- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Family Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, what are the aims of the research project, what level of detail is required, who should do the transcribing, what contextual detail is necessary to interpret data, how should data be represented, what equipment is needed, declaration.

- < Previous

First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing

Bailey J. First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing. Family Practice 2008; 25: 127–131.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Julia Bailey, First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing, Family Practice , Volume 25, Issue 2, April 2008, Pages 127–131, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn003

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Qualitative research in primary care deepens understanding of phenomena such as health, illness and health care encounters. Many qualitative studies collect audio or video data (e.g. recordings of interviews, focus groups or talk in consultation), and these are usually transcribed into written form for closer study. Transcribing appears to be a straightforward technical task, but in fact involves judgements about what level of detail to choose (e.g. omitting non-verbal dimensions of interaction), data interpretation (e.g. distinguishing ‘I don't, no’ from ‘I don't know’) and data representation (e.g. representing the verbalization ‘hwarryuhh’ as ‘How are you?’).

Representation of audible and visual data into written form is an interpretive process which is therefore the first step in analysing data. Different levels of detail and different representations of data will be required for projects with differing aims and methodological approaches. This article is a guide to practical and theoretical considerations for researchers new to qualitative data analysis. Data examples are given to illustrate decisions to be made when transcribing or assigning the task to others.

Qualitative research can explore the complexity and meaning of social phenomena, 1 , 2 for example patients' experiences of illness 3 and the meanings of apparently irrational behaviour such as unsafe sex. 4 Data for qualitative study may comprise written texts (e.g. documents or field notes) and/or audible and visual data (e.g. recordings of interviews, focus groups or consultations). Recordings are transcribed into written form so that they can be studied in detail, linked with analytic notes and/or coded. 5

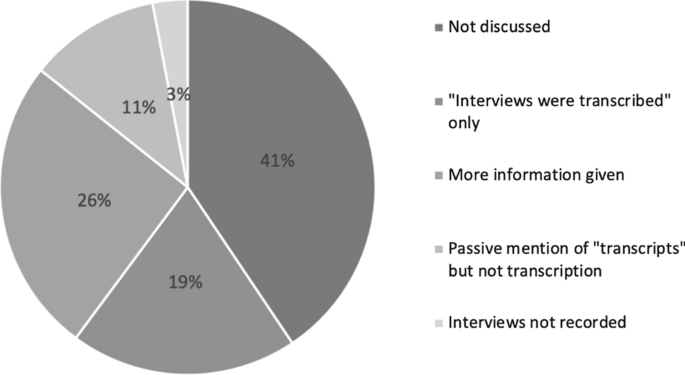

Word limits in medical journals mean that little detail is usually given about how transcribing is actually done. Authors' descriptions in papers convey the impression that transcribing is a straightforward technical task, summed up using terms such as ‘verbatim transcription’. 6 However, representing audible talk as written words requires reduction, interpretation and representation to make the written text readable and meaningful. 7 , 8 This article unpicks some of the theoretical and practical decisions involved in transcribing, for researchers new to qualitative data analysis.

Researchers' methodological assumptions and disciplinary backgrounds influence what are considered relevant data and how data should be analysed. To take an example, talk between hospital consultants and medical students could be studied in many different ways: the transcript of a teaching session could be analysed thematically, coding the content (topics) of talk. Analysis could also look at the way that developing an identity as a doctor involves learning to use language in particular ways, for example, using medical terminology in genres such as the ‘case history’. 9 The same data could be analysed to explore the construction of ‘truth’ in medicine: for example, a doctor saying ‘the patient's blood pressure is 120/80’ frames this statement as an objective, quantifiable, scientific truth. In contrast, formulating a patient's medical history with statements such as ‘she reports a pain in the left leg’ or ‘she denies alcohol use’ frames the patient's account as less trustworthy than the doctor's observations. 10 The aims of a project and methodological assumptions have implications for the form and content of transcripts since different features of data will be of analytic interest. 7

Making recordings involves reducing the original data, for example, selecting particular periods of time and/or particular camera angles. Selecting which data have significance reflects underlying assumptions about what count as data for a particular project, for example, whether social talk at the beginning and end of an interview is to be included or the content of a telephone call which interrupts a consultation.

Visual data

Verbal and non-verbal interaction together shape communicative meaning. 11 The aims of the project should dictate whether visual information is necessary for data interpretation, for example, room layout, body orientation, facial expression, gesture and the use of equipment in consultation. 12 However, visual data are more difficult to process since they take a huge length of time to transcribe, and there are fewer conventions for how to represent visual elements on a transcript. 5

Capturing how things are said

The meanings of utterances are profoundly shaped by the way in which something is said in addition to what is said. 13 , 14 Transcriptions need to be very detailed to capture features of talk such as emphasis, speed, tone of voice, timing and pauses but these elements can be crucial for interpreting data. 7

Dr 9: I would suggest yes paracetamol is a good symptomatic treatment, and you'll be fine Pt K: fine, okay, well, thank you very much.

Dr 9: (..) I would suggest (..) yes paracetamol or ibuprofen is a good (..) symptomatic treatment (..) um (.) (slapping hands on thighs) and you'll be fine Pt K: fine (..) okay (.) well (..) (shrugging shoulders and laughing) thank you very much

In the second representation of this interaction, both speakers pause frequently. The doctor slaps his thigh and uses the idiom ‘you'll be fine’ to wrap up his advice giving. In response, Patient K is hesitant and he uses the mitigation ‘well’, shrugs his shoulders and laughs, suggesting turbulence or difficulty in interaction. 15 Although the patient's words seem to indicate agreement, the way these words are said seem to indicate the opposite. 16

Dr 5: So let's just go back to this. So, so you've had this for a few weeks Pt F: yes

Dr 5: .hhh so let's just go back to this (.) so (..) so you've had this for a few w ee ks Pt F: yes (1.0) (left hand on throat, stroking with fingers)

Dr 5: I must ask you (.) why have you come in tod a y because it is a Saturday morning (1.0) it's for u rgent cases only that really have just st a rted Pt F: Yes because it has been troubling me since last last night (left hand still on neck)

This more detailed level of transcribing facilitates analysis of the social relationship between doctor and patient; in this example, the consequences for the doctor–patient interaction of consulting in an urgent surgery with ‘minor’ symptoms. 16

Data must inevitably be reduced in the process of transcribing, since interaction is hugely complex. Decisions therefore need to be made about which features of interaction to transcribe: the level of detail necessary depends upon the aims of a research project, and there is a balance to be struck between readability and accuracy of a transcript. 18

Transcribing is often delegated to a junior researcher or medical secretary for example, but this can be a mistake if the transcriber is inadequately trained or briefed. Transcription involves close observation of data through repeated careful listening (and/or watching), and this is an important first step in data analysis. This familiarity with data and attention to what is actually there rather than what is expected can facilitate realizations or ideas which emerge during analysis. 1 Transcribing takes a long time (at least 3 hours per hour of talk and up to 10 hours per hour with a fine level of detail including visual detail) 5 and this should be allowed for in project time plans, budgeting for researchers’ time if they will be doing the transcribing.

Recordings may be difficult to understand because of the recording quality (e.g. quiet volume, overlaps in speech, interfering noise) and differing accents or styles of speech. Utterances are interpretable through knowledge of their local context (i.e. in relation to what has gone before and what follows), 8 for example, allowing differentiation between ‘I don't, no’ and ‘I don't know'. Interaction is also understood in wider context such as understanding questions and responses to be part of an ‘interview’ or ‘consultation’ genre with particular expectations for speaker roles and the form and content of talk. 19 For example, the question ‘how are you?’ from a patient in consultation would be interpreted as a social greeting, while the same question from a doctor would be taken as an invitation to recount medical problems. 14 Contextual information about the research helps the transcriber to interpret recordings (if they are not the person who collected the data), for example, details about the project aims, the setting and participants and interview topic guides if relevant.

Dr 1: so what are your symptoms since yesterday (..) the aches Pt B: aches ere (..) in me arm (..) sneezing (..) edache Dr 1: ummm (..) okay (..) and have you tried anything for this (.) at all? Pt B: no (..) I ain't a believer of me- (.) medicine to tell you the truth

Although this attempts to represent linguistic variety, using a more literal spelling is difficult to read and runs the risk of portraying respondents as inarticulate and/or uneducated. 20 Even using standard written English, transcribed talk appears faltering and inarticulate. For example, verbal interaction includes false starts, repetitions, interruptions, overlaps, in- and out-breaths, coughs, laughs and encouraging noises (such as ‘mm’), and these features may be omitted to avoid cluttering the text. 18

If talk is mediated via an interpreter, decisions must be made about how to represent translation on a transcript, 8 for example, whether to translate ‘literally’, and then to interpret the meaning in terms of the second language and culture. For example, from French to English, ‘j'ai mal au coeur’ translates literally as ‘I have bad in the heart’, interpreted in English as ‘I feel sick’. Translation therefore adds an additional layer of interpretation to the transcribing process.

Written representations reflect researchers’ interpretations. For example, laughter could be transcribed as ‘he he he', ‘laughter (2 seconds)’, ‘nervous laughter’, ‘quiet laughter’ or ‘giggling’ and these representations convey different interpretations. The layout on paper and labelling also reflect analytic assumptions about data. 20 For example, labelling speakers as ‘patient’ and ‘doctor’ implies that their respective roles in a medical encounter are more salient than other attributes such as ‘man’, ‘mother’, ‘Spanish speaker’ or ‘advice giver’. Talk is often presented in speech turns, with a new line for the next speaker (as in the data examples given), but could also be laid out in a timeline, in columns or in stanzas like poetry, for example. 7 Transcripts are not therefore neutral records of events, but reflect researchers’ interpretations of data.

Presenting quotations in a research paper involves further steps in reduction and representation through the choice of which data to present and what to highlight. There is debate about what counts as relevant context in qualitative research. 21 , 22 For example, studies usually describe the setting in which data were collected and demographic features of respondents such as their age and gender, but relevant contextual information could also include historical, political and policy context, participants’ physical appearance, recent news events, details of previous meetings and so on. 23 Authors’ decisions on which data and what contextual information to present will lead to different framing of data.

