Solzhenitsyn Explains “Beauty Will Save the World”

The following is excerpted from Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel lecture, given in 1972.

Just as the savage in bewilderment picks up . . . a strange object cast up by the sea?. . . something long buried in the sand? . . . a baffling object fallen from the sky?—intricately shaped, now glistening dully, now reflecting a brilliant flash of light—just as he turns it this way and that, twirls it, searches for a way to utilize it, seeks to find for it a suitable lowly application, all the while not guessing its higher function . . .

So we also, holding Art in our hands, confidently deem ourselves its masters; we boldly give it direction, bring it up to date, reform it, proclaim it, sell it for money, use it to please the powerful, divert it for amusement—all the way down to vaudeville songs and nightclub acts—or else adapt it (with a muzzle or stick, whatever is handy) toward transient political or limited social needs. But art remains undefiled by our endeavors and the stamp of its origin remains unaffected: Each time and in every usage it bestows upon us a portion of its mysterious inner light.

But can we encompass the totality of this light? Who would dare to say that he has defined art? Or has enumerated all its aspects? Moreover, perhaps someone already did understand and did name them for us in the preceding centuries, but that could not long detain us; we listened briefly but took no heed; we discarded the words at once, hurrying—as always—to replace even the very best with something else, just so that it might be new. And when we are told the old once again, we won’t even remember that we used to have it earlier.

One artist imagines himself the creator of an autonomous spiritual world;he hoists upon his shoulders the act of creating this world and of populating it, together with the total responsibility for it. But he collapses under the load, for no mortal genius can bear up under it, just as, in general, the man who declares himself the center of existence is unable to create a balanced spiritual system. And if a failure befalls such a man, the blame is promptly laid to the chronic disharmony of the world, to the complexity of modern man’s divided soul, or to the public’s lack of understanding.

Another artist recognizes above himself a higher power and joyfully works as a humble apprentice under God’s heaven, though graver and more demanding still is his responsibility for all he writes or paints—and for the souls which apprehend it. However, it was not he who created this world, nor does he control it; there can be no doubts about its foundations. It is merely given to the artist to sense more keenly than others the harmony of the world, the beauty and ugliness of man’s role in it—and to vividly communicate this to mankind. Even amid failure and at the lower depths of existence— in poverty, in prison, and in illness—a sense of enduring harmony cannot abandon him.

But the very irrationality of art, its dazzling convolutions, its unforeseeable discoveries, its powerful impact on men—all this is too magical to be wholly accounted for by the artist’s view of the world, by his intention, or by the work of his unworthy fingers.

Archaeologists have yet to discover an early stage of human existence when we possessed no art. In the twilight preceding the dawn of mankind we received it from hands which we did not have a chance to see clearly. Neither had we time to ask: Why this gift for us? How should we treat it?

All those prognosticators of the decay, degeneration, and death of art were wrong and will always be wrong. It shall be we who die; art will remain. And shall we even comprehend before our passing all of its aspects and the entirety of its purposes?

Not everything can be named. Some things draw us beyond words. Art can warm even a chilled and sunless soul to an exalted spiritual experience. Through art we occasionally receive— indistinctly, briefly—revelations the likes of which cannot be achieved by rational thought

It is like that small mirror of legend: you look into it but instead of yourself you glimpse for a moment the Inaccessible, a realm forever beyond reach. And your soul begins to ache. . . .

Dostoyevsky once let drop an enigmatic remark: “Beauty will save the world.” What is this? For a long time it seemed to me simply a phrase. How could this be possible? When in the bloodthirsty process of history did beauty ever save anyone, and from what? Granted, it ennobled, it elevated—but whom did it ever save?

There is, however, a particular feature in the very essence of beauty—a characteristic trait of art itself: The persuasiveness of a true work of art is completely irrefutable; it prevails even over a resisting heart. A political speech, an aggressive piece of journalism, a program for the organization of society, a philosophical system, can all be constructed—with apparent smoothness and harmony—on an error or on a lie. What is hidden and what is distorted will not be discerned right away. But then a contrary speech, journalistic piece, or program, or a differently structured philosophy, comes forth to join the argument, and everything is again just as smooth and harmonious, and again everything fits. And so they inspire trust—and distrust.

In vain does one repeat what the heart does not find sweet.

But a true work of art carries its verification within itself: Artificial and forced concepts do not survive their trial by images; both image and concept crumble and turn out feeble, pale, and unconvincing. However, works which have drawn on the truth and which have presented it to us in concentrated and vibrant form seize us, attract us to themselves powerfully, and no one ever—even centuries later—will step forth to deny them.

So perhaps the old trinity of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty is not simply the decorous and antiquated formula it seemed to us at the time of our selfconfident materialistic youth. If the tops of these three trees do converge, as thinkers used to claim, and if the all too obvious and the overly straight sprouts of Truth and Goodness have been crushed, cut down, or not permitted to grow, then perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, and ever surprising shoots of Beauty will force their way through and soar up to that very spot , thereby fulfilling the task of all three.

And then no slip of the tongue but a prophecy would be contained in Dostoyevsky’s words: “Beauty will save the world.” For it was given to him to see many things; he had astonishing flashes of insight.

Could not then art and literature in a very real way offer succor to the modern world?

Who else but writers shall condemn their incompetent rulers (in some states this is in fact the easiest way to earn a living; it is done by anyone who feels the urge), who else shall censure their respective societies—be it for cowardly submission or for self-satisfied weakness—as well as the witless excesses of the young and the youthful pirates with knives upraised?

We shall be told: What can literature do in the face of a remorseless assault of open violence? But let us not forget that violence does not and cannot exist by itself: It is invariably intertwined with the lie. They are linked in the most intimate, most organic and profound fashion: Violence cannot conceal itself behind anything except lies, and lies have nothing to maintain them save violence. Anyone who has once proclaimed violence as his method must inexorably choose the lie as his principle. At birth, violence acts openly and even takes pride in itself. But as soon as it gains strength and becomes firmly established, it begins to sense the air around it growing thinner; it can no longer exist without veiling itself in a mist of lies, without concealing itself behind the sugary words of falsehood. No longer does violence always and necessarily lunge straight for your throat; more often than not it demands of its subjects only that they pledge allegiance to lies, that they participate in falsehood.

The simple act of an ordinary brave man is not to participate in lies, not to support false actions! His rule: Let that come into the world, let it even reign supreme—only not through me. But it is within the power of writers and artists to do much more: to defeat the lie! For in the struggle with lies art has always triumphed and shall always triumph! Visibly, irrefutably for all! Lies can prevail against much in this world, but never against art.

This is why I believe, my friends, that we are capable of helping the world in its hour of crisis. We should not seek to justify our unwillingness by our lack of weapons, nor should we give ourselves up to a life of comfort. We must come out and join the battle!

The favorite proverbs in Russian are about truth . They forcefully express a long and difficult national experience, sometimes in striking fashion:

One word of truth shall outweigh the whole world .

It is on such a seemingly fantastic violation of the law of conservation of mass and energy that my own activity is based, and my appeal to the writers of the world.

The Russian writer and Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn spent time in the Soviet gulag and pursued the life of an underground writer until he was catapulted to international fame with the unexpected publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in 1962. Get the rest of his Nobel lecture, in addition to his stories, poems, essays, and speeches, in the comprehensive The Solzhenitsyn Reader .

Get the Collegiate Experience You Hunger For

Your time at college is too important to get a shallow education in which viewpoints are shut out and rigorous discussion is shut down.

Explore intellectual conservatism Join a vibrant community of students and scholars Defend your principles

Join the ISI community. Membership is free.

J.D. Vance on our Civilizational Crisis

J.D. Vance, venture capitalist and author of Hillbilly Elegy, speaks on the American Dream and our Civilizational Crisis....

In Memoriam: Gerald J. Russello (1971-2021)

Remembering a prominent ISI alumnus

In Memoriam: Angelo Codevilla (1943–2021)

Donate to the linda l. bean conference center.

