How To Write Significance of the Study (With Examples)

Whether you’re writing a research paper or thesis, a portion called Significance of the Study ensures your readers understand the impact of your work. Learn how to effectively write this vital part of your research paper or thesis through our detailed steps, guidelines, and examples.

Related: How to Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research

Table of Contents

What is the significance of the study.

The Significance of the Study presents the importance of your research. It allows you to prove the study’s impact on your field of research, the new knowledge it contributes, and the people who will benefit from it.

Related: How To Write Scope and Delimitation of a Research Paper (With Examples)

Where Should I Put the Significance of the Study?

The Significance of the Study is part of the first chapter or the Introduction. It comes after the research’s rationale, problem statement, and hypothesis.

Related: How to Make Conceptual Framework (with Examples and Templates)

Why Should I Include the Significance of the Study?

The purpose of the Significance of the Study is to give you space to explain to your readers how exactly your research will be contributing to the literature of the field you are studying 1 . It’s where you explain why your research is worth conducting and its significance to the community, the people, and various institutions.

How To Write Significance of the Study: 5 Steps

Below are the steps and guidelines for writing your research’s Significance of the Study.

1. Use Your Research Problem as a Starting Point

Your problem statement can provide clues to your research study’s outcome and who will benefit from it 2 .

Ask yourself, “How will the answers to my research problem be beneficial?”. In this manner, you will know how valuable it is to conduct your study.

Let’s say your research problem is “What is the level of effectiveness of the lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) in lowering the blood glucose level of Swiss mice (Mus musculus)?”

Discovering a positive correlation between the use of lemongrass and lower blood glucose level may lead to the following results:

- Increased public understanding of the plant’s medical properties;

- Higher appreciation of the importance of lemongrass by the community;

- Adoption of lemongrass tea as a cheap, readily available, and natural remedy to lower their blood glucose level.

Once you’ve zeroed in on the general benefits of your study, it’s time to break it down into specific beneficiaries.

2. State How Your Research Will Contribute to the Existing Literature in the Field

Think of the things that were not explored by previous studies. Then, write how your research tackles those unexplored areas. Through this, you can convince your readers that you are studying something new and adding value to the field.

3. Explain How Your Research Will Benefit Society

In this part, tell how your research will impact society. Think of how the results of your study will change something in your community.

For example, in the study about using lemongrass tea to lower blood glucose levels, you may indicate that through your research, the community will realize the significance of lemongrass and other herbal plants. As a result, the community will be encouraged to promote the cultivation and use of medicinal plants.

4. Mention the Specific Persons or Institutions Who Will Benefit From Your Study

Using the same example above, you may indicate that this research’s results will benefit those seeking an alternative supplement to prevent high blood glucose levels.

5. Indicate How Your Study May Help Future Studies in the Field

You must also specifically indicate how your research will be part of the literature of your field and how it will benefit future researchers. In our example above, you may indicate that through the data and analysis your research will provide, future researchers may explore other capabilities of herbal plants in preventing different diseases.

Tips and Warnings

- Think ahead . By visualizing your study in its complete form, it will be easier for you to connect the dots and identify the beneficiaries of your research.

- Write concisely. Make it straightforward, clear, and easy to understand so that the readers will appreciate the benefits of your research. Avoid making it too long and wordy.

- Go from general to specific . Like an inverted pyramid, you start from above by discussing the general contribution of your study and become more specific as you go along. For instance, if your research is about the effect of remote learning setup on the mental health of college students of a specific university , you may start by discussing the benefits of the research to society, to the educational institution, to the learning facilitators, and finally, to the students.

- Seek help . For example, you may ask your research adviser for insights on how your research may contribute to the existing literature. If you ask the right questions, your research adviser can point you in the right direction.

- Revise, revise, revise. Be ready to apply necessary changes to your research on the fly. Unexpected things require adaptability, whether it’s the respondents or variables involved in your study. There’s always room for improvement, so never assume your work is done until you have reached the finish line.

Significance of the Study Examples

This section presents examples of the Significance of the Study using the steps and guidelines presented above.

Example 1: STEM-Related Research

Research Topic: Level of Effectiveness of the Lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ) Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice ( Mus musculus ).

Significance of the Study .

This research will provide new insights into the medicinal benefit of lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ), specifically on its hypoglycemic ability.

Through this research, the community will further realize promoting medicinal plants, especially lemongrass, as a preventive measure against various diseases. People and medical institutions may also consider lemongrass tea as an alternative supplement against hyperglycemia.

Moreover, the analysis presented in this study will convey valuable information for future research exploring the medicinal benefits of lemongrass and other medicinal plants.

Example 2: Business and Management-Related Research

Research Topic: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Social Media Marketing of Small Clothing Enterprises.

Significance of the Study:

By comparing the two marketing strategies presented by this research, there will be an expansion on the current understanding of the firms on these marketing strategies in terms of cost, acceptability, and sustainability. This study presents these marketing strategies for small clothing enterprises, giving them insights into which method is more appropriate and valuable for them.

Specifically, this research will benefit start-up clothing enterprises in deciding which marketing strategy they should employ. Long-time clothing enterprises may also consider the result of this research to review their current marketing strategy.

Furthermore, a detailed presentation on the comparison of the marketing strategies involved in this research may serve as a tool for further studies to innovate the current method employed in the clothing Industry.

Example 3: Social Science -Related Research.

Research Topic: Divide Et Impera : An Overview of How the Divide-and-Conquer Strategy Prevailed on Philippine Political History.

Significance of the Study :

Through the comprehensive exploration of this study on Philippine political history, the influence of the Divide et Impera, or political decentralization, on the political discernment across the history of the Philippines will be unraveled, emphasized, and scrutinized. Moreover, this research will elucidate how this principle prevailed until the current political theatre of the Philippines.

In this regard, this study will give awareness to society on how this principle might affect the current political context. Moreover, through the analysis made by this study, political entities and institutions will have a new approach to how to deal with this principle by learning about its influence in the past.

In addition, the overview presented in this research will push for new paradigms, which will be helpful for future discussion of the Divide et Impera principle and may lead to a more in-depth analysis.

Example 4: Humanities-Related Research

Research Topic: Effectiveness of Meditation on Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students.

Significance of the Study:

This research will provide new perspectives in approaching anxiety issues of college students through meditation.

Specifically, this research will benefit the following:

Community – this study spreads awareness on recognizing anxiety as a mental health concern and how meditation can be a valuable approach to alleviating it.

Academic Institutions and Administrators – through this research, educational institutions and administrators may promote programs and advocacies regarding meditation to help students deal with their anxiety issues.

Mental health advocates – the result of this research will provide valuable information for the advocates to further their campaign on spreading awareness on dealing with various mental health issues, including anxiety, and how to stop stigmatizing those with mental health disorders.

Parents – this research may convince parents to consider programs involving meditation that may help the students deal with their anxiety issues.

Students will benefit directly from this research as its findings may encourage them to consider meditation to lower anxiety levels.