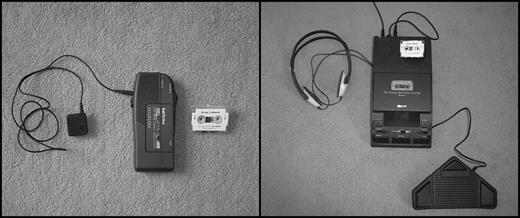

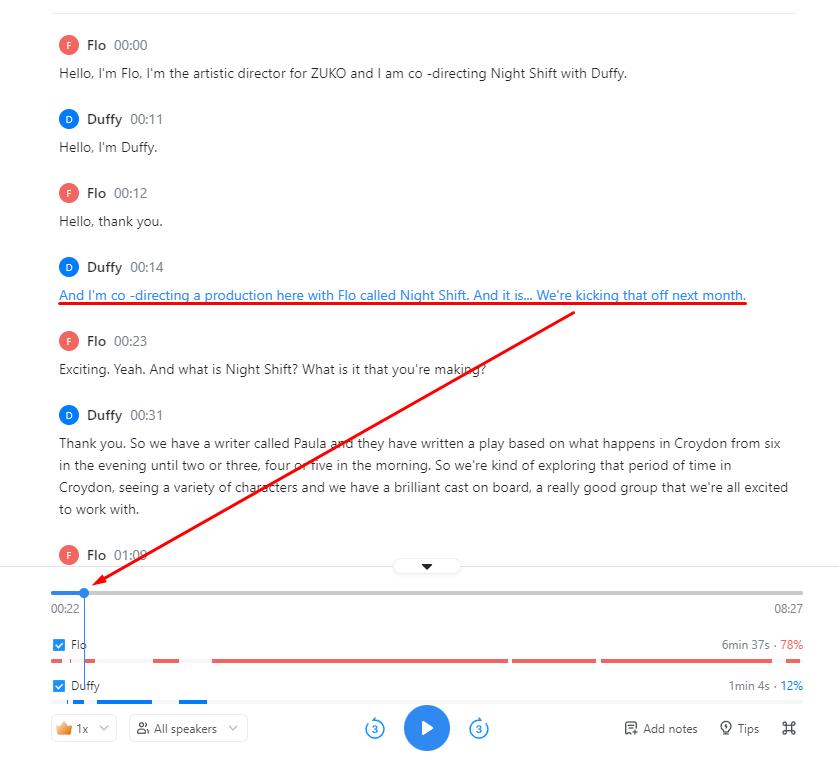

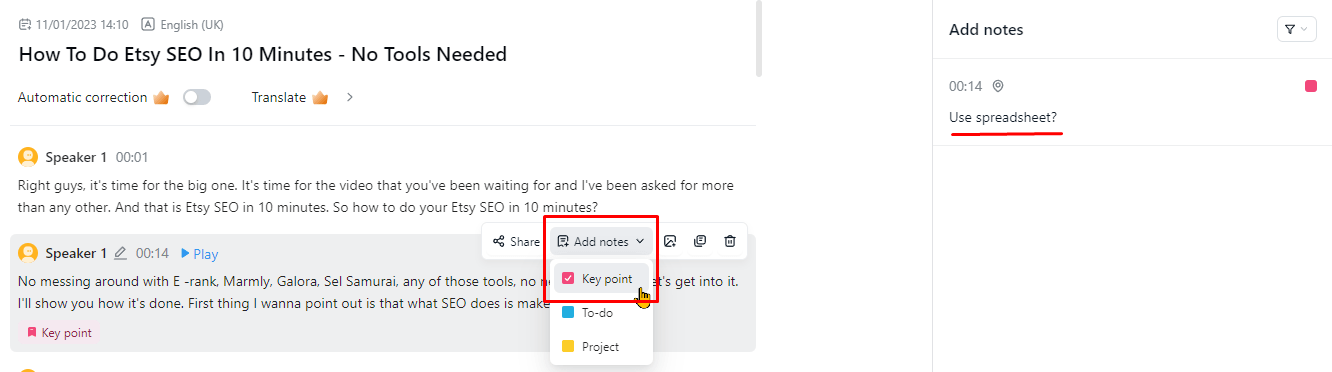

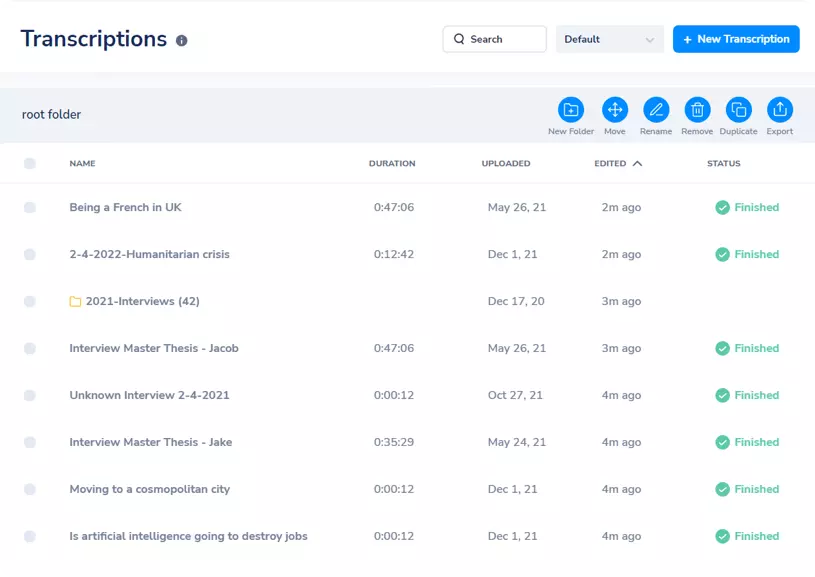

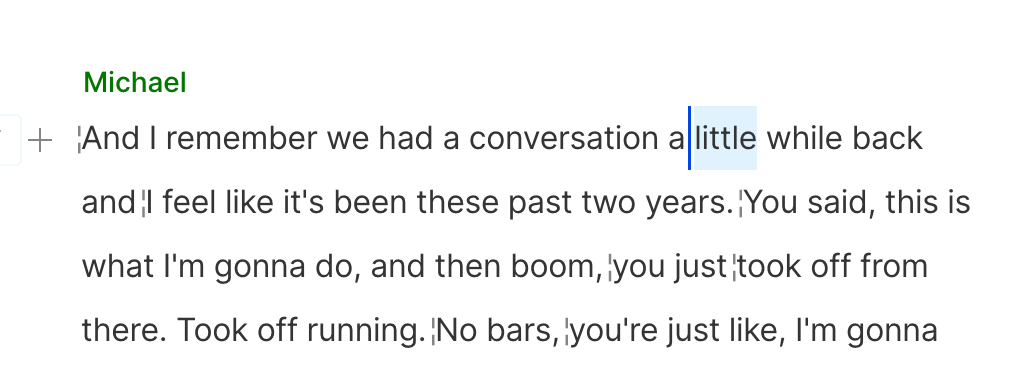

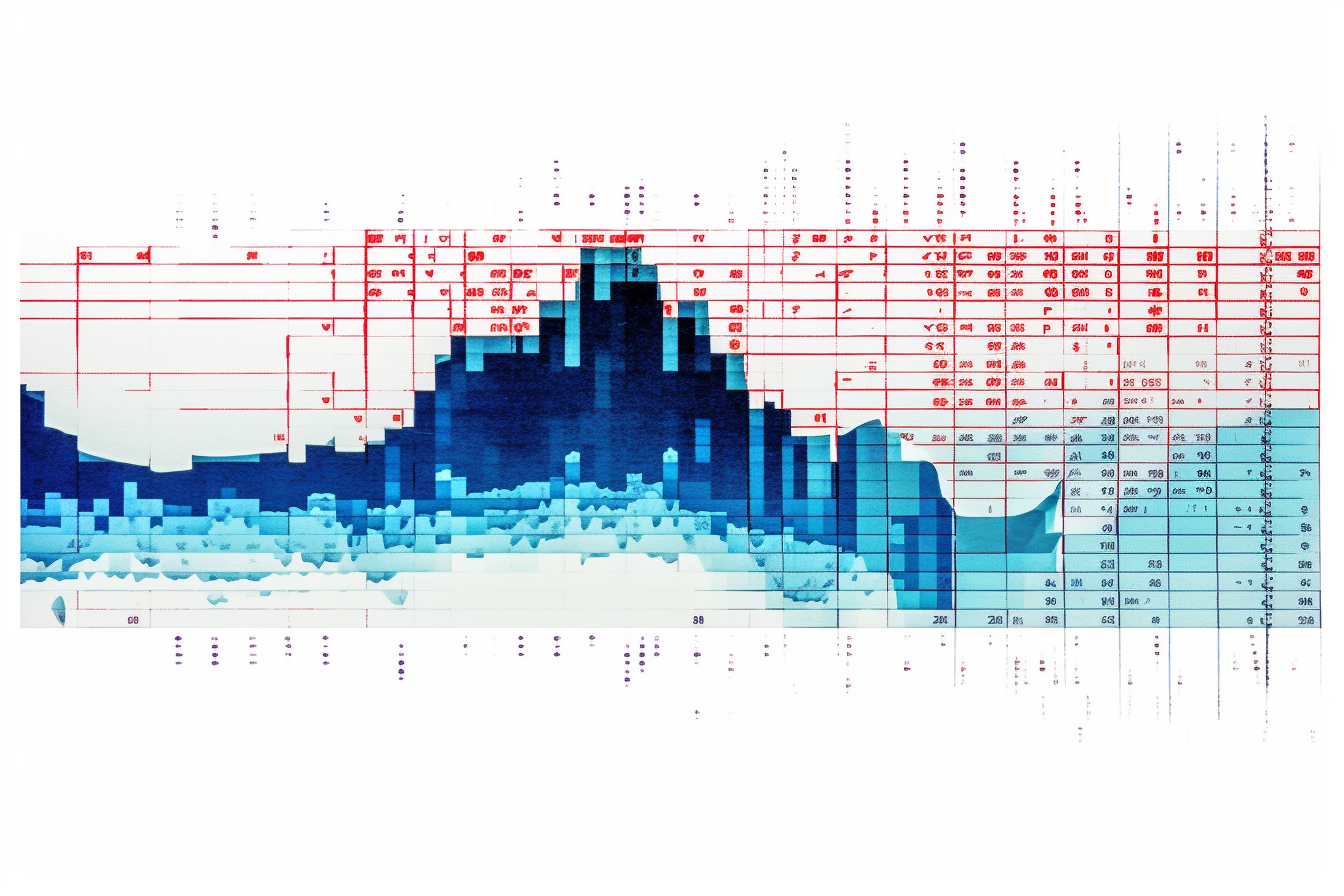

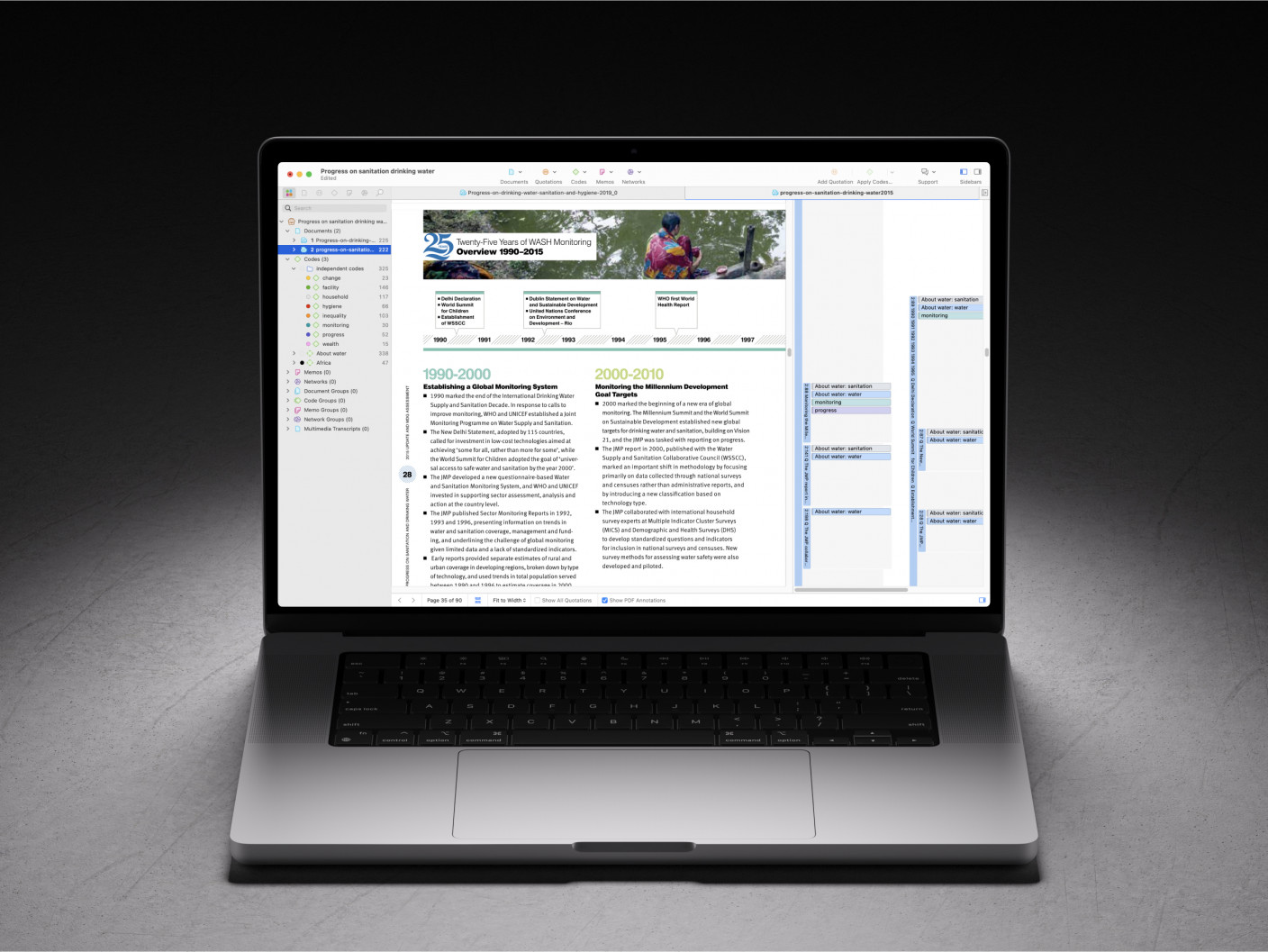

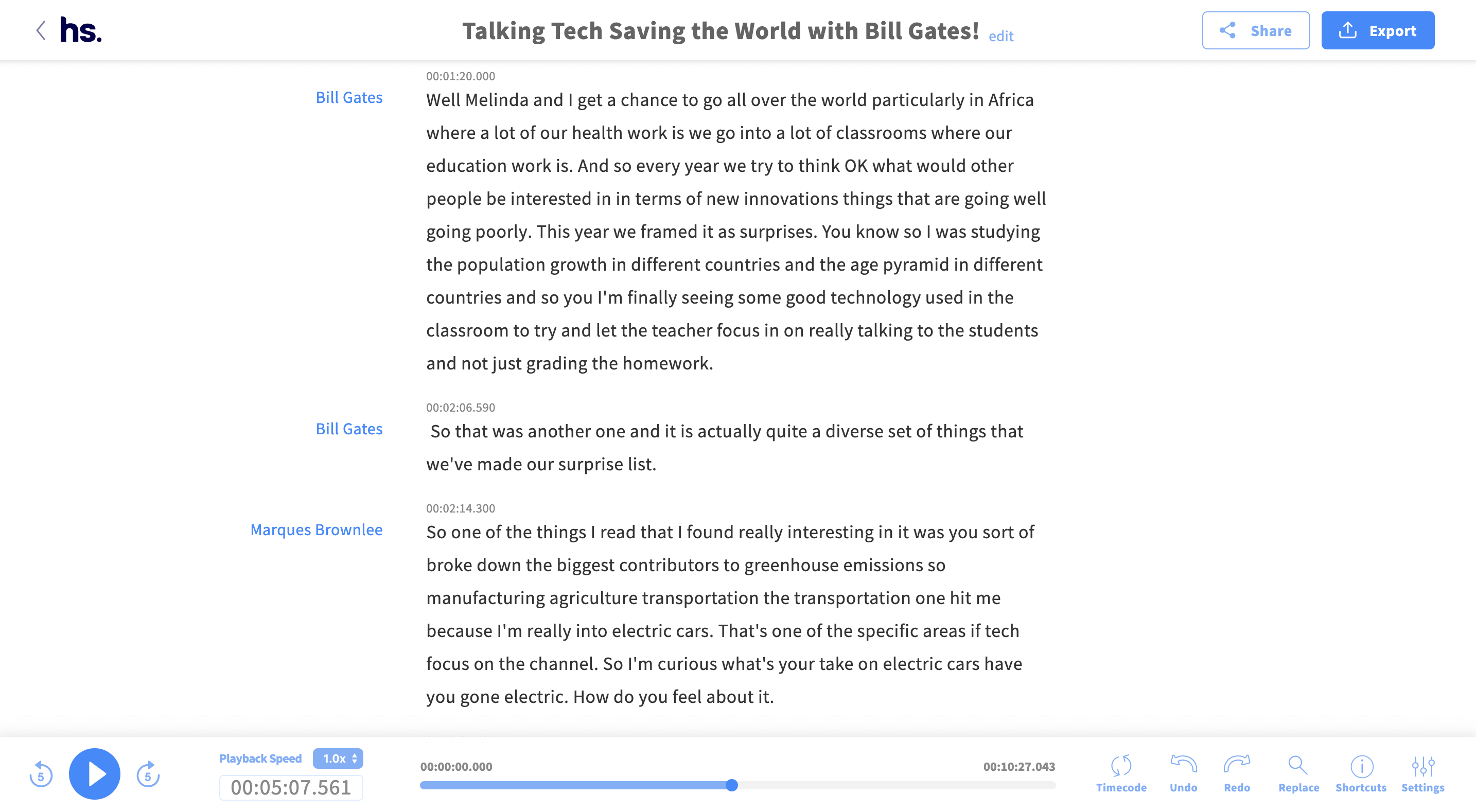

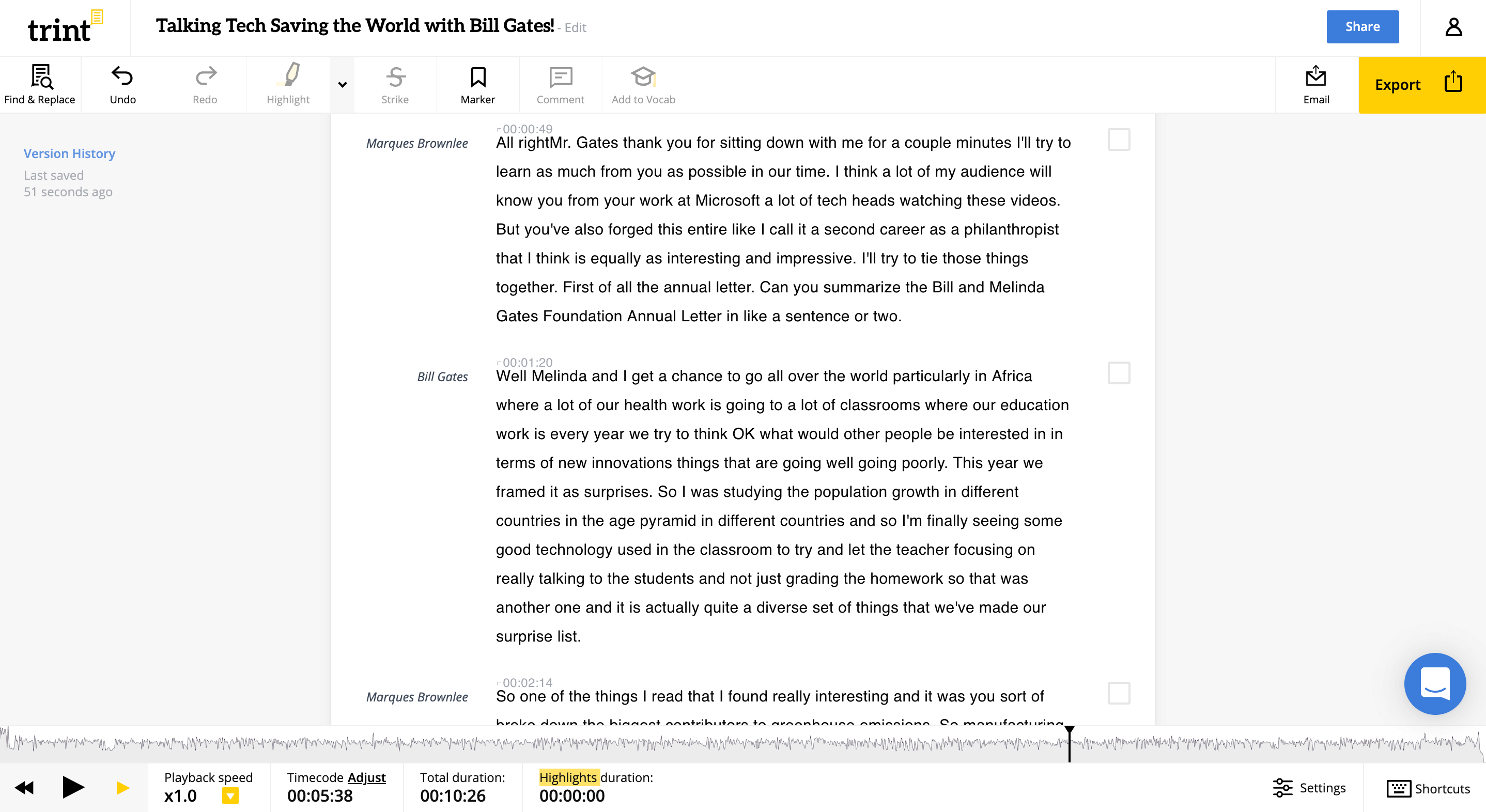

Decisions about the level of detail needed for a project will inform whether video or audio recordings are needed. 24 Taking notes instead of making recordings is not sufficiently accurate or detailed for most qualitative projects. Digital audio and video recorders are rapidly replacing analogue equipment: digital recordings are generally better quality, but require computer software to store and process, and digital video files take up huge quantities of computer memory. It is usually necessary to playback recordings repeatedly: a foot-controlled transcription machine facilitates this for analogue audio tapes (see Fig. 1 ) and transcribing software is recommended for digital audio or video files, since this allows synchronous playback and typing (see Fig. 2 ).

