- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2018

The Syrian conflict: a case study of the challenges and acute need for medical humanitarian operations for women and children internally displaced persons

- Rahma Aburas 1 ,

- Amina Najeeb 2 ,

- Laila Baageel 3 &

- Tim K. Mackey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2191-7833 3 , 4 , 5

BMC Medicine volume 16 , Article number: 65 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

28 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

After 7 years of increasing conflict and violence, the Syrian civil war now constitutes the largest displacement crisis in the world, with more than 6 million people who have been internally displaced. Among this already-vulnerable population group, women and children face significant challenges associated with lack of adequate access to maternal and child health (MCH) services, threatening their lives along with their immediate and long-term health outcomes.

While several health and humanitarian aid organizations are working to improve the health and welfare of internally displaced Syrian women and children, there is an immediate need for local medical humanitarian interventions. Responding to this need, we describe the case study of the Brotherhood Medical Center (the “Center”), a local clinic that was initially established by private donors and later partnered with the Syrian Expatriate Medical Association to provide free MCH services to internally displaced Syrian women and children in the small Syrian border town of Atimah.

Conclusions

The Center provides a unique contribution to the Syrian health and humanitarian crisis by focusing on providing MCH services to a targeted vulnerable population locally and through an established clinic. Hence, the Center complements efforts by larger international, regional, and local organizations that also are attempting to alleviate the suffering of Syrians victimized by this ongoing civil war. However, the long-term success of organizations like the Center relies on many factors including strategic partnership building, adjusting to logistical difficulties, and seeking sustainable sources of funding. Importantly, the lessons learned by the Center should serve as important principles in the design of future medical humanitarian interventions working directly in conflict zones, and should emphasize the need for better international cooperation and coordination to support local initiatives that serve victims where and when they need it the most.

Peer Review reports

The Syrian civil war is the epitome of a health and humanitarian crisis, as highlighted by recent chemical attacks in a Damascus suburb, impacting millions of people across Syria and leading to a mass migration of refugees seeking to escape this protracted and devastating conflict. After 7 long years of war, more than 6 million people are internally displaced within Syria — the largest displacement crisis in the world — and more than 5 million registered Syrian refugees have been relocated to neighboring countries [ 1 , 2 ]. In total, this equates to an estimated six in ten Syrians who are now displaced from their homes [ 3 ].

Syrian internally displaced persons (IDPs) are individuals who continue to reside in a fractured Syrian state now comprising a patchwork of government- and opposition-held areas suffering from a breakdown in governance [ 4 ]. As the Syrian conflict continues, the number of IDPs and Syrian refugees continues to grow according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This growth is continuing despite some borders surrounding Syria being closed and in part due to a rising birth rate in refugee camps [ 5 , 6 ]. This creates acute challenges for neighboring/receiving countries in terms of ensuring adequate capacity to offer essential services such as food, water, housing, security, and specifically healthcare [ 4 , 7 , 8 ].

Though Syrian refugees and IDPs face similar difficulties in relation to healthcare access in a time of conflict and displacement, their specific challenges and health needs are distinctly different, as IDPs lack the same rights guaranteed under international law as refugees, and refugees have variations in access depending on their circumstances. Specifically, there are gaps in access to medical care and medicines for both the internally displaced and refugees, whether it be in Syria, in transit countries (including services for refugees living in camps versus those living near urban cities), or in eventual resettlement countries. In particular, treatment of chronic diseases and accessing of hospital care can be difficult, exacerbated by Syrian families depleting their savings, increased levels of debt, and a rise in those living in poverty (e.g., more than 50% of registered Syrian refugees in Jordan are burdened with debt) [ 9 ].

Despite ongoing actions of international humanitarian organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to alleviate these conditions, healthcare access and coverage for displaced Syrians and refugees is getting worse as the conflict continues [ 4 , 10 ]. Although Syria operated a strong public health system and was experiencing improved population health outcomes pre-crisis, the ongoing conflict, violence, and political destabilization have led to its collapse [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Specifically, campaigns of violence against healthcare infrastructure and workers have led to the dismantling of the Syrian public health system, particularly in opposition-held areas, where access to even basic preventive services has been severely compromised [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Collectively, these dire conditions leave millions of already-vulnerable Syrians without access to essential healthcare services, a fundamental human right and one purportedly guaranteed to all Syrian citizens under its constitution [ 4 ]. Importantly, at the nexus of this health and humanitarian crisis are the most vulnerable: internally displaced Syrian women and children. Hence, this opinion piece first describes the unique challenges and needs faced by this vulnerable population and then describes the case study of the Brotherhood Medical Center (the “Center”), an organization established to provide free and accessible maternal and child health (MCH) services for Syrian IDPs, and how it represents lessons regarding the successes and ongoing challenges of a local medical humanitarian intervention.

Syria: a health crisis of the vulnerable

Critically, women and children represent the majority of all Syrian IDPs and refugees, which directly impacts their need for essential MCH services [ 18 ]. Refugee and internally displaced women and children face similar health challenges in conflict situations, as they are often more vulnerable than other patient populations, with pregnant women and children at particularly high risk for poor health outcomes that can have significant short-term, long-term, and inter-generational health consequences [ 10 ]. Shared challenges include a lack of access to healthcare and MCH services, inadequate vaccination coverage, risk of malnutrition and starvation, increased burden of mental health issues due to exposure to trauma, and other forms of exploitation and violence such as early marriage, abuse, discrimination, and gender-based violence [ 4 , 10 , 19 , 20 ]. Further, scarce medical resources are often focused on patients suffering from acute and severe injury and trauma, leading to de-prioritization of other critical services like MCH [ 4 ].

Risks for women

A 2016 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) report estimated that 360,000 Syrian IDPs are pregnant, yet many do not receive any antenatal or postnatal care [ 21 , 22 ]. According to estimates by the UNFPA in 2015, without adequate international funding, 70,000 pregnant Syrian women faced the risk of giving birth in unsafe conditions if access to maternal health services was not improved [ 23 ]. For example, many women cannot access a safe place with an expert attendant for delivery and also may lack access to emergency obstetric care, family planning services, and birth control [ 4 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. By contrast, during pre-conflict periods, Syrian women enjoyed access to standard antenatal care, and 96% of deliveries (whether at home or in hospitals) were assisted by a skilled birth attendant [ 13 ]. This coverage equated to improving population health outcomes, including data from the Syrian Ministry of Health reporting significant gains in life expectancy at birth (from 56 to 73.1 years), reductions in infant mortality (decrease from 132 per 1000 to 17.9 per 1000 live births), reductions in under-five mortality (from 164 to 21.4 per 1000 live births), and declines in maternal mortality (from 482 to 52 per 100,000 live births) between 1970 and 2009, respectively [ 13 ].

Post-conflict, Syrian women now have higher rates of poor pregnancy outcomes, including increased fetal mortality, low birth weights, premature labor, antenatal complications, and an increase in puerperal infections, as compared to pre-conflict periods [ 10 , 13 , 25 , 26 ]. In general, standards for antenatal care are not being met [ 29 ]. Syrian IDPs therefore experience further childbirth complications such as hemorrhage and delivery/abortion complications and low utilization of family planning services [ 25 , 28 ]. Another example of potential maternal risk is an alarming increase in births by caesarean section near armed conflict zones, as women elect for scheduled caesareans to avoid rushing to the hospital during unpredictable and often dangerous circumstances [ 10 ]. There is similar evidence from Syrian refugees in Lebanon, where rates of caesarean sections were 35% (of 6366 deliveries assessed) compared to approximately 15% as previously recorded in Syria and Lebanon [ 30 ].

Risks for children

Similar to the risks experienced by Syrian women, children are as vulnerable or potentially at higher risk during conflict and health and humanitarian crises. According to the UNHCR, there are 2.8 million children displaced in Syria out of a total of 6.5 million persons, and just under half (48%) of Syrian registered refugees are under 18 years old [ 1 ]. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) further estimates that 6 million children still living in Syria are in need of humanitarian assistance and 420,000 children in besieged areas lack access to vital humanitarian aid [ 31 ].

