- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2022

The effect of active visual art therapy on health outcomes: protocol of a systematic review of randomised controlled trials

- Ronja Joschko ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4450-254X 1 ,

- Stephanie Roll ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1191-3289 1 ,

- Stefan N. Willich 1 &

- Anne Berghöfer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7897-6500 1

Systematic Reviews volume 11 , Article number: 96 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7430 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

Art therapy is a form of complementary therapy to treat a wide variety of health problems. Existing studies examining the effects of art therapy differ substantially regarding content and setting of the intervention, as well as their included populations, outcomes, and methodology. The aim of this review is to evaluate the overall effectiveness of active visual art therapy, used across different treatment indications and settings, on various patient outcomes.

We will include randomised controlled studies with an active art therapy intervention, defined as any form of creative expression involving a medium (such as paint etc.) to be actively applied or shaped by the patient in an artistic or expressive form, compared to any type of control. Any treatment indication and patient group will be included. A systematic literature search of the Cochrane Library, EMBASE (via Ovid), MEDLINE (via Ovid), CINAHL, ERIC, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, and PSYNDEX (all via EBSCOHost), ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) will be conducted. Psychological, cognitive, somatic and economic outcomes will be used. Based on the number, quality and outcome heterogeneity of the selected studies, a meta-analysis might be conducted, or the data synthesis will be performed narratively only. Heterogeneity will be assessed by calculating the p-value for the chi 2 test and the I 2 statistic. Subgroup analyses and meta-regressions are planned.

This systematic review will provide a concise overview of current knowledge of the effectiveness of art therapy. Results have the potential to (1) inform existing treatment guidelines and clinical practice decisions, (2) provide insights to the therapy’s mechanism of change, and (3) generate hypothesis that can serve as a starting point for future randomised controlled studies.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO ID CRD42021233272

Peer Review reports

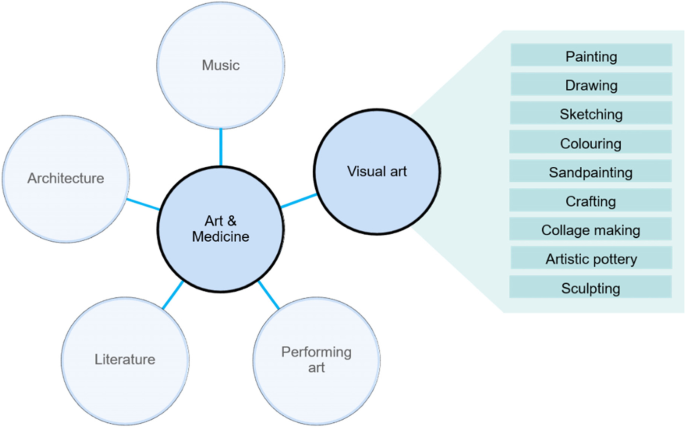

Complementary and integrative treatment methods can play an important role when treating various chronic conditions. Complementary medicine describes treatment methods that are added to the standard therapy regiment, thereby creating an integrative health approach, in the anticipation of better treatment effects and improved health outcomes [ 1 ]. Within a broad field of therapeutic approaches that are used complementarily, art therapy has long occupied a wide space. After an extensive sighting of the literature, we decided to differentiate between five clusters of art that are used in combination with standard therapies: visual arts, performing arts, music, literature, and architecture (Fig. 1 ). Each cluster can either be used actively or receptively.

The five clusters of art used in medicine for therapeutic purposes, with examples of active visual art forms (figure created by the authors)

Active visual art therapy (AVAT) is often used as a complementary therapy method, both in acute medicine and in rehabilitation. The use of AVAT is frequently associated with the treatment of psychiatric, psychosomatic, psychological, or neurological disorders, such as anxiety [ 2 ], depression [ 3 ], eating disorders [ 4 ], trauma [ 5 , 6 ], cognitive impairment, or dementia [ 7 ]. However, the application of AVAT extends beyond that, thereby broadening its potential benefits: it is also used to complement the treatment of cystic fibrosis [ 8 ] or cancer [ 9 , 10 ], to build up resilience and well-being [ 11 , 12 ], or to stop adolescents from smoking [ 13 ].

As a complementary intervention, AVAT aims at reducing symptom burden beyond the effect of the standard treatment alone. Since AVAT is thought to be side effect free [ 14 ] it could be a valuable addition to the standard treatment, offering symptom reduction with no increased risk of adverse events, as well as an potential improvement in quality of life [ 15 , 16 , 17 ].

The existing literature examining the effectiveness of art therapy has shown some positive results across a wide variety of treatment indications, such as the treatment of depression [ 3 , 18 ], anxiety [ 19 , 20 ], psychosis [ 21 ], the enhancement of mental wellbeing [ 22 ], and the complementary treatment of cancer [ 15 , 23 ]. However, the existing evidence is characterised by conflicting results. While some studies report favourable results and treatment successes through AVAT [ 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ], many studies report mixed results [ 3 , 15 , 16 , 27 , 28 ]. There is a substantial number of systematic reviews which examine the effectiveness of art therapy regarding individual outcomes, such as trauma [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ], anxiety [ 19 ] mental health in people who have cancer [ 23 , 34 , 35 ] dementia [ 7 ], and potential harms and benefits of the intervention [ 36 ]. The limited number of published studies, however, can make the creation of a systematic review difficult, especially when narrowing down additional factors, such as the desired study design [ 7 ].

Therefore, it might be helpful to combine all existing evidence on the therapeutic effects of AVAT in one review, to generate evidence regarding its overall effectiveness. To our knowledge, there is no systematic review that accumulates the data of all published RCTs on the topic of AVAT, while abiding to strict methodological standards, such as the Cochrane handbook [ 37 ] and the PRISMA statement [ 38 ]. We thus aim to establish and strengthen the existing evidence basis for AVAT, reflecting the clinical reality by including a wide variety of settings, populations, and treatment indications. Furthermore, we will try to identify characteristics of the setting and the intervention that may increase AVAT’s effectiveness, as well as differences in treatment success for different conditions or reasons for treatment.

Methods/Design

Registration and reporting.

We have submitted the protocol to PROSPERO (the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) on February 9, 2021 (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021233272). In the writing of this protocol we have adhered to the adapted PRISMA-P (Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols, see Additional file 1 ) [ 39 ]. Important protocol amendments will be submitted to PROSPERO.

Eligibility criteria

Type of study.

We will include randomised controlled trials to minimise the sources of bias possibly arising from observational study designs.

Types of participants

As AVAT is used across many patient populations and settings, we will include patients across all treatment indications. Thus, we will include populations receiving curative, palliative, rehabilitative, or preventive care for a variety of reasons. Patients of all ages (including seniors, children and adolescents), all cultural backgrounds, and all living situations (inpatients, outpatients, prison, nursing homes etc.) will be included without further restrictions. The resulting diversity reflects the current treatment reality. Heterogeneity of included studies will be accounted for by subgroup analyses at the stage of data synthesis. Differences in treatment success depending on population characteristics are furthermore of special interest in this review.

Types of interventions

As the therapeutic mechanisms of AVAT are not yet unanimously agreed upon, we want to reduce the heterogeneity of treatment methods included by focusing on only one cluster of art activities (active visual art).

We define AVAT as any form of creative expression involving a medium such as paint, wax, charcoal, graphite, or any other form of colour pigments, clay, sand, or other materials that are applied or shaped by the individual in an artistic or expressive form.

The interventions must include a therapeutic element, such as the targeted guidance from an art therapist or a reflective element. Both, group and individual treatment in any setting are included.

Purely occupational activities not intended to have a therapeutic effect will not be considered.

All forms of music, dance, and performing art therapies, as well as poetry therapy and (expressive) writing interventions which focus on the content rather than appearance (like journal therapy) will not be included. Studies with mixed interventions will be included only if the effects of the AVAT can be separated from the effects of the other treatments. Furthermore, all passive forms of visual art therapy will be excluded, such as receptive viewings of paintings or pictures.

Comparison interventions

Depending on the treatment indication and setting, the control group design will likely vary. We will include studies with any type of control group, because art therapy research, just like psychotherapy research, must face the problem that there are usually no standard controls like, e.g. a placebo [ 40 ]. Therefore, we will include all control groups using treatment as usual (including usual care, standard of care etc.), no treatment (with or without waitlist control design), or any active control other than AVAT (such as attention placebo controls) as potential comparators.