Future researchers – this study covers information involving meditation as an approach to reducing anxiety levels. Thus, the result of this study can be used for future discussions on the capabilities of meditation in alleviating other mental health concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is the difference between the significance of the study and the rationale of the study.

Both aim to justify the conduct of the research. However, the Significance of the Study focuses on the specific benefits of your research in the field, society, and various people and institutions. On the other hand, the Rationale of the Study gives context on why the researcher initiated the conduct of the study.

Let’s take the research about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Levels of College Students as an example. Suppose you are writing about the Significance of the Study. In that case, you must explain how your research will help society, the academic institution, and students deal with anxiety issues through meditation. Meanwhile, for the Rationale of the Study, you may state that due to the prevalence of anxiety attacks among college students, you’ve decided to make it the focal point of your research work.

2. What is the difference between Justification and the Significance of the Study?

In Justification, you express the logical reasoning behind the conduct of the study. On the other hand, the Significance of the Study aims to present to your readers the specific benefits your research will contribute to the field you are studying, community, people, and institutions.

Suppose again that your research is about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students. Suppose you are writing the Significance of the Study. In that case, you may state that your research will provide new insights and evidence regarding meditation’s ability to reduce college students’ anxiety levels. Meanwhile, you may note in the Justification that studies are saying how people used meditation in dealing with their mental health concerns. You may also indicate how meditation is a feasible approach to managing anxiety using the analysis presented by previous literature.

3. How should I start my research’s Significance of the Study section?

– This research will contribute… – The findings of this research… – This study aims to… – This study will provide… – Through the analysis presented in this study… – This study will benefit…

Moreover, you may start the Significance of the Study by elaborating on the contribution of your research in the field you are studying.

4. What is the difference between the Purpose of the Study and the Significance of the Study?

The Purpose of the Study focuses on why your research was conducted, while the Significance of the Study tells how the results of your research will benefit anyone.

Suppose your research is about the Effectiveness of Lemongrass Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice . You may include in your Significance of the Study that the research results will provide new information and analysis on the medical ability of lemongrass to solve hyperglycemia. Meanwhile, you may include in your Purpose of the Study that your research wants to provide a cheaper and natural way to lower blood glucose levels since commercial supplements are expensive.

5. What is the Significance of the Study in Tagalog?

In Filipino research, the Significance of the Study is referred to as Kahalagahan ng Pag-aaral.

- Draft your Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from http://dissertationedd.usc.edu/draft-your-significance-of-the-study.html

- Regoniel, P. (2015). Two Tips on How to Write the Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from https://simplyeducate.me/2015/02/09/significance-of-the-study/

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Last Updated May 6, 2023 10:29 AM

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Scope and Delimitation & Benefits and Beneficiaries of Research

2020, Division of Palawan

This module was designed and written with you in mind. It is here to help you master the Scope and Delimitation and Benefits and Beneficiaries of Research. The scope of this module permits it to be used in many different learning situations. The language used recognizes the diverse vocabulary level of students. The lessons are arranged to follow the standard sequence of the course. But the order in which you read them can be changed to correspond with the textbook you are now using. The module is divided into Two (2) lessons, namely: Lesson 1- Scope and Delimitation of research Lesson 2- Benefits and Beneficiaries of research After going through this module, you are expected to: a. define scope and delimitation of research; b. appreciate the scope, limitation and delimitation; and, c. write the benefits and beneficiaries of research.

Related Papers

Asfarasin Maricar

mabuta mustafa

lecture notes

md. faruk miah

Michael Evans

Farhan Ahmad

mahrukh fatima

For Students, Scholars, Researchers, Investigators, Trainees and Scientists. “If I have seen a little further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” Isaac Newton. This book on research is an attempt to try to answer the basic fundamental questions that come to the minds of young students, researchers, scholars, investigators, trainees or scientists. It is an outcome of collaboration between 43 researchers from 11 different countries (Pakistan, India, United States, Iran, United Kingdom, Nepal, Canada, Greece, Poland, Japan and Australia). Although there is a lot of literature available to answer the queries that come to the mind of a young investigator, the language is often too complex and difficult to understand and thus, aversive. Some of these teaching materials sound more like experts talking to each other. This book would act as a catalyst in providing useful reviews and guidance related to different aspects of research for students who need to be inducted and recogniz...

Emil Ilyasov

Mustafe Hassan Dahir

Kiyoung Kim

What is the research for in the society? We may imagine the professionals engaged in these activities, shall we say, university professors, researchers in the public and private institutions, and even the lay inventors at home or in the neighborhood. The research is related with some of knowledge or ideas, which, however, should be creative and original. It is the main function of those professionals, and can develop in dissemination of the findings produced by research. It frontiers the knowledge of humans which enables a better view of world and generates the public welfare. The scholars are often those professionals who are required or in some cases, squeezed to produce an original contribution to the specific field of academy. As the society develops, we now require a scientific knowledge beyond the plain understanding of the nature and society. The scientific knowledge is qualified of some elements, i.e., evidence-based, universal frame to be applied, sense of understanding, pragmatic in comprehension or application, more persuasion on theory, paradigm, typologies, intersubjectivity, empirical relevance and so. It informs a philosophy of humans, makes them conscientious and knowledgeable, as well as enhances a professional performance for not only their field but also other disciplines. For example, the criminal justice system borrows the idea or information confirmed by other disciplines, psychology and sociology notably. What is the Durham rule in the excuse of culpability? The scope of rule could not enjoy a persuasion if not to be supported by the works of psychologists. The scientific knowledge perhaps could recourse its most salient dynamism in coupling with an economic exploitation. A cultivation of knowledge to serve the economic use and its industrialization reveals it’s competitive edge in the society. The kind of concepts, information age, e-technology, and intellectual property rights are leading the present time of narrative as we see routinely. May new laws, and new concept of e-education or e-government, GMO products as well as the travel of universe in the near future also follow that the updated profile of scientific knowledge on the engineering and natural science contributed to expand our horizon of subsistence.

RELATED PAPERS

Esther Lopez

Franco Franceschini

2008 Winter Simulation Conference

ruben daniel paez ruiz

Journal of Istanbul University Faculty of Dentistry

Korkud Demirel

Journal of Differential Equations

Yoshihiro Shibata

Cadernos de Estudos Lingüísticos

Lúcia Arantes

Josep Maria Toldrà

Norma Gonzalez

Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports

akshay gadiya

One Health Outlook

riddhi thakkar

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

Ian Maddieson

The protein journal

ADITYA SINGH

Revista Meta: Avaliação

Rosalino Subtil Chicote

Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health

Antônio Frias

Maria da Saúde

Herbal Medicine: Open Access

Oommen K Mathew PhD

International Journal of Nanotechnology

Le Nguyen Bao Tam (FPL DN)

Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine

Richard Kesler

Journal of Food Process Engineering

Pedro Augusto

Stem Cell Research & Therapy

Maria Elena Quintanilla

European Journal of Internal Medicine

Manuel Diaz Curiel

International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences

Fred Akharaiyi

Measurement

Sedat Nazlibilek

The Journal of Rural Health

Joann Kirchner

Carlos Agelet De Saracibar Bosch

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Significance of the Study

Definition:

Significance of the study in research refers to the potential importance, relevance, or impact of the research findings. It outlines how the research contributes to the existing body of knowledge, what gaps it fills, or what new understanding it brings to a particular field of study.