For most Syrian internally displaced and refugee children, the consequences of facing lack of access to essential healthcare combined with the risk of malnutrition (including cases of severe malnutrition and death among children in besieged areas) represent a life-threatening challenge (though some studies have positively found low levels of global acute malnutrition in Syrian children refugee populations) [ 24 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Additionally, UNICEF reports that pre-crisis 90% of Syrian children received routine vaccination, with this coverage now experiencing a dramatic decline to approximately 60% (though estimating vaccine coverage in Syrian IDP and refugee populations can be extremely difficult) [ 35 ]. A consequence of lack of adequate vaccine coverage is the rise of deadly preventable infectious diseases such as meningitis, measles, and even polio, which was eradicated in Syria in 1995, but has recently re-emerged [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Syrian refugee children are also showing symptoms of psychological trauma as a result of witnessing the war [ 4 , 39 ].

A local response: the Brotherhood Medical Center

In direct response to the acute needs faced by Syrian internally displaced women and children, we describe the establishment, services provided, and challenges faced by the Brotherhood Medical Center (recently renamed the Brotherhood Women and Children Specialist Center and hereinafter referred to as the “Center”), which opened its doors to patients in September 2014. The Center was the brainchild of a group of Syrian and Saudi physicians and donors who had the aim of building a medical facility to address the acute need for medical humanitarian assistance in the village of Atimah (Idlib Governorate, Syria), which is also home to a Syrian displacement camp.

Atimah (Idlib Governorate, Syria) is located on the Syrian side of the Syrian-Turkish border. Its population consisted of 250,000 people pre-conflict in an area of approximately 65 km 2 . Atimah and its adjacent areas are currently generally safe from the conflict, with both Atimah and the entire Idlib Governorate outside the control of the Syrian government and instead governed by the local government. However, continued displacement of Syrians seeking to flee the conflict has led to a continuous flow of Syrian families into the area, with the population of the town growing to approximately a million people.

In addition to the Center, there are multiple healthcare centers and field hospitals serving Atimah and surrounding areas that cover most medical specialties. These facilities are largely run by local and international health agencies including Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), Medical Relief for Syria, and Hand in Hand for Syria, among others. Despite the presence of these organizations, the health needs of IDPs exceeds the current availability of healthcare services, especially for MCH services, as the majority of the IDPs belong to this patient group. This acute need formed the basis for the project plan establishing the Center to serve the unique needs of Syrian internally displaced women and children.

Operation of the Center

The Center’s construction and furnishing took approximately 1 year after land was purchased for its facility, a fact underlining the urgency of building a permanent local physical infrastructure to meet healthcare needs during the midst of a conflict. Funds to support its construction originated from individual donors, Saudi business men, and a group of physicians. In this sense, the Center represents an externally funded humanitarian delivery model focused on serving a local population, with no official government, NGO, or international organization support for its initial establishment.

The facility’s primary focus is to serve Syrian women and children, but since its inception in 2014, the facility has grown to cater for an increasing number of IDPs and their diverse needs. When it opened, facility services were limited to offering only essential outpatient, gynecology, and obstetrics services, as well as operating a pediatric clinic. The staffing at the launch consisted of only three doctors, a midwife, a nurse, an administrative aid, and a housekeeper, but there now exist more than eight times this initial staff count. The staff operating the Center are all Syrians; some of them are from Atimah, but many also come from other places in Syria. The Center’s staff are qualified to a large extent, but still need further training and continuing medical education to most effectively provide services.

Though staffing and service provision has increased, the Center’s primary focus is on its unique contribution to internally displaced women and children. Expanded services includes a dental clinic 1 day per week, which is run by a dentist with the Health Affairs in Idlib Governorate, and has been delegated to cover the dental needs for the hospital patients . Importantly, the Center facility has no specific policy on patient eligibility, its desired patient catchment population/area, or patient admission, instead opting to accept all women and children patients, whether seeking routine or urgent medical care, and providing its services free of charge.

Instead of relying on patient-generated fees (which may be economically prohibitive given the high levels of debt experienced by IDPs) or government funding, the Center relies on its existing donor base for financing the salaries for its physicians and other staff as well as the facility operating costs. More than an estimated 300 patients per day have sought medical attention since its first day of operation, with the number of patients steadily increasing as the clinic has scaled up its services.

Initially the Center started with outpatient (OPD) cases only, and after its partnership with the Syrian Expatriate Medical Association (SEMA) (discussed below), inpatient care for both women and children began to be offered. Patients’ statistics for September 2017 reported 3993 OPD and emergency room visits and 315 inpatient admissions including 159 normal deliveries and 72 caesarean sections, 9 neonatal intensive care unit cases, and 75 admissions for other healthcare services. To better communicate the clinic’s efforts, the Center also operates a Facebook page highlighting its activities (in Arabic at https://www.facebook.com/مشفى-الإخاء-التخصصي-129966417490365/ ).

Challenges faced by the Center and its evolution

The first phase of the Center involved its launch and initial operation in 2014 supported by a small group of donors who self-funded the startup costs needed to operationalize the Center facility’s core clinical services. Less than 2 years later, the Center faced a growing demand for its services, a direct product of both its success in serving its targeted community and the protracted nature of the Syrian conflict. In other words, the Center facility has continuously needed to grow in the scope of its service delivery as increasing numbers of families, women, and children rely on the Center as their primary healthcare facility and access point.

Meeting this increasing need has been difficult given pragmatic operational challenges emblematic of conflict-driven zones, including difficulties in securing qualified and trained medical professionals for clinical services, financing problems involving securing funding due to the shutdown of banking and money transferring services to and from Syria, and macro political factors (such as the poor bilateral relationship between Syria and its neighboring countries) that adversely affect the clinic’s ability to procure medical and humanitarian support and supplies [ 40 ]. Specifically, the Center as a local healthcare facility originally had sufficient manpower and funding provided by its initial funders for its core operations and construction in its first year of operation. However, maintaining this support became difficult with the closure of the Syrian-Turkish border and obstacles in receiving remittances, necessitating the need for broader strategic partnership with a larger organization.

Collectively, these challenges required the management committee and leadership of the Center to shift its focus to securing long-term sustainability and scale-up of services by seeking out external forms of cooperation and support. Borne from this need was a strategic partnership with SEMA, designed to carry forward the next phase of the Center’s operation and development. SEMA, established in 2011, is a non-profit relief organization that works to provide and improve medical services in Syria without discrimination regarding gender, ethnic, or political affiliation — a mission that aligns with the institutional goals of the Center. Selection of SEMA as a partner was based on its activity in the region; SEMA plays an active role in healthcare provision in Idlib and surrounding areas. Some other organizations were also approached at the same time of this organization change, with SEMA being the most responsive.

Since the Center-SEMA partnership was consummated, the Center has received critical support in increasing its personnel capacity and access to medicines, supplies, and equipment, resulting in a gradual scale-up and improvement in its clinical services. This now includes expanded pediatric services and the dental clinic (as previously mentioned and important, as oral health is a concern for many Syrian parents and children). The Center also now offers caesarean deliveries [ 41 ]. However, the Center, similar to other medical humanitarian operations in the region, continues to face many financial and operational challenges, including shortage of medical supplies, lack of qualified medical personnel, and needs for staff development.

Challenges experienced by the Center and other humanitarian operations continue to be exacerbated by the ongoing threat of violence and instability emanating from the conflict that is often targeted at local organizations and international NGOs providing health aid. For example, MSF has previously been forced to suspend its operations in other parts of Syria, has evacuated its facilities after staff have been abducted and its facilities bombed, and it has also been subject to threats from terrorist groups like the Islamic State (IS) [ 42 ].