Stakeholder involvement

Stakeholders will be involved to increase the relevance of the study design. Patients, art therapists, and physicians prescribing art therapy, all from a centre that uses AVAT regularly, will be interviewed using a semi structured questionnaire that captures the expert’s perspective on meaningful outcomes. Particularly, we are interested in the stakeholders’ opinions about which outcomes might be most affected by AVAT, which individual differences might be expected, and which other factors could affect the effectiveness of AVAT.

A second session might be held at the stage of result interpretation as the stakeholders’ perspective could be a valuable tool to make sense of the data.

As there is no universal standard regarding the outcomes of AVAT, we have based our choice of outcome measures on selected, high quality work on the subject [ 7 ], and on theoretical considerations.

Outcome measures will include general and disease specific quality of life, anxiety, depression, treatment satisfaction, adverse effects, health economic factors, and other disorder specific outcomes. The latter are of special relevance for the patients and have the potential to reflect the effectiveness of the therapy. The disorder specific outcomes will be further clustered into groups, such as treatment success, mental state, affect and psychological wellbeing, cognitive function, pain (medication), somatic effects, therapy compliance, and motivation/agency/autonomy regarding the underlying disease or its consequences. Depending on the included studies, we might re-evaluate these categories and modify the clusters if necessary.

Outcomes will be grouped into short-term and long-term outcomes, based on the available data. The same approach will be taken for dividing the treatment groups according to intensity, with the aim of observing the dose-response relationship.

Grouping for primary analysis comparisons

AVAT interventions and their comparison groups can be highly divers; therefore, we might group them into roughly similar intervention and comparison groups for the primary analysis, as indicated above. This will be done after the data extraction, but before data analysis, in order to minimise bias.

Search strategy

Based on the recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook we will systematically search the Cochrane Library, EMBASE (via Ovid), and MEDLINE (via Ovid) [ 41 ]. Furthermore, we will search CINAHL, ERIC, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, and PSYNDEX (all via EBSCOHost), as well as the ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), which includes various smaller and national registries, such as the EU Clinical Trials Register and the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS).

The search strategy is comprised of three search components; one concerning the art component, one the therapy component and the last consists of a recommended RCT filter for EMBASE, optimised for sensitivity and specificity [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. See Additional file 2 for the complete search strategy, exemplified for the Cochrane Library search interface. In addition, relevant hand selected articles from individual databank searches, or studies identified through the screening of reference lists will be included in the review. A handsearch of The Journal of Creative Arts Therapies will be conducted.

Results of all languages will be considered, and efforts undertaken to translate articles wherever necessary. There will be no limitation regarding the date of publication of the studies.

Data collection and data management

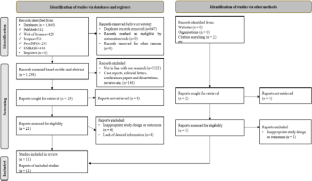

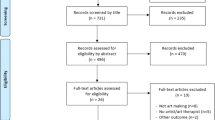

Study selection process.

Two reviewers will independently scan and select the studies, first by title screening, second by abstract screening, and in a third step by full text reading. The two sets of identified studies will then be compared between the two researchers. In case of disagreement that cannot be resolved through discussion, a third researcher will be consulted to decide whether the study in question is eligible for inclusion. The Covidence software will be used for the study selection process [ 45 ].

Data extraction

All relevant data concerning the outcomes, the participants, their condition, the intervention, the control group, the method of imputation of missing data, and the study design will be extracted by two researchers independently and then cross-checked, using a customised and piloted data extraction form. The chosen method of imputation for missing data (due to participant dropout or similar) will be extracted per outcome. Both, intention to treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP) data will be collected and analysed.

If crucial information will be missing from a study and its protocol, authors will be contacted for further details.

Risk of bias assessment for included studies

In line with the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2) [ 46 ], we will examine the internal bias in the included studies regarding their bias arising from the randomisation process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and in selection of the reported result [ 47 ].

The risk will be assessed by two people independently from each other, only in cases of persisting disagreement a third person will be consulted.

If the final sample size allows, we will conduct an additional analysis in which the included studies are analysed separately by bias risk category.

Measures of treatment effect

If possible, we will conduct our main analyses using intention-to-treat data (ITT), but we will collect ITT and per-protocol (PP) data [ 48 ]. If for some studies ITT data is not reported, we will use the available PP data instead and perform a sensitivity analysis to see if that affects the results. Dichotomous data will be analysed using risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals, as they have been shown to be more intuitive to interpret than odds ratio for most people [ 49 ]. We will analyse continuous data using mean differences or standardised mean differences.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster trials.

If original studies did not account for a cluster design, a unit of analysis error may be present. In this case, we will use appropriate techniques to account for the cluster design. Studies in which the authors have adjusted the analysis for cluster-randomisation will be used directly.

Cross-over trials

An inherent risk to cross-over trials is the carry-over effect.

This design is also problematic when measuring unstable conditions such as psychotic episodes, as the timing could account more for the treatment success than the treatment itself (period effect).

As art therapy is used frequently in the treatment of unstable conditions, such as mental health problems or neurodegenerative disorders (i.e. Alzheimer’s), we will include full cross-over trials only if chronic and stable concepts are measured (such as permanent physical disabilities or epilepsy) [ 50 ].

When including cross-over studies measuring stable conditions, we will include both periods of the study. To incorporate the results into a meta-analysis we will combine means, SD or SE from both study periods and analyse them like a parallel group trial [ 51 ]. For bias assessment we will use the risk of bias tool for crossover trials [ 47 ].

For cross-over studies that measure unstable or degenerative conditions of interest, we will only include the first phase of the study as parallel group comparison to minimise the risk of carry-over or period effects. We will evaluate the risk of bias for those cross-over trials using the same standard risk of bias tool as for the parallel group randomised trials [ 52 ]. We will critically evaluate studies that analyse first period data separately, as this might be a form of selective reporting and the inclusion of this data might result in bias due to baseline differences. We might exclude studies that use this kind of two-stage analysis if we suspect selective reporting or high risk for baseline differences [ 47 ].

Missing data

Studies with a total dropout rate of over 50% will be excluded. To account for attrition bias, studies will be downrated in the risk of bias assessment (RoB 2 tool) if the dropout rate is more than half for either the control or the intervention group. An overall dropout rate of 25–50% we will also be downrated.

Assessment of clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity

We will discuss the included studies before calculating statistical comparisons and group them into subgroups to assess their clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed by calculating the p value for the chi 2 test. As few included studies may lead to insensitivity of the p value, we may adjust the cut-off of the p value if we only included a small amount of studies [ 49 ]. In addition, we will calculate the I 2 statistic and its confidence interval, based on the chi 2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity. We will explore possible reasons for observed heterogeneity, e.g. by conducting the planned subgroup analyses. Based on the amount and quality of included studies and their outcome heterogeneity, we will decide if a meta-analysis can be conducted. In case of high statistical heterogeneity, we first check for any potential errors during the data input stage of the review. In a second step, we evaluate if choosing a different effect measure, or if the justified removal of outliers will reduce heterogeneity. If the outcome heterogeneity of the selected studies is still too high, we will not conduct a meta-analysis. If clinical heterogeneity is high but can be reduced by adjusting our planned comparisons, we will do so.

Reporting bias

Funnel plot.

Funnel plots can be a useful tool in detecting a possible publication bias. However, we are aware, that asymmetrical funnel plots can potentially have other causes than an underlying publication bias. As a certain number of studies is needed in order to create a meaningful funnel plot, we will only create those plots, if more than about 10 studies are included in the review.

Data analysis and synthesis

Based on the amount and quality of included studies and their heterogeneity, we will decide if a meta-analysis is feasible.

If a meta-analysis can be conducted, we will be using the inverse variance method with random effects (to increase compatibility with the different identified effect measures and to account for the diversity of the included interventions). We would expect each study to measure a slightly different effect based on differing circumstances and differing intervention characteristics. Therefore, a random effects model is the most suitable option.

