The 1619 Project

75 pages • 2 hours read

The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Preface-Chapter 2

Chapters 3-4

Chapters 5-7

Chapters 8-10

Chapters 11-14

Chapters 15-16

Chapters 17-18

Key Figures

Index of Terms

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

The 1619 Project is a series of essays, poems, and short fiction about the lasting legacy and implications of slavery in the United States. Named after the year the White Lion anchored and sold the first enslaved African people to the English colonies, these essays rethink the United States origin story to explain how a country founded on ideals of freedom preserved the institution of slavery and the lasting legacy of it. Nikole Hannah-Jones , Caitlin Roper, Ilena Silverman, and Jake Silverstein edited the collection.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, the author of the book’s preface and its first and last essays, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and celebrated academic who has won multiple awards for her work, including two George Polk Awards, a Peabody, and three National Magazine Awards. Hannah-Jones is a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine and a professor at Howard University; she reports on and studies racial injustice and the persistence of racial segregation in the United States. In The 1619 Project , Hannah-Jones explains that when she learned about the landing of the White Lion in 1619, she began to understand a history that the popular American narrative erased and ignored. As the 400th anniversary of 1619 loomed nearer, she knew it would go uncelebrated, unacknowledged, and unpacked. Hannah-Jones then pitched her idea to The New York Times Magazine —“a special issue that would mark the four-hundredth anniversary [of 1619] by exploring the unparalleled impact of African slavery on the development of our country and its continuing impact on our society” (xxii).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,350+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,950+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Published in 2021, this book is a hybrid collection of nonfiction, including essays from writers, academics, journalists, and historians exploring 18 different American institutions and phenomena: Democracy, Race, Sugar, Fear, Dispossession, Capitalism, Politics, Citizenship, Self-Defense, Punishment, Inheritance, Medicine, Church, Music, Healthcare, Traffic, Progress, and Justice. The collection also includes poems and short fiction.

Once published, The 1619 Project garnered praise and criticism alike. This book appeared after a year of political upheaval, nationwide protests, and calls for racial justice after the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery—all amid the Covid-19 global pandemic. Some historians challenged and attempted to discredit the arguments presented—especially “the framing, which treated slavery and anti-Blackness as foundational to America” or the “assertion that Black Americans have served as this nation’s most ardent freedom fighters […] or the idea that modern American life has been shaped not by the majestic ideals of our founding, but by its grave hypocrisy” (Hannah-Jones et al. xxv). Congress soon presented legislation to prevent The 1619 Project from being taught in schools and universities. President Trump spoke out against the project, establishing the “1776 Commission” as one of his last acts as President. This sought to discredit the project by “reinforc[ing] the exceptional nature of our country and to put forth a ‘patriotic’ narrative” (Hannah-Jones et al. xxvii).

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

This collection includes racial slurs targeting Black people and other mixed-race populations. The editors, however, have purposefully chosen to use the term “enslaved person” rather than “slave,” as the former “accurately conveys the condition without stripping the individual of his or her humanity” (xiii).

Plot Summary

In August 1619, a year before the Mayflower made land , the White Lion anchored in the harbor at Jamestown. This ship carried enslaved Africans stolen from their country and sold to Englishmen in the American Colonies. This sale was the first of enslaved peoples in Anglo-America and marked the beginning of the institution of American chattel slavery. This text reexamines the founding mythology of America and posits that over and over again, Black Americans have been the actual fighters of freedom. To suggest that our country’s founding happened in 1619 rather than with the Mayflower or the 1776 signing of the Declaration of Independence challenges the ingrained mythology of the United States, which says we are a country built on ideals of freedom and liberty. By contrast, the writers, authors, and scholars in this collection argue that many American establishments derived from the legal institution of slavery with the goal of cementing the status of enslaved people as property.

Perhaps the most radical claim is Hannah-Jones’s contention in “Democracy” that the American Revolution was fought to protect the colonists’ “property”—that is, their claim to an enslaved population—from the British Empire. Not only did slavery provide free labor and serve as property that could be traded, sold, and reproduced, building the wealth of many colonists, but it also provided a way to create a government without an apparent ruling class. Poor white colonists (whose numbers were already limited precisely because the “working class” mostly comprised enslaved people) saw that Black people had no legal rights, and they identified with the wealthier white colonists in power. The colonists built a country off the backs of the enslaved, protecting the institution of slavery through the Constitution, which protected the property rights of enslavers.

Throughout the collection, the authors make it clear that the institution of chattel slavery in the United States was not simply in the background of history but rather at the center. Chapter 2 (“Race”) examines how colonial law “invented” whiteness and Blackness in their current form to safeguard slavery. Chapter 3 (“Sugar”) discusses the pivotal role sugar cultivation played in the development of American chattel slavery. Chapter 4 (“Fear”) documents the fear of Black rebellion that continues to spark white violence. Chapter 5 (“Dispossession”) discusses Indigenous Americans’ relationships to whiteness, Blackness, and slavery. Chapter 6 (“Capitalism”) considers the mutually reinforcing relationship between capitalism and white supremacy. Chapter 7 (“Politics”) explores the racism baked into the US political system.

From here, the book moves on to more specific topics. Chapter 8 (“Citizenship”) recounts Black Americans’ struggles for citizenship. Chapter 9 (“Self-Defense”) questions which US citizens can claim self-defense, especially with regards to gun rights. Chapter 10 (“Punishment”) examines the mass incarceration of Black Americans. Chapter 11 (“Inheritance”) explores the factors that have prevented Black Americans from building intergenerational wealth in the way that white Americans have. Chapter 12 (“Medicine”) discusses systemic racism within the US medical system and its implications for Black Americans’ health. Chapter 13 (“Church”) considers the role religion has played in Black freedom struggles. Chapter 14 (“Music”) traces traditionally Black musical genres back to their origins and discusses their complex relationship to race and racism. Chapter 15 (“Healthcare”) situates the contemporary debate about healthcare in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and the plight of newly “free” Black Americans. Chapter 16 (“Traffic”) explores how seemingly benign infrastructure reflects the legacy of slavery and segregation. Chapter 17 (“Progress”) argues that the idea of progress can act as an impediment to real-world progress. Finally, in Chapter 18 (“Justice”), Hannah-Jones returns to summarize the project’s implications with an eye towards building a more equitable future.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Featured Collections

Black History Month Reads

View Collection

Books on U.S. History

Contemporary Books on Social Justice

Nation & Nationalism

New York Times Best Sellers

Politics & Government

Safety & Danger

The Best of "Best Book" Lists

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

Nikole Hannah-Jones’ essay from ‘The 1619 Project’ wins commentary Pulitzer

Of all the thousands upon thousands of stories and projects produced by American media last year, perhaps the one most-talked about was The New York Times Magazine’s ambitious “The 1619 Project,” which recognized the 400th anniversary of the moment enslaved Africans were first brought to what would become the United States and how it forever changed the country.

It was a phenomenal piece of journalism.

And while the project in its entirety did not make the list of Pulitzer Prize finalists, the introductory essay by Nikole Hannah-Jones , the creator of the landmark project, was honored with a prestigious Pulitzer Prize for commentary.

After the announcement that she has been awarded the Pulitzer Prize, Hannah-Jones told the Times’ staff it was “the most important work of my life.”

While nearly impossible, and almost insulting, to try and describe in a handful of words or even sentences, Hannah-Jones’ essay was introduced with this headline: “Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True.”

In her essay, Hannah-Jones wrote, “But it would be historically inaccurate to reduce the contributions of black people to the vast material wealth created by our bondage. Black Americans have also been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom. More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: It is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy.”

