compared with peers in urban/suburban areas.

- Students who live in rural communities report that the sex education curriculum in their schools does not serve their needs .

Youth from communities and schools that are low-income:

- Data has shown an association between schools that are low-resource and lower adolescent sexual health knowledge, due to a combination of fewer school resources and higher poverty rates/associated unmet health needs in the student body.

- Youth with family incomes above 200% of the federal poverty line are more likely to receive education about STI prevention, contraception, and “saying no to sex,” than their peers below 200% of the poverty line.

Youth who receive sex education in some religious settings:

- Most adolescents who identify as female and who attended church-based sex education programs report instructions on waiting until marriage for sex, while few report receiving education about birth control.

- Young people who received sex education in religious schools report that education focused on the risks of sexual behavior (STIs, pregnancy) and religious guilt; leading to them feeling under-equipped to make informed decisions about sex and sexuality later in life.

- Youth and teachers from religious schools have identified a need for comprehensive sex education curriculum that is tailored to the needs of faith communities .

Youth who live in states that limit the topics that can be covered in sex education:

- Students who live in the 34 states that require sex education programs to stress abstinence are less likely to have access to critical information on STI prevention and contraception.

- Prohibitions on addressing abortion in sex education or mandates that sex education curricula include medically inaccurate information on abortion designed to dissuade youth from terminating a pregnancy.

- Limitations on the types of contraception that can be covered in sex education curricula.

- Requirements that sex education teachers promote heterosexual, monogamous marriage in sex education.

- Lack of requirements to address healthy relationships and communication skills.

- Lack of requirements for teacher training or certification.

Comprehensive sex education has significant benefits for children and adolescents.

Youth who are exposed to comprehensive sex education programs in school demonstrate healthier sexual behaviors:

- Increased rates of contraception and condom use.

- Fewer unplanned pregnancies.

- Lower rates of STIs and HIV.

- Delayed initiation of sexual behavior.

More broadly, comprehensive sexual education impacts overall social-emotional health , including:

- Enhanced understanding of gender and sexuality.

- Lower rates of homophobia and related bullying.

- Lower rates of dating violence, intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and child sexual abuse.

- Healthier relationships and communication skills.

- Understanding of reproductive rights and responsibilities.

- Improved social-emotional learning, media literacy, and academic achievement.

Comprehensive sex education curriculum goes beyond risk reduction, to ensure that youth are supported in understanding their identity and sexuality and making informed decisions about their relationships, behaviors, and future. These benefits are critical to healthy sexual development.

Impacts of a lack of access to comprehensive sex education.

When youth are denied access to comprehensive sex education, they do not get the information and skill-building required for healthy sexual development. As such, they face unnecessary barriers to understanding their gender and sexuality, building positive interpersonal relationships, and making informed decisions about their sexual behavior and sexual health.

Impacts of a lack of comprehensive sex education for all youth can include :

- Less use of condoms, leading to higher risk of STIs, including HIV.

- Less use of contraception, leading to higher risk of unplanned pregnancy.

- Less understanding and increased stigma and shame around the spectrum of gender and sexual identity.

- Perpetuated stigma and embarrassment related to sex and sexual identity.

- Perpetuated gender stereotypes and traditional gender roles.

- Higher rates of youth turning to unreliable sources for information about sex, including the internet, the media, and informal learning from peer networks.

- Challenges in interpersonal communication.

- Challenges in building, maintaining, and recognizing safe, healthy peer and romantic relationships.

- Lower understanding of the importance of obtaining and giving enthusiastic consent prior to sexual activity.

- Less awareness of appropriate/inappropriate touch and lower reporting of child sexual abuse.

- Higher rates of dating violence and intimate partner violence, and less intervention from bystanders.

- Higher rates of homophobia and homophobic bullying.

- Unsafe school environments.

- Lower rates of media literacy.

- Lower rates of social-emotional learning.

- Lower recognition of gender equity, rights, and social justice.

In addition, the lack of access to comprehensive sex education can exacerbate existing health disparities, with disproportionate impacts on specific populations of youth.

Youth who identify as women, youth from communities of color, youth with disabilities, and youth who are LGBTQ2S+ are particularly impacted by inequitable access to comprehensive sex education, as this lack of education can impact their health, safety, and self-identity. Examples of these impacts are outlined below.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm young women.

- Female bodies are more prone to STI infection and more likely to experience complications of STI infection than male bodies.

- Female bodies are disproportionately impacted by long-term health consequences of STIs , including pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy.