A disadvantage of the random effects model is that it does not give studies with large sample sizes enough weight when compared to studies with small sample sizes and therefore could lead to a small study effect. However, we expect to find studies with comparable study sizes with an N of 10–50, as very large trials are uncommon for art therapy research. If we include studies with a very large sample size, we might calculate a fixed effects model additionally, as sensitivity analysis, to assess if this would affect the results.

If the calculation of a meta-analysis is not advisable due to difficulties (such as a low number of included studies, low quality of included studies, high heterogeneity, incompletely reported outcome or effect estimates, differing effect measures that cannot be converted), we will choose the most appropriate method of narrative synthesis for our data, such as the ones described in the Cochrane Handbook (i.e. summarising effect estimates, combining p values or vote counting based on direction of effect) [ 53 ].

Subgroup analysis

If the number of included studies is large enough (around 10 or more [ 54 ]) and subgroups have an adequate size, we plan to compare subgroups based on the therapy setting (inpatient, outpatient, kind of institution), the intervention characteristics (the kind of AVAT, intensity of treatment, staff training, group size), the population (treatment indication, age, gender, country), or other study characteristics (e.g. bias category, publication date). If possible, we will also examine these factors by calculating meta-regressions.

Sensitivity analysis

Where possible, sensitivity analyses will be conducted using different methods to establish robustness of the overall results. Specifically, we will assess the robustness of the results regarding cluster randomisation and high risk of bias (RoB 2 tool).

AVAT encompasses a wide array of highly diverse treatment options for a multitude of treatment indications. Even though AVAT is a popular treatment method, the empirical base for its effectiveness is rather fragmented; many (often smaller) studies examined the effect of very specific kinds of AVATs, with a narrow focus on certain conditions [ 2 , 7 , 55 , 56 ]. Our review will give a current overview over the entire field, with the hope of estimating the magnitude of its effectiveness. Several clinical guidelines recommend art therapy based solely on clinical consensus [ 57 ]. By accumulating all empirical evidence, this systematic review could inform the creation of future guidelines and thereby facilitate clinical decision-making.

Understanding the benefits, limits, and mechanisms of change of AVAT is crucial to optimally apply and tailor it to different contexts and settings. Consequently, by better understanding this intervention, we could potentially increase its effectiveness and optimise its application, which would lead to improved patient outcomes. This would not only benefit each individual who is treated with AVAT, but also the health care provider, who could apply the intervention in its most efficient way, thereby using their resources optimally.

Furthermore, explorative findings regarding the characteristics of the treatment could generate new hypotheses for future RCTs, for example regarding the effectiveness of certain types of AVAT for specific treatment indications. Moreover, the emergence of certain patterns in effectiveness could inspire further research about possible mechanisms of change of AVAT.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Active visual art therapy

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols

Randomised controlled trial

Risk of Bias tool

Intention to treat

Per protocol

Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What’s in a name?: National Institutes of Health; 2018 [updated 07.2018]. Available from: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name . Accessed 5 Feb 2021.

Abbing A, Baars EW, de Sonneville L, Ponstein AS, Swaab H. The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adult women: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol. 2019;10(May):1203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01203 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ciasca EC, Ferreira RC, Santana CLA, Forlenza OV, Dos Santos GD, Brum PS, et al. Art therapy as an adjuvant treatment for depression in elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. Braz J Psychiatry. 2018;40(3):256–63. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2250 .

Lock J, Fitzpatrick KK, Agras WS, Weinbach N, Jo B. Feasibility study combining art therapy or cognitive remediation therapy with family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26(1):62–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2571 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Campbell M, Decker KP, Kruk K, Deaver SP. Art therapy and cognitive processing therapy for combat-related ptsd: a randomized controlled trial. Art Ther. 2016;33(4):169–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1226643 .

Article Google Scholar

O'Brien F. The making of mess in art therapy: attachment, trauma and the brain. Inscape. 2004;9(1):2–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02647140408405670 .

Deshmukh SR, Holmes J, Cardno A. Art therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018(9):CD011073. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011073.pub2 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fenton JF. Cystic fibrosis and art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2000;27(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4556(99)00015-5 .

Aguilar BA. The efficacy of art therapy in pediatric oncology patients: an integrative literature review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;36:173–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2017.06.015 .

Öster I, Svensk A-C, Magnusson EVA, Thyme KE, Sjodin M, Åström S, et al. Art therapy improves coping resources: a randomized, controlled study among women with breast cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4(1):57–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S147895150606007X .

Kim H, Kim S, Choe K, Kim J-S. Effects of mandala art therapy on subjective well-being, resilience, and hope in psychiatric inpatients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(2):167–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2017.08.008 .

Malchiodi CA. Calm, connection, and confidence: using art therapy to enhance resilience in traumatized children. In: Brooks, Goldstein S, editors. Play therapy interventions to enhance resilience; 2015. p. 126–45.

Google Scholar

Hong R-M, Guo S-E, Huang C-S, Yin C. Examining the effects of art therapy on reoccurring tobacco use in a taiwanese youth population: a mixed-method study. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(4):548–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1347184 .

Wood MJM, Molassiotis A, Payne S. What research evidence is there for the use of art therapy in the management of symptoms in adults with cancer? A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):135–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1722 .

Abdulah DM, Abdulla BMO. Effectiveness of group art therapy on quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2018;41:180–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.09.020 .

Hattori H, Hattori C, Hokao C, Mizushima K, Mase T. Controlled study on the cognitive and psychological effect of coloring and drawing in mild alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11(4):431–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00698.x .

Kongkasuwan R, Voraakhom K, Pisolayabutra P, Maneechai P, Boonin J, Kuptniratsaikul V. Creative art therapy to enhance rehabilitation for stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(10):1016–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215515607072 .

Blomdahl C, Gunnarsson AB, Guregård S, Björklund A. A realist review of art therapy for clients with depression. Arts Psychother. 2013;40(3):322–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2013.05.009 .

Abbing A, Ponstein A, van Hooren S, de Sonneville L, Swaab H, Baars E. The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: a systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208716. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716 .

Rajendran N, Mitra TP, Shahrestani S, Coggins A. Randomized controlled trial of adult therapeutic coloring for the management of significant anxiety in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(2):92–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13838 .

Attard A, Larkin M. Art therapy for people with psychosis: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(11):1067–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30146-8 .

Leckey J. The therapeutic effectiveness of creative activities on mental well-being: a systematic review of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(6):501–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01693.x .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Boehm K, Cramer H, Staroszynski T, Ostermann T. Arts therapies for anxiety, depression, and quality of life in breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/103297 .

Zhao J, Li H, Lin R, Wei Y, Yang A. Effects of creative expression therapy for older adults with mild cognitive impairment at risk of alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1313–20. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S161861 .

Czamanski-Cohen J, Wiley JF, Sela N, Caspi O, Weihs K. The role of emotional processing in art therapy (repat) for breast cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(5):586–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2019.1590491 .

Haeyen S, van Hooren S, van der Veld W, Hutschemaekers G. Efficacy of art therapy in individuals with personality disorders cluster b/c: a randomized controlled trial. J Personal Disord. 2018;32(4):527–42. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2017_31_312 .

Abbing A, de Sonneville L, Baars E, Bourne D, Swaab H. Anxiety reduction through art therapy in women. Exploring stress regulation and executive functioning as underlying neurocognitive mechanisms. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0225200. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225200 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rusted J, Sheppard L, Waller D. A multi-centre randomized control group trial on the use of art therapy for older people with dementia. Group Anal. 2006;39(4):517–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0533316406071447 .

Baker FA, Metcalf O, Varker T, O’Donnell M. A systematic review of the efficacy of creative arts therapies in the treatment of adults with ptsd. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2018;10(6):643–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000353 .

Bowen-Salter H, Whitehorn A, Pritchard R, Kernot J, Baker A, Posselt M, et al. Towards a description of the elements of art therapy practice for trauma: a systematic review. Int J Art Ther. 2021:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2021.1957959 .

Schnitzer G, Holttum S, Huet V. A systematic literature review of the impact of art therapy upon post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Art Ther. 2021;26(4):147–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2021.1910719 .

Schouten KA, De Niet GJ, Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ, Hutschemaekers GJM. The effectiveness of art therapy in the treatment of traumatized adults. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16(2):220–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014555032 .