RELATED TRAINING: Make Diversity a Priority During the Pandemic

Hannah-Jones’ and “The 1619 Project,” however, were not without controversy. There was criticism of the project, particularly from conservatives. Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich called it “propaganda.” A commentator for The Federalist tweeted the goal of the project was to “delegitimize America, and further divide and demoralize its citizenry.”

But the most noteworthy criticism came from a group of five historians. ln a letter to the Times , they wrote that they were “dismayed at some of the factual errors in the project and the closed process behind it.” They added, “These errors, which concern major events, cannot be described as interpretation or ‘framing.’ They are matters of verifiable fact, which are the foundation of both honest scholarship and honest journalism. They suggest a displacement of historical understanding by ideology.”

Wall Street Journal assistant editorial features editor Elliot Kaufman wrote a column with the subhead: “The New York Times tries to rewrite U.S. history, but its falsehoods are exposed by surprising sources.”

In a rare move, the Times responded to the criticism with its own response . New York Times Magazine editor-in-chief Jake Silverstein wrote, “Though we respect the work of the signatories, appreciate that they are motivated by scholarly concern and applaud the efforts they have made in their own writings to illuminate the nation’s past, we disagree with their claim that our project contains significant factual errors and is driven by ideology rather than historical understanding. While we welcome criticism, we don’t believe that the request for corrections to The 1619 Project is warranted.”

That was just a portion of the rather lengthy and stern, but respectful response defending the project.

RELATED TRAINING: Covering Hate and Extremism, From the Fringes to the Mainstream

In the end, the 1619 Project — and Hannah-Jones’ essay, in particular — will be remembered for one of the most impactful and thought-provoking pieces on race, slavery and its impact on America that we’ve ever seen.

And maybe there was another reason for the pushback besides those questioning its historical accuracy.

As The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer wrote in December , “U.S. history is often taught and popularly understood through the eyes of its great men, who are seen as either heroic or tragic figures in a global struggle for human freedom. The 1619 Project, named for the date of the first arrival of Africans on American soil, sought to place ‘the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.’ Viewed from the perspective of those historically denied the rights enumerated in America’s founding documents, the story of the country’s great men necessarily looks very different.”

There’s no question that Hannah-Jones’ essay, which requires the kind of smart thinking and discussion that this country needs to continue having, deserved to be recognized with a Pulitzer as the top commentary of 2019. After all, and this is not hyperbole, it’s one of the most important essays ever.

In addition, we should acknowledge the other two finalists in this category: Washington Post sports columnist Sally Jenkins and Los Angeles Times columnist Steve Lopez.

RELATED TRAINING: Writing with Voice and Structure, with Lane DeGregory

Jenkins continues to be among the best sports columnists in the country. Meanwhile, has any writer done more to shine a light on homelessness than Lopez? This is the third time in the past four years (and fourth time overall) that Lopez has been a finalist in the commentary category.

In any other year, both would be deserving of Pulitzer Prizes. But 2019 will be remembered for Nikole Hannah-Jones’ powerful essay and project.

More Pulitzer coverage from Poynter

- With most newsrooms closed, Pulitzer Prize celebrations were a little different this year

- Here are the winners of the 2020 Pulitzer Prizes

- Here are the 2020 Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoons

- Pulitzers honor Ida B. Wells, an early pioneer of investigative journalism and civil rights icon

- Reporting about climate change was a winner in this year’s Pulitzers

- ‘Lawless,’ an expose of villages without police protection, wins Anchorage Daily News its third Public Service Pulitzer

- The iconic ‘This American Life’ won the first-ever ‘Audio Reporting’ Pulitzer

- The Washington Post won a Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting for a novel climate change story

Associated Press Stylebook makes Merriam-Webster its official dictionary

If a term isn’t listed in the stylebook, its entry in Merriam-Webster will be considered AP style.

Opinion | What’s going on with the NFL Network?

The NFL appears to be sabotaging ‘Good Morning Football,’ one of the best sports studio shows on TV. Why?

Are you an early-career reporter looking to level up? We’re here to help.

Pulitzer Prize winner Kat McGrory is one of the instructors in Poynter's upcoming Reporter's Toolkit training program

No, crime has not ‘skyrocketed’ under Joe Biden, as Rep. Nancy Mace claimed

Overall violent crime and homicides are down during Biden’s presidency. Some property crimes are also down, though motor vehicle theft notably rose

Opinion | What’s next for Disney and CEO Bob Iger after a record-breakingly expensive corporate proxy fight?

Iger’s current contract runs through 2026. Then what?

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Irish Literature › Analysis of W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916

Analysis of W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on March 14, 2021 • ( 0 )

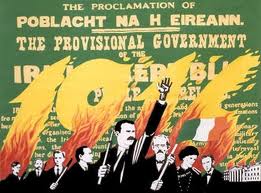

The Easter Rising of 1916 catalyzed the final phase of the Irish struggle for independence and forced Yeats to recant the stinging assessment of “September 1913” that “Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone, / It’s with O’Leary in the grave.” In the wake of the Easter Rising, Yeats decided that “September 1913” had come to sound “old-fashioned” ( VP 820). “Easter 1916” is dated September 25, 1916, but a May 11 letter to Lady Gregory, written 18 days after the rising began, contains its germ: “I am trying to write a poem on the men executed—‘terrible beauty has been born again’” ( Letters 613). Yeats writes in the same letter, “I had no idea that any public event could so deeply move me,” and yet he remained ambivalent about the rising, as reflected in “Easter 1916,” his principal public statement on the event. The poem’s famous refrain may have been inspired by Maud Gonne’s remark in a May letter that the rebels “have raised the Irish cause again to a position of tragic dignity” ( GY 372). Writing to Lady Gregory on May 11, Yeats credits Gonne with the comment that “tragic dignity has returned to Ireland” (613), which artistically elevates Gonne’s actual comment and anticipates the language of his refrain.

The poem’s opening lines—lines of “nerveless syntax onto which the great refrain will drop its iron portcullis,” as Hugh Kenner puts it—have a penitential honesty ( Colder Eye 228). Yeats confesses to just the kind of mockery he disparages in section five of “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen.” He recalls occasionally bumping into the future martyrs of the rising as they came from “counter or desk” at the end of the workday. Even as he exchanged “polite meaningless words”—a phrase twice repeated, indicating the innocuous interchangeability of these encounters—Yeats nursed a “mocking tale or a gibe” to recount around the fire at his club. He may refer to the Arts Club, Upper Merrion Street, Dublin, a venue for dinner and discussion that was not, in Joseph Hone’s estimate, “bookish or particularly intellectual” (W. B. Yeats 233–234; for Yeats at the Arts Club see I&R, I, 51–53). He may alternatively refer to the Stephen’s Green Club ( New Biography 215). The reference to “counter or desk” associates the prospective martyrs with the till-keeping middle class (the “nationalist petite bourgeoisie” in R. F. Foster’s phrase) that Yeats had excoriated in “September 1913” and “Paudeen”: hence his condescension ( AP 59). Their emergence from “eighteenth-century houses” and their “vivid faces,” however, hint at an unguessed spiritual continuity with the generation of Robert Emmet (1778–1803), Edward Fitzgerald (1763–98), and Wolfe Tone (1763–98). Yeats had been convinced that Dublin was a place “where motley is worn,” but the rising exposed the magnitude of his misunderstanding: “All changed, changed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born.”