In general, the significance of a study can be assessed based on several factors, including:

- Originality : The extent to which the study advances existing knowledge or introduces new ideas and perspectives.

- Practical relevance: The potential implications of the study for real-world situations, such as improving policy or practice.

- Theoretical contribution: The extent to which the study provides new insights or perspectives on theoretical concepts or frameworks.

- Methodological rigor : The extent to which the study employs appropriate and robust methods and techniques to generate reliable and valid data.

- Social or cultural impact : The potential impact of the study on society, culture, or public perception of a particular issue.

Types of Significance of the Study

The significance of the Study can be divided into the following types:

Theoretical Significance

Theoretical significance refers to the contribution that a study makes to the existing body of theories in a specific field. This could be by confirming, refuting, or adding nuance to a currently accepted theory, or by proposing an entirely new theory.

Practical Significance

Practical significance refers to the direct applicability and usefulness of the research findings in real-world contexts. Studies with practical significance often address real-life problems and offer potential solutions or strategies. For example, a study in the field of public health might identify a new intervention that significantly reduces the spread of a certain disease.

Significance for Future Research

This pertains to the potential of a study to inspire further research. A study might open up new areas of investigation, provide new research methodologies, or propose new hypotheses that need to be tested.

How to Write Significance of the Study

Here’s a guide to writing an effective “Significance of the Study” section in research paper, thesis, or dissertation:

- Background : Begin by giving some context about your study. This could include a brief introduction to your subject area, the current state of research in the field, and the specific problem or question your study addresses.

- Identify the Gap : Demonstrate that there’s a gap in the existing literature or knowledge that needs to be filled, which is where your study comes in. The gap could be a lack of research on a particular topic, differing results in existing studies, or a new problem that has arisen and hasn’t yet been studied.

- State the Purpose of Your Study : Clearly state the main objective of your research. You may want to state the purpose as a solution to the problem or gap you’ve previously identified.

- Contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

- Addresses a significant research gap.

- Offers a new or better solution to a problem.

- Impacts policy or practice.

- Leads to improvements in a particular field or sector.

- Identify Beneficiaries : Identify who will benefit from your study. This could include other researchers, practitioners in your field, policy-makers, communities, businesses, or others. Explain how your findings could be used and by whom.

- Future Implications : Discuss the implications of your study for future research. This could involve questions that are left open, new questions that have been raised, or potential future methodologies suggested by your study.

Significance of the Study in Research Paper

The Significance of the Study in a research paper refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic being investigated. It answers the question “Why is this research important?” and highlights the potential contributions and impacts of the study.

The significance of the study can be presented in the introduction or background section of a research paper. It typically includes the following components:

- Importance of the research problem: This describes why the research problem is worth investigating and how it relates to existing knowledge and theories.

- Potential benefits and implications: This explains the potential contributions and impacts of the research on theory, practice, policy, or society.

- Originality and novelty: This highlights how the research adds new insights, approaches, or methods to the existing body of knowledge.

- Scope and limitations: This outlines the boundaries and constraints of the research and clarifies what the study will and will not address.

Suppose a researcher is conducting a study on the “Effects of social media use on the mental health of adolescents”.

The significance of the study may be:

“The present study is significant because it addresses a pressing public health issue of the negative impact of social media use on adolescent mental health. Given the widespread use of social media among this age group, understanding the effects of social media on mental health is critical for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. This study will contribute to the existing literature by examining the moderating factors that may affect the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes. It will also shed light on the potential benefits and risks of social media use for adolescents and inform the development of evidence-based guidelines for promoting healthy social media use among this population. The limitations of this study include the use of self-reported measures and the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference.”

Significance of the Study In Thesis

The significance of the study in a thesis refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic and the potential impact of the study on the field of study or society as a whole. It explains why the research is worth doing and what contribution it will make to existing knowledge.

For example, the significance of a thesis on “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” could be:

- With the increasing availability of healthcare data and the development of advanced machine learning algorithms, AI has the potential to revolutionize the healthcare industry by improving diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes. Therefore, this thesis can contribute to the understanding of how AI can be applied in healthcare and how it can benefit patients and healthcare providers.

- AI in healthcare also raises ethical and social issues, such as privacy concerns, bias in algorithms, and the impact on healthcare jobs. By exploring these issues in the thesis, it can provide insights into the potential risks and benefits of AI in healthcare and inform policy decisions.

- Finally, the thesis can also advance the field of computer science by developing new AI algorithms or techniques that can be applied to healthcare data, which can have broader applications in other industries or fields of research.

Significance of the Study in Research Proposal

The significance of a study in a research proposal refers to the importance or relevance of the research question, problem, or objective that the study aims to address. It explains why the research is valuable, relevant, and important to the academic or scientific community, policymakers, or society at large. A strong statement of significance can help to persuade the reviewers or funders of the research proposal that the study is worth funding and conducting.

Here is an example of a significance statement in a research proposal:

Title : The Effects of Gamification on Learning Programming: A Comparative Study

Significance Statement:

This proposed study aims to investigate the effects of gamification on learning programming. With the increasing demand for computer science professionals, programming has become a fundamental skill in the computer field. However, learning programming can be challenging, and students may struggle with motivation and engagement. Gamification has emerged as a promising approach to improve students’ engagement and motivation in learning, but its effects on programming education are not yet fully understood. This study is significant because it can provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of gamification in programming education and inform the development of effective teaching strategies to enhance students’ learning outcomes and interest in programming.

Examples of Significance of the Study

Here are some examples of the significance of a study that indicates how you can write this into your research paper according to your research topic:

Research on an Improved Water Filtration System : This study has the potential to impact millions of people living in water-scarce regions or those with limited access to clean water. A more efficient and affordable water filtration system can reduce water-borne diseases and improve the overall health of communities, enabling them to lead healthier, more productive lives.

Study on the Impact of Remote Work on Employee Productivity : Given the shift towards remote work due to recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this study is of considerable significance. Findings could help organizations better structure their remote work policies and offer insights on how to maximize employee productivity, wellbeing, and job satisfaction.

Investigation into the Use of Solar Power in Developing Countries : With the world increasingly moving towards renewable energy, this study could provide important data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing solar power solutions in developing countries. This could potentially stimulate economic growth, reduce reliance on non-renewable resources, and contribute to global efforts to combat climate change.

Research on New Learning Strategies in Special Education : This study has the potential to greatly impact the field of special education. By understanding the effectiveness of new learning strategies, educators can improve their curriculum to provide better support for students with learning disabilities, fostering their academic growth and social development.