Analogue audio recording equipment: dictaphone with microphone and mini-cassette tape and foot-pedal controlled transcription machine with headphones

Digital video recording equipment: video camera with firewire computer lead, mini DV cassette and Transana transcribing software

Representation of audible and visible data into written form is an interpretive process which involves making judgments and is therefore the first step in analysing data. Decisions about transcribing are guided by the methodological assumptions underpinning a particular research project, and there are therefore many different ways to transcribe the same data. Researchers need to decide which level of transcription detail is required for a particular project and how data are to be represented in written form.

Transcribing is an interpretive act rather than simply a technical procedure, and the close observation that transcribing entails can lead to noticing unanticipated phenomena. It is impossible to represent the full complexity of human interaction on a transcript and so listening to and/or watching the ‘original’ recorded data brings data alive through appreciating the way that things have been said as well as what has been said.

Funding: Primary Care Researcher Development award, Department of Health National Coordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development.

Ethical approval: East London and the City Ethical Committee.

Conflict of interest: None.

This paper derives from a PhD thesis written by Julia Bailey entitled ‘Doctor-patient consultations for upper respiratory tract infections: a discourse analysis’, which was supervised by Celia Roberts, Roger Jones and Jane Barlow. Thanks are due to doctors and patients who participated in the project, to practice staff, and to Anne Rouse for her advice on the practicalities of transcribing.

Transcription Conventions

(?) talk too obscure to transcribe.

Hhhhh audible out-breath

.hhh in-breath

[ overlapping talk begins

] overlapping talk ends

(.) silence, less than half a second

(..) silence, less than one second

(2.8) silence measured in 10 ths of a second

:::: lengthening of a sound

Becau- cut off, interruption of a sound

he says. Emphasis

= no silence at all between sounds

LOUD sounds

? rising intonation

(left hand on neck) body conduct

[notes, comments]

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Author notes

- consultation

- primary health care

- qualitative research

- interpretation of findings

Julia Bailey’s article on transcription of qualitative research data caught my attention because she gives the reader valuable advice regarding the theoretical and practical decisions involved in the process of transcription. For example, she emphasized the importance of focusing on the aim of the research project, on proper reduction of original data, on capturing the meaning of verbal and non-verbal interaction, and on the influence of the researcher’s interpretation of raw data on the outcome of the study (1).

Transcription is indeed a crucial process in any qualitative research project as it is the first step in the analysis of raw data. I agree with Bailey that investigators should be very careful with handling this process. I would like to add a few thoughts about the transcription process by reviewing some additional literature sources and by adding a few of my own experiences.

Marshall and Rossman (2) pointed out that we do not speak in paragraphs and do not give signals to researchers about punctuation during a conversation. Thus, transcribing qualitative data is challenging because the transcriber makes judgments and shapes the meaning of the written words. Sofaer (3) emphasized that the analysis and interpretation process should be deliberate and thorough in order to avoid the use of initial impressions. Bradley and Curry (4) discussed the importance of formatting and suggest the labeling of transcripts with a systematic file name and inserting line-numbering so that communication among members of the analysis team is easier, particularly when certain sections of an interview are being discussed later. They also suggest that once a transcript has been prepared, it should be read closely to gain a general understanding of the data. I found it personally quite helpful to read out loud my self-prepared transcripts for several times, which significantly improved my understanding of the qualitative data and also facilitated the subsequent development of coding categories.

Lichtman (5) discussed the issue of transcribing research data collected from a focus group interview with many people (e.g., 10 different voices). She pointed to the difficulty in transcribing those raw data because some people may speak at the same time, some may interrupt, and others may be talking so quietly that it is difficult to understand them. A solution to this problem is to listen and then extract themes rather than to attempt distinguishing one voice from another. I believe this is a good idea.

Transcribing recorded qualitative data is time-consuming and can be quite costly. Most literature sources I read indicate that self- transcribing original data has advantages over hiring a professional transcriber. However, this may not always be possible, particularly when large data sets need to be processed. Seidman (6) pointed out that an advantage of transcribing own tapes is that the investigator comes to know his/her interviews better. In case someone else is hired to transcribe the raw data, Bogdan and Biklen (7) suggest that the investigator should work closely together with the transcriber in order to make sure that the transcription is accurate. More specifically, when a professional transcriber is hired, the investigator should have prepared detailed written instructions for this person. As Seidman (6) puts it: “Writing out the instructions will improve the consistency of the process, encourage the researchers to think through all that is involved, and allow them to share their decision making with their readers at a later point.â€

Another important issue relates to the length of the transcripts. Should everything be transcribed or only certain sections of it? Seidman (6) does not recommend preselecting particular parts of the tape for transcription and omitting others because this could lead to premature judgments about what is important and what is not. I have tried out both ways and came to the same conclusion.

The term “transcription†is well known in biology. In this scientific discipline, it relates to “gene-transcription,†a process that can be defined as using the DNA as a template in order to make RNA strands (the transcripts) from it (8). If the genes encoded in the DNA are not accurately transcribed, the deciphering of the transcripts will be difficult and may result in improper protein synthesis. This, in turn, can significantly impact cellular functions. I suggest that we recognize the significance of “accurate gene transcription†in biology and adopt it to the field of qualitative research. Accurate “qualitative data transcription†will allow us to obtain a readable text that has important meaning and can help us solve complex social phenomena, including those related to medicine, public health, and education.

1. Bailey J. First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing. Fam Pract. 2008; 25: 127-131.

2. Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing Qualitative Research. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006.

3. Sofaer S. Qualitative research methods. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002; 14: 329-336.

4. Bradley EH, Curry LA. Codes to theory: a critical stage in qualitative analysis. In: Curry L, Shield R, Wetle T (eds.). Improving Aging and Public Health Research: Qualitative and Mixed Methods. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2006: 91-102.

5. Lichtman M. Qualitative Research in Education: A User’s Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006.

6. Seidman I. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. 3rd edn. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 2006.

7. Bogdan RC, Biklen SK. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theories and Methods. 5th edn. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, 2007.

8. Starr C. Basic Concepts in Biology. 6th edn. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brook/Cole, 2006.

Conflict of Interest:

None declared

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2229

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

How to Transcribe Interviews for Qualitative Research

Saving time and effort with Notta, starting from today!

Collecting numerical data is as easy as clicking copy and paste. But what about the unique feedback, comments, and descriptions of qualitative data? Not so much. Once you’ve figured out your research objectives and conducted your interviews, everything else feels intimidating. How do you transcribe entire interviews if every participant talks about something different? How do you even measure answers in natural language with unique viewpoints?

I feel you. When I managed customer support for an online company a few years ago, a lot of our valuable feedback didn’t come from scores out of 10 on product surveys, but rather from customer emails, reviews, and social media comments telling us what they loved and where we could do better. I think that’s why transcribing interviews for qualitative research like this is so important. It’s the first step in organizing all kinds of information into groups and themes you can actually use.

Keep reading because I’ll explain more about how to transcribe an interview (and why you should), plus using transcription software for qualitative research to speed things up.

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is when you ask open questions that prompt people for descriptive answers. It encourages feedback and observations that you can’t measure with numbers. If quantitative research finds out the facts from numbers , qualitative research is the reason why people make specific choices or behave a certain way .

What is an Interview?

An interview is a great qualitative feedback method whereby you ask a series of open-ended questions to an interviewee to gain answers, feedback, and opinions in their own words. You can conduct interviews in person, over the phone, or on video, solo or in groups.

How to Prepare an Interview for Qualitative Research

1. Decide Important Information for Your Interview

Start with your research objectives and create questions based on these - what do you want to learn?

How will you structure your interview? For structured interviews, prepare a list of questions to ask. For unstructured interviews, list topics you want to talk about.

Use open-ended questions to help the interviewee express their thoughts in their own words.

Ask your team to review and approve the interview questions before you begin so you can tweak them if needed.

2. What You Need from Your Research Interview Transcription

How will you extract answers and comments from your transcripts? Coding answers for specific questions and connecting themes can help categorize the data.

Will you read through the entire transcript or condense the conversation into bullet points? You can format your transcript in three ways:

Full Verbatim : The conversation in a raw, unedited state including slang and false starts

Intelligent Verbatim : A cleaned-up version of the full transcript, written in a grammatically correct way without false starts or stuttering

Detailed notes : Summarizing the conversation into scannable notes that cover the main points of conversation

3. Have Your Tools Ready

Choose a good quality microphone and noise-canceling headset that provides clear audio for easy communication.

What device will you use to conduct the interview and write the transcript? Have your PC, Mac, or tablet up to date with software installed.

Settle on the transcription software you’ll use. If you’re typing the transcript manually, have your preferred text editor installed. For automatic transcription, set up your Notta account and log in.

How to Transcribe an Interview for Qualitative Research

Manually transcribe your interview.

Listen to the recorded interview all the way through to familiarize yourself with the content of the conversation.

Open your favorite text editor such as Microsoft Word or Notepad and begin writing the speech while you listen to the recording. Don’t worry about getting it perfect the first time, just write as much as possible.

Go through the transcript again while listening to the audio, this time adding in timestamps in [HH:MM:SS] format and speaker tags every time the interviewer and interviewee speak, with a tag such as [Rachel] or [Interviewer]. If the interviewee wishes to remain anonymous, you can use a general tag such as [Interviewee].

Save your document to your device and share with your research team. Repeat these steps for every interview.