Potash JS, Mann SM, Martinez JC, Roach AB, Wallace NM. Spectrum of art therapy practice: systematic literature review ofart therapy, 1983–2014. Art Ther. 2016;33(3):119–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1199242 .

Tang Y, Fu F, Gao H, Shen L, Chi I, Bai Z. Art therapy for anxiety, depression, and fatigue in females with breast cancer: a systematic review. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(1):79–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1506855 .

Kim KS, Loring S, Kwekkeboom K. Use of art-making intervention for pain and quality of life among cancer patients: a systematic review. J Holist Nurs. 2018;36(4):341–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010117726633 .

Scope A, Uttley L, Sutton A. A qualitative systematic review of service user and service provider perspectives on the acceptability, relative benefits, and potential harms of art therapy for people with non-psychotic mental health disorders. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract. 2017;90(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12093 .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1 (updated Sept 2020). Cochrane; 2020. Available from http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 .

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 .

Herbert JD, Gaudiano BA. Moving from empirically supported treatment lists to practice guidelines in psychotherapy: the role of the placebo concept. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61(7):893–908. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20133 .

Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf MI, et al. Chapter 4: searching for and selecting studies. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 61 (updated September 2020): Cochrane; 2020. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Wong SS, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound treatment studies in embase. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94(1):41–7.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cochrane Work. Embase. Available from: https://work.cochrane.org/embase . Accessed 8 Feb 2021.

Cochrane Work. Rct filters for different databases: The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from: https://work.cochrane.org/rct-filters-different-databases . Accessed 8 Feb 2021.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne: Veritas Health Innovation; https://www.covidence.org .

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898 .

Higgins JPT, Eldridge S, Li T. 23.2.3 assessing risk of bias in crossover trials. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 61 (updated September 2020): Cochrane; 2020. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. 8.2.2 specifying the nature of the effect of interest: ‘Intention-to-treat’ effects versus ‘per-protocol’ effects. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of Interventions version 61 (updated September 2020). Cochrane; 2020. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-08#section-8-2-2 .

Sambunjak D, Cumpston M, Watts C. Module 6: analysing the data Cochrane interactive learning: Cochrane; 2017. [updated 08.02.2021]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/interactivelearning/module-6-analysing-data.%0A%0A . Accessed May 2020

Higgins JPT, Eldridge S, Li T. 23.2.2 assessing suitability of crossover trials. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 61 (updated September 2020): Cochrane; 2020. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Higgins JPT, Eldridge S, Li T. 23.2.6 methods for incorporating crossover trials into a meta-analysis. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 61 (updated September 2020): Cochrane; 2020. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-23#section-23-2-6 .

Higgins JPT, Eldridge S, Li T. 23.2.4 using only the first period of a crossover trial. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 61 (updated September 2020): Cochrane; 2020. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-23#section-23-2-4 .

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE. Chapter 12: synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 60 (updated July 2019); 2019. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 10: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 61 (updated 2019); 2019. p. 241–84. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook .

Chapter Google Scholar

Montag C, Haase L, Seidel D, Bayerl M, Gallinat J, Herrmann U, et al. A pilot rct of psychodynamic group art therapy for patients in acute psychotic episodes: feasibility, impact on symptoms and mentalising capacity. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112348. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112348 .

Schouten KA, Van Hooren S, Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ, Hutschemaekers GJM. Trauma-focused art therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. J Trauma Dissociation. 2019;20(1):114–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2018.1502712 .

Schäfer I, Gast U, Hofmann A, Knaevelsrud C, Lampe A, Liebermann P, et al., editors. S3-leitlinie posttraumatische belastungsstörung. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 2019.

Download references

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study is investigator initiated.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute for Social Medicine, Epidemiology and Health Economics, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Luisenstr. 57, 10117, Berlin, Germany

Ronja Joschko, Stephanie Roll, Stefan N. Willich & Anne Berghöfer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RJ was responsible for the search strategy development and study protocol and manuscript preparation. SW, AB, and SR gave advice and feedback on the study planning and design, and the protocol, manuscript and search strategy development throughout the planning process. SR also assisted with selecting the appropriate statistical methods. RJ is the guarantor of the review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ronja Joschko .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

For this systematic review of published studies ethical approval is not necessary. Before the stakeholder interviews, which we consider as expert consultations, we will provide written information about the interview and will obtain an informed consent from each stakeholder.

Consent for publication

We will obtain a consent for publication from each stakeholder prior to the interview.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

PRISMA-P checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Joschko, R., Roll, S., Willich, S.N. et al. The effect of active visual art therapy on health outcomes: protocol of a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Syst Rev 11 , 96 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01976-7

Download citation

Received : 01 March 2021

Accepted : 06 May 2022

Published : 16 May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01976-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Creative therapy

- Therapy effectiveness evaluation

- Systematic review

- Mental health

- Psychosomatic disorders

- Quality of life

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

REVIEW article

Art therapy: a complementary treatment for mental disorders.

- 1 College of Creative Design, Shenzhen Technology University, Shenzhen, China

- 2 The Fourth Clinical Medical College of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Shenzhen, China

- 3 Institute of Biomedical and Health Engineering, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen, China

Art therapy, as a non-pharmacological medical complementary and alternative therapy, has been used as one of medical interventions with good clinical effects on mental disorders. However, systematically reviewed in detail in clinical situations is lacking. Here, we searched on PubMed for art therapy in an attempt to explore its theoretical basis, clinical applications, and future perspectives to summary its global pictures. Since drawings and paintings have been historically recognized as a useful part of therapeutic processes in art therapy, we focused on studies of art therapy which mainly includes painting and drawing as media. As a result, a total of 413 literature were identified. After carefully reading full articles, we found that art therapy has been gradually and successfully used for patients with mental disorders with positive outcomes, mainly reducing suffering from mental symptoms. These disorders mainly include depression disorders and anxiety, cognitive impairment and dementias, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, and autism. These findings suggest that art therapy can not only be served as an useful therapeutic method to assist patients to open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences, but also as an auxiliary treatment for diagnosing diseases to help medical specialists obtain complementary information different from conventional tests. We humbly believe that art therapy has great potential in clinical applications on mental disorders to be further explored.

Introduction

Mental disorders constitute a huge social and economic burden for health care systems worldwide ( Zschucke et al., 2013 ; Kenbubpha et al., 2018 ). In China, the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders was 24.20%, and 1-month prevalence of mental disorders was 14.27% ( Xu et al., 2017 ). The situation is more severely in other countries, especially for developing ones. Given the large numbers of people in need and the humanitarian imperative to reduce suffering, there is an urgent need to implement scalable mental health interventions to address this burden. While pharmacological treatment is the first choice for mental disorders to alleviate the major symptoms, many antipsychotics contribute to poor quality of life and debilitating adverse effects. Therefore, clinicians have turned toward to complementary treatments, such as art therapy in addressing the health needs of patients more than half a century ago.

Art therapy, is defined by the British Association of Art Therapists as: “a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its primary mode of expression and communication. Clients referred to art therapists are not required to have experience or skills in the arts. The art therapist’s primary concern is not to make an esthetic or diagnostic assessment of the client’s image. The overall goal of its practitioners is to enable clients to change and grow on a personal level through the use of artistic materials in a safe and convenient environment” ( British Association of Art Therapists, 2015 ), whereas as: “an integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families, and communities through active art-making, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psycho-therapeutic relationship” ( American Art Therapy Association, 2018 ) according to the American Art Association. It has gradually become a well-known form of spiritual support and complementary therapy ( Faller and Schmidt, 2004 ; Nainis et al., 2006 ). During the therapy, art therapists can utilize many different art materials as media (i.e., visual art, painting, drawing, music, dance, drama, and writing) ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ; Chiang et al., 2019 ). Among them, drawings and paintings have been historically recognized as the most useful part of therapeutic processes within psychiatric and psychological specialties ( British Association of Art Therapists, 2015 ). Moreover, many other art forms gradually fall under the prevue of their own professions (e.g., music therapy, dance/movement therapy, and drama therapy) ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ). Thus, we excluded these studies and only focused on studies of art therapy which mainly includes painting and drawing as media. Specifically, it focuses on capturing psychodynamic processes by means of “inner pictures,” which become visible by the creative process ( Steinbauer et al., 1999 ). These pictures reflect the psychopathology of different psychiatric disorders and even their corresponding therapeutic process based on specific rules and criterion ( Steinbauer and Taucher, 2001 ). It has been gradually recognized and used as an alternative treatment for therapeutic processes within psychiatric and psychological specialties, as well as medical and neurology-based scientific audiences ( Burton, 2009 ).