Examination of Mental Health Support in the Workplace : This study could highlight the impact of mental health initiatives on employee wellbeing and productivity. It could influence organizational policies across industries, promoting the implementation of mental health programs in the workplace, ultimately leading to healthier work environments.

Evaluation of a New Cancer Treatment Method : The significance of this study could be lifesaving. The research could lead to the development of more effective cancer treatments, increasing the survival rate and quality of life for patients worldwide.

When to Write Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section is an integral part of a research proposal or a thesis. This section is typically written after the introduction and the literature review. In the research process, the structure typically follows this order:

- Title – The name of your research.

- Abstract – A brief summary of the entire research.

- Introduction – A presentation of the problem your research aims to solve.

- Literature Review – A review of existing research on the topic to establish what is already known and where gaps exist.

- Significance of the Study – An explanation of why the research matters and its potential impact.

In the Significance of the Study section, you will discuss why your study is important, who it benefits, and how it adds to existing knowledge or practice in your field. This section is your opportunity to convince readers, and potentially funders or supervisors, that your research is valuable and worth undertaking.

Advantages of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section in a research paper has multiple advantages:

- Establishes Relevance: This section helps to articulate the importance of your research to your field of study, as well as the wider society, by explicitly stating its relevance. This makes it easier for other researchers, funders, and policymakers to understand why your work is necessary and worth supporting.

- Guides the Research: Writing the significance can help you refine your research questions and objectives. This happens as you critically think about why your research is important and how it contributes to your field.

- Attracts Funding: If you are seeking funding or support for your research, having a well-written significance of the study section can be key. It helps to convince potential funders of the value of your work.

- Opens up Further Research: By stating the significance of the study, you’re also indicating what further research could be carried out in the future, based on your work. This helps to pave the way for future studies and demonstrates that your research is a valuable addition to the field.

- Provides Practical Applications: The significance of the study section often outlines how the research can be applied in real-world situations. This can be particularly important in applied sciences, where the practical implications of research are crucial.

- Enhances Understanding: This section can help readers understand how your study fits into the broader context of your field, adding value to the existing literature and contributing new knowledge or insights.

Limitations of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section plays an essential role in any research. However, it is not without potential limitations. Here are some that you should be aware of:

- Subjectivity: The importance and implications of a study can be subjective and may vary from person to person. What one researcher considers significant might be seen as less critical by others. The assessment of significance often depends on personal judgement, biases, and perspectives.

- Predictability of Impact: While you can outline the potential implications of your research in the Significance of the Study section, the actual impact can be unpredictable. Research doesn’t always yield the expected results or have the predicted impact on the field or society.

- Difficulty in Measuring: The significance of a study is often qualitative and can be challenging to measure or quantify. You can explain how you think your research will contribute to your field or society, but measuring these outcomes can be complex.

- Possibility of Overstatement: Researchers may feel pressured to amplify the potential significance of their study to attract funding or interest. This can lead to overstating the potential benefits or implications, which can harm the credibility of the study if these results are not achieved.

- Overshadowing of Limitations: Sometimes, the significance of the study may overshadow the limitations of the research. It is important to balance the potential significance with a thorough discussion of the study’s limitations.

- Dependence on Successful Implementation: The significance of the study relies on the successful implementation of the research. If the research process has flaws or unexpected issues arise, the anticipated significance might not be realized.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Internet Explorer is no longer supported by Microsoft. To browse the NIHR site please use a modern, secure browser like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge.

How to disseminate your research

Published: 01 January 2019

Version: Version 1.0 - January 2019

This guide is for researchers who are applying for funding or have research in progress. It is designed to help you to plan your dissemination and give your research every chance of being utilised.

What does NIHR mean by dissemination?

Effective dissemination is simply about getting the findings of your research to the people who can make use of them, to maximise the benefit of the research without delay.

Research is of no use unless it gets to the people who need to use it

Professor Chris Whitty, Chief Scientific Adviser for the Department of Health

Principles of good dissemination

Stakeholder engagement: Work out who your primary audience is; engage with them early and keep in touch throughout the project, ideally involving them from the planning of the study to the dissemination of findings. This should create ‘pull’ for your research i.e. a waiting audience for your outputs. You may also have secondary audiences and others who emerge during the study, to consider and engage.

Format: Produce targeted outputs that are in an appropriate format for the user. Consider a range of tailored outputs for decision makers, patients, researchers, clinicians, and the public at national, regional, and/or local levels as appropriate. Use plain English which is accessible to all audiences.

Utilise opportunities: Build partnerships with established networks; use existing conferences and events to exchange knowledge and raise awareness of your work.

Context: Understand the service context of your research, and get influential opinion leaders on board to act as champions. Timing: Dissemination should not be limited to the end of a study. Consider whether any findings can be shared earlier

Remember to contact your funding programme for guidance on reporting outputs .

Your dissemination plan: things to consider

What do you want to achieve, for example, raise awareness and understanding, or change practice? How will you know if you are successful and made an impact? Be realistic and pragmatic.

Identify your audience(s) so that you know who you will need to influence to maximise the uptake of your research e.g. commissioners, patients, clinicians and charities. Think who might benefit from using your findings. Understand how and where your audience looks for/receives information. Gain an insight into what motivates your audience and the barriers they may face.

Remember to feedback study findings to participants, such as patients and clinicians; they may wish to also participate in the dissemination of the research and can provide a powerful voice.

When will dissemination activity occur? Identify and plan critical time points, consider external influences, and utilise existing opportunities, such as upcoming conferences. Build momentum throughout the entire project life-cycle; for example, consider timings for sharing findings.

Think about the expertise you have in your team and whether you need additional help with dissemination. Consider whether your dissemination plan would benefit from liaising with others, for example, NIHR Communications team, your institution’s press office, PPI members. What funds will you need to deliver your planned dissemination activity? Include this in your application (or talk to your funding programme).

Partners / Influencers: think about who you will engage with to amplify your message. Involve stakeholders in research planning from an early stage to ensure that the evidence produced is grounded, relevant, accessible and useful.

Messaging: consider the main message of your research findings. How can you frame this so it will resonate with your target audience? Use the right language and focus on the possible impact of your research on their practice or daily life.

Channels: use the most effective ways to communicate your message to your target audience(s) e.g. social media, websites, conferences, traditional media, journals. Identify and connect with influencers in your audience who can champion your findings.

Coverage and frequency: how many people are you trying to reach? How often do you want to communicate with them to achieve the required impact?

Potential risks and sensitivities: be aware of the relevant current cultural and political climate. Consider how your dissemination might be perceived by different groups.

Think about what the risks are to your dissemination plan e.g. intellectual property issues. Contact your funding programme for advice.

More advice on dissemination

We want to ensure that the research we fund has the maximum benefit for patients, the public and the NHS. Generating meaningful research impact requires engaging with the right people from the very beginning of planning your research idea.