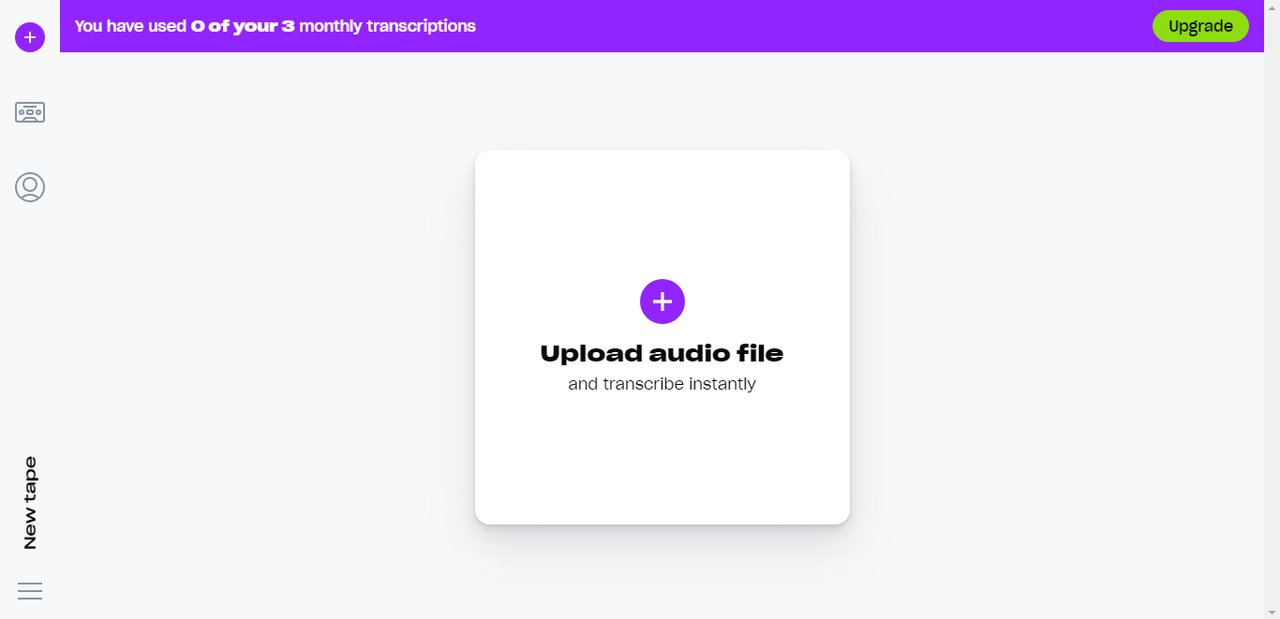

Automatically Transcribe Qualitative Interviews with Notta

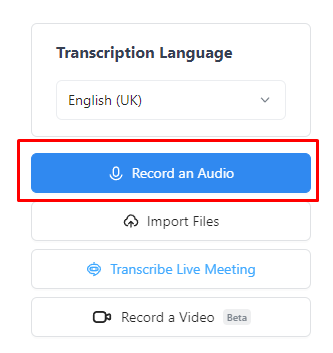

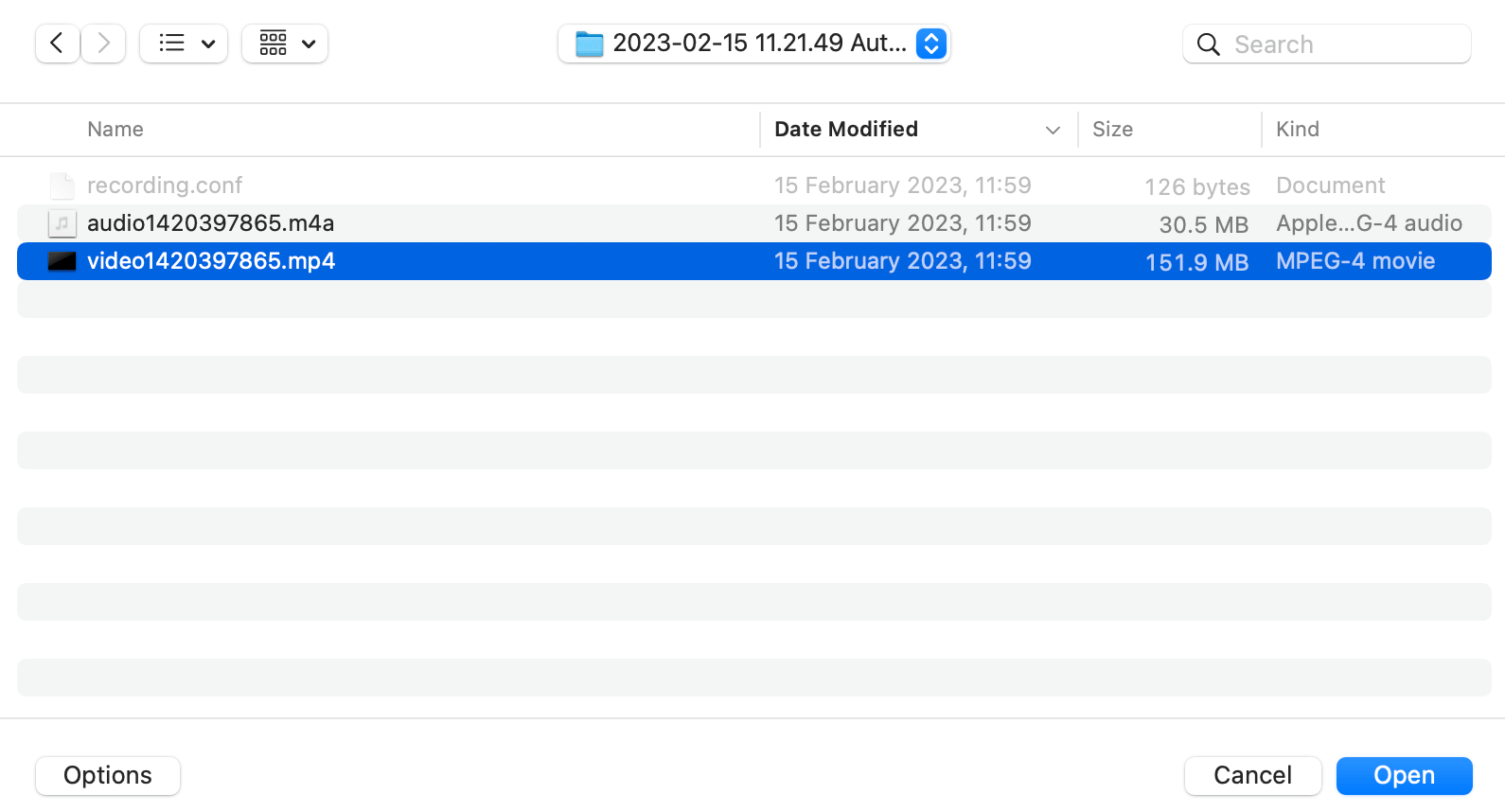

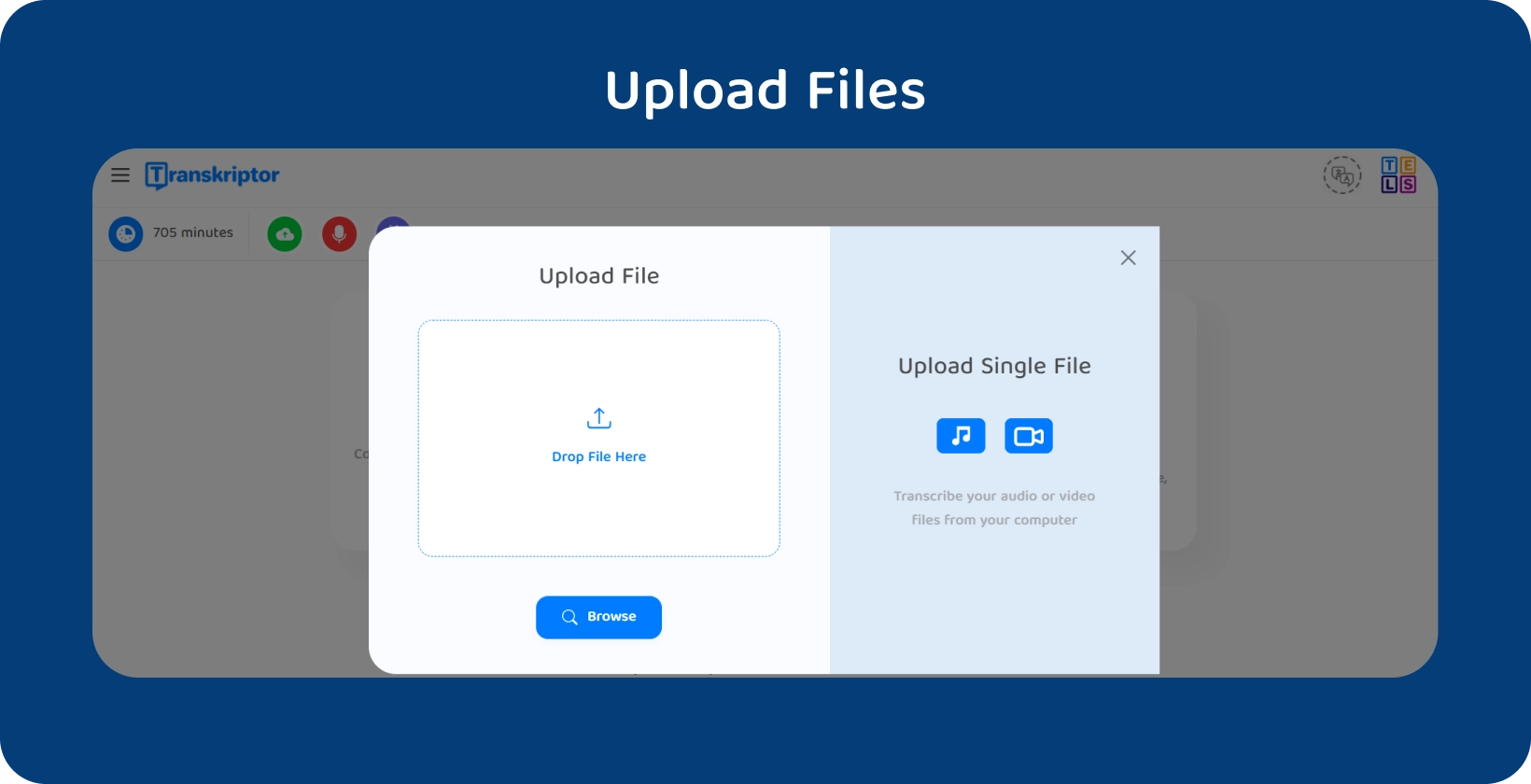

Upload an existing recording to notta.

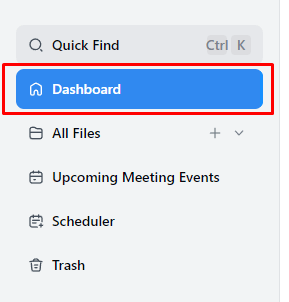

Log into Notta and go to your Dashboard .

Click ‘ Import files ’. You can drag and drop your audio or video file or paste a Google Drive, Dropbox, or YouTube link in the ‘ Import from link ’ field.

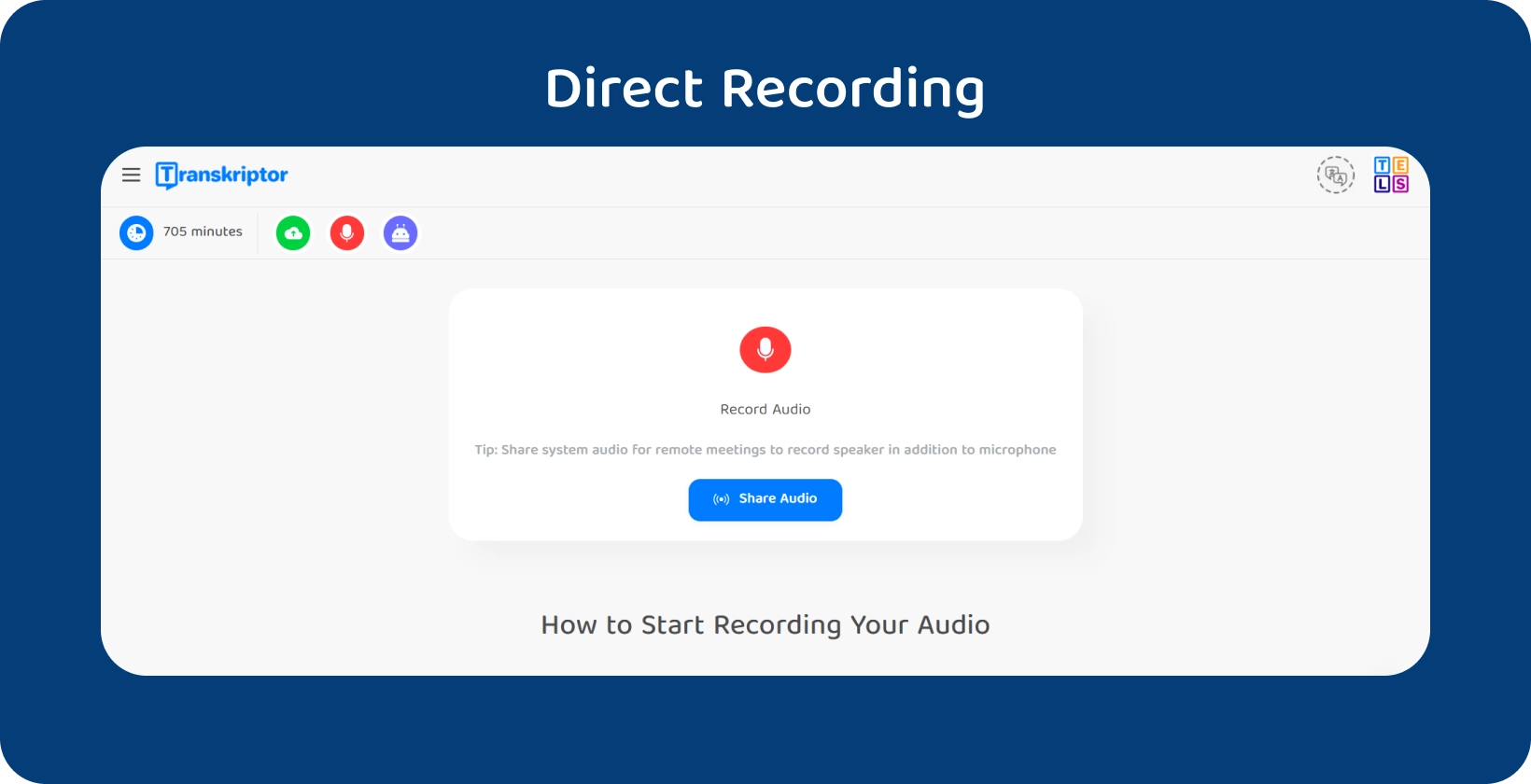

Record a Live Meeting or Live Audio with Notta

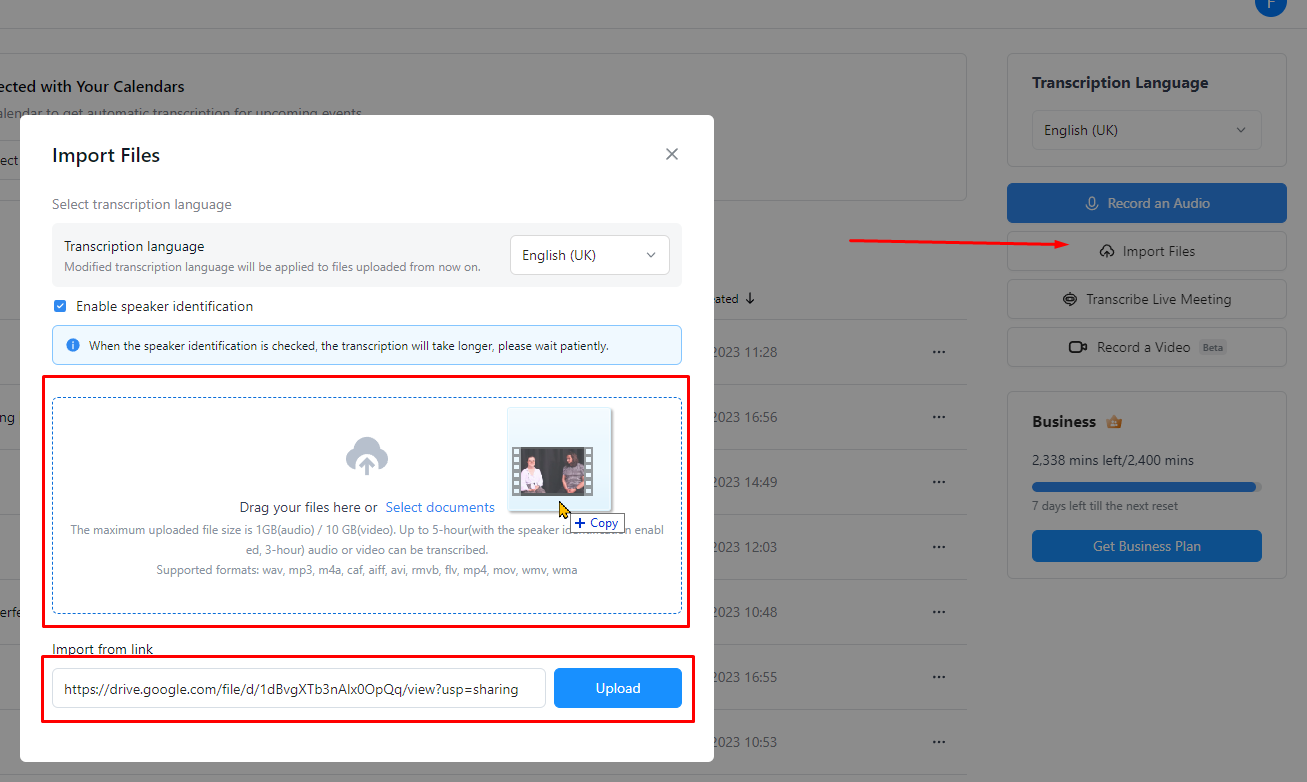

Click ‘ Transcribe live meeting ’ and paste your meeting link from Zoom, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, or Webex, if you’re conducting your meeting virtually. This invites Notta Bot to record and transcribe your conversation.

Click ‘ Record an Audio ’ if your interview is in person. This starts recording using your microphone and transcribes in real time.