The case study of the Center, which evolved from a rudimentary medical tent originally located directly in the Atimah displacement camp to the establishment of a local medical facility now serving thousands of Syrian IDPs, is just one example of several approaches aimed at alleviating the suffering of Syrian women and children who have been disproportionately victimized by this devastating health and humanitarian crisis. Importantly, the Center represents the maturation of a privately funded local operation designed to meet an acute community need for MCH services, but one that has necessitated continuous change and evolution as the Syrian conflict continues and conditions worsen. Despite certain successes, a number of challenges remain that limit the potential of the Center and other health humanitarian operations to fully serve the needs of Syrian IDPs, all of which should serve as cautionary principles for future local medical interventions in conflict situations.

A primary challenge is the myriad of logistical difficulties faced by local medical humanitarian organizations operating in conflict zones. Specifically, the Center continues to experience barriers in securing a reliable and consistent supply of medical equipment and materials needed to ensure continued operation of its clinical services, such as its blood bank, laboratory services, operating rooms, and intensive care units. Another challenge is securing the necessary funding to make improvements to physical infrastructure and hire additional staff to increase clinical capacity. Hence, though local initiatives like the Center may have initial success getting off the ground, scale-up and ensuring sustainability of services to meet the increasing needs of patients who remain in a perilous conflict-driven environment with few alternative means of access remain extremely challenging.

Despite these challenges, it is clear that different types of medical humanitarian interventions deployed in the midst of health crises have their own unique roles and contributions. This includes a broad scope of activities now focused on improving health outcomes for Syrian women and children that are being delivered by international aid agencies located outside of the country, international or local NGOs, multilateral health and development agencies, and forms of bilateral humanitarian assistance. The Center contributes to this health and humanitarian ecosystem by providing an intervention focused on the needs of Syrian women and children IDPs where they need it most, close to home.

However, the success of the Center and other initiatives working to end the suffering of Syrians ultimately relies on macro organizational and political issues outside Atimah’s border. This includes better coordination and cooperation of aid and humanitarian stakeholders and increased pressure from the international community to finally put an end to a civil war that has no winners — only victims — many of whom are unfortunately women and children.

Abbreviations

the Brotherhood Women and Children Specialist Center

Internally displaced persons

Maternal and child health

Medecins Sans Frontieres

Non-governmental organizations

Outpatient department

Syrian Expatriate Medical Association

United Nations Population Fund

the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations Children’s Fund

UNHCR. Syria Regional Refugee Response: Inter-agency Information Sharing Portal [Internet]. data.unhcr.org. 2017. http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php . Accessed 17 July 2017.

iDMC. Syria [Internet]. 2017. http://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/syria . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Connor P, Krogstad JM. About six-in-ten Syrians are now displaced from their homes [Internet]. pewresearch.org. 2016. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/13/about-six-in-ten-syrians-are-now-displaced-from-their-homes/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Akbarzada S, Mackey TK. The Syrian public health and humanitarian crisis: a “displacement” in global governance? Glob Public Health. 2017;44:1–17.

Article Google Scholar

Albaster O. Birth rate soars in refugee camp as husbands discourage use of contraception [Internet]. 2016. independent.co.uk . http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/birth-rate-soars-in-jordan-refugee-camp-as-husbands-discourage-wives-from-using-contraception-a6928241.html . Accessed 21 Nov 2017.

Reliefweb. Closing Borders, Shifting Routes: Summary of Regional Migration Trends Middle East – May, 2016 [Internet]. reliefweb.int. 2016. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/closing-borders-shifting-routes-summary-regional-migration-trends-middle-east-may-2016 . Accessed 21 Nov 2017.

Schweiger G. The duty to bring children living in conflict zones to a safe haven. J Glob Ethics. 2016;12:380–97.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arcos González P, Cherri Z, Castro Delgado R. The Lebanese–Syrian crisis: impact of influx of Syrian refugees to an already weak state. RMHP. 2016;9:165–72.

UNHCR and partners warn in Syria report of growing poverty, refugee needs. Geneva: UNHCR; 2016.

Devakumar D, Birch M, Rubenstein LS, Osrin D, Sondorp E, Wells JCK. Child health in Syria: recognising the lasting effects of warfare on health. Confl Heal. 2015;9:34.

Ferris E, Kirişçi K, Shaikh S. Syrian crisis: massive displacement, dire needs and a shortage of solutions. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2013.

Google Scholar

Abu-Sada C, Serafini M. Humanitarian and medical challenges of assisting new refugees in Lebanon and Iraq. Forced Migr Rev. 2013:1:70–3.

Kherallah M, Sahloul Z, Jamil G, Alahfez T, Eddin K. Health care in Syria before and during the crisis. Avicenna J Med. 2012;2:51–3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0770.102275

Heisler M, Baker E, McKay D. Attacks on health care in Syria — normalizing violations of medical neutrality? N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2489–91.

Cook J. Syrian medical facilities were attacked more than 250 times this year [Internet]. huffingtonpost.com . 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/syria-hospital-attacks_us_56c330f0e4b0c3c550528d2e . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Ozaras R, Leblebicioglu H, Sunbul M, Tabak F, Balkan II, Yemisen M, et al. The Syrian conflict and infectious diseases. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2016;14:547–55.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fouad FM, Sparrow A, Tarakji A, Alameddine M, El-Jardali F, Coutts AP, et al. Health workers and the weaponisation of health care in Syria: a preliminary inquiry for The Lancet-American University of Beirut Commission on Syria. Lancet. 2017:390:2516–26;

Women in the World. Women and children now make up the majority of refugees [Internet]. nytimes.com. 2016. http://nytlive.nytimes.com/womenintheworld/2016/05/16/women-and-children-now-make-up-the-majority-of-refugees/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Yasmine R, Moughalian C. Systemic violence against Syrian refugee women and the myth of effective intrapersonal interventions. Reprod Health Matters. 2016;24:27–35.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Elsafti AM, van Berlaer G, Safadi Al M, Debacker M, Buyl R, Redwan A, et al. Children in the Syrian civil war: the familial, educational, and public health impact of ongoing violence. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2016;10:874–82.

Save the Children. A devastating toll: the impact of three years of war on the health of Syria's children [Internet]. 2014. http://www.savethechildren.org/atf/cf/%7B9def2ebe-10ae-432c-9bd0-df91d2eba74a%7D/SAVE_THE_CHILDREN_A_DEVASTATING_TOLL.PDF . Accessed 12 Jan 2016.

UNFPA. Women and girls in the Syria crisis: UNFA response [Internet]. unfpa.org. 2015. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/UNFPA-FACTSANDFIGURES-5%5B4%5D.pdf . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

UNFPA. Shortage in funding threatens care for pregnant Syrian refugees [Internet]. unfpa.org. 2015. http://www.unfpa.org/news/shortage-funding-threatens-care-pregnant-syrian-refugees . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Bilukha OO, Jayasekaran D, Burton A, Faender G, King’ori J, Amiri M, et al. Nutritional status of women and child refugees from Syria-Jordan, April-May 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:638–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Reese Masterson A, Usta J, Gupta J, Ettinger AS. Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:25.

Samari G. Syrian refugee women’s health in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan and recommendations for improved practice. World Med Health Policy. 2017;9:255–74.

Hakeem O, Jabri S. Adverse birth outcomes in women exposed to Syrian chemical attack. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e196. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(15)70077-x

West L, Isotta-Day H, Ba-Break M, Morgan R. Factors in use of family planning services by Syrian women in a refugee camp in Jordan. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2016. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101026.

Benage M, Greenough P, Vinck P, Omeira N, Pham P. An assessment of antenatal care among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Confl Heal. 2015;9:8.

Huster KMJ, Patterson N, Schilperoord M, Spiegel P. Cesarean sections among Syrian refugees in Lebanon from December 2012/January 2013 to June 2013: probable causes and recommendations. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87:269–88.

UNICEF. Humanitarian Action for Children - Syrian Arab Republic [Internet]. unicef.org. 2017. https://www.unicef.org/appeals/syria.html . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Hossain SMM, Leidman E, King’ori J, Harun Al A, Bilukha OO. Nutritional situation among Syrian refugees hosted in Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon: cross sectional surveys. Confl Heal. 2016;10:26.