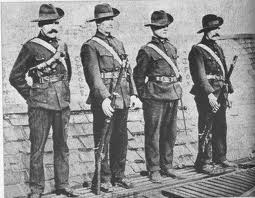

British soldiers at a barricade in Dublin during the Easter Rising. Bettmann / Getty Images

The second stanza namelessly alludes to the leaders of the rising whom Yeats best knew, emphasizing the commonplace humanity out of which, by some miraculous alchemy, came the “terrible beauty” of the poem’s refrain. As Kenner writes, Yeats “silhouettes anonymities, ‘this woman,’ ‘this man,’ ‘this other’ in part 2, against the sunburst of part 4, where names start forth and the poet-mage takes charge” ( Colder Eye 229). The roster of the anonymous includes Constance Markiewicz (1868– 1927) whose fall from youthful feminine grace into the shrillness of politics is recounted in “In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz” and “On a Political Prisoner.” She was condemned to death for her part in the rising but her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and she was released from jail in 1917. There is Patrick Pearse (1879–1916), who founded the St. Enda’s School for Boys in Dublin and proclaimed the birth of the Irish Republic from the steps of the General Post Office. Pearse rode “our wingèd horse”—Pegasus—in the sense that he couched the struggle for Irish independence in mythic and romantic terms. In a letter of May 1, 1916, to his sister Lolly, Yeats called Pearse a “man made dangerous by the Vertigo of Self Sacrifice,” while Ezra Pound reported to John Quinn Yeats’s opinion that Pearse was “half-cracked” and suffering from “Emmet mania, same as some other lunatics think they are Napoleon or God” and that Pearse “wouldn’t be happy until he was hanged” (AP 46). There is Thomas MacDonagh (1878–1916), a poet and playwright whom Yeats described in his 1909 diary as a “man with some literary faculty which will probably come to nothing through lack of culture and encouragement.” He continues in terms that anticipate the critique of “Easter 1916”: “In England this man would have become remarkable in some way, here he is being crushed by the mechanical logic and commonplace eloquence which give power to the most empty mind, because, being ‘something other than human life’, they have no use for distinguished feeling or individual thought. I mean that within his own mind this mechanical thought is crushing as with an iron roller all that is organic” ( Autobiographies . 360; Memoirs . 177–178; see also The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats 760, 782– 784). Finally there is John MacBride (1865–1916), Maud Gonne’s estranged husband. Though a “drunken vainglorious lout,” MacBride is likewise “transformed utterly,” a generous acknowledgment considering Yeats’s hostility to the bluff military man who had bested him briefly but decisively in Gonne’s affections. Pearse, MacDonagh, and MacBride were among 15 leaders of the rising executed by the British: Pearse and MacDonagh were shot on May 3, MacBride on May 5.

In its third stanza, “Easter 1916” contrasts the stoniness of hearts “with one purpose alone”—the stoniness of the single-minded political fanatic— with the “living stream”: the supple, changing beauty of nature, the subtle shadings that make for poetry. More than this, such hearts “trouble” the living stream, which is to say, awaken the kind of inhuman destructive zeal exemplified by the Easter Rising. As R. F. Foster observes, these lines are implicitly addressed to Gonne and reiterate the plea, mooted six years earlier in the essay “J. M. Synge and the Ireland of his Time,” against “the morbid persistence of minds unsettled by some fixed idea” and all that “kills intellectual innocence; that delight in what is unforeseen, and in the mere spectacle of the world, the mere drifting hither and thither that must come before all true thought and emotion,” against all that turns the “mind to stone” ( W. B. Yeats: A Life, II: The ArchPoet 61–62; Essays and Introductions 313–314). Yeats worked on the poem while staying at Les Mouettes, the Gonnes’ home in Colleville-sur-Mer, on the Normandy shore, during the summer of 1916, and he unsuccessfully proposed to Gonne on July 1 (YC 186). In September 1916, Yeats read her the poem and implored her, in terms that echo his poem, “to forget the stone and its inner fire for the flashing, changing joy of life” (AP 62; Scattering Branches 32). This was a political and spiritual plea, but also a romantic plea, as Yeats knew he could succeed in his suit only by reconciling Gonne to the apolitical “flashing, changing joy of life.”

In the final stanza, Yeats comes to the central spiritual and philosophical question of the poem. Is the sacrifice of the living heart ever justified? Or rather, as John O’Leary held, are there “things which a man should not do, perhaps even to save a nation” ( Aut. 101, 178; E&I 247; Uncollected Prose by W. B. Yeats. Vol. 2 36). As in “On being asked for a War Poem,” Yeats skirts the controversy of an answer by invoking the proper bounds of the poet’s role, declaring it his part merely to “murmur name upon name, / As a mother names her child / When sleep at last has come / On limbs that had run wild.” Yeats toys with the further metaphorization of death as nightfall, but not liking the romantic varnish of this—perhaps resisting something of the romantic varnish that had quickly come to surround the rising and especially its martyrs—Yeats reverts to the unvarnished reality of “death” and the matter-offact possibility that, after all, England might have kept its pledge to grant Ireland home rule as soon as the world war had come to an end. “And what if excess of love”—for Ireland—“Bewildered them till they died?” Yeats asks, but again retreats from the critical implication of his own question, and ends with a solemn martyrology that comported with popular sentiment. MacDonagh, MacBride, Pearse, and James Connolly (1870–1916) will be forever remembered wherever the green of Ireland is worn. The transition from motley to green epitomizes the poem’s refrain: “All changed, changed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born.”

Predictably, “Easter 1916” elicited a sharp rebuke from Gonne. “No I don’t like your poem,” she wrote on November 8, 1916, “it isn’t worthy of you & above all it isn’t worthy of the subject— Though it reflects your present state of mind perhaps, it isn’t quite sincere enough for you who have studied philosophy & know something of history know quite well that sacrifice has never yet turned a heart to stone though it has immortalised many & through it alone mankind can rise to God. You recognise this in the line which was the original inspiration of your poem ‘A terrible Beauty is born’ but you let your present mood mar & confuse it till even some of the verses become unintelligible to many.” Gonne also rejected the imputation that MacDonagh, Pearse, Connolly were “sterile fixed minds,” insisting that “each served Ireland, which was their share of the world, the part they were in contact with, with varied faculties and vivid energy! those three were men of genius, with large comprehensive & speculative & active brains [. . .]. As for my husband he has entered Eternity by the great door of sacrifice which Christ opened & has therefore atoned for all [. . .].” She allows that the poem contains beautiful language but finds that it fails to be a “living thing which our race would treasure & repeat, such as a poet like you might have given to your nation & which would have avenged our material failure by its spiritual beauty” (GY 384– 385). Harold Bloom perspicuously observes that the poem is highly uncharacteristic, as the visionary element (“A terrible beauty is born”) is “not the strength of the poem, which excels in sober coloring of accurate moral description, a quality normally lacking in Yeats. Easter 1916 is a model of sanity and proportion, and is genuinely Yeats’s eighteenth-century poem [. . .]” (Yeats 314).

Bibliography Bloom, Harold. Yeats; Foster, R. F. W. B. Yeats: A Life, II: The Arch-Poet; Gwynn, Stephen, ed. Scattering Branches: Tributes to the Memory of W. B. Yeats; Hone, Joseph. W. B. Yeats; Jeffares, A. Norman. W. B. Yeats: A New Biography; Kelly, John S. A W. B. Yeats Chronology; Kenner, Hugh. A Colder Eye: The Modern Irish Writers; Mikhail, E. H., ed. Yeats: Interviews and Recollections (vol. 1); W. B. Yeats, Autobiographies, The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats (vol. 4), Essays and Introductions, The GonneYeats Letters 1893–1938, The Letters of W. B. Yeats, Memoirs, Uncollected Prose by W. B. Yeats (vol. 2), The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats.