More advice from the NIHR on knowledge mobilisation and dissemination .

Communicating and disseminating research findings to study participants: Formative assessment of participant and researcher expectations and preferences

Affiliations.

- 1 College of Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

- 2 College of Health Professions/Healthcare Leadership & Management, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

- 3 South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute (CTSA), Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

- 4 SOGI-SES Add Health Study Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

- 5 College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

- PMID: 32695495

- PMCID: PMC7348011

- DOI: 10.1017/cts.2020.9

Introduction: Translating research findings into practice requires understanding how to meet communication and dissemination needs and preferences of intended audiences including past research participants (PSPs) who want, but seldom receive, information on research findings during or after participating in research studies. Most researchers want to let others, including PSP, know about their findings but lack knowledge about how to effectively communicate findings to a lay audience.

Methods: We designed a two-phase, mixed methods pilot study to understand experiences, expectations, concerns, preferences, and capacities of researchers and PSP in two age groups (adolescents/young adults (AYA) or older adults) and to test communication prototypes for sharing, receiving, and using information on research study findings.

Principal results: PSP and researchers agreed that sharing study findings should happen and that doing so could improve participant recruitment and enrollment, use of research findings to improve health and health-care delivery, and build community support for research. Some differences and similarities in communication preferences and message format were identified between PSP groups, reinforcing the best practice of customizing communication channel and messaging. Researchers wanted specific training and/or time and resources to help them prepare messages in formats to meet PSP needs and preferences but were unaware of resources to help them do so.

Conclusions: Our findings offer insight into how to engage both PSP and researchers in the design and use of strategies to share research findings and highlight the need to develop services and support for researchers as they aim to bridge this translational barrier.

Keywords: Communication; dissemination; research findings; research participant preference; researcher preference.

© The Association for Clinical and Translational Science 2020.

Grants and funding

- UL1 TR001450/TR/NCATS NIH HHS/United States

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley-Blackwell Online Open

Language: English | Chinese

Key components of knowledge transfer and exchange in health services research: Findings from a systematic scoping review

卫生服务研究中知识传递和交流的关键组分:系统性范围综述得来的调查结果, lucia prihodova.

1 UCD School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Dublin Ireland

2 Palliative Care Research Network, All Ireland Institute for Hospice and Palliative Care, Dublin Ireland

Suzanne Guerin

3 UCD Centre for Disability Studies, University College Dublin, Dublin Ireland

Conall Tunney

W. george kernohan.

4 Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Belfast Northern Ireland

Associated Data

To identify the key common components of knowledge transfer and exchange in existing models to facilitate practice developments in health services research.

There are over 60 models of knowledge transfer and exchange designed for various areas of health care. Many of them remain untested and lack guidelines for scaling‐up of successful implementation of research findings and of proven models ensuring that patients have access to optimal health care, guided by current research.

A scoping review was conducted in line with PRISMA guidelines. Key components of knowledge transfer and exchange were identified using thematic analysis and frequency counts.

Data Sources

Six electronic databases were searched for papers published before January 2015 containing four key terms/variants: knowledge, transfer, framework, health care.

Review Methods

Double screening, extraction and coding of the data using thematic analysis were employed to ensure rigour. As further validation stakeholders’ consultation of the findings was performed to ensure accessibility.

Of the 4,288 abstracts, 294 full‐text articles were screened, with 79 articles analysed. Six key components emerged: knowledge transfer and exchange message, Stakeholders and Process components often appeared together, while from two contextual components Inner Context and the wider Social, Cultural and Economic Context, with the wider context less frequently considered. Finally, there was little consideration of the Evaluation of knowledge transfer and exchange activities. In addition, specific operational elements of each component were identified.

Conclusions

The six components offer the basis for knowledge transfer and exchange activities, enabling researchers to more effectively share their work. Further research exploring the potential contribution of the interactions of the components is recommended.

目的

的在于确定已有模式中知识传递和交流的关键通用组分,以促进卫生服务研究的实践发展。

背景为各种医疗保健领域设计了60多种知识转移和交流模式。当中许多吧没有进行测试,也没有指导方针来既扩大研究结果的成功实施,又没有指导方针来扩大已证模型的成功实施,以便于确保患者在当前研究的指导下获得最佳的医疗保健。

设计

根据PRISMA指南进行了范围综述。采用了主题分析和频率计数来确定知识传递和交流的关键组分。

数据来源

在6个电子数据库中搜索了2015年1月之前发表的论文,其中包含四个关键术语/变体:知识、传递、框架、医疗保健。

综述方法

采用了主题分析对数据进行双重筛选,提取和编码,以便确保严谨性。随着进一步确认,利益相关者对调查结果进行了协商,以确保可访问性。

结果

在4288篇摘要中,筛选了294篇全文文章,分析了79篇文章。出现了6个关键组分:知识传递和交流信息、利益相关者和流程组件经常一起出现、而出现于两个上下文组件——内部语境和更广阔的社会,文化和经济语境、不太经常考虑更广阔的语境。最后,很少考虑对知识传递和交流活动的评估。此外,还确定了每个组分的具体操作要素。

结论

这六个组分为知识传递和交流活动提供了基础,使研究人员能够更有效地共享其工作。建议进一步研究探讨组件交互的潜在贡献。

Why is this research or review needed?

- There is lack of studies that inform the application of knowledge transfer and exchange strategies across various healthcare settings to enable evidence‐based practice.

- Analysis and synthesis of existing knowledge transfer and exchange frameworks would identify their commonalities and core concepts.

What are the key findings?

- Six key components emerged from analysis of 79 articles; the knowledge transfer and exchange Message, Stakeholders and Process, Inner Context, Social, Cultural and Economic Context and Evaluation. Their prevalence varied, especially in relation to the Evaluation of KTE activities.

- In addition, specific operational elements of each key component were identified.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

- The components and the specific operational elements offer guidance for knowledge transfer and exchange activities in applied setting and can serve as a framework within which to evaluate their impact.

1. INTRODUCTION

While the ultimate aim of health research is to inform practice and policy, research findings can only change population health outcomes if adopted and embedded by healthcare systems, organizations and clinicians (Grimshaw, Ward, & Eccles, 2006 ). Therefore, it is important to explore the most effective ways of implementing existing evidence into practice (Kutner 2011 ). Applying research findings to practice is especially difficult due to the broad, holistic and elements of complex interventions offered in various practice settings (Evans, Snooks, Howson, & Davies, 2013 ). Several frameworks or models have been developed to provide guidance for the process of implementing research evidence into practice, including the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework (PARiHS; Rycroft‐Malone, 2004 ) and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR, Damschroder et al., 2009 ). This review was performed with the focus on a specific aspect of implementation—the concept of knowledge transfer and exchange (KTE), which is often noted but not explicated in existing models in the area of implementation. Discussing the impact of implementation research in mental health services (Proctor et al., 2009 ) considers KTE in this wider context, noting the movement of research into practice settings as the basis for implementation. They also cite work by the NIH and the CDC, which defines implementation as requiring the generation of knowledge, the dissemination (transfer, our addition) of this knowledge, followed by active efforts to support the implementation of this knowledge.

