Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

What is a thesis | A Complete Guide with Examples

Table of Contents

A thesis is a comprehensive academic paper based on your original research that presents new findings, arguments, and ideas of your study. It’s typically submitted at the end of your master’s degree or as a capstone of your bachelor’s degree.

However, writing a thesis can be laborious, especially for beginners. From the initial challenge of pinpointing a compelling research topic to organizing and presenting findings, the process is filled with potential pitfalls.

Therefore, to help you, this guide talks about what is a thesis. Additionally, it offers revelations and methodologies to transform it from an overwhelming task to a manageable and rewarding academic milestone.

What is a thesis?

A thesis is an in-depth research study that identifies a particular topic of inquiry and presents a clear argument or perspective about that topic using evidence and logic.

Writing a thesis showcases your ability of critical thinking, gathering evidence, and making a compelling argument. Integral to these competencies is thorough research, which not only fortifies your propositions but also confers credibility to your entire study.

Furthermore, there's another phenomenon you might often confuse with the thesis: the ' working thesis .' However, they aren't similar and shouldn't be used interchangeably.

A working thesis, often referred to as a preliminary or tentative thesis, is an initial version of your thesis statement. It serves as a draft or a starting point that guides your research in its early stages.

As you research more and gather more evidence, your initial thesis (aka working thesis) might change. It's like a starting point that can be adjusted as you learn more. It's normal for your main topic to change a few times before you finalize it.

While a thesis identifies and provides an overarching argument, the key to clearly communicating the central point of that argument lies in writing a strong thesis statement.

What is a thesis statement?

A strong thesis statement (aka thesis sentence) is a concise summary of the main argument or claim of the paper. It serves as a critical anchor in any academic work, succinctly encapsulating the primary argument or main idea of the entire paper.

Typically found within the introductory section, a strong thesis statement acts as a roadmap of your thesis, directing readers through your arguments and findings. By delineating the core focus of your investigation, it offers readers an immediate understanding of the context and the gravity of your study.

Furthermore, an effectively crafted thesis statement can set forth the boundaries of your research, helping readers anticipate the specific areas of inquiry you are addressing.

Different types of thesis statements

A good thesis statement is clear, specific, and arguable. Therefore, it is necessary for you to choose the right type of thesis statement for your academic papers.

Thesis statements can be classified based on their purpose and structure. Here are the primary types of thesis statements:

Argumentative (or Persuasive) thesis statement

Purpose : To convince the reader of a particular stance or point of view by presenting evidence and formulating a compelling argument.

Example : Reducing plastic use in daily life is essential for environmental health.

Analytical thesis statement

Purpose : To break down an idea or issue into its components and evaluate it.

Example : By examining the long-term effects, social implications, and economic impact of climate change, it becomes evident that immediate global action is necessary.

Expository (or Descriptive) thesis statement

Purpose : To explain a topic or subject to the reader.

Example : The Great Depression, spanning the 1930s, was a severe worldwide economic downturn triggered by a stock market crash, bank failures, and reduced consumer spending.

Cause and effect thesis statement

Purpose : To demonstrate a cause and its resulting effect.

Example : Overuse of smartphones can lead to impaired sleep patterns, reduced face-to-face social interactions, and increased levels of anxiety.

Compare and contrast thesis statement

Purpose : To highlight similarities and differences between two subjects.

Example : "While both novels '1984' and 'Brave New World' delve into dystopian futures, they differ in their portrayal of individual freedom, societal control, and the role of technology."

When you write a thesis statement , it's important to ensure clarity and precision, so the reader immediately understands the central focus of your work.

What is the difference between a thesis and a thesis statement?

While both terms are frequently used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

A thesis refers to the entire research document, encompassing all its chapters and sections. In contrast, a thesis statement is a brief assertion that encapsulates the central argument of the research.

Here’s an in-depth differentiation table of a thesis and a thesis statement.

Now, to craft a compelling thesis, it's crucial to adhere to a specific structure. Let’s break down these essential components that make up a thesis structure

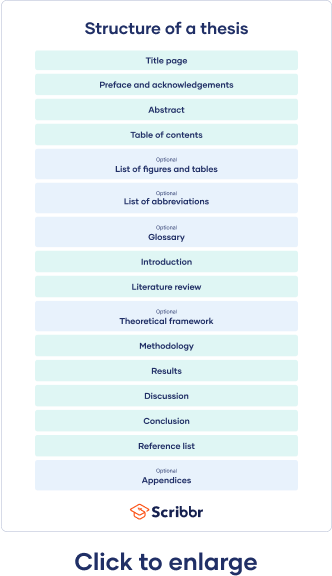

15 components of a thesis structure

Navigating a thesis can be daunting. However, understanding its structure can make the process more manageable.

Here are the key components or different sections of a thesis structure:

Your thesis begins with the title page. It's not just a formality but the gateway to your research.

Here, you'll prominently display the necessary information about you (the author) and your institutional details.

- Title of your thesis

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date

- Your Supervisor's name (in some cases)

- Your Department or faculty (in some cases)

- Your University's logo (in some cases)

- Your Student ID (in some cases)

In a concise manner, you'll have to summarize the critical aspects of your research in typically no more than 200-300 words.

This includes the problem statement, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. For many, the abstract will determine if they delve deeper into your work, so ensure it's clear and compelling.