Share this:

Categories: Irish Literature , Literature

Tags: Analysis of W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 , Easter 1916 , Irish Revolution , Literary Criticism , Modernism , Poetry , The Easter Rising of 1916 , W. B. Yeats , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 analysis , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 as a love poem , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 criticism , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 essays , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 notes , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 structure , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 summary , W. B. Yeats’s Easter 1916 themes

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Trans-national America

As World War I unfolded in Europe, intensifying ethnic antagonisms, native-born Americans became increasingly suspicious of the pockets of immigrant culture thriving among them. In 1916, critic and essayist Randolph Bourne challenged such attitudes with an essay—now considered a classic of forward thinking—calling for a new, more cosmopolitan conception of America and a reconsideration of the “melting-pot” theory.

No reverberatory effect of the great war has caused American public opinion more solicitude than the failure of the ‘melting-pot.’ The discovery of diverse nationalistic feelings among our great alien population has come to most people as an intense shock. It has brought out the unpleasant inconsistencies of our traditional beliefs We have had to watch hard-hearted old Brahmins virtuously indignant at the spectacle of the immigrant refusing to be melted, while they jeer at patriots like Mary Antin who write about ‘our forefathers.’ We have had to listen to publicists who express themselves as stunned by the evidence of vigorous nationalistic and cultural movements in this country among Germans, Scandinavians, Bohemians, and Poles, while in the same breath they insist that the mien shall be forcibly assimilated to that Anglo-Saxon tradition which they unquestioningly label ‘American.’

As the unpleasant truth has come upon us that assimilation in this country was proceeding on lines very different from those we had marked out for it, we found ourselves inclined to blame those who were thwarting our prophecies. The truth became culpable. We blamed the war, we blamed the Germans. And then we discovered with a moral shock that these movements had been making great headway before the war even began. We found that the tendency, reprehensible and paradoxical as it might be, has been for the national clusters of immigrants, as they became more and more firmly established and more and more prosperous, to cultivate more and more assiduously the literatures and cultural traditions of their homelands. Assimilation, in other words, instead of washing out the memories of Europe, made them more and more intensely real. Just as these clusters became more and more objectively American, did they become more and more German or Scandinavian or Bohemian or Polish.

To face the fact that our aliens are already strong enough to take a share in the direction of their own destiny, and that the strong cultural movements represented by the foreign press, schools, and colonies are a challenge to our facile attempts, is not, however, to admit the failure of Americanization. It is not to fear the failure of democracy. It is rather to urge us to an investigation of what Americanism may rightly mean. It is to ask ourselves whether our ideal has been broad or narrow—whether perhaps the time has not come to assert a higher ideal than the ‘melting-pot.’ Surely we cannot be certain of our spiritual democracy when, claiming to melt the nations within us to a comprehension of our free and democratic institutions, we fly into panic at the first sign of their own will and tendency. We act as if we wanted Americanization to take place only on our own terms, and not by the consent of the governed. All our elaborate machinery of settlement and school and union, of social and political naturalization, however, will move with friction just in so far as it neglects to take into account this strong and virile insistence that America shall be what the immigrant will have a hand in making it, and not what a ruling class, descendant of those British stocks which were the first permanent immigrants, decide that America shall be made. This is the condition which confronts us, and which demands a clear and general readjustment of our attitude and our ideal.

Mary Antin is right when she looks upon our foreign-born as the people who missed the Mayflower and came over on the first boat they could find. But she forgets that when they did come it was not upon other Mayflower but upon a ‘Fleur,’ a ‘Fleur de Mai,’ a ‘Fleur di Maggio,’ a ‘Majblomst.’ These people were not mere arrivals from the same family, to be welcomed as understood and long-loved but strangers to the neighborhood, with whom a long process of settling down had to take place. For they brought with them their national and racial characters, and each new national quota had to wear slowly away the contempt with which its mere alienness got itself greeted. Each had to make its way slowly from the lowest strata of unskilled labor up to a level where it satisfied the accredited norms of social success.

We are all foreign-born or the descendants of foreign-born, and if distinctions are to be made between us, they should rightly be on some other ground than indigenousness. The early colonists came over with motives no less colonial than the later. They did not come to be assimilated in an American melting pot. They did not come to adopt the culture of the American Indian. They had not the smallest intention of ‘giving themselves without reservation’ to the new country. They came to get freedom to live as they wanted to. They came to escape from the stifling air and chaos of the old world; they came to make their fortune in a new land. They invented no new social framework. Rather they brought over bodily the old ways to which they had been accustomed. Tightly concentrated on a hostile frontier, they were conservative beyond belief. Their pioneer daring was reserved for the objective conquest of material resources. In their folkways, in their social and political institutions, they were, like every colonial people, slavishly imitative of the mother country. So that, in spite of the ‘Revolution,’ our whole legal and political system remained more English than the English, petrified and unchanging, while in England law developed to meet the needs of the changing times.

It is just this English-Americanconservatism that has been our chief obstacle to social advance. We have needed the new peoples—the order of the German and Scandinavian, the turbulence of the Slav and Hun—to save us from our own stagnation. I do not mean that the illiterate Slav is now the equal of the New Englander of pure descent. He is raw material to be educated, not into a New Englander, but into a socialized American along such lines as those thirty nationalities are being educated in the amazing school of Gary. I do not believe that this process is to be one of decades of evolution. The spectacle of Japan’s sudden jump from medievalism to post-modernism should have destroyed the superstition. We are not dealing with individuals who are to ‘evolve.’ We are dealing with their children, who with that education we are about to have, will start level with all of us. Let us cease to think of ideals like democracy as magical qualities inherent in certain peoples. Let us speak, not of inferior races, but of inferior civilizations. We are all to educate and to be educated. These peoples in America are in a common enterprise. It is not what we are now that concerns us, but what this plastic next generation may become in the light of a new cosmopolitan ideal.

We are not dealing with static factors, but with fluid and dynamic generations. To contrast the older and the newer immigrants and see the one class as democratically motivated by love of liberty, and the other by mere money-getting, is not to illuminate the future. To think of earlier nationalities as culturally assimilated to America, while we picture the later as a sodden and resistive mass, makes only for bitterness and misunderstanding. There may be a difference between these earlier and these later stocks, but it lies neither in motive for coming nor in strength of cultural allegiance to the homeland. The truth is that no more tenacious cultural allegiance to the mother country has been shown by any alien nation than by the ruling class of Anglo-Saxon descendants in these American States. English snobberies, English religion, English literary styles, English literary reverences and canons, English ethics, English superiorities, have been the cultural food that we have drunk in from our mothers’ breasts. The distinctively American spirit—pioneer, as distinguished from the reminiscently English—that appears in Whitman and Emerson and James, has had to exist on sufferance alongside of this other cult, unconsciously belittled by our cultural makers of opinion. No country has perhaps had so great indigenous genius which had so little influence on the country’s traditions and expressions. The unpopular and dreaded German-American of the present day is a beginning amateur in comparison with those foolish Anglophiles of Boston and New York and Philadelphia whose reversion to cultural type sees uncritically in England’s cause the cause of Civilization, and, under the guise of ethical indepenence of thought, carries along European traditions which are no more ‘American’ than the German categories themselves.