Mebrahtu S. The struggle to reach Syrian children with quality nutrition [Internet]. 2015. https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/syria_83147.html . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Nolan D. Children of Syria by the numbers [Internet]. 2016. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/children-of-syria-by-the-numbers/ . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Roberton T, Weiss W, The Jordan Health Access Study Team, The Lebanon Health Access Study Team, Doocy S. Challenges in estimating vaccine coverage in refugee and displaced populations: results from household surveys in Jordan and Lebanon. Vaccine. 2017;5:22.

Al-Moujahed A, Alahdab F, Abolaban H, Beletsky L. Polio in Syria: problem still not solved. Avicenna J Med. 2017;7:64–6.

Mbaeyi C, Ryan MJ, Smith P, Mahamud A, Farag N, Haithami S, et al. Response to a large polio outbreak in a setting of conflict — Middle East, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:227–31.

Sharara SL, Kanj SS. War and infectious diseases: challenges of the Syrian civil war. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004438.

Hassan G, Ventevogel P, Jefee-Bahloul H, Barkil-Oteo A, Kirmayer LJ. Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:129–41.

Sen K, Al-Faisal W, AlSaleh Y. Syria: effects of conflict and sanctions on public health. J Public Health (Oxf). 2013;35:195–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds090 .

Pani SC, Al-Sibai SA, Rao AS, Kazimoglu SN, Mosadomi HA. Parental perception of oral health-related quality of life of Syrian refugee children. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7:191–6.

Liu J. Syria: Unacceptable humanitarian failure [Internet]. 2015. http://www.msf.org/en/article/syria-unacceptable-humanitarian-failure . Accessed 31 Aug 2017.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Joint Masters Program in Health Policy and Law, University of California - California Western School of Law, San Diego, CA, USA

Rahma Aburas

Brotherhood Medical Center for Women and Children, Atimah, Syria

Amina Najeeb

Department of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, USA

Laila Baageel & Tim K. Mackey

Department of Medicine, Division of Global Public Health, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, USA

Tim K. Mackey

Global Health Policy Institute, San Diego, CA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

We note that with respect to author contributions, all authors jointly collected the data, designed the study, conducted the data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the formulation, drafting, completion, and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tim K. Mackey .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This community case study did not involve the direct participation of human subjects and did not include any personally identifiable health information. Hence, the study did not require ethics approval.

Competing interests

Amina Najeeb and Laila Baageel, two co-authors of this paper, were part of the foundation of the Center, remain active in its operation, and have a personal interest in the success of the operation of the clinic. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Aburas, R., Najeeb, A., Baageel, L. et al. The Syrian conflict: a case study of the challenges and acute need for medical humanitarian operations for women and children internally displaced persons. BMC Med 16 , 65 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1041-7

Download citation

Received : 05 September 2017

Accepted : 20 March 2018

Published : 11 May 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1041-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Maternal child health

- Syrian crisis

- Humanitarian health aid

- Internally displaced people

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Content Search

Syria + 8 more

Forced Migration Review Issue 57: Syrians in displacement

- Forced Migration Review

Attachments

Foreword: Syria in 2018 – in search of solutions

Noor Al Hussein

This important issue of Forced Migration Review draws our attention to the current challenges facing displaced Syrians and the continuing search for solutions. The statistics of Syrian displacement are staggering – and the numbers continue to rise. Half of Syria’s population has been displaced: five and a half million are registered refugees and over six million are internally displaced.

The tragedy of Syria’s conflict and the levels of displacement of its people reflect specific stresses and shortcomings in our region that often mirror similar global patterns. These stresses and shortcomings include the legacies of erratic modern political and economic governance that we cannot change but they are mostly triggered by issues that are fully within our control: inadequate and wavering political will; poor or absent host state responses to accommodating refugees in the short term; insufficient and uncoordinated humanitarian and development aid; continued internal stresses and violence that perpetuate displacement; and direct participation in warfare inside Syria by half a dozen foreign countries from within and beyond our region.

Many countries and organisations have offered assistance, yet we are also witnessing the world’s weariness and its inability to devise a coherent, effective response that could end the suffering of these millions of displaced people. Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey host the majority of Syrian refugees. They have opened their borders, schools and clinics, with the help of substantial international humanitarian assistance.

Many communities and individuals have welcomed and helped the newcomers. However, the arrival of refugees in lowincome and vulnerable communities also exacerbates existing problems and creates new tensions, notably regarding jobs, wages and overburdened infrastructure. Sadly, some host countries eventually reach a breaking point, and close their doors to new refugees. Donor and compassion fatigue lead to more restrictive reception and hosting policies within and beyond the Middle East, as fear, anger and even desperation assert themselves.

The traumas that displaced people experience are caused by the same underlying and persistent deficiencies, disparities and dysfunctions that create large-scale human marginalisation and vulnerabilities in some societies. If the underlying drivers of human indignity are not addressed, displacement will continue, with all the accompanying challenges.

Such lessons – including the reality that many displaced people will never return home – have long been debated.

Researchers, humanitarian agencies, local non-governmental organisations and host governments should now pursue a vital yet elusive strategy; it must merge temporary asylum and emergency humanitarian aid mechanisms with the longer-term promises of development and dignity that emanate from access to work and residency opportunities. Doing so will lift up both displaced people and host communities.

Refugees need protection and hosting until a durable solution is possible – which for those who choose to return must be under safe, voluntary and dignified conditions. We must generate the political will and international mobilisation that are needed in order to assist displaced people and host communities alike, and must also better resource the work of local humanitarian organisations helping displaced Syrians.

Recent initiatives such as the Global Compact for Migration and the Global Compact on Refugees offer the possibility of progress but can only succeed with significant support and commitments by governments. We must support displaced people to regain the chance to live fulfilling, dignified lives – to return home in peace, or to build a new life elsewhere that allows them and their neighbours to flourish together.

Her Majesty Queen Noor Al Hussein of Jordan

Related Content

Estado de la población mundial 2024: vidas entrelazadas, hilos de esperanza - eliminar las desigualdades enmateria de salud y derechos sexuales y reproductivos, état de la population mondiale 2024: destins entremêlés, lueurs d’espoir - mettre fin aux inégalités dans la santé et les droits sexuels et reproductifs, state of world population 2024: interwoven lives, threads of hope - ending inequalities in sexual and reproductive health and rights [en/ar/ru], the role of volunteers in leaving no one behind: supporting united nations entities and national governments towards realizing the 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Migration Studies

- Editorial Board

- Call for Papers

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. sample and measures, 3. findings, 4. discussion, supplementary data, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Migration aspirations in forced transnational families: the case of Syrians in Turkey

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David Schiefer, Franck Düvell, Ali Zafer Sağıroğlu, Migration aspirations in forced transnational families: the case of Syrians in Turkey, Migration Studies , Volume 11, Issue 3, September 2023, Pages 470–503, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnad020

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Increasingly high numbers of migrants around the globe have led migration scholars attempting to understand determinants of migration aspirations for many years. This study specifically looks at migration aspirations from two angles, (1) migration under conditions of a continuum of crises, in this case the (civil) war in Syria and precarious lives in Turkey, highlighting uncertainty and temporality entailed in crisis and (2) the role of family in migration aspirations. So far, scholarship primarily focuses on individuals in countries of origin and on voluntary migrants. Migration aspirations of forced migrants who have found refuge in another country are far less studied. Their situation, however, differs from voluntary migrants in distinct ways. Second, although the literature emphasizes the role of family for migration aspirations deep-level empirical inquiries are rare. Based on a survey among around 1,900 Syrian refugees in Turkey, this article addresses these gaps and explores the role family plays for migration aspirations among forced migrants. We take a close look by exploring how geographical family networks relate to migration aspirations and interact with other characteristics. We find that staying in Turkey seems to be the most likely option for participants at the time of the survey, but we also identify a substantial degree of uncertainty regarding migration aspirations. Furthermore, participants’ aspired places of living depend on the location of family members, above and beyond other characteristics. Moreover, (trans-)national family networks enhance or diminish effects of other determinants of migration aspirations such as perceived living conditions in Turkey.