- Female bodies are less likely to have or recognize symptoms of certain STI infections .

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common STI in young women , and can cause long-term health consequences such as genital warts and cervical cancer.

- Women bear the health and economic effects of unplanned pregnancy.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by providing medically-accurate, evidence based information on effective strategies to prevent STI infections and unplanned pregnancy.

- Students who identify as female are more likely to experience sexual or physical dating violence than their peers who identify as male. Some of this may be attributed to underreporting by males due to stigma.

- Students who identify as female are bullied on school property more often than students who identify as male.

- Young women ages 16-19 are at higher risk of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault than the general population.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by guiding the development of healthy self-identities, challenging harmful gender norms, and building the skills required for respectful, equitable relationships.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth from communities of color.

- Youth of color benefit from seeing themselves represented in sex education curriculum.

- Sex education programs that use a framing of diversity, equity, rights, and social justice , informed by an understanding of systemic racism and discrimination, have been found to increase positive attitudes around reproductive rights in all students.

- There is a critical need for sex education programs that reflect youth’s cultural values and community .

- Comprehensive sex education can address these needs by developing curriculum that is inclusive of diverse communities, relationships, and cultures, so that youth see themselves represented in their education.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in STI and HIV infection.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in unplanned pregnancy and births among adolescents.

- Nearly half of youth who are Black ages 13-21 report having been pressured into sexual activity .

- Adolescent experience with dating violence is most prevalent among youth who are American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multiracial.

- Adolescents who are Latinx are more likely than their peers who are non-Latinx to report physical dating violence .

- Youth who are Black and Latinx and who experience bullying are more likely to suffer negative impacts on academic performance than their white peers.

- Students who are Asian American and Pacific Islander report bullying and harassment due to race, ethnicity, and language.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by guiding the development of healthy self-identities, challenging harmful stereotypes, and building the skills required for respectful, equitable relationships.

- Young people of color—specifically those from Black , Asian-American , and Latinx communities– are often hyper-sexualized in popular media, leading to societal perceptions that youth are “older” or more sexually experienced than their white peers.

- Young men of color—specifically those from Black and Latinx communities—are often portrayed as aggressive or criminal in popular media, leading to societal perceptions that youth are dangerous or more sexually aggressive or experienced than white peers.

- These media portrayals can lead to disparities in public perceptions of youth behavior , which can impact school discipline, lost mentorship and leadership opportunities, less access to educational opportunities afforded to white peers, and greater involvement in the juvenile justice system.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by including positive representations of diverse youth in curriculum, challenging harmful stereotypes, and building the skills required for respectful relationships.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth with disabilities or special health care needs.

- Youth with disabilities need inclusive, developmentally-appropriate, representative sex education to support their health, identity, and development .

- Youth with special health care needs often initiate romantic relationships and sexual behavior during adolescence, similar to their peers.

- Youth with disabilities and special health care needs benefit from seeing themselves represented in sex education to access the information and skills to build healthy identities and relationships.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses this need by including positive representation of youth with disabilities and special health care needs in curriculum and providing developmentally-appropriate sex education to all youth.

- When youth with disabilities and special health care needs do not get access to the comprehensive sex education that they need, they are at increased risk of sexual abuse or being viewed as a sexual offender.

- Youth with disabilities and special health care needs are more likely than peers without disabilities to report coercive sex, exploitation, and sexual abuse.

- Youth with disabilities and special health care needs report more sexualized behavior and victimization online than their peers without disabilities.

- Youth with disabilities are at greater risk of bullying and have fewer friend relationships than their peers.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by providing education on healthy relationships, consent, communication, and bodily autonomy.

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth who are LGBTQ2S+.

- Most sex education curriculum is not inclusive or representative of LGBTQ2S+ identities and experiences.

- Because school-based sex education often does not meet their needs, youth who are LGBTQ2S+ are more likely to seek sexual health information online , and thus are more likely to come across misinformation.

- The majority of parents support discussion of sexual orientation in sex education classes.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by including positive representation of LGBTQ2S+ individuals, romantic relationships, and families.

- Sex education curriculum that overlooks or stigmatizes youth who are LGBTQ2S+ contributes to hostile school environments and harms the healthy sexual and mental development .

- Youth who are LGBTQ2S+ face high levels of discrimination at school and are more likely to miss school because of bullying or victimization .

- Ongoing experiences with stigma, exclusion, and harassment negatively impact the mental health of youth who are LGBTQ2S+.

- Comprehensive sex education provides inclusive curriculum and has been shown to improve understanding of gender diversity, lower rates of homophobia, and reduce homophobic bullying in schools.