1.1. Background

There are many terms used to refer to KTE related activity, including dissemination, knowledge transfer and knowledge mobilization. A review by (Pentland et al., 2011 ) highlighted the variation in this area, stressing the challenge that this can create in providing guidance to researchers and practitioners. However, to frame the current research, it is important to be explicit about the definition of KTE that underpins this work. For this study, we adopted the following definition of KTE, as one which is routinely cited in research and reflects the views of the authors:

“an interactive interchange of knowledge between research users and researcher producers (Kiefer et al., 2005 ). [Its purpose is] to increase the likelihood that research evidence will be used in policy and practice decisions and to enable researchers to identify practice and policy‐relevant research questions” (cited in Mitton, Adair, McKenzie, Patten, & Perry, 2007 .729).

KTE is a complex, dynamic and iterative social process, (Kiefer et al., 2005 ; Ward, House, & Hamer, 2009a , 2009b ; Ward, Smith, Foy, House, & Hamer, 2010 ) which does not necessarily contribute directly to implementation but instead to an increased chance that evidence can and will be implemented. Consequently, KTE presents an early challenge to implementation of evidence‐based health care. To be rigorous and effective, it has been recommended that KTE activities are guided by a model that clearly shows how the process works and how it can help knowledge producers and users plan and evaluate KTE activities (Anderson, Allen, Peckham, & Goodwin, 2008 ; Armstrong, Waters, Roberts, Oliver, & Popay, 2006 ; Estabrooks, Squires, Cummings, Birdsell, & Norton, 2009 ; Graham, Tetroe, & Grp, 2007 ; McKibbon et al., 2013 ; Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2009 ; Ward, House, & Hamer, 2009a ; Ward, Smith, House, & Hamer, 2012 ; Wilson, Petticrew, Calnan, & Nazareth, 2010 ). Yet, KTE as a key aspect of implementation has rarely been explicitly operationalized in existing models of implementation.

2. THE REVIEW

The aim of this study was to review, analyse and synthesize the key components of KTE as evidenced in published health services research. Apart from the prevalence of the individual components of the components we will also capture the operational elements of these components and their interactions. To contextualize the components and their interactions, the findings will be presented in a form of a model.

2.2. Design

A scoping approach was adopted, following a detailed protocol (Prihodova, Guerin, & Kernohan, 2015 ). The review was guided the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005 ), with additional amendments based on (Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien, 2010 ; Levac et al., 2010 ). While the protocol for this review set out as one of the aims as appraisal of the relevance and suitability of these components for providers, settings and dimensions of palliative care, this study will report the general components of KTE in any healthcare setting identified by the review and their appraisal for palliative care will be addressed in a subsequent publication. In addition, in the absence of reporting guidelines for scoping reviews, the six‐stage process (Table 1 ) was benchmarked against the PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Grp, 2009 ) to ensure rigour.

Stages of systematic review applied

2.3. Search strategy

The search strategy included four search terms and their variations (knowledge (evidence, research, information, data), transfer (exchange, generation, translation, uptake, mobilization, dissemination, implementation), framework (model, concept) and health care (health system, health service, healthcare provider)) and was designed to be as extensive as possible. The search was performed across six main electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE (Elsevier), CINAHL Plus (EBSCO), PsycINFO (ProQuest), Social Services Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)). Only studies that sufficiently described an original (or adapted) explicit framework, model or concept of KTE applied in healthcare setting were included.

To be included, articles had to provide a description of an original (or adapted) model or framework (noting that these terms are often used interchangeably) that considered the implementation of research knowledge and its application. This included articles which presented a specific model of KTE and articles that used KTE models or model elements to inform the implementation of research into practice. Limiting searches to health services settings was intended to ensure a practical focus of the work and the potential to synthesize the operational elements of the KTE process rather than just the theoretical.

2.4. Search outcomes

The initial database search identified 7,544 abstracts with none identified elsewhere (Figure 1 ). After the removal of duplicates ( N = 2,672; 35%), a further 7.7% of abstracts were removed due to following exclusion criteria: not research articles ( N = 356; book/book chapter/conference proceedings, etc.); low quality ( N = 158; no abstract, published in non‐peer reviewed journals); were not involving humans ( N = 70). The remaining abstracts ( N = 4,288; 57%) were screened independently by two authors (92% agreement rate on inclusion/exclusion), resulting in 298 (3.9%) articles identified for full‐text screening.

Flow diagram of the systematic review (modified from Moher et al., 2009 )

From the identified abstracts, we were unable to source 12 full‐texts and therefore 286 full‐texts were reviewed independently by two reviewers, with 75% agreement on inclusion/exclusion. A further 202 articles (71%) articles were removed at the full‐text review as they were found to not fit the inclusion criteria, with the final number 84 (29%) of articles included in data extraction. At the data extraction phase, the articles underwent a criteria appraisal (Table 3) and five more articles were removed following an in‐depth analysis due to very vague description of the model or its application. The final number of articles included in data analysis was 79 (28%). The summary details of these articles are included in Table 2 .

Studies identified by systematic review and included in the final analysis grouped by model used

2.5. Quality appraisal

In line with scoping reviews, limited application of quality appraisal criteria was undertaken; and aggregated quality assessments of the dataset are presented rather than study level assessments (Table 3 ).

Quality appraisal of articles included in the scoping review

2.6. Data abstraction and synthesis

Analysis of extracted data was conducted at two levels: descriptive and explorative. Level 1 (descriptive analysis) involved tabulation of basic information such as study design, participant samples and the named models. Level 2 (explorative analysis) involved thematic analysis of narrative data, of the descriptions of identified models and of their visual representations. We used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ) wherein initial coding and the development of candidate themes were conducted independently by two authors, who then met to agree the final thematic map of the findings. Once the themes were agreed, two authors coded the data, while a third author conducted an independent coding check of 10% of the articles. The agreement for the credibility check of the independently coded themes was 83%. Frequency analysis provided the occurrence of each theme across the identified articles, as a reflection of the salience of the theme in the data.

As a validity check, stakeholder consultation was performed by presenting the findings at a national workshop for researchers, policy makers and patient/carer representatives in health services research. A stenographer recorded the workshop and feedback was gathered from attendees to allow reflection on the discussions. No significant changes were made to the components; however, the discussion highlighted the need for some clarity regarding the operational elements and the nature of the interaction between components. This led to some changes in the naming of components and operational elements and more clarity on structure. A visualization, incorporating the revisions from this process is presented in this paper.

3.1. Overview of articles and models

Of the 79 articles included in this scoping review, the majority were published in medical (53%) and nursing (25%) journals, followed by behavioural/psychological journals (7.6%), journals on medical training (6.3%), health services research (5%) and miscellaneous (2.1%). The earliest studies were published in 1985, with 2014 being the latest year included in the search; 70 articles (89%) were published after 2001 and over a third of all articles (35%) were published after 2010. This suggests a relatively recent increase in interest in the issue of knowledge transfer in health research.