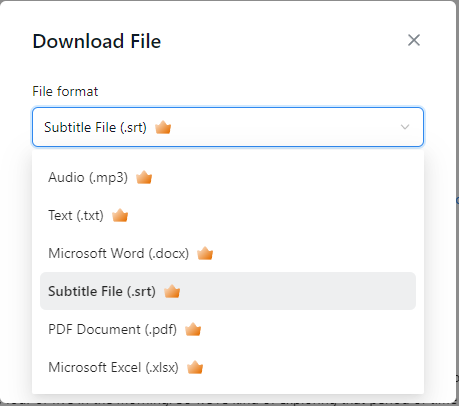

Edit, Export, and Share Your Transcript

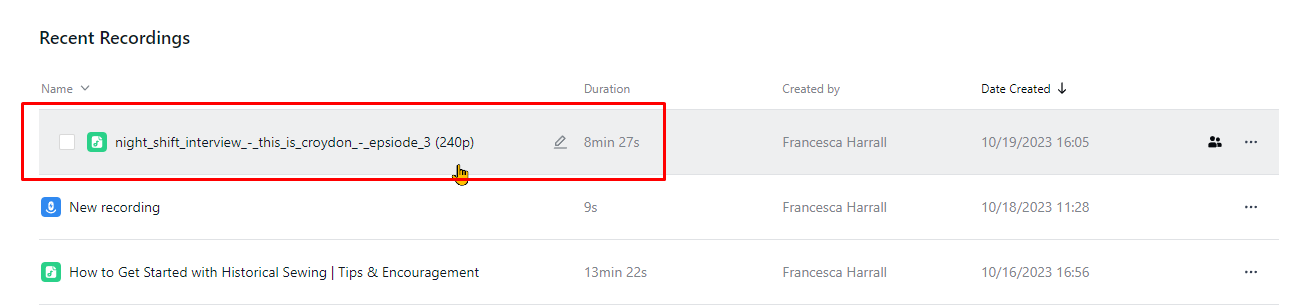

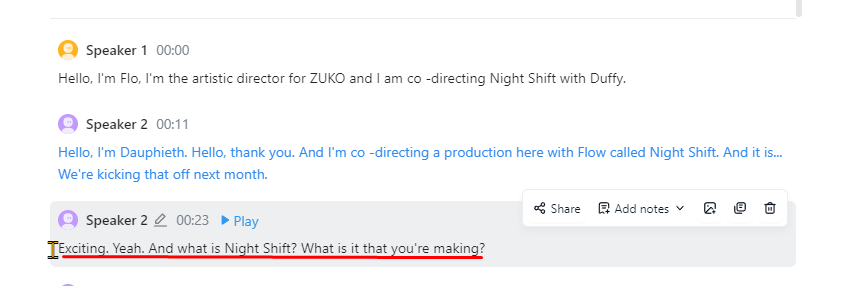

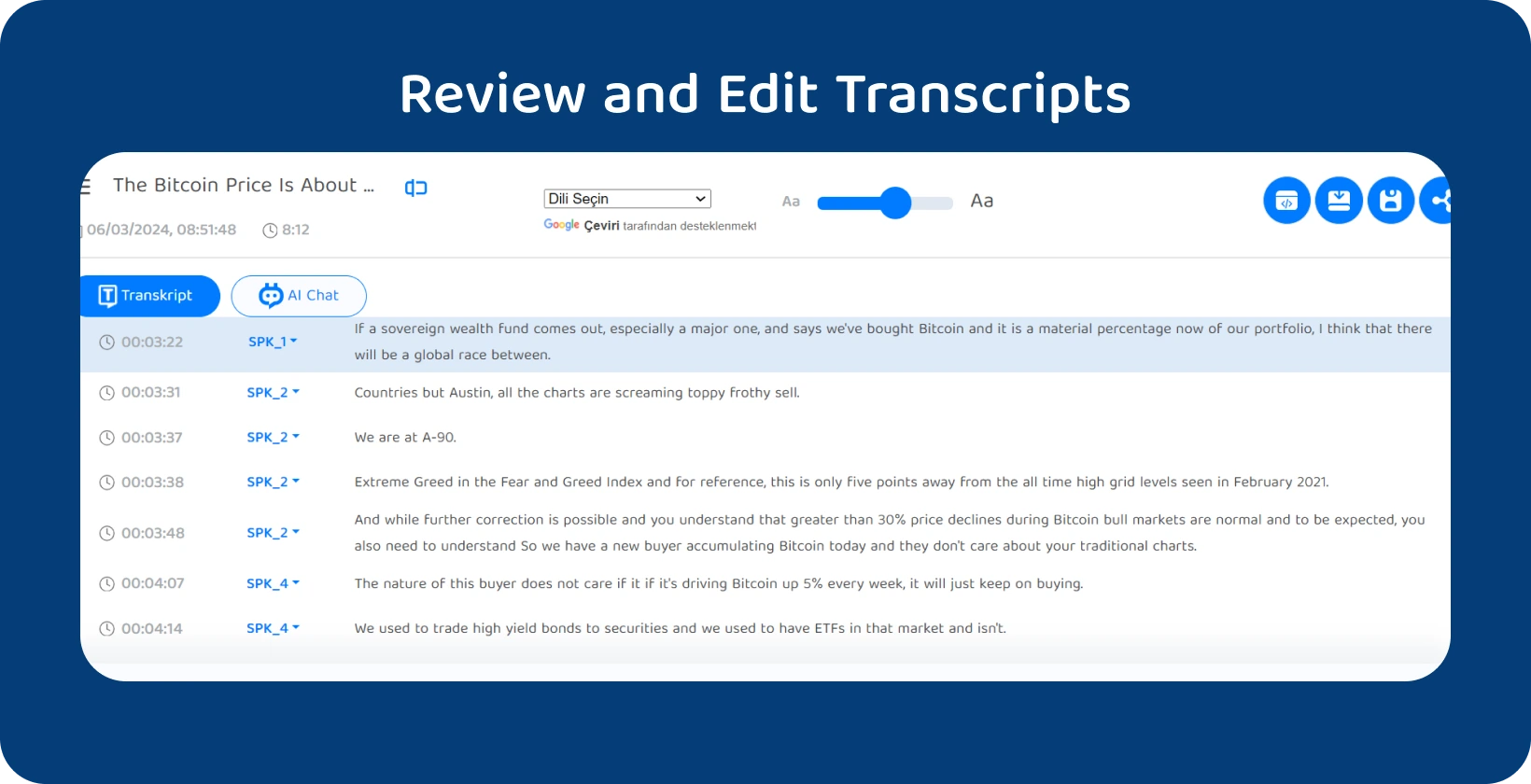

Click on the interview transcript under ‘ Recent Recordings ’ on your Notta dashboard.

Read through the full transcript. You can adjust the blocks of text by clicking your cursor and pressing ‘ Enter ’ or ‘ Delete ’ to join or separate transcript text.

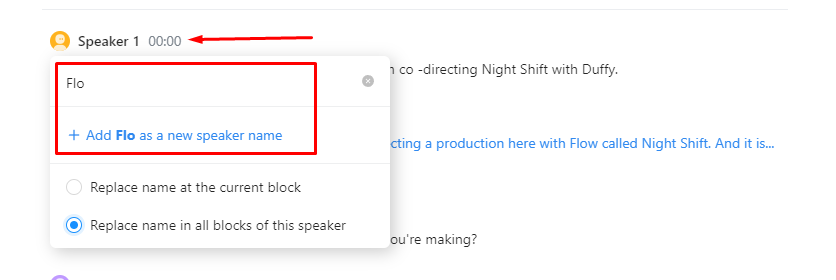

Click a speaker’s name to change it. You can type their name and then decide whether you want to adjust it for this block of text only, or for the entire transcript. Remember, if an interviewee wants to remain anonymous, you can type a generic tag like ‘Interviewee’.

Correct transcription errors by typing directly into the transcript text. Click the highlighted words or phrases in blue and the audio playback will jump to this point.

Add written notes and images to specific points in your transcript using the floating toolbar. This is helpful if you want to add observations you made during the interview.

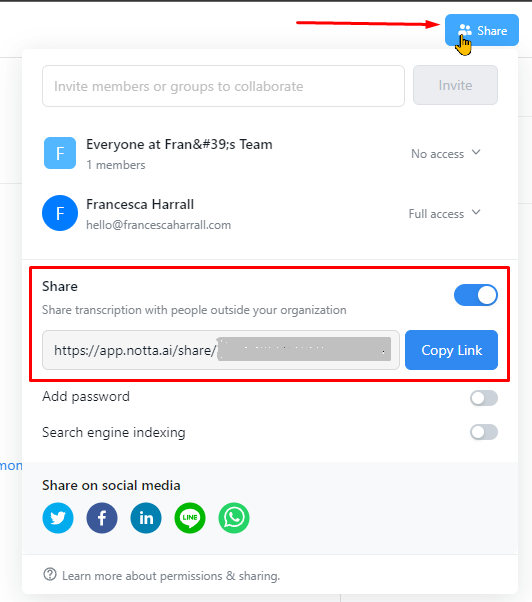

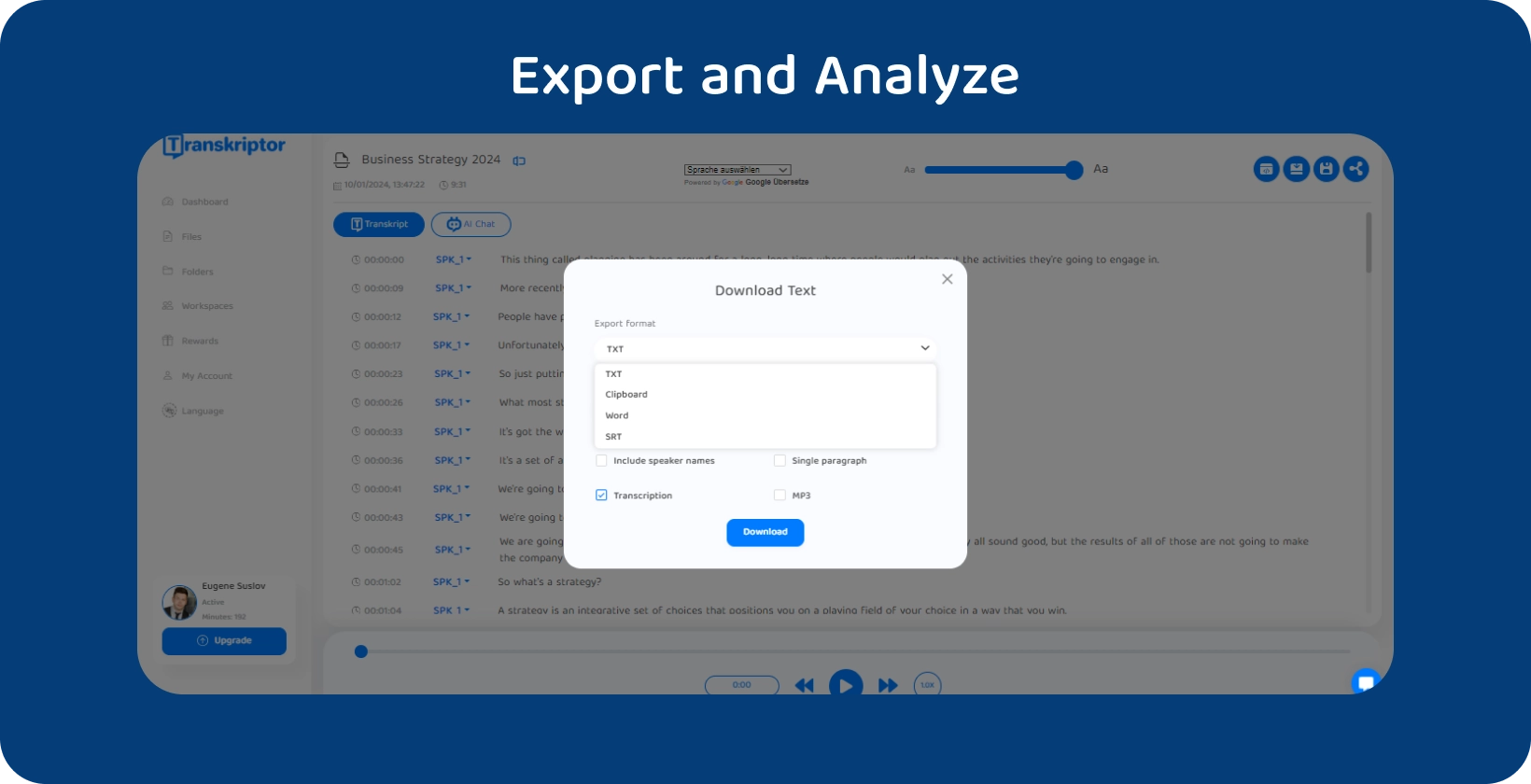

Click the ‘ Download ’ icon at the top of your transcript page and export in a variety of formats. Notta exports in MP3, TXT, SRT, PDF, DOCX, and XLSX. You can toggle timestamps, speakers, and more.

Share the transcript with people in your team by clicking the ‘ Share ’ button, then managing group and team permissions with the drop-down menus. Create a shareable link by toggling ‘ Share ’ on and copy the link provided.

How to Analyze the Interview Qualitative Data

At first glance, you might feel daunted by the prospect of arranging your qualitative data. After all, numerical and factual data is easy to organize. But what about unique answers, observations, and feedback? Don’t worry—here are some simple steps you can follow to analyze your findings without pulling your hair out.

Organize the Information You Collected at Interview

To study your interviews effectively, use the same method of collection for every interview. This means transcribing each interview in the same way and asking the same or similar questions to each participant. This way, you can stick to the same process when analyzing what data you’ve collected.

Summarize Insights Using Your Transcript

Reading through full transcripts takes a lot of time, so you may find it easier to condense the information into a summary. Use Notta AI to create a summary in a few moments.

Click the ‘ Magic wand ’ icon in your Notta transcript and then click ‘ Generate ’. Notta AI uses machine learning to create an AI summary with three useful parts:

AI Summary: A condensed version of your full transcript, highlighting the basic points

Chapters: A list of key moments and themes during the conversation

Action items: A list of next steps to take, according to the conversation

Explore the Data

Creating a coding system helps you categorize the data and make it easier to understand. Codes can vary and come in a variety of formats but here are some examples:

Descriptive codes : Providing context for the data such as ‘interview setting in coffee shop’.

In-Vivo codes : A verbatim phrase the interviewee used to describe a product or service such as ‘I couldn’t live without it’.

Themed codes : Describing an overarching theme or pattern relating to the interview questions such as ‘accessibility issues’.

Process codes : Identifies what stage of the process the interviewee is currently at in relation to your product or service, such as ‘canceled subscription’ or ‘I’ve heard of your product recently’.

It’s vital that everyone involved in research sticks to these pre-agreed codes to organize data efficiently. It’s okay if you need to revise your methods as you go, but keep everyone informed so there’s no confusion.

Present Your Research

To make your research findings easier to interpret, you can organize them in several ways. Here are some common methods to share your data:

Spreadsheets : arrange your data into a table

Graphs : Displays themes and patterns using their codes in visual graphs

Word clouds : Using In-Vivo codes, displays the most commonly used language by participants

Are There Any Other Qualitative Research Methods?

Interviews aren’t the only way to collect useful qualitative data. If you’re pressed for time or need a deeper understanding of a culture or group, you can try other options.

Observations : Observing peoples’ behaviors in their natural setting without directly interacting with them. Take detailed field notes to describe what you can see, hear, and encounter in terms of interactions.

Focus groups : Taking a small group of people and asking questions. Their answers and interactions with each other can provide verbal and non-verbal insights.

Ethnography : Immersing yourself in a culture or group of people to understand their behaviors, rituals, and perceptions. This is similar to observations but might require deeper and longer-term fieldwork.

Narrative analysis : Studying personal stories, biographies, and autobiographical data to understand the perceptions and meanings people give to certain experiences.

Surveys : Create a series of open-ended questions in a questionnaire to distribute to people, to get unique feedback in their own words.

Secondary research : Gathering different, pre-existing sources of feedback as qualitative data. This includes emails, texts, images, videos, audio recordings, documents, policies, and diaries.

Frequently Asked Questions about Transcription in Qualitative Research

What is a good example of qualitative data.

Qualitative data is valuable when it provides insights into a person’s reasoning behind certain behaviors and lived experiences. Some examples of good qualitative data could include:

Documents like contracts, notes, and emails that contain descriptive, non-numerical data

Social media post and forum comments expressing authentic discussions and opinions

Audio or video recordings of natural conversations

The best qualitative data provides real, descriptive feedback in a person’s natural language. It should express feelings, emotions, attitudes, and perceptions.

Is Qualitative Research Subjective?

Yes, qualitative research is subjective because it’s relative to that individual’s culture, experience, and perceptions. It’s based on opinions and thoughts. Quantitative data is objective because it deals with numerical facts. Both have a place in research, but the subjective nature of qualitative research provides reasoning behind behaviors and decisions.

Why Should You Choose Qualitative Research?

There are many reasons why qualitative research is valuable:

It’s unbiased, as participants can provide thoughts and opinions in their own words.

You can uncover new theories and hypotheses that you may not have known about previously. Collecting qualitative data is often unstructured, allowing people to express new ideas and themes

Gain a deeper understanding of trends. Participants using their own language allows you to find common patterns and insights on a particular issue.

You can discuss sensitive topics. Participants can broach subjects in their own words and share as much as they feel comfortable with.

What is the Difference Between Qualitative and Quantitative Data?

Quantitative data is fixed, numerical feedback. Examples can include annual income, number of people in a household, times a person has bought a specific item, and so on. Qualitative data provides non-numerical, descriptive feedback in natural language. Examples might look like thoughts about a brand’s new color scheme or favorite part of visiting a recent conference.