- Youth who are LGBTQ2S+ are more likely than their heterosexual peers to report not learning about HIV/STIs in school .

- Lack of education on STI prevention leaves LGBTQ2S+ youth without the information they need to make informed decisions, leading to discrepancies in condom use between LGBTQ2S+ and heterosexual youth.

- Some LGBTQ2S+ populations carry a disproportionate burden of HIV and other STIs: these disparities begin in adolescence , when youth who are LGBTQ2S+ do not receive sex education that is relevant to them.

- Comprehensive sex education provides the knowledge and skills needed to make safe decisions about sexual behavior , including condom use and other forms of STI and HIV prevention.

- Youth who are LBGTQ2S+ or are questioning their sexual identity report higher rates of dating violence than their heterosexual peers.

- Youth who are LGBTQ2S+ or are questioning their sexual identity face higher prevalence of bullying than their heterosexual peers.

- Comprehensive sex education teaches youth healthy relationship and communication skills and is associated with decreases in dating violence and increases in bystander interventions .

A lack of comprehensive sex education can harm youth who are in foster care.

- More than 70% of children in foster care have a documented history of child abuse and or neglect.

- More than 80% of children in foster care have been exposed to significant levels of violence, including domestic violence.

- Youth in foster care are racially diverse, with 23% of youth identifying as Black and 21% of identifying as Latinx, who will have similar experiences as those highlighted in earlier sections of this report.

- Removal is emotionally traumatizing for almost all children. Lack of consistent/stable placement with a responsive, nurturing caregiver can result in poor emotional regulation, impulsivity, and attachment problems.

- Comprehensive sex education addresses these issues by providing evidence-based, culturally appropriate information on healthy relationships, consent, communication, and bodily autonomy.

Sex education is often the first experience that youth have with understanding and discussing their gender and sexual health.

Youth deserve to a strong foundation of developmentally appropriate information about gender and sexuality, and how these things relate to their bodies, community, culture, society, mental health, and relationships with family, peers, and romantic partners.

Decades of data have demonstrated that comprehensive sex education programs are effective in reducing risk of STIs and unplanned pregnancy. These benefits are critical to public health. However, comprehensive sex education goes even further, by instilling youth with a broad range of knowledge and skills that are proven to support social-emotional learning, positive communication skills, and development of healthy relationships.

Last Updated

American Academy of Pediatrics

What Works In Schools : Sexual Health Education

CDC’s What Works In Schools Program improves the health and well-being of middle and high school students by:

- Improving health education,

- Connecting young people to the health services they need, and

- Making school environments safer and more supportive.

What is sexual health education?

Quality provides students with the knowledge and skills to help them be healthy and avoid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), sexually transmitted infections (STI) and unintended pregnancy.

A quality sexual health education curriculum includes medically accurate, developmentally appropriate, and culturally relevant content and skills that target key behavioral outcomes and promote healthy sexual development. 1

The curriculum is age-appropriate and planned across grade levels to provide information about health risk behaviors and experiences.

Sexual health education should be consistent with scientific research and best practices; reflect the diversity of student experiences and identities; and align with school, family, and community priorities.

Quality sexual health education programs share many characteristics. 2-4 These programs:

- Are taught by well-qualified and highly-trained teachers and school staff

- Use strategies that are relevant and engaging for all students

- Address the health needs of all students, including the students identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQ)

- Connect students to sexual health and other health services at school or in the community

- Engage parents, families, and community partners in school programs

- Foster positive relationships between adolescents and important adults.

How can schools deliver sexual health education?

A school health education program that includes a quality sexual health education curriculum targets the development of functional knowledge and skills needed to promote healthy behaviors and avoid risks. It is important that sexual health education explicitly incorporate and reinforce skill development.

Giving students time to practice, assess, and reflect on skills taught in the curriculum helps move them toward independence, critical thinking, and problem solving to avoid STIs, HIV, and unintended pregnancy. 5

Quality sexual health education programs teach students how to: 1

- Analyze family, peer, and media influences that impact health

- Access valid and reliable health information, products, and services (e.g., STI/HIV testing)

- Communicate with family, peers, and teachers about issues that affect health

- Make informed and thoughtful decisions about their health

- Take responsibility for themselves and others to improve their health.

What are the benefits of delivering sexual health education to students?

Promoting and implementing well-designed sexual health education positively impacts student health in a variety of ways. Students who participate in these programs are more likely to: 6-11

- Delay initiation of sexual intercourse

- Have fewer sex partners

- Have fewer experiences of unprotected sex

- Increase their use of protection, specifically condoms

- Improve their academic performance.