In the 79 articles were references to 88 models or frameworks (including multiple occurrences across articles), with 49 unique models/frameworks named and 13 models not explicitly named. Five models were mentioned in multiple articles, with PARiHS being the most frequently cited (Rycroft‐Malone, 2004 ). When it came to the theoretical background of the framework, 19 (24%) articles provided no information, while 24 (30%) referred to previous publications. From the remaining articles, 25 (32%) referred to multiple other models/frameworks or theories and 11 (14%) to a single framework. Over half of the articles indicated the target audience for the KTE ( N = 43, 54%), with the majority proposing the use of the model in multiple stakeholder groups ( N = 32, 41%).

Our quality appraisal focused on fatal flaws, as outlined by Dixon‐Woods et al. (Dixon‐Woods et al., 2006 ). We also rated the level of detail in the description of the framework or its application. The findings highlight several limitations (see Table 3 ). All articles had clear statements of the aims and objectives, a majority (>90%) had a clearly described research design (where appropriate) and a significant proportion (76%) provided sufficient detail to analyse the framework. However, fewer articles (67%) provided a clear account of data analysis and findings or presented data to support their interpretations (40%), which may highlight the need for more critical evaluation of dissemination activities and limitations in the quality of this research.

3.2. Identifying the core components and operational elements of knowledge transfer and exchange

From the thematic analysis, six key themes were identified to represent the core components of KTE.

The first component of KTE—the Message reflects the information to be shared. Within this component, the most common operational element was the idea that the message is needs‐driven . This often‐presented research as a clinical or practical problem, while multiple studies applying the PARiHS framework referred to the research as needs‐ or problem‐based (Kristensen, Borg, & Hounsgaard, 2011 ; Rycroft‐Malone, 2004 ; Tilson & Mickan, 2014 ). The operational elements or attributes of the message as credible and actionable occurred with equal frequency. Research findings being actionable related to its use or application in practice and were particularly evident in articles considering the Ottawa Model of Research Use (Logan & Graham, 1998 ; Logan, Harrison, Graham, Dunn, & Bissonnette, 1999 ; Pronovost, Berenholtz, & Needham, 2008 ). The credibility of the message referred to the use of outcomes that are considered valid (Pronovost et al., 2008 ). Jack and Tonmyr (Jack & Tonmyr, 2008 ) applied Lavis’ model of KTE and referred to the importance of messages containing credible information. Occurring slightly less frequently was the operational element of the message as accessible , which was represented in as translating the knowledge or tailoring it for key stakeholders (Kitson et al., 2013 ; Tugwell, O'Connor, et al., 2006 ). The final operational element noted was that multiple types of message are important , which reflected the use of different research methods to generate messages and the potential for research to have different messages to transfer. For example, the revised PARiHS Framework (Rycroft‐Malone et al., 2002 ) noted that different types of research evidence are required to answer different questions relevant to practice.

The Process component represented the activities intended to implement the transfer of knowledge. This was often identified as a collaborative aspect of KTE, reflecting the “push‐pull” dynamic exchange of information. Taking the operational element of KTE as an interactive exchange, the Research Practice Integration model (Sterling & Weisner, 2006 ) referred to the bidirectional relationship between stakeholders in treatment and research. KTE was described as requiring skilled facilitation, with multiple articles referring to PARiHS model that highlights the importance of this. The KTE processes were also expected to be targeted and timely, stressing the need to target key groups such as policy makers (Aguilar‐Gaxiola et al., 2002b ), recognizing the importance of activities taking place at the right time (Haynes, Hayward, & Lomas, 1995 ).

The Process component also included the operational element of marketing the message, reflecting the need for the communicators (typically the researchers) to communicate in a way that effectively pitched information to their target audience. Herr et al. (Borbas, Morris, McLaughlin, Asinger, & Gobel, 2000 ; Herr, English, & Brown, 2003 ) drew on the Knowledge Development and Application model, discussing the need to ‘get the message out’ through dissemination activities. The KTE process was also recognized to require the support or endorsement of opinion leaders/champions, for example the article by Borbas et al. (Borbas et al., 2000 ) reported on their Healthcare Education and Research Foundation process, which uses clinical opinion leaders to support research implementation, while the Translating Research into Practice model reported by Tschannen et al. (Tschannen, Talsma, Gombert, & Mowry, 2011 ) also highlights the use of opinion leaders in the process. The final operational element reflected the need for KTE to draw on diverse activities, for example Aguilar‐Gaxiola et al. described multiple multifaceted activities as part of research on mental health care for Mexican Americans (Aguilar‐Gaxiola et al., 2002a , 2002b ).

The Stakeholders represent the people involved on either side of the exchange process. This was operationalized into four operational elements: knowledge users, knowledge beneficiaries and multiple stakeholders. The knowledge producers refer predominantly to the researchers themselves (Dufault, 2004 ; Ho et al., 2004 ; Sterling & Weisner, 2006 ); while knowledge users , sometimes referred to as knowledge consumers (Ho et al., 2004 ) represent the most common stakeholders—practitioners and policy makers, positioning them in the context of communities of professional practice, e.g., primary care practitioners (McCaughan, 2005 ). The knowledge beneficiaries represent the wider group of patients and families who benefit from the implementation (Hemmelgarn et al., 2012 ; Jack & Tonmyr, 2008 ). Finally, several papers emphasized that those involved in KTE have multiple stakeholders to consider including patients’ families and the general public (Anderson, Cosby, et al., 1999b ; Ho et al., 2004 ; Orlandi, 1987 ).

The context for KTE was reported at two important levels: local and wider social, economic and cultural. The Local Context, addressing the immediate, often organizational environments, where the transfer would occur, included four operational elements. The most prevalent of these was organizational influence, with organizations and their leaders/managers identified as key influencers in the KTE process. Senior colleagues in organizations were reported as instrumental in the adoption of research knowledge to implement change, (Dobbins, Ciliska, Cockerill, Burnsley, & DiCenso, 2002 ) or support evidence‐based practice (Stetler, 2003 ). Closely linked to this was the operational element of organizational culture, which may be expressed as the attitudes, knowledge and values expressed in the organization. Multiple articles implementing the PARIHS Framework (Helfrich et al., 2010 ) or the Translating Research into Practice model highlighted the importance of organizational culture and the importance of setting organizational standards (Tschannen et al., 2011 ).

Our findings highlighted the need for dedicated resources for KTE activities . For example, the Multisystem Model of Knowledge Integration and Translation, referred to resourcing effective implementation (Palmer & Kramlich, 2011 ), while the Conservation of Resources Theory, recognized the range of resources required and noted that these may differ at different stages of the process (Alvaro et al., 2010 ). The final operational element in this section was readiness for knowledge . One application of PARIHS emphasized receptivity of the context—a factor which is common in many of the articles applying or using this KTE model (Helfrich et al., 2011 ).