Donate to renew America’s Roots

- Account icon Log in

- Paper Goods

Beauty will save the world

“Beauty will save the world” - Dostoevsky

Alexander Solzhenitsyn also wrestled with this line in his 1970 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, and we're lucky to be privy to his chain of thought here:

"One day Dostoevsky threw out the enigmatic remark: “Beauty will save the world”. What sort of a statement is that? For a long time I considered it mere words. How could that be possible? When in bloodthirsty history did beauty ever save anyone from anything? Ennobled, uplifted, yes – but whom has it saved? There is, however, a certain peculiarity in the essence of beauty, a peculiarity in the status of art: namely, the convincingness of a true work of art is completely irrefutable and it forces even an opposing heart to surrender. It is possible to compose an outwardly smooth and elegant political speech, a headstrong article, a social program, or a philosophical system on the basis of both a mistake and a lie. What is hidden, what distorted, will not immediately become obvious. Then a contradictory speech, article, program, a differently constructed philosophy rallies in opposition – and all just as elegant and smooth, and once again it works. Which is why such things are both trusted and mistrusted. In vain to reiterate what does not reach the heart. But a work of art bears within itself its own verification: conceptions which are devised or stretched do not stand being portrayed in images, they all come crashing down, appear sickly and pale, convince no one. But those works of art which have scooped up the truth and presented it to us as a living force – they take hold of us, compel us, and nobody ever, not even in ages to come, will appear to refute them. So perhaps that ancient trinity of Truth, Goodness and Beauty is not simply an empty, faded formula as we thought in the days of our self-confident, materialistic youth? If the tops of these three trees converge, as the scholars maintained, but the too blatant, too direct stems of Truth and Goodness are crushed, cut down, not allowed through – then perhaps the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected stems of Beauty will push through and soar TO THAT VERY SAME PLACE, and in so doing will fulfil the work of all three? In that case Dostoevsky’s remark, “Beauty will save the world”, was not a careless phrase but a prophecy? After all HE was granted to see much, a man of fantastic illumination. And in that case art, literature might really be able to help the world today? It is the small insight which, over the years, I have succeeded in gaining into this matter that I shall attempt to lay before you here today."

You can read the rest of his speech at NobelPrize.org

Dostoevsky, Solzenhitsyn and the current state of the world collectively inspired this illustration . We wanted to capture a sense of individuals connecting to a whole that is greater than the parts. Points of light suggest a globe at sunrise, then connect through sunrise into the shape of a magnolia flower.

Checkmark icon Added to your cart:

Can Beauty Save the World?

Dostoyevsky once let drop the enigmatic phrase: “Beauty will save the world.” What does this mean? For a long time it used to seem to me that this was a mere phrase. Just how could such a thing be possible? When had it ever happened in the bloodthirsty course of history that beauty had saved anyone from anything? Beauty had provided embellishment certainly, given uplift—but whom had it ever saved?

However, there is a special quality in the essence of beauty, a special quality in the status of art: the conviction carried by a genuine work of art is absolutely indisputable and tames even the strongly opposed heart. One can construct a political speech, an assertive journalistic polemic, a program for organizing society, a philosophical system, so that in appearance it is smooth, well structured, and yet it is built upon a mistake, a lie; and the hidden element, the distortion, will not immediately become visible. And a speech, or a journalistic essay, or a program in rebuttal, or a different philosophical structure can be counterposed to the first—and it will seem just as well constructed and as smooth, and everything will seem to fit. And therefore one has faith in them—yet one has no faith.

It is vain to affirm that which the heart does not confirm. In contrast, a work of art bears within itself its own confirmation: concepts which are manufactured out of whole cloth or overstrained will not stand up to being tested in images, will somehow fall apart and turn out to be sickly and pallid and convincing to no one. Works steeped in truth and presenting it to us vividly alive will take hold of us, will attract us to themselves with great power- and no one, ever, even in a later age, will presume to negate them. And so perhaps that old trinity of Truth and Good and Beauty is not just the formal outworn formula it used to seem to us during our heady, materialistic youth. If the crests of these three trees join together, as the investigators and explorers used to affirm, and if the too obvious, too straight branches of Truth and Good are crushed or amputated and cannot reach the light—yet perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, unexpected branches of Beauty will make their way through and soar up to that very place and in this way perform the work of all three.

And in that case it was not a slip of the tongue for Dostoyevsky to say that “Beauty will save the world,” but a prophecy. After all, he was given the gift of seeing much, he was extraordinarily illumined.

And consequently perhaps art, literature, can in actual fact help the world of today.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: What does Beauty mean to you? Can you share a story that illustrates Beauty also performing the work of Truth and Good? What practice helps you bring this Beauty into your work and life?

Add Your Reflection

6 past reflections.

On Aug 18, 2020 olivia wrote :

Post your reply, on oct 28, 2017 marc wrote :.

This question will generate a different answer from different people, but perhaps beauty is something that invites us to rise up beyond what we thought possible, because it speaks truth. I am a huge fan of music, and I tend to listen for beauty in music, which is to say that I like to feel that the artist is expressing what is truth to him/her. I have also read books that are beautiful. I try to bring this beauty into my work and life by remembering to be true to my values and ideals. This is often a challenge, since many forces pull us in directions that encourage us to be someone else, but when I can remember, it is empowering to feel this beauty.

On Feb 3, 2016 Ramesh Narayan wrote :

What did Dostoyevsky mean by Beauty? Beauty is a very relative term. What is beautiful for me might not be so for someone else. Everyone has his or her own definition of beauty. Beautiful eyes, beautiful face, beautiful grace, beautiful body language, beautiful occasion, beautiful nature, beautiful morning, beautiful crowd, beautiful music, beautiful this, beautiful that.....Yes, beauty is certainly a blend of truth, good and many more things that are beautiful.

On Dec 15, 2015 Craig wrote :

I feel that there is a truth to what Dostoyevsky said, but that it is far more esoteric than what Solzhenitsyn has written about here. My sense is that Beauty resonates with us in a way that is beyond the intellectual mind, under the table of the ego. As Rashimi wrote, Beauty pulls us toward it perhaps because it reminds us that we are one with it already; Beauty tickles our hearts in that place where we are not separate from anything. I felt a bit saddened reading this piece. Did Solzhenitsyn contradict his meaning with his form? To my ear, the way he expressed his ideas did not sing or dance. Where did the poetry go? Was his beauty was lost in translation? Or is beauty so relative, as David has suggested, that another reader found beauty here that I missed, because I did not have the ears to hear it? I will continue to ponder the notion that untrue ideas cannot fit into a beautiful form—yet I see an attempt to convey that very thing in advertising on a daily basis. And many of us are hooked by it, seduced... The ancient Hindu story of the Churning of the Ocean of Milk is a wonderful story to study when we wish to look at the place, the need, and the power of Beauty. It's a tale of how Beauty did save the world. In that myth, Divinity alternates between manifesting and hiding, between the numinous and the seductive, found among the perceptual world—then hopelessly lost—and only recovered again by going deep, deep within.

On Dec 15, 2015 Rashmi wrote :

Beauty certainly pulls me towards it.

On Dec 13, 2015 david doane wrote :

(Curious that I seem to struggle more with what to say about this topic than with any topic so far.) For me, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, or more accurately, in the soul of the beholder. Beauty is that which catches my attention and touches my soul in a positive way, and I feel some amount of awe, joy, and appreciation. There is a Greek saying that a thing of beauty is a joy forever. Beauty stimulates my senses and imagination, and I am caught up in it, present to it and with it and disconnected from other realities of life for a few or many moments. For me, an example of Beauty is a ballerina performing impeccably with grace and balance which simultaneously opens me to the impeccable grace and balance of Truth and Good. The practice of being in the present, seeing and responding to what is happening brings Beauty into my work and life. I suppose what appears as beauty pulls out a sliver of Beauty that is in the beholder.