In addition to providing knowledge and skills to address sexual behavior , quality sexual health education can be tailored to include information on high-risk substance use * , suicide prevention, and how to keep students from committing or being victims of violence—behaviors and experiences that place youth at risk for poor physical and mental health and poor academic outcomes.

*High-risk substance use is any use by adolescents of substances with a high risk of adverse outcomes (i.e., injury, criminal justice involvement, school dropout, loss of life). This includes misuse of prescription drugs, use of illicit drugs (i.e., cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, inhalants, hallucinogens, or ecstasy), and use of injection drugs (i.e., drugs that have a high risk of infection of blood-borne diseases such as HIV and hepatitis).

What does delivering sexual health education look like in action?

To successfully put quality sexual health education into practice, schools need supportive policies, appropriate content, trained staff, and engaged parents and communities.

Schools can put these four elements in place to support sex ed.

- Implement policies that foster supportive environments for sexual health education.

- Use health content that is medically accurate, developmentally appropriate, culturally inclusive, and grounded in science.

- Equip staff with the knowledge and skills needed to deliver sexual health education.

- Engage parents and community partners.

Include enough time during professional development and training for teachers to practice and reflect on what they learned (essential knowledge and skills) to support their sexual health education instruction.

By law, if your school district or school is receiving federal HIV prevention funding, you will need an HIV Materials Review Panel (HIV MRP) to review all HIV-related educational and informational materials.

This review panel can include members from your School Health Advisory Councils, as shared expertise can strengthen material review and decision making.

For More Information

Learn more about delivering quality sexual health education in the Program Guidance .

Check out CDC’s tools and resources below to develop, select, or revise SHE curricula.

- Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool (HECAT), Module 6: Sexual Health [PDF – 70 pages] . This module within CDC’s HECAT includes the knowledge, skills, and health behavior outcomes specifically aligned to sexual health education. School and community leaders can use this module to develop, select, or revise SHE curricula and instruction.

- Developing a Scope and Sequence for Sexual Health Education [PDF – 17 pages] .This resource provides an 11-step process to help schools outline the key sexual health topics and concepts (scope), and the logical progression of essential health knowledge, skills, and behaviors to be addressed at each grade level (sequence) from pre-kindergarten through the 12th grade. A developmental scope and sequence is essential to developing, selecting, or revising SHE curricula.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool, 2021 , Atlanta: CDC; 2021.

- Goldfarb, E. S., & Lieberman, L. D. (2021). Three decades of research: The case for comprehensive sex education. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 13-27.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Characteristics of an Effective Health Education Curriculum .

- Pampati, S., Johns, M. M., Szucs, L. E., Bishop, M. D., Mallory, A. B., Barrios, L. C., & Russell, S. T. (2021). Sexual and gender minority youth and sexual health education: A systematic mapping review of the literature. Journal of Adolescent Health , 68 (6), 1040-1052.

- Szucs, L. E., Demissie, Z., Steiner, R. J., Brener, N. D., Lindberg, L., Young, E., & Rasberry, C. N. (2023). Trends in the teaching of sexual and reproductive health topics and skills in required courses in secondary schools, in 38 US states between 2008 and 2018. Health Education Research , 38 (1), 84-94.

- Coyle, K., Anderson, P., Laris, B. A., Barrett, M., Unti, T., & Baumler, E. (2021). A group randomized trial evaluating high school FLASH, a comprehensive sexual health curriculum. Journal of Adolescent Health , 68 (4), 686-695.

- Marseille, E., Mirzazadeh, A., Biggs, M. A., Miller, A. P., Horvath, H., Lightfoot, M.,& Kahn, J. G. (2018). Effectiveness of school-based teen pregnancy prevention programs in the USA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 19(4), 468-489.

- Denford, S., Abraham, C., Campbell, R., & Busse, H. (2017). A comprehensive review of reviews of school-based interventions to improve sexual-health. Health psychology review, 11(1), 33-52.

- Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R. The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: Two systematic reviews for the guide to community preventive services. Am J Prev Med 2012;42(3):272–94.

- Mavedzenge SN, Luecke E, Ross DA. Effective approaches for programming to reduce adolescent vulnerability to HIV infection, HIV risk, and HIV-related morbidity and mortality: A systematic review of systematic reviews. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:S154–69.