The inclusion of the Social, Cultural & Economic Context component recognized the influence of wider environmental factors influencing research and practice. While this was the least frequent theme it was evident in the Evidence‐based Information Circle, designed to help practitioners engage with evidence‐based practice (Thomson‐O'Brien & Moreland, 1998 ). This component included an outer context representing factors that may have an impact on decision making, with specific reference to aspects of the social, cultural and economic context. In the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model the external environment was considered to have an influence on the implementation of research (Feldstein & Glasgow, 2008 ) while in the CFIR model, the outer setting incorporating wider cultural, political and economic factors was explicitly referenced (Damschroder & Hagedorn, 2011 ).

The final component of KTE highlighted the importance of evaluation in the model, with the concept of Evaluating Efficacy expressing the need for a mechanism for evaluation of the success of the knowledge transfer activity. It is interesting to note that, alongside the theme of Social, Cultural and Economic context, this component was least prevalent in the coding of data extracted. The Ottawa Model of Research Use (Logan & Graham, 1998 ; Logan et al., 1999 ) highlighted the importance of evaluating the outcomes of KTE and implementation work, while others referred to the importance of examining the effectiveness of transfer activities (Anderson, Caplan, et al., 1999a ) and the importance of both outcome and process evaluation (Sakala & Mayberry, 2006 ).

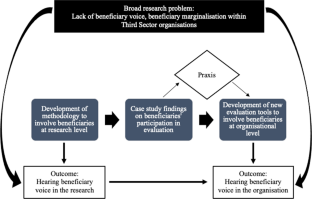

3.3. Reflections on the structure of the components

Informed by the discussions at the stakeholder workshop, a visualization incorporating these components is presented in Figure 2 . Also included are the operational elements identified as part of the analysis and the frequency of occurrence of each component and operational element.

Key components of knowledge transfer identified through thematic analysis (with frequencies reported)

Taking the components together the starting point of KTE activity is the knowledge to be transferred ( the Message ). The message is influenced by the Stakeholders, recognizing that there may be multiple groups who may influence the way the message needs to be communicated). Based on the message and the stakeholders the knowledge producer should identify the Processes to be used to ensure the message can be delivered to the stakeholders effectively. Also important is allowing for feedback to come back though the same channels. These interacting components sit in two identified layers, the Local Context and the wider Social, Cultural and Economic Context and highlight the need for researchers to consider how these contexts may have an impact on the Message, Stakeholders and Processes.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this review was to identify key components and related operational elements of KTE, intended to guide researchers’ actions in relation to KTE, in the broader context of implementation. The search identified 79 articles which included an explicit model related to transferring research findings in health settings. These articles were drawn from a range of disciplines, although medicine and nursing were the most common. The publication date range highlights a recent increase in research and dissemination activity in this area. This review identified almost 50 individual models or frameworks, with PARiHS the most frequent. Quality appraisal of the articles highlighted several limitations to the quality of the research; however, few articles were excluded on the basis of a lack of information on the model itself.

The thematic analysis identified six core components of KTE, three of which were commonly present in the articles. The messages to be transferred, the stakeholders and the specific processes by which transfer was achieved were considered in detail. However, the key practical finding lies in the operational elements in these components, which provide more specific and practical guidance for researchers intending to maximize the potential impact of their research. Recognizing that multiple types of message are important highlights the need to be aware of different processes when communicating with different stakeholders. Echoing this, the use of diverse activities as part of the KTE process was rarely evident in articles, perhaps due to the dominance of traditional methods that focus on academic dissemination. Another key finding is the importance of targeted and timely KTE activities. Rather than planning for dissemination at the end of the research process, the evidence presented in this review stresses the need for KTE to be an ongoing activity across the lifetime of the project. While transfer processes were frequently considered in previous studies, few considered multiple processes for a single study, suggesting a simplistic, linear approach to knowledge transfer. This does not reflect the complex non‐linear process of KTE evident across the findings of this review.

Recognizing the context where KTE is to take place is another key finding. While the immediate or local context was considered in more than half of the articles, the issue of the wider social, cultural and economic context was considered in less detail, with no evidence of specific operational elements to guide the researcher when considering the influence of this wider context. The need to consider not just the local but the wider context represents a possible shift in KTE activities. However, given that change in the health sector is often influenced by these wider factors (for example the impact of an economic recession), it is perhaps surprising that these aspects of the context are poorly expressed in existing models. Given the lack of representation of this component in the existing literature we would argue there is a need to increase awareness of its role in KTE and the possible activities that would operationalize this level of the process.

A novel finding is the lack of evidence that process and outcomes of KTE activity is being evaluated by those engaged in the process. In addition, the presence of methodological issues in the studies, such as lack of grounding in data and or detail on analysis and process, further highlights the need for rigorous evaluation of KTE activities. If researchers apply the key principles of evidence‐based practice to their KTE activities, then evaluating the effectiveness of these KTE activities becomes necessary. The focus on audit of practice evident in other areas of the health services (Ivers et al., 2012 ) could and should be extended to KTE, with researchers recognizing the importance of assessing how effective their KTE activities have been in reaching key stakeholders, beyond more traditional metrics such as article citation counts and journal impacts.

It is important to reflect on the methodological quality of this review before final conclusions can be drawn. While the presented findings are based on evidence pre‐2015, there was an exponential rise in the number of studies published since 2015; re‐running the search terms employed in this review yielded over 4000 results, highlighting the urgency in understanding KTE and implementation. While in‐depth analysis of the search terms is beyond the scope of this review, many of the recent studies were based on refining of existing models and clarifying the ways of using them in the process of implementation, e.g., (Harvey & Kitson, 2016 ). There have been significant developments in the conduct and use of systematic reviews in intervention and health research, which allowed for clear guidance in the development of this review. The method of review used was mapped onto the PRISMA procedure as the agreed process for systematic reviews and validity checks such as phases of independent review were included in the screening of articles and in the extraction and analysis of data. In addition, the methodology of the review was peer reviewed and published in advance of the completion of the study. However, there are limitations, not least the lack of engagement with unpublished and policy‐related literature and the timeframe of the search (papers published before January 2015). Despite these limitations we are confident that the rigour evident in the search and analysis provides a basis for confidence in the findings.

5. CONCLUSION

The components identified represent both established and emerging aspects of KTE, with a clear focus on effective ways of transferring research knowledge to care providers and stakeholders and could be used in applied settings and to inform future research. Specific operational elements in these components can directly guide the researcher to maximize the activities in relation to these components. The synthesis of the components and operational elements identified potentially provides a functional model of KTE that could offer researchers the tools to ensure their KTE activities are appropriate and a framework within which to evaluate their actions. Given the process of identification undertaken in this study the authors are tentatively proposing the structure presented in Figure 2 as an Evidence‐based model for the Transfer and Exchange of Research Knowledge (EMTReK).