How Do I Record an Interview?

Here are some basic steps you can follow to prepare for recording an interview as part of your qualitative research:

Write out a list of open-ended questions or a list of topics you want to cover.

Check that the device you’re recording on is charged.

Plug in your microphone and headphones and test them.

Conduct your interview in a quiet environment.

Use the meeting software’s built-in recorder such as Zoom, or a meeting recorder such as Notta.

When the interview starts, set your interviewee at ease by asking some icebreaker questions about their day, their plans, and themselves to get to know each other better and build rapport.

Move onto your interview questions, leaving plenty of time for the interviewee to gather their thoughts and answer in their own words.

Listen and follow up to ask for clarification if needed.

Thank them for their time and let them know what the next steps are.

Check the recorded audio or video file to ensure it came out clearly, ready for transcription.

See? Transcribing an interview for qualitative research doesn’t have to be stressful or time-consuming when you have a plan! My biggest piece of advice here is to understand the goal of the interviews you’re conducting . Interviews with vague questions and no direction in relation to your research objective aren’t likely to garner you valuable information you can actually use. Once you know what insights you’re aiming to uncover, it makes the conversation feel more productive and your research interview transcription will be far easier to use when collecting the data.

Chrome Extension

Help Center

vs Otter.ai

vs Fireflies.ai

vs Happy Scribe

vs Sonix.ai

Integrations

Microsoft Teams

Google Meet

Google Drive

Audio to Text Converter

Video to Text Converter

Online Video Converter

Online Audio Converter

Online Vocal Remover

YouTube Video Summarizer

Transcribing interviews for qualitative research

Transcribing interviews is an important step in qualitative research, as it forms the backbone of data analysis and interpretation. In other words we can say that it acts as a vital link between those unfiltered conversations and insightful data acquired from them. But why is accurate transcription so crucial in qualitative studies?

The fundamentals of qualitative research itself provide the first justification. The depth with which linguistic expressions and emotions are communicated during interviews is crucial for this kind of research. Accurate transcription ensures that these non-verbal cues are also added for more clarity.

Transcribing interviews qualitative research is essential to ensuring the correctness of findings because it enables researchers to fully capture the range of participant replies and perspectives. Moving forward in this article we have compiled a comprehensive guide to help you get a more clear perspective on how to transcribe interviews for qualitative research.

What Is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is one of the most commonly used research methods in the field of academia. Instead of concentrating just on the what, where, and when of decision-making, it explores the why and how by focusing on the human aspects of a specific issue or situation. It aims to comprehend people's experiences, actions, feelings, and the interpretations they place on objects.

Getting a much deeper insight into people's attitudes, actions, value systems, concerns, motives and goals is the main aim of qualitative research. It is employed to acquire a deeper comprehension of intricate occurrences that are challenging to put into numerical form.

The main characteristics of qualitative research are:

- Focus on context: It explores the context in which behaviours and events take place.

- Subjectivity: It recognises the subjective nature of the study and frequently captures the perspectives of the participants.

- Extensive analysis: This entails a thorough examination of a limited number of case studies or circumstances.

- Inductive approach: The inductive approach often begins with observations and builds theories from them.

- Flexibility in design: As the study goes on, the research question format may change. Here it is not necessary to follow the predetermined context.

Researchers use qualitative interview as their main method of data collection for this research since it allows them to interact with the subject first hand and focus on the non-verbal cues along with the information they are sharing.

Looking for support in transcribing your qualitative research interviews? Good Tape offers transcription services that can help you better understand your interviews. We're here to help make your transcription process more manageable and efficient. Explore how Good Tape can assist you in your research endeavors .

Qualitative vs quantitative interviews

Qualitative and quantitative interviews are different research approaches, each with a unique strategy for collecting and interpreting data. Quantitative interviews seek to measure human behaviour and experiences in a form that can be statistically examined, whereas qualitative interviews concentrate on investigating and comprehending the depth and complexity of human behaviour and experiences.

While both are extensively used in the field of research, it is important to understand where either of the two should be used. Below is a comparative table of both against which you can determine which of the two would work best in your scenario.

This table presents a clear contrast between qualitative and quantitative interviews, highlighting the differences in their technique, strategy, and study conclusions. The choice between both majorly depends on the research question at hand and the nature of the topic being studied.

How to transcribe an interview for qualitative research

For qualitative research, transcription of interviews is a painstaking procedure that needs time and close attention to detail. It requires turning spoken words from your recorded audio or video into text.

In qualitative research, this transcribing procedure is essential to data processing. Here's a step-by-step tutorial on effectively transcribing interviews, along with a few tips to make the process as easy as it can be.

Record clear audio of the interview

Select a peaceful, quiet workstation for your interviews to reduce distractions and improve focus. It is important to have a well-positioned microphone and high-quality headphones if you want to record even the minute details of speech without picking up excessive background noise.

If there are any unpleasant noises in your audio, services like Good Tape can be quite helpful. They are made to carefully pick up on all spoken and nonverbal cues, even in busy settings, and automatically transcribe all your work for you, so you won't miss any important information.

Work around your transcription

Precise transcription is essential for detailed analysis, accurately recording each word and nonverbal cue. This comprehensive approach allows for a deeper understanding of both the verbal as well as non-verbal cues in communication.

Similarly, intelligent verbatim concentrates on streamlining the text by eliminating unnecessary words and sounds to focus on the primary concepts, resulting in a transcript that is more focused and structured. Revised transcriptions enhance the material by improving clarity and fixing grammar, guaranteeing that the final transcript is accurate, comprehensible, and cohesive.

Audio transcription services such as Good Tape make accurate transcription easy with a shorter turnaround time.

Finalise the transcript

For easy navigation and the identification of important points or sensitive parts within the text, transcript formatting consistency is essential. Consistent formatting facilitates reading and improves the transcript's overall usefulness.

A further crucial stage is anonymisation, which anonymises any confidential or private data to comply with legal regulations. This also gives the interviewees peace of mind knowing that the information they provide will not be used illegally. To ensure that the transcript is correct, well-written, and presented professionally, one last review is necessary to spot any spelling, grammatical, or flow errors.

Some useful tips

Manual transcription can take a lot of time, therefore patience is essential. However, if you wish to have accurate transcripts in less time, using services such as Good Tape can cut down on the amount of time required.

It's also very important to make sure that your transcribed documents are safe. Maintaining regular backups is essential to avoiding data loss. Using services that automatically store and back up your transcribed audio might be a sensible choice if you find it difficult to remember to do backups, since they provide efficiency and peace of mind.

Why accurate transcription matters in qualitative research

Precise transcription is essential to qualitative research because it supports the accuracy and essence of the whole research process. It is the first stage of data analysis and has a direct impact on the findings and recommendations of the study. There are several reasons why accurate transcribing is important and advantageous.

Impact on data analysis

- Maintains originality: Preserving the original context of spoken words is ensured via precise transcription. For accurate interpretation of the data, this is essential.

- Enables comprehensive study: If the transcription has even minute error, it may prevent researchers from doing a thorough study of the interview data, including discourse, theme, and content analysis. Conversation analysis requires a lot of details which is possible through detailed notes of its accurate transcription.

- Supports accuracy: Data analysis in qualitative research is a very crucial step. More valid findings are produced when transcripts are accurate because they give researchers a solid foundation.

Impact on research outcomes

- Validity of findings: The reliability of the study findings is directly impacted by the quality of the transcribing. Inaccurate conclusions may result from word misinterpretation or omission.

- Reliability and reproducibility: A key component of scientific investigation is replication, which is made possible by accurate transcribing, which also increases the research's dependability.

- Reflects the voice of the participant: Accurate transcribing preserves the integrity of the participants' contributions by correctly capturing their voices.

Benefits of accurate transcription

- Enhances credibility: Precisely recorded information strengthens the credibility of the study among other researchers and readers

- Facilitates peer review and cooperation: Because other researchers can comprehend and analyse the data with clarity, it makes effective peer review and cooperation possible.

- Enhances engagement with data: When data is precisely translated, researchers may interact with it at a deeper level, which results in more perceptive analysis and interpretation.

Accurate transcription plays a crucial role in maintaining the validity, reliability, and integrity of the research findings. It improves the quality and depth of data analysis, guaranteeing that the conclusions are solid, reliable, and accurate representations of the experiences and viewpoints of the participants.

Discover Good Tape’s interview transcription service

We’ve understood in depth how to transcribe interviews for qualitative research, let’s go over how you can do so accurately and quickly without having to put in much effort. Good Tape has a relatively simpler user interface which you can navigate through without any manual or instructions. Here’s what you can expect when going through the process of transcribing your audios.

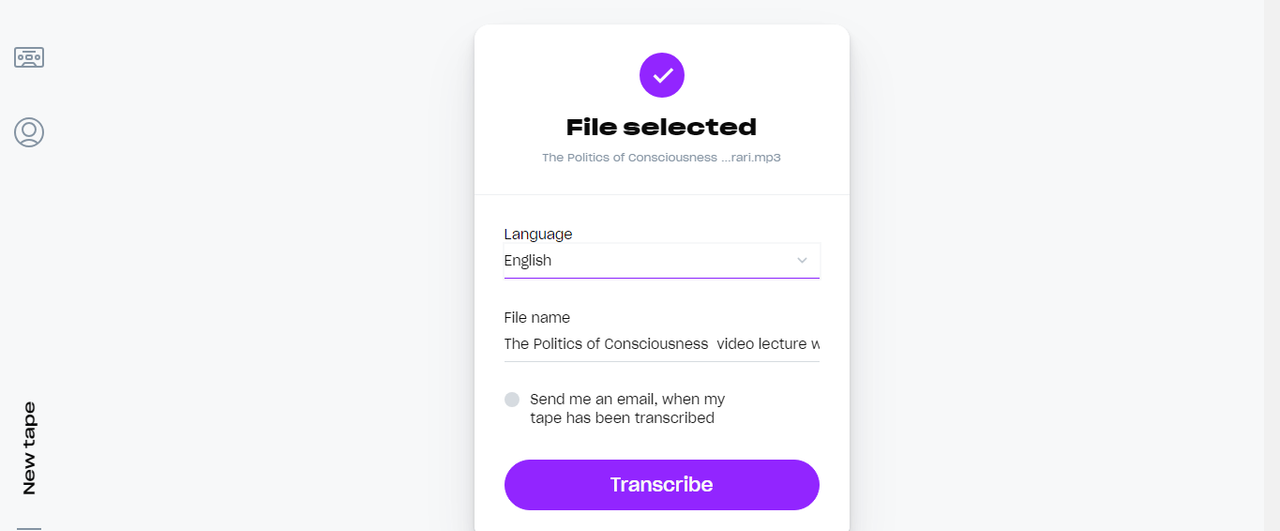

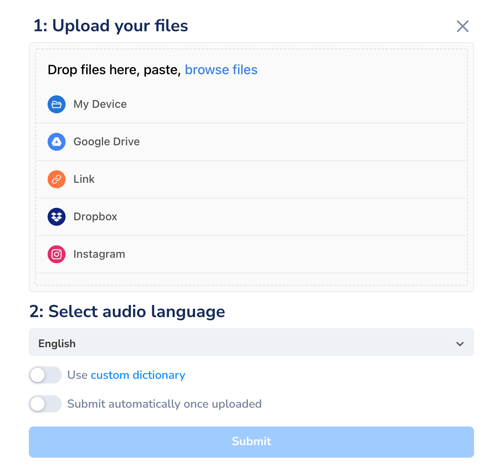

- Upload your file: The first step in the process is to upload the file you need to transcribe. Make sure the file is complete and has all the information you require

- Select the language: Good Tape has a number of options when it comes to choosing the language of transcription. Select the one you want, although you can also choose the “auto-detect” option for the system to automatically identify the language in the audio.

- Transcribe the text: Once the file is uploaded and the language is chosen, proceed further by clicking the “transcribe” button. Your audio transcription process starts here.

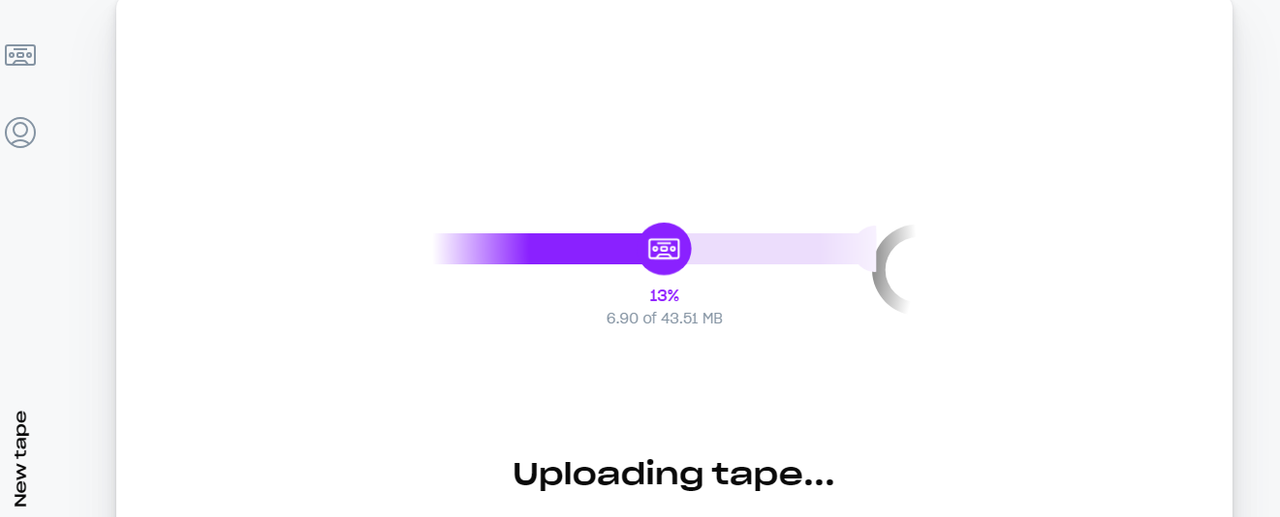

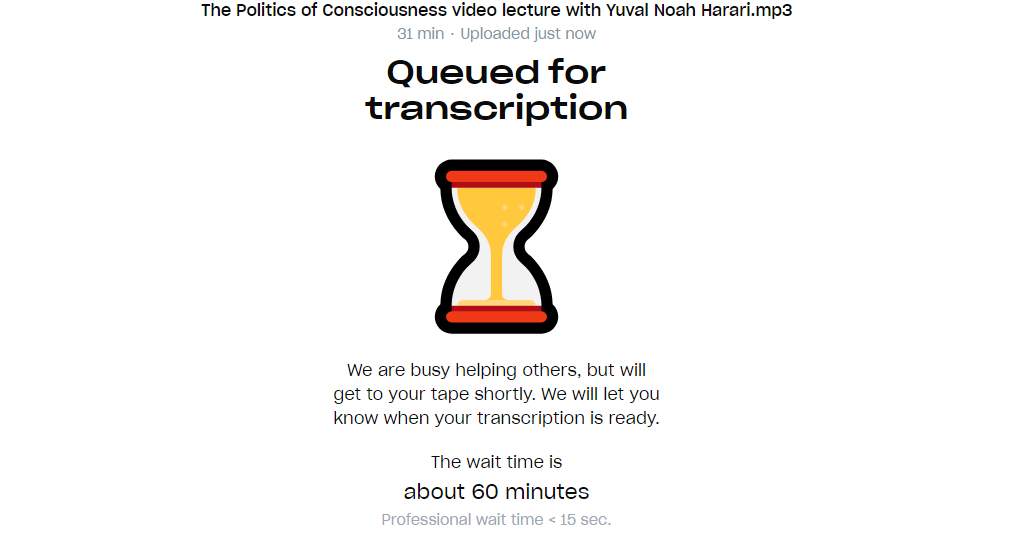

- To wait or not to wait: If you’re a casual plan user, you will have to wait for some time for your transcription to be completed due to excessive load by the users. However, if you’re a professional or a team user, you get your results ASAP! The wait time depends on the plan you’re subscribed to .