- BIOGRAPHIES

Home » Beauty will save the world – Fyodor Dostoevsky

Beauty will save the world – Fyodor Dostoevsky

What is the Meaning of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Quote: “Beauty will save the world”?

In the realm of literature and philosophical musings, Fyodor Dostoevsky, the renowned Russian author, left behind a powerful quote that has captivated readers and thinkers for generations. The quote, “Beauty will save the world,” holds deep meaning and invites us to explore the profound implications it carries. This article aims to unravel the essence of this enigmatic statement, delving into its various interpretations and shedding light on its significance.

The Context of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Quote

Fyodor Dostoevsky, known for his profound and introspective writings, included the quote “Beauty will save the world” in his novel “ The Idiot “. The novel explores the complexities of human nature and the contrast between the inherent beauty of the protagonist’s soul and the corrupted world surrounding him. Within this context, the quote becomes a beacon of hope, suggesting that beauty possesses the potential to bring salvation and transform the world.

The Interpretations of Beauty

Beauty as aesthetic pleasure.

One interpretation of Dostoevsky’s quote focuses on beauty as a source of aesthetic pleasure. In this view, beauty, whether found in nature, art, or human actions, has the power to evoke deep emotional responses. It transcends the mundane and touches the core of our being, lifting our spirits and reminding us of the inherent goodness and harmony in the world.

Beauty as Moral Transformation

Another interpretation sees beauty as a catalyst for moral transformation. According to this perspective, experiencing beauty awakens our inner virtues and inspires us to pursue higher ideals. The encounter with beauty prompts introspection and encourages us to align our actions with principles such as compassion, empathy, and justice.

Beauty as Redemption

A more profound interpretation suggests that beauty serves as a means of redemption. It implies that the transformative power of beauty can restore individuals and societies, healing the wounds inflicted by the darkness and suffering that often pervade the world. Beauty, in this sense, becomes a force that leads to salvation and renewal.

Beauty and its Relationship with the World

Dostoevsky’s quote hints at the interconnectedness between beauty and the world. It suggests that the world, with its struggles and imperfections, can find solace and redemption through encounters with beauty. By appreciating and nurturing beauty, we become agents of change, fostering harmony and inspiring others to embrace a more profound understanding of life.

Beauty’s Power to Inspire Change

Individual transformation.

Beauty has the power to transform individuals from within. When we encounter something truly beautiful, whether it’s a captivating piece of art, a breathtaking landscape, or an act of kindness, it can deeply touch our souls. These experiences have the potential to awaken dormant aspirations, reshape our perspectives, and drive us towards personal growth and self-improvement.

Societal Transformation

Furthermore, beauty can catalyze societal transformation. Throughout history, art, literature, and music have sparked revolutions, challenged societal norms, and fostered cultural progress. By appealing to the universal sense of beauty, creators can inspire collective action and ignite movements that bring positive change to the world.

The Role of Art in Manifesting Beauty

Art plays a pivotal role in manifesting beauty and conveying its transformative power. Whether through paintings, sculptures, literature, or music, artists capture the essence of beauty and offer it to the world. Through their creations, they provoke emotions, encourage introspection, and challenge conventional wisdom. Moreover, all these efforts are in service of revealing the profound truths and the redemptive potential of beauty.

Challenges and Critiques

Despite the profound message conveyed by Dostoevsky’s quote, it also faces challenges and critiques. Skeptics argue that beauty alone cannot solve the complex problems and conflicts of the world. They contend that practical actions, grounded in ethics and reason, are necessary to effect lasting change. However, proponents of Dostoevsky’s view assert that beauty serves as a catalyst, inspiring and nurturing the virtues needed to navigate the challenges we face.

The Timelessness of Dostoevsky’s Quote

Dostoevsky’s quote continues to resonate across time and cultures because it taps into the universal longing for meaning and redemption. It reminds us that amidst the chaos and suffering in the world, beauty holds the power to inspire, transform, and save. Regardless of its various interpretations, the essence of the quote lies in its capacity to evoke a deep sense of hope and a call to action.

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s quote, “Beauty will save the world,” encapsulates a profound truth that transcends time and space. It invites us to recognize the transformative power of beauty in our lives and in the world around us. Whether through aesthetic pleasure, moral transformation, or societal change, beauty has the capacity to elevate our existence and bring about redemption. Let us embrace and nurture beauty in all its forms, knowing that by doing so, we become active participants in the salvation of the world.

Dive into Fyodor Dostoevsky’s profound quotes, exploring the depths of human existence

Must Read Books by Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Crime and Punishment

- Notes from Underground

Right or wrong, it’s very pleasant to break something from time to time – Fyodor Dostoevsky

To love someone means to see them as god intended them – fyodor dostoevsky, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Follow us on instagram

Book Review: Beauty Will Save the World

If the too obvious, so straight branches of Truth and Good are crushed or amputated and cannot reach the light – yet perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, unexpected branches of Beauty will make their way through and soar up to that very place and in this way perform the work of all three. And in that case it was not a slip of the tongue for Dostoevsky to say that ‘Beauty will save the world’, but a prophecy.” Inspired by these words from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Laureate lecture, Gregory Wolfe’s book, Beauty Will Save the World, is an extended meditation on the soteriological significance of beauty. The book comprises a series of essays organized in five parts. Parts One and Two constitute the theoretical foundation of the book, while Parts Three to Five are devoted to a survey of writers, poets, and artists who embody the theoretical insights specific to Christian humanism.

Part One, “From Ideology to Humanism,” recounts Wolfe’s aesthetic journey from right wing politics to editor of a journal devoted to the analysis of art and culture. Having graduated from Hillsdale, where he sat in the classrooms of Russell Kirk and Gerhart Niemeyer, Wolfe began his professional career with National Review during the time of the Reagan Revolution in the early 1980s, only to find an irreconcilable dissonance between the spiritual and intellectual depths of the Western tradition and those who purported to defend that tradition in the political arena. Wolfe found increasingly that modern politics constituted an economy of power and coercion that affected corrosively the aesthetic nature of classical humanism. Eventually, Wolfe turned to a different state of affairs, one constituted by culture and art, which operated according to the grace of beauty and imagination. Here, in this aesthetic economy, one acts not in response to the consequentialism and compulsion inherent in statist practices, but rather according to the physics of beauty, the attraction that awakens wonder and draws one to encounter divine life through the evoking of a moral imagination.

Wolfe began to see the contemporary conservative political movement as a microcosm of a larger cultural crisis that centered on the loss of the metaphysical and transcendent. Citing Elaine Scarry, he notes that if the metaphysical realm has vanished, “one may feel bereft not only because of the giant deficit left by that vacant realm but because the girl, the bird, the vase, the book now seem unable in their solitude to justify or account for the weight of their own beauty. If each calls out for attention that has no destination beyond itself, each seems more self- centered, too fragile to support the gravity of our immense regard” (15). This is coupled with the observation of Hans Urs von Balthasar, who noted that the modern age has pursued the quest for truth and goodness at the expense of beauty and, as a result, has lost the primary agency of love. Wolfe concludes: “Taken together, these two statements suggest not only the enormous challenges facing our politicized society, but also the possibility of a theological aesthetic that can heal and unite” (15).

With the loss of beauty as an objective value, like truth and goodness, the American West has increasingly turned to power in order to influence cultural outcomes, resulting in the so-called ‘culture wars’. The problem here, as Wolfe observes, is that politics was appropriated classically as growing out of culture, not determinative of it. Said differently, liturgy, art, music, education, and science were properly basic to politics, such that the power of the state was relativized to and shaped by a collective moral imagination gifted to humans by God to perceive the divinely-infused meaning of the cosmos.