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Comprehensive sexuality education: For healthy, informed and empowered learners

Did you know that only 37% of young people in sub-Saharan Africa can demonstrate comprehensive knowledge about HIV prevention and transmission? And two out of three girls in many countries lack the knowledge they need as they enter puberty and begin menstruating? Early marriage and early and unintended pregnancy are global concerns for girls’ health and education: in East and Southern Africa pregnancy rates range 15-25%, some of the highest in the world. These are some of the reasons why quality comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is essential for learners’ health, knowledge and empowerment.

What is comprehensive sexuality education or CSE?

Comprehensive sexuality education - or the many other ways this may be referred to - is a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that empowers them to realize their health, well-being and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives.

CSE presents sexuality with a positive approach, emphasizing values such as respect, inclusion, non-discrimination, equality, empathy, responsibility and reciprocity. It reinforces healthy and positive values about bodies, puberty, relationships, sex and family life.

How can CSE transform young people’s lives?

Too many young people receive confusing and conflicting information about puberty, relationships, love and sex, as they make the transition from childhood to adulthood. A growing number of studies show that young people are turning to the digital environment as a key source of information about sexuality.

Applying a learner-centered approach, CSE is adapted to the age and developmental stage of the learner. Learners in lower grades are introduced to simple concepts such as family, respect and kindness, while older learners get to tackle more complex concepts such as gender-based violence, sexual consent, HIV testing, and pregnancy.

When delivered well and combined with access to necessary sexual and reproductive health services, CSE empowers young people to make informed decisions about relationships and sexuality and navigate a world where gender-based violence, gender inequality, early and unintended pregnancies, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections still pose serious risks to their health and well-being. It also helps to keep children safe from abuse by teaching them about their bodies and how to change practices that lead girls to become pregnant before they are ready.

Equally, a lack of high-quality, age-appropriate sexuality and relationship education may leave children and young people vulnerable to harmful sexual behaviours and sexual exploitation.

What does the evidence say about CSE?

The evidence on the impact of CSE is clear:

- Sexuality education has positive effects, including increasing young people’s knowledge and improving their attitudes related to sexual and reproductive health and behaviors.

- Sexuality education leads to learners delaying the age of sexual initiation, increasing the use of condoms and other contraceptives when they are sexually active, increasing their knowledge about their bodies and relationships, decreasing their risk-taking, and decreasing the frequency of unprotected sex.

- Programmes that promote abstinence as the only option have been found to be ineffective in delaying sexual initiation, reducing the frequency of sex or reducing the number of sexual partners. To achieve positive change and reduce early or unintended pregnancies, education about sexuality, reproductive health and contraception must be wide-ranging.

- CSE is five times more likely to be successful in preventing unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections when it pays explicit attention to the topics of gender and power

- Parents and family members are a primary source of information, values formation, care and support for children. Sexuality education has the most impact when school-based programmes are complemented with the involvement of parents and teachers, training institutes and youth-friendly services .

How does UNESCO work to advance learners' health and education?

Countries have increasingly acknowledged the importance of equipping young people with the knowledge, skills and attitudes to develop and sustain positive, healthy relationships and protect themselves from unsafe situations.

UNESCO believes that with CSE, young people learn to treat each other with respect and dignity from an early age and gain skills for better decision making, communications, and critical analysis. They learn they can talk to an adult they trust when they are confused about their bodies, relationships and values. They learn to think about what is right and safe for them and how to avoid coercion, sexually transmitted infections including HIV, and early and unintended pregnancy, and where to go for help. They learn to identify what violence against children and women looks like, including sexual violence, and to understand injustice based on gender. They learn to uphold universal values of equality, love and kindness.

In its International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education , UNESCO and other UN partners have laid out pathways for quality CSE to promote health and well-being, respect for human rights and gender equality, and empower children and young people to lead healthy, safe and productive lives. An online toolkit was developed by UNESCO to facilitate the design and implementation of CSE programmes at national level, as well as at local and school level. A tool for the review and assessment of national sexuality education programmes is also available. Governments, development partners or civil society organizations will find this useful. Guidance for delivering CSE in out-of-school settings is also available.

Through its flagship programme, Our rights, Our lives, Our future (O3) , UNESCO has reached over 30 million learners in 33 countries across sub-Saharan Africa with life skills and sexuality education, in safer learning environments. O3 Plus is now also reaching and supporting learners in higher education institutions.

To strengthen coordination among the UN community, development partners and civil society, UNESCO is co-convening the Global partnership forum on CSE together with UNFPA. With over 65 organizations in its fold, the partnership forum provides a structured platform for intensified collaboration, exchange of information and good practices, research, youth advocacy and leadership, and evidence-based policies and programmes.