The development of art therapy comes partly from the artistic expression of the belief in unspoken things, and partly from the clinical work of art therapists in the medical setting with various groups of patients ( Malchiodi, 2013 ). It is defined as the application of artistic expressions and images to individuals who are physically ill, undergoing invasive medical procedures, such as surgery or chemotherapy for clinical usage ( Bar-Sela et al., 2007 ; Forzoni et al., 2010 ; Liebmann and Weston, 2015 ). The American Art Therapy Association describes its main functions as improving cognitive and sensorimotor functions, fostering self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivating emotional resilience, promoting insight, enhancing social skills, reducing and resolving conflicts and distress, and promoting societal and ecological changes ( American Art Therapy Association, 2018 ).

However, despite the above advantages, published systematically review on this topic is lacking. Therefore, this review aims to explore its clinical applications and future perspectives to summary its global pictures, so as to provide more clinical treatment options and research directions for therapists and researchers.

Publications of Art Therapy

The literatures about “art therapy” published from January 2006 to December 2020 were searched in the PubMed database. The following topics were used: Title/Abstract = “art therapy,” Indexes Timespan = 2006–2020.

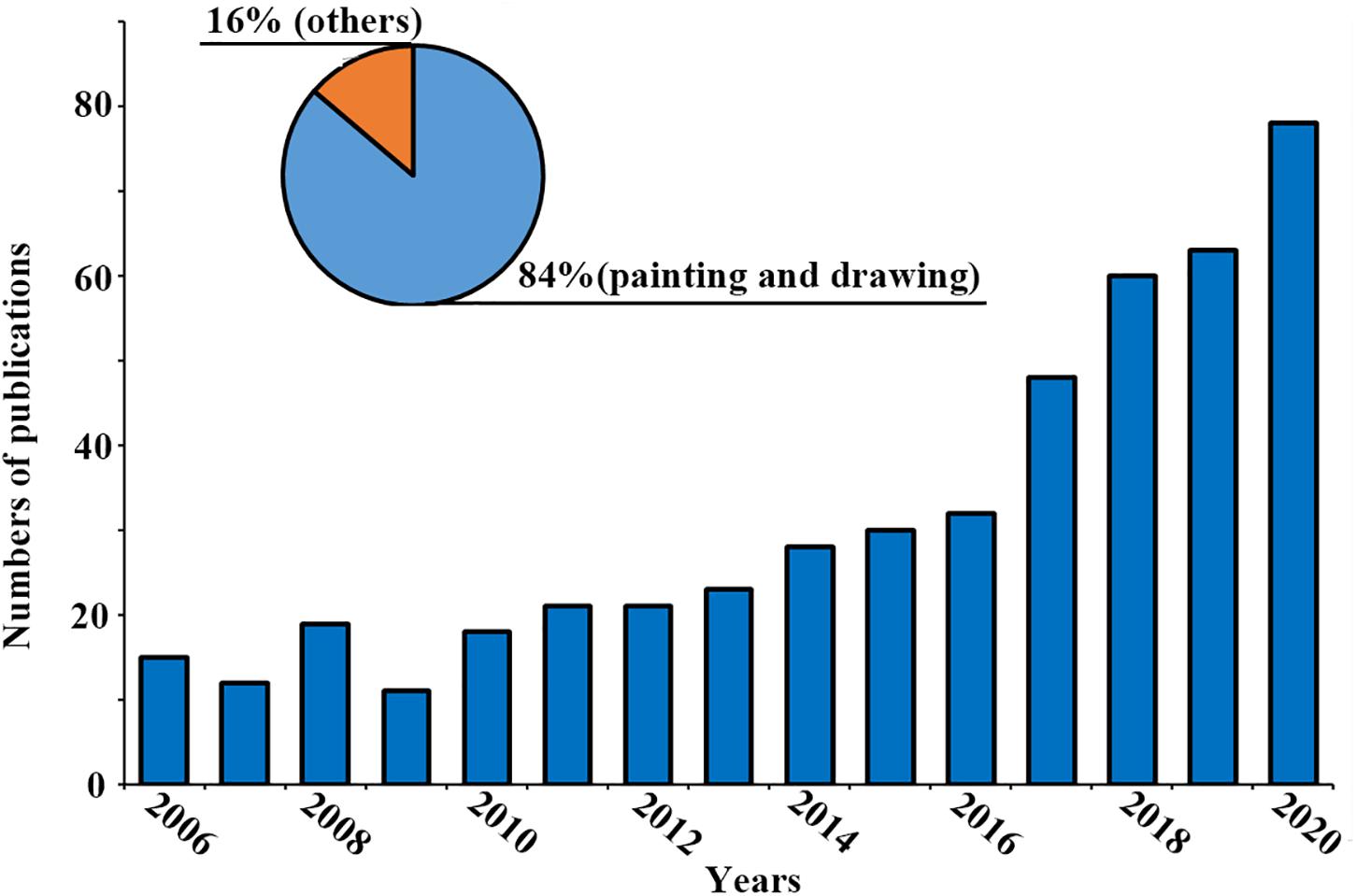

A total of 652 records were found. Then, we manually screened out the literatures that contained the word “art” but was not relevant with the subject of this study, such as state of the art therapy, antiretroviral therapy (ART), and assisted reproductive technology (ART). Finally, 479 records about art therapy were identified. Since we aimed to focus on art therapy included painting and drawing as major media, we screened out literatures deeper, and identified 413 (84%) literatures involved in painting and drawing ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Number of publications about art therapy.

As we can see, the number of literature about art therapy is increasing slowly in the last 15 years, reaching a peak in 2020. This indicates that more effort was made on this topic in recent years ( Figure 1 ).

Overview of Art Therapy

As defined by the British Association of Art Therapists, art therapy is a form of psychotherapy that uses art media as its primary mode of communication. Based on above literature, several highlights need to be summarized. (1) The main media of art therapy include painting, drawing, music, drama, dance, drama, and writing ( Chiang et al., 2019 ). (2) Main contents of painting and drawing include blind drawing, spiral drawing, drawing moods and self-portraits ( Legrand et al., 2017 ; Abbing et al., 2018 ; Papangelo et al., 2020 ). (3) Art therapy is mainly used for cancer, depression and anxiety, autism, dementia and cognitive impairment, as these patients are reluctant to express themselves in words ( Attard and Larkin, 2016 ; Deshmukh et al., 2018 ; Chiang et al., 2019 ). It plays an important role in facilitating engagement when direct verbal interaction becomes difficult, and provides a safe and indirect way to connect oneself with others ( Papangelo et al., 2020 ). Moreover, we found that art therapy has been gradually and successfully used for patients with mental disorders with positive outcomes, mainly reducing suffering from mental symptoms. These findings suggest that art therapy can not only be served as an useful therapeutic method to assist patients to open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences, but also as an auxiliary treatment for diagnosing diseases to help medical specialists obtain complementary information different from conventional tests.