Reflecting on and contributing to the formative nature of culture was the task of the classical Christian humanist, who conceived of culture as the point of integration between the social and the transcendent, where eternal values are made palpable and substantial within the nexus of social practices. Quoting Virgil Nemoianu: “Culture is seen as a kind of tumbling ground for the spiritual, the social, the historical and the psychological…. the human being individually, and the human species collectively, act as a key, as the intersectional locus where all areas of the cosmos can meet … According to [the Christian humanists], aesthetic culture is that which seeks to articulate the opening toward transcendence that appears as a human constant in all human societies known to us” (34). Culture in the classical sense, as differentiated from the more mechanistic modern socio-anthropological sense, involves the development, nourishment, and exercise of what makes us distinctly human, namely, the embodiment of the Socratic trinity: the true, the good, and the beautiful.

For Wolfe, at the heart of this project is a sacramental vision of art. “To the Christian humanist, culture and art can become analogues for the Incarnation: a union of form and content, the inherence of divine meaning in the crafted materials of this earth” (45). He cites David Jones who writes in his essay, “Art and Sacrament,” that the Eucharist, consisting of culturally transformed grain and fruit, is the foundry for a sanctified and redeemed culture. And because culture is that which nourishes our humanity, the redemption of culture reciprocally fosters sanctified senses and souls. In the words of the art historian Hans Rookmaaker: “Christ didn’t come to make us Christians. He came to make us fully human” (46).

In Part Two of the work, “Christianity, Literature, and Modernity,” Wolfe maps out how such a Christian humanism can effectively engage a world constituted by secular modernity. Wolfe highlights several Catholic writers who seek to recover the sacred in the modern context, that is, a new vision of the transcendent that reveals itself through the frames of reference specific to the modern age. For example, Walker Percy’s last novel, The Thanatos Syndrome, depicts a futuristic world where human free will has been superseded by a scientific elite that manipulate the masses through dumping quantities of heavy sodium isotope in the water supply. When confronted on the devastating effects of heavy sodium on cortical function, the lead scientist defends his experiment:

What would you say, Tom … if I gave you a magic wand you could wave over there [Baton Rouge and New Orleans] and overnight you could reduce crime in the streets by eighty-seven percent…. Teenage suicide by ninety-five percent…. Teenage pregnancy by eighty-five percent…. (68)

Percy’s novel thus probes how the modern age has combined intellectual brilliance with unprecedented brutality: the key to comfort, peace, and security is the elimination of human free will. “The twist to this arrangement, which the Devil is careful not to divulge, is that by reducing man to the level of cattle – taking away the sacred dignity of human personhood – men become as expendable as cattle” (69).

In Part Three, “Six Writers,” Wolfe highlights the work of Evelyn Waugh, Shusako Endo, Geoffrey Hill, Andrew Lytle, Wendell Berry, and Larry Woiwode. Wolfe’s analysis of the latter three, who share an affinity with the great Southern Agrarian writers such as Allen Tate and William Faulkner, is particularly penetrating. Lytle, one of the “Twelve Southerners” who defended the South’s traditional agrarian culture in the 1930 publication, I’ll Take My Stand, believed that historical consciousness is inseparable from attachment to place and family. Wolfe writes: “For Lytle, the essence of Christendom is the family: it provides us with identity and schools us in love and self- sacrifice. Modernity, on the other hand, is characterized by the desire for power, a lust which leads man to wander, alone, separated from the community in the monstrosity of his ego. Technology without limits, the secular welfare state, the arts dominated by pornography and neurosis – all these are the effects of power without love, the individual without community” (143). In the writings of Berry and Woiwode, the distinctly sacramental vision of the landscape awakens the moral imagination to the ways in which the land mediates a quality beyond itself. Wolfe contrasts such a vision with the relation of a technician to nature, which is one of power and manipulation, and thus represents a fundamentally different economy than that constituted by the reciprocal love between the gardener and his garden. “It is not without significance,” Wolfe observes, “that the gardener is usually on his knees” (166).

In Part Four, “Three Artists,” Wolfe takes us past those who are satisfied with lamenting over the loss of classical Christian culture (‘declinists’, he calls them) and into an encounter with artists who have embraced the redemptive possibilities of modern art, such as Mary McCleary, Fred Folsom, and Makoto Fujimura. His analysis of Folsom’s Last Call (at the Shepherd Park Go-Go Club) is nothing less than Taboric. Wolfe’s exegesis transfigures a painting of a strip-tease scene into a sacred encounter with the grace of God: “Her [the stripper’s] arms are in the process of lifting up to an outstretched position, an implicit crucifixion …. In the lower left corner sits Pascal. Moving across the baseline we come to Folsom himself, almost directly underneath the stripper. Following his pointing hand we come to the lower right corner … which presents us with the wounded hand holding a glass of wine… It is the hand of the one who issues the ‘last call’ to all of us” (190).

The book concludes with Part Five, “Four Men of Letters,” where Wolfe surveys the contributions of Russell Kirk, Gerhart Niemeyer, Malcolm Muggeridge, and Marion Montgomery. Kirk and Niemeyer are singled out for their contributions to the moral imagination. “There is no more pressing need,” Wolfe writes, “in the moral and spiritual crisis of our time than the need to recover the imagination.” (206). For Kirk, inspired by Edmund Burke, the moral imagination is constituted by a symbolic universe where the images recorded by the senses are stored in our memory and are in turn constructed into analogies, metaphors and paradigms by which the totality of our experience can be synthesized and expressed in a coherent intellectual, moral, and spiritual life. In short, the moral imagination is the means by which we commune with divinely-infused meaning in our human experience and conform our lives accordingly.

If there is a refrain throughout this catena of essays, it would be that of invitation, for this is the nature of the soteriological significance of beauty. It has long been recognized that the Greek term for beauty, kalon, is related to the verb kalein, ‘to call’. Beauty is the effulgent or illuminative manifestation of the loveliness, the delectableness, the delightfulness of the true and the good, which awakens eros or a loving desire within the human person. Thus, beauty serves the indispensable role of momentum or motivation in intellectual, moral and spiritual pursuits, which stands in stark contrast to the coercion and manipulation inherent in political power. Wolfe’s essays are a collection of exhortations calling us to jettison our ideological abstractions and instead embrace a sacramental imagination that through a sanctified culture lifts us up into an indissoluble union with the divine source of life. With Beauty For Truth’s Sake, we encounter the redeeming nature of art and are thereby reminded that regardless of the secular eclipse of truth and goodness, beauty still shines through.

Archangels, Architect, and the Passion of Making

Comments are closed.

- Find a School

- Accreditation

- Academic Leadership

- Gordon Masters

- Summer Conference

- Fall Retreat

- East Coast Symposium

- West Coast Leaders Retreat

Career Center

- Privacy Policy

(833) 829-5935

Regional Office: 3400 Brook Road, Richmond, VA 23227

Office Hours: MON-FRI 9-4 Ct

© 2024 Society for Classical Learning. All Rights Reserved. GOOD Agency | Streamlined Digital Expertise Full Service Marketing ✦ Websites ✦ Video Production

- West Coast Leaders’ Retreat

EARLY BIRD ENDS MAY 1ST

Summer Conference 2024 - National Harbor, Maryland

Join us for a gathering of classical Christian educators from around the world as we consider what it means to build school communities and welcome the outside through biblical hospitality.

As a member, you receive access to all of the most recent summer conference content, including 80+ workshops, plenary speakers, etc., plus access to the full library of past content.

Conference Sessions

Ensure increased visibility for your school by having it listed on the Find a School Map, connecting you with potential students and families seeking a classical Christian learning environment.

Map Feature

Unlock a wealth of exclusive resources, such as research studies and articles, providing valuable insights and knowledge for your school's continuous improvement.

Enable your school to easily post job openings and attract qualified candidates with the Career Center, simplifying the hiring process.

Enjoy exclusive discounts on all SCL events and services, empowering you to access valuable resources and opportunities for your school's growth at a more affordable cost.

Exclusive Discounts

Get access to exclusive cohorts and workshops!

Cohorts and Workshops

SCL conducts school-wide surveys to provide relevant information to the classical Christian community as well as access to in-depth research with partner organizations like the Barna Group.