Good quality CSE delivery demands up to date research and evidence to inform policy and implementation . UNESCO regularly conducts reviews of national policies and programmes – a report found that while 85% of countries have policies that are supportive of sexuality education, significant gaps remain between policy and curricula reviewed. Research on the quality of sexuality education has also been undertaken, including on CSE and persons with disabilities in Asia and East and Southern Africa .

How are young people and CSE faring in the digital space?

More young people than ever before are turning to digital spaces for information on bodies, relationships and sexuality, interested in the privacy and anonymity the online world can offer. UNESCO found that, in a year, 71% of youth aged 15-24 sought sexuality education and information online.

With the rapid expansion in digital information and education, the sexuality education landscape is changing . Children and young people are increasingly exposed to a broad range of content online some of which may be incomplete, poorly informed or harmful.

UNESCO and its Institute of Information Technologies in Education (IITE) work with young people and content creators to develop digital sexuality education tools that are of good quality, relevant and include appropriate content. More research and investment are needed to understand the effectiveness and impact of digital sexuality education, and how it can complement curriculum-based initiatives. Part of the solution is enabling young people themselves to take the lead on this, as they are no longer passive consumers and are thinking in sophisticated ways about digital technology.

A foundation for life and love

- Safe, seen and included: report on school-based sexuality education

- International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education

- Safe, seen and included: inclusion and diversity within sexuality education; briefing note

- Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) country profiles

- Evidence gaps and research needs in comprehensive sexuality education: technical brief

- The journey towards comprehensive sexuality education: global status report

- Definition of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) thematic indicator 4.7.2: Percentage of schools that provided life skills-based HIV and sexuality education within the previous academic year

- From ideas to action: addressing barriers to comprehensive sexuality education in the classroom

- Facing the facts: the case for comprehensive sexuality education

- UNESCO strategy on education for health and well-being

- UNESCO Health and education resource centre

- Campaign: A foundation for life and love

- UNESCO’s work on health and education

Related items

- Health education

- Sex education

What is comprehensive sexuality education?

Comprehensive sexuality education ( CSE ) is a curriculum -based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical, and social aspects of sexuality. It aims to equip children and young people with knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that will empower them to: realize their health, well-being, and dignity; develop respectful social and sexual relationships; consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others; and understand and ensure the protection of their rights throughout their lives.

[Source: UNESCO. 2017. International technical guidance on sexuality education, pp.16-17.]

Depending on the country or region, CSE may go by other names. It may be referred to as ‘ life skills ’, ‘ family life ’, or ‘ HIV ’ education . It is sometimes called ‘holistic sexuality education’. It is important to confirm with ministries what they use to describe CSE, particularly as context-based terms can inform the most effective approach to take when partnering with and supporting these ministries.

- delivered in formal and non-formal settings , in school or out of school ;

- scientifically accurate , based on research, facts, and evidence;

- incremental , starting at an early age with foundational content and skills, with new information building upon previous learning, using a spiral-curriculum approach that returns to the same topics at a more advanced level each year;

- age- and developmentally appropriate , with content and skills growing in abstractness and explicitness with the age and developmental level of the learners; it also must accommodate developmental diversity, adapting for learners with cognitive and emotional development differences;

- curriculum-based , following a written curriculum that includes key teaching and learning objectives, and the delivery of clear content and skills in a structured way;

- comprehensive , and about much more than just sexual behaviours.

The comprehensive aspect of CSE refers to the breadth, depth, and consistency of topics, as opposed to one-off lessons or interventions. CSE addresses sexual and reproductive health issues, including, but not limited to:

- sexual and reproductive anatomy and physiology;

- puberty and menstruation;

- reproduction, contraception , pregnancy, and childbirth;

- STIs, including HIV and AIDS .

CSE also addresses the psychological, social, and emotional issues relating to these topics, including those that may be challenging in some social and cultural contexts. It supports learners’ empowerment by improving their analytical, communication, and other life skills for health and well-being in relation to:

- human rights,

- a healthy and respectful family life and interpersonal relationships,

- personal and shared values,

- cultural and social norms,

- gender equality,

- non-discrimination,

- sexual behaviour,

- gender-based and other violence,

- consent and bodily integrity,

- sexual abuse and harmful practices such as child , early, and forced marriage, and female genital mutilation/cutting.