Given the continuously increasing numbers of migrants and refugees around the globe (International Organization for Migration ( IOM) 2021 ), migration scholars have, for many years, been attempting to understand the drivers of individual migration aspirations (e.g. Aslany et al. 2021 ). Among others, family concerns have been identified as one important determinant (e.g. Cooke 2008 ). This article expands this research in two ways: First, most literature on migration aspirations focuses on individuals in countries of origin and on voluntary migration ( Czaika and Reinprecht 2022 ). This article adds a unique perspective to this work as it specifically investigates migration aspirations, first, in the context of a security crisis, a (civil) war, hence forced migration and second, by focusing on individuals and families who fled to a first safe country. Compared with other migrant groups, their legal status and living conditions are more strongly determined by precarity, temporality, and thus, uncertainty regarding the future. Second, despite the central role that theory has assigned to the family in the development of migration aspirations (e.g. Harbison 1981 ), studies rarely put the family at the center of their analyses. There is especially a lack of quantitative studies that attempt to disentangle how individual migration aspirations are linked to geographic-residential family patterns and how these are intertwined with other drivers of migration aspirations (e.g. perceived living conditions). This study expands this research by analyzing how (trans)national family networks drive migration aspirations above and beyond—and in interaction with—other determinants and whether and how these change over time.

This article is based on a survey among forced migrants from Syria in Turkey. In the following, we first introduce the topic of migration aspirations among forced migrants and how these are embedded in family considerations. We then outline the situation of Syrians in Turkey at the time of the survey. Subsequently, we introduce the study and present the findings, highlighting the uncertainty and temporality associated with desired future places of residence among the target group as well as the role of the (trans)national family networks for migration aspirations.

1.1 Migration aspirations in times of crisis

Migration aspiration is an umbrella term describing ‘cognitive and emotional orientations relating to future migration as a possibility in individuals’ lives’ ( Aslany et al. 2021 : 6). Migration aspirations are not equal to actual attempts or acts of migration ( Carling and Schewel 2018 ) but increase its likelihood (van Mol 2016). Intentions to move and intentions to stay are two components of migration aspirations that are not mutually exclusive and do not constitute clear-cut categories but rather a continuum, and there is a wide field of uncertainties and contingencies between the clear preference for or against migration ( Carling 2014 ; Schewel 2020 ). Migration aspirations evolve over time and can be repeatedly revisited depending on various factors ( Boccagni 2017 ). Scholars have discussed conditions and processes underlying individual migration aspirations on very different levels and from different theoretical perspectives, ranging from individual (e.g. demographic and socio-economic) determinants and individual cost–benefit considerations as an underlying process, to the role of social networks, of macrosocial factors such as economic development, and to approaches viewing migration as socially and culturally embedded projects (for reviews see e.g. Carling and Schewel 2018 ; Aslany et al. 2021 ).

Migration scholars generally assume that migration aspirations emerge as a result of individual consideration and evaluation processes. Benefits and costs of migration or staying are weighed against one’s own or one’s family’s needs, life goals, well-being, experiences, imaginations and perceptions, social expectations, or contextual circumstances (e.g. Timmerman, Heyse and Van Mol 2010 ). However, in cases of crisis, such as violent conflicts, matters are more complex. Regarding migration aspirations, at least three aspects account for differences between crisis and non-crisis contexts ( Voss and Lorenz 2016 ). The first is threat: Social upheaval or political and military conflicts intrude into people’s everyday lives, impair habitual patterns, and pose existential threats to economic, social, and physical security, thus causes the affected population to take drastic protective measures, of which fleeing is one possible option ( Rosenthal, Boin and Comfort 2001 ; Voss and Lorenz 2016 ). The second is constrained agency: Refugees still have agency (staying or fleeing, when and where to flee) (e.g. Turton 2003 ), and in the case of fleeing, migration aspirations are still driven by imaginations, perceptions, and corresponding evaluations of different places. However, the ability to make free, informed, and well-planned decisions whether to stay, return, or move on is strongly constrained. The need to move arises regardless of pre-crisis migration aspirations, thus, the ability to prepare (taking language courses, find a job, etc.) is reduced. Third, before the initial fleeing but also once arrived in a seemingly safe place, (further) migration decisions have to be made under high levels of uncertainty. The development of a crisis is often unpredictable; onward migration often involves high costs and legal barriers and imaginations of current and future places of living are often vague (e.g. Biehl 2015) . Developing an attitude toward migration, however, requires to a certain extent assessing one’s capabilities of migrating, potential outcomes of migration, their likelihood, and the value of these outcomes ( Willekens 2017) . Uncertainty undermines all these assessments ( Quintal, Lee and Soutar 2010 ). Taken together, forced migrants need to appraise the options of staying, returning, or moving on based on what seems possible and necessary in the current situation (see e.g. Robinson and Segrott 2002 ; Akesson and Coupland 2018 ; Müller-Funk et al. 2019 ; Borselli and Meijl 2021 ). As we will demonstrate in the subsequent sections of this article, sometimes staying put is the currently best choice and positions vis-á -vis return or onward migration are clearly more ambivalent.

1.2 Temporality of migration aspirations in times of crisis

Migration aspirations of forced migrants, accordingly, are subject to a high degree of temporality. Contextual conditions (e.g. the development of conflicts) can change unexpectedly, conditions in the first safe place can change and experiences made or new information received over time may instigate aspirations to migrate onward. Adverse conditions can accumulate over time until a certain tipping point is reached at which moving on constitutes the most feasible option ( Czaika and Reinprecht 2022 ). Moreover, initial migration decisions may be more strongly based on essential and immediate needs such as security or health, and more long-term considerations, such as educational opportunities, legal rights, or cultural similarity come to the fore over time once some kind of planning ahead is possible. Thus, migration aspirations, before and after initial fleeing, are dynamic and constantly revised over time (for further reading see, Robinson and Segrott 2002 ; Boccagni 2017 ; Akesson and Coupland 2018 ; Müller-Funk 2019 ; Müller-Funk et al. 2019 ; Borselli and Meijl 2021 ; Rottman and Kaya 2021 ).

1.3 Family networks as drivers of migration aspirations in times of crisis

Family is an important determinant of migration aspirations. Migration scholars have shown that migration aspirations often do not simply emerge on the individual level but rather on the collective level of a family: This is because it is not simply individual benefit that is at the core of migration decisions but the benefit of the household, that is, the family ( Boyd 1989 ; Stark 1991 ; Cooke 2008 ; Haug 2008 ). Family is the social background against which individual’s make migration decisions and thus serves as the link between macro-level contextual (e.g. economic) realities and micro-level individual cognitions ( Harbison 1981 ; Coleman 1986) . Furthermore, social network and transnationalism approaches view migration aspirations as determined by the geographical location of family members. Family members are among the most important social relations in people’s lives (e.g. in terms of social support and affection), thus, their places of residence can facilitate or hamper migration aspirations depending on the resources, opportunities, social capital, and obligations that these social ties entail (e.g. Massey et al. 1987 ; Boyd 1989 ; Kok 2010 ; Mulder 2018 ). Accordingly, in the process of migration decision making, individual and family-related considerations are strongly intertwined and far from straight-forward. Having children, for example, can be a reason to leave (e.g. to provide them with better education) but also a reason to stay (e.g. to prevent them from harm caused by migration).

Given that family is both a central source and recipient of care and support in human’s lives (e.g. Harrell 1997 ), its importance for migration aspirations in times of crises can be assumed to be as strong as, or even stronger compared with non-crisis contexts. Crisis poses a threat to peoples’ security, well-being, and future and in such times family members can provide or also be in particular need of support and care (e.g. Robinson and Segrott 2002 ). Therefore, their place of residence potentially is a particularly strong driver of decisions to stay, move on, or return ( Akesson and Coupland 2018 ; Borselli and Meijl 2021 ). In the case of forced migration, some peculiarities are added. One is that family members are often involuntarily physically separated across different localities (see Koç and Saraç 2020 ) driving desires to reunite. Furthermore, onward migration of single family members with the expectation to later arrange family reunification has been identified a survival strategy of families ( Dubow and Kutschminder 2021 ). Where relatives live can influence migration aspirations in different directions. Transnational relationships may thus facilitate onward migration (e.g. via legal family reunification) but may as well be a source of remittances, thereby improve living situation locally and thus enable relatives to remain in their places of residence (e.g. Şimşek 2019 ). In this regard, family networks and migration aspirations are mutually dependent and intertwined in complex ways especially in times of crises. Understanding these complexities requires to investigate residential family patterns and their relations to migration aspirations in depth.