A connected community of classical Christian thought leaders, including heads of school, board members, marketing and admissions directors, development and fundraising directors, academic deans, grammar and upper school heads, and teachers from all grade levels are here to support and encourage one another.

Member-exclusive Coaching Call sessions. 15-20 online sessions each year from key-thought leaders on topics ranging from legal and operational issues to pedagogical and philosophical discussions. Think of it as a mini-conference each month!

Coaching Calls

Gain new insight, knowledge, and skills around best practices in a short, intensive format with workshops or a year-long mentorship experience with cohorts. Designed for administrators, teachers, parents, leaders, and department heads – anyone seeking to learn and grow in their role.

Conference & Workshops

Our network of seasoned professionals is available to navigate your questions and brainstorm solutions with you. Let us know how you want to direct your time and we will pair you with the senior leader that best suits your school’s unique needs.

Beauty and the Enlivening of the Russian Literary Imagination

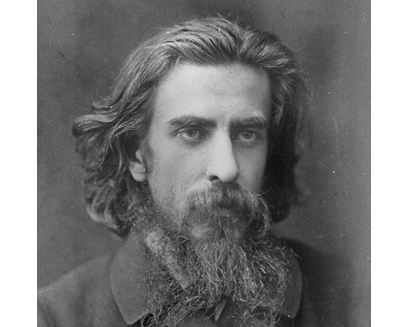

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Readers of The Imaginative Conservative know well the phrase “beauty will save the world.” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn borrowed it from Fyodor Dostoevsky to set the theme of his Nobel Lecture in 1970. British conservative writer Roger Scruton has written extensively about how aesthetics—and beauty in particular—enlarges our vision of humanity, helps us find meaning in our lives, and provides knowledge of our world’s intrinsic values. And Gregory Wolfe used the phrase for the title of his recent book, Beauty Will Save the World: Recovering the Human in an Ideological Age , the theme of which is the importance of an aesthetic understanding for sustaining a civilized culture. Wolfe’s approach is especially appropriate for readers of this site in that he addresses the decline of an aesthetic appreciation in the conservative movement over the previous thirty years which has resulted in a highly politicized conservatism without vision and without deep cultural roots.

As a long time student of Russian culture, I find it inspiring that imaginative conservatives are attaching to a concept (“beauty will save the world”) articulated by Fyodor Dostoevsky one hundred fifty years ago in reference to his own battles against a severe ideological movement bent on politicizing the culture of nineteenth-century Russia. The contentious aesthetic rivalries that defined the last half of that century ultimately resulted by the 1920’s in the devastation of imaginative literature in Russia. The roots of this nightmare of aesthetic dispute were watered by the political upheavals in the 1850’s and 1860’s and Dostoevsky wrote indefatigably to defend Russian art, enliven the Russian imagination, and nurture the human soul. It is a period in history which, I believe, given the arguments of Wolfe and others, imaginative conservatives will find interesting and fertile for thought.

The battle for the Russian imagination and for humane letters in the middle decades of the nineteenth-century was dominated by two literary movements: writers who supported and nurtured an aesthetic approach and the writers who favored a social/political approach based on utilitarian and materialist beliefs. Dostoevsky was one of the great representative figures of the aesthetic movement for he conceived of imaginative literature as the form best able to plumb the depths of the human soul. The radicals, on the other hand, led by Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Nikolai Dobrolyubov, and Dmitry Pisarev, who largely denied the soul and stated that art is inferior to reality, kept mostly to philosophical writings and literary and social criticism as means to argue for political and social change. The central issue of the time, which demanded the attention of the cultural elites and defined the intellectual milieu, was, of course, the issue of servitude. For Russians in the nineteenth-century, just as for Americans, the issue of servitude overwhelmingly infused Russian literary culture with powerful, and at times brilliant, political, social, and literary polemics. But as the United States had a cathartic purging of the issue through the national tragedy of civil war, the emancipation of the serfs in Russia in 1861 only seemed to aggravate the political situation. Because of the historically oppressive nature of the Russian system, political issues could not be addressed openly in the public square; instead, they had to be addressed indirectly, often through humane letters. Consequently, literature and literary criticism became the means whereby the great political and social issues of the day were discussed. The culture favored politicized literature and, as the radical Pisarev exclaimed, “aesthetics [was] my nightmare.”

The radical critics were best represented by Pisarev and Cherynyshevsky. They advocated a politicized literature and were strongly suspicious of the imaginative arts. Chernyshevsky argued that “art is inferior to reality,” and that a materialist and utilitarian worldview should inform not simply social and political policy but literary works as well. Pisarev went one further in his damning of beauty:

Be it noted in praise of human nature in general and of the human mind in particular that up to now, apparently, hardly anyone has ever gone to his death for the sake of something he considered beautiful, while on the other hand there are infinite numbers of people who have given their lives for that which they considered true and socially useful…Art never has had and never can have any martyrs.

This radical worldview was a powerful and vocal force in the latter half of the nineteenth-century, influencing many of the cultural and political elite. (Ultimately it grew into something truly nefarious as Lenin grasped hold of Chernyshevsky’s proto-Bolshevik—and, by critical consensus, terrible—novel, What is to Be Done , and declared it his favorite. By the 1930’s it had become one of the models for Soviet socialist realism.) These radicals, taking their war cry from the fictional nihilist, Yevgeny Bazarov (from Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Children) , declared “one good chemist is twenty times more useful than any poet.” Transcendent ideals as communicated through art and literature terrified the radical critics because transcendent ideals were inherently independent of scientific ways of knowing. As Charles Moser has argued, the radicals supported a monistic theory that would unify all aspects of reality and rejected and denounced any dualistic philosophical or theological approach to knowledge. It is in this intellectual climate that Fyodor Dostoevsky engaged his genius for imagination. We know from his statements and from his extensive diaries that he wrote many of his works as rejoinders to the utilitarian didacticism that Chernyshevsky and his followers on the left were endeavoring to effect on the literary culture of the time.

As the radicals sacrificed aesthetic quality and bound their critique to political and social ideology for the good of the cause, the aesthetes nurtured the transcendent ideals. Dostoevsky, in particular, a profoundly intelligent and philosophic mind, purposely rejected discursive philosophy for art, enlivening his works through the imaginative use of theological, psychological, and poetic language. As Robert Louis Jackson has argued, all of Dostoevsky’s life was a “quest for form” believing as he did that life itself was an art and only art could provide ultimate truth about human nature and human experience. Dostoevsky’s aesthetic approach to life was a direct affront to the radical critics, who unabashedly declared art to be deficient and subservient to reality.

It is readily apparent to the reader of his novels and notebooks that Dostoevsky esteemed art as a higher way of knowing. His statement that “beauty will save the world” is found in his notes on his novel, The Idiot , but we must remember that this statement was followed with no explanation by a second scrawl which reads “two kinds of beauty.” From the notes we also know that Dostoevsky’s attempts to portray beauty were terribly taxing and largely unsuccessful, from his point of view. About The Idiot , he wrote, “For a long time now a certain idea has tormented me, but I’ve been afraid to make a novel out of it, because the thought is too difficult and I’m not ready for it, although the thought is most tempting and I love it. This idea— to portray a wholly beautiful individual. There can be, in my opinion, nothing more difficult than this, in our age especially.” Konstantin Mochulsky, one of Dostoevsky’s best readers, interpreted the novelist’s notes this way:

Sanctity is not a literary theme. In order to create the image of a saint, one has to be a saint oneself. Sanctity is a miracle; the writer cannot be a miracle-worker. Christ only is holy, but a novel about Christ is impossible. Dostoevsky was facing the problem of religious art which tormented poor Gogol to death.