Acknowledgments

Research is rarely a solitary endeavor. In the acknowledgments section, you have the chance to express gratitude to those who've supported your journey.

This might include advisors, peers, institutions, or even personal sources of inspiration and support. It's a personal touch, reflecting the humanity behind the academic rigor.

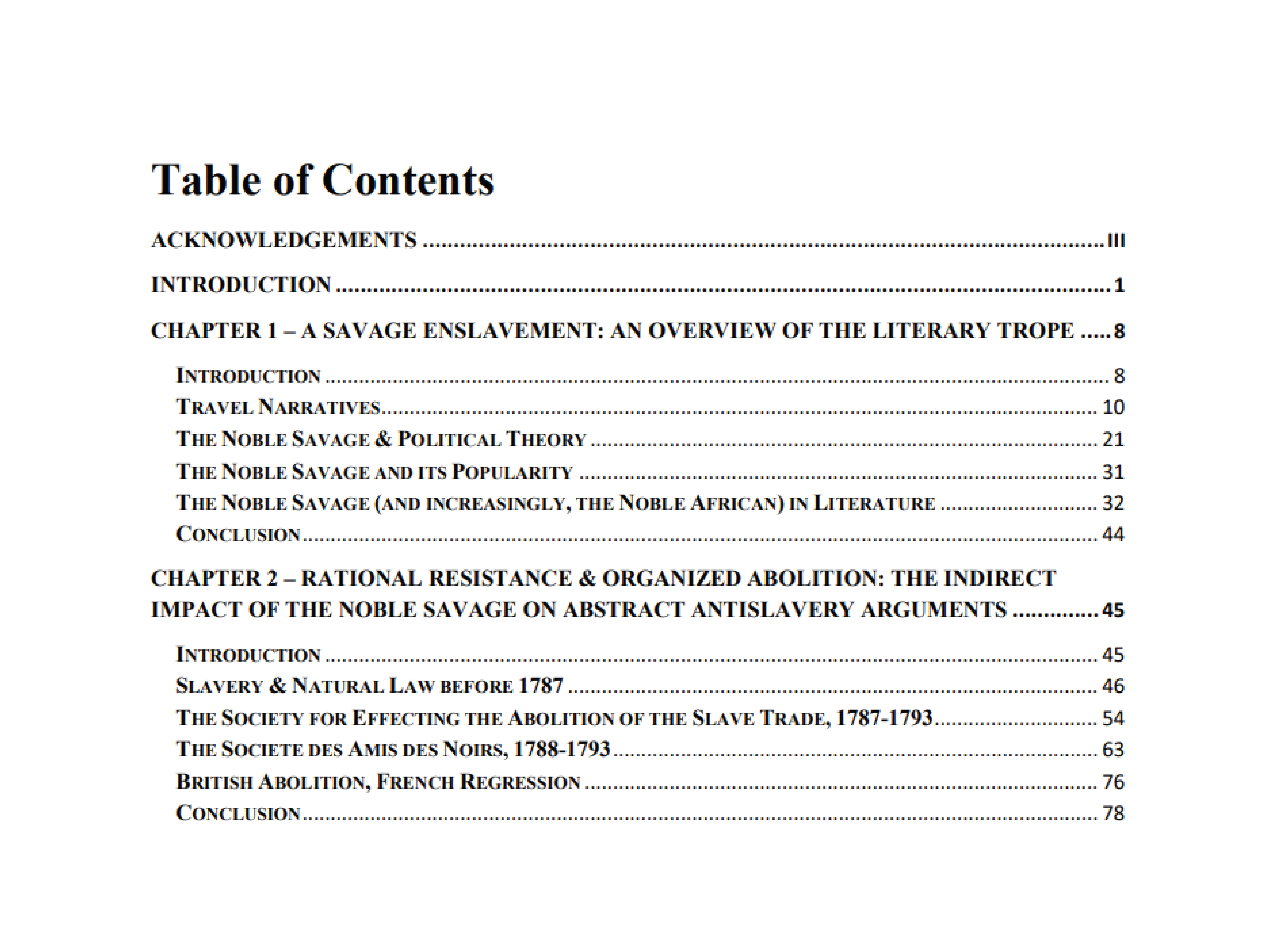

Table of contents

A roadmap for your readers, the table of contents lists the chapters, sections, and subsections of your thesis.

By providing page numbers, you allow readers to navigate your work easily, jumping to sections that pique their interest.

List of figures and tables

Research often involves data, and presenting this data visually can enhance understanding. This section provides an organized listing of all figures and tables in your thesis.

It's a visual index, ensuring that readers can quickly locate and reference your graphical data.

Introduction

Here's where you introduce your research topic, articulate the research question or objective, and outline the significance of your study.

- Present the research topic : Clearly articulate the central theme or subject of your research.

- Background information : Ground your research topic, providing any necessary context or background information your readers might need to understand the significance of your study.

- Define the scope : Clearly delineate the boundaries of your research, indicating what will and won't be covered.

- Literature review : Introduce any relevant existing research on your topic, situating your work within the broader academic conversation and highlighting where your research fits in.

- State the research Question(s) or objective(s) : Clearly articulate the primary questions or objectives your research aims to address.

- Outline the study's structure : Give a brief overview of how the subsequent sections of your work will unfold, guiding your readers through the journey ahead.

The introduction should captivate your readers, making them eager to delve deeper into your research journey.