1.4 The interplay of family and other drivers of migration aspirations

Family, of course, is not the only driver of migration aspirations. Many other factors play a role, such as the living conditions in the place of residence and the perceptions thereof, individual characteristics (age, gender, health, life aspirations, etc.), or transnational networks beyond family ( Aslany et al. 2021 ). These drivers, however, can be assumed to interact with family networks. For example, intentions to stay might be especially high when living conditions are good and family members live nearby. In contrast, good living conditions might not increase intentions to stay if families are separated across countries. Sometimes a person might benefit from migration (e.g. educational opportunities) but on the expenses of family members in need of care that would have to be left behind. Qualitative interviews with Syrians in Turkey show, for example, that decisions to migrate onward for better living conditions partly depend on encouragement or disapproval by parents ( Müller-Funk 2019 ) and that adverse living conditions (e.g. lacking educational opportunities) translate into the wish to move on especially with regard to the future of the children ( Üstübici, Kirişçioğlu and Elçi 2021 ). Thus, family and other drivers of migration aspirations do not simply add up but are intertwined, weighed against each other and jointly feed into individuals’ migration-related evaluations. Whereas qualitative studies highlight such dynamics, quantitative studies tend to analyze different drivers of migration aspirations separately without considering their potential interaction. This article utilizes our quantitative data to zoom deeper into such interactions.

1.5 The situation of Syrians in Turkey

The current situation of Syrians is determined by multiple crises or rather a continuum of crisis. This dates back to 2011 when an unviable human rights situation inspired an uprising, that was brutally suppressed which led to a civil war drawing in more and more regional and external actors. This amounted to a crisis of war and a subsequent humanitarian crisis. The consequence was large-scale displacement and a refugee crisis as millions fled to neighboring countries. There, in turn, a reception crisis unfolded as initially people were sleeping rough with few means of survival. Over time, reception conditions improved; however, in Turkey and other countries the refugees’ status remained precarious ( Düvell 2018) . Notably in Turkey, Syrian refugees were hit particularly hard by an economic crisis and in 2020 the health crisis, that is, the pandemic ( Düvell 2020) . Meanwhile, the initially hospitable reception of Syrians by Turkish policy and society has become increasingly hostile (e.g. Erdogan 2019 ). Political controversy, mounting incidences of racial violence ( The New Arab 2022 ) and the threat of forcefully returning 1 million Syrians ( Aljazeera 2022 ) represent yet another critical moment.

Although statistics are somewhat inconsistent, an estimated number of at least 4 million Syrians fled to Turkey of whom 3–3.6 million, so official numbers, are still in the country ( Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) 2022 ). Turkey hosts the largest number of refugees worldwide ( Düvell 2019 ; World Bank 2019 ). Around 1 million moved on to the European Union (EU) or other regions of the world (e.g. Erdogan 2019 ), mainly in 2015 and 2016, whereas only a rather small number returned to Syria ( World Bank 2019 ). Yet, the majority of the Syrian refugee population in Turkey remained in the country. Until winter 2015, Turkey pursued an open-door policy toward Syrians granting them temporary protection. However, in March 2016, EU and Turkey issued a joined statement, which in essence is aiming to contain Syrian refugees in Turkey and prevent further onward migration. In addition, Turkey constructed a wall along its southern border to stop further inflows from Syria. As a result, both the migration flows of Syrians into Turkey and from Turkey to Europe have strongly decreased.

Other than those in the EU, Syrians in Turkey are not recognized as refugees but granted only temporary protection by the Turkish government. Although having signed the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention, Turkey limits its legal responsibility to asylum seekers from European countries (Biel 2015). The Asylum regime has been described as being very restrictive and unpredictable with regard to its outcome, leaving asylum seekers from third countries in a state of protracted uncertainty (Biel 2015). Syrians under temporary protection are granted access to some but excluded from other rights. While they have access to education and health care, their regional settlement is regulated and they have almost no legal access to the labor market ( Düvell 2018 ). The EU and individual member states support Turkey financially and practically to accommodate and integrate Syrians. However, the Syrian refugee situation remains precarious ( Baban, Ilcan and Rygiel 2017 ).

Accordingly, from 2016, Turkey was primarily a destination country for Syrians ( Düvell 2018 ; Müller-Funk 2019 ; Rottman and Kaya 2021 ) so that Syrians were or have been turned into an internationally immobile population. Those who entered Turkey with the intention to move to the EU have largely done so before 2016 ( UNHCR 2023) . Recent studies among Syrians in Turkey suggest that those who were still living in Turkey after 2016 either did not manage to migrate onward despite aspirations or deliberately decided to stay in Turkey. The majority perceives staying in Turkey as the currently most likely option. Returning to Syria is a strong desire, yet, viewed as rather unrealistic, and only a minority considers moving on as a desirable and realistic option (see Akesson and Coupland 2018 ; Müller-Funk 2019 ; Erdogan 2020 ; Üstübici, Kirişçioğlu and Elçi 2021 ). Following the framework suggested by Schewel (2020) , they thus represent a group characterized by either involuntary (aspiration but no capability to migrate) or acquiescent immobility (neither aspiration nor capability).

These studies also hint to uncertainties and dependencies involved in these considerations. Responses to survey questions about migration aspirations strongly vary depending on which conditional context (e.g. provision of papers, end of war) is presented, indicating the lack of clear imaginations with regard to future options. Furthermore, studies provide evidence that family concerns had played a central role in migration considerations among Syrians ever since the war began in 2011. Many families have been separated and scattered across multiple countries ( Koç and Saraç 2020 ). Aspirations to leave Syria or neighboring countries and move on to other places such as Europe have been affected by considerations with regard to their family’s future and well-being, by the desire for family reunification, and by transnational family networks. Staying close to one another, but also joint migration or even deliberate separation have been described as strategies to maintain the family’s well-being among Syrians ( Akesson and Coupland 2018 ; Müller-Funk 2019 ; Şimşek 2019 ; Borselli and Meijl 2021 ; Üstübici, Kirişçioğlu and Elçi 2021 ; Dubow and Kutchminder 2021 ; Tobin, Momani and Al Yakoub 2022 ). Thus, based on these studies it can be assumed that, despite being relatively immobile, migration aspirations of Syrians in Turkey after 2016, that is, whether to stay, leave, or return, have been still largely driven by family concerns.

This importance of family for migration aspirations is underscored by the high importance of family in Syrian society. Though family systems in Syria are rather diverse ( Rabo 2008 ), the family is described as the dominant institution in Syria with regard to support and security but also religious and cultural belonging ( Tobin, Momani and Al Yakoub 2022 ). Generally, family cohesion is strong and individual needs and aspirations are subordinated to (extended) family needs and obligations ( Haboush 2005 ). However, as Tobin, Momani and Al Yakoub (2022) point out, as a consequence of protracted separation, proximate family networks (e.g. within the country of destination) are more likely to represent social capital than more distant ones and thus also tend to play a stronger role for (im)mobility aspirations.

1.6 Research question and assumption

Based on the review of migration aspirations in times of crises, the role of family for migration aspirations, and the situation of Syrians in Turkey as provided so far, this study zooms into the role of family for migration aspirations under crisis conditions. Our empirical base is a survey among 1,886 Syrian individuals in six provinces across Turkey. Our analyses differ from existing studies in two ways: First, we take a case of migration under crisis conditions, whereas most migration aspiration studies focus on relatively voluntary migration. Second, we provide a deeper insight into (trans)national family networks and illustrate how these relate to migration aspirations over and above—and in interaction with—other determinants such as actual and perceived living conditions. Our analyses are guided by the following hypotheses:

We assumed that in 2018 the majority of Syrians in Turkey did not aspire to move back to Syria due to the security situation. We also assumed that only a minority held onward migration aspirations because most who wanted to move to Europe had already done so in 2015–6 while the majority aspires staying in Turkey.