Art Therapy for Mental Disorders

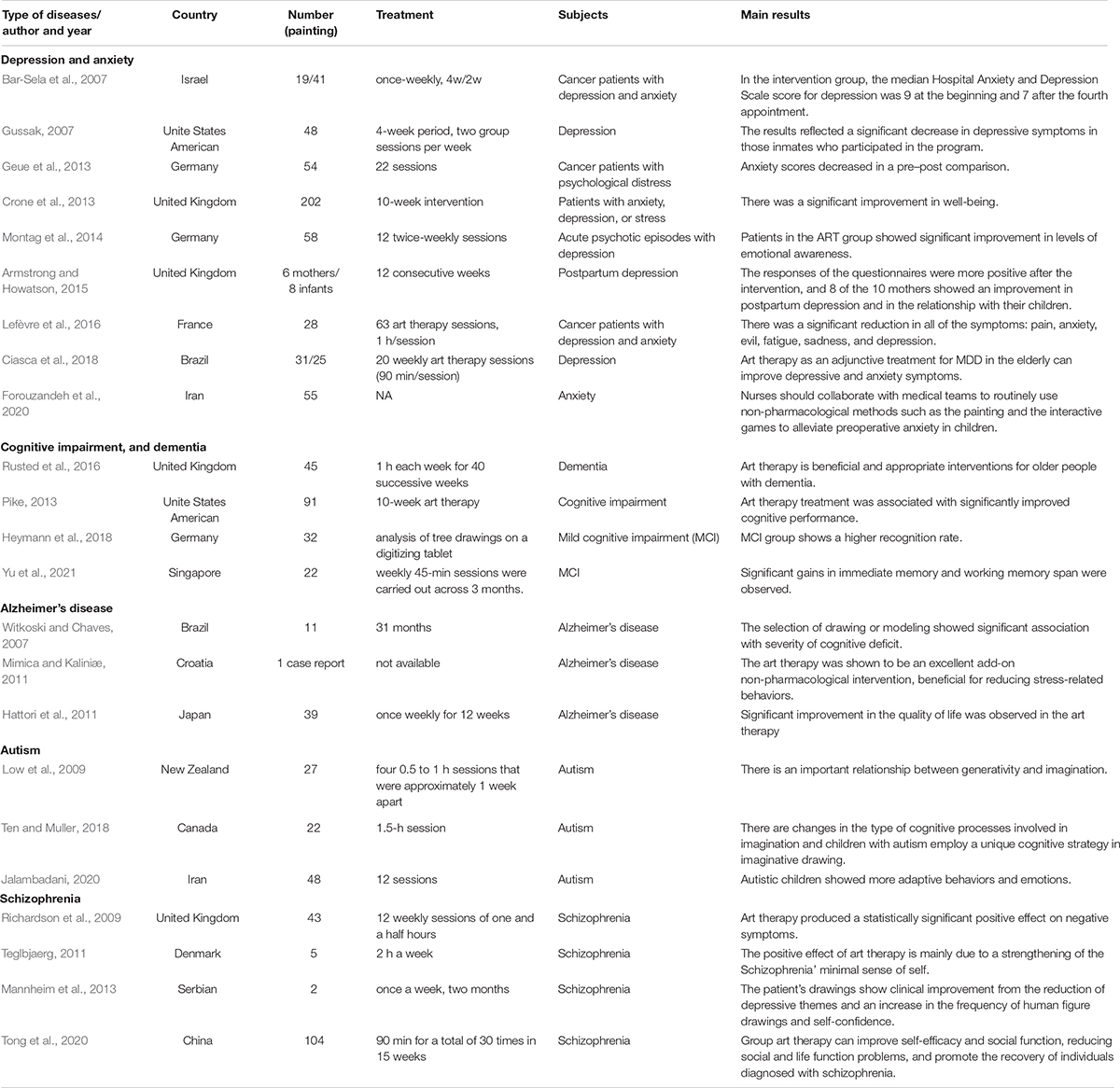

Based on the 413 searched literatures, we further limited them to mental disorders using the following key words, respectively: Depression OR anxiety OR Cognitive impairment OR dementia OR Alzheimer’s disease OR Autism OR Schizophrenia OR mental disorder. As a result, a total of 23 studies (5%) ( Table 1 ) were included and classified after reading the abstract and the full text carefully. These studies include 9 articles on depression and anxiety, 4 articles on cognitive impairment and dementia, 3 articles on Alzheimer’s disease, 3 articles on autism, and 4 articles on schizophrenia. In addition to the English literature, in fact, some Chinese literatures also described the application of art therapy in mental diseases, which were not listed but referred to in the following specific literatures.

Table 1. Studies of art therapy in mental diseases.

Depression Disorders and Anxiety

Depression and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent, affecting individuals, their families and the individual’s role in society ( Birgitta et al., 2018 ). Depression is a disabling and costly condition associated with a significant reduction in quality of life, medical comorbidities and mortality ( Demyttenaere et al., 2004 ; Whiteford et al., 2013 ; Cuijpers et al., 2014 ). Anxiety is associated with lower quality of life and negative effects on psychosocial functioning ( Cramer et al., 2005 ). Medication is the most commonly used effective way to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, nonadherence are crucial shortcomings in using antidepressant to treat depression and anxiety ( van Geffen et al., 2007 ; Nielsen et al., 2019 ).

In recent years, many studies have shown that art therapy plays a significant role in alleviating depression symptoms and anxiety. Gussak (2007) performed an observational survey about populations in prison of northern Florida and identified that art therapy significantly reduces depressive symptoms. Similarly, a randomized, controlled, and single-blind study about art therapy for depression with the elderly showed that painting as an adjuvant treatment for depression can reduce depressive and anxiety symptoms ( Ciasca et al., 2018 ). In addition, art therapy is also widely used among students, and several studies ( Runde, 2008 ; Zhenhai and Yunhua, 2011 ) have shown that art therapy also significantly reduces depressive symptoms in students. For example, Wang et al. (2011) conducted group painting therapy on 30 patients with depression for 3 months, and found that painting therapy could promote their social function recovery, improve their social adaptability and quality of life. Another randomized clinical trial also showed that it could decrease mean anxiety scores in the 3–12 year painting group ( Forouzandeh et al., 2020 ).

Studies have shown that distress, including anxiety and depression, is related to poorer health-related quality of life and satisfaction to medical services ( Hamer et al., 2009 ). Painting can be employed to express patients’ anxiety and fear, vent negative emotions by applying projection, thereby significantly improve the mood and reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety of cancer patients. A number of studies ( Bar-Sela et al., 2007 ; Thyme et al., 2009 ; Lin et al., 2012 ; Abdulah and Abdulla, 2018 ) showed that art therapy for cancer patients could enhance the vitality of patients and participation in social activities, significantly reduce depression, anxiety, and reduce stressful feelings. Importantly, even in the follow-up period, art therapy still has a lasting effect on cancer patients ( Thyme et al., 2009 ). Interestingly, art therapy based on famous painting appreciation could also significantly reduce anxiety and depression associated with cancer ( Lee et al., 2017 ). Among cancer patients treated in outpatient health care, art therapy also plays an important role in alleviating their physical symptoms and mental health ( Götze et al., 2009 ). Therefore, art therapy as an auxiliary treatment of cancer is of great value in improving quality of life.

Overall, art painting therapy permits patients to express themselves in a manner acceptable to the inside and outside culture, thereby diminishing depressed and anxiety symptoms.

Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia

Dementia, a progressive clinical syndrome, is characterized by widespread cognitive impairment in memory, thinking, behavior, emotion and performance, leading to worse daily living ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ). According to the Alzheimer’s Disease International 2015, there is 46.8 million people suffered from dementia, and numbers almost doubling every 20 years, rising to 131.5 million by 2050. Although art therapy has been used as an alternative treatment for the dementia for long time, the positive effects of painting therapy on cognitive function remain largely unknown. One intervention assigned older adults patients with dementia to a group-based art therapy (including painting) observed significant improvements in the clock drawing test ( Pike, 2013 ), whereas two other randomized controlled trials ( Hattori et al., 2011 ; Rusted et al., 2016 ) on patients with dementia have failed to obtain significant cognitive improvement in the painting group. Moreover, a cochrane systematic review ( Deshmukh et al., 2018 ) included two clinical studies of art therapy for dementia revealed that there is no sufficient evidence about the efficacy of art therapy for dementia. This may be because patients with severely cognitive impairment, who was unable to accurately remember or assess their own behavior or mental state, might lose the ability to enjoy the benefits of art therapy.