Literature review section

Your study correlates with existing research. Therefore, in the literature review section, you'll engage in a dialogue with existing knowledge, highlighting relevant studies, theories, and findings.

It's here that you identify gaps in the current knowledge, positioning your research as a bridge to new insights.

To streamline this process, consider leveraging AI tools. For example, the SciSpace literature review tool enables you to efficiently explore and delve into research papers, simplifying your literature review journey.

Methodology

In the research methodology section, you’ll detail the tools, techniques, and processes you employed to gather and analyze data. This section will inform the readers about how you approached your research questions and ensures the reproducibility of your study.

Here's a breakdown of what it should encompass:

- Research Design : Describe the overall structure and approach of your research. Are you conducting a qualitative study with in-depth interviews? Or is it a quantitative study using statistical analysis? Perhaps it's a mixed-methods approach?

- Data Collection : Detail the methods you used to gather data. This could include surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, etc. Mention where you sourced your data, the duration of data collection, and any tools or instruments used.

- Sampling : If applicable, explain how you selected participants or data sources for your study. Discuss the size of your sample and the rationale behind choosing it.

- Data Analysis : Describe the techniques and tools you used to process and analyze the data. This could range from statistical tests in quantitative research to thematic analysis in qualitative research.

- Validity and Reliability : Address the steps you took to ensure the validity and reliability of your findings to ensure that your results are both accurate and consistent.

- Ethical Considerations : Highlight any ethical issues related to your research and the measures you took to address them, including — informed consent, confidentiality, and data storage and protection measures.

Moreover, different research questions necessitate different types of methodologies. For instance:

- Experimental methodology : Often used in sciences, this involves a controlled experiment to discern causality.

- Qualitative methodology : Employed when exploring patterns or phenomena without numerical data. Methods can include interviews, focus groups, or content analysis.

- Quantitative methodology : Concerned with measurable data and often involves statistical analysis. Surveys and structured observations are common tools here.

- Mixed methods : As the name implies, this combines both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

The Methodology section isn’t just about detailing the methods but also justifying why they were chosen. The appropriateness of the methods in addressing your research question can significantly impact the credibility of your findings.

Results (or Findings)

This section presents the outcomes of your research. It's crucial to note that the nature of your results may vary; they could be quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both.

Quantitative results often present statistical data, showcasing measurable outcomes, and they benefit from tables, graphs, and figures to depict these data points.

Qualitative results , on the other hand, might delve into patterns, themes, or narratives derived from non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations.

Regardless of the nature of your results, clarity is essential. This section is purely about presenting the data without offering interpretations — that comes later in the discussion.

In the discussion section, the raw data transforms into valuable insights.

Start by revisiting your research question and contrast it with the findings. How do your results expand, constrict, or challenge current academic conversations?

Dive into the intricacies of the data, guiding the reader through its implications. Detail potential limitations transparently, signaling your awareness of the research's boundaries. This is where your academic voice should be resonant and confident.

Practical implications (Recommendation) section

Based on the insights derived from your research, this section provides actionable suggestions or proposed solutions.

Whether aimed at industry professionals or the general public, recommendations translate your academic findings into potential real-world actions. They help readers understand the practical implications of your work and how it can be applied to effect change or improvement in a given field.

When crafting recommendations, it's essential to ensure they're feasible and rooted in the evidence provided by your research. They shouldn't merely be aspirational but should offer a clear path forward, grounded in your findings.

The conclusion provides closure to your research narrative.

It's not merely a recap but a synthesis of your main findings and their broader implications. Reconnect with the research questions or hypotheses posited at the beginning, offering clear answers based on your findings.

Reflect on the broader contributions of your study, considering its impact on the academic community and potential real-world applications.

Lastly, the conclusion should leave your readers with a clear understanding of the value and impact of your study.

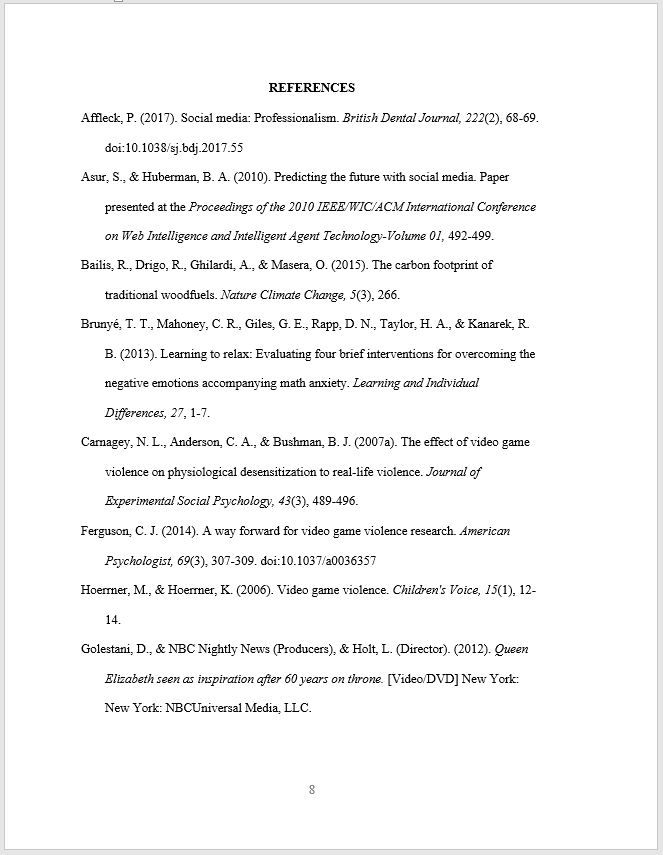

References (or Bibliography)

Every theory you've expounded upon, every data point you've cited, and every methodological precedent you've followed finds its acknowledgment here.