Apart from this expected pattern of migration aspirations, we assumed that in 2018 Syrians in Turkey were highly uncertain regarding their future places of living. Given the unpredictable political situation in Syria, this uncertainty especially regarded to return aspirations. However, it also regarded to aspirations of staying, given the often precarious living conditions and increasingly hostile environments Syrians face in Turkey.

We furthermore expected that migration aspirations display some temporal dynamics. With increasing duration of the conflict in Syria and of settlement in Turkey, Syrian refugees’ further migration aspirations changed as did their reasons.

Family networks (i.e. family members’ place of residence) are assumed to relate to migration aspirations, above and beyond other individual and contextual characteristics. We hypothesized that having relatives in Turkey enhances intentions to stay whereas having relatives in Syria or another country nurtures aspirations to return or move on, respectively.

Finally, we expected that family members’ places of residence interact with other characteristics in their relation to migration aspirations in a mutually enforcing or inhibiting way.

The survey was conducted between November 2018 and May 2019. Due to scarce information about the Syrian population in Turkey (official statistics only provide numbers per gender and age groups on the level of provinces; see DGMM 2018 ), restricted access to address databases, and budgetary constraints it was not possible to draw a representative random sample. In order to still acquire a sample allowing us to draw conclusions about the Syrian population in Turkey, we developed a multi-stage-sampling approach combining different sampling techniques. Details of the procedure can be found in Schiefer et al. (2023) . In a nutshell, we first selected all provinces with a high share of Syrian refugees (at least 80,0000 registrations). These 13 (out of 81) provinces covered more than 80 per cent of the target group in Turkey. Among these provinces, we made a theoretically driven yet pragmatic preselection of six provinces, based on their geographic location (proximity to the Syrian border, proximity to the EU and Central Anatolia), high numbers of Syrians, and different economic opportunities. By the time of data collection, these six provinces hosted approximately 2 million or 57 per cent of Syrian refugees in Turkey ( DGMM 2018 ). Within these six provinces we chose 9 towns, and within these towns altogether 23 districts where Syrians were known to be concentrated. We also made sure that the districts represent different social classes, Syrians of different mother tongues, and different locations within the towns (central vs. peripheral). Because no official statistics on the local distribution of Syrian are available, we consulted local experts and other sources such as newspaper reports. Within the districts, households were randomly selected via random walks.

Table 1 documents sample characteristics. A comparison with official statistics and other surveys among Syrians in Turkey conducted under similar conditions at around the same time shows that, overall, the sample resembles the target group very well (see Schiefer et al. (2023) for details). Participants’ ages ranged between 18 and 87 years with an average age of 35.6 years. This age distribution is comparable to the official statistics ( DGMM 2018 ) and to other surveys (e.g. IOM 2018 ; Erdogan 2020 ). Fifty-nine per cent of the sample are female, a proportion that is higher than in the official statistics and other surveys. Around two-thirds of the participants stated having received a primary or middle school education, around 20 per cent stated higher levels, and around 12 per cent stated having no school degree. Our comparison with other studies reveals that one survey comprised more participants with a lower level of education ( TRC—Turkish Red Crescent and WFP—World Food Program 2019 ), another one surveyed comparably higher educated individuals ( Erdogan 2019 , 2020 ). The peak of participants’ arrivals in Turkey was between 2012 and 2016, around 88 per cent arrived during that time; hence at the time of the interview, most had been residing in Turkey for two to six years.

Sample characteristics

Note : Unweighted data.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of all survey questions that were included in the analyses for this article. They comprise individual migration aspirations, family networks, living conditions in Turkey, and sociodemographic- and migration-related information. Aspirations to stay, return, or move on were asked with separate questions. The respective response categories were presented to the participants as shown in the table. The main analyses of this article focus on individual migration aspirations. In some cases, additional analyses were conducted with regard to family-related aspirations (‘Where would your family be better off?’) for comparative reasons. Due to constraints regarding the length of the interviews, family networks in Europe could not be assessed separately by types of relatives. Perceived living conditions in Turkey and Europe are captured by mean scores based on seven questions referring to different live domains (e.g. health system, accommodation, rights for refugees). The two scales showed a good reliability (Crohnbach’s α 0. 79 and 0.93, respectively).

Descriptive statistics of variables used for the analyses

Data are weighted to correct for the unequal distribution of the Syrian population across the included provinces in Turkey.

Percentage of participants having either little, moderate, or good knowledge of Turkish.

Response scales from 1 to 7 were categorized into low (scale mean 1 to ≤4) and high (scale mean >4 to 7).

Averaged across seven items.

Missing information due to incorrect assessment by interviewers.

The descriptive statistics in Table 2 as well as those in Section 3 (except for the regression analyses) are based on weighted data. A weight seemed reasonable because the Syrian population is unequally distributed across the six provinces covered by the study sample, whereas our sub-samples of each province are rather similar in size (around 300 participants per province). For example, the 315 participants from Istanbul represent around 560,000 Syrians registered in Istanbul, whereas the 297 participants from Ankara represent only around 90,000 ( DGMM 2018 ). The sub-samples of each province thus represent different numbers of Syrians. The weight corrects for these unequal ratios. It was computed as the inverse of the inclusion probabilities within provinces. That way, the sample represents the overall Syrian population in the six provinces more accurately. More details on the weight construction can be found in Schiefer et al. (2023) . Note, however, that the weighting procedure involves some uncertainties: The plausibility of official numbers on Syrians in Turkish provinces has been questioned ( Düvell 2019 ). Furthermore, the weight corrects only for population distributions within the six provinces, not within Turkey as a whole. Moreover, the assumption of a random probability selection, on which weighting approaches are commonly based, holds primarily for the household level (random walks) but less so for the city and district level (see Schiefer et al. (2023) for details).

As Table 2 documents, the questions ‘In the future, would you like to live in a country other than Turkey or Syria?’ and ‘In the future, would you like to stay in Turkey?’ did not offer a response option ‘I don’t know’. Furthermore, the question about aspirations to stay had a relatively large non-response rate (11.1 per cent), and also the question asking for onward migration had a small non-response rate (2.8 per cent). As shown in Section 3, we treat this non-response as an indicator of uncertainty regarding aspirations to stay in Turkey or move on and use them as dependent variables in regression analyses. We do this acknowledging that in our sample non-response can be interpreted as uncertainty, but in principle also as an act of concealment (refusal of response), especially since for Syrians in Turkey onward migration to Western countries is in most cases only possible through irregular channels and respective information thus are sensitive. To better understand the meaning of non-response to these questions, we compared whether respondents and non-respondents differed in their responses to other, potentially sensitive questions such as whether they had ever tried to get to Europe by means other than legal visa, whether they had received help from others when migrating to Turkey or whether they still have monetary savings. Some of these questions also include a response option ‘Prefer not to say’. Results, documented in Supplementary Appendix 1 , do not indicate substantial bias, but nevertheless do not completely rule out that non-response is a matter of concealment. However, the results of the regression analyses (see Section 3) again suggest that non-response is likely an expression of uncertainty.

3.1 Migration aspirations of Syrians in Turkey in 2018: Judgments in times of uncertainty

More than half of the participants confirmed that they would like to stay in Turkey in the future ( Table 2 ). In turn, 29 per cent expressed intentions to live in a country other than Turkey or Syria in the future. Notably, less than 2 per cent confirmed having enough money to travel to Europe indicating very low migration capabilities. Regarding return to Syria, participants appeared to be rather uncertain. Only 3 per cent agreed with this option, around 20 per cent disagreed, and the vast majority chose the response option ‘depending on the situation’ (63 per cent) or ‘I don’t know’ (14 per cent). When being asked about where their family would be better off, the majority of the participants, 57 per cent, chose Turkey. This is even slightly more than those who state that they want to stay in Turkey in the future. In comparison, 21 per cent expect their family to be better off in Syria and around 24 per cent say this would be in Europe.