Key values of CSE

CSE builds on and promotes universal human rights for all, including children and young people. It emphasizes all persons’ rights to health, education, information equality, and non-discrimination. It raises awareness among young people that they have their own rights, and that they must acknowledge and respect the rights of others, and advocate for those whose rights are violated.

Integrating a gender perspective throughout CSE curricula is integral to effective CSE programmes. CSE analyses how gender norms can influence inequality, and how inequality can affect the overall health and well-being of children and young people, as well as the efforts to prevent issues such as HIV, STIs, early and unintended pregnancies, and gender-based violence . CSE contributes to gender equality by building awareness of the centrality and diversity of gender identities and expressions in people’s lives; examining gender norms shaped by cultural, social and biological differences and similarities; and by encouraging the creation of respectful and equitable relationships based on empathy and understanding.

CSE must be delivered in the context of the range of values, beliefs, and experiences that exist even within a single culture. It enables learners to examine, understand, and challenge the ways in which cultural structures, norms, and behaviours affect their choices and relationships within a variety of settings.

CSE impacts whole cultures and communities, not simply individual learners. It can contribute to the development of a fair and compassionate society by empowering individuals and communities, promoting critical thinking skills, and strengthening young people’s sense of citizenship. It empowers young people to take responsibility for their own decisions and behaviours, and how they may affect others. It builds the skills and attitudes that enable young people to treat others with respect, acceptance, tolerance, and empathy, regardless of their ethnicity, race, social, economic, or immigration status, religion, disability, sexual orientation , gender identity or expression, or sex characteristics.

CSE teaches young people to reflect on the information around them in order to make informed decisions, communicate and negotiate effectively, and develop assertiveness rather than passivity or aggression. These skills foster the creation of respectful and healthy relationships with family members, peers, friends, and romantic or sexual partners.

[Source: UNESCO. 2017. International technical guidance on sexuality education, pp 16-17.]

‘ Sexuality ’ is defined as ‘a core dimension of being human which includes: the understanding of, and relationship to, the human body; emotional attachment and love; sex; gender; gender identity; sexual orientation; sexual intimacy; pleasure and reproduction. Sexuality is complex and includes biological, social, psychological, spiritual, religious, political, legal, historic, ethical and cultural dimensions that evolve over a lifespan’.

[Source: UNESCO. 2017. International technical guidance on sexuality education, p.17.]

The word ‘sexuality’ has different meanings in different languages and in different cultural contexts. Taking into account a number of variables and the diversity of meanings in different languages, the following aspects of sexuality need to be considered in the context of CSE:

- Sexuality refers to the individual and social meanings of interpersonal and sexual relationships, in addition to biological aspects. It is a subjective experience and a part of the human need for both intimacy and privacy.

- Simultaneously, sexuality is a social construct, most easily understood within the variability of beliefs, practices, behaviours and identities. ‘Sexuality is shaped at the level of individual practices and cultural values and norms’ (Weeks, 2011).

- Sexuality is linked to power. The ultimate boundary of power is the possibility of controlling one’s own body. CSE can address the relationship between sexuality, gender and power, and its political and social dimensions. This is particularly appropriate for older learners.

- The expectations that govern sexual behaviour differ widely across and within cultures. Certain behaviours are seen as acceptable and desirable, while others are considered unacceptable. This does not mean that these behaviours do not occur, or that they should be excluded from discussion within the context of sexuality education.

- Sexuality is present throughout life, manifesting in different ways and interacting with physical, emotional and cognitive maturation. Education is a major tool for promoting sexual well-being and preparing children and young people for healthy and responsible relationships at the different stages of their lives.

[Source: UNESCO. 2017. International technical guidance on sexuality education, p. 17.]

When viewed holistically and positively:

- Sexual health is about well-being, not merely the absence of disease.

- Sexual health involves respect, safety and freedom from discrimination and violence.

- Sexual health depends on the fulfilment of certain human rights.

- Sexual health is relevant throughout the individual’s lifespan, not only to those in the reproductive years, but also to both the young and the elderly.

- Sexual health is expressed through diverse sexualities and forms of sexual expression.

- Sexual health is critically influenced by gender norms, roles, expectations and power dynamics.

- Sexual health needs to be understood within specific social, economic and political contexts.

- Characteristics of effective CSE programmes

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Sex Education in America: the Good, the Bad, the Ugly

Please try again

The debate over the best way to teach sexual health in the U.S. continues to rage on, but student voice is often left out of the conversation when schools are deciding on what to teach. So Myles and PBS NewsHour Student Reporters from Oakland Military Institute investigate the pros and cons of the various approaches to sex ed and talk to students to find out how they feel about their sexual health education.