In references, it's crucial to ensure meticulous consistency in formatting, mirroring the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style .

Proper referencing helps to avoid plagiarism , gives credit to original ideas, and allows readers to explore topics of interest. Moreover, it situates your work within the continuum of academic knowledge.

To properly cite the sources used in the study, you can rely on online citation generator tools to generate accurate citations!

Here’s more on how you can cite your sources.

Often, the depth of research produces a wealth of material that, while crucial, can make the core content of the thesis cumbersome. The appendix is where you mention extra information that supports your research but isn't central to the main text.

Whether it's raw datasets, detailed procedural methodologies, extended case studies, or any other ancillary material, the appendices ensure that these elements are archived for reference without breaking the main narrative's flow.

For thorough researchers and readers keen on meticulous details, the appendices provide a treasure trove of insights.

Glossary (optional)

In academics, specialized terminologies, and jargon are inevitable. However, not every reader is versed in every term.

The glossary, while optional, is a critical tool for accessibility. It's a bridge ensuring that even readers from outside the discipline can access, understand, and appreciate your work.

By defining complex terms and providing context, you're inviting a wider audience to engage with your research, enhancing its reach and impact.

Remember, while these components provide a structured framework, the essence of your thesis lies in the originality of your ideas, the rigor of your research, and the clarity of your presentation.

As you craft each section, keep your readers in mind, ensuring that your passion and dedication shine through every page.

Thesis examples

To further elucidate the concept of a thesis, here are illustrative examples from various fields:

Example 1 (History): Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807 by Suchait Kahlon.

Example 2 (Climate Dynamics): Influence of external forcings on abrupt millennial-scale climate changes: a statistical modelling study by Takahito Mitsui · Michel Crucifix

Checklist for your thesis evaluation

Evaluating your thesis ensures that your research meets the standards of academia. Here's an elaborate checklist to guide you through this critical process.

Content and structure

- Is the thesis statement clear, concise, and debatable?

- Does the introduction provide sufficient background and context?

- Is the literature review comprehensive, relevant, and well-organized?

- Does the methodology section clearly describe and justify the research methods?

- Are the results/findings presented clearly and logically?

- Does the discussion interpret the results in light of the research question and existing literature?

- Is the conclusion summarizing the research and suggesting future directions or implications?

Clarity and coherence

- Is the writing clear and free of jargon?

- Are ideas and sections logically connected and flowing?

- Is there a clear narrative or argument throughout the thesis?

Research quality

- Is the research question significant and relevant?

- Are the research methods appropriate for the question?

- Is the sample size (if applicable) adequate?

- Are the data analysis techniques appropriate and correctly applied?

- Are potential biases or limitations addressed?

Originality and significance

- Does the thesis contribute new knowledge or insights to the field?

- Is the research grounded in existing literature while offering fresh perspectives?

Formatting and presentation

- Is the thesis formatted according to institutional guidelines?

- Are figures, tables, and charts clear, labeled, and referenced in the text?

- Is the bibliography or reference list complete and consistently formatted?

- Are appendices relevant and appropriately referenced in the main text?

Grammar and language

- Is the thesis free of grammatical and spelling errors?

- Is the language professional, consistent, and appropriate for an academic audience?

- Are quotations and paraphrased material correctly cited?

Feedback and revision

- Have you sought feedback from peers, advisors, or experts in the field?

- Have you addressed the feedback and made the necessary revisions?

Overall assessment

- Does the thesis as a whole feel cohesive and comprehensive?

- Would the thesis be understandable and valuable to someone in your field?

Ensure to use this checklist to leave no ground for doubt or missed information in your thesis.

After writing your thesis, the next step is to discuss and defend your findings verbally in front of a knowledgeable panel. You’ve to be well prepared as your professors may grade your presentation abilities.

Preparing your thesis defense

A thesis defense, also known as "defending the thesis," is the culmination of a scholar's research journey. It's the final frontier, where you’ll present their findings and face scrutiny from a panel of experts.

Typically, the defense involves a public presentation where you’ll have to outline your study, followed by a question-and-answer session with a committee of experts. This committee assesses the validity, originality, and significance of the research.

The defense serves as a rite of passage for scholars. It's an opportunity to showcase expertise, address criticisms, and refine arguments. A successful defense not only validates the research but also establishes your authority as a researcher in your field.

Here’s how you can effectively prepare for your thesis defense .

Now, having touched upon the process of defending a thesis, it's worth noting that scholarly work can take various forms, depending on academic and regional practices.

One such form, often paralleled with the thesis, is the 'dissertation.' But what differentiates the two?

Dissertation vs. Thesis

Often used interchangeably in casual discourse, they refer to distinct research projects undertaken at different levels of higher education.

To the uninitiated, understanding their meaning might be elusive. So, let's demystify these terms and delve into their core differences.

Here's a table differentiating between the two.