In summary, we should intervene earlier in patients with mild cognitive impairment, an intermediate stage between normal aging and dementia, in order to prevent further transformation into dementia. To date, mild cognitive impairment is drawing much attention to the importance of painting intervening at this stage in order to alter the course of subsequent cognitive decline as soon as possible ( Petersen et al., 2014 ). Recently, a randomized controlled trial ( Yu et al., 2021 ) showed significant relationship between improvement immediate memory/working memory span and increased cortical thickness in right middle frontal gyrus in the painting art group. With the long-term cognitive stimulation and engagement from multiple sessions of painting therapy, it is likely that painting therapy could lead to enhanced cognitive functioning for these patients.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a sub-type of dementia, which is usually associated with chronic pain. Previous studies suggested that art therapy could be used as a complementary treatment to relief pain for these patients since medication might induce severely side effects. In a multicenter randomized controlled trial, 28 mild AD patients showed significant pain reduction, reduced anxiety, improved quality of life, improved digit span, and inhibitory processes, as well as reduced depression symptoms after 12-week painting ( Pongan et al., 2017 ; Alvarenga et al., 2018 ). Further study also suggested that individual therapy rather than group therapy could be more optimal since neuroticism can decrease efficacy of painting intervention on pain in patients with mild AD. In addition to release chronic pain, art therapy has been reported to show positive effects on cognitive and psychological symptoms in patients with mild AD. For example, a controlled study revealed significant improvement in the apathy scale and quality of life after 12 weeks of painting treatment mainly including color abstract patterns with pastel crayons or water-based paint ( Hattori et al., 2011 ). Another study also revealed that AD patients showed improvement in facial expression, discourse content and mood after 3-weeks painting intervention ( Narme et al., 2012 ).

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a complex functional psychotic mental illness that affects about 1% of the population at some point in their life ( Kolliakou et al., 2011 ). Not only do sufferers experience “positive” symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, but also experience negative symptoms such as varying degrees of anhedonia and asociality, impaired working memory and attention, poverty of speech, and lack of motivation ( Andreasen and Olsen, 1982 ). Many patients with schizophrenia remain symptomatic despite pharmacotherapy, and even attempts to suicide with a rate of 10 to 50% ( De Sousa et al., 2020 ). For these patients, art therapy is highly recommended to process emotional, cognitive and psychotic experiences to release symptoms. Indeed, many forms of art therapy have been successfully used in schizophrenia, whether and how painting may interfere with psychopathology to release symptoms remains largely unknown.

A recent review including 20 studies overall was performed to summary findings, however, concluded that it is not clear whether art therapy leads to clinical improvement in schizophrenia with low ( Ruiz et al., 2017 ). Anyway, many randomized clinical trials reported positive outcomes. For example, Richardson et al. (2007) conducted painting therapy for six months in patients with chronic schizophrenia and found that art therapy had a positive effect on negative symptoms. Teglbjaerg (2011) examined experience of each patient using interviews and written evaluations before and after painting therapy and at a 1-year follow-up and found that group painting therapy in patients with schizophrenia could not only reduce psychotic symptoms, but also boost self-esteem and improve social function.

What’s more, the characteristics of the painting can also be used to judge the health condition in patients with schizophrenia. For example, Hongxia et al. (2013) explored the correlation between psychological health condition and characteristics of House-Tree-Person tests for patients with schizophrenia, and showed that the detail characteristic of the test results can be used to judge the patient’s anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Most importantly, several other studies showed that drug plus painting therapy significantly enhanced patient compliance and self-cognition than drug therapy alone in patients with schizophrenia ( Hongyan and JinJie, 2010 ; Min, 2010 ).

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental syndrome with no unified pathological or neurobiological etiology, which is characterized by difficulties in social interaction, communication problems, and a tendency to engage in repetitive behaviors ( Geschwind and Levitt, 2007 ).

Art therapy is a form of expression that opens the door to communication without verbal interaction. It provides therapists with the opportunity to interact one-on-one with individuals with autism, and make broad connections in a more comfortable and effective way ( Babaei et al., 2020 ). Emery (2004) did a case study about a 6-year-old boy diagnosed with autism and found that art therapy is of great value to the development, growth and communication skills of the boy. Recently, one study ( Jalambadani, 2020 ) using 40 children with ASD participating in painting therapy showed that painting therapy had a significant improvement in the social interactions, adaptive behaviors and emotions. Therefore, encouraging children with ASD to express their experience by using nonverbal expressions is crucial to their development. Evans and Dubowski (2001) believed that creating images on paper could help children express their internal images, thereby enhance their imagination and abstract thinking. Painting can also help autistic children express and vent negative emotions and thereby bring positive emotional experience and promote their self-consciousness ( Martin, 2009 ). According to two studies ( Wen and Zhaoming, 2009 ; Jianhua and Xiaolu, 2013 ) in China, Art therapy could also improve the language and communication skills, cognitive and behavioral performance of children with ASD.

Moreover, art therapy could be used to investigate the relationship between cognitive processes and imagination in children with ASD. One study ( Wen and Zhaoming, 2009 ; Jianhua and Xiaolu, 2013 ) suggested that children with ASD apply a unique cognitive strategy in imaginative drawing. Another study ( Low et al., 2009 ) examined the cognitive underpinnings of spontaneous imagination in children with ASD and showed that ASD group lacks imagination, generative ability, planning ability and good consistency in their drawings. In addition, several studies ( Leevers and Harris, 1998 ; Craig and Baron-Cohen, 1999 ; Craig et al., 2001 ) have been performed to investigate imagination and creativity of autism via drawing tasks, and showed impairments of autism in imagination and creativity via drawing tasks.

In a word, art therapy plays a significant role in children with ASD, not only as a method of treatment, but also in understanding and investigating patients’ problems.

Other Applications

In addition to the above mentioned diseases, art therapy has also been adopted in other applications. Dysarthia is a common sequela of cerebral palsy (CP), which directly affects children’s language intelligibility and psycho-social adjustment. Speech therapy does not always help CP children to speak more intelligibly. Interestingly, the art therapy can significantly improve the language intelligibility and their social skills for children with CP ( Wilk et al., 2010 ).

In brief, these studies suggest that art therapy is meaningful and accepted by both patients and therapists. Most often, art therapy could strengthen patient’s emotional expression, self-esteem, and self-awareness. However, our findings are based on relatively small samples and few good-quality qualitative studies, and require cautious interpretation.

The Application Prospects of Art Therapy

With the development of modern medical technology, life expectancy is also increasing. At the same time, it also brings some side effects and psychological problems during the treatment process, especially for patients with mental illness. Therefore, there is an increasing demand for finding appropriate complementary therapies to improve life quality of patients and psychological health. Art therapy is primarily offered as individual art therapy, in this review, we found that art therapy was most commonly used for depression and anxiety.

Based on the above findings, art therapy, as a non-verbal psychotherapy method, not only serves as an auxiliary tool for diagnosing diseases, which helps medical specialists obtain much information that is difficult to gain from conventional tests, judge the severity and progression of diseases, and understand patients’ psychological state from painting characteristics, but also is an useful therapeutic method, which helps patients open up and share their feelings, views, and experiences. Additionally, the implementation of art therapy is not limited by age, language, diseases or environment, and is easy to be accepted by patients.

Art therapy in hospitals and clinical settings could be very helpful to aid treatment and therapy, and to enhance communications between patients and on-site medical staffs in a non-verbal way. Moreover, art therapy could be more effective when combined with other forms of therapy such as music, dance and other sensory stimuli.

The medical mechanism underlying art therapy using painting as the medium for intervention remains largely unclear in the literature ( Salmon, 1993 ; Broadbent et al., 2004 ; Guillemin, 2004 ), and the evidence for effectiveness is insufficient ( Mirabella, 2015 ). Although a number of studies have shown that art therapy could improve the quality of life and mental health of patients, standard and rigorous clinical trials with large samples are still lacking. Moreover, the long-term effect is yet to be assessed due to the lack of follow-up assessment of art therapy.

In some cases, art therapy using painting as the medium may be difficult to be implemented in hospitals, due to medical and health regulations (may be partly due to potential of messes, lack of sink and cleaning space for proper disposal of paints, storage of paints, and toxins of allergens in the paint), insufficient space for the artwork to dry without getting in the way or getting damaged, and negative medical settings and family environments. Nevertheless, these difficulties can be overcome due to great benefits of the art therapy. We thus humbly believe that art therapy has great potential for mental disorders.