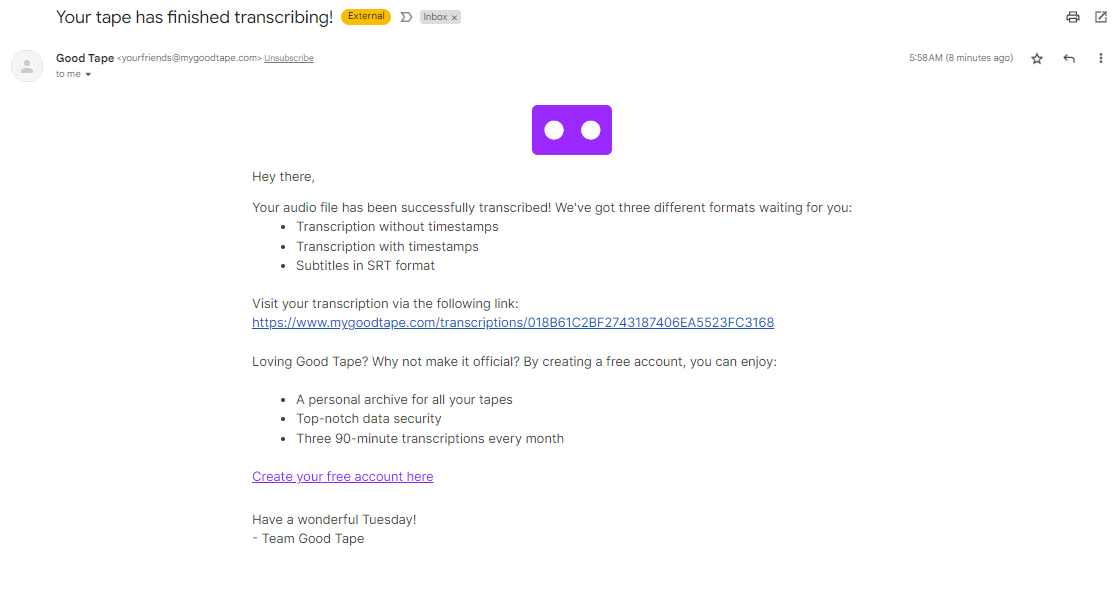

- Get notified: You will receive a notification once your transcribed document is ready. An e-mail will be sent to your inbox containing the link to access and download the document.

Looking for a good transcribing interviews qualitative research service? Try out Good Tape’s audio-to-text transcription service today and increase your work productivity. Their AI incorporated technology makes sure that every verbal and non-verbal cue is recorded, giving your qualitative data a deeper level of understanding.

More articles

What is verbatim transcription?

The essential transcription services for qualitative research

Board meeting transcription

The power of meeting recording and note-taking

We believe everyone should have access to top-quality automatic trancriptions.

That's why Good Tape is completely free to use . No credit card required.

Why is it free?

Transcribing Interviews for Qualitative Research: Best Practices

- Serra Ardem

The long hours dedicated to transcribing interviews are now in a galaxy far far away, thanks to the developments in AI and machine learning. Qualitative research highly benefits from these advancements as AI transcription technology not only saves valuable time but also increases research efficiency and accuracy.

In this blog, we emphasize the significance of transcribing interviews for qualitative research as well as the best practices in this area. We also explain why automatic transcription offers more advantages to researchers and how to choose an interview transcription software to achieve optimal results.

Let’s begin.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a systematic approach to understanding and explaining social phenomena. Focused on “How?” and “Why?” questions, it is an umbrella concept that involves different research methodologies including interviews, participant observation, focus groups and so on.

Qualitative data is based on words, behaviors and images. By analyzing these, qualitative research generates theories and hypotheses on how the social world is experienced and understood by people in everyday life. Unlike quantitative research that depends on numbers and statistics, qualitative research seeks to uncover the underlying meanings in human experiences.

Importance of Transcribing Interviews in Qualitative Research

Transcribing interviews for qualitative research offers several benefits that contribute to the overall depth and success of the research process. Here are its key advantages:

- Comprehensive analysis: Transcripts capture every word, nuance and non-verbal cue, which is a goldmine for data analysis. This allows researchers to identify themes and patterns thoroughly to draw meaningful conclusions.

- Enhanced reliability: Having the transcript for an interview will strengthen research validity by providing evidence to your argument. Plus, other researchers can review the transcription, ensuring transparency and collaboration.

- Reduced bias: Transcribing interviews will reduce bias as it minimizes the risk of misinterpreting or omitting information. Compared to note-taking, which may be influenced by the researcher’s perceptions, transcription offers a more objective representation of data.

- Increased accessibility: Via transcription , researchers can share and discuss findings with people who couldn’t participate in the interview due to language barriers. Furthermore, the practice improves accessibility for deaf and hard of hearing individuals by allowing them to engage with the findings through written text.

- Time-efficiency: No more jumping back and forth in audio files! When you transcribe the interview, you can quickly search for and navigate to specific parts, saving time during the analysis phase.

4 Types of Transcription

Transcription can be grouped into four categories: verbatim, intelligent verbatim, edited and phonetic. Let’s take a look at each one’s pros and cons, and highlight the best choice for transcribing interviews for qualitative research.

Verbatim Transcription

Verbatim transcription includes every sound in the audio recording such as coughs, doorbells and hesitations (er, mm, etc.) between sentences.

Pros: Provides the most complete and accurate record of the interview, which is essential for capturing the full context and subtle nuances.

Cons: May include unnecessary details. Can be time consuming and expensive to produce in case of manual transcription.

Primarily used in: legal proceedings, sociolinguistic research studies

Intelligent Verbatim Transcription

An intelligent verbatim transcript removes filler words and repetitions but retains key content and non-verbal cues. Its purpose is to provide a more on-point transcript.

Pros: Offers a balance between readability and details.

Cons: May sacrifice some context and require careful quality control to guarantee accuracy.

Primarily used in: qualitative research, especially in interviews and focus groups

Edited Transcription

Clarity is the main focus of an edited transcript. It corrects grammatical errors and eliminates filler words, repetitions and extraneous sounds.

Pros: More readable and concise, therefore suitable for general understanding and thematic analysis.

Cons: Risks losing some nuances and the authenticity of participants’ expressions.

Primarily used in: journalism and media contexts

Phonetic Transcription

Phonetic transcription is unorthodox as it uses symbols from the International Phonetic Association to represent sounds exactly as they are spoken. This includes accents, dialects and non-standard pronunciations.

Pros: Analyzing variations in pronunciation.

Cons: More complex and expensive than other types of transcription.

Primarily used in: linguistic studies

What is the best type for interview transcripts in qualitative research? As we’ve said above, intelligent verbatim transcription is often the best choice: It is readable and manageable for analysis, yet it also provides a detailed record of the conversation.

Still, always consider your research goals, questions, data and budget when transcribing interviews. An edited transcript might be sufficient if you want to focus on broader themes. Meanwhile, verbatim transcription can be pretty useful if details matter to you a lot.

Methods of Transcribing Interviews

There are two main methods when it comes to transcribing interviews: manual and automatic. While manual transcription involves a human transcriber typing out the spoken words in the interview, automatic transcription utilizes speech recognition technology to convert audio to text.

As in types of transcription, these two methods have their unique advantages and disadvantages. Human transcribers can better understand nuances and context. However, this method can also be pretty time consuming and it may be expensive to hire a professional transcriber.

On the other hand, automatic transcription is much faster and cost-effective. This is an important advantage in the realm of qualitative research where large amounts of interview data need to be processed and analyzed. You can definitely save time and resources by using software when transcribing interviews for research.

Moreover, automatic transcription services are getting more accurate day by day thanks to the developments in AI, machine learning and voice recognition. Current systems can handle diverse accents, linguistic variations and even contextual nuances very well. This significantly increases the reliability of the interview transcript and research results.

How to Choose an Interview Transcription Software

Decided to use an interview transcription software for research but confused on how to choose one? Look for these qualities when making your decision:

Accuracy is crucial when transcribing interviews as it directly influences the reliability of your data. Prioritize an AI-powered tool with a high accuracy rate to remain true to your original interview. We recommend you test the AI transcription software beforehand with a small sample of your interview.

Quick turnaround time is essential for researchers who work with large sums of interview data and tight deadlines. The right software must transcribe audio to text rapidly without compromising accuracy and meet the demands of an intense qualitative research process.

It is your responsibility to comply with ethical standards and protect your participants’ sensitive information. You must choose a tool that has end-to-end encryption and clear privacy policies.

Flexibility

Does the transcription software allow you to upload audio and video files in different formats? Is it easy to edit the transcript and add notes? This flexibility will help you refine interviews seamlessly, enhancing the quality of your data.

Customization

Speaker identification, timestamps and punctuation are indispensable when transcribing interviews for qualitative research. Select a software that allows you to tailor these elements to your needs.

Language Support

Make sure that the tool supports the languages spoken in your interviews. Break down the language barrier by choosing a software that transcribes multiple languages and enrich your research with global perspectives.

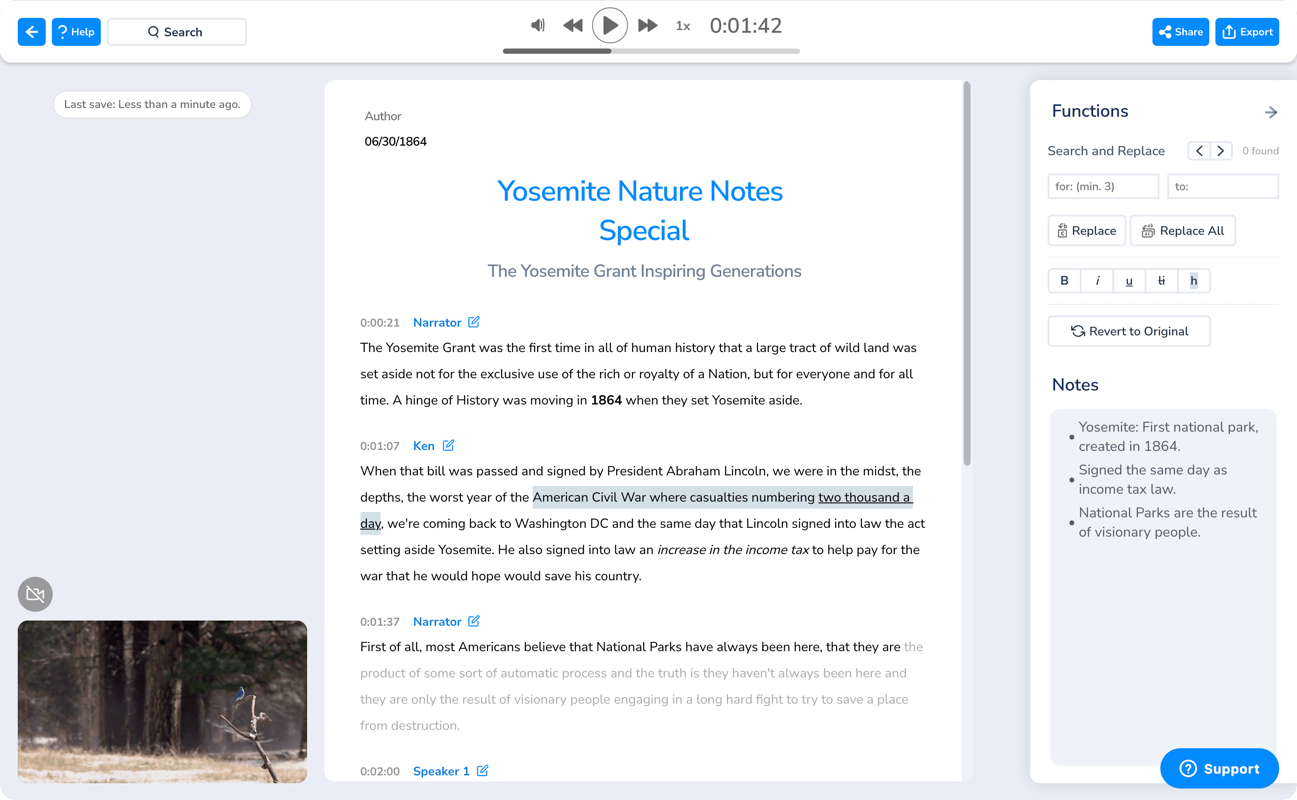

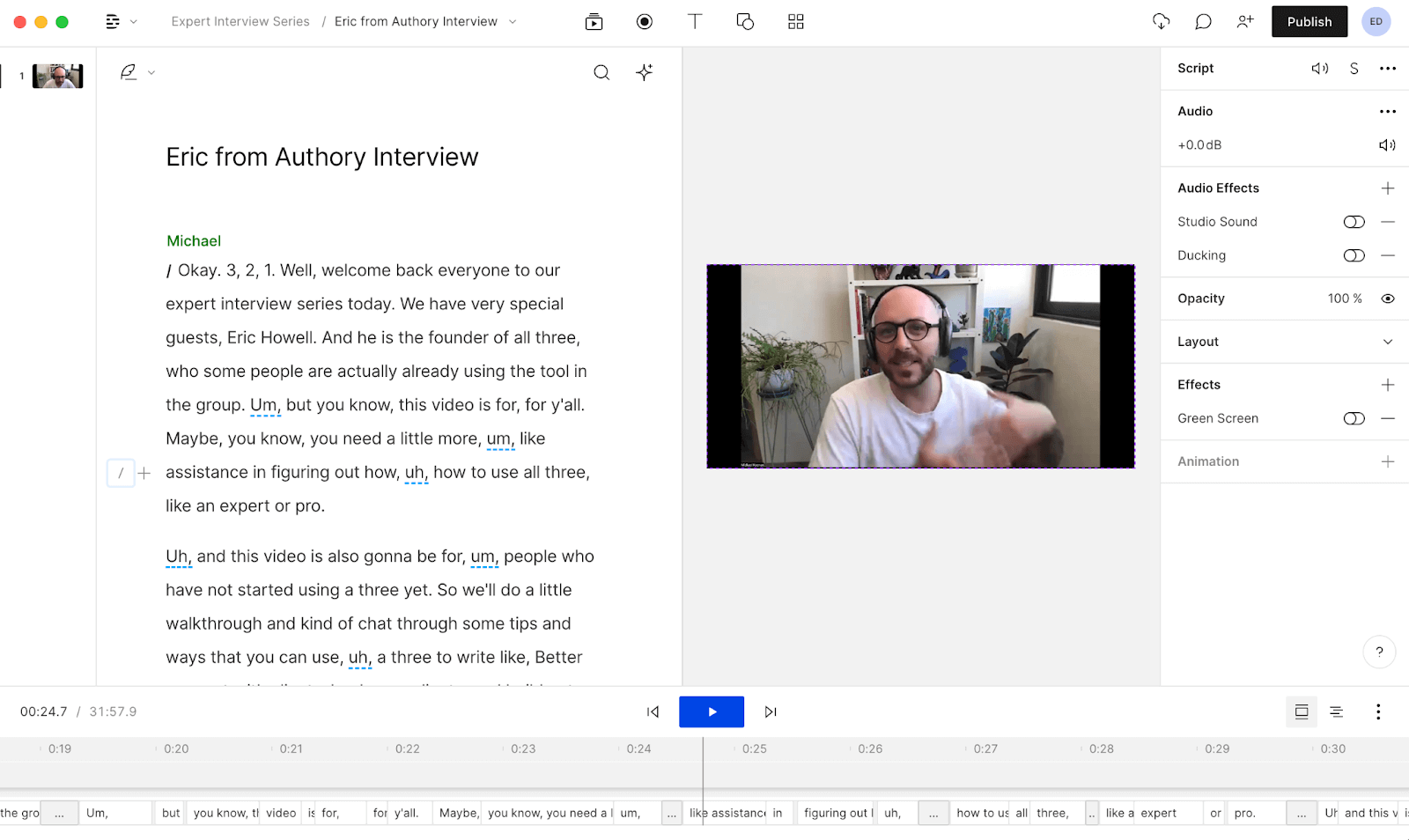

Transcribing Interviews with Maestra Step-by-Step

If you’re looking for a tool with all these features, then Maestra’s AI-powered interview transcription software is the right choice for you. You can get your transcript instantly by following a few simple steps.