Wrapping up

From understanding the foundational concept of a thesis to navigating its various components, differentiating it from a dissertation, and recognizing the importance of proper citation — this guide covers it all.

As scholars and readers, understanding these nuances not only aids in academic pursuits but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the relentless quest for knowledge that drives academia.

It’s important to remember that every thesis is a testament to curiosity, dedication, and the indomitable spirit of discovery.

Good luck with your thesis writing!

Frequently Asked Questions

A thesis typically ranges between 40-80 pages, but its length can vary based on the research topic, institution guidelines, and level of study.

A PhD thesis usually spans 200-300 pages, though this can vary based on the discipline, complexity of the research, and institutional requirements.

To identify a thesis topic, consider current trends in your field, gaps in existing literature, personal interests, and discussions with advisors or mentors. Additionally, reviewing related journals and conference proceedings can provide insights into potential areas of exploration.

The conceptual framework is often situated in the literature review or theoretical framework section of a thesis. It helps set the stage by providing the context, defining key concepts, and explaining the relationships between variables.

A thesis statement should be concise, clear, and specific. It should state the main argument or point of your research. Start by pinpointing the central question or issue your research addresses, then condense that into a single statement, ensuring it reflects the essence of your paper.

You might also like

AI for Meta Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

Cybersecurity in Higher Education: Safeguarding Students and Faculty Data

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

While Sandel argues that pursuing perfection through genetic engineering would decrease our sense of humility, he claims that the sense of solidarity we would lose is also important.

This thesis summarizes several points in Sandel’s argument, but it does not make a claim about how we should understand his argument. A reader who read Sandel’s argument would not also need to read an essay based on this descriptive thesis.

Broad thesis (arguable, but difficult to support with evidence)

Michael Sandel’s arguments about genetic engineering do not take into consideration all the relevant issues.

This is an arguable claim because it would be possible to argue against it by saying that Michael Sandel’s arguments do take all of the relevant issues into consideration. But the claim is too broad. Because the thesis does not specify which “issues” it is focused on—or why it matters if they are considered—readers won’t know what the rest of the essay will argue, and the writer won’t know what to focus on. If there is a particular issue that Sandel does not address, then a more specific version of the thesis would include that issue—hand an explanation of why it is important.

Arguable thesis with analytical claim

While Sandel argues persuasively that our instinct to “remake” (54) ourselves into something ever more perfect is a problem, his belief that we can always draw a line between what is medically necessary and what makes us simply “better than well” (51) is less convincing.

This is an arguable analytical claim. To argue for this claim, the essay writer will need to show how evidence from the article itself points to this interpretation. It’s also a reasonable scope for a thesis because it can be supported with evidence available in the text and is neither too broad nor too narrow.

Arguable thesis with normative claim

Given Sandel’s argument against genetic enhancement, we should not allow parents to decide on using Human Growth Hormone for their children.

This thesis tells us what we should do about a particular issue discussed in Sandel’s article, but it does not tell us how we should understand Sandel’s argument.

Questions to ask about your thesis

- Is the thesis truly arguable? Does it speak to a genuine dilemma in the source, or would most readers automatically agree with it?

- Is the thesis too obvious? Again, would most or all readers agree with it without needing to see your argument?

- Is the thesis complex enough to require a whole essay's worth of argument?

- Is the thesis supportable with evidence from the text rather than with generalizations or outside research?

- Would anyone want to read a paper in which this thesis was developed? That is, can you explain what this paper is adding to our understanding of a problem, question, or topic?

- picture_as_pdf Thesis

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

University Writing Center

University writing center blog, the working thesis.

by Alexandra Makris, Peer Consultant, University Writing Center

One of my favorite conventions in writing that I have learned in college is the concept of the working thesis.

What is a thesis, you ask?

I will explain, happily (is there any other emotion to have when explaining a thesis statement? Considering it is about 30% of my job as a writing consultant, no).

A thesis statement is a claim that you are going to back up throughout your paper. It should be something with which someone else can plausibly disagree without sounding silly. For instance, if you begin an argumentative essay with the sentence “Chicago is located in Illinois, which is a state in the United States of America,” the main response you would get is “Yes, yes it is.”

The claim is something other than mere facts. It is a stance, a view, a flag upheld in a battlefield of contrary forces.

A working thesis is a beautiful concept that should find a comfortable place in your academic vocabulary. Properly considered, it will save you both time and stress. It is essentially a work-in-progress thesis, which is helpful because often we do not know exactly what we want to say until we have gotten further into the research and the writing process.

It is perfectly acceptable to have your working thesis loose, with imprecise and general language. I often find in a tutoring session that one of the first steps is reassuring the student that getting a perfect thesis statement the first time you write it is utterly unrealistic. It does not happen to us mere mortals, and revision is a necessary part of improving your writing.

The purpose of the working thesis is to give structure to your writing as you begin, rather than trying to create a unifying thesis after finishing your paper entirely. This way, as you write, you can constantly return to the thesis and ask yourself, “Does it fit with the purpose of my paper?” Writing, whether academic or not, has specific purposes, and all details and support ought to relate to that purpose. If you are writing a persuasive paper on the topic of gun control on school campuses in Indiana, including commentary on rising school tuition or the lack of parking on campuses does not help your cause. Those topics could potentially overlap, but you would have to make that overlap an intentional action rather than a tangential detour. If, as you are writing, a brilliant point of analysis comes to fruition that is not covered by your working thesis, consider reworking the thesis to include it.