TEACHERS: Guide your students to practice civil discourse about current topics and get practice writing CER (claim, evidence, reasoning) responses. Explore lesson supports.

What is comprehensive sex education?

Comprehensive sex education teaches that not having sex is the best way to avoid STIs and unintended pregnancies, but it also includes medically accurate information about STI prevention, reproductive health, as well as discussions about healthy relationships, consent, gender identity, LGBTQ issues and more. What is sexual risk avoidance education? Sexual risk avoidance education is also known as abstinence only or abstinence-leaning education. It generally teaches that not having sex is the only morally acceptable, safe and effective way to prevent pregnancy and STIs — some programs don’t talk about birth control or condoms– unless it is to emphasize failure rates.

What are the main arguments for comprehensive sex education?

“Comprehensive sex ed” is based on the idea that public health improves when students have a right to learn about their sexuality and to make responsible decisions about it. Research shows it works to reduce teen pregnancies, delay when teens become sexually active and reduce the number of sexual partners teens have.

What are the main arguments against comprehensive sex education?

Some people, particularly parents and religious groups, take issue with comprehensive sex ed because they believe it goes against their cultural or religious values, and think that it can have a corrupting influence on kids. They say that by providing teens with this kind of information you are endorsing and encouraging sex and risk taking. Some opponents also argue that this type of information should be left up to parents to teach their kids about and shouldn’t be taught in schools.

State Laws and Policies Across the US (SIECUS)

STDs Adolescents and Young Adults (CDC)

Myths and Facts about Comprehensive Sex Education (Advocates for Youth)

Abstinence-Only and Comprehensive Sex Education and the Initiation of Sexual Activity and Teen Pregnancy (Journal of Adolescent Health)

Abstinence-Only-Until Marriage: An Updated Review of US Policies and Programs and Their Impact (Journal of Adolescent Health)

Sexual Risk Avoidance Education: What you need to know (ASCEND)

We partnered with PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs for this episode. Check out their journalism resources for students: https://studentreportinglabs.org/

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.

Sex Education that Goes Beyond Sex

- Posted November 28, 2018

- By Grace Tatter

Historically, the measure of a good sex education program has been in the numbers: marked decreases in the rates of sexually transmitted diseases, teen pregnancies, and pregnancy-related drop-outs. But, increasingly, researchers, educators, and advocates are emphasizing that sex ed should focus on more than physical health. Sex education, they say, should also be about relationships.

Giving students a foundation in relationship-building and centering the notion of care for others can enhance wellbeing and pave the way for healthy intimacy in the future, experts say. It can prevent or counter gender stereotyping and bias. And it could minimize instances of sexual harassment and assault in middle and high school — instances that may range from cyberbullying and stalking to unwanted touching and nonconsensual sex. A recent study from Columbia University's Sexual Health Initative to Foster Transformation (SHIFT) project suggests that comprehensive sex education protects students from sexual assault even after high school.

If students become more well-practiced in thinking about caring for one another, they’ll be less likely to commit — and be less vulnerable to — sexual violence, according to this new approach to sex ed. And they’ll be better prepared to engage in and support one another in relationships, romantic and otherwise, going forward.

Giving students a foundation in relationship-building can enhance wellbeing and pave the way for healthy intimacy in the future, experts say. It can also prevent or counter gender stereotyping, and it could minimize instances of sexual harassment and assault in middle and high school.

Introducing Ethics Into Sex Ed

Diving into a conversation even tangentially related to sex with a group of 20 or so high school students isn’t easy. Renee Randazzo helped researcher Sharon Lamb pilot the Sexual Ethics and Caring Curriculum while a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She recalls boys snickering during discussions about pornography and objectification. At first, it was hard for students to be vulnerable.

But the idea behind the curriculum is that tough conversations are worth having. Simply teaching students how to ask for consent isn’t enough, says Lamb, a professor of counseling psychology at UMass Boston, who has been researching the intersection between caring relationships, sex, and education for decades. Students also to have understand why consent is important and think about consent in a variety of contexts. At the heart of that understanding are questions about human morality, how we relate to one another, and what we owe to one another. In other words, ethics.

“When I looked at what sex ed was doing, it wasn’t only a problem that kids weren’t getting the right facts,” Lamb says. “It was a problem that they weren’t getting the sex education that would make them treat others in a caring and just way.”

She became aware that when schools were talking about consent — if they were at all — it was in terms of self-protection. The message was: Get consent so you don’t get in trouble.