It speaks well for German-American innocence of heart or else for its lack of imagination that it has not turned the hyphen stigma into a ‘Tu quoque!’ If there were to be any hyphens scattered about, clearly they should be affixed to those English descendants who had had centuries of time to be made American where the German had had only half a century. Most significantly has the war brought out of them this alien virus, showing them still loving English things, owing allegiance to the English Kultur, moved by English shibboleths and prejudice. It is only because it has been the ruling class in this country that bestowed the epithet that we have not heard copiously and scornfully of ‘hyphenated English Americans.’ But even our quarrels with England have had the bad temper, the extravagance, of family quarrels. The Englishman of to-day nags us and dislikes us in that personal, peculiarly intimate way in which he dislikes the Australian, or as we may dislike our younger brothers. He still thinks of us incorrigibly as ‘colonials.’ America—official, controlling, literary, political America—is still, as a writer recently expressed it, ‘culturally speaking, a self-governing dominion of the British Empire.’

The non-English American can scarcely be blamed if he sometimes thinks of the Anglo-Saxon predominance in America as little more than a predominance of priority. The Anglo-Saxon was merely the first immigrant, the first to found a colony. He has never really ceased to be the descendant of immigrants, nor has he ever succeeded in transforming that colony into a real nation, with a tenacious, richly woven frabric of native culture. Colonials from the other nations have come and settled down beside him. They found no definite native culture which should startle them out of their colonialism, and consequently they looked back to their mother-country, as the earlier Anglo-Saxon immigrant was looking back to his. What has been offered the newcomer has been the chance to learn English, to become a citizen, to salute the flag. And those elements of our ruling classes who are responsible for the public schools, the settlements, all the organizations for amelioration in the cities, have every reason to be proud of the care and labor which they ve devoted to absorbing the immigrant. His opportunities the immigrant has taken to gladly, with almost pathetic eagerness to make his way in the new land without friction or disturbance. The common language has made not only for the necessary communication, but for all the amenities of life.

If freedom means the right to do pretty much as one pleases, so long as one does not interfere with others, the immigrant has found freedom, and the ruling element has been singularly liberal in its treatment of the invading hordes. But if freedom means a democratic cooperation in determining the ideals and purposes and industrial and social institutions of a country, then the immigrant has not been free, and Anglo-Saxon element is guilty of just what every dominant race is guilty of in every European country: the imposition of its own culture upon the minority peoples. The fact that this imposition has been so mild and, indeed, semi-conscious does not alter its quality. And the war has brought out just the degree to which that purpose of ‘Americanizing,’ that is, ‘Anglo-Saxonizing,’ the immigrant has failed.

For the Anglo-Saxon now in his bitterness to turn upon the other peoples, talk about their ‘arrogance,’ scold them for not being melted in a pot which never existed, is to betray the unconscious purpose which lay at the bottom of his heart. It betrays too the possession of a racial jealousy similar to that of which he is now accusing the so called ‘hyphenates.’ Let the Anglo Saxon be proud enough of the heroic toil and heroic sacrifices which moulded the nation. But let him ask himself, if he had had to depend on the English descendants, where he would have been living to-day. To those of us who see in the exploitation of unskilled labor the strident red leit-motif of our civilization, the settling of the country presents a great social drama as the waves of immigration broke over it.

Let the Anglo-Saxon ask himself where he would have been if these races had not come? Let those who feel the inferiority of the non-Anglo-Saxon immigrant contemplate that region of the States which has remained the most distinctively ‘American,’ the South. Let him ask himself whether he would really like to see the foreign hordes Americanized into such an Americanization. Let him ask himself how superior this native civilization is to the great ‘alien’ states of Wisconsin and Minnesota, where Scandinavians, Poles, and Germans have self-consciously labored to preserve their traditional culture, while being outwardly and satisfactorily American. Let him ask himself how much more wisdom, intelligence, industry and social leadership has come out of these alien states than out of all the truly American ones. The South, in fact, while this vast Northern development has gone on, still remains an English colony, stagnant and complacent, having progressed culturally scarcely beyond the early Victorian era. It is culturally sterile because it has had no advantage of cross-fertilization like the Northern states. What has happened in states such as Wisconsin and Minnesota is that strong foreign cultures have struck root in a new and fertile soil. America has meant liberation, and German and Scandinavian political ideas and social energies have expanded to a new potency. The process has not been at all the fancied ‘assimilation’ of the Scandinavian or Teuton. Rather has it been a process of their assimilation of us—I speak as an Anglo-Saxon. The foreign cultures have not been melted down or run together, made into some homogeneous Americanism, but have remained distinct but cooperating to the greater glory and benefit not only of themselves but of all the native ‘Americanism’ around them.

What we emphatically do not want is that these distinctive qualities should be washed out into a tasteless, colorless fluid of uniformity. Already we have far too much of this insipidity,—masses of people who are cultural half-breeds, neither assimilated Anglo-Saxons nor nationals of another culture. Each national colony in this country seems to retain in its foreign press, its vernacular literature, its schools, its intellectual and patriotic leaders, a central cultural nucleus. From this nucleus the colony extends out by imperceptible gradations to a fringe where national characteristics are all but lost. Our cities are filled with these half-breeds who retain their foreign names but have lost the foreign savor. This does not mean that they have actually been changed into New Englanders or MiddleWesterners. It does not mean that they have been really Americanized. It means that, letting slip from them whatever native culture they had, they have substituted for it only the most rudimentary American—the American culture of the cheap newspaper, the ‘movies,’ the popular song, the ubiquitous automobile. The unthinking who survey this class call them assimilated, Americanized. The great American public school has done its work. With these people our institutions are safe. We may thrill with dread at the aggressive hyphenate, but this tame flabbiness is accepted as Americanization. The same moulders of opinion whose ideal is to melt the different races into Anglo-Saxon gold hail this poor product as the satisfying result of their alchemy.

Yet a truer cultural sense would have told us that it is not the self-conscious cultural nuclei that sap at our American life, but these fringes. It is not the Jew who sticks proudly to the faith of his fathers and boasts of that venerable culture of his who is dangerous to America, but the Jew who has lost the Jewish fire and become a mere elementary, grasping animal. It is not the Bohemian who supports the Bohemian schools in Chicago whose influence is sinister, but the Bohemian who has made money and has got into ward politics. Just so surely as we tend to disintegrate these nuclei of nationalistic culture do we tend to create hordes of men and women without a spiritual country, cultural outlaws, without taste, without standards but those of the mob. We sentence them to live on the most rudimentary planes of American life. The influences at the centre of the nuclei are centripetal. They make for the intelligence and the social values which mean an enhancement of life. And just because the foreign-born retains this expressiveness is he likely to be a better citizen of the American community. The influences at the fringe, however, are centrifugal, anarchical. They make for detached fragments of peoples. Those who came to find liberty achieve only license. They become the flotsam and jetsam of American life, the downward undertow of our civilization with its leering cheapness and falseness of taste and spiritual outlook, the absence of mind and sincere feeling which we see in our slovenly towns, our vapid moving pictures, our popular novels, and in the vacuous faces of the crowds on the city street. This is the cultural wreckage of our time, and it is from the fringes of the Anglo-Saxon as well as the other stocks that it falls. America has as yet no impelling integrating force. It makes too easily for this detritus of cultures. In our loose, free country, no constraining national purpose, no tenacious folk-tradition and folk-style hold the people to a line.