Happy writing, and feel free to come see us in the writing center any time.

Featured Story

Writing center blog.

- Three Commonalities of any Writing Center Session – Part 2

- Three Commonalities of any Writing Center Session – Part 1

- Delayed Writers: What Students Can Do to Get Back into Writing

- 10 Reasons Why You Should Schedule an Appointment at the UWC

- Scheduling a UWC Appointment with Ease

- Announcements

- Conferences

- Consultant Spotlight

- Creative Writing

- Difficult Conversations

- Graduate Writing

- Intersectionality

- multimodal composing

- Neurodiversity

- Opportunity

- Retrospectives

- Uncategorized

- women's history month

- Writing Center Work

- Writing Strategies

- November 2023

- November 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- September 2021

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.9: Developing a Working Thesis Statement

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58326

- Lumen Learning

Learning Objectives

- Evaluate the role of a working thesis statement

Thesis Angles

Most writers can easily create a topic: squirrels, television viewing, the Patriot Act, Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The more difficult part is creating an angle. But the angle is necessary as a means of creating interest and as a means of indicating the type and organization of the information to follow. Remember that a basic thesis sentence has both a topic and an angle. The topic is what you’re writing about, but the angle covers the main idea of what you’re conveying about that topic. For example, in the following thesis, the topic is exercise, and the angle is that it leads to benefits:

- A regular exercise regime leads to multiple benefits, both physical and emotional.

Click on each of the thesis angles in the box below that you want to learn more about.

So what about this thesis sentence?

- Adult college students have different experiences than traditionally-aged college students.

As a reader, you understand intuitively that the information to come will deal with the different types of experiences that adult college students have. But you don’t quite know if the information will deal only with adults, or if it will compare adults’ experiences with those of typical college students. And you don’t quite know what type of information will come first, second, third, etc.

Realize that a thesis sentence offers a range of possibilities for specificity and organization. As a writer, you may opt to pique reader interest by being very specific or not fully specific in your thesis sentence. The point here is that there’s no one standard way to write a thesis sentence.

Sometimes a writer is more or less specific depending on the reading audience and the effect the writer wants to create. Sometimes a writer puts the angle first and the topic last in the sentence, or sometimes the angle is even implied. You need to gauge your reading audience and you need to understand your own style as a writer. The only basic requirements are that the thesis sentence needs a topic and an angle. The rest is up to you.

This video reviews the importance of thesis statements and provides examples of how good thesis statements can guide your essay.

You can find the transcript for “How to Write a Killer Thesis Statement by Shmoop” here (opens in new window) .

Thesis Creation

At what point do you write a thesis sentence? Of course, this varies from writer to writer and from writing assignment to writing assignment. You’ll usually do some preliminary idea development first, before a thesis idea emerges. And you’ll usually have a working thesis before you do the bulk of your research, or before you fully create the supporting details for your writing.

Think of the thesis as the mid-point of an hourglass.

You develop ideas for writing and prewriting, using various strategies, until a main idea or assertion emerges. This main idea or assertion becomes your point to prove—your working thesis sentence.

Once you have a working thesis sentence with your main idea, you can then develop more support for that idea, but in a more focused way that deepens your thinking about the thesis angle.

Realize that a thesis is really a working thesis until you finalize the writing. As you do more focused research, or develop more focused support, your thesis may change a bit. Just make sure that you retain the basic thesis characteristics of topic and angle.

Thesis Checklist

When you draft a working thesis, it can be helpful to review the guidelines for a strong thesis. The following checklist is a helpful tool you can use to check your thesis once you have it drafted.

Common Problems

Although you have creative control over your thesis sentence, you still should try to avoid the following problems, not for stylistic reasons, but because they indicate a problem in the thinking that underlies the thesis sentence.

Thesis Problems

Thesis too broad.

Hospice workers need support.

The sentence above actually is a thesis sentence; it has a topic (hospice workers) and an angle (need support). But the angle is very broad. When the angle in a thesis sentence is too broad, the writer may not have carefully thought through the specific support for the rest of the writing. A thesis angle that’s too broad makes it easy to fall into the trap of offering information that deviates from that angle.

Thesis too narrow

Hospice workers have a 55% turnover rate compared to the general health care population’s 25% turnover rate.

The above sentence really isn’t a thesis sentence at all, because there’s no angle idea to support. A narrow statistic, or a narrow statement of fact, doesn’t offer the writer’s own ideas or analysis about a topic. A clearer example of a thesis statement with an angle of development would be the following:

The high turnover rate in hospice workers (55 percent) compared to the general health care population (25 percent) indicates a need to develop support systems to reverse this trend.

Where to Place a Thesis?

In the U.S., it’s customary for most academic writers to put the thesis sentence somewhere toward the start of the essay or research paper. The focus here is on offering the main results of your own thinking in your thesis angle and then providing evidence in the writing to support your thinking.

A legal comparison might help to understand thesis placement. If you have seen television shows or movies with courtroom scenes, the lawyer usually starts out by saying, “My client is innocent!” to set the scene, and then provides different types of evidence to support that argument. Academic writing in the U.S. is similar; your thesis sentence provides your main assertion to set the scene of the writing, and then the details and evidence in the rest of the writing support the assertion in the thesis sentence.