It is clear from his works that Dostoevsky was aware of the theological questions surrounding the depiction of beautiful images throughout the history of Christendom, especially in Eastern Orthodoxy. His achievement lends credence to the argument put forth by Jaroslav Pelikan that within the triad of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, it is the Beautiful which is most difficult and the most dangerous for the Christian writer to present. The Iconoclastic controversies of the eighth and ninth centuries bear witness that rendering the beautiful as holy demands extraordinary consideration. “It is noteworthy,” writes Pelikan, “that both the Second Commandment itself and the message of the Hebrew prophets singled out the identification of the Holy with the Beautiful as the special temptation to sin.” For Dostoevsky this is spiritually and aesthetically agonizing:

All writers…who but undertook the depiction of the positively beautiful, have always had to give up. Because this task is immeasurable. The beautiful is an ideal, but neither our ideal nor that of civilized Europe has been in the least perfected. On earth there is only one positively beautiful person—Christ, so that the appearance of this immeasurably, infinitely beautiful person is, of course, an infinite miracle in itself.

Dostoevsky was well aware of this aesthetic temptation to miss the mark and we, as readers, struggle along with his characters in his great works, The Idiot, The Devils (often known in English as The Possessed ) , and The Brothers Karamazov as they contend with the Beautiful.

Through his efforts to flesh out a better understanding of beauty and its moral implications, Dostoevsky resolved that there are two kinds of beauty—a higher level or “idealistic” beauty, embodied in the divine personality of Christ, and a lower level or sensualist understanding of beauty. This lower type, by stimulating the passions, often incites violence. We find evidence of this in the three novels that most directly address the aesthetics of beauty. In The Idiot , we meet the “wholly beautiful individual,” Prince Myshkin, who at best is helpless to prevent, but at a more profound level is deeply guilty of causing, the death of the “astonishingly beautiful” ( udivitel’no khorosha ) Nastasya Filippovna; in The Devils , the beautiful Stepan Verkhovensky (whom we know from his notes the author deeply loved and respected), chides his nihilist compatriots for denying the sacred as they destroy a community in the name of the Good; and in The Brothers Karamazov the pious and innocent Alyosha proves incapable of staving off the murder of his father. Many of Dostoevsky’s characters rise and fall with their understanding of the claims of beauty. We see this in the character of Dmitry Karamazov, who curses the very injustice of the divinely created world:

Beauty! Here I cannot bear the fact that a man, a man even with a lofty heart and with a lofty mind begins with the ideal of the Madonna, yet ends with the ideal of Sodom…Is there beauty in Sodom? Rest assured that it is to be found in Sodom for the overwhelming majority of people…What is awful is that beauty is not only terrible, but also a mysterious thing. Here the devil struggles with God, but the field of battle is the heart of men.

Dostoevsky’s renditions of beauty and his personal quest for form relentlessly tormented him. Yet it is through his suffering that Russian literature and the voice of the Russian soul survived. In a Russia whose culture was increasingly threatened by an ideological straitjacket, Dostoevsky unleashed his aesthetic powers of discernment to advocate for the transcendent ideals of beauty, truth, and goodness. He utilized his extensive talents to combat the narrowing political ideologies of Cherynshevsky, Pisarev, and others. His literary imagination was large enough to embrace the great contradictions in human nature, for he knew that with evil times impending, only a large moral imagination could hope to stem the tide of degradation. Prophetic, he created fictional characters embodying the deep feelings and ideas of mid-nineteenth century Russia that played out in a manner timelessly significant.

Fyodor Dostoevsky died in 1881 and by the latter half of the nineteenth-century, much of the Russian literary world had succumbed to the ideas of the radicals. Realism in the arts, social utilitarianism, and didactic aims had “assumed the character of a national tendency,” in the words of Marc Slonim. Yet, for a brief period at the turn of the century, the aesthetes returned in force. In 1893, Dmitry Merezhkovsky set the groundwork for a renascence of new artistic writing in his essay, “On the Reasons for the Decline and on the New Trends in Contemporary Russian Literature”. Merezhkovsky excoriated the forces of positivism and utilitarianism then reigning over Russian educated society. He called for a rebirth of the Russian imagination by appealing to idealism, symbolism, and spirituality. His appeal to transcendent values was an extenuation of Dostoevsky’s belief that “beauty will save the world.” With Dostoevsky’s death and Tolstoy’s diminishing powers, Merezhkovsky set himself forth as the writer to re-stimulate imaginative literature in an increasingly difficult political time in Russian history.

During the next few decades, Russian culture moved through a “Silver Age,” in which we see tremendous activity in the literary and visual arts. New literary movements included Symbolism, Acmeism, Impressionism, and various schools of Futurism. Magnificent imaginative writing blossomed; writers and poets such as Aleksander Blok, Andrey Bely, Valery Bryusov, and young Anna Akhmatova, Boris Pasternak, and Osip Mandelshtam, among many others quickened the Russian soul for a time. Also, the call for a transcendent imaginative art advanced a flowering in Russian theology and philosophy by such figures as Nikolai Fyodorov, Sergei Bulgakov, Nikolai Berdyaev, and Pavel Florensky. Disastrously, much of this blooming of the Russian imagination was eradicated by Lenin and his heirs with their suffocating and at times lethal cultural doctrines that were first seeded by the utilitarian radicals in the mid-nineteenth-century. Many of these leading lights of the fin-de-siecle succumbed to the dictates of the revolution or moved to the West; in either case, more often than not, their lots ended badly.

In Beauty Will Save the World, Gregory Wolfe writes the following:

Whereas I once believed that the decadence of the West could only be turned around through politics and intellectual dialectics, I am now convinced that authentic renewal can only emerge out of the imaginative visions of the artist and the mystic. This does not mean that I have withdrawn into some anti-intellectual Palace of Art. Rather, it involves the conviction that politics and rhetoric are not autonomous forces, but are shaped by the pre-political roots of culture: myth, metaphor, and spiritual experience as recorded by the artist and the saint.

Despite the neglect of the arts among many on the right, it has been a truism of the Kirkian school of Anglo-American thought that “imagination rules the world,” and that in order for the world to be ruled justly and fairly, the imagination must be nurtured by the enlivening powers of literature, history, and religion. As Dr. Kirk put it in Enemies of the Permanent Things , “we learn from literature, far more than from personal experience, the character of the saint, the hero, and the philosopher. We learn from literature those insights into the human condition which make life worth living.” What people read and how they approach the arts leads to a deeper understanding of who they are.

Like Dostoevsky and Solzhenitsyn, conservatives must come up from politics and recognize that the roots of a truer just order are watered with the permanent ideals of truth, goodness, and beauty. The insights of the arts of life are vital to make life worth living. As Wolfe argues, if we are willing to invest our hearts and minds in the arts and reject the ingrained philistinism endemic to politics, we can once again enliven the conservative mind. We must “once again put contemplation before action,” seek the permanent things, and nurture the roots that can help us transcend those issues that divide us and can lead us individually and corporately to reconciliation and redemption. We must endeavor through the arts to redeem the time before those roots dry up.

Books mentioned in this essay may be found in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore . The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now .

Further Reading:

Clowes, Edith W. Fiction’s Overcoat: Russian Literary Culture and the Question of Philosophy (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2004).

Jackson, Robert Louis. Dostoevsky’s Quest for Form: A Study of His Philosophy of Art (New Haven: Yale UP, 1966).

All comments are moderated and must be civil, concise, and constructive to the conversation. Comments that are critical of an essay may be approved, but comments containing ad hominem criticism of the author will not be published. Also, comments containing web links or block quotations are unlikely to be approved. Keep in mind that essays represent the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Imaginative Conservative or its editor or publisher.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: glenn davis.

Related Posts

Shakespeare’s Sonnets: The Secret to Immortality

In The Courts of Three Popes

Virgil on History

The Problems of a Playwright in an Atheistic Age

“Resurrection”

Having been to Russia this is poignant and all too true. What that they could recapture that spirit of Dostoevsky in their society today. Wonderful article.

Leave A Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Beauty That Saves

This story is featured in the winter 2020 issue of Lumen .

When Russian novelist and philosopher Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn gave his Nobel lecture in 1970, he could have spoken on any topic he wanted. He could have shared his experiences of turmoil and perseverance living as an artist under Soviet censorship, but instead he spoke of the nature of art itself. He went to an extreme, selecting in his speech a quotation from Fyodor Dostoevsky, “Beauty will save the world.”