In the future, art therapy may be more thoroughly investigated in the following directions. First, more high-quality clinical trials should be carried out to gain more reliable and rigorous evidence. Second, the evaluation methods for the effectiveness of art therapy need to be as diverse as possible. It is necessary for the investigation to include not only subjective scale evaluations, but also objective means such as brain imaging and hematological examinations to be more convincing. Third, it will be helpful to specify the details of the art therapy and patients for objective comparisons, including types of diseases, painting methods, required qualifications of the therapist to perform the art therapy, and the theoretical basis and mechanism of the therapy. This practice should be continuously promoted in both hospitals and communities. Fourth, guidelines about art therapy should be gradually formed on the basis of accumulated evidence. Finally, mechanism of art therapy should be further investigated in a variety of ways, such as at the neurological, cellular, and molecular levels.

Author Contributions

JH designed the whole study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JZ searched for selected the studies. LH participated in the interpretation of data. HY and JX offered good suggestions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFC1712200), International standards research on clinical research and service of Acupuncture-Moxibustion (2019YFC1712205), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62006220), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Research Program (No. JCYJ20200109114816594).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbing, A., Ponstein, A., van Hooren, S., de Sonneville, L., Swaab, H., and Baars, E. (2018). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: a systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS One 13:e208716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abdulah, D. M., and Abdulla, B. (2018). Effectiveness of group art therapy on quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 41, 180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.09.020

Alvarenga, W. A., Leite, A., Oliveira, M. S., Nascimento, L. C., Silva-Rodrigues, F. M., Nunes, M. D. R., et al. (2018). The effect of music on the spirituality of patients: a systematic review. J. Holist. Nurs. 36, 192–204. doi: 10.1177/0898010117710855

American Art Therapy Association (2018). Definition of Art. Available online at: https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/

Google Scholar

Andreasen, N. C., and Olsen, S. (1982). Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 789–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290070025006

Armstrong, V. G., and Howatson, R. (2015). Parent-infant art psychotherapy: a creative dyadic approach to early intervention. Infant Ment. Health J. 36, 213–222. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21504

Attard, A., and Larkin, M. (2016). Art therapy for people with psychosis: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30146-8

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Babaei, S., Fatahi, B. S., Fakhri, M., Shahsavari, S., Parviz, A., Karbasfrushan, A., et al. (2020). Painting therapy versus anxiolytic premedication to reduce preoperative anxiety levels in children undergoing tonsillectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J. Pediatr. 88, 190–191. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03430-9

Bar-Sela, G., Atid, L., Danos, S., Gabay, N., and Epelbaum, R. (2007). Art therapy improved depression and influenced fatigue levels in cancer patients on chemotherapy. Psychooncology 16, 980–984. doi: 10.1002/pon.1175

Birgitta, G. A., Wagman, P., Hedin, K., and Håkansson, C. (2018). Treatment of depression and/or anxiety–outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of the tree theme method ® versus regular occupational therapy. BMC Psychol. 6:25. doi: 10.1186/s40359-018-0237-0

British Association of Art Therapists (2015). What is Art Therapy? Available online at: https://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy

Broadbent, E., Petrie, K. J., Ellis, C. J., Ying, J., and Gamble, G. (2004). A picture of health–myocardial infarction patients’ drawings of their hearts and subsequent disability: a longitudinal study. J. Psychosom. Res. 57, 583–587.

Burton, A. (2009). Bringing arts-based therapies in from the scientific cold. Lancet Neurol. 8, 784–785. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70216-9

Chiang, M., Reid-Varley, W. B., and Fan, X. (2019). Creative art therapy for mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 275, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.025

Ciasca, E. C., Ferreira, R. C., Santana, C.L. A., Forlenza, O. V., Dos Santos, G. D., Brum, P. S., et al. (2018). Art therapy as an adjuvant treatment for depression in elderly women: a randomized controlled trial. Braz. J. Psychiatry 40, 256–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2250

Craig, J., and Baron-Cohen, S. (1999). Creativity and imagination in autism and Asperger syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 319–326.

Craig, J., Baron-Cohen, S., and Scott, F. (2001). Drawing ability in autism: a window into the imagination. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 38, 242–253.

Cramer, V., Torgersen, S., and Kringlen, E. (2005). Quality of life and anxiety disorders: a population study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 193, 196–202. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000154836.22687.13

Crone, D. M., O’Connell, E. E., Tyson, P. J., Clark-Stone, F., Opher, S., and James, D. V. (2013). ‘Art Lift’ intervention to improve mental well-being: an observational study from U.K. general practice. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 22, 279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00862.x

Cuijpers, P., Vogelzangs, N., Twisk, J., Kleiboer, A., Li, J., and Penninx, B. W. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 453–462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030325

De Sousa, A., Shah, B., and Shrivastava, A. (2020). Suicide and Schizophrenia: an interplay of factors. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 22:65.

Demyttenaere, K., Bruffaerts, R., Posada-Villa, J., Gasquet, I., Kovess, V., Lepine, J. P., et al. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291, 2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581

Deshmukh, S. R., Holmes, J., and Cardno, A. (2018). Art therapy for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9:D11073.

Emery, M. J. (2004). Art therapy as an intervention for Autism. Art Ther. Assoc. 21, 143–147. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2004.10129500

Evans, K., and Dubowski, J. (2001). Art Therapy with Children on the Autistic Spectrum: Beyond Words. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 113.

Faller, H., and Schmidt, M. (2004). Prognostic value of depressive coping and depression in survival of lung cancer patients. Psychooncology 13, 359–363. doi: 10.1002/pon.783

Forouzandeh, N., Drees, F., Forouzandeh, M., and Darakhshandeh, S. (2020). The effect of interactive games compared to painting on preoperative anxiety in Iranian children: a randomized clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 40:101211. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101211

Forzoni, S., Perez, M., Martignetti, A., and Crispino, S. (2010). Art therapy with cancer patients during chemotherapy sessions: an analysis of the patients’ perception of helpfulness. Palliat. Support. Care 8, 41–48. doi: 10.1017/s1478951509990691

Geschwind, D. H., and Levitt, P. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: developmental disconnection syndromes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.009

Geue, K., Richter, R., Buttstädt, M., Brähler, E., and Singer, S. (2013). An art therapy intervention for cancer patients in the ambulant aftercare–results from a non-randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 22, 345–352. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12037

Götze, H., Geue, K., Buttstädt, M., Singer, S., and Schwarz, R. (2009). [Art therapy for cancer patients in outpatient care. Psychological distress and coping of the participants]. Forsch. Komplementmed. 16, 28–33.

Guillemin, M. (2004). Understanding illness: using drawings as a research method. Qual. Health Res. 14, 272–289. doi: 10.1177/1049732303260445

Gussak, D. (2007). The effectiveness of art therapy in reducing depression in prison populations. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 51, 444–460. doi: 10.1177/0306624x06294137

Hamer, M., Chida, Y., and Molloy, G. J. (2009). Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J. Psychosom. Res. 66, 255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.11.002

Hattori, H., Hattori, C., Hokao, C., Mizushima, K., and Mase, T. (2011). Controlled study on the cognitive and psychological effect of coloring and drawing in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 11, 431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00698.x

Heymann, P., Gienger, R., Hett, A., Müller, S., Laske, C., Robens, S., et al. (2018). Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease based on the patient’s creative drawing process: first results with a novel neuropsychological testing method. J. Alzheimers Dis. 63, 675–687. doi: 10.3233/jad-170946

Hongxia, M., Shuying, C., Chuqiao, F., Haiying, Z., Xuejiao, W., et al. (2013). Relationsle-title>Relationship between psychological state and house-tree-person drawing characteristics of rehabilitation patients with schizophrenia. Chin. Gen. Pract. 16, 2293–2295.

Relationship+between+psychological+state+and+house-tree-person+drawing+characteristics+of+rehabilitation+patients+with+schizophrenia%2E&journal=Chin%2E+Gen%2E+Pract%2E&author=Hongxia+M.&author=Shuying+C.&author=Chuqiao+F.&author=Haiying+Z.&author=Xuejiao+W.&publication_year=2013&volume=16&pages=2293–2295" target="_blank">Google Scholar

Hongyan, W., and JinJie, L. (2010). Rehabilitation effect of painting therapy on chronic schizophrenia. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 18, 1419–1420.

Jalambadani, Z. (2020). Art therapy based on painting therapy on the improvement of autistic children’s social interactions in Iran. Indian J. Psychiatry 62, 218–219. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_215_18