NOTE: Although the usual pattern is “thesis sentence toward the start,” there may be reasons to place the thesis elsewhere in the writing. You may decide to place the thesis sentence at the end of the writing if your purpose is to gradually induce a reading audience to understand and accept your assertion. You may decide to place the thesis sentence in the middle of the writing if you think you need to provide relatively complicated background information to your readers before they can understand the assertion in your thesis.

As a writer, you have the option of placing the thesis anywhere in the writing. But, as a writer, you also have the obligation to make the thesis sentence idea clear to your readers. Beginning writers usually stick with “thesis sentence toward the start,” as it makes the thesis prominent in the writing and also reminds them that they need to stick with providing evidence directly related to that thesis sentence’s angle.

Link to Learning

Use this thesis generator from SUNY Empire State College to help you make your thesis statement—just plug in some of the details, and it can help you come up with a solid foundation!

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/20256

Contributors and Attributions

- Parts of a Thesis Sentence. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/thesis-sentence/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- How To Write A Killer Thesis Statement by Shmoop. Authored by : Shmoop. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=6&v=8wxE8R_x5I0&feature=emb_logo . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Module 6: The Writing Process

Developing a working thesis statement, learning objectives.

- Evaluate the role of a working thesis statement

Thesis Angles

Most writers can easily create a topic: squirrels in urban spaces, television viewing and young people, the Patriot Act and democracy, or tragedy in Shakespeare’s Hamlet . The more difficult part is creating an angle, or your major claim about a topic. The angle is necessary for your readers as a means of creating interest and indicating the type and organization of the information to follow. Remember that a basic thesis sentence has both a topic and an angle. The topic is what you’re writing about, but the angle covers the main idea of what you’re conveying about that topic.

For example, in the following thesis, the topic is exercise, and the angle is that it leads to benefits:

- A regular exercise regime leads to multiple physical and emotional benefits.

Hover your cursor over the circles below to read more about thesis angles.

Let’s take a look at a thesis statement.

- College students have experiences.

As a reader, you understand intuitively that the writer will deal with the different types of experiences that adult college students may have. However, you may not know what is significant about this age group and why it matters. How can we be more specific about who we are writing about and what is interesting about the topic? Let’s take a look at a revision that is a bit more specific.

- College students over 30 have different work experiences that benefit their studies.

See the difference? We now have a specific topic (college students over 30) and a specific angle (their work experiences) along with why it matters (their work history will benefit their student skills). Realize that a thesis sentence offers a range of possibilities for specificity and organization. As a writer, you may opt to pique reader interest by being very specific or not fully specific in your thesis sentence. The point here is that there’s no one standard way to write a thesis sentence.

Sometimes a writer is more or less specific depending on the reading audience and the effect the writer wants to create. Sometimes a writer puts the angle first and the topic last in the sentence, or sometimes the angle is even implied. You need to gauge your reading audience and you need to understand your own style as a writer. The only basic requirements are that the thesis sentence needs a topic and an angle. The rest is up to you.

This video reviews the importance of thesis statements and provides examples of how good thesis statements can guide your essay.

You can find the transcript for “How to Write a Killer Thesis Statement by Shmoop” here (opens in new window) .

Thesis Creation

At what point do you write a thesis sentence? Of course, this varies from writer to writer and from writing assignment to writing assignment. You’ll usually do some preliminary idea development first, before a thesis idea emerges. And you’ll usually have a working thesis before you do the bulk of your research, or before you fully create the supporting details for your writing.

Think of the thesis as the mid-point of an hourglass.

You develop ideas for writing and prewriting, using various strategies, until a main idea or assertion emerges. This main idea or assertion becomes your point to prove—your working thesis sentence.

Once you have a working thesis sentence with your main idea, you can then develop more support for that idea, but in a more focused way that deepens your thinking about the thesis angle.

Realize that a thesis is really a working thesis until you finalize the writing. As you do more focused research, or develop more focused support, your thesis may change a bit. Just make sure that you retain the basic thesis characteristics of topic and angle.

Thesis Checklist

When you draft a working thesis, it can be helpful to review the guidelines for a strong thesis. The following checklist is a helpful tool you can use to check your thesis once you have it drafted. Click through these slides to see a sample of a thesis checklist.

Common Problems

Although you have creative control over your thesis sentence, you still should try to avoid the following problems, not for stylistic reasons, but because they indicate a problem in the thinking that underlies the thesis sentence.

Thesis Problems

Thesis too broad.

Hospice workers need more support.

The sentence above actually is a thesis sentence; it has a topic (hospice workers) and an angle (need support). But the angle is too broad. When the angle in a thesis sentence is too broad, the writer needs to add specific support for the topic. A thesis angle that’s too broad may lead to a disorganized paper or you may lose sight of what you are trying to examine as a writer.

Thesis too narrow

Hospice workers at the PeaceHealth Center have a 55% turnover rate compared to the general health care population’s 25% turnover rate.

The above sentence reads like a narrow statistic, or a narrow statement of fact, and does not offer the writer’s own ideas or analysis about a topic. A clearer example of a thesis statement with an angle of development would be the following:

The high turnover rate in hospice workers (55 percent) compared to the general health care population (25 percent) indicates a need to develop support systems to reverse this trend.

This thesis moves us away from one location, and adds an idea on how to “reverse this trend.” The readers will not only learn about the topic, they will also understand the angle of the writer.