The war has shown us that not in any magical formula will this purpose be found. No intense nationalism of the European plan can be ours. But do we not begin to see a new and more adventurous ideal? Do we not see how the national colonies in America, deriving power from the deep cultural heart of Europe and yet living here in mutual toleration, freed from the age-long tangles of races, creeds, and dynasties, may work out a federated ideal? America is transplanted Europe, but a Europe that has not been disintegrated and scattered in the transplanting as in some Dispersion. Its colonies live here inextricably mingled, yet not homogeneous. They merge but they do not fuse.

America is a unique sociological fabric, and it bespeaks poverty of imagination not to be thrilled at the incalculable potentialities of so novel a union of men. To seek no other goal than the weary old nationalism,—belligerent, exclusive, inbreeding, the poison of which we are witnessing now in Europe,—is to make patriotism a hollow sham, and to declare that, in spite of our boastings, America must ever be a follower and not a leader of nations.

If we come to find this point of view plausible, we shall have to give up the search for our native ‘American’ culture. With the exception of the South and that New England which, like the Red Indian, seems to be passing into solemn oblivion, there is no distinctively American culture. It is apparently our lot rather to be a federation of cultures. This we have been for half a century, and the war has made it ever more evident that this is what we are destined to remain. This will not mean, however, that there are not expressions of indigenous genius that could not have sprung from any other soil. Music, poetry, philosophy, have been singularly fertile and new. Strangely enough, American genius has flared forth just in those directions which are least understanded of the people. If the American note is bigness, action, the objective as contrasted with the reflective life, where is the epic expression of this spirit? Our drama and our fiction, the peculiar fields for the expression of action and objectivity, are somehow exactly the fields of the spirit which remain poor and mediocre. American materialism is in some way inhibited from getting into impressive artistic form its own energy with which it bursts. Nor is it any better in architecture, the least romantic and subjective of all the arts. We are inarticulate of the very values which we profess to idealize. But in the finer forms—music, verse, the essay, philosophy—the American genius puts forth work equal to any of its contemporaries. Just in so far as our American genius has expressed the pioneer spirit, the adventurous, forward-looking drive of a colonial empire, is it representative of that whole America of the many races and peoples, and not of any partial or traditional enthusiasm. And only as that pioneer note is sounded can we really speak of the American culture. As long as we thought of Americanism in terms of the ‘melting-pot,’ our American cultural tradition lay in the past. It was something to which the new Americans were to be moulded. In the light of our changing ideal of Americanism, we must perpetrate the paradox that our American cultural tradition lies in the future. It will be what we all together make out of this incomparable opportunity of attacking the future with a new key.

Whatever American nationalism turns out to be, it is certain to become something utterly different from the nationalisms of twentieth-century Europe. This wave of reactionary enthusiasm to play the orthodox nationalistic game which is passing over the country is scarcely vital enough to last. We cannot swagger and thrill to the same national self-feeling. We must give new edges to our pride. We must be content to avoid the unnumbered woes that national patriotism has brought in Europe, and that fiercely heightened pride and self-consciousness. Alluring as this is, we must allow our imaginations to transcend this scarcely veiled belligerency. We can be serenely too proud to fight if our pride embraces the creative forces of civilization which armed contest nullifies. We can be too proud to fight if our code of honor transcends that of the schoolboy on the playground surrounded by his jeering mates. Our honor must be positive and creative, and not the mere jealous and negative protectiveness against metaphysical violations of our technical rights. When the doctrine is put forth that in one American flows the mystic blood of all our country’s sacred honor, freedom, and prosperity, so that an injury to him is to be the signal for turning our whole nation into that clan-feud of horror and reprisal which would be war, then we find ourselves back among the musty schoolmen of the Middle Ages, and not in any pragmatic and realistic America of the twentieth century.

We should hold our gaze to what America has done, not what medieval codes of dueling she has failed to observe. We have transplanted European modernity to our soil, without the spirit that inflames it and turns all its energy into mutual destruction. Out of these foreign peoples there has somehow been squeezed the poison. An America, ‘hyphenated’ to bitterness, is somehow non-explosive. For, even if we all hark back in sympathy to a European nation, even if the war has set every one vibrating to some emotional string twanged on the other side of the Atlantic, the effect has been one of almost dramatic harmlessness.

What we have really been witnessing, however unappreciatively, in this country has been a thrilling and bloodless battle of Kulturs. In that arena of friction which has been the most dramatic—between the hyphenated German-American and the hyphenated English-American—there have emerged rivalries of philosophies which show up deep traditional attitudes, points of view which accurately reflect the gigantic issues of the war. America has mirrored the spiritual issues. The vicarious struggle has been played out peacefully here in the mind. We have seen the stout resistiveness of the old moral interpretation of history on which Victorian England thrived and made itself great in its own esteem. The clean and immensely satisfying vision of the war as a contest between right and wrong; the enthusiastic support of the Allies as the incarnation of virtue-on-a-rampage; the fierce envisaging of their selfish national purposes as the ideals of justice, freedom and democracy—all this has been thrown with intensest force against the German realistic interpretations in terms of the struggle for power and the virility of the integrated State. America has been the intellectual battleground of the nations.

The failure of the melting-pot, far from closing the great American democratic experiment, means that it has only just begun. Whatever American nationalism turns out to be, we see already that it will have a color richer and more exciting than our ideal has hitherto encompassed. In a world which has dreamed of internationalism, we find that we have all unawares been building up the first international nation. The voices which have cried for a tight and jealous nationalism of the European pattern are failing. From that ideal, however valiantly and disinterestedly it has been set for us, time and tendency have moved us further and further away. What we have achieved has been rather a cosmopolitan federation of national colonies, of foreign cultures, from whom the sting of devastating competition has been removed. America is already the world-federation in miniature, the continent where for the first time in history has been achieved that miracle of hope, the peaceful living side by side, with character substantially preserved, of the most heterogeneous peoples under the sun. Nowhere else has such contiguity been anything but the breeder of misery. Here, notwithstanding our tragic failures of adjustment, the outlines are already too clear not to give us a new vision and a new orientation of the American mind in the world.

It is for the American of the younger generation to accept this cosmopolitanism, and carry it along with selfconscious and fruitful purpose. In his colleges, he is already getting, with the study of modern history and politics, the modern literatures, economic geography, the privilege of a cosmopolitan outlook such as the people of no other nation of to-day in Europe can possibly secure. If he is still a colonial, he is no longer the colonial of one partial culture, but of many. He is a colonial of the world. Colonialism has grown into cosmopolitanism, and his mother land is no one nation, but all who have anything life-enhancing to offer to the spirit. That vague sympathy which the France of ten years ago was feeling for the world—a sympathy which was drowned in the terrible reality of war—may be the modern American’s, and that in a positive and aggressive sense. If the American is parochial, it is in sheer wantonness or cowardice. His provincialism is the measure of his fear of bogies or the defect of his imagination.

Indeed, it is not uncommon for the eager Anglo-Saxon who goes to a vivid American university to-day to find his true friends not among his own race but among the acclimatized German or Austrian, the acclimatized Jew, the acclimatized Scandinavian or Italian. In them he finds the cosmopolitan note. In these youths, foreign-born or the children of foreign-born parents, he is likely to find many of his old inbred morbid problems washed away. These friends are oblivious to the repressions of that tight little society in which he so provincially grew up. He has a pleasurable sense of liberation from the stale and familiar attitudes of those whose ingrowing culture has scarcely created anything vital for his America of to-day. He breathes a larger air. In his new enthusiasms for continental literature, for unplumbed Russian depths, for French clarity of thought, for Teuton philosophies of power, he feels himself citizen of a larger world. He may be absurdly superficial, his outward-reaching wonder may ignore all the stiller and homelier virtues of his Anglo-Saxon home, but he has at least found the clue to that international mind which will be essential to all men and women of good-will if they are ever to save this Western world of ours from suicide. His new friends have gone through a similar evolution. America has burned most of the baser metal also from them. Meeting now with this common American background, all of them may yet retain that distinctiveness of their native cultures and their national spiritual slants. They are more valuable and interesting to each other for being different, yet that difference could not be creative were it not for this new cosmopolitan outlook which America has given them and which they all equally possess.