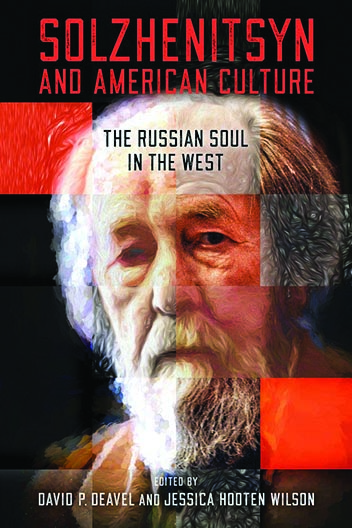

The more I read of Solzhenitsyn’s literary genius in Solzhenitsyn and American Culture: The Russian Soul in the West , edited by St. Thomas Catholic Studies professor David Deavel and former visiting professor Jessica Hooten Wilson, the more enchanted I was with Russian artistry. While American artistic and literary traditions have grappled with democracy, freedom and individuality, the Russian soul has never coalesced around a standard set of ideals. James Pontuso, a Solzhenitsyn and American Culture contributor, wrote, “To be Russian can mean a myriad of things ... there has never been a consensus on what Russia should become. Does Russia venerate tsarism, the Orthodox Church, the Third Rome, communism, liberal democracy, or autocracy? While Americans make things simple and comprehensible, Russians look for complexity in the simplest of things.” Such can be seen, Pontuso goes on, in Solzhenitsyn’s novel In the First Circle , which features a motley array of intellectual characters exiled by the Soviet state. Together the characters write and study in a prison-like university, not unlike the philosophers in Dante’s first circle of the inferno. In the characters’ variety, color and mutual suffering, Solzhenitsyn captures more than just his own experiences as an artist in the most lenient tier of the gulags. He demonstrates something about the human spirit which speaks between the lines of censorship.

My studies of Solzhenitsyn led me to The Museum of Russian Art in Minneapolis. The current exhibit is “Leaders and the Masses: Mega Paintings from Soviet Ukraine.” The largest of the collection is an astonishing 12-by-19-foot canvas depicting Stalin stoically advancing in a proscenium theater packed with applauding civilians. The color-packed massive scenes were intended for public spaces. Sponsored, crafted and exhibited under Stalin’s communist dictatorship, their objective was to affirm state agendas. Though the Ukrainian painters bowed to the artistic mode Stalin demanded, that the creations should be “nationality-specific in form and socialist in content,” their scenes are unconvincing beyond a first glance. The paintings are not satirical. Rather, they are beautiful fantasies of a functioning state, which I think makes them unsuccessful as propaganda.

The wonder of the museum’s exhibit is that, despite the limitations imposed on the artist, truth impresses in desolation. The lie on display dissolved under its own weightlessness, and the truth that the nation was suffering gurgled up in the negative space. In Soviet Russia the truth of daily human turmoil was a universal secret, evident even when cleverly framed. It is this truth that made the paintings beautiful.

I believe that this is what Solzhenitsyn meant when he quoted Dostoevsky’s “Beauty will save the world.” Solzhenitsyn drew on his Russian Orthodox faith and argued that turmoil, suffering and political unrest are ultimately brittle, their own sort of antithesis. In the Nobel lecture he went on to say, “A work of art bears within itself its own verification: Conceptions which are devised or stretched do not stand being portrayed in images, they all come crashing down, appear sickly and pale, convince no one. But those works of art which have scooped up the truth and presented it to us as a living force – they take hold of us, compel us, and nobody ever, not even in ages to come, will appear to refute them.”

In Solzhenitsyn and the American Culture there is an essay by Julianna Leachman. She compares the southern gothic mode of American Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor with Solzhenitsyn’s depiction of the gulags. Both authors show us the peril and terror of the human conundrum but also a golden thread of the human potential – of human virtue in the negative space. These two writers reveal to their readers the best remedy for a world estranged: reality. Art can speak where propaganda cannot, its secret ingredient being the beauty of truth. For the Christian, truth is unconquerable, and so in times of desolation it can emerge all the more starkly.

Truth is unconquerable, so in times of desolation it can emerge all the more starkly.

This past October, Murphy Institute, a partnership between the Center for Catholic Studies and the School of Law, hosted a book launch for the recently released Solzhenitsyn and American Culture: The Russian Soul in the West . The program featured several contributing authors who spoke on their respective chapters and was facilitated by editors Jessica Hooten Wilson and David Deavel. Published by Notre Dame Press, it is available for purchase at undpress.nd.edu/books/P03241 .

Next in Lumen

The Light and Heat of Dorothy Sayers' Jesus

More from lumen.

How to Put the ‘catholic’ in Catholic Studies

Faculty Highlight: Father Austin Litke ’04, OP

30 Years of Impact

The Rome Factor

Related stories.

Interreligious Studies Center Director Writes for Minnesota Multifaith Network

In the News: Sister Mary Micaela Hoffmann on the Journey to Her Vocation

Become A Donor

Contact Info

684 West College St. Sun City, United States America, 064781.

(+55) 654 - 545 - 1235

The Meaning of Dostoevsky’s “Beauty Will Save the World”

- Essays Slider

- November 28, 2013

By Vladimir Soloviev

Dostoevsky not only preached, but, to a certain degree also demonstrated in his own activity this reunification of concerns common to humanity–at least of the highest among these concerns–in one Christian idea.

Being a religious person, he was at the same time a free thinker and a powerful artist. These three aspects , these three higher concerns were not differentiated in him and did not exclude one another, but entered indivisibly into all his activity. In his convictions he never separated truth from good and beauty; in his artistic creativity he never placed beauty apart from the good and the true.

And he was right, because these three live only in their unity. The good, taken separately from truth and beauty, is only an indistinct feeling, a powerless upwelling; truth taken abstractly is an empty word; and beauty without truth and the good is an idol. For Dostoevsky, these were three inseparable forms of one absolute Idea.

The infinity of the human soul–having been revealed in Christ and capable of fitting into itself all the boundlessness of divinity–is at one and the same time both the greatest good, the highest truth, and the most perfect beauty.

Truth is good, perceived by the human mind; beauty is the same good and the same truth, corporeally embodied in solid living form.

And its full embodiment–the end, the goal, and the perfection–already exists in everything, and this is why Dostoevsky said that beauty will save the world.

Source: Mind Your Maker

“Pelicans” (detail) painted by Michael Moukios. Click image to enlarge.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Beauty Will Save the World

By Heather Eaton

This famous and much discussed phrase from Prince Lev Nikolyaevich Myshkin in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot is that beauty will save the world. Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrestled with the enigmatic idea in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1970. It is the title of numerous books and articles on classical art, theological/religious aesthetics, and the natural world. Many are mesmerized with this phrase, idea, image, or desire . Beauty will save the world . Hard to believe, yet is an intriguing union of ethics and aesthetics.

My interest here is not about art, philosophy, or religions. It is not particularly lofty. It is about beauty, mostly in the natural world, and how it transforms the self. Throughout my life, from a young child to now, (just a few years) the intricacies of nature—the incredible presence(s), and dazzling, deep, vibrant, and dynamic beauty—have often seized my attention and time. I have had remarkable, profound, and transformative experiences within nature. I have trekked to mountain vistas, caves, canyons, and waterways; sailed for weeks in the wind, waves, and silence of the Atlantic ocean; watched whales and swam with sharks; studied elephants in South Africa, Botswana, and Kenya; camped in the African bush and Canadian forests; and canoed wilderness waterways. I am acutely cognisant of these incredible privileges. Further, such experiences are the energy, and companions, and often reasons, that have propelled and sustained over thirty years of environmental work.