Where to Place a Thesis?

For writers in the United States, it is customary for most academic writers to put the thesis sentence somewhere toward the start of the essay or research paper. The focus here is on offering the main results of your own thinking in your thesis angle and then providing evidence in the writing to support your thinking.

A legal comparison might help to understand thesis placement. If you have seen television shows or movies with courtroom scenes, the lawyer usually starts out by saying, “My client is innocent!” to set the scene, and then provides different types of evidence to support that argument. Academic writing in the United States is similar; your thesis sentence provides your main assertion to set the scene of the writing, and then the details and evidence in the rest of the writing support the assertion in the thesis sentence.

As a writer, you have the option of placing the thesis anywhere in the writing. For college assignments, you may be asked to make the thesis sentence idea clear to your readers. College writers usually stick with “thesis sentence toward the start,” as it makes the thesis prominent in the writing.

Link to Learning

Need help understanding thesis statements? Try this thesis generator from SUNY Empire State College to help you make your thesis statement—just plug in some of the details, and it can help you come up with a solid foundation! This is where you can use some of your prewriting or brainstorming to plug in details to create a working thesis statement. This is a great resource you can use in other classes.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Parts of a Thesis Sentence. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/thesis-sentence/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- How To Write A Killer Thesis Statement by Shmoop. Authored by : Shmoop. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=6&v=8wxE8R_x5I0&feature=emb_logo . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- MALS Program

MALS Writing Center

A resource for interdisciplinary writers, photo ©2009 david frazier.

- Arriving at a Working Thesis

Once you have chosen and refined a topic, you will need to form a set of research questions about that topic, and next form a working thesis to answer the research questions. But what exactly is a working thesis? It is a proposed answer to a focused research question, and it is the main point of your argument that you develop throughout your paper. A working thesis is "working" because it guides your research at the same time that your research tweaks it. A working thesis is far enough along to serve as a viable research question-and-answer-pair, but it is still pliable and open to being altered or refined further as your research progresses and as you discover other, related research questions and answers.

Read through the following sections on topic development, and follow the advice given to watch your topic grow and develop into a working thesis (like a research Chia Pet):

The Research Question The Working Thesis The "So What?" Test Lather, Rinse, Repeat

The research question

Your central research question is the driving force of your paper. You are not simply reporting on a topic, such as "treehouses." While such a report might be informative for you or a handful of treehouse novices, it would not produce anything new in the repertoire of treehouse literature, and therefore would simply be repeating information that has already been established.

Instead, you are trying to find out something new relating to that topic (e.g., how does a treehouse contribute to the emotional development of a child?) that will also make a contribution to the scholarly community. In other words, the answer (i.e., your paper) to your central research question needs to matter in your field and to contribute new knowledge to the existing pool. This last part is most important, and you should constantly keep it in the forefront of your mind.

Evaluating the Quality of Your Central Research Question

Your central research question not only needs to be interesting and relevant, but also practical in terms of time and resources available. Ask the following eight questions to evaluate the quality of your research question and the feasibility that you can answer it in the time that you have:

- Does the question deal with a topic or issue that interests me enough to spark my own thoughts and opinions?

- Is the question easily and fully researchable in the time I have to complete the paper?

- What type of information do I need to answer the research question? For example, the research question "What impact has deregulation had on commercial airline safety?" will obviously require certain types of information: + statistics on airline crashes before and after + statistics on other safety problems before and after + information about maintenance practices before and after + information about government safety requirements before and after

- Is the scope of this information reasonable? (e.g., can I really research 30 on-line writing programs developed over a span of 10 years?)

- Given the type and scope of the information that I need, is my question too broad, too narrow, or just right? If you have appropriately narrowed your topic before coming up with a research question, you shouldn't have too much trouble with this one.

- What sources will have the type of information that I need to answer the research question (journals, books, internet resources, government documents, people)?

- Can I access these sources? (e.g., if the bulk of your sources reside in an archive in Newfoundland, you may wish to rethink your question)

- Given my answers to the above questions, do I have a good quality research question that I actually will be able to answer by doing research?

Back to Top

The working thesis - your stand on the research question.

After you come up with a viable research question on your topic, it's time to formulate the working thesis. What does a working thesis say and do?

Defining Features of a Working Thesis

* for most student work, it's a one- or two- sentence statement that explicitly outlines the purpose or point of your paper. A thesis is to a paper what a topic sentence is to a paragraph * it should point toward the development or course of argument the reader can expect your argument to take, but does not have to specifically include 'three supporting points' as you may have once learned * because the rest of the paper will support or back up your thesis, a thesis is normally placed at or near the end of the introductory paragraph. * it is an assertion that a reasonable person could disagree with if you only gave the thesis and no other evidence. It is not a fact or casual observation; it must beg to be proved. And someone should be able to theoretically argue against it (how successfully will depend, of course, on how persuasive you are) * it takes a side on a topic rather than simply announcing that the paper is about a topic (the title should have already told your reader your topic). Don't tell a reader about something; tell them what about something. Answer the questions "how?" or "why?" * it is sufficiently narrow and specific that your supporting points are necessary and sufficient, not arbitrary; paper length and number of supporting points are good guides here * it argues one main point and doesn't squeeze three different theses for three different papers into one sentence

Most importantly, it passes the "So What?" Test...

the "so what?" test