The responses concerning the return to Syria illustrate the high degree of uncertainty with regard to the further development of the crisis and the future places of living. This is corroborated by the high rates of non-response to the question about living in Turkey in the future (11 per cent, Table 2 , see Section 2 for the interpretation of non-response) and to the questions about living conditions in Europe (47 per cent, Table 2 ). The latter indicates that imaginations of places outside of Turkey or Syria are vague, some participants explained that they knew too little about Europe.

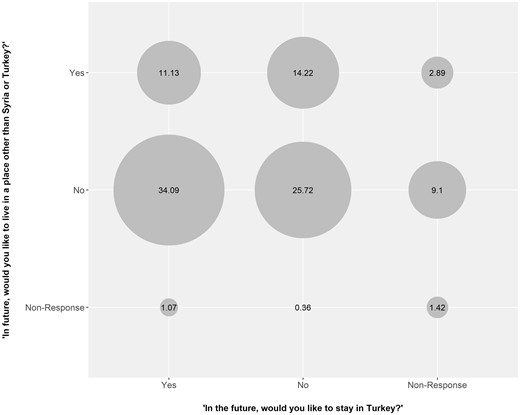

Uncertainty is also reflected in the fact that 39 per cent of participants who answered positively to the question about moving on to places other than Syria or Turkey also answered positively to the question about staying in Turkey. Vice versa, 24 per cent of those who stated aspirations to stay in Turkey also stated aspirations to move on to other places. In the total sample, this makes 11 per cent of the participants who simultaneously consider both to stay and to move on ( Fig. 1 ), indicating a lack of clear preferences. Another 9 per cent of the total sample stated that they do not aspire to move on, but were uncertain (non-response) with regard to staying. In this regard, the various migration options are not a zero-sum game for Syrians in Turkey. Moreover, for around 26 per cent of participants neither staying nor moving on seemed to be an option ( Fig. 1 ). Within this group, in turn, 85 per cent made their return to Syria dependent on the situation there. This, again, demonstrates the high degree of uncertainty regarding desired places of living.

Responses to the questions asking for aspirations to stay in Turkey and aspirations to move on. Weighted data. Numbers represent percentages of the total sample.

Taken together, the majority of participants saw themselves in Turkey in the future; only a (still large) minority of the participants seemed to be convinced that moving on to other places such as Europe is a desirable option. This depicts best their response to the crisis and Syria: to stay away from it. Only a minority perceives Syria as a desirable place, and whether living in Syria in the future is a realistic option is rather unpredictable. Simultaneously under conditions of a security crisis, people are often rather uncertain about their future whereabouts and sometimes multiple options are considered.

3.2 Temporality

Our data also illustrate the temporality inherent in migration aspirations in times of crisis. For example, safety was a predominant reason to choose Turkey as a country of destination (53 per cent, Table 2 ). Other aspects, such as rights of refugees (16.3 per cent), the presence of relatives in Turkey (16.3 per cent) and job opportunities (14.7 per cent) played a lesser role. In contrast, among those who expressed the intention to move on to another country only 26 per cent selected peace as one of the three most important reasons. Instead, they more often chose human rights (55 per cent), job opportunities (31.8 per cent), and the presence of family (25 per cent) as reasons. Although comparability is reduced here due to different wording of questions and different response options, these variations point to the temporal dynamics in migration aspirations: Over time, immediate needs such as security are replaced by more long-term needs such as rights, economic opportunities, and family networks.

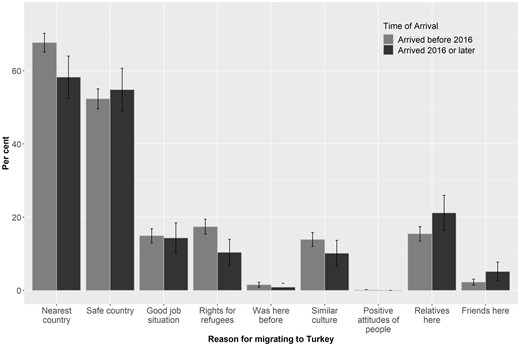

Furthermore, respondents’ migration aspirations partly differ depending on the time they arrived in Turkey; another illustration of temporality. Using 2016 (the year of the EU–Turkey statement) as a cutoff, we find that participants who arrived in Turkey in the early years of the war mentioned geographic proximity, cultural similarity, and rights for refugees significantly more often as reasons for coming to Turkey compared with those who arrived later (proximity: χ 2 = 13.3, p < 0.01; similarity: χ 2 = 4.4, p < 0.05; rights: χ 2 = 6.4, p < 0.05). In contrast, family and friendship networks were significantly more important among those who arrived later (family: χ 2 = 12.5, p < 0.01; friends: χ 2 = 3.9, p < 0.05; Fig. 2 ) . Furthermore, aspirations to move onward are significantly higher among early than late arrivers (24% vs. 30%, χ 2 = 5.4, p < 0.05). Aspirations to stay and to return are, however, unrelated to the time of arrival. One assumption here is that those who arrived later chose Turkey more deliberately as a destination, for example, for family reasons, therefore onward migration is less attractive for them. Notably, human and refugee rights seemed to play a somewhat lesser role for later arrivals in Turkey and are more likely to be a reason for onward migration.

Reasons for coming to Turkey, by time of arrival. Weighted data. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

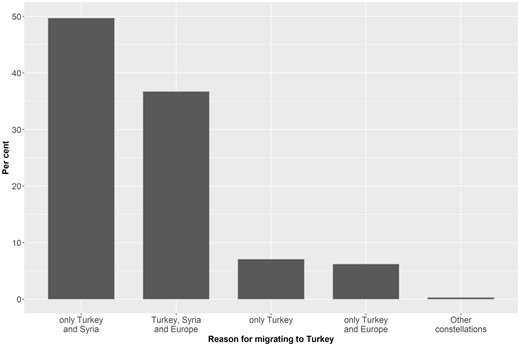

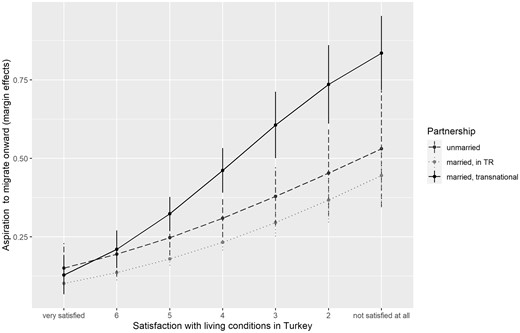

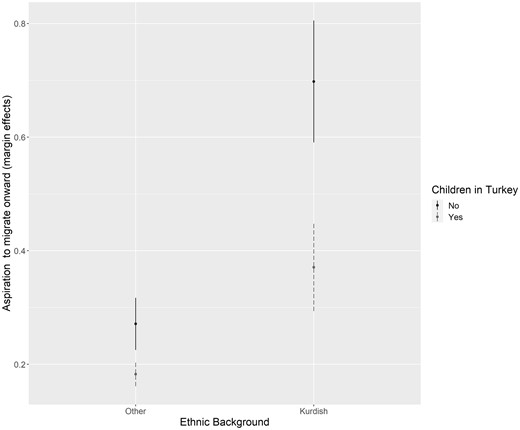

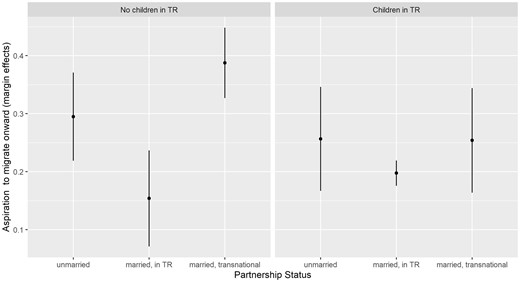

3.3 Migration aspirations: the role of family