A college where such a spirit is possible even to the smallest degree, has within itself already the seeds of this international intellectual world of the future. It suggests that the contribution of America will be an intellectual internationalism which goes far beyond the mere exchange of scientific ideas and discoveries and the cold recording of facts. It will be an intellectual sympathy which is not satisfied until it has got at the heart of the different cultural expressions, and felt as they feel. It may have immense preferences, but it will make understanding and not indignation its end. Such a sympathy will unite and not divide.

Against the thinly disguised panic which calls itself ‘patriotism’ and the thinly disguised militarism which calls itself ‘preparedness’ the cosmopolitan ideal is set. This does not mean that those who hold it are for a policy of drift. They, too, long passionately for an integrated and disciplined America. But they do not want one which is integrated only for domestic economic exploitation of the workers or for predatory economic imperialism among the weaker peoples. They do not want one that is integrated by coercion or militarism, or for the truculent assertion of a medieval code of honor and of doubtful rights. They believe that the most effective integration will be one which coordinates the diverse elements and turns them consciously toward working out together the place of America in the world-situation. They demand for integration a genuine integrity, a wholeness and soundness of enthusiasm and purpose which can only come when no national colony within our America feels that it is being discriminated against or that its cultural case is being prejudged. This strength of cooperation, this feeling that all who are here may have a hand in the destiny of America, will make for a finer spirit of integration than any narrow ‘Americanism’ or forced chauvinism.

In this effort we may have to accept some form of that dual citizenship which meets with so much articulate horror among us. Dual citizenship we may have to recognize as the rudimentary form of that international citizenship to which, if our words mean anything, we aspire. We have assumed unquestioningly that mere participation in the political life of the United States must cut the new citizen off from all sympathy with his old allegiance. Anything but a bodily transfer of devotion from one sovereignty to another has been viewed as a sort of moral treason against the Republic. We have insisted that the immigrant whom we welcomed escaping from the very exclusive nationalism of his European home shall forthwith adopt a nationalism just as exclusive, just as narrow, and even less legitimate because it is founded on no warm traditions of his own. Yet a nation like France is said to permit a formal and legal dual citizenship even at the present time. Though a citizen of hers may pretend to cast off his allegiance in favor of some other sovereignty, he is still subject to her laws when he returns. Once a citizen, always a citizen, no matter how many new citizenships he may embrace. And such a dual citizenship seems to us sound and right. For it recognizes that, although the Frenchman may accept the formal institutional framework of his new country and indeed become intensely loyal to it, yet his Frenchness he will never lose. What makes up the fabric of his soul will always be of this Frenchness, so that unless he becomes utterly degenerate he will always to some degree dwell still in his native environment.

Indeed, does not the cultivated American who goes to Europe practice a dual citizenship, which, if not formal, is no less real? The American who lives abroad may be the least expatriate of men. If he falls in love with French ways and French thinking and French democracy and seeks to saturate himself with the new spirit, he is guilty of at least a dual spiritual citizenship. He may be still American, yet he feels himself through sympathy also a Frenchman. And he finds that this expansion involves no shameful conflict within him, no surrender of his native attitude. He has rather for the first time caught a glimpse of the cosmopolitan spirit. And after wandering about through many races and civilizations he may return to America to find them all here living vividly and crudely, seeking the same adjustment that he made. He sees the new peoples here with a new vision. They are no longer masses of aliens, waiting to be ‘assimilated,’ waiting to be melted down into the indistinguishable dough of Anglo-Saxonism. They are rather threads of living and potent cultures, blindly striving to weave themselves into a novel international nation, the first the world has seen. In an Austria-Hungary or a Prussia the stronger of these cultures would be moving almost instinctively to subjugate the weaker. But in America those wills-to-power are turned in a different direction into learning how to live together.

Along with dual citizenship we shall have to accept, I think, that free and mobile passage of the immigrant between America and his native land again which now arouses so much prejudice among us. We shall have to accept the immigrant’s return for the same reason that we consider justified our own flitting about the earth. To stigmatize the alien who works in America for a few years and returns to his own land, only perhaps to seek American fortune again, is to think in narrow nationalistic terms. It is to ignore the cosmopolitan significance of this migration. It is to ignore the fact that the returning immigrant is often a missionary to an inferior civilization.

This migratory habit has been especially common with the unskilled laborers who have been pouring into the United States in the last dozen years from every country in southeastern Europe. Many of them return to spend their earnings in their own country or to serve their country in war. But they return with an entirely new critical outlook, and a sense of the superiority of American organization to the primitive living around them. This continued passage to and fro has already raised the material standard of labour in many regions of these backward countries. For these regions are thus endowed with exactly what they need, the capital for the exploitation of their natural resources, and the spirit of enterprise. America is thus educating these laggard peoples from the very bottom of society up, awaking vast masses to a new-born hope for the future. In the migratory Greek, therefore, we have not the parasitic alien, the doubtful American asset, but a symbol of that cosmopolitan interchange which is coming, in spite of all war and national exclusiveness.

Only America, by reason of the unique liberty of opportunity and traditional isolation for which she seems to stand, can lead in this cosmopolitan enterprise. Only the American—and in this category I include the migratory alien who has lived with us and caught the pioneer spirit and a sense of new social vistas—has the chance to become that citizen of the world. America is coming to be, not a nationality but a trans-nationality, a weaving back and forth, with the other lands, of many threads of all sizes and colors. Any movement which attempts to thwart this weaving, or to dye the fabric any one color, or disentangle the threads of the strands, is false to this cosmopolitan vision. I do not mean that we shall necessarily glut ourselves with the raw product of humanity. It would be folly to absorb the nations faster than we could weave them. We have no duty either to admit or reject. It is purely a question of expediency. What concerns us is the fact that the strands are here. We must have a policy and an ideal for an actual situation. Our question is, What shall we do with our America? How are we likely to get the more creative America—by confining our imaginations to the ideal of the melting-pot, or broadening them to some such cosmopolitan conception as I have been vaguely sketching?

The war has shown America to be unable, though isolated geographically and politically from a European world-situation, to remain aloof and irresponsible. She is a wandering star in a sky dominated by two colossal constellations of states. Can she not work out some position of her own, some life of being in, yet not quite of, this seething and embroiled European world? This is her only hope and promise. A trans-nationality of all the nations, it is spiritually impossible for her to pass into the orbit of any one. It will be folly to hurry herself into a premature and sentimental nationalism, or to emulate Europe and play fast and loose with the forces that drag into war. No Americanization will fulfill this vision which does not recognize the uniqueness of this trans-nationalism of ours. The Anglo-Saxon attempt to fuse will only create enmity and distrust. The crusade against ‘hyphenates’ will only inflame the partial patriotism of trans-nationals, and cause them to assert their European traditions in strident and unwholesome ways. But the attempt to weave a wholly novel international nation out of our chaotic America will liberate and harmonize the creative power of all these peoples and give them the new spiritual citizenship, as so many individuals have already been given, of a world.