- Upload your audio or video file. Maestra supports 125+ languages .

- Select audio language and receive the transcript in seconds.

Custom dictionary is especially beneficial when transcribing interviews for research as the audio content is more likely to include technical terminology. With this feature, you can add specific terms to your custom dictionary, assign importance values and Maestra will transcribe them as specified, ensuring accuracy.

You can also select the number of speakers during the upload phase and assign names to each speaker, making it easier to navigate the transcript.

- Click “Submit” and witness AI transcription work its magic. You will instantly receive your interview transcript with timestamps and speaker tags.

- Ta-da! You can now proofread and edit your transcript, take notes and add comments with Maestra’s built-in text editor .

Maestra has a very high accuracy rate but you can always polish your document for maximum clarity and comprehensibility.

After transcribing interviews, you can safely reach and organize them via MaestraCloud . You can also store your interview recordings here as the cloud allows you to keep audio and video files of any size without time limitations.

Collaborating with fellow researchers? Maestra Teams is ready to help you. You can create team-based channels with different permission levels and edit the document with other researchers in real-time.

Tips for Transcribing Interviews for Qualitative Research

No matter your experience in qualitative research or the software you use, there are certain practices to adopt when transcribing interviews.

Use a High-Quality Recording Device

Utilizing a high-quality recording device lays a solid foundation for interview transcription. Invest in a reliable recorder with good microphone sensitivity and audio quality to capture every part of the conversation. Don’t forget to test your equipment beforehand to avoid potential technical issues during the interview.

Respect Confidentiality

Upholding confidentiality is paramount when transcribing interviews for qualitative research. Always obtain informed consent from participants for recording and transcription, and store your files securely. Avoid sharing any personally identifiable information to safeguard participant privacy and maintain the integrity of your research.

Include Speaker Identification and Time Stamps

This practice enhances the overall usability of an interview transcript by enabling easy reference to specific points. Make sure you clearly identify each speaker on the document either by name, role or pseudonym. You can use different fonts or colors to visually distinguish between speakers.

Follow the Specific Style Consistently

Choose a transcription style guide (verbatim, intelligent verbatim, etc.) and follow it consistently throughout the project. Define rules for punctuation, contractions and interruptions. This will guarantee uniformity and enhance the reliability of your findings.

Add Non-Verbal Cues and Annotations

This one is not mandatory but can provide valuable context. You can document non-verbal expressions, pauses or changes in tone to add depth to qualitative data analysis. Meanwhile, bracketed annotations can help you highlight important moments. Just remember that adding too much detail can be distracting, so only include relevant information.

Edit and Proofread the Transcript

Proofread and edit your document once transcribing an interview: correct any errors, format inconsistencies and review for readability. Double check speaker identification and timestamps for accuracy. These practices will ensure a smooth transition from transcription to analysis and publication.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is transcription necessary for qualitative research.

The necessity of transcription depends on the nature and goals of the qualitative research you conduct. For example, it is crucial for in-depth and focus group interviews but not essential for participant observation where researchers can rely on field notes.

How do you transcribe an anonymous interview?

When transcribing interviews with anonymous participants, remove any information that can directly or indirectly identify the participant such as name, nickname, location, job title and affiliations. Create neutral pseudonyms (Participant 1, Interviewee A, etc.) for the participant and use them consistently throughout the interview transcript.

How do you analyze interview transcripts in qualitative research?

First, familiarize yourself with the data through readings when analyzing an interview transcript for research . Then, assign codes to relevant segments and organize similar codes into broader recurring themes. Finally, present your findings via a structured narrative. Always maintain transparency during the process.

How do you transcribe an interview in APA format?

Transcripts of interviews are usually added to the appendix in APA format . You should use a specific header with interview details, double line spacing and speaker identifiers in the transcript.

How do you summarize an interview transcript?

Carefully read the content and identify key themes when summarizing the transcript of an interview . Organize the information logically, provide brief contextual details when necessary and use quotes to add impact. Capture the essence of the interview by keeping the summary short and sweet.

Interview transcription is particularly valuable in qualitative research, which delves deep into human experiences and perceptions. Transforming spoken words into text enables researchers to derive meaningful insights from the rich tapestry of qualitative data. It also increases the accessibility of the research, empowering scholars to collaborate with colleagues across disciplines and borders.

The advent of AI technology revolutionized the process of transcribing interviews and will continue to do so in the future. Its benefits range from increased accuracy to cost-effectiveness, providing a much refined experience for researchers. By choosing the right software and adopting the best practices for transcribing interviews, researchers can unleash the full potential of their endeavors.

About Serra Ardem

Serra Ardem is a freelance writer and editor based in Istanbul. For the last 8 years, she has been collaborating with brands and businesses to tell their unique story and develop their verbal identity.

What are you looking for?

Quick links.

Click here to find all our contact information

Transcribing interviews for research

Transcription involves making a written record of speech. This can be done during an actual interview or carried out afterwards using an audio or video file.

Why transcribe interviews during research?

Transcribing interviews that are carried out for research is good practice. Interviews that are transcribed verbatim in qualitative research allow analysis of the collected responses in greater detail at a later date. It also leaves less room for bias caused by the researcher’s personal interpretation.

Researchers can read and re-read interview transcriptions, identify themes and patterns, and extract key quotes or phrases. This process helps to identify significant points, which can then help to draw meaningful conclusions.

Transcribing interviews for research is also useful because it helps researchers check that their interpretation of the conversation is accurate, so reduces errors or misinterpretations. The transcription provides a permanent record of the interview, which can be referred to by other people in the future to confirm any findings.

Interview transcription can also help to ensure the anonymity of the participants. By removing identifying information from the transcriptions, researchers can protect the privacy of the participants. This often makes people more willing to take part in research interviews.

Another benefit is that interview transcription can be easily shared among researchers. This facilitates analysis and collaboration, which further contributes to the reliability and validity of the research.

Full audio and video transcription solutions

How to transcribe manually.

Transcribing a recorded interview manually is time-consuming and it’s vital to make sure it’s done correctly. Here are some steps to follow if you’re considering transcribing interviews for research:

- Before starting the transcription process, listen to the recording to familiarise yourself with the voices, accents and any background noises that might affect the transcription process.

- Create a transcription template that includes the speakers’ names or identifiers, timestamps (if required) and space for the transcribed audio text.

- Start transcribing the interview by listening to a few seconds of the recording, pausing and then typing out what was said. It’s important to be accurate, and to include all the spoken words. Also be sure to include filler words, such as ‘um’ and ‘ah’ and any non-spoken communication, such as laughter or pauses if needed. Find out more about different types of transcription .

- Once the transcription is complete, spend time editing to ensure accuracy and readability. Make sure you have correctly identified the speakers and that any timestamps are accurate.

Download our free transcription template

Get started with transcription. Here you will find templates for both detailed transcription and standard transcription . You can use the formats and examples in your own working document.

Tools for creating automatic transcriptions

Manual interview transcription is incredibly time-consuming. However, there are several software apps available that offer free interview subscription or paid-for services. Here are some of the most popular:

- Otter.ai: Otter.ai is a popular transcription app that uses AI to transcribe interviews in real-time. It offers a free plan that allows users to transcribe up to 600 minutes of audio per month. There are paid-for plans available for higher use.

- Temi : Temi is an automated transcription service that offers both free and paid-for plans. The free plan allows users to transcribe up to 45 minutes of audio per month.

- Trint : Trint uses AI to transcribe audio and video files. It offers a free trial and paid-for plans.

- Happy Scribe : Happy Scribe is another transcription software tool that uses AI to transcribe audio and video files. It has some pretty impressive user reviews and offers a free trial and paid-for plans for higher usage.

- Speechmatics : Speechmatics is speech recognition software that offers an automatic transcription service and can also be integrated with other systems. It offers a free trial and subscription plans.

Automatic transcription software is undoubtedly convenient and time-saving. However, it might not always be accurate. At the very least, all automatic interview transcriptions should be manually checked.

Here’s what an interview transcription for research might look like

Interviewer: Can you tell me about your experience using language learning products?

Participant: OK. [inhales deeply] So, I’ve tried more than a few different products, mostly apps on my phone and tablet, and I’ve found that they can be helpful, but also frustrating at times. I also tend to lose interest in them after a while.

Interviewer: Can you tell me about a time when you found a language learning product helpful?

Participant: Yeah, so I was using this one app to learn Spanish, and it had a feature where you could record yourself speaking and then listen back to it. I found that really helpful because it helped me hear my mistakes and work on my pronunciation. It was awful listening to myself speak though. [laughs]

Interviewer: [laughs] That’s interesting. Can you tell me about a time when you found a language learning product more frustrating?

Participant: Yeah, so I was using another app to learn French, and it was just really baffling and such a waste of time. The lessons were all over the place, and the exercises didn’t seem to match up with what I was learning. It was really frustrating and demotivating. I ended up giving up after a couple of weeks and it really put me off to be honest. [sighs]

Interviewer: I see. Can you tell me about any features of the language learning apps you’ve tried that you particularly like or dislike?

Participant : I really like it when the app has a feature where you can practise speaking with a native speaker. It’s really helpful to get feedback and practise in a more natural way. On the other hand, I don't like it when the app is too repetitive or doesn’t have different exercises and that. I end up just chucking it. [intonation rises]

Interviewer: Thank you for sharing your thoughts and experiences. [laughter]

Participant: No problem, happy to help.

What if I need an APA interview transcript?

Transcribing an interview can be done manually. At the moment, it’s not possible for AI transcribers to do this. You should format your transcription to the style required by your organisation. Include the transcript as an appendix or as a reference in the body of your text. Appropriate referencing systems include APA, Harvard, MLA etc. Learn more about academic referencing styles.

Final thoughts

Transcribing interviews for research is one of the best ways of creating a permanent record of the data that’s gathered. It can then be shared with colleagues and analysed in the future. However, it’s a labour-intensive task, and sometimes it’s important to capture every word spoken, every inflection and even communication that comes from unspoken cues, such as laughter or vocal intonation.

Semantix’s multilingual transcribers can transcribe your interviews quickly and accurately, and they work in more than 170 languages. If you’d like to talk to us about our confidential transcription services , fill in the form and we’ll be in touch.

Would you like to order a transcription?

Download templates for both detailed transcription and standard transcription. You can use the formats and examples in your own working document.

Related content

How to transcribe audio to text – the ultimate guide to transcription

Transcription rules and types

What does a transcriber do?

Why You Should Transcribe Interviews For a Better Qualitative Research

How to transcribe an interview in 5 simple steps (2024)

What type of content do you primarily create?

So you’ve finished an interview recording .

Whether you’re using that conversation in an article or a research project or editing it into a video or podcast, it’s time to transcribe it.

Where do you start? You start by typing “how to transcribe an interview” into Google, but you probably already did, and that’s what brought you here. Hi!

Anyway, you’re in the right place, because Descript will automatically transcribe your interview (and let you edit the audio or video right from the transcript). But if you want to learn more about different transcription options, here’s what you need to know.

What is an interview transcript?

An interview transcript is an audio track converted into text so people can read it. Before you start transcribing, it’s worth considering the transcript’s ultimate purpose.

- Are you using the interview as a research source? If you just want to drain your subject’s brain with interview questions , and their exact quotes don’t matter, you don’t have to waste your time with an intelligent verbatim transcription. A quick and dirty job will do.

- Will you be quoting your subject for publication? People don’t typically like being misquoted. Yet, it rarely reads well when people are quoted exactly as they speak in real life. You’ll likely want to split the difference: Go through that audio with a fine-tooth comb, get it down as faithfully as you can, and eliminate all the “ums,” “ahs,” and unnecessary “I means.” No one will fault you for making them sound more articulate.

- Is every single word, pause, and false start important? You’ll have to do a full verbatim transcript. When details count, they really count, so having every detail from your interview will be helpful for your project.

How to transcribe an interview, the easy way

1. get transcription software.

Praise the robots, for they allow us to save time.

Not only is a lot of transcription software free (or free to a point), but it also takes the drudgery out of the transcription process. Some errors and typos are inevitable, so you’ll want to edit the text afterward, even if you use a high-quality transcriber like Descript.

Descript automatically transcribes any file you import; just drag your audio into the app, wait a few seconds, and you’ll have a complete transcript.

That, in our very biased opinion, makes Descript the best transcription service, hands down. But here are some other transcription tools:

- Otter. Otter is a workplace tool to transcribe meetings and follow up with any actionable items easily. But you could also just as easily use it to transcribe your interviews in real time. Otter uses AI to automatically separate speakers and transcribe as your interview happens, and the basic features are free. You'll have to upgrade to get more advanced functions, like importing files for transcription. Plans start at $8.33/month.

- Amberscript: Amberscript, another AI-based transcription software, also offers translation and human editing services. The downside is that you only get 10 minutes of automatic transcription free. Beyond that, you’ll need to pay $10 per hour of audio.

- Scribie: For automatic transcription, Scribie claims to reach over 80% accuracy and only costs 10 cents per minute. That’s definitely good for the price point, though for the interviewer on the go, it’s worth noting that the service doesn’t have a mobile app.

2. Upload your audio or video file

Open your Descript app, then click New project in the upper right corner.

On the following screen, name your project and click Choose a file to transcribe.

Choose your file.

After selecting open, Descript will automatically transcribe your audio or video file.

3. Add speakers

Next, Descript will ask you to identify the speakers in your file. If it’s just you and another interviewee, select two from the dropdown menu.

Descript will then ask you to identify each speaker. We'll play you a short clip from your file, and you'll type in the speaker's name.

Then click Add “ Name ” as speaker. Easy peasy!

4. Clarify the transcript as needed

Now you’ve got a transcript ready for editing.

You probably see some mistakes already. With Descript, you can edit your audio by editing the text in the transcript.

If you don’t like a word or sentence in your transcript, highlight it and press delete on your keyboard. You can also correct words and punctuation quickly with a few handy keyboard shortcuts .

You can also choose to automatically correct any mistakes the AI made. Access them in the upper right hand corner of your transcript.

You’ll find shortcuts like:

- Shorten word gaps. Remove long periods of silence from your recording automatically. Set how many seconds (or more) of gaps to fill, then reduce them to whatever you want.

- Remove filler words. Descript will automatically remove filler words like "you know," "well," or “um”. It can also remove stutters and repetitions.

- Detect transcription errors. Clean up your transcript quickly with this tool. Click this button and Descript will highlight probable recording errors for your review.

5. Export the transcript and proofread

At this point, you’ve got a clean transcript ready to go. The last step here is to export the transcript and give it a good proofread.

First, click the Publish button in the top right corner of your screen. Click the Export tab and then the Transcript button .

Before exporting the file, you can choose to include:

- Composition name