Of course there are terrifying, exhilarating, demanding, and dreadful experiences of the natural world. Many lives are filled with endless effort to survive, and now, on a diminished planet. Climate change is inducing fires, drought, storms, and immeasurable losses; countless ecosystems and species are struggling to adapt, or just live. It is difficult to offer a reflection about beauty, and how beauty is transformative, without seeming to be callous and uncritical of privilege, or oblivious to ecological stress and anthropogenic climate change. But, in one sense, that is the point of this reflection: to remind us that there is sublime beauty, usually not far, and it can be restorative, or at least offer reprieve or respite.

Like many others, my last year has been lived very locally. Attending to this locus vitae (local life) has expanded and strengthened my interest in the claim that beauty will save the world . Where I live (Ottawa, Canada), the seasons are distinct and authoritative, from -40 (C/F) to +40 C (104 F). People have been unable to travel far during COVID times, with severe long-term lockdowns in most of Canada. The consequences are that the outdoor spaces have been overrun with new nature lovers (interfering in the solace of those who savour the quiet). Yet, it is noteworthy that people are ‘discovering’ the natural world. A further discovery, for many, is that birds exist. Birdwatching has become an epidemic, one could say. I too succumbed to birdwatching, with now four feeders in my (small) backyard. And they came: songbirds, flocking birds and couples, solitary Blue Jays, and the bullies—Grackles and Starlings. Another COVID induced outbreak has been backyard and balcony gardening. I also try to grow flowers that provide gorgeous colors and scents, in addition to their ecosystem duties. This brings with it a renewed awareness of the balm of beauty and the vitality of the locus vitae.

What is required is attentiveness, quiet, discretion, and observation. Nature is never static. Life is animate. Colours dance from sunrise to sunset. Vegetation bends with the wind. Flowers develop from germination to blossoming to regeneration, always on the move. Birds flit. They are private and uninterested in humans, as are many—most—other species. Insects are busy.

There are innumerable publications on these topics. Tips on gardening skills, and recent research on the benefits of gardening—vitamin D infusions, reduced stress, and decreased dementias, loneliness, addiction cravings—are popular. There are myriad birding encyclopedias, blogs, sightings sites, etc. The information gathered about the natural world over the past 100 years or so is monumental. While essential, my focus here is on the ability to be drenched with beauty. Even for a moment. Butterflies and dragonflies appear, and are gone; trees sway majestically in panoramas of green in lush areas. Beauty is transformative: to one’s health, mindset, spirit, and preoccupations. It evokes gratitude, and for some, reverence. Attending to the beauty in—not only information about—nature, is restorative. Beauty will save the world.

This is not a perfect remedy, of course. In Ontario, we are inundated with gypsy moth caterpillars and ticks. While a few of these pesky critters evoke beauty, and they are modes of divine presence, they, like locusts, Asian carp, murder hornets, and red ants, could flourish a bit less, without a reduction of beauty. Also, the interpretative tension here is not between nature as nurturing or nasty, beneficial or burdensome. The question is ‘ where is the place for a meaningful consideration of beauty ’ in our research and reflections?

Academics are trained to be critical: to deconstruct, find fault lines, omissions, bias and shortcomings. These are all important skills. They can, however, become a habit of mind that inhibits other modes of knowing, such as experiencing beauty. Countless times people notice a glorious sunset, appreciate it, and then return to the real work of dissecting and analyzing, scrutinizing theories, evaluating and judging. Experiencing beauty is … nice … but not relevant to social change, climate justice, and factual considerations. I think this is incorrect. Experiencing beauty is integral to human knowing, well-being, and ethical optics. Beauty expands and informs ethics. However, it is ignored as incidental, soft knowledge, too subjective, not transferrable, barely fathomable, and deteriorates under critique. Yet beauty is a robust human experience that enlightens and transforms the human spirit.

Tensions between an emphasis on critique or vision, on de- or reconstruction, and on whether analysis, action, or inspiration are decisive, continue in some religion and ecology (and other) discourses. The debates persist that if you attend to the relevance of cosmology, you might be ignoring injustices. If you consider the importance of evolution, you might be oblivious to the socio-political-economic systems that are undercutting many societies. If you care about animals you might not care about people… and on and on. This is superficial at best, tiresome, often mistaken, and obstructive to amplifying comprehension.

For myself, after several decades of critical investigations, ideological exposures, analytic deconstructions, socio-political critiques, attending to the worst of human social constructions and behaviors, and witnessing and resisting the severe degradation of the natural world, taking a pause on the depth and dynamics of natural beauty is a welcomed alternative. Yet it is also alarming that the deterioration of the natural world results in a parallel deterioration of beauty. The impact spreads if the human spirit, capacities, and ability to feel beauty and reverence also diminish.

There are longstanding traditions in most cultures that connect aesthetics with ethics. Nevertheless, these have been by-passed in much work on ecological ethics. Some writers such as Henry David Thoreau, Gaston Bachelard, Rachel Carson, David Abrams, Anne Dillard, Thomas King, and Gary Snyder, write intelligently and elegantly about the centrality and vitality of beauty blended with ethics. While such nature writers are usually respected, the emphasis on experiencing deeply the natural world, and reveling in beauty, is often considered lovely, but extraneous; something akin to being momentarily refreshed by Mary Oliver’s exquisite poems. However, there are insights emerging from new materialisms, positive psychology, and research on how experiences of wonder are healing, that offer some promise to (re)unite ethics and aesthetics.

I am skeptical that beauty will save the world . I don’t know what save the world means in this era of overlapping eco-crises. And, I am unconvinced that critical analyses will offer deep transformation. I do know that attending to the beauty of the natural world, even the flowers and birds of our locus vitae , can lift spirits, expand interiority, calm anxieties, offer clarity, and inspire ethical insights. Perhaps we can add a medicinal dose of beauty to each day and see where that takes us. It can’t hurt. We may be surprised by the joy, inspiration, radical hope, and gratitude that experiences of beauty can nurture.

Heather Eaton, PhD , is a professor at Saint Paul University, Ottawa, Canada. Research areas: religion and ecology; gender/feminist, ecology aspects of social conflicts; nonviolence; animal rights. Select publications: Advancing Nonviolence and Social Transformation, with Lauren Levesque; The Intellectual Journey of Thomas Berry : Ecological Awareness, Exploring Religion, Ethics and Aesthetics , with Sigurd Bergmann; Introducing Ecofeminist Theologies: Ecofeminism and Globalization , with Lois Lorentzen.

Counterpoint blogs may be reprinted with the following acknowledgement: “This article was published by Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge on 30 June 2021.”

The views and opinions expressed on this website, in its publications, and in comments made in response to the site and publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Counterpoint: Navigating Knowledge, its founders, its staff, or any agent or institution affiliated with it, nor those of the institution(s) with which the author is affiliated. Counterpoint exists to promote vigorous debate within and across knowledge systems and therefore publishes a wide variety of views and opinions in the interests of open conversation and dialogue.

Photo credits: Blue Jay, Ottawa, Canada, © Heather Eaton, 2021

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

By using this form you agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website. *

Related Posts

Counterpoint Blog

Why we need greener cities.

Why We Need Greener Cities By Dorin David If someone offers you a glass of dirty water, obviously you don’t drink it. Maybe after walking thirsty in a dessert for a couple of days, but Read more…

Kritik jenseits polarisierender Selbstvergewisserung: Hamas, Israel und die deutsche Diskussionskultur

Kritik jenseits polarisierender Selbstvergewisserung: Hamas, Israel und die deutsche Diskussionskultur Von Markus Dreßler —For the English version of this blog post, please click here— Der Terrorangriff der Hamas vom 7. Oktober des letzten Jahres auf Read more…

Critical Dialogues or Self-Assured Monologues: Hamas, Israel, and the German Debate

Critical Dialogues or Self-Assured Monologues: Hamas, Israel, and the German Debate By Markus Dressler —For a German version of this blog post, please click here— The Hamas terrorist attack on a music festival and Jewish Read more…

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

- Email Signup

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

Beauty will save the world.

By Heather Eaton. Counterpoint Navigating Knowledge. June 30, 2021.