Is it a wild hope that the undertow of opposition to metaphysics in international relations, opposition to militarism, is less a cowardly provincialism than a groping for this higher cosmopolitan ideal? One can understand the irritated restlessness with which our proud pro-British colonists contemplate a heroic conflict across the seas in which they have no part. It was inevitable that our necessary inaction should evolve in their minds into the bogey of national shame and dishonor. But let us be careful about accepting their sensitiveness as final arbiter. Let us look at our reluctance rather as the first crude beginnings of assertion on the part of certain strands in our nationality that they have a right to a voice in the construction of the American ideal. Let us face realstically the America we have around us. Let us work with the forces that are at work. Let us make something of this trans-national spirit instead of outlawing it. Already we are living this cosmopolitan America. What we need is everywhere a vivid consciousness of the new ideal. Deliberate headway must be made against the survivals of the melting pot ideal for the promise of American life.

We cannot Americanize America worthily by sentimentalizing and moralizing history. When the best schools are expressly renouncing the questionable duty of teaching patriotism by means of history, it is not the time to force shibboleth upon the immigrant. This form of Americanization has been heard because it appealed to the vestiges of our old sentimentalized and moralized patriotism. This has so far held the field as the expression of the new American’s new devotion. The inflections of other voices have been drowned. They must be heard. We must see if the lesson of the war has not been for hundreds of these later Americans a vivid realization of their trans-nationality, a new consciousness of what America meant to them as a citizenship in the world. It is the vague historic idealisms which have provided the fuel for the European flame. Our American ideal can make no progress until we do away with this romantic gilding of the past.

All our idealisms must be those of future social goals in which all can participate, the good life of personality lived in the environment of the Beloved Community. No mere doubtful triumphs of the past, which redound to the glory of only one of our transnationalities, can satisfy us. It must be a future America, on which all can unite, which pulls us irresistibly toward it, as we understand each other more warmly.

To make real this striving amid dangers and apathies is work for a younger intelligentsia of America. Here is an enterprise of integration into which we can all pour ourselves, of a spiritual welding which should make us, if the final menace ever came, no weaker, but infinitely strong.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Easter Rising

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 25, 2019 | Original: November 9, 2009

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, a group of Irish nationalists proclaimed the establishment of the Irish Republic and, along with some 1,600 followers, staged a rebellion against the British government in Ireland. The rebels seized prominent buildings in Dublin and clashed with British troops. Within a week, the insurrection had been suppressed and more than 2,000 people were dead or injured. The leaders of the rebellion soon were executed. Initially, there was little support from the Irish people for the Easter Rising; however, public opinion later shifted and the executed leaders were hailed as martyrs. In 1921, a treaty was signed that in 1922 established the Irish Free State, which eventually became the modern-day Republic of Ireland.

1916 Easter Rising: Background

With the Acts of Union in 1800 (ratified in 1801), Ireland (which had been under some form of English control since the 12th century) merged with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. As a result, Ireland lost its parliament in Dublin and was governed by a united parliament from Westminster in London. During the 19th century, groups of Irish nationalists opposed this arrangement in varying degrees.

Did you know? After the Easter Rising, one of the rebels, American-born Eamon de Valera, was sentenced to death. However, he ended up serving only a brief prison term and went on to become one of Ireland’s leading political figures, with a career spanning half a century.

Some moderate nationalists advocated for home rule, under which Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom but also have some form of self-government. Several home rule bills were defeated in Parliament in the late 1800s before one finally passed in 1914. However, implementation of home rule was suspended due to the outbreak of World War I (1914-18).

Meanwhile, members of a secret revolutionary organization called the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), who believed home rule wouldn’t go far enough and instead sought complete independence for Ireland, began planning what would become the Easter Rising. They hoped their rebellion would be aided by military support from Germany, which was fighting the British in World War I. Roger Casement (1864-1916), an Irish nationalist, arranged for a shipment of German arms and ammunition for the rebels; however, shortly before the insurrection began, the British detected the ship and it was scuttled by its captain. Casement was charged with treason and executed in August 1916

Easter Rising: April 1916

The Easter Rising was intended to take place across Ireland; however, various circumstances resulted in it being carried out primarily in Dublin. On April 24, 1916, the rebel leaders and their followers (whose numbers reached some 1,600 people over the course of the insurrection, and many of whom were members of a nationalist organization called the Irish Volunteers, or a small radical militia group, the Irish Citizen Army), seized the city’s general post office and other strategic locations. Early that afternoon, from the steps of the post office, Patrick Pearse (1879-1916), one of the uprising’s leaders, read a proclamation declaring Ireland an independent republic and stating that a provisional government (comprised of IRB members) had been appointed.

Despite the rebels’ hopes, the public did not rise to support them. The British government soon declared martial law in Ireland, and in less than a week the rebels were crushed by the government forces sent against them. Some 450 people were killed and more than 2,000 others, many of them civilians, were wounded in the violence, which also destroyed much of the Dublin city center.

1916 Easter Rising: Aftermath

Initially, many Irish people resented the rebels for the destruction and death caused by the uprising. However, in May, 15 leaders of the uprising were executed by firing squad. More than 3,000 people suspected of supporting the uprising, directly or indirectly, were arrested, and some 1,800 were sent to England and imprisoned there without trial. The rushed executions, mass arrests and martial law (which remained in effect through the fall of 1916), fueled public resentment toward the British and were among the factors that helped build support for the rebels and the movement for Irish independence.

In the 1918 general election to the parliament of the United Kingdom, the Sinn Fein political party (whose goal was to establish a republic) won a majority of the Irish seats. The Sinn Fein members then refused to sit in the UK Parliament, and in January 1919 met in Dublin to convene a single chamber parliament and declare Ireland’s independence. The Irish Republican Army then launched a guerrilla war against the British government and its forces in Ireland. Following a July 1921 cease-fire, the two sides signed a treaty in December that called for the establishment of the Irish Free State, a self-governing nation of the British Commonwealth, the following year. Ireland’s six northern counties opted out of the Free State and remained with the United Kingdom. The fully independent Republic of Ireland (consisting of the 26 counties in the southern and western part of the island) was formally proclaimed on Easter Monday, April 18, 1949.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The New York Times

Magazine | the 1619 project, the 1619 project.

AUG. 14, 2019

In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the English colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed. On the 400th anniversary of this fateful moment, it is finally time to tell our story truthfully.

Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written. black americans have fought to make them true., if you want to understand the brutality of american capitalism, you have to start on the plantation., myths about physical racial differences were used to justify slavery — and are still believed by doctors today., america holds onto an undemocratic assumption from its founding: that some people deserve more power than others., for centuries, black music has been the sound of artistic freedom. no wonder everybody’s always stealing it., ‘i slide my ring finger from senegal to south carolina & feel the ocean separate a million families.’, what does a traffic jam in atlanta have to do with segregation quite a lot., why doesn’t the united states have universal health care the answer begins with policies enacted after the civil war., slavery gave america a fear of black people and a taste for violent punishment. both still define our prison system., the sugar that saturates the american diet has a barbaric history as the ‘white gold’ that fueled slavery., a vast wealth gap, driven by segregation, redlining, evictions and exclusion, separates black and white america., a re-education is necessary., most americans still don’t know the full story of slavery. this is the history you didn’t learn in school., ‘we are committing educational malpractice’: why slavery is mistaught — and worse — in american schools., the 1619 project continues, the 1619 podcast.

An audio series from The Times observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery.

Live at the Smithsonian

Watch highlights of a symposium about how history is defined — and redefined — featuring historians, journalists and policymakers.

Reader Responses